Comparative Evaluation of Sequencing Technologies for Detecting Antimicrobial Resistance in Bloodstream Infections

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Burden of Bloodstream Infections (BSIs) and the Global Threat of AMR

1.2. Limitations of Traditional Culture-Based AST in Urgent Care Settings

1.3. The Rise of Sequencing Technologies in Infectious Disease Diagnostics

2. Overview of Sequencing Technologies for AMR Detection

2.1. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

2.2. Targeted Sequencing Panels

2.3. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing (mNGS)

2.4. Long-Read Sequencing (Nanopore, PacBio)

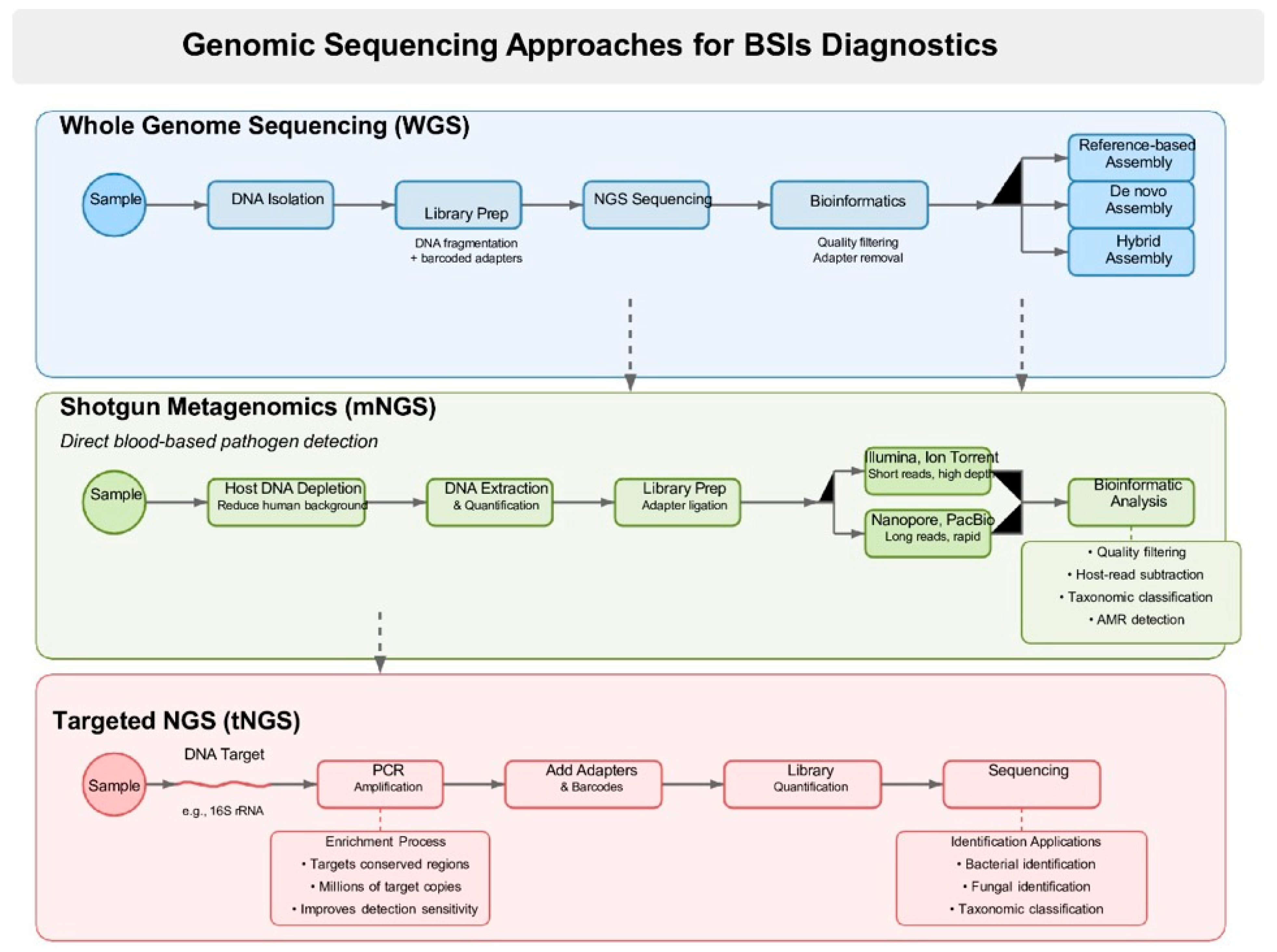

3. General Workflow and Principles for Each Method

3.1. Key Definitions: Clinical Sensitivity, Diagnostic Yield, Detection of Novel Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs), Turnaround Time

3.2. WGS of Cultured Isolates-Workflow

3.2.1. Advantages and Limitations

3.2.2. Clinical Performance Data

3.2.3. Major Platforms & Companies

3.3. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing (mNGS) Directly from Blood-Workflow and Benefits

3.3.1. Technical Challenges

3.3.2. Leading Commercial Platforms

3.3.3. Performance Metrics

3.3.4. Turnaround Time and Real-World Diagnostic Impact

3.3.5. Limitations and Gaps in Validation

3.4. Targeted Sequencing Panels

3.4.1. Benefits

3.4.2. Limitations

3.4.3. Prominent Commercial Assays

3.4.4. Comparative Performance of tNGS

3.5. Long-Read Sequencing (Nanopore & PacBio)-Advantages and Limitations

3.5.1. Pilot Studies and Proof-of-Concept Trials in BSI and AMR Detection

3.5.2. Potential Future Use in Rapid Point-of-Care Diagnostics

4. Comparative Summary: Table/Matrix: Performance Comparison of Sequencing Platforms

5. Regulatory and Quality Assurance Frameworks for Clinical Next-Generation Sequencing: CLSI, CAP, and ISO 15189 Guidelines

