Abstract

Zirconia restorations are widely used in dentistry due to their high esthetic expectations and physical durability. However, zirconia’s opaque white color can compromise esthetics. Therefore, zirconia is often veneered with porcelain, but fractures may occur in the veneer layer. Monolithic zirconia restorations, which do not require porcelain veneering and offer higher translucency, have been developed to address this issue. Zirconia exists in three main crystal phases: monoclinic, tetragonal, and cubic. Metal oxides such as yttrium are added to stabilize the tetragonal phase at room temperature. 3Y-TZP contains 3 mol% yttrium and provides high mechanical strength but has poor optical properties. Recently, 4Y-PSZ and 5Y-PSZ ceramics, which offer better optical properties but lower mechanical strength, have been introduced. This review examines the factors affecting the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics. These factors are categorized into six main groups: cement type and color, restoration thickness, substrate color, sintering, aging, and zirconia type. Cement type and color are crucial in determining the final shade, especially in thin restorations. Increased restoration thickness reduces the influence of the substrate color while the sintering temperature and process improve optical properties. These findings emphasize the importance of material selection and application processes in ensuring esthetic harmony in zirconia restorations. This review aims to bridge gaps in the literature by providing valuable insights that guide clinicians in selecting and applying zirconia materials to meet both esthetic and functional requirements in restorative dentistry.

1. Introduction

Zirconia is favored for dental restorations due to its superior esthetics compared to metal-ceramic restorations and its excellent mechanical properties, enhanced by transformation toughening. Additionally, advancements in chairside milling and rapid-sintering technology have made the fabrication process more automated, precise, and time-efficient [1]. Although the opaque white color of zirconia, resulting from its polycrystalline microstructure, negatively impacts esthetic appearance; the level of opacity can vary among the different zirconia systems available on the market [2,3]. For this reason, zirconia is commonly used as a core material in dental restorations and is veneered with porcelain to enhance esthetics [3]. However, veneering the zirconia core with ceramic increases the overall thickness of the restoration, necessitating greater tooth reduction and potentially weakening the abutment tooth. Mechanical issues such as chipping and fracture are also common in veneering porcelain. To overcome these challenges, monolithic zirconia was introduced as an alternative. Monolithic zirconia now allows for more translucent and esthetic restorations [1].

Zirconia (ZrO2) exists in three primary crystalline phases; monoclinic at room temperature, tetragonal above 1170 °C, and cubic at 2370 °C [4]. As zirconia ceramics cool, they undergo a transformation from the cubic to the monoclinic phase, leading to a volumetric expansion of around 5%. This transformation can cause fractures and make zirconia more brittle. As a result, pure zirconia is not used in biomedical, structural, or functional applications due to challenges associated with its phase transformation and volumetric expansion [5]. Metal oxides such as magnesium, cerium, yttrium, and calcium are used to stabilize the tetragonal phase of zirconia at room temperature [5,6]. In dentistry, yttrium oxide (Y2O3) is the most commonly used oxide for stabilizing zirconia [7]. When the added Y2O3 content is above 8 mol%, the material remains in a fully stabilized cubic phase [8]. With the addition of smaller amounts (3 mol% to 5 mol%), yttria partially stabilized zirconia (Y-PSZ) is formed [5]. When a fracture occurs in the Y-TZP material, its grains absorb energy, triggering a transformation of the crystals from the tetragonal phase to the monoclinic phase. The zirconium grains undergo a 4% volume increase during the tetragonal–monoclinic phase transformation. As a result, the localized compressive stress fields prevent further fracture propagation. This process is known as transformation toughening. The transformation toughening of zirconia enhances its physical properties, which provides high flexural strength and fracture toughness, making it suitable for demanding applications [7]. Although monolithic Y-TZP ceramics have recently gained popularity due to their good biocompatibility, esthetic properties, and high strength, they still present significant drawbacks, including semi-translucency, radiopacity, and limited light transmission [9,10].

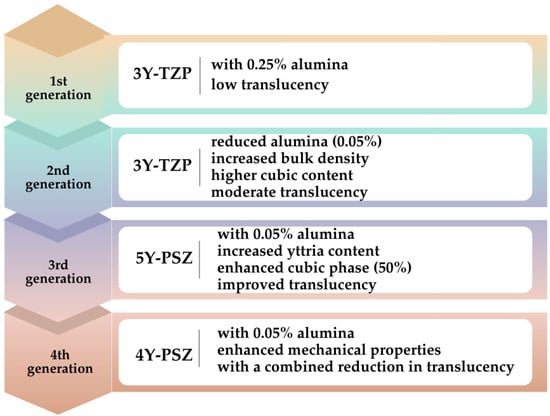

The first dental application containing 0.25–0.5 wt.% alumina is traditional zirconia, known as 3Y-TZP [8]. 3Y-TZP is partially stable in the tetragonal phase, exhibits high mechanical properties, and was introduced more than 25 years ago. Due to its biocompatibility and flexural strength exceeding 1000 MPa, 3Y-TZP is commonly used as a core material [11]. Its mechanical properties also allow it to be used in multi-unit restorations. However, its high opacity limits its optical properties, negatively impacting its esthetic appearance. In 2013, enhanced versions of 3Y-TZP materials were introduced to the market. This improvement was achieved through high-temperature sintering to minimize porosity and significantly reduce the alumina content [1]. By decreasing the alumina content to less than 0.05%, highly translucent 3Y-TZP has been developed, significantly enhancing its translucency [8]. Next, further improvements in zirconia translucency were achieved by increasing the yttria (Y2O3) content to 5 mol% (5Y-PSZ), resulting in approximately 50% cubic phase content [12]. The translucency of zirconia was further enhanced in this material, making it possible to use monolithic zirconia restorations in anterior teeth [8]. However, a higher cubic phase content adversely affects mechanical properties, including flexural strength and fracture toughness.

