Abstract

Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks represent a pervasive and critical threat to autonomous vehicles, jeopardizing their operational functionality and passenger safety. The ease with which these attacks can be launched contrasts sharply with the difficulty of their detection and mitigation, necessitating advanced defensive solutions. This study proposes a novel deep-learning framework for accurate DDoS detection within automotive networks. We implement and compare multiple artificial neural network architectures, including Convolutional Neural Networks, Recurrent Neural Networks, and Deep Neural Networks, enhanced with an active learning component to maximize data efficiency. The most performant model is subsequently deployed within a federated learning paradigm to facilitate collaborative, privacy-preserving training across distributed clients. The study is evaluated against three primary DDoS attack vectors: volumetric, state-exhaustion, and amplification. Experimental results on the CIC-DDoS2019 benchmark dataset demonstrate the efficacy of our approach, achieving a 99.98% accuracy in attack classification. This indicates a promising solution for real-time DDoS detection in the safety-critical context of autonomous driving.

1. Introduction

The advent of Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) promises a paradigm shift in transportation, heralding significant advancements in road safety, traffic efficiency, and overall mobility [1,2]. These complex cyber-physical systems operate by continuously perceiving their environment through a suite of sophisticated sensors (LIDAR, radar, cameras) and making real-time navigational decisions based on the fusion of this data [3]. This operational model, however, intrinsically expands the vehicle’s attack surface, transforming it from a mechanical entity into a network of interconnected, data-dependent computers on wheels [4]. While the benefits are substantial, this reliance on continuous data exchange and software-driven control introduces critical vulnerabilities. The security of these systems is no longer a secondary feature but a foundational prerequisite for their safe deployment. This section delineates the escalating threat landscape, with a specific focus on Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks, and establishes the urgent need for the advanced, AI-driven detection framework proposed in this work. The digital ecosystem is currently witnessing an unprecedented surge in the scale, frequency, and sophistication of DDoS attacks. Recent threat intelligence reports indicate a 358% year-over-year increase [5] in blocked DDoS attacks, with millions recorded per quarter. Furthermore, the threat has evolved beyond mere volume. The rise in hyper-volumetric attacks, some exceeding 6.5 Terabits per second and high packet-rate attacks, demonstrates an adversary’s capability to overwhelm conventional cloud and network defenses with ease [6]. Simultaneously, DDoS attacks are not only becoming more common but also more powerful, with hyper-volumetric attacks exceeding 1 Tbps growing by nearly 1900% in just one quarter of 2024 [7]. The emergence of massive botnets, with one comprising over 13,000 IoT devices to launch a single record-breaking attack [8], demonstrates the capacity of threat actors to disrupt critical online services.

Table 1 summarizes the key trends that form the basis for this research context:

Table 1.

Key Trends.

This trend underscores a reality where critical infrastructure, including future transportation networks, operates under constant siege. Besides, Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) represent A High-Value and a uniquely attractive and vulnerable target [14] for such attacks for several compelling reasons:

- -

- Complex Attack Surface: Modern AVs contain over 100 million lines of code and are equipped with multiple wireless communication interfaces, including 5G, Wi-Fi, Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X), and Bluetooth [15]. Each of these represents a potential entry point for a malicious actor.

- -

- Safety-Critical Dependencies: The core functionality of an AV perception, decision-making, and control is dependent on the unimpeded flow of data [16]. A successful DDoS attack can disrupt V2X communications, block critical Over-the-Air (OTA) updates, or flood internal vehicular networks, leading to a degradation or complete loss of operational capability.

- -

- Massive Impact: The compromise of an AV fleet has consequences far beyond financial loss. As highlighted by a 2025 automotive cybersecurity report, a single incident can affect thousands to millions of assets, posing a direct and immediate threat to passenger and public safety [17]. Real-world demonstrations, such as the offensive research conducted by Keen Security Lab on Tesla and BMW vehicles, have proven the feasibility of such compromises [18]. In addition, Traditional security measures are ill-equipped to counter the modern DDoS threat targeting AVs.

This research focuses on the detection and mitigation of Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks within the infrastructure supporting autonomous vehicles. Specifically, it addresses potent DDoS attack vectors, including volumetric, resource exhaustion, and amplification attacks, which can be leveraged to seize control of critical systems or cause significant operational damage. Furthermore, this work explores the implementation of Active Learning and Federated Learning techniques to defend against these DDoS vectors effectively.

The key contributions of this article are as follows:

- We present realistic DDoS attack scenarios that could critically disrupt autonomous vehicle infrastructure, leading to serious safety and operational consequences;

- We accurately identify and analyze the key network indicators that characterize the onset of each DDoS attack family. This stage leverages specialized deep learning models, CNN, RNN, and DNN, trained to learn multi-vector DDoS attacks from protocol-level anomalies (UDP, TCP-SYN, DNS);

- We integrate federated learning with active learning specifically for autonomous vehicle security, enabling collaborative, efficient, and privacy-aware detection of volumetric, state-exhaustion, and amplification attacks while maintaining high accuracy;

- We implement a synergistic Federated-Active learning architecture, designed for automotive ecosystem constraints to ensure scalable, accurate, and privacy-compliant defense against sophisticated DDoS attacks.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 examines the landscape of connected and autonomous vehicles, including their communication systems and architectural design. It then analyzes the core dangers and potential consequences of DDoS attacks, presenting specific threat scenarios against autonomous vehicle infrastructure. Section 3 synthesizes related scholarly work. The core contribution of our proposed methodology is detailed in Section 4, with its empirical validation and analysis provided in Section 5. The Discussion is presented in Section 6, where the principal findings of this study are analyzed and interpreted. The paper culminates in Section 7 with concluding remarks and a discussion of promising future research trajectories.

2. Background

Autonomous vehicles, also known as self-driving cars, use some technologies, including sensors, cameras, radar, GPS, Inertial Navigation Systems (INSs), and Vehicle-to-X (V2X) technologies, which consist of vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V), vehicle infrastructure (V2I), and vehicle-to-network communications [19]. Autonomous vehicles can communicate with the external environment, including other cars and roadside units; this is called vehicle-to-everything. Vehicle-to-vehicle, where cars can connect directly to each other using ad hoc wireless networks, formally called Vehicle Ad-Hoc Networks (VANETs), allows for cars to exchange information [20]. In addition to V2V, there is also vehicle to V2I, which is for communication between autonomous cars and infrastructure like roadside units placed on streets [21]. There are two ways for connectivity in V2X: dedicated short range communication (DSRC) consist for short range, it works best for vehicle-to-vehicle communication, and there is cellular V2X, which utilizes existing cellular networks [22]. In addition to these, there is satellite radio and Bluetooth for V2X applications [23]. The conceptual representation of the autonomous vehicle’s functional architecture comprises the following key elements:

A. Perception Layer: This is the vehicle’s senses. Its role is to detect, classify, and track all relevant objects and features in the environment [24]. This layer may include: Sensor Fusion (The core function that combines data from multiple sensors (cameras, LiDAR, radar, ultrasonic); Object Detection (Identifying what the objects are (e.g., vehicle, pedestrian, cyclist, traffic sign)); Object Tracking (Monitoring the position and velocity of detected objects over time); Localization (Determining the vehicle’s precise position (within centimeters) on a map, often using GPS, IMU, and LiDAR) [25].

B. Decision & Planning Layer: This is the vehicle’s brain. It uses the world model from the perception layer to make intelligent driving decisions [26]. This is often broken down into three sub-tasks: Route Planning (Calculating the optimal high-level route from the origin to the destination, similar to a navigation system); Behavioral (Tactical) Planning (Deciding the high-level maneuver based on traffic rules and other actors (e.g., change lanes, yield at the intersection, overtake the slow vehicle)); Motion (Operational) Planning (Generating a safe, comfortable, and feasible trajectory, the precise path and velocity profile to execute the chosen maneuver) [27].

C. Control Layer: This is the vehicle’s nervous system. It translates the planned trajectory from the planning layer into actual commands for the vehicle’s hardware [28].

A successful DDoS attack that processes real-time traffic data, the telecommunication networks enabling vehicle connectivity, or the traffic management infrastructure could lead to significant consequences [29], including: Disruption of real-time data exchange for collision avoidance systems; Halting of smart traffic systems, causing urban gridlock; Stoppage of commercial and logistics fleets dependent on autonomous technology.

Table 2 summarizes the core dangers and potential consequences of DDoS attacks on the autonomous vehicle ecosystem.

Table 2.

Core Dangers and Potential Consequences.

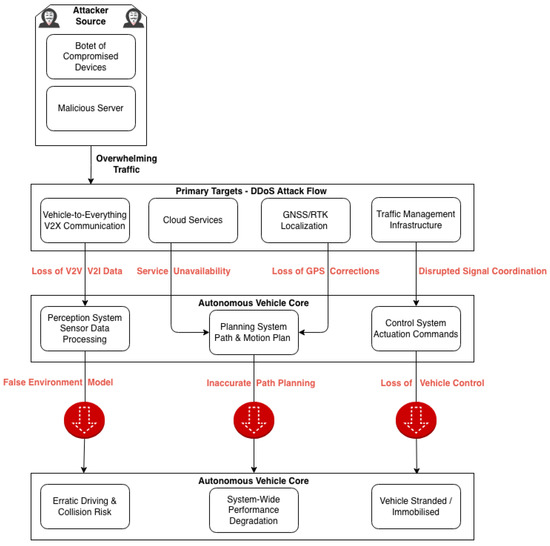

Figure 1 shows that DDoS attacks are particularly dangerous because they do not need to hack into a autonomous vehicle system, they simply need to overwhelm its capacity to function.

Figure 1.

DDoS Scenarios against Autonomous Vehicles with Consequences.

The attack begins with a multitude of compromised devices (a botnet) flooding the autonomous vehicle’s ecosystem with traffic. The channels for Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) and Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) communication are saturated. This prevents vehicles from sharing real-time safety information like collision warnings or cooperative adaptive cruise control data.