6. Clinical Considerations and Implementation

7. Future Perspectives

7.1. AI-Enhanced Prediction of Phenotypic Resistance from Genotypes

7.2. Real-Time Sequencing in Emergency/ICU Settings

7.3. Multi-Omic Integration (Resistome + Transcriptome + Host Response)

7.4. Global Standards for Resistome Reporting in BSIs

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martinez, R.M.; Wolk, D.M. Bloodstream Infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 653–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renner, L.D.; Zan, J.; Hu, L.I.; Martinez, M.; Resto, P.J.; Siegel, A.C.; Torres, C.; Hall, S.B.; Slezak, T.R.; Nguyen, T.H.; et al. Detection of ESKAPE Bacterial Pathogens at the Point of Care Using Isothermal DNA-Based Assays in a Portable Degas-Actuated Microfluidic Diagnostic Assay Platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e02449-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timsit, J.F.; Ruppé, E.; Barbier, F.; Tabah, A.; Bassetti, M. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients: An expert statement. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C.L.; Albin, O.R.; Mobley, H.L.T.; Bachman, M.A. Bloodstream infections: Mechanisms of pathogenesis and opportunities for intervention. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Healthcare-associated infections acquired in intensive care units. In ECDC. Annual Epidemiological Report for 2021; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- See, I.; Freifeld, A.G.; Magill, S.S. Causative Organisms and Associated Antimicrobial Resistance in Healthcare-Associated, Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections From Oncology Settings, 2009–2012. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warhurst, G.; Dunn, G.; Chadwick, P.; Blackwood, B.; McAuley, D.; Perkins, G.D.; McMullan, R.; Gates, S.; Bentley, A.; Young, D. Rapid detection of health-care-associated bloodstream infection in critical care using multipathogen real-time polymerase chain reaction technology: A diagnostic accuracy study and systematic review. Health Technol. Assess. 2015, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Lee, C.-H.; Yang, C.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Tang, H.-J.; Ko, W.-C. Beneficial effects of early empirical administration of appropriate antimicrobials on survival and defervescence in adults with community-onset bacteremia. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, V.X.; Fielding-Singh, V.; Greene, J.D.; Baker, J.M.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Bhattacharya, J.; Escobar, G.J. The Timing of Early Antibiotics and Hospital Mortality in Sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; McIntyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1181–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambregts, M.M.C.; Bernards, A.T.; van der Beek, M.T.; Visser, L.G.; de Boer, M.G. Time to positivity of blood cultures supports early re-evaluation of empiric broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0208819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, S.S.; Lai, Y.L.; Warner, S.; Strich, J.R.; Babiker, A.; Ricotta, E.E.; Demirkale, C.Y.; Dekker, J.P.; Palmore, T.N.; Rhee, C.; et al. Inappropriate empirical antibiotic therapy for bloodstream infections based on discordant in-vitro susceptibilities: A retrospective cohort analysis of prevalence, predictors, and mortality risk in US hospitals. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Sepsis: Key Facts; WHO Fact Sheet (3 May 2024); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Yang, H.; Long, J.; Duan, G. Mortality and genetic diversity of antibiotic-resistant bacteria associated with bloodstream infections: A systemic review and genomic analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, K.; Daniels, R.; Kissoon, N.; Machado, F.R.; Schachter, R.D.; Finfer, S. Recognizing Sepsis as a Global Health Priority—A WHO Resolution. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; Wellcome Trust: London, UK, 2016; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- de Kraker, M.E.; Stewardson, A.J.; Harbarth, S. Will 10 Million People Die a Year due to Antimicrobial Resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, F.; Viaggi, B.; Galli, L.; Rossolini, G.M. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing: Present and Future. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2015, 34, 1128–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Haery, C.; Paladugu, B.; Kumar, A.; Symeoneides, S.; Taiberg, L.; Osman, J.; Trenholme, G.; Opal, S.M.; Goldfarb, R.; et al. The duration of hypotension before the initiation of antibiotic treatment is a critical determinant of survival in a murine model of Escherichia coli septic shock: Association with serum lactate and inflammatory cytokine levels. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 193, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbetts, R.J. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Paradigms: Current Status and Future Directions. Am. Soc. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2018, 31, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 35th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Methodology and Instructions for MIC Determination and Disk Diffusion; EUCAST: Växjö, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Šuster, K.; Cör, A. Induction of Viable but Non-Culturable State in Clinically Relevant Staphylococci and Their Detection with Bacteriophage K. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, K.; Hammond, R.; Parcell, B.J.; Gillespie, S.H. Investigating the time to blood culture positivity: Why does it take so long? J. Med. Microbiol. 2025, 74, 001942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehren, K.; Meißner, A.; Jazmati, N.; Wille, J.; Jung, N.; Vehreschild, J.J.; Hellmich, M.; Seifert, H. Clinical Impact of Rapid Species Identification From Positive Blood Cultures With Same-day Phenotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing on the Management and Outcome of Bloodstream Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Lv, Q.; Kong, D.; Jiang, H.; Ren, Y.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Clinical evaluation of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in unbiased pathogen diagnosis of urinary tract infection. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalis, M.; Viana Veloso, G.G.; Aguiar, P.N., Jr.; Gimenes, N.; Reis, M.X.; Matsas, S.; Ferreira, C.G. Next-generation sequencing impact on cancer care: Applications, challenges, and future directions. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1420190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Miller, S.; Chiu, C.Y. Clinical Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing for Pathogen Detection. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2019, 14, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodino, K.G.; Simner, P.J. Status check: Next-generation sequencing for infectious-disease diagnostics. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e178003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagini, F.; Greub, G. Bacterial genome sequencing in clinical microbiology: A pathogen-oriented review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2007–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, R.M.; Bragin, E.; Parkhill, J.; Morales, G.; Schmitz, J.E.; Rhodes, P.A. Machine-Learning Model for Prediction of Cefepime Susceptibility in Escherichia coli from Whole-Genome Sequencing Data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e01431-01422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaray, R.I.; Saruuljavkhlan, B.; Fauzia, K.A.; Torres, R.C.; Thorell, K.; Dewi, S.R.; Kryukov, K.A.; Matsumoto, T.; Akada, J.; Vilaichone, R.K.; et al. Global Antimicrobial Resistance Gene Study of Helicobacter pylori: Comparison of Detection Tools, ARG and Efflux Pump Gene Analysis, Worldwide Epidemiological Distribution, and Information Related to the Antimicrobial-Resistant Phenotype. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, M.; Bryson, A.L.; Palmore, T.N. Whole Genome Sequencing Applications in Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Prevention. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2024, 26, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Liang, M.; Song, J.; Chen, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Tang, J.; Ma, Y.; Yang, B.; et al. Utilizing Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing for Rapid, Accurate, and Cost-Effective Pathogen Detection in Lower Respiratory Tract Infections. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, K.N.; Street, T.L.; Sanderson, N.D.; Eyre, D.W. Metagenomic Sequencing as a Pathogen-Agnostic Clinical Diagnostic Tool for Infectious Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e0291620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.; Li, X.; Mei, A.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Xie, S. The diagnostic value of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in infectious diseases. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Xiong, Y.; Tu, T.; Feng, J.; Fu, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, N.; Li, D. Diagnostic performance of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for the detection of pathogens in cerebrospinal fluid in pediatric patients with central nervous system infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, L.; Xia, H.; Li, J.; Ye, Y. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA improves the early diagnosis of suspected infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Pongpanich, M.; Porntaveetus, T. Unraveling metagenomics through long-read sequencing: A comprehensive review. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, F.; Jamin, C.; de Haan, A.; Witteveen, S.; Bos, J.; van der Heide, H.G.J.; Schouls, L.M.; Hendrickx, A.P.A.; van Arkel, A.L.E.; Leversteijn-van Hall, M.A.; et al. Genomic surveillance of multidrug-resistant organisms based on long-read sequencing. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, X.Z.; Li, M.H.; Li, B.; Yang, M.J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X.J. Comparison of third-generation sequencing approaches to identify viral pathogens under public health emergency conditions. Virus Genes. 2020, 56, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehler, J.B.; Burns, K.; Warner, J.; Schmitz, U. Long-Read Sequencing for the Rapid Response to Infectious Diseases Outbreaks. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2025, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafazoli, A.; Hemmati, M.; Rafigh, M.; Alimardani, M.; Khaghani, F.; Korostynski, M.; Karnes, J.H. Leveraging long-read sequencing technologies for pharmacogenomic testing: Applications, analytical strategies, challenges, and future perspectives. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1435416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buermans, H.P.; den Dunnen, J.T. Next generation sequencing technology: Advances and applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1932–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heather, J.M.; Chain, B. The sequence of sequencers: The history of sequencing DNA. Genomics 2016, 107, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.B.; Oberg, A.L.; Adjei, A.A.; Wang, L. A Clinician’s Guide to Bioinformatics for Next-Generation Sequencing. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, S.; McPherson, J.D.; McCombie, W.R. Coming of age: Ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, E.L.; Auger, H.; Jaszczyszyn, Y.; Thermes, C. Ten years of next-generation sequencing technology. Trends Genet. 2014, 30, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoads, A.; Au, K.F. PacBio Sequencing and Its Applications. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D. Next-generation sequencing and its clinical application. Cancer Biol. Med. 2019, 16, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Yin, J.; Xiong, J.; Xu, M.; Qi, Q.; Yang, W. Diagnostic yield of next-generation sequencing in suspect primary immunodeficiencies diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, F.; Osterlund, T.; Boulund, F.; Marathe, N.P.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Kristiansson, E. Identification and reconstruction of novel antibiotic resistance genes from metagenomes. Microbiome 2019, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silas, U.; Bluher, M.; Bosworth Smith, A.; Saunders, R. Fast In-House Next-Generation Sequencing in the Diagnosis of Metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: A Hospital Budget Impact Analysis. J. Health Econ. Outcomes Res. 2023, 10, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminu, S.; Ascandari, A.; Laamarti, M.; Safdi, N.E.H.; El Allali, A.; Daoud, R. Exploring microbial worlds: A review of whole genome sequencing and its application in characterizing the microbial communities. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 50, 805–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beh, J.Q.; Wick, R.R.; Howden, B.P.; Connor, C.H.; Webb, J.R. Challenges and considerations for whole-genome-based antimicrobial resistance plasmid investigations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e0109725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossen, J.W.A.; Friedrich, A.W.; Moran-Gilad, J. Practical issues in implementing whole-genome-sequencing in routine diagnostic microbiology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, M.J.; Ekelund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Canton, R.; Doumith, M.; Giske, C.; Grundman, H.; Hasman, H.; Holden, M.T.G.; Hopkins, K.L.; et al. The role of whole genome sequencing in antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria: Report from the EUCAST Subcommittee. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, J.C.; McCallum, N.; Sintchenko, V.; Howden, B.P. Whole genome sequencing in clinical and public health microbiology. Pathology 2015, 47, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, G.H.; McDermott, P.F.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Tadesse, D.A.; Mukherjee, S.; Bodeis-Jones, S.; Kabera, C.; Gaines, S.A.; Loneragan, G.H.; et al. WGS accurately predicts antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2763–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, N.C.; Price, J.R.; Cole, K.; Everitt, R.; Morgan, M.; Finney, J.; Kearns, A.M.; Pichon, B.; Young, B.; Wilson, D.J.; et al. Prediction of Staphylococcus aureus antimicrobial resistance by whole-genome sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, G.H.; Sabo, J.L.; Rice-Trujillo, C.; Hernandez, J.; McDermott, P.F. Whole-genome sequencing based characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Enterococcus. Pathog. Dis. 2018, 76, fty018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeukens, J.; Freschi, L.; Kukavica-Ibrulj, I.; Emond-Rheault, J.-G.; Tucker, N.P.; Levesque, R.C. Genomics of antibiotic-resistance prediction in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1435, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Busó, L.; Yeats, C.A.; Taylor, B.; Goater, R.J.; Underwood, A.; Abudahab, K.; Argimón, S.; Ma, K.C.; Mortimer, T.D.; Golparian, D.; et al. A community-driven resource for genomic epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance prediction of Neisseria gonorrhoeae at Pathogenwatch. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grad, Y.H.; Kirkcaldy, R.D.; Trees, D.; Dordel, J.; Harris, S.R.; Goldstein, E.; Weinstock, H.; Parkhill, J.; Hanage, W.P.; Bentley, S.; et al. Genomic epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime in the USA: A retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokma, J.; Vereecke, N.; Nauwynck, H.; Haesebrouck, F.; Theuns, S.; Pardon, B.; Boyen, F. Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Genetic Markers for Antimicrobial Resistance in Mycoplasma bovis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0026221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enkirch, T.; Werngren, J.; Groenheit, R.; Alm, E.; Advani, R.; Karlberg, M.L.; Mansjö, M. Systematic Review of Whole-Genome Sequencing Data To Predict Phenotypic Drug Resistance and Susceptibility in Swedish Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates, 2016 to 2018. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtzhals, M.L.; Norman, A.; Svensson, E.; Lillebaek, T.; Folkvardsen, D.B. Applying whole genome sequencing to predict phenotypic drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Leveraging 20 years of nationwide data from Denmark. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e00430-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.K.; Stobart, M.; Akochy, P.M.; Adam, H.; Janella, D.; Rabb, M.; Alawa, M.; Sekirov, I.; Tyrrell, G.J.; Soualhine, H. Evaluation of Whole Genome Sequencing-Based Predictions of Antimicrobial Resistance to TB First Line Agents: A Lesson from 5 Years of Data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painset, A.; Day, M.; Doumith, M.; Rigby, J.; Jenkins, C.; Grant, K.; Dallman, T.J.; Godbole, G.; Swift, C. Comparison of phenotypic and WGS-derived antimicrobial resistance profiles of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from cases of diarrhoeal disease in England and Wales, 2015–2016. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realegeno, S.; Mirasol, R.; Garner, O.B.; Yang, S. Clinical Whole Genome Sequencing for Clarithromycin and Amikacin Resistance Prediction and Subspecies Identification of Mycobacterium abscessus. J. Mol. Diagn 2021, 23, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W.K.; Ferrarini, M.; Morello, L.G.; Faoro, H. Resistome analysis of bloodstream infection bacterial genomes reveals a specific set of proteins involved in antibiotic resistance and drug efflux. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2020, 2, lqaa055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustam, A.; Jayaraman, J.; Ramsubhag, A. Whole genome sequencing reveals complex resistome features of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from patients at major hospitals in Trinidad, West Indies. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 37, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quail, M.A.; Smith, M.; Coupland, P.; Otto, T.D.; Harris, S.R.; Connor, T.R.; Bertoni, A.; Swerdlow, H.P.; Gu, Y. A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: Comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.S. Whole Genome Sequencing: Applications in Clinical Bacteriology. Med. Princ. Pract. 2024, 33, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, G.E.; Dabernig-Heinz, J.; Lipp, M.; Cabal, A.; Simantzik, J.; Kohl, M.; Scheiber, M.; Lichtenegger, S.; Ehricht, R.; Leitner, E.; et al. Real-Time Nanopore Q20+ Sequencing Enables Extremely Fast and Accurate Core Genome MLST Typing and Democratizes Access to High-Resolution Bacterial Pathogen Surveillance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e0163122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quince, C.; Walker, A.W.; Simpson, J.T.; Loman, N.J.; Segata, N. Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Geng, S.; Mei, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yang, T.; Zhu, C.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y.; Tong, F.; Gao, Y.; et al. Diagnostic Value and Clinical Application of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing for Infections in Critically Ill Patients. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 6309–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Miller, S.A. Clinical metagenomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simner, P.J.; Miller, S.; Carroll, K.C. Understanding the Promises and Hurdles of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing as a Diagnostic Tool for Infectious Diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yek, C.; Pacheco, A.R.; Vanaerschot, M.; Bohl, J.A.; Fahsbender, E.; Aranda-Díaz, A.; Lay, S.; Chea, S.; Oum, M.H.; Lon, C.; et al. Metagenomic Pathogen Sequencing in Resource-Scarce Settings: Lessons Learned and the Road Ahead. Front. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, 926695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, J.P. Metagenomics for Clinical Infectious Disease Diagnostics Steps Closer to Reality. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e00850-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Batool, M.; Galloway-Peña, J. Clinical metagenomics—Challenges and future prospects. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1186424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulanto Chiang, A.; Dekker, J.P. From the Pipeline to the Bedside: Advances and Challenges in Clinical Metagenomics. