Information-Driven Team Collaboration in RoboCup Rescue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. RoboCup Rescue Simulation Environment

- Coordinates: X and Y coordinates of the blockade centroid.

- Position: ID of the road entity containing the blockade.

- RepairCost: Total effort required to remove the blockade completely.

- Police Force agents (blue): Clear road blockades; clearing capacity per cycle is governed by the RepairRate property.

- Ambulance Team agents (white): Load injured civilians and transport them to a refuge center.

- Fire Brigade agents (red): Extinguish fires and rescue buried civilians.

4. TAEMS Modeling Language

- q_seq_sum(): quality of the parent task equals the sum of qualities from subtasks executed sequentially.

- q_exactly_one(): quality of the parent task equals the quality of exactly one successfully completed subtask.

5. Methodology

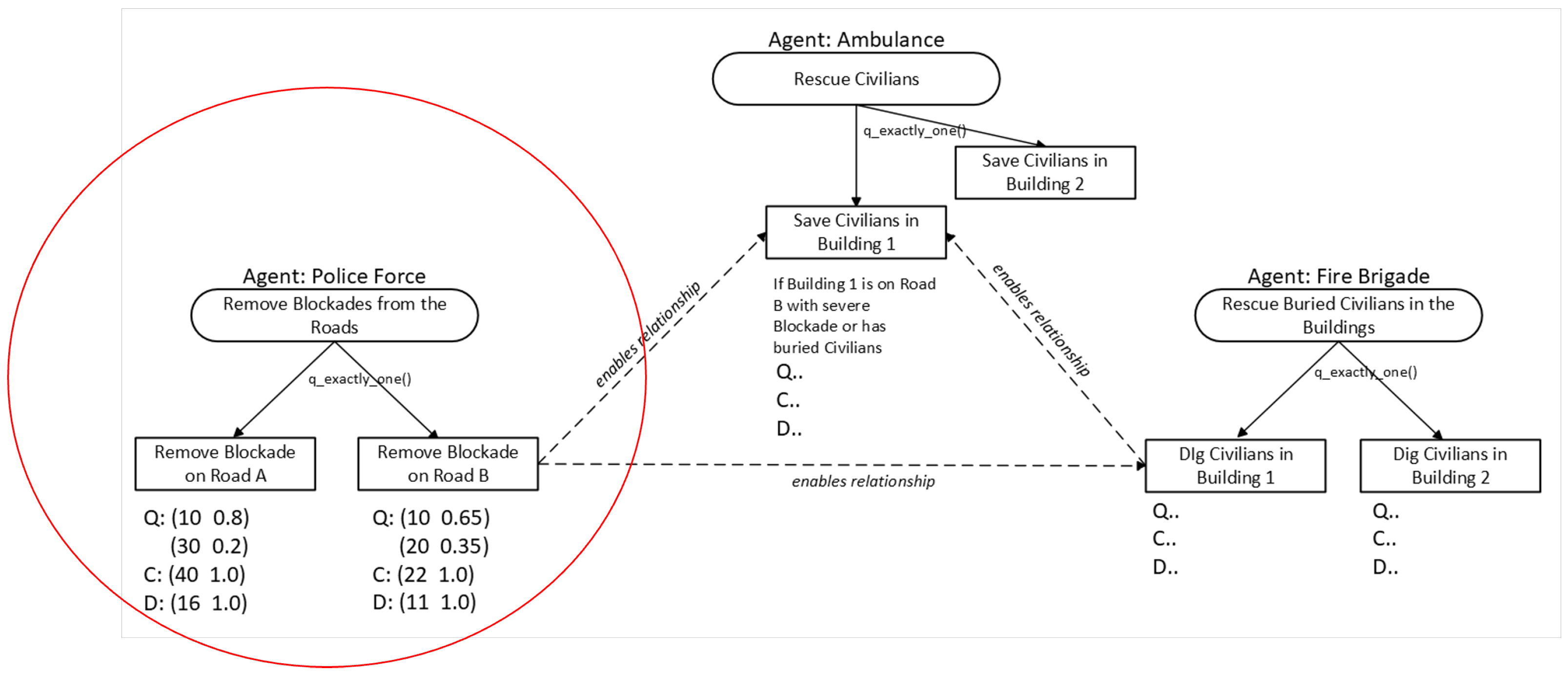

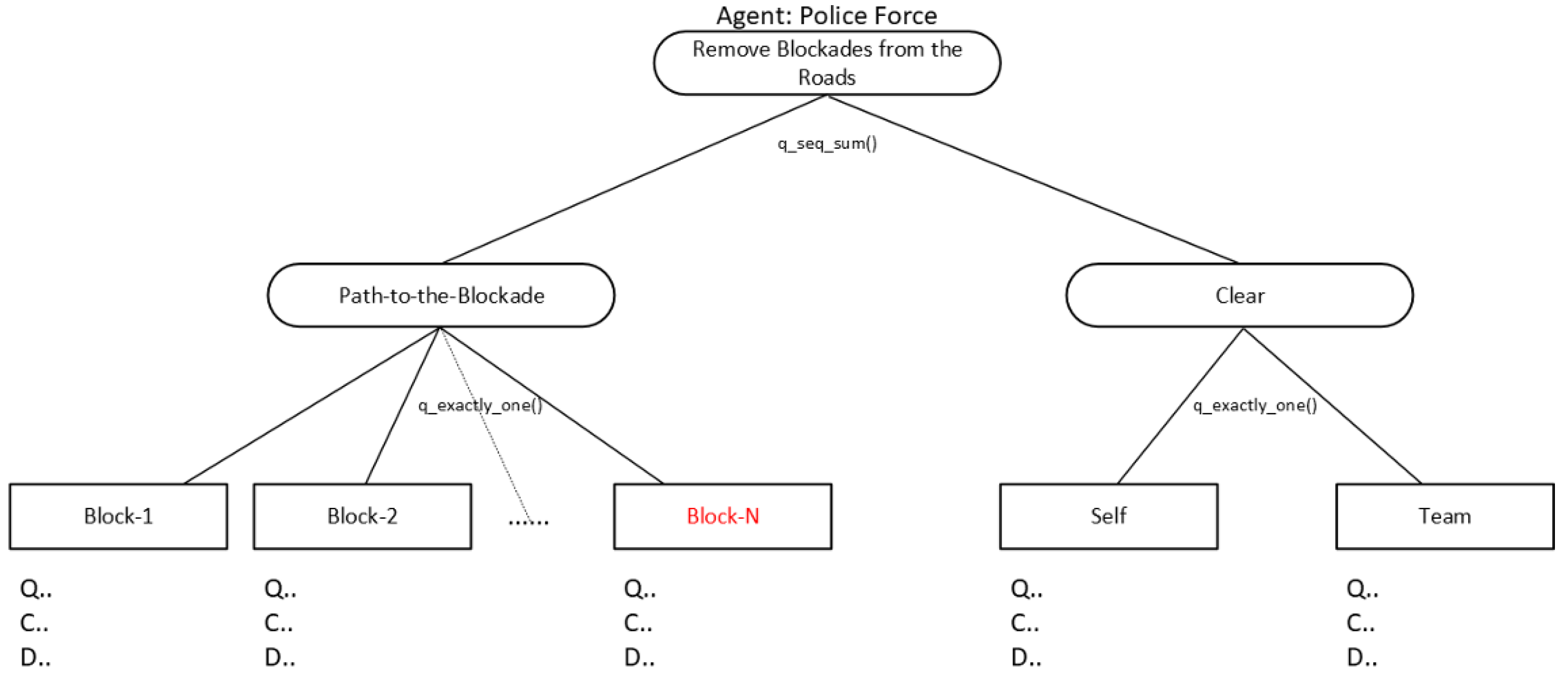

5.1. Police Force Agent Design

- Shared Communication Space: blockades explicitly prioritized by the team (Section 5.3).

- Heard Voice Messages: blockade announcements received within the 30 m voice range from other agents.

- Nearby Blockades: blockades located on the same road as the PF agent.

5.2. Task Scheduler for PF

- 1.

- Extract all candidate methods currently present in the template.

- 2.

- Fill in their QCD distributions based on real-time information.

- 3.

- Generate a set of alternative schedules S that respect the defined QAFs and intertask relationships (primarily enables).

- 4.

- Select the schedule with the highest goodness score according to the DTC criterion Formula (1).

5.3. Control Flows for Agent Action and Interaction

- Upon encountering an unburied (rescued) civilian, an AT agent transports the civilian directly to the nearest refuge.

- Upon encountering a buried civilian, an AT agent broadcasts the civilian entity via the voice channel.