Considerable effort has been dedicated to optimizing the material properties through various modifications to expand the range of indications for monolithic zirconia restorations. In 2017, 4Y-PSZ was introduced to the market. Compared to 5Y-PSZ, the yttria content in 4Y-PSZ has been reduced to 4 mol%, leading to improved mechanical properties while compromising optical characteristics. According to the manufacturer, 4Y-PSZ restorations are suitable for anterior and posterior crowns, as well as short-span fixed partial dentures with multiple units [12,13]. In contrast, 5Y-PSZ restorations are primarily indicated for anterior crowns and short-span fixed partial dentures [13]. In general, increasing the yttria content enhances the material’s optical properties but compromises its mechanical strength [14]. Among yttria-stabilized zirconia materials, 3Y-TZP offers the highest mechanical strength, yet its high opacity restricts its application to non-esthetic areas in dentistry. In contrast, 5Y-PSZ offers superior optical properties, although its mechanical strength is reduced. 4Y-PSZ is considered an intermediate material, balancing optical and mechanical performance. Despite its lower strength, translucent 5Y-PSZ is a suitable option for anterior restorations, as it meets the minimum strength requirements while providing a clinically acceptable esthetic outcome [15]. Increasing the proportion of the cubic phase in the zirconia structure enhances the material’s translucency. The cubic phase ratio has progressively increased throughout the generations of zirconia. However, studies indicate that a higher cubic phase content reduces flexural strength, fracture toughness, and fatigue resistance [16]. A higher yttria content leads to an increased cubic phase and greater translucency. However, a reduction in the tetragonal phase, which contributes to flexural strength, results in decreased fracture toughness. Therefore, the translucency of 5Y-PSZ is approximately 20% to 25% higher than that of 3Y-TZP, whereas its flexural strength is from 40% to 50% lower [8]. In summary, while third-generation zirconia exhibits superior optical properties, fourth-generation zirconia provides greater durability [17]. The contents and translucency levels of the zirconia materials in the generations are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The contents and translucency levels of the generations of the zirconia ceramics.

Recently, polychromatic or color-gradient zirconia blocks have been introduced to replicate the natural color transitions of teeth [14]. Some zirconia materials integrate different generations with varying yttria content within a single block, combining high strength and enhanced translucency [12]. This typically involves high-strength zirconia in the dentin or body region and high-translucency zirconia in the incisal or occlusal areas to improve esthetics [18]. Due to these advancements, dental zirconia is classified into three types: monochromatic zirconia ceramics with uniform composition, polychromatic multilayered zirconia ceramics, and polychromatic hybrid-structured multilayered zirconia ceramics [19].

In dentistry, color is considered a measurable quantity rather than a subjective quality. Therefore, color-determining systems and color parameters are used to evaluate the optical properties of the restorations. The Munsell Color System defines the three dimensions of color as hue, value, and chroma, and the CIELab Color System defines color along three axes as L*, a*, and b*, among the most commonly used systems [20]. ΔE (delta E) is a unit used to quantify color differences between two shades. This term is mainly used in dentistry and other esthetic-related disciplines to evaluate the color compatibility of restorations with natural teeth. The calculation of ΔE is performed using a color system [20,21]. In the CIELab system, formulas such as ΔEab and ΔE00 are used to determine color differences. Although the ΔE00 formula provides results that better align with the human eye’s perception of color differences, ΔEab is more commonly used in dentistry due to its simplicity [20]. The color of the restoration is compared with an adjacent tooth or target shade to calculate the ΔE value, which is then evaluated based on the perceptibility (ΔEab = 1.2) and acceptability (ΔEab = 2.7) thresholds [22]. However, ΔE00 defines the perceptibility and acceptability threshold values as 0.8 and 1.8, respectively [22]. The dentist must select the most suitable color for the patient and transfer it correctly to the laboratory. Color selection is performed using different methods divided into visual and instrument-based color selection [23]. In visual color selection, standard color scales are used. The first systematic color scale was the “Tooth Color Indicator”, developed by Clark, which contained sixty ceramic specimens. Although many products were introduced afterward, the real breakthrough occurred with the launch of the “Vitapan Classical” (VC; Vita Zahnfabrik, Bad Sackingen, Germany) color scale in the mid-1950s. The subsequent development came in the late 1990s with the creation of the “Toothguide 3D-Master” (TG; Vita Zahnfabrik, Bad Sackingen, Germany). Finally, the “VITA Linear Guide 3D Master” (Vita Zahnfabrik; Bad Sackingen, Germany) color scale was introduced [24]. Visual color selection is inherently subjective and may vary from person to person. It can also be influenced by the observer’s gender, age, cultural background, eye fatigue, and environmental factors. However, visual color selection continues to be the predominant method in dentistry. In contrast, instrument-based color selection methods have been developed to achieve greater esthetic accuracy and reliability. These methods use spectrophotometers, colorimeters, and digital cameras [25]. An effective color-measuring tool must meet several criteria, including shock resistance, ease of operation, rapid measurement capability, durability, having a suitable light source, affordability, and most importantly, providing accurate and precise results. Digital methods minimize subjectivity, and digital photography, in particular, has transformed dentistry. It facilitates the documentation of patients’ oral conditions, comparison of treatment progress, shade selection assistance, and patient education. Digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras, equipped with adjustable lenses and various settings (aperture, ISO, and shutter speed), have become essential tools in modern dental practice. While reliable lighting and fixed distances are crucial, digital photography ensures accurate shade matching when conducted under controlled conditions [26].