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, S331–S340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moragues-Solanas, L.; Le-Viet, T.; McSorley, E.; Halford, C.; Lockhart, D.S.; Aydin, A.; Kay, G.L.; Elumogo, N.; Mullen, W.; O’Grady, J.; et al. Development and proof-of-concept demonstration of a clinical metagenomics method for the rapid detection of bloodstream infection. BMC Med. Genom. 2024, 17, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayvargiya, P.; Jeraldo, P.R.; Thoendel, M.J.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K.E.; Esquer Garrigos, Z.; Sohail, M.R.; Chia, N.; Pritt, B.S.; Patel, R. Application of metagenomic shotgun sequencing to detect vector-borne pathogens in clinical blood samples. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björnberg, A.; Nestor, D.; Peker, N.; Sinha, B.; Couto, N.; Rossen, J.; Sundqvist, M.; Mölling, P. Critical Steps in Shotgun Metagenomics-Based Diagnosis of Bloodstream Infections Using Nanopore Sequencing. Apmis 2025, 133, e13511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitwieser, F.P.; Pertea, M.; Zimin, A.V.; Salzberg, S.L. Human contamination in bacterial genomes has created thousands of spurious proteins. Genome Res. 2019, 29, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guccione, C.; Patel, L.; Tomofuji, Y.; McDonald, D.; Gonzalez, A.; Sepich-Poore, G.D.; Sonehara, K.; Zakeri, M.; Chen, Y.; Dilmore, A.H.; et al. Incomplete human reference genomes can drive false sex biases and expose patient-identifying information in metagenomic data. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Li, R.; Shi, J.; Tan, P.; Zhang, R.; Li, J. Liquid biopsy for infectious diseases: A focus on microbial cell-free DNA sequencing. Theranostics 2020, 10, 5501–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Yin, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Gai, W.; et al. Clinical evaluation of cell-free and cellular metagenomic next-generation sequencing of infected body fluids. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 55, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, L.M.; Carrillo, C.; Wong, A. Managing false positives during detection of pathogen sequences in shotgun metagenomics datasets. BMC Bioinform. 2024, 25, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, S.; Mulrooney, C.; Leonard, M.; Flanagan, M.; Nashev, D.; Cormican, M. P10 Risk management of clinical false positives with multiplex PCR blood culture panels: A lesson in diagnostic stewardship for microbiology trainees. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 6, dlae136.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Olsen, H.E.; Paten, B.; Akeson, M. The Oxford Nanopore MinION: Delivery of nanopore sequencing to the genomics community. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.D.; Knox, N.C.; Peterson, C.L.; Reimer, A.R. Highlighting Clinical Metagenomics for Enhanced Diagnostic Decision-making: A Step Towards Wider Implementation. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcock, B.P.; Raphenya, A.R.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Tsang, K.K.; Bouchard, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Huynh, W.; Nguyen, A.-L.V.; Cheng, A.A.; Liu, S.; et al. CARD 2020: Antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, D517–D525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grumaz, C.; Hoffmann, A.; Vainshtein, Y.; Kopp, M.; Grumaz, S.; Stevens, P.; Decker, S.O.; Weigand, M.A.; Hofer, S.; Brenner, T.; et al. Rapid Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Diagnostics of Bacteremia in Septic Patients. J. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 22, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango-Argoty, G.; Garner, E.; Pruden, A.; Heath, L.S.; Vikesland, P.; Zhang, L. DeepARG: A deep learning approach for predicting antibiotic resistance genes from metagenomic data. Microbiome 2018, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.M.; Martin, I.W.; Moschetti, W.E.; Kershaw, C.M.; Tsongalis, G.J. Third-Generation Sequencing in the Clinical Laboratory: Exploring the Advantages and Challenges of Nanopore Sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 58, e01315-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, L.; Zhu, C.; Jin, J.; Song, C.; Dong, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. Clinical value of metagenomic next-generation sequencing by Illumina and Nanopore for the detection of pathogens in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in suspected community-acquired pneumonia patients. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1021320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauwkamp, T.A.; Thair, S.; Rosen, M.J.; Blair, L.; Lindner, M.S.; Vilfan, I.D.; Kawli, T.; Christians, F.C.; Venkatasubrahmanyam, S.; Wall, G.D.; et al. Analytical and clinical validation of a microbial cell-free DNA sequencing test for infectious disease. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, C.A.; Yang, S.; Garner, O.B.; Green, D.A.; Gomez, C.A.; Dien Bard, J.; Pinsky, B.A.; Banaei, N. Clinical Impact of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing of Plasma Cell-Free DNA for the Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Kudinha, T.; Jia, P.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Q. Comprehensive Pathogen Identification, Antibiotic Resistance, and Virulence Genes Prediction Directly From Simulated Blood Samples and Positive Blood Cultures by Nanopore Metagenomic Sequencing. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 620009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaberg, R.; Chiu, C.Y.; Miller, S.; Procop, G.W.; Weinstock, G.; the Professional Practice Committee and Committee on Laboratory Practices of the American Society for Microbiology; the Microbiology Resource Committee of the College of American Pathologists. Validation of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing Tests for Universal Pathogen Detection. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2017, 141, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, A.M.; Raphenya, A.R.; Melano, R.G.; Seah, C.; Yee, N.R.; MacFadden, D.R.; McArthur, A.G.; Schneeberger, P.H.H.; Coburn, B. Performance Characteristics of Next-Generation Sequencing for the Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance Determinants in Escherichia coli Genomes and Metagenomes. mSystems 2022, 7, e0002222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, R. Advancing Clinical Microbiology: Applications and Future of Next-Generation Sequencing. SAR J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2024, 5, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tong, J.; Liu, Y.; Shen, W.; Hu, P. Targeted next generation sequencing is comparable with metagenomic next generation sequencing in adults with pneumonia for pathogenic microorganism detection. J. Infect. 