Abstract

Large Language Models (LLMs) now occupy a prominent role in science, engineering, and higher education. Their capacity to generate step-wise solutions, conceptual explanations, and problem-solving pathways creates new opportunities—but also new risks—for Chemical Engineering learners. Despite widespread informal use, few empirical studies have evaluated LLM performance using a systematically designed dataset mapped directly to Bloom’s Taxonomy. This study evaluates the competency of ChatGPT in solving Chemical Engineering problems mapped to Bloom’s Taxonomy. A diverse dataset of undergraduate-level problems spanning six cognitive domains was used to assess the model’s reasoning across ascending levels of cognitive complexity. Each response was evaluated for accuracy and categorized into five error types. Although ChatGPT demonstrated considerable potential across a range of topics, the analysis also revealed important challenges and limitations that inform best practices for integrating LLMs into Chemical Engineering education. Results show significant differences in ChatGPT performance across Bloom levels, revealing three distinct tiers of capability. Strong performance was observed at lower cognitive levels (Remember–Apply), while substantial degradation occurred at Analyze, Evaluate, and specially Create. The findings provide a nuanced, empirically grounded understanding of current LLM capability limits, with practical recommendations for educators integrating LLMs into engineering curricula.

1. Introduction

The introduction of large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT has represented a pivotal transformation in the educational landscape, especially since OpenAI’s public release of ChatGPT in November 2022. Within weeks, it became one of the fastest-growing digital platforms, accumulating over 100 million users by early 2023 [1]. The widespread accessibility of ChatGPT has prompted educators, researchers, and policy makers to reconsider traditional learning paradigms, particularly in higher education contexts where critical reasoning, creativity, and analytical skills are core outcomes [2].

ChatGPT, powered by the Generative Pre-Trained Transformer (GPT) architecture, processes and generates text through probabilistic modeling of linguistic patterns [3]. Its capacity to synthesize explanations, produce worked examples, and simulate dialogic tutoring has led to its increasing use as a “cognitive amplifier”—a tool that enhances access to information and scaffolds conceptual understanding [4]. However, this capability also raises pedagogical and ethical concerns: while ChatGPT can provide immediate, articulate responses, its reasoning is often shallow and disconnected from genuine conceptual understanding [5].

Several researchers have observed that ChatGPT’s outputs, while linguistically fluent, may lack factual reliability, leading to the generation of confident yet incorrect responses [6]. This issue, known as AI hallucination, challenges educators’ ability to integrate LLMs responsibly into learning environments. Moreover, the proliferation of AI-generated content has intensified debates around academic integrity and authenticity in assessment [7]. As a result, higher education institutions now face dual imperatives: to leverage AI for learning enhancement and to mitigate risks associated with its misuse.

Engineering education, and particularly Chemical Engineering, presents a unique context for evaluating AI competency due to its heavy reliance on problem solving, mathematical reasoning, and conceptual abstraction. The typical engineering curriculum progresses from fundamental scientific principles toward complex process design, mirroring Bloom’s hierarchical model of cognitive development, in which students advance from basic recall and comprehension to higher-order skills such as analysis, evaluation, and creation. This alignment ensures that early-stage courses focus on building foundational knowledge and problem-solving techniques, while later-stage courses challenge students to integrate concepts, critically assess alternatives, and design innovative solutions to real-world engineering problems.

1.1. Bloom’s Taxonomy and Cognitive Assessment Frameworks

Bloom’s Taxonomy was first introduced in 1956 by Benjamin Bloom which presents the hierarchy of cognitive learning in the form of six-levels—Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation. Later in 2001, Anderson & Krathwohl [8] revised Bloom Taxonomy simplifying the nouns of Bloom Taxonomy into actionable verbs—Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, and Create—each associated with increasing cognitive demand (Figure 1). The framework underpins curriculum design, assessment, and pedagogy across disciplines, including engineering.

Figure 1.

Revised framework for Bloom’s Taxonomy.

The taxonomy aligns particularly well with engineering education because it mirrors the progressive complexity of problem-solving tasks. Early-stage engineering problems (e.g., unit conversions or property calculations) primarily assess the Remember and Apply levels, whereas advanced design and optimization tasks engage the Analyze, Evaluate, and Create levels. Studies by Prince and Felder [9] and Vesilind [10] emphasize that expert engineers exhibit higher-order cognition involving reflective judgment, critical evaluation of assumptions, and creative synthesis of multiple domains—precisely the cognitive dimensions most difficult for AI models to replicate.

Recent educational research has applied Bloom’s framework to assess AI learning and reasoning. Qadir [5] developed a “Bloom–AI Alignment Matrix” to evaluate ChatGPT’s responses across cognitive levels in computer science education, finding that ChatGPT excels at recall and comprehension. Similarly, Kasneci et al. [1] concluded that while LLMs can mimic the Apply and Understand levels through pattern recognition, they lack genuine cognitive reflection, as their reasoning is non-intentional and purely data-driven. In engineering contexts, applying Bloom’s Taxonomy provides a theoretically grounded method for evaluating whether AI-generated reasoning aligns with human cognitive progression. It allows educators to map the depth and authenticity of AI responses relative to expert expectations, forming the core evaluative framework of the current study.

1.2. ChatGPT and Cognitive Alignment Studies

A number of studies have directly evaluated ChatGPT’s problem-solving performance in non-engineering domains using Bloom’s Taxonomy or similar cognitive benchmarks. It was reported that ChatGPT produced coherent explanations for lower-level cognitive tasks but showed structural weaknesses in causal reasoning and synthesis [1]. Qadir [5] corroborated this in programming contexts, noting that ChatGPT often generated syntactically correct but logically flawed code—a parallel to its performance in mathematical reasoning.

In the sciences, Banstola observed that ChatGPT could reproduce standard derivations, such as chemical kinetics rate laws, but struggled with context-specific constraints, including assumptions about ideal mixing or temperature dependence [11]. Oss reported that ChatGPT could derive energy balances for standard thermodynamic systems but failed to justify modelling assumptions or select appropriate correlations, highlighting its limited evaluative cognition [12].

Comparative studies indicate that ChatGPT performs better on formulaic reasoning tasks but deteriorates when abstraction and design creativity are required [2]. This pattern is consistent across disciplines: ChatGPT’s performance is dropped with increasing degree of open-ended reasoning demanded [1,4].

Kasneci et al. [1] introduced the concept of synthetic cognition—the apparent reasoning displayed by LLMs that mirrors, but does not replicate, human thought processes. ChatGPT’s success at lower Bloom levels therefore represents cognitive mimicry, not authentic understanding. For engineering educators, distinguishing between these modes of reasoning is essential to ensure that students develop genuine cognitive autonomy.

