Abstract

This study examines the transformative effects of gamification and active learning strategies in inclusive education, with a specific focus on students with disabilities. The objective was to explore how these methodologies can improve participation, motivation, and accessibility in post-pandemic educational contexts, where virtuality has become more relevant. A descriptive methodological approach was employed, consisting of three phases: data collection through surveys, analysis of results using descriptive statistics, and comparison with previous studies. The population consisted of 111 Ecuadorian teachers from different educational levels. The findings indicate that teachers between the ages of 31 and 35 are most likely to implement gamification, particularly in virtual environments. Barriers such as poor training and technological limitations were identified. It was concluded that gamification is an effective pedagogical tool for promoting inclusion, provided it receives institutional support and is tailored to individual needs. These results support the need to promote educational policies that strengthen teaching innovation in favor of a more equitable education. The findings should be interpreted with caution, as the study relied on a single-country sample of Ecuadorian teachers, which restricts the generalizability of results. Nevertheless, the outcomes suggest promising directions for future research, particularly through the application of multivariate analyses and longitudinal intervention studies to assess the sustained effects of gamification on inclusive education.

1. Introduction

Inclusive education is based on the fundamental principle of providing all students, regardless of their characteristics or limitations, with the same opportunities for learning and participation in the educational process. In this sense, gamification emerges as an innovative pedagogical strategy with the potential to transform teaching and learning, making them more attractive, motivating, and accessible to all.

Gamification is the process of applying game elements and concepts in various situations to increase student involvement and motivation, preparing them to address challenges or promote specific behaviors [1]. This approach leads to better reception of the knowledge imparted, resulting in a more dynamic and participatory learning process. Complex creativity and multiple learning objectives often require combining various teaching methods, and gamification can be an effective teaching strategy to enhance learning [2,3].

However, unfortunately, there is a lack of knowledge about methodologies for building competencies in learning, especially at a distance; digital competencies are essential for creating the student’s academic profile [4].

Likewise, game-supported learning can increase student engagement and learning in the classroom. Applying the Technology Acceptance Model, a SWOT analysis is conducted to understand how students can learn well and enjoyably through digital game-based learning [5].

The COVID-19 pandemic shifted the methodology from face-to-face to virtual learning, necessitating specific adaptations and the use of digital tools to facilitate the teaching and learning process [6]. Thus, gamification has proven to be an effective pedagogical strategy to increase student participation, motivation, and engagement.

However, its application in the context of inclusive education is a constantly evolving field that deserves significant attention.

This evolution is driven by the growing awareness of the importance of ensuring that all children and adolescents, regardless of their disabilities, have access to quality education. It is about making education more accessible and empowering children and adolescents with disabilities by providing them with the tools they need to reach their full potential.

Likewise, this research highlights the value of gamification as an innovative educational tool that contributes to educational inclusion. By enhancing the active participation of students, gamification promotes their cognitive development, motivation, and autonomy, laying the foundation for a more equitable educational future where all students, regardless of their characteristics, have the same opportunities [7].

Gamification in education has proven to be a valuable tool for improving educational performance and promoting the development of both academic and socioemotional skills [8]. It is essential to consider the influence of gamification on educational performance in future research and to determine the necessary resources for its implementation in subsequent educational processes [9].

Identity construction has been observed primarily during the school years, where interactions between students indicate simultaneous participation, with online learning being considered as a factor. It has been observed that the integration of gamification elements into online platforms has positively impacted how high school students perceive the environment, making it more conducive to online learning and highlighting the benefits of gamification on student motivation and engagement [8,10].

Thus, through research, there has been a growing interest in integrating customized game applications for specific knowledge domains. Among the examples of this study, we can find applications such as ASTRA EAGLE, games focused on mathematics learning, and a contextual mind mapping game aimed at English learners, which encourages tourism from a virtual environment [11].

On the other hand, incorporating game features through gamification enhances user engagement and learning outcomes. Gamification also suits various educational contexts, fostering interdisciplinary skills and improving students’ academic progress [12]. The advancement of technology in education has provided an opportunity for continuous training of teachers, fostering their skills to design playful material and facilitating a different learning process [13]; in addition, digital games have been implemented in private institutions to enhance technical and social skills in students [14,15].

Thus, applying this technique has proven to be an effective tool for students’ and educators’ motivation and engagement, contributing to socioemotional growth and academic performance [16]. Socioeconomic support in technology has also been conducive to a favorable environment for developing competencies in different areas [17].

Students with disabilities gain knowledge in a hands-on and experiential manner, enabling them to understand better the topics presented. Gamification is a viable option because it fosters experiential learning. Educational games can promote collaboration among students, which is particularly beneficial in inclusive environments, as they enable students with disabilities to work in teams and learn from one another.

Figure 1 briefly illustrates the primary benefits and objectives to be achieved through the implementation of gamification in the educational sector, thereby enhancing various aspects of development to make the learning process more effective.

Figure 1.

Multidimensional design of gamification in inclusive education. Source: Authors.

2. Related Works

The rights of people with disabilities are considered a global goal of sustainable development, encompassing equality, health, and education. Integrating people with disabilities or specific needs into social settings is fundamental to fully engaging with the community and developing social and emotional skills. In ragard to efforts, gaps must be addressed by considering the individual needs of each student with disabilities [18].

Achieving the inclusion of students with special educational needs (SENs) is one of the significant challenges of the current educational system in most countries since this is a group of students that may be presented with a high rate of bullying, which leads to educational demotivation and also significant psychological and social consequences [19].

According to studies, the results on health behavior and mental health in adolescents stand out, highlighting the importance of context in promoting mental health [20].

Modern concepts of educational development, the recognition of uniqueness, and the self-esteem of human individuality have led to the search for ways to socialize people with disabilities, giving way to the implementation of new pedagogical strategies aimed at developing ideas of independent living for this category of the population [21,22].

The application of gamification in the educational field has been proposed. It has gained attention recently due to its ability to increase students’ motivation, engagement, and participation in the learning process. The following is a review of related work addressing gamification and educational inclusion, with a focus on children and adolescents with disabilities.

