Abstract

Machine learning (ML) has become a cornerstone of critical applications, but its vulnerability to data poisoning attacks threatens system reliability and trustworthiness. Prior studies have begun to investigate the impact of data poisoning and proposed various defense or evaluation methods; however, most efforts remain limited to quantifying performance degradation, with little systematic comparison of internal behaviors across model architectures under attack and insufficient attention to interpretability for revealing model vulnerabilities. To tackle this issue, we build a reproducible evaluation pipeline and emphasize the importance of integrating robustness with interpretability in the design of secure and trustworthy ML systems. To be specific, we propose a unified poisoning evaluation framework that systematically compares traditional ML models, deep neural networks, and large language models under three representative attack strategies including label flipping, random corruption, and adversarial insertion, at escalating severity levels of 30%, 50%, and 75%, and integrate LIME-based explanations to trace the evolution of model reasoning. Experimental results demonstrate that traditional models collapse rapidly under label noise, whereas Bayesian LSTM hybrids and large language models maintain stronger resilience. Further interpretability analysis uncovers attribution failure patterns, such as over-reliance on neutral tokens or misinterpretation of adversarial cues, providing insights beyond accuracy metrics.

1. Introduction

Machine learning has become a cornerstone in critical domains such as healthcare, finance, autonomous driving, and content moderation. Its performance and reliability are heavily dependent on large-scale, high-quality data. Since data plays a foundational role in model training, any manipulation can directly affect the learning process and decision outcomes [1,2], leaving machine learning systems highly vulnerable to data-centric threats, particularly data poisoning [3,4]. Poisoning strategies are diverse, including label flipping, data corruption, and adversarial insertions; although differing in implementation, all can disrupt model training and pose serious challenges to both the learning process and the stability of downstream predictions. Once compromised, such attacks may cause significant performance degradation and systemic misjudgments, and in safety-critical scenarios, even lead to severe risks.

In recent years, a number of studies have investigated the effectiveness of poisoning attacks, mainly focusing on their impact on model performance, the implementation of different attack strategies, and possible defenses [1,2,3,4]. For example, Tavallali et al. [1] proposed a label-flipping method combined with class modality and a nearest neighbor defense technique; however, their study concentrated largely on measuring defense performance rather than analyzing internal model behaviors in detail. Lu et al. [2] analyzed phase transitions in model-targeted indiscriminate poisoning across different settings; however, while their work revealed stage-wise effects, it lacked a deeper explanation of how decision pathways were actually reshaped. Zhang et al. [3] examined Naive Bayes performance under artificially introduced label noise; however, they did not explore which specific features were driving misclassification under poisoning conditions. Manthena et al. [4] surveyed explainability approaches in the context of malware analysis; however, they did not investigate how XAI methods perform when exposed to poisoning scenarios. Overall, no comprehensive framework currently exists for systematic evaluation across different models, and most studies give limited attention to model behaviors and interpretability.

To fill the gap in systematic evaluation of model behaviors under poisoning, we propose a unified framework that jointly measures robustness and interpretability. The framework covers three common poisoning strategies, namely label flipping, data corruption, and adversarial insertion, applied in a phased manner, e.g., 30%, 50%, and 75% to simulate different levels of adversarial pressure. We evaluate a diverse set of models, including traditional classifiers, deep neural networks, hybrid Bayesian models, and pre-trained transformer models such as DistilBERT, and each model is trained and tested under progressive poisoning to reveal both architecture-specific weaknesses and general patterns. To go beyond accuracy metrics, we integrate Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) into the post-evaluation pipeline. LIME perturbs poisoned inputs and builds sparse surrogate models to trace attribution drift, failure modes, and resilience patterns. The method not only reveals the observable manifestations of model failures but also explains their underlying mechanisms and potential causes. Experimental results show that the framework provides consistent and reproducible insights into both quantitative degradation and qualitative explanation. The main contributions of this work are: (i) We propose a unified evaluation framework to measure robustness and interpretability under poisoning attacks; (ii) We conduct phased experiments with three representative poisoning strategies across a comprehensive set of models; (iii) We integrate LIME into the analysis to capture attribution drift and reveal model-specific failure modes. The evaluation pipeline itself is modular and reproducible, enabling extension to additional datasets and attack types in future work. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on data poisoning and interpretability in machine learning. Section 3 presents our poisoning framework, including model setup, poisoning design, and LIME integration. Section 4 outlines the results and key findings. Section 5 provides an interpretability-driven discussion of model behavior under attack and outlines future directions. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Data Poisoning Attacks in Machine Learning

Data poisoning has been studied from multiple perspectives, including attack effectiveness, strategy design, and defenses [5,6,7,8]. DirtyFlipping [5] uses dirty labels and audio triggers to achieve high attack success without harming clean accuracy, while Ji et al. [6] showed that label-flipping in federated learning alters parameters of targeted classes, degrading class-specific accuracy even when global performance remains stable. Truong et al. [7] further revealed that attack outcomes depend on trigger patterns and model architectures, indicating architecture-specific vulnerabilities. Extending to LLMs, TrojLLM [8] demonstrated that poisoning discrete text prompts can compromise GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 in black-box settings. Overall, these works highlight the diversity of poisoning strategies but focus mainly on attack outcomes, with limited exploration of internal model behaviors or cross-architecture effects.

2.2. Defenses and Robust Training Strategies

Defense methods span detection-based filtering and robust training. Jebreel et al. [9] applied UMAP to identify malicious updates in federated learning, outperforming PCA-based baselines by better separating poisoned from benign gradients. Robust training, in contrast, seeks to make models inherently resilient. Liu et al. [10] proposed FRIENDS, which injects optimized “friendly” noise to counteract poisoning, offering strong protection with minimal accuracy loss. Truong et al. [7] showed that retraining with even a small clean dataset can effectively mitigate backdoors, underscoring the enduring value of clean data. Other works explored adversarial training, ensembling, or data sanitization as complementary strategies. These defenses demonstrate promising ideas but often target narrow settings, e.g., image classifiers, federated learning, or specific triggers, and are evaluated mainly by restored accuracy. What remains missing is a systematic understanding of how defenses interact with different attacks and architectures, and why robustness does or does not transfer across domains.

2.3. Explainable AI for Robustness and Security

Explainable AI (XAI) is increasingly used in safety- and security-critical domains to improve transparency and diagnose hidden vulnerabilities. Studies show that interpretable models [11,12] and post hoc methods such as LIME [13] can enhance trust in intrusion detection systems, while more comprehensive frameworks like XAI-IDS [14], XAI-IoT [15], and XAI-ADS [16] apply SHAP and related techniques to identify critical features in domains ranging from network security to autonomous driving. These works demonstrate that XAI not only increases transparency but also guides feature selection and model improvement. However, its use against data poisoning remains largely unexplored. Poisoned models may embed backdoors or distorted class boundaries that evade accuracy-based evaluation but could be revealed through interpretability. An explainability-driven analysis of poisoned models is therefore essential to uncover internal failure modes and to design more principled defenses.

