Abstract

As artificial intelligence (AI) becomes increasingly woven into educational design and decision-making, its use within initial teacher education (ITE) exposes deep tensions between efficiency, equity, and professional agency. A critical action research study conducted across three iterations of a third-year ITE course investigated how pre-service teachers engaged with AI-supported lesson planning tools while learning to design for inclusion. Analysis of 123 lesson plans, reflective journals, and survey data revealed a striking pattern. Despite instruction in inclusive pedagogy, most participants reproduced fixed-tiered differentiation and deficit-based assumptions about learners’ abilities, a process conceptualised as micro-streaming. AI-generated recommendations often shaped these outcomes, subtly reinforcing hierarchies of capability under the guise of personalisation. Yet, through iterative reflection, dialogue, and critical framing, participants began to recognise and resist these influences, reframing differentiation as design for diversity rather than classification. The findings highlight the paradoxical role of AI in teacher education, as both an amplifier of inequity and a catalyst for critical consciousness and argue for the urgent integration of critical digital pedagogy within ITE programmes. AI can advance inclusive teaching only when educators are empowered to interrogate its epistemologies, question its biases, and reclaim professional judgement as the foundation of ethical pedagogy.

1. Introduction

The rapid integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into educational systems has transformed how teaching and learning are conceptualised and enacted [1]. From adaptive assessment tools to generative lesson planning platforms, AI technologies promise to personalise instruction, support differentiation, and streamline teacher planning processes. This shift offers opportunities and challenges in initial teacher education (ITE). On one hand, AI tools provide novice teachers with immediate scaffolding for complex pedagogical tasks. On the other hand, these same tools risk embedding and perpetuating existing inequalities through algorithmic decision-making, particularly when uncritically adopted.

Differentiation is a foundational element of inclusive pedagogy and teacher preparation, encouraging educators to respond to student diversity through varied content, process, and products. Theoretically grounded in constructivist and sociocultural paradigms [2,3] and further advanced through Universal Design for Learning [4] and inclusive pedagogy frameworks [5], differentiation seeks to enable all learners to access and engage with a meaningful curriculum. However, recent scholarship has begun to critique how digital personalisation, particularly AI-mediated, may reproduce historical forms of streaming and fixed-ability thinking [6,7].

Micro-streaming, where learners are implicitly grouped by perceived ability and assigned differentiated content accordingly, emerges as a subtle but powerful bias mechanism. When embedded in AI tools and reinforced through teacher planning decisions, such practices may result in systemic stratification disguised as individualisation. In the context of ITE, where professional beliefs and habits are still forming, this dynamic raises critical questions about how pre-service teachers interact with AI, interpret differentiation principles, and construct pedagogical decisions.

This paper investigates these issues through an action research study. The study explores how pre-service teachers use AI-supported tools to develop differentiated lesson plans and examines how these tools and practices reproduce or resist micro-streaming and deficit-based assumptions. By critically analysing lesson plans, reflective journals, and survey data, the study aims to illuminate the pedagogical and ethical implications of AI use in pre-service teacher education and to contribute to a growing body of literature calling for critical digital pedagogy in the age of automation. This is especially pertinent given the global divergence in how AI is positioned in educational reform, with contrasting models of implementation emerging between Western contexts and nations such as China, raising questions about the cultural and ideological assumptions embedded in AI-driven pedagogical systems [8].

1.1. Theoretical and Methodological Framework

This study is grounded in a theoretical framework that integrates sociocultural learning theory, critical pedagogy, inclusive education, and recent critiques of algorithmic individualisation. These perspectives illuminate how differentiation technologies intersect with social hierarchies, teacher beliefs, and pedagogical practice. Moreover, the growing field of explainable AI (XAI) highlights the importance of transparency in algorithmic decision-making. In educational contexts, where teachers rely on AI outputs for differentiation, the opacity of AI systems can further obscure embedded assumptions, limiting educators’ capacity to critique or adjust recommendations [9].

1.2. Sociocultural Learning Theory

Drawing from Vygotsky [3], sociocultural theory positions learning as a socially mediated process where knowledge is co-constructed through interaction within the learner’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The ZPD refers to the gap between what learners can achieve independently and what they can accomplish with support from more knowledgeable peers or teachers. This paper conceptualises effective differentiation as a responsive and dynamic scaffolding approach tailored to support individual learners in progressing through their ZPD. From a sociocultural perspective, differentiation underpinned by these principles emphasises continuous, adaptive support rather than static, ability-based grouping.

Central to sociocultural theory is the importance of language, dialogue, and social interaction in facilitating cognitive development. Classroom practices influenced by sociocultural perspectives often involve collaborative activities, guided inquiry, and interactive dialogue, enabling students to engage in meaningful discourse that promotes deeper conceptual understanding. However, when differentiation practices become overly reliant on algorithmically predetermined groupings or rigid instructional paths, they risk limiting social interactions and reducing the complexity of collaborative learning experiences. This static form of differentiation may inadvertently constrain learners to simplistic, lower-level cognitive tasks, inhibiting their capacity to develop higher-order skills through rich, socially interactive contexts [10].

Moreover, recent research [9,11,12] highlights educators’ need to remain critically aware of how algorithmic tools may implicitly embed fixed conceptions of ability, potentially reinforcing deficit narratives. Educators must therefore approach differentiation strategies with reflexivity and a commitment to maintaining pedagogical flexibility, ensuring that scaffolding practices evolve in response to ongoing learner development rather than adhering to predetermined algorithmic recommendations. By aligning differentiation practices closely with sociocultural theory, educators can better facilitate equitable and dynamic learning environments that support all students in meaningful and continuous cognitive growth.

1.3. Critical Pedagogy and Educational Power

Freire’s [13] conception of critical pedagogy underpins the study’s commitment to equity and reflexivity in education. Central to critical pedagogy is the recognition that teaching and learning are inherently political acts that either reinforce or challenge existing power structures and social inequalities. According to Freire, education should empower students and teachers alike to critically engage with their realities, question prevailing assumptions, and take transformative action toward social justice. This critical stance is particularly significant when examining educational technologies such as AI-driven tools, which are frequently presented as objective or neutral but inherently embody specific norms, values, and ideologies.

