Abstract

This paper presents a computational framework for constructing and analysing a focal legislative citation network. A depth-limited expansion strategy generates subgraphs of the network that capture the local structural environment of a seed Act while avoiding the global hub dominance present in whole-corpus analyses. Centrality measures and community detection show how the seed Act’s perceived influence changes with network radius. To incorporate semantic information, we develop and apply an Large Language Model (LLM)-assisted topic modelling method in which representative keywords and LLM-generated summaries form a compact text representation that is converted into a Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF–IDF) document–term matrix. Although demonstrated on New Zealand’s mental health legislation, the framework generalises to any legislative corpus or jurisdiction. Integrating graph-theoretic structure with LLM-assisted semantic modelling provides a scalable approach for analysing legislative systems, identifying domain-specific clusters, and supporting computational studies of legal evolution and policy impact.

1. Introduction

Legal instruments are formal, authoritative documents created under a legal system and are used to create, amend, apply, or interpret the law. They comprise primary legislation (e.g., Acts of Parliament) and secondary or delegated legislation (e.g., Regulations, Schedules), as well as other legally relevant instruments, such as Bills (proposed laws) and case law (judicial decisions) [1]. These legal instruments are interlinked through various formal and implicit relationships, including citations, amendments, repeals, and judicial interpretations. Collectively, these relationships allow the legislative corpus to be modelled as a legal citation network [2,3]. In mathematics, such a network can be formalised as a graph , where vertices (or nodes) V represent individual legal instruments and edges E represent defined legal relationships (e.g., “instrument A cites instrument B”). Each vertex or edge can be annotated with attributes that are traditionally expressed as binary, scalar, or categorical variables [2,4,5]. However, legal citation networks exhibit high-dimensional and semantically rich attributes that cannot be fully captured using simple numerical or categorical representations. These attributes include the substantive content of legal provisions, contextual cross-references, and interpretative language, all of which are inherently textual and semantically complex. Graphs that encode such rich semantic information are commonly referred to as knowledge graphs. Historically, many computational legal studies have simplified these knowledge graphs into plain graphs with unlabelled or purely numerical attributes. While this simplification has enabled valuable structural analysis, it often overlooks the semantic layer embedded in legal text [6].

Knowledge graph construction typically begins with a corpus of source documents. With the emergence of modern multi-modal AI systems, it is now possible to process documents in a wide range of formats regardless of their age or quality. A few years ago, researchers faced significant challenges when working with historical documents as they were usually available in non-machine-readable formats (e.g., low-quality scanned PDFs), making automated analysis difficult. This required the use of OCR (Optical Character Recognition) tools such as PDF readers or FineReader to convert them into text, often with limited accuracy [7,8,9].

Today, this challenge has largely been mitigated in computational legal research for two primary reasons. First, many jurisdictions now publish legislative documents in machine-readable formats such as XML, JSON, or HTML, typically accompanied by rich structural metadata. A notable example is New Zealand’s Parliamentary Counsel Office [10], which provides the complete legislative corpus in XML format. This representation explicitly encodes document structure, cross-references, and amendment histories. Second, in cases where legal documents are available only as scanned images, recent advances in AI, particularly vision–language models, enable reliable text extraction and layout interpretation, significantly outperforming traditional OCR pipelines [11]. These developments substantially lower the barrier to large-scale, automated knowledge graph construction from legal corpora. Nonetheless, their full potential remains underexplored within computational legal research.

Once textual content is extracted, it must be processed to identify both document-level information and relationships between legal instruments. This processing typically involves Named Entity Recognition (NER) to detect entities such as Act titles, section identifiers, case names, and enactment dates, and Information Extraction (IE) to infer relations including citations, amendments, repeals, and judicial interpretations [12,13,14]. Existing approaches predominantly rely on rule-based NER and IE pipelines, using regular expressions and handcrafted ontologies. While effective in constrained and well-defined settings, these methods are brittle, jurisdiction-dependent, and costly to maintain at scale. Recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly in natural language processing (NLP) and large language models (LLMs), now enable the construction of attributed semantic graphs (knowledge graphs) for citation networks. By integrating textual semantics with structural graph analytics, this approach will provide a more expressive computational representation of legislative corpora, enabling deeper insights into legal evolution, interdependencies, and systemic vulnerabilities [15,16,17]. However, this potential has not yet been fully explored in the context of legislative networks.

Today, LLMs potentially offer a more flexible and context-aware approach to text analysis. Through prompt engineering, LLMs can extract legal entities and relationships directly from unstructured text with high adaptability across jurisdictions, document types, and time periods. This capability is especially valuable when integrating the extracted semantic information into attributed semantic legal citation networks, where node and edge attributes may include vectorised legal text embeddings, topic models, or semantic similarity measures [15,18]. However, rule-based methods remain highly valuable, as LLM-generated results are not always consistent or reproducible. In addition, LLM-based information extraction can be computationally expensive, especially when dealing with lengthy legislative instruments [2,19,20].

With the convergence of open legislative datasets and advanced AI methods, the construction of semantically enriched legislative networks is now both technically feasible and methodologically robust, offering significant potential for computational legal research and policy analysis [10,21].

Once a graph has been created through NER and IE systems, it can be analysed using a range of methods. Such a graph may support legal inference through expert systems or statistical analysis to identify its key structural characteristics [5]. However, there exists a wide range of graph-theoretic approaches that can be applied to derive deeper and more insightful results. Although some researchers have explored this direction, most investigations remain limited, both in the diversity of graph-theoretic techniques applied and in the jurisdictions studied [22]. For example, combining structural graph analytics (e.g., centrality, community detection, robustness analysis) with semantic representations enables richer investigations into legislative systems—such as identifying jurisprudential clusters, mapping the propagation of legal changes, or detecting systemic vulnerabilities [23,24,25].

Most existing computational studies of legislative systems construct and analyse the entire legislative network at once. These full-network approaches are effective for identifying globally important Acts—typically those with high degree centrality, strong interconnectivity, and broad legal influence [2]. However, they often overlook Acts whose significance lies in more specialised, domain-specific contexts, as such Acts can appear peripheral in global rankings despite having critical importance within their thematic or jurisdictional sub-networks.

Furthermore, the majority of prior work represents legislative networks as structurally simplified graphs, where node and edge attributes are limited to basic metadata (e.g., enactment dates, jurisdiction, citation counts). This abstraction neglects the semantic content of legal text, which encodes essential contextual relationships, interpretive nuances, and thematic connections between legal instruments. While some recent studies have begun incorporating NLP into legal network analysis, they typically focus on rule-based extraction from machine-readable formats, with limited use of LLMs for richer semantic representation [2,26,27,28].

The gaps mentioned above limit the ability to examine the local legal environment of a specific Act of interest without interference from dominant network hubs. They also limit the ability to integrate semantic similarity and thematic grouping alongside graph-theoretic analysis. Addressing these limitations requires a method that (1) focuses analysis around a seed Act through targeted, ego-centric, layer-by-layer network expansion, and (2) incorporates LLM-based entity and relation extraction to capture both structural and semantic relationships [29]. These considerations form the primary motivation for this paper.

In this paper, we focus exclusively on Acts, including historical, repealed, and currently active ones. Although court cases and judicial interpretations play a vital role in the broader legal landscape, they fall outside the scope of this research. Our analysis centres on Acts within the New Zealand legislative context; however, the methodologies developed can be generalised to other domains and jurisdictions.

We define the New Zealand Legislative Network (NZLN) as a knowledge graph in which each node represents an Act and each edge represents a legal reference from one Act to another [30]. This network provides a structured way to study the legal corpus and its interconnections. Acts often reference each other through amendments, repeals, and citations [1,2]. These references can be captured as a graph structure, enabling the construction of a legislative network. By systematically extracting these connections, the NZLN can be built to reflect the underlying legal relationships. In this study, we construct a representative subgraph of the NZLN using the full corpus of enacted Acts, including historical and repealed legislation [31]. We then apply a series of graph-theoretic analyses, including centrality measures and community detection, to uncover structural patterns and interpret their relevance in both computational and legal contexts. Specifically, our main contributions are as follows:

- 1.

- A focal framework for legislative network construction. We introduce a depth-limited, layer-by-layer expansion method that centres the analysis on a seed Act. This approach captures its immediate and extended legal environment without distortion from globally dominant hubs, supporting targeted structural and semantic analysis of domain-specific legislation.

- 2.

- A deterministic, rule-based pipeline for high-precision information extraction. Using XML-formatted legislative documents, we build a rule-based system for named entity recognition and relationship extraction that identifies six legal relation types with high precision and recall. This ensures consistency and accuracy in constructing the legislative citation network.

