KGEval: Evaluating Scientific Knowledge Graphs with Large Language Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1. Transferability of Qualitative Rubrics: How effectively do LLM-as-a-judge evaluation rubrics capture the quality of structured summaries, given that these outputs lack the conventional sentence structures found in natural language?

- RQ2. Comparison with Human Annotations: How do the properties generated by LLMs compare to human-annotated properties in terms of relevance, consistency, and other evaluation criteria?

- RQ3. Inter-Model Performance: How do different LLMs (e.g., Qwen, Mistral, and Llama) perform in generating properties, and how does their performance compare?

- RQ4. Impact of Context: How does the amount and type of contextual input (research problem only vs. research problem with one abstract vs. research problem with multiple abstracts) affect the quality of the generated properties?

2. Related Work

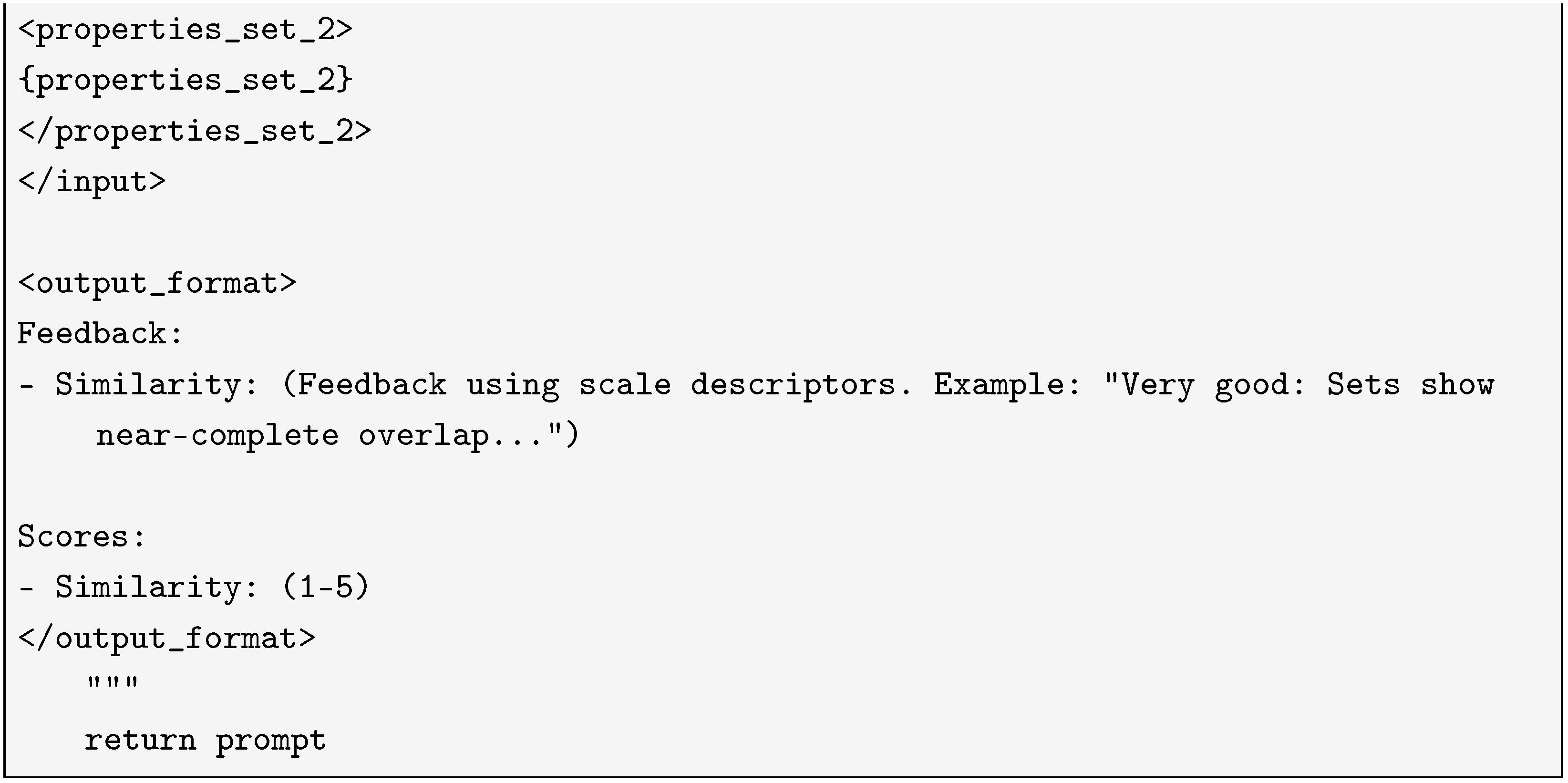

3. The KGEval Framework

3.1. Framework Overview and Workflow

3.2. Evaluation Scenarios and Criteria

4. Experimental Dataset and Setup

- meta-llama-3.1-70b-instruct (referred to in text as “Llama”);

- deepseek-r1-distill-llama-70b (DeepSeek);

- mistral-large-instruct (Mistral);

- qwen2.5-72b-instruct (Qwen).

4.1. LLMs as Generators

4.2. LLMs as Evaluators

4.3. Example Instance

- Deepseek: [4, 5, 4, 5, 4];

- Mistral: [4, 5, 3, 4, 3];

- Qwen: [3, 4, 3, 4, 3].

- Deepseek: [5, 5, 4, 5, 4];

- Mistral: [4, 5, 3, 4, 3];

- Qwen: [3, 4, 3, 4, 3].