Current ceramic materials are suitable for optimal esthetics; however, there is an increasing demand for more durable materials because of their brittleness. Highly translucent zirconia-based ceramics, manufactured through computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD-CAM) technology, are becoming increasingly popular due to their excellent physical, mechanical, biological, and chemical properties. However, various factors can influence the final color of zirconia restorations, including the type and color of cement, substrate color, restoration thickness, sintering, aging, and the type of zirconia material [27,28,29,30,31]. These parameters should be carefully evaluated before treatment to achieve successful esthetic outcomes in zirconia restorations. Thus, this narrative literature review aims to discuss these practical factors affecting the color change in monolithic zirconia restorations based on the literature. The methodology for developing this article is as follows: Relevant studies were identified through searches in Google Scholar, PubMed/Medline, and Web of Science databases, focusing on publications between 2008 and 2024. The search was conducted using search terms such as ‘monolithic zirconia’, ‘color’, and ‘color change’. Articles in English were included. This study focused on narrative reviews, including systematic reviews, reviews, and in vitro studies addressing factors affecting the color change in zirconia restorations. However, letters to the editor and case reports were excluded from the review. Articles from all categories of journals were included, provided they met the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2. Factors Affecting the Color Change in Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics

2.1. Effects of Cement Type and Cement Color on the Color Change in Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics

The cementation of zirconia restorations can be performed using traditional cements or adhesive cementation, either with or without additional adhesive systems. Resin cements are the most commonly used dental materials for cementing zirconia restorations because they offer good esthetics, low solubility, high strength, and mechanical resistance [32]. However, zirconia has a polycrystalline tetragonal structure. Lacking a glass phase, zirconia is unsuitable for silanization and resistant to etching with acids such as hydrofluoric or orthophosphoric acid. Therefore, alternative protocols have been developed to improve bonding strength [33]. Various mechanical and chemical surface treatments enhance the bond strength between zirconia and resin cement. Mechanical treatments include airborne particle abrasion, tribochemical silica coating, selective infiltration etching, and laser treatment [34]. Chemical surface treatments include silanization, hydrofluoric acid etching, hot etching, and the application of primers containing 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate. In addition, combining chemical and mechanical techniques is recommended for an effective result [35]. Minor alterations in the microstructure or surface roughness from internal surface finishing can affect color and transparency due to the material’s thinness and high translucency, particularly when using ultra-transparent zirconia in minimally invasive restorations [36]. Chen et al. [36] evaluated the effects of different surface treatments and thicknesses on ultra-transparent zirconia’s color, transparency, and surface roughness. One-hundred-and-twenty ultra-translucent zirconia specimens were divided into groups based on thickness (0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 mm) and surface treatments (control, airborne particle abrasion, lithium disilicate coating, and glazing). Results revealed that surface treatments and thickness significantly influenced color difference (ΔE00), translucency, and surface roughness. Airborne particle abrasion resulted in the lowest transparency, highest color difference, and excellent surface roughness. Thinner zirconia (0.3 mm) showed a strong negative correlation between surface roughness and translucency, while increasing thickness reduced the impact of surface treatments on optical properties. From a clinical perspective, the findings highlight the importance of balancing bonding enhancements from surface treatments with their effects on the optical properties of ultra-transparent zirconia and suggest that increasing restoration thickness can mitigate adverse impacts on esthetics.

Furthermore, the cement type and color affect the restoration’s final color [37,38]. The effects of cement on the optical properties of restorations have become even more critical, especially with the advances in highly translucent zirconia materials that can be used in the anterior region [37]. Therefore, the type and color of the cement used to lute zirconia restorations should be carefully selected. Studies on the effects of cement type and color on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies on the effects of cement type and cement color on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics.

These studies have shown that the type and color of the cement used in zirconia restorations play a crucial role in determining the final esthetic outcome. The recent introduction of 5Y-PSZ and 4Y-PSZ restorations, which offer high translucency, makes them particularly suitable for use in the anterior region. These restorations can reflect the color of the underlying tooth or abutment, thus enhancing the overall natural appearance of the restoration. However, the cement type and color become critical, especially when using highly translucent materials over substrates with different colors. For instance, when the abutment tooth or the substrate has a discolored or dark hue, the cement’s opacity becomes increasingly essential. In such cases, more opaque cements are recommended to prevent undesirable colors from reflecting the underlying structure, which can affect the final esthetic result. Therefore, it is essential to carefully consider both the tooth color and the zirconia material’s optical properties before determining the appropriate cement color and type. Additionally, the interaction between the restoration material and the cement should not be underestimated. Certain cements may alter the appearance of the zirconia, potentially leading to color mismatches. For optimal esthetic results, selecting cements that match the zirconia’s translucency or provide a slight contrast, depending on the desired effect, is crucial. This careful selection ensures the final restoration meets functional requirements and achieves a highly natural and harmonious appearance in the patient’s smile.

2.2. Effect of Restoration Thickness on the Color Change in Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics

It was reported that material thickness affected the optical properties of the material [44]. The thicker the material, the longer the path light takes through the material. As a result, more light is absorbed and diffused, and the amount of light passing through the material decreases. This causes the material to have different optical properties at various thicknesses. On the other hand, increasing the thickness of a zirconia restoration can improve its masking properties by reducing translucency [31]. Before treatment, it is necessary to determine the ideal restoration thickness under the existing conditions. Studies on the effect of zirconia thickness on the color change in the final restoration are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies on the effect of the restoration thickness on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics.

According to these studies, the final color of the restoration changes depending on the thickness of the material. New-generation zirconia ceramics generally have high translucency. However, as the thickness of zirconia restorations increases, the passage of light decreases, and the material’s ability to transmit light reduces. This helps thicker restorations become opaquer and mask the color of the underlying structure. Increasing the thickness of the zirconia restoration can be beneficial for dark-colored substrates from an esthetic perspective, as the thickness helps conceal the color of the substrate and provides a more natural appearance. However, as the thickness increases, the translucency of the restoration decreases, making it essential to maintain an esthetic balance. Therefore, the ideal thickness should be determined before treatment, ensuring a balance between esthetics and function.

2.3. Effect of Substrate Color on the Color Change in Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics

The color match between a dental restoration and the adjacent natural teeth depends partly on the degree of translucency of dental restorative material [49]. High translucent zirconia materials have recently been introduced to the market to provide high esthetics. These materials allow light to be transmitted and diffused into the restoration so that the tooth or the substructure’s color can significantly affect the final color [29]. Therefore, the background color should be carefully evaluated before treatment, and the appropriate restorative material should be selected accordingly. The studies on the effect of substrate color on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies on the effect of substrate color on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics.