- Upon receiving a voice message from an FB agent announcing a newly rescued civilian, the AT agent navigates to that location. If the path is clear, the civilian is transported to the refuge; otherwise, the obstructing blockade entity is broadcast.

6. Experiments and Results

6.1. Robustness Experiment

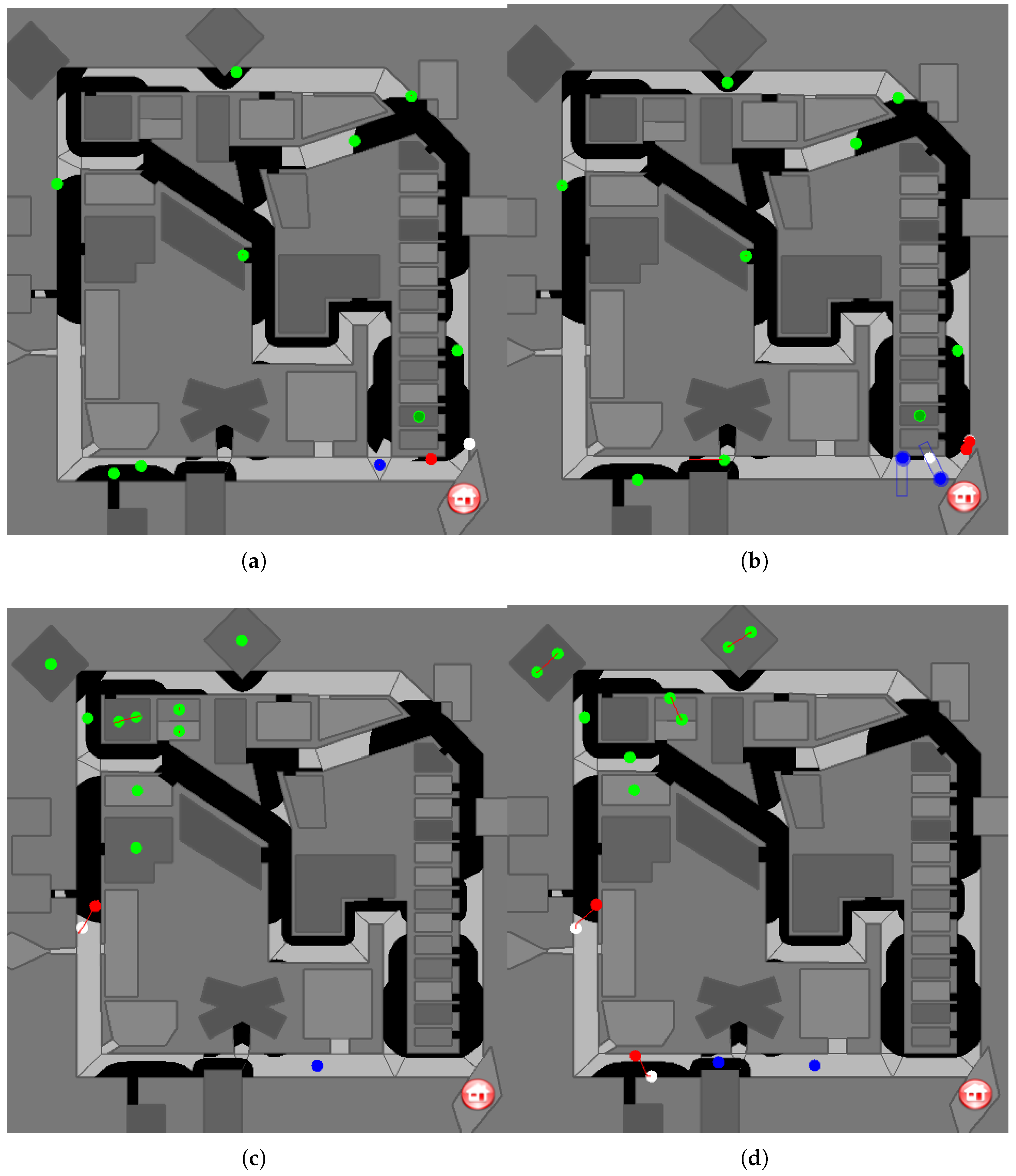

6.2. Score Comparison Experiment

- Configuration 1 (Figure 8a): Nine civilians scattered across the map, with one agent of each type (PF, AT, FB) placed nearby. This layout is relatively straightforward even for default agents.