1.3. AI Literacy and Pedagogical Implications

The integration of generative AI into higher education has catalyzed a growing movement toward AI literacy, defined as the capacity of students and educators to understand, evaluate, and appropriately use AI-generated outputs [13,14]. Contemporary AI literacy frameworks emphasize three core competencies: (1) understanding AI’s capabilities and limitations; (2) critically interpreting AI-generated information; and (3) applying ethical and responsible use principles [14]. In Chemical Engineering education, these competencies extend beyond surface-level verification of AI-produced calculations to include an epistemological understanding of engineering knowledge—why assumptions matter, how data validity shapes model reliability, and where human judgment remains irreplaceable [15]. Consequently, the use of generative AI raises not only technical but also pedagogical and ethical concerns, particularly regarding the risk of cognitive outsourcing and the erosion of higher-order reasoning if AI is deployed as an autonomous problem solver rather than a learning scaffold [1].

Recent systematic reviews and empirical studies in STEM and chemical education consistently emphasize that generative AI is most effective when embedded within instructor-guided, pedagogically structured learning environments, rather than used as a stand-alone automation tool [16]. Brazao et al. argue that AI tools should function as scaffolding instruments, supporting cognitive development while preserving critical reflection and conceptual reasoning [17].

Similarly, Dave highlights that meaningful AI integration in engineering education requires assessment redesign that priorities reasoning transparency over final numerical answers [18]. Rather than asking students merely to compute a result, educators can require them to critique AI-generated solutions, identify flawed assumptions, and propose justified revisions—thereby reinforcing the central role of the educator as a facilitator of epistemic judgment [19,20].

This instructor-mediated approach aligns with broader pedagogical research on emerging technologies in chemical and STEM education, which demonstrates that AI-enhanced learning promotes self-regulated learning, inquiry, and conceptual understanding only when guided by clear learning objectives, ethical frameworks, and cognitive taxonomies such as Bloom’s Taxonomy [8,21]. Bloom’s framework provides a pedagogical bridge between traditional educational theory and AI-assisted learning by enabling educators to systematically interpret AI performance across cognitive levels—from recall to evaluation and creation—and design activities that preserve human oversight at higher-order levels. In this way, generative AI is reframed not as a threat to learning integrity, but as a partner in guided cognition, with educators retaining responsibility for curriculum alignment, ethical use, and the cultivation of disciplinary judgment [1,19].

1.4. Research Gap and Rationale for the Current Study

Despite growing research on ChatGPT’s educational applications, there remains a lack of domain-specific evaluations grounded in cognitive taxonomies. Existing studies focus heavily on humanities and computer science, with empirical analyses in engineering, particularly Chemical Engineering, being scarce. Furthermore, few studies employ expert comparative evaluation, which is essential for assessing AI reasoning quality in highly technical domains.

This study addresses this gap by combining Bloom’s Taxonomy with expert-based evaluation of ChatGPT’s responses to authentic Chemical Engineering problems. This study systematically quantifies ChatGPT’s cognitive performance across the full taxonomy spectrum—from basic recall to creative synthesis.

By bridging pedagogical theory with empirical AI evaluation, this study contributes to both AI education research and engineering pedagogy, offering insights into how generative AI can be responsibly integrated into the cognitive architecture of higher education.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a systematic, empirical evaluation of ChatGPT’s performance in solving Chemical Engineering problems, mapped onto Bloom’s Taxonomy. The study design combined (1) authentic problem generation, (2) ChatGPT response collection, and (3) expert-based cognitive assessment. A total of 110 undergraduate-level problems were selected to represent the full range of cognitive demands, from lower-order skills (Remember, Understand) to higher-order skills (Analyse, Evaluate, Create). Problems were drawn from standard undergraduate Chemical Engineering curricula, including thermodynamics, fluid dynamics, heat and mass transfer, and chemical reaction engineering, optimisation, safety, environmental science, process synthesis and design etc. The problem set was curated by the authors, both of whom have formal training and teaching experience in Chemical Engineering, and was informed by past examination papers, coursework assignments, and problem sheets from accredited undergraduate programmes. The selection process aimed to reflect authentic assessment practices rather than artificially constructed or ad hoc prompts. Table 1 shows some sample problems mapped against Bloom Taxonomy. Full list of problems is provided in Supplementary Information. Each problem was framed in an exam-style format to reflect realistic student assessment conditions.

Table 1.

Sample problems mapping into Bloom’s Taxonomy.

The problems in this study comprised a mixture of conceptual questions, practice problems with simple calculations, and more complex tasks requiring explanation, reasoning, and process analysis. Higher-order problems involved evaluation and creation of processes, including real-world design challenges that required making assumptions, gathering information, and making engineering decisions while considering techno-economic and ethical factors [22]. Each problem was clearly mapped to a revised Bloom’s Taxonomy level using established engineering education frameworks [22], as illustrated in Figure 1. Question difficulty and Bloom levels were assigned to reflect realistic curricula: lower-year modules contained a higher proportion of Knowledge and Comprehension items, whereas later-year modules emphasized Analysis, Evaluation, and Creation tasks. This design enabled a comprehensive evaluation of ChatGPT’s effectiveness across a broad spectrum of concepts and cognitive demands, facilitating comparison with performance in other disciplines.

2.2. Procedure and Analysis

We used ChatGPT 3.5 because students and instructors in Chemical Engineering courses are more likely to interact with ChatGPT through its standard interface than to access GPT-3.5 directly via APIs. This approach ensures that our findings are relevant and applicable to real-world engineering education contexts, where large language model tools like ChatGPT are commonly used for teaching and learning.

Each problem statement was copied directly as a prompt, consistently prefaced with the instruction, “solve the following chemical engineering problem”, and the responses were recorded in a centralised document for analysis. We employed a grading approach similar to that used by higher education institutions when marking students worked-out solutions, allowing two knowledgeable evaluators to effectively assess both the reasoning and accuracy of each response. All 110 responses were independently evaluated by the same pair of evaluators with prior experience in marking undergraduate assessments. This ensured consistency in interpretation and scoring across all Bloom levels. Each question was entered as a standard text prompt without providing step-by-step hints or follow-up clarifications. Standard prompts were deliberately employed to reflect typical student usage patterns. The study aims to evaluate default AI behaviour under conditions that mirror typical student use, not expert prompt engineering. This choice is essential for pedagogical validity, as educational risk arises precisely when students do not request deeper justification or self-critique.

Our goal was not only to verify the correctness of ChatGPT’s final answers but also to examine the reasoning process it followed. When incorrect answers were produced, each step was compared against the instructor’s reference solution to identify where the reasoning diverged, which emphasised the following:

- A concise and clear depiction of the problem, emphasising key elements through a diagram or brief bullet points

- Recognition of the underlying physical principles and applicable governing equations

- Compilation of all essential data required for the solution, including approaches for determining any missing information through estimation or external sources

- Logical and methodical execution of calculations to obtain the final, correct outcome

Each response was scored on:

- Accuracy (0–100%)—factual and numerical correctness

- Reasoning Quality (1–5)—logical coherence and completeness (Table S2)

- Error Type—categorized as conceptual, factual, computational, contextual and residual.