According to these studies, achieving a color match in dental restorations is crucial for obtaining an esthetically pleasing result with natural teeth. Increasing the translucency of zirconia materials is a standard method to improve color matching between the restoration and natural teeth. These high-translucency zirconia materials allow light to pass through and diffuse into the restoration, enabling the underlying material’s color to influence the final color significantly. Therefore, evaluating the substrate’s color carefully before treatment is essential. Additionally, selecting the appropriate material is key to achieving esthetic and functional success. Considering the substrate color’s effect on the restoration’s overall appearance, making an informed choice is a critical step in the treatment process. This ensures patient satisfaction and long-lasting esthetic results throughout the treatment.

2.4. Effect of Sinterization on the Color Change in Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics

Sinterization is a process that allows the material to be concentrated at high temperatures under the melting temperature. This process improves the mechanical properties of the material. Sinterization methods can be classified as standard, speed, and high speed [54]. It is known that temperature and holding time at this temperature, through the application of different sintering protocols, affect the physical properties of zirconia, especially of multilayered monolithic zirconia [55,56,57,58]. Studies on the effect of sinterization on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Studies on the effect of sinterization on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics.

According to these studies, the sintering time and temperature can significantly affect the grain structure and zirconia materials’ optical properties. These parameters directly impact zirconia’s porosity and microstructure, which are key determinants of its performance. Modifying sintering parameters to increase grain size can improve translucency, making zirconia more suitable for esthetic applications. However, this comes with trade-offs: higher sintering temperatures and longer durations lead to grain growth, which can reduce the material’s mechanical strength due to phase transformations, such as the tetragonal-to-monoclinic phase transformation. Therefore, carefully optimizing sintering parameters is essential to balance translucency and strength, ensuring zirconia’s suitability for various dental and esthetic applications.

2.5. Effect of Aging on the Color Change in Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics

Dental materials are exposed to temperature changes, moisture, and mechanical effects in the mouth. These effects cause changes in material properties during the use process. Artificial aging is used to examine changes in vitro depending on the duration of use [65]. Monolithic zirconia undergoes LTD over time, starting at the surface and progressing inward. LTD reduces fracture load by 20–40%, increases surface roughness, causes microcracks, and weakens mechanical properties, regardless of surface treatment [7]. Several factors influence zirconia’s ability to withstand low-temperature degradation (LTD), including the yttria content, grain size, cubic phase content, concentrations of Al2O3 and SiO3, and the residual stress level. It was suggested that the Al2O3 content should be maintained at a minimum of 0.15 weight percent, with an optimal range of 0.15 to 0.25 weight percent, to mitigate the aging process. Lowering alumina content to enhance translucency increases the risk of susceptibility to LTD [7]. Third-generation zirconia has better-aging resistance than fourth-generation zirconia due to its higher cubic phase content [17].

The stability of the optical properties of restoration after aging is one of the main factors determining the success of the material used. After aging, the structure of zirconia may be affected, and the optical properties of the material can change. Since zirconia restorations are in direct contact with the challenges of the oral environment, such as moisture, pH changes, mechanical stresses as a source of external stress, and low temperatures critical for the stability of the tetragonal phase, different artificial aging methods have been investigated in the literature to predict the t→m phase transformation of these materials [66,67,68,69]. Ultraviolet aging caused zirconia-based restorations to become darker, yellow, redder, and more saturated, resulting in increased opacity [17]. Artificial aging processes applied to zirconia materials can generally be stored in aqueous media, hydrothermal aging, mechanical aging, hydrothermal and mechanical aging, and chemical aging. The studies on the effect of aging on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Studies on the effect of aging on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics.

Zirconia restorations are exposed to various challenges in the oral environment, including temperature fluctuations from hot and cold foods, mechanical stresses from mastication, and pH variations caused by dietary acids and salivary changes. These factors can cumulatively impact the long-term performance and color stability of zirconia. Multiple artificial aging methods, such as thermomechanical cycling, hydrothermal aging, and chemical immersion, are employed to assess their behavior under these conditions accurately. These methods simulate the oral environment to predict the material’s resistance to wear, fracture, and degradation over time. Studies consistently highlight that aging processes can significantly alter the color of zirconia. For instance, hydrothermal aging, which mimics the effects of moisture at elevated temperatures, can induce low-temperature degradation or tetragonal to monoclinic phase transformation. This transformation is accompanied by microcracking, surface roughness, and increased opacity, which may compromise the esthetic quality of restorations. Also, prolonged exposure to acidic conditions has further exacerbated surface changes, potentially affecting translucency and color stability. Mechanical aging through cyclic loading also impacts zirconia’s optical and structural integrity. Fatigue stresses can propagate cracks and induce changes in surface texture, leading to diminished light transmission. Furthermore, combining aging factors, such as simultaneous thermomechanical cycling and pH exposure, amplifies the degradation effects, providing a more comprehensive understanding of zirconia’s long-term performance. These findings underscore the importance of optimizing zirconia’s composition and sintering parameters to enhance resistance against aging-induced changes. Advanced formulations, such as multilayered zirconia with graded translucency and strength, are being developed to address these challenges. Such innovations aim to maintain zirconia’s esthetic and mechanical properties over extended clinical use.

2.6. Effect of Zirconia Type on the Color Change in Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics

Zirconia ceramics are optically semi-translucent and structurally based on yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystals. These ceramics are categorized into four types: low, medium, super, and ultra translucency. Moreover, multilayer zirconia ceramics have been developed to replicate a natural tooth’s translucency and color gradient from the incisal to the cervical section [53]. The translucency of zirconia material has been enhanced through various modifications to achieve restorations with properties similar to the natural tooth structure. Multiple types of zirconia are used in dental applications, including partially stabilized zirconia (PSZ), tetragonal zirconia polycrystal (TZP), zirconia toughened alumina (ZTA), and fully cubic stabilized zirconia (CSZ). With the development of new generations of zirconia, significant efforts have been made to enhance the material’s esthetic properties, particularly its color and translucency. These improvements are achieved by modifying the microstructure of zirconia, such as altering the composition of Y-TZP to influence grain size, phase distribution, and light transmission. For instance, higher yttria content in newer generations, like 4Y-PSZ and 5Y-PSZ, increases translucency by reducing the light-scattering tetragonal phase while balancing strength and toughness. These advancements aim to make zirconia restorations more natural-looking and suitable for demanding esthetic zones, bridging the gap between mechanical durability and visual appeal [16,32]. Restorations made with the full-contour technique using 4Y-TZP-MT are the darkest and most translucent, while those made with 3Y-TZP-LT are the lightest and least translucent [17].