Technologies that claim to ‘personalise’ learning must therefore be critically interrogated for their role in encoding dominant norms, reproducing social hierarchies, and influencing teacher assumptions about student potential. AI-based differentiation tools often reflect and perpetuate existing educational inequities by embedding assumptions about learners’ abilities and potential, potentially marginalising students based on narrow, predetermined metrics. Educators must actively scrutinise these technological tools, examining how algorithmic decisions influence educational opportunities, reinforce biases, and limit learners’ agency and growth.

Furthermore, critical pedagogy emphasises the importance of educator reflexivity and continuous self-awareness in recognising and resisting these hidden biases and inequities. Educators can reclaim agency from algorithmic tools by fostering critical digital literacy and engaging in reflective practices. This ensures that pedagogical decisions prioritise equitable and inclusive educational outcomes over technological efficiency. This study employs critical pedagogy as a foundational lens, advocating for an explicitly reflective, transformative, and equity-oriented approach to differentiation and technology integration.

1.4. Inclusive Pedagogy and the Critique of Deficit Thinking

As Florian and Black-Hawkins [5] articulated, inclusive pedagogy offers a significant counterpoint to deficit-based assumptions commonly embedded in differentiation practices. Rather than adapting instruction primarily in response to students’ perceived weaknesses or deficits, inclusive pedagogy begins from the premise that learners can participate in complex and meaningful learning experiences. This pedagogical stance shifts the responsibility from learners to educational systems and practices, asserting that the educational environment and instructional methods must be adapted to accommodate learner diversity.

Inclusive pedagogy challenges educators to design learning activities that do not marginalise or stigmatise students based on their identified abilities or needs. It encourages using universally designed instructional strategies that provide multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression, allowing all students to access and engage deeply with content. By centring flexibility, inclusivity, and universal accessibility in lesson planning, inclusive pedagogy mitigates the risk of reinforcing static ability-groupings and promotes equitable opportunities for all learners.

However, despite these principles, differentiation practices risk inadvertently promoting micro-streaming, particularly when implemented through algorithmic tools that categorise students based on fixed criteria or performance metrics. Such tools may reinforce subtle deficit narratives by implicitly suggesting lower expectations for specific learners. Educators must therefore maintain a critical and reflective approach, continuously examining their instructional choices and actively working to ensure that differentiation strategies remain fluid, responsive, and equitable. Educators can more effectively challenge and disrupt implicit biases and systemic inequities embedded in conventional and algorithmic differentiation practices by adopting an inclusive pedagogical stance.

1.5. The Dark Side of Individualisation and Micro-Streaming

Watters [6] and others have highlighted how individualisation, particularly when implemented through algorithmic technologies, can inadvertently reinforce patterns of educational inequality. While individualisation is often celebrated as a means to accommodate learner diversity and personalisation, it carries inherent risks of subtly replicating historical inequities through micro-streaming practices. Micro-streaming refers to the subtle sorting and tracking of learners within classrooms based on perceived abilities or performance metrics, often driven by algorithmic recommendations that appear neutral and objective.

Drawing on Porter’s [14] critique of Cold War-era intelligence testing and its subsequent role in racialised and socioeconomically stratified educational tracking, this study examines how contemporary algorithmic differentiation systems may similarly re-inscribe and naturalise these hierarchies. Under the guise of objectivity and personalisation, AI-based differentiation tools can perpetuate fixed ability perceptions, embedding assumptions about learner potential and limiting equitable educational opportunities. These algorithmic systems, particularly within initial teacher education, carry significant risks as they influence novice teachers’ formative pedagogical beliefs and practices, potentially solidifying inequitable habits early in educators’ careers.

Moreover, micro-streaming through algorithmic differentiation can have profound long-term implications, systematically constraining students’ access to rich educational experiences and limiting opportunities for intellectual growth. Educators must, therefore, be critically aware of the hidden biases and ideological underpinnings inherent in AI-supported differentiation tools. By maintaining a critical stance towards these technologies, educators can actively resist the reproduction of inequitable educational practices, fostering instead pedagogical strategies that genuinely support diversity, inclusion, and equity in education.

1.6. Mindset Theory and Expectations

Dweck’s [15] theory of fixed and growth mindsets introduces a psychological dimension critical to understanding differentiation practices. This theory distinguishes between fixed mindsets, which view abilities as innate and unchangeable, and growth mindsets, which view abilities as dynamic and improvable through effort and experience. Teachers who internalise AI-suggested groupings or learning levels risk adopting a fixed mindset toward their students’ abilities, potentially constraining the complexity and challenge of their assigned tasks. Over time, this unintentional reinforcement of fixed mindsets can perpetuate a self-fulfilling prophecy [16], whereby students internalise these limited expectations, ultimately influencing their academic self-concept and motivation.

When differentiation becomes overly rigid and influenced by algorithmic outputs, it may inadvertently establish and reinforce fixed perceptions of learner capabilities. Consequently, students perceived as lower-performing may receive tasks that lack cognitive complexity, reducing opportunities to engage in higher-order thinking and learning experiences that foster academic growth. To counteract these risks, educators must cultivate a growth-oriented classroom culture, emphasising the value of effort, resilience, and continuous improvement. Teachers must also critically examine the recommendations generated by AI-driven tools, actively seeking to challenge and adjust these suggestions to foster growth mindsets among students and avoid the pitfalls of micro-streaming.

1.7. The Matthew Effect and Long-Term Stratification

Stanovich’s [17] Matthew Effect theory articulates how minor initial differences in performance or perceived ability can snowball over time, exacerbating educational disparities. Initially proposed to describe reading development, the Matthew Effect highlights how students with early advantages accumulate further benefits, while those with early disadvantages increasingly fall behind. Applied to AI-mediated lesson planning and differentiation, this theory explains how assigning consistently less cognitively demanding tasks to students, particularly those labelled lower-performing, may significantly restrict their exposure to higher-order cognitive processes and advanced learning opportunities.

When educators rely excessively on algorithmically driven differentiation, students initially classified as lower-ability learners may systematically receive tasks that focus predominantly on recall and comprehension rather than critical thinking, problem-solving, or creative exploration. Over time, this pattern can limit students’ cognitive development and reinforce negative academic self-concepts, thereby perpetuating and deepening educational inequities. Such cumulative disadvantage affects academic achievement, students’ long-term educational trajectories, future career opportunities, and socio-economic mobility.

