Abstract

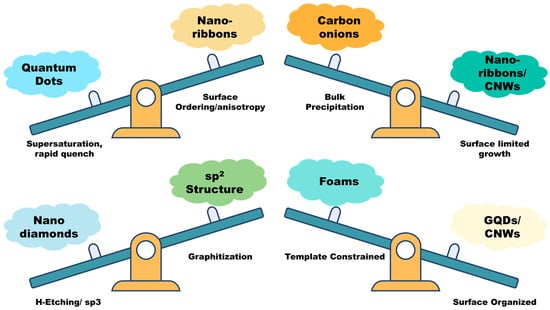

Graphitic nanomaterials have emerged as foundational components in nanoscience owing to their exceptional electrical, mechanical, and chemical properties, which can be tuned by controlling dimensionality and structural order. From zero-dimensional (0D) quantum dots, carbon nano-onions, and nanodiamonds to one-dimensional (1D) nanoribbons, two-dimensional (2D) nanowalls, and three-dimensional (3D) graphene foams, these architectures underpin advancements in catalysis, energy storage, sensing, and electronic technologies. Among various synthesis routes, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) provides unmatched versatility, enabling atomic-level control over carbon supply, substrate interactions, and plasma activation to produce well defined graphitic structures directly on functional supports. This review presents a comprehensive, dimension-resolved overview of CVD-derived graphitic nanomaterials, examining how process parameters such as precursor chemistry, temperature, hydrogen etching, and template design govern nucleation, crystallinity, and morphological evolution across 0D to 3D hierarchies. Comparative analyses of Raman, XPS, and XRD data are integrated to relate structural features with growth mechanisms and functional performance. By connecting mechanistic principles across dimensional scales, this review establishes a unified framework for understanding and optimizing CVD synthesis of graphitic nanostructures. It concludes by outlining a path forward for improving how CVD-grown carbon nanomaterials are made, monitored, and integrated into real devices so these can move from lab-scale experiments to practical, scalable technologies.

1. Introduction

Graphitic nanocarbons span a rich hierarchy of morphologies and bonding environments, enabling combinations of high electrical conductivity, large specific surface area, mechanical resilience, and tunable optical/electronic responses that are attractive for catalysis, energy storage, electronics, sensing, and biomedicine [1,2]. In this review, we adopt a dimensional taxonomy to study these materials, as follows: 0D (graphene quantum dots (GQDs), carbon nano-onions (CNOs), and Carbon Nanodiamonds (NDs)), 1D (graphene nanoribbons (GNRs)), 2D (vertically aligned carbon nanowalls (CNWs)), and 3D (interconnected graphene foams (GFs)).

Multiple synthesis routes can access graphitic phases, including arc discharge, laser ablation, electrochemical and liquid-phase methods, hydro/solvothermal chemistry, and template-assisted approaches [3]. These methods have delivered important benchmarks in crystallinity, throughput, and compositional tunability; however, precise morphology control across dimensions and direct device compatibility remain difficult to achieve simultaneously. For example, discharge and ablation excel in crystallinity but have limited scale control; electrochemical exfoliation favors layered products over curved shells; and solution routes offer chemical versatility yet often require post-processing and can struggle with uniform ordering.

Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) stands out for its ability to program nucleation, growth kinetics, and bonding via gas composition, temperature/pressure, substrate interactions, and (when used) plasma or hot-filament activation [4]. Crucially, CVD can form nanographitic structures directly on technologically relevant substrates with controllable dimensionality, from dots, onions, ribbons, and walls to foams, by tuning carbon supersaturation, hydrogen activity, surface energy, and geometric confinement. While CVD typically operates at elevated temperatures and must balance defect generation against growth rate and uniformity, its process tunability and mechanistic transparency make it uniquely suited for comparative, cross-dimensional synthesis.

Despite the extensive literature on individual families (e.g., graphene films or carbon nanotubes), unified perspectives linking CVD growth mechanisms across 0D–3D graphitic architectures remain underdeveloped [5,6].

This review addresses that gap by (i) formalizing the dimensional framework for nanographitic CVD, (ii) comparing how shared control parameters, precursor chemistry, catalyst/support choice, plasma/filament activation, and hydrogen-mediated etching govern nucleation pathways and structural evolution across dimensions, and (iii) highlighting convergent strategies (templating, alloy catalysis, and heteroatom doping) that translate between material classes.

We begin with the fundamentals of CVD activation and catalyst–substrate interactions, then survey synthesis routes and morphology–property relationships across 0D, 1D, 2D, and 3D graphitic systems, including hybrid or hierarchical architectures. The review concludes with comparative spectroscopic insights and an outlook on future directions for scalable, application-oriented CVD synthesis of graphitic nanomaterials.

2. Fundamental of Chemical Vapor Deposition

2.1. Chemical Vapor Deposition Techniques

CVD relies on the thermal decomposition or catalytic cracking of gaseous precursors on a heated substrate, producing carbonaceous or graphitic films [7,8]. In thermal CVD, hydrocarbons such as methane, acetylene, and ethanol decompose at elevated temperatures, typically between 700 and 1100 °C, over catalytic or bare substrates to yield sp2-bonded carbon materials [9]. The relatively high surface diffusion and uniform energy distribution often promote planar film formation, making thermal CVD well suited for graphene layers and carbon nanotubes under appropriate catalyst and temperature conditions. However, depending on gas chemistry, carbon flux, and substrate roughness, fibrous or three-dimensional porous morphologies can also emerge [10].

A related variant, hot-filament CVD (HFCVD), employs a resistively heated tungsten filament operating near 2000–2200 °C to dissociate methane and hydrogen molecules. The resulting atomic hydrogen etches disordered carbon and stabilizes sp2- or sp3-bonded phases, while the substrate remains cooler (around 950–1000 °C). By adjusting the hydrocarbon-to-hydrogen ratio and total pressure, HFCVD can produce diamond films, graphitic coatings, or fibrous carbon deposits, depending on the local balance between carbon radical generation and hydrogen etching [11,12].

Both thermal and hot-filament methods primarily rely on heat- and radical-driven activation without a deliberately sustained plasma, offering well-characterized chemistry and controllable process windows. These techniques remain fundamental to understand how temperature, carbon supersaturation, and surface diffusion collectively influence the dimensional evolution of graphitic nanostructures.

In contrast to purely thermal approaches, plasma-assisted chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) introduces energetic ions and radicals that activate gaseous precursors at comparatively low substrate temperatures. The presence of a plasma accelerates hydrocarbon dissociation and enhances surface mobility, enabling a wide range of morphologies depending on ion energy, flux direction, and substrate bias. Under higher plasma power or field-aligned conditions, vertically oriented structures such as CNWs or nanofibers are commonly obtained, while moderate ion energies favor conformal or amorphous graphitic films [13].

When the plasma is sustained by microwave radiation (typically 2.45 GHz ≈ 0.122 m), the method is termed microwave-assisted CVD (MACVD). Microwave excitation generates a uniform, high-density plasma at low pressures (1–10 Torr), efficiently dissociating hydrocarbon and hydrogen [14]. The resulting reactive environment supports the controlled synthesis of nanocrystalline diamond, graphitic coatings, or multi-dimensional carbon assemblies, with the final morphology dictated by the hydrogen concentration and plasma uniformity.

Hydrogen plays a dual role in these plasma-based processes: it selectively removes amorphous carbon while stabilizing sp2 and sp3 bonding configurations, thereby determining whether diamond-like, graphitic, or hybrid carbon phases develop [15,16,17]. The versatility of PECVD and MACVD allows fine-tuning of energy input and gas composition to access diverse carbon dimensionalities, from thin films to vertically aligned frameworks, highlighting their adaptability for both fundamental studies and scalable fabrication.

While activation mechanisms, i.e., thermal, filament-assisted, or plasma-driven, govern how gaseous precursors decompose, the eventual structure and morphology of deposited carbon are strongly influenced by the catalyst and substrate. These parameters determine how activated carbon species nucleate, diffuse, and precipitate to form specific graphitic architectures.

2.2. Catalyst and Substrate Effects

Catalysts play a pivotal role in dictating carbon solubility, diffusion, and precipitation behavior during CVD. Transition metals such as Fe, Ni, and Co possess high carbon solubility at elevated temperatures, enabling carbon atoms to dissolve into the catalyst and subsequently precipitate upon supersaturation to form graphitic shells, nanotubes, or nanofibers [18]. The size of catalyst particles determines the density of nucleation sites and ultimately the diameter and morphology of the resulting nanostructures [19]. Equally critical is the catalyst–substrate interface, which governs diffusion dynamics, adhesion strength, and the phase of the precipitated carbon that emerges (as sp2 or sp3) [20].

Non-reactive template supports such as NaCl [21], MgO [22], and Al2O3 [23] have been widely employed to minimize interdiffusion between the catalyst and substrate while providing confined nucleation sites. These supports also allow straightforward post-synthesis removal, yielding high-purity carbon nanostructures. For instance, iron nanoparticles supported on NaCl can catalyze the decomposition of acetylene at relatively low temperatures (~400–420 °C), producing CNOs with diameters in the range of 15–50 nm, often encapsulating Fe3C cores. Subsequent water dissolution of the salt template results in well-defined, metal-free CNOs [21].