Another factor affecting zirconia ceramics’ optical properties is the production technique. Various methods are used in the production of zirconia restorations. Since its introduction in the 1970s, subtractive computer-aided manufacturing technology, such as milling, has become the primary method for producing zirconia restorations. These restorations can be made using soft machining (milling of pre-sintered blocks followed by sintering) and hard machining (milling of fully sintered blocks). The soft machining method, commonly used for yttrium-stabilized zirconia, results in a homogeneous distribution of components and a small pore size. The material undergoes a 25% volumetric shrinkage during sintering, achieving its final mechanical properties. This method produces stable cores with predominantly tetragonal zirconia and minimal monoclinic phase [75]. In contrast, hard machining eliminates shrinkage but may cause phase transformation, leading to low-temperature degradation and microcracks, which can shorten the restoration’s lifespan. Hard machining also requires specialized machines and durable cutting tools. Although hard machining offers better marginal fit than soft machining because it does not require sintering and thus avoids shrinkage, it negatively impacts the mechanical properties of zirconia [76]. On the other hand, additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing processes, offers a promising alternative to traditional subtractive methods. Three-dimensional printing has become an indispensable tool in biomedical engineering in recent years. This technology enables the creation of three-dimensional structures by depositing materials layer by layer, guided by a digital model. Three-dimensional printing facilitates the production of complex geometric designs with high precision, making it widely applicable in dentistry [77,78]. A systematic review by Alghouli et al. [79] concluded that the esthetic performance of 3D-printed zirconia crowns was superior to milled zirconia crowns. Specifically, 3D-printed zirconia crowns exhibited a significantly better color match and contour alignment with adjacent natural teeth, enhancing their overall appearance and blending seamlessly within the oral cavity. This superior esthetic outcome can be attributed to the precision and customizability offered by 3D printing technology, which allows for finer detail and greater adaptability to individual patient needs. These findings underscore the potential of 3D-printed zirconia crowns as a promising alternative to traditionally milled zirconia restorations. Recent research on 3D-printed zirconia ceramics has increasingly focused on stereolithography-based technologies, which are considered highly promising. A few manufacturers now offer stereolithography-based zirconia printing, showing potential for dental applications [75]. Studies related to 3D-printed zirconia ceramics generally focused on the microstructure of the material, mechanical properties, and dimensional accuracies [80,81,82,83,84]. There is a lack of information on the factors affecting the color of 3D-printed zirconia ceramics.

Due to the complex optical properties of natural teeth, achieving optimum color matching and pleasing esthetics in dental restorations has always been challenging for dentists. Dentists can achieve successful restorations with sufficient knowledge about dental materials’ usage instructions and optical properties [85]. Studies have shown that the type of zirconia block used affects optimum color match and esthetics [85,86,87]. However, there are limited studies in the literature on this subject. According to the differences in yttrium oxide content, different types of zirconia have different translucency values, and the increase in yttrium content increased the translucency [3]. The studies on the effect of zirconia type on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Studies on the effect of zirconia type on the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics.

These studies have shown that the optical properties of zirconia restorations are influenced by material composition and translucency properties. Studies on monolithic multilayer pre-colored zirconia ceramics with different yttria levels and thicknesses indicate that high-translucency zirconia exhibits more significant color variations, with some types exceeding clinically acceptable color differences. Additionally, investigations into the effects of yttria content and thickness on zirconia’s optical properties suggest that 4Y-PSZ and 5Y-PSZ ceramics result in improved translucency and color accuracy compared to 3Y-TZP. These findings highlight the importance of selecting the appropriate zirconia type and translucency level to achieve optimal esthetic outcomes in zirconia restorations.

3. Conclusions

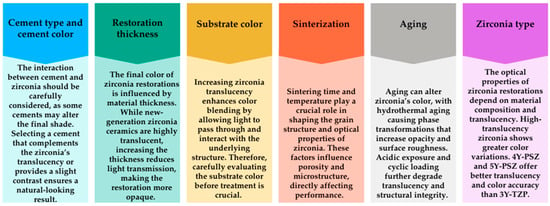

In this narrative review, the factors affecting the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics are categorized into six main groups: cement type and color, restoration thickness, substrate color, sintering, aging, and zirconia type. A brief summary of these factors is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A brief summary of the factors affecting the color change in monolithic zirconia ceramics.

Several types of zirconia ceramics are available on the market, each with different properties. Studies comparing these various zirconia ceramics have shown that the material type affects the optical properties of restorations. To obtain an esthetic restoration, it is essential to examine existing conditions, such as the color of the abutment tooth and the amount of preparation required, before beginning the treatment process. Therefore, dentists need to understand the properties of various zirconia ceramics to select the most appropriate material according to the patient’s needs. Additionally, the intraoral application of the restoration should be performed using the proper cementation technique. Future research should focus on a more detailed examination of the optical and mechanical properties of different types of zirconia ceramics. Developing new materials and identifying the most suitable restoration methods for clinical applications are expected to play a crucial role in enhancing both the esthetic and functional success of zirconia restorations. Research should focus on developing new material formulations that improve the esthetic and mechanical properties of zirconia ceramics, particularly those that enhance light transmittance and durability. Long-term clinical studies must determine how zirconia restorations perform in the intraoral environment over time. These studies could help assess zirconia ceramics’ durability, color changes, and mechanical stability. Standardizing the tests to evaluate zirconia ceramics’ optical and mechanical properties could improve the comparability of data from different studies. Future research could also focus on several key aspects to enhance the esthetic and functional success of zirconia restorations. First, studies could explore the development of new zirconia formulations aimed at improving esthetic and mechanical properties by discovering additives or processing techniques.

