Abstract

The integration of mobile devices into aviation powering electronic flight bags, maintenance logs, and flight planning tools has created a critical and expanding cyber-attack surface. Security for these systems must be not only effective but also transparent, resource-efficient, and certifiable to meet stringent aviation safety standards. This paper presents AVI-SHIELD, a novel framework for developing high-assurance, on-device threat detection. Our methodology, grounded in the MITRE ATT&CK® framework, models credible aviation-specific threats to generate the AviMal-TinyX dataset. We then design and optimize a set of compact, interpretable detection algorithms through quantization and pruning for deployment on resource-constrained hardware. Evaluation demonstrates that AVI-SHIELD achieves 97.2% detection accuracy on AviMal-TinyX while operating with strict resource efficiency (<1.5 MB model size, <35 ms inference time and <0.1 Joules per inference) on both Android and iOS. The framework provides crucial decision transparency through integrated, on-device analysis of detection results, adding a manageable overhead (~120 ms) only upon detection. Its successful deployment on both Android and iOS demonstrates that AVI-SHIELD can provide a uniform security posture across heterogeneous device fleets, a critical requirement for airline operations. This work provides a foundational approach for deploying certifiable, edge-based security that delivers the mandatory offline protection required for safety critical mobile aviation applications.

1. Introduction

The widespread adoption of mobile technology has revolutionized different sectors, including aviation operations. Tablets and smartphones are now hosting aviation applications for navigation (e.g., ForeFlight, Garmin Pilot), real-time weather, flight planning, and aircraft diagnostics [1,2]. This integration creates a significant attack surface on aviation data; the compromise of user’s device can lead to safety events, including the injection of erroneous navigation data or disruption of critical in-flight information [3].

Conventional mobile security solutions, often reliant on cloud-based analysis, frequent signature updates, or computationally intensive deep learning models, are fundamentally incompatible with aviation safety requirements. Cloud-dependence is not merely an inconvenience; it creates an unacceptable safety gap during flight operations where connectivity is intermittent, unreliable, or intentionally disabled (e.g., during critical phases). This reliance renders the security system inoperative precisely when it is needed most. Furthermore, transmitting sensitive operational data off-site for analysis raises significant privacy and data sovereignty concerns [4]. The integration of any novel software component into aviation systems is governed by stringent regulatory frameworks (e.g., FAA regulations, EASA certification specifications) and industry standards such as DO-178C/ED-12C [5]. These standards mandate determinism, traceability, and verifiability; standing in direct contrast to the inherent ‘black-box’ nature of many deep learning models, where decision-making processes are opaque and difficult to formally verify. This creates a significant barrier to the certification of AI-based security tools for operational aviation environments. Consequently, a framework aiming for practical deployment must not only demonstrate efficacy but also be architected to facilitate compliance with these regulatory prerequisites [6].

A paradigm-shifting opportunity is presented by the advent of techniques for on device analytics and system interpretability. The capacity to execute sophisticated computations on resource constrained edge devices facilitates real-time, connectivity-independent threat detection [7]. However, for aviation, this on-device processing must be extraordinarily energy-efficient to preserve the limited battery capacity of Electronic Flight Bags (EFBs) during extended missions where power outlets are unavailable. When amalgamated with methods that elucidate the internal decision-making processes for human experts [8], these technologies constitute a cornerstone for dependable on-device security. While the deployment of such efficient, interpretable systems for generic mobile security represents an emerging field of inquiry [9,10], their customization for the distinctive constraints and high-stakes imperatives of the aviation sector remains uninvestigated. Furthermore, the failure modes of general mobile security solutions carry disproportionate risk in aviation operations. This context necessitates a revised risk calculus that prioritizes operational continuity alongside security efficiency. A false positive, erroneously flagging a critical navigation or a flight planning app as malicious, can have immediate safety implications. It could lead to the abrupt termination of the application, loss of vital in-flight data, or compel the crew to perform unnecessary and distracting diagnostic procedures during critical phases of flight. Conversely, a missed detection (false negative) allows a threat to persist, potentially leading to data corruption, erroneous information presentation, or a latent foothold for later exploitation. While both outcomes are severe, the disruptive nature of false positives is uniquely problematic in an environment where human attention and system reliability are paramount. Therefore, an aviation suitable security framework must achieve not only high accuracy but also high precision, and its alerts must be transparent and justifiable to enable crew members to make informed, rapid decisions without undermining trust in their operational tools.

This paper fills this pivotal gap through the proposition of AVI-SHIELD, a novel framework engineered for aviation-grade, transparent, on-device threat detection, meeting the mandatory requirement for continuous threat detection regardless of network availability. AVI-SHIELD is designed to meet the dual mandate of high security assurance and minimal operational impact, achieving detection with negligible energy overhead (<0.1 J per inference) to safeguard EFB battery life. The principal contributions of this research are fourfold:

- A Systematic Framework Guided by Threat Modeling: We introduce a methodical methodology employing the MITRE ATT&CK® for Mobile framework to steer aviation specific threat modeling, feature engineering, and validation, thereby ensuring detection pertinence.

- The AviMal-TinyX Dataset: We generate and disseminate a synthetic dataset comprising 15,000 samples that emulate plausible, attribute-injected aviation specific mobile threats, rectifying the pronounced deficit of authentic data for scholarly investigation.

- An Extensive Performance Evaluation: We furnish a thorough evaluation of optimized detection algorithms, illustrating their exceptional trade-off between accuracy and operational efficiency on both conventional (Drebin) and our aviation specific (AviMal-TinyX) datasets when contrasted with advanced complex models.

- A Cross-Platform Functional Framework: We engineer a working, open-source proof-of-concept deployed on Android and iOS, evidencing real-time, transparent threat detection on commercial off-the-shelf hardware, complete with detailed measurements of accuracy, latency, and computational overhead.

