Computer Vision for Fashion: A Systematic Review of Design Generation, Simulation, and Personalized Recommendations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We present a comprehensive examination of the latest advancements in fashion research, categorizing research topics into three main domains: generative, simulative, and recommender.

- Within each of these intelligent fashion research categories, we offer a comprehensive and well organized review of the most notable methods and their corresponding contributions.

- We compile evaluation metrics tailored to diverse problems and provide performance comparisons across various methods.

- We delineate prospective avenues for future exploration that can foster further progress and serve as a source of inspiration for the research community.

2. Methodology Overview

2.1. Research Questions

2.2. Search Strategy

("computer vision" OR "deep learning" OR "machine learning" OR "neural network*" OR "CNN" OR "GAN" OR "generative adversarial network*" OR "transformer*" OR "diffusion model*") AND ("fashion" OR "clothing" OR "apparel" OR "garment*" OR "textile*" OR "style" OR "outfit*" OR "fashion design") AND ("generative" OR "simulation" OR "recommend*" OR "virtual try-on" OR "synthesis" OR "style transfer" OR "fashion generation" OR "personalization" OR "virtual fitting")

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Data Extraction

- Publication details (authors, year, venue, publisher)

- Application domain (generative, simulative, or recommender systems)

- Computer vision techniques and architectures employed

- Datasets used for training and evaluation

- Evaluation metrics and performance results

- Key findings and contributions

- Reported limitations and future research directions

2.6. Quality Assessment

- Clarity of research objectives: Clear problem definition and research goals

- Methodological rigor: Appropriate choice of computer vision techniques and experimental design

- Evaluation validity: Use of standard datasets, appropriate metrics, and comparison with baselines

- Reproducibility: Sufficient implementation details and availability of code or models

- Significance of contribution: Novel approaches or substantial improvements over existing methods

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Generative Fashion

3.1. Fashion Synthesis

3.1.1. Clothing Synthesis

3.1.2. Jewelry Synthesis

3.1.3. Facial Synthesis

3.2. Outfit Generation

3.2.1. Outfit Generative Models

3.2.2. Outfit Style Transfer Models

3.3. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Directions

4. Simulative Fashion

4.1. Virtual Try-On

4.1.1. Image-Based Methods

4.1.2. Video-Based Methods

4.1.3. 3D Model-Based Methods

4.2. Cloth Simulation

4.2.1. Physics-Based Modeling

| Technique | Fidelity | Stability | Interactivity | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBD [133] | Medium | High | High | Medium |

| MPM [137] | High | Medium | Medium | High |

| FEM [140] | High | Medium | Low | Low |

| XPBD [134] | High | High | Medium | Medium |

| Cloth MPM [140] | Medium | High | High | Medium |

| Hybrid Methods [138] | High | Medium | Medium | High |

| Paper | Year | Runtime (ms) | Particles/Elements | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [133] | 2007 | 16 | 5 K particles | Cloth |

| [136] | 2013 | 80 | 1 M particles | Snow |

| [134] | 2016 | 25 | 10 K particles | Cloth |

| [137] | 2016 | 120 | 2 M particles | General MPM |

| [139] | 2018 | 45 | 500 K particles | Fluids |

| [138] | 2018 | 95 | 100 K particles | Thin shells |

4.2.2. Real-Time Simulation

4.3. Challenges and Future Outlook

5. Recommender Fashion

5.1. Outfit Learning Recommendation

5.1.1. Single-Item Recommenders

5.1.2. Outfit Style Recommenders

5.2. Context-Aware Recommendation

5.2.1. Occasion-Based Recommendation Systems

5.2.2. Climate-Adaptive Fashion Recommendation

5.3. Open Challenges and Future Research Directions

6. Open-Source Resources and Pre-Trained Models

6.1. Key Datasets with Public Access

- DeepFashion [32]: 800 K images with rich annotations. http://mmlab.ie.cuhk.edu.hk/projects/DeepFashion.html (accessed on 10 December 2025)

- Fashion-MNIST [33]: 70 K grayscale clothing images. https://github.com/zalandoresearch/fashion-mnist (accessed on 10 December 2025)

- Fashion-Gen [35]: 293 K images with text descriptions. Dataset access through original authors.

- ModaNet [37]: 55 K street fashion images with polygon annotations. https://github.com/eBay/modanet (accessed on 10 December 2025)

- VITON-HD [3]: 13 K high-resolution virtual try-on pairs. https://github.com/shadow2496/VITON-HD (accessed on 10 December 2025)

- CLOTH3D [34]: 100 K 3D garment meshes with simulation data. https://chalearnlap.cvc.uab.cat/dataset/38/description (accessed on 10 December 2025)

- Fashionpedia [36]: 48 K images with fine-grained attributes. https://fashionpedia.github.io/home (accessed on 10 December 2025)

- DressCode [41]: 53 K multi-category virtual try-on images. https://github.com/aimagelab/dress-code (accessed on 10 December 2025)

- DeepFashion2 [168]: 491 K images with pose and segmentation annotations. https://github.com/switchablenorms/DeepFashion2 (accessed on 10 December 2025)

- Polyvore (archived): 21 K outfit sets for compatibility learning. https://github.com/xthan/polyvore (accessed on 10 December 2025)

6.2. Pre-Trained Models for Transfer Learning

6.3. Computational Requirements

7. Cross-Domain Integration and Synergies

7.1. Generative-Simulative Integration

7.2. Generative-Recommender Integration

7.3. Simulative-Recommender Integration

7.4. Tri-Domain Integration

- Discovery (Recommender): Context-aware systems suggest occasions and style directions based on user preferences and contextual signals.

- Customization (Generative): Users modify suggestions or generate personalized designs through text descriptions or style transfer.

- Validation (Simulative): Virtual try-on with physics-based simulation confirms fit and appearance before purchase.