- 3.

- A new LLM-assisted topic modelling method for semantic node embedding. We develop an LLM-assisted LDA approach in which representative keywords and LLM-generated summaries form a compact text representation of each Act. Compared with standard rule-based LDA applied to full legislative text, this method produces higher-coherence topics and cleaner semantic separation.

- 4.

- Integrated structural–semantic analysis of legislative communities. By combining Louvain community detection with LDA-derived semantic embeddings, we identify thematic clusters within the focal network and evaluate their alignment with New Zealand parliamentary committee domains using Jaccard similarity.

- 5.

- A generalisable framework for computational legal analysis. Although demonstrated on New Zealand’s Mental Health Act and its surrounding network, the full methodology—including network construction, semantic embedding, and community interpretation—is scalable to any legislative corpus or jurisdiction.

2. Automated Construction of Focal Legislative Subgraphs

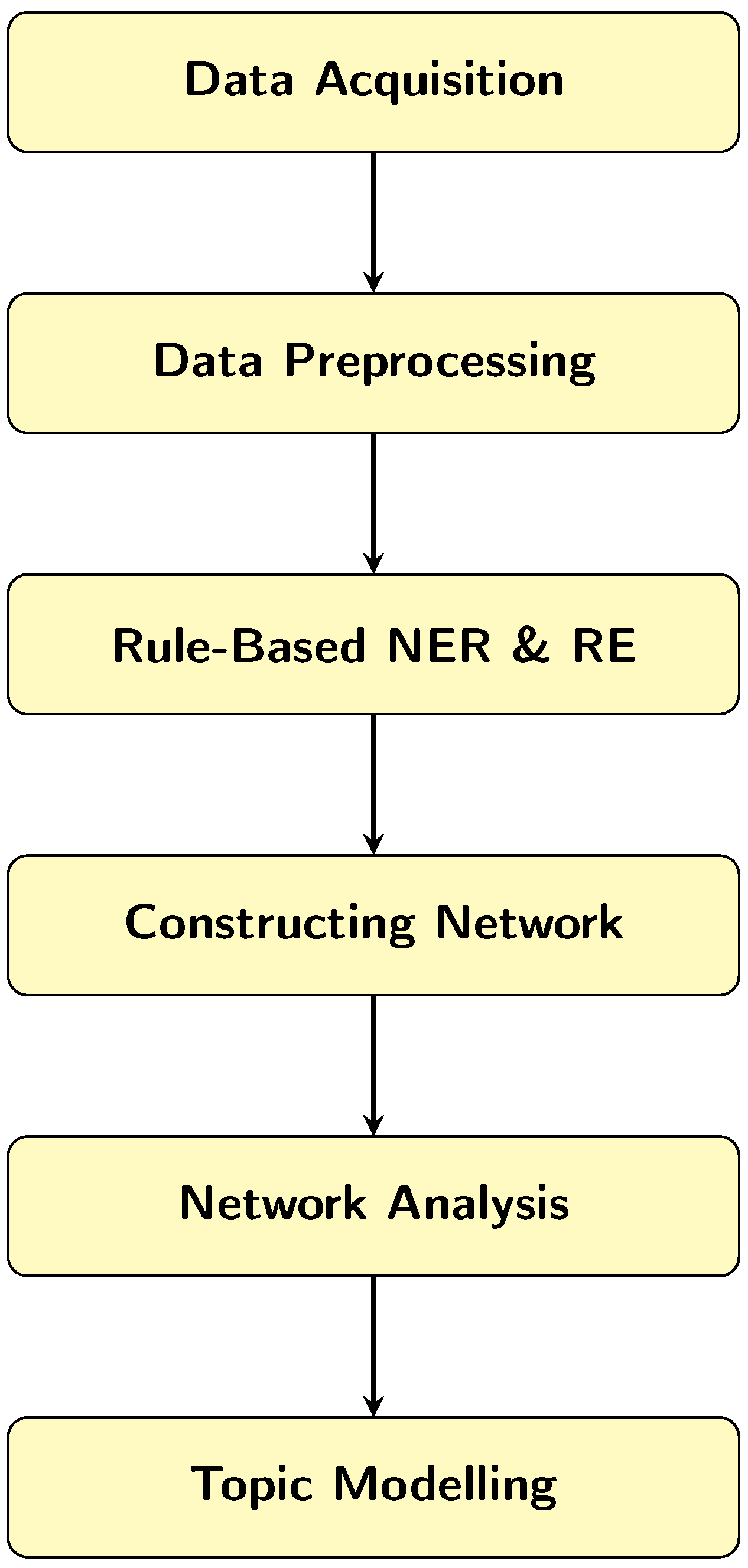

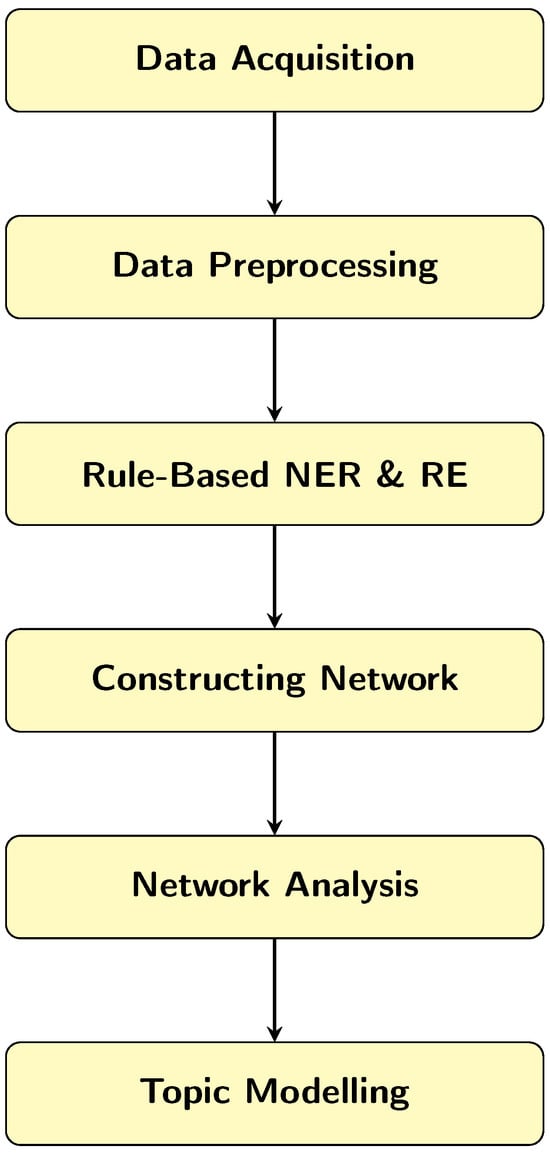

This section describes the overall methodological pipeline used in the study. Figure 1 provides a high-level overview of the workflow, illustrating how legislative texts are processed through rule-based information extraction, seeded network construction, graph-theoretic analysis, and semantic abstraction. Deterministic components used for network construction are clearly separated from the LLM-assisted topic modelling stage, which is applied solely for semantic interpretation and does not affect graph structure.

Figure 1.

High-level workflow for the automated construction and analysis of the New Zealand legislative network, including data extraction, network formation, analysis, and community detection.

We introduce a focal construction approach that includes a layer-by-layer expansion of the legislative network, starting from a seed node representing an Act of interest. In this method, the network is constructed layer-by-layer, where each layer corresponds to legal instruments reachable within a given path length from the seed Act. Unlike full-network approaches, which prioritise global measures across the entire graph, focal construction enables targeted structural and semantic analysis of Acts whose importance may be underrepresented in global rankings due to the presence of highly connected hubs.

For example, if we wish to examine the influence of the Mental Health Act and its connectivity to other Acts, a holistic analysis of the entire legislative network may overlook the finer-grained citation patterns and contextual relationships associated with this Act, especially in a large, dense network. The challenge is analogous to astronomical observation: a wide-field image of the night sky reveals only the largest galaxies, while faint but significant sources of light remain hidden without targeted magnification. By “zooming in” on the seed Act and constructing its surrounding subgraph through controlled, layer-by-layer expansion, our approach allows us to isolate and analyse its immediate and extended legislative neighbourhood, integrating both graph-theoretic properties (e.g., local centrality, clustering) and semantic attributes (e.g., thematic relevance, legal context).