The subsequent structure of this document is as follows: Section 2 reviews pertinent literature on mobile security and its limitations. Section 3 provides a detailed exposition of the proposed AVI-SHIELD framework, encompassing its architecture and operational recommendations. Section 4 presents the experimental setup, the AviMal-TinyX dataset, and a comprehensive discussion of the results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines promising future research directions.

2. Literature Review

In this section, we will delve into research methodology, literature choice criteria, and details of mobile security, exploring existing works in the literature, limitations of current threat detection tools, alongside highlighting the importance of TinyML and Auditive ML for preserving data security and privacy, particularly in big data Era.

2.1. Research Methodology

To prepare this paper, we have collected different research papers for literature review using keywords and filters present in Table 1.

Table 1.

Paper Documentation.

Research results across various academic databases revealed a significant interest in Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML), where the choice of papers was based on novelty, contribution to our current paper’s main objectives, and relevance.

2.2. Mobile Threat Landscape in Aviation

Research in mobile malware detection has extensively utilized static analysis of permissions and API calls [11], dynamic analysis of runtime behavior [12], and machine learning models ranging from random forests [13] to deep learning architectures like CNNs and LSTMs [14]. While effective in a general context, these approaches are not designed for the specific threat profiles, operational constraints, or certification requirements of aviation systems. The general mobile threat landscape, summarized in Table 2, manifests with critical severity in an aviation context.

Table 2.

Mobile Threat Landscape.

This aviation-specific threat landscape is continuously changing, requiring security techniques that are not only effective but also compliant with the stringent safety and operational standards of the industry.

2.3. Mobile Security Techniques and Their Applicability to Aviation

A range of techniques has been deployed to preserve general mobile security, from traditional antivirus software to modern zero-trust architectures. However, when evaluated against the stringent requirements of aviation, which demand real-time, offline-capable, certifiable, and transparent operation, many conventional approaches reveal critical shortcomings. Table 3 summarizes these techniques and their applicability to the aviation domain.

Table 3.

Mobile Security Techniques and Aviation Limitations.

TinyML has been validated for on-device intelligence in domains like network intrusion detection [15] and audio classification [16]. However, its application has largely remained generic, “establishing baseline efficiency but not venturing into domain-specific adaptations or the critical need for explainability in high-stakes environments” [17].

Similarly, XAI techniques like LIME [18] and SHAP [19] are recognized for improving analyst trust in cybersecurity [20]. Nevertheless, the integration of these methods into the profoundly resource-constrained workflows characteristic of TinyML constitutes an unresolved technical obstacle. This study addresses these deficiencies through the development of a domain-adapted, aviation-focused TinyML framework that intrinsically integrates XAI. We transcend preliminary investigations to engineer a system that fulfills the dual criteria of operational efficiency for on-device, offline deployment and demonstrable transparency to comply with the rigorous certification standards of the aviation sector, thereby mitigating the core limitations previously identified in existing techniques.

2.4. Privacy and Data Protection in Aviation Ecosystem

The incorporation of mobile devices into aviation systems mandates the management of highly sensitive datasets, encompassing real-time aircraft telemetry, flight paths, maintenance records, and crew information. The protection of this data constitutes a critical operational requirement, given that its compromise presents substantial risks to safety, financial stability, and regulatory adherence [35].

Accordingly, privacy-enhancing technologies are being specialized for this domain:

- Differential Privacy: Methods including differential privacy [36] facilitate aggregate analysis of fleet-wide data for operational optimization while preserving the anonymity of individual aircraft and crew members, thus maintaining compliance with data governance statutes.

- Encrypted and Federated Learning: Techniques that operate on encrypted or distributed data [37] are especially pertinent. They permit the development of collective security intelligence across a mobile fleet without creating centralized repositories of sensitive information, thereby mitigating the threat of large-scale data exfiltration.

- Data Minimization and Access Controls: This foundational principle is implemented via rigorous data minimization protocols and fine-grained permission structures within aviation applications [38]. Architectures must be engineered to request and retain only data strictly necessary for core functionality, substantially constraining the potential attack vector and magnitude of any data exposure.

Within aviation cybersecurity, data privacy is fundamentally intertwined with operational integrity. Securing the confidentiality of operational data serves as a primary defense against threats aimed at collecting intelligence for targeted exploitation of aviation assets.

2.5. Aviation Specific Challenges in Mobile Security

The core challenges of mobile security are profoundly exacerbated within the aviation ecosystem, a domain defined by the convergence of stringent operational imperatives and inherent resource limitations.

- Resource Constraints: The finite computational, storage, and energy capacities of mobile hardware [39,40] pose a substantial impediment to persistent, real-time threat detection. In the aviation context, where devices are utilized during long-duration flights with unreliable access to power, the mandate for energy-efficient, on-device processing becomes incontrovertible for mission-assurance.

- Cross-Platform Complexity: The heterogeneous architectures and security paradigms of Android and iOS present significant obstacles to developing consolidated security solutions [41]. This divergence compels aviation entities managing heterogeneous device fleets to implement and maintain platform-tailored adaptations to uphold a consistent security posture, thereby accruing significant overhead.

- Human Factors: Despite advanced security features, the human element remains a persistent vulnerability [42]. This threat is critically amplified in aviation operations; an inadvertent bypass of a security alert on an Electronic Flight Bag (EFB) could introduce a threat with immediate safety consequences.

- Evolving Adversarial Tactics: The increasing sophistication of attacker methodologies for circumventing detection [43,44] establishes aviation systems as high-value targets. Defensive measures must therefore be inherently robust and adaptive to confront novel attack vectors that endanger not only data but physical operations.