- Configuration 2 (Figure 8b): Same civilian distribution as Configuration 1, but with two agents of each type. This setting tests coordination among multiple homogeneous agents of the same role.

- Configuration 3 (Figure 8c): Nine civilians clustered together, with one agent of each type positioned far apart. This configuration emphasizes long-range communication-driven coordination, particularly the ability of the distant PF agent to prioritize relevant blockades early.

- Configuration 4 (Figure 8d): Same civilian clustering as Configuration 3, but with two agents of each type. The increased travel distances cause civilians to accumulate more damage before rescue, raising overall difficulty.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saur, D.; Geihs, K. IMPERA: Integrated Mission Planning for Multi-Robot Systems. Robotics 2015, 4, 435–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjanna, S.; Dudek, G.; Hansen, J.; Pizarro, O.; Zykov, V. Informed Scientific Sampling in Large-scale Outdoor Environments. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 4–8 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R.R. Trial by fire [rescue robots]. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2004, 11, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, H.L.; Ito, N.; Jacoff, A.; Kleiner, A.; Pellenz, J.; Visser, A. Robocup rescue robot and simulation leagues. AI Mag. 2012, 34, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, J.K.; Ranga, V. Multi-robot coordination analysis, taxonomy, challenges and future scope. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2021, 102, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almadhoun, R.; Taha, T.; Seneviratne, L.; Zweiri, Y. A survey on multi-robot coverage path planning for model reconstruction and mapping. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Jouandeau, N.; Cherif, A.A. A survey and analysis of multi-robot coordination. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2013, 10, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, M.; Bai, Q. Dynamic task allocation for heterogeneous agents in disaster environments under time, space and communication constraints. Comput. J. 2015, 58, 1776–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RoboCup Rescue Simulation. Available online: https://rescuesim.robocup.org (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Horling, B.; Lesser, V.; Vincent, R.; Wagner, T.; Raja, A.; Zhang, S.; Decker, K.; Garvey, A. The TAEMS White Paper. 1999. Available online: http://mas.cs.umass.edu/paper/182 (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Degbor, D.; Bedi, A.; Zhang, S.; Chabot, E. Communication-Facilitated Coordination in Agent Team Rescue Mission. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering & Applied Computing (CSCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 July 2023; pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, B.; Fang, F. The Application of Adaptive Ant-colony A Hybrid Algorithm Based on Objective Evaluation Factor in RoboCup Rescue Simulation Dynamic Path Planning. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 631, p. 052028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Q.; Cao, X.; Yu, Y.; Xue, S.; Yang, J.; Wu, J.; Beheshti, A. A Multiagent-based Framework on RoboCup Simulation System for Enhancing Rescue Operation during Dynamic Disaster Environments. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume WWW’25, pp. 1180–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, K.; Maeda, R.; Uehara, H.; Fujisawa, J.; Matsunaga, I.; Suzuki, R.; Kato, K.; Shimada, Y.; Fujii, S.; Uchitane, T.; et al. Designing a Rescue Strategy Emphasizing Distributed Control in RoboCupRescue Simulation: AIT-Rescue: RoboCup 2024 Rescue Simulation League Champion. In Robot World Cup; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 436–447. [Google Scholar]

- Sedaghat, M.N.; Nejad, L.P.; Iravanian, S.; Rafiee, E. Task allocation for the police force agents in RoboCup Rescue simulation. In Robot Soccer World Cup; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4020, pp. 656–664. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol-Gonzalez, M.; Cerquides, J.; Farinelli, A.; Meseguer, P.; Rodríguez-Aguilar, J.A. Binary Max-Sum for Multi-Team Task Allocation in RoboCup Rescue. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, Paris, France, 5–9 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.R., Jr.; dos Santos, F.; Bazzan, A.L.C.; Epstein, D.; Waskow, S.J. RoboCup Rescue as multiagent task allocation among teams: Experiments with task interdependencies. J. Auton. Agents-Multi-Agent Syst. 2010, 20, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchurn, S.; Farinelli, A.; Macarthur, K.; Jennings, N. Decentralized Coordination in RoboCup Rescue. Comput. J. 2010, 53, 1447–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, D.S. Multi-Agent Systems for Search and Rescue Applications. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2021, 2, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xueke, Y.; Yu, Z.; Junren, L.; Kaiqiang, W. Multi-agent Task Coordination Method Based on RCRS. In 2021 International Conference on Autonomous Unmanned Systems (ICAUS 2021); Wu, M., Niu, Y., Gu, M., Cheng, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 2582–2593. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Duan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Lyu, C.; Chang, Y.C.; Lin, C.T.; Shen, Y. Multi-Agent Coordination across Diverse Applications: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.14743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybczak, M.; Popowniak, N.; Lazarowska, A. A Survey of Machine Learning Approaches for Mobile Robot Control. Robotics 2024, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ye, S.; Sun, C.; Zhang, A.; Deng, G.; Liao, T. Optimized Foothold Planning and Posture Searching for Energy-Efficient Quadruped Locomotion over Challenging Terrains. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CE: Kobe Earthquake. 2023. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/thisday/jan17/kobe-earthquake/ (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. Kobe Earthquake of 1995. 2022. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/event/Kobe-earthquake-of-1995 (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Kitano, H.; Tadokoro, S. RoboCup rescue: A grand challenge for multiagent and intelligent systems. AI Mag. 2001, 22, 39. [Google Scholar]