Additionally, more research is needed on the long-term clinical outcomes of zirconia restorations, including their durability, color stability, and functional performance. Comparative studies between zirconia and other restoration materials like porcelain could identify situations where zirconia offers distinct advantages regarding esthetic harmony and longevity. Research into the interaction between zirconia and cement is also crucial, as it would be valuable to understand which cement types achieve the best color match with zirconia and prevent color changes over time. Furthermore, studies on the impact of zirconia veneer thickness on esthetics could help determine the minimum thickness required to ensure color harmony and durability. Finally, there is a need to develop more precise spectrophotometric methods to measure the color match of zirconia restorations. These studies could significantly contribute to achieving more accurate color matching in clinical practice, thus enhancing the overall esthetic success of zirconia restorations.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Y-TZP | Yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystals |

| Y-PSZ | Yittria-partially stabilized zirconia |

| wt. | weight |

| CAD-CAM | Computer-aided design-Computer-aided manufacturing |

| TP | Translucency parameter |

| UTML | Ultra translucent multi-layered |

| LTD | Low-temperature degradation |

References

- Alrabeah, G.; Al-Sowygh, A.H.; Almarshedy, S. Use of ultra-translucent monolithic zirconia as esthetic dental restorative material: A narrative review. Ceramics 2024, 7, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, L.; Grădinaru, M.; Rîcă, R.; Mărășescu, P.; Stan, M.; Manolea, H.; Ionescu, A.; Moraru, I. Zirconia use in dentistry—manfacturing and properties. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2019, 45, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Kim, S.H. Optical properties of pre-colored dental monolithic zirconia ceramics. J. Dent. 2016, 55, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, S. Development and characterization of ultra-high translucent zirconia using new manufacturing technology. Dent. Mater. J. 2023, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, R., II. Ceramics overview. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 232, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Advances in zirconia-based dental materials: Properties, classification, applications, and future prospects. J. Dent. 2024, 147, 105111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Ghulam, O.; Krsoum, M.; Binmahmoud, S.; Taher, H.; Elmalky, W.; Zafar, M.S. Revolution of current dental zirconia: A comprehensive review. Molecules 2022, 27, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, S. Classification and properties of dental zirconia as implant fixtures and superstructures. Materials 2021, 14, 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghodsi, S.; Jafarian, Z. A Review on Translucent Zirconia. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2018, 26, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekkan, G.; Özcan, M.; Subaşı, M.G. Clinical factors affecting the translucency of monolithic Y-TZP ceramics. Odontology 2020, 108, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denry, I.; Kelly, J.R. State of the art of zirconia for dental applications. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güth, J.F.; Stawarczyk, B.; Edelhoff, D.; Liebermann, A. Zirconia and its novel compositions: What do clinicians need to know? Quintessence Int. 2019, 50, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kui, A.; Manziuc, M.; Petruțiu, A.; Buduru, S.; Labuneț, A.; Negucioiu, M.; Chisnoiu, A. Translucent zirconia in fixed prosthodontics—An integrative overview. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshpooy, M.; Pournaghi Azar, F.; Alizade Oskoee, P.; Bahari, M.; Asdagh, S.; Khosravani, S.R. Color agreement between try-in paste and resin cement: Effect of thickness and regions of ultra-translucent multilayered zirconia veneers. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2019, 13, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmajeed, A.; Sulaiman, T.A.; Abdulmajeed, A.A.; Närhi, T.O. Strength and phase transformation of different zirconia types after chairside adjustment. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 132, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardhaman, S.; Borba, M.; Kaizer, M.R.; Kim, D.K.; Zhang, Y. Optical and mechanical properties of the multi-transition zones of a translucent Zirconia. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano Moncayo, A.M.; Peñate, L.; Arregui, M.; Giner-Tarrida, L.; Cedeño, R. State of the art of different zirconia materials and their indications according to evidence-based clinical performance: A narrative review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malallah, A.D.; Hasan, N.H. Thickness and yttria percentage influence the fracture resistance of laminate veneer zirconia restorations. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022, 8, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongkiatkamon, S.; Rokaya, D.; Kengtanyakich, S.; Peampring, C. Current classification of zirconia in dentistry: An updated review. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaian, F. Color in zirconia-based restorations and related factors: A literature review. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 27, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekkan, G.; Pekkan, K.; Bayindir, B.Ç.; Özcan, M.; Karasu, B. Factors affecting the translucency of monolithic zirconia ceramics: A review from materials science perspective. Dent. Mater. J. 2020, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paravina, R.D.; Ghinea, R.; Herrera, L.J.; Bona, A.D.; Igiel, C.; Linninger, M.; Mar Perez, M.D. Color difference thresholds in dentistry. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2015, 27, S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouhar, R.; Ahmed, M.A.; Khurshid, Z. An overview of shade selection in clinical dentistry. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paravina, R.D. Performance assessment of dental shade guides. J. Dent. 2009, 37, e15–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, K.M.; Devigus, A.; Igiel, C.; Wentaschek, S.; Azar, M.S.; Scheller, H. Repeatability of color-measuring devices. Eur. J. Esthet. Dent. 2011, 6, 428–435. [Google Scholar]