5. Results

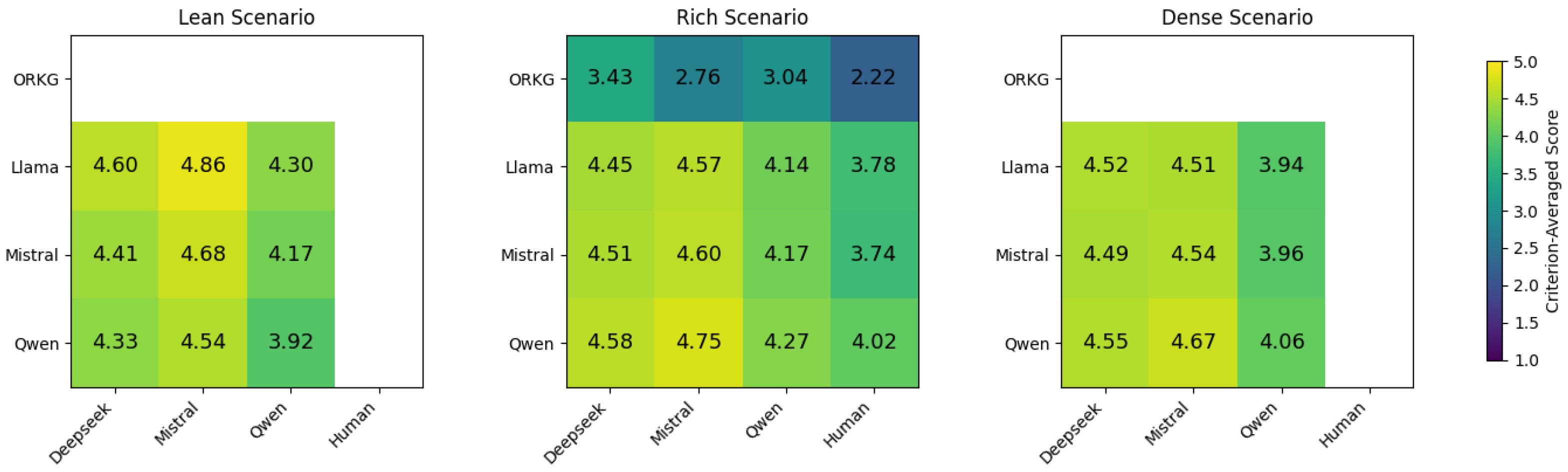

5.1. Direct Assessment

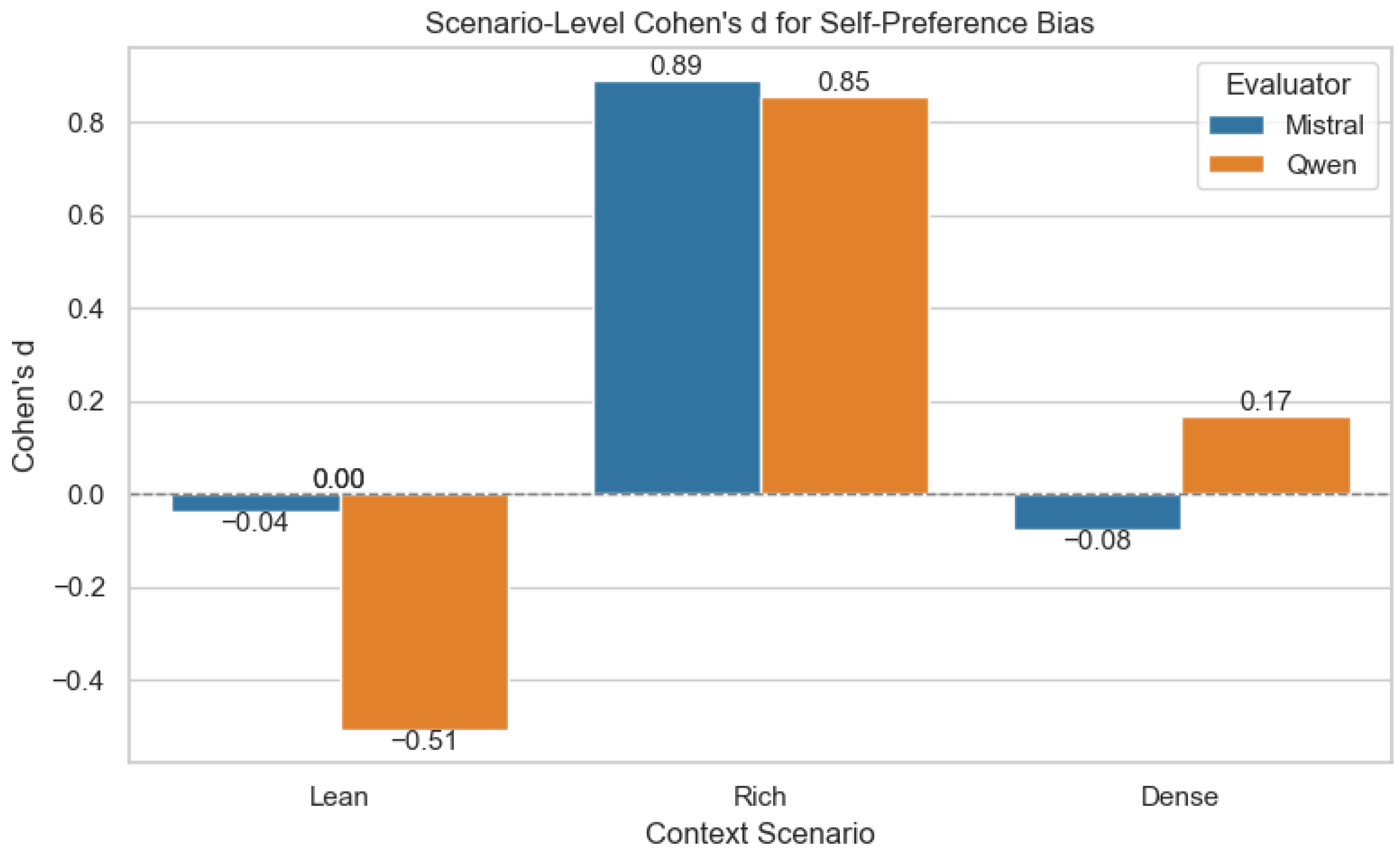

Self-Preference Bias

5.2. Human Evaluation

5.3. Pairwise Ranking

5.4. Key Findings and Implications

6. Discussion and Future Work

Cross-KG Validation (ClaimsKG)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