In this paper, we propose a unified framework to evaluate model resilience. We employ three poisoning strategies (label flipping, data corruption, and adversarial insertion) at increasing levels of severity against a diverse set of models, from traditional classifiers to transformers. We then integrate LIME for an interpretability-driven analysis to reveal internal failure modes, moving beyond conventional performance metrics.

2.4. Theoretical Impact on Learning Dynamics

Each poisoning strategy perturbs the learning process in distinct mathematical ways and aligns with observations reported in prior studies. Under label flipping, the empirical risk minimization objective is altered by replacing the true label y with an incorrect . For cross-entropy loss

a flipped label forces optimization to minimize , effectively inverting gradients and shifting decision boundaries, a behavior consistent with prior analyses of label-flip sensitivity in classical models [3,6]. Traditional linear classifiers and decision trees, which rely directly on label-feature correlations, therefore experience rapid degradation under this type of poisoning.

Data corruption injects high-entropy noise into inputs and increases the variance of feature estimates. Shallow bag-of-words models absorb this corruption as inflated non-informative term frequencies [17], while neural architectures such as MLPs and CNNs propagate the noise through hidden activations, reducing filter stability and feature selectivity [18]. These effects weaken class separation even in the absence of label manipulation.

Adversarial insertions, which embed syntactically valid but semantically contradictory phrases, operate through a different mechanism by creating competing gradient signals within each poisoned sample. Such semantic interference has been noted in prior studies of text-based adversarial triggers [8]. Sequence models like LSTMs experience hidden-state dilution, while uncertainty-aware hybrids such as BNN+LSTM dampen this interference through Bayesian regularization [19]. Transformers exhibit relative resilience because multi-head self-attention distributes importance across contextual tokens, reducing the dominance of adversarial cues, consistent with the robustness trends observed in attention-based architectures [20].

Together, these mechanisms clarify why linear models collapse quickly, neural networks degrade gradually depending on noise structure, and Transformer-based or Bayesian models maintain robustness by compensating for poisoned gradients or redistributing attention toward trustworthy lexical signals.

2.5. Broader Context in Machine Learning System Security

Beyond poisoning-focused studies, recent work in ML system security highlights broader challenges such as robustness to distribution shifts, model extraction, and adversarial manipulation across domains including vision, speech, and federated learning. Contemporary surveys emphasize the need for unified evaluation frameworks capable of probing both reliability and interpretability under adversarial pressure [21,22]. Research on deep learning security further notes that model fragility often emerges from representational bottlenecks or shallow attention to salient features, underscoring the importance of architectures that maintain stable attribution patterns under attack [4]. While our study centers specifically on poisoning, this broader literature motivates the combined robustness–interpretability perspective adopted here and situates our contribution within ongoing efforts to build transparent and trustworthy ML systems.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Framework

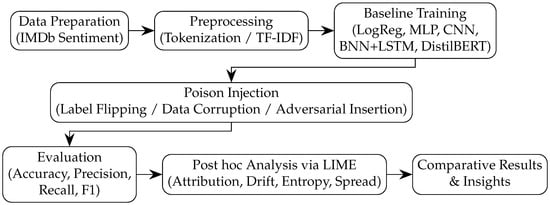

To systematically evaluate model robustness and interpretability under data poisoning attacks, this study adopts a structured experimental pipeline, as illustrated in Figure 1. First, we establish a precise performance baseline by preparing and training all evaluated models on a clean, un-poisoned dataset. Next, we quantify the model’s performance degradation by injecting various types of malicious data into the training set. Specifically, we employ one of three strategies, i.e., Label Flipping, Data Corruption, or Adversarial Insertion, at increasing severity levels of 30%, 50%, and 75%.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed framework.

The selected poisoning ratios (30%, 50%, 75%) represent three canonical stress levels used in robustness testing: low-intensity stealth poisoning, moderate disruption, and extreme degradation. Several studies observe that performance degradation becomes measurable around 20–30% poisoning [1,17], that 50% represents a practical midpoint where models begin to expose architectural vulnerabilities [2], and that performance often collapses when a majority of the data (⩾70%) is adversarially manipulated [23]. Following these conventions, our severity levels were chosen to (1) align with prior empirical practice, (2) provide interpretable low/mid/high stress conditions, and (3) reveal potential phase-transition behaviors that have been highlighted in recent work on poisoning reachability [2]. These thresholds provide a balanced spectrum for observing phase transitions in model stability without requiring full retraining across infinitesimal increments.

After the models are retrained on these poisoned datasets, they are evaluated against a clean test set to measure their robustness. Finally, the process moves beyond traditional performance metrics by utilizing the LIME framework for a post hoc analysis, aiming to qualitatively investigate how and why each model’s internal decision-making process fails under adversarial pressure.

3.2. Preprocessing & Reproducibility Details

To support reproducibility, all models in this study share a consistent preprocessing pipeline. Text is tokenized using the IMDb standard tokenizer, then truncated or padded to a fixed sequence length of 300 tokens for CNN, BNN+LSTM, and DistilBERT inputs, ensuring uniform dimensionality across architectures. Traditional models receive the untruncated text, which is vectorized using TF-IDF. Padding uses a zero-index token reserved exclusively for sequence alignment and masked appropriately for Transformers. For data corruption attacks, a fixed corruption phrase is used to maintain comparability across experiments as it employs synthetic or semantically neutral noise [1,17]. These preprocessing and corruption design choices ensure that results can be closely reproduced and that performance differences arise from model behavior rather than input irregularities.

3.3. Model Definitions and Implementation Framework

The experimental pipeline of this study begins with the standardized processing of data, upon which the models for subsequent evaluation are defined. This process aims to establish a unified and reproducible benchmark for all following poisoning attacks and robustness analyses. First, we define the experimental dataset as D, which consists of a training set and a test set , i.e., . Each sample in the dataset is composed of a raw text input and its corresponding label . Subsequently, the raw text data is transformed into a numerical format comprehensible to machine learning models via a preprocessing function , such that . This function is specified according to the target model architecture: for traditional models, is a function that converts text into high-dimensional feature vectors, e.g., via TfidfVectorizer for deep learning and Transformer models, is a function that performs tokenization, padding, and truncation to generate numerical token sequences.

For CNN, Vanilla/Regularized MLP, and BNN+LSTM, we set a fixed input length of 300 tokens, using right-truncation and right-padding (post-padding) with a single PAD token to ensure consistent shapes under all poisoning ratios and attack types. For DistilBERT with LoRA, we use the Hugging Face tokenizer with , , and padding , with right-padding. Consequently, any tokens appended by corruption or adversarial insertion beyond the maximum length are deterministically truncated, preserving comparability and reproducibility of inputs across models.

