Abstract

Cancer progression is primarily driven by disruptions in critical biological pathways, including ErbB signaling, p53-mediated apoptosis, and GSK3 signaling. However, experimental and clinical studies typically identify only limited disease-associated genes, challenging traditional pathway analysis methods that require larger gene sets. To overcome this limitation, reliably expanded gene sets are required to align with cancer-related pathways. Although various propagation methods are available, the key challenge is to select techniques that can effectively propagate signals from limited seed gene sets through protein interaction networks, thereby generating robust, expanded sets capable of revealing pathway disruptions in cancer. In this study, the number of seed genes was systematically varied to evaluate the alignment of pathways obtained from different propagation methods with known pathways using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotations. Among the evaluated propagation methods, normalized Laplacian diffusion (NLD) demonstrated the strongest alignment with reference pathways, with an average area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 95.11% and an area under precision–recall (AUPR) of 71.20%. Focusing specifically on well-established cancer pathways, we summarized the enriched pathways and discussed their biological relevance with limited gene input. Results from multiple runs were aggregated to identify genes consistently prioritized but absent from core pathway annotations, representing potential pathway extensions. Notable examples include RAC2 (ErbB pathway), FOXO3 and ESR1 (GSK3 signaling), and XIAP and BRD4 (p53 pathway), which were significantly associated with patient survival. Literature validation confirmed their biological relevance, underscoring their potential as prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. In summary, NLD-based diffusion proves effective for pathway discovery from limited input, extending beyond annotated members to reveal clinically relevant genes with therapeutic and biomarker potential.

1. Introduction

Understanding the molecular basis of cancer requires analytical methods capable of handling large-scale transcriptomic data and translating gene-level findings into meaningful biological insights [1]. While statistical and machine learning approaches can identify differentially expressed genes and key molecular features, interpreting these results within a functional biological context remains a major challenge [2]. Pathway enrichment analysis addresses this issue by mapping gene-level changes onto known biological pathways, offering a structured framework to uncover underlying disease mechanisms, particularly valuable in cancer research. However, in many experimental and clinical settings, such as patient-derived studies, only a small number of disease-associated genes are typically identified [3]. This limited gene set poses a significant challenge for traditional enrichment methods, which often require larger input sizes to detect pathway-level associations with confidence [4]. Consequently, these methods may fail to uncover relevant biological processes when applied to sparse, context-specific data such as biomarkers or transcription factors derived from wet-lab experiments. This highlights the need for innovative strategies that can expand small gene sets in a biologically meaningful way. Such approaches would enhance the interpretability of experimental data, enabling more accurate identification of disease-related pathways and potentially revealing novel therapeutic targets [5]. Especially in cancer research, the disruption of key signaling pathways, including ErbB signaling, p53-mediated apoptosis, GSK3 signaling, JAK-STAT signaling, drives tumorigenesis and progression [6,7]. Identifying these cancer-related pathways from limited gene sets is essential for understanding tumor biology, guiding treatment strategies, and discovering new therapeutic targets. Expanding these small gene sets to uncover additional candidate genes remains a key objective in precision oncology.

Several studies have demonstrated that incorporating network information enhances the ability to identify significant pathways [8,9]. The protein–protein interaction (PPI) network is a crucial tool in this analysis, as it provides a framework for understanding the complex protein interactions and their roles in biological processes [10,11,12]. The PPI network has been extensively used in pathway enrichment analysis to uncover hidden relationships between genes within the input set [13,14]. When analyzing the PPI networks, two widely used approaches for retrieving protein relevant to disease are neighborhood-based techniques and network diffusion techniques. The neighborhood method identifies nodes that are directly connected to a set of seed proteins, allowing these neighboring nodes to be incorporated into the initial seed set for pathway enrichment analysis [15,16]. In PPI networks, connections typically involve one step (NB1) or two steps (NB2) from the seed nodes to identify closely interacting proteins [17]. In contrast, propagation techniques apply diffusion algorithms to spread the influence of seed nodes across the entire network, calculating diffusion scores to rank the importance of proteins based on their relevance to seed nodes. This technique has been widely used to extend gene sets for pathway enrichment analysis in various studies, such as in the identification of tumor-related genes in breast cancer patients [18] and immune-related genes in COVID-19 cases [19]. The RIDDLE algorithm uses the network structure by combining local extension and reflective diffusion as features for support vector machine (SVM), enhancing the traditional hypergeometric test and demonstrating the strength of diffusion in functional networks [20]. Random walks were originally designed to understand the overall structure of networks, involving a random movement from one node to another neighboring node [21]. Random walk with restart (RWR) enhances the spread of influence by repeatedly restarting at the seed nodes [22,23], outperforming other algorithms in gene prioritization within multiplex and heterogeneous networks [24], making it a state-of-the-art ‘guilt-by-association’ method [25]. A family of kernels and regularization on graphs has been introduced [26], providing beneficial tools for network diffusion. The graph Laplacian serves as a generator for label propagation, with the choice of Laplacian dependent on the specific problems being addressed [27]. The Laplacian kernel diffusion (LD) and normalized Laplacian diffusion (NLD) [26] are among the popular methods used for identifying disease-related gene [28,29]; they have been applied to find additional immune-associated genes of COVID-19 [30]. However, this advantage may not hold universally across different contexts or input data, since PPI networks capture protein-level interactions, whereas pan-level pathway networks (GO and KEGG) include RNA, DNA, and small-molecule signaling. These fundamental differences mean that direct comparisons of the alignment of method-derived pathways with relevant references can be confounded and still require further investigation. While previous network-diffusion studies have compared Laplacian and random-walk-based methods for pathway analysis [31,32], few have systematically examined their performance under limited-gene conditions that often occur in clinical or rare-disease studies. In this work, we introduce an NLD framework specifically designed to handle small seed sets, enabling robust pathway recovery from sparse molecular input. Moreover, we integrate diffusion-based prioritization with survival validation to demonstrate the biological and prognostic relevance of the identified genes.

To address these challenges, we investigate node set extension approaches (NB1, NB2, RWR, LD, and NLD) on protein–protein interaction networks, focusing on alignment with reference pathways from GO and KEGG. By comparing different propagation methods in the context of well-established cancer pathways, we aim to identify the most effective approach for expanding limited gene sets. We introduce a pruning strategy to highlight consistently prioritized genes beyond original pathway annotations and validate their clinical relevance through survival analysis and literature evidence. This work provides both a robust computational framework for pathway discovery from limited input and novel biological insights for biomarker and therapeutic target identification.

2. Materials and Methods

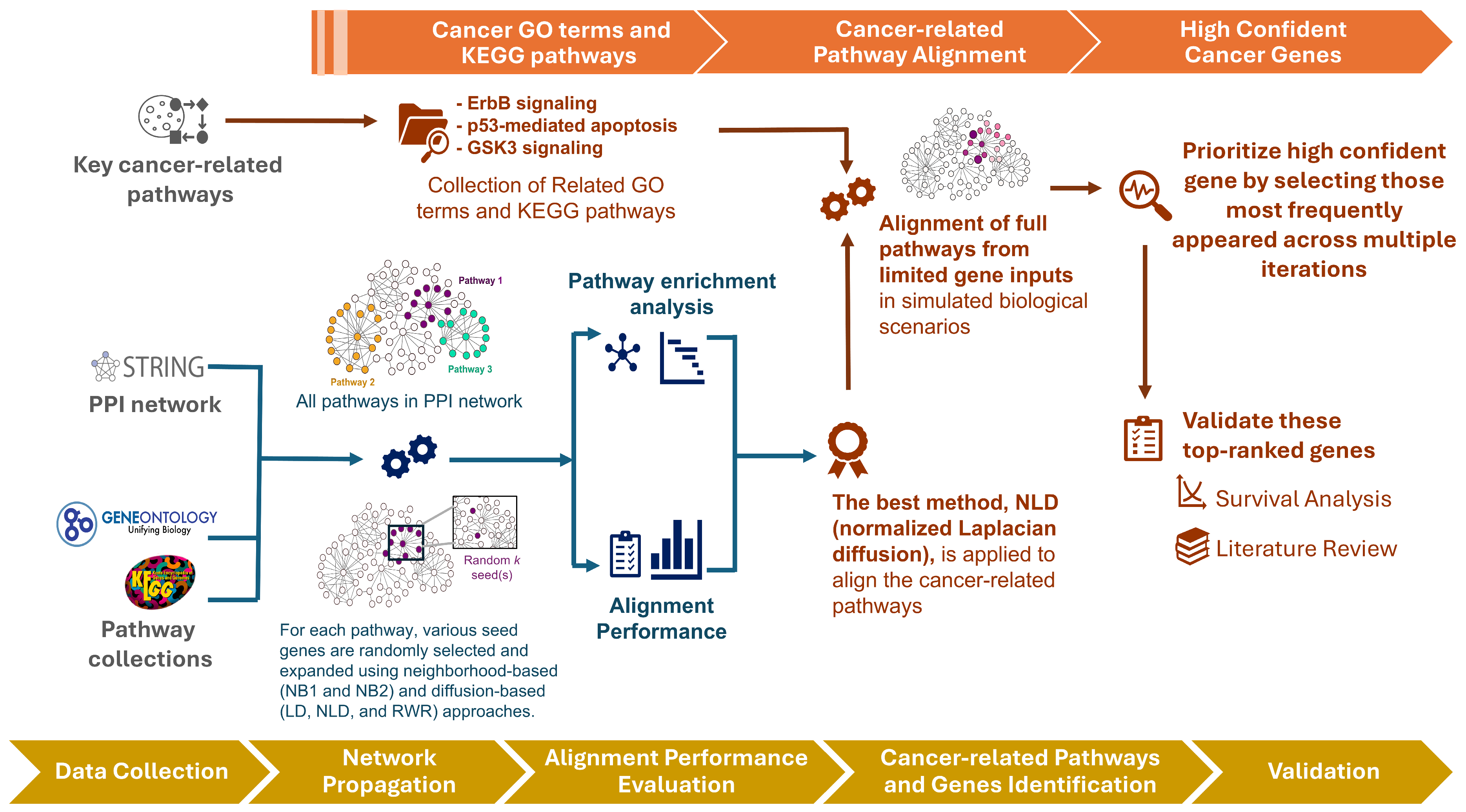

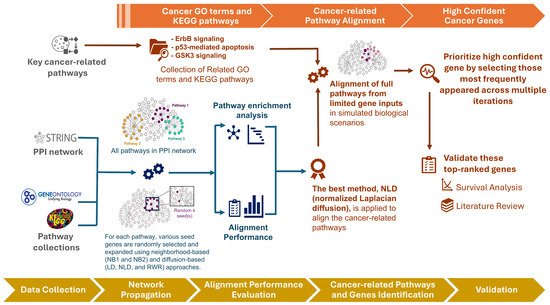

An overview of our framework is illustrated in Figure 1. We begin by evaluating the performance of three diffusion-based methods—Laplacian kernel diffusion (LD), normalized Laplacian diffusion (NLD), and random walk with restart (RWR)—in comparison with two neighborhood-based approaches: one-step (NB1) and two-step (NB2) extensions. These methods exhibit distinct behaviors in extending seed sets through the PPI network. We assess their alignment to functional pathways using pathway annotations from GO [33] and KEGG [34] pathways under varying seed set sizes.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the proposed framework. Overview of the analysis pipeline, from seed selection and network diffusion to pathway alignment, candidate gene prioritization, and validation.