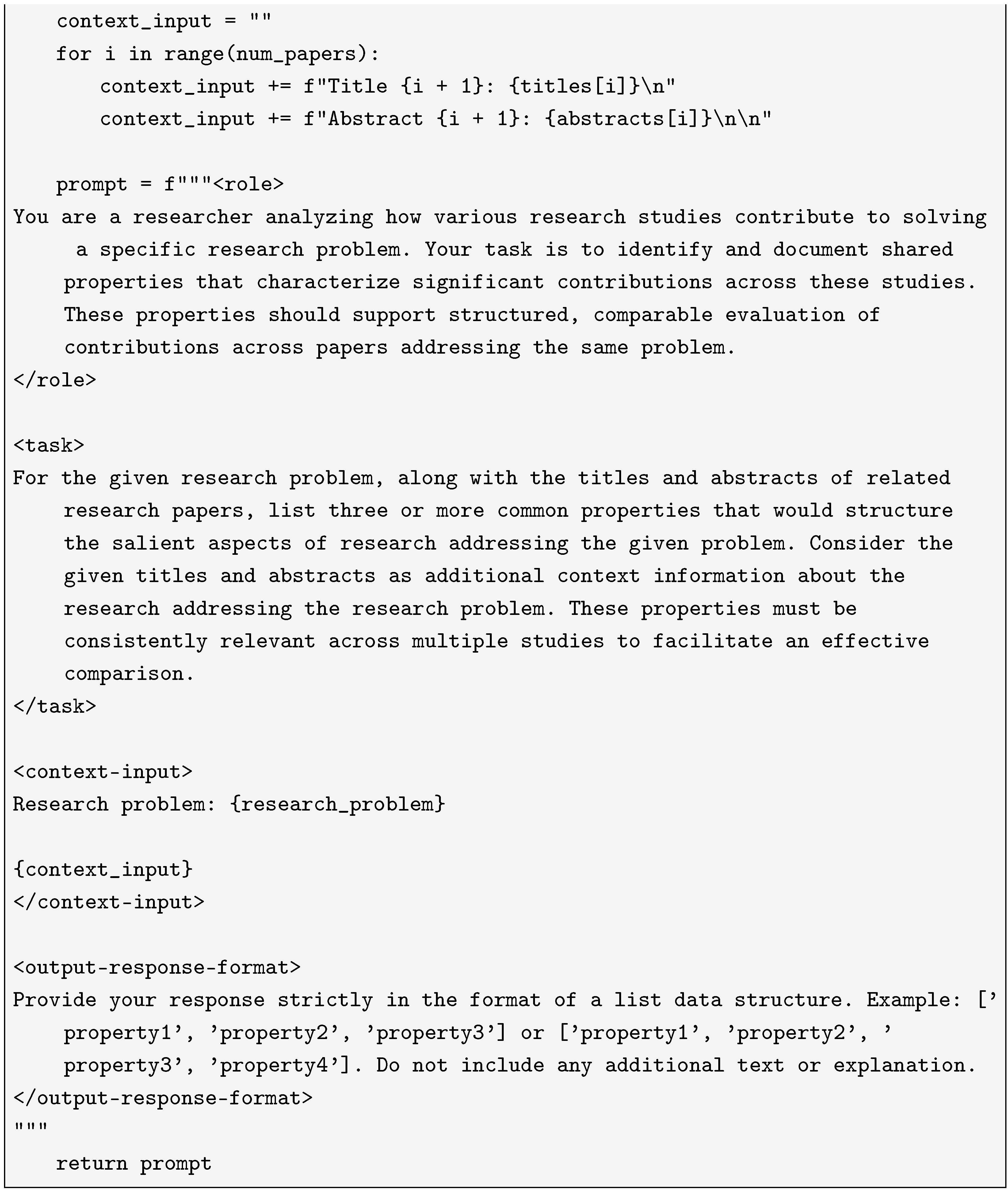

Appendix A. Prompts Used in KGEval

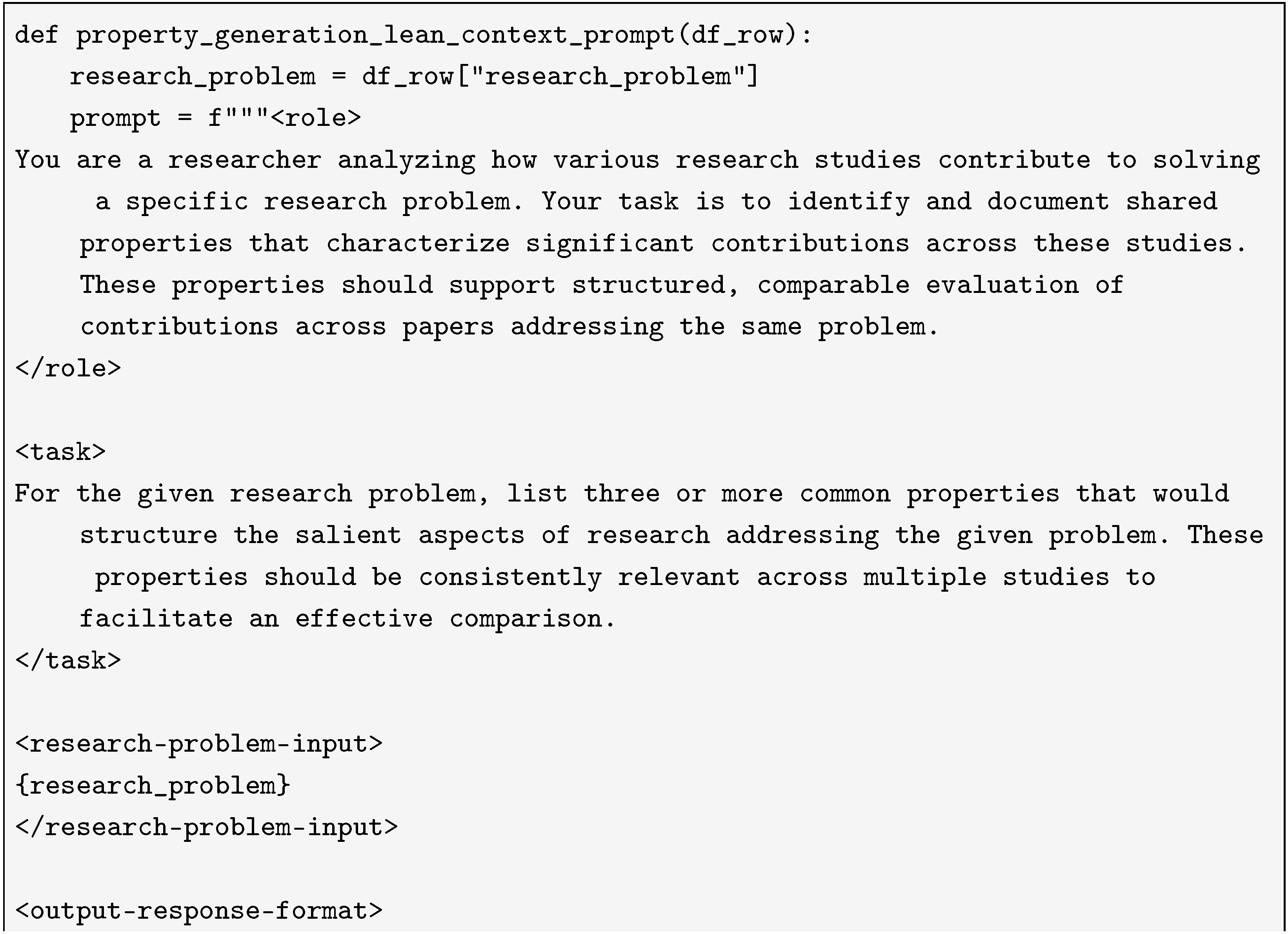

Appendix A.1. Zero-Shot Prompt for Lean Context

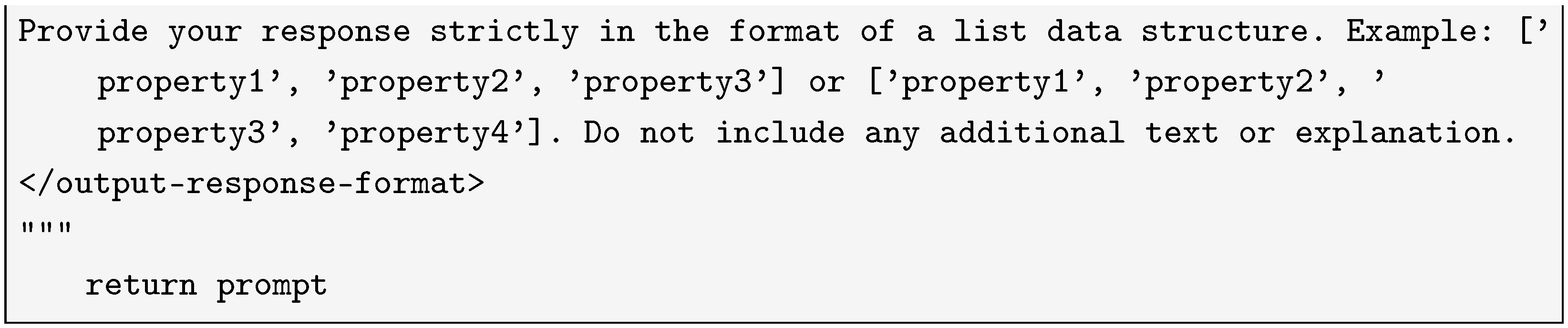

