Abstract

This article formulates and analyzes a discrete-time Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) coinfection model with latent reservoirs. We consider that the HTLV-I infect the CDT cells, while HIV-1 has two classes of target cells—CDT cells and macrophages. The discrete-time model is obtained by discretizing the original continuous-time by the non-standard finite difference (NSFD) approach. We establish that NSFD maintains the positivity and boundedness of the model’s solutions. We derived four threshold parameters that determine the existence and stability of the four equilibria of the model. The Lyapunov method is used to examine the global stability of all equilibria. The analytical findings are supported via numerical simulation. The impact of latent reservoirs on the HIV-1 and HTLV-I co-dynamics is discussed. We show that incorporating the latent reservoirs into the HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection model will reduce the basic HIV-1 single-infection and HTLV-I single-infection reproductive numbers. We establish that neglecting the latent reservoirs will lead to overestimation of the required HIV-1 antiviral drugs. Moreover, we show that lengthening of the latent phase can suppress the progression of viral coinfection. This may draw the attention of scientists and pharmaceutical companies to create new treatments that prolong the latency period.

MSC:

37M05; 39A10; 65L12; 92D25; 92D30

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, many scientists and researchers from the disciplines of mathematics, biology, and medicine have been interested in modeling the dynamics of viral infection within the host. Mathematical modeling of viral infection has a long history of helping to provide insight that is difficult to obtain through pure experiments. Examples of viral single-infection that have been modeled and studied are as follows: (i) chronic viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) [1], human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) [2], hepatitis B virus (HBV) [3] and hepatitis C virus (HCV) [4], (ii) respiratory viral infections such as influenza A virus (IAV) [5] and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [6,7], (iii) vector-borne viral infections such as dengue virus [8], chikungunya virus [9] and Zika virus [10]. The in-host viral coinfections were also modeled in recent years such as Zika/dengue [11], HIV-1/HTLV-I [12,13], IAV/SARS-CoV-2 [14,15], SARS-CoV-2/HIV-1 [16], SARS-CoV-2/HTLV-I [17], HIV-1/HCV [18] and HIV-1/HBV [19]. HIV-1 and HTLV-I are two dangerous retroviruses that attack the central component of the immune system, CDT cells and can cause chronic diseases. HIV-1 causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), while HTLV-I causes HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) and adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) diseases. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and B cells play important roles in the immune response against viral infection. CTLs attack and kill the viral-infected cells, while B cells produce antibodies to neutralize viruses.

Since formulating the basic model of HIV-1 single-infection in [1], many modifications and developments have been made to make the model more accurate in describing the dynamics of the virus within the host. Some biological factors have been taken into account such as: (i) time delay [20,21], (ii) drug therapies [20,22], (iii) CTL immunity [1,23], (iv) antibody immunity [24], (v) reaction–diffusion [25], (vi) stochastic effects [26], and (vii) two target cells (CD4T cells and macrophages) [22,27,28,29].

Latent HIV-1 reservoirs are considered a significant obstacle to HIV-1 elimination [30]. Latent HIV-1-infected cells can be activated after a period of time and then become viral production cells when drug therapies are stopped. These cells contains the HIV-1 virions; however, they do not produce them until they are stimulated. This fact causes an escapement of latent HIV-1-infected cells from the immune response. HIV-1 dynamics models with latent infected cells were developed in several works (see e.g., [23,26,30,31,32].

Stilianakis and Seydel [2] formulated a mathematical model for in-host HTLV-I dynamics. After that, several HTLV-I dynamics models were developed. HTLV-I infection models with CTL immune response were addressed in [33,34,35,36]. HTLV-I infection models have been incorporated with intracellular delay in [37], and with immune response delay in [35,37]. Reaction-diffusion HTLV-I infection models were investigated in [34].

