Abstract

Non-covalent contacts play a significant role in binding between fragments in supramolecular assemblies. Understanding the non-covalent binding capabilities of closo-borate anions and their derivatives is a significant research challenge, due to their ability to interact with biomolecules. The present work was focused on the theoretical study of non-covalent complexes between glycine and closo-borate anions [BnHn−1X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2). The main binding patterns between glycine and cluster systems were defined, and the effect of the exo-polyhedral substituent on the stability of non-covalent complexes was analysed. Complexes based on ammonium and hydroxy derivatives of closo-borate anions [BnHn−1X]y− (X = NH3, OH; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2) were the most stable among all the derivatives considered. The findings of this work can be applied to the design of non-covalent complexes of closo-borate systems with biomolecules.

1. Introduction

Non-covalent interactions (NCIs) are one of the cornerstones of modern chemistry and related sciences [1,2]. Their formation is a driving force in numerous chemical and biological processes and is essential for the development and maintenance of life on Earth [3,4,5]. Even though some NCIs have low energy values, these contacts determine the structures of many complex systems, such as supramolecular assemblies, biomolecules, metal–organic frameworks, and many others [6,7,8,9,10]. To date, various types of non-covalent contacts have been studied. The most studied and best-known NCIs are hydrogen bonds of the general type DnH···Ac (Dn = donor, Ac = acceptor) [11,12,13,14]. Atoms such as nitrogen, oxygen and fluorine can function as both donors and acceptors [15,16,17,18]. The range of energy values of hydrogen bonds varies from 0.5 to more than 40 kcal/mol [19,20]. In addition to inorganic systems, hydrogen bonds play a crucial role in the structuring of biomolecules. In particular, they define the secondary structure of proteins and impact significantly upon the binding of small molecules to the active sites of proteins [21,22].

Closo-borate anions [BnHn]2− (n = 6–12) and related compounds such as carboranes and metallaboranes contain negatively charged exo-polyhedral hydrogen atoms. The unique structure of these systems enables the formation of hydrogen bonds and other NCIs, such as halogen bonding and BH···π contacts, with various organic and organoelement systems [23,24,25,26,27,28].

The interactions of [B10H10]2− and [B12H12]2− with various alcohols were described in the work of Shubina et al. [29], where the main type of interactions was OH···HB contacts. The strength of these contacts for closo-borate anions was less than that of the [BH4]− anion and decreased from [B10H10]2− to [B12H12]2−. Non-covalent complexes of the polyhedral carborane CB11H12 with several amino acids, such as glycine, serine, phenylalanine, glutamic acid, lysine, and arginine, were calculated in vacuo [30]. It was shown that the dominant interaction between carboranes and biomolecules was the formation of dihydrogen bonds characterised by a short distance between hydrogen atoms (as close as 1.8 Å). Average energy values of such contacts were in the range of 4.2 to 5.8 kcal/mol. The molecular assemblies of heteroboranes with Ala–Gly–Ala–Ala tetrapeptides were calculated [31]. In this work, calculations were performed using the implicit solvent model, and the effect of solvation on the stability of non-covalent complexes was described.

The ability of NCI formation determines the application of cluster-based compounds as drugs against various diseases [32,33,34]. A current example of the application of boron clusters is Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT) [35,36,37,38,39,40]. For effective treatment, the selective accumulation of boron clusters in tumour cells is required. L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) is a critical molecular target in BNCT therapy [41,42,43,44,45]. In the work of Y. Zhang et al., assemblies of LAT1 with several conjugates of boron clusters with amino acids were studied by means of docking modelling [44]. Data analysis revealed that the introduction of one of the conjugates of carborane with an amino acid into the protein resulted in the formation of hydrogen bonds between nitrogen and oxygen atoms and tyrosine 254 and asparagine 258, respectively. In several works, metallacarborane derivatives have been shown to be effective inhibitors of HIV-1 protease [46,47]. Applying the hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations, the binding of a metallacarborane-based inhibitor to HIV-1 protease was interpreted through atomistic and energy details [48]. Combining X-ray crystallography and quantum–chemical calculations has demonstrated the significant role of B–H⋯π hydrogen bonding in inhibiting carbonic anhydrase II by carborane sulfonamides [49].

As has been described, much theoretical work has been carried out on the NCIs of carborane and metallaborane systems with bioorganic systems [30,31,44,48,50], but the literature on closo-borate [BnHn]2− (n = 6–12) systems remains limited. Thus, one of the motivations of the present study was to redress the balance. The focus of this study has been on molecular complexes of [BnHn−1X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2) with glycine, with an assessment being made of the effect of the exo-polyhedral substituent on the cluster’s propensity to form non-covalent complexes. Glycine is the simplest amino acid, but its zwitterion form contains negatively charged carboxyl COO− and positively charged ammonium NH3+ groups. The preferable site of binding with boron clusters was identified, and several isomers of non-covalent complexes were localised. The authors determined the nature of NCIs between glycine and boron clusters and evaluated the stability of the resulting molecular assemblies.

2. Computational Details

All calculations of molecular complexes of [BnHn−1X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2) with glycine were carried out using the ORCA 6.0.1 program package [51]. The initial geometry pre-optimisation and conformational scanning of key geometrical parameters, specifically the cluster–glycine distance and the rotation of the NH3+ and COO− functional groups of the amino acid, were performed at the r2SCAN-3c level of theory. Further geometry optimisation of the most energetically favourable isomers was performed at the ωB97X-D4rev/def2-TZVPP level of theory [52,53,54]. Range-separated DFT functionals combined with large triple-zeta basis sets enabled the calculation of the electronic structure and energy aspects of non-covalent molecular complexes to a high level of accuracy [55,56,57]. Tight criteria of SCF convergence (Tight SCF) were used for the calculations, which were performed using the RIJCOSX approximation with the def2/J auxiliary basis set [54,58,59]. Solvent effects were considered using the Solvation Model based on Density (SMD) [60], and water was chosen as the solvent. As glycine exists as a zwitterion under physiological conditions, it was used in this form for the current work. The singlet spin state was the ground state for all systems investigated. Only equatorial isomers of closo-decaborate anions [B10H9X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; y = 1, 2) were considered. Equatorial isomers are more energetically stable and easier to obtain than apical systems. Consequently, they are more extensively described in the literature [61,62,63,64,65]. Symmetry operations were not applied during the geometry optimisation procedure. Hessian matrices were calculated analytically for all model structures to prove the location of the correct minima on potential energy surfaces. No imaginary frequencies were found in any case. For an accurate evaluation of the electronic structures of the systems under consideration, additional single-point calculations at the Domain-based Local Pair Natural Orbital Coupled-Cluster with Single, Double, and perturbative Triples excitation method DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVPP level were made [66,67,68]. Topological analysis of the NCI electron density distribution within the Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) formalism [69,70,71], developed by Bader, was carried out using the Multiwfn program (version 3.8) [72]. A brief description of the main electron density descriptors is provided in the ESI. Energy values of NCIs were estimated based on the Espinosa–Lecomte correlation (Equation (1)):

where V(rbcp)—potential energy density; rbcp—radius vector of coordinates of bond critical point; and ½ coefficient is in volume units (Å3). For convenience, all energy values of NCIs are presented in kcal/mol (1 hartree = 627.509 kcal/mol).

The stability constant of the complex based on closo-borate anions and its derivatives with glycine was calculated according to the following equation (Equation (2)):

where acomplex—activity of molecular complex of closo-borate anion and glycine; acloso-borate—activity of closo-borate anion; aglycine—activity of glycine; ∆G—free Gibbs energy of the complexation reaction, kcal/mol; R—universal gas constant, 0.001987 kcal/K × mol; and T = 298.15 K.

The interaction energy, Eint, is the difference between the energy of the complex and the sum of the energies of interacting units with their geometries taken from the geometry of the complex. For an accurate estimate of Eint (Equation (3)), the full counterpoise correction technique of estimating basis set superposition errors (BSSE) was implemented [73].

Ebin considers the deformation of these units resulting from the complexation (Equation (4)).

where Eint—interaction energy, and Edef—the energy needed to distort the fragments from their equilibrium configuration to the interacting geometry.

The bonding interactions between boron clusters and glycine were analysed by applying the Extended Transition State–Natural Orbitals for Chemical Valence decomposition scheme (ETS-NOCV) [74,75,76]. These calculations were carried out using the ORCA 6.1.0 program package. The ETS method decomposes the energy associated with bond formation into four components (Equation (5)):

where ∆Eelstat—electrostatic interaction between molecular species (closo-borate anion and glycine); ∆EPauli—exchange repulsion between molecular species; ∆Eorb—interaction between the occupied and unoccupied orbitals of two molecular species; and ∆Edisp—dispersion contribution to the interaction between molecular species.

The deformation density shows the electron density rearrangement taking place upon the complex formation [75]. The visualisation of the optimised structures and deformation density was carried out using the ChemCraft program (version 1.8) [77]. XYZ files with coordinates of all optimised structures can be found in the attached zip folder.

3. Results

3.1. Complex of [BnHn]2− Clusters with Glycine

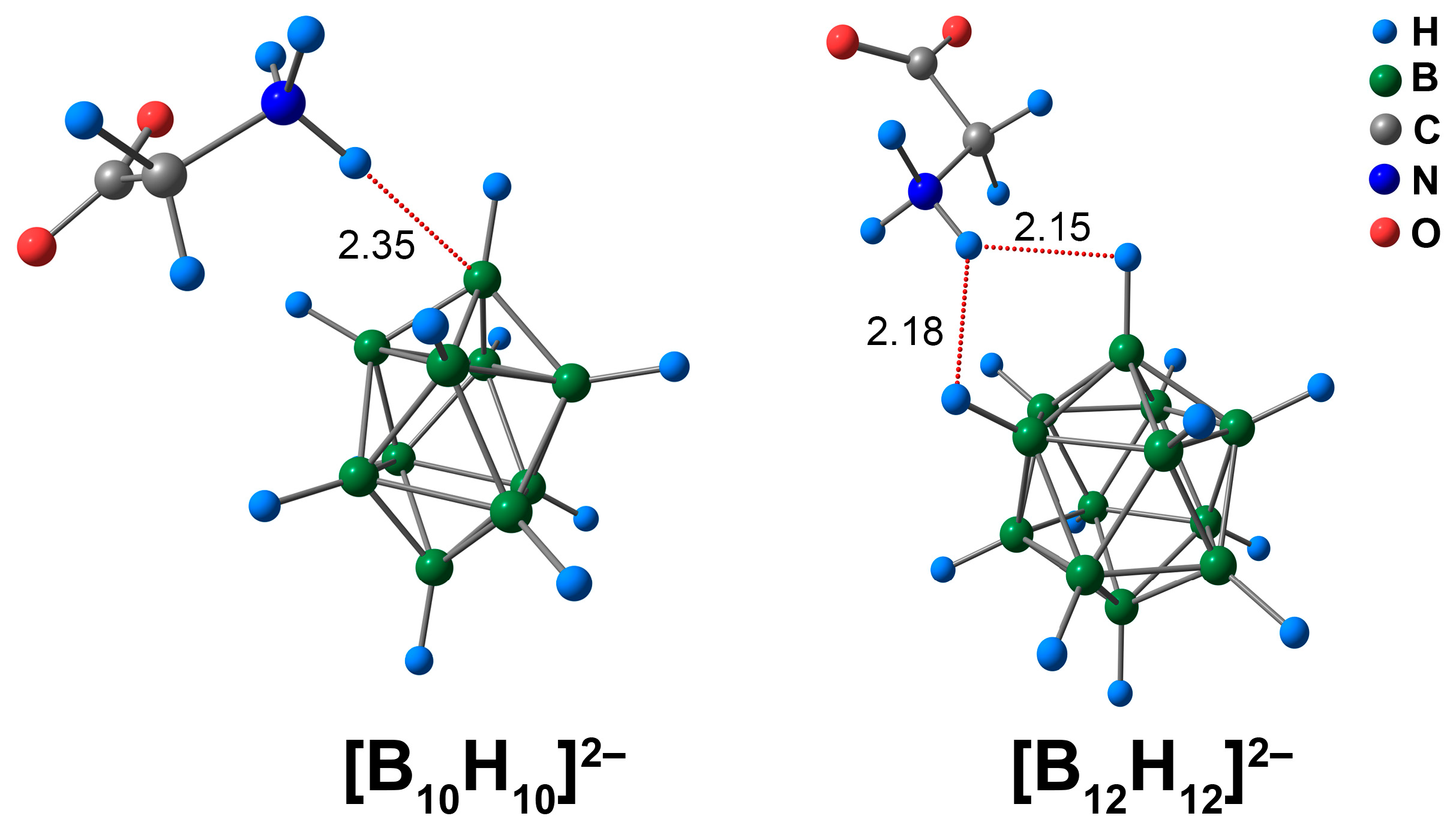

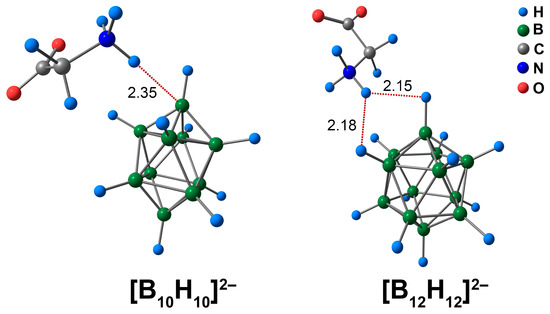

Characterisation of the molecular complexes of [BnHn]2− (n = 10, 12) anions with glycine began with a consideration of the geometric parameters of the intermolecular contacts between amino acid and cluster anions. The ammonium group NH3 was positively charged and attracted to the negatively charged atoms of the boron cluster. Thus, the contact between the atoms of the NH3 group and the cluster cage was the shortest. In the case of [B10H10]2−, the length of the contact between the ammonium hydrogen atom and the apical hydrogen atom of the cluster was equal to 2.14 Å. The spacing between the amine hydrogen atom of the NH3 group and the apical boron atom was equal to 2.35 Å (Figure 1). As the distance between the NH3-group and the apical hydrogen atom was the shortest, it was expected that the study would find a bonding path between the exo-polyhedral hydrogen atom and the hydrogen atom of the NH3-group by QTAIM analysis. However, the bonding path occurred between the hydrogen atom of the NH3-group and the apical boron atom of the cluster cage (Figure S1). Similar results were obtained in the case of the DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculation. Applying the Espinosa–Lecomte correlation (Equation (1)), the energy of the NH⋯B interaction was found to be equal to 2.6 kcal/mol (2.8 kcal/mol for DLPNO-CCSD(T)). In addition, contacts between the CH2 group of glycine and the cluster cage were observed. The energy value of these contacts was equal to 0.9 kcal/mol, both for the ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Optimised structures of molecular complexes of [BnHn]2− (n = 10, 12) anions with glycine. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. The lengths of main NCIs are given in Å.

In the case of the [B12H12]2− anion, one of the ammonium hydrogen atoms had two practically equal contacts with two neighbouring cluster hydrogens. The lengths of these contacts were equal to 2.15 and 2.18 Å. For the [B12H12]2− anion, there was a difference between the QTAIM results and those of the ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) levels of theory. Based on the DFT calculation, the hydrogen of the ammonium group had only one contact with the hydrogen atom of the cluster cage. DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations revealed that the NH3 hydrogen atom formed two bonding paths with two different hydrogen atoms. Since the lengths of two NH⋯HB contacts were almost equivalent, one can expect the occurrence of two bonding paths between the NH3 group and the boron cluster. Thus, the results of the DLPNO-CCSD(T) appeared to be more reasonable. The DLPNO-CCSD(T) values of energy of NH⋯BH contacts lie in the range of 1.8 to 1.9 kcal/mol. Based on the values of electron density descriptors at bcp and the value of non-covalent interaction energy, it can be concluded that the NH⋯B contact was stronger in the case of the [B10H10]2− complex than the NH⋯HB contacts in the case of the [B12H12]2− assembly with glycine. In the case of carborane-based molecular assemblies with biomolecules, it was revealed that the energy of NH⋯HB contacts was in the range of 2.1 to 5.8 kcal/mol [30]. Thus, the NH⋯HB and NH⋯B contacts found in the present work had energies similar to those in analogous carborane-based systems. In addition to the NH⋯HB contacts, the CH⋯HB contact was established. As in the case of the glycine complex with [B10H10]2−, the CH⋯HB contact was weaker than the NH⋯HB contacts, and the energy of this contact was equal to 0.8 kcal/mol.

