Abstract

As artificial intelligence (AI) technologies and Virtual Exchange (VE) become increasingly embedded in higher education, AI-driven digital humans have begun to feature in design-oriented virtual international workshops, providing a novel context for examining learner behaviour. This study develops a structural model to examine the links between system support, interaction processes, self-efficacy, satisfaction, and international learning intention. Specifically, it investigates how perceived AI support, system ease of use, and interaction intensity influence students’ continuous participation in international learning through the mediating roles of learning self-efficacy, interaction quality, and satisfaction. Data were collected through an online questionnaire administered to undergraduate and postgraduate students who had participated in an AI-driven digital human–supported online international design workshop, yielding 611 valid responses. Reliability and validity analyses, as well as structural equation modelling, were conducted using SPSS 22 and AMOS v.22.0. The results show that perceived AI support, system ease of use, and interaction intensity each have a significant positive effect on learning self-efficacy and interaction quality. Both self-efficacy and interaction quality, in turn, significantly enhance learning satisfaction, which subsequently increases students’ intentions for sustained participation in international learning. Overall, the findings reveal a coherent causal chain: AI-driven digital human system characteristics → learning process experience → learning satisfaction → sustained participation intention. This study demonstrates that integrating AI-driven digital humans can meaningfully improve learners’ process experiences in virtual international design workshops. The results provide empirical guidance for curriculum design, pedagogical strategies, and platform optimization in AI-supported, design-oriented virtual international learning environments.

1. Introduction

In recent years, Virtual Exchange (VE) has become a pivotal method for advancing internationalization in higher education globally. Through online platforms, VE connects students from diverse cultural and national backgrounds, enabling them to collaborate on learning tasks, share disciplinary knowledge, and engage in structured intercultural reflection [1]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, universities globally integrated VE more systematically into their curricula, thereby expanding access to global learning opportunities despite travel restrictions [2]. Within design education, VE has been widely implemented in Online International Design Workshops, where students work jointly on design problems in digitally mediated environments that transcend geographical and temporal boundaries. Such collaboration fosters intercultural communication competencies and stimulates students’ capacity for collaborative innovation [3].

Despite these pedagogical benefits, virtual international learning programmes continue to face substantial implementation challenges. Technical issues, such as network connectivity and device limitations, frequently interrupt learning processes, occasionally halting activities entirely [4]. At the learner level, participants often experience language anxiety, participation marginalization, limited technological access, unequal task coordination, and time-zone synchronization challenges [5]. From an educator’s perspective, designing suitable tasks, coordinating schedules across institutions, adapting to diverse learning contexts, and providing differentiated support increase instructional workload significantly. This strong dependence on individual instructor commitment constrains the scalability of VE and inhibits its institutionalisation [5]. AI-driven (artificial intelligence-driven) digital humans are intelligent virtual agents presented through a human-like (embodied) interface and equipped with multimodal perception, natural language understanding and generation, dialogue management, speech synthesis, and emotion/intent recognition capabilities. In educational contexts, they are often designed to serve as virtual tutors or learning companions, facilitating interaction, guidance, and personalised support [6]. Beyond generating natural language [7], they support voice-based communication [8], multimodal responses, and contextual understanding [9], enhancing the potential for immersive collaboration and hybrid learning. When learners perceive such agents as genuine social partners, their social interaction processes are activated, producing cognitive and affective benefits that sustain higher levels of learning motivation [10]. Empirical evidence further shows that AI-driven digital humans can enhance online learning engagement [11], persistence [12], and learning self-efficacy [13]. Against a backdrop of diversified career pathways and cross-sector mobility, it is therefore essential to construct an evidence-based chain—AI-driven digital human → interaction → self-efficacy → satisfaction → intention—to guide instructional decision-making and inform platform redesign for long-term development and continuous participation.

Existing research consistently highlights learning self-efficacy as a core psychological mechanism that shapes learning processes, predicts performance, and drives behavioural persistence [14]. In technology-enhanced learning contexts, uncertainty and operational complexity can heighten cognitive load and disrupt task comprehension, thereby weakening users’ self-efficacy and diminishing their intention to continue engaging with the technology. Although reducing barriers may improve learning conditions, such improvements do not necessarily contribute to enhanced self-efficacy [15]. To date, few empirical studies have examined how instructional support—particularly within design-oriented VE environments involving AI-driven digital humans—shapes students’ self-efficacy. Clarifying the underlying mechanisms, therefore, requires distinguishing between two pathways: objective forms of support and students’ subjective perceptions of that support.

Furthermore, international learning intention, conceptualised as students’ subjective plans or aspirations to participate in future international learning activities, represents a critical antecedent of actual engagement behaviour [16]. Prior studies typically explain intention formation through constructs such as satisfaction [17], perceived usefulness [18], and perceived value [19]. However, in terms of AI-enhanced, task-driven international design workshops, the pathway through which learning self-efficacy shapes international learning intention remains unexamined. In particular, it is unclear whether self-efficacy contributes to stronger intention indirectly through more positive experiences during the learning process. Thus, further exploration is needed regarding the mechanism linking self-efficacy → international learning intention, including potential mediating experiences and contextual moderators.

As AI-driven digital humans and related collaborative tools evolve rapidly in design-focused VE environments, students often struggle to assimilate and apply these technologies across multi-platform and multimodal collaborative tasks within short timeframes. This mismatch among “capability, tool, and context” can heighten operational burden and undermine learners’ participation. Against this backdrop, the present study focuses on international design workshop scenarios incorporating AI-driven digital human support. It systematically examines how process-oriented instructional support—particularly intelligent feedback and high-quality interaction—shapes learning self-efficacy and, in turn, facilitates the development and reinforcement of international learning intentions. By elucidating the mechanism through which self-efficacy influences intention, this study provides evidence-based implications for curriculum design and platform optimisation in AI-supported virtual international design workshops, ultimately promoting students’ effective learning and continuous engagement.

This study conceptualises the proposed model as a contextualised extension of traditional technology acceptance and continuance frameworks. Building on prior research, it treats the AI-driven digital human’s distinctive external factors and functional affordances as contextual antecedents that shape participants’ process experiences during virtual exchange. The model posits that interaction quality and learning self-efficacy serve as process-oriented mediators, linking these experiences to satisfaction and, ultimately, to the intention to continue participating. By integrating the functional attributes of AI-driven digital humans with the core psychological mechanisms underlying VE, the model clarifies how technological characteristics are associated with continuance intention.

2. Relevant Studies

2.1. Research on Virtual International Exchange and AI Support

2.1.1. Virtual International Exchange

Virtual Exchange, also referred to as telecollaboration or online intercultural exchange [20], denotes the sustained engagement of learner groups in online intercultural interaction and collaborative project work with partners from different cultural or geographical contexts [21,22]. Increasingly, VE has become an integral component of contemporary higher education programmes aimed at fostering global competence and internationalisation at home [23].

