A Lightweight, End-to-End Encrypted Data Pipeline for IIoT: An AES-GCM Implementation for ESP32, MQTT, and Raspberry Pi

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. MQTT in IIoT: Operational Constraints and Security Limitations

1.2. Related Work: Lightweight Cryptography and Application-Layer Protection

1.3. Research Gap and Contributions

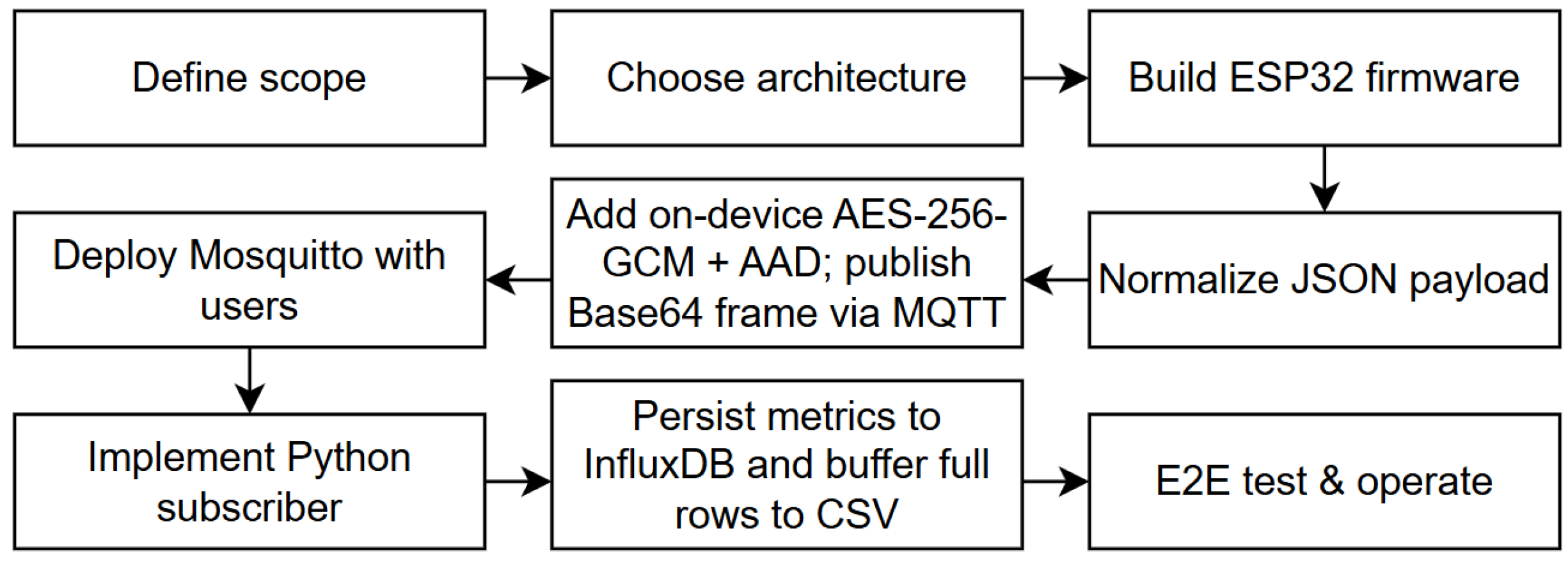

2. Materials and Methods

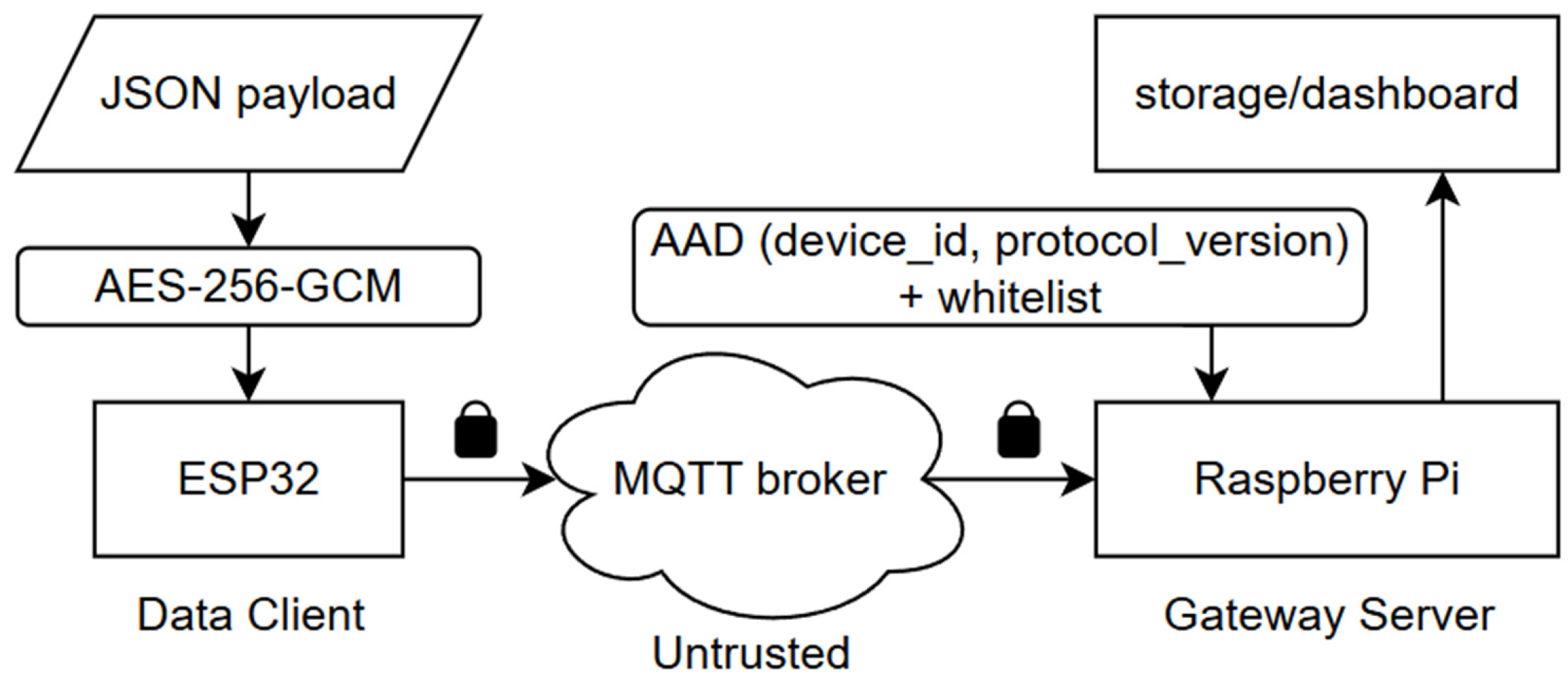

2.1. System Architecture

2.2. Hardware and Software Stack

2.3. Secure Data Protocol Design

2.3.1. Plaintext Payload and AAD

2.3.2. Cryptographic Parameters and Design Rationale

2.3.3. Encryption Frame on ESP32 (C++/mbedTLS)

2.3.4. Decryption Frame on Raspberry Pi (Python/PyCryptodome)

2.3.5. Nonce Management, Reboot Behavior, and Replay Considerations

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Experimental Design and Benchmark Scenarios

3. Results

3.1. ESP32 Packet-Preparation Latency

3.2. Security and Integrity Validation

3.3. End-to-End Throughput and Reliability

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Contribution Beyond TLS-Only MQTT