The value of the interaction energy Eint of complex [B10H10]2− with glycine was found to be greater (by modulus) than analogous values for the [B12H12]2− assembly in both the ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations (Table S9). In the case of the ωB97X-D4rev calculation, the difference in values between complexes was equal to 3 kcal/mol, whereas in the case of DLPNO-CCSD(T), this difference was equal to 1.1 kcal/mol. The value of binding energy Ebin was also greater in the case of the [B10H10]2− complex for both computing approaches. In the case of ωB97X-D4rev, the difference was equal to 0.9 kcal/mol, and for DLPNO-CCSD(T), the difference was equal to 0.8 kcal/mol. Despite the negative values of Eint and Ebin, the Gibbs energy (∆G) values for the complexation reactions were positive due to the positive values of entropy (∆S) (Table S9). The ∆G for the [B10H10]2− complex was lower by 1.0 and 1.1 kcal/mol than for the [B12H12]2− complex according to the ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) approaches, respectively. Using the ∆G values, the stability constants of the molecular assemblies were estimated (Table S10). For the [B10H10]2− complex, the stability constant was equal to 3.1 × 10−5 at the DLPNO-CCSD(T) level of theory (4.8 × 10−6 for the DFT calculation). For the [B12H12]2− complex, the stability constant was equal to 4.7 × 10−6 at the DLPNO-CCSD(T) level of theory (8.8 × 10−7 for the DFT calculation).

The ETS-NOCV approach was used to implement the decomposition of bond energy to its main components (Table S11). The overall bonding energy, Eint, between [B10H10]2− and glycine was equal to −11.4 kcal/mol. Electrostatic energy contributed the most to the overall bonding energy. The value of this component was equal to −44.5 kcal/mol, whereas the value of orbital energy was equal to −5.4 kcal/mol. The value of bonding energy between [B12H12]2− and glycine was less than in the case of the analogous complex based on [B10H10]2−. This value was equal to −7.6 kcal/mol. In the case of the [B12H12]2− complex, the contribution of electrostatic energy was more significant than in the system based on [B10H10]2−, and was equal to −59.6 kcal/mol. The value of orbital energy was equal to −3.9 kcal/mol.

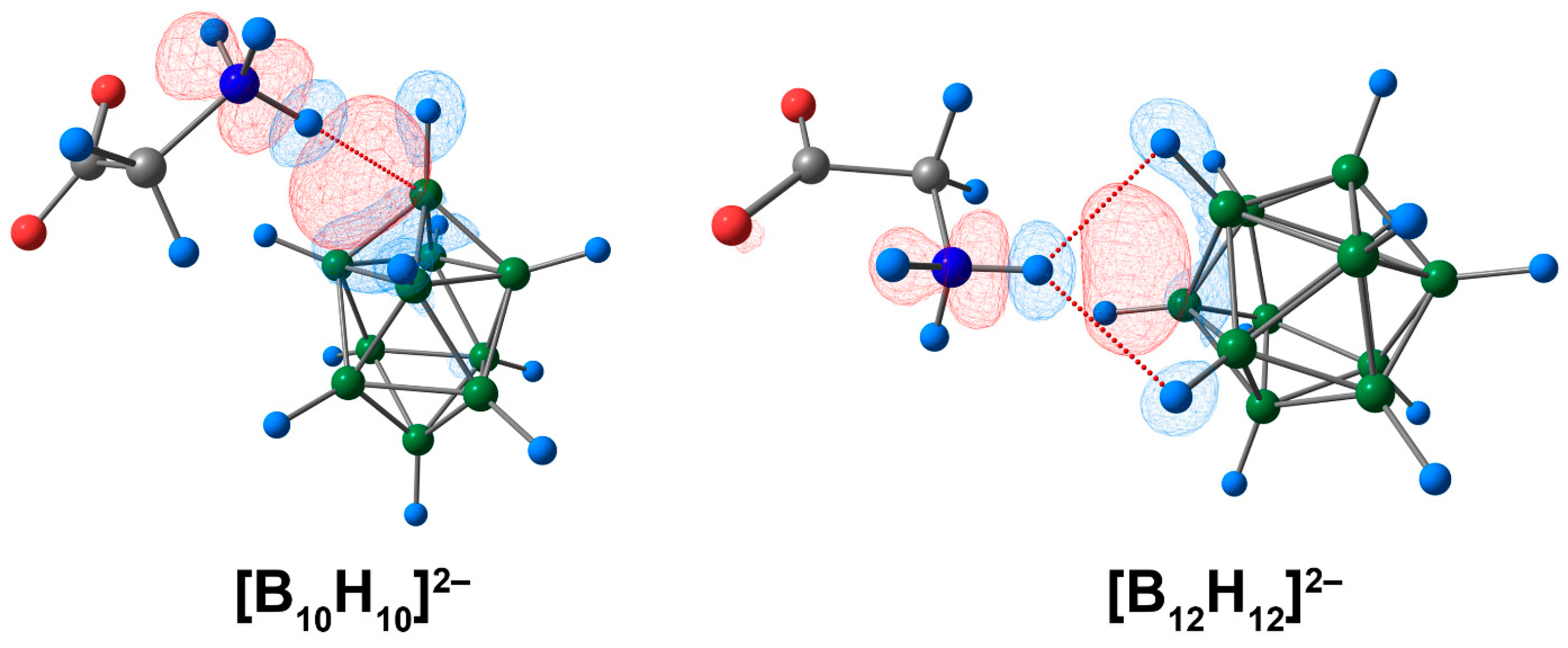

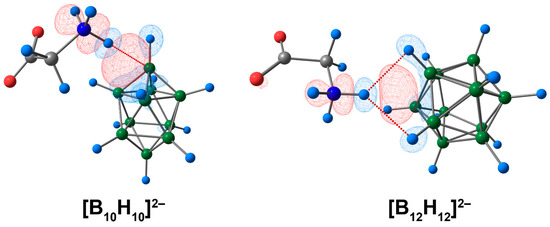

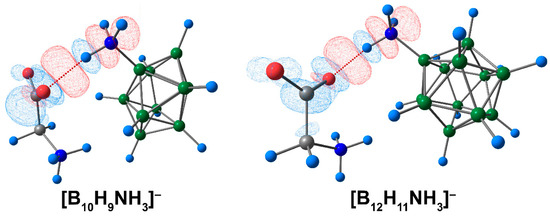

From the graphical representation of deformation density contributions, it can also be concluded that the electron density donor was not a single cluster atom (boron or hydrogen), but a facet containing atoms of boron and hydrogen (Figure 2, indicated with the blue colour). This explains the rather unusual results of the QTAIM analysis, in which the bonding path linked the hydrogen atom of the ammonium group and the boron atom of the cluster. The same conclusion can be drawn for the complex of glycine and the [B12H12]2− cluster.

Figure 2.

The main contribution to the deformation density in molecular complexes of [BnHn]2− anions with glycine. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. Regions of electron density corresponding to donors and acceptors are indicated in blue and red, respectively. Atom labels are shown in Figure 1. The isovalue of the deformation density is 0.0003 e/A3.

Thus, the complex of the [B10H10]2− anion with glycine had a stronger bond between the cluster and amino acid than that of the system based on the [B12H12]2− cluster. This conclusion is based on energy evaluations, QTAIM, and ETS-NOCV analysis. The most precise description of the bonding pattern between cluster anions and glycine was obtained by the ETS-NOCV approach, where the hydrogen atom of the glycine ammonium group was found to interact with the whole facet of the boron cluster.

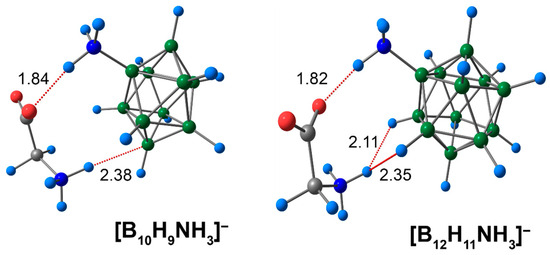

3.2. Complex of [BnHn−1NH3]− Clusters with Glycine

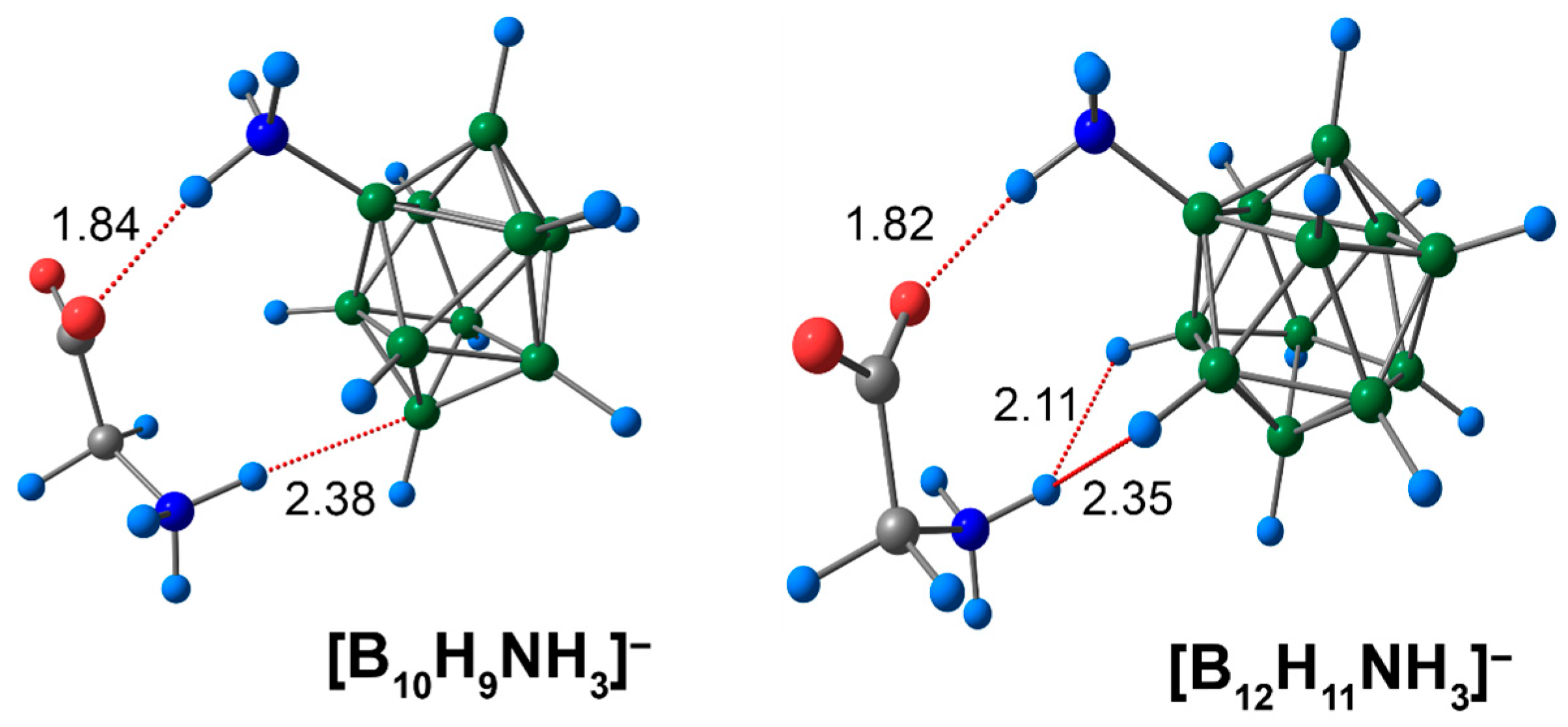

The second type of NCI featured in this study belonged to the complexes of ammonia derivatives [BnHn−1NH3]− (n = 10, 12) with glycine. Positively charged hydrogen atoms of the exo-polyhedral cluster ammonium group formed a short contact with the negatively charged oxygen atom of the carboxyl group of glycine. The length of this contact was equal to 1.84 Å in the case of the [B10H9NH3]− anion, and 1.82 Å in the case of the 12-vertex anion [B12H11NH3]− (Figure 3). In addition to COOgly⋯HNcluster contacts, the hydrogen atoms of the glycine ammonium group formed short interactions with the atoms of the cluster. For [B10H9NH3]−, the NHgly⋯HB length was equal to 2.15 Å, and NHgly⋯B was equal to 2.38 Å. The glycine ammonium hydrogen atom formed two equal NCIs with two exo-polyhedral hydrogen atoms of the unsubstituted closo-dodecaborate anion [B12H12]2−, while in the case of [B12H11NH3]−, one of the NHgly⋯HB contacts was equal to 2.11 Å and another was equal to 2.35 Å.

Figure 3.

Optimised structures of molecular complexes of [BnHn−1NH3]− anions with glycine. Atom labels are shown in Figure 1. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. The lengths of main NCIs are given in Å.

The bonding path between the hydrogen atom of the NH3- group and the apical boron atom of the cluster cage in the glycine complex with [B10H9NH3]− was also inspected. Based on the Espinosa–Lecomte correlation (Equation (1)), the energy of such a contact was equal to 2.4 kcal/mol (Table S2). In the case of the [B12H11NH3]− cluster complex, both the DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) approaches detected two bond paths between the H atom of the glycine NH3-group and two exo-polyhedral hydrogen atoms (Figure S2). These contacts differed not only by their lengths but also by their descriptors of electron density. The energies of the contacts differed by 0.5 kcal/mol using both the ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) approaches.

COOgly⋯HNcluster interactions were stronger than NHgly⋯B ([B10H9NH3]−) and NHgly⋯HB ([B12H11NH3]−) interactions. The values of the main descriptors of electron density ρ(rbcp) of COOgly⋯HNcluster interactions were greater than the analogous values for NHgly⋯B and NHgly⋯HB. According to the Espinosa–Lecomte correlation (Equation (1)), the DFT values of COOgly⋯HNcluster interactions lie in the range of 9.2 to 9.8 kcal/mol (9.5 to 10.1 kcal/mol with the DLPNO-CCSD(T) approach). The interaction within the complex of the [B12H11NH3]− anion COOgly⋯HNcluster had a greater energy value (9.8 kcal/mol for ωB97X-D4rev and 10.1 kcal/mol for DLPNO-CCSD(T)) than the analogous complex of the [B10H9NH3]− anion with glycine. According to Jeffrey’s classification, biologically significant N–H⋯OC hydrogen bonds have energies in the range of 4 to 15 kcal/mol [78]. The values of the COOgly⋯HNcluster contacts obtained in the present work can be attributed to moderate-strength interactions. The energy of weak CH⋯HB and COO⋯HB interactions lies in the range of 0.7 to 1.0 kcal/mol using both the DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) approaches.

The complex based on the closo-decaborate anion [B10H9NH3]− had greater values of Eint than the closo-dodecaborate derivative [B12H11NH3]−, similar to the unsubstituted boron clusters (Table S9). However, the difference between the Eint values of the two complexes was equal to 0.1 kcal/mol, according to the ωB97X-D4rev calculation. The difference was equal to 0.8 kcal/mol when using the DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculation. The difference in energies Ebin was equal to 0.2 kcal/mol in the case of the DFT approach and 1.1 kcal/mol when using DLPNO-CCSD(T). As in the case of molecular complexes based on [BnHn]2−, the ∆G values for complex formation were positive (Table S9). The ∆G of the [B10H9NH3]− complex was lower by 1.3 and 1.2 kcal/mol than for the [B12H11NH3]− complex, according to the ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations, respectively. For the [B10H9NH3]− complex, the stability constant was equal to 3.6 × 10−3 at the DLPNO-CCSD(T) theory level (1.0 × 10−3 for DFT calculation, Table S10). For the [B12H11NH3]− complex, the stability constant was lower by an order of magnitude and equal to 5.0 × 10−4 at the DLPNO-CCSD(T) theory level (1.1 × 10−4 for DFT calculation).