Silicon-based systems illustrate the broader importance of substrate engineering in CVD. At temperatures above ~600 °C, Fe, Ni, and Co react readily with Si to form silicides such as NiSi/NiSi2, β-FeSi2, and CoSix. This silicidation consumes the active metal, restricts carbon diffusion, and suppresses graphitic nucleation, often yielding amorphous or turbostratic carbon unless a diffusion barrier is introduced [24,25,26]. The strong reactivity of bare silicon further encourages carbide formation, impeding sp2-carbon reconstruction. To address these challenges and enable direct CVD growth on silicon, several strategies have proven effective. Introducing ultrathin diffusion or passivation layers, typically SiO2, Al2O3, or TiN films less than 10 nm thick, prevents silicide formation and preserves the catalytic integrity of the metal [27,28,29,30]. Meanwhile, reducing the catalyst thickness to below ~3 nm, commonly achieved through sputtering or e-beam evaporation, minimizes strain mismatch and promotes controlled solid-state dewetting into nanoparticles, resulting in uniform and reproducible nucleation [31]. Surface pre-oxidation of the silicon wafer prior to metal deposition can also be beneficial, as a thin native oxide promotes uniform catalyst dispersion and serves as a mild diffusion barrier. PECVD offers an additional route to achieve graphitic growth at reduced substrate temperatures (≈450–600 °C). In this process, energetic ions and radicals generated by radio-frequency or microwave plasma efficiently dissociate hydrocarbon precursors, promoting vertical growth and controlled heteroatom incorporation without requiring complete carbide breakdown [32]. Recent advances in microwave plasma and surface-wave plasma CVD have further demonstrated that sp2-carbon networks can be synthesized at temperatures as low as ~300–500 °C through high-density, low-electron-temperature plasmas [33].

Process optimization also depends on hydrogen control. While the mechanistic role of hydrogen in selective etching and sp2 reconstruction has been discussed earlier in the context of plasma CVD, its partial pressure during catalyst-mediated growth critically influences the balance between carbon incorporation and structural ordering. Maintaining a moderate H2 concentration helps sustain graphitic nucleation without excessive etching, ensuring uniform film continuity under both thermal and plasma-assisted regimes. When these parameters, that is, barrier layer design, catalyst particle control, plasma activation, and hydrogen balance, are optimally coordinated, direct CVD growth of graphitic layers and nanostructures on silicon becomes feasible, as demonstrated by vertically aligned CNWs and graphene nanosheets growth on Si(100) at 650–700 °C using CH4/H2 gas mixtures [34].

Beyond catalyst and substrate engineering, feedstock composition can also significantly influence the cleanliness and structural quality of the resulting graphitic films. Jia et al. demonstrated that employing a Cu containing carbon feedstock promotes superclean graphene growth by mediating carbon decomposition and suppressing adventitious contamination during CVD [35].

Having established the fundamental activation mechanisms and examined how catalysts and substrates influence carbon nucleation and growth, it is evident that the underlying process parameters dictate the dimensional evolution of graphitic materials. The combined effects of precursor activation mode, catalyst particle size, substrate interaction energy, and hydrogen concentration determine whether carbon assembles into 0D, 1D, 2D, or 3D frameworks. The subsequent sections discuss these diverse graphitic architectures and their characteristic growth pathways under different CVD environments.

3. Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs)

GQDs are nanoscale particles, typically smaller than 10 nm, whose discrete energy levels arise from quantum confinement and edge or surface states, resulting in size- and structure-dependent optical and electronic properties. In carbon-based systems, the following four major families are recognized: (i) GQDs, which are nanoscale fragments of one or few graphene layers with sp2 bonded lattices and tunable edges; (ii) carbon quantum dots (CQDs), which are quasi-spherical, amorphous, or semi-crystalline nanoparticles rich in surface functional groups; (iii) carbon nanodots (CNDs), which consist of largely amorphous carbon cores lacking clear lattice order; and (iv) carbonized polymer dots (CPDs), which are crosslinked polymeric networks incorporating small graphitic domains [36].

Since the synthesis route dictates the structural order, size uniformity, and surface chemistry of GQDs, it directly governs their optical response and potential for device integration. Solution-phase methods, such as hydrothermal, solvothermal, or microwave-assisted, offer scalability and compositional flexibility, and are widely used for producing CQDs, CNDs, and CPDs (with heteroatom doping frequently demonstrated), though their photoluminescence often originates from surface states rather than intrinsic crystal cores [37,38,39].

In general, bottom-up solution-phase routes tend to yield CQDs, CNDs, or CPDs, whereas top-down and vapor-phase techniques are preferred for graphene-derived GQDs. Top-down approaches such as oxidative cutting and electrochemical exfoliation yield GQDs but often suffer from broad size distributions and defect-rich surfaces, leading to excitation-dependent photoluminescence [38]. Template-assisted methods, which confine precursor carbonization within mesoporous or micellar frameworks, achieve improved size control and doping precision but involve multiple processing steps and careful template removal. At the highest level of precision, on-surface molecular assembly under ultra-high vacuum produces atomically defined GQDs, though limited to small scales [40]. While solution-based and top-down strategies dominate in scalability and chemical versatility, the documents only indicate that these methods often produce colloidal, surface-functionalized QDs with PL strongly influenced by surface states, without explicitly stating that ligand stabilization restricts solid–substrate integration [39]. Vapor-phase techniques, in particular CVD, overcome these limitations by directly forming substrate-bound, edge-defined GQDs with minimal surface contamination and enhanced structural precision [37]. Building on this advantage, CVD has emerged as a versatile platform for producing GQDs with controllable dimensions, crystallinity, and edge configuration. Its vapor-phase nature allows direct growth on catalytic and non-catalytic substrates under well-defined thermodynamic conditions, enabling precise control over nucleation and carbon adatom mobility. Unlike solution-based methods that yield ligand-stabilized colloids, CVD growth proceeds in situ on solid surfaces, inherently compatible with device fabrication and integration. These characteristics make CVD an ideal approach for fabricating substrate-bound, high-purity GQDs with tunable morphology and uniform electronic characteristics, setting the foundation for the following discussion on bottom-up CVD routes.

3.1. Bottom-Up CVD Routes

Bottom-up CVD synthesis of GQDs provides a controllable route that combines structural precision with direct device integration. This vapor-phase approach enables in situ growth on technologically relevant substrates such as Cu, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), and Si [41,42,43], thereby eliminating the need for colloidal processing or capping layers. The resulting GQDs exhibit high crystallinity, clean interfaces, and edge-defined architectures ideally suited for optoelectronic and sensing applications [44,45].

The formation of GQDs in bottom-up CVD is governed by the competition between carbon adatom nucleation and lateral growth. On catalytic Cu foils, weak carbon–substrate interactions allow for fine control of this balance: at very low methane flow rates, nucleation dominates (N ≫ G), producing dense arrays of nanometer-scale islands that remain spatially confined as GQDs. As illustrated in Figure 1A, this nucleation-dominated regime yields discrete carbon islands that can subsequently be transferred onto flexible supports such as PDMS. When the CH4 supply is increased even slightly, lateral growth overtakes nucleation, causing rapid coalescence into continuous graphene films, demonstrating the high sensitivity of CVD growth to gas composition and flow rate [41].

On weakly interacting substrates such as h-BN, adatom mobility is intrinsically limited, leading to spontaneous island formation without the need for catalytic assistance. By tuning CH4/H2 ratios, the thickness and optical behavior of the dots can be adjusted: monolayer GQDs exhibit broad, red-shifted photoluminescence, whereas multilayer (>10 layers) GQDs display sharper, excitation-independent emission [42]. For more reactive substrates such as Si, rapid nucleation “freezes” adatoms before coarsening, and short dwell times (~1 min at 870 °C) yield ultra-pure one-to-three-layer GQDs whose stable blue emission arises from edge states rather than size confinement [43].

Remote plasma-assisted CVD extends this paradigm by introducing an etch–deposit equilibrium, enabling the growth of ultra-clean ~2 nm GQDs at 580–650 °C. Their sharp density of states and abundant edge sites enhance surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) activity, although plasma exposure can introduce structural defects if not carefully managed [44]. Moreover, a catalyst-free variant of plasma-assisted CVD further demonstrated that graphene nanoislands grown directly on Si/SiO2 can exhibit intrinsic quantum-dot behavior. Using microwave plasma CVD below 400 °C [46], 30–70 nm graphene domains that displayed clear Coulomb-blockade features and twofold degeneracy in low-temperature transport were obtained, confirming electronic quantization within CVD-grown islands. This work underscores that bottom-up vapor-phase routes can not only yield atomically defined GQDs, but also integrate quantum functionality directly onto semiconductor platforms.

In summary, bottom-up CVD approaches leverage the intrinsic thermodynamics of carbon nucleation on surfaces like Cu and h-BN, offering compatibility with standard CVD infrastructure and scalability to wafer-level substrates. Their ability to tune dot density, thickness, and emission through simple parameters, that is, gas flow, substrate type, and dwell time, makes them more practical than multi-step synthetic routes. Nonetheless, maintaining size uniformity and reproducibility across large areas remains a key challenge for translating CVD-grown GQDs into reliable device platforms.

