Abstract

Gold-assisted exfoliation is an effective approach to obtain clean and large-area monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides, yet the microscopic evolution of interfacial adhesion remains poorly understood. Here, we investigate temperature-controlled exfoliation of MoS2 between 30 and 170 °C. Based on optical microscopy image analysis, mild heating slightly improves the exfoliation yield, which is associated with the release of interfacial contaminants and trapped gases—these substances enhance the adhesion between gold and molybdenum disulfide (Au-MoS2). Unexpectedly, as revealed by AFM, SEM-EDS, and Raman analyses, parts of the Au film start to peel off from the underlying Ti adhesion layer at approximately 100 °C. This Au film detachment, resulting from the surprisingly weak Au-Ti adhesion, serves as a unique probe for interfacial strength: it preferentially occurs at the boundaries of MoS2 flakes, indicating that the reinforcement of the Au-MoS2 interaction originates at the edges rather than being uniformly distributed. At higher temperatures (>130 °C), Au detachment expands to larger areas, indicating that boundary-localized adhesion progressively extends across the entire interface. Additional STM/STS measurements further confirm that thermal annealing improves local Au-MoS2 contact by removing interfacial species and enabling surface reconstruction. These findings establish a microscopic picture of temperature-assisted exfoliation, highlighting the dual roles of interfacial contaminant release and boundary effects, and offering guidance for more reproducible fabrication of high-quality 2D monolayers.

1. Introduction

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs), such as MoS2, are layered van der Waals (vdW) semiconductors with remarkable electronic and optical properties, making them promising candidates for next-generation electronic and optoelectronic devices [1,2,3,4]. A key requirement for both fundamental studies and practical applications is the reliable fabrication of large-area, high-quality monolayers. Various approaches have been developed, among which the most widely used is mechanical exfoliation of bulk crystals onto substrates [5,6,7]. Contamination and trapped molecules at buried interfaces are known to strongly affect the exfoliation and transfer of two-dimensional (2D) materials. A common strategy to improve exfoliation yield and quality is moderate heating, which assists the release of interfacial residues and enhances vdW adhesion between contacting layers [8,9,10,11,12].

Gold-assisted exfoliation provides a particularly clean and efficient route for preparing monolayer TMDCs, with near-unity yields reported in many systems [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Its mechanism relies on the formation of strong Au–TMDCs interactions at the interface, while simultaneously weakening the interlayer interaction between the first and second MoS2 layers [22,23]. Previous studies have suggested that strong Au–MoS2 bonding sites are sparse and randomly distributed across the interface [24]. In practice, successful exfoliation of monolayers depends on a delicate balance of adhesion energies among multiple competing interfaces. This method has been demonstrated in a broad range of metal–2D material systems, establishing a robust route toward cost-effective and uniform wafer-scale monolayer production [25,26,27,28]. Beyond large-area exfoliation, metal-assisted methods have also been explored for fabricating functional structures, such as stacking layers [29,30], twisted heterostructures [31], patterns [26,32] and device arrays [32]. However, it is still challenging to fabricating TMDC patterns high accuracy, typically to the micrometer scale, since smaller Au contact regions generally fail to sustain stable exfoliation of TMDCs [32,33,34,35,36]. A clearer microscopic picture of where strong Au–MoS2 connections first form, and how they evolve under processing conditions, would therefore not only deepen our understanding of the exfoliation mechanism, but also provide useful guidance for realizing complex patterned 2D structures using metal-assisted exfoliation.

In this work, we investigate Au-assisted exfoliation of MoS2 under controlled substrate temperatures ranging from 30 to 170 °C. Because the interface in this exfoliation system is confined between two solid layers and undergoes continuous transformation during heating, conventional high-resolution probes cannot directly resolve its structure or chemistry. Thus, the interfacial interactions are best inferred from the exfoliated product morphology and adhesion contrast, for which optical microscopy provides the most comprehensive and scalable characterization. Mild heating promotes the release of interfacial contaminants, thereby strengthening the Au–MoS2 interaction and slightly improving the exfoliation yield. Unexpectedly, the Au film itself can detach from the underlying Ti adhesion layer due to weak Au–Ti bonding. Although this detachment is not intrinsic to MoS2 exfoliation, it provides a unique probe for mapping the spatial distribution of the Au–MoS2 adhesion. By tracking this effect, we identify that reinforcement of the strong vdW Au–MoS2 interaction originates at the flake boundaries and progressively extends across the entire interface with increasing temperature. This finding establishes a new perspective on the formation of strong vdW metal–2D semiconductor contacts and underscores the critical role of domain boundaries in determining exfoliation pathways.