In recent years, VE formats have expanded significantly, and research has shifted considerably beyond its original emphasis on language learning to encompass communication and collaboration among diverse participant groups [24,25]. Extensive studies and practical implementations have been documented across a wide range of fields, including language development, intercultural communication, teacher education, business, and health sciences [24,26,27]. The focus of scholarly inquiry has gradually shifted from language pedagogy and e-twinning initiatives toward broader issues such as the development of intercultural competence, learner autonomy, and collaborative investigations [24]. According to the Stevens Initiative Impact and Learning Report, more than 75,000 students worldwide have participated in VE programmes supported by structured global partnerships [28]. Kursan Milaković et al. further demonstrated that VE effectively enhances inquiry-based learning and global engagement across disciplinary boundaries [29]. Consequently, VE is increasingly recognised as a pivotal and cost-effective mechanism for promoting cross-cultural interaction and international collaboration [23,28].

VE provides cost-effective learning opportunities that transcend geographical and institutional constraints, offering students meaningful venues to develop collaborative skills and intercultural literacy. Nonetheless, its implementation continues to pose substantial challenges for both educators and learners [30]. These challenges include limited experience with interpersonal communication in digitally mediated environments [31], unequal access to technological resources [32], insufficient digital literacy among teachers and students [33], disparities in language proficiency among exchange partners, divergent instructional objectives, fluctuating learner motivation, and a lack of dedicated time for sustained engagement [34]. Collectively, these constraints make students with lower levels of linguistic competence or digital literacy more vulnerable to marginalisation, thereby restricting the inclusiveness and depth of participation in VE [24]. Against this backdrop, the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, particularly the emergence and widespread adoption of generative AI and AI-driven digital human technologies, has been regarded as a promising avenue for addressing longstanding challenges in VE and supporting more equitable and effective intercultural learning.

2.1.2. AI-Supported Virtual International Exchange

Artificial intelligence is broadly defined as “the ability of machines to acquire knowledge and make decisions through algorithms” [35]. By emulating human cognitive processes, AI enables computers to perform reasoning, learning, and adaptation—capabilities traditionally associated with human intelligence. In this context, AI-driven digital human technology has attracted growing scholarly attention in education. These systems are typically operationalised as intelligent agents presented through a human-like (embodied) interface and equipped with multimodal perception, natural language understanding and generation, dialogue management, speech synthesis, and emotion- and intent-recognition capabilities [9].

This technology is conceptualised as an embodied digital entity that can function as an immersive virtual instructor or learning partner in VE environments. It can fulfil multiple pedagogical roles, including prompting, demonstration, feedback, and collaborative facilitation. Prior research suggests that greater humanisation and embodiment in virtual agents strengthen learners’ perceptions of social presence, trust, and relational commitment, thereby enhancing participation motivation and continuance intention [36]. Regarding appearance and presentation, AI-driven digital humans incorporate anthropomorphic cues such as facial and gaze behaviours, expressive and emotional displays, gestures and body movements, vocal prosody and timbre, and personalised linguistic styles. Through affective feedback and demonstrative behaviours, these cues can reduce communication uncertainty, support rapid task understanding, and enable more socially immersive instructional interaction. With respect to language and dialogue capabilities, AI-driven digital humans offer multilingual and multimodal mediation. Enabled by large language models and advanced speech systems, they can handle multilingual input and output, providing explanations, translation, and paraphrasing that may mitigate linguistic barriers and promote more equitable participation among learners from diverse language backgrounds [37,38]. In addition, emotion- and intent-recognition capabilities allow AI-driven digital humans to deliver highly personalised and accessible learning support. By estimating learners’ comprehension levels, these systems can dynamically adjust lexical complexity, speaking pace, and interaction rhythm, approximating one-to-one scaffolding—an adaptive mechanism consistent with effectiveness evidence from intelligent tutoring systems [39,40]. Beyond pedagogical functionality, AI-driven digital humans also offer advantages in usability and scalability. They can operate continuously and support asynchronous interaction, reducing time-zone and scheduling constraints in international VE. Moreover, their ability to serve large numbers of learners at low marginal cost can alleviate instructors’ workloads associated with repetitive tutoring and coordination, enabling human educators to focus on higher-level instructional design and reflective guidance [41].

Compared with traditional learning management systems (LMSs) and general AI-assisted tools, AI-driven digital humans are not confined to reactive query handling or retrieval-based prompt delivery [9]. Instead, they can proactively initiate instructional prompts, adapt teaching strategies in response to learners’ performance, and engage students through multimodal interaction, thereby providing a more socially immersive VE experience [38]. Empirical evidence suggests that embodied avatars and anthropomorphic agents can have a measurable impact on interpersonal interaction outcomes, learner engagement, and training effectiveness [42]. Research on intelligent tutoring systems further suggests that agents exhibiting higher levels of agency or human-like tutoring characteristics more closely approximate the pedagogical functions of human instructors, particularly in supporting the acquisition of complex skills and delivering timely demonstrations [39]. Collectively, these findings suggest that in virtual international design workshops emphasising design production, cross-cultural oral presentation, and collaborative decision-making, AI-driven digital humans are better positioned to enhance learners’ perceived control, self-efficacy, and interaction quality-through contextualised demonstration and affective scaffolding—than generic AI systems limited to document retrieval or informational support.

In summary, AI-driven digital human technologies function as a complementary and capacity-enhancing extension of traditional VE. By overcoming constraints related to time, geography, and language, they enable personalised, multimodal interactive experiences and broaden access to international learning opportunities. These technologies, therefore, hold considerable potential for reducing linguistic and technical barriers, as well as enhancing the inclusiveness and reach of virtual international exchange.

2.2. Learning Satisfaction and International Learning Intention

Satisfaction is commonly conceptualised as a subjective evaluative judgment formed through the comparison of actual experiences with prior expectations [43]. It represents a holistic assessment of an information system’s performance and the quality of user experience [44]. When users experience high levels of satisfaction, their willingness to continue using the system or engaging with its content tends to increase markedly; conversely, dissatisfaction may prompt discontinuation of use or a shift toward alternative services [45]. Extensive theoretical and empirical work, particularly within the Expectancy–Confirmation Model (ECM), demonstrates that satisfaction is a central determinant of continuance intention in technology-based environments, as satisfied users perceive the system as effectively fulfilling their needs and expectations [46,47]. This relationship has been consistently supported in educational technology research, including studies on blended learning and online learning, where student satisfaction has been shown to predict learning engagement and sustained usage behaviour significantly [48,49]. Similar patterns are observed in empirical studies involving chatbots and virtual advisors, where satisfaction with system interactivity and communication quality positively influences behavioural outcomes and long-term continuance intentions [50,51,52].

2.3. Mechanisms of Learning Self-Efficacy and Interaction Quality

Recent studies employing diverse methodological approaches have consistently identified self-efficacy and interaction quality as key determinants of student satisfaction in online learning environments [53]. Within such contexts, research examining the relationship between self-efficacy and satisfaction has frequently centered on learners’ confidence in their ability to master new technologies or digital tools. Correspondingly, existing literature has explored various domain-specific forms of self-efficacy, including Internet self-efficacy [54,55], computer self-efficacy [56,57,58], and learning management system self-efficacy [59].