The ‘Reasoning Quality’ score (1–5) defines the clarity, coherence, and completeness of reasoning explicitly articulated in the model’s response, rather than any presumed latent cognitive processing. This operationalization was intentionally adopted to reflect authentic student–AI interactions, which typically rely on single, minimally scaffolded prompts and do not involve expert-level prompt engineering. By constraining prompts in this manner, the evaluation avoids conflating model performance with variations in student creativity or metacognitive prompting skill and ensures that assessed reasoning remains pedagogically accessible to learners.

Inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s κ = 0.87) confirmed high agreement between raters. Statistical analysis (ANOVA) was applied to determine significant performance differences across Bloom levels.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Performance Trends

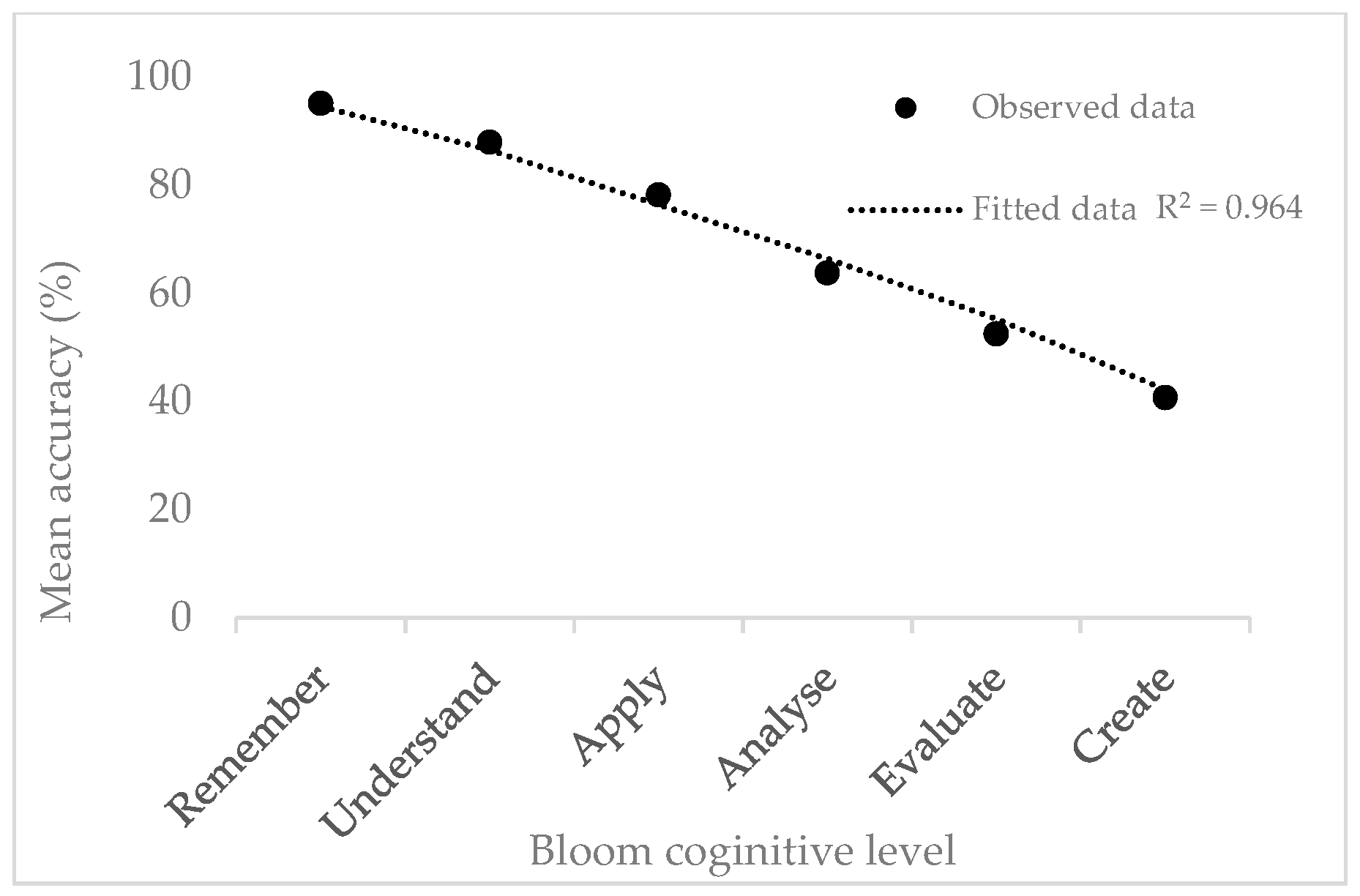

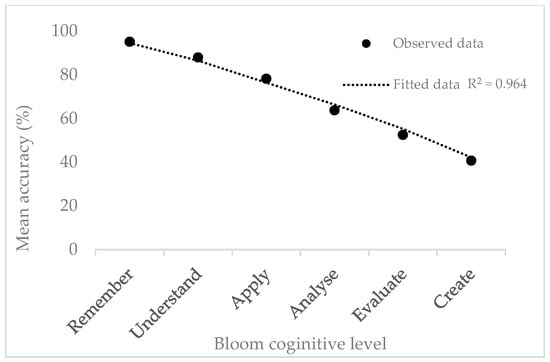

The aggregated data from 110 evaluated responses revealed a clear negative relationship between Bloom’s cognitive level and ChatGPT’s performance accuracy. Figure 2 (accuracy vs. Bloom level) illustrates a smooth downward curve, with a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.96, signifying that nearly 96% of the variance in mean accuracy can be explained by the increasing cognitive complexity of the task.

Figure 2.

Trend of mean accuracy across Bloom’s levels.

Table 2 summarizes ChatGPT’s performance across Bloom’s cognitive levels using a dataset of 110 randomized responses, available in Supplementary Information. At the Remember and Understand levels (95.1% ± 3.2% and 87.9% ± 5.4%, respectively), ChatGPT performs exceptionally well, showing near-perfect factual recall, accurate reproduction of definitions, and clear articulation of standard procedures. Responses are typically detailed, often exceeding the requirements of the question, and errors, when present, are minor and superficial, such as misnaming coefficients or making small unit conversion slips.

Table 2.

ChatGPT accuracy by Bloom’s level.

At the Apply level (78.2% ± 8.1%), the model’s strength transitions from recall to procedural execution. Here, ChatGPT demonstrates a basic understanding of methodologies and can often combine equations correctly when each component is straightforward. For example, in questions drawn from areas such as Separation Processes, Engineering Mathematics, and Chemical Reactor Design, ChatGPT successfully identifies relevant formulas and performs initial calculations. However, it struggles when multiple equations or contextual decisions must be combined, often failing to select the most appropriate correlation or boundary condition when several are plausible. Around one in five responses contain dimensional or algebraic inconsistencies typical of rote substitution without physical validation. This limitation becomes especially evident in multistep calculations or when the model is required to assess the quality of its own answers through analysis or commentary.