3.2. Top-Down CVD-Derived Approaches

Beyond direct nucleation, alternative fabrication strategies have been developed where pre-formed graphene serves as the starting material. In this approach, pre-formed graphene films are selectively cleaved into nanoscale domains rather than being nucleated from gaseous precursors. For instance, electrochemical cutting of CVD graphene oxidatively “unzips” the lattice along defect lines, yielding 3–8 nm GQDs that preserve multilayer AB/ABC stacking order (Figure 1B–F). This retained stacking sequence is uncommon in nucleated dots and enhances interlayer coupling, making such GQDs promising for correlated-electron and quantum transport studies [47].

Alternatively, nanoscale patterning can be achieved by block copolymer self-assembly. Here, polymer micelles form ordered silica nanodot masks on the graphene surface, enabling oxygen plasma etching to sculpt uniform 10–20 nm GQDs. In this method, mask geometry defines dot size and pitch, whereas plasma dose controls edge oxygenation and photoluminescence intensity (Figure 1G) [48].

Although these top-down conversion routes provide exceptional precision in size and edge chemistry, these remain process-intensive and low-throughput, limiting their applicability for wafer-scale synthesis. Nevertheless, their atomically defined edges and tunable confinement make them invaluable research tools for probing quantum confinement, spin coupling, and correlated-electron effects where structural precision outweighs scalability.

3.3. Catalyst-Mediated CVD Strategies

While top-down CVD routes rely on physical or chemical fragmentation, introducing catalytic nanoparticles offers an additional degree of spatial and compositional control. Here, metal nanoparticles are often introduced as transient catalytic seeds to localize nucleation or tune dimensionality. Fe implantation into Si produces in situ Fe nanoparticles that nucleate GQDs; during high-temperature growth, these particles diffuse, leaving patterned, metal-free arrays [45]. While effective for deterministic positioning, this route introduces additional complexity and possible contamination. Pt sputtering provides another perspective: the size of Pt nanoparticles determines the carbon phase. Small, unstable droplets catalyze GQDs, whereas larger, stable particles persist to drive CNT growth, as shown in Figure 1H [49]. This highlights the ability of nanoparticle systems to map 0D–1D phase boundaries, but at the cost of extra processing steps and the risk of residual metal. Catalyst-mediated methods are less commonly adopted for applications because residual metals compromise purity and removal steps introduce complexity. However, these are still studied because these provide mechanistic insight into carbon phase evolution and enable site-selective nucleation, which is valuable for device integration where deterministic placement of QDs is needed.

3.4. Doped and Hybrid Systems

Expanding beyond morphology control, doping and hybridization strategies allow compositional and electronic tuning during CVD growth. In twisted bilayer graphene grown by CVD and supported on SiO2/Si, drop-cast CQDs exhibit twist-angle-dependent photophysics. When the twist angle (θ) is small (θ ≲ 11°), photoluminescence (PL) is enhanced due to the suppression of non-radiative charge transfer, making the CQDs more photoluminescent. However, at θ ≈ 0°, where the graphene layers are AB-stacked, and in single-layer graphene, PL is strongly quenched. As the twist angle increases (θ ≳ 15°), the bilayer graphene approaches SL-like behavior, and PL becomes weaker than in the small-angle regions. This behavior can be attributed to a competition between radiative and non-radiative electron-transfer channels, which is modulated by interlayer coupling and Fermi-velocity renormalization [50].

In addition to this observation, a novel mechanism for CQD formation has been demonstrated using ethanol on eggshell-derived Fe-Co/CaO catalysts. At approximately 850 °C with a 30 min dwell time, ethanol-derived OH-radicals are proposed to oxidatively corrode carbon nanofibers (CNFs) into ~2–3 nm CQDs, which then anchor to carbon nanotube (CNT) walls. Interestingly, the process is time- and temperature-dependent: shorter growth times (≈10 min) favor the formation of CNF/CNT hybrids, whereas longer growth times (≈60 min) or higher temperatures lead to the over-oxidation and consumption of CQDs, ultimately leaving only CNTs behind [51]. This observation reveals that CQDs can not only form by direct nucleation but also by secondary transformation of existing carbon nanostructures during the growth process, although their stability window remains narrow. These findings are important for developing new optoelectronic and sensing platforms, where controllable CQD formation is crucial.

Beyond structural integration, CVD also allows for atomic-level compositional tuning, such as the incorporation of nitrogen into GQDs (N-GQDs). The specific nitrogen doping configuration, whether pyridinic, pyrrolic, or graphitic, depends on the precursor chemistry and growth temperature. Pyridinic and pyrrolic nitrogen configurations introduce mid-gap states, which red-shift emission and enhance charge-transfer efficiency, while graphitic nitrogen improves conductivity and stabilizes edge states [52,53,54]. This capacity to precisely program dopant configurations in CVD showcases how process parameters can influence electronic structure in carbon materials.

While both N-GQDs and graphitic carbon nitride quantum dots (g-CNQDs) contain nitrogen, these are fundamentally different material classes. N-GQDs retain the sp2-bonded carbon lattice of graphene, with nitrogen atoms incorporated as dopants in graphitic configurations. These dopants locally modify the electronic structure, tuning photoluminescence and charge-transfer properties. In contrast, g-CNQDs feature an intrinsic sp2-hybridized C–N network derived from graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), where nitrogen forms part of the polymeric backbone rather than acting as a dopant. The optical and electronic behavior of g-CNQDs arises from π–π* and n–π* transitions within triazine or heptazine units, which lead to strong visible-light absorption and pronounced photocatalytic activity [55,56].

Despite both classes containing nitrogen, the differences between N-GQDs and g-CNQDs lie in their structural origins and the role of nitrogen. N-GQDs are synthesized through CVD or plasma-assisted routes by incorporating nitrogen into graphene. In contrast, g-CNQDs are formed via the thermal condensation of nitrogen-rich precursors, such as melamine or dicyandiamide, and cannot be synthesized through conventional hydrocarbon CVD. Recent low-pressure two-zone vapor-phase CVD routes have demonstrated the formation of g-C3N4 nanoparticles through confined sublimation–polymerization of melamine vapors at ~750 °C (region 1) onto TiO2 nanotube arrays held at ~500 °C (region 2) under a 40–133 Pa Ar atmosphere. This process enables the formation of uniform, sub-10 nm g-C3N4 nanoparticles that are anchored within the nanotube channels, preventing gas-phase aggregation and over-polymerization and offering a scalable route for photocatalytic applications, as shown in Figure 1I–K [57].

Such fine control over melamine polymerization at 750 °C (region 1) and 500 °C (region 2) suppressed defect formation and aggregation, allowing g-C3N4 to deposit as discrete nanoparticles rather than films. The resulting TiO2-NTA/g-C3N4 heterostructure formed efficient Z-scheme junctions, promoting rapid charge separation, and markedly enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution compared to pristine TiO2 or bulk g-C3N4. This work underscores how CVD process engineering, particularly reduced-pressure polymerization and nanoscale confinement, can be leveraged to achieve intimate semiconductor coupling and defect-controlled carbon nitride growth, a strategy extendable to other hybrid quantum or 2D architectures.

While GQDs represent 0D manifestations of sp2 carbon, their structural evolution under continued graphitization leads naturally to multi-shell architectures, the CNOs discussed next.

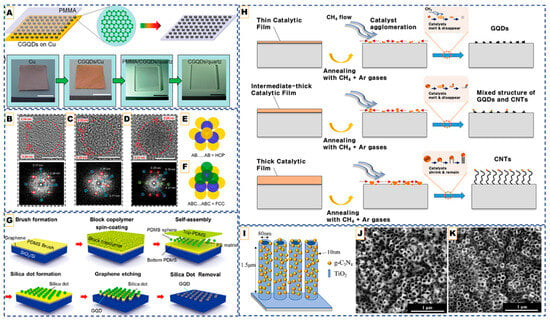

Figure 1.

CVD pathways for quantum dot fabrication: Catalyst-mediated CVD approach. (A) Top: Schematic diagrams of CGQDs formation and post-transfer. Down: Corresponding photographs. Scale bar: 1 cm. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [41]. Copyright 2013 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co., KGaA, Weinheim. (B–D) HR-TEM images (top) and FFT (bottom) of few-layer GQDs. (E,F) Scheme shows top view of HCP and FCC stacking, respectively, where yellow, blue, and green spheres represent atoms in A, B, and C types of layers, respectively. The scale bar represents 5 nm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [47]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society. (G) Top-down CVD-derived quantum dots. Schematic illustration of the fabrication of GQDs including the spin-coating of BCP, formation of silica dots, and etching process by O2 plasma. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [48]. Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society. (H) Formation mechanism of the GQDs, intermediates, and CNTs in terms of the catalytic-ion dose. (Top to down in the image) Reproduced from Ref. [49]. (I) The schematic diagram of TiO2-NTA/g-C3N4 (J,K) Corresponding SEM images of TiO2-NTA/g-C3N4 composites synthesized with 2.0 g and 0.2 g precursor loadings, respectively, showing tunable surface coverage and dot dispersion. Reproduced from Ref. [57].