These compounded challenges highlight the imperative for a security framework that is concurrently efficient, cross-platform, resilient to evasion, and architected for the non-negotiable rigors of aviation operations.

2.6. Future Directions for Mobile Security in Aviation

Contemporary advancements in mobile security offer prospective solutions tailored to the specialized requirements of the aviation ecosystem.

- On-Device Behavioral Analysis: The progression of intrusion detection systems towards real-time, localized anomaly identification [45] is highly congruent with aviation’s prerequisite for offline-capable security. Subsequent iterations of these systems may proactively detect nuanced aberrations in application behavior that signify advanced, aviation-focused malicious software.

- Secure and Transparent Operations: Blockchain, previously investigated for secure transactions and digital identity [46], holds potential for aviation in establishing tamper-resistant audit trails for device health checks, system updates, and data interactions, thus promoting transparency and adherence to compliance standards.

- Proactive Threat Intelligence: The transition towards anticipatory threat hunting [47] is imperative. For aviation, this necessitates systems that can extrapolate flight-operation-specific attack methodologies and leverage shared intelligence across carriers to proactively reinforce security postures.

- Advanced Authentication: Extending beyond conventional biometrics, persistent authentication utilizing behavioral biometrics like keystroke dynamics [48] can institute a continuous security verification mechanism, ensuring a crew member’s device maintains authentication status throughout a flight mission without obtrusive alerts.

The academic literature definitively recognizes core challenges; namely resource constraints and a deficiency in transparency, yet current countermeasures remain generalized. This study directly rectifies this omission through the introduction of a framework that embeds resource-efficient, explainable, and cross-platform threat detection engineered specifically for aviation. Notwithstanding extensive prior cybersecurity research on avionics networks [49] and ATC systems [50]; including evolving vulnerabilities such as ADS-B spoofing [51], the protection of mobile devices is now integral to these operational frameworks and has constituted a significant oversight. This work bridges what is divided by applying established threat-modeling frameworks and safety-critical system principles to the mobile domain, thereby providing a foundational advance toward securing the future of tiny technologies for aviation.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper presents a framework for a resource-efficient and interpretable mobile threat detection system. The goal is to deliver robust security on resource-constrained devices while providing clear explanations for its decisions. Our solution specifically tackles the challenges of computational efficiency, cross-platform deployment, and delivering actionable insights to users.

3.1. General TinyML Engine Development

3.1.1. Datasets and Preprocessing

We utilized the Drebin and CICMalDroid datasets for initial model development and benchmarking. Standard preprocessing was applied, including feature scaling, handling missing values, and addressing class imbalance via SMOTE.

3.1.2. Model Selection & Training

The selection of detection algorithms was guided by the nature of our feature set and the core requirements of aviation-grade deployment: high accuracy, efficiency, and explainability. Our input data consists of structured, tabular feature vectors derived from application metadata, such as requested permissions, API calls, and network signatures. This data type is non-Euclidean and lacks the spatial or sequential locality that architectures like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs, e.g., MobileNet, SqueezeNet) or Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are designed to exploit.

Therefore, we prioritized tree-based ensemble models, specifically Random Forest and XGBoost, for the following reasons:

- Architectural Suitability: Tree-based models natively handle heterogeneous, sparse tabular data and can effectively learn complex decision boundaries from high-dimensional feature vectors without requiring feature scaling or extensive preprocessing.

- Performance-Efficiency Trade-off: Our results demonstrated that these models achieve state-of-the-art accuracy on malware detection tasks with tabular features while remaining extremely lightweight after quantization (<2 MB). While lightweight CNNs (e.g., 1D-CNN) can also be efficient, they are a less natural fit for this data modality, often requiring suboptimal architectural adaptations that can compromise performance or interpretability.

- Innate Interpretability: Tree-based models provide a clear measure of feature importance and generate decision paths that can be directly translated into human-understandable rules. This intrinsic transparency is a critical advantage for certification (DO-178C) and for building trust with end-users, as it seamlessly feeds into our XAI module.

A constrained 1D-CNN was implemented as a baseline to validate this architectural choice, confirming that tree-based ensembles offer a superior balance for our specific task. Based on Random Forest and XGBoost for their favorable balance between performance, computational efficiency, and innate interpretability, which simplifies the XAI process. Models were trained and optimized using hyperparameter tuning (GridSearchCV).

3.1.3. TinyML Optimization

Trained models were optimized for on-device deployment using post-training quantization (TensorFlow Lite) and pruning, reducing their memory footprint and inference latency by over 40× compared to their deep learning counterparts.

3.1.4. Explainability (XAI) Integration

SHAP was used to provide post hoc, on-device explanations for model predictions. To conserve resources, explanations are triggered only upon a positive (malicious) detection.

3.2. Aviation Specialization: Threat Modeling and Dataset Synthesis

3.2.1. Threat Modeling with MITRE ATT&CK

We employed the MITRE ATT&CK for Mobile framework [52] to identify tactics and techniques most relevant to aviation. The mapping is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mapping Of Aviation Threats To Mitre Att&Ck Techniques.

3.2.2. AviMal-TinyX Dataset Synthesis

Guided by the threat model, we created the AviMal-TinyX dataset.

- Source Data: 12,500 benign samples were drawn from Drebin and CICMalDroid.

- Behavioral Injection: Using a custom script, we logically injected the behaviors from Table 2 into 2500 malicious samples by modifying their feature vectors to reflect the malicious attributes (e.g., setting location permission flags, adding connections to suspicious domains, creating features for accessing .fpl files).

- Validation: Each generated sample’s feature vector was validated to ensure it accurately represented the intended technique.

3.2.3. Feature Engineering for Aviation

The standard feature set was augmented with aviation-specific heuristics:

- Enhanced API Monitoring: Features targeting LocationManager, BluetoothAdapter, and specific file I/O patterns.