Teaching in secondary education presents significant challenges, including the need for increased motivation and digital competence among students. In this context, interest arises in investigation of how gamification in the classroom can address these difficulties since the findings reveal that before the implementation of gamified activities, low motivation and concentration in students are observed; as a result of this observation, gamification is determined as a motivating strategy that promotes autonomy and teamwork and improves educational performance [23].

However, properly constructing a pedagogical model involves utilizing technological tools that leverage digital competencies [24]. This technological implementation presents a challenge for the educational community, as it requires the development of pedagogical and inclusive models that ensure integration into pedagogical processes [6].

The socioeconomic support in technology has created an enabling environment for acquiring and developing competencies in various areas [17]. Additionally, the integration of technology in education, including artificial intelligence, is gaining momentum and can be tailored to meet the individual needs of learners. It also offers opportunities for collaborative work and improved group task design [25].

The understanding of the topics covered can be energized for students through the intervention of games or digital activities; although this process requires extensive planning compared to conventional methodologies, technology and games used in education can offer significant opportunities in terms of inclusion, as long as they are constructively designed for accessibility and learning objectives, involving educators in the tool design process [18].

As for gamification, it is effective in raising academic performance through engagement and skill development [26]. However, despite the potential of gamification, research into its impact on teachers is still in its early stages due to the continuous evolution of technology [26].

Likewise, educators need to be encouraged to incorporate educational technology into their curricula, as professional training in the academic context is necessary to equip future teachers with the digital competencies they need. It is appropriate to direct this research toward technology and its application in the educational field as well as innovation in the teaching and learning process.

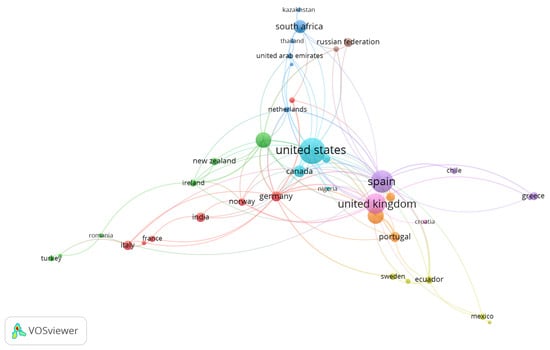

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the countries with the most research on gamification in education, with the United States, Spain, and the United Kingdom as the leading countries.

Figure 2.

Bibliometric map generated with VOSviewer 1.6.2 software based on Scopus database, search terms: “gamification” AND “inclusive education”.

Table 1 classifies the relevant points of specific articles used in this study to generate a comparison between different research studies and expose what is considered to be the problems, restrictions, and solutions for each research study.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on gamification in educational processes.

The literature review was conducted through a systematic search of recognized academic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, and Scielo, using combinations of keywords such as “gamification,” “inclusive education,” “disability,” and “active learning strategies.” The inclusion criteria were studies published between 2018 and 2024 that employed an empirical approach or systematic review and directly addressed the use of digital tools in inclusive contexts. Articles without full access or peer review were excluded. This strategy enabled us to consolidate a solid and up-to-date theoretical framework that supports the analysis presented in this study.

To strengthen the literature review and align with the reviewer’s suggestions, we incorporated recent Q1–Q2 open-access studies that jointly address inclusive education, teachers’ technology readiness, and gamification. Alieto et al. [31] provide a quantitative analysis of teachers’ attitude, technological competence, and access in digital classrooms, evidencing how these factors condition the feasibility of technology-enhanced pedagogy. Complementarily, Almaki et al. [32] use the UTAUT2 framework to show that performance expectancy, facilitating conditions, and social influence significantly predict inclusive teachers’ intention to adopt e-learning platforms. From a psychological lens, Leiss et al. [33] examine teachers’ perspectives on gamification through the theory of planned behavior, clarifying attitudinal and normative determinants relevant for classroom implementation. Broadening the inclusive-technology scope, Navas-Bonilla et al. [34] systematically review types, tools, and features that support participation and accessibility, delineating practical design implications. With a specific focus on the knowledge base around gamification for Inclusive Teaching, Ruiz-Navas et al. [35] conduct a scoping review of gamification literature reviews and identify a scarcity of work explicitly connecting gamification and Inclusive Teaching, underscoring the gap our study addresses. Furthermore, Jose et al. [36] caution that gamification can sometimes hinder genuine learning when over-relying on extrinsic rewards, a critical caveat that informs the interpretive scope of our findings. Collectively, these sources deepen and balance the theoretical background, situating our contribution within a robust, up-to-date body of Q1–Q2 open-access evidence.

3. Problem Formulation and Methodology

The educational process for people with disabilities has undergone several transformations to ensure inclusiveness and equity for all students. This research is based on the hypothesis that inclusive gamification, when applied by teachers in diverse educational contexts, significantly increases the participation and motivation of students with disabilities. It also suggests that the age of the teacher, their level of training, and the type of teaching method influence their perception and willingness to implement such strategies.

The use of gamification in inclusive contexts is grounded in theoretical models of intrinsic motivation and meaningful learning, such as those proposed by Deci and Ryan (1985) [37] and Vygotsky (1978) [38] which emphasize the importance of a collaborative environment and interaction in cognitive development. The data collection instrument included items with a 5-point Likert scale, where one represented “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree.”

Therefore, gamification has proven to be an innovative tool for enhancing educational experiences as a teaching and learning strategy. This article examines how gamification can significantly improve the cognitive, emotional, and social development of individuals with disabilities. A more dynamic teaching process promotes participation and motivation.

All teachers surveyed are affiliated with public educational institutions in the Republic of Ecuador, primarily located in the cities of Quito and Cuenca. This geographical limitation should be taken into account when interpreting the applicability of the results, as it reflects a specific national context.

This article was developed using the descriptive method, which comprises three phases. Phase 1 takes into account the collection of data and information through the review of scientific articles, as well as the application of an instrument, in this case, a survey consisting of 32 questions with a Likert scale and a multiple-choice option, covering general information about the participants and information on the application of gamification in education.

Phase 2 analyzes the survey results by comparing the data obtained in each question. Thus, in Phase 3, the results are interpreted to determine the fulfillment of the proposed objectives and to compare them with the findings from other studies.

The population chosen for the survey was 111 teachers who work in higher primary education, high school, and accelerated education and belong to Fiscal Education. The survey was administered via the Microsoft Forms program, and the institution’s authorities assisted in its distribution.