Performance drops significantly at the Analyze level (63.8% ± 9.7%), where questions require decomposition of systems, comparison of mechanisms, or multivariable reasoning. Tasks from modules such as Solids Processing, Chemical Thermodynamics, and Process Fluid Flow reveal that, while ChatGPT can perform some intermediate calculations and describe alternative hypotheses fluently, it rarely prioritizes or critiques them accurately. It occasionally applies incorrect formulas, leading to inaccurate final answers even when some parameters are computed correctly. Conceptual conflation, such as confusing rate-limiting steps with equilibrium constraints, emerges as a recurrent pattern, highlighting limitations in its ability to differentiate between closely related concepts.

At the Evaluate level (52.5% ± 11.9%), ChatGPT’s weaknesses become more pronounced. Questions drawn from areas like chemical reactor design, optimization, and fluid dynamics reveal that while it can produce structured and persuasive arguments, these are often superficial and technically shallow. When asked to critique designs or justify methodological choices, ChatGPT tends to present confident yet unsupported conclusions, lacking evidence weighting or hierarchical analysis. It can provide partial guidance or perform some calculations correctly but struggles to complete complex problems or to integrate quantitative reasoning with critical judgment.

Finally, at the Create level (40.7% ± 13.2%), ChatGPT’s responses become generic and inconsistent, displaying limited originality. In open-ended areas such as process integration, process synthesis, and process design and simulation, it can generate basic frameworks or initial ideas—such as functional MATLAB scripts or broad guidance for Heat Exchanger Network synthesis—but these typically lack optimization, accuracy, or innovation. For instance, ChatGPT can produce a working code structure but often fails to achieve the correct output or to comply with problem constraints (e.g., techno-economical or techno-ethical). Similarly, in process design tasks requiring software-specific knowledge (e.g., Aspen Plus), the model provides procedural advice but cannot optimize models or evaluate results effectively.

Overall, ChatGPT transitions effectively from factual recall to procedural application but exhibits progressive limitations as cognitive demands increase. While highly reliable for foundational learning, conceptual explanation, and preliminary guidance in coursework, its ability to execute multistep calculations, perform critical evaluation, or generate original design insights remains constrained. As such, ChatGPT serves best as a supportive learning tool for guidance and conceptual clarity, rather than as a standalone problem-solving or design platform at advanced cognitive levels.

3.2. Variability and Reliability

Standard deviations increased monotonically from low to high Bloom levels (3.2% to 13.2%), reflecting growing inconsistency as questions demanded abstraction and synthesis. Coefficient of variation (CV) rose from 3.4% at Remember to 32.4% at Create, indicating that even within the same cognitive category, performance stability declines markedly with complexity.

Bloom’s Taxonomy levels were treated as analytic groupings rather than experimentally manipulated variables. Accordingly, one-way ANOVA was employed as a descriptive inferential technique to examine whether systematic differences in ChatGPT’s performance existed across established cognitive categories, rather than to infer causal relationships. The analysis yielded a highly significant effect of cognitive level on model accuracy (F = 52.3, p < 0.001), indicating substantial variation across the six Bloom categories. Post hoc Tukey tests revealed three statistically distinct tiers of performance: Tier 1 (Remember and Understand), which did not differ significantly from each other (p > 0.1); Tier 2 (Apply), which performed significantly below Tier 1 (p < 0.01); and Tier 3 (Analyze, Evaluate, and Create), which were mutually similar but all significantly below Tier 2 (p < 0.001). This tiered pattern suggests that once tasks progress beyond procedural application into analytical and evaluative reasoning, ChatGPT’s linguistic generalization becomes insufficient to substitute for the structural, mathematical, or domain-specific reasoning required in chemical engineering problem solving. While the ‘Reasoning Quality’ score is ordinal in nature, inferential claims are primarily grounded in accuracy-based metrics, with reasoning quality serving as complementary evaluative evidence to support triangulation of findings. The strong monotonic performance decline across Bloom levels and the large observed effect sizes indicate that the principal conclusions are robust to reasonable analytic choices.