Following this benchmarking, we focus on three well-established cancer-related pathways—ErbB signaling, p53-mediated apoptosis, and GSK3 signaling—assuming only a small subset of genes is initially detected (e.g., from patient data) to simulate realistic biological scenarios. Notably, some of the prioritized genes lie outside the original pathway annotations but may still play important roles in oncogenic processes. To validate these high-confidence novel candidates, we select the most consistently ranked genes across multiple iterations for survival analysis and literature review.

2.1. Dataset Collections

2.1.1. Pathway Collections

The dataset included pathways from both GO terms [33] and KEGG pathways [34]. GO terms [33], which define gene functions in terms of biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions [35], were sourced from the R libraries AnnotationDbi [36] (version 1.66.0), org.Hs.eg.db [37], and Go.db [38] (version 3.19.1). Only pathways related to biological processes were considered, resulting in the collection of 12,417 GO terms related to biological processes and 359 KEGG pathways. However, the GO hierarchy contains many leaf nodes that represent highly specific pathways, which often exhibit significant similarity or overlap. To reduce redundancy and capture more general biological processes, we focused on broader pathways at higher hierarchical levels, improving the interpretability of the analysis. Specifically, we selected pathways from the top three hierarchical levels (≤3) using the GOxploreR package (version 1.2.8) [39]. For KEGG pathways [34], which depict interactions among genes, proteins, and metabolites in biological systems [40], the KEGGREST package [41] (version 1.36.3) was used. Pathways categorized under Metabolism and Human Diseases were excluded from the analysis. Larger pathways encompass a wide range of processes, increasing their complexity and making them more difficult to fully characterize. Conversely, smaller pathways were generally more specific and straightforward, simplifying their inclusion in databases [5]. For both GO and KEGG pathway collections, only pathways containing between 5 and 500 genes were considered. After applying these criteria, we obtained 94 GO terms and 170 KEGG pathways for further analysis.

Furthermore, cancer is a complex and diverse disease characterized by the uncontrolled growth and division of cells [42]. In this study, we also present the efficacy of the network diffusion in detecting cancer-related biological pathways, focusing on three well-established functional pathways: the ErbB (Erythroblastic Leukemia Viral Oncogene Homolog) family pathway, the p53-mediated apoptosis pathway, and the GSK3 signaling pathway. These pathways play crucial roles in tumor development, cell survival, and the regulation of essential cellular processes. To evaluate the effectiveness of diffusion and neighborhood methods for pathway enrichment related to these specific pathways, we collected relevant GO terms and KEGG pathways from these three major pathway families, resulting in six distinct cases.

2.1.2. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction

The protein interaction information was retrieved from the STRING version 12.0 database [43], with the data type set to Homo sapiens. We selected only interactions with a combined score greater than 900, and resulting in the largest connected component, which produced a connected graph with 11,343 nodes and 95,092 interaction edges.

2.2. Network-Based Approaches to Retrieve More Relevant Proteins

Network-based approaches have emerged as powerful tools for identifying and retrieving proteins that are highly relevant to specific diseases or conditions. By applying intricate relationships and interactions within PPI networks, these methods can effectively expand the pool of potential targets by uncovering additional proteins that share functional similarities with known disease-related candidates. The simplest and commonly used approach for extending the list of relevant proteins for further pathway enrichment analysis is the so-called neighborhood-based method (NB1 and NB2). In contrast, the approach we present in this study is significantly more advanced and falls under the category of network diffusion techniques [32], which can be considered a global extension approach. We introduce three variants of network diffusion: LD, NLD, and RWR.

Let be a vector that assigns a value of 1 to nodes in (the set of seed nodes) and 0 to all other nodes. Let be the diagonal matrix where represents the sum of the i-th row of the adjacency matrix . The graph Laplacian, defined as , serves as the foundation for label propagation. The regularized Laplacian kernel is computed as , where I is the identity matrix and is the diffusion rate constant, set to 1 in this study. While adjusting could potentially improve performance by affecting the extent of diffusion, the default value of 1 is commonly used in previous studies and is considered a standard choice. We therefore adopt this value to provide a reference performance that is directly comparable and easily applicable in practical settings. The LD score, , for a group of nodes is then calculated as

Nodes closely connected to the seed nodes will exhibit higher diffusion scores, indicating stronger connectivity and greater influence from the initial group. However, since the diagonal matrix D contains node degrees, it tends to dominate, causing the diffusion to spread more from higher-degree nodes (hubs). To mitigate this bias, the normalized Laplacian kernel is introduced, which normalizes by degree [44]. It is computed as . The NLD score, , is then given by

RWR is a network diffusion method that prioritizes proteins based on their proximity to known seed candidates. It simulates a stochastic process where a walker moves through a PPI network while intermittently restarting from the seed proteins. The RWR score, , is iteratively computed follows:

where is a row-normalized adjacency (transition) matrix, is the restart probability, ranging from 0 to 1. In this study, is set to 0.3 based on previous studies [45], which tested values between 0.2 and 0.8 and found that diffusion performance did not vary substantially. This value was chosen as it provides a balance between global and local network information, allowing the diffusion process to capture both network-wide structure and neighborhood-specific information. Exploration of alternative values could be considered in future work to further assess method sensitivity. This method requires iterative calculations until convergence, with a tolerance threshold of 1 × 10−6 and maximum of 100 iterations.

All three methods require the same initial seed vector but differ in their transition matrices, resulting in distinct diffusion behaviors. The RWR method selects neighboring favoring higher-degree nodes due to their greater connectivity, while periodically restarting at the seed nodes. The NLD ensures an even distribution of information across the graph, regardless of node degree, whereas the LD biases diffusion toward high-degree nodes, amplifying their influence. In this study, these methods are employed to assess whether diffusion originating from high-degree genes or other genes is more effective in aligning pathways.

2.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Pathway enrichment analysis was conducted using the gprofiler2 package (version 0.2.3) in R [46]. The organism selected for analysis was Homo sapiens. The data sources for enrichment included GO terms under Biological Processes [33,35], KEGG [34], Reactome [47], and WikiPathways [48]. The enrichment ratio was calculated by dividing the number of genes from our gene set that were present in a pathway by the total number of genes in that pathway. The p-value tests the null hypothesis that the overlap between the input gene set and genes associated with a specific term occurred by random chance. The p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction method, with a significance threshold set at p-value < 0.05 for identifying significant pathways.

2.4. Survival Analysis

Survival analysis was performed to determine whether the expression levels of genes of interest are associated with patients’ overall survival (OS). The analysis was conducted using GEPIA2, a web-based platform [49], using data from multiple datasets within The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [50]. Samples were grouped by median expression level, and Kaplan–Meier curves were generated. Statistical significance was assessed with the log-rank test, and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals were reported.

2.5. Methodology Framework to Evaluate Network Diffusion

2.5.1. Framework for Reconstruction of Pathway Membership from PPI Topology

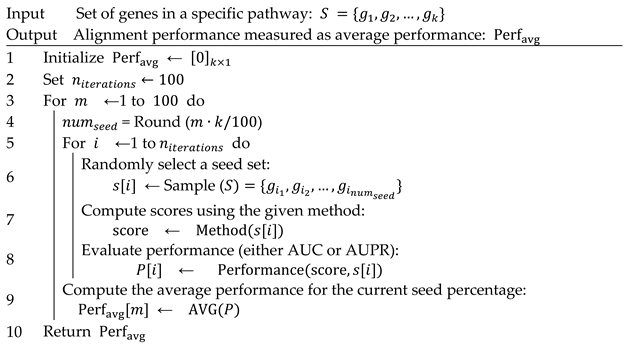

First, we collect protein interaction data from the STRING database [43] to construct a PPI network. Next, we obtain pathway data from both the GO [33] and KEGG [34] databases, including the associated genes for each pathway. To comprehensively assess the efficiency of different propagation methods in aligning potential genes with curated pathways, we define alignment performance based on the average performance metrics—either the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) or the area under the precision–recall curve (AUPR)—over 100 iterations of the strategy outlined in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Alignment performance evaluation for each pathway |

|

For each pathway of size , proteins within the pathway are randomly selected to form various seed sets ranging from 1% to 100% of the total genes in the pathway. This ensures a systematic evaluation of the methods’ ability to detect pathway members at different levels of seed node availability. To evaluate both diffusion techniques and neighborhood-based methods, we apply the following classification scheme: nodes within the true pathway set are considered positive and all other nodes in the network are considered negative. For each randomly generated seed set, alignment performance is assessed using AUC and AUPR. The AUC evaluates the model’s ability to differentiate between pathway and non-pathway genes, while AUPR focuses on precision and recall, providing insights into the ranking effectiveness of predicted genes. To ensure robustness and eliminate biases from specific seed selections, the seed sets are randomly generated 100 times for each predefined seed percentage. During each iteration, the scores are computed for all methods, and their effectiveness in alignment with curated pathways is recorded. Specifically, in each iteration , set.seed () is applied to ensure that randomization is controlled and that all methods are compared under identical random conditions.

Once all 100 iterations for each seed percentage are completed, the average AUC and AUPR values are calculated. These final averaged performance metrics represent the overall effectiveness of each method in maintaining consistency with pathway-associated genes across varying seed percentages. This evaluation framework is applied to all collected GO biological process terms and KEGG pathways, allowing a broad comparative analysis of how different pathway structures and network properties influence method performance. The results provide insights into the strengths and weaknesses of neighborhood-based versus diffusion-based approaches in different biological contexts.

2.5.2. Framework for Pathway Enrichment Analysis and Novel Genes Validation in Cancer Biology

We focused on well-known cancer biology-specific pathways, including the ErbB family pathway, the p53-mediated apoptosis pathway, and the GSK3 signaling pathway, to evaluate which method is more effective in identifying these pathways from a limited set of their associated genes. For each family, we randomly select only 10% of the gene set for enrichment analysis. The neighborhood and diffusion approaches are then applied to compare the pathways identified by each method under identical conditions (i.e., using the same number of genes for enrichment) across all cases to assess which method yields the highest alignment results. Pathway enrichment was performed as described in Section 2.3, and the analysis was repeated 100 times to assess the occurrence of each pathway, as well as to calculate the average gene ratio and average p-value. Pathways that emerged in 50% or more of the iterations, with sizes ranging from 10 to 500 genes, were retained for further evaluation. Then, we sorted the pathways by their average gene ratio to highlight those that were most significant in each case.