Cloud services platforms provide essential services like real-time high-definition maps, traffic data, and Over-the-Air (OTA) software updates [30]. A successful DDoS attack can render these services unavailable, stranding vehicles without up-to-date navigation information.

Autonomous vehicles often use Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) positioning for centimeter-level accuracy [31]. The data link between the GNSS rover and the reference station is vulnerable [32]. Research has shown that DDoS attacks can cause the sample rate of these systems to drop to as low as 5% of its normal rate, severely degrading localization accuracy and making safe autonomous operation impossible.

Besides, DDoS can target smart traffic lights, toll systems, and highway control servers. This can lead to hazardous road conditions at intersections.

3. Related Work

The landscape of DDoS detection and safety mechanisms for autonomous vehicles is reviewed in this section, with a focus on two dominant solution categories: Software-Defined Networking (SDN) and Machine Learning-based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs). Within ML-based IDS, the three primary detection paradigms, signature-based, anomaly-based, and specification-based, are examined. The anomaly-based approach has emerged as the most prevalent [33] and extensively applied technique for safeguarding vehicular systems.

The study in [34] addresses DoS and DDoS threats in vehicular networks by introducing a machine learning framework that leverages application-layer data through Random Projection (RP) and Randomized Matrix Factorization (RMF). The evaluation demonstrates the framework’s outstanding performance, particularly with models such as the Extra Tree Classifier (ETC), Logistic Regression (LR), and Random Forest (RF). In [35], the authors propose LiBSCOM-AS, a lightweight blockchain-based framework for Scalable and Collaborative DDoS Mitigation in SDN-Enabled Autonomous Systems. The system is implemented using Ethereum’s Ropsten for inter-domain Autonomous Systems (ASs) and Hyperledger Fabric for intra-domain AS. The work presented in [36] explores DDoS detection and mitigation in 5G-enabled Vehicular Ad-hoc Networks (VANETs) using multiple machine learning algorithms. The models, including Decision Trees, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines, and Neural Networks, were trained and evaluated on a combination of generated simulation data and the benchmark NSL-KDD dataset. Ref. [37] introduces a framework that jointly uses K-means clustering and Software-Defined Networking (SDN) to instantly detect and remove suspicious sensors causing DDoS attacks in the In-Vehicle Network (IVN). The authors of [38] employ a hybrid artificial intelligence model to identify DDoS assaults targeting the SDN controller in a Software-Defined VANET (SD-VANET) architecture. Their integrated detection module processes network traffic data, utilizing a combination of a one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) and a Decision Tree classifier. The study in [39] presents proof-of-concept experiments using a Hyperledger Fabric (HLF) Blockchain model to detect and prevent DDoS attacks in connected autonomous vehicles. The proposed method implements Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) as a consensus mechanism and a distributed firewall to ensure the ledger’s security and integrity. In [40], the authors develop an OpenAirInterface-based testbed for 5G Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) cybersecurity. They propose a deep learning-based model to detect DDoS attacks, which then triggers the creation of a resource-minimal sinkhole-type network slice to allow benign users to maintain normal communication with the mobility server. The work in [41] proposes an adversarial attack method designed to deceive an Intrusion Detection System (IDS). Using a substitute model trained with data from an onboard diagnostic port under black-box conditions, the method successfully causes misclassification of both normal traffic as malicious and malicious traffic as normal, all while adhering to realistic in-vehicle network traffic constraints. Ref. [42] proposes a real-time scheme to detect Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks and estimate their impact on a connected vehicle system. The scheme consists of a set of observers designed using sliding mode and adaptive estimation theory, with their mathematical convergence properties rigorously analyzed via Lyapunov’s stability theory. The study in [43] conducted experiments on a mini autonomous vehicle, executing DDoS attacks after an initial network scan. The recorded network traffic from all stages was used to train an AI-based detection mechanism. The resulting model’s efficiency was then evaluated by testing its ability to classify new network packets. Finally, the system proposed in [44] has been evaluated against both DDoS and impersonation attacks. The results show improved platoon formation times and enhanced attack mitigation performance compared to other benchmark systems.

A recurring limitation in existing studies is their insufficient consideration of the fundamental anatomy of DDoS attacks, particularly the initial triggering mechanisms. This oversight, coupled with a neglect of critical real-world evaluation metrics, most notably the performance in detecting zero-day attacks and maintaining a low false positive rate, undermines the practical reliability of proposed solutions. Without these assessments, it is difficult to gauge a model’s true effectiveness in operational environments.

In contrast, our model is designed to explicitly address these gaps. It incorporates an analysis of the DDoS attack chain and its triggering elements, providing more insightful detection. While achieving a high accuracy of 99.98%, our solution also demonstrates robust performance against zero-day DDoS attacks and a low false alarm rate, all within an efficient inference time. This comprehensive approach positions our model as a more practical and resilient defense for autonomous vehicles infrastructure.

4. Materials and Methods

This research aims to design and implement a specialized deep learning framework for the accurate and efficient detection of DDoS attacks targeting in-vehicle networks. The proposed models will be trained and validated using benchmark datasets, specifically the CIC-DDoS2019 [45] dataset. Performance will be rigorously assessed against a comprehensive set of metrics, with a strong emphasis on recall to minimize false negatives, thereby ensuring robustness and reliability in the safety-critical context of autonomous vehicle infrastructure.

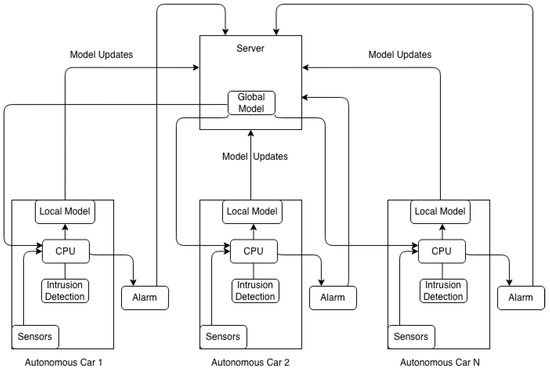

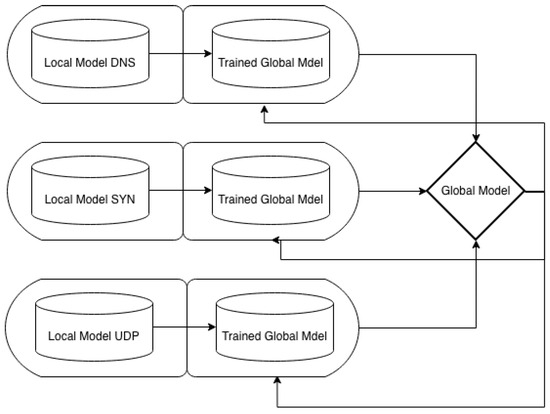

The proposed system architecture employs a Federated Learning (FL) framework for an Intrusion Detection System (IDS) designed to protect autonomous vehicles from three primary DDoS attack vectors: volumetric floods, state-exhaustion, and amplification attacks. The architecture consists of a central server and a fleet of autonomous vehicles. Each vehicle collects network traffic data from its internal sensors and systems. These data are preprocessed locally by the vehicle’s computing unit to train a deep learning model specifically tailored to recognize one type of DDoS attack. Consequently, each vehicle develops a localized model capable of periodically detecting its assigned attack type without sharing raw data, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

System Infrastructure.

Our framework leverages active learning to maximize data efficiency, with each client selecting the most informative samples for local training. The core federated learning cycle involves clients computing model gradients on their local data and transmitting these updates to a central server. The server aggregates the updates to generate a refined global model, which is then redistributed to the client vehicles.

This iterative process converges on a powerful, globally trained IDS. The final model is deployed on each vehicle to perform real-time detection of all three DDoS attack types. Upon detection, vehicles generate an immediate alert to the central server for incident response.

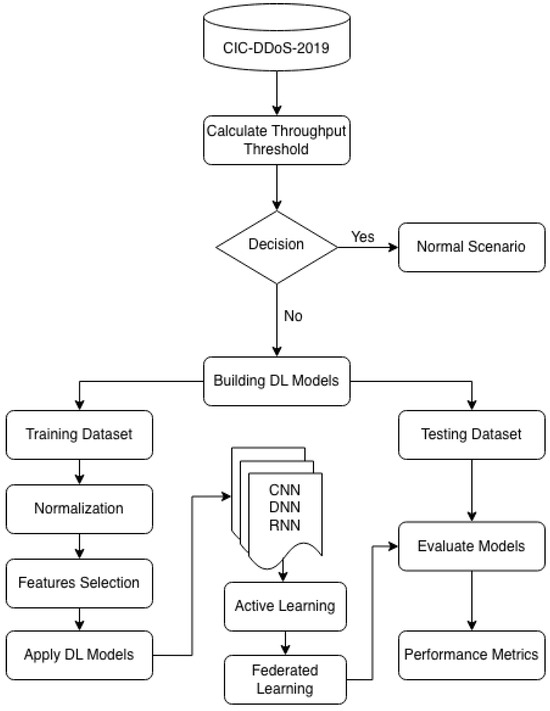

Our methodology begins by establishing a throughput threshold to differentiate between benign operational traffic and potential DDoS attack scenarios. The data then undergoes a rigorous preparation phase, which includes feature normalization and an optimized selection process to retain the most discriminative inputs for model training.

We leverage a suite of deep learning architectures, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), to capture both spatial and temporal patterns in network traffic. To maximize data efficiency and privacy, we integrate these models within a federated learning framework, augmented with active learning. This allows for decentralized training across vehicle nodes and iterative model refinement by selecting the most informative data samples.

Model efficacy is rigorously quantified using a standard set of metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score and false positive rate. This comprehensive evaluation provides a multifaceted view of performance and serves as the definitive criterion for selecting the optimal model for deployment. Figure 3 depicts the architecture of our proposed system, which leverages a synergy of Deep Learning (DL), Federated Learning and Active Learning to achieve robust and efficient DDoS detection.

Figure 3.