Self-efficacy influences a wide range of cognitive and affective processes, shaping individuals’ behavioural choices, motivational patterns, emotional regulation, and mental engagement [60,61]. Higher self-efficacy—whether related to task completion or technological usage—is consistently associated with greater satisfaction with the system or service [62,63]. Research conducted in technology-mediated learning and service environments further demonstrates that when learners who interact with virtual agents or AI-based assistants perceive a heightened sense of task mastery, both satisfaction and performance outcomes tend to improve significantly [64,65].

Interaction quality represents another critical factor affecting student satisfaction. It refers to learners’ perceptions of the timeliness, responsiveness, and effectiveness of interactions during the learning process—an aspect particularly salient in computer-supported learning environments [66]. In online education research, many studies draw on Moore’s interaction model [67], which categorises interactions into learner–learner, learner–teacher, and learner–content forms. Empirical evidence has examined how each type of interaction contributes to learner satisfaction across different instructional settings [65,66,67,68]. However, findings remain inconclusive regarding which type exerts the strongest influence. A parallel body of work suggests that it is not the interaction type per se, but rather the perceived quality of interaction, that constitutes the primary determinant of student satisfaction [68]. In AI-driven VE contexts, AI-driven digital humans—through anthropomorphic embodiment and advanced natural language understanding and generation—can strengthen learners’ sense of social presence and reduce communication frictions (e.g., linguistic barriers and differences in thinking styles), thereby enhancing perceived interaction quality. Higher perceived interaction quality is associated with more favourable evaluations of the exchange activities and more positive affective orientations toward new learning approaches, ultimately influencing participation behaviour [69].

In VE contexts, self-efficacy is posited to positively affect interaction quality by strengthening participation intention, reducing communication anxiety, enhancing communicative confidence, and facilitating self-regulatory behaviours. Prior research indicates that individuals with higher self-efficacy demonstrate a stronger capacity to monitor interaction processes and to utilise platform functionalities, thereby improving communicative accuracy and shared understanding, which in turn contributes to higher perceived interaction quality [70,71]. Extending this logic to AI-mediated interaction, students’ confidence in their ability to communicate effectively with AI-driven digital humans is expected to translate into greater engagement intensity, which subsequently enhances perceived interaction quality and associated learning outcomes in VE. Given that the present study investigates students’ continuance intentions in design-oriented international virtual workshops supported by AI-driven digital humans, the analysis concentrates on learner–digital human perceived interaction quality. To ensure stable estimation and maintain model parsimony, perceived interaction quality among learners (i.e., learner–learner interaction quality) is not modelled as a focal construct in this study.

2.4. External Variables

Although existing theoretical frameworks offer valuable foundations for explaining users’ continuance intentions, they often fail to account for context-specific or subject-specific variables that arise in specialised settings, such as AI-driven digital human-supported VE. Models such as the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) paradigm, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), and Behavioral Reasoning Theory (BRT) all suggest that external variables unique to a particular context—beyond the commonly examined internal constructs—can exert direct or indirect influences on users’ behavioural intentions [47,72,73,74]. These theories collectively highlight the importance of incorporating contextualised determinants to improve explanatory power and ecological validity. To extend the analytical framework and more accurately capture users’ behavioural intentions in AI-driven digital human-supported VE environments, this study introduces three contextually relevant external variables: perceived AI support, system ease of use, and interaction intensity.

2.4.1. Perceived AI Support

Perceived AI support derives from the broader “perceived X” construct widely discussed in information systems and social support research. It refers to users’ subjective evaluation of the functional and socio-emotional assistance provided by AI systems during communication and learning activities, encompassing dimensions such as functional relevance, usability, cultural adaptability, and socio-emotional coherence in feedback [38,75,76]. The emotion- and intent-recognition capabilities of AI-driven digital humans enable timely inference of students’ comprehension levels, supporting real-time adjustments to response complexity, speech rate, and interaction pacing. Such adaptive regulation facilitates near one-to-one, tiered instructional support, providing more context-sensitive assistance in VE environments. These affordances strengthen learners’ perceptions of AI support and promote subsequent system engagement.

Existing studies indicate that perceived AI support exerts both direct and indirect effects on continuance intentions, often through the “usefulness–trust–satisfaction” chain [77,78]. When users perceive AI systems as offering genuinely valuable assistance and experience a sense of being understood or supported during interaction, their acceptance of the system and willingness to continue using it increase substantially [79].

2.4.2. System Ease of Use

Davis originally conceptualised perceived ease of use as a fundamental antecedent shaping both perceived usefulness and continuance intention within TAM [72]. He argued that when users perceive a system as easy to use, they are more inclined to view it as useful, thereby increasing their likelihood of adopting and continuing to use the system [80,81,82]. Subsequent research has extensively extended TAM, repeatedly confirming the robust predictive power of perceived ease of use on continuance intention across a wide range of technological contexts and cultural settings.

System ease of use reflects the degree of subjective effort users believe they must expend when interacting with an information system or digital interface. It encompasses perceptions regarding the difficulty of system operation, the ease with which the system can be learned, and the system’s capacity to support efficient task completion. Recent studies in the domains of conversational agents, chatbots, and AI-driven educational avatars demonstrate that ease of use—manifested through intuitive interaction processes, comprehensible command structures, and clear interface design—plays a direct role in shaping both initial system acceptance and sustained usage intentions [9,38]. Within AI-driven digital human-supported international VE, this suggests that platforms offering straightforward operational procedures and intuitive interaction pathways may encourage more frequent and proactive learner engagement. Consequently, a higher perceived ease of use of the system is likely to foster more positive experiential evaluations and strengthen students’ willingness to participate continuously in such learning environments.

2.4.3. Interaction Intensity

Interaction intensity refers to the frequency of exchanges between communication partners within a specified time interval [83,84]. The construct is widely applied in commercial and financial service contexts, where higher interaction intensity has been shown to facilitate more robust information flow and reduce uncertainty between parties [85]. Research further demonstrates that maintaining frequent and substantive interactions with customers or organisational partners enhances familiarity, trust, and the richness of information exchange [86,87], which in turn promotes satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, loyalty, and repurchase intention [88].

In cross-cultural environments, such as VE, high levels of interaction intensity can provide additional pedagogical value by enabling rapid clarification, immediate corrective feedback, modelling of communicative behaviours, and context-rich explanations. These mechanisms collectively reduce communication ambiguity, strengthen learners’ sense of control, and enhance satisfaction—ultimately increasing their willingness to use and continue using the technology [52]. Kang et al. similarly contend that in interactions with intelligent virtual assistants, the frequency of exchanges, depth of responses, and level of user engagement significantly shape sustained usage intentions by improving perceived usefulness and satisfaction [89]. AI-driven digital humans offer clear advantages in terms of usability and scalability. By supporting continuous availability and flexible interaction schedules, they alleviate time zone and coordination constraints in international VE. At the same time, they sustain high levels of interaction at low marginal cost, substantially reducing instructors’ workload in repetitive design guidance and coordination tasks. These benefits directly contribute to students’ willingness to persist in AI-driven digital human-supported VE activities.

2.5. Variable Definitions and Measurement

Based on the research framework and relevant literature, this study developed a structured questionnaire to measure the key constructs. The operational definitions, measurement items, and scale sources for each variable are summarised in Table 1. A detailed mapping of each construct and its corresponding references is also provided in Table 1 to ensure conceptual clarity, consistency of measurement, and alignment with established empirical instruments. (Detailed questionnaire information is provided in Table A1 in the Appendix A).