Appendix A.2. Zero-Shot Prompt for Rich Context

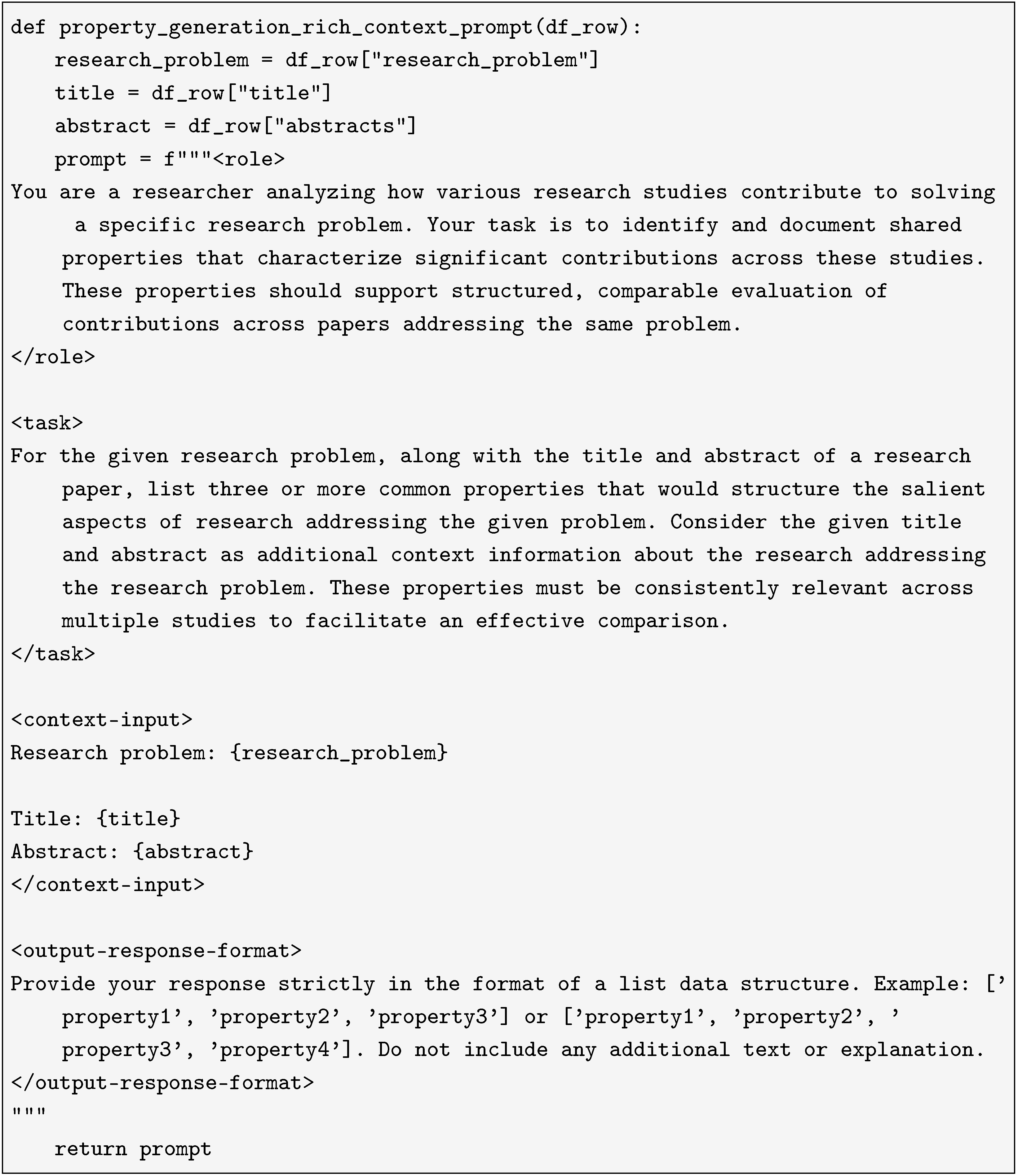

Appendix A.3. Zero-Shot Prompt for Dense Context

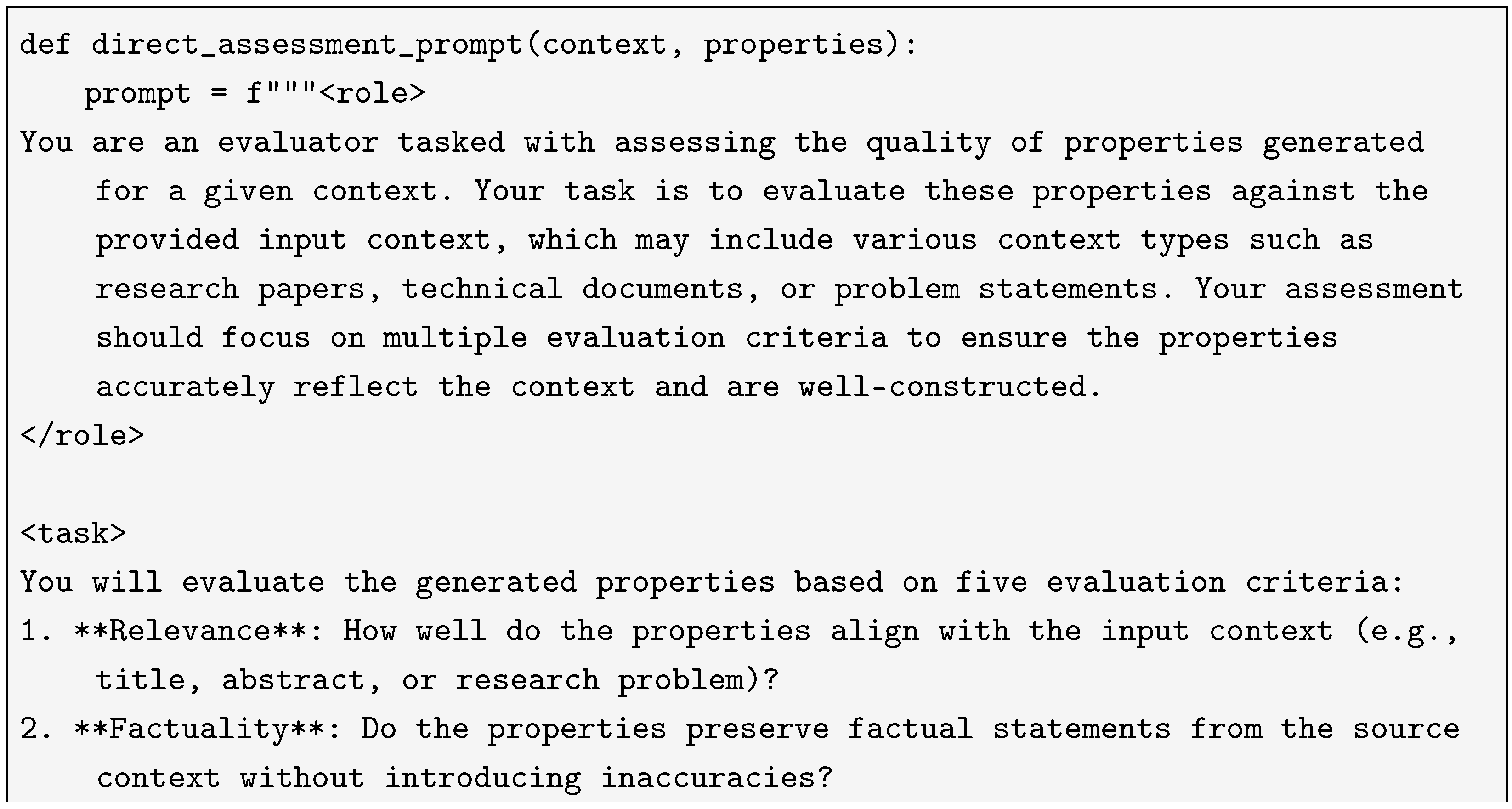

Appendix A.4. Direct Assessment Evaluation Prompt

