A Cross-Scale Feature Fusion Method for Effectively Enhancing Small Object Detection Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- The focus on key features is not accurate enough, and the feature discrimination ability is insufficient, leading to the loss of small object features and redundancy of invalid information during the downsampling process.

- 2.

- The correlation between inter-layer features is not fully explored, resulting in insufficient expression of object features.

- 1.

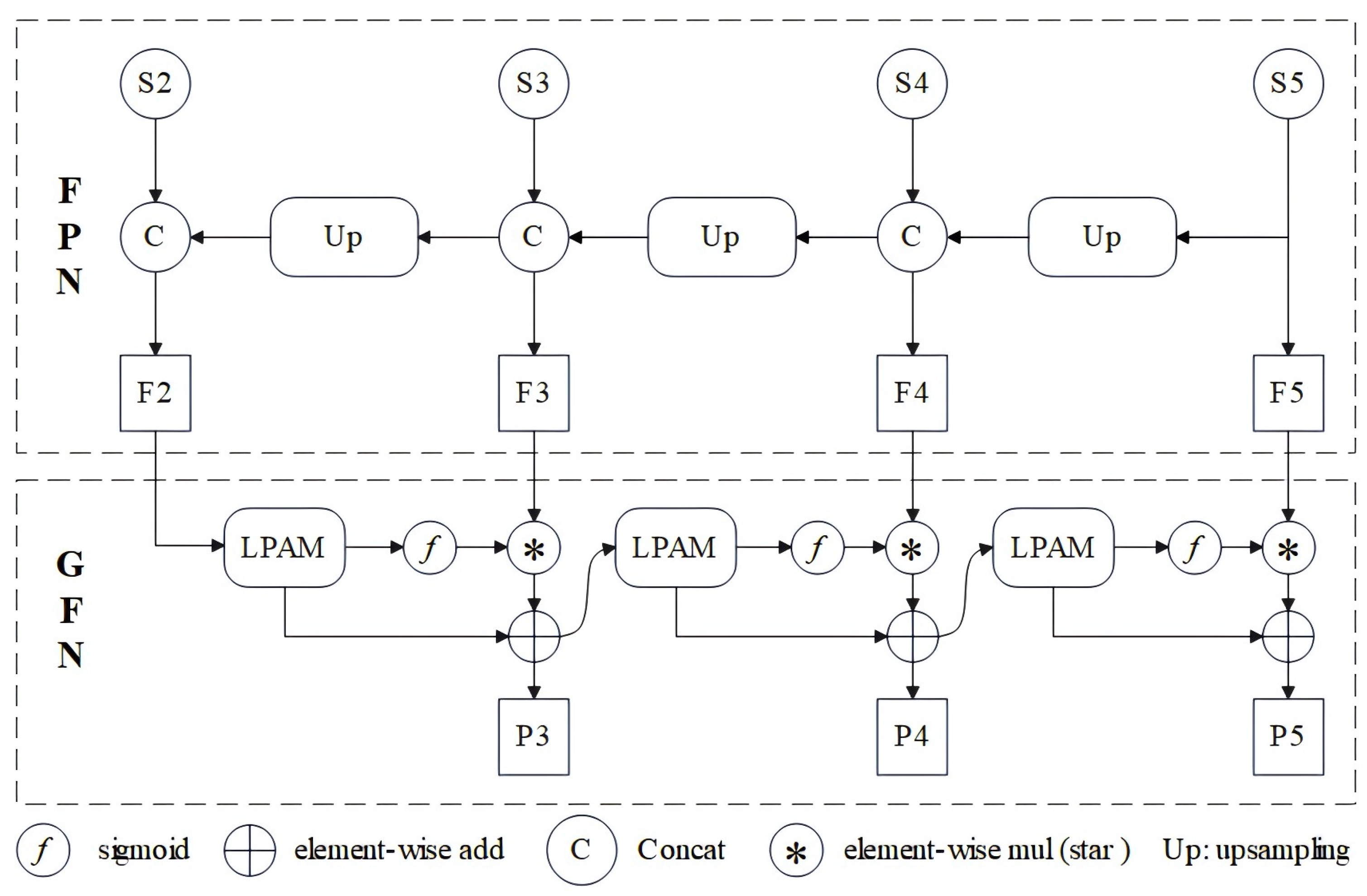

- This paper proposes GF-FPN to enhance small object detection performance. Built upon the original FPN, the network incorporates a bottom-up guided focus mechanism: via a pyramidal attention module, the star operation, and residual connections, it establishes correlations between objects and local contextual information, as well as between shallow detail features and deep semantic features. This allows the feature pyramid network to focus on critical features and enhance the ability to discriminate between objects and backgrounds, thereby boosting the model’s small object detection performance.