Unlike standard k-hop or ego-network approaches, which extract subgraphs after constructing the full network, the proposed method does not require the entire legislative graph to be generated in advance. Building the whole corpus-level network is computationally expensive and unnecessary for our analytic purpose, as most nodes and edges are irrelevant to a given focal Act. Instead, our method incrementally expands outward from the focal Act using legally defined relation types, producing only the subset of nodes and edges needed for the analysis. This on-demand, relation-guided expansion significantly reduces computational load while maintaining a legally meaningful representation of influence propagation.

This approach allows us to analyse the local influence and legal context of a specific Act while managing computational complexity. This approach can be generalised to any Act within the legislative corpus. To maintain analytical tractability and preserve structural and thematic relevance, the present study limits the network to three layers of legal linkage from the seed. This depth-limited expansion supports targeted structural analysis, facilitates context-aware community detection, and enables focused exploration of how legislative influence propagates through the network.

In this study, the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 serves as the seed node due to its enduring societal significance. From this starting point, the subgraph is expanded layer by layer, including Acts that are directly or indirectly connected through legal references.

We selected the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 as the seed legislation because it is the core statutory framework governing compulsory psychiatric assessment and treatment in New Zealand, and has been the subject of sustained legal, clinical, and policy analysis over several decades [32]. The Act’s centrality is further underscored by New Zealand’s current repeal-and-replace programme aimed at embedding a more explicitly rights-based approach to mental health legislation [33,34]. While this Act is used here as a case study, the proposed subgraph expansion method and suspequent mathematical analysis is not specific to this statute or to New Zealand; rather, it is designed to be applicable to other core Acts and legislative systems where relationships are defined through formal legal references.

2.1. Input Data and Preprocessing

The pipeline begins with XML-formatted legislative documents sourced from the official New Zealand Legislation website. These include currently active, repealed, and historical Acts. In total, the dataset comprises 17,709 Acts. These counts were determined by querying the website’s consolidated and repealed legislation indexes, followed by automated verification during the XML parsing stage to ensure each file corresponded to a unique Act-version pair.

XML parsing enables reliable extraction of section references, metadata tags, and document hierarchy. Preprocessing steps involve standardising references, removing boilerplate text, and formatting content for relation extraction. There is also a normalisation stage to unify variations in legal terminology and citation styles, ensuring that cross-references follow a consistent format. Duplicate or redundant provisions introduced through historical amendments are flagged and removed to avoid spurious links in later stages. Tokenization is performed with legal-domain-specific rules to preserve references as atomic units. The output of this stage is a clean, structured corpus of Acts ready for named entity recognition (NER) and relation extraction.

2.2. Entity and Relationship Extraction

We initially experimented with LLMs and prompt engineering for named entity recognition (NER) and relationship extraction (RE) tasks. In these experiments, the prompt design was informed by the structure of the rule-based extraction pipeline. Specifically, the LLM was instructed to identify legal relationships by detecting indicative phrases associated with amendment, repeal, and citation relations, such as “inserted by,” “repealed by,” and “within the meaning of”. This approach enabled the identification of legal entities and relationships with minimal manual pattern specification. However, we observed a degree of stochasticity across repeated runs, where identical inputs did not always yield identical extractions. Such behaviour is expected in probabilistic language models, and in our experiments the level of variation was relatively low. Nevertheless, the computational overhead associated with repeated LLM inference—particularly for long legislative documents—made this approach resource-intensive. Taken together, the presence of output variability and the higher computational cost motivated the adoption of traditional rule-based methods, which provide deterministic outputs with substantially lower resource requirements and are therefore more suitable for large-scale, reproducible network construction.

The resulting custom rule-based NER and RE engine was designed to identify legal entities and their interrelationships with consistent outputs. Entities include Acts and legislative provisions, while relationships encompass amendment (AMD, AMD_S), repeal (PR, PR_S, R_S), and citation (CIT). The AMD and AMD_S relations capture direct and schedule-based amendments respectively; PR, PR_S, and R_S represent partial and full repeals, either embedded in the main text or listed in schedules; and CIT captures explicit legal references to other Acts. These relationships define the edges of the legislative graph and provide the basis for identifying inter-Act dependencies within the network.

Relationships are extracted using regular expressions triggered by indicative phrases such as “inserted by,” “repealed by,” and “within the meaning of.” These are encoded as directed edges in the legislative graph. Each directed edge points from the citing Act to the cited Act.

In addition to structural relationships, we extract metadata properties for each Act and store them as node attributes within the legislative graph. These properties include the Act’s title, date of enactment, administering agency, and, where applicable, the parliamentary committee responsible for its review. This information is typically available in the structured XML or accompanying metadata and can be extracted using rule-based methods. We also generate a set of representative keywords and a concise executive summary for each Act, which are stored as descriptive properties of the corresponding node. Given the complexity and variability of legislative language, the extraction of keywords and summaries is performed using LLMs guided by prompt engineering. These enriched node attributes enhance the interpretability of the network and allow for content-driven community detection and classification in later stages of analysis.

2.3. Validation of Network Construction

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the network constructed around the seed Act, we conducted a two-part evaluation of the information extraction pipeline, which underpins the graph construction. First, we evaluated the precision of relation extraction across the six predefined relation types. We used stratified random sampling to select 50 extracted relations for each type (300 total) and manually verified each instance against the original XML-formatted Acts available on the official New Zealand Legislation website. For the rule-based extraction system, this evaluation yielded an overall precision of 93%, confirming its effectiveness in accurately identifying legal relationships. We applied the same process to outputs generated by the LLM-based prompt-engineering approach; in its best-performing configuration, this achieved a precision of 86% by average. As noted in the previous section, the LLM-based method exhibits a degree of stochasticity, such that repeated executions on the same input may yield slightly different results. To obtain stable estimates of precision and recall, we therefore executed the method ten times and computed these metrics by averaging the results across runs.

To further assess both precision and recall, we conducted a full-document validation on a stratified sample of 10 Acts. These included the core Mental Health Act, its amendment Acts, and a mix of directly and indirectly connected Acts identified through the network traversal. For each Act, we manually extracted all named entities (e.g., Act titles, section references) and inter-Act relationships, which served as a gold standard. Let

- = True Positives: correctly extracted relationships;

- = False Positives: incorrectly extracted relationships;

- = False Negatives: relationships missed by the extraction system.

For each method, precision and recall are calculated as:

The results are shown in Table 1. The lower performance of the LLM-based approach can be attributed to two main factors. First, legislative language is highly formalised and often context-dependent, making subtle distinctions between relationship types that LLMs can occasionally misinterpret. Second, LLM outputs showed run-to-run variability, where identical prompts applied to the same text could yield different extractions, introducing inconsistencies. While prompt refinement mitigated some of these issues, the rule-based system maintained deterministic behaviour and higher overall accuracy. These results demonstrate that while the LLM-based approach can extract a substantial proportion of legal relationships without explicit rule-writing, the rule-based extraction system achieves higher precision and recall with greater consistency. This accuracy is critical, as the legislative graph underpins key analytical components of the study, including Katz prestige centrality, community detection, and topic modelling, each of which relies on the correctness of the extracted legal relationships to reveal meaningful patterns in the network.

Table 1.

Precision and recall of the rule-based and LLM-based information extraction methods, evaluated using manually validated samples of extracted legal relationships. The rule-based method demonstrates higher accuracy and consistency across both metrics.

2.4. Graph Expansion Strategy

Beginning with the chosen Act (seed Act or node), we applied a breadth-first traversal to construct progressively deeper subgraphs of the legislative network. The seed Act is first processed using the rule-based NER and IE algorithm described above, identifying all referenced Acts along with the type of legal references (the six types defined previously). The expansion process is then repeated for each newly identified node to build the second layer of the network, and once more to reach the third layer. The three-layer limitation was chosen as a deliberate trade-off between thematic relevance and network processability. As the network depth increases beyond three layers, the focal legislation—the Mental Health Act 1992—rapidly loses centrality due to the inclusion of increasingly indirect and weakly related legislative links. Empirically, we observed that beyond the third layer the focal Act no longer appears within the top 50 nodes ranked by Katz centrality, indicating a shift of analytical focus away from the target legislation. Since the objective of this study is to analyse the legislative context centred on the Mental Health Act 1992, deeper expansions were not pursued. During the expansion process, only newly discovered nodes are added and processed, while existing nodes are not re-parsed, preserving computational efficiency and consistency. At the beginning of each iteration, duplicate nodes are merged to ensure each Act is uniquely represented, as the same Act may be referenced via multiple pathways. Each Act is uniquely identified based on its official title and unique legislative identifier, ensuring consistent merging of duplicate nodes. The three-layer limitation was chosen as a deliberate trade-off between thematic relevance and network processability. As the network depth increases beyond three layers, the focal legislation—the Mental Health Act 1992—rapidly loses centrality due to the inclusion of increasingly indirect and weakly related legislative links. Empirically, we observed that beyond the third layer the focal Act no longer appears within the top 50 nodes ranked by Katz centrality, indicating a shift of analytical focus away from the target legislation. Since the objective of this study is to analyse the legislative context centred on the Mental Health Act 1992, deeper expansions were not pursued.