2022, 85, e127–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quek, Z.B.R.; Ng, S.H. Hybrid-Capture Target Enrichment in Human Pathogens: Identification, Evolution, Biosurveillance, and Genomic Epidemiology. Pathogens 2024, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, F.; Lin, Z.; Li, H.; Miao, Q.; Fang, T.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X.; et al. Etiological diagnostic performance of probe capture-based targeted next-generation sequencing in bloodstream infection. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 2539–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Yu, F.; Zhang, D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, D.; Lou, B.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, S. Molecular rapid diagnostic testing for bloodstream infections: Nanopore targeted sequencing with pathogen-specific primers. J. Infect. 2024, 88, 106166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Peng, D.; Fu, A.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xia, L.; Shi, W.; Qian, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, F.; et al. The application of nanopore targeted sequencing in the diagnosis and antimicrobial treatment guidance of bloodstream infection of febrile neutropenia patients with hematologic disease. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassall, J.; Coxon, C.; Patel, V.C.; Goldenberg, S.D.; Sergaki, C. Limitations of current techniques in clinical antimicrobial resistance diagnosis: Examples and future prospects. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illumina. AmpliSeq™ Antimicrobial Resistance Research Panel. n.d. Available online: https://www.illumina.com/products/by-brand/ampliseq/community-panels/antimicrobial-resistance.html (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Guernier-Cambert, V.; Chamings, A.; Collier, F.; Alexandersen, S. Diverse Bacterial Resistance Genes Detected in Fecal Samples From Clinically Healthy Women and Infants in Australia—A Descriptive Pilot Study. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 596984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, T.; Kay, G.L.; Richardson, H.; Aydin, A.; Baldan, R.; Jeanes, C.; Rae, D.; Grundy, S.; Turner, D.J.; Wain, J.; et al. Nanopore metagenomics enables rapid clinical diagnosis of bacterial lower respiratory infection. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, J.; Tarumoto, N.; Kodana, M.; Ashikawa, S.; Imai, K.; Kawamura, T.; Ikebuchi, K.; Murakami, T.; Mitsutake, K.; Maeda, T.; et al. An identification protocol for ESBL-producing Gram-negative bacteria bloodstream infections using a MinION nanopore sequencer. J. Med. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeek, R.; Leitl, C.J.; Stoll, S.E.; Wetsch, W.A.; Kammerer, T.; Mathes, A.; Böttiger, B.W.; Seifert, H.; Hart, D.; Dusse, F. The Value of Next-Generation Sequencing in Diagnosis and Therapy of Critically Ill Patients with Suspected Bloodstream Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-S.; Zhu, Z.; Lin, X.; Huang, H.-Y.; Li, L.-P.; Li, J.; Ni, J.; Li, P.; Chen, L.; Tang, W.; et al. Enhancing bloodstream infection diagnostics: A novel filtration and targeted next-generation sequencing approach for precise pathogen identification. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1538265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.-K.; Chang, J.-P.; Huang, W.-C.; Tai, C.-H.; Wu, H.-T.; Chi, C.-H. Comparative of clinical performance between next-generation sequencing and standard blood culture diagnostic method in patients suffering from sepsis. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2022, 55, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.; Heavens, D.; Lan, Y.; Horsfield, S.; Clark, M.D.; Leggett, R.M. Nanopore adaptive sampling: A tool for enrichment of low abundance species in metagenomic samples. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Lee, H.; Williams, A.; Baffour-Kyei, A.; Lee, S.-H.; Troakes, C.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Breen, G.; Iacoangeli, A. Investigating the Performance of Oxford Nanopore Long-Read Sequencing with Respect to Illumina Microarrays and Short-Read Sequencing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantere, T.; Kersten, S.; Hoischen, A. Long-Read Sequencing Emerging in Medical Genetics. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzauti, D.; Biazzo, M.; Podrini, C.; Alevizou, A.; Safarika, A.; Damoraki, G.; Koufargyris, P.; Tasouli, E.; Skopelitis, I.; Poulakou, G.; et al. An NGS-assisted diagnostic workflow for culture-independent detection of bloodstream pathogens and prediction of antimicrobial resistances in sepsis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1656171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-Y.; Wu, H.-C.; Li, Y.-L.; Cheng, H.-W.; Liou, C.-H.; Chen, F.-J.; Liao, Y.-C. Comprehensive pathogen identification and antimicrobial resistance prediction from positive blood cultures using nanopore sequencing technology. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Wang, J.; Qin, X.; Duan, M.; Wang, M.; Guan, Y.; Xu, X. The performance of nanopore sequencing in rapid detection of pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes in blood cultures. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 111, 116720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, V. Method of the year: Long-read sequencing. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Handler, H.P.; Victorsen, A.; Flaten, Z.; Ellison, A.; Knutson, T.P.; Munro, S.A.; Martinez, R.J.; Billington, C.J.; Laffin, J.J.; et al. Validation of a comprehensive long-read sequencing platform for broad clinical genetic diagnosis. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1499456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, W.; Gai, W.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Z. Clinical Application of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing in Sepsis Patients with Early Antibiotic Treatment. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 4695–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, X.; Yang, F.; Zhao, Y. Diagnostic value of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in sepsis and bloodstream infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1117987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Y.H.; Wu, Y.X.; Hu, W.P.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.P.; Song, Z.J.; Luo, Z.; Ju, M.J.; Shi, M.H.; Xu, S.Y.; et al. The Clinical Impact of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) Test in Hospitalized Patients with Suspected Sepsis: A Multicenter Prospective Study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.J.; Luo, W.W.; Zhang, S.S.; Xie, J.Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhong, Y.Y.; Zou, X.F.; Gong, H.J.; Ye, M.L. The clinical application value of multi-site mNGS detection of patients with sepsis in intensive care units. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liang, S.; Zhang, D.; He, M.; Zhang, H. The clinical application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in sepsis of immunocompromised patients. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1170687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Gan, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Niu, T. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing Unveils Prognostic Microbial Synergism and Guides Precision Therapy in Candidemia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 5263–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncavage, E.J.; Coleman, J.F.; de Baca, M.E.; Kadri, S.; Leon, A.; Routbort, M.; Roy, S.; Suarez, C.J.; Vanderbilt, C.; Zook, J.M. Recommendations for the Use of in Silico Approaches for Next-Generation Sequencing Bioinformatic Pipeline Validation: A Joint Report of the Association for Molecular Pathology, Association for Pathology Informatics, and College of American Pathologists. J. Mol. Diagn. 2023, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravzanaadii, M.; Asai, S.; Kakizoe, H.; Natsagdorj, M.E.; Miyachi, H. A pilot study of on-site evaluation as external quality assessment for ISO 15189 accreditation of laboratories performing next-generation sequencing oncology tests. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2023, 37, e24901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney, B.; Diaz, A.; Chavis, C.; Ghattas, C.; Evans, D.; Arambula, D.; Stang, H.; Next-Generation Sequencing Quality, I. The Next-Generation Sequencing Quality Initiative and Challenges in Clinical and Public Health Laboratories. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffreda, L.; Rodriguez-Perez, H.; Flores, C. Nanopore sequencing and its application to the study of microbial communities. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1497–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianconi, I.; Aschbacher, R.; Pagani, E. Current Uses and Future Perspectives of Genomic Technologies in Clinical Microbiology. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.C.S.; Acman, M.; van Dorp, L.; Balloux, F. Metagenomic evidence for a polymicrobial signature of sepsis. Microb. Genom. 2021, 7, 000642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kai, S.; Matsuo, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Kryukov, K.; Matsukawa, S.; Tanaka, H.; Iwai, T.; Imanishi, T.; Hirota, K. Rapid bacterial identification by direct PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes using the MinION™ nanopore sequencer. FEBS Open Bio 2019, 9, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullar, R.; Chisari, E.; Snyder, J.; Cooper, C.; Parvizi, J.; Sniffen, J. Next-Generation Sequencing Supports Targeted Antibiotic Treatment for Culture Negative Orthopedic Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, V.; Ngwira, L.G.; Lewis, J.M.; Baker, K.S.; Peacock, S.J.; Jauneikaite, E.; Feasey, N. A systematic review of economic evaluations of whole-genome sequencing for the surveillance of bacterial pathogens. Microb. Genom. 2023, 9, 000947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.; McLellan, S.; Stokes, J.M. How AI can help us beat AMR. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinkel, M.; Paranjape, K.; Nannan Panday, R.S.; Skyttberg, N.; Nanayakkara, P.W.B. Clinical applications of artificial intelligence in sepsis: A narrative review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2019, 115, 103488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chakraborty, T.; Doijad, S.; Falgenhauer, L.; Falgenhauer, J.; Goesmann, A.; Hauschild, A.C.; Schwengers, O.; Heider, D. Prediction of antimicrobial resistance based on whole-genome sequencing and machine learning. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, K.N.; Street, T.L.; Sanderson, N.D.; Leach, L.; Morgan, M.; Eyre, D.W. Rapid clinical diagnosis and treatment of common, undetected, and uncultivable bloodstream infections using metagenomic sequencing from routine blood cultures with Oxford Nanopore. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.N.A.; Bauer, M.J.; Luftinger, L.; Beisken, S.; Forde, B.M.; Balch, R.; Cotta, M.; Schlapbach, L.; Raman, S.; Shekar, K.; et al. Rapid nanopore sequencing and predictive susceptibility testing of positive blood cultures from intensive care patients with sepsis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0306523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, A.D.; Coin, L.J.M.; Harris, P.N.A.; Cotta, M.O.; Bauer, M.J.; Buckley, C.; Balch, R.; Kruger, P.; Meyer, J.; Shekar, K.; et al. Optimising Treatment Outcomes for Children and Adults Through Rapid Genome Sequencing of Sepsis Pathogens. A Study Protocol for a Prospective, Multi-Centre Trial (DIRECT). Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 667680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, R.A.; Aghaeepour, N.; Bhattacharyya, R.P.; Clish, C.B.; Gaudillière, B.; Hacohen, N.; Mansour, M.K.; Mudd, P.A.; Pasupneti, S.; Presti, R.M.; et al. Harnessing the Potential of Multiomics Studies for Precision Medicine in Infectious Disease. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Ganesamoorthy, D.; Chang, J.J.; Zhang, J.; Trevor, S.L.; Gibbons, K.S.; McPherson, S.J.; Kling, J.C.; Schlapbach, L.J.; Blumenthal, A.; et al. Utilizing Nanopore direct RNA sequencing of blood from patients with sepsis for discovery of co- and post-transcriptional disease biomarkers. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Palacios, F.J.; Wang, D.; Reese, F.; Diekhans, M.; Carbonell-Sala, S.; Williams, B.; Loveland, J.E.; De María, M.; Adams, M.S.; Balderrama-Gutierrez, G.; et al. Systematic assessment of long-read RNA-seq methods for transcript identification and quantification. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 1349–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.M.; Peters-Sengers, H.; Reijnders, T.D.Y.; van Engelen, T.S.R.; Uhel, F.; van Vught, L.A.; Schultz, M.J.; Laterre, P.-F.; François, B.; Sánchez-García, M.; et al. Pathogen-specific host response in critically ill patients with blood stream infections: A nested case–control study. eBioMedicine 2025, 117, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, A.E.; Ortega-Santos, C.P.; Whisner, C.M.; Klein-Seetharaman, J.; Jasbi, P. Navigating Challenges and Opportunities in Multi-Omics Integration for Personalized Healthcare. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Dahlin, A. Multi-Omics Approaches to Resolve Antimicrobial Resistance. In Antimicrobial Resistance: Factors to Findings; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, J.; Xu, L.Q. Designing Interoperable Health Care Services Based on Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources: Literature Review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2023, 11, e44842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Illumina (e.g., MiSeq/NextSeq) | Ion Torrent (e.g., S5/Ion Proton) | Oxford Nanopore (e.g., MinION) | PacBio (e.g., Sequel IIe, HiFi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read Type | Shortread | Shortread | Longread | Longread (HiFi) |