4.2. Comparison with Lightweight AEAD and Object-Security Approaches

4.3. Security Beyond Broker Compromise: Replay, DoS, and Side Channels

4.4. Key Management, Provisioning, Rotation, and Revocation at Scale

4.5. Complementary Defenses: IDS and Anomaly Detection

4.6. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cruz, C.; Palomar, E.; Bravo, I.; Gardel, A. Cooperative Demand Response Framework for a Smart Community Targeting Renewables: Testbed Implementation and Performance Evaluation. Energies 2020, 13, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, V.A.S.; de Araújo, H.P.; Penteado, C.G.; Gazziro, M.; Carmo, J.P. Low-Cost Embedded System Applications for Smart Cities. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, S.; Borrero, E.R.; Zauner, J.; Hanshans, C. Development and Implementation of an Open Source IoT Platform, Network and Data Warehouse for Privacy-Compliant Applications in Research and Industry. Curr. Dir. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 7, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-H.; Wu, S.-H.; Huang, B.-W.; Chen, P.-H.; Huang, C.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Yang, C.-F. Node-RED Web-based Monitor and Control of Power System Using Modbus and Message Queuing Telemetry Transport Communication in Raspberry Pi Embedded Platform. Sens. Mater. 2024, 36, 4849–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jornet-Monteverde, J.A.; Galiana-Merino, J.J. Low-Cost Conversion of Single-Zone HVAC Systems to Multi-Zone Control Systems Using Low-Power Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouillard, J.; Vannobel, J.-M. Multimodal Interaction for Cobot Using MQTT. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Jiao, T.; Li, Z. Innovative Applications of IoT in Smart Home Systems: Enhancing Environmental Monitoring with Integrated Sensor Technologies and MQTT Protocol. JoWUA 2024, 15, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Gamess, E. A Study of the Resilience of the Mosquitto MQTT Broker Running on Raspberry Pi Against Fuzzy DDoS Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2024 Latin America Networking Conference, Bahia Blanca, Argentina, 15–16 August 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikii, D. Denial-of-Service Attack Analysis by MQTT Protocol. Sci. Tech. J. Inf. Technol. Mech. Opt. 2020, 20, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, T.N.; Gamess, E.; Ogden, C. Performance Evaluation of Different Raspberry Pi Models as MQTT Servers and Clients. IJCNC 2022, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, A.F.; Macrì, D.; Carnì, D.L.; Greco, E.; Lamonaca, F. A Performance Analysis of Security Protocols for Distributed Measurement Systems Based on IoT with Constrained Hardware and Open Source Infrastructures. Sensors 2024, 24, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilidis, N.O.; Halkidis, S.T.; Petridou, S. Empirical Evaluation of TLS-Enhanced MQTT on IoT Devices for V2X Use Cases. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.; Pinheiro, L.; Santos, V.; Salgado, B. PlugID: A Platform for Authenticated Energy Consumption to Enhance Accountability and Efficiency in Smart Buildings. Energies 2025, 18, 5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Gutiérrez, C.A.; Delgado-Del-Carpio, M.; Zebadúa-Chavarría, L.A.; Hernández-De-León, H.R.; Escobar-Gómez, E.N.; Quevedo-López, M. IoT-Enabled System for Detection, Monitoring, and Tracking of Nuclear Materials. Electronics 2023, 12, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Fernández, O.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; de la Fraga, L.G.; Sandoval-Ibarra, Y.; Nuñez-Perez, J.-C. An Image Encryption Scheme Synchronizing Optimized Chaotic Systems Implemented on Raspberry Pis. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Hou, T.-Y.; Yu, C.-C. Information Security in Wireless Water Flow and Leakage Alarm System. Sens. Mater. 2022, 34, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Sun, J. Developing Real-Time IoT-Based Public Safety Alert and Emergency Response Systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, G.R.; Rojas-Cortés, J.E.; Cuaya-Simbro, G.; Simón-Marmolejo, I. Fleet Control with IoT Using TLS Certificates and SIM7000G GPS Device. J. Appl. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2024, 6, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Cunha, V.A.; Barraca, J.P.; Aguiar, R.L. Analysis of the Cryptographic Algorithms in IoT Communications. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 26, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hajj, M.; Gebremariam, T.H. Enhancing Resilience in Digital Twins: ASCON-Based Security Solutions for Industry 4.0. Network 2024, 4, 260–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasa Laborda, V.; Hernández-Álvarez, L.; Hernández Encinas, L.; Sánchez García, J.I.; Queiruga-Dios, A. Study About the Performance of Ascon in Arduino Devices. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.S.; Al-Awamry, A.A.; Taha, A. Tailoring AES for Resource-Constrained IoT Devices. Indones. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 36, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, H.Y.; Mattar, A.K.; Saare, M.A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Shehab, R. A Comparison of Lightweight Cryptographic Protocols for Energy-Efficient and Sustainable IoMT Authentication. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2025, 15, 25746–25756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shete, R.P.; Bongale, A.M.; Dharrao, D. Lightweight Cryptographic and Scalable IoT Systems for Encryption across GSM-MQTT Architectures in Resource-Constrained Aquaculture Environment. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2025, 15, 25133–25139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, N.; Alnemer, S.; Alshuhail, L.M.; Alobiad, H.; Almulla, T.; Alrumaihi, F.A.; Ghadra, N.; Nagy, M. Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Performance Measurements. Sci 2025, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrya, G.B.; Agus, Y.M.; Ben Mnaouer, A. A Comparative Study of Post-Quantum Cryptographic Algorithm Implementations for Secure and Efficient Energy Systems Monitoring. Electronics 2023, 12, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.H.; Qamar, A.; Khan, R.; Alturise, F.; Alshaabani, A.R.; Alkhalaf, S. Secure Edge-Based IoMT Framework for ICU Monitoring with TinyML and Post-Quantum Cryptography. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, P.; Kamble, D.P.; Singh, I. Hybrid Cryptographic Approach for Strengthening IoT and 5G/B5G Network Security. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk, G.; Çimen, M.E.; Çavuşoğlu, Ü.; Eldoğan, O.; Karayel, D. Secure and Efficient Data Encryption for Internet of Robotic Things via Chaos-Based Ascon. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A J, B.; Kaythry, P. Secure IoV Communications for Smart Fleet Systems Empowered with ASCON. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannaboon, C.; Ridzwan, S.A.B.S.; Fong-In, S. Chaotic Compressed Sensing for Secure Image Transmission in LoRa IoT Systems. IJACSA 2025, 16, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.A.; Shujaa, M.I. DNA Computing-Based Stream Cipher for Internet of Things Using MQTT Protocol. IJECE 2020, 10, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seedorf, J.; Rawal, D.; Hamann, M.; Seid, S.; Schneider, K.; Anh, V.D.; Haag, M.; Milla, F.; Altun, Y.E. On-Sensor Stream Cipher Encryption for Protecting Smart City Sensor Data Directly on Resource-Constrained IoT Sensors. ISPRS Arch. 2025, 48, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, B.; Luo, L.; Zou, C.; Crain, J.; Jin, Y.; Fu, X. Building a Low-Cost and State-of-the-Art IoT Security Hands-On Laboratory. In Proceedings of the Second IFIP International Cross-Domain Conference, IFIPIoT 2019, Tampa, FL, USA, 31 October–1 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala-Laurinaho, R.; Autiosalo, J.; Tammi, K. Open Sensor Manager for IIoT. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2020, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A.F.; Blokhin, I.; Anguita, M.; Ortega, J.; Escobar, J.J. Multiprotocol Authentication Device for HPC and Cloud Environments Based on Elliptic Curve Cryptography. Electronics 2020, 9, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microchip Technology Inc. AVR-IoT WG Development Board User Guide; Microchip Technology Inc.: Chandler, AZ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalah, R.W.; Abdulateef, O.F.; Hamad, A.H. A Centralized Federated Learning Algorithm Based Multi Classification Predictive Maintenance in IIoT System. J. Eur. Systèmes Autom. 2025, 58, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmiya, K.; Anitha, V. A Context-Aware IoT and Edge Computing Framework for Wireless Plant Disease Diagnosis Using Compressed MaskRCNN and ResNet-50. JoWUA 2025, 16, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T. A Deep Learning-Based Gunshot Detection IoT System with Enhanced Security Features and Testing Using Blank Guns. IoT 2025, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafuerte, N.; Manzano, S.; Ayala, P.; García, M.V. Artificial Intelligence in Virtual Telemedicine Triage: A Respiratory Infection Diagnosis Tool with Electronic Measuring Device. Future Internet 2023, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Side, G.N.; Putra, G.M.D.; Setiawati, D.A. IoT Microclimate Monitoring System Using Node-RED Platform at Plant Factory. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebti, M.R.; Dakhia, Z.; Carabetta, S.; Di Sanzo, R.; Russo, M.; Merenda, M. Real-Time Classification of Ochratoxin A Contamination in Grapes Using AI-Enhanced IoT. Sensors 2025, 25, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, G.; Coelho, T.; Mota, A.; Briga-Sá, A.; Valente, A. Smart Matter-Enabled Air Vents for Trombe Wall Automation and Control. Electronics 2025, 14, 3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Nazir, S.; Khan, H.U. Smart Object Detection and Home Appliances Control System in Smart Cities. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 67, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salikhov, R.B.; Abdrakhmanov, V.K.; Safargalin, I.N. Internet of Things (IoT) Security Alarms on ESP32-CAM. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2096, 012109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.A.; Shujaa, M.I. Secure Vehicle-to-Vehicle Voice Chat Based on MQTT and CoAP IoT Protocol. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2020, 19, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.A.; Chowdhury, O.; Hossain, M.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Muhammad, G.; AlQahtani, S.A.; Alrashoud, M.; Yassine, A.; Hossain, M.S. IoT-Based Medical Image Monitoring System Using HL7 in a Hospital Database. Healthcare 2023, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serepas, F.; Papias, I.; Christakis, K.; Dimitropoulos, N.; Marinakis, V. Lightweight Embedded IoT Gateway for Smart Homes Based on an ESP32 Microcontroller. Computers 2025, 14, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcenegui, J.; Arjona, R.; Román, R.; Baturone, I. Secure Combination of IoT and Blockchain by Physically Binding IoT Devices to Smart NFTs Using PUFs. Sensors 2021, 21, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atanov, S.; Seitkulov, Y.; Moldamurat, K.; Yergaliyeva, B.; Kyzyrkanov, A.; Seitbattalov, Z. About One Lightweight Encryption Algorithm Ensuring the Security of Data Transmission and Communication Between IoT Devices. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 14, 6861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Surpur, A.; Das, B.P.; Manhas, S. A Unified Approach to a Secure and Lightweight Mutual Authentication Protocol Using Pre-Characterized COTS SRAM ICs for IoT Applications. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2025, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.; Araiza, J.C.; Pozos, D.; Bonilla, E.; Hernández, J.C.; Cortes, J.A. Application for Functionality and Registration in the Cloud of a Microcontroller Development Board for IoT in AWS. Appl. Comput. Sci. 2021, 17, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.-C.; Lee, G.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Lin, Q.-Y. Design and Implementation of Nursing-Secure-Care System with mmWave Radar by YOLO-v4. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiteurtragool, N.; Samkunta, J.; Ketthong, P. Lightweight Parabola Chaotic Keyed Hash Using SRAM-PUF for IoT Authentication. IJACSA 2025, 16, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Laila, D. Responsive Machine Learning Framework and Lightweight Utensil of Prevention of Evasion Attacks in the IoT-Based IDS. STAP J. Secur. Risk Manag. 2025, 2025, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. Digital-Output Relative Humidity & Temperature Sensor/Module DHT22 (AM2302); Aosong Electronics Co., Ltd.: Guangzhou, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thota, Y.R.; Nixon, J.S.; Chandran, B.; Nikoubin, T. TinyML-Based Biometric Authentication Using PPG Signals for Edge Devices. In Proceedings of the Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI 2025, New Orleans, LA, USA, 30 June–2 July 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercog, D.; Sedonja, D.; Recek, B.; Truntič, M.; Gergič, B. Smart Home Solutions Using Wi-Fi-Based Hardware. Teh. Vjesn. 2020, 27, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Avg Latency (ms) | Min (ms) | Max (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| JSON serialization | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| AES-GCM encrypt + tag | 29.5 | 27.0 | 32.0 |