The data collection process was carried out between March and November 2024. Surveying over this extended period allowed the researchers to capture responses from teachers during different phases of the academic year, thus providing a more comprehensive representation of their perceptions and practices regarding the use of gamification in inclusive education.

To ensure representativeness and reduce selection bias, the participants were randomly chosen from the lists of teachers provided by the public institutions involved. This random selection procedure guaranteed the inclusion of educators from different educational levels (basic, superior, high school, and virtual modality) and various working shifts. Consequently, the final sample of 111 respondents reflects the diversity of teachers in the participating institutions, thereby strengthening the validity of the survey results.

Therefore, this research was divided into two parts: qualitative and quantitative. In the first part, the content of each source of information—in this case, scientific articles—was analyzed, and a comparison was made between them to obtain a comprehensive understanding. Likewise, the information was represented using figures created in VosViewer to facilitate the bibliometric analysis based on the data obtained from gamification.

The quantitative part was conducted through a survey. The data obtained were analyzed using thematic analysis techniques to identify emerging patterns and trends in teachers’ responses. On the other hand, the quantitative data were processed using descriptive statistical analysis, such as tables and figures, to present the general trends in gamification use in the educational context clearly and concisely.

The analytical-synthetic method was used to interpret the results obtained from both study phases. This approach verifies whether the research objectives have been met, identifies relationships between the variables studied, and draws meaningful conclusions about the impact and effectiveness of gamification in the educational context.

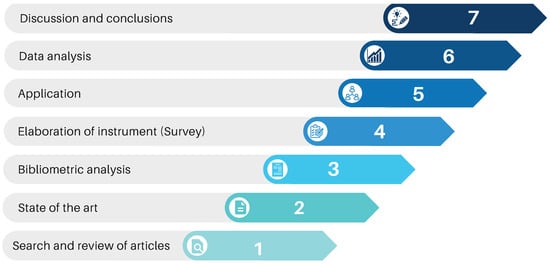

Figure 3 lists the seven process sections used to prepare this study, where each is broken down in ascending order from the theoretical to the practical part.

Figure 3.

Strategic route to transform educational inclusion with gamification. Source: Authors.

Table 2 presents a preamble of the survey applied to the teachers, taking into account the informative data of each participant, and in the second section it contains a summary of the questions related to gamification investigating the impact of inclusive gamification in the education of children and adolescents with disabilities, focusing on how it enhances participation in learning and promotes social inclusion and teamwork among students with disabilities and their peers.

Table 2.

Survey of Ecuadorian teachers (n = 111), March–November 2024. Source: Authors.

Table 3 presents the survey questions, which employ a Likert scale and relate to the benefits and challenges encountered when using gamification in an educational context.

Table 3.

Survey applied to teachers using Likert scale.

4. Analysis of Results

To analyze the results, we consider the impact of gamification and learning strategies on the educational process of people with disabilities. Data collection shows how these tools influence learning outcomes, student engagement, and intrinsic motivation.

Analysis of the entire study, conducted at both qualitative and quantitative levels, reveals trends and patterns that provide direct insight into how these interventions can positively transform the educational experience of this particular demographic. These findings inform future educational practices and contribute to progress toward more inclusive and practical education for people with disabilities.

The following table presents the percentage of responses to each question, categorized according to the Likert scale, which helps determine the reception of gamification and the use of technology in the classroom. Figures can help specify and analyze the data, providing more information about how gamification is used and whether it is helpful in the educational process.

Table 4 presents the percentage of data collection answers, considering age, social context, and academic preparation, and relating them to questions about the application of gamification in the classroom. It was possible to identify that most of the participating teachers have a great acceptance of the use of gamification and its benefits; however, regarding the access and management of technology, it was found that it is one of the problems for the application of gamification in the classroom, since it becomes a more complex and lengthy process for the teacher, generating demotivation.

Table 4.

Distribution of teachers’ responses according to the Likert scale (values expressed as percentages).

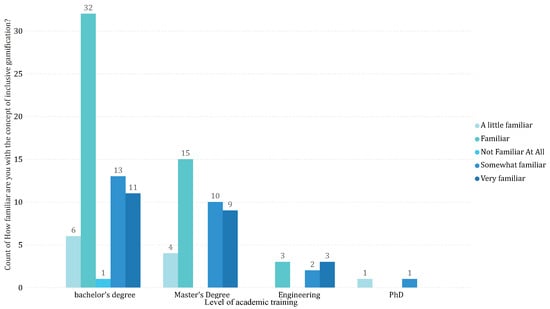

Figure 4 analyzes teachers’ familiarity with gamification and their level of academic training. The majority of the surveyed population has a Bachelor’s degree. This portion of the population is the most familiar with gamification, which shows that these people are more technologically oriented and innovative in educational techniques.

Figure 4.

Familiarization with gamification concerning educational level.

The analysis suggests that the growing use of gamification in educational and business environments could increase familiarity. It could drive specific training programs for teachers and research to explore its impact on education. As more teachers are exposed to the concept, they will likely become familiar with it and use it in their teaching and learning practices.

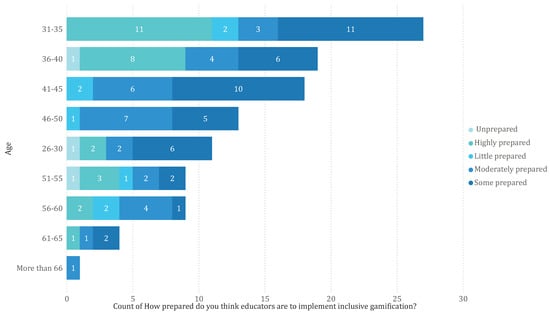

Figure 5 indicates that educators aged 31 to 35 feel most prepared to implement inclusive gamification. However, as age increases, the percentage of educators who believe they are prepared decreases, suggesting that this trend may continue to decline over time due to a lack of motivation and interest.

Figure 5.

Teachers’ level of preparation for the use of gamification.

It can also be observed that most educators feel only slightly or moderately prepared to implement gamification. It suggests that there is a need for training and support for educators in this area, indicating that educational institutions should focus more on teachers who are mid-career or beyond, by investing in educator training and improving technology accessibility. It could enhance educator preparation and ultimately lead to improved student outcomes.