Table 2 presents a summary of the seeded layered subgraphs generated from the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992. At the first layer, the subgraph includes 27 Acts that are directly referenced by the seed Act. The second layer expands the network to 2159 Acts by incorporating references made by the Acts in the first layer. Finally, the third layer results in a subgraph of 6021 Acts, representing approximately 34% of the entire legislative corpus.

Table 2.

Summary of layered subgraphs centred on the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992.

2.5. Document Embedding via Node-Level Topic Modelling

To analyse the semantic structure of the legislative network, topic modelling is applied to the document associated with each node in the graph. This enables each node to be represented not only by its legal citation relationships but also by its underlying thematic content. Two methods are implemented: an LLM-assisted approach, which enriches the input through summarised and filtered content, and a rule-based approach, which operates directly on the preprocessed legislative text. Both methods employ Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) for unsupervised topic discovery, but they differ in input preparation, level of semantic abstraction, and computational requirements. A rule-based LDA method has previously been used by Sakhaee et al. for topic modelling of legal documents [2]. This method is described below.

2.5.1. Rule-Based LDA on Full Legislative Text

This approach operates solely on the complete legislative text extracted from the XML source files. The text is preprocessed using a fully rule-based pipeline consisting of the following:

- Lowercasing all text.

- Tokenising with legal-domain rules to preserve compound references.

- Removing both standard and legal-domain stopwords.

- Lemmatising to reduce inflected forms to base forms.

- Constructing a TF–IDF-weighted document–term matrix.

The LDA model is then applied using the same hyperparameter tuning procedure as in the LLM-assisted method. Because this input retains the full legislative language, including procedural and structural expressions, some topics exhibit a mixture of substantive and procedural terms. However, the method is entirely deterministic and has significantly lower computational cost because it does not require LLM inference. Full details of this technique are provided in [2].

The main limitation of the rule-based approach is its reliance on complete legislative documents, which can be extremely long. Its performance is also highly dependent on the quality of handcrafted rules, which often require document-specific adjustments and may not generalise across the corpus. To address these issues, we propose a novel LLM-assisted LDA method, described in the following section.

2.5.2. LLM-Assisted LDA

This study applies an LLM-assisted topic modelling approach to represent the semantic content of legislative Acts at the node level. The purpose of this approach is to construct a compact textual representation for each Act that captures substantive legal themes while excluding procedural and drafting-related language. These representations are used solely for semantic analysis and do not influence entity recognition, relationship extraction, graph construction, or network expansion.

For each Act, two semantic artefacts are generated: (i) a short summary describing substantive legal content and (ii) a set of representative keywords corresponding to legal concepts and policy themes. These artefacts are concatenated to form the input document for topic modelling.

Prompt Design and Execution Protocol

Summaries and representative keywords are generated using a fixed prompt template applied uniformly across the corpus. The prompt instructs the model to identify the regulatory purpose of the Act and summarise substantive obligations, rights, and mechanisms within a fixed word limit, while excluding procedural, structural, and drafting-related language.

All generations are performed using identical decoding parameters (temperature set to zero), and a single generation pass is used per Act. The LLM is used exclusively for semantic abstraction at the node level. Entity recognition, relationship extraction, graph construction, and network expansion are performed independently using deterministic, rule-based methods. As a result, the structure of the legislative graph and all graph-theoretic analyses are reproducible and unaffected by the LLM outputs.

Reproducibility and Impact of LLM Variability

LLM-generated summaries may exhibit limited lexical variation. This variation does not affect the legislative graph, as the graph structure is constructed independently of the LLM-assisted component. Topic modelling is applied at the corpus level using TF–IDF weighting and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), where document-level variation is attenuated through aggregation across the full set of Acts.

Repeated executions using the same prompt structure and decoding parameters produced consistent topic–word distributions and stable community-level thematic assignments. Consequently, the use of LLM-generated summaries does not introduce instability into the semantic or structural analyses reported in this study.

Preprocessing and Topic Modelling

The concatenated summaries and keywords are preprocessed prior to topic modelling. Preprocessing steps include lowercasing, tokenisation, removal of standard and legal-domain stopwords (e.g., “Act”, “section”), and lemmatisation. The processed corpus is transformed into a TF–IDF-weighted document–term matrix, which serves as the input to the LDA model.

The LDA algorithm is applied using the same hyperparameter tuning procedure as the rule-based approach, with the number of topics and Dirichlet priors selected based on coherence scores. The model outputs include (i) topic–word distributions, identifying representative terms for each topic, and (ii) document–topic distributions, indicating the relative contribution of each topic to an Act.

Example Prompt

The following prompt illustrates the template used to generate summaries and representative keywords for each Act. The same structure is applied uniformly across the corpus, with only the legislative text substituted.

System instruction: You are a legal analysis assistant. Focus on substantive legal content. Exclude procedural and drafting-related language.

User prompt: Given the following legislative Act, complete the tasks below:

1. Produce a summary (maximum 150 words) describing the Act’s regulatory purpose, substantive obligations, rights, and mechanisms. 2. Extract 10–15 representative keywords corresponding to legal concepts and policy themes. 3. Exclude structural or procedural terms such as “section”, “subsection”, “schedule”, “clause”, and citation boilerplate.

Return the output in the following format:

2.5.3. Case Study: Topic Modelling of the Mental Health Act

To illustrate the differences between the two topic-modelling approaches, we apply both methods to the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992, which also serves as the seed Act in the construction of the layered citation network. This Act provides a suitable case study because it is centrally positioned in the network and contains a mixture of substantive, procedural, and cross-domain references.

For interpretability and consistency, each topic is represented by its top ten highest-probability keywords in the LDA topic–word distribution, following common practice in topic-modelling research. Table 3 presents the top three topics and their associated weights for this Act, as generated by the LLM-assisted and rule-based LDA models. The topic weights represent the proportion of the document assigned to each latent topic, and therefore indicate the dominant thematic components extracted by each modelling approach.

Table 3.

Top three topics for the Mental Health Act under LLM-assisted and rule-based LDA approaches.

Under the LLM-assisted method, the dominant topics exhibit higher semantic coherence, with topic weights concentrating on themes closely aligned with clinical treatment, compulsory assessment, and patient rights. This reflects the LLM’s ability to abstract substantive content and suppress procedural and boilerplate language. In contrast, the rule-based method yields topics that blend procedural terminology (e.g., “section”, “order”, “application”) with substantive mental-health concepts. This is expected, as the full legislative text contains a large proportion of structural legal expressions that are not removed by rule-based filtering.

The comparison demonstrates that the LLM-assisted LDA method produces more focused and interpretable topic distributions, whereas the rule-based LDA reflects the syntactic and procedural density of the source text. Interpreting these weights offers insight into how each model captures the thematic emphasis of the Act: higher topic weights indicate greater semantic contribution, while smaller weights correspond to secondary or peripheral themes.

In the LLM-assisted approach, topic keywords tended to be semantically grouped and free of structural tokens, producing concise thematic clusters such as treatment and patient care, community and support services, and rights and legal processes. In contrast, the rule-based method retained procedural terms like “section” and “subsection,” leading to slightly less coherent topics but preserving closer fidelity to the original legislative structure.

3. Katz Centrality Analysis

To evaluate the relative importance of legislative provisions within the seeded network, we applied Katz prestige centrality. Katz centrality explicitly models influence by counting all possible directed paths leading to a node, while systematically down-weighting longer paths to reflect diminishing yet still meaningful legal influence across indirect dependencies. This property is critical in dense, cyclic, directed networks such as legislation networks, where influence is rarely confined to immediate citations alone and often propagates through multiple layers of statutory reference and amendment. In contrast, degree centrality captures only direct references and therefore fails to account for indirect systemic impact; betweenness centrality emphasises shortest paths and brokerage roles, which are less meaningful in a legal corpus where procedural importance does not depend on acting as an intermediary; and closeness centrality becomes unstable in the presence of disconnected components and historical sparsity. Katz centrality also avoids the interpretational limitations of PageRank in this context, as it does not assume random navigation behaviour but instead reflects procedural cascade risk—that is, the extent to which changes to an Act may necessitate reconsideration of other dependent legislation. As argued and demonstrated in [2], these characteristics make Katz centrality particularly well suited for identifying procedurally important legislation in a dynamic legal system, where influence accumulates through layered statutory dependence rather than popularity or traversal efficiency.

