Abstract

Based on the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method, this study investigates the propagation effects of lightning electromagnetic fields over mixed sea–land paths. A self-developed FDTD computational model is employed, which takes into account the influence of the Earth–ionosphere waveguide structure on the radiation field propagation. Through numerical simulations, the waveforms of the vertical electric field and azimuthal magnetic field of the lightning radiation during mixed-path propagation are obtained. The results demonstrate that under long-distance propagation conditions of 50 km, the discontinuity between land and sea media significantly distorts the electric field waveform, while the influence on the magnetic field waveform is negligible. This study provides a reliable numerical basis for analyzing the propagation characteristics of lightning radiation fields in complex terrain and offers valuable insights for lightning location and electromagnetic environment assessment.

1. Introduction

Lightning, as a powerful natural discharge phenomenon, serves not only as a key component of atmospheric electrical processes but also generates electromagnetic pulses that pose serious threats to critical infrastructure including power grids, telecommunications, and aerospace systems [1,2]. In coastal regions and offshore platforms where land–sea interfaces exist, frequent lightning activity presents unique challenges for detection and protection [3,4]. During propagation from source regions to observation points, lightning electromagnetic fields are significantly influenced by the underlying surface medium’s properties. The substantial differences in dielectric characteristics between seawater and land mean that such mixed propagation paths inevitably alter electromagnetic field propagation patterns [5]. Thus, precisely elucidating the propagation characteristics of lightning electromagnetic fields in mixed paths is crucial for enhancing the positioning accuracy of lightning detection networks in coastal and maritime areas, and for optimizing lightning protection design of critical infrastructure, carrying significant scientific importance and engineering value [6,7].

To investigate the effects of complex terrain on lightning electromagnetic fields, extensive research has been conducted in the academic community [8,9,10]. The finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method has emerged as an effective tool for simulating the long-distance propagation of lightning electromagnetic pulses due to its advantages in handling complex media and inhomogeneous spaces [11,12,13,14]. Based on this methodology, scholars have conducted preliminary explorations on the effects of inhomogeneous paths. For instance, Cooray et al. investigated the relationship between return-stroke electric fields and their derivatives with propagation paths [12]; Daniele et al. analyzed the propagation characteristics of electromagnetic fields from offshore lightning events across different terrains [14]; while Jiang et al. examined the propagation properties of electromagnetic fields over vertically stratified ground structures [15]. Furthermore, researchers including Hou and Li have studied the influence of mountainous terrain on the peak values and waveforms of lightning radiation fields, providing theoretical analyses of propagation effects in mountainous areas [16,17,18,19]. These studies collectively demonstrate that medium discontinuities along propagation paths, particularly at land–sea interfaces, can cause non-negligible distortion effects on electric field waveforms.

Despite the significant progress achieved in existing studies, several scientific issues and technical challenges remain to be addressed. First, while most research has focused on the terrain effects on groundwave propagation, few have incorporated the Earth–ionosphere waveguide crucial factor for long-distance propagation into their models [20,21]. The interaction between skywaves and groundwaves may introduce additional complexities under mixed-path conditions, and neglecting this effect could lead to deviations in field calculations beyond tens of kilometers [22,23]. Second, existing studies predominantly concentrate on variations in the electric field component, while lacking systematic comparative analysis of the magnetic field’s response characteristics in mixed paths. Although the magnetic field is generally considered less affected by surface propagation conditions, this assertion requires rigorous verification under the strong-contrast media conditions at land–sea boundaries. Finally, a key technical challenge lies in developing a full-wave electromagnetic model that simultaneously accounts for both complex surface media and the Earth–ionosphere waveguide, enabling the quantitative separation of differential effects on electric and magnetic fields.

To address these challenges, this study aims to investigate the propagation characteristics of lightning electromagnetic fields in coastal environments by developing an FDTD model incorporating realistic land–sea boundaries and the Earth–ionosphere waveguide. The key innovations of this research include the following: (1) establishing a large-scale computational model capable of simultaneously simulating groundwave and skywave propagation effects, thereby more accurately representing long-distance propagation physics; (2) analyzing and comparing the sensitivity differences between the vertical electric field and azimuthal magnetic field waveforms to mixed-path media variations, confirming the stability of magnetic fields in complex propagation scenarios. The findings of this study will provide critical theoretical foundation and data support for developing high-precision lightning detection algorithms, particularly for data correction in coastal and maritime lightning location systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modeling