Table 1.

Variable operationalization and reference scales.

2.6. Research Hypotheses and Model Development

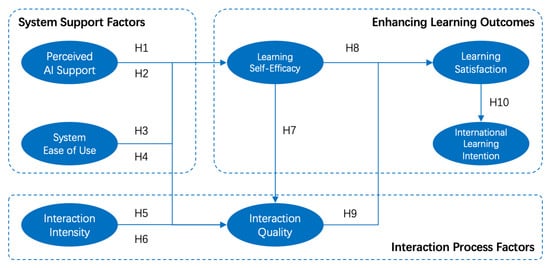

Drawing upon the preceding theoretical analysis and contextual considerations, this study develops a mechanism model to explain sustained participation in design-oriented VE workshops supported by AI-driven digital humans (Figure 1). The model conceptualises perceived AI support, system ease of use, and interaction intensity as exogenous antecedents that influence learning satisfaction through the mediating processes of learning self-efficacy and interaction quality. These relational pathways ultimately shape students’ international learning intention.

Figure 1.

Research structure.

Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Perceived AI support positively influences learning self-efficacy.

H2.

Perceived AI support positively influences interaction quality.

H3.

System ease of use positively influences learning self-efficacy.

H4.

System ease of use positively influences interaction quality.

H5.

Interaction intensity positively influences learning self-efficacy.

H6.

Interaction intensity positively influences interaction quality.

H7.

Learning self-efficacy positively influences interaction quality.

H8.

Learning self-efficacy positively influences learning satisfaction.

H9.

Interaction quality positively influences learning satisfaction.

H10.

Learning satisfaction positively influences international learning intention.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

This study collected data through an online questionnaire administered to undergraduate and postgraduate students who had actively participated in online international design workshops supported by AI-driven digital humans. The survey was conducted between September and November 2025. Participants accessed an instruction page via a survey link and voluntarily completed the questionnaire after providing informed consent, with the option to quit at any time. In addition to basic demographic information, all constructs were measured using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree).

This study initially planned a multi-wave measurement design across different workshop phases (T1: system support and early engagement; T2: self-efficacy and satisfaction; T3: international learning intention) to improve temporal ordering and strengthen causal inference. However, in a cross-institutional, project-based implementation context, repeated measurements would likely elevate risks of sample attrition and non-random missingness. Additionally, heterogeneity in course pacing and ongoing platform updates may compromise the consistency of measurement intervals, thereby undermining the stability of estimation. Given these feasibility considerations, a single-wave cross-sectional survey design was adopted.

To ensure sample validity, three inclusion criteria were established: (1) Participation in an international design workshop supported by AI-driven digital humans or conversational agents within the past semester; (2) Actual use of at least one AI-driven digital human function during task progression (e.g., text or voice interaction, contextual feedback, language mediation, or progress reminders); (3) Completion of a minimum of two rounds of team discussions/reviews and one interim deliverable.

To enhance data quality and mitigate common method bias, the questionnaire randomised item order, incorporated attention-check items, and applied screening procedures based on response time, straight-lining detection, and IP/device information. Demographic variables included gender, academic level, major of study, overseas learning experience, weekly duration of online collaborative activities, and primary working language. Sampling was primarily conducted using convenience sampling, complemented by snowball sampling. A minimum effective sample size of ≥200 was targeted to satisfy statistical power requirements and accommodate the complexity of the structural equation model. All procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional ethics guidelines and data confidentiality standards. No personally identifiable information was collected, and all data were used exclusively for academic research.

A total of 660 responses were collected, of which 611 were retained after excluding invalid submissions. The questionnaire contained 21 measurement items. The final sample size met Jackson’s criterion for maximum likelihood estimation—requiring a parameter-to-sample ratio (p:n) of at least 1:10 [96]—and was therefore suitable for subsequent SEM analysis. The distribution of respondents’ demographic characteristics is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic Statistics.

3.2. Reliability Analysis

Cronbach’s α coefficient and total correlation coefficient of correction items (CITC) were used to validate the questionnaire. According to Table 3, the CITC of all constructs is higher than 0.6, and the reliability coefficient does not improve significantly after the deletion of questions. Furthermore, Cronbach’s coefficient of reliability is higher than 0.7 [97,98], and all corrected item–total correlations are above 0.5 [97]. Thus, the questionnaire and scale used in this study demonstrate a high degree of internal consistency, which is suitable for further analysis.

Table 3.

Reliability analysis results (N = 611).

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

While the model and constructs of this study are based on established theories and prior academic work, the measurement items were adapted from established scales developed by previous researchers. Therefore, it was necessary to use exploratory factor analysis to ensure the structural validity of the measurement model. The questionnaire data were tested using SPSS 22 software, and KMO and Bartlett’s sphericity tests were used to judge whether the questionnaire and scale were suitable for factor analysis. As shown in Table 4, the KMO value was 0.891, which was significantly higher than the standard of 0.70 [99]. The Bartlett’s sphericity test yielded a significant result (p < 0.05), thus indicating that the model was suitable for factor analysis.

Table 4.

KMO and Bartlett Sphericity Test.

This study then used principal component analysis to measure the distinctiveness and accuracy of the scale dimensions. As shown in Table 5, factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted, resulting in a cumulative variance explained of 76.316%, and the interpretation rates of individual factors were all below 40%. No single factor accounted for more than 40% of the variance, indicating the absence of significant common method bias (CMB) according to Harman’s single-factor test [100]. There was no common method variation in the scale used in this study, and the number of factors matched the dimensions of the preset model in this study.

Table 5.

Principal Component Analysis Results of Questionnaire Values.

This study then used principal component analysis to extract new factors from the original scale items. As shown in Table 6, factors with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted, resulting in a cumulative variance explained of 69.704%, and the interpretation rates of individual factors were all below 40%. No single factor explained most of the variance, thus meeting Thompson’s criteria [101]. The results indicate that CMB was not a significant concern in this study, and the number of factors matched the dimensions of the preset model in this study.

Table 6.

Exploratory Factor Analysis Results of Measurement Items.

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

AMOS V22.0 was used to analyze the structural equation model. AMOS has been used in several studies, which have proven to be reliable structural equation modeling software. According to Anderson and Gerbing, data analysis was divided into two stages [102]. The first stage is the Measurement Model, which employs the maximum likelihood estimation method and estimates the following parameters: factor loadings, reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. This is done according to studies of convergent validity by Hair et al. [101], Nunnally and Bernstein [103], and Fornell and Larcker [104], and studies of standardized factor loadings by Chin [105] and Hooper et al. [106], as shown in Table 7 below. The standardized factor load in this study is higher than 0.6, the reliability of the research construct composition is higher than 0.7, and the average variance extracted (AVE) is higher than 0.5, thus indicating that this construct has good convergent validity [101].

Table 7.

Convergent factor analysis results (N = 611).