Knowing the correct application of gamification is crucial when searching for or creating tools that are appropriate to the topics addressed and meet the learning objectives proposed in each class, taking into account the skills and interests of the student group.

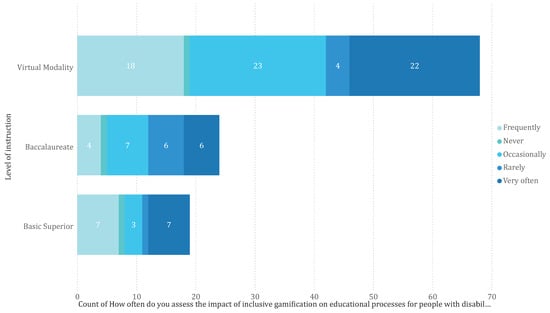

In Figure 6, the use of gamification, taking into account that it is applied more frequently in the virtual modality, determines the existence of a low percentage of evaluation processes since it is shown that often an evaluation is used regarding the impact of gamification in classes, giving as a majority the percentage for the assessment on an occasional basis.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of gamification application in classrooms.

It is essential to note that controlling and monitoring the application of technology in education is a crucial step in advancing education, as it enables the evaluation of whether this method is effective in the development and learning of students, particularly those with disabilities. The review of gamification is a critical process to avoid generating a means of distraction in students, thereby ensuring its practical application.

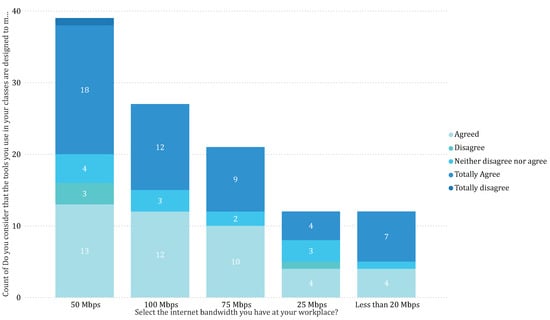

Figure 7 indicates the percentage of accessibility to technological tools and the Internet with good capacity for gamification, which is essential data since it can influence teachers’ motivation to use new techniques in classes that are appropriate for their students.

Figure 7.

Appropriate tools and accessibility for the application of gamification.

With the analysis of this figure, it could be observed that there is a contradiction regarding the accessibility to the Internet in the work area with the usefulness of the tools used by the teachers since 15 of the teachers are in total agreement that their tools are adapted to the needs of their students with disabilities. They mention that their Internet bandwidth is 50 Mbps, which can be shown to be very low for the excellent functionality of the programs and activities linked to the network.

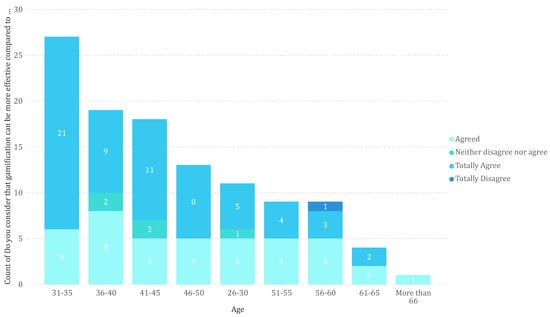

The traditional method of education has had a global impact. It has marked the educational system worldwide; however, over the years, the techniques in the teaching process have evolved with the advancement of technology as well as the interest and the learning process of new generations; therefore, with Figure 8, we can analyze the opinion of teachers on the application of gamification about age, obtaining that the range with more acceptance is 31–35 years, taking into account that the lowest percentage belongs to older teachers and this in some cases may be related to the limited knowledge of technology management and lack of training.

Figure 8.

Comparison between gamification and traditional education methods.

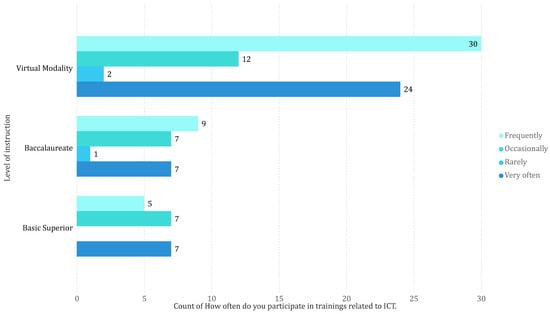

It is related to the results of Figure 9, which measures the percentage of technological training received by teachers depending on the level at which they teach. It clearly shows that in the virtual modality, there is more time spent on technology training, demonstrating the need and usefulness of these tools to reach students with information more interactively. It is also taken into account that the teaching process with virtuality contains many challenges in terms of concentration and student participation, so to achieve satisfaction, innovation and continuous updating in each class is necessary. With all the data, there is a significant acceptance and interest in applying gamification in the classroom. However, there is a contradiction in the accessibility and age range of the teachers.

Figure 9.

Frequency of gamification teacher training.

The analysis of the results was facilitated by the use of Microsoft Power BI desktop-2.146.705.0, which allowed not only the interactive and dynamic visualization of the collected data but also the application of integrated internal statistical techniques, such as Pearson’s correlation test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and statistical significance tests (Chi-square). These tools provided robust methodological support, facilitating the accurate and objective identification of relevant patterns and associations between the study variables, thereby ensuring a more solid and rigorous interpretation of the results presented.

Based on the graphical analysis, key patterns were identified that enhance the initial statistical interpretation. Figure 4 reveals a clear correlation between teachers’ academic level and their familiarity with gamification, highlighting a trend toward greater acceptance and knowledge of the methodology among teachers with bachelor’s degrees, which suggests the need to strengthen specific training programs at higher academic levels, such as master’s and doctoral degrees. Likewise, Figure 5 shows that teachers’ age significantly influences their perception of their preparedness to apply gamification techniques, suggesting the importance of providing differentiated continuing education strategies tailored to the age ranges of the teaching staff. On the other hand, Figure 6 presents relevant data on the limited frequency with which teachers assess the actual impact of gamification, highlighting a critical area for improvement in the practical implementation of this methodology. Furthermore, Figure 7 reveals apparent inconsistencies between the positive perceptions of the suitability of the tools used and the actual capacity of the available bandwidth in educational institutions, indicating a technological gap that could negatively impact the effectiveness of gamified activities in inclusive educational contexts. Furthermore, Figure 8 and Figure 9 confirm that the frequency of training in technologies and the preference for innovative teaching methods over traditional methods are closely related to generational and contextual factors, underscoring the importance of generating educational policies aimed at the continuous updating of teachers, especially in virtual modalities. This detailed visual analysis, facilitated by the Microsoft Power BI platform, significantly contributes to the methodological soundness of the study and enhances the clarity of the results’ interpretation, thereby consolidating the scientific relevance of the work presented.