The ETS-NOCV approach revealed that the Eint of the [B10H9NH3]− complex with glycine was 3.8 kcal/mol higher than the Eint of the [B12H11NH3]− complex (Table S11). Electrostatic interaction was predominant for the binding of the boron cluster and glycine in both complexes. The value of this interaction type was higher in the [B10H9NH3]− complex with glycine. An analogous trend was observed for orbital interaction.

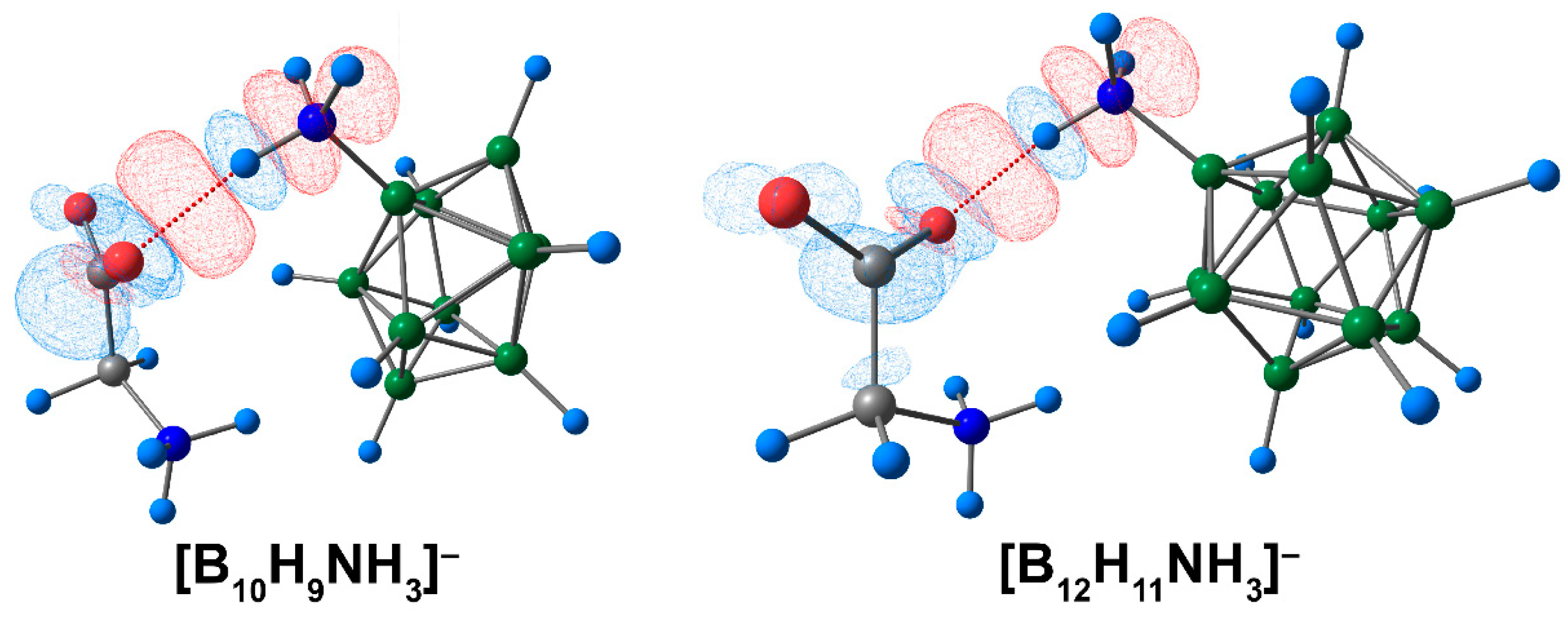

A graphical representation of deformation density contributions demonstrated that the main contribution to the formation of complexes between ammonium derivatives of closo-borate anions and amino acid was provided by the COOgly⋯HNcluster interaction (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The main contribution to the deformation density in molecular complexes of [BnHn−1NH3]− anions with glycine. Atom labels are shown in Figure 1. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. Regions of electron density corresponding to donors and acceptors are indicated in blue and red, respectively. The isovalue of the deformation density is 0.0003 e/A3.

Thus, the findings of the study suggest that glycine and the [B10H9NH3]− anion were bonded more firmly than the complex based on the [B12H11NH3]− anion. The interaction between the oxygen atom of the carbonyl group and the hydrogen atom of the ammonium group contributed the most to the binding between the clusters and the amino acid. In addition, interactions between hydrogen atoms of the NH3- group and the atoms of the cluster cage were shown to make a moderate contribution to the interactions between the clusters and glycine.

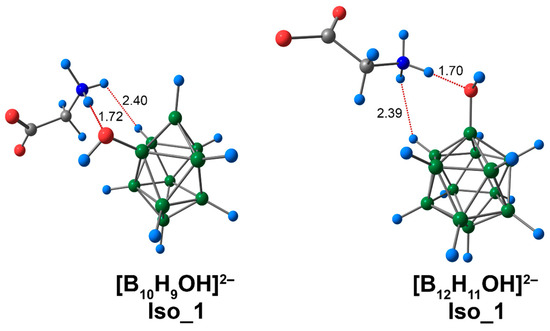

3.3. Complex of [BnHn−1OH]2− Clusters with Glycine

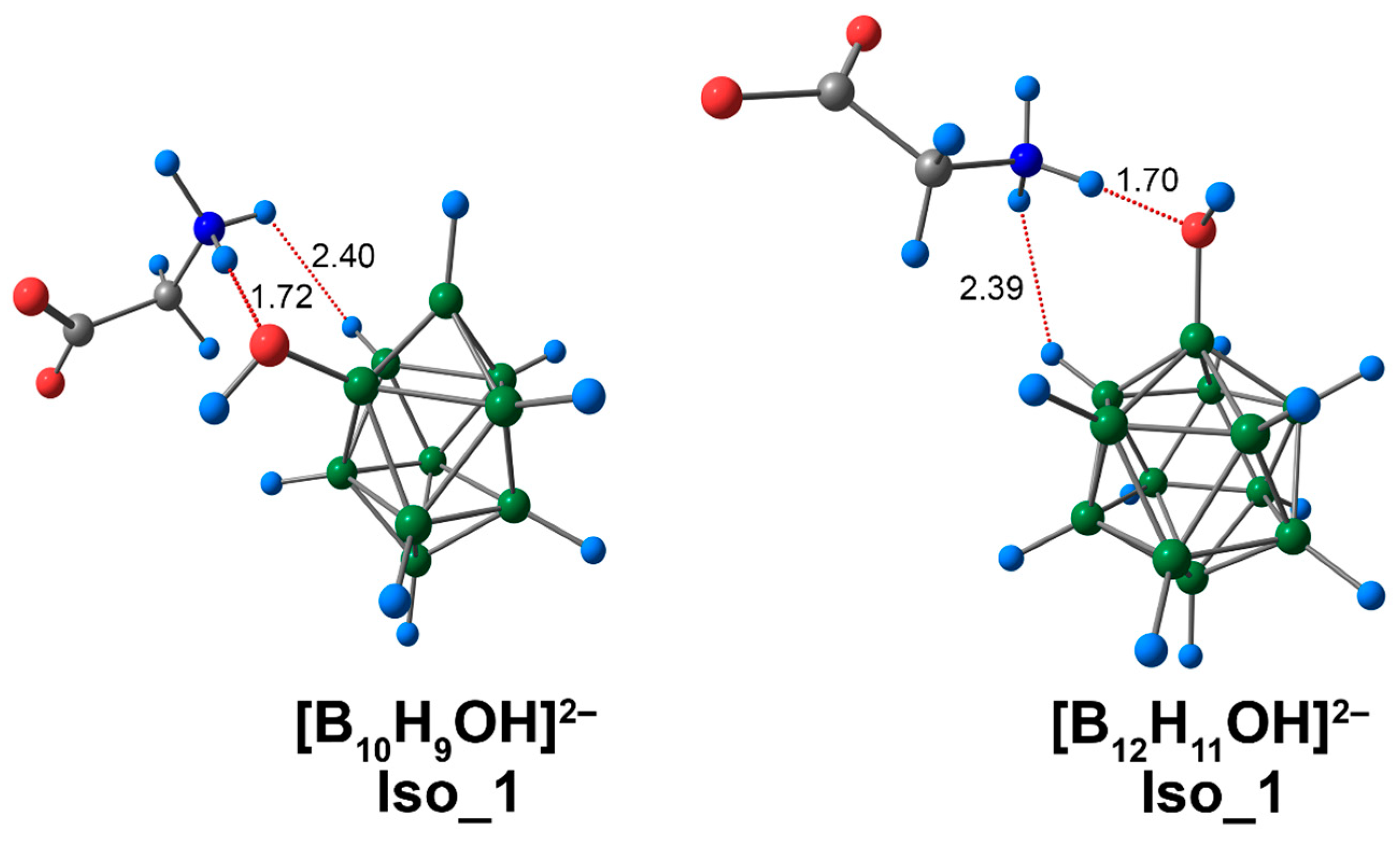

For complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− clusters with glycine, several isomers were localised. These isomers were formed due to the existence of different binding modes between cluster anions and the amino acid. Glycine could bind to the boron cluster by the interaction NH···O between the hydrogen atom of the glycine ammonium group and the oxygen atom of the exo-polyhedral OH-group. A variant on this mechanism was the interaction CO···HO between the oxygen atom of the glycine carboxyl group and the hydrogen of the exo-polyhedral OH-group. Subsequently, the NH···O type of structure will be referred to as Iso_1, while CO···HO structures will be designated as Iso_2, and the third variant, which is based on the presence of both types of interactions (NH···O and CO···HO), will be designated as Iso_3. Iso_1 was most energetically favourable for the complex based on [B10H9OH]2−, although the values of electronic energy of all found isomers vary by less than 1 kcal/mol (0.4 kcal/mol DLPNO-CCSD(T)). Iso_3 was the most energetically stable for the glycine complex with the [B12H11OH]2− anion. As for closo-decaborate derivatives, the values of electronic energy for all considered isomers also differed slightly from each other.

For Iso_1 systems, the lengths of the NH···O interactions were practically identical for both [BnHn−1OH]2− complexes. For the assembly based on the [B10H9OH]2− anion, the value of a given contact was longer, and equal to 1.72 Å. For the closo-dodecaborate anion, the analogous value was equal to 1.70 Å (Figure 5). Also, for Iso_1 systems, the complex of the [B12H11OH]2− anion had greater values for the main descriptors of electron density (by modulus) at the bcp of NH···O interactions (Table S3). For example, the difference in electron density ρ(rbcp) was equal to 0.0019 e/Å3 (0.0018 e/Å3 for DLPNO-CCSD(T)). Based on the Espinosa–Lecomte correlation (Equation (1)), the energy value of the NH···O interaction for the [B12H11OH]2− complex was 0.7 kcal/mol higher than for the [B10H9OH]2− complex. The energies of NH···O contacts obtained at the ωB97X-D4rev theory level lay within the interval of 13.7 to 14.4 kcal/mol (13.9 to 14.9 kcal/mol for DLPNO-CCSD(T)). As mentioned above, the energies of biologically significant N–H⋯OC hydrogen bonds are in the range from 4 to 15 kcal/mol. Thus, the NH···O contacts found in this work can be attributed to strong interactions.

Figure 5.

Optimised structures of Iso_1 molecular complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− anions with glycine. Atom labels are shown in Figure 1. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. The lengths of main NCIs are given in Å.

In addition, another hydrogen atom of the ammonium group formed a contact with the exo-polyhedral hydrogen atom (Figure S3). This contact was observed for both [BnHn−1OH]2− complexes. The lengths of this contact lie in the interval of 2.39 to 2.40 Å. The values of the NH···HB contact energy lie in the interval of 1.0 to 1.1 kcal/mol. The hydrogen atom of the glycine CH2-group also had short contacts with the exo-polyhedral hydrogen atoms. The length of the CH···HB contact was 2.49 Å in the case of [B10H9OH]2−. For the [B12H11OH]2− anion complex, the H atom of the glycine group formed two contacts with cluster atoms. The length of one contact was equal to 2.63 Å, while the other contact was 2.71 Å in length. For the CH···HB interaction, the energy value lay in the interval of 0.6 to 0.8 kcal/mol.