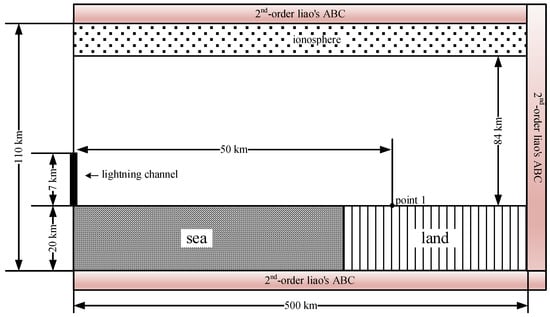

This study investigates the characteristics of lightning radiated fields under land–sea mixed propagation path conditions, based on the 2D cylindrical coordinate system FDTD computational model independently developed by the Institute of Electrical Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences [15]. The computational model is illustrated in Figure 1. The entire computational domain of the model is set to 500 km × 110 km. For simulating the mixed propagation path of lightning, two regions (seawater and land) are configured in the topographic part. Both the seawater and land regions are positioned 20 km away from the lower boundary of the computational model. This setup serves theoretical law verification rather than simulation of specific real sea areas. The lightning discharge channel is set to a length of 7 km. Furthermore, considering the long-distance propagation process of lightning, the skywave propagation effect of lightning in the waveguide formed by the ground and ionosphere cannot be ignored. Therefore, an ionosphere region is incorporated into the computational model to simulate the propagation process of lightning in the ground–ionosphere waveguide. The height of the ionosphere is set to 84 km. A 2nd-order Liao’s absorbing boundary is adopted for the entire computational domain to reduce the impact of electromagnetic wave reflections from boundaries on the calculation results. Also, an observation point is placed 50 km away from the bottom of the lightning channel, which is used to evaluate the influence of the mixed propagation path on the waveform of the lightning radiated field.

Figure 1.

Calculation model of lightning radiation field characteristics in hybrid land–sea propagation paths based on FDTD.

Time-update equations for electric field components in the

- and

-directions,

and

, are derived from Ampere’s law, and magnetic field component

is derived from Faraday’s law.

In the FDTD model constructed in this study, the solution iteration formulas for the three components

,

and

are presented as follows:

In the above equation, the electric field components are computed at integer time steps

, where

is an integer number and

is the time increment, and the magnetic field components are computed at half-integer time steps

.

is the electric permittivity at the point

,

is the electric conductivity at the point

, and

is the magnetic permeability at the point

.

is the cell side length in the radial direction, and

is the cell side length in the vertical direction.

In the source region, a simpler update equation is adopted [15]:

Used for FDTD simulation in our 2D cylindrical coordinate system, the computational domain is discretized into a cylindrical coordinate grid with

20,000 (

-direction) and

2200 (

-direction), resulting in a total of 44,000,000 grid nodes. Each node required the solution of three electromagnetic field components (

), leading to a total of 132,000,000 unknowns for the discretized system of equations. All simulations were performed in MATLAB R2023a (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Custom MATLAB scripts (.m files) were written to execute numerical computations directly, without invoking dedicated preconfigured solvers. Our MATLAB scripts (.m files) directly implement a custom numerical algorithm (the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method), instead of using predefined solver functions, to tailor the computations to the specific characteristics of our research problem.

2.2. Parameters

In the FDTD computational model established in this study, there are dielectric regions including seawater, land, air, and the ionosphere. The relative permittivity, relative permeability, and electrical conductivity of each dielectric affect the propagation process of electromagnetic waves. The entire computational domain is divided into grids with a size of 50 m × 50 m, and the time step for each iteration is set to less than 40 ns. In this study, the relative permittivity values of seawater, land, and air are set to 81 [12], 10, and 1, respectively, and the electrical conductivity of seawater is set to 4 S/m. Considering that the ground has finite electrical conductivity, the electrical conductivity of the ground is set to 0.001 S/m in this study.

The numerical stability of the FDTD calculations is guaranteed by satisfying the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) stability condition. The time step size in this paper is

. The time step size in this paper is calculated as follows:

The ionospheric electrical conductivity in this study is calculated with reference to the ionospheric conductivity formula proposed by Thang et al. [24]. The formula for calculating the ionospheric conductivity as a function of altitude is as follows:

In Formula (8), the value of

is 2.22 μS/m, the value of

is 0.671/km, and the value of

is set to 84 km. During the calculation process, we assume that the conductivity of the ionosphere is stable, meaning it is not affected by the propagation of lightning electromagnetic pulses.