The criterion of Fornell and Larcker [104] was adopted to assess discriminant validity. If the square root of the AVE of each construct is greater than the correlation coefficient between the constructs, the model is considered to have adequate discriminant validity. According to the results, all diagonals in this study have greater values than those outside the diagonals, indicating that each of the constructs in this study has good discriminant validity (as shown in Table 8).

Table 8.

Inter-construct correlations and the square root of AVE (N = 611).

3.5. Model Fit Test

A selection of indices (MLχ2, DF, χ2/DF, RMSEA, TLI, CFI, NFI, IFI) has been used as a parameterized measure for evaluating the model fit of the structural model based on studies performed by Jackson et al. [107], Kline [108], Schumacker [109], and Hu and Bentler [110]. As shown in Table 9, the study construct was measured based on the study hypothesis and model. Furthermore, all standard fit indices exceeded the recommended thresholds, demonstrating that the structural model exhibited a good fit, and the theoretical framework of the study hypothesis made sense in light of the survey data.

Table 9.

Results of measurement model fitness.

3.6. Path Analysis

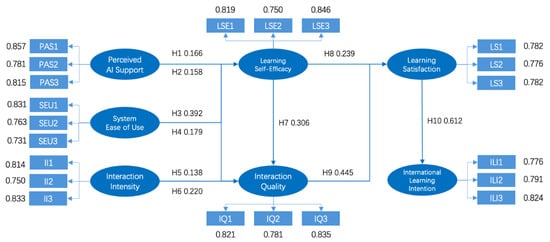

Table 10 presents the path analysis results. PAS (p = 0.001), SEU (p < 0.001), and II (p = 0.010) significantly affect LSE. Similarly, PAS (p = 0.001), SEU (p = 0.001), II (p < 0.001), and LSE (p < 0.001) significantly affect IQ. Finally, LSE (p < 0.001) and IQ (p < 0.001) significantly affect LS. LS (p < 0.001) significantly affects ILI.

Table 10.

Regression coefficient.

3.7. Hypothesis Explanation

This study employs structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the structural relationships between variables based on data from university students who have participated in online international design workshops supported by AI-driven digital humans. It identifies and tests the pathways and associations through which key factors—perceived AI support, system ease of use, interaction intensity, and interaction quality—shape learning self-efficacy and international learning intention. Based on the empirical results, the study offers actionable recommendations for course design, platform optimisation, and organizational implementation to inform decision-making by academic departments, platform developers, and educational administrators.

Table 10 shows the standardised path coefficients of the structural model in this study. A larger magnitude of the coefficient indicates a stronger predictive influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Figure 2 illustrates the structural model, displaying the validated path relationships and their respective coefficients.

Figure 2.

Research structure pattern diagram.

4. Discussions

4.1. System Support Factors: Perceived AI Support and System Ease of Use

This study first investigated the influence of system support factors on learners’ experiences. The results indicate that students’ perceived support from AI-driven digital humans is significantly and positively associated with both learning self-efficacy and interaction quality (H1 and H2 supported). These findings are consistent with recent evidence suggesting that high-quality interactions with generative AI are associated with higher learning motivation and creative self-efficacy [111]. Within VE environments, the targeted feedback, real-time clarification, and linguistic scaffolding provided by AI-driven digital humans strengthened students’ confidence and willingness to articulate ideas during cross-cultural design collaboration.

System ease of use also shows positive associations with learning self-efficacy and interaction quality (H3 and H4 supported). When AI-supported virtual exchange platforms are intuitive and impose minimal cognitive load, students report higher engagement and more efficient communication. These findings are consistent with the foundational logic of the Technology Acceptance Model, which posits that perceived ease of use reduces cognitive burden, promotes more positive user experiences, and ultimately enhances students’ confidence and collaborative performance in complex design activities.

Collectively, the results suggest that system support factors shape learners’ experiences through a mechanism that can be summarised as “low-friction usage → strong supportive feedback → enhanced self-efficacy and interaction quality.” These outcomes also align with a widely documented pattern in prior research, which shows that AI-assisted instruction can substantially increase student engagement and motivation. For example, Kestin et al. reported in a randomised controlled trial that students using AI tutoring systems not only achieved higher learning efficiency but also “felt more engaged and motivated” compared with those in traditional classroom environments [41]. The current study extends this insight to international design workshop contexts, where user-friendly AI-driven digital humans enhance learners’ perceived control and satisfaction by providing intuitive operation and adaptive support. Furthermore, the findings reveal a sequential mechanism: perceived ease of use and perceived AI support enhance learning self-efficacy, and heightened self-efficacy subsequently improves interaction quality. This suggests that as students become more proficient in using the VE platform and AI tools, they are more inclined to participate actively and collaborate meaningfully, thereby cultivating a more supportive and higher-quality online interaction environment.

4.2. Interaction Process Factors: Interaction Intensity and Interaction Quality

Interaction intensity reflects the frequency and depth of students’ communication with AI-driven digital humans and peers. The results indicate that interaction intensity is significantly and positively associated with both students’ self-efficacy and interaction quality (H5 and H6 supported). This suggests that frequent engagement in discussions and collaborative activities provides learners with greater opportunities for practice and feedback, thereby enhancing their confidence and competence. Consistent with social cognitive theory [62], successful task experiences heighten self-efficacy; thus, high interaction intensity likely affords students repeated instances of positive reinforcement, reinforcing their belief in their ability to manage cross-cultural design challenges effectively. At the same time, increased interaction opportunities may facilitate smoother communication, more timely feedback, and more thorough clarification of design issues and task requirements. These patterns may reflect greater design maturity and improved efficiency in team collaboration. Wu et al. similarly reported that online learning self-efficacy positively predicts student engagement [112], suggesting a virtuous cycle whereby engagement strengthens self-efficacy, which in turn fosters even higher-quality interactions. The findings of this study indicate that this reciprocal mechanism is manifested not only in behavioural engagement but also in the enhancement of interaction quality itself.

In addition, learning self-efficacy was found to predict interaction quality (H7 supported) significantly. The results indicate that students with higher self-efficacy tend to participate more actively and communicate more clearly in online discussions, which is associated with higher interaction quality. This aligns with existing research, which shows that self-efficacy in online learning environments has a positive influence on satisfaction, and that the quality of teacher–student interaction is a critical determinant of online learning outcomes [55,113]. Confident students are typically more capable of navigating platforms and digital tools, seeking assistance when necessary, and engaging in constructive exchange. These capabilities not only lay the foundation for subsequent satisfaction and motivation but also highlight the instructional importance of identifying learners with lower self-efficacy and providing targeted scaffolding, explicit role assignment, or additional guidance within workshop settings. In summary, the findings suggest that strong interaction processes and high-frequency communication not only directly boost student confidence and performance but also cultivate an optimized learning environment characterised by deeper, more transparent, and more effective exchanges. Such interactions form the core of high-quality VE experiences supported by AI-driven digital humans.