Next, a model , defined by parameters , is trained on this processed clean data . During training, the model learns the optimal parameters by minimizing a loss function :

The output of this stage is a set of optimized baseline models , whose initial performance is precisely recorded to serve as a reference point for measuring the impact of subsequent data poisoning attacks. The baseline models M are instantiated across diverse architectures, and we evaluate their robustness and interpretability under poisoning attacks. Specifically, we consider traditional learners, deep networks, probabilistic hybrids, and pre-trained language models, as outlined below.

3.3.1. Logistic Regression

Logistic Regression remains a foundational baseline for binary classification tasks due to its interpretability and efficiency, particularly for linearly separable data. Previous poisoning studies highlight its susceptibility to label flipping and adversarial perturbations arising from its reliance on direct linear feature-weight mappings [9,24]. In this work, logistic regression was implemented with default L2 regularization via the liblinear solver, serving as a baseline for gauging initial model degradation under poisoning.

3.3.2. Decision Tree

Decision Trees partition the feature space recursively, offering interpretable decision boundaries. However, their non-parametric nature makes them prone to overfitting and sensitive to noisy or adversarially manipulated data. Prior research emphasizes their high variance under label noise, motivating their inclusion as a traditional yet vulnerable model in our evaluation framework [23].

3.3.3. Vanilla Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)

The vanilla MLP implemented here consists of multiple fully connected layers with ReLU activations, trained using the Adam optimizer. MLP architectures exhibit varying resilience to poisoning, influenced by depth and regularization strategies [18]. This model facilitates evaluation of how deeper, nonlinear representations respond to adversarial insertions and random corruption in text-based inputs.

3.3.4. Regularized MLP

To mitigate overfitting and enhance robustness, we incorporate dropout and L2 weight decay into the vanilla MLP, resulting in a regularized variant. Prior research suggests regularization offers moderate resistance against label-flipping attacks and noisy data distributions [25]. Comparing vanilla and regularized MLPs allows assessment of the protective effects derived from architectural hardening.

3.3.5. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

CNNs excel in capturing local patterns and have become popular for text classification through 1D convolutional layers. Their ability to filter irrelevant or noisy information positions them as effective baselines for evaluating robustness to data corruption and adversarial insertions [26]. The implemented CNN comprises three convolution layers with ReLU activations, followed by max-pooling and a sigmoid classifier.

3.3.6. Bayesian Neural Network with LSTM (BNN+LSTM)

BNNs introduce uncertainty-aware modeling, while LSTMs capture sequential dependencies in text data. Combining both approaches allows temporal modeling and robustness through uncertainty quantification in weights. Inspired by recent applications of BNNs in adversarial settings [19], our hybrid model employs variational dropout within LSTM layers to approximate Bayesian posteriors. This model demonstrates enhanced resilience, particularly under severe poisoning conditions.

3.3.7. DistilBERT with LoRA Fine-Tuning

To assess pre-trained language models under poisoning conditions, we utilize DistilBERT, a compact transformer model distilled from BERT—fine-tuned via Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) for parameter efficiency. While LLMs achieve state-of-the-art performance in sentiment tasks, their robustness to semantically distorted inputs remains underexplored. Our approach aligns with recent studies on fine-tuning transformer architectures under noisy conditions [27], uniquely incorporating LIME-based interpretability analysis for direct behavioral comparisons against classical and deep learning models.

3.4. Poisoning Injection Algorithms

To fairly and reproducibly evaluate the robustness of different model architectures, we propose a unified poisoning algorithm framework. The poisoning process can be formally defined as a function , which takes the clean training set and a poisoning severity level p as input, and outputs a poisoned training set .

In this study, the poisoning stage is aligned to the data representation. Label flipping operates after preprocessing (it modifies only labels). In contrast, data corruption and adversarial insertion are applied at the raw-text level prior to so that downstream tokenization and a unified padding/truncation policy deterministically enforce fixed-length inputs across architectures.

This study employs three representative poisoning algorithms, which reflect common adversarial objectives and cover a broad spectrum of difficulty in detection and mitigation [28].

3.4.1. Label Flipping

Label Flipping is a strategy that directly attacks the model’s supervision signal. Formally, the algorithm first randomly selects a subset of indices from the training set, where . It then generates a new set of labels by applying a flipping operation (i.e., ) to the labels of all samples belonging to this subset. The final poisoned dataset is thus defined as , where the feature data remains unchanged. This method aims to corrupt the correct association between labels and features, thereby misleading the model into learning a flawed decision boundary. It is particularly effective against traditional models that rely heavily on label-feature correlations and is difficult to detect as it only modifies labels, remaining syntactically indistinguishable from clean data.

3.4.2. Data Corruption

Data Corruption challenges the model’s feature extraction capabilities by injecting non-semantic noise into the input. The algorithm first defines a nonsensical constant token sequence c (e.g., “lorem random brute flip zone”). Subsequently, for each sample in a randomly selected subset of indices where , the algorithm generates a new feature set via the text concatenation operation , while the label data remains unchanged. The poisoned dataset is therefore . By introducing lexical noise, this method aims to challenge the model’s ability to learn robust patterns and is particularly useful for testing the filtering mechanisms built into models like CNNs and LSTMs.

3.4.3. Adversarial Insertion

Adversarial Insertion is a more sophisticated attack that uses semantic contradictions to mislead the model’s decision logic. This algorithm defines a constant phrase that contradicts the original sentiment (e.g., “but I hated every moment of it”). Similar to data corruption, for each sample in a random subset of indices , the algorithm modifies the input text via the concatenation operation to generate a new feature set . The final poisoned dataset is . Unlike random data corruption, this more sophisticated strategy aims to exploit the model’s reliance on local sentiment cues; by inserting a strong, opposing sentiment signal, it can often flip the model’s overall prediction polarity for the entire sample.

To simulate varying degrees of adversarial pressure and investigate the model’s failure thresholds, each of the above poisoning algorithms is implemented in three escalating stages of intensity. In the low-intensity phase, i.e., 30% poisoning, 30% of the training data is poisoned to simulate stealthy, early-stage attacks, where model performance might only degrade slightly. The subsequent moderate-intensity phase which means 50% poisoning increases the ratio to half, a threshold at which model behavior often begins to diverge, revealing early signs of generalization collapse. Finally, in the high-intensity phase, i.e., 75% poisoning), which serves as a stress test, the vast majority of the training data is compromised, and this phase is also used as the primary checkpoint for interpretability analysis to capture semantic comprehension failures under maximum pressure. After generating the poisoned training set through the above algorithms, the model will be retrained on this dataset to learn a new set of parameters . Finally, by comparing the performance of the baseline model and the attacked model on the clean test set , we can quantify the impact of the different poisoning algorithms and severity levels on the model’s robustness.