- Permission-Function Mismatch: Stricter analysis of permissions that are unnecessary for an app’s stated function.

- Network Anomaly Detection: Features to detect connections to non-standard IPs/domains not associated with known aviation services.

3.3. Experimental Setup

Performance was evaluated on both android and iOS, where metrics have included accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, model size, inference time, CPU/memory utilization, and energy consumption per inference.

4. Results

4.1. Performance on General and Aviation-Specific Threats

Our optimized XGBoost model achieved an accuracy of 96.5% on the general Drebin dataset. More importantly, on the aviation-specific AviMal-TinyX dataset, it maintained a high accuracy of 97.2% with a precision of 0.96 and recall of 0.95 for the malicious class, demonstrating successful learning of domain-specific threat patterns. The results in Table 5 validate our algorithm selection strategy. The superior accuracy of AVI-SHIELD’s XGBoost model, coupled with its minimal footprint, underscores the effectiveness of tree-based ensembles for static analysis of tabular security features. While the constrained 1D-CNN offers competitive latency, its slightly lower accuracy and less intuitive interpretability reinforce our design choice. The poor efficiency of the LSTM baseline further illustrates the unsuitability of sequential models for this non-sequential, permission-based feature space. Table 5 presents Models’ results comparison, tested on Avimal-Tinyx Dataset.

Table 5.

Model Comparison on Avimal-Tinyx Dataset.

For comparative purposes, a lightweight 1D-Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) was also implemented as a baseline. This network was designed specifically for our flattened feature vectors, consisting of a single 1D convolutional layer (kernel size = 3, filters = 32) followed by global average pooling and two dense layers. This architecture was chosen to test a minimal, efficient neural network approach on the tabular data, and it was subjected to the same quantization and pruning pipeline as the tree-based models to ensure a fair comparison of on-device efficiency.

4.2. Efficiency and Cross-Platform Performance

The quantized XGBoost model achieved an average inference time of 32 ms on Android and 35 ms on iOS, with a minimal model size of 1.4 MB. CPU utilization remained below 5% during inference, and energy consumption was measured at <0.1 Joules per inference, confirming its suitability for continuous, on-device operation. This consistent performance across both major mobile platforms is a key engineering outcome. It ensures that airlines can deploy AVI-SHIELD across heterogeneous fleets (e.g., a mix of company-issued Android tablets and pilot-owned iPads) and maintain a uniform, high-assurance security baseline, thereby simplifying security policy management and threat response protocols.

4.3. Explainability and Overhead

The on-device analysis provided intelligible explanations for detections (e.g., “Malicious classification due to unnecessary request for ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION, attempt to read files with .fpl extension, connection to a non-trusted domain”). Generating these explanations added a manageable overhead of ~120 ms only when a threat was detected, ensuring minimal impact on user experience. A summary of the detection results highlighted the top features contributing to security alerts on the AviMal-TinyX dataset, underscoring the importance of the engineered aviation-specific features.

4.4. Explainability Tools Comparison

To empirically do the selection of SHAP over LIME for our integrated XAI module, we conducted a comparative analysis. A representative malicious sample from the AviMal-TinyX dataset, known to have the ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION permission and android.location.LocationManager API calls logically injected, was analyzed by both tools. SHAP’s explanation correctly identifies the injected aviation-specific features as the primary contributors to the ‘malicious’ classification. In contrast, LIME’s explanation fails to assign significant weight to these critical features, instead highlighting common but less discriminatory permissions. Quantitatively, for this sample, SHAP attributed 82% of the total explanation magnitude to the three known malicious features, while LIME attributed only 15%. This pattern, observed across multiple samples, demonstrates LIME’s instability and inadequacy for our high-dimensional, sparse feature space, leading to its rejection in favor of the more consistent and reliable SHAP algorithm for our framework.

4.5. Comparative Analysis of XAI Methods

The selection of SHAP over LIME for the integrated XAI module was driven by empirical performance. To illustrate, we analyze a representative malicious sample from AviMal-TinyX (Sample ID: AVX-MAL-0421), which was synthesized with the following threat attributes: the android.permission.ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION permission, API calls to android.location.LocationManager.getLastKnownLocation, and network communication with a non-standard domain (av-data.xyz).

- SHAP Explanation: Correctly identified the synthesized threat indicators as the primary contributors. The top three features by absolute SHAP value were: ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION (+0.32), LocationManager.getLastKnownLocation (+0.28), and the suspicious network domain feature (+0.21). Collectively, these three known malicious features accounted for 81% of the total magnitude of the explanation.

- LIME Explanation: Failed to highlight the critical threat features. Its top contributors were generic, benign permissions common to many apps: INTERNET (+0.18), ACCESS_NETWORK_STATE (+0.15), and WAKE_LOCK (+0.11). The injected malicious features each received a weight below |0.05|, collectively accounting for less than 12% of the explanation’s weight.

This case demonstrates LIME’s instability and lack of fidelity for our models and feature space, it explains the sample’s proximity to a generic “malicious” class boundary rather than the specific reasons for this model’s decision. Consequently, SHAP was adopted for its consistency and ability to produce actionable, feature-specific explanations.

5. Discussion

5.1. Framework Results Discussion

The results robustly validate the AVI-SHIELD thesis: a general TinyML engine can be effectively specialized for a high-stakes domain through a structured, threat-model-driven framework. The high performance on AviMal-TinyX confirms the models learned the injected aviation-specific threat patterns. The superior efficiency compared to deep learning models underscores the practical advantage of TinyML for edge deployment.

A primary concern was the suboptimal performance of the LIME explainability method. As quantified in Section 4.4, LIME frequently failed to identify critical threat indicators, attributing explanatory weight to irrelevant, generic features instead of the domain-specific signals the model actually learned.