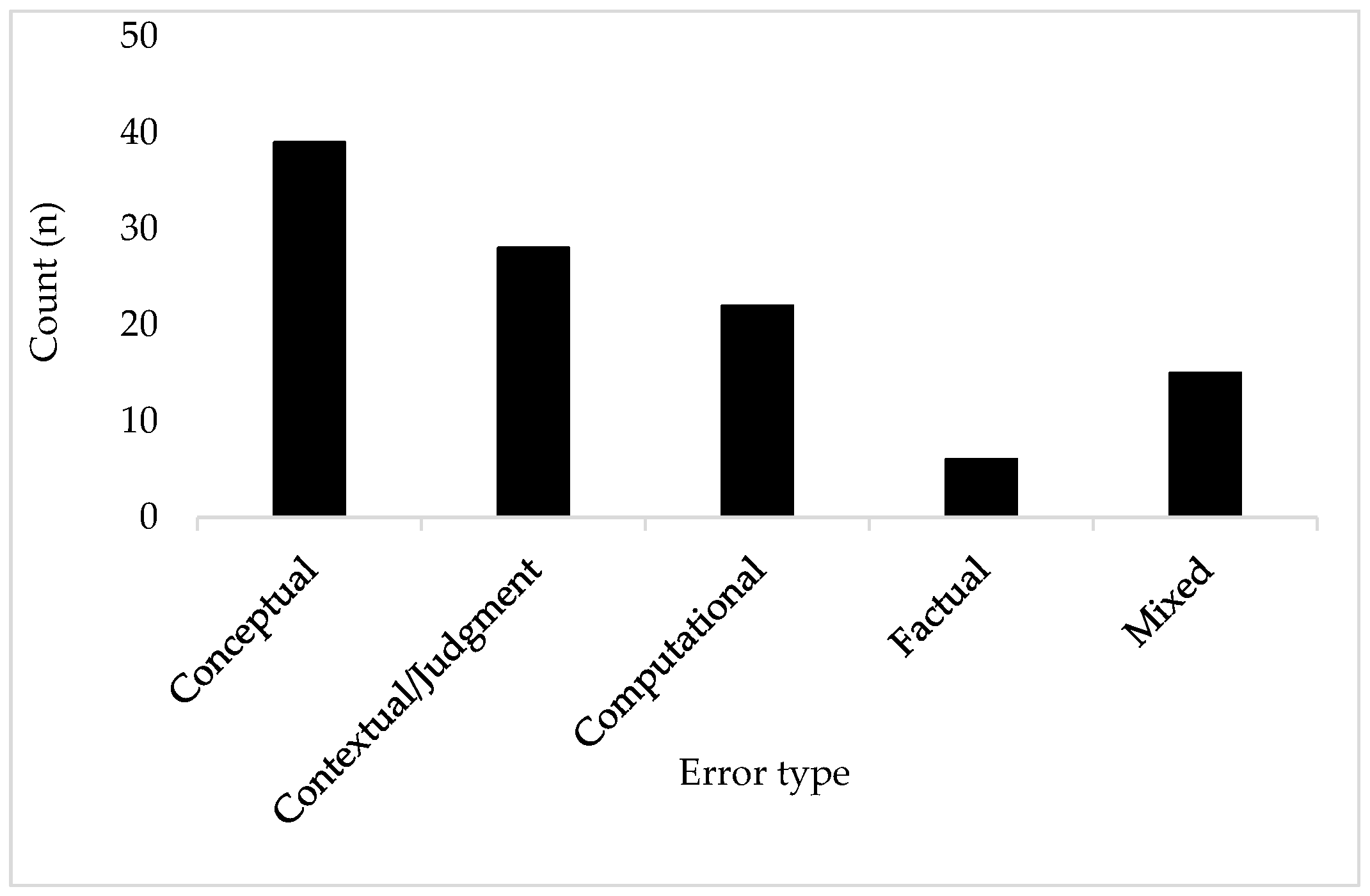

3.3. Error Analysis Across Bloom Levels

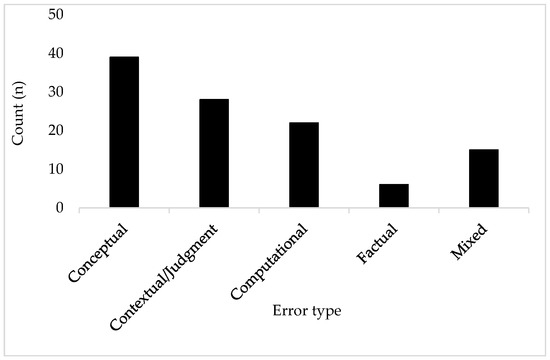

To characterise the nature of ChatGPT’s limitations across cognitive levels, all responses were coded into four primary error categories—factual, computational, conceptual, and contextual/judgment—with an additional “mixed/ambiguous” category used when multiple error types co-occurred. Figure 3 shows the distribution of error types across all responses.

Figure 3.

Distribution of error types across all responses.

Across all Bloom levels, conceptual errors constituted the largest category (35%), followed by contextual/judgment (25%), computational (20%), and factual (5%). The remaining 15% involved mixed or ambiguous cases where two or more error types appeared simultaneously. These proportions remained broadly consistent across modules, although contextual/judgment errors increased markedly in the Evaluate and Create levels.

3.3.1. Factual Errors

Factual errors were comparatively rare. These typically involved incorrect constants, misremembered typical property values, or confusion between unit systems. For example, in response to a heat-transfer question, ChatGPT claimed that “convection only occurs in gases,” omitting the fact that convection is a fluid-phase phenomenon and occurs in liquids as well. In property-estimation tasks, ChatGPT occasionally produced typical values that were outside accepted engineering ranges. These errors were infrequent because the model’s training corpus includes a large amount of textbook-style reference data, making factual recall one of its strongest competencies. Some examples of factual errors are included in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Sample examples of factual errors in ChatGPT responses.

3.3.2. Computational Errors

Computational errors were observed most frequently in multi-step numerical problems, especially unit conversions and algebraic manipulations. For example, when asked to convert 554 m4·day−1·kg−1 to cm4·min−1·g−1, ChatGPT employed the correct conversion factors and cancellation steps but produced a final result that was several orders of magnitude too small (0.02420 instead of 3.85 × 104). Examination of the intermediate steps revealed inconsistent substitution of powers of ten and arithmetic slips typical of token-based generation rather than symbolic computation. Similar issues appeared in heat-transfer coefficient calculations and rearrangement of governing equations. These results reinforce the view that, while ChatGPT can verbalise a correct computational method, it struggles to execute precise, multi-step arithmetic.

3.3.3. Conceptual Errors

Conceptual errors represented the mode of failure across Bloom levels. These occurred when ChatGPT provided fluent explanations that were incompatible with underlying physical principles. Several patterns emerged:

- Overgeneralisation of trends, such as claiming that mass-transfer rate increases linearly with diffusivity in all regimes, regardless of film resistance or hydrodynamic conditions.

- Incomplete mechanism descriptions, e.g., explaining conduction solely through molecular collisions while omitting lattice vibrations or free-electron effects in solids.

- Misinterpretation of dimensional quantities, including treating m4 as a volumetric unit.

- Oversimplified engineering reasoning, such as assuming pressure drop always decreases with pipe diameter without considering Reynolds number or roughness effects.

These errors illustrate that ChatGPT often “knows the words but not the physics”: it can recount familiar patterns but lacks the internal consistency required to maintain causal, mechanistic reasoning across steps.

3.3.4. Contextual and Judgment Errors

Contextual/judgment errors were especially common in higher-order Bloom levels (Analysis, Evaluation, and Creation). These errors emerged when ChatGPT attempted to justify design choices, evaluate assumptions, or synthesise multi-parameter reasoning. Although the responses often sounded balanced and authoritative, they frequently misapplied domain constraints.

Examples include:

- Recommending a shell-and-tube heat exchanger for “ease of cleaning” even when the scenario’s fouling conditions favoured plate-and-frame designs.

- Discussing environmental trade-offs in generic terms without addressing the scenario’s specific operating conditions or emissions profile.

- Proposing design steps for a heat exchanger system that omitted material selection, thermal-duty verification, or pressure-drop constraints.

These errors highlight ChatGPT’s tendency to generate contextually generic evaluations that lack engineering specificity. This aligns with expert observations that judgment—particularly in unfamiliar or constrained scenarios—is one of the most difficult competencies for LLMs to emulate.

3.3.5. Mixed or Ambiguous Errors

Approximately 15% of responses displayed overlapping error categories. A typical mixed error involved a correct conceptual approach, followed by incorrect application of units, ending with a contextually irrelevant justification. For instance, in the aforementioned unit conversion problem, the model correctly described the required transformations but misapplied powers of ten and concluded with an erroneous final magnitude. Such hybrid errors underscore the difficulty in attributing a single cause to failures arising from compounded linguistic, numerical, and conceptual issues.

The shift from factual to conceptual and contextual errors mirrors a transition from information retrieval to knowledge construction, where large language models currently lack domain ontology and situational grounding.

3.4. Response Quality and Coherence

A qualitative reasoning quality evaluation (Table S2) further illuminates this pattern. Table 2 shows the Mean reasoning score declined from 4.9 at Remember to 2.1 at Create. Text coherence remained high throughout, sentences were grammatically correct, logically sequenced, and stylistically fluent. Yet evaluators described higher-level answers as “hollow coherence”: text that reads well but reveals superficial grasp when examined for technical substance.

Representative excerpts showed that at lower levels ChatGPT functioned as an accurate tutor, while at higher levels it resembled an eloquent undergraduate improvising beyond mastery. The model displayed metacognitive mimicry phrases like “it is important to note” or “one possible approach”—which give an impression of critical thought but mask absence of underlying reasoning chains.