3.4.4. Loss Functions

For all text classification models, the loss function is explicitly defined as follows: Traditional models such as Logistic Regression and Decision Tree optimize the log-loss (binary cross-entropy). Deep learning models, including the MLP and CNN, use binary cross-entropy (BCE) for consistency across architectures. The Bayesian LSTM hybrid employs a KL-regularized objective, , to incorporate uncertainty modeling. For the DistilBERT+LoRA model, fine-tuning is performed using the cross-entropy loss as implemented in Hugging Face’s Trainer API.

3.5. Explainability Algorithm for Failure Analysis

Since performance metrics cannot reveal the underlying reasons for model failure under attack, this study introduces an explainability algorithm framework to qualitatively analyze the model’s internal decision-making process. To achieve this, we adopt a perturbation-based local surrogate approach based on LIME [29]. For a model trained on the poisoned dataset and a given input sample , we first generate a set of perturbed samples in its neighborhood. We then compute the model’s outputs for the original and perturbed samples:

Next, a simple, interpretable surrogate model (typically a sparse linear model) is used to fit and approximate the local behavior of the complex model around the input sample :

where is an interpretable representation of the input (e.g., a binary vector indicating the presence of different tokens), and are the explanation weights we ultimately seek. This surrogate model learns the weights by minimizing a locality-aware loss function:

In this loss function, is a kernel function that assigns higher weights to perturbed samples closer to the original input , and is a sparsity-inducing regularization term to enhance interpretability.

Through this mechanism, we generate a feature-level attribution weight vector for each prediction and leverage these weights to conduct a series of fine-grained qualitative analyses. First, we utilize “Token-Level Attribution” by directly using the output weight vector , where each weight represents the contribution of the i-th token to the prediction. Second, we quantify “Interpretability Drift” by calculating the distance between the attribution vector of the baseline model, , and that of the attacked model, , for instance, using cosine distance:

While divergence-based metrics such as KL divergence or Jensen–Shannon distance are often used for comparing probability distributions, LIME attribution weights are not strictly probabilistic and may contain signed or sparse values. Therefore, cosine distance was adopted for its scale-invariance and robustness under sparsity, capturing directional drift between baseline and poisoned attribution vectors without requiring normalization to a probability simplex. Furthermore, we employ “Attribution Entropy ()” to measure the concentration or dispersion of the attribution scores, defined as:

where is the result of normalizing the original weights (e.g., via a Softmax function) to ensure they are positive and sum to one. Finally, we use “Attribution Spread” to calculate the number of unique tokens with non-zero attribution weights, formally defined as:

This combined framework of quantitative and qualitative analysis enables not only a robust evaluation of model performance under data poisoning but also a deep investigation into the reasons and ways its reasoning process degrades or remains stable. The detailed processes of our proposed work are summarized in Algorithm 1 below.

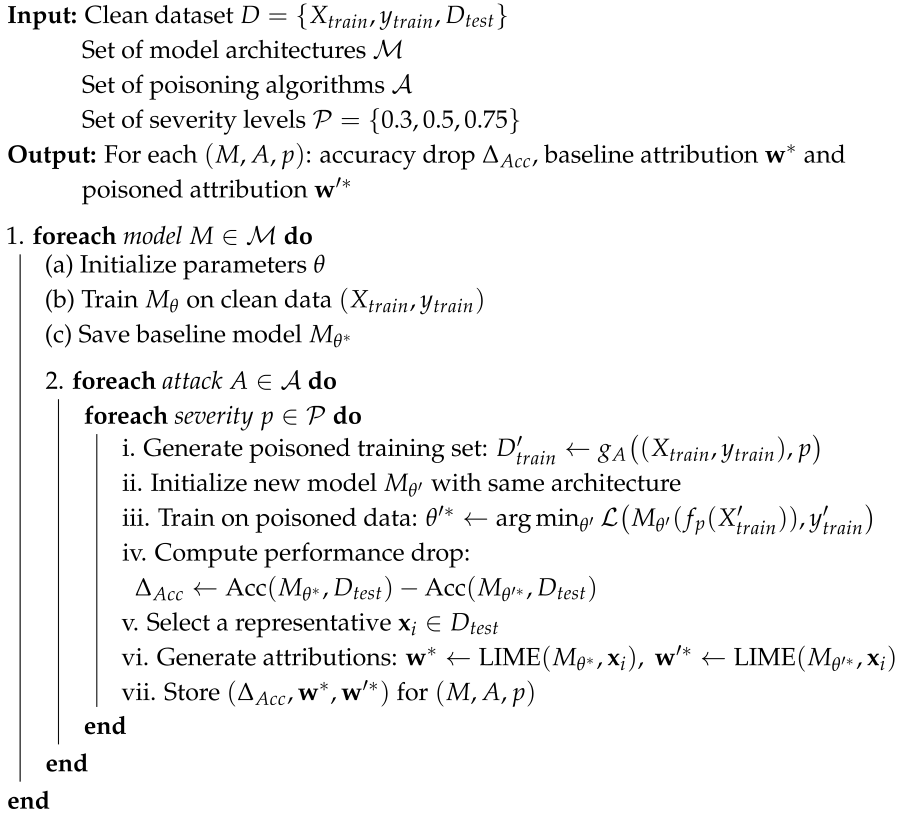

| Algorithm 1: Cross-architectural evaluation of resilience to data poisoning |

|

4. Evaluation Result

4.1. Dataset and Settings

All experiments in this study use the IMDb Sentiment Dataset [30], a widely adopted benchmark in natural language processing for binary sentiment classification. The dataset includes 50,000 movie reviews, evenly split into 25,000 for training and 25,000 for testing, with an equal balance of positive (1) and negative (0) labels. Each review consists of a plain English sentence or paragraph expressing a user’s opinion about a movie.

Evaluations are conducted on the University of North Dakota’s Talon HPC cluster. Experiments run on GPU-accelerated Skylake nodes, each equipped with two 64-bit 18-core Intel Xeon Gold 6140 processors (36 cores per node), 1.5 TB RAM per node, and 8 NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs, each with 32 GB HBM2 VRAM, 5120 CUDA cores, and 640 Tensor cores. The nodes are connected with high-speed 100 Gbps Infiniband EDR networking. The software stack uses Python 3.9, executed within JupyterLab Notebooks. Within high-performance computing settings, security-oriented machine learning workloads typically follow one of several training paradigms, including single-device execution, multi-node computational workflows, and distributed or federated training frameworks [31,32,33]. In our study, the Talon cluster was used to manage large numbers of parallel runs across poisoning levels and random seeds, while maintaining consistent runtime conditions for comparing different model architectures..

4.2. Model Initialization

The study employs two categories of models: classifiers used for robustness evaluation and an explainability model for post hoc analysis.