HIV-1 and HTLV-1 share the methods of transmission between people through sexual relationships, infected sharp objects, blood transfusions and organ transplantation. Therefore, some nonlinear continuous-time models were recently formulated that describe the dynamics of HIV-1 and HTLV-1 coinfection in-host [12,13]. In [12,13], it was assumed that HIV-1 has one type of target cells, CD4T cells. In fact, HIV-1 can also infect macrophages [31]. In [38], an HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection model was formulated by considering two types of target cells for HIV-1, CD4T cells and macrophages:

where x, y, w, z, v and u denote the concentrations of uninfected CD4T cells, HIV-1-infected CD4T cells, uninfected macrophages, HIV-1-infected macrophages, HIV-1 particles and HTLV-I-infected CD4T cells, respectively. Model (1) was discretized by the NSFD method in [39]. Global stability of the discretized model was established using the Lyapunov technique.

In model (1), latent HIV-1 and HTLV-I reservoirs were not included. Therefore, model (1) has been extended in [40] by including three additional populations, latent HIV-1-infected CD4T cells (g), latent HIV-1-infected macrophages (s) and latent HTLV-I-infected CD4T cells (q) as:

where the latent HIV-1-infected CD4T cells, latent HIV-1-infected macrophages and latent HTLV-I-infected CD4T cells are activated by rates , and , respectively, while they die at rates , and , respectively.

We note that model (2) is nonlinear continuous-time, and its exact analytical solution is unknown; therefore, discretization is unavoidable. Further, blood measurements from infected patients can only be available at discrete-time instants. As a result, an adequate discretization approach has to be chosen such that the basic and global properties of the original model is maintained. Mickens [41] introduced a non-standard finite difference (NSFD) scheme for solving different types of differential equations. NSFD was successfully utilized in discretizing several within-host virus dynamics models [42,43,44,45]. HIV-1 continuous-time models were discretized via the NSFD approach in [46,47,48,49]. A stability analysis of a discrete HIV-1 dynamics model with the Beddington–DeAngelis incidence and cure rate was studied in [47]. In [49], the global stability of discrete HIV-1 dynamics models with three classes of HIV-1-infected cells was studied. In [48], the HIV-1 dynamics model given by PDEs was discretized via the NSFD method. The Lyapunov method was used to prove the global stability of equilibria.

We mention that all mathematical models for HTLV-I single-infection and HIV-1/HTLV-I coinfection presented in the literature are given as continuous-time systems. The only exception is our recent paper [39], where a discrete HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection model is considered. In [39], the presence of latent reservoirs has not been modeled. The aim of the present article is to use the NSFD method to discretize an HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection model with latent reservoirs. We first establish the positivity and ultimate boundedness of the discrete-time model’s solutions, then calculate all equilibria and deduce their existence conditions. We examine the global stability of the four equilibria using the Lyapunov approach. We present some numerical simulations to clarify the theoretical results. We discuss the impact of latent reservoirs on the HIV-1 and HTLV-I co-dynamics.

2. The Discrete-Time Model

Classical numerical methods, such as Euler, Runge–Kutta and others, when used in solving nonlinear differential equations, suffer from numerical instability and bias when large step sizes are used in the numerical simulation [50]. In this situation, these numerical methods may provide non-physical solutions and can produce ‘false’ or ‘spurious’ fixed points, which are not fixed points of the original continuous-time model [51,52]. The NSFD method preserves the essential qualitative features of the original continuous-time model such as equilibria, positivity, boundedness and global behaviors of solutions independently of the selected step-size.

3. Preliminaries

Let and and define the regions

Lemma 1.

Proof.

Since all parameters of model (2) are positive and the initial values are also positive, then by induction we obtain and for all .

It follows that

Using Lemma 2.2 in [53], we obtain

Consequently, and . Define a sequence as:

Hence

Hence

Lemma 2.2 in [53] gives

Then, . From Equation (9), we obtain

Hence

By induction, we obtain

Consequently, Therefore, converge to as □

4. Equilibria

Here, we calculate the model’s equilibria and deduce their existence conditions.

Lemma 2.

(1) Infection-free equilibrium , which always exists.

(2) Chronic HIV-1 single-infection equilibrium exists when

(3) Chronic HTLV-I single-infection equilibrium exists when .

(4) Chronic HIV-1/HTLV-I coinfection infection equilibrium exists when and

Proof.

Any equilibrium satisfies

Now substituting in Equation (29), we obtain

There are two solutions for Equation (35), and . When , we obtain , and , which gives the infection-free equilibrium where

When and then from Equation (32), we obtain

We define a function H as:

Then

where

Thus, when . The parameter represents the basic HIV-1 single-infection reproductive number.