3.5. Domain-Specific Observations

Performance varied systematically across the chemical-engineering subdomains represented in the question set, reflecting both the cognitive demands of each area and the density of relevant material in ChatGPT’s training corpus. The strongest performance was observed in Thermodynamics and Heat Transfer, where the model achieved a mean accuracy of approximately 88%. These domains predominantly involve well-established correlations, stable mathematical structures (e.g., equations of states, Fourier’s law, Newton’s cooling law), and consistent conceptual definitions. As illustrated in the heat-transfer explanation question in the Supplementary Information, ChatGPT provided largely correct descriptions of conduction, convection, and radiation, with only minor omissions. Similarly, when prompted with energy-balance or property-calculation tasks, the model showed reliable recall of standard equations and produced coherent problem-solving sequences, even when numerical errors occasionally appeared.

Moderate performance was found in mass transfer and reaction engineering, with a mean accuracy around 72%. These areas demand more nuanced judgement regarding regime identification, parameter selection, and kinetic assumptions. The uploaded outline shows examples of these limitations, such as ChatGPT’s tendency to generalize trends (e.g., assuming mass-transfer rate increases linearly with diffusivity in all regimes) or to describe reaction-rate behavior without referencing mixing, film resistance, or catalyst characteristics. Such errors reflect the model’s difficulty in maintaining mechanistic consistency across multiple interacting variables, particularly when the correct interpretation depends on recognizing the physical regime or dominant resistance.

The lowest performance occurred in process synthesis and design and environmental systems, with a mean accuracy near 55%. These areas require integration of economic, safety, operational, and sustainability constraints—considerations that were frequently absent or only superficially addressed in ChatGPT’s responses. In the design-oriented questions, ChatGPT often produced polished, generic evaluations rather than scenario-specific reasoning. For instance, when evaluating process alternatives, the model tended to default to generalized statements (e.g., “shell-and-tube exchangers are easier to maintain”) even when the scenario involved fouling conditions or process constraints that contradicted its recommendations. In environmental questions, it focused on universal principles (reducing emissions, improving efficiency) while ignoring the quantitative or regulatory context provided in the prompt.

Taken together, these patterns show that ChatGPT’s domain proficiency is strongly correlated with corpus density and structural regularity. Subfields with abundant, formula-driven textbook coverage enable high-accuracy responses, whereas design-intensive or interdisciplinary problems—where authoritative solutions depend on applied judgement rather than standardized equations—highlight the model’s limitations. This reinforces the broader finding that ChatGPT excels at lower-order and mid-level cognitive tasks but struggles when reasoning requires holistic interpretation, trade-off evaluation, or creative synthesis typical of advanced Chemical Engineering practice.

4. Discussion

4.1. Cognitive Competency Profile

The findings of this study delineate ChatGPT’s (model 3.5) cognitive competency profile within Chemical Engineering education under generic, single-prompt interaction conditions.The model demonstrates very strong precision in declarative memory, including definitions, laws and standard formula structures—an outcome consistent with Anderson’s ACT-R theory [23], whereby factual knowledge can be algorithmically stored and retrieved. ChatGPT also shows moderate ability in procedural recall, enabling it to reproduce equations, textbook-style worked examples and common explanatory frameworks with relatively high reliability [24].

However, its capacity for strategic reasoning, contextual judgment, and metacognitive regulation is markedly limited. The pronounced decline in performance observed between the Apply and Analyse levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy signals a cognitive threshold at which causal modelling, symbolic reasoning, and domain-specific interpretation become essential. While ChatGPT is adept at reproducing mathematically structured language—effectively “speaking mathematics”—it does not “think physics,” as it lacks the capacity to assess physical realism, interrogate modelling assumptions, or reflect upon the validity of intermediate reasoning steps. This limitation is consistent with broader literature indicating that large language models optimise linguistic probability rather than causal or mechanistic coherence [5,25]. Importantly, all findings reported in this study pertain specifically to ChatGPT-3.5 operating in an unscaffolded, single-prompt mode and should not be assumed to generalise to newer GPT versions or to pedagogically mediated interaction designs that incorporate iterative prompting, instructor guidance, or reflective constraints.

4.2. Comparison with Human Learning Curves

A useful perspective for interpreting ChatGPT’s competency is to compare its performance with that of undergraduate cohorts in Chemical Engineering. Previous research consistently shows that students perform markedly better on lower-order learning tasks, where accuracy on basic recall items is typically high, while their achievement drops substantially on higher-order or creative problem-solving tasks, which are far more challenging and yield significantly lower success rates [5,26]. The ChatGPT profile observed here mirrors mid-level student competency in procedural reasoning, and ChatGPT frequently outperforms novice learners at lower Bloom levels due to its extensive exposure to structured educational content.

The divergence emerges at higher-order levels. Human learners possess metacognitive awareness, enabling them to recognise inconsistencies, revise reasoning and adapt in response to feedback. ChatGPT, conversely, generates outputs in a non-iterative and non-reflective manner, without the ability to self-correct once an answer is produced. This explains why errors at the Apply level persist despite seemingly correct intermediate steps, and why responses at the Evaluate and Create levels lack the professional judgement expected of engineering graduates. As such, while ChatGPT may support foundational learning, it cannot yet substitute for the reflective and adaptive reasoning characteristic of human expertise.

4.3. Error Mechanisms, Physical Reasoning and Interpretability

Our error analysis shows that conceptual errors were the most prevalent, suggesting that ChatGPT possesses an internal representation based on statistical associations between linguistic tokens rather than causal relationships among physical entities. Consequently, the model is able to replicate the surface structure of an engineering explanation without verifying its validity or underlying logic. This form of epistemic opacity poses risks in technical disciplines, as linguistic fluency may be mistakenly interpreted as expert understanding.

From an interpretability standpoint, our findings reinforce that the optimisation of token probabilities does not ensure physical or numerical reliability. Tasks requiring the integration of multiple equations—such as mass and energy balances or kinetic regimes—often led to internally inconsistent solutions despite the use of correct terminology. This aligns with recent studies showing that GPT-3.5 often understand a mathematical problem conceptually yet still fail in executing sequential calculations [27,28].

4.4. Broader Context: Accuracy, Integrity and AI Literacy

Within STEM education more broadly, ChatGPT has been shown to provide considerable support for writing tasks, conceptual clarification and formative feedback. By leveraging its natural language processing capabilities, ChatGPT can generate accessible explanations and analogies that help grasp intricate ideas. This ability in simplifying scientific information and presenting it a clear, concise manner is crucial for fostering understanding and appreciation in science. As previously mentioned, ChatGPT has the ability to provide personalised tutoring and feedback to students, based on their individual needs and progress and a study by Ansah [29] showed ChatGPT was able to provide personalised maths tutoring to students, resulting in improved learning outcomes; due to providing explanations that were tailored to students’ misconceptions by being able to adapt to their level of understanding [4,30]. However, the technology raises important questions regarding academic integrity, as current detection tools (including GPTZero, Copyleaks and Turnitin) cannot reliably identify AI-generated text [30,31]. This limitation challenges the validity of existing plagiarism-based quality assurance frameworks used in higher education.