| Read Length | 75–300 bp | 200–600 bp | 10–100 kb (up to Mb) | 10–25 kb (HiFi reads) |

| Accuracy (Raw Reads) | >99.9% | ~98–99% | ~90–95% (improving) | >99.9% (HiFi) |

| Diagnostic yield | ~0.3–15 Gb per MiSeq run | ~0.3–15 Gb per Ion S5 run | ~2–20 Gb per MinION run | ~30 Gb per Sequel IIe run |

| Turnaround Time | ~24–48 h | ~12–24 h | Real-time (~minutes–hours) | ~24–48 h |

| Library Prep Time | 4–6 h | 2–4 h | 1–2 h | 4–8 h |

| Cost per Gb | ~USD 31/Gb for some kits (e.g., 600-cycle) | Variable (~USD 30–300/Gb depending on chip and run) | Variable (~USD 11–33/Gb) | High (but decreasing) ~USD 31–43/Gb for HiFi |

| Instrument Cost | ~USD 99,000 for MiSeq/~ USD 210,000 for NextSeq 1000 | USD 75,500 for the S5 system | ~USD2999–4950 for the device | ~USD 495,000 for the Sequel II system |

| Strengths | High accuracy, established pipelines | Fast prep, scalable, affordable runs | Portability, longreads, real-time | High accuracy long reads (HiFi) |

| Limitations | Limited for large repeats or SVs | Lower accuracy than Illumina | Higher error rate, data variability | Higher cost, longer prep |

| Study | Cohort | Clinical Impact | Patient-Level Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. [129] | 130 sepsis patients (65 mNGS vs. 65 matched control) | Antibiotic regimen was changed in 72.3% in mNGS patients vs. 53.9% in control | Lower mortality in patients who had mNGS early (<24 h) vs. prolonged antibiotic exposure (22.2% vs. 42.9%) |

| Qin et al. [130] | 194 patients (112 with mNGS, 82 without) | Faster pathogen detection (mean 1.41 days via mNGS vs. 4.82 days via conventional methods) | 28-day mortality: 47.3% in mNGS group vs. 62.2% in non-mNGS group (p = 0.043) |

| Zuo et al. [131] | 277 patients | mNGS sensitivity: 90.5% vs. 36.0% for blood culture; mNGS guided antibiotic modification | 30-day survival data; higher pathogen reads by mNGS correlated with mortality risk |

| Pan et al. [132] | 69 sepsis patients | mNGS on blood + infection sites increased pathogen detection compared to conventional methods | Demonstrated that multi-site mNGS can inform more precise treatment decisions in ICU sepsis patients |

| Li et al. [133] | 308 sepsis patients (92 immunocompromised) | mNGS sensitivity much higher than culture (88.0% vs. 26.3% overall), prompting antibiotic changes in 60.1% of cases | Clinical benefit in 76.3% of patients |

| Chen et al. [134] | 97 candidemia patients (blood mNGS) | mNGS revealed microbial co-detections not seen by conventional diagnostics | 28-day mortality 44.3%; distinct microbial patterns in non-survivors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papamentzelopoulou, M.; Vrioni, G.; Pitiriga, V. Comparative Evaluation of Sequencing Technologies for Detecting Antimicrobial Resistance in Bloodstream Infections. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121257

Papamentzelopoulou M, Vrioni G, Pitiriga V. Comparative Evaluation of Sequencing Technologies for Detecting Antimicrobial Resistance in Bloodstream Infections. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121257

Chicago/Turabian StylePapamentzelopoulou, Myrto, Georgia Vrioni, and Vassiliki Pitiriga. 2025. "Comparative Evaluation of Sequencing Technologies for Detecting Antimicrobial Resistance in Bloodstream Infections" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121257

APA StylePapamentzelopoulou, M., Vrioni, G., & Pitiriga, V. (2025). Comparative Evaluation of Sequencing Technologies for Detecting Antimicrobial Resistance in Bloodstream Infections. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121257