System Architecture.

This study utilizes the CIC-DDoS2019 dataset, a comprehensive benchmark provided by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity. The dataset contains over 14,000 meticulously labeled instances of both benign and malicious network traffic. Its key strength lies in the diversity of its captured DDoS attacks, which includes major categories such as UDP Flood, TCP Flood, and HTTP Flood, each further subdivided into numerous subtypes to model a wide spectrum of real-world attack vectors.

This granularity, coupled with a similarly varied set of normal traffic profiles, makes CIC-DDoS2019 particularly advantageous for developing robust machine learning-based intrusion detection systems. The dataset’s breadth directly addresses the critical challenge of minimizing false positives by ensuring models are exposed to a rich tapestry of normal behavior, thereby fostering the creation of detectors that accurately discriminate between legitimate traffic and attacks. Table 3 shows a detail of the used data set.

Table 3.

Description of the dataset contents.

Data preprocessing and exploratory analysis are foundational to our modeling pipeline. This phase involves a comprehensive reformatting of the dataset and a rigorous examination of its variables to inform an effective modeling strategy. Based on the insights gained, we pursued a dual-classification approach to evaluate detection performance comprehensively. The study was conducted using both binary classification (normal vs. attack) and multi-class classification (identifying specific attack types), following a consistent data processing and evaluation workflow for both.

Data preprocessing is a critical stage in the machine learning pipeline, essential for transforming raw data into a suitable format for model training. Real-world datasets often contain noise, inconsistencies, and artifacts such as missing values, infinite numbers, and outliers that can significantly degrade model performance and generalizability if left unaddressed. The primary goal of preprocessing is to mitigate these issues to ensure the development of robust and reliable models.

This study implements a comprehensive preprocessing procedure, which includes:

Data Cleaning: To ensure data integrity and model compatibility, we implemented a rigorous data cleaning procedure. First, all infinite values were replaced with NaN to standardize missing data representation. Subsequently, any row containing a NaN value was removed via listwise deletion to create a complete-case dataset. This step is critical, as the presence of missing or infinite values can lead to numerical instability and training failures in machine learning models.

Furthermore, we removed several metadata and identifier columns that do not contribute to the discriminative power of a DDoS detection model. The dropped features include Unnamed: 0, Flow ID, Source IP, Source Port, Destination IP, Destination Port, SimilarHTTP, and Timestamp. Their exclusion prevents the model from learning non-generalizable patterns based on unique identifiers or transient connection metadata, thereby improving its ability to generalize to new, unseen network flows.

Encoding: In this preprocessing step, the target labels were encoded to facilitate both binary and multi-class classification. For the binary classification task, the LabelEncoder from the scikit-learn library was employed to transform the labels into a binary format, where 1 represents any DDoS attack and 0 represents benign traffic. For the subsequent multi-class classification task, the same encoder was used to assign a unique integer to each specific attack type (e.g., UDP flood, TCP flood), while benign traffic was maintained as a separate class.

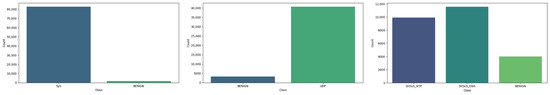

Handling Class Imbalance: Prior to model training, we analyzed the distribution of our target variables. As illustrated in the figure below, we observed a significant class imbalance across all classification tasks. This includes the binary classification scenarios (e.g., Benign vs. UDP Flood, Benign vs. SYN Flood) and the multi-classification scenario for Amplification attacks (e.g., Benign, DNS, NTP).

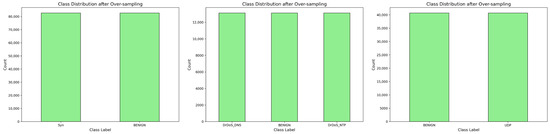

To address this, we employed the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE). SMOTE mitigates class imbalance by generating synthetic instances of the minority classes through interpolation between existing, neighboring minority samples. This process creates a more balanced training dataset, which is crucial for preventing model bias toward the majority class. Consequently, the use of SMOTE helps to alleviate overfitting, improves the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data, and leads to more robust overall performance. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the visualization of labels before and after preprocessing.

Figure 4.

Visualization of Labels before Preprocessing.

Figure 5.

Visualization of Labels After Preprocessing.