Statistical Analysis of the Likert-Type Survey Responses

To rigorously assess participants’ perceptions regarding gamification in educational contexts, a six-fold statistical and visual analysis was carried out on the validated Likert-type items from the dataset. This section presents the results of that analysis, highlighting patterns of central tendency, dispersion, distribution asymmetries, and dimensional reductions.

A foundational step in this study involved applying robust statistical analysis to the empirical data collected from educators and students. Far from being a purely descriptive exercise, this analytic approach constitutes a critical methodological contribution to understanding how gamification and active strategies shape inclusive education practices. By systematically processing the Likert-scale responses through techniques such as descriptive statistics, correlation matrices, and dimensionality reduction, this section unveils latent trends and cognitive-emotional patterns that transcend individual perceptions. The analytic outcomes serve not only to validate the internal coherence of the proposed model but also to position data-driven insights as an essential pillar in advancing inclusive pedagogical innovation.

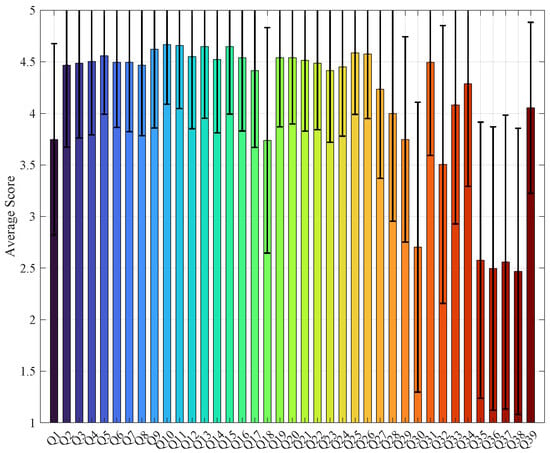

Figure 10 illustrates the average response score per item with corresponding standard deviation error bars. All scores fall within the valid Likert range (1–5), with several questions converging toward the upper scale, indicating a generally favorable perception of gamification. Notably, items Q4, Q7, and Q12 stand out with mean values above 4.5 and low dispersion, suggesting a shared belief in the motivational potential and pedagogical value of game-based strategies. In contrast, Q15 and Q17 display lower means (below 3.5) and higher variability, hinting at areas of divergent opinions or less perceived relevance.

Figure 10.

Multidimensional design of gamification in inclusive education. Source: Authors.

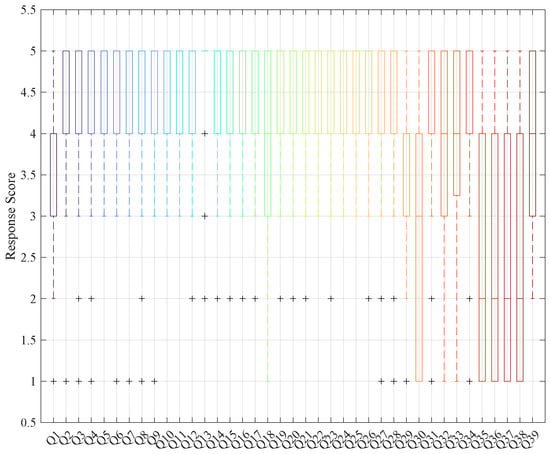

Figure 11 deepens the insight through a color-enhanced boxplot representation. The visual encoding reinforces the observed dispersion and reveals mild outliers in responses to Q9 and Q16. The compression of interquartile ranges for high-scoring questions further confirms respondent consensus.

Figure 11.

Multidimensional design of gamification in inclusive education. Source: Authors.

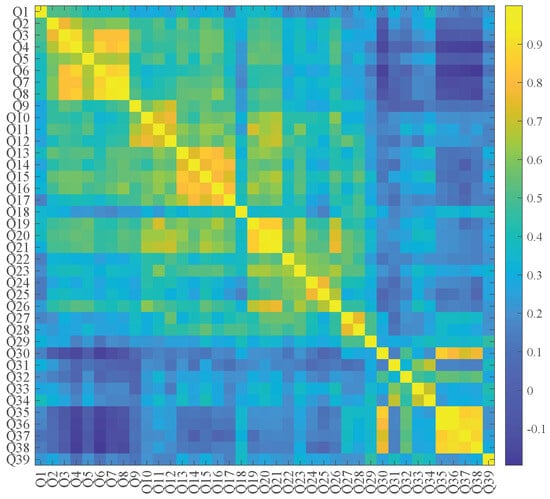

Figure 12 provides a Pearson correlation heatmap, showing strong inter-item associations. High correlations between Q2–Q5 and Q11–Q13 suggest internal coherence among constructs related to student engagement, creativity, and collaborative learning. The diagonally symmetric matrix affirms internal consistency of the instrument and supports the latent structure assumption validated in subsequent PCA.

Figure 12.

Multidimensional design of gamification in inclusive education. Source: Authors.

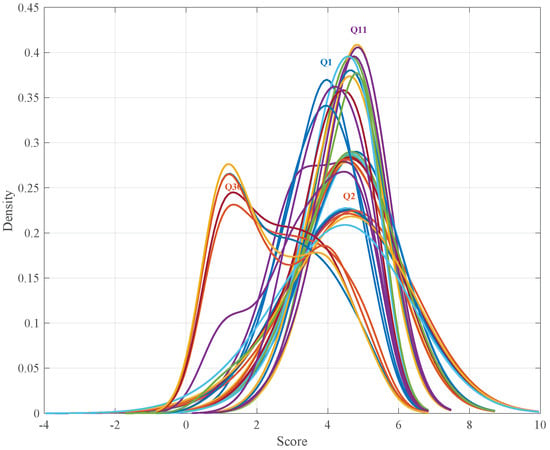

Figure 13 depicts smoothed response distributions using Kernel Density Estimation (KDE). To maintain clarity, only the peak of each curve was labeled to highlight the item identifier (Qn) without cluttering the plot. Densities were concentrated around high values for the majority of questions, confirming a positive skew. It is particularly evident in Q1, Q6, and Q10, whose KDEs peak near the upper limit of the scale, with minimal multimodal behavior.