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, W.H.; Song, S.; Chen, C.Y.; Hidayati, S.C.; Liu, J. Fashion meets computer vision: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Yu, R.; Davis, L.S. Viton: An image-based virtual try-on network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7543–7552. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Park, S.; Lee, M.; Choo, J. Viton-hd: High-resolution virtual try-on via misalignment-aware normalization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 14131–14140. [Google Scholar]

- Santesteban, I.; Otaduy, M.A.; Casas, D. Learning-based animation of clothing for virtual try-on. Comput. Graph. Forum 2019, 38, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahner, Z.; Cremers, D.; Tung, T. Deepwrinkles: Accurate and realistic clothing modeling. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 667–684. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.; Hu, Y. FashionNet: Personalized outfit recommendation with deep neural network. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.02443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Lai, Z.; Mok, P.; Chua, T.S. Computational technologies for fashion recommendation: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deldjoo, Y.; Nazary, F.; Ramisa, A.; Mcauley, J.; Pellegrini, G.; Bellogin, A.; Noia, T.D. A review of modern fashion recommender systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Hoque, M.S.; Rahman Jeem, N.; Biswas, M.C.; Bardhan, D.; Lobaton, E. Fashion recommendation systems, models and methods: A review. Informatics 2021, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.O.; Kalhor, A. Smart fashion: A review of AI applications in the Fashion & Apparel Industry. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Khalid, L. Aesthetics, personalization and recommendation: A survey on deep learning in fashion. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.08301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Ni, B.; Yu, Z. Joint global and dynamic pseudo labeling for semi-supervised point cloud sequence segmentation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 5679–5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.; Rivas-Echeverría, F.; Pérez, A.G.; Casas, E. Artificial intelligence and sustainability in the fashion industry: A review from 2010 to 2022. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, F.; Wei, H.; Xu, L. Deep learning method for makeup style transfer: A survey. Cogn. Robot. 2021, 1, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Indolia, S.; Goswami, A.K.; Mishra, S.P.; Asopa, P. Conceptual understanding of convolutional neural network-a deep learning approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 132, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Qian, R.; Dong, C.; Liu, S.; Yan, Q.; Zhu, W.; Lin, L. Beautygan: Instance-level facial makeup transfer with deep generative adversarial network. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 22–26 October 2018; pp. 645–653. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.; Lu, J.; Yu, F.; Finkelstein, A. Pairedcyclegan: Asymmetric style transfer for applying and removing makeup. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, S.; Gao, C.; Cao, J.; He, R.; Feng, J.; Yan, S. Psgan: Pose and expression robust spatial-aware gan for customizable makeup transfer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 5194–5202. [Google Scholar]

- Tugwell, P.; Tovey, D. PRISMA 2020. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, A5–A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, J.A. Exploiting latent codes: Interactive fashion product generation, similar image retrieval, and cross-category recommendation using variational autoencoders. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.01053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Park, H.; Lee, Y.; Kang, J.; Chun, J. Developing parametric design fashion products using 3D printing technology. Fash. Text. 2021, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, Z.; You, A.; Bai, X. Semantically multi-modal image synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 5467–5476. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Urtasun, R.; Fidler, S.; Lin, D.; Change Loy, C. Be your own prada: Fashion synthesis with structural coherence. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1680–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Tian, J.; Li, G.; Wu, C.H.; King, E.K.; Chen, K.T.; Hsieh, S.H.; Xu, C. Tailorgan: Making user-defined fashion designs. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Snowmass Village, CO, USA, 1–5 March 2020; pp. 3241–3250. [Google Scholar]

- Jetchev, N.; Bergmann, U. The conditional analogy gan: Swapping fashion articles on people images. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2287–2292. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, W.; Sangkloy, P.; Agrawal, V.; Raj, A.; Lu, J.; Fang, C.; Yu, F.; Hays, J. Texturegan: Controlling deep image synthesis with texture patches. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 8456–8465. [Google Scholar]

- Abdellaoui, S.; Kachbal, I. Apparel E-commerce background matting. Int. J. Adv. Res. Eng. Technol. (IJARET) 2021, 12, 421–429. [Google Scholar]

- El Abdellaoui, S.; Kachbal, I. Deep residual network for high-resolution background matting. Stud. Inf. Control 2021, 30, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Abdellaoui, S.; Kachbal, I. Deep background matting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart City Applications, Castelo Branco, Portugal, 19–21 October 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 523–532. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Luo, P.; Qiu, S.; Wang, X.; Tang, X. Deepfashion: Powering robust clothes recognition and retrieval with rich annotations. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1096–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H.; Rasul, K.; Vollgraf, R. Fashion-mnist: A novel image dataset for benchmarking machine learning algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.07747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertiche, H.; Madadi, M.; Escalera, S. Cloth3d: Clothed 3d humans. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 344–359. [Google Scholar]

- Rostamzadeh, N.; Hosseini, S.; Boquet, T.; Stokowiec, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jauvin, C.; Pal, C. Fashion-gen: The generative fashion dataset and challenge. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.08317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Shi, M.; Sirotenko, M.; Cui, Y.; Cardie, C.; Hariharan, B.; Adam, H.; Belongie, S. Fashionpedia: Ontology, segmentation, and an attribute localization dataset. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 316–332. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Yang, F.; Kiapour, M.H.; Piramuthu, R. Modanet: A large-scale street fashion dataset with polygon annotations. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 22–26 October 2018; pp. 1670–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Sun, Q.; Georgoulis, S.; Van Gool, L.; Schiele, B.; Fritz, M. Disentangled person image generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Minar, M.R.; Tuan, T.T.; Ahn, H.; Rosin, P.; Lai, Y.K. Cp-vton+: Clothing shape and texture preserving image-based virtual try-on. In Proceedings of the CVPR Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; Volume 3, pp. 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, R.; Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Zuo, W.; Luo, P. Towards photo-realistic virtual try-on by adaptively generating-preserving image content. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 7850–7859. [Google Scholar]