To mitigate the risks associated with the Matthew Effect, educators must adopt differentiation practices that are flexible, dynamic, and cognitively challenging for all learners. Instructional strategies should be consciously designed to provide equitable access to rigorous academic tasks, ensuring that all students are regularly engaged in higher-order thinking activities. Critical examination of AI-generated recommendations is essential, alongside proactive adjustments to ensure pedagogical practices consistently challenge and support every student’s potential, counteracting long-term stratification and fostering genuine educational equity.

1.8. Methodological Orientation: Critical Action Research

This study adopts a critical action research methodology, reflecting its dual commitment to understanding and transforming educational practice. Rooted in Freire’s [13] conception of praxis, the dynamic interplay of reflection and action, critical action research seeks not merely to describe practice but to reshape it in pursuit of social justice and equity. Within this paradigm, research becomes an emancipatory process that interrogates and transforms existing assumptions, hierarchies, and ideologies.

In the context of initial teacher education (ITE), this methodology enables pre-service teachers to critically examine how their pedagogical decisions are shaped by broader social, cultural, and technological forces, including algorithmic mediation. The critical orientation of the research emphasises the development of agency and ethical awareness among participants, positioning them as co-researchers who actively reflect upon and reframe their teaching practices. Through iterative cycles of planning, action, reflection, and transformation, participants engaged with AI-supported lesson planning tools, critically analysed their outcomes, and collectively theorised the implications for inclusive education.

This process was deliberately designed to move beyond technical or instrumental understandings of differentiation towards a deeper critical consciousness of its political and ethical dimensions. Each cycle thus functioned both as a site of inquiry and as an intervention into teacher learning, where participants could experience, analyse, and reconstruct their approaches to inclusion in response to evidence and reflection.

Data were collected from lesson plans, reflective journals, surveys, and focus group discussions, encompassing both artefacts of practice and reflexive commentary. Analytical processes integrated multiple methods:

- Critical Discourse Analysis [18] to explore how language reflected and reinforced beliefs about learners, ability, and difference.

- Thematic Analysis [19] to identify evolving narratives about AI, authority, and teacher agency.

- Rubric-Based Quantitative Scoring to evaluate lesson complexity, flexibility, and inclusivity.

- Descriptive and Inferential Statistics to measure changes in participants’ beliefs about differentiation and AI across the intervention.

This multimodal approach provided both interpretive and empirical depth, revealing not only what teachers did but how and why they acted in particular ways. It foregrounded the interrelation between discourse, practice, and ideology, thereby aligning methodologically with the study’s critical intent: to examine how AI-mediated differentiation may reproduce or resist structures of inequity.

1.9. Reflexivity and Positionality

As both lecturer and researcher, the author occupied an insider–outsider position central to critical action research. This dual role offered privileged access to participants’ learning processes and authentic pedagogical contexts but also carried the risk of interpretive bias and power asymmetry. To address these challenges, reflexive strategies were embedded throughout the research design.

A reflexive journal was maintained to document evolving assumptions, decisions, and emotional responses, ensuring transparency in how interpretations were shaped. Classroom discussions and focus groups were structured to decentralise authority, framing the researcher as a facilitator of dialogue rather than an evaluator of performance. Participants were invited to question the research process itself, its focus, interpretations, and implications, thus enacting Freirean dialogical principles and reinforcing the participatory ethics of the project.

Ethical considerations extended beyond formal consent procedures to encompass the ongoing negotiation of trust and agency. Recognising that participants’ coursework was embedded within the research, safeguards such as anonymous reflective submissions, optional inclusion of data, and member checking were implemented to minimise coercion and enhance authenticity. This relational ethics framework sought to balance the researcher’s institutional responsibilities with participants’ autonomy and emotional safety.

Ultimately, the researcher’s positionality, both as an educator committed to equity and as an investigator of AI-mediated pedagogical practice, became an integral part of the inquiry. Reflexivity was not a methodological add-on but a core analytic stance, enabling continual interrogation of how power, ideology, and emotion intersected in the shared process of learning and change. Through this stance, the research aimed not simply to observe transformation but to embody it within its own praxis.

Anchored in this critical and reflexive framework, the study’s methodological design situates inquiry within authentic learning environments where theory and practice intersect. The following section outlines the participants and context through which these action research cycles unfolded, providing insight into the institutional setting, cohort characteristics, and pedagogical structures that shaped the research. Understanding this context is essential for interpreting how participants’ engagements with AI-supported differentiation emerged, evolved, and were transformed within the broader sociocultural and institutional landscape of initial teacher education.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants and Context

The study was conducted within third-year courses in the Bachelor of Education and Master of Teaching (Secondary) programmes at an Australian university. Across three consecutive cohorts, sixty pre-service teachers participated in a twelve-week intervention that explored inclusive lesson planning and differentiation through the use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools. The participants were preparing to become secondary teachers in the subject area of Digital Technologies (computer education) and brought with them a diverse range of experiences and confidence levels regarding both differentiation and educational technology.

Approximately 55 per cent of the participants identified as female and 45 per cent as male, with ages ranging from 21 to 45. Prior experience with AI technologies varied considerably: around 30 per cent reported moderate familiarity, such as prior use of AI chatbots, while the remaining 70 per cent indicated minimal or no experience. Participation formed part of the assessed coursework but also contributed to embedded research activities approved by the university’s Human Research Ethics Committee. Ethical participation was voluntary, with informed consent obtained and pseudonyms assigned in all reporting to maintain confidentiality.

2.2. Research Design and Phases

The study adopted a critical action research design, engaging participants in iterative cycles of planning, action, reflection, and revision. This methodology was chosen to foster inquiry into both practice and belief, enabling participants to analyse and transform their approaches to differentiation in real time. Each research phase built upon the previous one, progressively deepening participants’ understanding of inclusive pedagogy and the critical use of AI in lesson planning.

In the initial phase (Week 1), students were introduced to foundational theories of inclusive pedagogy and differentiation, as well as the risks associated with deficit thinking and ability grouping. Baseline data on participants’ beliefs about differentiation and AI were collected through surveys. During the second phase (Weeks 2 to 6), participants engaged with AI-supported planning tools, including ChatGPT-4o, and critically examined how these systems generated differentiated content and grouping recommendations. Reflection activities encouraged them to consider the potential biases embedded in such algorithmic outputs.