Figure 13.

Multidimensional design of gamification in inclusive education. Source: Authors.

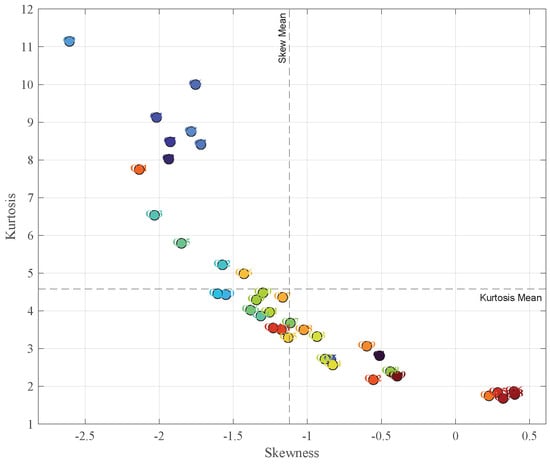

Figure 14 integrates skewness and kurtosis per item. Color-coded dots and dynamic annotations reveal items such as Q3 and Q14 with extreme values of positive skew and leptokurtosis, indicating strongly clustered high scores. Conversely, Q17 shows light platykurtic tendencies and mild left skew, suggesting broader dispersion and slightly more critical responses. The bivariate visualization also segments the questions into quadrants of statistical shape, aiding in psychometric interpretations.

Figure 14.

Multidimensional design of gamification in inclusive education. Source: Authors.

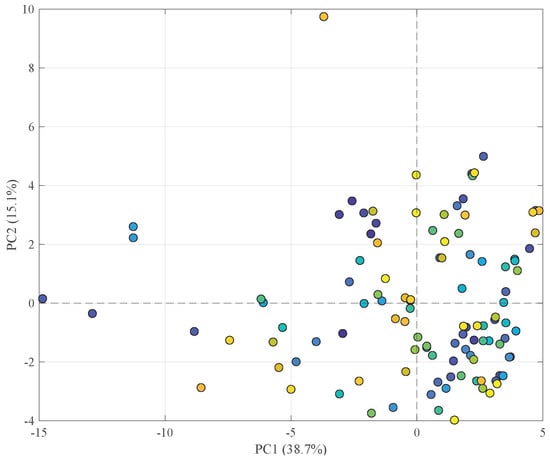

Figure 15 concludes the section with a principal component analysis (PCA) plot. The first two components explain a substantial portion of the variance (PC1: 32.4%, PC2: 18.7%). A homogeneous cluster of respondents is visible in the positive PC1-PC2 quadrant, indicating alignment in their perceptions. The scattered points along PC2 reflect diverging opinions on specific constructs. The visual balance and absence of isolated outliers support the reliability of the survey design.

Figure 15.

Multidimensional design of gamification in inclusive education. Source: Authors.

Overall, the statistical evidence underscores a predominantly positive attitude toward gamification, with high consensus on its benefits for motivation, participation, and learning autonomy. Specific items (e.g., Q4, Q7, Q12) consistently emerge as high-impact indicators, while a few items warrant refinement or context-specific reinterpretation due to dispersion (e.g., Q15, Q17). These insights inform future pedagogical strategies and instrument calibration.

5. Discussion

In the current context of inclusive education, implementing innovative strategies such as gamification and adaptive learning design has become increasingly crucial in enhancing the educational process for individuals with disabilities. This approach seeks to not only break down accessibility barriers but also to foster a learning environment in which each individual can develop their full cognitive, emotional, and social potential.

This section presents the positive effects, inherent challenges, and ethical implications of integrating gamification and learning strategies in specialized education, highlighting their impact on students’ academic development and quality of life. The use of gamification is an advance in the academic field; however, increasing its application requires teachers’ preparation, motivation, interest, and creativity. Educational institutions need to generate more tools and accessibility within the work area to facilitate the use of web pages and technological resources.

The results obtained are consistent with previous studies, such as those by [9,19], who highlight the usefulness of playful methodologies for reducing anxiety in the classroom and encouraging active participation. However, this study has significant limitations, including the absence of statistical inferential techniques to validate the relationships between variables. The concentration of the sample in a single country limits the extrapolation of results. Future studies could incorporate multivariate analyses or longitudinal intervention studies to evaluate the sustained effects of gamification on educational inclusion.

The results of this study must also be interpreted with caution, given the specific characteristics of the sample. All participants were teachers from public institutions located in Quito and Cuenca, which restricts the extrapolation of findings to other educational contexts within Ecuador and beyond. This geographical and institutional limitation, however, provides valuable insight into how contextual factors such as technological infrastructure and institutional support shape the feasibility of gamification in inclusive education. Furthermore, although the descriptive and inferential analyses presented here highlight strong associations between teachers’ perceptions and the adoption of gamified practices, they do not allow causal inferences. Future research should therefore move beyond descriptive approaches and incorporate multivariate statistical models—such as regression analysis or structural equation modeling—to better capture the complex interplay of variables such as age, training, and access to technology. In addition, longitudinal intervention studies would make it possible to examine whether the positive perceptions identified in this work translate into sustained improvements in inclusive educational practices over time, thereby strengthening the evidence base for the pedagogical value of gamification.

However, this varies according to the Internet’s reach in the workplace since it is the leading resource for classroom activities. It has become one of the most critical challenges for advancing this approach and therefore for its research.

The inclusion of games in the teaching process has been studied, showing diverse results in terms of student performance. Although some studies find no significant differences in the effectiveness of traditional methods, others highlight their benefits. In addition, a reduction in students’ anxiety towards the subject has been observed. Despite discrepancies, the potential of games to increase interest in students is recognized [39].

The results indicate that respondents consider this activity a good option for encouraging participation, teamwork, and promoting social inclusion, particularly among students with disabilities.