After conducting pathway analysis, we recognized the critical importance of selecting appropriate input for pathway enrichment. To further investigate potential biological relevance, we identified the top-ranking genes that frequently appeared across analyses but were not originally included in the reference pathway. These genes were subsequently subjected to survival analysis and further examined through a comprehensive review of biological literature.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Node Set Expansion Techniques Through Network Topology in PPI

GO terms and KEGG pathways were collected, and PPI network was constructed as detailed in Section 2.1. Our selection criteria identified a substantial set of representative pathways: 94 GO terms and 170 KEGG pathways. Analyzing these pathways provides intriguing insights into the structural characteristics of the underlying biological data as detailed in File S1, with KEGG pathways generally having a higher number of genes, greater modularity, and higher average degree per pathway compared to GO pathways.

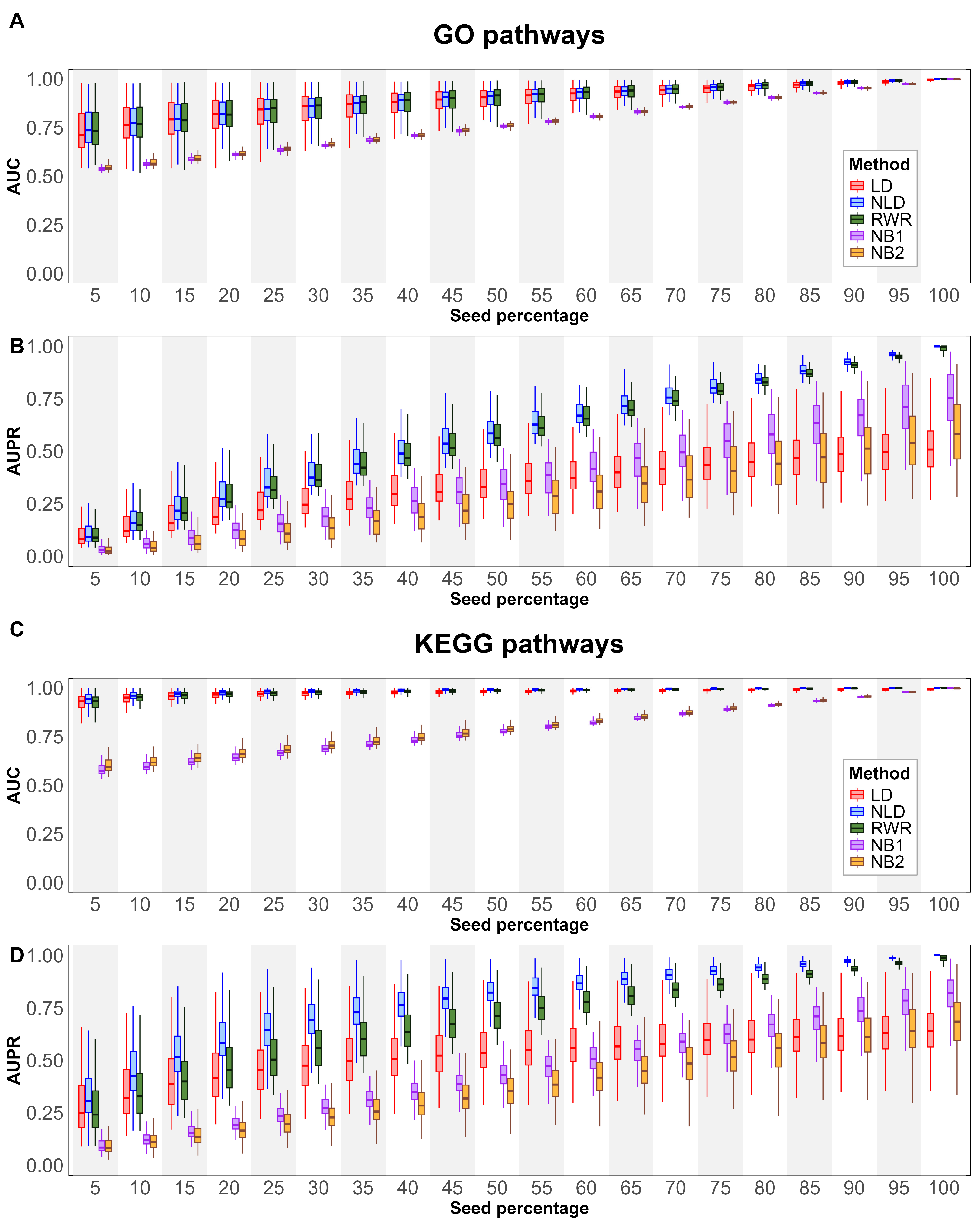

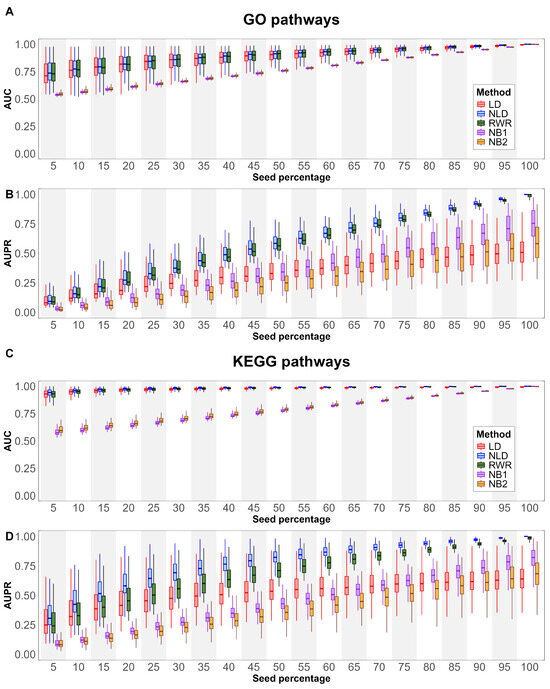

We evaluate the alignment with curated pathways obtained by various node extension methods to GO and KEGG pathways, as described in Section 2.5.1. All GO terms under biological process, testing different seed percentages to evaluate the alignment with reference pathways. The results, measuring using AUC and AUPR, are presented in Figure 2A,B. For AUC, the diffusion-based method demonstrated stronger alignment than the neighborhood-based methods across all seed percentages. While the performance of NB1 and NB2 increased linearly with higher seed percentages, showing a steady trend across all GO pathways, diffusion-based methods exhibited a broader performance range at smaller seed percentages. This suggests that diffusion methods are more sensitive to seed variability at lower percentages, likely due to the sparse distribution of seed nodes in the network. As seed density increases, the performance gap between diffusion-based and neighborhood-based approaches narrows. For AUPR, an interesting trend emerged. The median performance of NB1 was higher than NB2, suggesting that NB2’s broader expansion may introduce more false positives. The LD method demonstrated improved performance up to a seed percent of 50%, after which its performance plateaued and eventually fell below that of the neighborhood-based methods. This indicates that LD may be more effective for moderate seed densities but less so at higher seed percentages. Notably, NLD and RWR showed nearly identical performance across all seed percentages, suggesting that both methods are robust when using small gene sets.

Figure 2.

Boxplots show pathway relevance metrics across different percentages of seed nodes. Panels (A,C) illustrate AUC results, while panels (B,D) depict AUPR outcomes for GO (A,B) and KEGG (C,D) pathways.

A similar analysis was conducted for KEGG pathways (see Section 2.5.1), with the results shown in Figure 2C,D. The overall AUC trends for KEGG pathways closely resembled those observed for GO terms. However, the performance of all methods was consistently higher in KEGG pathways, with diffusion-based techniques, demonstrating a clear advantage, particularly at smaller seed percentages. This can be attributed to the higher degree of connectivity in KEGG pathways, which enables more effective propagation of information compared to GO terms, where nodes typically have lower connectivity. For AUPR, NB1, NB2, and LD followed patterns similar to those observed in GO terms. However, a key distinction was observed between NLD and RWR. While these two methods performed similarly in GO terms, NLD outperformed RWR in KEGG pathways. This suggests that KEGG pathways, due to their higher connectivity, are better suited for certain diffusion strategies like NLD. The highest pathway alignment of NLD in KEGG pathways indicates that using structured network propagation can enhance the identification of relevant genes in functionally cohesive pathways.

In Table 1, when averaging across all seed percentages, the NLD method shows the overall highest alignment, with an AUC of 0.8905 and AUPR of 0.5877 for GO pathways, and slightly higher values for KEGG pathways, with an AUC of 0.9816 and AUPR of 0.7746. This indicates that NLD is consistently strong across various metrics, suggesting its reliability for pathway prioritization.

Table 1.

The average alignment metric across all percentages of seeds, with the highest performance in each case highlighted in bold (average ± SD).

From our analysis, NLD achieved greater pathway relevance to annotated pathway than other methods across both GO terms and KEGG pathways, reinforcing the effectiveness of spreading information across the network rather than emphasizing high-degree nodes, as seen in LD and RWR. The key reason is that NLD corrects for node degree, making it more stable with limited seed genes. This reduces bias toward highly connected ‘hub’ genes and yields more robust results when only a few seed genes are available. LD was particularly effective when the seed percentage was below 20%, as it focuses on high-degree seed nodes. However, as the seed percentage increased beyond 80%, LD’s performance dropped below that of the neighborhood-based methods. This decline occurs because LD becomes overly focused on high-degree nodes, preventing effective propagation across the network. RWR, by contrast, continuously restarts from the seed nodes, allowing better integration of global and local information compared with LD. However, because the random walk process tends to revisit high-degree nodes more frequently, RWR still exhibits a bias toward hub genes. In comparison, NLD further normalizes the diffusion process by accounting for node degree and network topology, which reduces this hub bias. This effect becomes more apparent in KEGG pathways, where higher modularity and denser connectivity among seed genes make NLD more effective at capturing functionally cohesive clusters than RWR. In contrast, neighborhood-based methods performed better in such scenarios by considering direct connections to seed nodes. Among the neighborhood-based approaches, NB2 outperformed NB1 at seed percentages below 50%. However, with larger seed sets, NB2 expanded too broadly, predicting many false positives that were not part of the pathway. This led to a decrease in AUPR performance at higher seed percentages, as AUPR does not account for true negatives, and the increase in false positives negatively impacted the metric.