In the third phase (Weeks 7 to 10), participants used AI tools to design two differentiated lesson plans. These artefacts were accompanied by reflective journals in which participants documented their decision-making processes, their interactions with AI, and the influence of the tools on their pedagogical reasoning. The final phase (Weeks 11 to 12) focused on consolidation and transformation. Participants completed a follow-up survey to capture post-intervention beliefs and attitudes, allowing comparison with baseline measures to identify shifts in understanding and professional identity.

2.3. Data Sources and Collection

Data were drawn from multiple sources to enable rich, triangulated Analysis of both pedagogical products and reflective processes. A total of 123 lesson plans, two per participant, were collected and evaluated for cognitive depth, flexibility of differentiation, and alignment with inclusive pedagogy frameworks. Sixty reflective journals provided detailed insight into participants’ reasoning, their engagement with AI tools, and the evolution of their assumptions about ability and equity.

Pre- and post-intervention surveys were administered to measure attitudinal shifts regarding differentiation, perceived AI authority, and bias awareness. Focus groups complemented these data by providing dialogic spaces for critical discussion. Three tutorial groups, comprising approximately thirty-six participants across three cohorts, met six times during the intervention period, resulting in eighteen recorded and transcribed sessions. These focus group discussions enabled the exploration of collective sense-making and peer learning as participants confronted the ethical and practical challenges of AI integration.

Finally, observation notes and researcher memos documented the contextual and interpersonal dimensions of the study, including classroom dynamics, emergent tensions, and moments of critical reflection. Together, these complementary data sources captured the complexity of pre-service teachers’ encounters with AI-supported differentiation, offering a robust foundation for the multi-layered analyses presented in the following sections.

2.4. Analytical Strategies

A suite of integrated analytical methods, each aligned with the study’s critical-theoretical framework, was employed to capture the interplay between discourse, belief, and pedagogical action. These methods were not treated as discrete stages but as interconnected strands of inquiry that collectively illuminated how pre-service teachers engaged with, interpreted, and were transformed by their use of AI-supported differentiation tools. The combination of qualitative and quantitative analyses provided a robust triangulation of perspectives, enhancing both the interpretive depth and empirical validity of the study.

Critical Discourse Analysis [18] was applied to examine how participants linguistically constructed learners and rationalised their differentiation strategies. Through close reading of lesson plans and reflective commentaries, this Analysis identified the reproduction and disruption of deficit discourses, particularly those expressed through hierarchical labels such as “low,” “average,” and “high” groups. CDA revealed how teachers positioned themselves in relation to AI-generated recommendations, sometimes deferring to algorithmic authority, at other times resisting it by reframing differentiation in more inclusive and equitable terms. In this sense, the discourse analysis operated both diagnostically and critically, uncovering the ideological dimensions of pedagogical language and the subtle ways algorithmic reasoning infiltrated teacher discourse.

Complementing this, Thematic Analysis [19] was used to identify recurring patterns and evolving themes across reflective journals and focus group transcripts. Following Braun and Clarke’s six-phase approach, the Analysis moved from initial familiarisation and inductive coding to the refinement of themes that captured shifts in belief and professional identity. Themes such as “AI as authority,” “discomfort with categorisation,” and “emerging critical awareness” reflected participants’ growing recognition of the ethical and pedagogical complexities of AI integration. These themes were interpreted not merely as descriptive outcomes but as developmental trajectories illustrating the process of critical consciousness formation within teacher education.

Lesson plans were also evaluated through a rubric-based framework designed to measure the inclusivity and sophistication of pedagogical design. The rubric drew on Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy to assess task complexity, inclusive pedagogy [5] to evaluate flexibility and responsiveness, and Universal Design for Learning principles [4] to gauge accessibility and learner agency. Each lesson plan was independently reviewed and rated for cognitive demand, openness of learning pathways, and alignment with inclusive principles. These rubric scores provided a structured means of quantifying pedagogical growth and supported comparative Analysis across cohorts and data cycles, offering an empirical complement to the interpretive findings.

To assess measurable shifts in participants’ beliefs, descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were conducted on pre- and post-intervention survey data (Appendix A). Paired-sample t-tests were used to determine significant changes in attitudes toward differentiation, ability, and AI authority, while effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to evaluate the magnitude of these changes. These statistical analyses revealed clear patterns of conceptual development, demonstrating that participants’ exposure to critical reflection and AI-supported planning tools led to meaningful shifts in their perceptions of equity, bias, and pedagogical autonomy.

The integration of these analytical strategies created a multi-perspectival framework capable of addressing both the observable and the ideological dimensions of pedagogical practice. By linking discourse-level Analysis to quantitative measures of change, the study achieved methodological coherence with its critical action research orientation. This integrated design not only documented transformation but also enacted it, using data as both evidence and instrument of participants’ growing critical awareness and professional agency.

2.5. Validity, Reflexivity, and Ethical Considerations

Ensuring trustworthiness and methodological integrity was central to the analytical process. Triangulation across multiple data sources, lesson plans, reflective journals, surveys, and focus group transcripts, enhanced the credibility of interpretations and mitigated the limitations of any single method. The convergence of qualitative and quantitative evidence allowed for both theoretical generalisation and empirical validation of participants’ shift in understanding. Reflexivity was embedded throughout the Analysis, with the researcher maintaining a continuous audit trail of coding decisions, interpretive memos, and methodological reflections. This reflexive stance acknowledged the researcher’s dual position as educator and investigator, ensuring that analytical insights were grounded in participants’ authentic experiences rather than imposed assumptions. Member checking and peer debriefing further strengthened confirmability, allowing participants and critical colleagues to verify emerging interpretations. Collectively, these practices ensured that the analytical framework remained faithful to the principles of critical action research, valuing transparency, dialogue, and transformation as essential components of rigour.

Building upon these analytical foundations, the following section presents the findings derived from this multi-layered inquiry. It integrates quantitative patterns and qualitative insights to illustrate how pre-service teachers engaged with AI-supported differentiation, how their discourses and beliefs evolved across the intervention, and how these transformations reflected broader tensions between efficiency, equity, and professional agency in teacher education. Through this synthesis, the findings illuminate both the visible shifts in pedagogical practice and the deeper ideological negotiations occurring within the reflective cycles of critical action research.