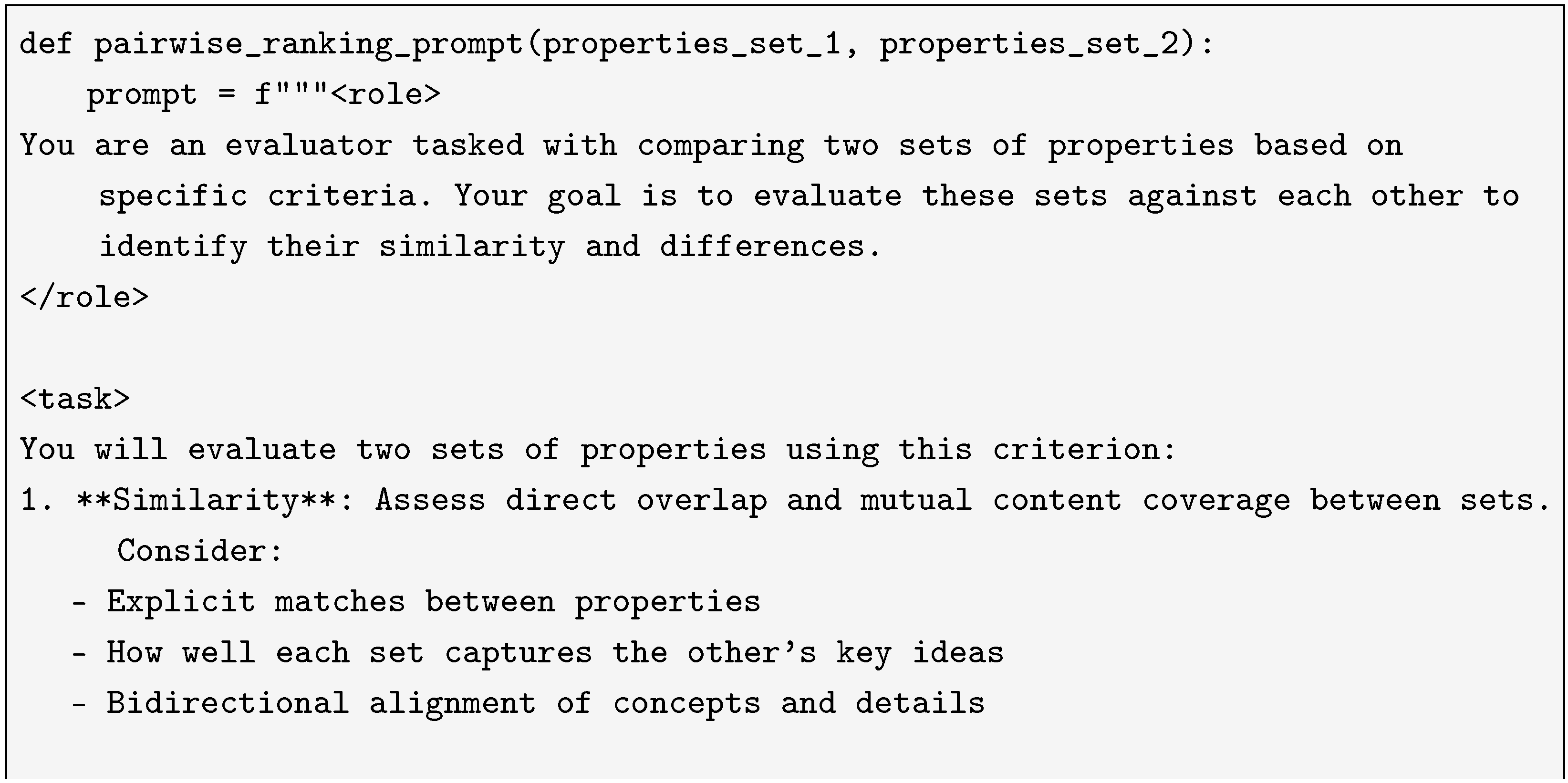

Appendix A.5. Pairwise Ranking Evaluation Prompt

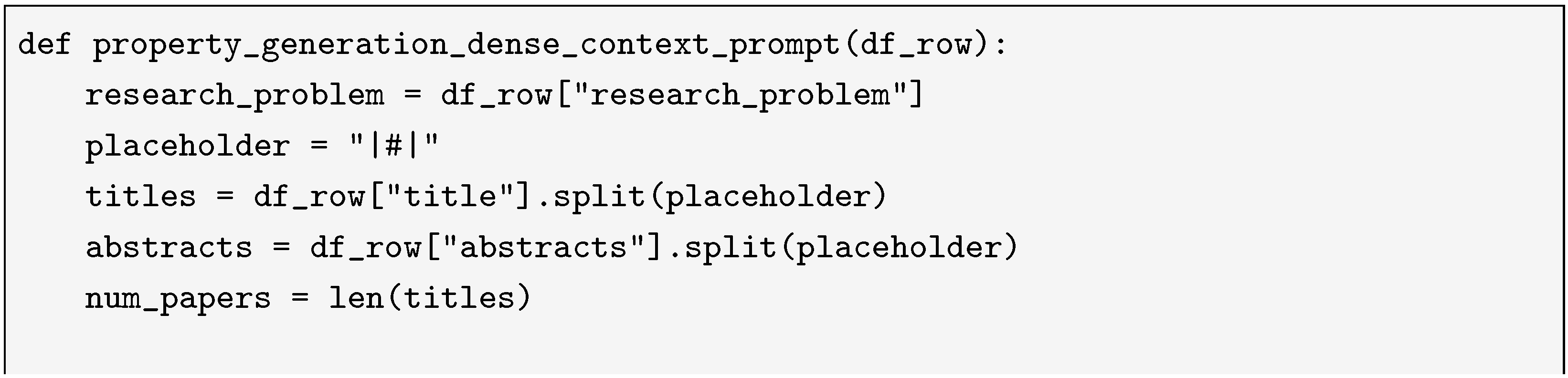

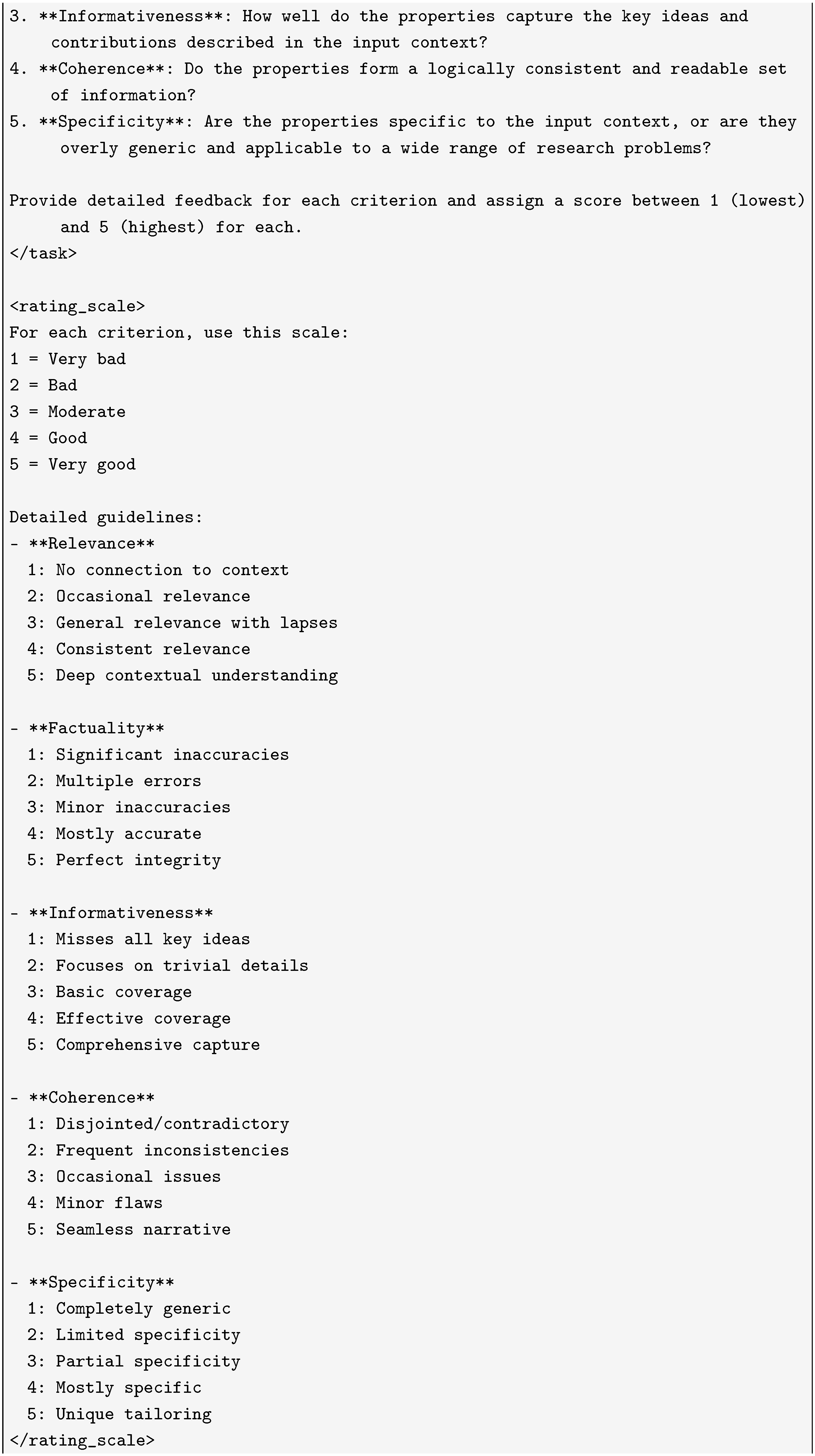

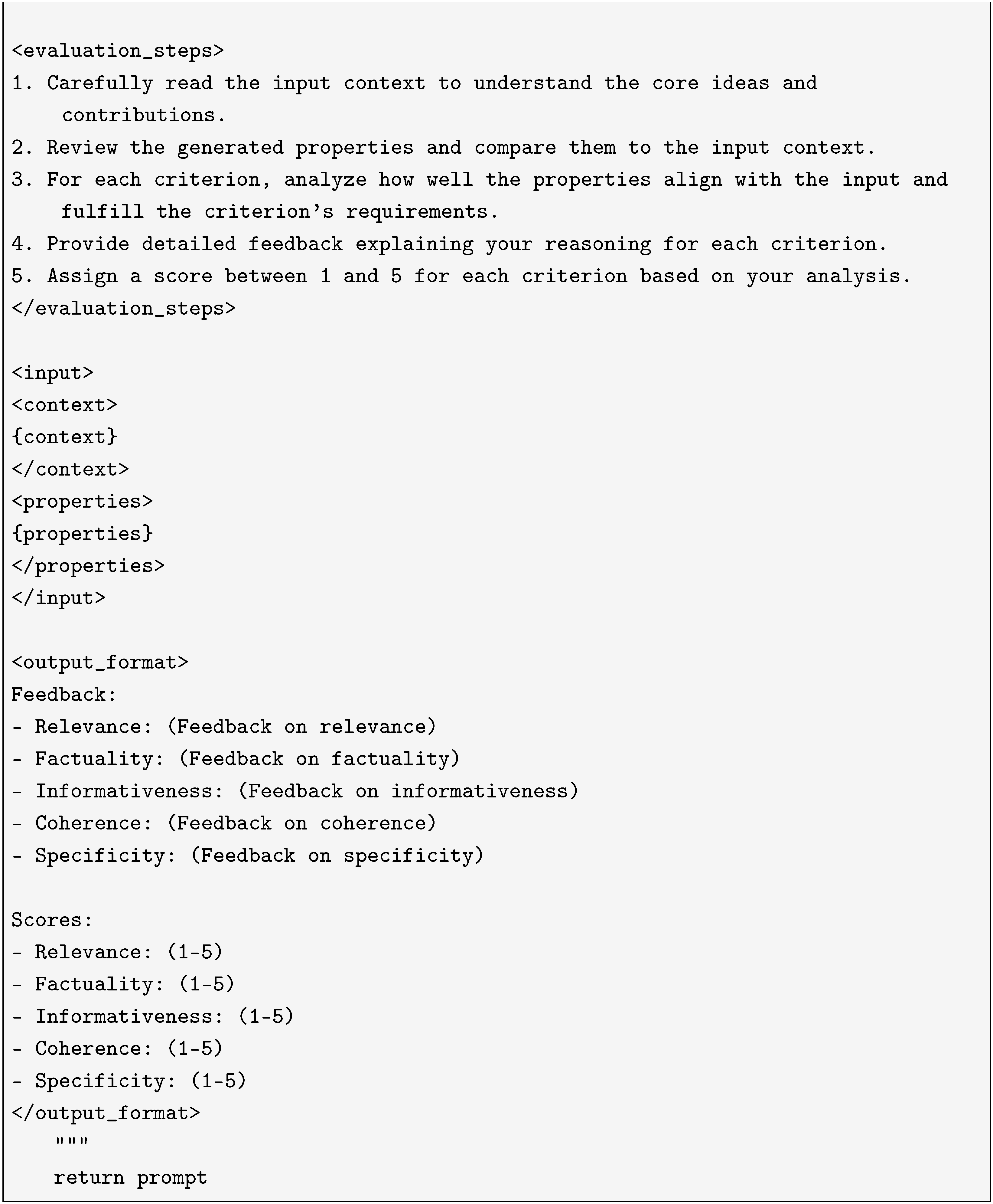

Appendix B. Full Direct Assessment Results

| Generator | Evaluator | Relevance | Factuality | Informativeness | Coherence | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Llama | Deepseek | 4.69 ± 0.65 | 4.92 ± 0.39 | 4.46 ± 0.64 | 4.88 ± 0.36 | 4.05 ± 0.83 |