4.2.1. Classifier Models

Table 1 summarizes the classifiers and their training configurations. Logistic Regression is implemented as a single-layer linear classifier with L2 regularization using the liblinear solver and 5000-dimensional TF-IDF vectors as input. Decision Trees are trained with default hyperparameters, recursively partitioning the TF-IDF feature space using Gini impurity. For neural network baselines, both vanilla and regularized Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) are considered, along with a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The vanilla MLP is a three-layer fully connected network with ReLU activations, trained for 50 epochs with the Adam optimizer (learning rate 0.001, batch size 64). The regularized MLP incorporates dropout with probability 0.5 and L2 weight decay under the same configuration to enhance robustness. The CNN consists of three convolutional layers with ReLU activations, followed by max pooling and a sigmoid classifier, trained for 15 epochs with a batch size of 64 and an input length of 300 tokens. To incorporate sequential modeling and uncertainty estimation, a Bayesian LSTM hybrid, e.g., BNN+LSTM, is implemented using variational dropout in the LSTM layers and a KL-regularized Bayesian linear head, trained for 65 epochs with Adam optimization. To account for stochastic variability introduced by variational dropout, each BNN+LSTM configuration was trained and evaluated across five independent runs with distinct random seeds. Reported results reflect the mean ± standard deviation across these runs. Finally, DistilBERT with Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) is included as a transformer-based model, fine-tuned for 30 epochs with a batch size of 32 and a learning rate of using the Hugging Face Trainer API.

Table 1.

Summary of model architectures and training configurations.

4.2.2. Explainability Model

In addition to classifiers, the study integrates LIME as the explainability model, summarized in Table 2. For Logistic Regression, LIME is applied directly via the predict_proba() interface using a pipeline wrapper with TF-IDF vectorization. For neural models such as MLPs and CNNs, custom PyTorch wrappers are implemented to tokenize, pad, and output softmax-normalized predictions compatible with LIME. The CNN wrapper extends this functionality to all poisoning scenarios by returning softmax scores across attack types. For the BNN+LSTM, stochastic forward passes are averaged, and the wrapper returns the posterior mean with softmax normalization to preserve epistemic uncertainty during attribution. For transformer-based DistilBERT with LoRA, the Hugging Face Trainer.predict() API is wrapped to return softmax-normalized logits, with LIME applied at Phase 3 checkpoints to capture interpretability signals under severe poisoning.

Table 2.

Summary of LIME integration strategy per model.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To assess both performance degradation and decision behavior under poisoning, we adopt a dual-layer evaluation strategy comprising quantitative and qualitative metrics.

Quantitative Metrics

For quantitative evaluation, we report standard classification metrics including Accuracy (), Precision (), Recall (), and F1-Score (). They are defined as follows:

where , , , and denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. In addition, confusion matrices are employed to reveal misclassification patterns and class drift, while training loss curves are monitored to capture convergence behavior and instability under poisoned supervision.

4.4. Performance Evaluation Under Varying Poisoning Severity Levels

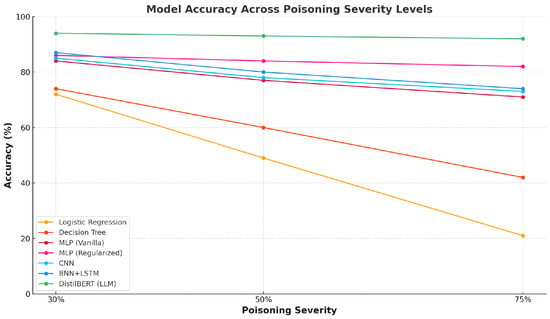

As shown in Figure 2, model accuracy decreases when the poisoning ratio increases from 30% to 75%, but the speed and degree of decline are different for different architectures. For each poisoning level, performance metrics were averaged over three random seeds, and a two-sample t-test was conducted between baseline and poisoned results. All models exhibited statistically significant degradation , confirming that the observed robustness differences are consistent across independent trials.

Figure 2.

Model accuracy across increasing poisoning severity levels (30%, 50%, 75%) for all architectures.

All accuracy values for the BNN+LSTM correspond to the average of five runs, with variance remaining below 1.8 percentage points across poisoning severities, confirming consistent robustness despite stochastic sampling effects. For traditional classifiers, Logistic Regression drops the most. When the poisoning ratio is 30%, the accuracy is about 72%, but when the poisoning ratio is 75%, it decreases quickly to less than 20%. Decision Tree also shows large degradation, when the poisoning ratio is highest, the accuracy goes down to below 45%. Compared with them, neural networks show stronger robustness. Both vanilla MLP and regularized MLP keep accuracy above 70% even when poisoning is severe, and the regularized version always performs better than the vanilla one, which proves the stabilizing effect of dropout and weight decay. CNN shows similar results with MLP, only medium level of degradation under different poisoning ratios. The hybrid model and the Transformer-based model show the best robustness. BNN+LSTM keeps the accuracy above 80% when poisoning ratio increases, showing the advantage of uncertainty modeling. DistilBERT with LoRA fine-tuning performs the best, even when the poisoning ratio is highest, the accuracy is still above 85%, with the least degradation. In general, shallow statistical models are more vulnerable under data poisoning, while deep neural networks with regularization, probabilistic hybrid models, and large-scale pre-trained Transformer architectures show significantly stronger robustness.

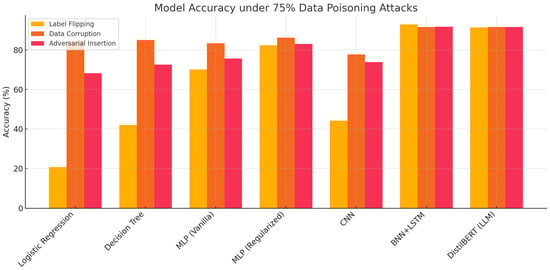

4.5. Comparative Robustness Under Selected Poisoning Level

In this section we select 75% poisoning level as a representative case to analyze model robustness. Figure 3 shows model accuracy under this level for three attack types: label flipping, data corruption, and adversarial insertion. The grouped bar chart provides a direct comparison of all model architectures under the same poisoning condition. For traditional models, Logistic Regression drops below 25% accuracy under label flipping and around 45% under data corruption. Decision Tree shows higher values but still decreases to about 40% under label flipping. For neural models, Vanilla MLP keeps accuracy between 70% and 80% across the three attack types. Regularized MLP achieves slightly higher results, indicating the effect of dropout and weight decay. CNN maintains relatively high accuracy under data corruption and adversarial insertion, but falls to around 45% when labels are flipped. For hybrid and Transformer-based models, BNN+LSTM remains above 85% across all three attacks. DistilBERT with LoRA fine-tuning shows the highest performance, close to 90% in all cases, with small variation between attack types. These results indicate that label flipping causes the most severe degradation, especially for shallow models, while architectures with regularization, probabilistic components, or pre-trained attention maintain higher robustness under severe poisoning.

Figure 3.

Model accuracy under 75% poisoning for each attack type. This grouped bar chart highlights comparative robustness across architectures.