Further,

Hence, H is a strictly decreasing function of v, and thus, there exists a unique such that . It follows that

Here, satisfies the following quadratic equation:

with

Obviously, when . Equation (37) has a positive root as:

Hence, the chronic HIV-1 single-infection equilibrium exists when .

Now consider and . Solving Equations (26)–(30), we obtain two equilibria: The chronic HTLV-I single-infection equilibrium , where

where

Parameter is the basic HTLV-I single-infection reproductive number. Consequently, exists when . The other equilibrium is the chronic HIV-1/HTLV-I coinfection equilibrium where

and

We can see that exists when and . □

5. Global Stability

In this section, we demonstrate the global asymptotic stability of all equilibria by establishing appropriate Lyapunov functions. Define a function as . We have

Theorem 1.

If and , then is globally asymptotically stable (GAS) in .

Proof.

Define a discrete Lyapunov function as

Clearly, for all . In addition, . Evaluating the difference as:

Using inequality (39), we obtain

Collecting terms yields

We have , then we obtain

Since and then is monotonically decreasing. Clearly and hence, there is a limit and thus which gives and We consider four cases:

(i) and and then from Equation (6),

Therefore, from Equation (11), we obtain

Consequently, if and , then . This gives that is GAS. □

Theorem 2.

If and then is GAS in .

Proof.

Define

Clearly for all . In addition . Computing the difference as:

Using inequality (39), we obtain

Inequality (46) can be written as:

Collecting terms, we obtain

Utilizing the following conditions for :

we obtain

Then

and

Inequality (47) takes the form

Using the following equalities:

We obtain

Since , then and . Therefore, we obtain

Since and if , then is monotonically decreasing. We have and then there is a limit and hence which implies , , , , , , and . Now, we address two cases:

(i) . From Equation (3), we obtain

From Equation (11), we obtain

(ii) and then . From Equation (50), we obtain Hence, is GAS. □

Theorem 3.

If and , then is GAS in .

Proof.

Consider a discrete Lyapunov function as:

Computing the difference as:

Using inequality (39), we obtain

We write inequality (51) as:

By collecting the terms, we obtain

Using the equilibria conditions of

We obtain

Since we have

and using the following equality:

Then Equation (52) becomes

Since, then , for all Hence, the sequence is monotonically decreasing. Since then and thus Thus, , and We have two cases:

(i) and from Equation (3)

Theorem 4.

If , and then is GAS in the interior of .

Proof.

Consider

Computing the difference as:

Using inequality (39), we obtain

We write inequality (58) as:

After collecting the terms, we obtain

Using the equilibrium conditions for

we obtain

Then

and we obtain

We note that Hence, the sequence is monotonically decreasing. Since then and thus, Thus, Hence, is GAS. □

6. Numerical Simulations

In this section, we execute numerical simulations for the discrete-time model (3)–(11). Moreover, we discussed the impact of latent reservoirs on the HIV-1 and HTLV-I co-dynamics. We use the values of the parameters given in Table 1. Some of these values are taken from previous works for HIV-1 and HTLV-I single-infections. The values of other parameters are assumed just to execute the numerical simulations. The reason for that is the unavailability of real data from HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection patients. However, when the real data are available, then the values of the parameters of the coinfection model can be estimated.

Table 1.

Model parameters.

6.1. Stability of the Equilibria

To support the global stability results given Theorems 1–4, we show that the solutions of the discrete-time system starting from any point (any disease stage) in the feasible region will tend to one of the four equilibria. Let us consider three different initial values as:

We choose , and as:

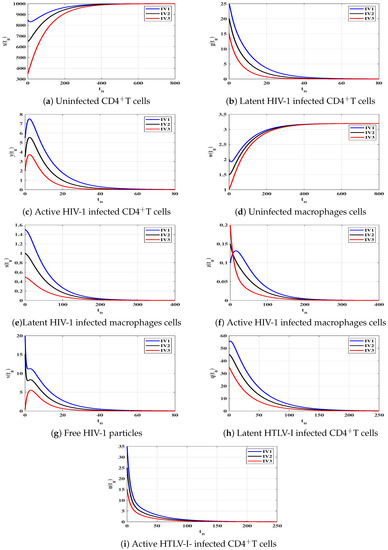

Case (I) and . This gives and . Figure 1 illustrates that the concentrations of uninfected CD4T cells and uninfected macrophages increase and tend to the healthy values and , while the concentrations of other populations decrease and converge to zero. Therefore, is GAS, and this agrees with the result of Theorem 1. In this case, both HIV-1 and HTLV-I are cleared from the human body, regardless of the starting states.