- RoboCup Rescue Simulation Server Team. RoboCup Rescue Simulation Server Manual. 2023. Available online: https://roborescue.github.io/rcrs-server/rcrs-server/rcrs-server-manual.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Decker, K.S.; Lesser, V.R. Quantitative modeling of complex environments. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Account. Financ. Managt. 1993, 2, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, Y.; Durfee, E.H. Designing tree-structured organizations for computational agents. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 1998, 4, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horling, B.; Lesser, V. A survey of multi-agent organizational paradigms. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2005, 19, 281–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Lesser, V.; Zilberstein, S. Analyzing Myopic Approaches for Multi-Agent Communication. Comput. Intell. 2003, 19, 179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Lesser, V. Reflections on the Nature of Multi-Agent Coordination and Its Implications for an Agent Architecture. Auton. Agents-Multi-Agent Syst. 2012, 26, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, V.; Decker, K.; Wagner, T.; Carver, N.; Garvey, A.; Horling, B.; Neiman, D.; Podorozhny, R.; Prasad, M.N.; Raja, A.; et al. Evolution of the GPGP/TAEMS Domain-Independent Coordination Framework. Auton. Agents-Multi-Agent Syst. 2004, 9, 87–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, K.; Lesser, V. Designing a family of coordination algorithms. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Multi-Agent Systems (ICMAS-95), San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–14 June 1995; pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, T.; Garvey, A.; Lesser, V. Criteria-directed task scheduling. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 1998, 19, 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Task Completion | Default PF | Modeled PF | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | AVG | CV | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | AVG | CV | |

| Contact with First Civilian | 273 | 272 | 273 | 272.7 | 0.2% | 202 | 202 | 203 | 202.3 | 0.3% |

| Contact with Fire Brigade | 319 | 318 | 319 | 318.7 | 0.2% | 221 | 220 | 221 | 220.7 | 0.3% |

| Contact with Ambulance | 340 | 341 | 342 | 341.0 | 0.3% | 259 | 258 | 259 | 258.7 | 0.2% |

| Rescued All Civilians | 341 | 341 | 342 | 341.3 | 0.2% | 337 | 337 | 337 | 337.0 | 0% |

| No. | Agent Distribution | Civilian Distribution | Humans | Scores (Out of 10) | Improvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default Agents | Modeled Agents | |||||

| 1 | Nearby | Scattered | 1PF/1AT/1FB/9civilians | 8.889 | 9.960 | 12.05% |

| 2 | Nearby | Scattered | 2PF/2AT/2FB/9civilians | 8.889 | 9.995 | 12.44% |

| 3 | Scattered | Nearby | 1PF/1AT/1FB/9civilians | 5.556 | 7.644 | 37.58% |

| 4 | Scattered | Nearby | 2PF/2AT/2FB/9civilians | 4.356 | 6.455 | 48.19% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bedi, A.; Zhang, S.; Chabot, E. Information-Driven Team Collaboration in RoboCup Rescue. Information 2026, 17, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010008

Bedi A, Zhang S, Chabot E. Information-Driven Team Collaboration in RoboCup Rescue. Information. 2026; 17(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleBedi, Abhijot, Shelley Zhang, and Eugene Chabot. 2026. "Information-Driven Team Collaboration in RoboCup Rescue" Information 17, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010008

APA StyleBedi, A., Zhang, S., & Chabot, E. (2026). Information-Driven Team Collaboration in RoboCup Rescue. Information, 17(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010008