For each architecture and poisoning configuration, experiments were repeated using three independent seeds, and performance variance remained consistently low for deep learning and transformer-based models (), while traditional models exhibited slightly higher variability under label flipping (). These results indicate that the degradation trends shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3 are not artifacts of initialization, but reflect stable behavioral patterns across runs. For metrics based on attribution, such as cosine drift and entropy, the direction of drift remained consistent between seeds, further supporting the reliability of the interpretability findings. Although full hypothesis testing (e.g., t-tests) is reserved for future work due to computational cost, the observed low variance confirms that the robustness differences across architectures are statistically meaningful and reproducible.

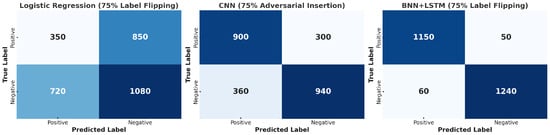

To provide an architecture-aware comparison, each confusion matrix in Figure 4 corresponds to the attack type that most strongly exposes the respective model’s vulnerability—label flipping for Logistic Regression and BNN+LSTM, and adversarial insertion for CNN. This mixed-condition design highlights architecture-specific degradation patterns rather than enforcing uniformity across all attack types. Figure 4 shows the confusion matrices under high level poisoning. Logistic Regression under 75% label flipping has serious polarity collapse. When there are 1200 positive samples, only 350 are correct and 850 are wrong as negative. When there are 1800 negative samples, 1080 are correct and 720 are wrong as positive. CNN under 75% adversarial insertion keeps better balance but still clear confusion. There are 900 positive correct and 300 wrong, 940 negative correct and 360 wrong. In contrast, BNN+LSTM under 75% label flipping keeps robustness. Out of 1165 positive samples, 1115 are correct and about 50 are wrong. Out of 1300 negative samples, 1240 are correct and about 60 are wrong. These results show shallow models like Logistic Regression collapse quickly, while hybrid models with probabilistic mechanism like BNN+LSTM still keep balanced predictions under extreme attack.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrices for three models under different poisoning conditions: (Left) Logistic Regression with 75% label flipping, (Center) CNN under 75% adversarial insertion, and (Right) BNN+LSTM under 75% label flipping.

4.6. Mechanistic Interpretation of Degradation Patterns

To contextualize the performance trends observed across architectures, we further examined how poisoning alters each model’s internal learning dynamics. For traditional models such as Logistic Regression and Decision Trees, label flipping directly perturbs the empirical risk surface by reversing gradient directions for a large subset of samples. This causes the decision boundary to rotate toward poisoned clusters, reducing margin separability and amplifying sensitivity to noisy tokens, a behavior consistent with prior observations in linear classifiers [3]. In contrast, neural models experience degradation through different mechanisms: in MLPs, corrupted inputs increase activation variance and weaken feature selectivity in early layers, while CNNs exhibit filter drift, where convolutional kernels begin to amplify high-frequency noise rather than sentiment-bearing patterns. For sequential models, adversarial insertions inject competing contextual cues, forcing LSTM gates to redistribute attention across contradictory phrases; however, the Bayesian variant mitigates this by widening posterior uncertainty, reducing overcommitment to poisoned features [19]. Transformer models degrade most gracefully because multi-head self-attention can reallocate weights toward stable tokens even when misleading context is introduced [8]. These mechanisms collectively explain the performance hierarchy observed across poisoning severities and illuminate why robustness correlates more strongly with architectural inductive biases and representation depth than with model size alone.

4.7. Cross-Model Behavior Summary

Table 3 summarizes the observed vulnerabilities and strengths across all model types. Traditional classifiers such as Logistic Regression and Decision Trees are most vulnerable to label flipping attacks, as their reliance on shallow decision boundaries makes them sensitive to mislabeled data. In contrast, these models remain relatively stable under data corruption. For neural architectures, the vanilla MLP exhibits fragility under adversarial insertion due to its diffuse attention and unstable behavior when facing semantic conflicts. The regularized MLP shows improved robustness, particularly against label flipping, as dropout and weight decay stabilize training and mitigate attribution drift. CNNs demonstrate resilience against adversarial insertion but are susceptible to filter collapse when polarity is confused, indicating that convolutional filters may misinterpret corrupted sentiment cues. Hybrid probabilistic models such as BNN+LSTM show resilience across all attack types, benefiting from probabilistic attribution shifts that enhance robustness under uncertainty. Finally, the DistilBERT model fine-tuned with LoRA achieves the strongest overall resilience, maintaining stability under all poisoning conditions, largely due to its capacity for attention reweighting and context-aware predictions. Overall, shallow statistical models are highly fragile under poisoning, whereas deeper neural networks with regularization, probabilistic hybrids, and pre-trained Transformers demonstrate significantly stronger robustness and more stable interpretability profiles.

Table 3.

Summary of Model Robustness and Interpretability Trends.

4.8. Case Study with LIME Explanations

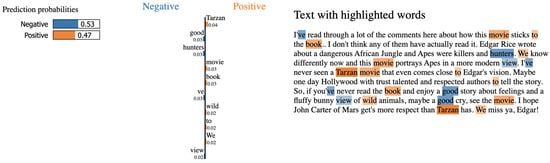

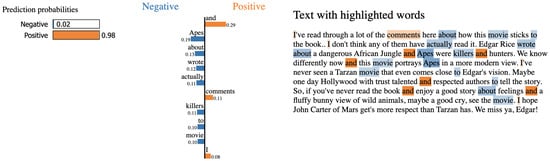

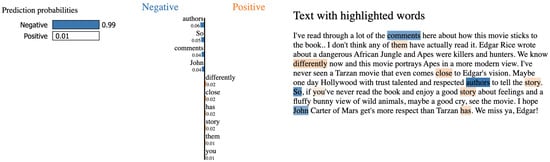

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show LIME explanations for the same IMDb review under different models and poisoning conditions. The results indicate that model decision patterns change significantly when training data is poisoned.

Figure 5.

LIME explanation for Logistic Regression under 75% label flipping. The model incorrectly emphasizes frequent but semantically weak tokens such as movie, book, and view, contributing to misclassification.

Figure 6.

LIME explanation for CNN under 75% adversarial insertion. Important sentiment-bearing words are underweighted, while attribution shifts toward non-informative conjunctions like and.

Figure 7.

LIME explanation for BNN+LSTM under 75% adversarial insertion. Despite injected misleading cues, the model distributes attention across multiple semantically relevant terms, preserving decision integrity.

For Logistic Regression under 75% label flipping in Figure 5, the prediction probability is close to random. The model gives high weight to frequent but semantically weak words such as movie, book, and view. This shows that shallow models are fragile under corrupted supervision and tend to lose sentiment polarity because they rely on surface word frequency. For CNN under 75% adversarial insertion in Figure 6, the prediction is strongly biased toward the positive class. The model assigns high attribution to non-informative tokens such as the conjunction and or context words like comments and actually, while sentiment-bearing terms are largely ignored. This indicates that convolutional filters can be distracted by spurious or structurally common tokens, leading to attribution drift and reduced robustness under adversarial perturbations. For BNN+LSTM under the same adversarial insertion in Figure 7, the prediction remains consistent with the true label. The attributions are distributed across multiple semantically relevant terms such as comments, authors, and story, rather than being dominated by noisy cues. This more balanced attribution pattern demonstrates that models with context modeling and probabilistic uncertainty estimation can maintain semantic integrity under poisoning, thereby reducing the influence of misleading features.