Overall, these findings highlight the importance of diffusion-based methods in pathway alignment with annotated pathways, particularly for datasets with low seed density. NLD emerged as the most robust approach, particularly in KEGG pathways where higher connectivity enhances network propagation. In contrast, neighborhood-based approaches remain viable alternatives when dealing with high seed percentages, as they mitigate excessive propagation and focus on immediate pathway associations. Moving forward, integrating hybrid approaches that balance network diffusion with direct neighborhood connectivity may provide an optimal strategy in large-scale biological networks.

3.2. Cancer Pathway Prioritization Using a Small Set of Seed Genes

In real-world biomedical research—such as transcriptomic analysis, biomarker discovery, and pathway-based disease modeling—researchers rarely obtain a complete set of genes associated with a specific biological pathway. This limitation is primarily due to experimental constraints, data sparsity, and inherent biological variability. As a result, pathway enrichment analysis often relies on an incomplete or small set of seed genes, prompting a critical question in finding different computational methods to detect known pathways from limited input data. Therefore, network-based approaches with network diffusion could help to retrieve more related genes. We simulate a realistic scenario in which only 10% of known cancer-related genes are available as seed inputs for network diffusion before performing the pathway enrichment analysis and repeated this process 100 times. This sampling strategy allowed us to systematically assess how consistently each computational method detects the full pathways from limited input (see Methods for details). Our results, presented in Section 3.1, reveal that the two-step neighborhood-based approach (NB2), while more computationally intensive, does not significantly enhance performance over the one-step version (NB1). Therefore, we adopt NB1 as the representative neighborhood-based approaches that use a fixed threshold to define pathway membership, diffusion-based methods assign continuous propagation scores to genes across the network. Our evaluation focuses on three well-established cancer biology pathways: the ErbB signaling pathway, the GSK3 signaling pathway, and the p53-mediated apoptosis pathway [6]. Specifically, the PPI network for the ErbB signaling pathway includes 56 genes found in the GO database [35] and 81 genes from KEGG [34]. The GSK3 signaling pathway comprises 194 GO genes and 292 KEGG genes, while the p53-mediated apoptosis pathway contains 46 GO genes and 71 KEGG genes. These curated gene sets, summarized in Table 2, serve as the reference pathways for our comparative performance analysis using small seed gene set.

Table 2.

List of GO terms and KEGG pathways associated with the well-established cancer-related pathways.

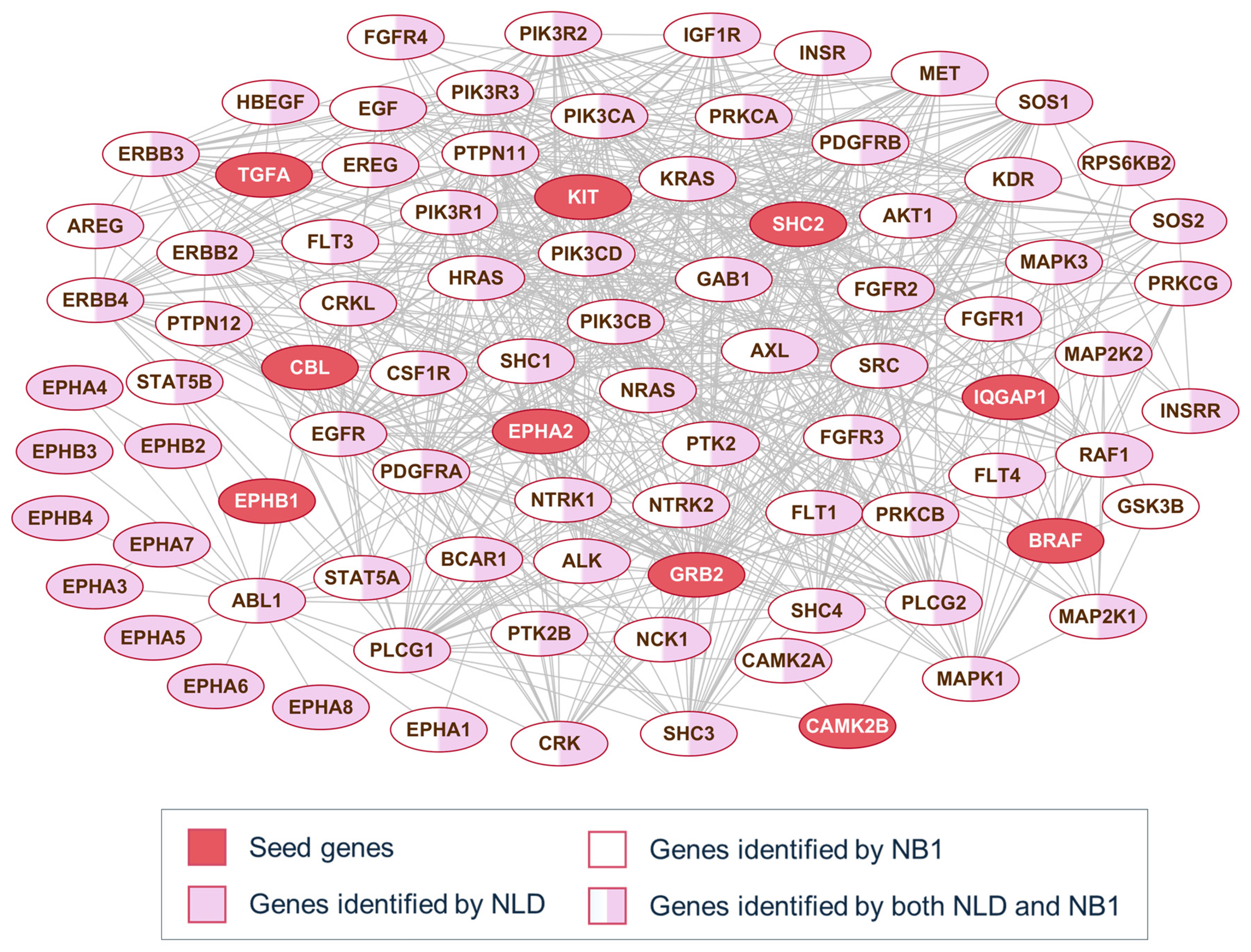

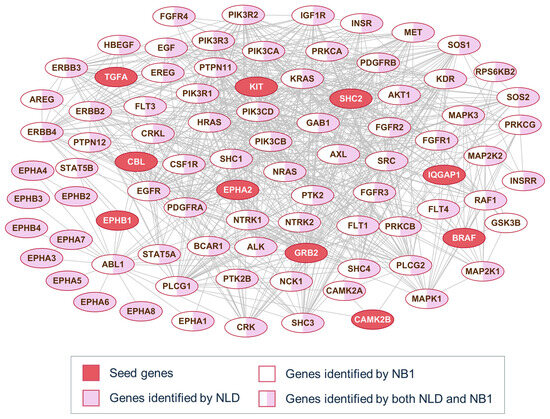

To better understand the behavior of the diffusion and neighborhood-based methods, Figure 3 presents a representative example of pathway alignment using partial seed information. For each pathway family, 10% of the original genes are randomly selected as seed genes, highlighted as red-filled nodes in the network. In many cases, both methods identify the same nodes, as NB1 consistently considers only 1-hop neighbors, while the NLD method may travel beyond immediate neighbors. However, not all directly connected nodes provide informative signals for identifying pathway members. Depending on the method applied to the PPI network, different subsets of the pathway genes appear in the top-scoring set. Specifically, nodes filled in pink are found only by the NLD method, while those in white are unique to NB1. These examples are shown for three well-known signaling pathways: the ErbB signaling pathway (Figure 3), the GSK3-related pathway, and the p53 signaling pathway (File S2).

Figure 3.

PPI connection of ErbB signaling pathway genes. Red nodes represent seed genes; Pink and white backgrounds highlight genes detected by NLD and NB1, respectively.

The top-scoring genes identified by each method were subsequently used for pathway enrichment analysis, as described in Section 2.5.2. We defined significantly enriched pathways as those with a p-value < 0.05, pathway sizes between 10 and 500 genes, and detected at least 50 out of 100 iterations. We evaluated enrichment performance using two metrics: average ratio, representing the mean proportion of pathway genes found across iterations, and count, indicating how frequently a pathway was identified as enriched. To prioritize pathways, we ranked them in descending order based on the product of the average ratio and count, highlighting those that were both highly enriched. The number and biological relevance of the enriched pathways are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Number of identified pathways and keyword-matched related pathways for each method. Bold indicates the highest values in each case.

As shown in Table 3, NB1 identified the highest number of enriched pathways across all cases, followed by NLD, RWR, and LD. A high number of detected pathways suggest that a method consistently detects the same pathways in over 50% of the runs. However, this does not necessarily indicate that all detected pathways are biologically relevant. Neighborhood-based methods, such as NB1, tend to produce broader pathway lists, which may include unrelated or less relevant pathways. Because NB1 selects genes that are only one step away from the seed genes, the expanded network remains relatively constrained. In contrast, NB2, which includes two-step neighborhoods, introduces more distant connections, often leading to increased noise. Diffusion-based methods (LD, NLD, and RWR) use network connectivity and information propagation via transformation matrixes, making them more effective at retrieving biologically relevant genes. To assess the relevance of the identified pathways, we systematically evaluated how well they matched known biological terms using a keyword-based text mining approach. Specifically, we applied domain-relevant keywords to the names of pathways to quantify biological relevance.

For the ErbB family, we used keywords such as “ErbB”, “EGF”, “FGFR” and “HER2”. For the GSK3-related pathways, we included terms like “GSK3”, “Glycogen”, “PKB”, “PI3K”, “PDGF”, “insulin”, and “WNT”. Similarly, for the tumor protein p53 pathway, we used keywords such as “p53”, “TP53”, “PUMA”, “BCL”, “BH”, “cytoC” and “CASP”. We reported the percentage of keyword-matched pathways among all identified pathways, as well as within the top 10, and top 20 ranked pathways (see Table 3). NB1 identified the highest number of keyword-matched pathways (66), followed closely by NLD (60) in GO dataset. However, despite identifying fewer total pathways, LD achieved the highest proportion of relevant matches in both GO and KEGG datasets. This pattern is particularly evident when examining the top-ranked pathways: LD attained 90–100% keyword match rates in the top 10 and top 20, highlighting its strength in prioritizing biologically meaningful results.