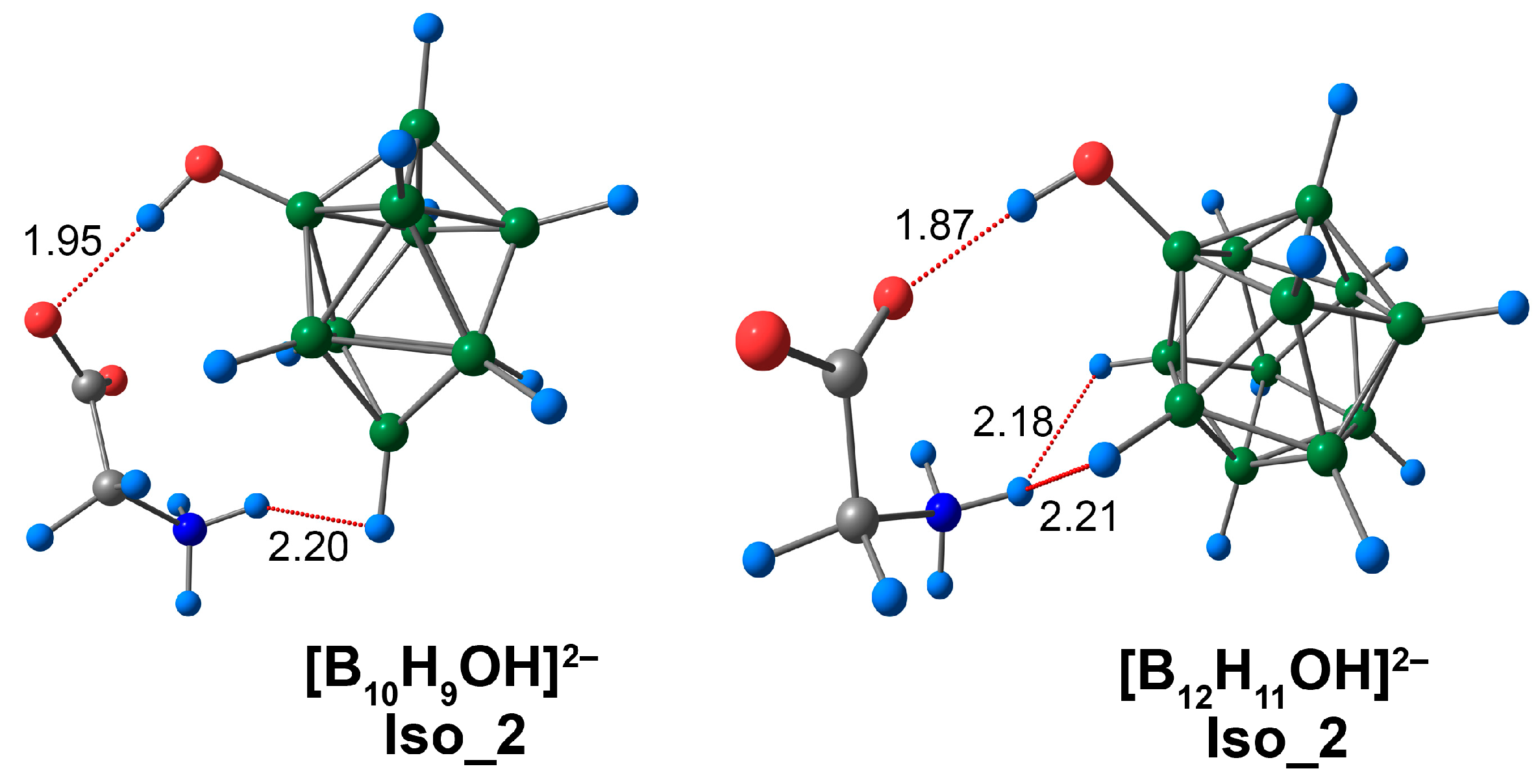

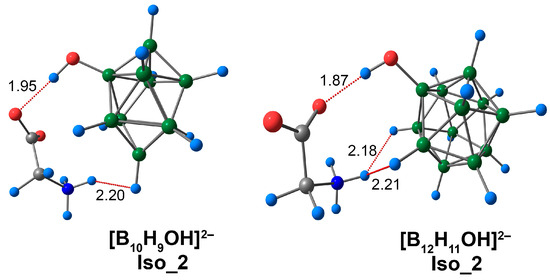

CO···HO interactions in Iso_2 exhibited significant differences between complexes based on closo-decaborate and closo-dodecaborate derivatives. In the case of the [B10H9OH]2− complex, this interaction had a length that was equal to 1.94 Å, whereas for the [B12H11OH]2− anion, the analogous interaction was shorter and equal to 1.87 Å (Figure 6). These contacts had significant differences between the main descriptors of electron density (Table S4). For example, for the complex based on the [B10H9OH]2− anion, the value of the CO···HO interaction ρ(rbcp) was equal to 0.0247 e/Å3 (0.0236 e/Å3 DLPNO-CCSD(T)), whereas the analogous value for the [B12H11OH]2− complex was equal to 0.0296 e/Å3 (0.0282 e/Å3 DLPNO-CCSD(T)). The difference between the energies of such contacts was 1.7 kcal/mol for both ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) cases. The DFT values of the CO···HO contacts lie in the range of 6.6 to 8.4 kcal/mol (6.8 to 8.5 kcal/mol for DLPNO-CCSD(T)). CO···HO contacts were investigated most thoroughly in the case of malonaldehyde and its derivatives. The values of energy for this NCI lie within the interval of 9.7 to 20.6 kcal/mol [79,80]. Thus, the CO···HO interactions in the complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− clusters with glycine were weaker than those in malonaldehyde and its derivatives. However, it is worth noting that the hydrogen bond in malonaldehyde is intramolecular, and this type of NCI is typically stronger than intermolecular ones.

Figure 6.

Optimised structures of Iso_2 molecular complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− anions with glycine. Atom labels are shown in Figure 1. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. The lengths of main NCIs are given in Å.

In addition, the short contacts between the hydrogen atom of the glycine ammonium group and the atoms of the cluster cage were inspected for Iso_2 (Figure S4). In the case of the Iso_2 complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2−, the NH···B contacts were much longer than the analogous contacts for [B10H10]2− and [B10H9NH3]− systems, and lie in the range of 2.62 to 2.70 Å. Thus, for the [B10H9OH]2− complex, short NH···HB contacts between the hydrogen atom of the NH3 group and the two exo-polyhedral hydrogens were observed and confirmed by means of QTAIM analysis. The lengths of this contact lie in the range of 2.20 to 2.21 Å. The energy values of these contacts were 1.5 kcal/mol using the ωB97X-D4rev calculation and 1.6 kcal/mol using the DLPNO-CCSD(T) approach. Similar results were obtained for the complex based on the [B12H11OH]2− anion. The lengths of NH···HB contacts lie in the range of 2.18 to 2.20 Å, while the energy value was 1.5 kcal/mol according to the ωB97X-D4rev calculation (1.6 kcal/mol DLPNO-CCSD(T)), as in the case of the [B10H9OH]2− complex.

For one of the hydrogen atoms of the CH2-group, a CH···HB contact was observed. This type of interaction was established for both types of cluster complexes. The lengths of this contact were equal to 2.23 and 2.48 Å for the [B10H9OH]2− and [B12H11OH]2− complexes, respectively. The energy values lie within the interval of 1.2 to 1.4 kcal/mol. O···HB contacts were also observed, with the energy of such contacts lying in the interval of 0.6 to 1.1 kcal/mol.

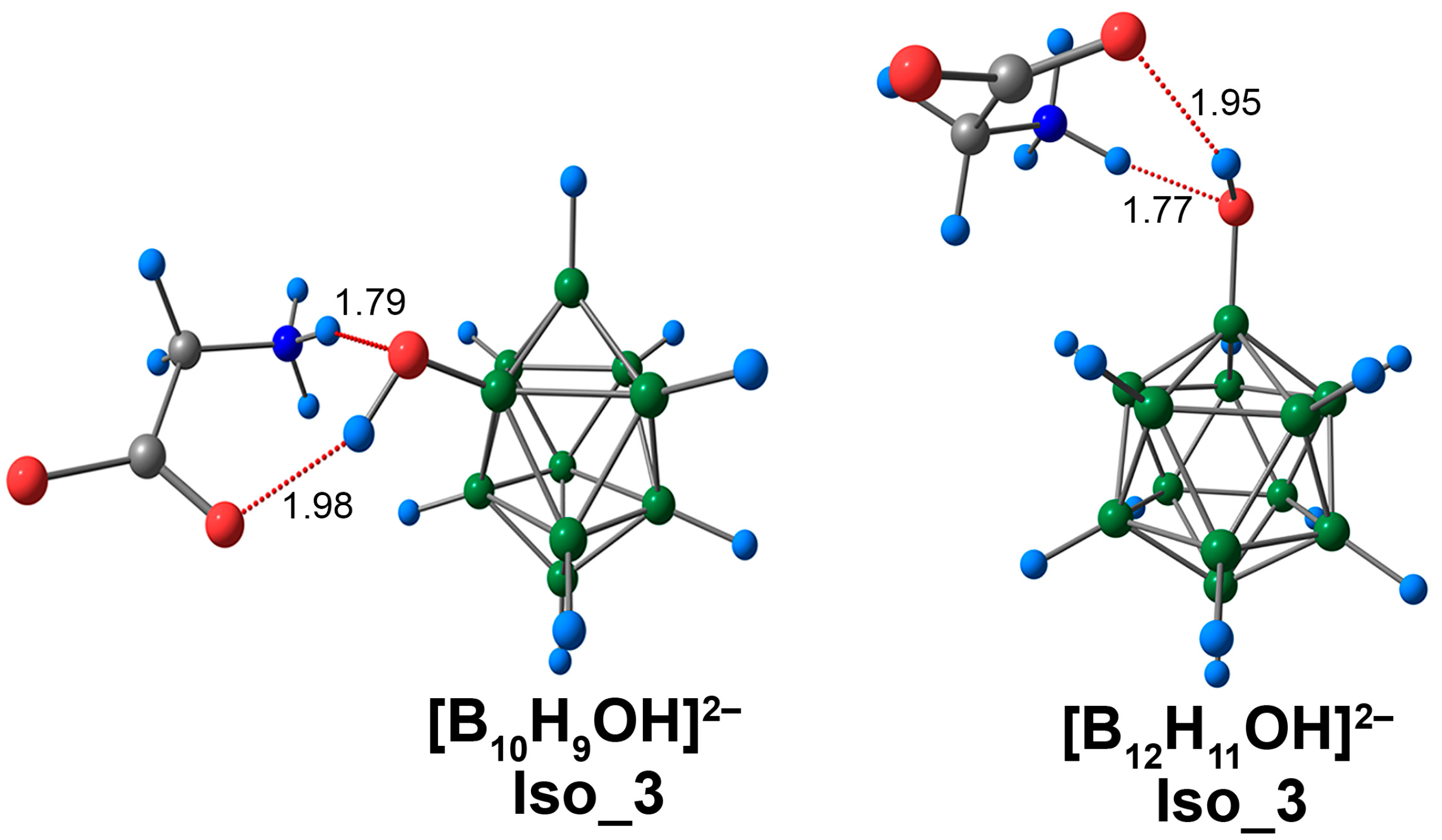

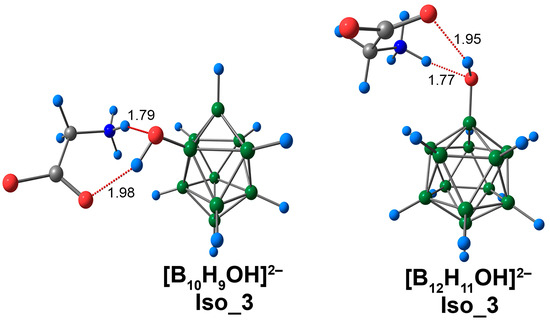

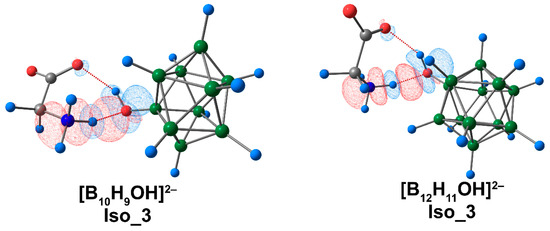

For Iso_3 systems, both NH···O and CO···HO contacts were observed (Figure 7 and Figure S5). These contacts were longer than those in systems containing only one type of interaction (NH···O or CO···HO). NH···O contacts lie in the range of 1.74 to 1.76 Å, while the CO···HO contacts were in the range of 1.94 to 1.98 Å. NH···O contacts had greater values for electron density descriptors than CO···HO contacts. For example, the values of electron density at bcp lie in the range of 0.0399 to 0.0417 e/Å3 and 0.0239 to 0.0257 e/Å3 for NH···O and CO···HO contacts, respectively (Table S5). In both cases, the shortest contacts were observed for the [B12H11OH]2− complex. Also, for the system based on the closo-dodecaborate anion, these contacts had larger values of electron density descriptors. The difference in the values of electron density, ρ(rbcp), corresponding to NH···O interaction, was 0.0018 e/Å3 (0.0017 e/Å3 DLPNO-CCSD(T)). A similar difference in values was obtained for ρ(rbcp), corresponding to CO···HO contact (0.0018 e/Å3 using the DFT approach and 0.0017 e/Å3 using DLPNO-CCSD(T)). The values of energy interaction were also greater in the case of the [B12H11OH]2− complex. The difference was 0.7 kcal/mol with both the ωB97X-D4rev and the DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations. It is noteworthy that the energy values of the NH···O and CO···HO interactions in Iso_3 systems were less than for the analogous contacts in Iso_1 and Iso_2.

Figure 7.

Optimised structures of Iso_3 molecular complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− anions with glycine. Atom labels are shown in Figure 1. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. The lengths of main NCIs are given in Å.

Further analysis revealed additional weak interactions, beyond the NH···O and CO···HO contacts, between the cluster cage of [BnHn−1OH]2− and the amino acid. NH···HB, N···HB, and C···HB interactions were established using QTAIM analysis. The energy of such interactions lay in the range of 0.6 to 1.1 kcal/mol and 0.6 to 1.2 kcal/mol, with ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations, respectively.

For complexes of [B10H9OH]2− with glycine, the highest values of Eint and Ebin were calculated for the Iso_1 system, whereas the Iso_3 system had the lowest values (Table S9). In the case of [B12H11OH]2−, the highest values were obtained for Iso_3 systems, while the lowest values belonged to Iso_2 systems. Iso_1 and Iso_2 system complexes based on [B10H9OH]2− had greater values of Eint and Ebin than [B12H11OH]2− systems. The highest values of Eint and Ebin were equal for the Iso_1 complex of the [B10H9OH]2− anion and the Iso_3 complex of [B12H11OH]2−, according to the DFT approach. The DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculation produced the highest values of Eint and Ebin for the Iso_3 complex of [B12H11OH]2− only.

The values of ∆G for complex formation were positive (Table S9). For the complexes of [B10H9OH]2− with glycine, the lowest positive value of ∆G was observed for the Iso_1 system at both the ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) theory levels. For Iso_1 molecular complexes, the stability constant was equal to 2.0 × 10−4 (ωB97X-D4rev) and 3.1 × 10−4 (DLPNO-CCSD(T), Table S10). In the case of [B12H11OH]2− complexes, the lowest positive value of ∆G was observed for Iso_3 and Iso_2 complexes at the DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) theory levels, respectively.

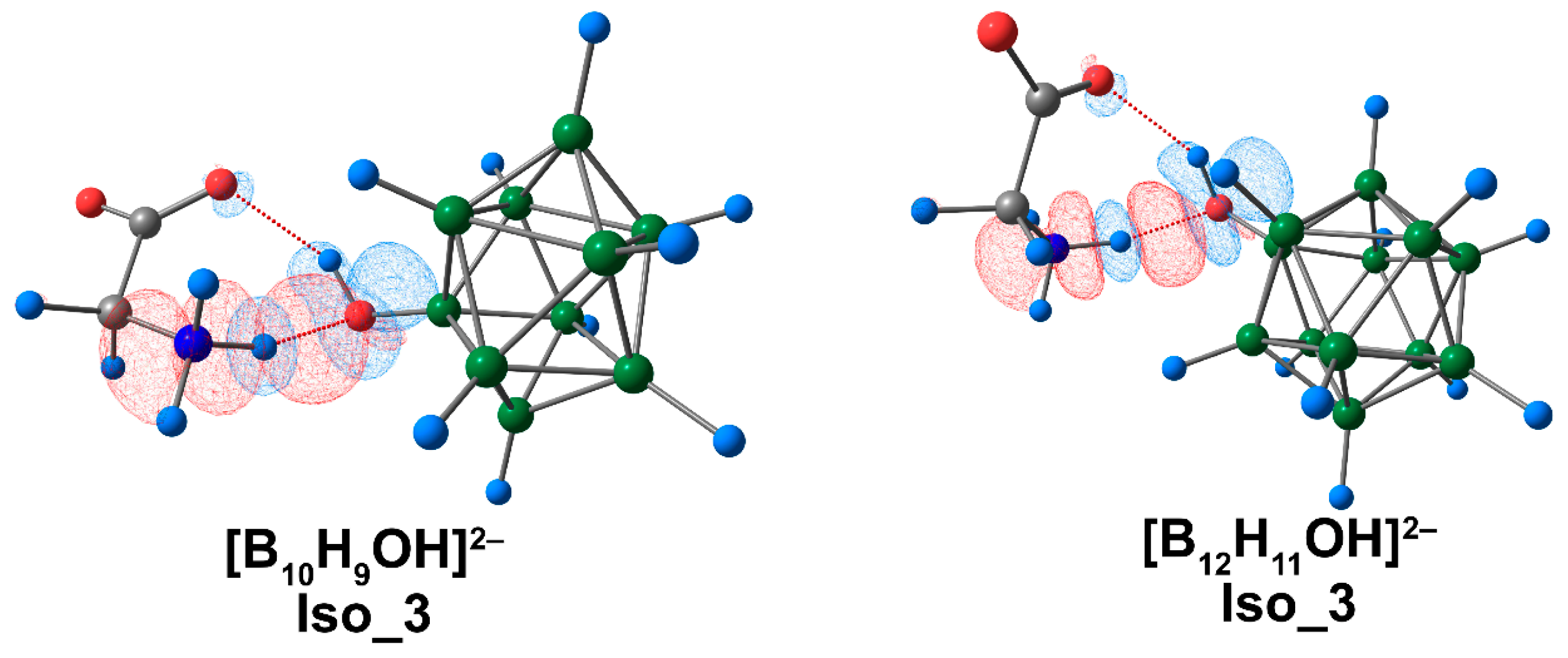

The calculated values of Eint and Ebin showed good agreement with the data obtained using the ETS-NOCV approach (Table S11). The highest value of total energy corresponded to the interaction of glycine complexes with [B10H9OH]2− in the Iso_1 system and for the [B12H11OH]2− complex in the Iso_3 system. The main contribution to binding between the clusters and amino acid was attributed to electrostatic energy, as it was for [BnHn]2− and [BnHn−1NH3]− complexes. Orbital interaction had much less impact on binding between the cluster systems and glycine. The graphical representation of deformation density contributions was most informative in the case of Iso_3 systems, indicating that NH···O contacts provided the greatest contribution to binding between the boron cluster and glycine (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The main contribution to the deformation density in Iso_3 molecular complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− anions with glycine. Atom labels are shown in Figure 1. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. Regions of electron density corresponding to donors and acceptors are indicated in blue and red, respectively. The isovalue of the deformation density is 0.0003 e/A3.