Ethically, there is a risk that learners may conflate ChatGPT’s authoritative tone with genuine expertise, creating an “illusion of competence.” In engineering disciplines—where safety, environmental protection and regulatory compliance depend upon accurate reasoning—this risk is significant. As Shoufan notes, although AI-driven personalised feedback can support learning, it also raises concerns regarding data privacy, user profiling and the lack of transparency in model training [32].

4.5. Applicability and Limitations Within STEM and Engineering Domains

Consistent with wider STEM findings, the present study shows that ChatGPT performs best in domains characterised by stable, formula-based structures, such as thermodynamics and heat transfer (accuracy around 88%). By contrast, its performance in design-intensive and context-heavy areas—including process design and environmental systems—was considerably weaker (around 55%). These domains require the integration of economics, sustainability, operability and safety considerations, all of which were often missing or only superficially addressed in ChatGPT’s responses.

Similar patterns have been documented in mathematics, where GPT-3.5 exhibit strong conceptual reasoning but weaker symbolic manipulation [25]. ChatGPT’s borderline pass performance on the US Fundamentals of Engineering examination [28] further supports this interpretation, with strong performance in data-rich topics and weaker outcomes in hydrology, soils and other design-oriented domains. Comparative studies indicate that certain alternative models, such as Galactica, can outperform ChatGPT on technical tasks involving chemical equations and LaTeX [33], whereas Bing Chat may underperform due to reliance on lower-quality web sources [34] but more research is required for comparitive analysis.

4.6. Pedagogical Implications

The pedagogical implications point towards calibrated integration rather than substitution of human educators [35]. ChatGPT is particularly useful for a range of teaching and learning activities [36], e.g.,

- Supporting rote learning and factual revision;

- Generating formative assessment items;

- Producing initial explanatory drafts for students to critique;

- Offering individualised feedback at scale.

In these contexts, ChatGPT functions most effectively as a preparatory or formative tool that reduces cognitive load while preserving instructional intent.

However, a critical pedagogical challenge emerging from generative AI adoption is students’ tendency to conflate linguistic fluency with epistemic correctness. The findings of this study indicate that such risks are most pronounced at higher Bloom levels, where errors are predominantly conceptual, contextual, and assumption-driven rather than factual. Consequently, educators must explicitly teach students to recognise the limitations of AI-generated reasoning and to interrogate outputs with disciplinary judgment. One effective strategy is the deliberate incorporation of metacognitive prompting frameworks, in which students are required to justify assumptions, perform dimensional and physical plausibility checks, or evaluate the feasibility of AI-proposed solutions. This approach repositions ChatGPT from an answer-producing system to a dialogic reasoning partner, thereby fostering reflective engagement rather than passive consumption.

Embedding structured AI critique activities into coursework further strengthens this pedagogical stance. For example, students may be tasked with identifying incorrect assumptions in ChatGPT-generated solutions, verifying intermediate steps through independent calculation, or comparing AI outputs against first-principles derivations and authoritative references. Such activities directly target the Analyse and Evaluate levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy while cultivating metacognitive awareness of AI limitations. Assessment design can reinforce these outcomes by shifting emphasis from final numerical answers to reasoning transparency, including justification of modelling choices, explanation of assumptions, and reflection on the reliability of AI-assisted solutions. In this way, generative AI serves as a catalyst for critical engagement and epistemic development rather than a substitute for engineering judgment or instructional expertise.

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, the question set was expert-curated rather than randomly generated, which may introduce selection bias toward canonical undergraduate problem types. While the problems were drawn from past formal assessments—thereby enhancing the authenticity and curricular relevance of the dataset—this approach necessarily reflects instructors’ judgments regarding representative topics and associated cognitive demands. Second, although high inter-rater agreement was achieved, the use of a limited number of evaluators may constrain the generalisability of scoring interpretations across broader instructional contexts.

The present dataset also represents a single model generation (ChatGPT-3.5) evaluated under controlled, generic prompting conditions. Large language models evolve continuously through incremental updates, and even minor revisions may alter response patterns. Accordingly, the results reported here should be interpreted as a time-specific snapshot of baseline AI performance under realistic student usage conditions, rather than as a definitive statement regarding the long-term or maximal capabilities of generative AI systems. This limitation is inherent to all empirical studies evaluating rapidly evolving AI technologies.

Importantly, the study intentionally focused on text-based reasoning tasks. This design choice reflects current educational practice, as student interaction with ChatGPT overwhelmingly occurs through text-only prompts and responses in coursework, revision, and self-directed learning. Evaluating text-based reasoning therefore provides a pedagogically realistic baseline for understanding how learners are most likely to engage with and interpret AI-generated outputs. An additional practical motivation for this focus is that, at the time of the study, the freely accessible version of ChatGPT offered limited and inconsistent support for visual and graphical inputs, which would have constrained systematic and equitable evaluation across the full problem set.

Nevertheless, this focus introduces limitations for engineering and chemical education, where visualisation and graphical representations—such as process flow diagrams, phase diagrams, schematics, and plots—are central to conceptual understanding and design reasoning. The exclusion of such multimodal elements means that the present findings may underestimate or mischaracterise AI performance in tasks requiring spatial, visual, or diagrammatic interpretation. As contemporary large language models increasingly integrate visual and symbolic processing, further work is required to assess whether multimodal inputs can support more robust forms of engineering reasoning.

Future research will therefore explicitly examine AI performance on visual and diagrammatic reasoning tasks, including the interpretation of engineering schematics, graphical data, and process representations. Work in this direction is currently under way; however, due to the extensive methodological, analytical, and validation demands associated with multimodal evaluation, it falls beyond the scope of the present study and will be reported in future research communications.

In addition, future work should undertake systematic cross-model comparisons (e.g., ChatGPT-3.5 versus GPT-4 and newer generations), explicitly accounting for differences in prompting paradigms, tutor or study modes, and reasoning transparency. Such studies would help clarify whether observed performance gradients across Bloom’s cognitive levels reflect intrinsic architectural constraints of transformer-based models or are primarily shaped by interaction design and pedagogical scaffolding. Further cross-disciplinary investigations may also help determine whether the observed decline in higher-order cognitive performance is domain-specific or generalisable across STEM disciplines.

Addressing these limitations will be essential for establishing safe, effective, and pedagogically sound uses of generative AI in engineering education, as well as for informing curriculum design, assessment strategies, and AI literacy initiatives in higher education.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a systematic, Bloom-level evaluation of ChatGPT’s competence in solving Chemical Engineering problems, using a diverse dataset of questions mapped across six cognitive tiers. The results reveal a clear performance gradient: near-perfect accuracy in factual recall (≈95%) declines steadily through conceptual interpretation and procedural reasoning, reaching only modest performance in creative and evaluative tasks (≈41%). This pattern reflects the inherent limitations of LLMs, which rely on statistical pattern-matching rather than causal reasoning, physical modelling, or metacognitive self-correction.