A similar trend was observed for the p53-related pathways, where LD again showed the highest proportion of keyword-matched pathways, particularly in the GO dataset, with a 70% match rate among all identified pathways. Although NB1 identified more total pathways, its lower percentage of keyword-matching terms suggests a higher likelihood of including irrelevant pathways. In contrast, for GSK3-related pathways, RWR outperformed other methods in terms of relevance, achieving the highest percentage of keyword matches in both GO and KEGG datasets. Notably, NLD performed best in the top 10 ranked GO pathways, suggesting it may better capture the most relevant signals early in the ranking. While NB1 consistently recognized the highest number of pathways across all conditions, diffusion-based methods—particularly LD, NLD, and RWR—exhibited higher specificity, retrieving a greater proportion of biologically relevant pathways. This indicates that although neighborhood-based approaches like NB1 are more inclusive, they tend to introduce noise, whereas diffusion-based methods provide a more focused and precise enrichment of disease-relevant pathways. Table 3 summarizes these findings, comparing the number and percentage of keyword-matched pathways across methods, pathway types (ErbB, GSK3, p53), and sources (GO and KEGG). These results demonstrate the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity in pathway enrichment and underscore the importance of evaluating both the quantity and biological relevance of pathways.

Overall, these findings highlight the trade-offs among the evaluated methods. NB1 offers high sensitivity by identifying the largest number of pathways, but this comes with reduced specificity, as many pathways may not be directly relevant. In contrast, LD demonstrates strong precision, capturing fewer but more biologically relevant pathways, making it well-suited for applications where specificity is critical. RWR strikes a balance between sensitivity and specificity, while NLD performs similarly to NB1 but with slightly better filtering of irrelevant results. These distinctions suggest that NB1 is preferable for exploration analyses requiring broad pathway coverage, whereas LD or RWR are more appropriate when prioritizing biological relevance.

3.3. Top 10 Enriched Pathways and Their Biological Significance

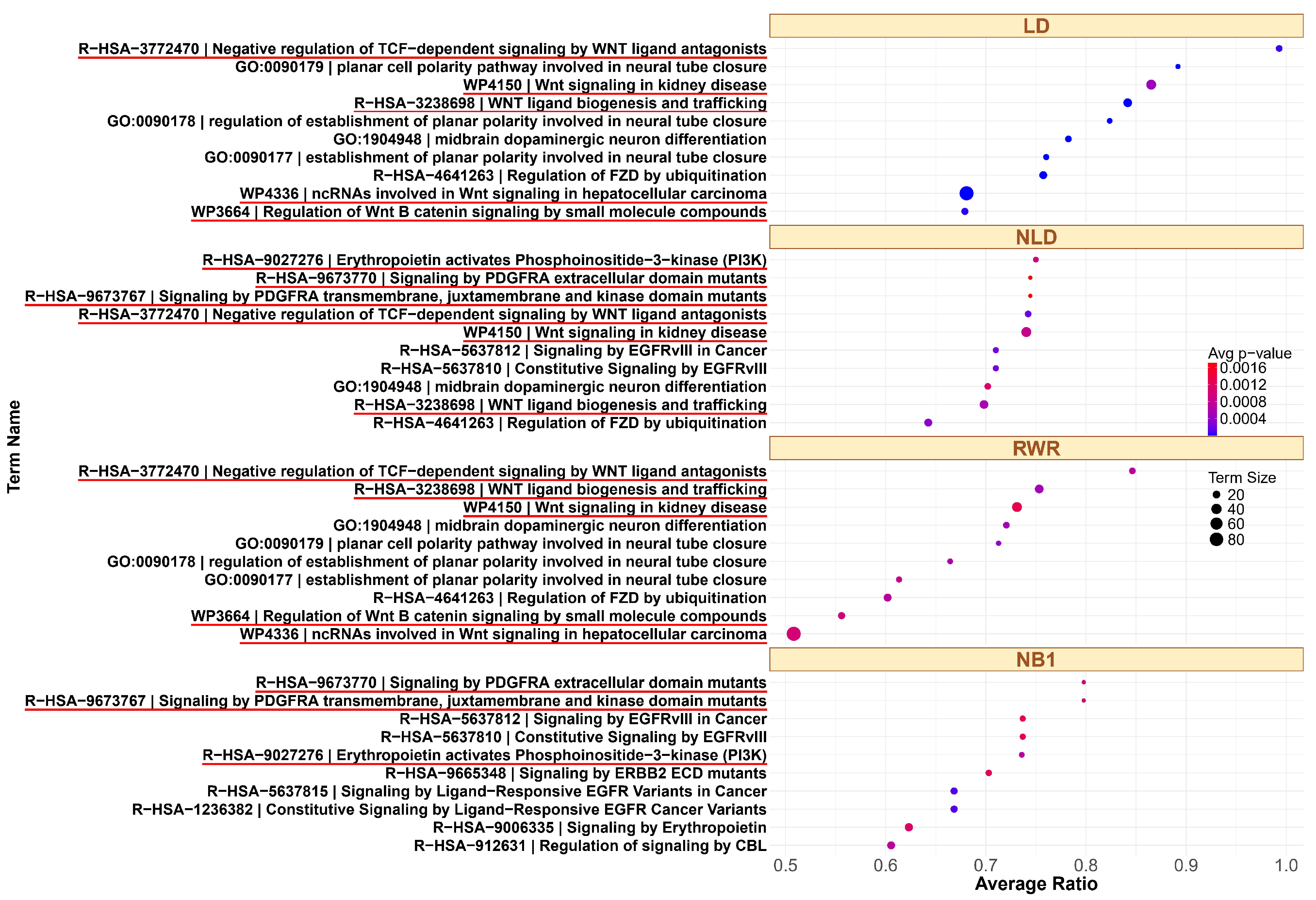

Based on the results presented in Table 1 and Figure 2, the three diffusion-based methods (LD, NLD, and RWR) exhibit comparable mean AUC values, with slight variations in average variance. Among them, LD yields the lowest mean AUPR, while NLD and RWR produce moderately higher values. Although NLD and RWR perform similarly in the GO dataset, NLD demonstrates better precision in the KEGG dataset, possibly due to its enhanced ability to capture pathway structure. Notably, LD displays the highest variance, suggesting while its performance is more variable, it can detect certain pathways very high precision. As shown in Table 3, LD effectively expands the set of candidate genes, leading to improved enrichment of relevant pathways, particularly for the ErbB and p53 families. In this case, LD exhibits superior pathway alignment results than other methods. In contrast, for the GSK3 family, RWR achieves the highest pathway relevance, followed by LD.

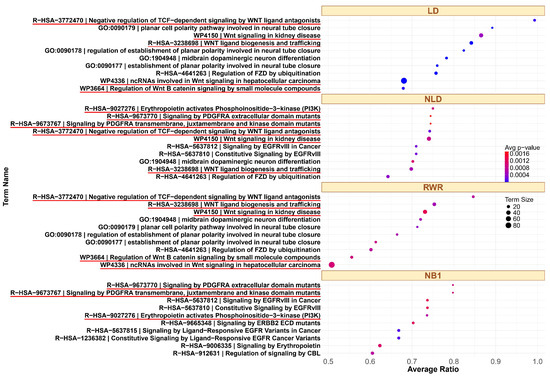

To further explore the biological relevance of these findings, we analyzed the top 10 enriched pathways identified by each method. For example, the top ranked pathways associated with the GSK3 signaling pathway from small seed gene sets are shown in Figure 4. The GSK3 pathway is highly interconnected and involves a large number of genes due to its integration with multiple signaling pathways in both GO and KEGG. GSK3 is inhibited through Akt/Protein Kinase B (PKB) activation via Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K) signaling, as well as by the WNT signaling pathway [51]. Additionally, PDGF (Platelet-Derived Growth Factor) signaling plays a critical role in modulating GSK3 activity. Activation of PDGF receptors (e.g., PDGFRA) triggers downstream pathways such as Akt, which phosphorylates and inhibits GSK3 [52]. LD and RWR identify overlapping top 10 pathways related to WNT. NLD and NB1 also identify similar pathways; however, NLD detects a greater number of pathways associated with WNT, PDGFRA, or PI3K. In contrast, NB1 does not detect any WNT-related pathways. The complete ranked list for all three families across different methods is provided in File S3. For the ErbB family, many enriched pathways included key members such as EGFR (ERBB1), ERBB2, ERBB3, and ERBB4. Among the top 10 pathways, NLD and NB1 identified the same sets in both GO and KEGG, including eight pathways related to ErbB and FGFR. Similarly, LD and RWR identify overlapping results, with all top 10 KEGG pathways and nine out of ten GO pathways related to ErbB signaling. For tumor protein p53 (TP53 or p53)—a gene frequently mutated in cancer and essential for regulating apoptosis, growth arrest, and senescence in response to cellular stress—our analysis revealed strong association from certain methods. p53 activates the PUMA gene in response to DNA damage, leading to production of PUMA-Alpha and PUMA-Beta proteins containing BH3 domains that promote apoptosis [53]. In the GO dataset, NLD and NB1 identified five p53-related pathways, while LD and RWR found a greater number of pathways directly associated with p53. In the KEGG dataset, LD identified the highest number of p53-related pathways, whereas other methods detected only a small subset.

Figure 4.

Top 10 enriched pathways in the GSK3 family in GO pathways, using LD, NLD, RWR, and NB1. The related pathways are highlighted with a red underline.