Therefore, three possible types of binding were determined for the complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− with glycine. The most energetically favourable system for [B10H9OH]2− was the complex with an NH···O interaction, whereas for [B12H11OH]2−, it was the complex stabilised by both NH···O and CO···HO contacts. Furthermore, NH···O contacts facilitated stronger binding between the cluster anion and the amino acid than CO···HO interactions.

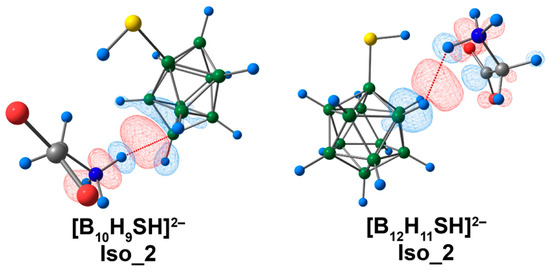

3.4. Complex of [BnHn−1SH]2− Clusters with Glycine

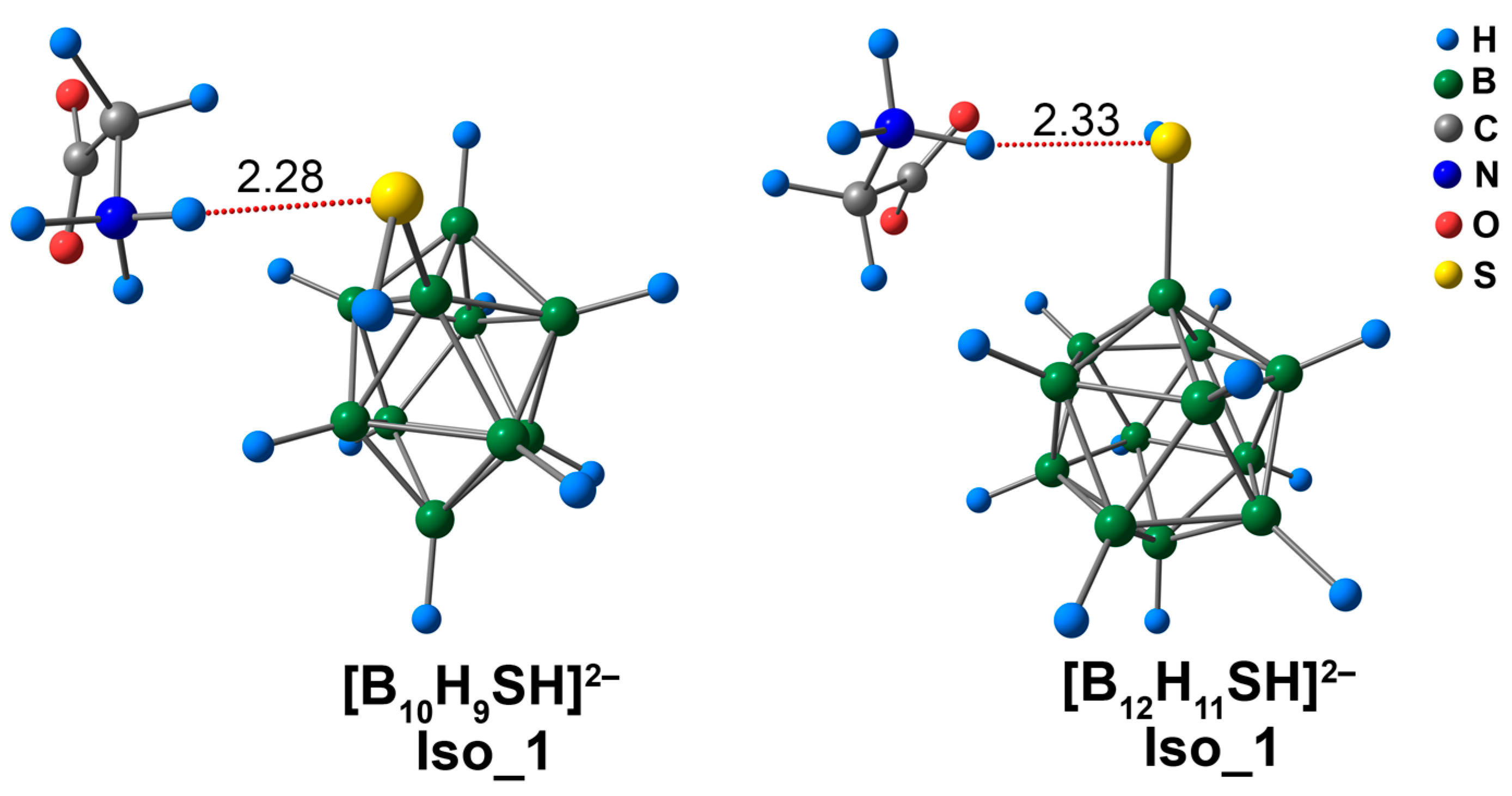

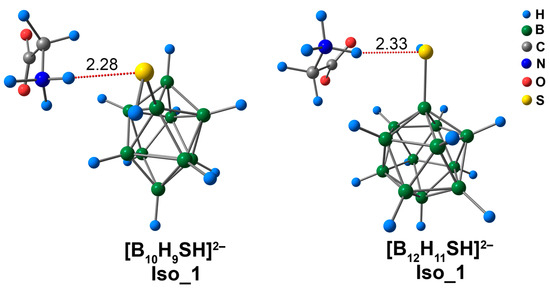

Several main types of coordination were possible for the [BnHn−1SH]2− glycine complexes, which were similar to their [BnHn−1OH]2− analogues. Glycine could be bound to the cluster derivative by the NH···S interaction or the CO···HS contact. The isomer (Iso_1) in the presence of the NH···S contact was slightly more energetically favourable than the isomer (Iso_2) with a CO···HS contact for the derivative [B10H9SH]2−. The difference between the values of total electronic energy was 0.3 kcal/mol according to the DFT approach and only 0.02 kcal/mol when using the DLPNO-CCSD(T) approach. The energy difference between isomers was more significant and was equal to 2.3 kcal/mol (ωB97X-D4rev) and 1.9 kcal/mol (DLPNO-CCSD(T)) for the complexes of derivative [B12H11SH]2−.

The glycine complex of [B10H9SH]2− had a shorter bond length than the [B12H11SH]2− analogues (2.28 Å vs. 2.33 Å) in the case of Iso_1 systems (Figure 9). The values of the main electronic descriptors of NH···S bcp for the [B10H9SH]2− complex were higher than the analogous values for the [B12H11SH]2− complex (Table S6). The difference between the values of electron density was equal to 0.0027 e/Å3 (ωB97X-D4rev) and 0.0025 e/Å3 (DLPNO-CCSD(T)). The difference between the interaction energies was 0.7 kcal/mol, according to the both DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations. It is worth noting that the NH···S interactions were much weaker than the NH···O interactions in [BnHn−1OH]2− complexes. The values of NH···S contact energy lay in the range of 4.5 to 5.2 kcal/mol (ωB97X-D4rev) and 4.7 to 5.4 kcal/mol (DLPNO-CCSD(T)), while the values of NH···O contact energy lay in the range of 13.7 to 14.4 kcal/mol (ωB97X-D4rev) and 13.9 to 14.6 kcal/mol (DLPNO-CCSD(T)). According to the literature, the S-mediated NCIs have energy values in the range of −4.5 to −5.5 kcal/mol [81]. Therefore, the data obtained in the present work was in good agreement with previously published data. In addition to NH···S contacts, some weak NH···HB, N···HB, O···HB, and C···HB interactions were examined (Figure S6). The energy of these contacts lay in the range of 0.6 to 1.1 kcal/mol (ωB97X-D4rev) and 0.6 to 1.2 kcal/mol (DLPNO-CCSD(T)).

Figure 9.

Optimised structures of Iso_1 molecular complexes of [BnHn−1SH]2− anions with glycine. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. The lengths of main NCIs are given in Å.

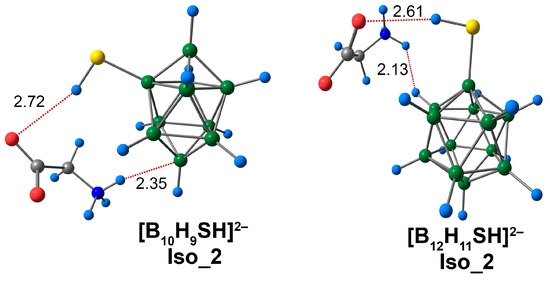

Iso_2 systems were formed due to non-covalent contact between the oxygen atom of the carboxyl group of glycine and the hydrogen atom of the cluster exo-polyhedral substituent (Figure 10). It is worth noting that CO···HS contacts of Iso_2 systems were much longer than the NH···S interactions of Iso_1 systems. For the [B12H11SH]2− system, the length of the O···HS contacts was the shortest, and equal to 2.61 Å. The length of this contact was 0.11 Å longer for the [B10H9SH]2− complex. The energy values of this contact were significantly lower than the O···HO contacts of Iso-2 systems of [BnHn−1OH]2− anions (Table S7). For the complex of [B12H11SH]2−, the energy value was equal to 1.1 kcal/mol (ωB97X-D4rev) and 1.2 kcal/mol (DLPNO-CCSD(T)). For the [B10H9SH]2− complex, this value was equal to 0.9 kcal/mol (ωB97X-D4rev) and 1.0 kcal/mol (DLPNO-CCSD(T)). Thus, the CO···HS interactions in the complexes of [BnHn−1SH]2− clusters with glycine can be attributed to weak hydrogen bonds. Using QTAIM analysis, the NH···B contact was established for the complex of derivative [B10H9SH]2− (Figure S7). The length of this contact was 2.34 Å, and the energy value was 2.6 kcal/mol. In the case of the [B12H11SH]2− anion, the hydrogen atom of the ammonium group formed a contact with the hydrogen atom of the cluster cage. The length of this contact was 2.13 Å. The energy value of the given interaction was less than that for the NH···B contact of the [B10H9SH]2− complex with glycine. This value was equal to 1.2 kcal/mol (ωB97X-D4rev) and 1.3 kcal/mol (DLPNO-CCSD(T)). Weak non-covalent interactions of the types NH···HB, O···HB, and C···HB were observed in the Iso_3 systems. Their calculated energies ranged from 0.7 to 1.1 kcal/mol (ωB97X-D4rev) and from 0.6 to 1.2 kcal/mol (DLPNO-CCSD(T)).

Figure 10.

Optimised structures of Iso_2 molecular complexes of [BnHn−1SH]2− anions with glycine. Atom labels are shown in Figure 9. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. The lengths of main NCIs are given in Å.

For non-covalent complexes of [BnHn−1SH]2− with glycine, several trends in Eint and Ebin were revealed. First, these values were less (by modulus) than the analogous values for [BnHn−1OH]2− systems (Table S9). This observation held for both DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculation approaches and is in good agreement with the fact that the NH···S and CO···HS contacts were weaker than the NH···O and CO···HO interactions. The Iso_1 system had higher values (by modulus) of Eint and Ebin than the Iso_2 system for the [B12H11SH]2− complex, and this was found with both the ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations. In the case of [B10H9SH]2−, this was established only when using the DFT results, whereas higher values between Eint and Ebin were identified for Iso_2 according to DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations. However, the difference between the values was only 0.1 kcal/mol. Complexes based on the [B10H9SH]2− anion had higher values of Eint than analogous systems of the [B12H11SH]2− anion. For Ebin, the Iso_1 isomer of the [B12H11SH]2− complex had a higher value than that of the [B10H9SH]2− system.

The ∆G values for complex formation were positive (Table S9). For the complexes based on [B10H9SH]2−, the Iso_2 isomer had the lowest values of ∆G energies at both the ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) theory levels. The [B12H11SH]2− systems had an opposite trend, and Iso_1 was more thermodynamically stable than Iso_2. The [B12H11SH]2− complexes had lower values of ∆G than the [B10H9SH]2− ones.

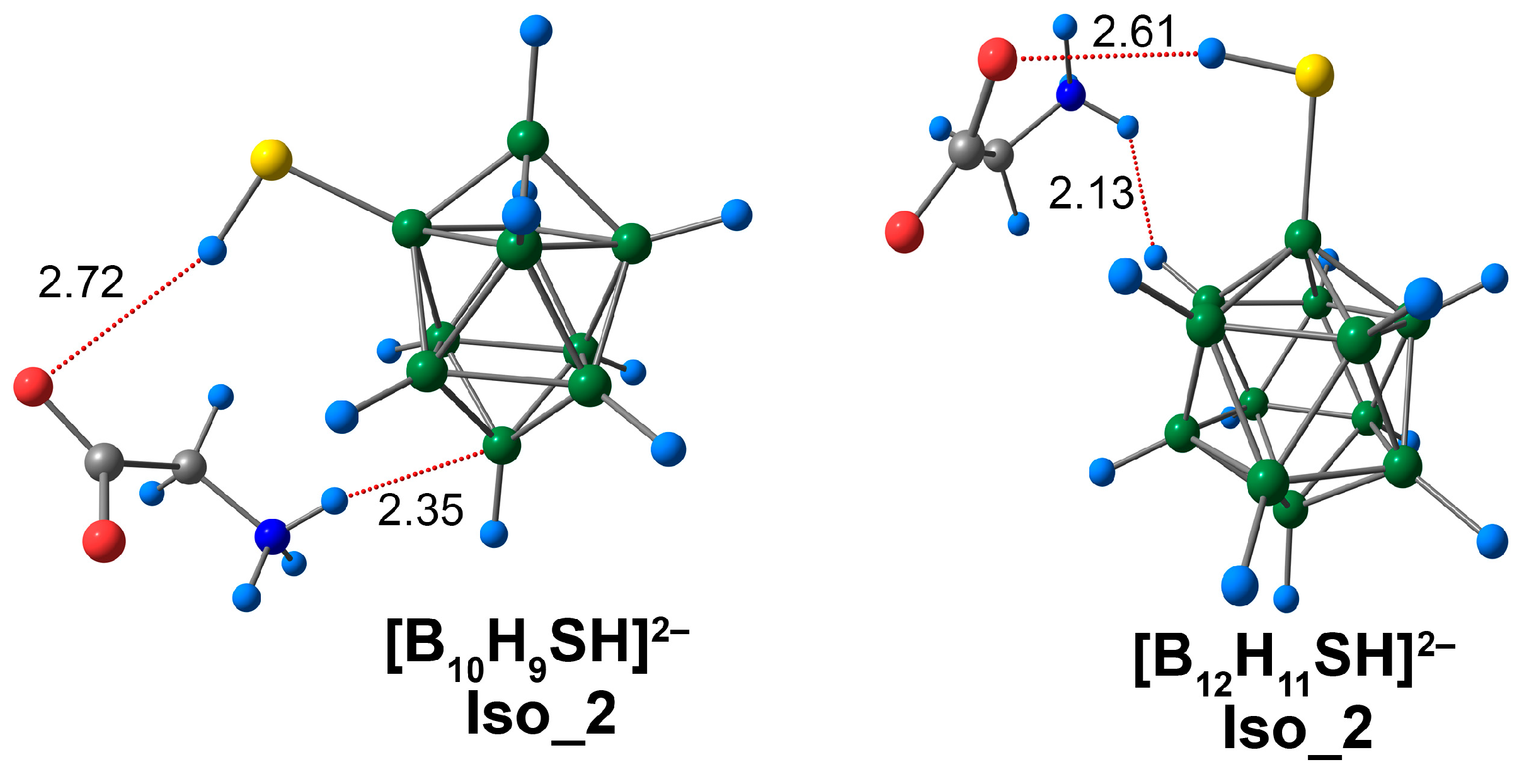

For the systems described previously, electrostatic interactions provided the main contribution to binding between the clusters and amino acids, according to ETS-NOCV data (Table S11). The highest values of electrostatic and orbital interaction energies were revealed for the complex of [B10H9SH]2−. It is noteworthy that the [B12H11SH]2− complex was the only system where the dispersion interaction energy exceeded the orbital interaction energy. For Iso_2 systems, the main contribution to binding between clusters and glycine was attributed to the interaction between the hydrogen atom of the ammonium group and atoms of the cluster cage, according to the graphical representation (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The main contribution to the deformation density in Iso_2 molecular complexes of [BnHn−1SH]2− anions with glycine. Atom labels are shown in Figure 9. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. Regions of electron density corresponding to donors and acceptors are indicated in blue and red, respectively. The isovalue of the deformation density is 0.0003 e/Å3.