2. Materials and Methods

10 × 10 mm2 Si substrates with a ~300 nm SiO2 layer were used as the substrates. A ~2 nm Ti adhesive layer and an ~18 nm Au film were sequentially deposited by magnetron sputtering. Bulk MoS2 crystals (Taizhou SUNANO New Energy, Shanghai, China) were mechanically exfoliated using Kapton polyimide tape, which offers thermal stability up to ~300 °C. To provide comparable mechanical support to conventional blue tape, five layers of Kapton tape were stacked during exfoliation. The tape was gently covered onto the Au-coated substrate after the Au film was exposed to air for ~1 min, minimizing pressure effects to avoid damaging the material. The samples were heated on a hot plate at the designated substrate temperature for 10 min before tape removal. The temperature was monitored in real time using a TES-1310 digital thermometer (TES, Taipei, Taiwan, China) with a K-type thermocouple placed in direct contact with the sample to ensure accurate readings of the actual sample temperature. For post-exfoliation thermal treatments, selected MoS2/Au/Ti/SiO2/Si samples were annealed in a quartz-tube furnace under Ar flow (30 sccm, 20 min).

Optical microscopy (Zeiss LSM700 and AxioScope AI, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to characterize exfoliated MoS2 domains. The coverage of various surface structures in optical microscope images was determined from three representative 1 × 1 mm2 regions with the highest MoS2 coverage on each sample, using Fiji/ImageJ (version 1.54f) for area selection. Raman spectra were collected with a RENISHAW inVia system (London, UK) using a 532 nm laser at 0.6 mW. AFM images were acquired with a Bruker Dimension Fastscan (Billerica, MA, USA) in peak force tapping mode under ambient conditions.

Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) measurements are carried out using a variable temperature STM (Omicron, Taunusstein, Germany) operating in ultra-high vacuum (base pressure better than 1 × 10−9 mbar) at room temperature. Point dI/dV spectra are obtained by differentiating the smoothed I(V) curves.

3. Results and Discussion

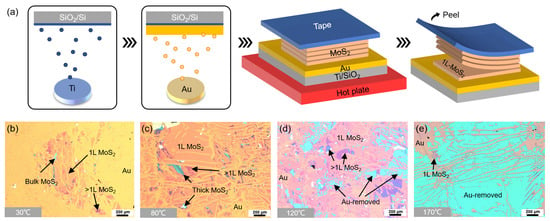

As illustrated in Figure 1a, to examine the role of substrate temperature in Au-assisted exfoliation, we first deposited a Ti adhesion layer (~2 nm) on Si/SiO2 substrates by magnetron sputtering, followed by Au thin films (~18 nm). Due to the limitations of our deposition system, the samples had to be exposed to air for less than 1 min after Ti deposition before being reloaded into vacuum for Au deposition. This unavoidable air exposure at the Ti–Au interface is later found to be closely related to the Au-removal phenomena discussed below.

Figure 1.

Au-assisted exfoliation of MoS2 monolayers at different substrate temperatures. (a) Schematic illustration of the exfoliation procedure. (b–e) Optical microscope images of exfoliated samples prepared at 30 °C, 80 °C, 120 °C, and 170 °C, respectively. Regions of exposed Au, monolayer MoS2, multilayer MoS2, bulk residues, and Au-removed areas are labeled.

After preparing the Au films, bulk MoS2 crystals attached to adhesive tape were gently placed onto the Au surface without pressing, in order to minimize possible pressure effects. The samples were then heated on a hot plate at the target temperature for 10 min. Upon peeling off the tape, part of the top MoS2 monolayer remained on the Au due to the strong vdW interaction between MoS2 and Au. Optical microscope images (Figure 1b–e) reveal the overall temperature dependence of the exfoliation results. At 30 °C (Figure 1b), only ~30% of the Au surface was covered by monolayer MoS2, indicating insufficient interfacial adhesion. At 80 °C (Figure 1c), the exfoliation yield increased dramatically, with most of the surface covered by monolayer MoS2, although multilayer flakes and bulk residues were still present. At 120 °C (Figure 1d), in addition to the MoS2 regions, uniformly blue-colored areas appeared, which differed from the optical contrast of monolayers or multilayers and were identified as Au-removed regions. At 170 °C (Figure 1e), exfoliation of MoS2 was almost completely suppressed, and more than 60% of the surface consisted of Au-removed regions.

To quantify the temperature dependence of exfoliation, we carried out systematic experiments from 30 to 170 °C at ~10 °C intervals. The core rationale for selecting 170 °C as the upper limit is that the adhesive tape undergoes denaturation at temperatures above this threshold. Additional optical images are summarized in Figure S1. Following the statistical method in our previous paper (Ref. [23]), three parameters were defined: the total exfoliation yield of MoS2 [], the area fraction of monolayer regions within all MoS2 covered regions [], and the area fraction of Au-removed regions [], where Sfov is the area of each selected optical microscope image, Sall is the total area covered by MoS2, S1L is the area covered by monolayer MoS2, and SAu_r is the area of Au-removed regions. The results reported here are based on three representative 1 mm × 1 mm images with the highest MoS2 coverage on each sample (see Ref. [24]).