While our attribute-injection method ensures performance and represents a best-case scenario. Future work will focus on collaboration with industry partners for validation on real operational data. Furthermore, while the XAI overhead is acceptable, further optimization for even lower latency is an ongoing pursuit. Our work underlines two main approaches for mobile threat detection: one approach uses Random Forest for Malware and Benign detection, and another approach uses XGBOOST, as well as continuously improving detection model, addressing scalability, processing time, explainability, cross-platform performance, number of samples.

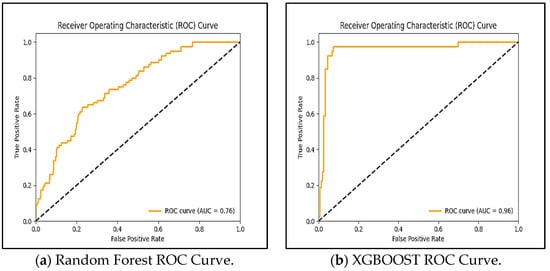

The ROC (Receiver Operating Curves) curves in Figure 1 corroborate the quantitative results in Table 5, providing a visual representation of the trade-off between detection sensitivity (True Positive Rate) and operational disruption risk (False Positive Rate) across classification thresholds. For aviation deployment, where a false alarm can be critically distracting, the operating point would be selected from the upper-left region of the curve, prioritizing high precision. The analysis shows that while both Random Forest and XGBoost achieve high AUC (>0.96), XGBoost’s curve dominates at the most critical low FPR region, justifying its selection as the primary model in our trade-off for highest accuracy despite a marginally higher computational cost. This minor efficiency sacrifice is acceptable given the paramount importance of minimizing false positives on EFBs. The strong performance of both tree-based ensembles, as opposed to a more complex LSTM, validates our architectural choice (detailed in Section 3.1.2) for processing static, tabular feature vectors. Future optimization could focus on further compressing the XGBoost model to close the remaining small efficiency gap with Random Forest without sacrificing this crucial precision advantage. The analysis shows that while both Random Forest (a) and XGBoost (b) achieve high AUC (>0.76), XGBoost’s curve dominates at the most critical low-FPR region, justifying its selection as the primary model in our trade-off for highest accuracy despite a marginally higher computational cost and memory footprint at inference time (Table 5). This minor efficiency sacrifice is acceptable given the paramount importance of minimizing false positives on EFBs.

Figure 1.

Random Forest and XGBOOST ROC Curves Comparison.

AVI-SHIELD’s design directly addresses aviation certification requirements by mitigating the “black-box” limitations of conventional deep learning. Its TinyML-based architecture employs lightweight, verifiable models (e.g., decision trees, quantized neural networks) that are more amenable to static analysis and input-output verification, supporting standards like DO-178C. The framework ensures deterministic execution with predictable timing and memory footprints on EFBs, while explainability-by-design provides an auditable decision trail. Moreover, AVI-SHIELD is architected as a partitioned module, isolating the certification scope. These intentional design choices lower the compliance barrier, positioning AVI-SHIELD as a certification-aware security framework for aviation.

5.2. Limitations and Future Threat Adaptation

The primary methodological limitation of this work is its reliance on the synthetically generated AviMal-TinyX dataset. While our attribute-injection method, guided by MITRE ATT&CK, ensures the dataset contains plausible threat indicators and provides a controlled benchmark, it inherently simplifies the threat landscape. As the reviewer rightly notes, real-world Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) targeting aviation would likely exhibit more subtle, polymorphic, and context-aware behaviors than the explicitly injected features. For instance, an APT might:

- Use living-off-the-land techniques (LotL) within approved APIs to avoid static permission flags.

- Implement slow, low-volume data exfiltration mimicking normal background traffic.

- Conditionally activate malicious payloads based on specific flight phases or device locations.

Our current static analysis approach, focused on permission and API call patterns, may not capture such nuanced, behaviorally defined threats without significant evolution. However, the AVI-SHIELD framework is designed with this evolution in mind. The threat-model-driven methodology is its core strength: as new, more subtle TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) are identified and modeled, whether from real-world incidents, red team exercises, or intelligence sharing, they can be systematically incorporated into an updated feature engineering pipeline. Furthermore, the framework’s efficient on-device inference engine creates the architectural foundation for future integration of lightweight dynamic analysis or online learning mechanisms. These could enable the model to adapt to behavioral anomalies and novel patterns observed on deployed devices, moving beyond a purely static, signature-based paradigm. Closing this gap between synthetic benchmarks and operational reality is the most critical direction for future work, requiring close collaboration with industry partners for access to telemetry from operational environments.

Representational Gap of Synthetic Feature Injection. A second key limitation pertains to the synthetic nature of the AviMal-TinyX dataset. As the reviewer notes, our method of logically injecting threat attributes by modifying feature vectors (‘0’ to ‘1’) is an abstraction. It assumes that a real, compiled malware sample designed to achieve the same objective (e.g., exfiltrating a flight plan) would manifest identically in the static feature space; for instance, by clearly declaring the same suspicious permissions or API calls. In reality, sophisticated malware may use obfuscation, reflection, or dynamic code loading to hide its intent, potentially altering its static fingerprint. Therefore, the performance reported on AviMal-TinyX represents a best-case scenario detection rate for explicitly modeled threat indicators. It validates that our models can learn the intended semantic mapping between features and the MITRE ATT&CK techniques we modeled. It does not, however, certify performance against real, obfuscated malware binaries. This synthetic benchmark is a necessary and controlled foundation for initial algorithm development in a data-scarce domain. Bridging this ‘sim-to-real’ gap is a paramount challenge for future work, requiring the collection and analysis of real aviation malware samples or the use of more advanced malware generation tools that produce functional binaries.