3. Results

The findings presented in this section integrate quantitative, qualitative, and interpretive insights to illuminate how pre-service teachers engaged with AI-supported lesson planning and how these engagements reflected, reproduced, or resisted patterns of bias and micro-streaming. The results are organised around three interrelated foci: (1) evidence of bias and stratification within lesson design, (2) shifts in participants’ beliefs and digital pedagogical awareness, and (3) reflective accounts of professional transformation and tension. Collectively, these findings trace participants’ movement from uncritical reliance on algorithmic guidance toward a more self-aware and equity-oriented stance on differentiation.

3.1. Quantitative Analysis of Lesson Plans

The Analysis of 123 lesson plans provided an empirical foundation for examining how participants enacted differentiation in AI-supported designs. Each plan was assessed using a rubric measuring task complexity, flexibility of differentiation, and alignment with inclusive pedagogy, drawing, respectively, from Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy, Universal Design for Learning [4], and inclusive pedagogy frameworks [5].

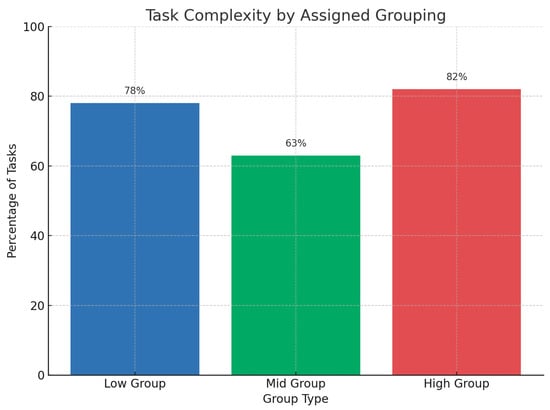

The quantitative results revealed a strong pattern of fixed-tiered differentiation, with 87 per cent of lesson plans employing explicit “low,” “mid,” and “high” ability groupings (Table 1). Across these tiers, cognitive task levels showed a clear hierarchical distribution: “low” groups were assigned predominantly recall and comprehension-level tasks (78 per cent), “mid” groups were centred on application and Analysis (63 per cent), and “high” groups on evaluation and creation (82 per cent). Only 12 per cent of plans incorporated flexible or open-ended differentiation, such as student choice in task selection, multimodal engagement, or self-paced challenge levels (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of Evaluation Criteria for AI-Supported Differentiated Lesson Plans.

Table 2.

Distribution of Cognitive Task Levels Across Differentiated Group Types.

These patterns indicate that differentiation was primarily conceptualised as stratification rather than responsive adaptation. The data reveal a tight coupling between perceived learner ability and cognitive demand, suggesting that AI-supported differentiation reinforced a sorting logic more aligned with traditional streaming than with inclusive pedagogy. From a critical perspective, this tendency exemplifies the “technologies of inequality” described by Watters [6], where algorithmic scaffolds replicate deficit framings under the guise of efficiency.

Participants’ reflective comments and rubric results suggested that many accepted AI-generated templates as legitimate pedagogical structures. The “seductive authority” of algorithmic recommendations, offering neatly packaged differentiation schemes, appeared to displace teachers’ reflective judgement. In these instances, AI acted as both cognitive aid and ideological conduit, embedding assumptions about learner capability that participants often failed to question. Figure 1 summarises the distribution of task complexity across group types, illustrating a systematic decline in cognitive challenge aligned with perceived ability.

Figure 1.

Task Complexity by Assigned Grouping.

Nevertheless, a small subset of lesson plans provided evidence of resistance. The 12 per cent demonstrating flexible differentiation practices incorporated open-ended inquiry tasks, tiered supports without ability labels, and multimodal assessment options. These plans exemplified designing for diversity rather than ability, signalling a nascent but significant shift toward inclusive design principles. Within the iterative action research cycles, this minority group served as exemplars that stimulated critical reflection among peers, catalysing recognition of how differentiation might operate as empowerment rather than exclusion.

3.2. Shifts in Pre-Service Teacher Beliefs

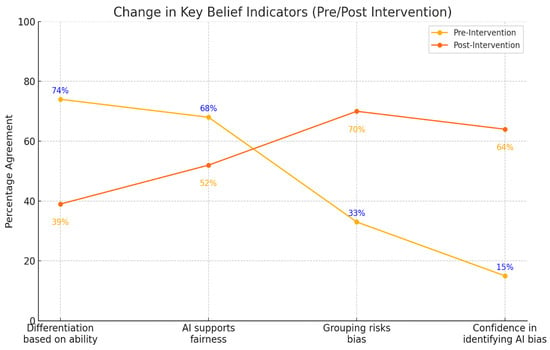

Survey data collected before and after the intervention revealed statistically significant and educationally meaningful changes in participants’ beliefs about differentiation, ability, and AI. Table 3 summarises these changes, showing both the direction and magnitude of belief shifts.

Table 3.

Changes in Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About Differentiation and AI Bias (With 95% Confidence Intervals).

Participants’ endorsement of ability-based differentiation declined sharply from 74 per cent to 39 per cent (d = 0.92, p < 0.001). Belief that AI tools can help differentiate fairly also declined from 68 per cent to 52 per cent (d = 0.44, p < 0.05), suggesting emerging scepticism toward algorithmic authority (Figure 2). Meanwhile, agreement that grouping risks reinforcing bias rose from 33 per cent to 70 per cent (d = 0.95, p < 0.001), and confidence in identifying AI bias increased dramatically from 15 per cent to 64 per cent (d = 1.05, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Changes in Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About Differentiation and AI Bias Pre- and Post-Intervention.

These data indicate a significant reorientation in participants’ pedagogical and ethical awareness. Exposure to critical digital pedagogy, combined with reflective examination of their own AI-mediated lesson plans, cultivated greater critical digital literacy and heightened awareness of how technology mediates equity. The magnitude of change across multiple indicators demonstrates that the reflective cycles embedded within the critical action research design were not merely cognitive but transformative, shifting participants’ dispositions from acceptance to interrogation of AI authority.