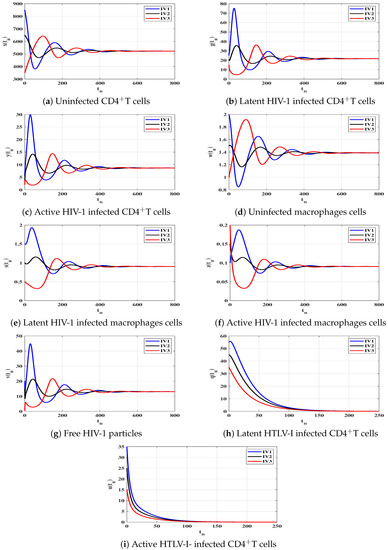

Case (II) and . These values give and . From Figure 2, we see that the solutions of the discrete-time model tend to the equilibrium . As a result, exists, and based on Theorem 2, it is GAS. This result shows that the HIV-1 single-infection can be reached for all initial states.

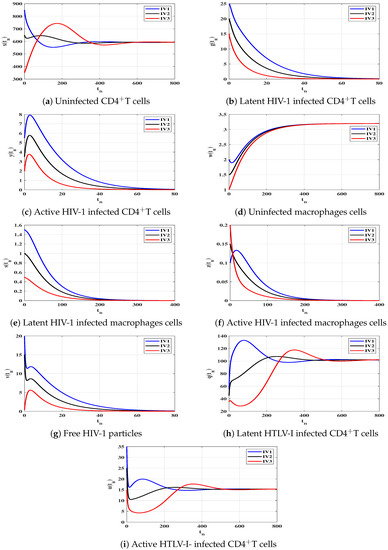

Case (III) and , and then and . Figure 3 demonstrates that the solutions of the discrete-time model reach the equilibrium for all the initial states. According to Lemma 2 and Theorem 3, exists and it is GAS. This result shows that the HTLV-I single-infection can be reached for all starting states.

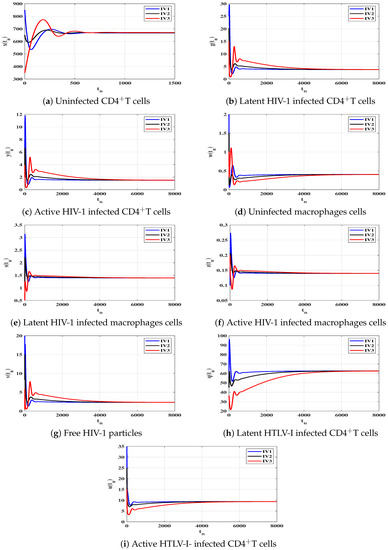

Case (IV) and , and thus, and . Figure 4 illustrates that the solutions of the discrete-time model starting with initial values IV1-IV3 converge to the equilibrium . Based on Lemma 2 and Theorem 4, exists and it is GAS. This result shows that the HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection can be reached for all starting states.

For more confirmation, we examine the local stability of the equilibria of the discrete-time model in Cases (I)–(IV). The Jacobian matrix of model (9)–(25) is calculated as:

where

Then, we compute the eigenvalues of the matrix at each equilibrium. An equilibrium point of the discrete-time model is locally asymptotically stable (LAS) when , for all . We compute the eigenvalues of all nonnegative equilibria using the values of , and given in Cases (I)–(IV). Table 2 contains the nonnegative equilibria, the absolute value of the eigenvalues and whether the equilibrium point is LAS or unstable. We note that when an equilibrium point is GAS, then it is also LAS, and all the other equilibria will be unstable.