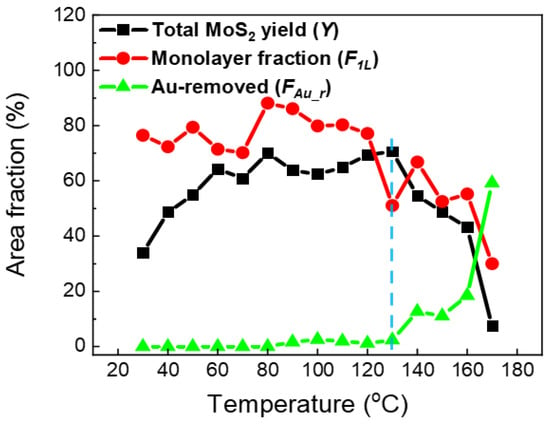

As shown in Figure 2, the total yield Y increased from ~30% at 30 °C to ~70% at 80 °C, and remained nearly constant (~70%) up to 130 °C. The Au–MoS2 interface involves chemically inert surfaces, and the strengthening of their interaction upon heating arises primarily from physical effects. The gradual increase in yield between 30 and 80 °C can be attributed to the release of interfacial contaminants and trapped gas molecules, which enhances the effective Au–MoS2 adhesion and facilitates more efficient exfoliation. This temperature range is consistent with previous reports on the effective release of interfacial gas bubbles near 110 °C [12]. Above 130 °C, however, Y dropped sharply, reaching ~5% at 170 °C. In contrast,

was negligible below 80 °C, slightly increased to ~3% between 90 and 130 °C, and then rose steeply above 130 °C, reaching ~60% at 170 °C. The monolayer fraction F1L was consistently high (~80%) below 130 °C, but decreased significantly at higher temperatures, dropping to ~30% at 170 °C. These results clearly indicate that 130 °C represents a threshold temperature: above this point, MoS2 exfoliation is strongly suppressed, and large Au-removed regions begin to dominate.

Figure 2.

Temperature dependence of exfoliation yield and area fractions. Statistical analysis of optical images gives the total MoS2 yield (Y), the monolayer fraction (F1L), and the fraction of Au-removed regions (FAu_r). The dashed vertical line at T = 130 °C marks the onset of Au removal and the simultaneous drop in MoS2 yield.

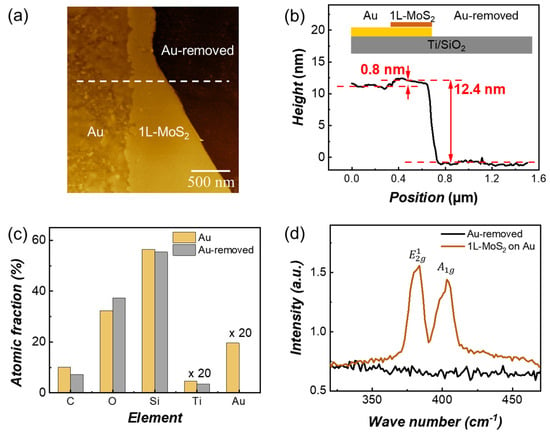

To further clarify the composition and characteristics of the Au-removed regions, we performed complementary analyses. Figure 3a shows an AFM image containing three distinct regions: bare Au, 1L-MoS2, and an Au-removed area. The corresponding line profile extracted along the dashed line in Figure 3a is presented in Figure 3b. The step height between the bare Au and the 1L-MoS2 region is ~0.8 nm, consistent with the expected thickness of a monolayer. In contrast, the Au-removed region exhibits a much larger height drop of ~12.4 nm relative to the 1L-MoS2, indicating the absence of the Au film in this region.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the Au-removed regions. (a) AFM image showing the boundary between a bare Au area, a 1L-MoS2-covered area, and an Au-removed area. (b) AFM line profile extracted along the dashed line in (a). (c) Atomic fractions of Au-covered and Au-removed regions obtained from SEM-EDS analysis (×20 indicates a 20-fold magnification of the atomic fraction in the corresponding plot). (d) Raman spectra of 1L-MoS2 and Au-removed regions.

Elemental analysis by SEM-EDS (Figure 3c, the corresponding SEM image is shown in Figure S2) further confirms this observation. In the Au-covered region, the atomic fraction of Au is ~1%, whereas in the Au-removed region it is nearly zero. The other elements (C, O, Si, and Ti) show only minor variations between the two regions, suggesting that the primary difference arises from the loss of the Au film. Raman spectroscopy (Figure 3d) provides additional evidence. In the 1L-MoS2 region, the characteristic

(~383 cm−1) and

(~403 cm−1) vibrational modes of MoS2 are clearly observed. By contrast, these peaks are absent in the Au-removed region, indicating that no MoS2 monolayer remains there. Together, these results confirm that the Au-removed regions correspond to areas where the Au film has detached along with the MoS2 attached to the tape.