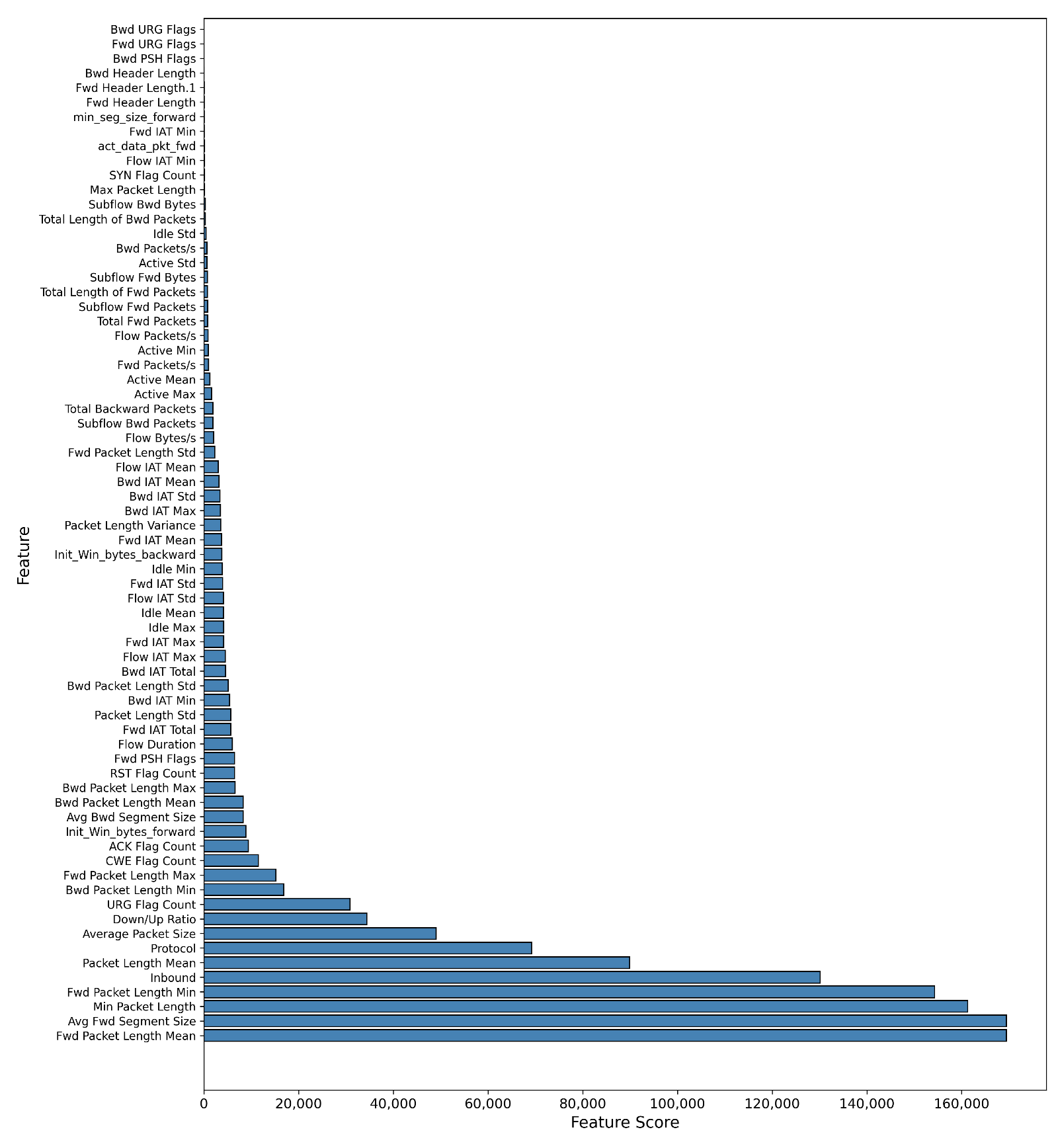

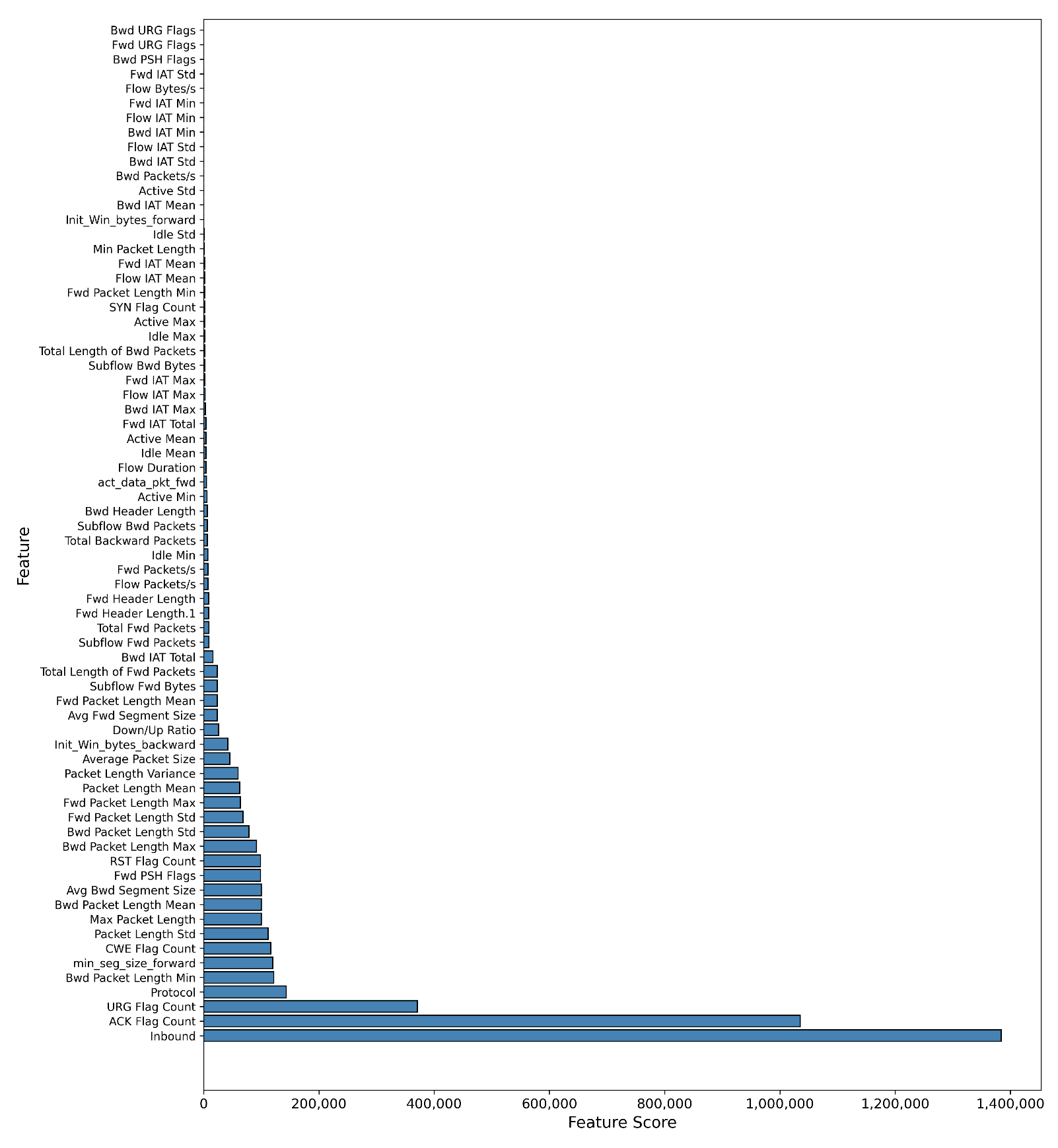

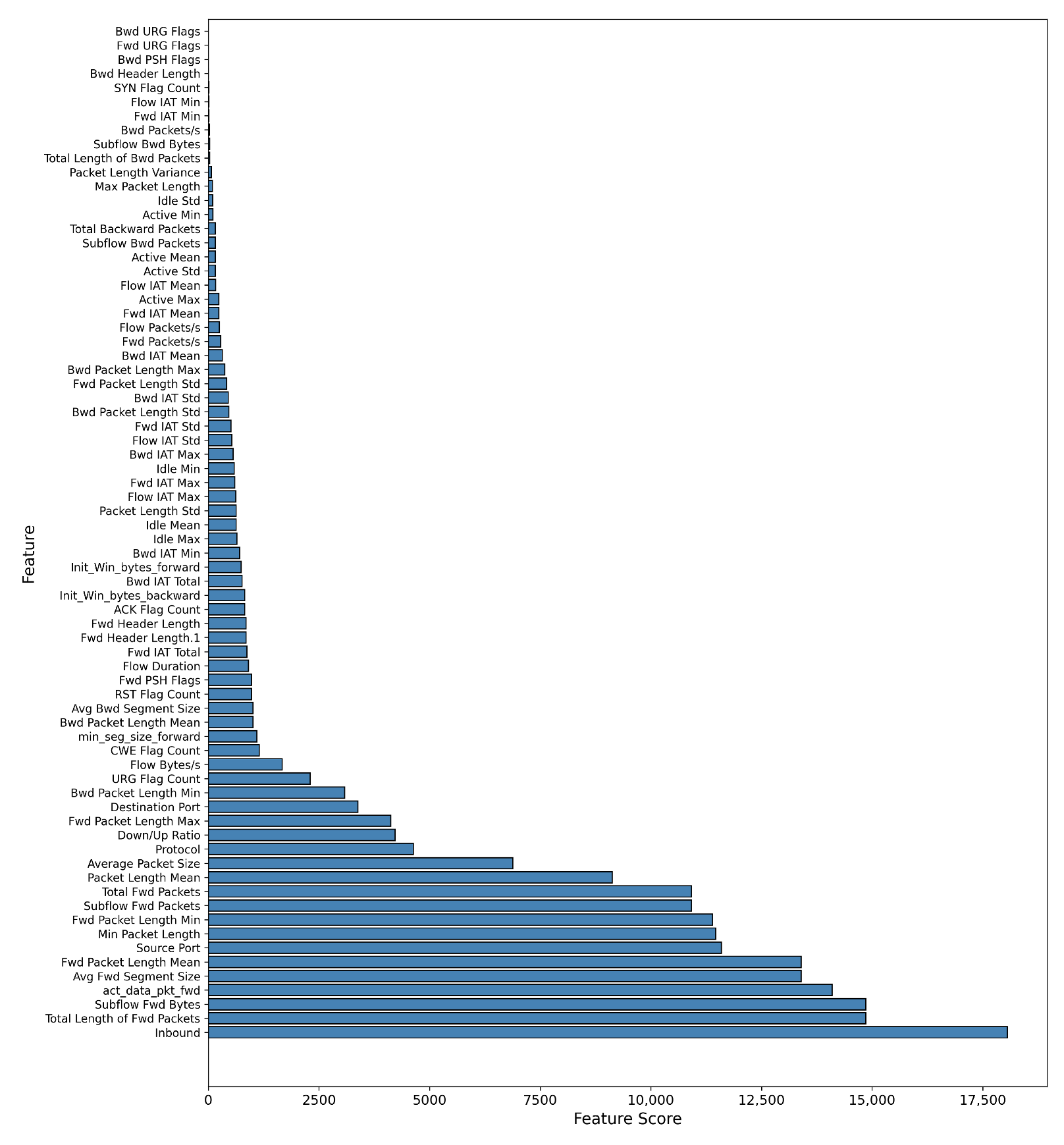

Feature Selection: To address the high dimensionality of the dataset, we implemented a feature selection step using the SelectKBest method with the f_classif scoring function from scikit-learn. This approach identifies the ’K’ most statistically significant features for our classification task, which improves model efficiency and performance. The selected features for each dataset are shown in the accompanying Table 4.

Table 4.

Feature selection for Binary and Multiple attack classification.

Standardization/Normalization: Prior to model training, we implemented a critical data preprocessing pipeline to ensure robust and generalizable results. This involved two key steps: data scaling and dataset splitting.

First, we applied standardization (Z-score normalization) to scale all numerical features. This process transforms the data to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, ensuring that all input features contribute equally to the model’s learning process without being biased by their original scales. This leads to more stable convergence during training and improved model performance.

Subsequently, the entire dataset was partitioned into dedicated subsets for training and evaluation. We employed a standard hold-out validation strategy, allocating 80% of the data for training the models and reserving the remaining 20% as an unseen test set. This strict separation guarantees that the final evaluation reflects the model’s true ability to generalize to new, unseen data.

Models Architecture

This study implements and evaluates three distinct deep learning architectures, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), for the classification of DDoS attacks, including volumetric, state-exhaustion and amplification-based attacks.

Each model is structured with input, hidden, and output layers. The input layer receives the preprocessed features, which are appropriately reshaped to suit each architecture. Specifically, CNNs require a 2D structure for spatial feature extraction, while RNNs expect a sequential format to model temporal dependencies. The hidden layers across all models predominantly use the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function to introduce non-linearity and mitigate the vanishing gradient problem.

The configuration of the output layer is task-dependent. For binary classification (e.g., benign vs. attack), the output layer consists of a single neuron with a sigmoid activation function, which outputs a value between 0 and 1. A prediction threshold of 0.5 is used to discriminate between classes. For multi-class classification (e.g., identifying specific attack types), the output layer utilizes a softmax activation function. This function assigns a probability to each class, and the class with the highest probability is selected as the prediction.

All models were compiled using the Adam optimizer for efficient gradient-based learning. The loss function was selected according to the task: binary cross-entropy for binary classification and sparse categorical cross-entropy for multi-class classification. To enhance generalization and prevent overfitting, we integrated dropout layers into the models and employed an early stopping callback to halt training when validation performance ceased to improve.

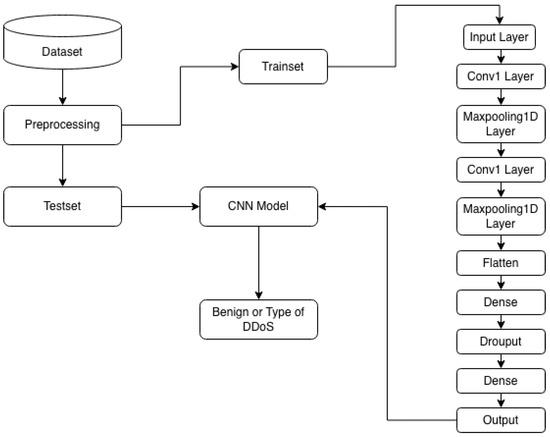

DDoS classification based on CNN

The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture is designed to hierarchically extract spatial features from the input data. It is composed of an input layer, a sequence of convolutional blocks (convolution, activation, pooling), fully connected layers, and an output layer.

The process begins with convolutional layers, which apply a set of learnable filters to the input to detect local patterns and create feature maps. These maps are then passed through an activation function (ReLU) to introduce non-linearity. Subsequently, pooling layers (e.g., Max Pooling) downsample the feature maps, reducing their spatial dimensions. This serves to decrease computational complexity, provide translational invariance, and help prevent overfitting.

The resulting features are then flattened into a one-dimensional vector and fed into fully connected (dense) layers. These layers perform high-level reasoning and ultimately connect to the output layer, which uses a sigmoid activation function for binary classification (’normal’ vs. ’DDoS attack’). Figure 6 illustrates the DDoS attack classification process implemented using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN).

Figure 6.

DDoS classification based on CNN.