Table 2.

Local stability of equilibria.

6.2. Impact of Latent Reservoirs on the HIV-1 and HTLV-I Co-Dynamics

In this part, we investigate the impact of the presence of latent reservoirs on HIV-1 and HTLV-I co-dynamics. Currently, there is no available treatment for HTLV-I [61]. Therefore, we only consider one type of HIV-1 antiviral drug, reverse transcriptase inhibitor (RTI), which prevents the HIV-1 from infecting the macrophages and CD4T cells. Let be the efficacy of the RTI drug. Now, we write model (1) under the effect of RTI:

The basic reproductive numbers of model (59) are given by

Similarly, the model with latent (2) under the influence of RTI drug is given as:

The basic reproductive numbers of model (60) are given by

We suppose that and . In order to stabilize the infection-free equilibrium for both systems (59) and (60), we determine the minimum drug efficacies and that make

where

We note that and . This means that neglecting the latent reservoirs in the HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection model will lead to an overestimation of the required HIV-1 antiviral drugs.

Lengthening of the Latent Phase

In this part, we study the effect of lengthening the latent phase on the HIV-1 and HTLV-I co-dynamics. The average length of the latent phases are given by , . Therefore, reducing the parameter will increase the transition time from latent to active and then will slow the viral replication. Let us assume that there exist two control actions and with the objective of reducing the transition rate (lengthening of the latent durations). These control actions may represent the efficacies of two drugs [62,63]. Let us multiply by , by and by where . Then, model (2) under the effect of such control actions can be written as:

Let the model’s parameters be fixed other than and , then the basic reproductive numbers of system (61) and as functions of and , respectively, are given by

and we have

Hence, and are strictly decreasing functions of and , respectively. Therefore, increasing the values of and will decrease the parameters and . Now we determine the minimum control actions and that make

and stabilize the system around the infection-free equilibrium . Using the values of the parameters given in Case (IV), we obtain and . Hence, both HIV-1 and HTLV-I will die out if the control actions satisfy and . It means that increasing the values of and will lengthen the latent phase and then clear the viruses from the body. This give some impression to develop new drug therapies for lengthening the latent phase.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we developed and addressed a mathematical model that describes in-host co-dynamics of HIV-1 and HTLV-I with latent reservoirs. The nonlinear continuous-time model is discretized by using the NSFD method. We first proved the positivity and boundedness of the discrete-time model, and then we calculated the model’s equilibria. We found that the model has four equilibria—infection-free equilibrium , chronic HIV-1 single-infection equilibrium , chronic HTLV-I single-infection equilibrium and chronic HIV-1/HTLV-I coinfection equilibrium . We deduced the conditions that determine the existence and stability of equilibria. These conditions were given in terms of four threshold parameters , . The global stability of all equilibria of the discrete-time model was examined by constructing Lyapunov functions. We proved that

- always exists, further, if and , then is GAS. This result recommends that when and , both HIV-1 and HTLV-I infections will be cleared regardless of the starting points.

- exists when , and it is GAS when and . This result recommends obtain when and , the HIV-1 single-infection is always established regardless of the starting points.

- exists when , and it is GAS when and . This result recommends that when and , the HTLV-I single-infection is always established regardless of the starting points.

- exists, and it is GAS when , and . This result recommends that the HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection is always established regardless of the starting points.

We simulated the discrete-time model to confirm the theoretical results. We discussed the impact of latent reservoirs on the HIV-1 and HTLV-I co-dynamics. We established that including the latent reservoirs in the HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection model will reduce both and . Therefore, neglecting the latent reservoirs can lead to an overestimation of the required HIV-1 antiviral drugs. Further, we found that lengthening the latent phase can suppress the viral progression. This may draw the attention of scientists and pharmaceutical companies to create new treatments that lengthen the latency period.