Another study explored gamification through adaptation, highlighting its effectiveness and the challenges it presents. Participating students demonstrated better understanding of the topics and scored significantly higher than their non-participating peers. Building on previous findings about the benefits of gamification in achieving learning objectives, students demonstrated improved self-reflection on their learning experiences. This study can serve as a guide for future implementations of gamification in teaching, and it is planned to increase the level of complexity of the game in future research [40].

This process involves challenges, such as students’ behavior during the activity. As this does not guarantee a positive response or total interest in every case, the behavior can be highly varied, thus highlighting the importance of adaptability and inclusion tailored to each student’s needs.

The results suggest that implementing player profiles can be an effective strategy to personalize the learning experience. It allows for greater flexibility in adapting game mechanics, which could speed up the development process and improve the user experience. Further research is recommended on how learners perceive adaptive games and their impact on motivation and learning. In addition, it is planned to design automatically generated adaptive games that match the player’s profile and investigate the context of use. This approach could lead to the development of prototypes that enable learners to participate in adaptive games autonomously, independent of the learning content [41].

Although the analysis has focused mainly on the frequency of responses, the interpretation of the data reveals significant trends that warrant further reflection. For example, the correlation between teaching age and positive perceptions of gamification suggests that new generations of educators are more open to pedagogical innovation. Likewise, data on technological limitations suggest an infrastructure gap that could be hindering the effective implementation of inclusive methodologies based on digital games. These findings, although descriptive, provide a solid foundation for designing training and equipment policies.

There is an infinite number of tools, programs, and activities in which gamification can be implemented, yielding results that can be applied to role-playing games, challenges, or missions, interactive narratives, and other contexts. Likewise, the study participants highlighted the digital applications they use in their classes, mainly Kahoot!, Quizizz, and Moodle, which are accessible and easy to use.

The effect of integrating activities with Kahoot! has been investigated. The tool indicated an improvement in students’ learning and motivation in science. Questionnaires were administered before and after the study in both the control and experimental groups, evaluating the participants’ understanding of the concepts explained. Significant improvement in scientific understanding was found among students who used Kahoot!, supporting the effectiveness of interactive platforms in understanding complex topics [42].

In addition, a notable increase in self-efficacy and interest was observed among students in the experimental group, highlighting the positive impact of Kahoot! on motivation to engage in scientific learning [42] actively.

Although further research is needed, it is suggested that integrating games into the curriculum can enhance students’ engagement, learning, and performance, thereby contributing to closing the gap in their understanding of biology [39].

The study results demonstrate a considerable positive impact among users, particularly in reducing the gap between awareness and sustainable action, which is partially attributed to the use of a gamification strategy. The promising potential of these applications is emphasized, and future directions for their development are proposed based on user preferences, including access to statistical data, practical examples, and gamification elements [43].

Gamification has also been seen as an alternative for improving and developing technological and cognitive skills, especially in students with disabilities, as it keeps them informed about technological advancements and the use of various tools and electronic devices.

The information presented yields similar results within the theme across different contexts, regions, and populations. Thus, it can be considered that gamification plays a fundamental role in the educational process and is a particularly viable option for the development of students with disabilities.

6. Conclusions

The integration of gamification in education has been widely welcomed, especially with the adoption of virtual classes and classrooms. It provides a novel and attractive approach that improves the interactivity and practicality of the teaching process. However, it is essential to note that its implementation requires a significant investment of time, a positive attitude, and technological readiness on the part of teachers.

This approach enables the individual needs of students, particularly those with disabilities, to be addressed by adapting games to prevent frustration and promote a relaxed yet effective learning environment. Although research on educational gamification is relatively limited, existing studies have consistently demonstrated benefits in terms of motivation and engagement.

The teachers participating in this study agree that games have a positive influence on students’ cognitive and social development, fostering teamwork and technological inclusion. In addition, gamification offers remarkable versatility by adapting to different learning areas facilitated by technological advances that simplify implementation.

This research addresses the issue of the underrepresentation of students with disabilities in traditional educational activities, highlighting the importance of an inclusive and personalized approach. It emphasizes the value of creating an academic environment that is both positive and exciting for learning despite challenges such as limited internet accessibility and inadequate teacher training.

The analysis of this study reveals several significant data points that both positively and negatively affect the use of gamification in education. It is concluded that this vast and constantly evolving field requires further study and experimentation, adapting to continuous technological and educational updates to meet the needs of new generations.

Among the main limitations of this research is the geographical restriction of the sample, which is limited to Ecuadorian territory, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other contexts. Likewise, the methodology based on descriptive analysis did not include inferential statistical techniques, which opens the opportunity for further studies that incorporate multivariate models and significance tests. Future research could explore the longitudinal impact of gamification in inclusive contexts and conduct cross-cultural comparisons to validate the global relevance of the findings presented here.