The implemented one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture is structured as follows:

Two Convolutional Blocks: The model begins with two 1D convolutional layers (Conv1D). The first layer employs 32 filters, and the second layer employs 64 filters. Each convolutional layer is followed by a 1D max-pooling layer with a pool size of 2 to reduce dimensionality and extract salient features.

Classification Head: The output from the final pooling layer is flattened into a one-dimensional vector. This vector is then fed into a fully connected (Dense) layer with 128 units and a ReLU activation function.

Regularization: To mitigate overfitting, a Dropout layer with a rate of 0.5 is applied after the dense layer.

Output Layer: The final layer is a Dense layer configured for the specific classification task:

1 unit with a sigmoid activation function for binary classification.

N units with a softmax activation function for multi-class classification (where N is the number of classes).

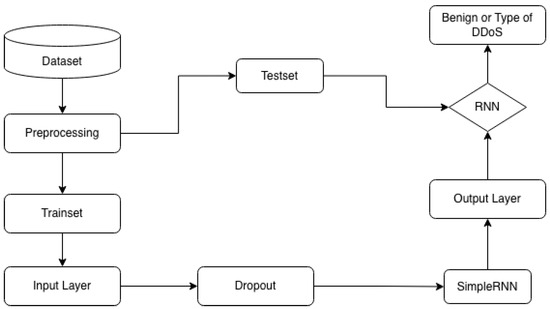

DDoS classification based on RNN

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are particularly effective for sequential data, as demonstrated in applications like handwriting and speech recognition. Their ability to learn temporal dependencies through backpropagation makes them well-suited for classifying time-series network traffic. Figure 7 elucidates the DDoS attack classification process implemented using a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN).

Figure 7.

DDoS classification based on RNN.

A Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) was selected for this study due to its capacity to model temporal sequences, which is well-suited for analyzing the time-series nature of network traffic in our large-scale dataset.

We constructed a simple RNN architecture, culminating in an output layer configured for our classification task. To achieve optimal performance, we conducted a series of experiments to tune key hyperparameters.

A critical preprocessing step involved reshaping the data into a temporal format compatible with RNN input requirements. The training and test sets were transformed into 3D NumPy arrays of the shape (samples, timesteps, features). For our initial model, we defined this structure as (number_of_instances, 1, number_of_features), effectively treating each sample as a single timestep containing all features.

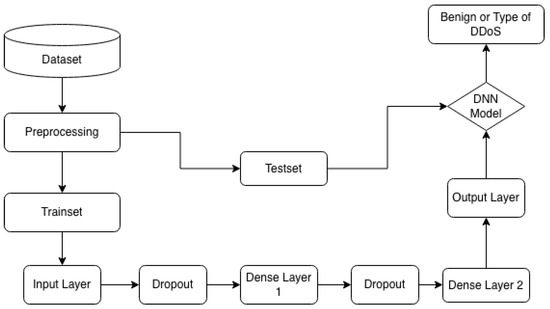

DDoS classification based on DNN

We constructed a Deep Neural Network (DNN) comprising an input layer, two hidden dense layers, and an output layer. Through an iterative process of hyperparameter tuning, we determined the optimal number of neurons for each layer. The final configuration employs 32 units in both the input and hidden layers. Figure 5 illustrates the complete architecture of our DNN model. Figure 8 depicts the DDoS attack classification process implemented using a Deep Neural Network (DNN).

Figure 8.

DDoS classification based on DNN.

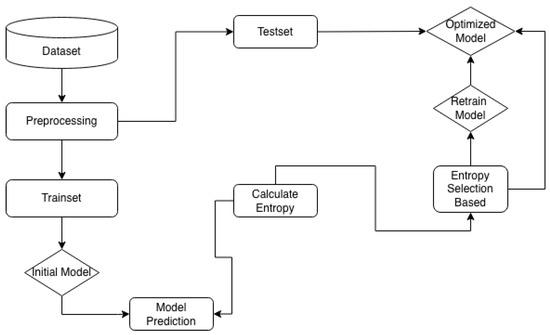

Active Learning:

We integrated an active learning strategy with the three previously discussed models (CNN, DNN, and RNN), applying a consistent implementation across all architectures. While active learning is traditionally used to selectively label data from a large unlabeled pool, we repurposed its core principle for our fully labeled dataset. The rationale is that not all labeled instances contribute equally to a model’s learning; some are redundant or less informative.

Therefore, our approach uses the active learning query strategy to iteratively select only the most informative data points from the entire labeled dataset. This creates a curated, high-value training subset. By training on this optimized subset, we aim to enhance model performance and increase computational efficiency, preventing the model from being hindered by non-informative examples. Figure 9 outlines the active learning process.

Figure 9.

Active learning process.

Our approach adapts the principles of active learning for a fully labeled dataset. Unlike traditional methods that query an oracle to label new data, our method employs an uncertainty-based sampling strategy, specifically an entropy-based query, to identify the most informative instances within the existing labeled data. This strategy selects samples where the model’s predictions exhibit the highest uncertainty, as these represent the most challenging and pedagogically valuable examples for the learner.

The implemented workflow is as follows:

- The dataset is initially split into training, validation, and test sets.

- The model is trained for a single epoch on the current training set.

- The model then performs inference on the entire dataset, and the predictive entropy for each instance is calculated.

- Instances with the highest entropy, indicating maximum model uncertainty, are selected from the pool and added to the training set for the next iteration.

- This process is repeated for a predefined number of cycles, progressively curating a training set composed of the most valuable data points. This forces the model to focus its learning effort on the most ambiguous and critical examples, thereby enhancing its discriminative capabilities and leading to more robust future predictions.

Federated learning

We employ a Federated Learning (FL) framework to enable collaborative training of intrusion detection models across multiple clients (e.g., vehicles or edge devices). This approach allows for the collective improvement of a global model to identify attack patterns without the need to centralize or disclose any private, raw data.

The process begins locally on each client:

- Local Preprocessing: Each client preprocesses its own network traffic data, which involves cleaning, feature extraction, and scaling to prepare it for the chosen deep learning model (CNN, RNN, or DNN).

- Local Training: The client then performs a training epoch on its local dataset. This involves using an optimization algorithm, typically a variant of Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), to compute an update to the model. Crucially, this update is in the form of gradients (the mathematical adjustments needed to minimize error), not the raw data itself.

- Secure Aggregation: These gradient updates from all participating clients are sent to a central server.

- Global Model Update: The server aggregates these gradients (e.g., by averaging) to update a global model, which is then redistributed to the clients for the next round of learning. Figure 10 shows the federated learning process.

Figure 10. Federated learning process.

Figure 10. Federated learning process.

The federated training process, executed by the server using FLAD, is detailed in Algorithms 1 and 2. The corresponding local training process, executed by the clients using a DNN model with Active Learning, is outlined in Algorithm 3.

Client selection for each subsequent training round is managed implicitly by the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) strategy, implemented on the server side using the Flower (’Flwr’) framework.

| Algorithm 1 Global model for Federated learning |

|

| Algorithm 2 Select Clients for Next Round of Training |

|

In the following, we present the mathematical formalization of the proposed federated and active learning framework for DDoS detection in vehicular networks. The formulation ensures collaborative learning while preserving data privacy and optimizing computational efficiency across participating vehicles.

- 1.

- Problem Setup

Let be vehicular clients. Each client K has a local dataset where denotes the traffic class (benign or one of three DDoS types).

- 2.

- Active Learning at Local Clients

At round t, client K selects an informative subset via uncertainty sampling:

The local cross-entropy loss on this subset is:

- 3.

- Federated Aggregation

Selected clients perform E epochs of SGD, then transmit updates to the server. The global model is updated via weighted averaging:

- 4.

- Detection Performance

The system’s efficacy is measured by the global false positive rate:

and the attack-type-specific recall:

| Algorithm 3 Local training procedure at client c |

|

5. Evaluation and Results

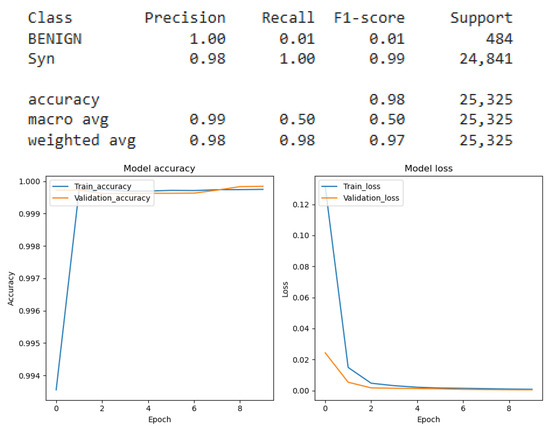

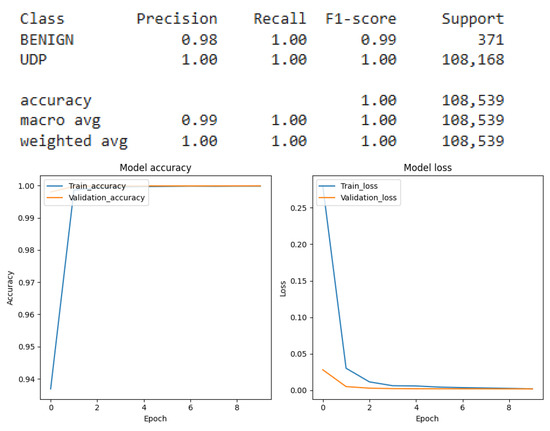

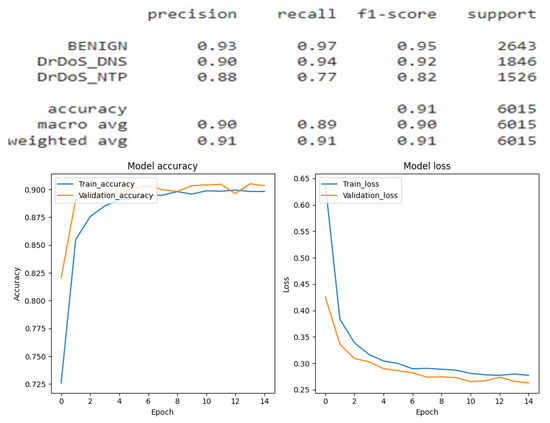

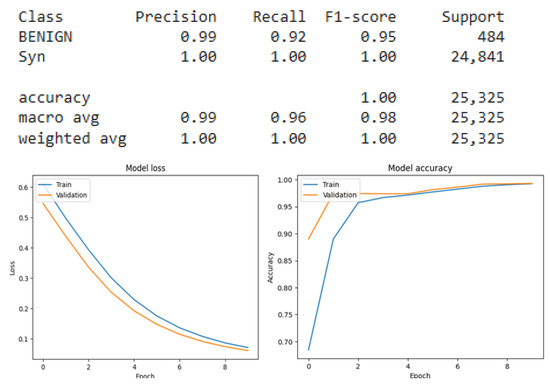

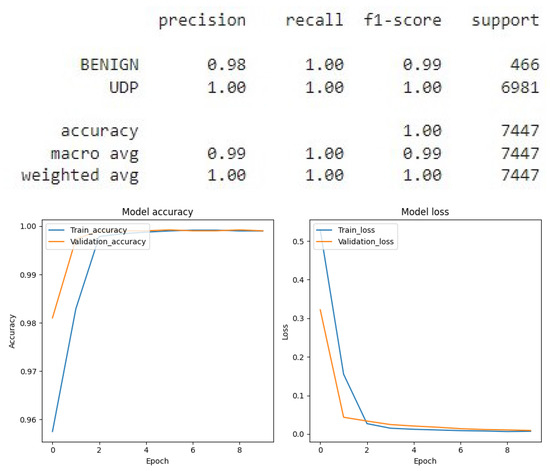

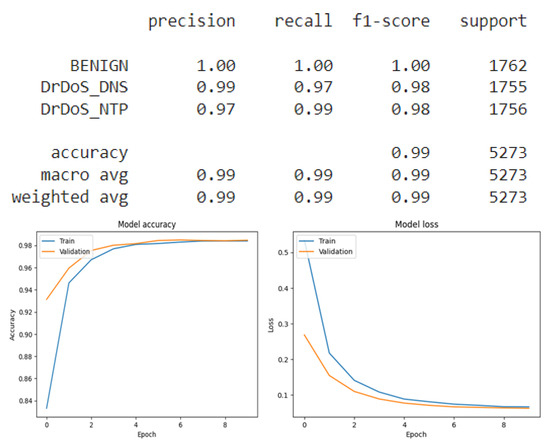

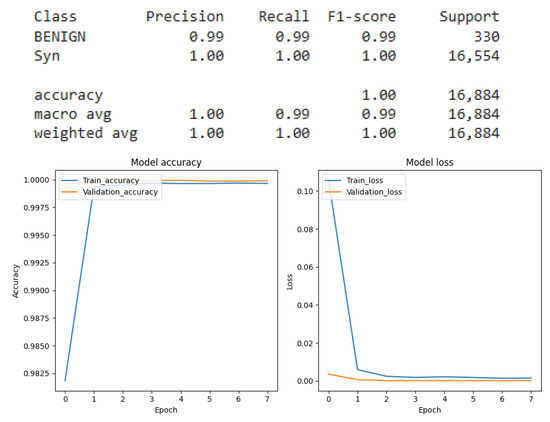

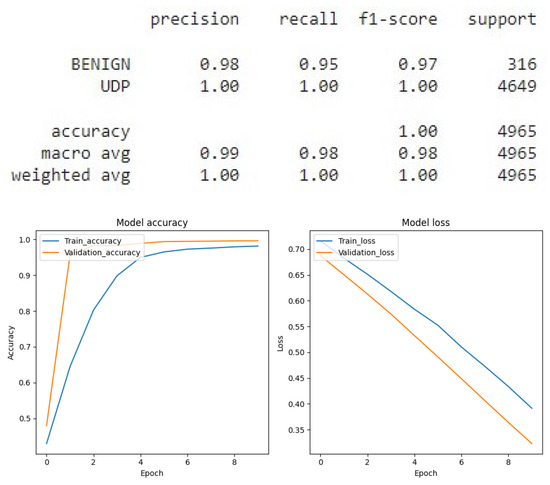

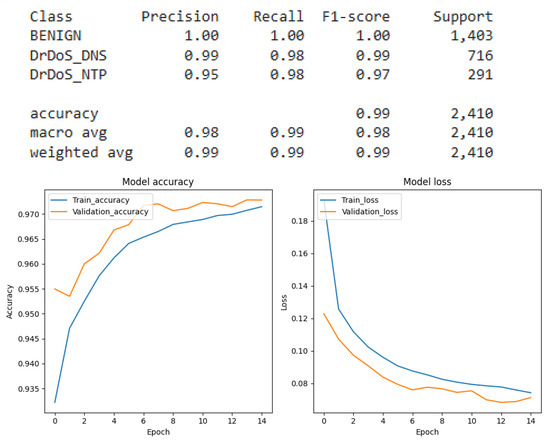

The primary objective of this research was to develop and evaluate a robust intrusion detection system capable of identifying multiple DDoS attack vectors namely volumetric, amplification, and state-exhaustion attacks. To this end, we implemented and compared a suite of deep learning architectures, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). Each model was rigorously trained and evaluated under two distinct classification paradigms: binary (benign vs. attack) and multi-class (identifying the specific attack type). Through extensive hyperparameter tuning, we optimized each model’s configuration. A detailed performance analysis, based on the experimental results from the test dataset, is provided in Figure 11 which presents the results of the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) applied to the binary classification of SYN flags, Figure 12 which presents the results of the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) applied to the binary classification of UDP protocol, Figure 13 which provides the results of the multiclass classification analysis conducted using the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) model, Figure 14 which presents the results of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) applied to the binary classification of SYN flags, Figure 15 which presents the results of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) applied to the binary classification of UDP protocol, Figure 16 which provides the results of the multiclass classification analysis conducted using the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model, Figure 17 which presents the results of the Deep Neural Network (DNN) applied to the binary classification of SYN flags, Figure 18 which presents the results of the Deep Neural Network (DNN) applied to the binary classification of UDP protocol and Figure 19 which provides the results of the multiclass classification analysis conducted using the Deep Neural Network (DNN) model.

Figure 11.

RNN result for SYN binary classification.

Figure 12.

RNN result for UDP binary classification.

Figure 13.

RNN result for multiclass classification.

Figure 14.

CNN result for SYN Binary classification.

Figure 15.

CNN result for UDP Binary classification.

Figure 16.

CNN result for multiclass classification.

Figure 17.

DNN result for SYN Binary classification.

Figure 18.

DNN result for UDP Binary classification.

Figure 19.

DNN result for multiclass classification.

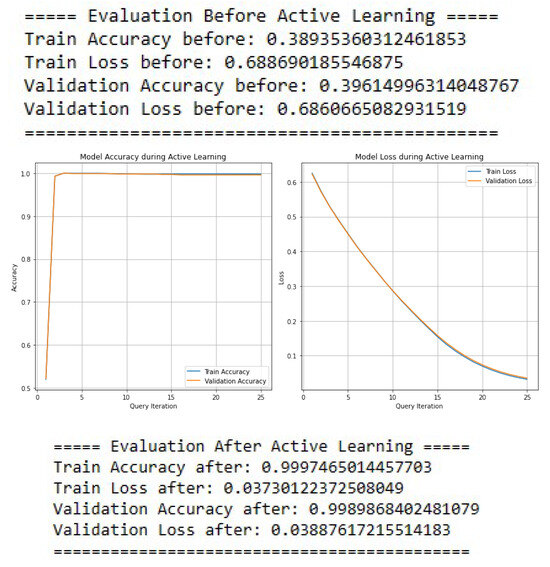

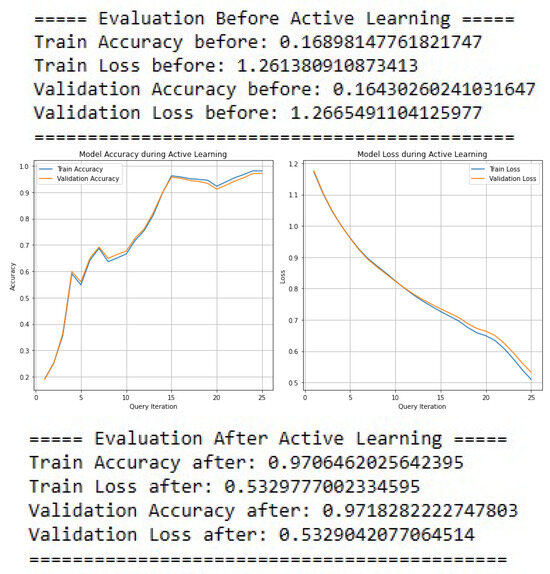

Our comparative analysis revealed that the DNN model delivered the best performance and adaptability for the IDS. We therefore focused on refining this model through active learning. Figure 20 shows a comparative analysis of UDP classification performance using a Deep Neural Network (DNN), contrasting the results before and after the integration of Active Learning.

Figure 20.

Active learning results for UDP classification using DNN.

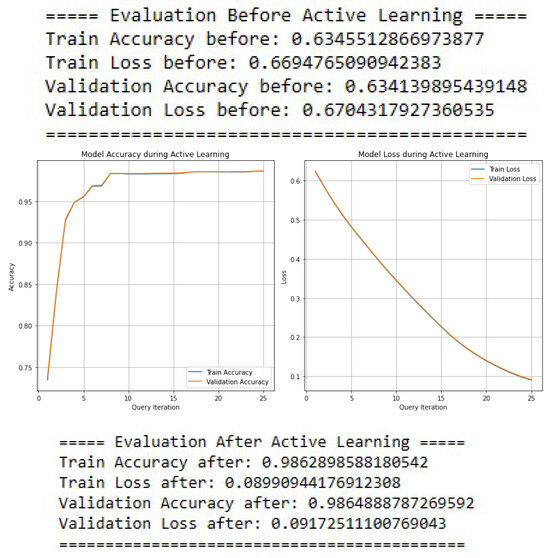

The impact of Active Learning on a Deep Neural Network (DNN) for SYN classification is evaluated in Figure 21, which contrasts the model’s performance before and after its integration.