The removal of the Au layer from the Ti adhesion layer is unexpected, as the Ti–Au interface is expected to be stabilized by ionic or metallic bonding, which should be much stronger than any vdW-type interfaces. Room-temperature control tests further show that Kapton tape alone cannot peel off Au films without MoS2 flakes, indicating decently strong Au/Ti adhesion without heating. The weakening of this boundary is likely related to air exposure of the Ti surface prior to Au deposition, which may lead to oxidation or contamination of the Ti layer. To verify this, we deliberately extended the air exposure of the Ti surface to 10 min before Au deposition. The resulting samples exhibited a much less stable Au/Ti interface, where Au could be removed even during room-temperature exfoliation, as shown in Figure S3. This result confirms that the adhesion of the Au/Ti interface is highly sensitive to surface contamination and can act as the weak link in exfoliation under certain conditions. The weak adhesion of the Au film is consistent with previous reports showing that Au films can be detached by adhesive tapes due to weak Au–oxide bonding [37,38].

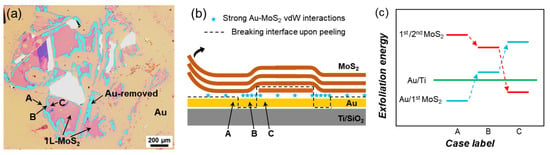

Since the Au/Ti interface lies beneath the Au/MoS2 interface, its adhesion is expected to be relatively uniform across the substrate. However, the spatial distribution of Au-removed regions is not random. As seen in Figure 1d,e, the morphology of the Au-removed patches appears very similar to the geometry of 1L-MoS2 domains. This correlation is most clearly observed when Au removal first appears. As shown in Figure 4a, narrow Au-removed regions surround isolated MoS2 flakes, implying that Au detachment preferentially initiates along MoS2 domain boundaries. This observation rules out the possibility that Au/Ti rupture dictates MoS2 coverage. Instead, it indicates that the pre-existing structural boundaries of MoS2 act as templates that guide where Au removal nucleates at around 100 °C. It should be noted that, because the Kapton tape had been repeatedly used to cleave bulk MoS2, its surface became more than 90% covered by MoS2 flakes, making direct tape–Au contact marginal during exfoliation. The remaining exposed regions cannot account for the Au film removal, as the Au-detached areas follow the geometry of the exfoliated MoS2 flakes (Figure 4a). Even if direct tape–Au adhesion had increased at elevated temperatures, it would not affect our interpretation, as the observed Au detachment is spatially locked to the MoS2 edge-exfoliation boundaries rather than to the tape–Au contact area.

Figure 4.

Formation mechanism of Au-removed regions. (a) Optical micrograph of a sample prepared at 120 °C, where Au removal first emerges. Narrow Au-removed regions are seen surrounding 1L-MoS2 domains, indicating their correlation with MoS2 boundaries. (b) Schematic illustration of the local interfacial configuration, showing three adjacent regions: A, B, and C, corresponding to bare Au, Au-removed, and 1L-MoS2-covered regions, respectively. The higher density of star symbols near region B indicates the locally enhanced strong vdW interactions between Au and MoS2 near the flake boundaries. (c) Schematic comparison of exfoliation energies for different interfaces in the three regions, taking the Au/Ti interface as reference.

To explain this behavior, we propose a schematic model, as shown in Figure 4b. The bonding forces between metals as well as between metals and semiconductors have been thoroughly studied [39,40,41]. A finite MoS2 flake embedded between the Au film and upper MoS2 layers introduces geometric boundaries. At these boundaries, the Au–MoS2 interaction becomes locally enhanced, illustrated by the higher density of star markers. This configuration produces three adjacent interfacial regions: labelled as A, B, and C as seen in the image. The corresponding exfoliation energies are compared in Figure 4c. In region A, exfoliation occurs at the Au-MoS2 interface. Although strong vdW interactions may randomly form at the Au–MoS2 interface, exfoliating the first MoS2 layer requires generating a tear boundary in its covalent network (i.e., breaking local covalent bonds at the edge, as shown in Ref. [42]), which leads to a relatively high exfoliation energy at the 1st/2nd MoS2 interface. In region C, exfoliation takes place at the 1st/2nd MoS2 interface, where only the weaker interlayer vdW force is to overcome, making it energetically favorable. In region B, the locally enhanced Au–MoS2 interaction increases the Au/1L-MoS2 interfacial energy above that of the Au/Ti interface (while simultaneously decreasing the 1st/2nd MoS2 binding energy slightly, see Ref. [22]). Thermal expansion mismatch between oxidized Ti and Au may also contribute to the reduced adhesion and subsequent detachment of the Au layer [43,44]. As a result, exfoliation preferentially occurs at the Au/Ti interface, leading to Au detachment.

The origin of the enhanced Au–MoS2 adhesion at flake boundaries may involve multiple effects. One possibility is the faster release of trapped interfacial gas molecules, possibly facilitated by diffusion pathways at these MoS2 flake boundaries, therefore improving the interfacial contact. Another is enhanced Au diffusion along MoS2 boundaries, consistent with earlier reports, see Ref. [42], which increases the effective contact area and strengthens adhesion. These possibilities are in line with previous atomistic ab initio studies showing that interfacial bonding energies in metal–semiconductor and vdW heterostructures are highly sensitive to the local chemical environment and contact configuration [39,40,41].