- 2.

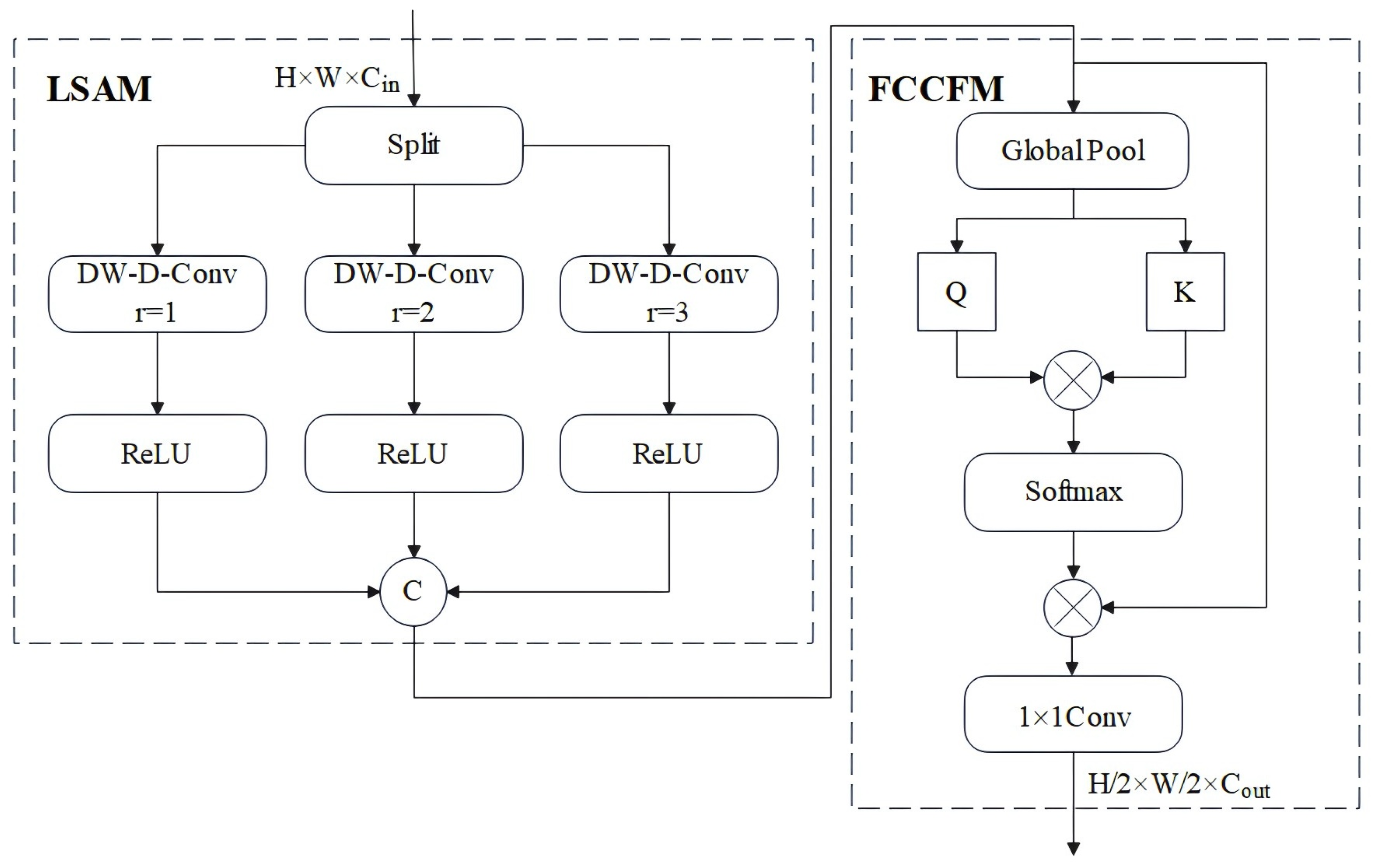

- This paper designs LPAM, which establishes the correlation between objects and local contextual information through a local spatial attention module(LSAM) and a full-channel correlation fusion module (FCCFM), enhancing the feature discrimination ability.