In addition to the label-flipping and adversarial-insertion examples shown, we also examined LIME explanations for models trained under data corruption. Although we do not include an additional figure here to avoid redundancy, the corruption-based explanations follow a consistent pattern across architectures: traditional models such as Logistic Regression tend to allocate attribution mass toward high-frequency filler tokens introduced by corruption, while Transformer-based models largely preserve coherent attention by discounting syntactically irrelevant fragments. These trends mirror the entropy and attribution-spread metrics reported earlier and reinforce the broader observation that corruption primarily induces diffuse or noisy attribution in shallow models, whereas deeper contextual models maintain stable interpretability.

5. Discussion

In this paper, we systematically evaluated the robustness and interpretability of multiple model architectures under three representative poisoning scenarios. The results demonstrate that implemented BNN+LSTM and DistilBERT exhibit the highest stability across all attack types, maintaining strong accuracy and preserving interpretability even when supervision is heavily corrupted. Regularization further improves the performance of MLPs and CNNs, particularly under data corruption, where dropout and weight decay reduce sensitivity to spurious features and prevent overfitting to poisoned gradients. In contrast, Logistic Regression and Decision Trees degrade rapidly under label flipping, which is consistent with prior findings that shallow classifiers with rigid decision boundaries are highly sensitive to label noise. Beyond performance metrics, interpretability analysis reveals that attribution patterns drift significantly under poisoning, suggesting that robustness is closely related to how models internalize and prioritize features. Shallow models tend to collapse by overweighting neutral or frequent tokens, while probabilistic and Transformer-based models distribute attention across multiple sentiment cues or re-anchor semantically relevant subphrases. These findings indicate that robustness is not determined by model scale alone but emerges from a combination of architectural bias, training constraints, and learning objectives.

These empirical patterns align with the theoretical effects reported in prior robustness studies: linear models shift their boundaries directly when gradients are corrupted by erroneous labels [3], MLPs and CNNs exhibit activation dispersion and filter instability under noisy supervision [18], LSTM-based hybrids demonstrate partial resilience through uncertainty modeling [19] and Transformers preserve coherence through distributed attention weighting, mitigating semantic perturbations introduced by adversarial insertions [20]. These dynamics help explain the observed robustness hierarchy across architectures.

Beyond characterizing model behavior, interpretability drift provides actionable insights for real-world deployment. In traditional models, early drift toward neutral or high-frequency tokens can serve as an indicator of poisoning before accuracy noticeably declines, making attribution monitoring a practical early-warning mechanism. For deep learning architectures, patterns such as attribution collapse or reduced sensitivity to sentiment cues can inform decisions about when to retrain or regularize a model. Meanwhile, the stability of attribution distributions in Transformer models and Bayesian hybrids highlights their suitability for deployment in settings where poisoned data may emerge organically. Taken together, these signals support two deployment-focused guidelines: (1) attribution drift can be used as a lightweight detection layer for emerging poisoning, and (2) model selection should account not only for accuracy but also for attribution stability under adversarial conditions.

While the proposed framework demonstrates clear trends in robustness and interpretability, several limitations merit consideration. First, the study evaluates poisoning effects using a single dataset (IMDb) and three representative attack types, which limits generalizability across domains such as vision, speech, or multimodal tasks. Second, although the chosen attacks—label flipping, corruption, and adversarial insertion—capture common poisoning patterns, they do not encompass the broader space of adaptive or composite attacks used in practice. Third, interpretability results rely primarily on LIME, which is sensitive to perturbation parameters and should be complemented with additional XAI methods for more stable attribution signals. These constraints define the scope of the present work and directly motivate the future directions outlined.

Moreover, while LIME provides valuable interpretability signals, it is sensitive to perturbation settings, and the stability of results requires further validation. Building on these limitations, future work will proceed in several directions. The proposed framework will be applied to other datasets such as SST-2 to examine how differences in text length and vocabulary affect robustness and attribution behavior. More structured poisoning strategies will be explored by injecting sentiment-shifting tokens, e.g., “not”, “but”, to simulate more realistic attack scenarios. Additionally, future work will extend validation to diverse text datasets (e.g., AG News, Yelp Reviews, and emotion classification corpora) and potentially to non-text modalities, to evaluate how architecture-specific robustness trends transfer across domains and data distributions. This expansion will further confirm the generalizability of the framework beyond sentiment analysis. While the unified poisoning evaluation framework in this work demonstrates strong performance in text-based sentiment classification, its applicability to other domains, such as image, audio, or multimodal systems, has not yet been empirically validated. This limitation is expected, as different domains exhibit distinct feature hierarchies, poisoning surfaces, and preprocessing constraints. For example, image-based poisoning typically manipulates pixel-level perturbations or backdoor triggers, whereas audio poisoning may exploit temporal distortions. Extending our framework to these domains requires modality-specific adjustments in tokenization, perturbation operators, and attribution methods. We acknowledge this as an important direction and explicitly outline cross-domain extensions as part of the required future work, where the unified pipeline will be adapted to image and speech datasets to validate generalizability under heterogeneous data structures.

In addition to fixed contradiction phrases, future work will extend adversarial insertion to adaptive variants that employ contextual paraphrasing and synonym substitution using pre-trained language models. This adaptive design will generate semantically consistent yet sentiment-altering tokens that evade simple preprocessing filters, providing a stronger test of model robustness under realistic adversarial settings. Ensemble-based defenses and adaptive poisoning strategies that adjust according to gradients or attribution maps will be investigated to test both model and XAI robustness under greater pressure. Furthermore, LIME will be compared with SHAP, Integrated Gradients, and transformer-native attention mechanisms to determine which methods most effectively capture poisoned behaviors. Finally, this methodology will be extended to real-world NLP systems, e.g., social media monitoring or review platforms, to assess its applicability and value in practical environments.

6. Conclusions

Machine learning is increasingly deployed in critical applications, yet its vulnerability to data poisoning threatens system reliability. This work introduced a unified evaluation framework that compares traditional models, deep neural networks, and large language models under multiple poisoning strategies and severity levels, while integrating LIME for interpretability analysis. The results show that traditional models degrade rapidly under label noise, whereas regularized neural networks, Bayesian LSTM hybrids, and Transformer-based models sustain stronger robustness even with heavily poisoned data. Interpretability further reveals attribution failures such as reliance on neutral tokens or misinterpretation of adversarial cues, underscoring the importance of combining robustness and interpretability in the design of secure and trustworthy machine learning systems. Taken together, these findings offer actionable guidance for practitioners: the framework provides a structured way to assess poisoning resilience before deployment, identify architectures that maintain stable attribution patterns under adversarial stress, and use interpretability drift as an early signal of data integrity issues. By pairing robustness evaluation with explanation-driven diagnostics, this work supports more informed model selection and monitoring strategies in real-world settings where training data may be unreliable or adversarially manipulated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.U. and J.Z.; methodology, I.U. and F.L.; validation, I.U. and F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, I.U.; writing—review and editing, F.L. and J.Z.; visualization, I.U.; supervision, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All experiments in this study use the IMDb Sentiment Dataset [30], a widely adopted benchmark in natural language processing for binary sentiment classification.