This decline reflects the underlying nature of LLMs. ChatGPT excels when tasks rely on well-established patterns present within its training data, but it struggles when confronted with problems requiring multi-step calculations, deeper conceptual integration, contextual judgement or genuine creativity. The error analysis reinforces this, showing that most mistakes were conceptual or contextual in nature rather than simple factual slips. The ANOVA confirmed significant differences between the cognitive levels, demonstrating that ChatGPT’s limitations become more apparent as tasks shift from routine recall to analytical and evaluative reasoning.

From a pedagogical perspective, these findings indicate that ChatGPT is most effective when used as a supportive learning tool rather than a stand-alone problem-solver. It can greatly assist with revision, the generation of worked examples and the explanation of fundamental concepts. However, it cannot replace the development of critical thinking, engineering judgement or design reasoning.

Future work should extend this analysis by examining multimodal tasks such as those involving diagrams, schematics or mathematical derivations and by exploring whether iterative prompting can mimic the feedback processes that underpin human learning. Longitudinal studies comparing different model versions would also help to determine whether newer systems show genuine improvements in engineering reasoning. Such continued investigation will be vital in shaping responsible AI adoption in higher education and in developing teaching approaches that balance the strengths of generative models with the irreplaceable capabilities of human learners.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/info17020162/s1, Table S1. Evaluation framework; Table S2. Evaluation Matrix for Reasoning Quality (Aligned to 1–5 Scale).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, S.S. and S.W.; validation, S.S. and S.W.; formal analysis, S.S. and S.W.; investigation, S.S. and S.W.; resources, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X. ChatGPT and AI: The Game Changer for Education. Shanghai Educ. 2023, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Menekse, M. Envisioning the future of learning and teaching engineering in the artificial intelligence era: Opportunities and challenges. J. Eng. Educ. 2023, 112, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, J. Engineering Education in the Era of ChatGPT: Promise and Pitfalls of Generative AI for Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Kuwait, Kuwait, 1–4 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, A.W.; Stöhr, C.; Malmström, H. Academic communication with AI-powered language tools in higher education: From a post-humanist perspective. System 2024, 121, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirelle-Carmen, R.; Gabor, E.; Oancea, M.; Bogdan, S. Ethical Implications of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education. Sci. MORALITAS-Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2025, 10, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R.; Airasian, P.W.; Cruikshank, K.A.; Mayer, R.E.; Pintrich, P.R.; Raths, J.; Wittrock, M.C. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M.; Felder, R.; Brent, R. Active student engagement in online stem classes: Approaches and recommendations. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2020, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vesilind, P.A. The good engineer. Sci. Eng. Ethics 1999, 5, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banstola, P. A Review on Exploring the Use of ChatGPT in Civil Engineering Research Using ChatGPT. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369894728_A_Review_on_Exploring_the_Use_of_ChatGPT_in_Civil_Engineering_Research_using_ChatGPT (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Oss, S. Exploring the Role of AI in Learning and Teaching Thermodynamics: A Case Study with ChatGPT. Phys. Educ. 2024, 06, 2450013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Magerko, B. What is AI Literacy? Competencies and Design Considerations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.T.K.; Leung, J.K.L.; Chu, S.K.W.; Qiao, M.S. Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, R.; Brent, R. Teaching and Learning STEM: A Practical Guide; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pattier, D. ChatGPT and Education: A Systematic Review. Rev. Entropía Educ. 2024, 2, 80–102. [Google Scholar]

- Brazão, P.; Tinoca, L. Artificial intelligence and critical thinking: A case study with educational chatbots. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1630493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, A. The Ethical Implications of AI in Education. Res. Rev. J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial intelligence in higher education: The state of the field. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Porayska-Pomsta, K. The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Practices, Challenges, and Debates; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Krathwohl, D. A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory Into Pract. 2002, 41, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, R.M.; Brent, R. The Intellectual Development of Science and Engineering Students. Part 2: Teaching to Promote Growth. J. Eng. Educ. 2004, 93, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Bothell, D.; Byrne, M.D.; Douglass, S.; Lebiere, C.; Qin, Y. An integrated theory of the mind. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 111, 1036–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskar, M.T.R.; Bari, M.; Rahman, M.; Bhuiyan, M.; Joty, S.; Huang, J. A Systematic Study and Comprehensive Evaluation of ChatGPT on Benchmark Datasets. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 431–469. [Google Scholar]

- Frieder, S.; Pinchetti, L.; Griffiths, R.-R.; Salvatori, T.; Lukasiewicz, T.; Petersen, P.; Chevalier, A.; Berner, J. Mathematical Capabilities of ChatGPT. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.13867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, A.; Dori, Y.J. Higher Order Thinking Skills and Low-Achieving Students: Are They Mutually Exclusive? J. Learn. Sci. 2003, 12, 145–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ruiz, L.M.; Moll-López, S.; Nuñez-Pérez, A.; Moraño-Fernández, J.A.; Vega-Fleitas, E. ChatGPT Challenges Blended Learning Methodologies in Engineering Education: A Case Study in Mathematics. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursnani, V.; Sermet, Y.; Kurt, M.; Demir, I. Performance of ChatGPT on the US fundamentals of engineering exam: Comprehensive assessment of proficiency and potential implications for professional environmental engineering practice. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo-Anu, D.; Ansah, L. Education in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Understanding the Potential Benefits of ChatGPT in Promoting Teaching and Learning. J. AI 2023, 7, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P. ChatGPT: A comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future scope. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, I.; Sarwary, S.; El-Refae, G.; Chabchoub, H. Time to Revisit Existing Student’s Performance Evaluation Approach in Higher Education Sector in a New Era of ChatGPT—A Case Study. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2210461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoufan, A. Exploring Students’ Perceptions of ChatGPT: Thematic Analysis and Follow-Up Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 38805–38818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Kardas, M.; Cucurull, G.; Scialom, T.; Hartshorn, A.S.; Saravia, E.; Poulton, A.; Kerkez, V.; Stojnic, R. Galactica: A Large Language Model for Science. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.09085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, H.; Jörke, M.; Grunde-McLaughlin, M.; Gerstenberg, T.; Bernstein, M.S.; Krishna, R. Explanations Can Reduce Overreliance on AI Systems During Decision-Making. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 7, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, S.; Botha, M.; Ostovar, M. Evaluating Academic Answers Generated Using ChatGPT. J. Chem. Educ. 2023, 100, 1672–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isiaku, L.; Muhammad, A.; Kefas, H.; Ukaegbu, F. Enhancing technological sustainability in academia: Leveraging ChatGPT for teaching, learning and evaluation. Qual. Educ. All 2024, 1, 385–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.