Alternative ranking measures were considered but found less appropriate for the present setting. PageRank is widely used for node ranking across many application domains; however, its reliability depends on assumptions that are often violated in evolving or temporally structured networks. Prior work has shown that PageRank’s static formulation is sensitive to network growth dynamics and may fail to identify substantively important nodes across a broad range of parameter settings [35]. These limitations reduce its suitability for legislative networks, where citation structure evolves over time and importance is not solely determined by steady-state flow. Harmonic centrality, as a distance-based measure, assumes that shortest-path proximity corresponds to substantive relatedness. This assumption is weak in shallow, seed-centred legislative networks, where citation depth is intentionally limited and path length does not reliably reflect legal influence [36]. For these reasons, Katz centrality was selected, as it explicitly models attenuated influence propagated through direct and indirect references and aligns with the structural characteristics of curated legislative citation networks.

Katz centrality measure accounts for both direct and indirect influence by summing all paths that lead to a node, with each path weighted by an attenuation factor that decreases with path length. Nodes that receive incoming connections from other highly connected nodes accumulate greater prestige, making this measure particularly suitable for analysing citation-like hierarchical networks such as legislation. Katz centrality was computed on both the two-layer and three-layer subgraphs of the seeded network. The underlying graph was treated as a directed network, where all six legal relationship types—CIT, AMD, AMD_S, PR, PR_S, and R_S—formed the edges.

The centrality scores were obtained using an iterative power method, which approximates the solution to the Katz centrality equation through repeated matrix-vector multiplications. In each iteration, the centrality score of node i is updated based on the scores of its in-neighbours as

where A is the adjacency matrix of the directed graph, is a small attenuation factor, and is a constant baseline centrality (typically set to 1). The process converges when is chosen such that , with being the largest eigenvalue of A. The resulting scores reflect both the immediate connectivity of a node and its embeddedness within longer chains of influence across the legal network.

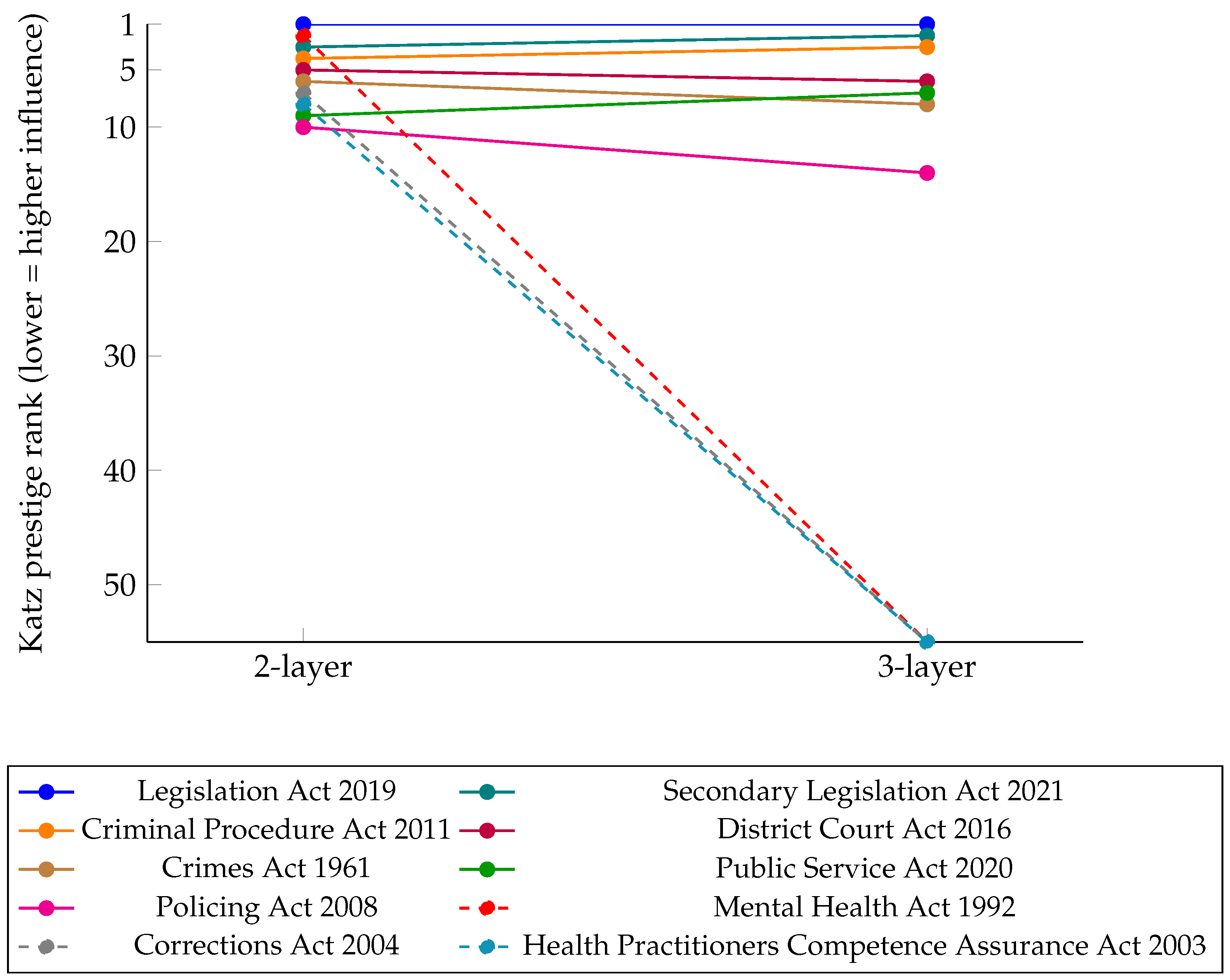

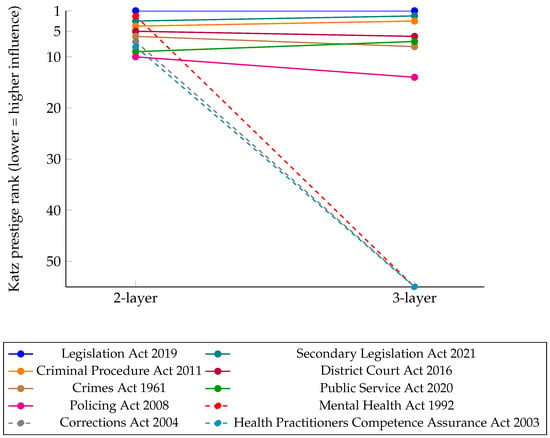

In this study, we report the rankings derived from the Katz centrality scores rather than the raw score values. Rankings offer a more interpretable view of structural importance, particularly when comparing across networks of varying depth and density. A comparison of Katz prestige rankings for the top 10 Acts in the two-layer and three-layer subgraphs is presented in Table 4. Additionally, Figure 2 illustrates how the relative structural influence of the top ten Acts changes when the legislative network expands from a two-layer to a three-layer subgraph centred on the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992. Each line traces the Katz prestige rank of an Act across the two network depths, with lower ranks indicating higher structural influence.

Table 4.

Comparison of the top ten Acts ranked by Katz Prestige Centrality in the two-layer and three-layer legislative subgraphs centred on the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992. Rankings reflect relative structural influence within each network depth.

Figure 2.

Rank shifts of the top ten Acts by Katz prestige centrality between two-layer and three-layer legislative subgraphs centred on the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992. Dashed lines indicate Acts ranked outside the top 50 in the three-layer network.

As expected, the Mental Health Act ranks among the highest in Katz centrality within the two-layer subgraph. This prominence is partly attributable to the network’s construction: since the subgraph is seeded from this Act, it becomes a hub through which many short paths flow, particularly at shallow depths. The centrality of the seed act is not solely a reflection of its true systemic importance but also a structural consequence of being the root node of the subgraph. This construction bias is most evident in the two-layer networks, where a large proportion of paths necessarily pass through the seed node. As the subgraph expands to include a broader portion of the legislative corpus—over 6000 Acts in the three-layer network—this bias diminishes. With a more diverse and interconnected set of nodes, alternative hubs and indirect pathways emerge. As a result, the influence of the seed node becomes more proportionate to its systemic legislative role, and its Katz score declines relative to other structurally significant Acts.