4.3. Enhancing Learning Outcomes: Learning Self-Efficacy, Satisfaction, and Continued Participation

This study further explored how the identified influencing factors translate into learning outcomes and students’ future engagement intentions. First, learning self-efficacy was found to have a significant and positive impact on learning satisfaction (H8 supported). This suggests that when AI-driven digital humans support students in activities such as prototype development, collaborative discussion, and the interpretation of critique—thereby strengthening their confidence in completing design tasks—students are more inclined to adopt deeper learning strategies. Such strategies promote positive learning experiences and ultimately elevate satisfaction. Similarly, the results indicate that interaction quality is positively associated with satisfaction (H9 supported). This suggests that higher-quality communication may strengthen students’ perceptions of adequate instructional support and timely issue resolution, which in turn may be linked to greater satisfaction with the collaborative design process and perceived design outcomes. A rich, interactive design environment additionally offers emotional reinforcement and a sense of belonging, both of which contribute to heightened satisfaction with AI-supported VE experiences.

Furthermore, learning satisfaction exerts a significant positive influence on students’ willingness to continue participating in international learning activities (H10 supported). When learning experiences are satisfying—indicating the fulfilment of learning goals and positive evaluations of platform affordances—students demonstrate a stronger inclination to engage in similar programmes in the future. This finding is consistent with the core propositions of Expectancy Confirmation Theory and the Continuance Usage Model [43], which identify satisfaction as a key antecedent of continuance intention. The present study extends these insights to AI-driven digital human-supported VE, demonstrating that when such systems effectively meet learners’ needs and deliver positive experiential value, they substantially enhance students’ willingness to participate in subsequent design-oriented virtual exchange activities.

In summary, the validation of all proposed hypotheses provides a coherent causal framework linking system characteristics to learning outcomes. Integrating AI-driven digital humans into international design education may help mitigate structural barriers commonly observed in traditional virtual exchange environments and is statistically associated with several factors linked to students’ continuance intention. These findings offer a theoretical groundwork for improving equitable access to international learning opportunities, particularly in underserved or resource-constrained regions, and for advancing the broader internationalisation agenda in higher education.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Significance

This study makes several theoretical contributions by introducing AI-driven digital human technology into a virtual international design workshop context and integrating multiple theoretical perspectives to examine students’ continuance intention in AI-supported environments. The research proposes and validates a sequential causal chain linking system support factors, interaction process factors, enhanced learning outcomes, and continuous participation intention. The findings reveal that when students perceive AI-driven digital humans as providing effective cognitive support (e.g., tiered feedback, adaptive language mediation) and socio-emotional support, their learning self-efficacy and interaction quality improve significantly. Moreover, higher interaction frequency provides learners with more opportunities for practice and feedback, reinforcing their sense of control and deepening their learning experiences. Learning satisfaction emerges as a pivotal mechanism through which these process-oriented experiences translate into intention for continuous participation. Once students’ expectations are met or exceeded, they become more willing to engage in similar international learning activities in the future. Collectively, these results provide empirical evidence that AI-driven digital humans can reduce participation barriers in cross-contextual, international design collaborations and meaningfully extend the theoretical understanding of AI-assisted learning behaviour.

Furthermore, unlike previous studies that conceptualise AI primarily as a general-purpose digital tool, this research underscores the need to recognise the multi-functional role of AI-driven digital humans in design workshops—as process-oriented feedback providers, demonstrators, and mediators of cross-cultural communication. The results further indicate that when learners perceive AI-driven digital humans as exhibiting social presence and delivering contextualised, responsive interactions, these agents can generate additional positive effects on learning motivation, interaction quality, and satisfaction. This contributes a contextually grounded theoretical refinement to existing discussions on how AI technologies shape cognitive processes, collaborative behaviour, and creative practices in design-oriented learning environments. The findings also provide empirical support for emerging theoretical work on AI avatars and avatar-based pedagogical agents, highlighting their potential to reshape the dynamics of online and cross-cultural design education.

5.2. Practical Implications

Based on the quantitative findings, several practical implications can be drawn to enhance students’ sustained engagement in AI-supported virtual international design workshops.

First, educators and programme designers should leverage the unique advantages of AI-driven digital humans—including their round-the-clock availability, multilingual support, and capacity for contextualised interaction—to provide continuous and personalised guidance for learners across different time zones. Such support can reduce cross-cultural misinterpretations, facilitate smoother collaboration, and compensate for disparities in teaching resources or communicative competence. Ensuring that students receive timely assistance and culturally sensitive mediation not only strengthens their motivation and confidence but also promotes educational equity by expanding access to international learning experiences for students in under-resourced regions.

Second, the user-friendliness of AI-supported VE platforms is critical. Clean, intuitive interfaces and coherent interaction logic minimise the operational burden on learners, enabling them to concentrate more on design tasks. Enhancing system ease of use contributes to a more seamless learning experience, allowing students to enter productive learning states more rapidly and build confidence in navigating AI-mediated interactions.

Third, high-intensity interaction should be intentionally cultivated throughout the design process. Increasing both the frequency and depth of engagement—through structured discussions, real-time Q&A sessions, and instant demonstrations—can significantly improve learners’ task mastery and self-efficacy. Embedding short, regular “synchronous checkpoints” and enabling AI-driven digital humans to initiate real-time feedback within commonly used collaborative platforms (e.g., Miro, Figma, prototyping tools) may further amplify the cumulative benefits of interaction intensity. High-quality interactions not only provide timely feedback and reinforce experiences of success but also strengthen students’ sense of belonging and satisfaction, thereby fostering sustained participation in virtual international learning activities.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study is subject to several limitations that offer essential directions for future research.

- Although this study did not restrict participants’ institutional backgrounds, eligibility screening resulted in a sample predominantly drawn from design students in the Chinese context, which helped ensure comparable learning settings and strengthen internal validity. Consequently, the absence of multicultural groups precluded rigorous tests of cross-cultural validity and measurement invariance. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings should be confined to similar educational and workshop contexts. Future research should recruit multinational samples and conduct multigroup invariance tests, as well as examine the moderating effects of cultural and educational system differences.

- This study conceptualised “AI-driven digital humans” as a holistic intervention and did not differentiate the effects of specific design attributes—such as appearance, vocal characteristics, behavioural cues, or emotional expressiveness—on learning experiences. Future research could adopt mixed-factorial experimental designs or factorial approaches to investigate the independent and interactive influences of these design variables on self-efficacy, interaction quality, satisfaction, and overall learning outcomes.

- This study was conducted within the constraints of current collaborative platforms and existing AI-driven digital human capabilities. As AI technologies, multimodal learning environments, and learning analytics tools continue to evolve rapidly, future iterations may transform interactional dynamics, learner behaviours, and experiential trajectories in ways not yet observable. Further research is therefore needed to monitor how technological advancements reshape students’ international learning intention and to provide timely, evidence-based guidance for instructional design and educational practice.

- This study relies primarily on cross-sectional questionnaire data and participants’ self-reports. Accordingly, it may be susceptible to common method bias and social desirability effects, which limit the ability to infer causal dynamics and assess long-term behavioural change. Future research could incorporate objective behavioural measures—such as system logs, turn/message counts, response latency, and turn length—alongside learning outcome indicators (e.g., instructor ratings, portfolio-based evaluations, and peer-review results) to triangulate subjective reports with observed behaviours.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F. and C.Y.; methodology, C.Y. and Z.W.; formal analysis, C.Y. and Z.W.; data curation, Y.F. and C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.F.; writing—review and editing, C.Y. and J.M.; funding acquisition, Y.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jiangsu Provincial Social Science Fund, grant number 23JYD002, and the 2024 Universities’ Philosophy and Social Science Research in Jiangsu Province, grant number 2024SJYB0653.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Fine Arts, Nanjing Normal University (NNU SFA-E-2025-004) on [19 September 2025].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The questionnaire used in the survey.