4. Carbon Nano-Onions (CNOs)

CNOs, also known as onion-like carbons (OLCs), are multi-shell graphitic nanostructures composed of concentric sp2 carbon layers that resemble nested fullerenes. These are typically categorized based on their core structure into the following three main classes: solid (filled) onions, hollow onions, and core–shell architectures. The core–shell structures contain either a metallic nanoparticle or a void enclosed by the carbon shells [58,59]. While some authors use the term “yolk–shell” for the latter case, core–shell more accurately conveys the presence of a distinct core enclosed by graphitic shells. These variants share similar sp2 bonding but differ in internal morphology and, consequently, in their electronic and mechanical properties.

Several established methods yield CNOs, each with advantages and constraints. Arc discharge forms highly crystalline onions via plasma condensation but affords limited size control and scale [60]. Thermal conversion of nanodiamond at high temperatures produces well-ordered 3–10 nm onions, yet requires extreme heat and can induce coalescence. Flame pyrolysis from carbon-rich fuels (e.g., ghee, candle wax, and plant or waste oils) offers simple, low-cost, catalyst-free production of ~20–40 nm onions with a high surface area, though morphology depends strongly on flame conditions and collection substrates. Pyrolysis of molecular precursors such as hexachlorobenzene, sodium azide, or ferrocene can yield larger hollow onions (~50–100 nm) but often shows variable shell number and uniformity. Additional routes, including ion implantation, laser ablation, and microwave and electrochemical syntheses, can generate CNOs or functionalized variants, yet reproducibility, yield, and tight control over shell count remain recurring challenges. These constraints collectively motivate exploration of vapor-phase strategies for finer morphology control and improved scalability [60,61].

CVD offers fine control over carbon supply, temperature, and the local catalyst or template environment. It enables single-step synthesis of hollow, filled, or core–shell onions at moderate temperatures from hydrocarbon feeds. The method scales to large substrates and templates and balances gas-phase decomposition, surface diffusion, and precipitation to drive the transition from amorphous to graphitic multi-shell structures [60].

4.1. CVD Growth Mechanisms of CNOs

The formation of carbon onions and related graphitic shells by CVD is strongly influenced by the choice of hydrocarbon precursor, growth temperature, and especially the catalyst or template employed. CVD provides a controllable route where carbon is released from the precursor and reorganizes into multilayer sp2 shells under conditions defined by the substrate or nanoparticle surface. The resulting structure, metal-filled onions, hollow onions, or hollow graphitic shells, arises primarily from catalyst/template chemistry rather than from a universal kinetic model. For example, ethylene CVD over Co/MgO at 700 °C produces metal-encapsulated carbon onions that become hollow after acid removal [62], while methane CVD at 600 °C over Ni/Al yields both Ni-filled and hollow onions directly depending on the Ni particle state during growth [63]. Likewise, ethanol CVD at 775 °C coats oxide nanoparticles with few-layer graphene, and etching the oxide templates produces hollow graphitic shells shaped by the underlying particle morphology [64]. Across these systems, the catalyst or template determines whether carbon precipitates as filled, hollow, or template–replica shells, whereas precursor and temperature mainly affect the degree of graphitization and layer uniformity. These experimentally observed morphologies are further consistent with atomic-scale simulations, where DFT studies show that five-member carbon rings form more readily than six-member rings during carbon condensation. Such pentagonal loops introduce local curvature and act as intrinsic nucleation sites for closed graphitic shells, providing a microscopic basis for the curvature-driven closure observed during CVD growth and reinforcing the role of catalyst-induced surface conditions in selecting between filled and hollow onion structures [65].

Overall, the combination of core type (solid, hollow, and core–shell) and shell characteristics (thickness, defects, and dopants) is set by the synthesis strategy. Table 1 summarizes representative CVD-derived hollow and core–shell carbon nanostructures, highlighting the influence of catalyst/template type, feedstock, and growth temperature on resulting morphology and mechanism.

Table 1.

Overview of CVD-generated hollow and core–shell carbon nanostructures.

4.2. Metal-Catalyzed CVD Systems

In transition-metal-assisted CVD, metals such as Ni, Fe, and Si mediate carbon uptake and precipitation through a classical dissolution–diffusion–precipitation cycle [75]. Hydrocarbon molecules dissociate on the metal surface, and carbon atoms dissolve into the subsurface lattice. When supersaturation occurs, carbon precipitates outward, forming successive sp2 shells that encapsulate the catalyst particle. This process of solid-state graphitization under carbon supersaturation is fundamental to metal-driven CVD.

Nickel remains the archetypal catalyst due to its optimal balance of carbon solubility and catalytic activity. In Ni/Al2O3 systems [63], CVD growth at 600 °C enables smooth formation of hollow graphitic onions (<50 nm) through a Kirkendall effect, where outward carbon diffusion and partial metal contraction during cooling create a central void. The Al2O3 support prevents Ni sintering and maintains nanoparticle dispersion, ensuring uniform onion formation.

Alloying further refines this behavior. In Ni-Fe catalysts [75], methane decomposition between 750 and 950 °C forms a transient Fe-Ni-C austenitic phase with high carbon solubility. Upon cooling, carbon precipitates to yield multi-shell onions or core–shell particles depending on composition. Nickel accelerates hydrocarbon cracking [75,76], while iron enhances crystalline ordering, thus achieving polyhedral, hollow onions with 10–20 graphitic layers. At excessive carbon flux, carbide-encapsulated particles form, which can later be purified by acid etching.

Cobalt-based systems (e.g., Co/MgO) [62] demonstrate comparable control, with MgO acting as a dispersant and anti-sintering support. Adjusting Co content between 1 and 10 wt% tunes particle size and shell uniformity, producing hollow onions (10–50 nm) after removal of the oxide and metal residues.

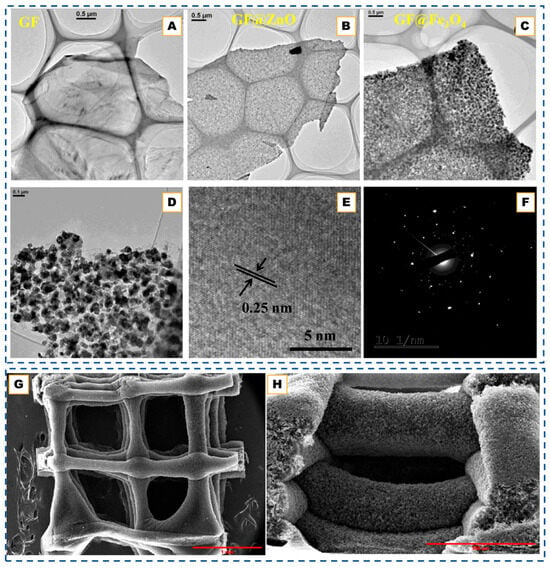

Although not metal-catalyzed, a recent study by Kim et al. [77] introduced a multilayered Core–Shell (MYS) framework featuring a carbon-bridge connection between the core and outer graphitic shells, offering complementary insights into concentric carbon-shell design relevant to CNO engineering. Their CVD-assisted synthesis employed sequential silane and acetylene deposition followed by controlled carbon oxidation, producing a Si@C@SiOx/Si/SiOx architecture in which the carbon bridge preserved electronic continuity while the void space buffered mechanical stress. This hierarchical design effectively mitigated interfacial isolation, a problem analogous to electron-transport loss in hollow CNOs, by enabling simultaneous accommodation of core expansion and retention of high conductivity. The MYS structure exhibited a high reversible capacity (2802 mAh g−1) and remarkable structural stability over repeated cycling, underscoring how bridged, multi-shell configurations can unify the advantages of hollow and core–shell carbons. Such strategies highlight the broader potential of CVD processes to create electronically coupled concentric carbon frameworks with tunable interfaces for energy-storage and catalysis applications. The structural evolution of the multilayered core–shell framework under different annealing conditions further demonstrates how thermal treatment governs carbon ordering and shell densification. This progression is illustrated below in Figure 2A–L.

These studies collectively highlight how catalyst composition, phase, and dispersion govern the precision achievable in CVD-grown graphitic shells. Under moderate temperatures (∼750–850 °C) and controlled carbon flux, transition-metal catalysts such as Ni, Fe, or Ni-Fe guide carbon dissolution and re-precipitation to yield multi-shell or polyhedral carbon onions whose graphitic thickness ranges from only a few layers up to several tens, depending on the catalyst and reaction conditions. Increasing temperature or employing catalyst phases with higher carbon solubility produces shells with higher graphitic crystallinity (lower ID/IG), indicating that the resulting morphology reflects the balance between carbon uptake, diffusion, and precipitation at the catalyst interface rather than a fixed layer-by-layer growth regime. When oxide templates or multi-component interfaces are introduced, similar CVD principles extend naturally to the formation of core–shell, hollow, or hierarchical carbon architectures, demonstrating the broad applicability of catalyst- and interface-mediated graphitic structuring across carbon-onion and related framework materials [76,77]. For instance, in hybrid systems such as Au@hmC-FeCo [59], Fe-Co nanoparticles catalyze local graphitization while the Au core preserves a central void, creating magnetically active core–shell composites. Similarly, SiO2 or Au@SiO2 spheres serve as inert templates, directing methane-based CVD growth to produce hollow or core–shell structures after etching. These designs illustrate how the controlled coupling of diffusion, catalysis, and templating can convert simple concentric onions into mechanically robust, electrically continuous architectures suitable for energy storage and catalytic applications, as can be seen in Figure 2M–R [69,70,71,78].