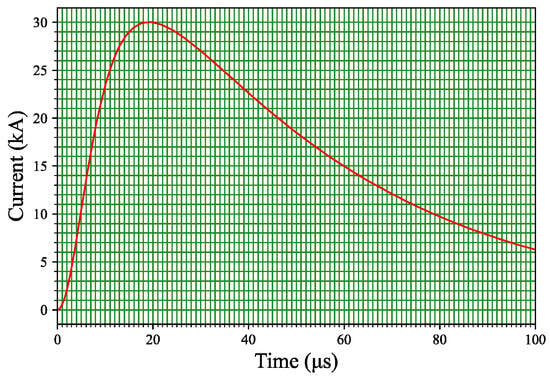

The lightning model used in this study adopts a transmission line model with linear attenuation along the altitude [12]. The velocity of lightning in the channel is set to c/2 (where c denotes the speed of light in vacuum) [25]. The waveform of the base current is shown in Figure 2, and its expression is as follows [11]:

Figure 2.

Lightning current waveforms used in this study.

The values of each parameter in the expressions (9) and (10) are presented in Table 1:

Table 1.

Parameters for the lightning channel base current.

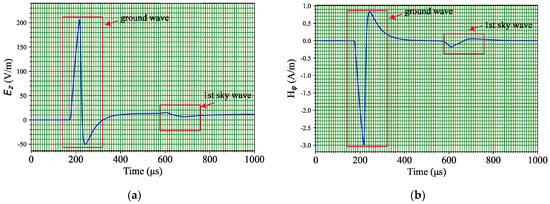

2.3. Validation

Based on the computational model established in this study, we calculated the radiated waveforms of the vertical electric field and azimuthal magnetic field at a distance of 50 km from the lightning channel under the condition of an ideally conducting ground. The simulations were carried out on a 64-bit computational platform having 32 GB of available memory. The calculation time of the whole program is about 140 h. The results are shown in Figure 3a,b. It can be observed from Figure 3a,b that the FDTD computational model constructed in this study can effectively calculate the groundwave and skywave propagation characteristics of lightning under long-distance propagation conditions.

Figure 3.

Lightning waveform at 50 km under ideal conducting ground condition. (a) Vertical electric field; (b) azimuthal magnetic field.

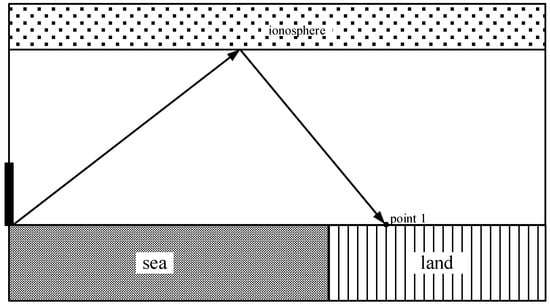

As shown in Figure 4, the propagation trajectory of the first skywave through the Earth–ionosphere waveguide is schematically depicted. This visualization clarifies the physical process involving two reflections, aiding in understanding skywave generation, delay features, and differentiation from groundwaves.

Figure 4.

Propagation path schematic of lightning-generated first skywave in the ground–ionosphere waveguide.

3. Results

In this section, using the established FDTD model, we calculated the lightning waveforms at the ground detection station when a lightning strike occurs over the sea surface (50 km away from the station), with the lightning propagating along the seawater–land mixed path. We focused on analyzing the influence of the mixed path on the radiated field waveforms of the lightning electric and magnetic fields under different seawater lengths (20 km, 30 km, and 40 km). The research results of this paper can provide a reference for studying the propagation effects of lightning along mixed paths.

3.1. Influence of the Vertical Electric Field

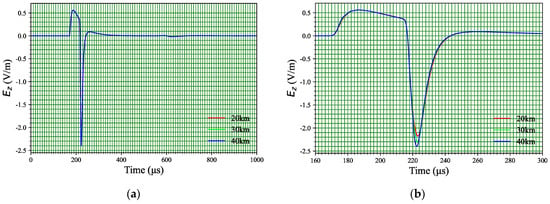

We calculated the vertical electric field waveforms at the observation point (50 km away from the lightning channel) under different seawater lengths (20 km, 30 km, and 40 km), as shown in Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

Lightning vertical electric field waveforms at 50 km in hybrid propagation paths (seawater segment lengths: 20 km, 30 km, 40 km). (a) Full view (0 μs to 1000 μs); (b) enlarged view (160 μs to 300 μs).