- Davide, M.; Matteo, F.; Marcella, C.; Federico, L.; Fabio, C.; Rita, C. Dress code: High-resolution multi-category virtual try-on. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Ho, H.I.; Guo, C.; Rong, B.; Grigorev, A.; Song, J.; Zarate, J.J.; Hilliges, O. 4d-dress: A 4d dataset of real-world human clothing with semantic annotations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 550–560. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zheng, H.; Liang, X.; Chen, Y.; Lin, L.; Yang, M. Toward characteristic-preserving image-based virtual try-on network. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 589–604. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, X.; Xie, Z.; Wu, B.; Yin, J. Fashion editing with adversarial parsing learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 8120–8128. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, G.; Jetchev, N.; Vollgraf, R.; Bergmann, U. Generating high-resolution fashion model images wearing custom outfits. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.R.; Liu, Q.; Gao, C.Y.; Su, Z. FashionGAN: Display your fashion design using conditional generative adversarial nets. Comput. Graph. Forum 2018, 37, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.M.; Varadharajan, S.; Kemelmacher-Shlizerman, I. Tryongan: Body-aware try-on via layered interpolation. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2021, 40, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patashnik, O.; Wu, Z.; Shechtman, E.; Cohen-Or, D.; Lischinski, D. Styleclip: Text-driven manipulation of stylegan imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2085–2094. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, K.Y.; Qian, C.; Loy, C.C.; Wu, W.; Liu, Z. Stylegan-human: A data-centric odyssey of human generation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K.; Damani, S.; Narahari, K.N. Using AI to Design Stone Jewelry. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.08759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wen, H. Jewelry Art Modeling Design Method Based on Computer-Aided Technology. Adv. Multimed. 2022, 2022, 4388128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sarma, S.E.; Bronstein, M.M.; Solomon, J.M. Dynamic graph cnn for learning on point clouds. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2019, 38, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.R.; Su, H.; Mo, K.; Guibas, L.J. Pointnet: Deep learning on point sets for 3d classification and segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 652–660. [Google Scholar]

- Biasotti, S.; Cerri, A.; Bronstein, A.; Bronstein, M. Recent trends, applications, and perspectives in 3d shape similarity assessment. Comput. Graph. Forum 2016, 35, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, D.W.; Park, S.W.; Kwon, J. 3d point cloud generative adversarial network based on tree structured graph convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3859–3868. [Google Scholar]

- Achlioptas, P.; Diamanti, O.; Mitliagkas, I.; Guibas, L. Learning representations and generative models for 3d point clouds. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.; Jun, H.; Dhariwal, P.; Mishkin, P.; Chen, M. Point-e: A system for generating 3d point clouds from complex prompts. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.08751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröppel, P.; Wewer, C.; Lenssen, J.E.; Ilg, E.; Brox, T. Neural point cloud diffusion for disentangled 3d shape and appearance generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 8785–8794. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q. Makeup Transfer Using Generative Adversarial Network. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bougourzi, F.; Dornaika, F.; Barrena, N.; Distante, C.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. CNN based facial aesthetics analysis through dynamic robust losses and ensemble regression. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 10825–10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, J. Stablemakeup: When real-world makeup transfer meets diffusion model. In Proceedings of the Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques Conference Conference Papers, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–14 August 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Xiong, S.; Chen, Y.; Du, F.; Chen, W.; Wang, F.; Rong, Y. Shmt: Self-supervised hierarchical makeup transfer via latent diffusion models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 16016–16042. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; Li, H.; Ning, X.; Li, Q. BeautyDiffusion: Generative latent decomposition for makeup transfer via diffusion models. Inf. Fusion 2025, 123, 103241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, S.; Li, L.; Gong, Y.; Wang, H.; Cheng, B.; Ma, Y.; Wu, L.; Wu, X.; Leng, D.; et al. FLUX-Makeup: High-Fidelity, Identity-Consistent, and Robust Makeup Transfer via Diffusion Transformer. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.05069. [Google Scholar]

- Lebedeva, I.; Guo, Y.; Ying, F. MEBeauty: A multi-ethnic facial beauty dataset in-the-wild. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 14169–14183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, D.; Zhang, J.; Jain, A.K. Advfaces: Adversarial face synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Joint Conference on Biometrics (IJCB), Houston, TX, USA, 28 September–1 October 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.Y.; Jin, H.; Wu, L. Protecting facial privacy: Generating adversarial identity masks via style-robust makeup transfer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 15014–15023. [Google Scholar]

- Dabouei, A.; Soleymani, S.; Dawson, J.; Nasrabadi, N. Fast geometrically-perturbed adversarial faces. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 7–11 January 2019; pp. 1979–1988. [Google Scholar]

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.06083. [Google Scholar]

- Elsheikh, R.A.; Mohamed, M.; Abou-Taleb, A.M.; Ata, M.M. Accuracy is not enough: A heterogeneous ensemble model versus FGSM attack. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 8355–8382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroff, F.; Kalenichenko, D.; Philbin, J. Facenet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 815–823. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Wen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, M.; Raj, B.; Song, L. Sphereface: Deep hypersphere embedding for face recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Guo, J.; Xue, N.; Zafeiriou, S. Arcface: Additive angular margin loss for deep face recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 4690–4699. [Google Scholar]

- Veit, A.; Kovacs, B.; Bell, S.; McAuley, J.; Bala, K.; Belongie, S. Learning visual clothing style with heterogeneous dyadic co-occurrences. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 4642–4650. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, Y.G.; Davis, L.S. Learning fashion compatibility with bidirectional lstms. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Mountain View, CA, USA, 23–27 October 2017; pp. 1078–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Vasileva, M.I.; Plummer, B.A.; Dusad, K.; Rajpal, S.; Kumar, R.; Forsyth, D. Learning type-aware embeddings for fashion compatibility. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 390–405. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Du, X.; Wang, M. Learning to match on graph for fashion compatibility modeling. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, L. Dressing as a whole: Outfit compatibility learning based on node-wise graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, T.; Goto, R. Outfit generation and style extraction via bidirectional lstm and autoencoder. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.03133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Gong, X.; Wei, Y.; Luo, P. Ocphn: Outfit compatibility prediction with hypergraph networks. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Chen, L.; Xiao, J.; Chua, T.S. Hierarchical fashion graph network for personalized outfit recommendation. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, 25–30 July 2020; pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, W.L.; Katsman, I.; Wu, C.Y.; Parikh, D.; Grauman, K. Fashion++: Minimal edits for outfit improvement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 5047–5056. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, D. Clothing generation by multi-modal embedding: A compatibility matrix-regularized GAN model. Image Vis. Comput. 2021, 107, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Huang, R.; Huang, W. GD-StarGAN: Multi-domain image-to-image translation in garment design. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, H.; Yang, K.; Liu, L.; Yan, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, S. Learning to synthesize compatible fashion items using semantic alignment and collocation classification: An outfit generation framework. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 5226–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Ji, Y.; Wu, Q.J. Toward AI fashion design: An Attribute-GAN model for clothing match. Neurocomputing 2019, 341, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.; Ojha, U.; Lee, Y.J. Finegan: Unsupervised hierarchical disentanglement for fine-grained object generation and discovery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 6490–6499. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Liu, C.; Forsyth, D. Coherent and controllable outfit generation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.07273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Zhao, N.; Ning, S.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, B.; Han, X. Fashiontex: Controllable virtual try-on with text and texture. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2023 Conference Proceedings, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, J.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, S.; Hao, J.; Zhu, J.; Huang, D. ClotheDreamer: Text-Guided Garment Generation with 3D Gaussians. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.16815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, M. The emergence of deepfake technology: A review. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2019, 9, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Miron, A.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. StyleVTON: A multi-pose virtual try-on with identity and clothing detail preservation. Neurocomputing 2024, 594, 127887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, M.J. Virtual reality in fashion: A systematic review and research agenda. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Z.; Dong, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, D.; Liang, X. Catvton: Concatenation is all you need for virtual try-on with diffusion models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.15886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetya, L.A.; Widiyawati, I.; Rofiudin, A.; Haq, S.T.N.; Hendranawan, R.S.; Permataningtyas, A.; Ichwanto, M.A. The use of CLO3D application in vocational school fashion expertise program: Innovations, challenges and recommendations. J. Res. Instr. 2025, 5, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Alexander, B.; Salavati, L. The impact of experiential augmented reality applications on fashion purchase intention. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkilä, J.; Colley, A.; Roinesalo, P.; Väyrynen, J. Clothing integrated augmented reality markers. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, Stuttgart, Germany, 26–29 November 2017; pp. 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Dacko, S.G. Enabling smart retail settings via mobile augmented reality shopping apps. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 124, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javornik, A.; Rogers, Y.; Moutinho, A.M.; Freeman, R. Revealing the shopper experience of using a “magic mirror” augmented reality make-up application. In Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Brisbane, Australia, 4–8 June 2016; Association for Computing Machinery (ACM): New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 2016, pp. 871–882. [Google Scholar]

- Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S.; Orús, C. The impact of virtual, augmented and mixed reality technologies on the customer experience. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhlin, O.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Andersson, A. Fashionable services for wearables: Inventing and investigating a new design path for smart watches. In Proceedings of the 9th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Gothenburg, Sweden, 23–27 October 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rauschnabel, P.A.; Babin, B.J.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Krey, N.; Jung, T. What is augmented reality marketing? Its definition, complexity, and future. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 1140–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, M.; Rauschnabel, P.A. Understanding the diffusion of virtual reality glasses: The role of media, fashion and technology. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 138, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Hu, X.; Huang, W.; Scott, M.R. Clothflow: A flow-based model for clothed person generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 10471–10480. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, R.; Ge, C.; Liu, W.; Luo, P. Parser-free virtual try-on via distilling appearance flows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 8485–8493. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Fan, H.; Wang, L.; Sheng, L. From parts to whole: A unified reference framework for controllable human image generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.15267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, S. Viton-gan: Virtual try-on image generator trained with adversarial loss. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.07926. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.; Liu, M.Y.; Wang, T.C.; Zhu, J.Y. Semantic image synthesis with spatially-adaptive normalization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2337–2346. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli, D.; Baldrati, A.; Cartella, G.; Cornia, M.; Bertini, M.; Cucchiara, R. Ladi-vton: Latent diffusion textual-inversion enhanced virtual try-on. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 8580–8589. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Zhai, W.; Su, A.; Song, H.; Zhu, K.; Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zha, Z.J. Vivid: Video virtual try-on using diffusion models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.11794. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Chen, P.; Wang, G.; Li, G.; Torr, P.H.; Lin, L. Wildvidfit: Video virtual try-on in the wild via image-based controlled diffusion models. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhong, W.; Yu, W.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yao, T.; Han, J.; Mei, T. Pursuing Temporal-Consistent Video Virtual Try-On via Dynamic Pose Interaction. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 22648–22657. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, Q.Q.V.; Nguyen, K.; Nguyen, R. Swifttry: Fast and consistent video virtual try-on with diffusion models. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 25 February–4March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 6200–6208. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Z.; Chi, X.; Wang, H. Realvvt: Towards photorealistic video virtual try-on via spatio-temporal consistency. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.08682. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, Z.; Xing, L.; Zhai, Z.; Sang, N.; Lan, J.; Xiao, S.; Gao, C. Tunnel try-on: Excavating spatial-temporal tunnels for high-quality virtual try-on in videos. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 3199–3208. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Zhao, F.; Xu, Y.; Dong, X.; Liang, X. Viton-dit: Learning in-the-wild video try-on from human dance videos via diffusion transformers. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.18326. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, T.; Yan, H.; Liu, J. Clothformer: Taming video virtual try-on in all module. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 10799–10808. [Google Scholar]

- Kocabas, M.; Athanasiou, N.; Black, M.J. Vibe: Video inference for human body pose and shape estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 5253–5263. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Liang, X.; Shen, X.; Wu, B.; Chen, B.C.; Yin, J. Fw-gan: Flow-navigated warping gan for video virtual try-on. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1161–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X.; Wu, Z.; Tan, T.; Lin, G.; Wu, Q. Mv-ton: Memory-based video virtual try-on network. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 908–916. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, W.; Chan, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, A.; Liu, S. Gpd-vvto: Preserving garment details in video virtual try-on. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 7133–7142. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, T.; Huang, Z.; Ning, S.; Lin, E.; Liang, C.; Zheng, Z.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, M.; Dong, X. DreamVVT: Mastering Realistic Video Virtual Try-On in the Wild via a Stage-Wise Diffusion Transformer Framework. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.02807. [Google Scholar]

- Song, D.; Li, T.; Mao, Z.; Liu, A.A. SP-VITON: Shape-preserving image-based virtual try-on network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 33757–33769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Liang, X.; Shen, X.; Wang, B.; Lai, H.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Z.; Yin, J. Towards multi-pose guided virtual try-on network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9026–9035. [Google Scholar]

- De Luigi, L.; Li, R.; Guillard, B.; Salzmann, M.; Fua, P. Drapenet: Garment generation and self-supervised draping. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 1451–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Gundogdu, E.; Constantin, V.; Seifoddini, A.; Dang, M.; Salzmann, M.; Fua, P. Garnet: A two-stream network for fast and accurate 3d cloth draping. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 8739–8748. [Google Scholar]