- Tabatabaian, F.; Beyabanaki, E.; Alirezaei, P.; Epakchi, S. Visual and digital tooth shade selection methods, related effective factors and conditions, and their accuracy and precision: A literature review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 1084–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, N.R.; Bansod, A.; Reche, A.; Dubey, S.A. Aesthetic and functional rehabilitation for dentogingival asymmetry using zirconia restorations. Cureus 2024, 16, e63558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, G.; Donmez, M.B.; Kashkari, A.; Johnston, W.M.; Yilmaz, B. Effect of thickness, cement shade, and coffee thermocycling on the optical properties of zirconia reinforced lithium silicate ceramic. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comba, A.; Paolone, G.; Baldi, A.; Vichi, A.; Goracci, C.; Bertozzi, G.; Scotti, N. Effects of substrate and cement shade on the translucency and color of CAD/CAM lithium-disilicate and zirconia ceramic materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayash, G.; Osman, E.; Segaan, L.; Rayyan, M.; Joukhadar, C. Influence of resin cement shade on the color and translucency of zirconia crowns. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2020, 12, e257–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekled, S.; Elwazeer, S.; Jurado, C.A.; White, J.; Faddoul, F.; Afrashtehfar, K.I.; Fischer, N.G. Ultra-translucent zirconia laminate veneers: The influence of restoration thickness and stump tooth-shade. Materials 2023, 16, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manziuc, M.M.; Gasparik, C.; Negucioiu, M.; Constantiniuc, M.; Burde, A.; Vlas, I.; Dudea, D. Optical properties of translucent zirconia: A review of the literature. EuroBiotech J. 2019, 3, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.; Palacios, N.; Ricardo, A.J.O. Zirconia cementation: A systematic review of the most currently used protocols. Open Dent. J. 2024, 18, e18742106300869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.L.; Castillo-Oyagüe, R.; Lynch, C.D.; Montero, J.; Albaladejo, A. Influence of sandblasting granulometry and resin cement composition on microtensile bond strength to zirconia ceramic for dental prosthetic frameworks. J. Dent. 2013, 41, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.A.; Al Kheraif, A.; Jamaluddin, S.; Elsharawy, M.; Divakar, D.D. Recent trends in surface treatment methods for bonding composite cement to zirconia: A review. J. Adhes. Dent. 2017, 19, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, B.; Hao, P. Does the internal surface treatment technique for enhanced bonding affect the color, transparency, and surface roughness of ultra-transparent zirconia? Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahmiri, R.; Standard, O.C.; Hart, J.N.; Sorrell, C.C. Optical properties of zirconia ceramics for esthetic dental restorations: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, S.; Bagis, B. Effect of resin cement and ceramic thickness on final color of laminate veneers: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013, 109, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkondu, O.; Tinastepe, N.; Kazazoglu, E. Influence of type of cement on the color and translucency of monolithic zirconia. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 116, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayindir, F.; Koseoglu, M. The effect of restoration thickness and resin cement shade on the color and translucency of a high-translucency monolithic zirconia. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 123, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabatabaian, F.; Habib Khodaei, M.; Namdari, M.; Mahshid, M. Effect of cement type on the color attributes of a zirconia ceramic. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2016, 8, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravani, S.R.; Kahnamoui, M.A.; Kimyai, S.; Navimipour, E.J.; Mahounak, F.S.; Azar, F.P. Final colour of ultra translucent multilayered zirconia veneers, effect of thickness, and resin cement shade. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 2555797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakrana, A.A.; Laith, A.; Elsherbini, A.; Elerian, F.A.; Özcan, M.; Al-Zordk, W. Influence of resin cement on color stability when luting lithium disilicate and zirconia restorations. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 2023, 18, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.B.; Han, J.S.; Yeo, I.S.; Ha, S.R. Effect of the amount of thickness reduction on color and translucency of dental monolithic zirconia ceramics. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2016, 8, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaian, F.; Aflatoonian, K.; Namdari, M. Effects of veneering porcelain thickness and background shade on the shade match of zirconia-based restorations. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2019, 13, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.H.; Kim, S.G. Effect of abutment shade, ceramic thickness, and coping type on the final shade of zirconia all-ceramic restorations: In vitro study of color masking ability. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2015, 7, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabatabaian, F.; Khaledi, Z.; Namdari, M. Effect of ceramic thickness and cement type on the color match of high-translucency monolithic zirconia restorations. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 34, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.M.; Peng, T.Y.; Huang, H.H. Effects of thickness of different types of high-translucency monolithic multilayer precolored zirconia on color accuracy: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 587.e1–587.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suputtamongkol, K.; Tulapornchai, C.; Mamani, J.; Kamchatphai, W.; Thongpun, N. Effect of the shades of background substructures on the overall color of zirconia-based all-ceramic crowns. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2013, 5, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonza, Q.N.; Della Bona, A.; Pecho, O.E.; Borba, M. Effect of substrate and cement on the final color of zirconia-based all-ceramic crowns. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaian, F.; Masoomi, F.; Namdari, M.; Mahshid, M. Effect of three different core materials on masking ability of a zirconia ceramic. J. Dent. 2016, 13, 340–348. [Google Scholar]