Notably, the Legislation Act 2019 and the Secondary Legislation Act 2021 retain their top positions across both subgraphs, reflecting consistent and broad-based structural influence. This outcome is consistent with the findings reported by [2], in which both Acts were also among the top-ranked in the full legislative network.

By contrast, the Mental Health Act 1992, while ranked second in the two-layer subgraph, falls out of the top 50 entirely in the three-layer version. This sharp decline suggests that its centrality is primarily local, and its broader influence diminishes as the network scope increases. In other words, the Act is locally central but not systemically dominant.

Other Acts exhibit diverse ranking behaviours. The Criminal Procedure Act 2011 and the Public Service Act 2020 maintain relatively high ranks in both subgraphs, indicating stable and widespread relevance. In contrast, the Corrections Act 2004, Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003, and Policing Act 2008 experience notable rank declines. These Acts are more tightly connected to the Mental Health Act 1992 in its immediate neighbourhood but lose prominence in the wider legislative landscape. This divergence highlights the significance of network scale in revealing truly influential legislation.

This analysis demonstrates how Katz centrality can reveal both local and systemic influences of a legal provision. It also highlights the importance of carefully interpreting centrality scores in sub-graphs, especially when the network is constructed around a specific seed node. For policy analysts and legal scholars, this offers a useful quantitative tool to identify key Acts that may serve as legislative anchors or targets for reform.

4. Community Detection

To uncover thematic and structural organisation within the legislative network, we applied a two-stage approach: community detection based on legal relationships, followed by unsupervised topic modelling to extract the semantic focus of each community. This enabled a combined structural-semantic analysis of legal groupings.

4.1. Community Detection Using Louvain Algorithm

The Louvain method is a widely used algorithm for community detection in large networks. It provides a fast and scalable way to identify clusters of nodes that are more densely connected within the group than to the rest of the network. The algorithm works by iteratively optimising the modularity score, which measures the quality of a given community structure by comparing the density of intra-community links to what would be expected in a random network. Modularity values typically range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a stronger community structure. Scores above 0.3 are generally considered to reflect meaningful groupings. When applied to the New Zealand legislative network, the Louvain method enables the detection of groups of Acts that are closely related through legal references such as amendments, repeals, and citations. These communities can offer insights into the structural and thematic organisation of legislation and may align with parliamentary committees or policy areas for further legal and policy analysis.