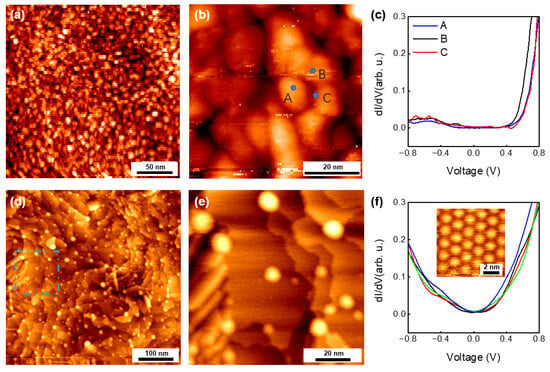

To further probe the evolution of the buried MoS2/Au interface, we performed STM and STS measurements on samples before and after thermal annealing, as shown in Figure 5. The as-prepared interface exhibits a highly corrugated and amorphous-like morphology (Figure 5a,b). The dI/dV spectra collected from these regions display semiconducting behavior (Figure 5c), indicating weak electronic hybridization and limited formation Au–MoS2 contact sites. This weak contact suggests the presence of trapped gases and contaminants between MoS2 and Au.

Figure 5.

STM characterization of the MoS2/Au interface before and after annealing. (a) STM overview image of the as prepared MoS2/Au interface (VS = −2 V, It = 0.05 nA). (b) Enlarged STM image in a region in (a) (VS = −1 V, It = 0.1 nA). (c) dI/dV spectra collected at three sites marked in (b). (d) STM overview image of the 350 °C annealed MoS2/Au interface (VS = −2 V, It = 0.05 nA). (e) Enlarged STM image in regions marked in darshed blue box in (d) (VS = −1 V, It = 0.1 nA). (f) dI/dV spectra collected at four sites in flat terraces. The inset STM image shows the moiré superlattices formed due to the lattice mismatch between MoS2 and Au(111) on flat terrace regions.

After annealing at 350 °C, the interface undergoes a pronounced reconstruction. Large, atomically flat terraces emerge as gold atoms reorganize following the release of interfacial contaminants (Figure 5d,e). Within these terraces, well-defined moiré superlattices characteristic of the MoS2/Au(111) heterointerface become visible, demonstrating significantly improved contact quality. Correspondingly, the STS spectra acquired on these terraces exhibit metallic features (Figure 5f), consistent with previous reports attributing such metallic behavior to strong interfacial hybridization between MoS2 and Au [42]. This enhanced hybridization only occurs when MoS2 is brought into intimate contact with a re-constructed Au surface.

These STM/STS results demonstrate that thermal annealing plays a crucial role in improving the microscopic contact of the MoS2/Au interface. Heating removes trapped interfacial species and allows surface Au atoms to reconstruct into flat terraces, which in turn enables MoS2 to form much more intimate contact with the Au(111) surface. Although STM does not directly resolve the buried interface, these observations suggest that regions where contaminants are removed more rapidly can more readily develop stronger local adhesion sites. Considering that molecular or atomic diffusion is expected to be faster near the porous edge structure of MoS2, it is reasonable to infer that such processes may initiate more efficiently at the flake boundaries, consistent with the boundary-related behavior observed in our morphology-based analysis.

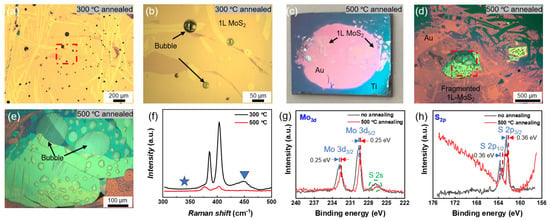

At higher temperatures (e.g., 170 °C), Au removal extends across the entire surface. This behavior may result from further releasing of interfacial contaminations, or from Au diffusion into MoS2 interlayers, which increases the binding energy between the first and second MoS2 layers. The possible reduction in Au/Ti adhesion energy due to interfacial reactions (such as trapped gas expansion or Ti oxidation) might also play a role. To further probe these possibilities, we tested the thermal stability of exfoliated samples at elevated temperatures. As shown in Figure 6a,b, annealing the sample at 300 °C produces localized Au bubbles uncorrelated with MoS2 boundaries, consistent with trapped gas effects at the Au/Ti interface. At 500 °C, as shown in Figure 6c–e, large-scale Au diffusion occurs, with Au migrating laterally away from the wafer edge and MoS2 domains becoming fragmented. No Raman signatures of phase or chemical-state modification are observed at 300 °C (Figure 6f), the temperature range relevant to the present exfoliation study. Raman spectra further reveal severe degradation of 1L-MoS2 after 500 °C annealing.

Figure 6.