Figure 21.

Active learning results for SYN classification using DNN.

Figure 22 presents a comparative analysis of the DNN’s performance on multiclass classification before and after the implementation of Active Learning.

Figure 22.

Active learning results for multiclass classification using DNN.

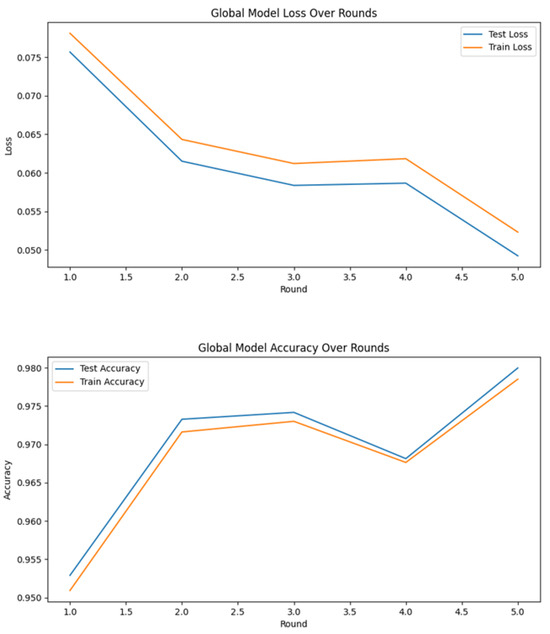

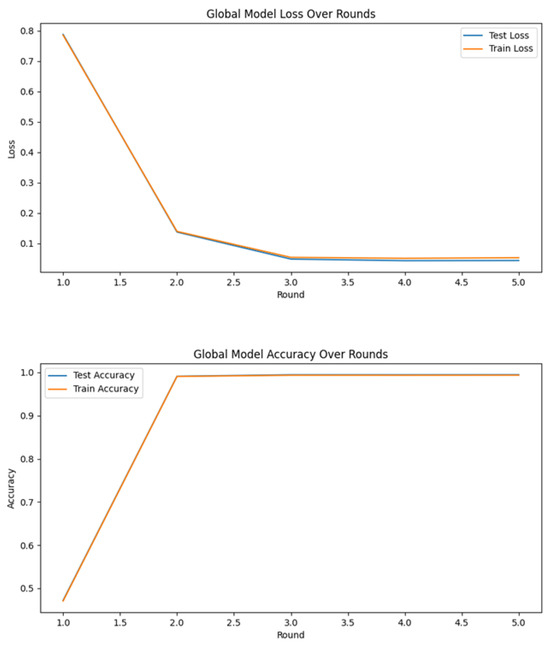

In the final phase, we deployed a federated learning framework using the DNN model, which demonstrated superior performance in our prior comparative analysis. This federated architecture, augmented with the active learning techniques previously described, further enhances the model’s efficacy. The system was trained to detect three primary DDoS attack types: Amplification, Volumetric, and State-Exhaustion. The results of this integrated approach are presented in the figure below.

Figure 23 presents the performance of the Deep Neural Network (DNN) within a Federated Learning framework, excluding the use of Active Learning.

Figure 23.

Federated learning without active learning results using DNN.

Figure 24 shows the results of the Deep Neural Network (DNN) model that integrates both Federated Learning and Active Learning.

Figure 24.

Federated learning and active learning results using DNN.

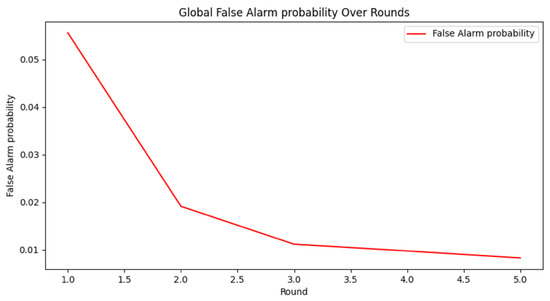

As depicted in Figure 25, the global false alarm rate exhibits a consistent monotonic decrease across successive federated communication rounds, converging from an initial 5% to a stable 1%. This empirical trend demonstrates the efficacy of the federated learning process in collaboratively refining model parameters to minimize erroneous alerts and systematically improve overall network specificity.

Figure 25.

False alarm rate.

This section details the evaluation metrics employed to assess the performance of our proposed intrusion detection system. A robust evaluation is critical for understanding a model’s real-world applicability, particularly in security contexts where different types of errors carry different consequences. We report on standard classification metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-score to provide a comprehensive view of model efficacy.

Precision quantifies the reliability of a model’s positive predictions. It is defined as the proportion of correctly identified DDoS attacks (True Positives) among all instances the model classified as an attack (both True Positives and False Positives). A high precision indicates a low rate of false alarms. Precision is calculated as follows:

Recall (or Sensitivity) measures the model’s ability to detect all actual DDoS attacks. It is defined as the proportion of actual DDoS attacks that were correctly identified. A high recall indicates that the model misses few attacks. Recall is calculated as:

F1-Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances the trade-off between the two. It is especially useful when dealing with imbalanced datasets. The F1-score is calculated as:

False Positive Rate measures the percentage of legitimate/normal network traffic that your system incorrectly flags as a DDoS attack.

Accuracy measures the overall correctness of the model across all classes. However, it can be a misleading metric on imbalanced datasets where one class (e.g., benign traffic) significantly outnumbers the other (e.g., attack traffic).

The efficacy of the proposed system is evaluated through a comparative analysis with existing literature, as detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparative study.

Algorithm 1 details the global federated learning model. The key factors affecting its computational complexity are the number of participating clients (vehicles) K, the size of local datasets , the number of model parameters W, and the total communication rounds T. Each client performs local training on its dataset, which requires approximately **W floating-point operations, where is the number of local epochs. Therefore, the overall computational complexity for Algorithm 1 can be expressed as O(T*K***W).

Algorithm 2, which handles client selection and model aggregation, operates over T communication rounds. Selecting K clients and aggregating their model updates W in each round results in a complexity of O(T*K*W). Algorithm 3 governs the active learning cycles performed locally by each client. Within each of the active learning cycles, a client processes a subset where of its dataset to compute predictions and update the model. This yields a per-client complexity of O(*W*). Collectively, all components of the proposed framework scale linearly with respect to the number of clients, local epochs, dataset size, and model parameters, confirming an overall polynomial time complexity. This demonstrates the computational scalability of the proposed approach for large-scale, multi-vehicle autonomous systems.

In our experiments, the local training phase at each client required approximately 25 s per communication round. The inference phase, processing the complete CIC-DDoS2019 test dataset, took about 0.01 s, highlighting the efficiency of the deployed global model.

These results are comparable to state-of-the-art deep learning-based IDS approaches. For instance, the study reported training times between 6 and 29 s for CNN-BiLSTM models on the same dataset, with their best-performing model requiring 29 s. Another study achieved an inference latency of 0.509 ms per network frame using a deep neural network. Comparative work by [51] demonstrated that a Bayesian-optimized decision tree classifier required 25.851 s for training, while KNN and SVM required 68.632 and 592.97 s, respectively; their decision tree model also processed the complete test dataset in approximately 0.01 s. This comparative analysis confirms that the runtime performance of our federated and active learning-integrated framework remains competitive without compromising its advantages in privacy preservation and collaborative learning.

6. Discussion

This study proposed and evaluated a novel, privacy-preserving Intrusion Detection System designed to detect DDoS attacks targeting autonomous vehicle infrastructure. The system strategically integrates Active Learning within a Federated Learning framework to address critical challenges in modern DDoS defense: the sophistication of attacks, the scarcity of labeled data, and the paramount need for data privacy across distributed vehicular networks. The core innovation lies in the synergistic combination of Federated Learning and Active Learning. The proposed system enables the collaborative training of a robust global detection model without sharing raw, sensitive data, a fundamental requirement for the automotive industry. Simultaneously, the integration of an active learning strategy addresses a key bottleneck in federated learning: data quality and efficiency. By intelligently querying only the most informative data samples from each federated node, the active learning optimizes the learning process, mitigates the risks of overfitting on non-representative local data, and reduces the labeling burden.

The proposed framework’s efficacy was validated using the CIC-DDoS2019 dataset, with a comparative analysis of deep learning architectures, Convolutional Neural Networks, Recurrent Neural Networks, and Deep Neural Networks, enhanced by the Active Learning strategy. As summarized in Table 5. Our model demonstrates competitive performance compared to prior state-of-the-art methods cited in the literature. This performance gain can be attributed to our framework’s direct confrontation of two major DDoS challenges. First, it counters the inherent complexity and sophistication of modern DDoS attacks, including volumetric, exhaustion-state, and amplification assaults through the representational power of deep learning models trained on diverse, federated data. Second, and more critically, it enhances the detection of elusive Application-layer DDoS attacks, which masquerade as legitimate traffic at lower network layers. The Active Learning refined models learn subtler, higher-order patterns indicative of these sophisticated intrusions, which traditional signature-based or anomaly detection systems often miss. The framework establishes a scalable and adaptive foundation for securing the critical autonomous vehicle infrastructure upon which the safe operation of autonomous vehicles depends.

While the results are promising, this study acknowledges certain limitations. The evaluation was conducted on a benchmark dataset. Further validation is required in real-world, in-vehicle network testbeds with live traffic and hardware to assess performance under realistic latency and resource constraints. Furthermore, the integration of active learning, while improving data efficiency, may introduce non-trivial computational overhead due to its iterative model querying and retraining cycles, a trade-off that requires further optimization for resource-constrained edge devices in vehicles.