The HIV-1 and HTLV-I coinfection model presented in this work is given by a system of ordinary differential equations. The HIV-1 and HTLV-I co-dynamics can be described by (i) delay differential equations by incorporating the time delay [21], (ii) partial differential equations by considering the mobility of cells and viruses [64], (iii) stochastic differential equations by taking into account the random fluctuations [65,66,67,68] and (iv) fractional differential equations by considering the memory effects [69]. Great efforts are needed to study such points; therefore, we leave them for future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.E. and A.K.A.; Formal analysis, A.M.E., A.K.A. and A.D.H.; Investigation, A.M.E. and A.K.A.; Methodology, A.M.E. and A.D.H.; Writing—original draft, A.K.A.; Writing—review & editing, A.M.E. and A.K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This Project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. (G/617/130/37).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This Project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. (G/617/130/37). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| ATL | Adult T-cell leukemia |

| CTLs | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes |

| GAS | Globally asymptotically stable |

| HAM/TSP | HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HIV-1 | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 |

| HTLV-I | Human T-lymphotropic virus type I |

| LAS | Locally asymptotically stable |

| NSFD | Non-standard finite difference |

| IAV | Influenza A virus |

| RTI | Reverse transcriptase inhibitor |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| sup | Supremum (least upper bound) |

References

- Nowak, M.A.; Bangham, C.R.M. Population dynamics of immune responses to persistent viruses. Science 1996, 272, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilianakis, N.I.; Seydel, J. Modeling the T-cell dynamics and pathogenesis of HTLV-I infection. Bull. Math. Biol. 1999, 61, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciupe, S.M.; Ribeiro, R.M.; Nelson, P.W.; Perelson, A.S. Modeling the mechanisms of acute hepatitis B virus infection. J. Theor. Biol. 2007, 247, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, K.; Kuniya, T.; Nakaoka, S.; Asai, Y.; Watashi, K.; Iwami, S. Mathematical analysis of a transformed ODE from a PDE multiscale model of hepatitis C virus infection. Bull. Math. Biol. 2019, 81, 1427–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccam, P.; Beauchemin, C.; Macken, C.A.; Hayden, F.G.; Perelson, A.S. Kinetics of influenza A virus infection in humans. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7590–7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Vargas, E.A.; Velasco-Hernandez, J.X. In-host mathematical modelling of COVID-19 in humans. Annu. Rev. Control 2020, 50, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Miao, H.; Brown, A.N.; Rong, L. Modeling the viral dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Math. Biosci. 2020, 328, 108438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comez, M.C.; Yang, H.M. Mathematical model of the immune response to dengue virus. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 63, 455–478. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Stability and Hopf bifurcation of a within-host chikungunya virus infection model with two delays. Math. Comput. Simul. 2017, 138, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, K.; Perelson, A.S. Mathematical modeling of within-host Zika virus dynamics. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 285, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Xiao, Y.; Sander, B.; Kulkarni, M.A.; RADAM-LAC Research Team; Wu, J. Modelling the impact of antibody-dependent enhancement on disease severity of Zika virus and dengue virus sequential and co-infection. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 191749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlShamrani, N.H. Analysis of a within-host HTLV-I/HIV-1 co-infection model with immunity. Virus Res. 2021, 295, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlShamrani, N.H. HTLV/HIV dual infection: Modeling and analysis. Mathematics 2021, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinky, L.; Dobrovolny, H.M. SARS-CoV-2 coinfections: Could influenza and the common cold be beneficial? J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2623–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elaiw, A.M.; Alsulami, R.S.; Hobiny, A.D. Modeling and stability analysis of within-host IAV/SARS-CoV-2 coinfection with antibody immunity. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, A.D.A.; Elaiw, A.M.; Ramadan, S.A.A.E. Stability analysis of within-host SARS-CoV-2/HIV coinfection model. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2022, 45, 11403–11422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; Shflot, A.S.; Hobiny, A.D. Global stability of delayed SARS-CoV-2 and HTLV-I coinfection models within a host. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birger, R.; Kouyos, R.; Dushoff, J.; Grenfell, B. Modeling the effect of HIV coinfection on clearance and sustained virologic response during treatment for hepatitis C virus. Epidemics 2015, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nampala, H.; Livingstone, S.; Luboobi, L.; Mugisha, J.Y.T.; Obua, C.; Jablonska-Sabuka, M. Modelling hepatotoxicity and antiretroviral therapeutic effect in HIV/HBV coinfection. Math. Biosci. 