Effects of high-temperature annealing on 1L-MoS2/Au samples. Samples were annealed in a tube furnace under 30 sccm Ar flow for 20 min. (a) Optical micrograph after annealing at 300 °C. (b) Magnified view of the boxed region in (a), showing several Au film bubbles unrelated to MoS2 boundaries. (c) Optical image of a 1 cm2 Si wafer slice after annealing at 500 °C, showing disappearance of Au near the wafer edge and blue contrast from exposed Ti due to lateral Au diffusion. (d) Optical micrograph of a region where the Au film remains after 500 °C annealing. Some 1L-MoS2 domains are still recognizable though fragmented. (e) Magnified view of the boxed region in (d), showing a thick MoS2 region that remains intact except for several trapped bubbles between MoS2 and Au. (f) Raman spectra of 1L-MoS2 regions after annealing at different temperatures, showing clear degradation of MoS2 after 500 °C treatment (The pentagrams and triangles at ~335 cm−1 and ~454 cm−1 indicate the characteristic peaks (see text)). XPS spectra of samples without annealing and after 500 °C annealing: (g) Mo 3d; (h) S 2p.

Such extreme high-temperature annealing (500 °C) induces detectable changes in the local chemical state of MoS2. Figure 6g displays the XPS spectra of the Mo 3d and S 2s orbitals in MoS2 before and after annealing. For the unannealed sample (black curve), the Mo 3d orbital splits into characteristic peaks of 3d5/2 (~229.6 eV) and 3d3/2 (~232.8 eV). After 500 °C annealing (red curve), both characteristic peaks of Mo 3d shift 0.25 eV toward lower binding energies. Additionally, the peak appearing on the low binding energy side of the Mo 3p band (~226.9 eV) corresponds to the S 2s orbital signal, a typical XPS feature of S 2s in MoS2. Figure 6h presents the S 2p orbital in MoS2 before and after annealing. After 500 °C annealing, both characteristic peaks of S 2p shift 0.36 eV toward lower binding energies, consistent with the shift trend of the Mo 3d peaks in Figure 6g. Together, these results suggest that both interfacial gas and Au diffusion might play important roles in the formation and evolution of Au-removed regions. In addition, although high temperature treatment had been shown to create coexisting 1T phase for MoS2 [45,46], our Raman data does not indicate a clear signature (no peak at 335 cm−1, as shown in Figure 3d and Figure 6) [47].

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have systematically examined temperature-controlled Au-assisted exfoliation of MoS2 in the range of 30–170 °C. At low temperatures (30–80 °C), the exfoliation yield increases modestly, which we attribute to the gradual release of interfacial contaminants and trapped gas molecules that enhances the effective Au–MoS2 adhesion. At intermediate temperatures (~80–120 °C), Au-removed regions emerge and nucleate preferentially along the edges of MoS2 flakes. Although this Au removal originates from rupture at the buried Au/Ti interface, it serves as a unique probe for locating where interfacial adhesion is strongest, revealing that the strengthening of the Au–MoS2 interaction initiates at domain boundaries. At higher temperatures (>130 °C), widespread Au removal dominates, indicating that the boundary-localized adhesion enhancement progressively extends across the entire interface, likely due to further expulsion of interfacial gases and enhanced Au diffusion. Complementary STM/STS measurements further confirm that thermal annealing promotes the removal of interfacial species and the reconstruction of surface Au into flat terraces, thereby enabling more intimate and electronically coupled Au–MoS2 contact. Taken together, these results clarify the microscopic processes underlying temperature-assisted exfoliation and highlight the critical role of domain boundaries in governing interfacial interactions, offering new insights for designing more reliable strategies to fabricate large-area 2D semiconductor monolayers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nano15231835/s1, Figure S1: Additional optical microscope images of samples prepared via temperature-controlled Au-assisted exfoliation. Figure S2: SEM images of a sample surface region with neighboring bare Au area and the Au-removed area. Figure S3: Optical microscopy image of a sample prepared at 30 °C using a Au film deposited after prolonged air exposure of the Ti surface.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.; methodology, C.D. and S.C.; investigation, B.W., B.L.; data curation, C.D., and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D., S.C. and F.M.; writing—review and editing, L.S., F.M. and S.D.; visualization, C.D. and S.C.; supervision, F.M.; project administration, F.M. and S.D.; funding acquisition, F.M. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2020B1515020009), National Science Foundation of China (No. 12474183 and 12174456), Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (2024A04J6304).