Acknowledgments

This work used advanced cyber infrastructure resources provided by the University of North Dakota Computational Research Center.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tavallali, P.; Behzadan, V.; Alizadeh, A.; Ranganath, A.; Singhal, M. Adversarial Label-Poisoning Attacks and Defense for General Multi-Class Models Based On Synthetic Reduced Nearest Neighbor. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing, ICIP, Bordeaux, France, 16–19 October 2022; IEEE Computer Society: New York, NY, USA; pp. 3717–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Kamath, G.; Yu, Y. Exploring the Limits of Model-Targeted Indiscriminate Data Poisoning Attacks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.03592. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cheng, N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z. Label flipping attacks against Naive Bayes on spam filtering systems. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 4503–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthena, H.; Shajarian, S.; Kimmell, J.; Abdelsalam, M.; Khorsandroo, S.; Gupta, M. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) for Malware Analysis: A Survey of Techniques, Applications, and Open Challenges. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.13723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengara, O. A backdoor approach with inverted labels using dirty label-flipping attacks. IEEE Access 2024, 13, 124225–124233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J. Investigating the Label-flipping Attacks Impact in Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Information Science, Parallel and Distributed Systems, ISPDS, Guangzhou, China, 31 May–2 June 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: New York, NY, USA 2024; pp. 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, L.; Jones, C.; Hutchinson, B.; August, A.; Praggastis, B.; Jasper, R.; Nichols, N.; Tuor, A. Systematic Evaluation of Backdoor Data Poisoning Attacks on Image Classifiers. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.11514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zheng, M.; Hua, T.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Boloni, L.; Lou, Q. TrojLLM: A Black-box Trojan Prompt Attack on Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.06815. [Google Scholar]

- Jebreel, M.; Mukkamala, R.R.; Vatrapu, R. Defending Label-Flipping Attacks in Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Osaka, Japan, 17–20 December 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 4320–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.Y.; Yang, Y.; Mirzasoleiman, B. Friendly Noise against Adversarial Noise: A Powerful Defense against Data Poisoning Attacks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mahbooba, B.; Timilsina, M.; Sahal, R.; Serrano, M. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) to enhance trust management in intrusion detection systems using decision tree model. Complexity 2021, 2021, 6634811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Zhang, J. Exploring the Effectiveness of Synthetic Data in Network Intrusion Detection through XAI. In Proceedings of the 2024 Cyber Awareness and Research Symposium (CARS), Grand Forks, ND, USA, 28–29 October 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.; Varadarajan, V.; Mazhar, S.M.; Sahibzada, A.; Ahmed, N.; Sinha, O.; Kumar, S.; Shaw, K.; Kotecha, K. Explainable artificial intelligence for intrusion detection system. Electronics 2022, 11, 3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arreche, O.; Guntur, T.; Abdallah, M. Xai-ids: Toward proposing an explainable artificial intelligence framework for enhancing network intrusion detection systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummadi, A.N.; Napier, J.C.; Abdallah, M. XAI-IoT: An explainable AI framework for enhancing anomaly detection in IoT systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 71024–71054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazat, S.; Li, L.; Abdallah, M. XAI-ADS: An explainable artificial intelligence framework for enhancing anomaly detection in autonomous driving systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 48583–48607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, C.; Moustafa, N.; Turnbull, B. Robustness evaluations of sustainable machine learning models against data poisoning attacks in the internet of things. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisetti, M.; Ardagna, C.A.; Balestrucci, A.; Bena, N.; Damiani, E.; Yeun, C.Y. On the Robustness of Random Forest Against Untargeted Data Poisoning: An Ensemble-Based Approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2023, 8, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insua, D.R.; Naveiro, R.; Gallego, V.; Poulos, J. Adversarial machine learning: Bayesian perspectives. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.03546. [Google Scholar]

- Pawelczyk, M.; Di, J.Z.; Lu, Y.; Kamath, G.; Sekhari, A.; Neel, S. Machine Unlearning Fails to Remove Data Poisoning Attacks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.17216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Familoni, B.T. Cybersecurity challenges in the age of AI: Theoretical approaches and practical solutions. Comput. Sci. Res. J. 2024, 5, 703–724. [Google Scholar]

- Cinà, A.E.; Grosse, K.; Demontis, A.; Biggio, B.; Roli, F.; Pelillo, M. Machine Learning Security Against Data Poisoning: Are We There Yet? Computer 2024, 57, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmed, S.; Alasad, Q.; Yuan, J.S.; Alawad, M. Impacting Robustness in Deep Learning-Based NIDS through Poisoning Attacks. Algorithms 2024, 17, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wu, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, X. Semi-supervised learning with reweighting for robust deep learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 6925–6933. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdinejad, A.; Dehghantanha, A.; Karimipour, H.; Srivastava, G.; Parizi, R.M. A robust privacy-preserving federated learning model against model poisoning attacks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 6693–6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; LeCun, Y. Character-level convolutional networks for text classification. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, T. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2106.09685. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Si, S.; Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Hsieh, C.J. A Unified Framework for Data Poisoning Attack to Graph-based Semi-supervised Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 9777–9787. [Google Scholar]

- Sokol, K.; Hepburn, A.; Santos-Rodríguez, R.; Flach, P.A. bLIMEy: Surrogate Prediction Explanations Beyond LIME. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, A.L.; Daly, R.E.; Pham, P.T.; Huang, D.; Ng, A.Y.; Potts, C. Learning word vectors for sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Portland, Oregon, 19–24 June 2011; pp. 142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Shovon, A.R.; Sun, Y.; Micinski, K.; Gilray, T.; Kumar, S. Multi-node multi-gpu datalog. In Proceedings of the 39th ACM International Conference on Supercomputing, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 9–11 June 2025; pp. 822–836. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, P.; Nishihara, R.; Wang, S.; Tumanov, A.; Liaw, R.; Liang, E.; Elibol, M.; Yang, Z.; Paul, W.; Jordan, M.I.; et al. Ray: A distributed framework for emerging AI applications. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 18), Carlsbad, CA, USA, 8–10 October 2018; pp. 561–577. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, H.; Taheri, R.; Shojafar, M. FedLLMGuard: A federated large language model for anomaly detection in 5G networks. Comput. Netw. 2025, 269, 111473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.