3.4. Survival Analysis and Biological Interpretation of Top-Ranked Genes

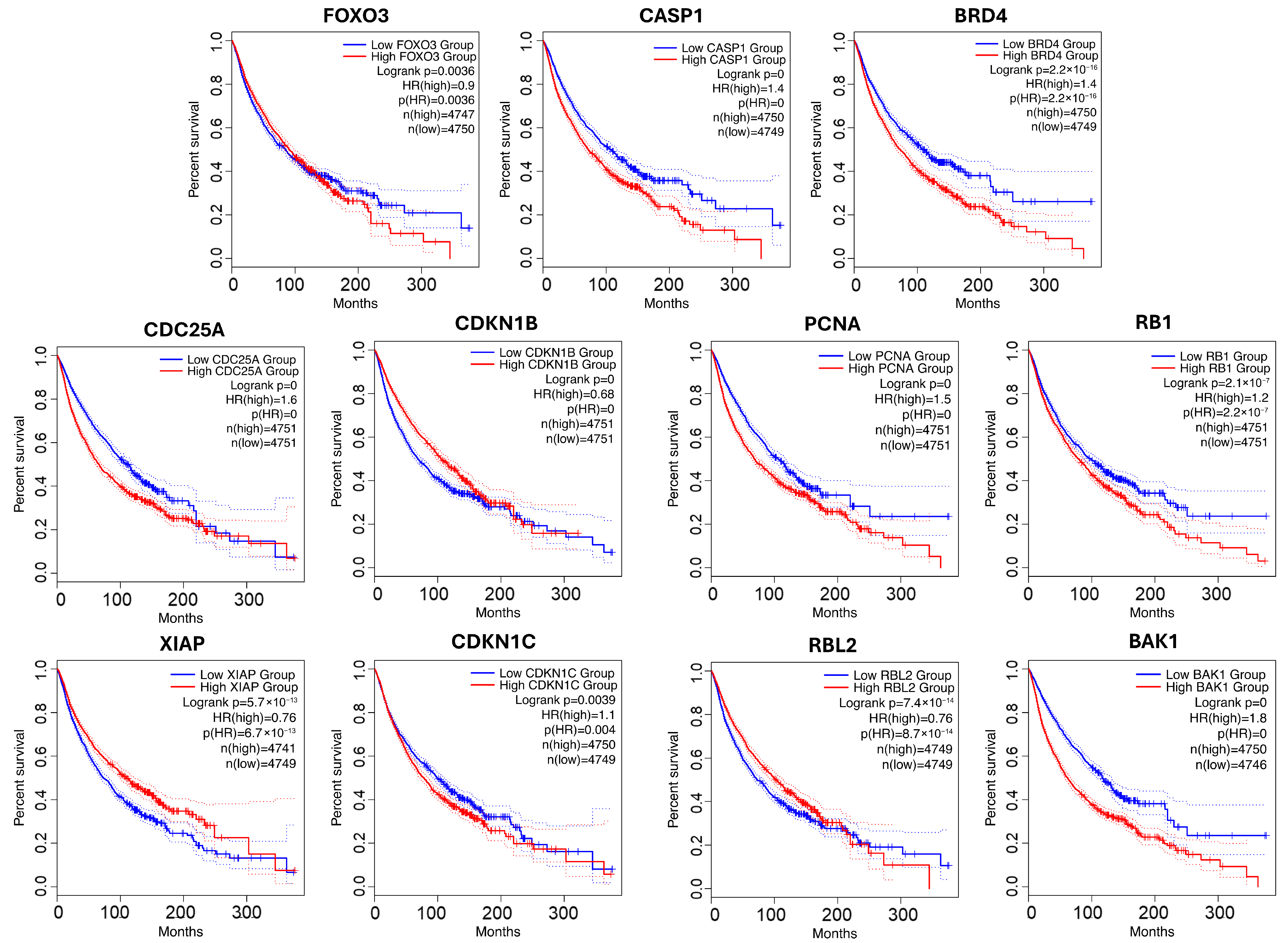

To assess the clinical relevance of genes identified through our network diffusion framework, we conducted a survival analysis using the log-rank test on top-ranked candidate genes derived from enriched pathways. Specifically, we applied the NLD method with 100 trials of randomly selected seed genes. Table 4 summarizes the 10 most frequently prioritized genes for each cancer pathway family—ErbB, GSK3, and p53—based on their occurrence in both GO and KEGG pathway databases. All survival analysis results for these top-ranked genes are provided in File S4. For each gene, the corresponding log-rank p-value indicates whether its expression level is significantly associated with patient survival. A smaller p-value (e.g., <0.05) suggests a strong association between gene expression and survival outcome, implying potential prognostic significance. Genes with p-values < 0.001 are particularly noteworthy, as they indicate robust survival-related signals and may be of high biomedical relevance.

Table 4.

Top 10 ranking genes with the highest frequency of occurrence across 100 iterations, excluding genes present in the original pathway data. Genes in bold have a log-rank p-value < 0.05.

Beyond survival analysis, the biological relevance of these genes is supported by literature evidence linking them to the corresponding pathways, as detailed in File S5. Some genes are already known to be associated with the three core cancer pathways, although they may not appear as core components in the canonical GO or KEGG pathway definitions. Instead, they are often found in related child terms or closely associated pathways. The remaining genes, which are not directly annotated in the core pathways, are of particular interest for further investigation as high-confidence, cancer-related genes with potential as therapeutic targets.

In ErbB pathway, multiple genes identified in both GO and KEGG pathways within the ErbB family showed strong associations with patient survival. In particular, PIK3R1, PIK3CD, CRKL, and SHC2 in GO and IGF1R, PDGFRA, and MET in KEGG exhibited highly significant p-values (all p < 1 × 10−7), reinforcing their established roles in cancer progression and treatment response. Although these genes were not among the specific seed inputs, they are recognized components of the KEGG ErbB signaling pathway (hsa04012). For instance, ERBB3 is not only part of hsa04012 but also appears in GO:0007173 (epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway) and GO:0038133 (ERBB2-ERBB3 signaling pathway), which are related to higher-level GO terms. Among the newly prioritized genes, JAK2 and RAC2 emerged as high-confidence candidates associated with the ErbB pathway. While not explicitly annotated in the core pathway, they were consistently discovered through network diffusion across multiple seed sets. In particular, RAC2 showed statistically significant association with patient survival (p < 0.05). It is known to be activated by ErbB-mediated signals and plays a role in modulating cell movement [54]. Although not explicitly annotated in KEGG ErbB signaling, RAC2 is known to be activated downstream of ErbB-mediated signals and regulates cytoskeletal reorganization and cell motility. Its statistically significant survival association (p < 0.05) highlights its potential role in cancer invasiveness and metastasis. JAK2 links growth factor receptor signaling to the JAK/STAT pathway, which is implicated in tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. Its recovery through diffusion suggests cross-talk between ErbB and JAK/STAT signaling that may contribute to oncogenic outcomes.

For GSK3 pathway, several genes demonstrated strong prognostic significance, including SRC, DVL3, ESR1, and PRKCD in KEGG, and WNT3A and SRC in GO (all p < 1 × 10−6). These genes are involved in key processes such as WNT signaling, PI3K/AKT signaling, and hormonal regulation—mechanisms critical to GSK3-mediated cellular functions. The recurrence of genes like SRC across both GO and KEGG further supports the robustness of network-based prioritization approach. Seven novel candidate genes were identified in the context of GSK3 signaling: FOXO3, GPC3, GNAQ, SRC, PTEN, PRKCD, and ESR1. Among these, SRC and GNAQ are known to interact with GSK3 via phosphorylation, influencing its activity [55,56,57,58]. FOXO3 is a transcription factor regulated by GSK3, FOXO3 which controls apoptosis and stress responses. Dysregulation of FOXO3 is associated with tumor progression and therapy resistance. GPC3, which is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan, modulates Wnt signaling, which directly interacts with GSK3 activity. Its involvement suggests an indirect but important role in Wnt/GSK3 regulatory loops in cancer. GNAQ, an upstream G-protein that can activate PKC and regulate GSK3 via phosphorylation, influences proliferation and migration. Both SRC and PRKCD are kinases that regulate GSK3 through phosphorylation, modulating pathways such as PI3K/AKT and apoptosis. PTEN is a tumor suppressor that antagonizes PI3K/AKT signaling, thereby indirectly regulating GSK3 activity. Its frequent recovery reflects its central role in signaling cross-talk. ESR1, an estrogen receptor α, is regulated by GSK3-mediated phosphorylation, affecting hormone-dependent cancer signaling and highlighting GSK3’s role in endocrine-related tumors. FOXO3, PTEN, and PRKCD regulate GSK3 through distinct mechanisms, affecting cell fate, growth, and survival [59,60,61,62,63]. Additionally, GPC3 modulates Wnt signaling [64], and ESR1 is regulated by GSK3 through phosphorylation, impacting estrogen signaling and downstream gene expression [65,66].

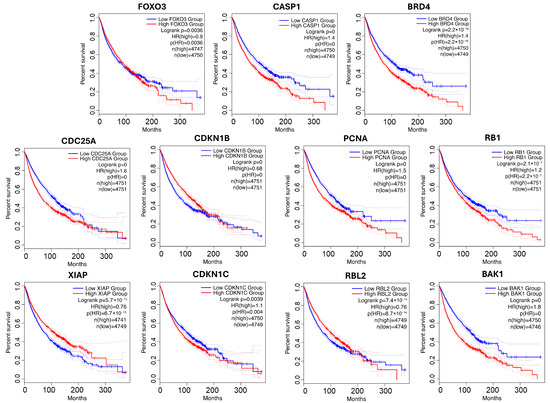

For p53 pathway, a substantial number of genes associated with the p53 pathway displayed highly significant survival correlations. In particular, CDK2, MYC, CASP1, and BRD4 in GO, along with CDC25A, CDKN1B, PCNA, and BAK1 in KEGG, had log-rank p-values < 1 × 10−16. These genes are well-established regulators of the cell cycle, apoptosis, and DNA repair, aligning well with p53-mediated tumor suppression. In total, eleven novel genes were identified in the p53 signaling pathway: FOXO3, CASP1, and BRD4 in GO, and CDC25A, CDKN1B, PCNA, RB1, XIAP, CDKN1C, RBL2, and BAK1 in KEGG. FOXO3, CASP1, BAK1, BRD4, CDKN1B, and CDKN1C support p53 functions related to apoptosis and tumor suppression [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74] by promoting cell death or cell cycle arrest. BRD4 is a chromatin regulator that modulates transcriptional programs downstream of p53. CDC25A and PCNA are key players in DNA damage response and cell cycle arrest—key processes regulated by p53 [75,76,77]. Lastly, RB1 and RBL2 are tumor suppressors that intersect with p53 pathway signaling via cell cycle regulation and tumor suppression [78,79]. XIAP is an inhibitor of apoptosis that suppresses p53 function by promoting its degradation or blocking transcriptional activity, representing a negative regulatory node within the pathway [80,81].

To visualize their clinical relevance, the survival outcomes for patients stratified by high versus low gene expression are presented in Figure 5. In all cases, significant survival differences were observed (p < 0.005), highlighting the prognostic value of these candidates and underscoring their potential for further biological validation. Many of the newly identified high-confidence genes recovered by our network diffusion approach are functionally relevant, participating in well-known signaling cross-talk (e.g., ErbB–JAK/STAT, GSK3–Wnt/PI3K, p53–cell cycle/apoptosis). These findings reveal additional regulatory layers that are not always captured in curated pathway databases, highlighting the strength of NLD in uncovering biologically important yet incompletely annotated genes.

Figure 5.

Survival analysis for novel genes from p53-related pathway. Low-expression groups are shown in blue; high-expression groups are shown in red. Dotted lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

Cancer is a common and life-threatening disease that often leads to tumor development and death. Identifying cancer-related genes plays a vital role in improving therapeutic strategies and drug discovery. Although gene expression data for cancer has become increasingly available, many datasets produce only a limited number of significant genes, making them less suitable for traditional pathway enrichment analysis. To overcome this issue, network-based methods—particularly those using PPI networks—have been introduced to improve enrichment performance. One of the main challenges in pathway enrichment lies in measuring how well the input gene set overlaps with known biological pathways and evaluating the method’s ability to find missing but functionally relevant genes.