As can be seen from Figure 5a, firstly, under the condition of considering the mixed propagation path of the lightning radiated field, the peak value of the vertical electric field is on the order of −2.5 V/m. In contrast, under the condition of an ideally conducting ground, the peak value of the vertical electric field exceeds 200 V/m. This is mainly because electromagnetic waves propagate without loss under the ideally conducting condition, while in the seawater–land mixed propagation path, the mixed conductivity causes a significant attenuation of the electric field energy, which is more consistent with the real lightning propagation process.

Secondly, under the seawater–land mixed propagation path, the rising edge of the vertical electric field waveform is relatively gentle. This indicates the effect on mixed propagation paths. The finite conductivity of seawater and land induces phase modulation of the lightning radiated fields during propagation. This modulation slows the rising edge of the vertical electric field waveform.

Additionally, the peak time and peak amplitude of the vertical electric field at the observation point differ under different seawater lengths (20 km, 30 km, 40 km), as shown in Figure 5b. It can be observed from Figure 5b that the seawater length in the mixed path has an impact on both the peak value and peak time of the vertical electric field. The higher the proportion of seawater length in the mixed path is, the larger the amplitude of the vertical electric field is. This exactly shows that the vertical electric field experiences less attenuation in a propagation medium with high conductivity.

The seawater length in the mixed path also affects the time when the vertical electric field reaches its peak. The higher the proportion of land length in the mixed path is, the later the peak arrival time is. For the groundwave short-baseline lightning detection and location network based on the time-of-arrival method, when using the peak arrival time of the vertical electric field for location, it is necessary to consider the influence of the mixed path to improve the location accuracy of the lightning detection and location network.

When considering the effect of the ionosphere, we calculated the first skywave of lightning propagating in the ground–ionosphere waveguide, as shown in Figure 5a. It can be seen that the first skywave is basically not affected by the proportion of seawater length in the mixed path, and this result is reasonable. This is because the first skywave reaches the observation point mainly through reflection in the ground–ionosphere waveguide and is not affected by the mixed propagation path. In subsequent studies, we will further investigate the influence of the mixed propagation path on multiple skywaves such as the second skywave.

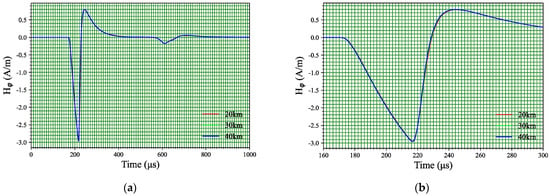

3.2. Influence of the Azimuthal Magnetic Field

For comparative analysis, this study calculated the azimuthal magnetic field waveforms at the observation point (50 km) under different seawater path lengths (20 km, 30 km, 40 km), as shown in Figure 6a. The results indicate that the magnetic field waveforms under all path conditions are highly consistent, with no significant variations observed in either peak values or time-to-peak, as shown in Figure 6b. Based on this, under such conditions, the time-difference-of-arrival (TDOA) method based on the magnetic field can be considered for lightning detection and location research as a reference, so as to improve the detection accuracy of the TDOA-based method.

Figure 6.

Lightning azimuthal magnetic field waveforms at 50 km in hybrid propagation paths (seawater segment lengths: 20 km, 30 km, 40 km). (a) Full view (0 μs to 1000 μs); (b) enlarged view (160 μs to 300 μs).

4. Discussion

This study reveals the differential effects of mixed sea–land propagation paths on lightning electromagnetic fields through FDTD numerical simulations. The key finding is that the vertical electric field exhibits high sensitivity to surface medium properties, whereas the azimuthal magnetic field and the first skywave remain relatively insensitive. This phenomenon can be explained by the fundamental theory of electromagnetic wave propagation. The vertical electric field component is closely related to the redistribution of surface charges, and its amplitude and waveform strongly depend on the conductivity and permittivity of the medium. In mixed sea–land paths, when electromagnetic waves cross medium boundaries with significant conductivity differences, complex reflection, refraction, and interface polarization effects are triggered, leading to substantial attenuation of the electric field energy (as shown in Figure 5b) and broadening of the waveform rise time. This waveform distortion shares the same physical essence as the observations of Li et al. [17] in mountainous terrain, namely that changes in surface current paths induced by inhomogeneous media are the primary cause of variations in the electric field waveform.