4.3. Oxide-Templated CVD

Beyond metal catalysis, oxide-templated CVD exploits geometric confinement rather than catalytic activity to organize graphitic shells, as developed by Rümmeli et al. [79]. Oxides such as Al2O3, MgO, and SiO2 provide high-energy surfaces that promote carbon rearrangement during hydrocarbon pyrolysis, allowing curved sp2 layers to replicate the template morphology, as shown in Figure 2S. Ethanol-based CVD over MgO, Al2O3, or TiO2 nanoparticles produces few-layer carbon shells with 3–7 graphitic layers, which can be functionalized with -OH or -SH groups following mild oxidation [64]. Similarly, SiO2 or Au@SiO2 templates yield uniform hollow or Au@graphene core–shell hybrids after HF etching [67]. In these systems, the template dictates curvature and shell integrity, while inert cores (e.g., Au) preserve structure during growth.

Recent refinements [66] achieve highly graphitized hollow spheres with exceptional uniformity and electrochemical durability. The oxide simultaneously serves as a mold and graphitization promoter, stabilizing curved carbon at the interface. Variants of non-isothermal CVD employ polyphenol vapor and SiO2-based templates, as shown in Figure 2T–V [68]. These further demonstrate tunable thickness and shell cohesion via temperature gradients. These approaches confirm that oxide templating provides a robust, metal-free pathway to carbon shells with high purity, uniformity, and chemical functionality.

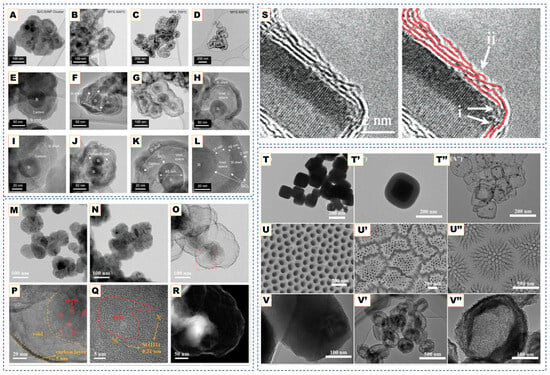

Figure 2.

(A–L). SEM images of graphitized hollow carbon spheres and yolk-structured carbon spheres fabricated by metal-catalyst-free chemical vapor deposition. Adapted from Ref. [77]. TEM images of (M) Si, (N) Si@C, and (O,P) pSi@void@NFC composites. (Q) HRTEM image of pSi@void@NFC composites. (R) HAADF-STEM image, and EDX mapping of Si, O, C, F, and N elements of pSi@void@NFC composites. TEM images of the hollow carbon onions obtained from various cobalt nitrate and basic magnesium carbonate ratios. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [71]. Copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH. (S) TEM images of a MgO crystal coated in graphene layers. Graphene layers are highlighted in red shows (i) Graphene layer roots on the MgO crystal. (ii) Wrinkle formation due to growth process. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [79]. Copyright 2007 American Chemical Society. (T,T′,T″) TEM images of cubic Cu2O@SiO2, and the final yolk–shell structured Cu@C after templates removal. (U,U′,U″) SEM images of AAO template and the resultant carbon nanotubes arrays. (V,V′,V″) TEM images of the mesoporous SiO2 particles and the porous carbon particles. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [68]. Copyright 2020 John Wiley & Sons.

4.4. Heteroatom-Doped and Functionalized Carbon Hollow Shells

Heteroatom doping marks a pivotal evolution in CVD-based carbon nanostructure design, transforming inert graphitic frameworks into electronically and chemically tunable architectures. Pristine carbon shells exhibit high conductivity and mechanical resilience but limited surface reactivity. The introduction of dopants such as B, N, P, or Al breaks this symmetry, introducing lattice strain, charge polarization, and active sites for catalysis and ion transport.

Each dopant contributes distinct electronic effects. Boron, being electron-deficient, induces p-type behavior and enhances oxidative catalytic activity. In boron-assisted CVD, co-feeding boron precursors with hydrocarbons yields substitutional incorporation within the sp2 lattice, stabilizing graphitic order while enriching π-electron localization [80,81]. Nitrogen, introduced through NH3-assisted CVD, donates electrons to the π-system, creating pyridinic, pyrrolic, and graphitic configurations that increase interlayer spacing, wettability, and active site density, benefiting both energy storage and catalytic processes [74]. Phosphorus doping via triphenylphosphine vapor introduces lattice expansion and localized charge variations that facilitate ion intercalation and redox reactions, improving electrode performance [73]. Co-doping strategies amplify these effects. Yu et al. [72], reported Al-B-N co-doped core–shell carbons produced by CVD, where electron-deficient (Al and B) and electron-rich (N) dopants cooperatively modulate charge distribution and defect stabilization. The resulting hierarchical graphitic frameworks exhibited enhanced conductivity, enlarged ion-accessible surface area, and superior cycling stability, demonstrating the synergistic potential of multi-element doping in tuning the structural and electronic landscape of CVD-derived carbon nanostructures.

The controlled assembly of sp2-bonded carbon shells demonstrates how CVD can tailor concentric architectures by manipulating diffusion, catalysis, and templating. Yet, CVD’s versatility extends further: by adjusting gas composition, temperature, and plasma parameters, it can stabilize sp3-bonded carbon and produce NDs with equally rich dimensional and defect control. To underscore this broader capability of vapor-phase synthesis, the following section examines the mechanisms and parameters that govern NDs formation, contrasting the sp2-based onion structures with sp3-dominated NDs frameworks.

5. Carbon Nanodiamonds (NDs)

The synthesis of NDs through CVD represents one of the most versatile manifestations of carbon chemistry under non-equilibrium conditions. Unlike detonation or high-pressure high-temperature (HPHT) processes, which rely on explosive quenching or pressure–temperature regimes analogous to Earth’s mantle, CVD permits atomistic control of carbon bonding pathways through the independent regulation of radical flux, hydrogen activity, and substrate energetics. This decoupling of thermodynamic and kinetic variables allows for the stabilization of sp3-bonded carbon far from equilibrium via hydrogen-mediated surface reactions, giving rise to diverse ND forms ranging from discrete particles to continuous ultra-nanocrystalline films [82,83,84].

NDs generated by CVD can be broadly grouped into several categories distinguished by their structural origin and synthesis environment. The first comprises loose, substrate-free ND particles that nucleate directly in the gas phase of CH4/H2 plasmas or hydrocarbon flames. Studies have reported evidence of gas-phase NDs formation even when the substrate was physically isolated from the plasma, suggesting that homogeneous nucleation can occur under sufficiently high carbon supersaturation and hydrogen radical flux (Figure 3A,B) [84]. Nitrogen addition during MPCVD consistently enhances secondary nucleation, leading to dense, ultrafine grains characteristic of ultra-nanocrystalline diamond films. In these environments, increasing nitrogen flow modifies plasma chemistry, most notably by strengthening C2 and CH radical emission, and drives repeated renucleation that reduces grain size to only a few nanometers. A further category within CVD-grown nanodiamond materials includes films whose microstructure and properties are deliberately tuned through controlled incorporation of nitrogen or other additives, which alter grain boundary chemistry, sp2/sp3 ratios, and defect populations, as demonstrated in the nitrogen-doped UNCD films discussed in these studies [85,86,87]. Increasing C2 concentration or nitrogen doping promotes frequent re-nucleation, yielding ultrafine grains consistent with UNCD textures. A third category encompasses doped NDs intentionally engineered to host color centers such as NV, SiV, and GeV during or after growth. These are typically formed under controlled nitrogen or Group-IV precursor additions in microwave plasma environments optimized for defect incorporation, as shown in Figure 3C,D [88,89]. Finally, there are seeded-film NDs, nuclei derived from detonation, or HPHT powders that survive the initial etching phase and serve as crystallization sites for further growth. Their stability depends on local hydrogen and oxygen concentrations, which determine whether small seeds (<4 nm) are etched away or stabilized for coalescence [90,91].

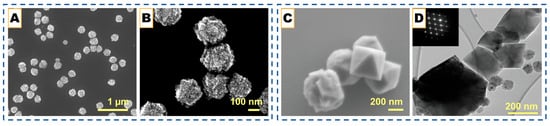

Figure 3.