Thus, based on thermodynamic data, QTAIM, and ETS-NOCV analysis, the NH···S contacts between cluster derivatives [BnHn−1SH]2− and glycine promoted stronger binding than O···HS contacts. Moreover, NH···HB or NH···B contacts significantly contributed to the association between the cluster and the amino acid for Iso_2 complexes. [B10H9SH]2− formed a more stable complex with glycine than [B12H11SH]2−.

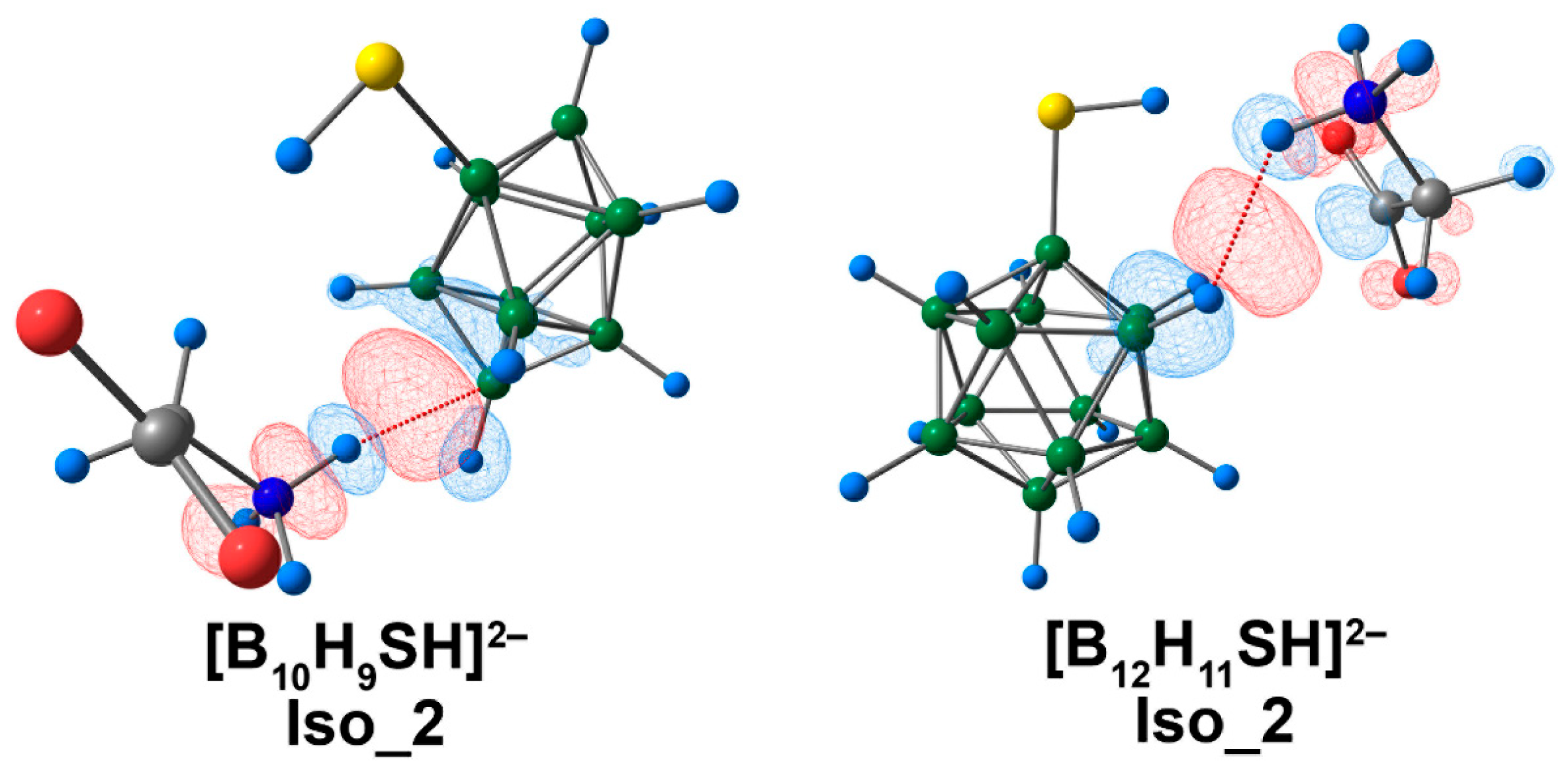

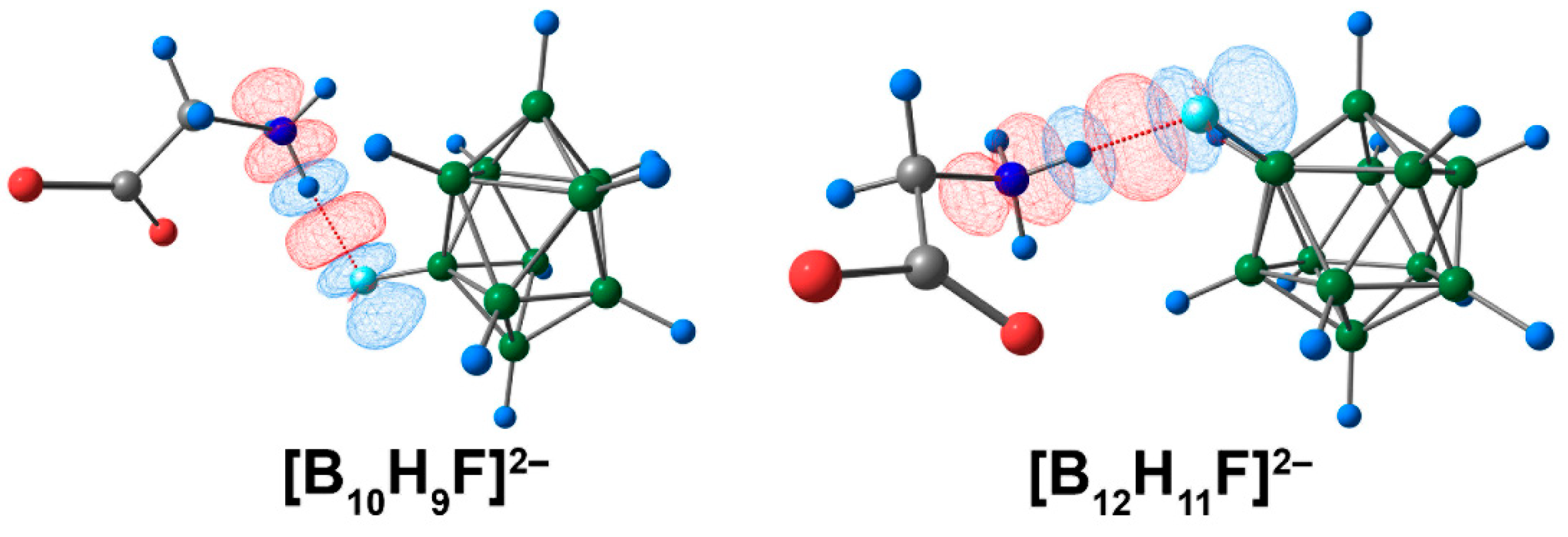

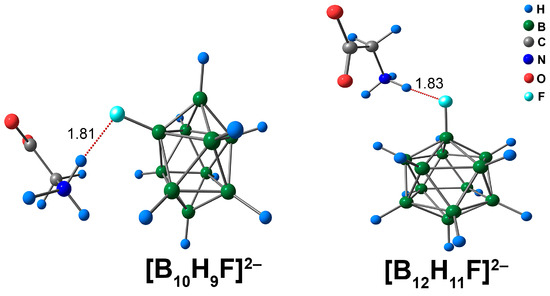

3.5. Complex with [BnHn−1F]2− Clusters with Glycine

The interaction between [BnHn−1F]2− derivatives and glycine occurred through NH···F contacts. Since these complexes with glycine exhibited only one binding mode, a single isomer for each type of cluster ([B10H9F]2− and [B12H11F]2−) was considered (Figure 12). The lengths of NH···F contacts were almost equal for closo-decaborate and closo-dodecaborate fluorine derivatives and lay in the range of 1.82 to 1.83 Å. QTAIM analysis revealed that the main electron density descriptors at the bcp of the NH···F contact had larger magnitudes in the [B10H9F]2− complex than in the [B12H11F]2− analogue (Table S8). For example, the difference in the value of ρ(rbcp) was 0.0014 e/Å3 (ωB97X-D4rev) and 0.0012 e/Å3 (DLPNO-CCSD(T)). The energies of the NH···F interactions were quite high, lying in the range of 8.4 to 9.0 kcal/mol (ωB97X-D4rev) and 8.5 to 9.0 kcal/mol (DLPNO-CCSD(T)). The energy of the NH···F contact was 0.5 kcal/mol higher for the [B10H9F]2− anion than for the [B12H11F]2− system. The literature data indicated that the energy values for X–H···F interactions span a wide range, from 0.3 to 11.5 kcal/mol [82,83,84]. Thus, according to the reported data, the NH···F contacts in the complexes of [BnHn−1F]2− clusters with glycine can be attributed to strong interactions. In addition, some weak CH···HB, O···HB, and N···HB interactions were examined (Figure S8). The energy of such contacts lay in the range of 0.4 to 0.9 kcal/mol, with both DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations.

Figure 12.

Optimised structures of molecular complexes of [BnHn−1F]2− anions with glycine. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. The lengths of main NCIs are given in Å.

The values of Eint and Ebin of the closo-decaborate derivative [B10H9F]2− were higher than in the case of the closo-dodecaborate derivative [B12H11F]2−. The difference between the Eint and Ebin values of [B10H9F]2− and [B12H11F]2− complexes was in the range of 1.1 to 1.5 kcal/mol, using both ωB97X-D4rev and DLPNO-CCSD(T) levels of theory (Table S9). The [B10H9F]2− complex had a lower positive value of ∆G than the [B12H11F]2− analogue according to both DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) approaches (Table S9). For the [B10H9F]2− complex, the stability constant was equal to 1.2 × 10−5 at the DLPNO-CCSD(T) theory level (4.8 × 10−6 for the DFT calculation, Table S10).

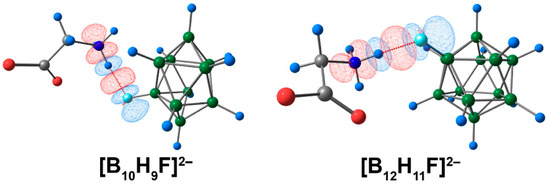

Based on the ETS-NOCV approach, the value of Eint of the [B10H9F]2− complex was higher than in the case of the [B12H11F]2− anion analogue (Table S11). The difference was 4.3 kcal/mol. The [B10H9F]2− complex also exhibited higher orbital and electrostatic interaction energies (by absolute value). The graphical representation of deformation density contributions proved that the main contribution to binding between the cluster anion and glycine was provided by NH···F contact (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

The main contribution to the deformation density in molecular complexes of [BnHn−1F]2− anions with glycine. Atom labels are shown in Figure 10. The main NCIs are denoted with red dotted lines. Regions of electron density corresponding to donors and acceptors are indicated in blue and red, respectively. The isovalue of the deformation density is 0.0003 e/A3.

Thus, the combined thermodynamic, QTAIM, and ETS-NOCV data suggested that the [B10H9F]2− anion formed complexes bound with glycine that were stronger than those of the [B12H11F]2− system.

3.6. General Trends

General patterns within the non-covalent interactions between glycine and closo-borate anions and their derivatives [BnHn−1X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2) were analysed. NH···B and NH···HB contacts played a crucial role in the binding between the cluster anion and glycine for unsubstituted [BnHn]2− systems. XH···HB contacts (X = C, N, O) are well-known types of contact, according to the literature [23,24,48,49], whereas NH···B contacts have not been mentioned previously. However, based on ETS-NOCV data, these contacts could be attributed to multicentre interactions between the hydrogen atom of the NH3 group and atoms of the boron cage facet. For [BnHn−1SH]2− based complexes (Iso_2 systems), these contacts also contributed the most to binding between cluster and amino acid species. These interactions were stronger for closo-decaborate systems than for closo-dodecaborate systems. When compared with the literature data, OH···HB interactions had a similar range of energy values (1.8 to 4.4 kcal/mol) [29]. However, the strongest OH···HB contacts had higher energy values than NH···B and NH···HB contacts.

For the substituted derivatives [BnHn−1X]y− (X = SH, NH3, OH, F; y = 1, 2), NH···X (X = O, S, F), and CO···HX (X = N, O, S), contacts had a significant impact on binding between the cluster fragment and glycine. These contacts had higher energy values than NH···B and NH···HB contacts. Most of these contacts could be attributed to moderate or strong interactions compared with analogous types of interactions in organic and biological systems [78,81]. NH···X contacts were stronger than CO···HX (X = N, O, S) contacts. In general, NHgly···Xcluster and COgly···HXcluster interactions exhibited greater strength in closo-dodecaborate derivatives than in closo-decaborate analogues. The NH···O interaction for the [B12H11OH]2− Iso_1 complex had the highest energy value (14.4 kcal/mol DT and 14.6 kcal/mol DLPNO-CCSD(T)) among all the non-covalent contacts described.