7. Conclusions

The escalating global DDoS threat landscape makes autonomous vehicles (AVs), with their complex reliance on continuous data exchange, particularly vulnerable targets. These vehicles function as business-critical data systems, incorporating millions of lines of code and multiple communication interfaces (V2X, 5G, in-vehicle networks), creating a broad attack surface. This research addresses the critical challenge of detecting sophisticated DDoS attacks, specifically volumetric, amplification, and state-exhaustion variants within autonomous vehicle infrastructure. We proposed a novel intrusion detection system that employs a comparative analysis of deep learning architectures, including CNN, RNN, and DNN. Each model is enhanced by an active learning strategy to optimize data efficiency. The final IDS was deployed within a federated learning framework, producing a global model capable of detecting multiple DDoS attack types with high precision while rigorously maintaining data privacy. Our approach achieved a remarkable accuracy of 99.89%, demonstrating its potential for effective real-time threat detection and response in distributed automotive networks. As future work, a key direction involves integrating blockchain technology to establish a secure, transparent, and fully decentralized framework for sharing model updates and threat intelligence. To bolster trust and deployment readiness, we plan to investigate the model’s resilience against adversarial machine learning attacks designed to evade detection. Concurrently, integrating Explainable AI (XAI) techniques is crucial to interpret the model’s decisions, providing security analysts with actionable insights.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D., S.T. and R.O.; Methodology, A.D., S.T. and R.O.; Validation, A.D.; Formal analysis, S.T. and R.O.; Investigation, A.D., S.T. and R.O.; Writing—original draft, A.D., R.O. and S.T.; Writing—review and editing, A.D. and U.J.B.; Supervision, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ddos-2019.html.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by Ajman University for covering the publication charges.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ignatious, H.A.; Khan, M. An overview of sensors in Autonomous Vehicles. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 198, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmaja, B.; Moorthy, C.V.; Venkateswarulu, N.; Bala, M.M. Exploration of issues, challenges and latest developments in autonomous cars. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.; Alsweiss, S.; Toker, O.; Razdan, R.; Santos, J. An overview of autonomous vehicles sensors and their vulnerability to weather conditions. Sensors 2021, 21, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.A.; Fernando, X.N.; Kashef, R. A Survey on Artificial Intelligence based Internet of Vehicles utilizing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Drones 2024, 8, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targeted by 20.5 Million DDoS Attacks. Available online: https://blog.cloudflare.com/ddos-threat-report-for-2025-q1/ (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- The DDoS Arms Race. Available online: https://breached.company/the-ddos-arms-race-how-2025-became-the-year-of-record-breaking-cyber-assaults/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- DDoS Attacks: What the Alarming New Data Reveals. Available online: https://deepstrike.io/blog/ddos-attack-statistics (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- TMirai IoT Botnet Powers Record 5.6 Tbps DDoS Attack. Available online: https://edisonsmart.com/mirai-iot-botnet-powers-record-5-6-tbps-ddos-attack/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Record-Breaking 5.6 Tbps DDoS. Available online: https://blog.cloudflare.com/ddos-threat-report-for-2024-q4/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- DDoS Attacks Report. Available online: https://stormwall.network/resources/blog/ddos-attack-statistics-2024 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- DDoS Peak Attack Volumes Doubled in H2 2023. Available online: https://gcore.com/press-releases/gcore-radar-report-reveals-ddos-peak-attack-volumes-doubled-in-h2-2023 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- The Autonomous Vehicle Market. Available online: https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/autonomous-vehicle-market-forecast-to-grow-ridesharing-presence (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Future of Autonomous Vehicles [2026–2035]. Available online: https://www.startus-insights.com/innovators-guide/future-of-autonomous-vehicles/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Abassi, R.; Sauveron, D. State-of-the-art survey of in-vehicle protocols and automotive Ethernet security and vulnerabilities. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 17057–17095. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, M.S.; Liang, J. A comprehensive survey on VANET security services in traffic management system. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2019, 1, 2423915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangar, M.N.; Ahmed, Q.Z.; Khan, F.A.; Hafeez, M. A survey of autonomous vehicles: Enabling communication technologies and challenges. Sensors 2021, 21, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlik, I.; Miller, T.; Kostecka, E.; Zwierzewicz, Z.; Łobodzińska, A. Cybersecurity in autonomous vehicles—Are we ready for the challenge? Electronics 2024, 13, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, J.S.; Jeong, S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, H.K. Cybersecurity for autonomous vehicles: Review of attacks and defense. Comput. Secur. 2021, 103, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Kato, N. Networking and communications in autonomous driving: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 21, 1243–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathla, G.; Bhadane, K.; Singh, R.K.; Kumar, R.; Aluvalu, R.; Krishnamurthi, R.; Kumar, A.; Thakur, R.N.; Basheer, S. Autonomous Vehicles and Intelligent Automation: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 1, 7632892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Yang, L. Artificial intelligence applications in the development of autonomous vehicles: A Survey. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2020, 7, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M. AI in autonomous vehicles: State-of-the-art and future directions. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Innov. 2024, 2, 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, D.; Poddar, N.; Rajpurkar, A.; Chahal, M.; Kumar, N.; Joshi, G.P.; Cho, W. A review on autonomous vehicles: Progress, methods and challenges. Electronics 2022, 11, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lu, S.; Zhong, R.; Wu, B.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, W. Computing systems for autonomous driving: State of the art and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 6469–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, O.; Sahoo, N.C.; Puhan, N.B. Recent advances in motion and behavior planning techniques for software architecture of autonomous vehicles: A state-of-the-art survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 101, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Q. Architecture design and implementation of an autonomous vehicle. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 21956–21970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarting, W.; Alonso-Mora, J.; Rus, D. Planning and decision-making for autonomous vehicles. Annu. Rev. Control. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2018, 1, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famularo, D.; Fortino, G.; Pupo, F.; Giannini, F.; Franze, G. An intelligent multi-layer control architecture for logistics operations of autonomous vehicles in manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 7296–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Maple, C.; Passerone, R. An investigation of cyber-attacks and security mechanisms for connected and autonomous vehicles. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 90641–90669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, G.; Elgazzar, K.; Khamis, A. Connected vehicles: Technology review, state of the art, challenges and opportunities. Sensors 2021, 21, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianey, H.K.; Ali, M.; Vijayakumar, V.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, R. Low cost and centimeter-level global positioning system accuracy using real-time kinematic library and real-time kinematic GPSA. Recent Patents Comput. Sci. 2021, 14, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.F.; Elvik, R.; Johnsson, E. Risk Analysis for Forecasting Cyberattacks against Connected and Autonomous Vehicles. J. Transp. Secur. 2021, 14, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, E.E.; Aloqaily, A.; Fayez, H. Identifying intrusion attempts on connected and autonomous vehicles: A survey. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 220, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Mishra, A.K. Enhanced Machine Learning Framework for DDoS Attack Endurance in Vehicles Security for 5G Networks. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Communication, Security, and Artificial Intelligence (ICCSAI), Greater Noida, India, 4–6 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, S.; Goyal, S.; Bhandari, A. A lightweight blockchain based scalable and collaborative mitigation framework against new flow DDoS attacks in SDN enabled autonomous systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbar, B. Detection of Blackhole and DDoS Attack in 5g VANET Using Multiple Machine Learning Algorithms. Ph.D. Thesis, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Chen, Y.C. Real-time ddos detection and alleviation in software-defined in-vehicle networks. IEEE Sensors Letters 2022, 6, 6003304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, R.T.; Iqbal, M.D. Hybrid AI for Securing Intelligent Transportation: Real-Time DDoS Detection in VANETs. Int. J. Eng. Dev. Res. 2025, 13, 370–397. [Google Scholar]

- Yeasmin, S.; Haque, A. DDoS Attack Prevention in Autonomous Vehicle’s OTA Updates: Combining PBFT Consensus and Distributed Firewall in Hyperledger Fabric Blockchain. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), Ayia Napa, Cyprus, 27–31 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bousalem, B.; Silva, V.F.; Bakhouche, S.B.; Langar, R.; Cherrier, S. Detecting and mitigating DDoS attacks in 5G-V2X networks: A deep learning-based approach. In Proceedings of the Global Information Infrastructure and Networking Symposium (GIIS), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 25–27 February 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Aloraini, F.; Javed, A.; Rana, O. Adversarial attacks on intrusion detection systems in in-vehicle networks of connected and autonomous vehicles. Sensors 2024, 24, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biron, Z.A.; Dey, S.; Pisu, P. Real-time detection and estimation of denial of service attack in connected vehicle systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 3893–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onur, F.; Barışkan, M.A.; Gönen, S.; Kubat, C.; Tunay, M.; Yılmaz, E.N. Detection of cyber attacks targeting autonomous vehicles using machine learning. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Intelligent Manufacturing and Service Systems, Istanbul, Turkey, 26–28 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Mehmood, A.; Song, H.; Maple, C. A decentralized, secure, and reliable vehicle platoon formation with privacy protection for autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 6441–6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research from Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity. Available online: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ddos-2019.html (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Swati, J.; Nitin, P.; Singh, S.; Sinha, A.; Sirvi, V.; Srivastava, S. DDoS Attack Detection Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology, Singapore, 16–18 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aktar, S.; Nur, A.Y. Towards DDoS attack detection using deep learning approach. Comput. Secur. 2023, 129, 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Pateriya, R.K.; Gupta, R.K.; Dehalwar, V.; Sharma, A. DDoS detection using deep learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 218, 2420–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghazzawi, D.; Bamasag, O.; Ullah, H.; Asghar, M.Z. Efficient detection of DDoS attacks using a hybrid deep learning model with improved feature selection. Appl. Sci. 2023, 11, 11634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinello, D.; Genovese, A.; Piuri, V. Anomaly based intrusion detection system for DDoS attack with deep learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Security and Cryptography, Rome, Italy, 10–12 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Türkoğlu, M.; Polat, H.; Koçak, C.; Polat, O. Recognition of DDoS attacks on SD-VANET based on combination of hyperparameter optimization and feature selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 203, 117500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.