This work outlines a network diffusion-based framework as an effective strategy for expanding gene lists to improve functional pathway enrichment, as many studies commonly use PPI networks with one- or two-step extensions from a limited set of known context-specific genes (our neighborhood-based approach) to identify key functional pathways. Our approach systematically benchmarks normalized Laplacian diffusion (NLD) under low-input conditions, where conventional methods often lose sensitivity. NLD achieves high accuracy even with minimal seed information, and the resulting candidate genes show strong survival associations, underscoring the framework’s robustness and novelty. To avoid overstating novelty, we emphasize that our approach does not discover entirely new pathways, but rather identifies genes present in the PPI network that are not yet annotated in curated pathway databases. These findings should therefore be interpreted as pathway extensions rather than de novo pathway discovery. To evaluate the effectiveness of network diffusion, we conducted a systematic assessment of three network diffusion-based methods across various seed percentages and multiple randomizations for pathways from GO Biological Processes and KEGG pathways. Our results consistently demonstrated that network diffusion techniques achieved significantly higher pathway alignment performance, as measured by AUC and AUPR, compared to the neighborhood-based approach. This advantage was particularly evident when using a small subset of genes as seed nodes, where network diffusion more effectively reconstructed entire pathways. Among the diffusion approaches, NLD consistently exhibited the highest performance across all tested conditions. Unlike other methods, NLD (normalized Laplacian diffusion) accounts for node degree, making it more stable when only a few seed genes are available. As a result, it recovers pathways more effectively, produces consistent gene rankings, and identifies new cancer-related genes supported by survival data and literature. In contrast, other approaches tend to be sensitive to the size and distribution of the initial seed set. By correcting for node degree and reducing bias toward highly connected nodes, NLD offers a more balanced and robust diffusion strategy.

To further assess the practical implications, we evaluated pathway enrichment performance using only 10% of genes from three key cancer biology pathways: ErbB, GSK3, and p53. Over 100 iterations, we ensured fair comparisons by maintaining equal seed sizes across methods. The results showed that NB1 identified the highest number of pathways but included many irrelevant terms. In contrast, NLD detected a similar number of pathways while filtering out unrelated terms, leading to more precise enrichment outcomes. To further quantify performance, we applied text mining analysis to count enriched pathways related to each family and calculate precision percentages for each method. This further confirmed that diffusion-based methods (NLD, LD, and RWR) improved the identification of cancer-related pathways in both GO and KEGG datasets, reinforcing the benefits of network diffusion.

Many of the top-ranked genes identified by the NLD method, which contributed significantly to the enrichment results, consistently reappeared across multiple iterations—even when different input gene sets were used. This suggests that these genes may play a central role in the underlying biology of the pathways. Our analysis revealed that some recurrent genes identified by our methods are not annotated in existing pathway databases, highlighting a known discrepancy between protein-level, PPI networks and pan-level pathway databases such as GO and KEGG, which include RNA, DNA, and small-molecule signaling. This discrepancy partly arises because PPI data in STRING may be biased toward experiments referencing known pathways, while pathway annotations often reflect protein-level experimental results. As a result, some top-ranked genes in GO pathways also appear in KEGG pathways due to their PPI network connections. For example, LRP5 is annotated in the KEGG Wnt signaling pathway and interacts with WNT3A in STRING, but it is absent from the corresponding GO pathway. This illustrates that network-based approaches can reveal genes functionally associated with a pathway, even when they are missing from certain databases. To explore their potential relevance, we further analyzed their biological roles, focusing particularly on cancer-related functions and their associations with patient survival using TCGA cancer models.

Beyond literature co-mention, several NLD-identified genes demonstrate functional relevance within key signaling pathways, highlighting the biological interpretability of the diffusion-based prioritization. In the ErbB signaling pathway, NLD not only recovered known components but also identified JAK2 and RAC2 as novel, high-confidence candidates. RAC2—activated downstream of ErbB receptors—regulates cytoskeletal reorganization and cell motility, key processes in cancer invasiveness and metastasis. JAK2 connects growth factor receptor signaling to the JAK/STAT cascade, suggesting cross-talk between ErbB and JAK/STAT pathways that may contribute to oncogenic signaling and therapeutic resistance. In the GSK3 signaling pathway, NLD prioritized seven novel candidates (FOXO3, GPC3, GNAQ, SRC, PTEN, PRKCD, and ESR1). SRC and GNAQ regulate GSK3 through phosphorylation, influencing downstream pathways that control proliferation and migration. FOXO3, a GSK3-regulated transcription factor, governs apoptosis and stress responses and is frequently dysregulated in therapy-resistant cancers. GPC3 modulates Wnt signaling, indirectly affecting GSK3 activity, while PTEN and PRKCD act as modulators of GSK3-driven apoptotic signaling. ESR1 (estrogen receptor α) is phosphorylated by GSK3, linking GSK3 regulation to endocrine-related tumor progression. Together, these findings reveal a complex network of interactions that extend beyond canonical GSK3 components. In the p53 signaling pathway, NLD identified eleven candidate genes, including FOXO3, CASP1, BRD4, CDC25A, CDKN1B, PCNA, RB1, XIAP, CDKN1C, RBL2, and BAK1. Many of these (FOXO3, CASP1, BAK1, BRD4, CDKN1B, CDKN1C) reinforce p53-mediated apoptotic and tumor-suppressive functions, while BRD4 regulates chromatin accessibility and transcription downstream of p53. CDC25A and PCNA participate in DNA damage response and checkpoint control, RB1 and RBL2 enforce cell-cycle inhibition, and XIAP functions as a negative regulator that suppresses p53 activity. Collectively, these results show that NLD effectively recovers canonical p53 effectors while revealing auxiliary regulators that fine-tune p53 pathway fidelity. Although the present validation is based on in silico analyses and prior studies, these findings consistently link NLD-derived genes to key oncogenic mechanisms across pathways.

All in all, this study highlights the advantages of network diffusion for functional pathway discovery, demonstrating its potential to refine context-specific gene sets and enhance biomedical research. Robustness was ensured by repeating the diffusion with multiple random seed sets and aggregating results. High-confidence genes and pathways were those consistently prioritized across runs, with stability further supported by biological relevance, survival analysis and literature evidence. Our findings suggest that NLD-based diffusion is a powerful tool for aligning PPI-derived signals with curated pathways and for highlighting candidate genes that extend beyond current GO/KEGG annotations, with broad applications in biology, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic target identification. In practice, where the proportion of available genes for enrichment analysis is often unknown, robust pathway discovery methods are essential. Network diffusion techniques excel in handling incomplete gene sets, offering superior pathway reconstruction and enrichment accuracy. Future research could focus on integrating biological constraints or context-specific weighting into diffusion, examining how network structure influences performance, and applying the framework to patient-specific, edge-weighted networks to better capture biological context and reduce bias from high-degree nodes. Additionally, examining how network structures influence diffusion performance could provide deeper insights into optimizing pathway enrichment methodologies. Although this study focused on a primary dataset, the approach is generalizable and can be applied to other cohorts such as TCGA or ICGC. Validation on such independent datasets will strengthen the robustness and translational potential of our findings. Finally, experimental studies in cell or animal models will be an important next step; given the small set of high-confidence candidates identified, such efforts may be feasible with modest resources and carry a high likelihood of success.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a network diffusion-based framework as an effective strategy for expanding gene sets to enhance functional pathway enrichment analysis results. The alignment performance demonstrates that the pathway obtained from the NLD method showed superior agreement to annotated pathways compared to other propagation approaches across diverse conditions, as evaluated by both AUC and AUPR metrics using GO and KEGG pathways. Enrichment analysis using a limited set of genes from three cancer-related pathways—ErbB, GSK3, and p53—as seed nodes, yielding more precise and consistent alignment with curated pathways compared to the neighborhood-based method. Moreover, the top-ranked genes identified by the NLD approach were supported by biological literature and showed significant associations with patient survival in TCGA cancer datasets. Collectively, these findings highlight the potential of NLD-based diffusion, not only for robust pathway discovery under sparse input conditions but also for uncovering clinically relevant genes, with implications for biomarker and therapeutic target development. In addition, this framework provides a valuable means of pathway extension by systematically incorporating novel candidate genes into existing pathway annotations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/computation13110266/s1 , File S1: Characteristics of GO and KEGG pathways in PPI network; File S2: PPI connection of ErbB signaling, p53-mediated apoptosis, and GSK3 signaling pathway genes.; File S3: Top 10 enriched pathways in all cases; File S4: Overall survival analysis plots for the top 10 genes across all cases; File S5: Biological evidence supporting the relationship between top-ranked genes and their associated pathways [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.J., A.S. and K.P.; methodology, P.J., A.S. and K.P.; software, P.J.; validation, P.J., A.S. and K.P.; formal analysis, P.J., A.S. and K.P.; investigation, P.J., A.S. and K.P.; resources, P.J., A.S. and K.P.; data curation, P.J., A.S. and K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.J.; writing—review and editing, P.J., A.S. and K.P.; visualization, P.J., A.S. and K.P.; supervision, A.S. and K.P.; project administration, A.S. and K.P.; funding acquisition, P.J., A.S. and K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project is supported by the Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University. This research budget was allocated by National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), and King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok (Project no. KMUTNB-FF-67-B-24).