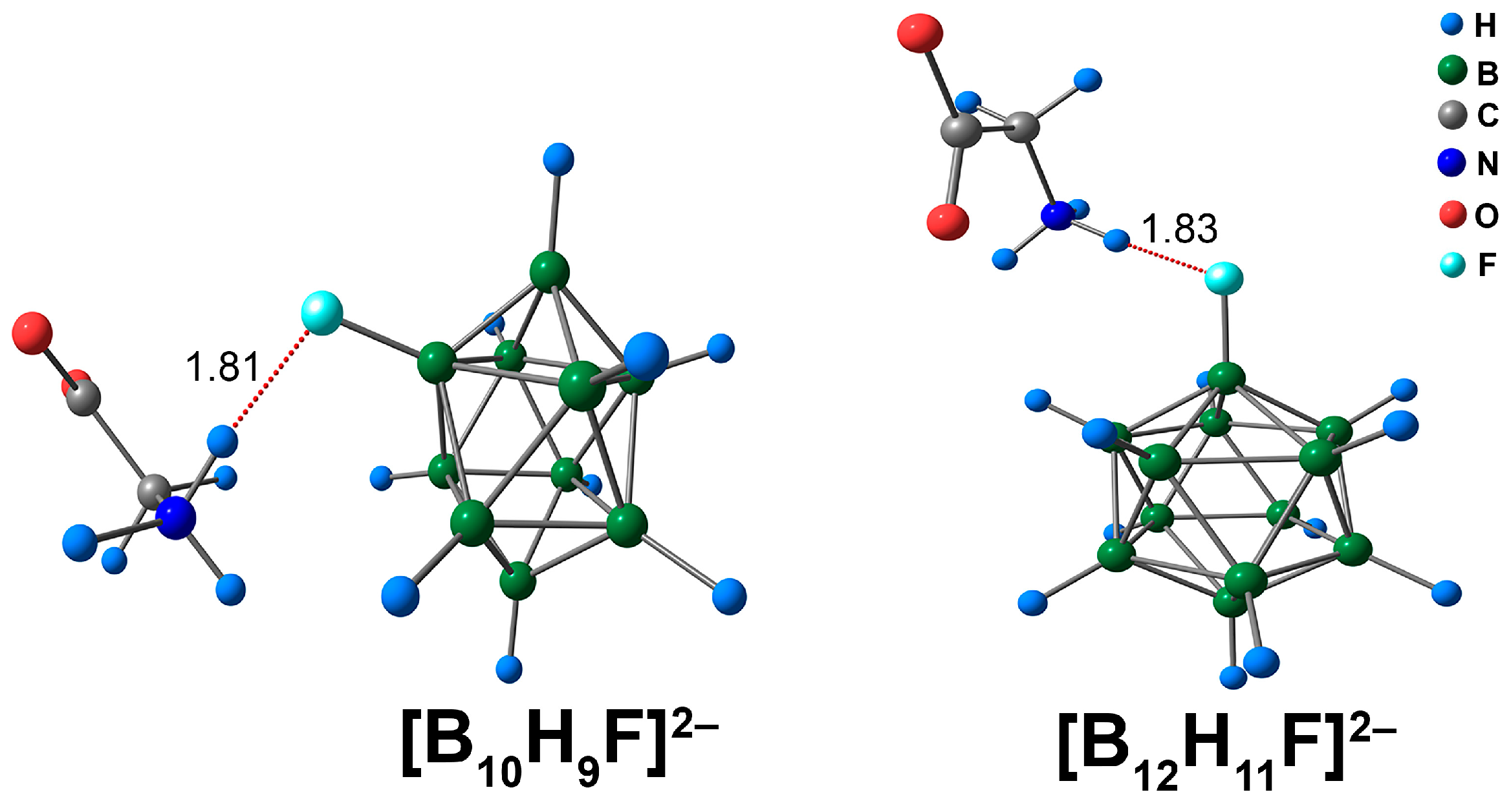

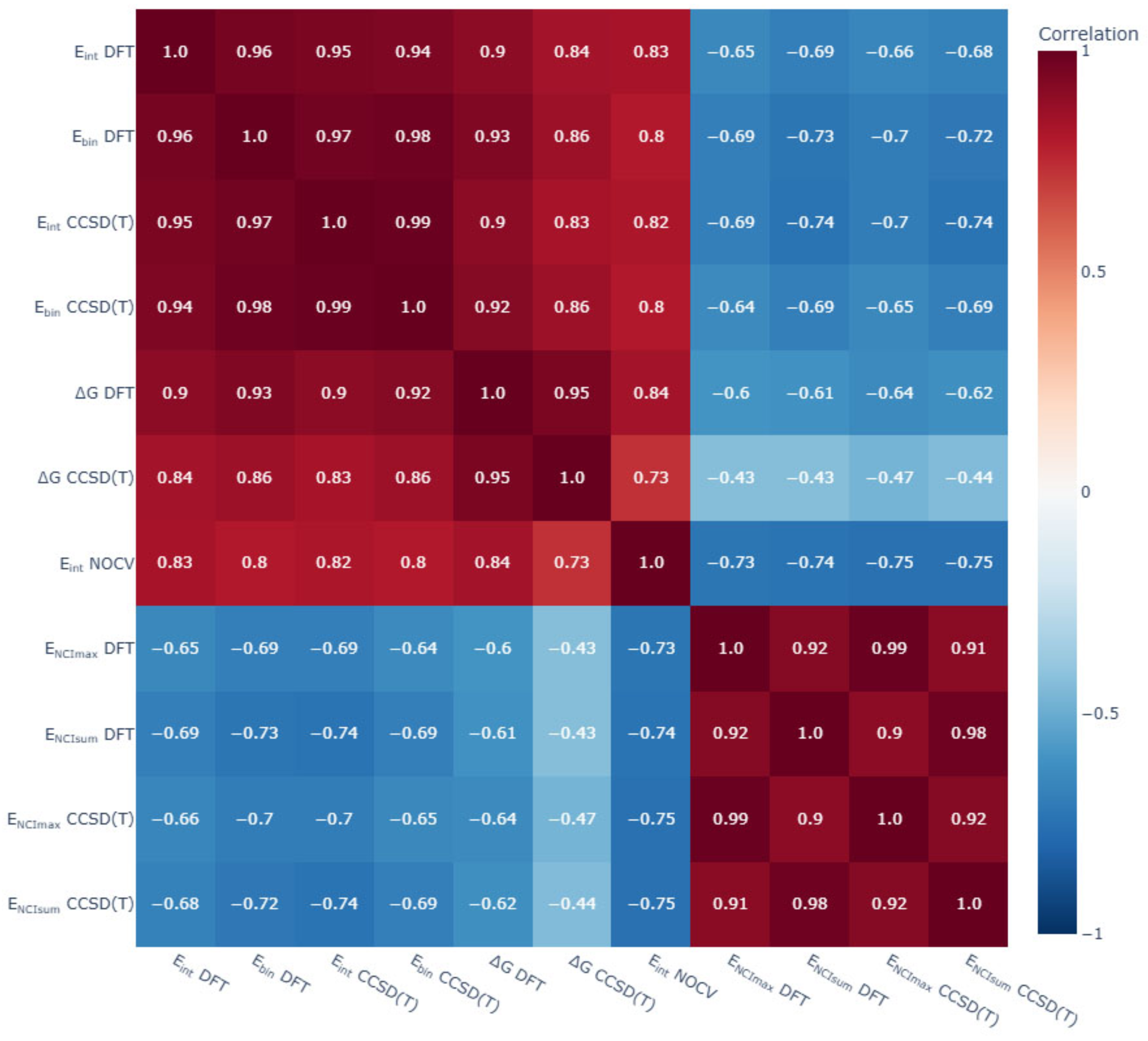

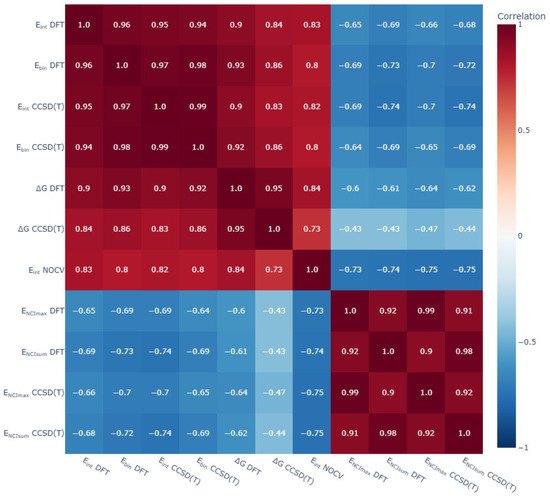

General trends of the energy aspects of [BnHn−1X]y− complexes with glycine were analysed. First, a good agreement between the DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations of Eint and Ebin was found. In addition, the values of Eint obtained using the ETS-NOCV scheme strongly correlated with the DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations of Eint and Ebin (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Matrix correlation of main energetic parameters of non-covalent complexes of [BnHn−1X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2) with glycine. Eint—interaction energy calculated with DFT and CCSD(T) approaches, kcal/mol; Ebin—binding energy calculated with DFT and CCSD(T) approaches, kcal/mol; ∆G—Gibbs energy of complex formation calculated with DFT and CCSD(T) approaches, kcal/mol; ENCI_max—the energy value of the strongest NCI calculated with DFT and CCSD(T) approaches, kcal/mol; ENCI_sum—the sum of all energy values of NCIs for given complex calculated with DFT and CCSD(T) approaches, kcal/mol.

The correlation between the energy of non-covalent interactions and the overall Eint and Ebin values was not so clear and not so strong. A correlation analysis was carried out on the values of the strongest interactions and the total sum of the energy values of NCI. The highest correlation coefficients with NCI descriptors were obtained for the total sum of the NCI energy values. Eint and Ebin were higher for complexes of closo-decaborate anion and its derivatives [B10H9X]y−, whereas the energies of most valuable non-covalent interactions were higher for complexes of the closo-dodecaborate anion and its derivatives [B12H11X]y−. The reason for this discrepancy was found in the analysis of the ETS-NOCV data. The calculated values for Pauli repulsion and solvation energy were more positive for closo-dodecaborate complexes, and these positive contributions counteracted the strong attraction of these complexes.

The attachment of –SH and –F substituents to the closo-borate cage encouraged the energy values of Eint and Ebin to exceed those of the unsubstituted clusters. However, the increase in Eint and Ebin was less pronounced than that of the complex with –NH3 and –OH substituted cluster derivatives. The [B10H9NH3]− complex exhibited the highest Eint and Ebin values among all systems described.

Despite the negative values of Eint and Ebin, all studied complexes had positive ∆G values. This was due to a large unfavourable entropy change (–T∆S), which outweighed the favourable enthalpy change. However, a lot of molecular complexes have positive values of ∆G, and these systems have been actively studied both theoretically and experimentally [85,86,87,88,89,90,91]. The ∆G values obtained using both the DFT and DLPNO-CCSD(T) approaches had good correlation with Eint and Ebin. The correlation coefficients lie in the range of 0.83 to 0.95. The systems based on the derivatives of the closo-decaborate anion had lower ∆G values than the assemblies of the closo-dodecaborate anion, and, consequently, higher stability constants. The assemblies of the hydroxy and ammonium derivatives had lower ∆G values when compared with other derivatives and the unsubstituted closo-borates. The complex of ammonium derivative [B10H9NH3]− had the lowest ∆G value and the highest stability constant (3.6 × 10−3 according to DLPNO-CCSD(T) approach). The obtained value indicates that a noticeable amount of the complex between closo-decaborate anions [BnHn−1NH3]− and glycine exists in its intact form and can be detected by experimental methods.

4. Conclusions

The non-covalent complexes between glycine and closo-borate anions and their derivatives [BnHn−1X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2) were investigated using several approaches. First of all, rather unusual NH···B contacts were observed for complexes based on closo-decaborate derivatives. The introduction of an exo-polyhedral substituent to the closo-borate cluster cage promoted stronger binding with glycine than was seen with unsubstituted closo-borate anions [BnHn]2−. This binding occurred due to the formation of non-covalent NH···X (X = O, S, F) and CO···HX (X = O, S) contacts. NH···O contacts for [BnHn−1OH]2− Iso_1 systems were the strongest of all the molecular complexes considered. Complexes based on ammonium and hydroxy derivatives of closo-borate anion [BnHn−1X]y− (X = NH3, OH) were the most stable among all the derivatives considered. The complex of [B10H9NH3]− with glycine was the most energetically favourable.

Thus, the quantum chemical calculations described in this paper can be applied for the construction of closo-borate anion molecular complexes with biomolecules, in particular with proteins. First of all, the use of closo-decaborate anion derivatives facilitated stronger binding with biomolecules. In addition, it is suggested that the introduction of exo-polyhedral ammonium groups into the closo-borate could promote strong binding between the cluster anion and the target biomolecule. Consequently, the presence of hydrogen bond acceptor groups in a biomolecule promotes strong binding to [BnHn−1NH3]− anions. An alternative to the ammonium derivatives is the hydroxy derivative of closo-borate anions [BnHn−1OH]2−. An advantage of these systems is their ability to form strong NCIs with both hydrogen bond donors and acceptors.

Future work will extend upon the results presented in this manuscript. Further research will involve calculations of molecular complexes with different amino acid types (featuring charged, uncharged, and hydrophobic side chains), followed by studies of complexes with oligopeptides and proteins. Upon completing these investigations, we will be able to formulate more precise design principles for constructing non-covalent complexes of closo-borate systems with various biomolecules. Predictions of the cluster’s binding mode with biomolecules, derived from our calculations, could be applied to the development of potential drugs for BNCT, as well as antiviral and antimicrobial agents.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/computation13120285/s1: Figure S1: Molecular graph of the topological analysis of the electron density distribution in complexes of [BnHn]2− clusters with glycine; Table S1: Main topological parameters of electron density for NCIs of complexes of [BnHn]2− clusters with glycine; Figure S2: Molecular graph of complexes of [BnHn−1NH3]− clusters with glycine; Table S2: Main topological parameters of electron density for NCIs of complexes of [BnHn−1NH3]− clusters with glycine; Figure S3: Molecular graph of Iso_1 complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− clusters with glycine; Table S3: Main topological parameters of electron density for NCIs of Iso_1 complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− clusters with glycine; Figure S4: Molecular graph of Iso_2 complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− clusters with glycine; Table S4: Main topological parameters of electron density for NCIs of Iso_2 complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− clusters with glycine; Figure S5: Molecular graph of Iso_3 complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− clusters with glycine; Table S5: Main topological parameters of electron density for NCIs of Iso_3 complexes of [BnHn−1OH]2− clusters with glycine; Figure S6: Molecular graph of Iso_1 complexes of [BnHn−1SH]2− clusters with glycine; Table S6: Main topological parameters of electron density for NCIs of Iso_1 complexes of [BnHn−1SH]2− clusters with glycine; Figure S7: Molecular graph of Iso_2 complexes of [BnHn−1SH]2− clusters with glycine; Table S7: Main topological parameters of electron density for NCIs of Iso_2 complexes of [BnHn−1SH]2− clusters with glycine. Figure S8: Molecular graph of complexes of [BnHn−1F]2− clusters with glycine; Table S8. Main topological parameters of electron density for NCIs of complexes of [BnHn-1F]2− clusters with glycine. Table S9: Main energetic parameters of non-covalent complexes of [BnHn−1X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2) with glycine; Table S10: Stability constants for complexes of [BnHn−1X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2) with glycine; Table S11: Main results of ETS-NOCV analysis of non-covalent complexes of [BnHn−1X]y− (X = H, NH3, OH, SH, F; n = 10, 12; y = 1, 2) with glycine.

Author Contributions

Investigation, I.N.K., A.S.N., A.V.K., and A.A.K.; Manuscript conceptualisation, I.N.K.; writing and original draft preparation, I.N.K., A.V.K., A.S.N., and A.A.K.; data analysis, I.N.K., A.S.N., A.V.K., and A.A.K.; visualisation, I.N.K.; editing, data analysis and interpretation, A.S.N., I.N.K., A.V.K., and A.A.K.; supervision K.Y.Z. and N.T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 25-23-00530).