- 3.

- This paper designs FCCFM, which constructs a correlation matrix between channels through a global descriptor and a self-attention mechanism, dynamically captures the correlation between channels, and realizes the fusion of full-channel spatial features.

2. Materials and Methods

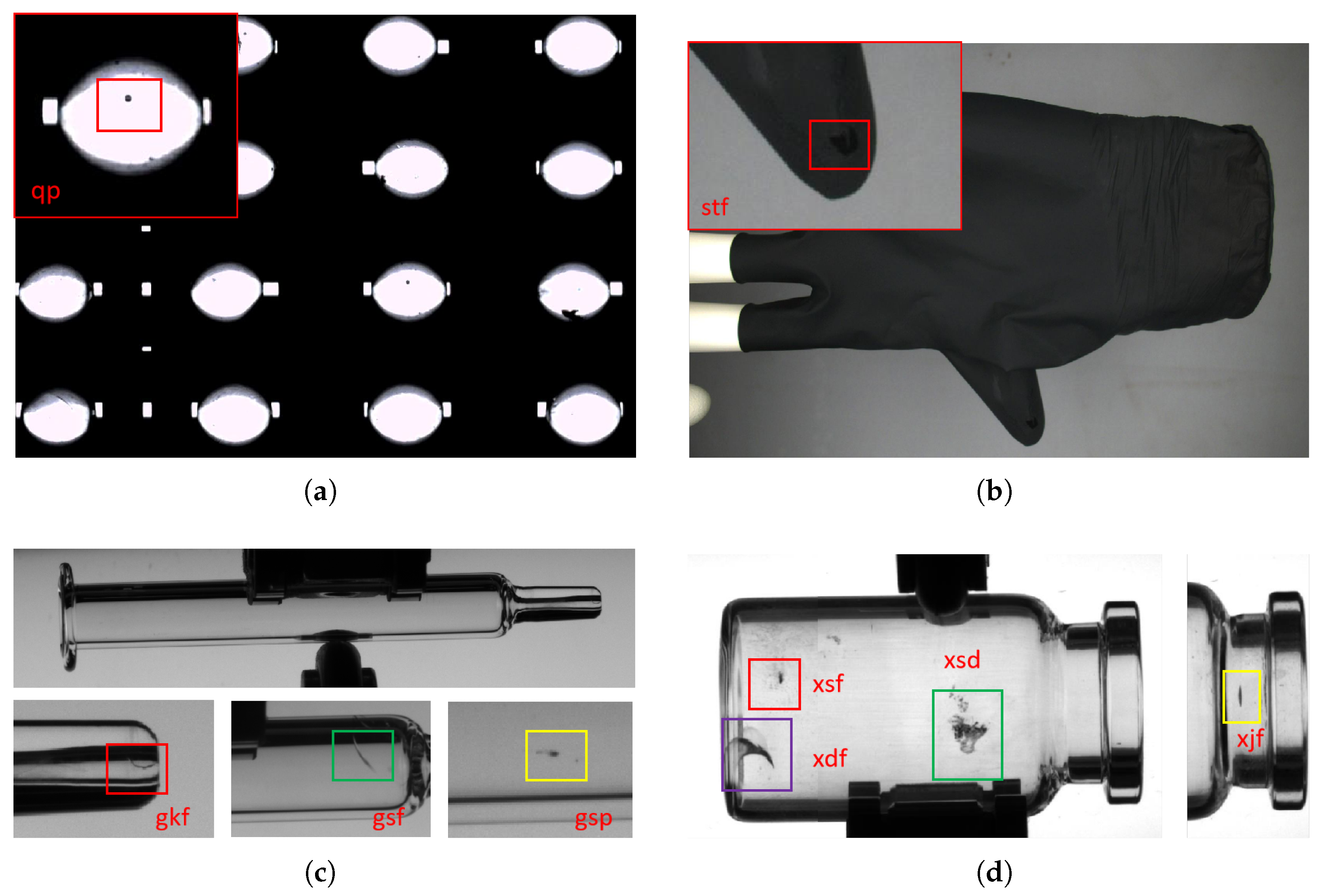

2.1. Dataset

2.2. The Proposed Model

2.2.1. The Architecture of LPAM

2.2.2. LPAM Parameter Analysis

- 1.