| Base64 encoding | 11.2 | 10.0 | 13.0 |

| Total (measured) | 41.754 |

| Scenario | Example Log Line |

|---|---|

| Valid message | 2025-11-14 14:22:11,184—INFO—[ESP32_Dala_Meter_001989] зaпиcь в InfluxDB—OK (write to InfluxDB—OK) |

| Tampered frame | 2025-11-14 14:22:16,321—ERROR—Oшибкa pacшиφpoвки/вaлидaции кaдpa: AES-GCM decrypt/verify failed: MAC check failed (decrypt/verify failed: MAC check failed) |

| Unauthorized device | 2025-11-14 14:22:21,907—WARNING—Device ‘ESP32_Test_9999’ нe в devices.txt—cooбщeниe пpoигнopиpoвaнo. (device not in whitelist—message ignored) |

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total messages sent | 720 |

| Successfully stored | 718 |

| Packet success rate (%) | 99.72 |

| Approach | Typical Strengths | Typical Constraints | Example Works |

|---|---|---|---|

| AES-GCM (application-layer AEAD) | Mature standard; strong integrity; broad library support across C/C++ and Python; interoperable framing | Requires strict nonce uniqueness; performance may be heavier than some lightweight AEADs | This work; algorithm evaluations in [19,22] |

| ASCON/lightweight AEAD | Designed for lightweight profiles; can outperform AES-GCM on some embedded targets | Not always available in standard embedded stacks; interoperability/tooling less uniform | [20,21,29,30] |

| TLS-secured MQTT (channel security) | Strong channel protection; operationally familiar | Broker still sees plaintext; handshake/CPU/energy overhead can be significant; broker compromise remains critical | [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] |

| Domain-specific stream ciphers/specialized payload encryption | Can be lightweight and on-sensor; payload protected independent of channel | Often domain-specific; may reduce interoperability; still needs key/nonce discipline | [32,33] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Amirkhanova, G.; Ismailov, S.; Amirkhanov, A.; Adilzhanova, S.; Zhasuzakova, M.; Chen, S. A Lightweight, End-to-End Encrypted Data Pipeline for IIoT: An AES-GCM Implementation for ESP32, MQTT, and Raspberry Pi. Information 2026, 17, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010033

Amirkhanova G, Ismailov S, Amirkhanov A, Adilzhanova S, Zhasuzakova M, Chen S. A Lightweight, End-to-End Encrypted Data Pipeline for IIoT: An AES-GCM Implementation for ESP32, MQTT, and Raspberry Pi. Information. 2026; 17(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmirkhanova, Gulshat, Syrym Ismailov, Alikhan Amirkhanov, Saltanat Adilzhanova, Meiramkul Zhasuzakova, and Siming Chen. 2026. "A Lightweight, End-to-End Encrypted Data Pipeline for IIoT: An AES-GCM Implementation for ESP32, MQTT, and Raspberry Pi" Information 17, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010033

APA StyleAmirkhanova, G., Ismailov, S., Amirkhanov, A., Adilzhanova, S., Zhasuzakova, M., & Chen, S. (2026). A Lightweight, End-to-End Encrypted Data Pipeline for IIoT: An AES-GCM Implementation for ESP32, MQTT, and Raspberry Pi. Information, 17(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010033