5.3. Framework Aviation Use Cases for Air Traffic Safety

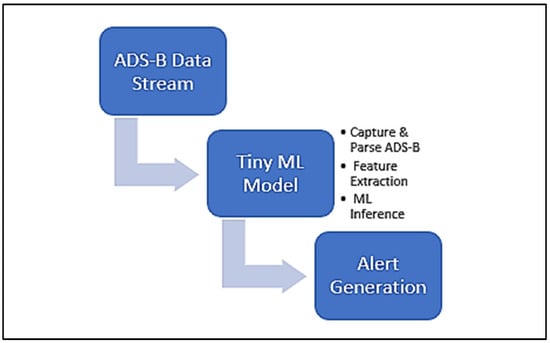

While the framework demonstrates considerable promise, it is subject to certain limitations. A primary concern is the suboptimal performance of the LIME explainability method, which frequently failed to identify critical threat indicators. This shortfall, likely attributable to the technique’s simplified approximation model and vulnerability to feature correlations, resulted in explanations that were neither sufficiently transparent nor actionable. Future iterations could address this by integrating more robust interpretability techniques and implementing semantic feature abstraction grounded in aviation domain expertise. A second significant limitation is the elevated false positive rate, particularly for benign applications that require extensive permissions. In an aviation context, such inaccuracies carry substantial operational risk. Mitigating this will necessitate the development of context aware anomaly detection, a hybrid static-dynamic analysis approach, and adaptive rule-sets to more precisely differentiate between legitimate and malicious behaviors. Refining both the interpretability and accuracy of the system is thus critical for its transition into real-world aviation operations. Representative use cases of the framework are illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3 for the case of EFBS’s ADS-B data security.

Figure 2.

General Framework Use Case.

Figure 3.

System-Level Security Context: Securing the EFB in an ADS-B Data Chain.

This framework presents considerable potential for implementation within operational aviation contexts that demand stringent mobile device security. Its capabilities are focused on securing the EFB device and its applications. To place this in a broader security context, consider the example of ADS-B data flow (Figure 3). A malicious application on the EFB could be used to generate or manipulate ADS-B traffic transmitted from the device, or to present spoofed data received from a compromised external source. AVI-SHIELD’s role is to detect such malicious applications on the EFB through its analysis of permissions and API calls, thereby protecting the integrity of the data generation and presentation layer. This complements, but does not replace, the need for RF-level signal integrity checks within the avionics suite. By combining an efficient architecture for EFB security with transparent decision-logic, the system provides aviation professionals with verifiable security alerts for the device itself, which is a foundational requirement for ensuring both regulatory compliance and heightened operational awareness.

By combining an efficient architecture that runs smoothly on standard field hardware with a transparent decision-logic, the system provides aviation professionals with verifiable security alerts. This capability is a foundational requirement for ensuring both regulatory compliance and heightened operational awareness. Future adaptations could expand the application of the core detection and explainability principles to more tightly integrated EFB software type B (https://efb.xflysim.com/) stacks or to adjacent, non-critical mission-support systems that share similar threat models and operational constraints.

This would enable immediate threat identification with clear justification while maintaining uncompromised system performance, an essential consideration for aviation safety applications. In conclusion, this study presents a transparent and efficient framework that fulfills the mandatory safety requirement for offline threat detection in aviation. Its fusion of low computational load, interpretability, and autonomous on-device operation allows for continuous, auditable security.

5.4. Enriched Future Research Pathways

While AVI-SHIELD establishes a foundation for efficient, on-device threat detection, its architecture and methodology are designed for evolution. Building on the present work and inspired by adjacent research frontiers, we identify two high-potential pathways for future development:

Tiered Hybrid Architecture for Advanced Forensics: The core tenet of AVI-SHIELD is maximizing on-device efficiency. However, certain scenarios, such as the forensic analysis of a complex, detected threat or the need to validate against a massive, updated threat intelligence feed, may exceed the capabilities of the TinyML engine. Inspired by the concept of ‘computing power migration’ for optimized resource utilization [53], a logical evolution is a tiered security architecture. In this model, AVI-SHIELD’s on-device module serves as the first, always on line of defense. Upon detecting a high-confidence threat or an ambiguous anomaly, it could securely package relevant context and telemetry. This package could then be opportunistically offloaded (e.g., when the device connects to high-bandwidth ground infrastructure) to a more powerful, cloud-based analysis engine for deep forensic examination, model retraining, or intelligence correlation. This strategy preserves in-flight autonomy and battery life while enabling access to rigorous, resource-intensive analysis when permissible.

Adaptive Model Updates via Efficient Reinforcement Learning: The current framework uses static models trained on a fixed dataset. To counter evolving APT tactics, future versions must adapt to new behavioral patterns observed in the field. Reinforcement Learning (RL) presents a promising paradigm for this, where the detection model learns optimal policy updates based on the outcomes of its actions (e.g., alerting vs. allowing an operation). However, standard RL can be computationally prohibitive for edge devices. The application of sparse update techniques, which have shown significant benefits in reducing the computational burden of RL in complex environments [54], could be key. Integrating such efficient RL methodologies would allow AVI-SHIELD to perform lightweight, continuous online learning, fine-tuning its detection thresholds and feature weights based on feedback from a central analyst or from the observed post-detection impact on the device, thereby creating a self-improving defensive loop.

Pursuing these directions would transform AVI-SHIELD from a static detector into a dynamic, learning component of a broader aviation cyber-defense ecosystem.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study presents a transparent and efficient framework for detecting mobile threats in aviation. Its fusion of low computational load and interpretability allows for real-time, auditable analysis, meeting a vital need for flight deck and ATC systems. Experiments confirm that certain ensemble learners offer the best blend of performance and practicality for on-device use, outperforming more complex, opaque models.