This study further quantifies the impact of the sea portion proportion in the mixed path on the electric field peak and time-to-peak (Figure 5b). The results indicate that a higher proportion of the high-conductivity sea path corresponds to less electric field attenuation and an earlier time-to-peak. This aligns with the theoretical predictions of Cooray [12] regarding the influence of the propagation path on the electric field derivative, but our study provides more direct quantitative evidence through controlled variables (sea segment length). This finding has clear implications for lightning location systems relying on the time-of-arrival (TOA) of groundwaves: in coastal areas, failure to correct for time delays introduced by land–sea path differences will directly lead to location errors.

Furthermore, the simulation results confirm that the first skywave is unaffected by near-surface mixed paths (Figure 5b). This verifies that skywave propagation is primarily governed by the height and characteristics of the ionosphere, with its path far above local variations in the surface medium. This result agrees with long-distance propagation theory models and indirectly validates the effectiveness of the Earth–ionosphere waveguide setup in our model.

This study also has several limitations. First, the sea–land boundary in the model was simplified as an ideal two-dimensional linear interface, without considering the three-dimensional complexity and topographic variations in actual coastlines. Second, the medium electromagnetic parameters were set as uniform values, not reflecting the spatial heterogeneity caused by actual soil moisture and salinity. Future work should focus on integrating real geographic information system data and investigating the propagation characteristics of higher-order skywaves in more complex three-dimensional terrains to further refine the understanding of the complete physical picture of lightning propagation paths.

5. Conclusions

This study elucidates the propagation characteristics of lightning electromagnetic fields over mixed sea–land paths using a self-developed FDTD model. The key conclusions are as follows: firstly, the vertical electric field exhibits extreme sensitivity to surface medium properties. Its waveform amplitude undergoes severe attenuation compared to the ideal conductor scenario under mixed-path conditions, with the rising edge significantly broadened due to medium dispersion effects. Both the peak value and time-to-peak of the electric field show a clear correlation with the sea path length. Secondly, the azimuthal magnetic field demonstrates excellent stability under these propagation conditions, remaining largely unaffected by variations in the path medium. Finally, the first skywave, as its propagation path primarily lies within the elevated waveguide, is similarly undisturbed by near-surface mixed-path variations.

These findings carry significant practical implications for lightning detection. The stability of the magnetic field component positions it as a potentially preferred parameter for constructing highly robust lightning location systems in complex coastal terrain. Simultaneously, the path-dependent characteristics of the electric field’s time-to-peak highlight the necessity of incorporating path-specific corrections in precision groundwave-based location systems to enhance positioning accuracy for coastal and maritime lightning.