Morphological signatures of NDs’ formation under distinct CVD regimes. (A,B) Gas-phase nucleation through pinhole-assisted collection, confirming particle condensation independent of the substrate. Reproduced from Ref. [84]. (C,D) Seeded-film growth on Si(100) demonstrating selective seed survival and crystalline faceting; inset diffraction pattern confirms sp3 order. Reproduced from Ref. [88]. Copyright 2019 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Although non-CVD methods such as detonation, HPHT, and laser ablation are indispensable for bulk production, these inherently lack the kinetic precision that defines CVD. Detonation NDs, formed by the adiabatic expansion of carbon-rich explosives, contain extensive sp2 shells together with metal impurities, and, therefore, require aggressive purification using strong oxidizing acids to remove graphitic shells and contaminants [92,93]. HPHT methods produce highly crystalline but micrometric diamonds unsuitable for nanoscale control, while laser and arc techniques generate amorphous mixtures with uncontrolled defect chemistry. In contrast, CVD offers a continuous tuning capability between amorphous carbon, nanographite, NDs, and single-crystal diamond, all within a unified plasma–chemical framework [82,83].

CVD Routes and Control Parameters

Among CVD modalities, microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition (MPCVD) remains a leading approach for ND and UNCD-like film synthesis because it provides controllable plasma environments and stable hydrogen chemistry while allowing precise adjustment of CH4/H2 ratios and power inputs [83,85]. Under nitrogen addition, or more generally, under conditions that increase the intensity of C2 and CH radicals, secondary nucleation is strongly promoted, yielding ultrafine grains and dense grain-boundary networks characteristic of UNCD structures [85,86,87]. Hot-filament CVD, although technologically simpler, is limited by filament heating and thermal loading, yet remains useful for low-cost diamond and ND coatings when filament temperature and spacing are properly controlled [93]. Alternative plasma geometries, including linear-antenna or vertical-substrate MPCVD arrangements, extend diamond growth to larger areas or exploit spatial gradients in hydrogen and temperature to reveal systematic variations in nucleation and grain size across a single wafer [94].

Oxygen plays a decisive role during early growth: at sufficiently low concentrations, it can suppress sp2 phases, whereas concentrations approaching or exceeding ~1 vol% under typical MPCVD pressures rapidly etch ND seeds and suppress nucleation unless a pre-grown diamond layer is present [91]. Seed survival is especially sensitive during the incubation stage, where small detonation NDs (<4 nm) can be removed by hydrogen-driven etching before contributing to film coalescence [90]. Substrate seeding density and nucleation enhancement strategies, therefore, remain critical; seed densities at or above ~1011 cm−2 are typically required for the formation of continuous ND films [82,90].

Nitrogen constitutes another key parameter, modifying plasma chemistry and grain-boundary structure. Sub-percent additions enhance secondary nucleation and smooth film morphology, whereas higher nitrogen concentrations increase sp2-rich grain boundaries and degrade structural and mechanical uniformity [86,87]. Inert gases such as argon or helium also influence plasma chemistry; argon dilution, in particular, increases C2 emission and can facilitate ultrafine grain formation [85,95], while helium dilution reduces C2 to below detectable levels without preventing nanocrystalline growth [96].

Across all CVD processes, the fundamental growth mechanism remains based on CH3 incorporation at hydrogen-terminated sp3 sites, with atomic hydrogen continually abstracting and restoring surface hydrogen to generate active sites for further carbon addition [82,97,98]. Although the relative contributions of CH3-based versus C2-assisted pathways depend on gas mixture and plasma conditions, the CH3-H mechanism remains consistently supported for microcrystalline and nanocrystalline regimes across the systems examined.

The major limitations identified in the literature stem from hydrogen-mediated etching during incubation, renucleation-driven grain boundary formation under high reactive-carbon or nitrogen flux, and process sensitivity to oxygen concentration, which are factors that can delay coalescence or increase sp2 content if not carefully managed [83,87,90].

Improvement strategies focus on kinetic control rather than equipment redesign. Programmed incubation sequences, in which the CH4 fraction is briefly elevated during seeding to protect small nuclei and then reduced once coalescence begins, have proven effective in stabilizing sub-4 nm seeds [90]. Controlled trace oxygen dosing (<2%) suppresses sp2 formation while minimizing oxidative seed loss, particularly in low-temperature MPCVD on glass substrates [91,99].

Nitrogen can be harnessed as a deliberate promoter of re-nucleation if maintained below threshold levels that induce graphitic boundary growth [86,87]. Argon-assisted regimes exploit C2 chemistry for ultrafine grain refinement while retaining sufficient hydrogen selectivity [85,100]. Reactor designs incorporating built-in hydrogen/temperature gradients accelerate optimization, while OES feedback enables real-time control of the CH3/H ratio in the ND growth window [85,94].

In parallel, advances in dopant control and color-center engineering demonstrate how ND synthesis by CVD can be integrated with quantum materials design. Co-feeding nitrogen or Group-IV precursors allows for in situ formation of NV, SiV, or GeV centers without post-growth implantation, provided that plasma chemistry balances defect incorporation with grain-boundary suppression [88,89]. In summary, CVD offers a uniquely tunable platform for controlled ND synthesis, enabling manipulation of sp3 nucleation and growth pathways through coordinated control of CH3 flux, hydrogen concentration, dopant chemistry, and plasma geometry. The mechanistic framework, anchored in the interplay between deposition and hydrogen-mediated etching, has matured to the point that ND synthesis can now be regarded as a continuum rather than a discrete technique. The path forward lies in mastering plasma–surface interactions to balance re-nucleation, seed survival, and impurity control with atomistic precision, while continuing to refine plasma modulation and scalable reactor architectures.

Having explored how CVD can be tuned to stabilize sp3-bonded carbon in the form of NDs, we now turn to its ability to engineer one-dimensional sp2-bonded structures. GNRs occupy an intermediate dimensionality between zero-dimensional dots and two-dimensional sheets; these combine high carrier mobility with tunable bandgaps defined by their width and edge configuration. The next section surveys CVD routes to GNRs, highlighting how substrate anisotropy, kinetic control, and template confinement transform inherently two-dimensional graphene growth into ribbon-like architectures.

6. Graphene Nanoribbons (GNRs)

GNRs combine the high carrier mobility of graphene with tunable, width-dependent bandgaps, making them promising candidates for next-generation logic, interconnect, and quantum devices [7]. Early studies of graphene CVD on germanium established that substrate crystallography governs both domain symmetry and growth anisotropy. On Ge(110), graphene develops elongated, anisotropic domains due to differences in armchair and zigzag edge propagation, while Ge(100) produces more symmetric, often hexagonal grains [101]. Subsequent work comparing thermal CVD and PECVD growth on Ge surfaces showed that graphene morphology, strain state, and grain elongation depend strongly on the underlying orientation: Ge(001) and Ge(110) promote elongated domains and directional growth, whereas Ge(100) tends toward more compact grains. PECVD further enabled lower-temperature growth and revealed systematic tensile or compressive strain signatures depending on the method, reinforcing the critical role of Ge orientation in determining graphene shape, strain, and growth kinetics [102].

In parallel, independent thermal annealing studies revealed how post-growth high-temperature treatments transform ribbon edges and lattice structure. Annealing up to 2800 °C progressively heals point defects, straightens lattice fringes, and converts reactive open ribbon edges into single-, double-, and multi-loop closures, yielding more graphitized and structurally ordered nanoribbons with reduced Raman D-band intensity [103]. These insights clarified how GNR edges stabilize under extreme thermal processing.

Ge(001) CVD experiments then demonstrated that narrow armchair-edge graphene nanoribbons can form spontaneously during methane CVD, exhibiting smooth edges and semiconducting transport behavior, although unseeded growth typically yields two degenerate ⟨110⟩ orientations and substantial width variability [104,105]. Building directly on crystallographic and strain insights from earlier CVD studies, this work positioned Ge(001) as a platform for inherently anisotropic ribbon formation.

Further refinement arrived with seeded CVD approaches. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as PTCDA and pentacene enable quasi-synchronous nucleation, suppress spontaneous methane nucleation, and yield narrower, more uniform ribbons. Under ~920 °C and ~0.5–0.9% CH4, seeded ribbons reach ~3–4 nm widths with polydispersities of 11–15%, and exhibit strongly anisotropic growth where length increases far more rapidly than width [106].

Orientation control was subsequently achieved using vicinal (miscut) Ge(001) substrates, which break the symmetry between the two ⟨110⟩ directions. Under slow growth, more than 90% of ribbons align unidirectionally, and sub-10 nm semiconducting ribbons incorporated into FETs reach on/off ratios of ~570 and conductance values of ~8 µS [107].

Kinetic Monte Carlo modeling later reproduced these experimental regimes and attributed high-aspect-ratio ribbon formation to direction-dependent stabilization and conversion of edge-bound precursor species. At low precursor densities, which correspond to slower growth, ribbons tend to extend mainly along their length, while higher precursor densities encourage more lateral growth, and, therefore, produce ribbons with lower aspect ratios [108]. Beyond chemically driven anisotropy, template- and etching-guided strategies introduce physical confinement as a means to direct nanoribbon growth. In these approaches, directional control is decoupled from substrate chemistry. Chen et al. demonstrated CVD growth inside pre-etched monolayer-deep h-BN trenches, typically narrower than 10 nm, whose zigzag-oriented walls constrain the GNR edges and enforce crystallographic alignment. The ribbons grow embedded within the dielectric host, eliminating any need for post-growth transfer, and AFM measurements confirm atomically smooth, epitaxial interfaces. Room-temperature transistors fabricated from sub-10 nm embedded ribbons exhibit on/off ratios exceeding 104 [109].