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Müller-Dethlefs, K.; Hobza, P. Noncovalent Interactions: A Challenge for Experiment and Theory. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollman, P.A. Noncovalent Interactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 1977, 10, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storer, M.C.; Hunter, C.A. The Surface Site Interaction Point Approach to Non-Covalent Interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 10064–10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretiakov, S.; Nigam, A.; Pollice, R. Studying Noncovalent Interactions in Molecular Systems with Machine Learning. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 5776–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladilo, G.; Hassanali, A. Hydrogen Bonds and Life in the Universe. Life 2018, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.; Mukherjee, S.; Andreo, J.; Sinelshchikova, A.; Peccati, F.; Jiménez-Osés, G.; Wuttke, S.; Boxer, S.G. Electrostatic Atlas of Non-Covalent Interactions Built into Metal–Organic Frameworks. Nat. Chem. 2025, 17, 1920–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, H. Binding Mechanisms in Supramolecular Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3924–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermann, F.; Schneider, H.-J. Experimental Binding Energies in Supramolecular Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5216–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevi, A.S.; Sastry, G.N. Cooperativity in Noncovalent Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2775–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertazzi, A.; Krull, F.; Knapp, E.-W.; Gamez, P. Recent Advances in Anion–π Interactions. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karas, L.J.; Wu, C.; Das, R.; Wu, J.I. Hydrogen Bond Design Principles. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2020, 10, e1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Lubbe, S.C.C.; Fonseca Guerra, C. The Nature of Hydrogen Bonds: A Delineation of the Role of Different Energy Components on Hydrogen Bond Strengths and Lengths. Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 2760–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wager, J.F. New Perspective on Hydrogen Bonding. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 41674–41679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunan, E.; Desiraju, G.R.; Klein, R.A.; Sadlej, J.; Scheiner, S.; Alkorta, I.; Clary, D.C.; Crabtree, R.H.; Dannenberg, J.J.; Hobza, P.; et al. Definition of the Hydrogen Bond (IUPAC Recommendations 2011). Pure Appl. Chem. 2011, 83, 1637–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschlag, D.; Pinney, M.M. Hydrogen Bonds: Simple after All? Biochemistry 2018, 57, 3338–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R.F.; Matamoros, E.; Cintas, P.; Palacios, J.C. Imine or Enamine? Insights and Predictive Guidelines from the Electronic Effect of Substituents in H-Bonded Salicylimines. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 5838–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenthold, P.G.; Squires, R.R. Bond Dissociation Energies of F2– and HF2–. A Gas-Phase Experimental and G2 Theoretical Study. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 2002–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.A.K.; Hoy, V.J.; O’Hagan, D.; Smith, G.T. How Good Is Fluorine as a Hydrogen Bond Acceptor? Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 12613–12622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond and the Structure of Molecules and Crystals: An Introduction to Modern Structural Chemistry; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1960; ISBN 0801403332. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, S.; Loh, S.; Herschlag, D. The Energetics of Hydrogen Bonds in Model Systems: Implications for Enzymatic Catalysis. Science 1996, 272, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matienko, L.I.; Mil, E.M.; Albantova, A.A.; Goloshchapov, A.N. The Role H-Bonding and Supramolecular Structures in Homogeneous and Enzymatic Catalysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głowacki, E.D.; Irimia-Vladu, M.; Bauer, S.; Sariciftci, N.S. Hydrogen-Bonds in Molecular Solids—From Biological Systems to Organic Electronics. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanova, E.V.; Stogniy, M.Y.; Anufriev, S.A.; Suponitsky, K.Y.; Sivaev, I.B.; Bregadze, V.I. Intramolecular Proton-Hydride Activation Using the Example of Cobalt Bis(Dicarbollide) Derivative [8-Et(HO)C HN-3,3′-Co(1,2-C2B9H10)(1′,2′-C2B9H11)]. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2025, 578, 122529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, L.W.; Aghaei Hakkak, R.; Ranjbar, M.; Schleid, T. Crystal Structures and Thermal Analyses of Three New High-Energy Hydrazinium Hydro-Closo-Borates. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeeva, V.V.; Vologzhanina, A.V.; Malinina, E.A.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Dihydrogen Bonds in Salts of Boron Cluster Anions [BnHn]2− with Protonated Heterocyclic Organic Bases. Crystals 2019, 9, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kim, J.S.; Fan, J.; Peng, X.; Matějíček, P. Boron Cluster Leveraged Polymeric Building Blocks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 4104–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, D.; Li, J.; Sun, F.; Yan, H.; Poater, J.; Solà, M. Cage– ···Cage– Interaction: Boron Cluster-Based Noncovalent Bond and Its Applications in Solid-State Materials. JACS Au 2021, 1, 2047–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Pecina, A.; Řezáč, J.; Lepšík, M.; Sárosi, M.B.; Hnyk, D.; Hobza, P. Benchmark Data Sets of Boron Cluster Dihydrogen Bonding for the Validation of Approximate Computational Methods. ChemPhysChem 2020, 21, 2599–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubina, E.S.; Bakhmutova, E.V.; Filin, A.M.; Sivaev, I.B.; Teplitskaya, L.N.; Chistyakov, A.L.; Stankevich, I.V.; Bakhmutov, V.I.; Bregadze, V.I.; Epstein, L.M. Dihydrogen Bonding of Decahydro-Closo-Decaborate(2-) and Dodecahydro-Closo-Dodecaborate(2-) Anions with Proton Donors: Experimental and Theoretical Investigation. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 657, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Lepšík, M.; Horinek, D.; Havlas, Z.; Hobza, P. Interaction of Carboranes with Biomolecules: Formation of Dihydrogen Bonds. ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Hnyk, D.; Lepšík, M.; Hobza, P. Interaction of Heteroboranes with Biomolecules: Part 2. The Effect of Various Metal Vertices and Exo-Substitutions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 2085–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; S Hosmane, N.; Zhu, Y. Boron Chemistry for Medical Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaev, I.B.; Bregadze, V.V. Polyhedral Boranes for Medical Applications: Current Status and Perspectives. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 2009, 1433–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñas I Teixidor, C. The Uniqueness of Boron as a Novel Challenging Element for Drugs in Pharmacology, Medicine and for Smart Biomaterials. Future Med. Chem. 2013, 5, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W.Y.; Chiu, Y.-L.; Huang, S.-C.; Huang, W.-Y.; Hsu, F.-T.; Lee, H.Y.; Wang, T.-W.; Keng, P.Y. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy Enhanced by Boronate Ester Polymer Micelles: Synthesis, Stability, and Tumor Inhibition Studies. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 4215–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futamura, G.; Kawabata, S.; Siba, H.; Kuroiwa, T.; Suzuki, M.; Kondo, N.; Ono, K.; Sakurai, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Todo, T.; et al. A Case of Radiation-Induced Osteosarcoma Treated Effectively by Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. Radiat. Oncol. 2014, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gona, K.B.; Gómez-Vallejo, V.; Padro, D.; Llop, J. [18F]Fluorination of o-Carborane via Nucleophilic Substitution: Towards a Versatile Platform for the Preparation Of 18F-Labelled BNCT Drug Candidates. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 11491–11493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitto-Barry, A. Polymers and Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT): A Potent Combination. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghi, P.; Li, J.; Hosmane, N.S.; Zhu, Y. Next Generation of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT) Agents for Cancer Treatment. Med. Res. Rev. 2023, 43, 1809–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.H.; Seldon, C.; Butkus, M.; Sauerwein, W.; Giap, H.B. A Review of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: Its History and Current Challenges. Int. J. Part. Ther. 2022, 9, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymova, M.A.; Taskaev, S.Y.; Richter, V.A.; Kuligina, E.V. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Cancer Commun. 2020, 40, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuoka, Y.; Aihara, T.; Higashino, M.; Kurisu, Y.; Haginomori, S.; Nihei, K.; Ono, K. Expression Rate of LAT1 in High-Grade Parotid Gland Carcinoma and Potential of BNCT as a Treatment Option for Recurrent Parotid Gland Carcinoma. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2025, 218, 111657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Sanada, Y.; Hattori, Y.; Suzuki, M. Correlation between the Expression of LAT1 in Cancer Cells and the Potential Efficacy of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. J. Radiat. Res. 2023, 64, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, J.; Hosmane, N.S.; Zhu, Y. In Silico Assessments of the Small Molecular Boron Agents to Pave the Way for Artificial Intelligence-Based Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 279, 116841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retini, M.; Järvinen, J.; Bahrami, K.; Tampio, J.; Bartoccini, F.; Riihelä, P.; Pehkonen, H.; Värä, A.; Laitinen, T.; Huttunen, K.M.; et al. Asymmetric Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Both Enantiomers of 5- and 6-Boronotryptophan as Potential Boron Delivery Agents for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 2121–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cígler, P.; Kožíšek, M.; Řezáčová, P.; Brynda, J.; Otwinowski, Z.; Pokorná, J.; Plešek, J.; Grüner, B.; Dolečková-Marešová, L.; Máša, M.; et al. From Nonpeptide toward Noncarbon Protease Inhibitors: Metallacarboranes as Specific and Potent Inhibitors of HIV Protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15394–15399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kožíšek, M.; Cígler, P.; Lepšík, M.; Fanfrlík, J.; Řezáčová, P.; Brynda, J.; Pokorná, J.; Plešek, J.; Grüner, B.; Grantz Šašková, K.; et al. Inorganic Polyhedral Metallacarborane Inhibitors of HIV Protease: A New Approach to Overcoming Antiviral Resistance. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4839–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Brynda, J.; Řezáč, J.; Hobza, P.; Lepšík, M. Interpretation of Protein/Ligand Crystal Structure Using QM/MM Calculations: Case of HIV-1 Protease/Metallacarborane Complex. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 15094–15102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Brynda, J.; Kugler, M.; Lepšík, M.; Pospíšilová, K.; Holub, J.; Hnyk, D.; Nekvinda, J.; Grüner, B.; Řezáčová, P. B–H⋯π and C–H⋯π Interactions in Protein–Ligand Complexes: Carbonic Anhydrase II Inhibition by Carborane Sulfonamides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 1728–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, A.; Bauzá, A. Closo -Carboranes as Dual CH⋯π and BH⋯π Donors: Theoretical Study and Biological Significance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 19944–19950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System—Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, M.; Ehlert, S.; Grimme, S.; Mewes, J.-M. Do Optimally Tuned Range-Separated Hybrid Functionals Require a Reparametrization of the Dispersion Correction? It Depends. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 8097–8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellweg, A.; Hättig, C.; Höfener, S.; Klopper, W. Optimized Accurate Auxiliary Basis Sets for RI-MP2 and RI-CC2 Calculations for the Atoms Rb to Rn. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2007, 117, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynova, S.; Krisyuk, V.; Sukhikh, A.; Benassi, E. β-Diketonate Coordination: Vibrational Properties, Electronic Structure, Molecular Topology, and Intramolecular Interactions. Beryllium(II), Copper(II), and Lead(II) as Study Cases. J. Phys. Chem. A 2025, 129, 924–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najibi, A.; Casanova-Páez, M.; Goerigk, L. Analysis of Recent BLYP- and PBE-Based Range-Separated Double-Hybrid Density Functional Approximations for Main-Group Thermochemistry, Kinetics, and Noncovalent Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 4026–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Eng, J.; Penfold, T.J. Conformational Control of Donor–Acceptor Molecules Using Non-Covalent Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 8035–8044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. An Improvement of the Resolution of the Identity Approximation for the Formation of the Coulomb Matrix. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1740–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-Fitting Basis Sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, N.; Ghaida, F.A.; El Hajj, Z.; Diab, M.; Floquet, S.; Mehdi, A.; Naoufal, D. Recent Achievements on Functionalization within Closo-Decahydrodecaborate [B10H10]2− Clusters. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202200770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaev, I.B.; Prikaznov, A.V.; Naoufal, D. Fifty Years of the Closo-Decaborate Anion Chemistry. Collect. Czechoslov. Chem. Commun. 2010, 75, 1149–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyukin, I.N.; Novikov, A.S.; Zhdanov, A.P.; Zhizhin, K.Y.; Kuznetsov, N.T. QTAIM Analysis of Mono-Hydroxy Derivatives of Closo-Borate Anions [BnHn–1OH]2– (n = 6, 10, 12). Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 64, 1825–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyukin, I.N.; Vlasova, Y.S.; Novikov, A.S.; Zhdanov, A.P.; Hagemann, H.R.; Zhizhin, K.Y.; Kuznetsov, N.T. B-F Bonding and Reactivity Analysis of Mono- and Perfluoro-Substituted Derivatives of Closo-Borate Anions (6, 10, 12): A Computational Study. Polyhedron 2022, 211, 115559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Anwar, S.; Holub, J.; Tok, O.; Jelínek, T.; Růžičková, Z.; Fojt, L.; Šolínová, V.; Kašička, V.; Grüner, B. Synthesis and Selected Properties of Nonahalogenated 2-Ammonio-Decaborate Anions and Their Derivatives Substituted at N-Centre. J. Organomet. Chem. 2018, 865, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riplinger, C.; Neese, F. An Efficient and Near Linear Scaling Pair Natural Orbital Based Local Coupled Cluster Method. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 034106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riplinger, C.; Sandhoefer, B.; Hansen, A.; Neese, F. Natural Triple Excitations in Local Coupled Cluster Calculations with Pair Natural Orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 134101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riplinger, C.; Pinski, P.; Becker, U.; Valeev, E.F.; Neese, F. Sparse Maps—A Systematic Infrastructure for Reduced-Scaling Electronic Structure Methods. II. Linear Scaling Domain Based Pair Natural Orbital Coupled Cluster Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 024109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bader, R.; Legare, D. Properties of Atoms in Molecules: Structures and Reactivities of Boranes and Carboranes. Can. J. Chem. 1992, 70, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 1985, 18, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, S.F.; Bernardi, F. The Calculation of Small Molecular Interactions by the Differences of Separate Total Energies. Some Procedures with Reduced Errors. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitoraj, M.; Michalak, A. Donor–Acceptor Properties of Ligands from the Natural Orbitals for Chemical Valence. Organometallics 2007, 26, 6576–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabando, R.C.; Riplinger, C.; Wennmohs, F.; Neese, F.; Bistoni, G. Broadening the Scope of the ETS-NOCV Scheme: A Versatile Implementation in ORCA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2025, 21, 7920–7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukułka, M.; Żurowska, O.; Mitoraj, M.; Michalak, A. ETS-NOCV Description of Chemical Bonding: From Covalent Bonds to Non-Covalent Interactions. J. Mol. Model. 2025, 31, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemcraft—Graphical Software for Visualization of Quantum Chemistry Computations. Version 1.8, Build 682. Available online: https://www.chemcraftprog.com (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Jeffrey, G.A. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997; ISBN 9780195095494. [Google Scholar]

- Nowroozi, A.; Hajiabadi, H.; Akbari, F. OH···O and OH···S Intramolecular Interactions in Simple Resonance-Assisted Hydrogen Bond Systems: A Comparative Study of Various Models. Struct. Chem. 2014, 25, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, S. Intramolecular Hydrogen Bond Energy and Its Decomposition—O–H∙∙∙O Interactions. Crystals 2020, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhav, V.A.; Saikrishnan, K. The Realm of Unconventional Noncovalent Interactions in Proteins: Their Significance in Structure and Function. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 22268–22284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruś, W.; Kafel, R.; Bojarski, A.J.; Kurczab, R. Hydrogen Bonds with Fluorine in Ligand–Protein Complexes-the PDB Analysis and Energy Calculations. Molecules 2022, 27, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvit, C.; Invernizzi, C.; Vulpetti, A. Fluorine as a Hydrogen-Bond Acceptor: Experimental Evidence and Computational Calculations. Chem. A Eur. J. 2014, 20, 11058–11068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Zou, J.; Tian, F.; Shang, Z. Fluorine Bonding—How Does It Work In Protein−Ligand Interactions? J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 2344–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaersgaard, A.; Lane, J.R.; Kjaergaard, H.G. Room Temperature Gibbs Energies of Hydrogen-Bonded Alcohol Dimethylselenide Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 8427–8434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscic, B. Active Thermochemical Tables: Water and Water Dimer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 11940–11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isayev, O.; Gorb, L.; Leszczynski, J. Theoretical Calculations: Can Gibbs Free Energy for Intermolecular Complexes Be Predicted Efficiently and Accurately? J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 1598–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.L.; Jensen, C.S.; Mackeprang, K.; Du, L.; Jørgensen, S.; Kjaergaard, H.G. Similar Strength of the NH···O and NH···S Hydrogen Bonds in Binary Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 11074–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, A.A.; Khisamiev, M.B.; Solomonov, B.N.; Yagofarov, M.I. Compensation Relationship in Thermodynamics of Gas-Phase Molecular Complexation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025. Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaersgaard, A.; Pal, D.; Vogt, E.; Skovbo, T.E.; Kjaergaard, H.G. Room Temperature Gas-Phase Detection and Formation Gibbs Energy of the Water Dimethyl Ether Bimolecular Complex. J. Phys. Chem. A 2025, 129, 4438–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthilnithy, R.; Weerasingha, M.S.S.; Dissanayake, D.P. Interaction of Caffeine Dimers with Water Molecules. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014, 1028, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).