- LSAM

- Depthwise dilated convolution (2D, kernel = , dilation rate r is 1, 2, and 3, respectively):

- ○

- Number of parameters for a single branch: ;

- ○

- Total number of parameters for three branches: .

- Pointwise convolution (2D, kernel = ):

- ○

- Number of parameters for a single branch: ;

- ○

- Total number of parameters for 3 branches: .

- 2.

- FCCFM

- Q/K fully connected layers: Map the feature after GlobalPool to dimension d.

- ○

- Number of parameters for a single fully connected layer: ;

- ○

- Total number of parameters for Q and K: ;

- 1 × 1 Conv: Input channels , output channels , number of parameters: .

- 3.

- Total Number of Parameters

2.2.3. Guided Aggregation Network

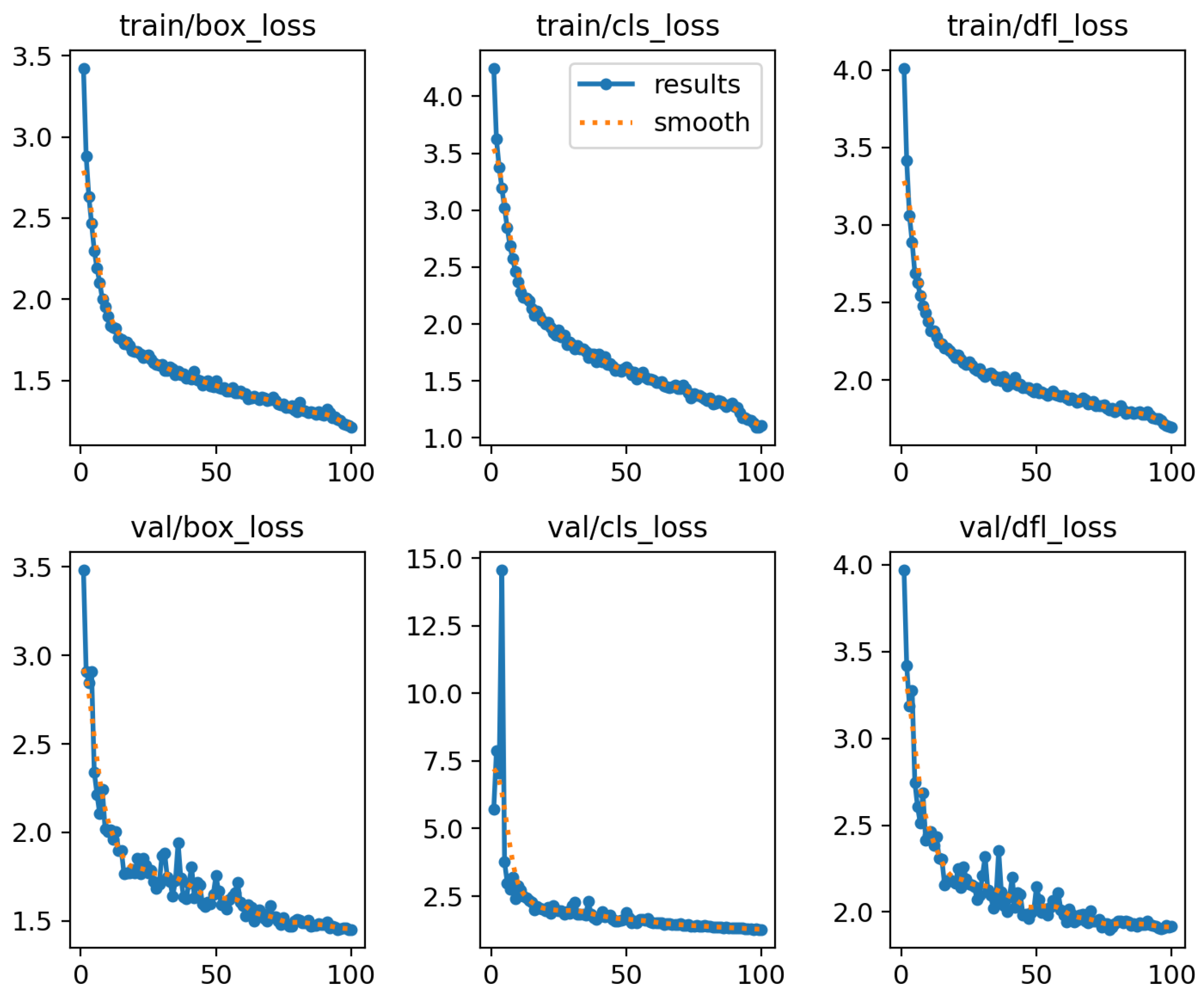

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experiment Setup

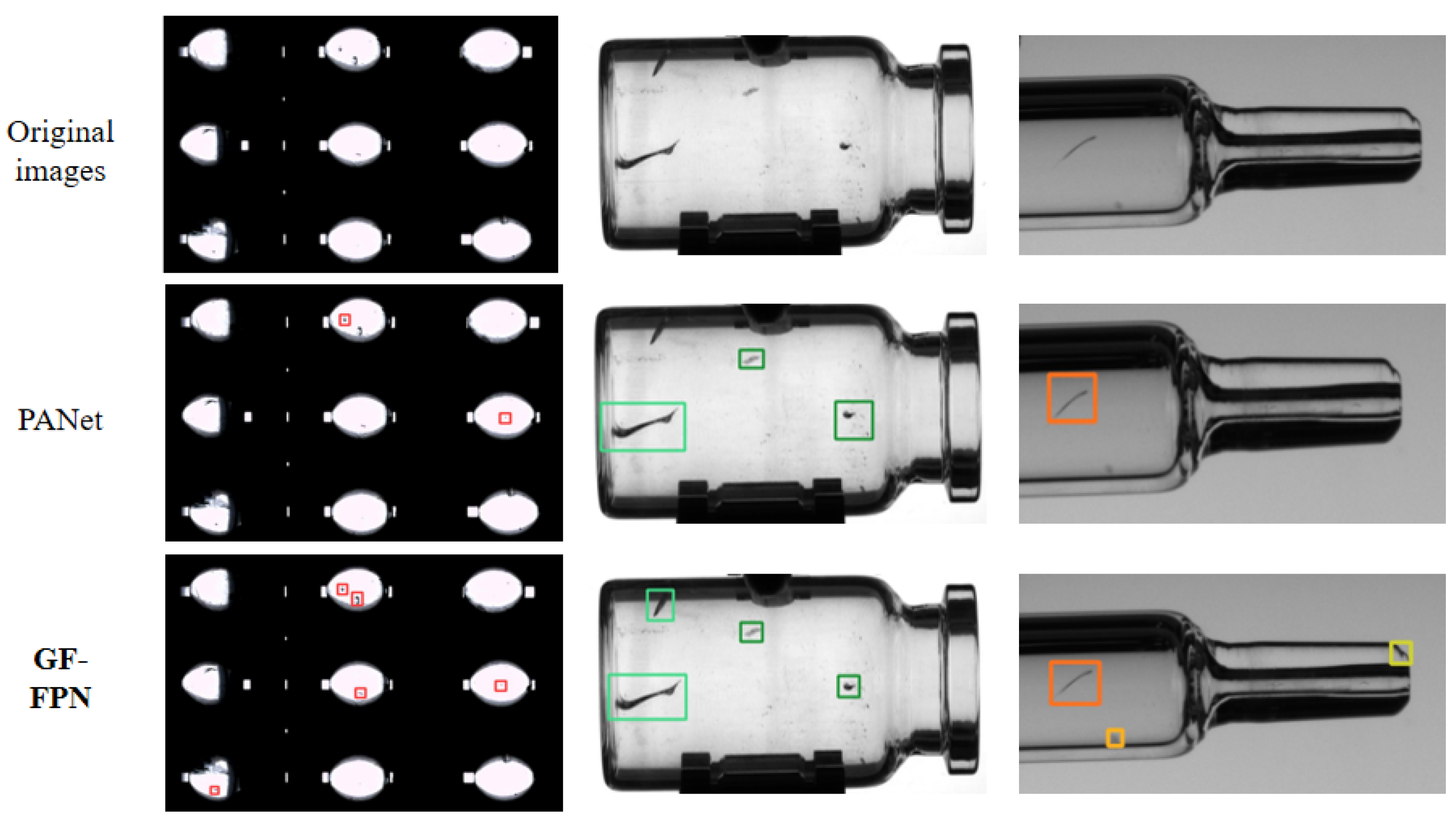

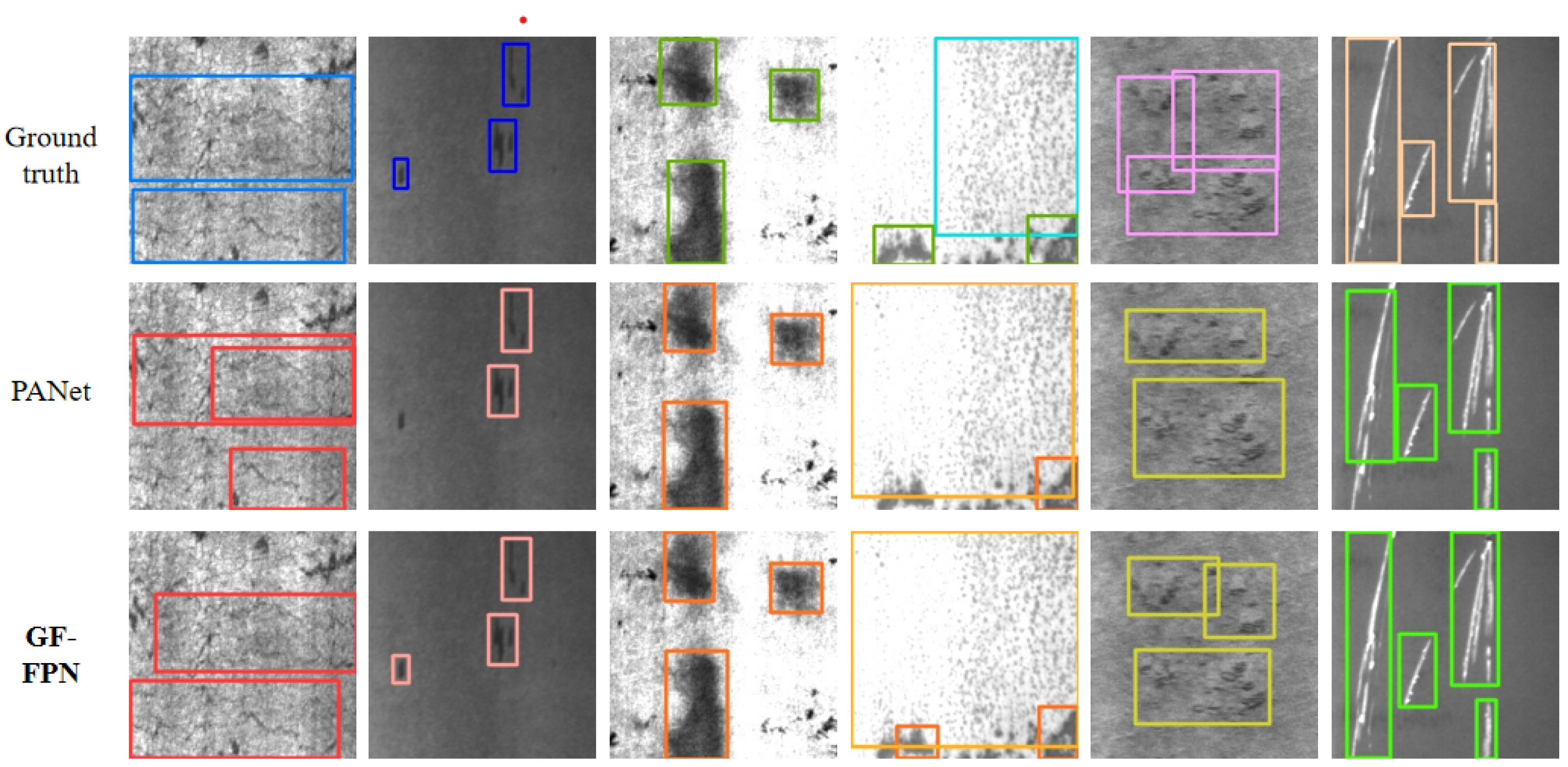

3.2. Comparison with Different Feature Pyramid Networks

3.3. Learnable Parameters and Computational Cost

3.4. Ablation Studies

3.5. Limitations and Future Work

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiao, Q.; Hu, H.; Ahmad, A.; Wang, K. A review of metal surface defect detection technologies in industrial applications. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 48380–48400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chu, M.; Gong, R.; Zheng, Z. Global attention module and cascade fusion network for steel surface defect detection. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 158, 110979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Ren, Z.; Mi, T.; Zhou, S. IFIFusion: A independent feature information fusion model for surface defect detection. Inf. Fusion 2025, 120, 103039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Bai, L.; Yang, J. SmallNet: A small defects detection network for magnetic chips based on context-weighted aggregation and feature multiscale loop fusion. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 10095–10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammul, M.; Li, X. Comprehensive review of deep learning-based tiny object detection: Challenges, strategies, and future directions. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2025, 67, 3825–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Hu, J.; Ren, J.; Ye, H.; Yuan, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Guo, J. HS-FPN: High frequency and spatial perception FPN for tiny object detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; pp. 6896–6904. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, G.; Jin, Y.; Ma, H. Cross-layer feature pyramid transformer for small object detection in aerial images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ma, Y.; Gong, Z.A.; Cao, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. R-AFPN: A residual asymptotic feature pyramid network for UAV aerial photography of small targets. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Wu, P.; Zeng, N. A lightweight surface defect detection framework combined with dual-domain attention mechanism. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Qi, G.; Hu, G.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, X. Remote sensing micro-object detection under global and local attention mechanism. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhen, J.; Kang, Y.; Cheng, Y. Adaptive downsampling and scale enhanced detection head for tiny object detection in remote sensing image. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, J.; Lin, H.; Ma, C.; Fang, L.; Yang, X. Sparseformer: Detecting objects in hrw shots via sparse vision transformer. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 4851–4860. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, F.; Guo, J. LKR-DETR: Small object detection in remote sensing images based on multi-large kernel convolution. J. Real Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Yang, Z.; Yang, G.; Li, K.; Yang, Z.; An, J. Super Mamba feature enhancement framework for small object detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Song, K.; Meng, Q.; Yan, Y. An end-to-end steel surface defect detection approach via fusing multiple hierarchical features. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 69, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Meng, F. Improved object detection via large kernel attention. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 240, 122507. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, C.; Dai, X.; Gao, J. Focal modulation networks. NeurIPS 2022, 35, 4203–4217. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lim, S.N.; Lu, J. Hornet: Efficient high-order spatial interactions with recursive gated convolutions. NeurIPS 2022, 35, 10353–10366. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Dai, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y. Rewrite the stars. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 5694–5703. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Guo, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, W. CFANet: Efficient detection of UAV image based on cross-layer feature aggregation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Lei, J.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, S.; Feng, Z.; Liang, R. AFPN: Asymptotic feature pyramid network for object detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Hawaii, NA, USA, 3–7 October 2023; pp. 2184–2189. [Google Scholar]

| Model | Attention Type | Key Contribution | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FPN [6] | no attention module | top-down fusion, lateral connections | insufficient transmission of semantic information |

| PANet [7] | no attention module | added bottom-up path aggregation | no weight mechanism |

| BiFPN [8] | no attention module | proposed weighted bidirectional fusion, pruned invalid fusion nodes | the weighting mechanism relies on hyperparameter tuning |

| CFPT [10] | cross-layer spatialwise attention (CCA) and cross-layer spatialwise attention (CSA) | upsampler-free, global contextual information | lack of attention to local contextual information |

| GF-FPN (ours) | local spatial attention module (LSAM) and full-channel correlation fusion module (FCCFM) | bottom-up guided focus network, attention to local contextual information | none observed |