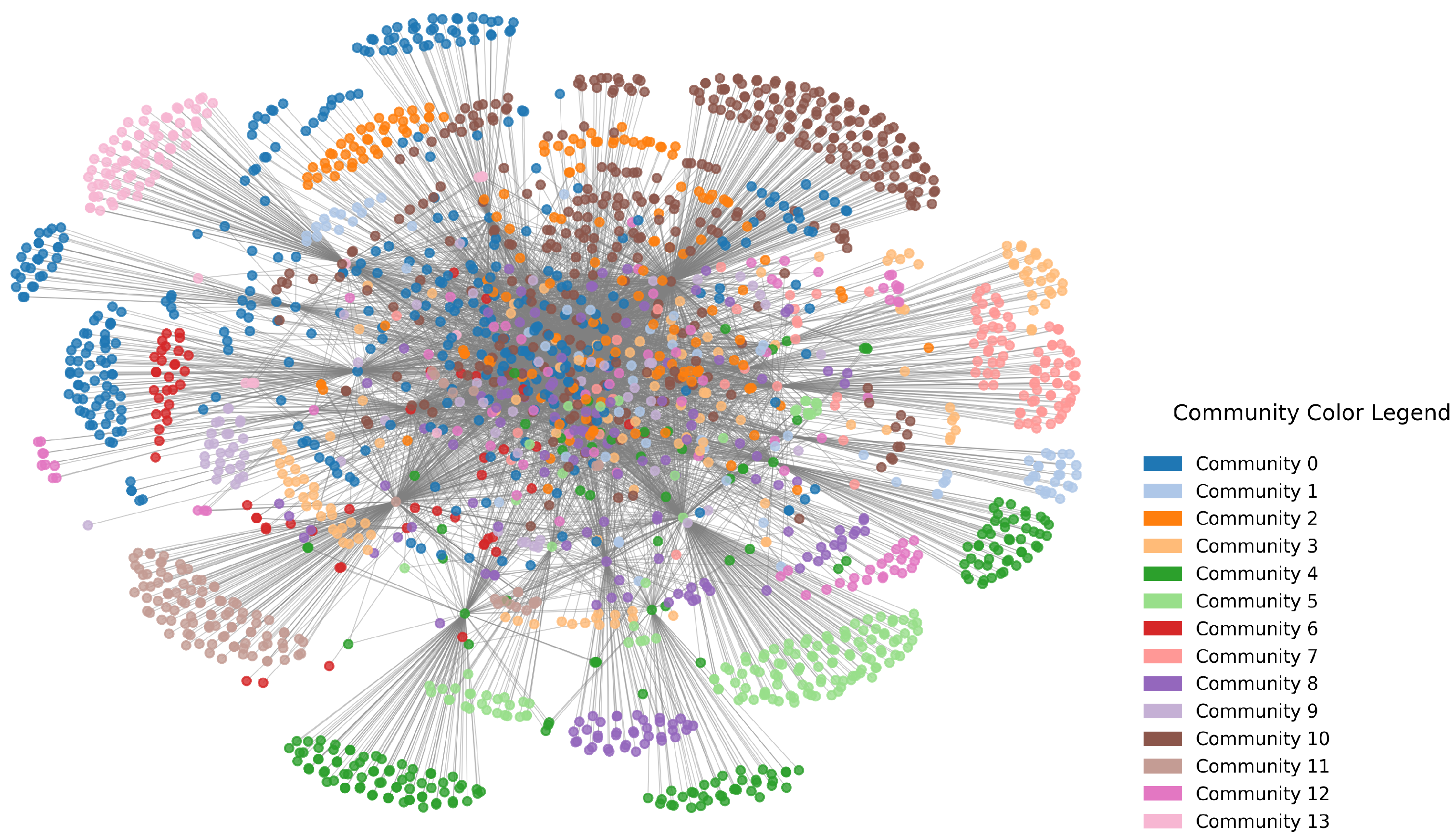

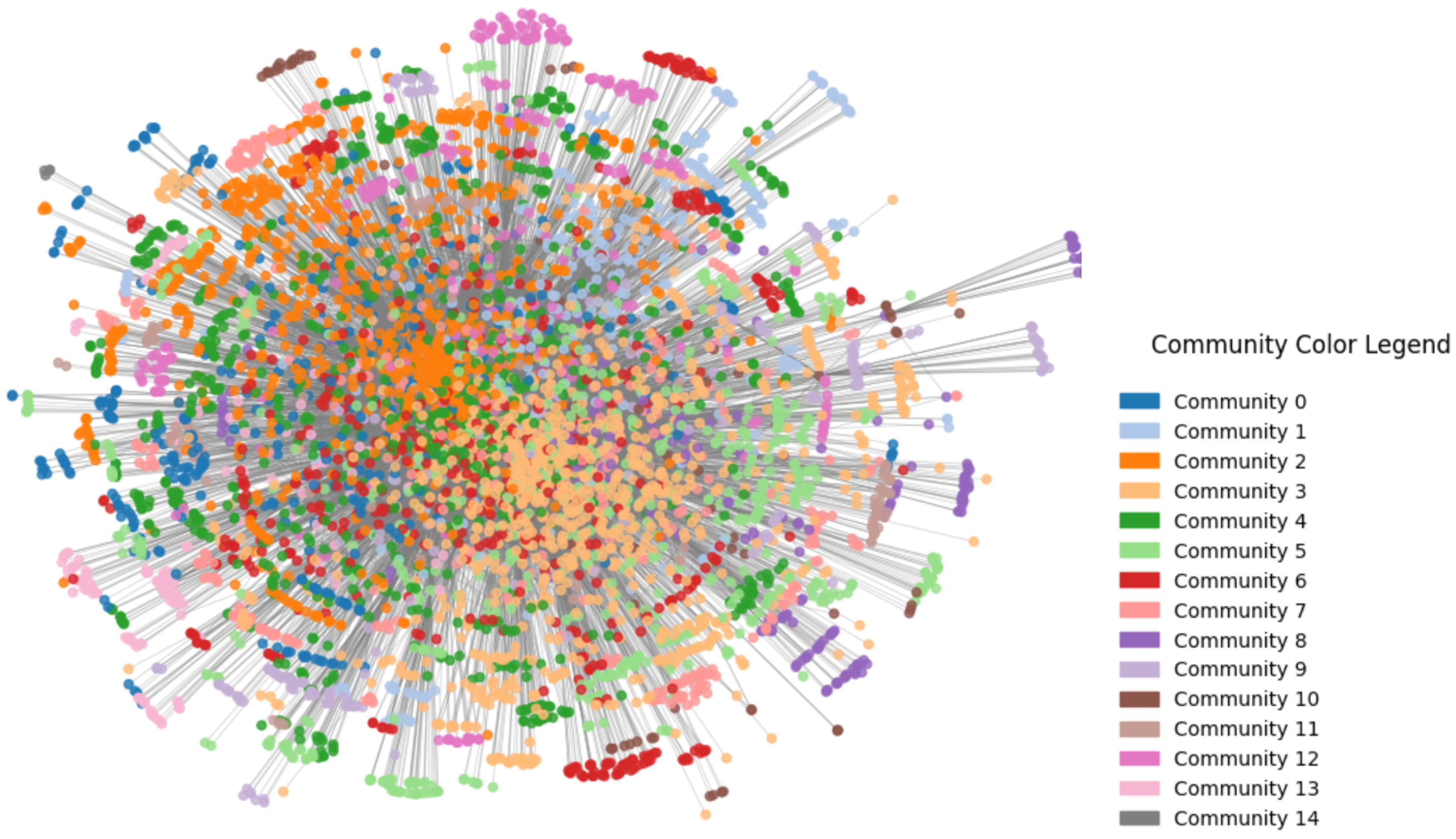

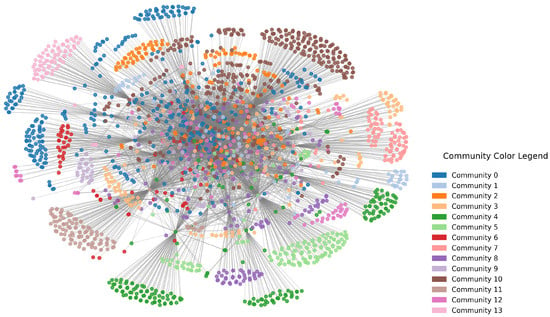

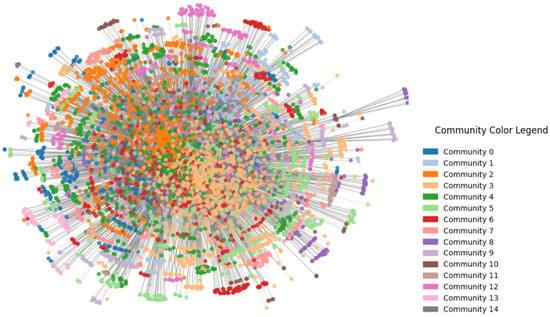

We applied the Louvain algorithm to partition the legislative citation network into communities of Acts that are densely interconnected via legal references. This was done separately for networks constructed at two-layer and three-layer citation depths, with the Mental Health Act serving as the focal node. As visualised in Figure 3, the Louvain method yielded 14 communities (labelled as Community 0 to 13) with a modularity score of 0.393 in the two-layer network. This indicates a moderately strong community structure. As visualised in Figure 4, in the three-layer network the algorithm detected 15 communities (labelled as Community 0 to 14) with a similar modularity score of 0.392.

Figure 3.

Community structure of the two-layer legislative subgraph centred on the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992. Each colour represents a community detected using the Louvain algorithm. This network includes all Acts directly referenced by the Mental Health Act, as well as Acts referenced by those first-layer Acts. The visualisation highlights dense clusters of legally interconnected Acts and the emergence of early thematic groupings within the focal neighbourhood.

Figure 4.

Community structure of the three-layer legislative subgraph centred on the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992. This larger network incorporates three layers of legal references, expanding the subgraph to 6021 Acts (approximately 34% of the New Zealand legislative corpus). Colours denote Louvain-detected communities. Compared with the two-layer network, the three-layer structure reveals broader thematic clusters, increased inter-community linkage, and the emergence of dominant legislative hubs that influence the wider legal system.

Visual inspection revealed that core legal Acts (particularly the Mental Health Act) resided in central, highly connected communities, while more specialised Acts were grouped into smaller, peripheral clusters. These patterns suggest that legal influence propagates outward from foundational Acts, forming dense hubs of related legislation surrounded by narrower, domain-specific statutes. This structure supports targeted policy analysis, where focal Acts can be examined in relation to their immediate legal ecosystem. The detected communities serve as a basis for further thematic classification through topic modelling and can be cross-referenced with parliamentary committee domains to evaluate the alignment between legislative structure and institutional oversight.

4.2. Alignment with Parliamentary Committee Themes

To evaluate the thematic alignment of detected communities with institutional policy domains, the extracted LDA keywords were compared with predefined New Zealand parliamentary committee keyword sets (based on [2]). The Jaccard similarity coefficient was used to quantify the lexical overlap, and each community was assigned to the parliamentary committee label with the highest score. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Parliamentary committee alignment for Louvain communities in the three-layer legislative citation network. Each community is assigned to the parliamentary committee whose predefined keyword set shows the highest Jaccard similarity with the community’s LDA-derived keywords.

Repetition of committee labels across several structurally distinct communities (e.g., Māori Affairs, Finance and Expenditure) indicates that thematic content is distributed across multiple clusters. This fragmentation reduces interpretability and weakens any one-to-one correspondence between structural communities and policy domains. To mitigate this, we apply agglomerative clustering to merge semantically similar Louvain communities into broader macro-communities. The resulting refined groups are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Parliamentary committee alignment for Louvain communities (three-layer network): Columns 4–6.

5. Potential Applications

The framework developed in this study offers a structured and scalable approach to analysing the local and extended legal environment surrounding a focal Act. By combining deterministic rule-based information extraction with LLM-assisted semantic modelling, the methodology produces a representation of legislation that captures both structural dependencies and substantive thematic content. The seeded, depth-limited expansion strategy enables focused analysis of an Act’s immediate legal ecosystem while preventing distortion from globally dominant hubs that typically obscure domain-specific relationships in whole-corpus networks. Importantly, the framework is proposed primarily from a computational perspective, emphasising analytical reproducibility, scalable automation, and methodological clarity. However, the resulting tools also have meaningful practical use for legislators, parliamentary committees, and policy analysts who require a clearer understanding of how legal dependencies propagate across the statutory landscape.

Several potential applications arise from this framework. First, the ability to trace direct and indirect dependencies around a target statute supports legislative impact assessment. Policymakers can use focal subgraphs to anticipate which Acts may require consequential amendment or further review when changes are made to a particular statute. This capability is particularly useful in complex policy areas such as mental health, criminal justice, health services, and social welfare.

Second, by revealing communities of tightly linked Acts, the framework provides insight into thematic clustering and cross-domain interactions. These clusters highlight where policy domains overlap—for example, the interface between mental health legislation, policing powers, and criminal procedure. This information can guide coordinated policy development and help identify where inter-committee collaboration may be needed. The alignment of these clusters with parliamentary committee domains further supports committee workload planning, offering a systematic way to understand which committees are likely to be affected by changes in a given area of law.

Third, the integration of Katz centrality with semantic modelling enables detection of systemic legal vulnerabilities. Highly central Acts may serve as structural bottlenecks, while isolated or weakly connected statutes may be candidates for consolidation or repeal. Legislators and legal drafters can use these indicators to support evidence-based statutory revision and ensure greater coherence across the legal corpus.

Fourth, the semantic embeddings and network visualisations provide a foundation for drafting assistance and regulatory technology (RegTech) tools. These tools can support automated consistency checks, identify relevant cross-references, or highlight gaps where thematic or structural alignment is absent. For legislators and parliamentary offices, such tools can improve the drafting process and reduce the risk of unintended omissions or contradictions.

Finally, because the pipeline relies on machine-readable legislative data and generalisable computational techniques, it is well suited to cross-jurisdictional comparison and temporal analysis. This allows researchers and policymakers to study how legal ecosystems evolve over time, how reforms propagate through dependent provisions, or how the structure of legislation differs between countries. These capabilities extend the framework beyond theoretical interest and offer practical value for long-term legislative planning and evaluation.

Overall, the proposed approach demonstrates how computational methods—including graph theory, information extraction, and semantic modelling—can provide legislators, analysts, and legal scholars with clearer visibility of the dependencies and thematic relationships embedded within complex statutory systems. Future work may extend this framework to incorporate judicial decisions, support real-time interactive exploration tools, or model the temporal dynamics of legislative change.