Importantly, these quantitative findings should not be read as an unproblematic success narrative. Rather, they highlight the productive friction between participants’ initial trust in AI efficiency and their emerging recognition of its potential for bias. This tension became a key site of learning within the study, one that bridged the cognitive and affective dimensions of professional formation in teacher education.

3.3. Thematic Analysis of Reflective Journals

Qualitative Analysis of 60 reflective journals uncovered three major themes that captured participants’ evolving relationships with AI, differentiation, and pedagogical agency. These were AI as Authority, Discomfort with Deficit Framing, and Evolving Critical Awareness.

The first theme, AI as Authority, was pervasive in early reflections. Many participants described deferring to AI-generated groupings or task recommendations, viewing them as objective or pedagogically sound. One participant noted, “The AI already had the tasks grouped, I figured that must be best.” This reveals how the epistemic authority of AI shaped decision-making, normalising deficit-based assumptions about learner capability.

The second theme, Discomfort with Deficit Framing, marked a turning point in reflective awareness. As participants examined their own lesson designs through the lens of inclusive pedagogy, they began to recognise how apparently neutral differentiation practices reproduced streaming. One journal reflected, “I realised I was assigning easier tasks based on who I thought wouldn’t ‘cope’, but isn’t that what streaming does?” Such comments indicate an emerging ability to identify and problematise the ideological underpinnings of everyday pedagogical choices.

The third theme, Evolving Critical Awareness, reflected a growing willingness to challenge AI suggestions and reclaim professional agency. By the end of the intervention, several participants described using AI as a starting point for creative adaptation rather than a prescriptive guide. One participant wrote, “I started using the AI just as a base, but I added open options for students to choose how to show what they learned.” This shift from compliance to critique represents a core outcome of the study: the development of reflective practitioners capable of negotiating rather than obeying algorithmic authority.

3.4. Focus Group Insights

Focus group discussions provided additional texture to the survey and journal findings, revealing both cognitive and emotional dimensions of participants’ engagement with AI. Across 18 sessions, participants described the AI tools as “helpful but seductively simple,” acknowledging their utility while expressing unease about their ethical and pedagogical implications. The perceived efficiency of AI-suggested differentiation was often contrasted with feelings of discomfort or guilt, one participant observed, “The AI made it so easy to label groups, but I didn’t feel good about it.”

These discussions illuminated an important pedagogical tension between efficiency and equity. Participants recognised the time-saving and organisational affordances of AI but simultaneously sensed that such convenience came at the cost of professional judgement and moral responsibility. The resulting emotional dissonance, trusting a tool while doubting its ethics, became a critical driver of reflexivity. Several participants expressed a desire for explicit training on how to critique and adapt AI outputs, signalling that critical digital literacy should be positioned as a core teacher education competency.

The focus group data also underscored the relational and communal aspects of critical learning. As participants discussed their design choices and biases collectively, they co-constructed new understandings of inclusion, technology, and teacher agency. These dialogic spaces exemplified Freirean praxis in action, spaces where teachers learned not only to reflect on their practice but to reflect with others toward transformation.

3.5. Synthesis of Findings

Taken together, the findings reveal a clear trajectory across the action research cycles: participants initially reproduced ability-based differentiation, influenced by the structure and language of AI systems, but progressively developed the capacity to interrogate these influences. Quantitative data provided evidence of structural bias in lesson design, while qualitative data illuminated the interpretive and emotional processes through which participants recognised and resisted those biases. The integration of these findings underscores the central argument of the study, that the pedagogical value of AI lies not in its efficiency but in its potential to provoke critical reflection, in this case, about power, bias, and inclusion.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal both the promise and peril of integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into pre-service teacher education. While AI-supported lesson planning provided participants with scaffolds to manage complexity and explore differentiation strategies, it also exposed how algorithmic mediation can subtly reinforce long-standing hierarchies of ability, efficiency, and compliance. Through the lens of critical action research, the study examined how pre-service teachers navigated these tensions, tracing their evolving relationships with AI from uncritical acceptance toward reflexive engagement. The discussion below interprets these results through four intersecting dimensions: (1) AI as a vehicle for micro-streaming, (2) developing critical awareness and pedagogical agency, (3) tensions between efficiency and equity, and (4) reframing differentiation as design for all.

4.1. AI as a Vehicle for Micro-Streaming

The predominance of fixed-tiered differentiation within participants’ lesson plans, where 87 per cent of designs explicitly separated learners into “low,” “mid,” and “high” groups, illustrates the insidious persistence of micro-streaming within contemporary teacher education. Despite the use of generative AI, a technology ostensibly designed to personalise learning, these findings demonstrate how algorithmic tools can reproduce the very hierarchies they claim to transcend. As Williamson [7] argues, data-driven personalisation frequently reconfigures historical practices of sorting under the rhetoric of individualisation, embedding a neoliberal logic of efficiency and optimisation in pedagogical decision-making.

The cognitive stratification observed in lesson plan data, where task complexity aligned predictably with perceived ability, reveals how AI outputs can re-inscribe deficit assumptions in subtle ways. Participants’ reflections confirm that AI suggestions often carried an implicit authority: what the system recommended was assumed to be right. This dynamic resonates with Freire’s [13] critique of the “banking model” of education, wherein learners, and, in this case, teachers, are positioned as passive recipients of external knowledge. Here, AI becomes a digital pedagogue that deposits pre-packaged differentiation logics into planning practice, discouraging critical interrogation.

Watters’ [5] notion of the “technologies of inequality” aptly describes this phenomenon. Rather than neutral aids, AI systems participate in a political economy of educational stratification, translating quantitative data into seemingly objective pedagogical prescriptions. Within teacher education, this automation of judgement risks shaping early professional identities around compliance and categorisation rather than critical discernment. The study’s findings thus illustrate that algorithmic support, when unexamined, may function as a contemporary mechanism of streaming, one that operates not through overt labelling, but through the quiet normalisation of differentiated expectations.

4.2. Developing Critical Awareness and Pedagogical Agency

Despite these initial patterns, the study’s critical action research design facilitated significant transformations in participants’ beliefs and dispositions. The large effect sizes observed across survey measures, such as the decline in support for ability-based differentiation (d = 0.92) and the increase in confidence identifying AI bias (d = 1.05), indicate more than superficial attitudinal change. They reflect a deepening of professional consciousness, where participants began to recognise the ideological dimensions of their pedagogical decisions and to reclaim agency from algorithmic authority.