- Bertiche, H.; Madadi, M.; Escalera, S. Neural cloth simulation. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2022, 41, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, T.; Fortunato, M.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Battaglia, P. Learning mesh-based simulation with graph networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual, 26 April–1 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, B.L.; Tiwari, G.; Theobalt, C.; Pons-Moll, G. Multi-garment net: Learning to dress 3d people from images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 5420–5430. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Fang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Peng, S.; Dai, B. Tela: Text to layer-wise 3d clothed human generation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M.; Heidelberger, B.; Hennix, M.; Ratcliff, J. Position based dynamics. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2007, 18, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, M.; Müller, M.; Chentanez, N. XPBD: Position-based simulation of compliant constrained dynamics. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Motion in Games, Burlingame, CA, USA, 10–12 October 2016; pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, B.; Müller, M.; Macklin, M. A survey on position based dynamics. In Proceedings of the EG ’17: Proceedings of the European Association for Computer Graphics: Tutorials, Lyon, France, 24–28 April 2017; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stomakhin, A.; Schroeder, C.; Chai, L.; Teran, J.; Selle, A. A material point method for snow simulation. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2013, 32, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Schroeder, C.; Teran, J.; Stomakhin, A.; Selle, A. The material point method for simulating continuum materials. In Proceedings of the ACM Siggraph 2016 Courses, Anaheim, CA, USA, 24–28 July 2016; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Han, X.; Fu, C.; Gast, T.; Tamstorf, R.; Teran, J. A material point method for thin shells with frictional contact. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2018, 37, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Ge, Z.; Qu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Pradhana, A.; Jiang, C. A moving least squares material point method with displacement discontinuity and two-way rigid body coupling. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2018, 37, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, A.; Zhu, Y.; Xian, C. Efficient cloth simulation based on the material point method. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2022, 33, e2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, S.; Chow, P.; Okuda, H. GPU acceleration for FEM-based structural analysis. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2013, 20, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wang, Z.; Meng, Z.; Yao, J.; Guo, S.; Wang, H. Automated Task Scheduling for Cloth and Deformable Body Simulations in Heterogeneous Computing Environments. In Proceedings of the Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques Conference Conference Papers, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–14 August 2025; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, J.E.; West, M. Discrete mechanics and variational integrators. Acta Numer. 2001, 10, 357–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zhu, S.; Pan, J. Enhanced material point method with affine projection stabilizer for efficient hyperelastic simulations. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 6547–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Batty, C.; Grinspun, E.; Zheng, C. A multi-scale model for simulating liquid-fabric interactions. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2018, 37, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Va, H.; Choi, M.H.; Hong, M. Real-time cloth simulation using compute shader in Unity3D for AR/VR contents. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Ma, J.; Hong, M. Real-Time Cloth Simulation in Extended Reality: Comparative Study Between Unity Cloth Model and Position-Based Dynamics Model with GPU. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Y.; Du, S. GPU-based Real-time Cloth Simulation for Virtual Try-on. In Proceedings of the PG (Short Papers and Posters), Hong Kong, 8–11 October 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Tang, M.; Tong, R.; Cai, M.; Zhao, J.; Manocha, D. P-cloth: Interactive complex cloth simulation on multi-GPU systems using dynamic matrix assembly and pipelined implicit integrators. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2020, 39, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, N.; Knuth, M.; Bender, J.; Kuijper, A. Multilevel Cloth Simulation using GPU Surface Sampling. Virtual Real. Interact. Phys. Simul. 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, L.; Lu, Z.; Long, J.; Yuan, C.; Li, X.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, C.; Yang, Y. Efficient GPU cloth simulation with non-distance barriers and subspace reuse. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.19272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, N.J.; Ma, J.; Kim, T.; Choi, Y.j.; Choi, M.H.; Hong, M. Real-Time Cloth Simulation Using WebGPU: Evaluating Limits of High-Resolution. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.11794. [Google Scholar]

- Yaakop, S.; Musa, N.; Idris, N.M. Digitalized Malay Traditional Neckline Stitches: Awareness and Appreciation of Malay Modern Dressmaker Community. In ASiDCON 2018 Proceeding Book; Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM): Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2018; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Karzhaubayev, K.; Wang, L.P.; Zhakebayev, D. DUGKS-GPU: An efficient parallel GPU code for 3D turbulent flow simulations using Discrete Unified Gas Kinetic Scheme. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2024, 301, 109216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buolamwini, J.; Gebru, T. Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, New York, NY, USA, 23–24 February 2018; pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Arunkumar, M.; Gopinath, R.; Chandru, M.; Suguna, R.; Deepa, S.; Omprasath, V. Fashion Recommendation System for E-Commerce using Deep Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Mandi, India, 24–28 June 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shirkhani, S.; Mokayed, H.; Saini, R.; Chai, H.Y. Study of AI-driven fashion recommender systems. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 4, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachbal, I.; El Abdellaoui, S.; Arhid, K. Revolutionizing fashion recommendations: A deep dive into deep learning-based recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Networking, Intelligent Systems and Security, Meknes, Morocco, 18–19 April 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kachbal, I.; Abdellaoui, S.E.; Arhid, K. Fashion Recommendation Systems: From Single Items to Complete Outfits. Int. J. Comput. Eng. Data Sci. (IJCEDS) 2025, 4, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kachbal, I.; Errafi, I.; Harmali, M.E.; El Abdellaoui, S.; Arhid, K. YOLO-GARNet: A High-Quality Deep Learning System for Garment Analysis and Personalized Fashion Recommendation. Eng. Lett. 2025, 33, 4448. [Google Scholar]

- Landim, A.; Beltrão Moura, J.; de Barros Costa, E.; Vieira, T.; Wanick Vieira, V.; Bazaki, E.; Medeiros, G. Analysing the effectiveness of chatbots as recommendation systems in fashion online retail: A Brazil and United Kingdom cross-cultural comparison. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2025, 16, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewe, L.; Reddy, J.U.; Dasuratha, V.; Rodriguez, J.; Ferreira, N. FashionBody and SmartFashion: Innovative components for a fashion recommendation system. In Proceedings of the Signal Processing, Sensor/Information Fusion, and Target Recognition XXXIV, Orlando, FL, USA, 14–16 April 2025; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025; Volume 13479, pp. 224–239. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Huang, P.; Xu, J.; Guo, X.; Guo, C.; Sun, F.; Li, C.; Pfadler, A.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, B. POG: Personalized outfit generation for fashion recommendation at Alibaba iFashion. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2662–2670. [Google Scholar]