While the empirical evaluation in this study is based on New Zealand legislation, the proposed framework is not jurisdiction-specific. Core components of the approach—including relation-type extraction, focal and depth-limited network expansion, graph-theoretic analysis, and semantic abstraction—are independent of any single legal system. Jurisdiction-specific elements are limited to the naming conventions used to express amendment and citation relationships and the structure of consolidated Acts, both of which are encoded through configurable rule definitions. These elements can be adapted to other legislative corpora without altering the underlying methodology. This distinction is intended to support assessment of the framework’s transferability to other jurisdictions.

6. Conclusions

This study develops a computational framework for the automated construction and semantic analysis of a focal legislative citation network, using the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 as a case study. While the analysis is anchored in this specific Act, the methodology is fully generalisable and can be applied to any legislative instrument or policy domain.

By combining deterministic rule-based information extraction with LLM-assisted semantic modelling, the framework produces a richer and more interpretable representation of legislative structure than citation-only graphs. The seeded, layer-limited expansion approach enables focused exploration of how influence propagates outward from a chosen Act, avoiding the dominance of globally influential hubs that typically obscure domain-specific relationships in whole-corpus networks. Results show that the Mental Health Act appears locally central in shallow networks but becomes less influential at greater depths, underscoring the importance of scale when interpreting legal network metrics.

Semantic embedding through topic modelling further enhances interpretability. The LLM-assisted LDA method yields higher-coherence topics and clearer thematic separations than the rule-based method, which is affected by procedural and boilerplate language. When integrated with Louvain community detection, these topic-based embeddings support meaningful grouping of Acts and improve alignment with parliamentary committee domains.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that integrating graph-theoretic structure with LLM-assisted semantic analysis produces a more expressive and analytically useful representation of legislative systems. The approach is adaptable to any jurisdiction, can scale to large corpora, and supports applications in policy evaluation, legislative reform, impact assessment, and computational legal research. Future work may extend the framework to incorporate judicial decisions, model temporal evolution in legislation, and conduct cross-jurisdictional comparisons to study systemic legal change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A., M.I., N.S. and S.G.; Methodology, I.A., M.I., N.S., S.G. and P.R.; Software, I.A., M.I., S.G. and P.R.; Validation, I.A., M.I. and P.R.; Formal analysis, I.A. and M.I.; Investigation, I.A., M.I. and P.R.; Resources, I.A.; Data curation, I.A., M.I. and P.R.; Writing—original draft, I.A., M.I. and S.G.; Writing—review & editing, I.A. and N.S.; Visualization, I.A., M.I. and P.R.; Supervision, I.A. and N.S.; Project administration, I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All code used for information extraction, network construction, topic modelling, and dynamic visualisation in this study, based on rule-based method, is publicly available in the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/maryamild/Thesis (accessed on 14 January 2026).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used artificial intelligence-assisted technologies for the purposes of refining the language and enhancing the readability of our text. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- New Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. The Authoritative Source of New Zealand Legislation. 2018. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- Sakhaee, N. Structure and Evolution of Legislation Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vidaković, D.; Gostojić, S.; Kovačević, A. Serbian Legislation as a Network. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information Society, Technology and Management (ICIST 2018), Kopaonik, Serbia, 11–14 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, T.G. Network Science: Theory and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Börner, K.; Sanyal, S.; Vespignani, A. Network science. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 537–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulis, E.; Humphreys, L.; Vernero, F.; Amantea, I.A.; Di Caro, L.; Audrito, D.; Montaldo, S. Exploring Network Analysis in a Corpus-Based Approach to Legal Texts: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the COUrT@ CAiSE, Grenoble, France, 8–12 June 2020; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pappula, K.K.; Rusum, G.P. Multi-Modal AI for Structured Data Extraction from Documents. Int. J. Emerg. Res. Eng. Technol. 2023, 4, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Abdul Rahman, A.N.; Ho Abdullah, I.; Zainuddin, I.S.; Jaludin, A. The comparisons of ocr tools: A conversion case in the malaysian hansard corpus development. Malays. J. Comput. (MJoC) 2019, 4, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvrdy, P.; Long, J.; Christiansen, L.L. Curators to the Rescue: New Strategies for Making Legacy Data Accessible to the Public; Technical Report; United States, Department of Transportation, National Transportation Library: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. New Zealand Legislation (XML). 2024. Available online: https://legislation.govt.nz/subscribe/ (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Sukh, A. OCR-Free Document Understanding Using Vision-Language Models. Ph.D. Thesis, Ukrainian Catholic University, Lviv, Ukraine, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sharnagat, R. Named Entity Recognition: A Literature Survey; Center for Indian Language Technology: Mumbai, India, 2014; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, A.; Affendey, L.S.; Mamat, A. Named entity recognition approaches. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2008, 8, 339–344. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Xiao, C.; Tu, C.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M. How does NLP benefit legal system: A summary of legal artificial intelligence. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.12158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, A. Leveraging knowledge graphs and LLMs to support and monitor legislative systems. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Boise, ID, USA, 21–25 October 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 5443–5446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Bruijn, M.; Wieling, M.; Vols, M. Combining topic modelling and citation network analysis to study case law from the European Court of Human Rights on the right to respect for private and family life. Artif. Intell. Law 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koniaris, M.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Vassiliou, Y. Network analysis in the legal domain: A complex model for European Union legal sources. J. Complex Netw. 2018, 6, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J. LLM-DER: A Named Entity Recognition Method Based on Large Language Models for Chinese Coal Chemical Domain. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.10077. [Google Scholar]

- Chiticariu, L.; Li, Y.; Reiss, F. Rule-based information extraction is dead! long live rule-based information extraction systems! In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–21 October 2013; pp. 827–832. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Dong, B.; Guerin, F.; Lin, C. Compressing context to enhance inference efficiency of large language models. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Singapore, 2023; pp. 6342–6353. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Qian, L.; Liu, P.; Liu, T. Construction of legal knowledge graph based on knowledge-enhanced large language models. Information 2024, 15, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupette, C.; Beckedorf, J.; Hartung, D.; Bommarito, M.; Katz, D.M. Measuring law over time: A network analytical framework with an application to statutes and regulations in the United States and Germany. Front. Phys. 2021, 9, 658463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Zeng, A.; Fan, Y.; Di, Z. Robustness of centrality measures against network manipulation. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2015, 438, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Iyengar, S. Centrality measures in complex networks: A survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.07190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, S. Community detection in graphs. Phys. Rep. 2010, 486, 75–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, H.O.; Costa, R.; Silvestre, G.; Souza, E.; da Silva, N.F.; Vitório, D.; Moriyama, G.; Martins, L.; Soezima, L.; Nunes, A.; et al. UlyssesNER-Br: A corpus of Brazilian legislative documents for named entity recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Processing of the Portuguese Language, Fortaleza, Brazil, 21–23 March 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidis, I.; Chalkidis, I.; Koubarakis, M. Named entity recognition, linking and generation for greek legislation. In Legal Knowledge and Information Systems; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, K.M.; Yang, J.S. Network structure reveals patterns of legal complexity in human society: The case of the Constitutional legal network. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litaina, T.; Soularidis, A.; Bouchouras, G.; Kotis, K.; Kavakli, E. Towards llm-based semantic analysis of historical legal documents. In Proceedings of the SemDH2024: First International Workshop of Semantic Digital Humanities, Co-Located with ESWC2024, Hersonissos, Greece, 26–27 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, D.A. Graph Theory; American Mathematical Soc.: Providence, RI, USA, 2020; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Legal Information Institute. Free Access to Legal Information in New Zealand. 2018. Available online: https://www.nzlii.org (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Soosay, I.; Kydd, R. Mental health law in New Zealand. BJPsych Int. 2016, 13, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health (New Zealand). Repealing and Replacing the Mental Health Act. Page Updated 20 November 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/regulation-legislation/mental-health-and-addiction/repealing-and-replacing-the-mental-health-act (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- New Zealand Parliament. Mental Health Bill (Government Bill)—General Policy Statement (Repeals and Replaces the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992). 2024. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/bill/government/2024/0087/7.0/096be8ed81e9da7c.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Mariani, M.S.; Medo, M.; Zhang, Y.C. Ranking nodes in growing networks: When PageRank fails. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochat, Y. Closeness centrality extended to unconnected graphs: The harmonic centrality index. In Applications of Social Network Analysis (ASNA); VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.