This shift aligns with inclusive pedagogy’s emphasis on professional reflexivity and shared responsibility for learner diversity [5]. Participants moved from viewing differentiation as a process of allocating tasks to one of designing for participation. The reflective cycles embedded within the study created dialogic spaces for what Freire [13] would describe as “conscientisation”, a process through which individuals develop critical awareness of social and structural constraints and act to transform them.

Recent scholarship reinforces the value of such reflective engagement. Ilomäki et al. [11] argue that embedding critical digital literacy in teacher education is essential for developing educators capable of interrogating algorithmic systems rather than simply implementing them. Similarly, Frøsig and Romero [10] propose a framework of hybrid intelligence, where human educators and AI systems collaborate dynamically through critique and adaptation rather than hierarchy. The findings of this study support these perspectives, demonstrating that pre-service teachers can learn to treat AI not as a surrogate for professional judgement but as a provocation for ethical reflection and design innovation.

4.3. Efficiency Versus Equity: The Seductive Simplicity of AI

A recurrent theme across the data was the tension between the efficiency promised by AI tools and the equity demanded by inclusive pedagogy. Participants frequently described the “seductive simplicity” of auto-generated groupings and pre-structured lesson plans, which offered immediate practical benefits but diminished opportunities for pedagogical creativity. This reflects what Selwyn [8] identifies as the automation of teacher labour, a shift toward procedural decision-making governed by digital systems that privilege productivity over moral purpose.

The emotional ambivalence expressed by participants, valuing convenience yet feeling complicit in inequity, reveals the moral weight of technology-mediated teaching. As one participant admitted, “The AI made it so easy to label groups, but I didn’t feel good about it.” Such reflections highlight the affective dimension of teacher agency, demonstrating that professional ethics are experienced as tension, not abstraction. These emotional moments of discomfort, far from being peripheral, are vital to transformative learning. They signal the emergence of ethical self-awareness, the recognition that pedagogical efficiency without equity constitutes a form of harm.

This tension also exposes a critical paradox: AI systems that claim to reduce teacher workload may, in fact, amplify the ethical labour required of teachers to ensure fairness and inclusion. As Freirean praxis suggests, genuine pedagogy demands effortful reflection, not automation. Teacher education must therefore resist framing AI as a solution to workload or differentiation challenges and instead position it as an opportunity to cultivate moral and professional judgement.

4.4. From Deficit Thinking to Design for All

The qualitative findings show that through sustained reflection, participants began to move beyond deficit frameworks toward designing for all learners. The minority of lesson plans (12 per cent) demonstrating flexible, open-ended differentiation reflected early adoption of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles [4]. These educators reframed differentiation as the creation of diverse entry points, flexible outcomes, and learner autonomy, approaches that align with strength-based pedagogy rather than ability labelling.

This progression mirrors Waitoller and King Thorius’s [20] argument that inclusive pedagogy must merge culturally sustaining and universally designed approaches, allowing teachers to respond dynamically to diversity without categorisation. For the participants in this study, AI became a mirror reflecting their assumptions and, when used critically, a tool for unlearning them. The gradual shift toward more inclusive design illustrates the transformative potential of critical digital pedagogy, one that empowers teachers to interrogate the sociotechnical systems shaping their professional practice.

However, the limited uptake of inclusive differentiation also underscores the resilience of institutional and ideological constraints. The deeply embedded association between differentiation and ability persists even in technologically mediated contexts. To disrupt this pattern at scale, teacher education must embed explicit opportunities for co-designing with AI, where teachers critically shape, rather than merely consume, algorithmic recommendations. This requires what Holstein et al. [21] term human-in-the-loop design: models that centre teacher judgement and ethical reasoning within AI development processes.

4.5. Implications for Initial Teacher Education

The study’s findings carry significant implications for how AI is conceptualised and integrated into initial teacher education (ITE). First, AI cannot be positioned merely as a technical skill or digital toolset; it must be framed as a critical literacy, a domain in which teachers learn to interrogate data, algorithms, and their socio-political consequences. Embedding critical digital literacy into ITE curricula would prepare future teachers to recognise bias, resist micro-streaming, and assert agency in technologically mediated classrooms.

Second, professional learning in AI should emphasise reflexivity and ethics rather than compliance and efficiency. Educators must be supported to see AI as a dialogue partner whose outputs require professional judgement and contextual interpretation. This aligns with emerging calls for teacher–AI partnerships grounded in transparency, explainability, and equity [12].

Finally, the findings suggest that ITE programmes must cultivate pedagogical resilience, the capacity of teachers to hold space for uncertainty, question technological assumptions, and design inclusively despite systemic pressures toward efficiency. By integrating critical action research into coursework, teacher education can transform the classroom into a site of ongoing inquiry where AI becomes a catalyst for reflection rather than replication.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides insights into the intersection of AI, differentiation, and teacher education, its scope was limited to one institutional context and discipline area (digital technologies education). Future research could extend these findings through longitudinal studies tracking how early beliefs about AI and inclusion evolve as teachers enter professional practice. Comparative studies across disciplines, cultural contexts, and AI platforms would further clarify how institutional norms mediate teacher engagement with technology.

Additionally, adopting a design-based research (DBR) approach could enable educators and technologists to co-create AI tools that embody inclusive principles from inception. Such participatory co-design aligns with Wang and Hannafin’s [22] conception of DBR as iterative, collaborative, and situated in authentic learning environments. Future work might therefore explore how explainable AI features, participatory algorithms, or teacher-configurable differentiation models could enhance transparency and professional agency in practice.

4.7. Summary

In sum, the study underscores that inclusive and equitable teaching should not be delegated simply to algorithms. AI systems can amplify, but not currently replace, the ethical and relational dimensions of pedagogy. Pre-service teachers must therefore be prepared not only to use AI but to question it, to understand that differentiation, at its core, is not about sorting learners into predefined paths but about opening multiple pathways toward meaningful participation. The findings reaffirm that the most powerful educational technologies are those that invite critical reflection, sustain professional agency, and foreground human values in the design of learning.