- Suvarna, B.; Balakrishna, S. Enhanced content-based fashion recommendation system through deep ensemble classifier with transfer learning. Fash. Text. 2024, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Feng, F.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, X. Diffusion models for generative outfit recommendation. In Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Washington DC, USA, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 1350–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, S. Fashion Recommendation: Outfit Compatibility using GNN. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi Kiapour, M.; Han, X.; Lazebnik, S.; Berg, A.C.; Berg, T.L. Where to buy it: Matching street clothing photos in online shops. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 3343–3351. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Tang, X.; Luo, P. Deepfashion2: A versatile benchmark for detection, pose estimation, segmentation and re-identification of clothing images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 5337–5345. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, S.; Qiu, H.; Wu, W.; Loy, C.C.; Liu, Z. Text2human: Text-driven controllable human image generation. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2022, 41, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Lin, J.; Dwivedi, S.K.; Sun, Y.; Patel, P.; Black, M.J. Chatpose: Chatting about 3d human pose. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 2093–2103. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Noah, S.A.M.; Sarim, H.M. A survey on deep neural networks in collaborative filtering recommendation systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.01378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Ying, R.; Caverlee, J. Flow Matching for Collaborative Filtering. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V. 2, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2025; pp. 1765–1775. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, Y.; Bell, R.; Volinsky, C. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer 2009, 42, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liao, L.; Zhang, H.; Nie, L.; Hu, X.; Chua, T.S. Neural collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; He, Z.; Song, J.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.G.; Chua, T.S. NAIS: Neural attentive item similarity model for recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2018, 30, 2354–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, M. What is YOLOv9: An in-depth exploration of the internal features of the next-generation object detector. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.07813. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, D.; Kupec, J.; Hong, J.; Daoudi, A. Real-time flying object detection with YOLOv8. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.09972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Akata, Z.; Yan, X.; Logeswaran, L.; Schiele, B.; Lee, H. Generative adversarial text to image synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; pp. 1060–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2223–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Zhang, R.; Pathak, D.; Darrell, T.; Efros, A.A.; Wang, O.; Shechtman, E. Toward multimodal image-to-image translation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, W.L.; Grauman, K. Creating capsule wardrobes from fashion images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7161–7170. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Li, N.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Piao, J.; Quan, Y.; Chang, J.; Jin, D.; He, X.; et al. A survey of graph neural networks for recommender systems: Challenges, methods, and directions. ACM Trans. Recomm. Syst. 2023, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, W.; Lian, J.; Xie, X. Graph convolution machine for context-aware recommender system. Front. Comput. Sci. 2022, 16, 166614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Ren, P.; Chen, Z.; Nie, L.; Ma, J.; Nie, J.Y. An attentive interaction network for context-aware recommendations. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Turin, Italy, 22–26 October 2018; pp. 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, X.; Chen, B.; He, X.; Wang, D.; Ding, Y.; Jose, J.M. CFM: Convolutional factorization machines for context-aware recommendation. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; Volume 19, pp. 3926–3932. [Google Scholar]

- Rashed, A.; Elsayed, S.; Schmidt-Thieme, L. Context and attribute-aware sequential recommendation via cross-attention. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–23 September 2022; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Feng, S.; Li, Z. Weather-to-garment: Weather-oriented clothing recommendation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Hong Kong, China, 10–14 July 2017; pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Qin, Z.; Zha, H. Personalized fashion recommendation with visual explanations based on multimodal attention network: Towards visually explainable recommendation. In Proceedings of the 42nd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Paris, France, 21–25 July 2019; pp. 765–774. [Google Scholar]

- Celikik, M.; Wasilewski, J.; Mbarek, S.; Celayes, P.; Gagliardi, P.; Pham, D.; Karessli, N.; Ramallo, A.P. Reusable self-attention-based recommender system for fashion. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Recommender Systems in Fashion and Retail, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–23 September 2022; pp. 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Xu, B. Aspect-based fashion recommendation with attention mechanism. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 141814–141823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Y.; Ali, N.; Flah, A.; Kanan, M.; Alsharef, M.; Ghoneim, S.S. A deep transfer learning based convolution neural network framework for air temperature classification using human clothing images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 2019, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X. Explainable recommendation: A survey and new perspectives. Found. Trends® Inf. Retr. 2020, 14, 1–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Year | Images | Category | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepFashion [32] | 2016 | 800 k+ | Multi-Category | Large-scale dataset fashion with rich annotations |

| Inshop [32] | 2016 | 52 k | Clothes | Consumer-to-shop retrieval benchmark |

| Fashion-MNIST [33] | 2017 | 70 k | Clothes | Grayscale clothing item images |

| Fashion-Gen [35] | 2018 | 293 k | Clothes | Fashion images with text descriptions |

| ModaNet [37] | 2018 | 55 k | Clothes | Street fashion with polygon annotations |

| CLOTH3D [34] | 2020 | 100 k | 3D Clothes | 3D garment meshes with simulation data |

| Fashionpedia [36] | 2020 | 48 k | Clothes | Fine-grained fashion attribute dataset |

| VITON-HD [3] | 2021 | 13 k | Clothes | High-resolution virtual try-on dataset |

| DressCode [41] | 2022 | 53 k | Multi-Category | Multi-category virtual try-on |

| 4D-DRESS [42] | 2024 | 78 k | 4D Real Clothing | Real-world 4D textured scans |

| Method | Task | Dataset | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. [59] | Makeup transfer | MIT (>100 images) | Visual Quality |

| CNN Ensemble [60] | Face beauty prediction | SCUT-FBP5500 | 91.2% (MAE) |

| Stable-Makeup [61] | Diffusion transfer | Real-world makeup | Transfer Quality |

| SHMT [62] | Self-supervised transfer | Hierarchical decomposition | Superior Fidelity |

| Model | AdvFaces [66] | GFLM [68] | PGD [69] | FGSM [70] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FaceNet [71] | 99.67 | 23.34 | 99.70 | 99.96 |

| SphereFace [72] | 97.22 | 29.49 | 99.34 | 98.71 |

| ArcFace [73] | 64.53 | 03.43 | 33.25 | 35.30 |

| COTS-A | 82.98 | 08.89 | 18.74 | 32.48 |

| COTS-B | 60.71 | 05.05 | 01.49 | 18.75 |

| Structural Similarity | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.12 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.25 ± 0.06 |