Table A1.

The questionnaire used in the survey.

| Factor | Code | ltem |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived AI Support (PAS) | PAS1 | AI-driven digital humans can provide helpful support as I complete tasks. |

| PAS2 | Feedback from AI-driven digital humans helps me advance my task progress. | |

| PAS3 | When needed, AI-driven digital humans respond promptly and effectively to support my learning and collaboration. | |

| System Ease of Use (SEU) | SEU1 | I find the virtual exchange platform/system simple to operate and easy to get started with. |

| SEU2 | I can clearly understand how to use the system interface and its features. | |

| SEU3 | I require minimal extra effort when using the system and AI-driven digital human. | |

| Interaction Intensity (II) | II1 | During the design workshop, I interacted frequently with the AI-driven digital human. |

| II2 | I actively participated in discussions, asked questions, or responded to others within the allotted time. | |

| II3 | I invested a significant amount of time and effort in communication and engagement cycles (such as speaking, commenting, or messaging) throughout the collaborative process. | |

| Learning Self-Efficacy (LSE) | LSE1 | I am confident in completing the learning and design tasks within the workshop. |

| LSE2 | Even when encountering difficulties, I can adjust my approach and keep moving forward with the tasks. | |

| LSE3 | I can effectively manage my learning process (such as planning, execution, and reflection) and fulfill collaborative requirements. | |

| Interaction Quality (IQ) | IQ1 | Our virtual exchange is typically timely, with no prolonged periods without response. |

| IQ2 | Interactions are precise and targeted, helping me understand issues or advance solutions. | |

| IQ3 | During exchanges, I experience smooth communication and receive constructive feedback (e.g., actionable suggestions/adequate explanations). | |

| Learning Satisfaction (LS) | LS1 | Overall, I am satisfied with my learning experience in the design workshop, which an AI-driven digital human supported. |

| LS2 | The learning process and outcomes of this design workshop met (or exceeded) my expectations. | |

| LS3 | I believe the overall quality of the workshop’s organization and support (including AI-driven digital human) was high. | |

| International Learning Intention (ILI) | ILI1 | I would be willing to participate in similar virtual international design workshops in the future. |

| ILI2 | I would be willing to continue participating in AI-driven digital human-supported international design workshops in the future. | |

| ILI3 | I would be willing to recommend this type of AI-driven digital human-supported virtual international design workshop to my classmates. |

References

- O’Dowd, R.; Dooly, M. Exploring teachers’ professional development through participation in virtual exchange. ReCALL 2022, 34, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanham, C.; Voskuil, C. Virtual exchange: Expanding access to global learning. In Academic Voices; Chandos Publishing: Kingston Upon Hull, UK, 2022; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, M.; Müller-Hartmann, A. Task design for telecollaborative exchanges: In search of new criteria. System 2017, 64, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, L.; Gupta, T.; Shree, A. Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galan-Lominchar, M.; Roque, I.M.-S.; Cazallas, C.d.C.; McAlpin, R.; Fernández-Ayuso, D.; Ribeiro, A.S.F. Nursing students’ internationalization: Virtual exchange and clinical simulation impact cultural intelligence. Nurs. Outlook 2024, 72, 102137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, N.L.; Craig, S.D. Learning with virtual humans: Introduction to the special issue. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2021, 53, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinatra, A.M.; Pollard, K.A.; Files, B.T.; Oiknine, A.H.; Ericson, M.; Khooshabeh, P. Social fidelity in virtual agents: Impacts on presence and learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smutny, P.; Schreiberova, P. Chatbots for learning: A review of educational chatbots for the Facebook Messenger. Comput. Educ. 2020, 151, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.S.M.; Falcão, F.; Costa, L.; Lunn, B.S.; Pêgo, J.M.; Costa, P. Here’s to the future: Conversational agents in higher education—A scoping review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 122, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, N.L.; Romine, W.L.; Craig, S.D. Measuring pedagogical agent persona and the influence of agent persona on learning. Comput. Educ. 2017, 109, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Tian, J.; Li, Y. Enhancing student engagement in online collaborative writing through a generative AI-based conversational agent. Internet High. Educ. 2025, 65, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Min, Q. Exploring continued usage of an AI teaching assistant among university students: A temporal distance perspective. Inf. Manag. 2024, 61, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikström, P.; Valentini, C.; Sivunen, A.; Kärkkäinen, T. How pedagogical agents communicate with students: A two-phase systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2022, 188, 104564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.J.; Lim, K.Y.; Kim, J. Locus of control, self-efficacy, and task value as predictors of learning outcome in an online university context. Comput. Educ. 2013, 62, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Mannino, M.; Nieschwietz, R.J. Information technology acceptance in the internal audit profession: Impact of technology features and complexity. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2009, 10, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Understanding Attitudes and Predictiing Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, Y.J.; Park, S.; Shin, E.K. Students’ expectation, satisfaction, and continuance intention to use digital textbooks. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.R.; He, J. A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Teo, T.S.H.; Liu, L. Perceived value and continuance intention in mobile government service in China. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 48, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienties, B.; Lewis, T.; O’Dowd, R.; Rets, I.; Rogaten, J. The impact of virtual exchange on TPACK and foreign language competence: Reviewing a large-scale implementation across 23 virtual exchanges. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2022, 35, 577–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.-H.; Chuang, H.-H.; Albanese, D. Investigating student agency and affordances during online virtual exchange projects in an ELF context from an ecological CALL perspective. System 2022, 109, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, R.; Sauro, S.; Spector-Cohen, E. The role of pedagogical mentoring in virtual exchange. Tesol Q. 2020, 54, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kido, K.; Slain, D.; Kamal, K.M.; Lee, J.C. Adapting the layered learning model to a virtual international exchange program. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2022, 14, 1500–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, M.W.; Ferreira-Lopes, L. Emerging trends in telecollaboration and virtual exchange: A bibliometric study. Educ. Rev. 2023, 75, 558–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, R. Emerging trends and new directions in telecollaborative learning. Calico J. 2016, 33, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiftçi, E.Y. A review of research on intercultural learning through computer-based digital technologies. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2016, 19, 313–327. [Google Scholar]