Looking ahead, future research can be deepened in two main directions: first, extending the current idealized two-dimensional interface model to incorporate realistic three-dimensional topography and inhomogeneous medium parameters for more accurate simulation of actual geographical environments. Second, delving deeper into the propagation mechanisms of higher-order skywaves under complex path conditions, thereby laying a more solid foundation for developing precise forecasting models of lightning electromagnetic fields that account for the entire propagation path.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.X., J.W., X.Z. and Q.M.; methodology, F.X., J.W., and J.S.; software, F.X., J.W. and L.J.; validation, F.X., J.W. and L.J.; formal analysis, F.X. and Q.M.; investigation, F.X.; resources, Q.M.; data curation, F.X. and L.J.; writing—original draft preparation, F.X. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, L.J. and Q.M.; visualization, L.J.; supervision, Q.M.; project administration, J.S.; funding acquisition, Q.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Smart Grid—National Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2025ZD0805601) and the National Key R&D Program of China, grant number China (2023YFC3006802).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all members of the Institute of Electrical Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The authors would also like to thank the reviewers for their helpful feedback, which significantly improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cooray, V.; Cooray, C.; Andrews, J. Lightnings caused injuries. J. Electron. 2007, 65, 386–394. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, D.-Q.; Nguyen, N.-N.; Vu, P.-T. Rbf-FDTD analysis of lightning-induced voltages on multi-conductor distribution lines. Energies 2025, 18, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paknahad, J.; Sheshyekani, K.; Rachidi, F. Lightning electromagnetic fields and their induced currents on buried cables. Part I: The effect of an ocean–land mixed propagation path. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2014, 56, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.R.; Stanfill, S. Reply to the comment on “The physical origin of the land–ocean contrast in lightning activity”: [C. R. Physique 5 (2004) 155]. Comptes Rendus Phys. 2004, 5, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfino, F.; Procopio, R.; Rossi, M. Lightning electromagnetic radiation over a stratified conducting ground: Formulation and numerical evaluation of the electromagnetic fields. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2011, 116, D04101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Araki, S.; Baba, Y.; Tsuboi, T.; Okabe, S.; Rakov, V.A. An FDTD study of errors in magnetic direction finding of lightning due to the presence of conducting structure near the field measuring station. Atmosphere 2016, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, E.H.; Jacobson, A.R.; Holzworth, R.H.; Rodger, C.J.; Dowden, R.L. Local time variation in land/ocean lightning flash density as measured by the world wide lightning location network. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D13111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A. An underground radio wave propagation prediction model for digital agriculture. Information 2019, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Karami, H.; Azadifar, M.; Rachidi, F. On the efficiency of openacc-aided gpu-based FDTD approach: Application to lightning electromagnetic fields. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikawa, T.; Sonoda, J.; Sato, M.; Honma, N.; Ikegawa, Y. Analysis of lightning electromagnetic field on large-scale terrain model using three-dimensional MW-FDTD parallel computation. Electr. Eng. Jpn. 2013, 184, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Xiao, Q.; Chen, J.; Dong, M. A study on the electromagnetic characteristics of very-low-frequency waves in the ionosphere based on FDTD. Electronics 2025, 14, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, V.; Ye, M. Propagation effects on the lightning-generated electromagnetic fields for homogeneous and mixed sea-land paths. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 1994, 99, 10641–10652. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.; Lyu, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Yan, X.; Wu, B.; Qi, Q.; Wu, S. Lightning electromagnetic fields along an ocean–land mixed propagation path generated by return strokes to wind turbines. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2018, 61, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele, M.; Nicora, M. On the importance of considering realistic orography into the evaluation of lightning electromagnetic fields in mixed path. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2022, 64, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Dong, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Ma, Q. Propagation characteristics of lightning radiation field on three-layer vertical layered ground based on cpml absorption boundary. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2023, 65, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Azadifar, M.; Rubinstein, M.; Rachidi, F.; Zhang, Q. On the propagation of lightning-radiated electromagnetic fields across a mountain. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2020, 62, 2137–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Azadifar, M.; Rachidi, F.; Rubinstein, M.; Paolone, M.; Pavanello, D.; Metz, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z. On lightning electromagnetic field propagation along an irregular terrain. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2015, 58, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Azadifar, M.; Rachidi, F.; Rubinstein, M.; Diendorfer, G.; Sheshyekani, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z. Analysis of lightning electromagnetic field propagation in mountainous terrain and its effects on toa-based lightning location systems. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2016, 121, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Luque, A.; Rachidi, F.; Rubinstein, M.; Azadifar, M.; Diendorfer, G.; Pichler, H. The propagation effects of lightning electromagnetic fields over mountainous terrain in the earth-ionosphere waveguide. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2019, 124, 14198–14219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.A.; Heavner, M.J.; Jacobson, A.R.; Shao, X.M.; Massey, R.S.; Sheldon, R.J.; Wiens, K.C. A method for determining intracloud lightning and ionospheric heights from VLF/LF electric field records. Radio Sci. 2004, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Ma, Q.M.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, F.; Yuan, S.B.; Chang, S.; He, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, Q.J. Asia-pacific lightning location network (aplln) and preliminary performance assessment. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, Q.; Huang, Q.; Xiao, F. A method for determining d region ionosphere reflection height from lightning skywaves. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2021, 221, 105692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiang, L.; Dong, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, F.; Yuan, S.; Ma, Q. Analysis of lightning electromagnetic field in mountainous terrain. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3004, 012100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, T.H.; Rakov, V.A.; Baba, Y.; Somu, V.B. 2d FDTD simulation of lemp propagation considering the presence of conducting atmosphere. Asia-Pac. Int. Symp. Electromagn. Compat. 2016, 1, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Shoory, A.; Rachidi, F.; Delfino, F.; Procopio, R.; Rossi, M. Lightning electromagnetic radiation over a stratified conducting ground: 2. Validity of simplified approaches. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, D11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.