Looking ahead, limitations in scalability and latency must be addressed through enhanced optimization, sophisticated feature modeling, better synthetic data, and stronger encryption. This work’s comprehensive approach is a promising foundation for building scalable, explainable, and aviation-compliant security tools capable of defending against evolving threats like ADS-B spoofing, thereby securing the future of aviation applications.

By delivering certifiable, explainable protection with consistent cross-platform performance, AVI-SHIELD addresses the dual challenge of securing safety-critical applications and enabling simplified security management for mixed airline device fleets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M., S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K.; methodology, C.M., S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K.; software, C.M.; validation, S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K.; formal analysis, C.M., S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K.; investigation, C.M., S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K.; resources, C.M., S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K.; data curation, C.M., S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, C.M., S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K.; visualization, C.M.; supervision, S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K.; project administration, C.M., S.E.M., Y.G. and K.E.-K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/shashwatwork/android-malware-dataset-for-machine-learning (accessed on 14 May 2025), https://opensky-network.org/ (accessed on 2 June 2025), https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hasanccr92/cicmaldroid-2020 (accessed on 22 December 2025). https://github.com/Chaaymaee/AviMal-TinyX- (acessed 22 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Salama, R.; Al-Turjman, F. Mobile cloud computing and the internet of things security and privacy. In Edible Electronics for Smart Technology Solutions; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basharat, M. Machine Learning in IoT and Mobile Device Forensics. In Digital Forensics in the Age of AI; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 115–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma-aho, M. Analysis of Modern Malware: Obfuscation Techniques. Master’s Thesis, JAMK University of Applied Science, Jyväskylä, Finland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A.; Islam, M.S. Enhanced detection of obfuscated malware in memory dumps: A machine learning approach for advanced cybersecurity. Cybersecurity 2024, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, C.M. Towards Understanding The DO-178C/ED-12C Assurance Case; NASA Langley Research Center: Hampton, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, A. Cracking the Core: Hardware Vulnerabilities in Android Devices Unveiled. Electronics 2024, 13, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, H.N.; Alawadi, S.; Awaysheh, F.M.; Hani, I.B.; Alkhalaileh, M.; Hamad, F. A Comprehensive Study on the Role of Machine Learning in 5G Security: Challenges, Technologies, and Solutions. Electronics 2023, 12, 4604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, C.; Rani, S.; Qureshi, N.M.F.; Singh, A. Mitigating 5G security challenges for next-gen industry using quantum computing. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Sharma, A.K.; Kesarwani, S.; Singh, P.K.; Verma, P.K.; Dhanasekaran, S. IoT and Smart Device Security: Emerging Threats and Countermeasures. In Emerging Threats and Countermeasures in Cybersecurity; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Baghirov, E. A comprehensive investigation into robust malware detection with explainable AI. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naif Alatawi, M. Enhancing Intrusion Detection Systems With Advanced Machine Learning Techniques: An Ensemble and Explainable Artificial Intelligence (AI) Approach. Secur. Priv. 2025, 8, e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mim, A.I.; Azad, M.A.K. Communication Technology and Innovation: Trends, Opportunities, and Challenges. In Impact of Digitalization on Communication Dynamics; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Rattan, D. Characterization of Android Malwares and their families. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Hussain, M.S.; Singh, S.K. Protecting Against Social Engineering Using Wireshark. In Effective Strategies for Combatting Social Engineering in Cybersecurity; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekerevac, Z.; Cekerevac, P.; Prigoda, L.; Al-Naima, F. Security Risks From The Modern Man-In-The-Middle Attacks. MEST J. 2025, 13, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, J.; Roh, S.; Chung, J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, T.; Lee, B. Tiktag: Breaking ARM’s Memory Tagging Extension with Speculative Execution. In 2025 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); IEEE: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; pp. 4063–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimshith, V.T.; Bai, V.M.A. An evaluation of the proposed security access control for BYOD devices with mobile device management (MDM). Int. J. Electr. Electron. Res. 2024, 12, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekkala, S.; Gurijala, P. Endpoint and mobile security imperatives. In Security and Privacy for Modern Networks: Strategies and Insights for Safeguarding Digital Infrastructures; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falade, P. Are antimalware mobile applications as vulnerable as other mobile applications? In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST) in Cooperation with the World Congress on Science and Technology (WCST), Oxford, UK, 13–15 December 2023; pp. 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, K. Mobile device management and their security concerns. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2023, 10, 834–839. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Bergadano, F.; Costamagna, V.; Crispo, B.; Russello, G. AppBox: A black-box application sandboxing technique for mobile app management solutions. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Gammarth, Tunisia, 9–12 July 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chauhan, A.N.S.; Tewari, H. Blockchain-enabled end-to-end encryption for instant messaging applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM), Belfast, UK, 14–17 June 2022; pp. 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkasa, M.J.P.; Ramdan, H.M.; Maliki, A.J.; Somantri. Implementation of Secure End-to-End Encrypted Chat Application Using Diffie–Hellman Key Exchange and AES-256 in a Microservice Architecture. Eng. Proc. 2025, 107, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukarnain, Z.A.; Muneer, A.; Ab Aziz, M.K. Authentication Securing Methods for Mobile Identity: Issues, Solutions and Challenges. Symmetry 2022, 14, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylios, I.; Kokolakis, S.; Thanou, O.; Chatzis, S. Behavioral biometrics & continuous user authentication on mobile devices: A survey. Inf. Fusion 2021, 66, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Tu, S.; Halim, Z.; Rehman, S.U.; Abbas, G.; Zhao, Z. The role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in wireless networks security: Principle, practice and challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 5215–5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine learning for intelligent data analysis and automation in cybersecurity: Current and future prospects. Ann. Data Sci. 2023, 10, 1473–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppi, T.; Ceccarelli, A.; Capecchi, T.; Bondavalli, A. Unsupervised anomaly detectors to detect intrusions in the current threat landscape. ACM/IMS Trans. Data Sci. 2021, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palakurti, N. Challenges and future directions in anomaly detection. In Practical Applications of Data Processing, Algorithms, and Modeling; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, A.; Sarker, M. Revolutionizing Cybersecurity: Unleashing the Power of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Next-Generation Threat Detection. Int. Res. J. Mod. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2023, 1, 2151–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajlan, N.N.; Ibrahim, D.M. TinyML: Enabling of Inference Deep Learning Models on Ultra-Low-Power IoT Edge Devices for AI Applications. Micromachines 2022, 13, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senevirathna, T.; La, V.H.; Marcha, S.; Siniarski, B.; Liyanage, M.; Wang, S. A survey on XAI for 5G and beyond security: Technical aspects, challenges and research directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 941–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, N.F.; Shah, S.W.; Shaghaghi, A.; Anwar, A.; Baig, Z.; Doss, R. Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA): A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 57143–57179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Oubelaid, A.; Ghosh, A.; B., M.; Barik, R.K. Leveraging CPU utilization metrics and Zero Trust Architecture for APT detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Applied Electromagnetics, Signal Processing, & Communication (AESPC), Bhubaneswar, India, 24–26 November 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Guo, T.; Zhu, T.; Tjuawinata, I.; Zhao, J.; Lam, K.-Y. Local differential privacy and its applications: A comprehensive survey. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2024, 89, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Li, J.; Yue, G.; Song, H. Differential Privacy for Industrial Internet of Things: Opportunities, Applications, and Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 10430–10451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osia, S.A.; Shamsabadi, A.S.; Sajadmanesh, S.; Taheri, A.; Katevas, K.; Rabiee, H.R.; Lane, N.D.; Haddadi, H. A Hybrid Deep Learning Architecture for Privacy-Preserving Mobile Analytics. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 4505–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, A. Toward privacy-focused personalization: Designing a learning experience to facilitate privacy-personalization trade-off. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, Cagliari, Italy, 1–4 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.C.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.W.; Sun, W.J. Deep reinforcement learning-based computation offloading and resource allocation in security-aware mobile edge computing. Wirel. Netw. 2021, 27, 3357–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haibeh, L.A.; Yagoub, M.C.E.; Jarray, A. A Survey on Mobile Edge Computing Infrastructure: Design, Resource Management, and Optimization Approaches. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 27591–27610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinhong, F. Cross-Platform and Multi-Terminal Collaborative Software Information Security Strategy. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Mobile Computing and Sustainable Informatics (ICMCSI), Lalitpur, Nepal, 18–19 January 2024; pp. 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, A.K.; Petracca, G.; Aksu, H.; Jaeger, T.; Uluagac, A.S. A Survey on Sensor-Based Threats and Attacks to Smart Devices and Applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1125–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, H.; Chen, C. Robustness of on-Device Models: Adversarial Attack to Deep Learning Models on Android Apps. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM 43rd International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice (ICSE-SEIP), Madrid, Spain, 25–28 May 2021; pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatkhulin, T.; Alshawi, R.; Kulikova, A.; Mokin, A.; Timofeyeva, A. Analysis of Software Tools Allowing the Development of Cross-Platform Applications for Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the 2023 Systems of Signals Generating and Processing in the Field of on Board Communications, Moscow, Russia, 14–16 March 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N.; Koroniotis, N.; Keshk, M.; Zomaya, A.Y.; Tari, Z. Explainable Intrusion Detection for Cyber Defences in the Internet of Things: Opportunities and Solutions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1775–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddouti, S.E.; Betouil, A.; Chaoui, H. Enhancing Mobile Security: A Systematic Review of AI and Blockchain Integration Strategies for Effective Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT), Sakheer, Bahrain, 20–21 November 2023; pp. 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.S.; Ashit, D.H.; Chetan, C.N. A Proactive Approach to Advanced Cyber Threat Hunting. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Computation System and Information Technology for Sustainable Solutions (CSITSS), Bangalore, India, 2–4 November 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernpruner, M.; Carbone, R.; Sciarretta, G.; Ranise, S. An Automated Multi-Layered Methodology to Assist the Secure and Risk-Aware Design of Multi-Factor Authentication Protocols. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2024, 21, 1935–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, M.; Tresoldi, G.; Granger, L.; Lenders, V. Building an Avionics Laboratory for Cybersecurity Testing. In Proceedings of the 15th Workshop on Cyber Security Experimentation and Test, Virtual, 8 August 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Luo, P.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Dong, R.; Guan, Y. A review and prospect of cybersecurity research on air traffic management systems. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2025, 47, 1230–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Bhatti, N.; Masood, A.; Alharbi, A.; Alotaibi, S. Advancements in ADS-B security: A comprehensive survey of vulnerabilities, mitigation strategies, system requirements, and emerging research trends. Preprints 2024, 2024050586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Panaousis, E.; Noakes, C.; Laszka, A.; Panda, S.; Loukas, G. SoK: The MITRE ATT&CK framework in research and practice. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, H.; Liu, T.; Hou, M.; Giannelos, S.; Strbac, G. Decarbonisation of Data Centre Networks through Computing Power Migration. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 5th International Conference on Computer Communication and Artificial Intelligence (CCAI), Haikou, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaloev, M.; Krastev, G. Comprehensive Review of Benefits from the Use of Sparse Updates Techniques in Reinforcement Learning: Experimental Simulations in Complex Action Space Environments. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Communications, Information, Electronic and Energy Systems (CIEES), Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 23–25 November 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.