In contrast, Cai et al. realized a lithography-free, template-free method on liquid Cu substrates, where hydrogen-regulated, comb-like surface etching spontaneously forms parallel channels that guide ribbon growth. This process yields monolayer GNRs with smooth edges, micrometer-scale lengths (≈3–5 μm), and controllable widths, including sub-10 nm ribbons, all aligned through self-assembly on the liquid metal surface [110].

Regardless of substrate, successful ribbon formation relies on pronounced kinetic asymmetry in which the axial growth velocity greatly exceeds the lateral velocity, as seen in Figure 4A–E [111]. On Ge (001), selective C-Ge bonding along ⟨110⟩ facets promotes armchair-edge propagation while suppressing side attachment, as evident from Figure 4F–O [106,107]. In hydrogen-moderated liquid-Cu systems, a tuned H2 flux preferentially etches lateral sp2 edges while preserving elongation [110]. This anisotropy stabilizes narrow, self-limiting ribbons and delays coalescence into two-dimensional films. The electronic consequence parallels the geometric one: as Son, Cohen, and Louie showed, armchair edges produce width-dependent semiconducting bandgaps, whereas zigzag edges host spin-polarized states [112].

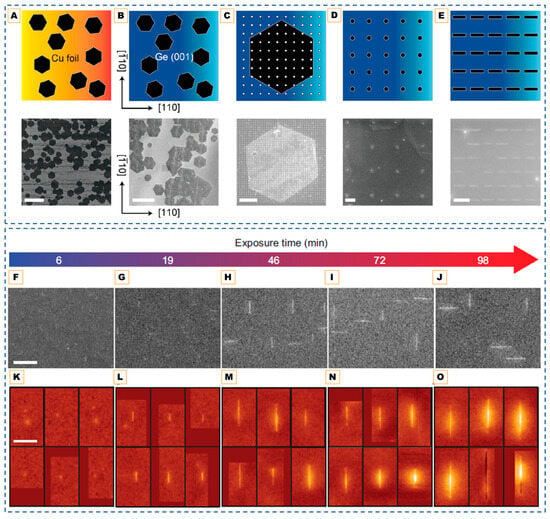

Figure 4.

(A) Hexagonal crystals of monolayer graphene are grown on Cu foil. (B) The hexagonal graphene crystals are transferred onto Ge(001). (C) Arrays of Al dots are patterned on top of the hexagonal graphene crystals on Ge(001) via electron-beam lithography, development, Al deposition, and lift-off. (D) The exposed graphene that is not protected by the Al masks is etched using an oxygen reactive ion plasma and then the Al masks are etched with H3PO4, resulting in an array of circular graphene seeds on Ge(001). (E) Graphene is grown from the seed array via CVD. Scale bars are 80 μm (A), 40 μm (B), 4 μm (C), and 200 nm (D,E). Reprinted with permission from Ref. [111]. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. (F–J) SEM images of nanoribbons after CH4 exposure times of 6, 19, 46, 72, and 98 min. Scale bar is 200 nm. (K–O) STM images of nanoribbons after exposure times of 6, 19, 46, 72, and 98 min (applied bias = 2 V, tunneling current = 0.1 nA). Scale bar is 100 nm. Color is scaled to topographic height, with dark red being lowest and light yellow being highest. Reproduced from Ref. [106].

Uniform nucleation is equally critical for dimensional control. Without regulation, ribbons nucleate stochastically, which leads to broad width distributions. Seed-assisted growth plays a central role in controlling graphene nanoribbon nucleation on Ge(001). As demonstrated in [106], PAH molecules such as PTCDA and pentacene act strictly as nucleation seeds, defining where growth begins and ensuring synchronous ribbon initiation, but they do not lower the activation energy for C–C bond formation. Their function is limited to setting spatially uniform nucleation sites, which reduces stochastic variability in ribbon width and spacing. Building on this principle, Shekhirev et al. extended seed-based growth to lower temperatures, showing that thermal decomposition of PTCDA between 500 and 650 °C produces oxygen-functionalized nanoribbons directly on insulating substrates, enabling immediate device operation as gas sensors without transfer steps [113].

Substrate–Template Synergy

Recent advances in graphene nanoribbon (GNR) synthesis demonstrate that geometric confinement and surface-directed growth can complement chemically driven anisotropy. One example is the use of pre-etched monolayer-deep h-BN trenches, typically a few to several nanometers wide, which constrain CVD growth along crystallographically defined zigzag directions. Because the graphene forms inside the trenches, these structures provide built-in dielectric encapsulation and eliminate the need for post-growth transfer steps [114].

On germanium substrates, anisotropic growth on Ge(001) surfaces produces elongated armchair-oriented ribbons whose aspect ratios arise from the strong dependence of growth velocity on the relative alignment between the graphene armchair direction and Ge(110) surface lattice vectors [111]. Under seeded growth conditions, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as PTCDA or pentacene act as nucleation seeds, enabling more uniform and synchronous ribbon initiation while suppressing spontaneous methane-driven nucleation [106].

Distinct from Ge-based growth, hydrogen-regulated etching on liquid copper creates comb-like channels that guide graphene growth without lithography. Hydrogen selectively etches surface features to generate parallel channels, producing highly aligned, micrometer-scale graphene ribbons, including sub-10 nm structures formed through balanced growth and etching dynamics [110]. These approaches demonstrate that physical confinement, surface reconstruction, and gas-mediated etching can each be tuned to promote directional growth and suppress film coalescence.

The electronic behavior of the resulting ribbons follows well-established edge-structure principles: armchair GNRs exhibit width-dependent semiconducting bandgaps, whereas zigzag edges support spin-polarized states, as described by the theoretical framework provided in the uploaded reference on GNR electronic structure [112].

Beyond high-temperature growth on Ge or Cu, lower-temperature routes have also been demonstrated. Thermal decomposition of PTCDA between 500 and 650 °C produces oxygen-terminated armchair GNRs directly on insulating substrates, enabling immediate device fabrication. These films exhibit ambipolar response and strong sensitivity to a range of volatile organic compounds, allowing their use as GNR-based gas sensors without transfer or high-vacuum processing [113].

Finally, post-growth thermal annealing of GNRs at temperatures up to 2800 °C induces significant structural reconstruction, including the healing of point defects and transformation of open edges into single-, double-, and multi-loop edge closures, as confirmed by transmission electron microscopy and Raman spectroscopy. These reconstructions reduce disorder and improve graphitic ordering, illustrating how thermal processing can refine the structural quality of nanoribbons after growth [104].

Recent CVD studies highlight that although anisotropic growth on Ge(001) reliably produces sub-10 nm armchair-edge graphene nanoribbons with high alignment and aspect ratios above 10 [107], controlling width uniformity remains challenging. Experiments show that growth rate strongly affects lateral expansion, with slower growth (achieved through higher H2:CH4 ratios) producing more elongated shapes, whereas faster growth leads to broader, less anisotropic structures [107].

Complementary kinetic Monte Carlo modeling indicates that anisotropic ribbon formation requires direction-dependent stabilization of graphene precursor species and anisotropic activation energies for row nucleation and row growth [108]. These models also reveal that the diffusion length of precursor species governs the transition between high-aspect-ratio growth and lateral widening [108].

Beyond Ge(001), hydrogen-regulated etching on liquid copper produces comb-like channels that guide growth and enable large-area aligned GNR arrays, where hydrogen flow rate strongly controls channel width and uniformity [110]. Similarly, seed-defined nucleation using polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons enables synchronized ribbon initiation and suppresses uncontrolled nucleation on Ge(001), improving reproducibility [106]. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that while high-aspect-ratio ribbons are achievable, precise width control remains highly sensitive to growth rate, precursor diffusion, hydrogen etching dynamics, and nucleation density. Continued development of predictive models that couple nanoscale mechanisms to macroscopic growth parameters is needed to transition from empirical optimization to fully controlled CVD synthesis.

Having examined the anisotropic, substrate-guided growth of GNRs, the discussion now advances toward CNWs, vertically oriented, few-layer graphene architectures that embody the transition from lateral confinement to field-directed vertical assembly. This dimensional progression from ribbon to wall highlights how CVD growth can be reoriented from surface-limited kinetics to plasma-assisted, self-organized frameworks.

7. Carbon Nanowalls (CNWs)

CNWs, vertically aligned, few-layer graphene networks, represent one of the most distinctive nanocarbon architectures attainable through CVD. These combine the high electrical conductivity of graphene with the exceptional surface-to-volume ratio of porous graphitic networks, positioning them as multifunctional materials for catalysis, energy storage, sensing, and protective coatings.

The origin of CNW research can be traced back to as early as 2002 [34]. The study demonstrated that carbon radicals in plasma environments self-organize into vertically aligned carbon walls on sapphire due to charge buildup on the insulating substrate, which generates strong transverse electric fields that direct CNW growth instead of CNTs. Subsequent study expanded the understanding of CNW synthesis by showing that well-defined surface-bound structures could be formed on plain silicon without metal catalysts, while freestanding CNWs fabricated on metallic supports confirmed their mechanical robustness and scalability, proving that vertical graphene frameworks could be detached and handled without collapse [115]. Together, these studies established CNWs as a field-directed, plasma-grown carbon system, where morphology is governed by a triad of carbon addition, hydrogen etching, and electric-field alignment. Building on this foundation, subsequent research explored remote PECVD for the controlled fabrication of vertical graphene (VG), where the growth direction and structural characteristics are tuned by adjusting plasma density, growth temperature, and ratio between carbon source and carrier gas, as shown in Figure 5 [116].