5. Conclusions

This study examined how pre-service teachers engaged with artificial intelligence (AI) in lesson planning, exploring how these interactions shaped their pedagogical beliefs and practices concerning differentiation, inclusion, and equity. Using a critical action research methodology, the study revealed both the potential and the peril of AI integration in teacher education. While AI tools offered participants powerful scaffolds for structuring learning activities, they also subtly embedded deficit-based and hierarchical assumptions that reproduced patterns of micro-streaming, the implicit stratification of learners by perceived ability.

The findings demonstrate that even within a cohort explicitly taught inclusive pedagogy, the gravitational pull of ability-based differentiation persisted when mediated through AI. The prevalence of fixed-tiered lesson designs (87 per cent) and the alignment of task complexity with perceived learner ability illustrate how algorithmic systems can legitimise and automate inequality under the guise of personalisation. Yet, within the same learning cycles, participants exhibited significant transformative growth, evidenced by measurable shifts in beliefs, reflective journals, and dialogic inquiry. They increasingly recognised AI’s embedded biases, questioned its authority, and reimagined differentiation as design for diversity rather than a mechanism of classification.

These transformations underscore the critical role of reflexivity, dialogue, and critical digital literacy in preparing teachers for AI-mediated education. When supported through structured reflection, collaborative inquiry, and exposure to ethical Analysis, pre-service teachers can learn not only to identify bias but to resist and redesign the assumptions underpinning it. The study, therefore, contributes to an emerging body of scholarship that positions AI not as a replacement for professional judgement but as a provocation for critical pedagogy, a catalyst for questioning how knowledge, power, and identity are negotiated in digital learning environments.

At a theoretical level, this research advances understandings of how inclusive pedagogy, Freirean praxis, and sociotechnical critique intersect in teacher education. It demonstrates that the future of AI in education will depend less on technological sophistication than on the ethical and reflective capacity of those who use it. Teacher educators must therefore position AI as both object and instrument of inquiry, something to be studied, critiqued, and shaped, not merely adopted.

Practically, the findings call for curriculum redesign within initial teacher education to embed critical digital literacy as a core competency. Courses should integrate explicit training in algorithmic bias, human–AI collaboration, and participatory design to ensure that teachers emerge as active co-creators of equitable technologies. Future research should build on this foundation through design-based and longitudinal studies, exploring how early encounters with AI shape professional identity and inclusive practice over time.

Ultimately, this study reaffirms a central truth: education’s ethical core cannot be easily automated. The challenge is not to humanise AI but to sustain humanity in teaching in order to ensure that every encounter with technology strengthens, rather than diminishes, teachers’ capacity to act critically, compassionately, and inclusively.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Griffith University (protocol code 2023/45 31 December 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CDA | Critical Discourse Analysis |

| DBR | Design-Based Research |

| ITE | Initial Teacher Education |

| ZPD | Zone of Proximal Development |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Survey Data and Confidence Interval Calculations

A paired-sample design was employed using pre- and post-intervention surveys completed by the same group of participants (n = 60). The survey measured changes in beliefs related to differentiation, bias, and AI use in lesson planning. Raw frequencies were rounded to the nearest whole participant for clarity.

Table A1.

Survey Statement Counts Pre-Post.

Table A1.

Survey Statement Counts Pre-Post.

| Survey Statement | Pre (Count) | Post (Count) |

|---|---|---|

| Differentiation based on ability | ~44 | ~23 |

| AI tools can help me differentiate fairly | ~41 | ~31 |

| Grouping students risks reinforcing bias | ~20 | ~42 |

| I feel confident identifying AI bias | ~9 | ~38 |

Note. Counts represent the number of participants agreeing or strongly agreeing with each statement.

Calculation of Standard Errors and 95% Confidence Intervals

For each survey item, standard errors (SE) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the following formula:

where p represents the proportion of participants agreeing with the statement, and n = 60.

Example (First Statement, Pre-Survey):

Proportion agreeing (p) = 0.74

CI = 0.74 ± (1.96 × 0.0566) = 0.74 ± 0.111

Hence, the 95% confidence interval for the proportion agreeing with the statement “Differentiation based on ability” in the pre-survey is (0.63, 0.85), or 63% to 85% when rounded to two decimal places.

This process was applied consistently across all survey statements to establish the confidence ranges reported in the main findings.

References

- Garzón, J.; Patiño, E.; Marulanda, C. Systematic review of artificial intelligence in education: Trends, benefits, and challenges. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J.; Cook, M. The Origins of Intelligence in Children; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.H.; Meyer, A. Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning; Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development: Arlington, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Florian, L.; Black-Hawkins, K. Exploring inclusive pedagogy. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 37, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, A. Technologies of Individualisation Are Technologies of Inequality. Second Breakfast. 2025. Available online: https://2ndbreakfast.audreywatters.com/technologies-of-individualization-are-technologies-of-inequality/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Williamson, B. Big Data in Education: The Digital Future of Learning, Policy and Practice; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J. Artificial intelligence and education in China. Learning, Media Technol. 2020, 45, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. Should Robots Replace Teachers? AI and the Future of Education; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Frøsig, T.B.; Romero, M. Teacher agency in the age of generative AI: Towards a framework of hybrid intelligence for learning design. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilomäki, L.; Lakkala, M.; Paavola, S. Critical digital literacies at school level: A systematic review. Rev. Educ. 2022, 10, e3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eynon, R.; Young, E. Methodology, legend, and rhetoric: The constructions of AI by academia, industry, and policy groups for lifelong learning. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2021, 46, 166–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Herder & Herder: Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, J.W. The entanglement of racism and Individualism: The U.S. National Defence Education Act of 1958 and the individualisation of “intelligence” and educational policy. Multiethnica 2018, 38, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R.; Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban Rev. 1968, 3, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, K.E. Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. J. Educ. 2009, 189, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic Analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitoller, F.R.; King Thorius, K.A. Cross-pollinating culturally sustaining pedagogy and universal design for learning: Toward an inclusive pedagogy that accounts for dis/ability. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2016, 86, 366–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, K.; Wortman Vaughan, J.; Daumé, H., III; Dudik, M.; Wallach, H. Improving fairness in machine learning systems: What do industry practitioners need? In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2019, Scotland, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hannafin, M.J. Design-based research and technology-enhanced learning environments. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2005, 53, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.