| Computation Time (s) | 0.01 | 3.22 | 11.74 | 0.03 |

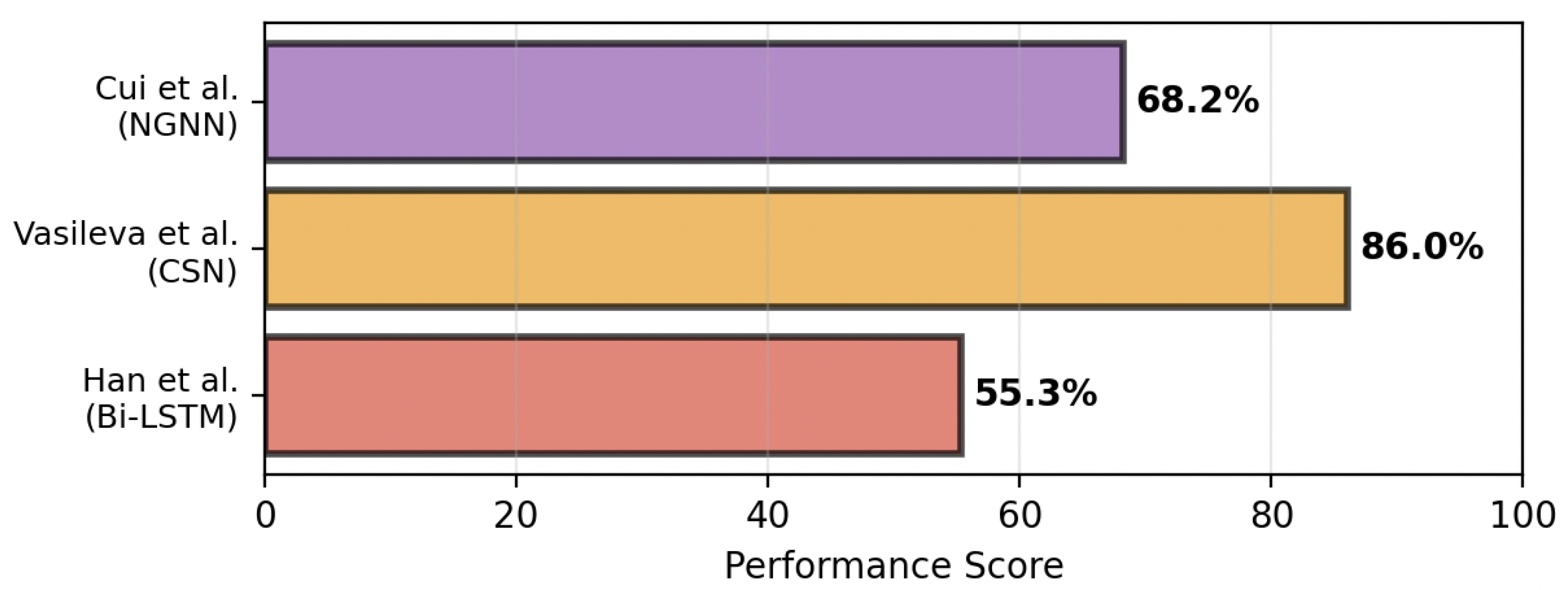

| Method | Model | Approach | Unique Aspects |

|---|---|---|---|

| SeqGAN [75] | Bi-LSTM | Sequential | Visual-semantic embedding |

| StyleNet [79] | Bi-LSTM + AE | Sequential + Style | Style extraction via autoencoder |

| TypeAware [76] | CSN | Type-aware | Category-specific embeddings |

| NGNN [78] | NGNN | Graph-based | Node-wise graph networks |

| Paper | Year | Evaluation Metrics | Dataset | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [82] | 2019 | Human evaluation | Web photos | Minimal outfit edits |

| [86] | 2019 | Visual quality | Polyvore | Attribute-based generation |

| [84] | 2020 | Inception Score | Fashion dataset | Multi-domain translation |

| [83] | 2021 | SSIM, LPIPS | Polyvore | Compatibility-regularized GAN |

| Paper | Year | Model | Control Mechanism | Control Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [87] | 2019 | FineGAN | Hierarchical disentanglement | Localized |

| [88] | 2019 | Multimodal embedding | Text-image coherence | Theme-based |

| [89] | 2023 | FashionTex | Text and texture | Attribute-based |

| [90] | 2024 | DCGS | 3D Gaussian splatting | Full garment |

| Method/Dataset | Task | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| DeepFashion [32] | Clothes recognition | Rich annotations |

| VITON [2] | Virtual try-on | Person representation |

| CP-VTON [43] | Characteristic-preserving | Geometric matching |

| ClothFlow [106] | Flow-based try-on | Appearance flow |

| Method | Year | Input | Architecture | Key Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAGAN [27] | 2017 | Cloth. + Person Images | Conditional GAN | Fashion article swapping |

| VITON [2] | 2018 | Cloth. + Parsing Maps | Coarse-to-fine | Clothing-agnostic representation |

| CP-VTON [43] | 2018 | Cloth. + Person Images | GMM + TOM | Characteristic preservation |

| ClothFlow [106] | 2019 | Cloth. + Person Images | Flow-based | Appearance flow estimation |

| ACGPN [40] | 2020 | Cloth. + Semantic Layout | Attention + GAN | Semantic-guided generation |

| VITON-GAN [109] | 2019 | Cloth. + Person Images | Adversarial Training | Occlusion handling |

| Method | Year | Input | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| FW-GAN [121] | 2019 | Video | Flow-Guided Warping + GAN |

| VIBE [120] | 2020 | Video | Temporal Motion Discriminator + 3D Estimation |

| ClothFormer [119] | 2022 | Video | Appearance-Flow Tracking + Vision Transformer |

| WildVidFit [113] | 2024 | Video | Diffusion Guidance + VideoMAE Consistency |

| DPIDM [114] | 2025 | Video | Dynamic Pose Interaction + Diffusion Models |

| RealVVT [116] | 2025 | Video | Spatio-Temporal Attention + Foundation Models |

| Method | Accessory Detection | Pose Estimation | SSIM ↑ | MSE ↓ | LPIPS ↓ | FID ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VITON [2] | 78% | 83% | 0.65 | 0.021 | 0.21 | 45.2 |