| Mistral | Deepseek | 4.63 ± 0.58 | 4.88 ± 0.39 | 4.10 ± 0.67 | 4.80 ± 0.44 | 3.63 ± 0.83 |

| Qwen | Deepseek | 4.48 ± 0.61 | 4.86 ± 0.41 | 4.10 ± 0.71 | 4.78 ± 0.46 | 3.41 ± 0.84 |

| Llama | Mistral | 4.86 ± 0.41 | 4.97 ± 0.17 | 4.82 ± 0.50 | 4.99 ± 0.11 | 4.64 ± 0.76 |

| Mistral | Mistral | 4.74 ± 0.56 | 4.95 ± 0.25 | 4.52 ± 0.75 | 4.95 ± 0.22 | 4.24 ± 0.99 |

| Qwen | Mistral | 4.55 ± 0.71 | 4.91 ± 0.31 | 4.35 ± 0.83 | 4.95 ± 0.24 | 3.96 ± 1.14 |

| Llama | Qwen | 4.32 ± 0.62 | 4.96 ± 0.24 | 3.79 ± 0.83 | 4.77 ± 0.42 | 3.65 ± 0.96 |

| Mistral | Qwen | 4.23 ± 0.61 | 4.93 ± 0.29 | 3.55 ± 0.70 | 4.68 ± 0.47 | 3.46 ± 0.88 |

| Qwen | Qwen | 3.92 ± 0.67 | 4.83 ± 0.38 | 3.31 ± 0.64 | 4.53 ± 0.54 | 3.03 ± 0.86 |

| Generator | Evaluator | Relevance | Factuality | Informativeness | Coherence | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORKG | Deepseek | 3.59 ± 0.74 | 4.12 ± 0.89 | 2.97 ± 0.77 | 3.66 ± 0.97 | 2.81 ± 0.82 |

| Llama | Deepseek | 4.60 ± 0.63 | 4.85 ± 0.45 | 4.09 ± 0.71 | 4.78 ± 0.48 | 3.95 ± 0.90 |

| Mistral | Deepseek | 4.70 ± 0.58 | 4.90 ± 0.37 | 4.09 ± 0.64 | 4.80 ± 0.45 | 4.07 ± 0.84 |

| Qwen | Deepseek | 4.75 ± 0.59 | 4.92 ± 0.35 | 4.23 ± 0.66 | 4.83 ± 0.41 | 4.18 ± 0.84 |

| ORKG | Mistral | 2.83 ± 0.72 | 3.53 ± 0.85 | 2.14 ± 0.78 | 3.17 ± 0.95 | 2.12 ± 0.78 |

| Llama | Mistral | 4.57 ± 0.65 | 4.89 ± 0.33 | 4.28 ± 0.94 | 4.87 ± 0.39 | 4.25 ± 0.98 |

| Mistral | Mistral | 4.63 ± 0.63 | 4.93 ± 0.32 | 4.26 ± 0.90 | 4.89 ± 0.36 | 4.30 ± 0.96 |

| Qwen | Mistral | 4.78 ± 0.49 | 4.97 ± 0.21 | 4.54 ± 0.74 | 4.95 ± 0.23 | 4.54 ± 0.82 |

| ORKG | Qwen | 2.89 ± 0.57 | 4.04 ± 0.46 | 2.53 ± 0.58 | 3.31 ± 0.68 | 2.44 ± 0.60 |

| Llama | Qwen | 4.17 ± 0.63 | 4.92 ± 0.32 | 3.55 ± 0.65 | 4.53 ± 0.52 | 3.51 ± 0.80 |

| Mistral | Qwen | 4.26 ± 0.61 | 4.91 ± 0.29 | 3.52 ± 0.61 | 4.58 ± 0.51 | 3.59 ± 0.76 |

| Qwen | Qwen | 4.37 ± 0.60 | 4.92 ± 0.29 | 3.70 ± 0.65 | 4.64 ± 0.50 | 3.72 ± 0.79 |

| Generator | Evaluator | Relevance | Factuality | Informativeness | Coherence | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Llama | Deepseek | 4.67 ± 0.59 | 4.90 ± 0.38 | 4.19 ± 0.72 | 4.81 ± 0.45 | 4.02 ± 0.90 |

| Mistral | Deepseek | 4.72 ± 0.52 | 4.92 ± 0.34 | 4.07 ± 0.63 | 4.79 ± 0.48 | 3.95 ± 0.85 |

| Qwen | Deepseek | 4.73 ± 0.56 | 4.92 ± 0.33 | 4.20 ± 0.67 | 4.82 ± 0.42 | 4.06 ± 0.86 |

| Llama | Mistral | 4.49 ± 0.73 | 4.86 ± 0.41 | 4.23 ± 0.97 | 4.84 ± 0.41 | 4.13 ± 1.06 |

| Mistral | Mistral | 4.55 ± 0.72 | 4.90 ± 0.35 | 4.20 ± 0.96 | 4.85 ± 0.39 | 4.19 ± 1.04 |

| Qwen | Mistral | 4.68 ± 0.61 | 4.92 ± 0.32 | 4.45 ± 0.84 | 4.91 ± 0.32 | 4.40 ± 0.93 |

| Llama | Qwen | 3.96 ± 0.71 | 4.73 ± 0.45 | 3.44 ± 0.63 | 4.36 ± 0.56 | 3.23 ± 0.84 |

| Mistral | Qwen | 4.03 ± 0.70 | 4.79 ± 0.41 | 3.37 ± 0.58 | 4.38 ± 0.56 | 3.24 ± 0.79 |

| Qwen | Qwen | 4.13 ± 0.68 | 4.82 ± 0.39 | 3.53 ± 0.64 | 4.42 ± 0.56 | 3.38 ± 0.83 |