- Guth, S.; Helm, F. Telecollaboration 2.0: Language, Literacies and Intercultural Learning in the 21st Century; Peter Lang: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Eremionkhale, A.; Sadeh, J.; Sun, Y. A Cooperative Virtual Exchange within the Economics Curriculum: A pilot study on embedding elements of global competence within an economics course. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2025, 50, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismailov, M. Virtual exchanges in an inquiry-based learning environment: Effects on intra-cultural awareness and intercultural communicative competence. Cogent Educ. 2021, 8, 1982601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; Jones, P. COVID-19 and entrepreneurship education: Implications for advancing research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, C.; Davies, C.L.; Crookes, P.; McGhee, S.; Roxburgh, M. COVID 19: Disruptive impacts and transformative opportunities in undergraduate nurse education. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 46, 102807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedotun, T.D. Sudden change of pedagogy in education driven by COVID-19: Perspectives and evaluation from a developing country. Res. Glob. 2020, 2, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, R. From telecollaboration to virtual exchange: State-of-the-art and the role of UNICollaboration in moving forward. Res.-Publ. Net. 2018, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, F. The practices and challenges of telecollaboration in higher education in Europe. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2015, 19, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, J.; Patiño, E.; Marulanda, C. Systematic review of artificial intelligence in education: Trends, Benefits, and challenges. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, K.L.; Biocca, F. The effect of the agency and anthropomorphism on users’ sense of telepresence, copresence, and social presence in virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2003, 12, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, M.C.; Robinson, S.A.; Ertl, B. AI-based avatars are changing the way we learn and teach: Benefits and challenges. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2024; p. 1416307. [Google Scholar]

- VanLehn, K. The relative effectiveness of human tutoring, intelligent tutoring systems, and other tutoring systems. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 46, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, J.A.; Fletcher, J.D. Effectiveness of intelligent tutoring systems: A meta-analytic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 42–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestin, G.; Miller, K.; Klales, A.; Milbourne, T.; Ponti, G. AI tutoring outperforms in-class active learning: An RCT introducing a novel research-based design in an authentic educational setting. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendran, A.; Compton, S.; Follette, W.C.; Golenchenko, A.; Compton, A.; Grizou, J. Avatar led interventions in the Metaverse reveal that interpersonal effectiveness can be measured, predicted, and improved. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 351–370. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.; Lin, H.; Gong, W.; Guan, R.; Dong, L. An analysis of users’ continuous use intention of academic library social media using the WeChat public platform as an example. Electron. Libr. 2024, 42, 136–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, X. Examining generative AI user continuance intention based on the SOR model. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; Hone, K.; Liu, X. A cross-cultural examination of the impact of social, organisational and individual factors on educational technology acceptance between B ritish and L ebanese university students. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2015, 46, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.M.; Jo, H. Understanding Continuance Intention of Generative AI in Education: An ECM-Based Study for Sustainable Learning Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeh, M.T.; Abduljabbar, F.H.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Waly, F.J.; Alnaami, I.; Aljurayyan, A.; Alzaman, N. Students’ satisfaction and continued intention toward e-learning: A theory-based study. Med. Educ. Online 2021, 26, 1961348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Phongsatha, T. Satisfaction and continuance intention of blended learning from perspective of junior high school students in the directly-entering-socialism ethnic communities of China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.-F.; Ho, C.-H.; Chung, M.-H. Theoretical integration of user satisfaction and technology acceptance of the nursing process information system. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Jiang, H. How do AI-driven chatbots impact user experience? Examining gratifications, perceived privacy risk, satisfaction, loyalty, and continued use. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2020, 64, 592–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, R.; Pu, C. “I am chatbot, your virtual mental health adviser.” What drives citizens’ satisfaction and continuance intention toward mental health chatbots during the COVID-19 pandemic? An empirical study in China. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221090031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, H.G. Remote learning during COVID-19: Cognitive appraisals and perceptions of english medium of instruction (EMI) students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-C.; Tsai, C.-C. Internet self-efficacy and preferences toward constructivist Internet-based learning environments: A study of pre-school teachers in Taiwan. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2008, 11, 226–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Y.-C.; Walker, A.E.; Schroder, K.E.; Belland, B.R. Interaction, Internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. Internet High. Educ. 2014, 20, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.K. The relationships between academic self-efficacy, computer self-efficacy, prior experience, and satisfaction with online learning. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2015, 29, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.D.; Hornik, S.; Salas, E. An empirical examination of factors contributing to the creation of successful e-learning environments. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2008, 66, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.K. Computer self-efficacy, academic self-concept, and other predictors of satisfaction and future participation of adult distance learners. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2001, 15, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Tutty, J.I.; Su, Y. Influence of Learning Management Systems Self-efficacy on E-Learning Performance. J. Sch. Educ. Technol. 2010, 5, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V.S. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, S. The association of career talent self-efficacy, positive future expectations and personal growth initiative. Psycho-Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 11, 246–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: Dallas, TX, USA, 1997; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Compeau, D.R.; Higgins, C.A. Computer self-efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, D.G.; Deneka, A.A.; Theune, M.; Neerincx, M.A.; Cremers, A.H. An embodied conversational agent coach to support societal participation learning by low-literate users. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 22, 1215–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.A.; Powell, W.; Louwerse, M.M.; Hendrickson, A.T. Behavior and self-efficacy modulate learning in virtual reality simulations for training: A structural equation modeling approach. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1250823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzmuller, M.; Sin, H.-P.; Howe, M.; Fatimah, S. Investigating the uniqueness and usefulness of proactive personality in organizational research: A meta-analytic review. Hum. Perform. 2015, 28, 351–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.G. Three types of interaction. Am. J. Distance Educ. 1989, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Norgard, C. Assessing the quality of online courses from the students’ perspective. Internet High. Educ. 2006, 9, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaber, S.S.A. Factors influencing students willingness to continue online learning as a lifelong learning: A path analysis based on MOA theoretical framework. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2024, 7, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.-H.; Hao, Y.; Tai, K.-H. Online learning self-efficacy as a mediator between the instructional interactions and achievement emotions of rural students in elite universities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Gong, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, N.; Ai, L. Interaction and learning engagement in online learning: The mediating roles of online learning self-efficacy and academic emotions. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2022, 94, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Westaby, J.D. Behavioral reasoning theory: Identifying new linkages underlying intentions and behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 98, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Tran, T.; Du, Z. Artificial intelligence in education: A systematic literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Cui, W. Perceived support and AI literacy: The mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1415248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Yang, J.; Qu, X. Utilization of, perceptions on, and intention to use AI chatbots among medical students in China: National Cross-sectional Study. JMIR Med. Educ. 2024, 10, e57132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.T.A.; Phan, T.Y.N.; Nguyen, T.K.; Le, N.B.T.; Nguyen, N.T.A.; Le, T.T.D. Understanding continuance intention toward the use of AI chatbots in customer service among generation Z in Vietnam. Acta Psychol. 2025, 259, 105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.; Shamszare, H. Investigating the impact of user trust on the adoption and use of ChatGPT: Survey analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e47184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval. Ind. 1996, 189, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ankitha, S.; Basri, S. The effect of relational selling on life insurance decision making in India. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1505–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmatier, R.W.; Dant, R.P.; Grewal, D.; Evans, K.R. Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: A meta-analysis. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herjanto, H.; Gaur, S.S. Intercultural interaction and relationship selling in the banking industry. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.-Y. Customer orientation and cross-buying: The mediating effects of relational selling behavior and relationship quality. J. Manag. Res. 2012, 4, 334–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, C.; Patterson, P. Services Marketing; Pearson Australia: Docklands, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Herjanto, H.; Amin, M. Repurchase intention: The effect of similarity and client knowledge. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1351–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]