| Defects | Code Name | Instances |

|---|---|---|

| bottle neck flaw | xl-j-flaw (xjf) | 134 |

| bottle body flaw | xl-s-flaw (xsf) | 119 |

| bottle body dirty | xl-s-dirty (xsd) | 172 |

| bottle bottom flaw | xl-d-flaw (xdf) | 76 |

| tube body flaw | gs-flaw (gsf) | 175 |

| tube mouth flaw | gk-flaw (gkf) | 254 |

| tube body pock | gs-pock (gsp) | 228 |

| ball pock | q-pock (qp) | 362 |

| glove flaw | st-flaw (stf) | 166 |

| Model | mAP50 | mAP50-95 | xjf | xsf | xsd | xdf | gsf | gsp | gkf | qp | stf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darknet53 + FPN | 58.9 | 19.8 | 67.6 | 94.6 | 79.2 | 38.0 | 76.0 | 48.6 | 14.6 | 49.3 | 62 |

| CSPDarknet + FPN | 60.2 | 21.1 | 64 | 95.7 | 82.1 | 43.9 | 79.4 | 56.0 | 13.1 | 43.2 | 64.4 |

| Darknet53 + PANet | 61.6 | 21.9 | 69.7 | 99.5 | 81.5 | 58.8 | 67.2 | 44.1 | 18.2 | 49.4 | 66.4 |

| CSPDarknet + PANet | 61.8 | 23.8 | 67.3 | 98.8 | 80.0 | 44.9 | 78.6 | 61.6 | 14.8 | 41.3 | 69.1 |

| Darknet53 + GF-FPN | 66.3 | 25.3 | 79.8 | 99.5 | 87.4 | 60.3 | 79.2 | 47.7 | 20.4 | 51.3 | 70.7 |

| CSPDarknet + GF-FPN | 69.9 | 26.4 | 77.7 | 99.5 | 89 | 60.9 | 84.9 | 63.0 | 33.1 | 46.2 | 74.6 |

| Model | mAP50 | mAP50-95 | Crazing | Inclusion | Patches | Pitted-Surface | Rolled-Inscale | Scratches |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darknet53 + FPN | 72.7 | 39.3 | 39.6 | 78.9 | 91.4 | 76.6 | 61.9 | 87.6 |

| CSPDarknet + FPN | 71.2 | 36.4 | 35.5 | 77.0 | 92.6 | 76.0 | 57.2 | 89.1 |

| Darknet53 + PANet | 73.6 | 42.1 | 44.6 | 79.7 | 91.5 | 76.4 | 59.5 | 89.9 |

| CSPDarknet + PANet | 74.1 | 42.2 | 41.9 | 79.0 | 93.0 | 78.4 | 61.9 | 90.4 |

| Darknet53 + GF-FPN | 74.9 | 43.4 | 45.5 | 80.0 | 93.1 | 79.2 | 60.5 | 91.1 |

| CSPDarknet + GF-FPN | 76.9 | 43.8 | 47.1 | 82.1 | 93.3 | 81.8 | 63.8 | 93.6 |

| Model | Backbone | FPS | Params (M) | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPN | CSPDarknet | 65.8 | 40.7 | 158.4 |

| PANet | CSPDarknet | 62.9 | 46.2 | 182.6 |

| BiFPN | CSPDarknet | - | 46.8 | 188.3 |

| AFPN [27] | CSPDarknet | - | 58.5 | 224.8 |

| GF-FPN | CSPDarknet | 64.2 | 41.7 | 166.9 |

| Backbone | Element-Wise Mul (Star) | Element-Wise Add | Residual Connection | mAP50 | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSPDarknet + GF-FPN | √ | √ | 69.9 | 166.9 | |

| CSPDarknet + GF-FPN | √ | √ | 68.2 | 166.9 | |

| CSPDarknet + GF-FPN | √ | 66.7 | 168.5 | ||

| CSPDarknet + GF-FPN | √ | 65.1 | 168.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Cheng, Y. A Cross-Scale Feature Fusion Method for Effectively Enhancing Small Object Detection Performance. Information 2026, 17, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010025

Kang Y, Zhang Y, Ren Y, Cheng Y. A Cross-Scale Feature Fusion Method for Effectively Enhancing Small Object Detection Performance. Information. 2026; 17(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Yaoxing, Yunzuo Zhang, Yaheng Ren, and Yu Cheng. 2026. "A Cross-Scale Feature Fusion Method for Effectively Enhancing Small Object Detection Performance" Information 17, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010025

APA StyleKang, Y., Zhang, Y., Ren, Y., & Cheng, Y. (2026). A Cross-Scale Feature Fusion Method for Effectively Enhancing Small Object Detection Performance. Information, 17(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010025