- Ansarifard, E.; Taghva, M.; Mosaddad, S.A.; Akhlaghian, M. The impact of various substrates, ceramic shades, and brands on the ultimate color and masking capacity of highly translucent monolithic zirconia: An in vitro study. Odontology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoveizi, R.; Baghaei, M.; Tavakolizadeh, S.; Tabatabaian, F. Color match of ultra-translucency multilayer zirconia restorations with different designs and backgrounds. J. Prosthodont. 2024, 33, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skienhe, H.; Habchi, R.; Ounsi, H.; Ferrari, M.; Salameh, Z. Evaluation of the effect of different types of abrasive surface treatment before and after zirconia sintering on its structural composition and bond strength with resin cement. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1803425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juntavee, N.; Juntavee, A.; Jaralpong, C. Color characteristics of high yttrium oxide-doped monochrome and multilayer partially stabilized zirconia upon different sintering parameters. Eur. J. Dent. 2024, 19, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebeid, K.; Wille, S.; Hamdy, A.; Salah, T.; El-Etreby, A.; Kern, M. Effect of changes in sintering parameters on monolithic translucent zirconia. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, e419–e424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafaei, F.; Shahbazi, A.; Hooshyarfard, A.; Najafi, A.H.; Ebrahimi, M.; Farhadian, M. Effect of sintering temperature on translucency parameter of zirconia blocks. Dent. Res. J. 2022, 19, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Kilinc, H.; Sanal, F.A. Effect of sintering and aging processes on the mechanical and optical properties of translucent zirconia. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 129.e1–129.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah, K.; Sherif, A.H.; Mandour, M.H.; Nossair, S.A. Optical effect of rapid sintering protocols on different types of zirconia. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 130, 253.e1–253.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, L.; Yang, M.; Chen, J.; Xing, W. The effect of deviations in sintering temperature on the translucency and color of multi-layered zirconia. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giti, R.; Mosallanezhad, S. Effect of sintering temperature on color stability and translucency of various zirconia systems after immersion in coffee solution. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan Shohdy, E.I.; Sabet, A.; Sherif, A.H.; Salah, T. The effect of speed sintering on the optical properties and microstructure of multi-layered cubic zirconia. J. Prosthodont. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engler, M.L.P.D.; Kauling, A.E.C.; Silva, J.; Rafael, C.F.; Liebermann, A.; Volpato, C.A.M. Influence of sintering temperature and aging on the color and translucency of zirconia. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, Y.M.; Shahin, H.; Halawani, M. Effect of sintering technıque on the color coordınates of a translucent zirconium ceramic material. Alex. Dent. J. 2024, 49, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo-Júnior, E.N.S.; Bergamo, E.T.P.; Bastos, T.M.C.; Benalcázar Jalkh, E.B.; Lopes, A.C.O.; Monteiro, K.N.; Cesar, P.F.; Tognolo, F.C.; Migliati, R.; Tanaka, R.; et al. Ultra-translucent zirconia processing and aging effect on microstructural, optical, and mechanical properties. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, G.M.; Zykus, A.; Ghahnavyeh, R.R.; Lawrence, S.K.; Bahr, D.F. Effect of accelerated aging on dental zirconia-based materials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 65, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathy, S.M.; El-Fallal, A.A.; El-Negoly, S.A.; El Bedawy, A.B. Translucency of monolithic and core zirconia after hydrothermal aging. Acta Biomater Odontol Scand 2015, 1, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angela Mazıero Volpato, C.; Francısco Cesar, P.; Antônıo Bottıno, M. Influence of accelerated aging on the color stability of dental zirconia. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2016, 28, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou-Kyrana, K.; Fasoula, M.; Kontonasaki, E. Translucency of monolithic zirconia after hydrothermal aging: A review of in vitro studies. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Kim, S.H. Effect of hydrothermal aging on the optical properties of precolored dental monolithic zirconia ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, S.; Shinya, A.; Koizumi, H.; Vallittu, P.; Lassila, L.; Fujisawa, M. Effect of low-temperature degradation and sintering protocols on the color of monolithic zirconia crowns with different yttria contents. Dent. Mater. J. 2024, 43, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arindham, R.S.; Nandini, V.V.; Boruah, S.; Marimuthu, R.; Surya, R.; Lathief, J. Evaluation of the surface roughness and color stability of two types of milled zirconia before and after immersion in alcoholic beverages: An in vitro study. Cureus 2024, 16, e64695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abounassif, F.M.; Alfaraj, A.; Gadah, T.; Yang, C.C.; Chu, T.G.; Lin, W.S. Color stability of precolored and extrinsically colored monolithic multilayered polychromatic zirconia: Effects of surface finishing and aging. J. Prosthodont. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.G. Effect of low-temperature degradation treatment on hardness, color, and translucency of single layers of multilayered zirconia. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 133, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanlar, L.N.; Salazar Rios, A.; Tahmaseb, A.; Zandinejad, A. Additive Manufacturing of Zirconia Ceramic and Its Application in Clinical Dentistry: A Review. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Al-Wahadni, A.; Masri, R. Zirconia-based restorations: Literature review. Int. J. Med. Res. Prof. 2017, 3, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Mohd Ripin, Z. 4D printing in biomedical engineering: Advancements, challenges, and future directions. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revilla-León, M.; Meyer, M.J.; Zandinejad, A.; Özcan, M. Additive manufacturing technologies for processing zirconia in dental applications. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2020, 23, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Alghauli, M.; Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Wille, S.; Kern, M. 3D-printed versus conventionally milled zirconia for dental clinical applications: Trueness, precision, accuracy, biological and esthetic aspects. J. Dent. 2024, 144, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revilla-León, M.; Husain, N.A.H.; Ceballos, L.; Özcan, M. Flexural strength and Weibull characteristics of stereolithography additive manufactured versus milled zirconia. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Mostafavi, D.; Methani, M.M.; Zandinejad, A. Manufacturing accuracy and volumetric changes of stereolithography additively manufactured zirconia with different porosities. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, H.; Inokoshi, M.; Nozaki, K.; Komatsu, K.; Kamijo, S.; Liu, H.; Shimizubata, M.; Minakuchi, S.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Vleugels, J.; et al. Additively manufactured zirconia for dental applications. Materials 2021, 14, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, J. Dimensional accuracy and clinical adaptation of ceramic crowns fabricated with the stereolithography technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branco, A.C.; Colaço, R.; Figueiredo-Pina, C.G.; Serro, A.P. Recent advances on 3D-printed zirconia-based dental materials: A review. Materials 2023, 16, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafaei, F.; Izadi, A.; Abbasi, S.; Farhadian, M.; Bagheri, Z. Comparison of optical properties of laminate veneers made of Zolid FX and Katana UTML zirconia and lithium disilicate ceramics. Front. Dent. 2019, 16, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.M.; Peng, T.Y.; Shimoe, S. Color accuracy of different types of monolithic multilayer precolored zirconia ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 124, 789.e1–789.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.M.; Peng, T.Y.; Wu, Y.A.; Hsieh, C.F.; Chi, M.C.; Wu, H.Y.; Lin, Z.C. Comparison of optical properties and fracture loads of multilayer monolithic zirconia crowns with different yttria levels. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).