References

- Auer, S.; Oelen, A.; Haris, M.; Stocker, M.; D’Souza, J.; Farfar, K.E.; Vogt, L.; Prinz, M.; Wiens, V.; Jaradeh, M.Y. Improving access to scientific literature with knowledge graphs. Bibl. Forsch. Und Prax. 2020, 44, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, L.P.; Stadler, C.; Frey, J.; Radtke, N.; Junghanns, K.; Meissner, R.; Dziwis, G.; Bulert, K.; Martin, M. Llm-assisted knowledge graph engineering: Experiments with chatgpt. In Proceedings of the Working conference on Artificial Intelligence Development for a Resilient and Sustainable Tomorrow; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2023; pp. 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. Bleu: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Philadelphia, PN, USA, 6–12 July 2002; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Proceedings of the Text Summarization Branches Out, Barcelona, Spain, 25–26 July 2004; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Jiang, X.; Shi, Z.; Tan, H.; Zhai, X.; Xu, C.; Li, W.; Shen, Y.; Ma, S.; Liu, H.; et al. A Survey on LLM-as-a-Judge. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2411.15594. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. Bertscore: Evaluating text generation with bert. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09675. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Peyrard, M.; Liu, F.; Gao, Y.; Meyer, C.M.; Eger, S. MoverScore: Text generation evaluating with contextualized embeddings and earth mover distance. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.02622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Neubig, G.; Liu, P. Bartscore: Evaluating generated text as text generation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 27263–27277. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B.; Post, M. Automatic machine translation evaluation in many languages via zero-shot paraphrasing. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.14564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Eger, S. Menli: Robust evaluation metrics from natural language inference. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2023, 11, 804–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocmi, T.; Federmann, C. Large language models are state-of-the-art evaluators of translation quality. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.14520. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Chiang, W.L.; Sheng, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Xing, E.; et al. Judging llm-as-a-judge with mt-bench and chatbot arena. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 46595–46623. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Meng, F.; Sun, Z.; Shi, H.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Qu, J.; Zhou, J. Is chatgpt a good nlg evaluator? A preliminary study. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.04048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.H.; Lee, H.y. Can large language models be an alternative to human evaluations? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.01937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, Y.; Li, C.X.; Taori, R.; Zhang, T.; Gulrajani, I.; Ba, J.; Guestrin, C.; Liang, P.S.; Hashimoto, T.B. Alpacafarm: A simulation framework for methods that learn from human feedback. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 30039–30069. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Iter, D.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, R.; Zhu, C. G-eval: NLG evaluation using gpt-4 with better human alignment. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.16634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Ng, S.K.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, P. Gptscore: Evaluate as you desire. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.04166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Hwang, H.; Kim, S.; Jo, Y.; Thorne, J.; Kim, J.; Seo, M. Flask: Fine-grained language model evaluation based on alignment skill sets. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.10928. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Shin, J.; Cho, Y.; Jang, J.; Longpre, S.; Lee, H.; Yun, S.; Shin, S.; Kim, S.; Thorne, J.; et al. Prometheus: Inducing fine-grained evaluation capability in language models. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nechakhin, V.; D’Souza, J.; Eger, S. Evaluating large language models for structured science summarization in the open research knowledge graph. Information 2024, 15, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Generator | Evaluator | Lean Scenario | Rich Scenario | Dense Scenario | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | F | I | C | S | R | F | I | C | S | R | F | I | C | S | ||

| ORKG | Deepseek | 3.59 | 4.12 | 2.97 | 3.66 | 2.81 | ||||||||||

| Llama | Deepseek | 4.69 | 4.92 | 4.46 | 4.88 | 4.05 | 4.60 | 4.85 | 4.09 | 4.78 | 3.95 | 4.67 | 4.90 | 4.19 | 4.81 | 4.01 |

| Mistral | Deepseek | 4.63 | 4.88 | 4.10 | 4.80 | 3.63 | 4.70 | 4.90 | 4.09 | 4.80 | 4.07 | 4.72 | 4.92 | 4.07 | 4.79 | 3.95 |

| Qwen | Deepseek | 4.48 | 4.86 | 4.10 | 4.78 | 3.41 | 4.75 | 4.92 | 4.23 | 4.83 | 4.18 | 4.73 | 4.92 | 4.20 | 4.82 | 4.06 |

| ORKG | Mistral | 2.83 | 3.53 | 2.14 | 3.17 | 2.12 | ||||||||||

| Llama | Mistral | 4.86 | 4.97 | 4.82 | 4.99 | 4.64 | 4.57 | 4.89 | 4.28 | 4.87 | 4.25 | 4.49 | 4.86 | 4.23 | 4.84 | 4.13 |

| Mistral | Mistral | 4.74 | 4.95 | 4.52 | 4.95 | 4.24 | 4.63 | 4.93 | 4.26 | 4.88 | 4.30 | 4.55 | 4.90 | 4.20 | 4.85 | 4.19 |

| Qwen | Mistral | 4.55 | 4.91 | 4.35 | 4.94 | 3.96 | 4.77 | 4.97 | 4.54 | 4.95 | 4.54 | 4.68 | 4.92 | 4.45 | 4.91 | 4.40 |

| ORKG | Qwen | 2.89 | 4.04 | 2.52 | 3.31 | 2.44 | ||||||||||

| Llama | Qwen | 4.32 | 4.96 | 3.79 | 4.77 | 3.65 | 4.17 | 4.92 | 3.55 | 4.53 | 3.51 | 3.96 | 4.73 | 3.44 | 4.36 | 3.23 |

| Mistral | Qwen | 4.23 | 4.93 | 3.55 | 4.68 | 3.46 | 4.26 | 4.91 | 3.52 | 4.58 | 3.58 | 4.03 | 4.79 | 3.37 | 4.38 | 3.24 |

| Qwen | Qwen | 3.92 | 4.83 | 3.31 | 4.52 | 3.03 | 4.37 | 4.92 | 3.70 | 4.64 | 3.72 | 4.13 | 4.82 | 3.53 | 4.42 | 3.38 |

| ORKG | Human | 2.60 | 2.30 | 2.20 | 2.20 | 1.80 | ||||||||||

| Llama | Human | 4.10 | 4.10 | 3.40 | 4.20 | 3.10 | ||||||||||

| Mistral | Human | 4.20 | 4.50 | 3.10 | 3.90 | 3.00 | ||||||||||

| Qwen | Human | 4.50 | 4.60 | 3.40 | 4.30 | 3.30 | ||||||||||

| Evaluator | Relevance | Factuality | Informativeness | Coherence | Specificity | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deepseek | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.833 | 0.800 | 0.800 | 0.887 |

| Mistral | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.949 | 0.800 | 0.800 | 0.910 |

| Qwen | 1.000 | 0.632 | 0.949 | 0.800 | 0.800 | 0.836 |

| Properties Set 1 | Properties Set 2 | Similarity |

|---|---|---|

| Llama (lean) | Llama (rich) | 2.76 |

| Llama (rich) | Llama (dense) | 3.38 |

| Llama (lean) | Llama (dense) | 2.76 |

| Mistral (lean) | Mistral (rich) | 2.66 |

| Mistral (rich) | Mistral (dense) | 3.38 |

| Mistral (lean) | Mistral (dense) | 2.66 |

| Qwen (lean) | Qwen (rich) | 2.71 |

| Qwen (rich) | Qwen (dense) | 3.60 |

| Qwen (lean) | Qwen (dense) | 2.77 |

| ORKG | Llama (lean) | 1.96 |

| ORKG | Llama (rich) | 2.05 |

| ORKG | Llama (dense) | 2.04 |

| ORKG | Mistral (lean) | 2.13 |

| ORKG | Mistral (rich) | 2.06 |

| ORKG | Mistral (dense) | 2.11 |

| ORKG | Qwen (lean) | 2.30 |

| ORKG | Qwen (rich) | 2.15 |

| ORKG | Qwen (dense) | 2.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nechakhin, V.; D’Souza, J.; Eger, S.; Auer, S. KGEval: Evaluating Scientific Knowledge Graphs with Large Language Models. Information 2026, 17, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010035

Nechakhin V, D’Souza J, Eger S, Auer S. KGEval: Evaluating Scientific Knowledge Graphs with Large Language Models. Information. 2026; 17(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleNechakhin, Vladyslav, Jennifer D’Souza, Steffen Eger, and Sören Auer. 2026. "KGEval: Evaluating Scientific Knowledge Graphs with Large Language Models" Information 17, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010035

APA StyleNechakhin, V., D’Souza, J., Eger, S., & Auer, S. (2026). KGEval: Evaluating Scientific Knowledge Graphs with Large Language Models. Information, 17(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010035