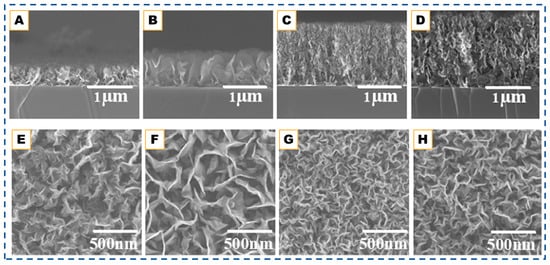

Figure 5.

SEM sectional (A–D) and top-view (E–H) images of VG which are deposited at 600 °C but with different plasma powers, i.e., 100 (A,E), 200 (B,F), 300 (C,G), and 400 W (D,H), respectively. Reproduced from Ref. [116].

Further mechanistic clarity emerged from high-resolution TEM studies. TEM images revealed that nucleation initiates at mismatched or curved graphitic layers within a thin amorphous-carbon buffer layer on the substrate, or alternatively from carbon onions whose outer shells provide defective graphitic curvature that seeds upright sheets. Once nucleated, the walls extend vertically through the diffusion of carbon adatoms along the graphene surfaces toward active step edges, where attachment governs the growth rate. The characteristic curved, terraced steps observed in TEM directly map onto mass-flow simulations, confirming that carbon adatom concentration gradients drive upward propagation. Growth ultimately terminates when adjacent graphene layers merge to form seamless, closed edges, explaining the tapered morphology and finite height of CNWs and VG structures [117].

Most recently, efforts to expand CNW synthesis toward temperature-sensitive and flexible substrates have led to the development of radical-injection PECVD (RI-PECVD) routes capable of achieving catalyst-free vertical growth at temperatures as low as 225 °C, a significant reduction from the conventional 600–800 °C range required in earlier PECVD systems. Systematic SEM, Raman, and TEM analyses revealed that CNW formation at this ultra-low temperature proceeds through the same four-stage sequence established for high-temperature growth—nano-island formation, edge-site nucleation, vertical sheet emergence, and wall thickening—yet with reduced precursor fluxes and radical diffusivities that slow the initiation stages. Importantly, despite the lower processing temperature, the resulting CNWs exhibit multilayered graphene walls, high verticality, and exceptionally high wall densities, which enhance hydrophobicity and surface roughness. This work demonstrates that the fundamental field-assisted, radical-driven mechanism is preserved even at low thermal budgets, enabling CNW synthesis on broader classes of substrates and opening pathways for scalable, low-temperature device integration [118].

Parallel advances have also targeted architectural control of CNWs through multistep plasma growth. A two-stage RI-PECVD and CCP-CVD process was shown to produce hierarchical multi-branched CNWs with wall densities and nanoscale spacing unattainable in single plasma modes. In this scheme, RI-PECVD first creates vertically aligned graphene walls with abundant edge sites, while the subsequent low-power CCP step, with reduced hydrogen etching and modified CH and C2 radicles chemistry, induces lateral nucleation and branching. Time-resolved SEM and TEM reveal that carbon nuclei form on wall tops and evolve into secondary nanosheets, yielding a high-surface-area superhydrophobic CNW network. Although the core vertical growth mechanism still relies on the balance between carbon addition and hydrogen etching, this dual-regime approach offers enhanced morphological tunability for sensing, catalytic, and surface functional applications [119]. More recently, a comprehensive plasma physics perspective [120] clarified why different PECVD methods yield such diverse CNW morphologies. Systematic analysis of ion and radical interactions shows that CNW growth is sustained only within a narrow window of ion energy and ion flux, where bombardment is sufficient to activate edge sites yet not strong enough to amorphized the carbon network. This framework explains why remote, inductively coupled, and radical injection plasma systems outperform conventional CCP discharges: they decouple ion energy from radical density, allowing independent control over defect content, sheet verticality, nucleation rate, and wall density. The review further demonstrates that electric field strength in the plasma sheath remains the primary factor enforcing vertical alignment, as alterations to the substrate field environment can switch growth from vertical to planar. These insights provide a unifying mechanistic foundation that links historical observations with modern PECVD strategies and clarifies why plasma configuration, rather than temperature alone, governs CNW architecture [120].

A complementary direction has focused on using substrate geometry to guide CNW arrangement. Nanoporous anodic alumina templates have shown that pore diameter and membrane thickness regulate nucleation density, wall spacing, and growth direction. Larger pores promote well-separated vertical walls, whereas smaller or curved pore edges trigger mixed horizontal and vertical nucleation as flakes merge across confined regions. Substrate thickness further influences wall height by modifying local thermal and electrical conductivity. Although this approach does not alter the plasma-driven mechanism itself, it demonstrates that surface topography can imprint spatial order onto CNW assemblies, providing an additional route to control density and architecture for patterned or conformal vertical graphene networks [121].

From a heteroatom-doping standpoint, post-treatment nitrogen incorporation has emerged as an effective route to enhance the electrochemical activity of carbon nanowalls [122]. Direct current plasma enables the introduction of pyridinic, pyrrolic, and graphitic nitrogen species into the graphene edges and vacancy sites, where their lone-pair and π-electron interactions create highly accessible redox-active centers. Although the total nitrogen content remains modest, the resulting defect-rich surface dramatically increases specific capacitance, rising from about 105 F g−1 in pristine CNWs to nearly 600 F g−1 after doping, due to improved charge transfer, wettability, and pseudocapacitive contributions. DFT analyses further show that nitrogen binds preferentially at vacancy-rich regions, confirming that doping stability and electrochemical enhancement are governed by defect chemistry rather than bulk nitrogen concentration. Together, these findings highlight heteroatom doping as a practical and powerful means to transform CNWs from passive, vertically aligned carbon architectures into highly active electrode materials suitable for micro-supercapacitors and other electrochemical devices [122].

In parallel with electrochemical enhancements achieved through heteroatom doping, other studies have examined the intrinsic transport properties of CNWs to assess their suitability for microelectronic and sensing platforms. CNWs synthesized on platinum thin films and interdigitated electrodes exhibit well-defined interface-dependent behavior, transitioning from Schottky-like rectification on Pt layers to nearly linear, graphene-like conduction on patterned electrodes. Hall measurements reveal p-type conductivity with a high carrier concentration, while comparative analyses of different Ar flow conditions show that plasma stability influences wall density and sheet thickness. Post-growth Ar/N2 exposure further modifies conductivity through controlled thinning of the graphitic walls. These interface- and morphology-dependent electrical characteristics complement electrochemical findings by highlighting how substrate selection, plasma stability, and post-treatment shape the transport pathways essential for CNW-based devices [123].

Mechanical characterization remains less explored but equally vital. Nanoindentation analysis reported a Young’s modulus value of ~28 GPa and compressive strength near 50 MPa, revealing elastoplastic deformation and confirming that CNW films, while robust, remain susceptible to delamination on smooth substrates. These results reinforce the need for graded interfaces or textured templates to enhance adhesion and durability [124].

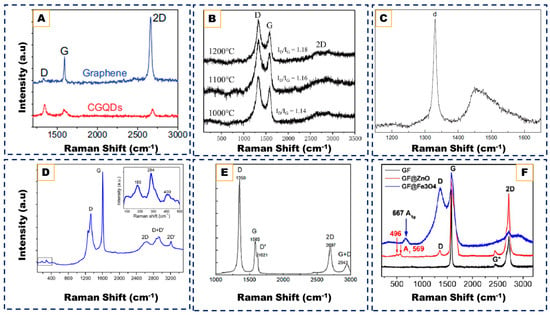

Across early and contemporary studies, a consistent narrative takes shape: [34,115,119] plasma assistance provides both the kinetic freedom and the field-induced directionality required for catalyst-free, self-organized vertical graphene growth. In practice, PECVD has become the most widely adopted route because several advantages converge. First, its broad temperature window enables vertically aligned CNWs to be synthesized at temperatures as low as ~225 °C, far below the >700 °C typically required in thermal CVD, thereby extending compatibility to polymeric and CMOS-relevant substrates [118]. Second, PECVD platforms decouple radical generation from ion-driven etching, allowing systematic adjustment of crystallinity, defect density, and wall spacing through control of plasma density and ion energy [120]. Third, large-area uniformity has been demonstrated, with freestanding CNW films retaining vertical alignment over centimeter-scale regions [115]. Building on this foundation, dual-source configurations such as RI-PECVD further refine growth control by separating radical production from ion acceleration, enabling low-damage growth while maintaining vertical order [120]. Collectively, these developments show that PECVD effectively integrates controlled energy delivery, field-directed sheet orientation, and a tunable balance between deposition and etching, establishing it as the central methodology for CNW synthesis.