2018, 302, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.W.; Murray, J.D.; Perelson, A.S. A model of HIV-1 pathogenesis that includes an intracellular delay. Math. Biosci. 2000, 163, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.W.; Perelson, A.S. Mathematical analysis of delay differential equation models of HIV-1 infection. Math. Biosci. 2002, 179, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelson, A.S.; Nelson, P.W. Mathematical analysis of HIV-1 dynamics in vivo. SIAM Rev. 1999, 41, 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Huang, L.; Yuan, Z. Global stability for an HIV-1 infection model with Beddington-DeAngelis incidence rate and CTL immune response. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2014, 19, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Xu, R.; Tian, X. Threshold dynamics of an HIV-1 model with both viral and cellular infections, cell-mediated and humoral immune responses. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2018, 16, 292–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, J. Threshold dynamics of a delayed nonlocal reaction-diffusion HIV infection model with both cell-free and cell-to-cell transmissions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2020, 488, 124047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Qiu, Z.; Meng, X.; Rong, L. Analysis of a stochastic HIV-1 infection model with degenerate diffusion. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 348, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, D.S.; Perelson, A.S. HIV-1 infection and low steady state viral loads. Bull. Math. Biol. 2002, 64, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.M.; Banks, H.T.; Kwon, H.-D.; Tran, H.T. Dynamic multidrug therapies for HIV: Optimal and STI control approaches. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2004, 1, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, B.M.; Banks, H.T.; Davidian, M.; Kwon, H.-D.; Tran, H.T.; Wynne, S.N.; Rosenberg, E.S. HIV dynamics: Modeling, data analysis, and optimal treatment protocols. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2005, 184, 10–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, L.; Perelson, A.S. Modeling HIV persistence, the latent reservoir, and viral blips. J. Theor. Biol. 2009, 260, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perelson, A.S.; Essunger, P.; Cao, Y.; Vesanen, M.; Hurley, A.; Saksela, K.; Markowitz, M.; Ho, D.D. Decay characteristics of HIV-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature 1997, 387, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobeinikov, A. Global properties of basic virus dynamics models. Bull. Math. Biol. 2004, 66, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, A.G.; Maini, P.K. HTLV-I infection: A dynamic struggle between viral persistence and host immunity. J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 352, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, W. Global dynamics of a reaction and diffusion model for an HTLV-I infection with mitotic division of actively infected cells. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 2017, 7, 899–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ma, W. Dynamics analysis of an HTLV-1 infection model with mitotic division of actively infected cells and delayed CTL immune response. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2018, 41, 3000–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajanchi, S.; Bera, S.; Roy, T.K. Mathematical analysis of the global dynamics of a HTLV-I infection model, considering the role of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Math. Comput. Simul. 2021, 180, 354–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Heffernan, J.M. Viral dynamics of an HTLV-I infection model with intracellular delay and CTL immune response delay. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2018, 459, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlShamrani, N.H.; Dahy, E.; Abdellatif, A. Stability of within host HTLV-I/HIV-1 co-infection in the presence of macrophages. Int. J. Biomath. 2022, 16, 2250066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; Aljahdali, A.K.; Hobiny, A.D. Dynamical [roperties of discrete-time HTLV-I and HIV-1 within-host coinfection model. Axioms 2023, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; AlShamrani, N.H.; Dahy, E.; Abdellatif, A.A.; Raezah, A.A. Effect of macrophages and latent reservoirs on the dynamics of HTLV-I and HIV-1 coinfection. Mathematics 2023, 11, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickens, R.E. Nonstandard Finite Difference Models of Differential Equations; World Scientific: Singapore, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Korpusik, A. A nonstandard finite difference scheme for a basic model of cellular immune response to viral infection. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2017, 43, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Xu, J.; Hou, J. Discretization and dynamic consistency of a delayed and diffusive viral infection model. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 316, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Geng, Y. Stabilty preserving NSFD scheme for a delayed viral infection model with cell-to-cell transmission and general nonlinear incidence. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2017, 23, 893–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, K. A non-standard finite difference scheme for a diffusive HBV infection model with capsids and time delay. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2017, 23, 1901–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, S.; Torres, D.F.M. Discrete-time system of an intracellular delayed HIV model with CTL immune response. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.02199. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, S.M. A nonstandard finite difference scheme and optimal control for an HIV model with Beddington-DeAngelis incidence and cure rate. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2020, 135, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Zhu, C.C. A non-standard finite difference scheme for a diffusive HIV-1 infection model with immune response and intracellular delay. Axioms 2022, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; Alshaikh, M.A. Stability of discrete-time HIV dynamics models with three categories of infected CD4+ T-cells. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2019, 2019, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, S.A.; Nawaz, Y.; Arif, M.S. On the nonstandard finite difference method for reaction–diffusion models. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 166, 112929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamar, M.H.; Ehrhardt, M.; Tabharit, L. A Nonstandard Finite Difference Scheme for a Time-Fractional Model of Zika Virus Transmission. 2022. Available online: https://www.imacm.uni-wuppertal.de/fileadmin/imacm/preprints/2022/imacm_22_21.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Farooqi, A.; Ahmad, R.; Alotaibi, H.; Nofal, T.A.; Farooqi, R.; Khan, I. A comparative epidemiological stability analysis of predictor corrector type non-standard finite difference scheme for the transmissibility of measles. Results Phys. 2021, 21, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Dong, L. Dynamical behaviors of a discrete HIV-1 virus model with bilinear infective rate. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2014, 37, 2271–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelson, A.S.; Kirschner, D.E.; de Boer, R. Dynamics of HIV Infection of CD4+ T cells. Math. Biosci. 1993, 114, 81–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elaiw, A.M.; Raezah, A.A.; Azoz, S.A. Stability of delayed HIV dynamics models with two latent reservoirs and immune impairment. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 50, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohri, H.; Bonhoeffer, S.; Monard, S.; Perelson, A.S.; Ho, D. Rapid turnover of T lymphocytes in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. Science 1998, 279, 1223–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wodarz, D.; Nowak, M. Immune responses and viral phenotype: Do replication rate and cytopathogenicity influence virus load? J. Theor. Med. 1999, 2, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaiw, A.M.; Alshaikh, M.A. Stability preserving NSFD scheme for a general virus dynamics model with antibody and cell-mediated responses. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 138, 109862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, L. Viral dynamics of an HIV model with latent infection incorporating antiretroviral therapy. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2016, 2016, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Lim, A.G. Modelling the role of Tax expression in HTLV-1 persisence in vivo. Bull. Math. Biol. 2011, 73, 3008–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, M.T.; Mizan, S.; Yasmin, F.; Akash, A.S.; Shahik, S. Epitope-based universal vaccine for Human T-lymphotropic virus-1 (HTLV-1). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, A.A.C.; McSharry, J.J.; Drusano, G.L.; Nguyen, J.T.; Went, G.T.; Ribeiro, R.M.; Perelson, A.S. Modeling amantadine treatment of influenza A virus in vitro. J. Theor. Biol. 2008, 254, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrovolny, H.M. Quantifying the effect of remdesivir in rhesus macaques infected with SARSCoV-2. Virology 2020, 550, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellomo, N.; Outada, N.; Soler, J.; Tao, Y.; Winkler, M. Chemotaxis and cross diffusion models in complex environments: Modeling towards a multiscale vision. Math. Model. Methods Appl. Sci. 2022, 32, 713–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Khan, S.U. Dynamics and simulations of stochastic COVID-19 epidemic model using Legendre spectral collocation method. AIMS Math. 2023, 8, 4220–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, K.; Jiang, D.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A. Virus dynamic behavior of a stochastic HIV/AIDS infection model including two kinds of target cell infections and CTL immune. Math. Comput. Simulat. 2021, 188, 548–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Khan, S.U. Asymptotic behavior of three connected stochastic delay neoclassical growth systems using spectral technique. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Khan, S.U. Threshold of stochastic SIRS epidemic model from infectious to susceptible class with saturated incidence rate using spectral method. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.N.; Basir, F.A.; Almuqrin, M.A.; Mondal, J.; Khan, I. SARS-CoV-2 infection with lytic and nonlytic immune responses: A fractional order optimal control theoretical study. Results Phys. 2021, 26, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).