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Q.H.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kis, A.; Coleman, J.N.; Strano, M.S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotech. 2012, 7, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, G.H.; Lee, C.H. Two-dimensional semiconductor optoelectronics based on van der Waals heterostructures. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, B. Monolayer MoS2 for nanoscale photonics. Nanophotonics 2020, 9, 1557–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Kim, S.; Han, S.A.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.H. Synthesis strategies and nanoarchitectonics for high-performance transition metal dichalcogenide Thin Film Field-effect Transistors. ChemNanoMat 2023, 9, e202300104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Meng, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, T.Z.; Bao, L.H.; Liu, G.D.; Zhao, L.; Liu, T.S.; Xing, J.; Gao, H.J.; et al. Applications of new exfoliation technique in study of two-dimensional materials. Acta Phys. Sin. 2018, 67, 218201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. Mechanical exfoliation of large area 2D materials from vdW crystals. Prog. Surf. Sci. 2021, 96, 10062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dong, J.; Ding, F. Strategies, status, and challenges in wafer scale single crystalline two-dimensional materials synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 6321–6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, H.; Xu, N.; Deng, S. Controlled preparation of high quality bubble-free and uniform conducting interfaces of vertical van der Waals heterostructures of Arrays. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 10877–10885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, N.; Yoon, S.; Holbrook, M.; Thinel, M.; Holtzman, L.N.; Liu, Y.; Hsieh, V.; Li, Y.; Xu, D.D.; Rojas-Gatjens, E.; et al. Macroscopic transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers from gold-tape exfoliation retain intrinsic properties. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 15198–15205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lough, S.; Thompson, J.E.; Smalley, D.; Rao, R.; Ishigami, M. Impact of thermal annealing on the interaction between monolayer MoS2 and Au. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2301944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyl, M.; Burmeister, D.; Schultz, T.; Pallasch, S.; Ligorio, G.; Koch, N.; List-Kratochvil, E.J. Thermally activated gold-mediated transition metal dichalcogenide exfoliation and a unique gold-mediated transfer. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2020, 14, 2000408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, D.A.; Dai, Z.; Lu, N. 2D material bubbles: Fabrication, characterization, and applications. Trends Chem. 2021, 3, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, N.; Peci, E.; Curreli, N.; Spotorno, E.; Tofighi, N.K.; Magnozzi, M.; Scotognella, F.; Bisio, F.; Kriegel, I. Optimizing gold-assisted exfoliation of layered transition metal dichalcogenides with (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES): A promising approach for large-area monolayers. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2303228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juo, J.Y.; Kern, K.; Jung, S.J. Investigation of interface interactions between monolayer MoS2 and metals: Implications on strain and surface roughness. Langmuir 2024, 40, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Liu, J.; Yu, Y.; Song, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Shen, W. Sapphire substrate enabled ultraflat gold tape for reliable mechanical exfoliation of monolayer MoS2. Opt. Mater. 2024, 157, 116341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollmann, E.; Sleziona, S.; Foller, T.; Hagemann, U.; Gorynski, C.; Petri, O.; Madauß, L.; Breuer, L.; Schleberger, M. Large-area, two-dimensional MoS2 exfoliated on gold: Direct experimental access to the metal–semiconductor interface. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 15929–15939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanusova, M.; Pirker, L.; Vondracek, M.; Vales, V.; Cheung, C.K.; Cordero, N.N.; Carl, A.; Zolyomi, V.; Koltai, J.; Sotiriou, I.; et al. Hybridization directionality governs the interaction strength between MoS2 and metals. Nano Lett. 2025, 15, 12995–13002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magda, G.Z.; Pető, J.; Dobrik, G.; Hwang, C.; Biró, L.P.; Tapasztó, L. Exfoliation of large-area transition metal chalcogenide single layers. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubišić-Čabo, A.; Michiardi, M.; Sanders, C.E.; Bianchi, M.; Curcio, D.; Phuyal, D.; Berntsen, M.H.; Guo, Q.; Dendzik, M. In situ exfoliation method of large-area 2D materials. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2301243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velický, M.; Donnelly, G.E.; Hendren, W.R.; DeBenedetti, W.J.I.; Hines, M.A.; Novoselov, K.S.; Abruña, H.D.; Huang, F.; Frank, O. The intricate love affairs between MoS2 and metallic substrates. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 2001324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Á.; Çakıroğlu, O.; Li, H.; Carrascoso, F.; Mompean, F.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.; Munuera, C.; Castellanos-Gomez, A. Improved strain transfer efficiency in large-area two-dimensional MoS2 obtained by gold-assisted exfoliation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 6355–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Pan, Y.-H.; Yang, R.; Bao, L.-H.; Meng, L.; Luo, H.-L.; Cai, Y.-Q.; Liu, G.-D.; Zhao, W.-J.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Universal mechanical exfoliation of large-area 2D crystals. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyl, M.; List-Kratochvil, E.J. Only gold can pull this off: Mechanical exfoliations of transition metal dichalcogenides beyond scotch tape. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, B.; Dai, C.; Zhu, L.; Shen, Y.; Liu, F.; Deng, S.; Ming, F. Controlling Gold-Assisted Exfoliation of Large-Area MoS2 Monolayers with External Pressure. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Bae, S.H.; Kong, W.; Lee, D.; Qiao, K.; Nezich, D.; Park, Y.J.; Zhao, R.K.; Sundaram, S.; Li, X.; et al. Controlled crack propagation for atomic precision handling of wafer-scale two-dimensional materials. Science 2018, 362, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Jin, Y.; Jiang, H.; Kin, S.Y.; Zhu, C.; et al. Residue-free wafer-scale direct imprinting of two-dimensional materials. Nat. Electron. 2025, 8, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Liu, Y.; Lu, K.; Chang, C.S.; Sung, D.; Akl, M.; Qiao, K.; Kim, K.S.; Park, B.-I.; Zhu, M.; et al. High-throughput manufacturing of epitaxial membranes from a single wafer by 2D materials-based layer transfer process. Nat. Nanotech. 2023, 18, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, S.; Li, T.; Du, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Huang, L.; Yu, H.; et al. Se-mediated dry transfer of wafer-scale 2D semiconductors for advanced electronics. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wu, W.; Bai, Y.; Chae, S.H.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Hone, J.; Zhu, X.-Y. Disassembling 2D van der Waals crystals into macroscopic monolayers and reassembling into artificial lattices. Science 2020, 367, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Dai, J.-Q.; Huang, X.-Y.; Dai, Y.-Y.; Pan, Y.-H.; Yang, L.-L.; Sun, Z.-Y.; Miao, T.-M.; Zhou, M.-F.; Zhao, L.; et al. One-step exfoliation method for plasmonic activation of large-area 2D crystals. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2204247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, M.; Liu, L.; Sun, Z.; Hu, G.; Song, Y.; Han, X.; Guo, J.; Wu, K.; et al. Gold-template-assisted mechanical exfoliation of large-area 2D layers enables efficient and precise construction of moiré superlattices. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2313511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ren, L.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Li, Q.; Lu, Z.; Ding, S.; Deng, H.; Chen, P.; Lin, J.; et al. Dry exfoliation of large-area 2D monolayer and heterostructure arrays. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 13839–13846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Lu, Z.; Tao, Q.; Lu, D.; Chen, Y.; Tong, W.; Liu, L.; Li, W.; et al. Ag-assisted dry exfoliation of large-scale and continuous 2D monolayers. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Luo, S.; Li, T.; Zhai, E.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Han, Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Zhao, Y.; Kono, J.; et al. Manufacturing chip-scale 2D Monolayer single crystals through wafer-bonder-assisted transfer. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 14395–14403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cai, Z.; Xue, S.; Huang, H.; Chen, S.; Gou, S.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Yao, Y.; Bao, W.; et al. A mass transfer technology for high-density two-dimensional device integration. Nat. Electron. 2025, 8, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P.V.; Mai, T.H.; Dash, S.P.; Biju, V.; Chueh, Y.L.; Jariwala, D.; Tung, V. Transfer of 2D films: From imperfection to perfection. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 14841–14876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.M.; Murray, C.P.; Ní Lochlainn, S.; Bello, F.; Zhong, C.; Smith, C.; McCarthy, E.K.; Downing, C.; Daly, D.; Petford-Long, A.K.; et al. Comparison of metal adhesion layers for Au films in thermoplasmonic applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 13503–13509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, M.; Bastos da Silva Fanta, A.; Jensen, F.; Birkedal Wagner, J.; Han, A. Influence of Ti and Cr adhesion layers on ultrathin Au films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 37374–37385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pela, R.R.; Hsiao, C.-L.; Hultman, L.; Birch, J.; Gueorguiev, G.K. Electronic and optical properties of core–shell InAlN nanorods: A comparative study via LDA, LDA-1/2, mBJ, HSE06, G0W0 and BSE methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Mei, Z.; Liang, H.; Ye, D.; Gu, C.; Du, X.; Lu, Y. Annealing Effects of Ti/Au Contact on n-MgZnO/p-Si Ultraviolet-B Photodetectors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2013, 60, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-A.; Park, J.; Wallace, R.M.; Cho, K.; Hong, S. Reduction of Fermi level pinning at Au–MoS2 interfaces by atomic passivation on Au surface. 2D Mater. 2017, 4, 015019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Huang, W.; Dai, C.; Wen, B.; Shen, Y.; Liu, F.; Xu, N.; Ming, F.; Deng, S. Fabricating model heterostructures of large-area monolayer or bilayer MoS2 on an Au(111) surface under ultra-high vacuum. Results Phys. 2024, 67, 108042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, T.E.; Kruckenberg, P.; Gorgen, C.; Lukashev, P.V.; Stollenwerk, A.J. Criteria for electronic growth of Au on layered semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 245301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobos, L.; Pécz, B.; Tóth, L.; Horváth, Z.s.J.; Horváth, Z.E.; Beaumont, B.; Bougrioua, Z. Structural and electrical properties of Au and Ti/Au contacts to n-type GaN. Vacuum 2008, 82, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, Z.; Hawthorne, N.; Chandross, M.; Moore, Q.; Argbay, N.; Curry, J.F.; Batteas, J.D. Formation of coherent 1H−1T heterostructures in single-layer MoS2 on Au (111). ACS Nano 2024, 18, 16939–16950. [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi, E.; Madonia, A.; Laurella, G.; Panasci, S.E.; Schilirò, E.; Giannazzo, F.; Piš, I.; Bondino, F.; Radnóczi, G.Z.; Kovács-Kis, V.; et al. Mild temperature thermal treatments of gold-exfoliated monolayer MoS2. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ao, K.; Lv, P.; Wei, Q. MoS2 coexisting in 1T and 2H phases synthesized by common hydrothermal method for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).