| CP-VTON [43] | 86% | 89% | 0.69 | 0.017 | 0.18 | 39.1 |

| SP-VITON [125] | 80% | 85% | 0.72 | 0.015 | 0.15 | 32.5 |

| MG-VTON [126] | 82% | 87% | 0.75 | 0.012 | 0.12 | 28.1 |

| SwiftTry [115] | 88% | 91% | 0.78 | 0.009 | 0.10 | 24.9 |

| Method | Performance (FPS) | Mesh Resolution | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass-Spring [146] | 60+ | 50 × 50 vertices | Mobile VR |

| Unity Cloth [147] | 45–60 | 32 × 32 vertices | Meta Quest 3 |

| GPU-PBD [147] | 60+ | 64 × 64 vertices | Meta Quest 3 |

| Parallel GPU [154] | 60+ | 7K triangles | Desktop VR |

| Dataset | Year | Size | Task | Accuracy/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street2Shop [167] | 2015 | 404k shop, 20k street | Retrieval | MAP > 70% |

| DeepFashion [32] | 2016 | 800k images | Classification | 85% Top-1 |

| Fashion-Gen [35] | 2018 | 293k images | Generation | FID scores |

| ModaNet [37] | 2018 | 55k images | Segmentation | mIoU varies by class |

| DeepFashion2 [168] | 2019 | 491k images | Multi-task | Detection mAP > 60% |

| DeepFashion-MultiModal [169] | 2022 | 44k images | Multi-modal | Various tasks |

| Method | Year | Dataset | Key Features | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepFashion [32] | 2016 | DeepFashion | CNN-based recognition | Various tasks |

| NCF [176] | 2017 | MovieLens | Neural collaborative filtering | HR@10: 0.409 |

| Fashion Compatibility [75] | 2017 | Polyvore | Bidirectional LSTM | AUC: 0.9 |

| NAIS [177] | 2018 | Amazon | Attentive item similarity | HR@10: 0.686 |

| FashionNet [6] | 2018 | Polyvore | CNN + MLP | Compatibility scores |

| POG [163] | 2019 | Alibaba | Personalized outfit generation | Industrial deployment |

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Faster R-CNN [171] | Two-stage detector using Region Proposal Network and bounding box/class prediction. |

| Mask R-CNN [172] | Extends Faster R-CNN with mask prediction branch for instance segmentation. |

| YOLO [178] | Single-shot detector predicts boxes and classes per grid cell. |

| YOLOv3 [179] | Improved YOLO with Darknet-53 backbone and multi-scale predictions. |

| YOLOv8 [180] | Improved architecture, anchor-free design, and enhanced training strategies. |

| YOLOv9 [181] | Introduces PGI and GELAN architectures. |

| YOLOv11 [182] | Improved accuracy-speed tradeoff and advanced feature extraction capabilities. |

| Method | Dataset | Key Evaluation Metric |

|---|---|---|

| WoG [193] | Clothing with weather data | Weather suitability |

| Multimodal Attention [194] | Fashion images with reviews | Visual explanation accuracy |

| AFRA [195] | Multi-entity fashion data | Recommendation precision |

| AFRAM [196] | E-commerce reviews/ratings | Rating prediction accuracy |

| Method | Year | Task | Code Repository | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Fashion | ||||

| VITON [2] | 2018 | Virtual Try-On | https://github.com/xthan/VITON (accessed on 10 December 2025) | ✓ |

| CP-VTON [43] | 2018 | Characteristic-Preserving | https://github.com/sergeywong/cp-vton (accessed on 10 December 2025) | ✓ |

| ACGPN [40] | 2020 | Pose-Guided Try-On | https://github.com/switchablenorms/DeepFashion_Try_On (accessed on 10 December 2025) | ✓ |

| VITON-HD [3] | 2021 | High-Resolution Try-On | https://github.com/shadow2496/VITON-HD (accessed on 10 December 2025) | ✓ |

| TryOnGAN [47] | 2021 | Layered Interpolation | https://github.com/ofnote/TryOnGAN (accessed on 10 December 2025) | ✓ |

| StyleGAN-Human [49] | 2022 | Human Generation | https://github.com/stylegan-human/StyleGAN-Human (accessed on 10 December 2025) | ✓ |

| Simulative Fashion | ||||

| VIBE [120] | 2020 | 3D Motion Estimation | https://github.com/mkocabas/VIBE (accessed on 10 December 2025) | ✓ |

| ClothFormer [119] | 2022 | Video Try-On | Code available on request | × |

| Neural Cloth Sim [129] | 2022 | Physics Simulation | https://github.com/hbertiche/NeuralClothSim (accessed on 10 December 2025) | ✓ |

| DrapeNet [127] | 2023 | Garment Draping | https://github.com/liren2515/DrapeNet (accessed on 10 December 2025) | ✓ |

| VIVID [112] | 2024 | Video Virtual Try-On | https://github.com/sharkdp/vivid (accessed on 10 December 2025) | × |

| VITON-DiT [118] | 2024 | Diffusion Transformers | https://github.com/ZhengJun-AI/viton-dit-page (accessed on 10 December 2025) | × |

| SwiftTry [115] | 2025 | Fast Video Try-On | https://github.com/VinAIResearch/SwiftTry (accessed on 10 December 2025) | × |

| RealVVT [116] | 2025 | Photorealistic Video | Code available on request | × |

| DPIDM [114] | 2025 | Dynamic Pose Interaction | Code available on request | × |

| Recommender Fashion | ||||

| Fashion Compatibility [75] | 2017 | BiLSTM Sequential | https://github.com/xthan/polyvore (accessed on 10 December 2025) | × |

| NGNN [78] | 2019 | Graph-Based Outfit | https://github.com/CRIPAC-DIG/NGNN (accessed on 10 December 2025) | × |

| POG [163] | 2019 | Outfit Generation | Proprietary (Alibaba iFashion) | × |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kachbal, I.; El Abdellaoui, S. Computer Vision for Fashion: A Systematic Review of Design Generation, Simulation, and Personalized Recommendations. Information 2026, 17, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010011

Kachbal I, El Abdellaoui S. Computer Vision for Fashion: A Systematic Review of Design Generation, Simulation, and Personalized Recommendations. Information. 2026; 17(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleKachbal, Ilham, and Said El Abdellaoui. 2026. "Computer Vision for Fashion: A Systematic Review of Design Generation, Simulation, and Personalized Recommendations" Information 17, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010011

APA StyleKachbal, I., & El Abdellaoui, S. (2026). Computer Vision for Fashion: A Systematic Review of Design Generation, Simulation, and Personalized Recommendations. Information, 17(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010011