Data Availability Statement

All data and R code used in this study are publicly available and can be accessed through https://github.com/panisajan/Network.Diffusion_PathwayEnrich (accessed on 12 June 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and valuable suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC | Area under the ROC curve |

| AUPR | Area under precision–recall curve |

| ErbB | Erythroblastic Leukemia Viral Oncogene Homolog |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LD | Laplacian kernel diffusion |

| NB1 | One-step neighborhood |

| NB2 | Two-steps neighborhood |

| NLD | Normalized Laplacian kernel diffusion |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| RWR | Random walk with restart |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

References

- Tsimberidou, A.M.; Fountzilas, E.; Bleris, L.; Kurzrock, R. Transcriptomics and solid tumors: The next frontier in precision cancer medicine. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 84, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pattnaik, A.; Sahoo, S.S.; Stone, E.G.; Zhuang, Y.; Benton, A.; Tajmul, M.; Chakravorty, S.; Dhawan, D.; Nguyen, M.A. Unbiased discovery of cancer pathways and therapeutics using Pathway Ensemble Tool and Benchmark. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisov, N.; Sorokin, M.; Tkachev, V.; Garazha, A.; Buzdin, A. Cancer gene expression profiles associated with clinical outcomes to chemotherapy treatments. BMC Med. Genom. 2020, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, P.; Sirota, M.; Butte, A.J. Ten years of pathway analysis: Current approaches and outstanding challenges. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimand, J.; Isserlin, R.; Voisin, V.; Kucera, M.; Tannus-Lopes, C.; Rostamianfar, A.; Wadi, L.; Meyer, M.; Wong, J.; Xu, C. Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data using g: Profiler, GSEA, Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 482–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Shao, X.; Li, Y.; Gihu, R.; Xie, H.; Zhou, J.; Yan, H. Targeting signaling pathway networks in several malignant tumors: Progresses and challenges. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 675675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. ErbB receptors and cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1652, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shojaie, A.; Michailidis, G. Analysis of gene sets based on the underlying regulatory network. J. Comput. Biol. 2009, 16, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shojaie, A.; Michailidis, G. Network enrichment analysis in complex experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2010, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Suratanee, A.; Plaimas, K. Heterogeneous network model to identify potential associations between plasmodium vivax and human proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suratanee, A.; Buaboocha, T.; Plaimas, K. Prediction of human-plasmodium vivax protein associations from heterogeneous network structures based on machine-learning approach. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2021, 15, 11779322211013350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevimoglu, T.; Arga, K.Y. The role of protein interaction networks in systems biomedicine. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2014, 11, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Ruan, J. Network-based pathway enrichment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine, Shanghai, China, 18–21 December 2013; pp. 218–221. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wei, J.; Ruan, J. Pathway enrichment analysis with networks. Genes 2017, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, J.; Li, H.; Fu, J.; Liu, L.; Xing, Y.; Li, X.; Shen, H.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y. Construction and analysis of the protein-protein interaction network related to essential hypertension. BMC Syst. Biol. 2013, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handen, A.; Ganapathiraju, M.K. LENS: Web-based lens for enrichment and network studies of human proteins. BMC Med. Genom. 2015, 4 (Suppl. 4), S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Ma, J.; Wan, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cen, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Z. HGNNPIP: A Hybrid Graph Neural Network framework for Protein-protein Interaction Prediction. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janyasupab, P.; Singhanat, K.; Warnnissorn, M.; Thuwajit, P.; Suratanee, A.; Plaimas, K.; Thuwajit, C. Identification of Tumor Budding-Associated Genes in Breast Cancer through Transcriptomic Profiling and Network Diffusion Analysis. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagulkoo, P.; Suratanee, A.; Plaimas, K. Immune-related protein interaction network in severe COVID-19 patients toward the identification of key proteins and drug repurposing. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.I.; Hwang, S.; Kincaid, R.P.; Sullivan, C.S.; Lee, I.; Marcotte, E.M. RIDDLE: Reflective diffusion and local extension reveal functional associations for unannotated gene sets via proximity in a gene network. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovász, L. Random walks on graphs. In Combinatorics, Paul Erdos is Eighty; János Bolyai Mathematical Society: Budapest, Hungary, 1993; Volume 2, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.-Y.; Yang, H.-J.; Faloutsos, C.; Duygulu, P. Automatic multimedia cross-modal correlation discovery. In Proceedings of the tenth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Seattle, WA, USA, 22–25 August 2004; pp. 653–658. [Google Scholar]

- Suratanee, A.; Plaimas, K. DDA: A novel network-based scoring method to identify disease-disease associations. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2015, 9, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangmanussukum, P.; Kawichai, T.; Suratanee, A.; Plaimas, K. Heterogeneous network propagation with forward similarity integration to enhance drug–target association prediction. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdeolivas, A.; Tichit, L.; Navarro, C.; Perrin, S.; Odelin, G.; Levy, N.; Cau, P.; Remy, E.; Baudot, A. Random walk with restart on multiplex and heterogeneous biological networks. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smola, A.J.; Kondor, R. Kernels and regularization on graphs. In Learning Theory and Kernel Machines, Proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference on Learning Theory and 7th Kernel Workshop, COLT/Kernel 2003, Washington, DC, USA, 24–27 August 2003; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, M.; Audibert, J.-Y.; von Luxburg, U. Graph laplacians and their convergence on random neighborhood graphs. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2007, 8, 1325–1368. [Google Scholar]

- Janyasupab, P.; Suratanee, A.; Plaimas, K. Network diffusion with centrality measures to identify disease-related genes. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 2909–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picart-Armada, S.; Barrett, S.J.; Willé, D.R.; Perera-Lluna, A.; Gutteridge, A.; Dessailly, B.H. Benchmarking network propagation methods for disease gene identification. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1007276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagulkoo, P.; Suratanee, A.; Plaimas, K. Network-based methods with heterogeneous data to identify severe COVID immune-related genes. In Proceedings of the 2022 26th International Computer Science and Engineering Conference (ICSEC), Sakon Nakhon, Thailand, 21–23 December 2022; pp. 334–339. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M.; Hwang, T.; Kuang, R. Prioritizing disease genes by bi-random walk. In Proceedings of the Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 29 May–1 June 2012; pp. 292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Cowen, L.; Ideker, T.; Raphael, B.J.; Sharan, R. Network propagation: A universal amplifier of genetic associations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksander, S.A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.M.; Drabkin, H.J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N.L. The gene ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, iyad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D587–D592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, G.O. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D258–D261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, H.; Carlson, M.; Falcon, S.; Li, N. AnnotationDbi: Manipulation of SQLite-Based Annotations in Bioconductor, R Package Version 1.1; Bioconductor. 2021. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/AnnotationDbi.html (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M.; Falcon, S.; Pages, H.; Li, N. org. Hs. eg. db: Genome Wide Annotation for Human, R Package Version 3.2; Bioconductor. 2019. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/org.Hs.eg.db.html (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M.; Falcon, S.; Pages, H.; Li, N. GO.db: A Set of Annotation Maps Describing the Entire Gene Ontology. Bioconductor. 2019, 3. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/GO.db.html (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Manjang, K.; Tripathi, S.; Yli-Harja, O.; Dehmer, M.; Emmert-Streib, F. Graph-based exploitation of gene ontology using GOxploreR for scrutinizing biological significance. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. KEGG: New perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D353–D361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenenbaum, D.; Maintainer, B. KEGGREST: Client-Side REST Access to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), R Package Version 1.36.0; Bioconductor. 2021. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/KEGGREST.html (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chandraprasad, M.S.; Dey, A.; Swamy, M.K. Introduction to cancer and treatment approaches. In Paclitaxel; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S. The STRING database in 2023: Protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Jost, J. On the spectrum of the normalized graph Laplacian. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2008, 428, 3015–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Z. Network representation learning via improved random walk with restart. Knowl. Based Syst. 2023, 263, 110255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolberg, L.; Raudvere, U.; Kuzmin, I.; Adler, P.; Vilo, J.; Peterson, H. g: Profiler—Interoperable web service for functional enrichment analysis and gene identifier mapping (2023 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W207–W212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milacic, M.; Beavers, D.; Conley, P.; Gong, C.; Gillespie, M.; Griss, J.; Haw, R.; Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; May, B. The reactome pathway knowledgebase 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D672–D678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Balcı, H.; Hanspers, K.; Coort, S.L.; Martens, M.; Slenter, D.N.; Ehrhart, F.; Digles, D.; Waagmeester, A.; Wassink, I. WikiPathways 2024: Next generation pathway database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D679–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Kang, B.; Li, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W556–W560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, J.N.; Collisson, E.A.; Mills, G.B.; Shaw, K.R.; Ozenberger, B.A.; Ellrott, K.; Shmulevich, I.; Sander, C.; Stuart, J.M. The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskas, D.; Ling, L.S.; Woodgett, J.R. Does GSK-3 provide a shortcut for PI3K activation of Wnt signalling? F1000 Biol. Rep. 2010, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villenfagne, L.; Sablon, A.; Demoulin, J.-B. PDGFRA K385 mutants in myxoid glioneuronal tumors promote receptor dimerization and oncogenic signaling. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, L. PUMA, a potent killer with or without p53. Oncogene 2008, 27, S71–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosa, M.S.; Lopez-Haber, C.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Lemmon, M.A.; Busillo, J.M.; Luo, J.; Benovic, J.L.; Klein-Szanto, A.; Yagi, H. Identification of the Rac-GEF P-Rex1 as an essential mediator of ErbB signaling in breast cancer. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goc, A.; Al-Husein, B.; Katsanevas, K.; Steinbach, A.; Lou, U.; Sabbineni, H.; DeRemer, D.L.; Somanath, P.R. Targeting Src-mediated Tyr216 phosphorylation and activation of GSK-3 in prostate cancer cells inhibit prostate cancer progression in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCubrey, J.A.; Steelman, L.S.; Bertrand, F.E.; Davis, N.M.; Sokolosky, M.; Abrams, S.L.; Montalto, G.; D’Assoro, A.B.; Libra, M.; Nicoletti, F. GSK-3 as potential target for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, L.M.; Chattopadhyay, M.; Li, Y.; Scarlata, S.; Lin, R.Z. Gαq binds to p110α/p85α phosphoinositide 3-kinase and displaces Ras. Biochem. J. 2006, 394, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Ballou, L.M.; Lin, R.Z. Phospholipase C-independent activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β and C-terminal Src kinase by Gαq. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 52432–52436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.; Borges, D.d.P.; Kimberly, A.; Martins Neto, F.; Oliveira, A.C.; Sousa, J.C.d.; Nogueira, C.D.; Carneiro, B.A.; Tavora, F. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Beta Expression Correlates with Worse Overall Survival in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer—A Clinicopathological Series. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 621050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.F.; van den Bosch, M.T.; Hunter, R.W.; Sakamoto, K.; Poole, A.W.; Hers, I. Dual regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) α/β by protein kinase C (PKC) α and Akt promotes thrombin-mediated integrin αIIbβ3 activation and granule secretion in platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 3918–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z. The GSK3β pathway in optic nerve regeneration. Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 2, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloedjes, T.A.; de Wilde, G.; Maas, C.; Eldering, E.; Bende, R.J.; van Noesel, C.J.; Pals, S.T.; Spaargaren, M.; Guikema, J.E. AKT signaling restrains tumor suppressive functions of FOXO transcription factors and GSK3 kinase in multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 4151–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lu, G.; Su, X.; Tang, C.; Li, H.; Xiong, Z.; Leung, C.-K.; Wong, M.-S.; Liu, H.; Ma, J.-L. Pten-mediated Gsk3β modulates the naïve pluripotency maintenance in embryonic stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.H.; Shi, W.; Xiang, Y.-Y.; Filmus, J. The loss of glypican-3 induces alterations in Wnt signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 2116–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisouard, J.; Medunjanin, S.; Hermani, A.; Shukla, A.; Mayer, D. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 protects estrogen receptor α from proteasomal degradation and is required for full transcriptional activity of the receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007, 21, 2427–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medunjanin, S.; Hermani, A.; De Servi, B.; Grisouard, J.; Rincke, G.; Mayer, D. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 interacts with and phosphorylates estrogen receptor α and is involved in the regulation of receptor activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 33006–33014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]