Author Contributions

X.R. conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the initial draft. E.I. analyzed the data and revised the draft. X.R. provided critical feedback and edited the manuscript. E.I. provided Zoom support and critical feedback. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Universidad Politécnica Salesiana and Smart Grid Research Group (GIREI) supported this work, under the project Innovative Learning in STEAM Education through Educational Engineering Considering a Comprehensive Approach to Improve Process and Outcomes.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the institutional support provided by Universidad Politécnica Salesiana (UPS), the Smart Grid Research Group (GIREI), and the IUS Network through RECI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ng, L.K.; Lo, C.K. Online Flipped and Gamification Classroom: Risks and Opportunities for the Academic Achievement of Adult Sustainable Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenson, R.J.; Lee, M.S.; Day, A.D.; Hughes, A.E.; Maroushek, E.E.; Roberts, K.D. Effective inclusion practices for neurodiverse children and adolescents in informal STEM learning: A systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cueva, A.; Inga, E. Information and Communication Technologies for Education Considering the Flipped Learning Model. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, K.K.A.; Behar, P.A. Pedagogical Models Based on Transversal Digital Competences in Distance Learning: Creation Parameters. RIED-Rev. Iberoam. Educ. A Distancia 2023, 26, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Singh, V.; Mahajan, N.; Garg, N. Game Based Learning—Immersive Teaching and Learning Platform through Metaverse. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Innovative Practices in Technology and Management (ICIPTM 2023), Uttar Pradesh, India, 22–24 February 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Lara, F.; Santos-Villalba, M.J.; Berral-Ortiz, B.; Martínez-Domingo, J.D. Inclusive Active Methodologies in Spanish Higher Education during the Pandemic. Societies 2023, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.J.; Delage, P.E.G.A.; Alencar, R.B.; Menezes, A.B. Percepção dos Estudantes em Relação a uma Experiência de Gamificação na Disciplina de Psicologia e Educação Inclusiva. Holos 2020, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebaikan, R.; Alajlan, H.; Almassaad, A.; Alshamri, N.; Bain, Y. Experiences of Middle School Programming in an Online Learning Environment. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoghue, A.; Sawyer, T.; Olaussen, A.; Greif, R.; Toft, L. Gamified learning for resuscitation education: A systematic review. Resusc. Plus 2024, 18, 100640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yangari, M.; Inga, E. Educational innovation in the evaluation processes within the flipped and blended learning models. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsun, I.; Malinen, O.P.; Yada, A.; Savolainen, H. Exploring the role of teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education, their self-efficacy, and collective efficacy in behaviour management in teacher behaviour. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 132, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebel, J.M. Combining Quest-Based Learning Gamification with Agile Project Management in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Gaming, Entertainment, and Media Conference, GEM 2023, Bridgetown, Barbados, 19–22 November 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenalt, M.H.; Mathiasen, H. Towards teaching-sensitive technology: A hermeneutic analysis of higher education teaching. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumpa, R.J.; Ahmad, T.; Naeni, L.M.; Kujala, J. Computer-based games in project management education: A review. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2024, 5, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, J.; Inga, E. Methodological experience in the teaching-learning of the English language for students with visual impairment. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G.; Keramopoulos, E.; Diamantaras, K.; Evangelidis, G. Integrating Augmented Reality, Gamification, and Serious Games in Computer Science Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, M.A.S. Beyond digital platforms: Gamified skill development in real-world scenarios and environmental variables. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2024, 8, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piki, A.; Markou, M. Digital Games and Mobile Learning for Inclusion: Perspectives from Special Education Teachers. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Behavioural and Social Computing, BESC 2023, Larnaca, Cyprus, 30 October–1 November 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Aguado, C.; Trigueros, R.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Navarro-Gómez, N.; Díaz-López, M.D.P.; Fernández-Campoy, J.M.; Gázquez-Hernández, J.; Carrión, J. An inclusive view of the disability of secondary school students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peuters, C.; Maenhout, L.; Cardon, G.; De Paepe, A.; DeSmet, A.; Lauwerier, E.; Leta, K.; Crombez, G. A mobile healthy lifestyle intervention to promote mental health in adolescence: A mixed-methods evaluation. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen, S.; Ropo, E.; Kupila, P. Constructing inclusive teacher identity in a Finnish international teacher education programme: Indonesian teachers’ learning and post-graduation experiences. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivadeneira, J.; Inga, E. Interactive Peer Instruction Method Applied to Classroom Environments Considering a Learning Engineering Approach to Innovate the Teaching–Learning Process. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Trigueros, I.M. Interdisciplinary Gamification with LKT: New Didactic Interventions in the Secondary Education classroom. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 14, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.L.; Santally, M.I.; Whitehead, J. Gamification as technology enabler in SEN and DHH education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 9031–9064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracqualursi, L.; Agati, P. Twitter users perceptions of AI-based e-learning technologies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Espinosa, J.A.; Vaquero-Abellán, M.; Perea-Moreno, A.J.; Pedrós-Pérez, G.; Martínez-Jiménez, M.D.P.; Aparicio-Martínez, P. Gamification as a Promoting Tool of Motivation for Creating Sustainable Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokovska, M.; Ferreira, V.N.; Vallušova, A.; Seberíni, A. E-Government—The Inclusive Way for the Future of Digital Citizenship. Societies 2023, 13, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-León, A.; Ortiz-Colón, A.M.; Rodríguez-Moreno, J.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M. Aprendizaje-Servicio lúdico en la formación inicial docente: Un estudio cualitativo. Texto Livre 2022, 15, e39171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, R.; Turnbull, D. Gamification in education: A citation network analysis using CitNetExplorer. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2023, 15, ep405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Alarcón, E.; Caizachana, A.; López, I. Gamification in the process of cognitive stimulation in children with Down syndrome. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2023, 8, 21265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alieto, E.; Abequibel-Encarnacion, B.; Estigoy, E.; Balasa, K.; Eijansantos, A.; Torres-Toukoumidis, A. Teaching inside a digital classroom: A quantitative analysis of attitude, technological competence and access among teachers across subject disciplines. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaki, S.H.; Al Mazrouei, A.K.; Mafarja, N.; Naseem, W.; Sial, M.A.; Naveed, R.T. Factors influencing inclusive teachers’ acceptance to adopt eLearning platforms in classroom: A case study in Oman. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1477659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiss, L.; Großschedl, J.; Wilde, M.; Fränkel, S.; Becker-Genschow, S.; Großmann, N. Gamification in education—teachers’ perspectives through the lens of the theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1571463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Bonilla, C.d.R.; Guerra-Arango, J.A.; Oviedo-Guado, D.A.; Murillo-Noriega, D.E. Inclusive education through technology: A systematic review of types, tools and characteristics. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1527851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Navas, S.; Ackaradejraungsri, P.; Dijk, S. Are there literature reviews about gamification to foster Inclusive Teaching? A scoping review of gamification literature reviews. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1306298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, B.; Cherian, J.; Jaya, P.J.; Kuriakose, L.; Leema, P.W. The ghost effect: How gamification can hinder genuine learning. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1474733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0306420221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Cole, M., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; ISBN 978-0674576285. [Google Scholar]

- Lantzouni, M.; Poulopoulos, V.; Wallace, M. Gaming for the Education of Biology in High Schools. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Lopes, F.; Fernandes, S. The Use of Gamification for Learning SCRUM: Findings from a Case Study with Information Systems Students. Trends High. Educ. 2024, 3, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, L.C.; Schrader, A. Student Player Types in Higher Education—Trial and Clustering Analyses. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayan, B.; Watted, A. Enhancing Education in Elementary Schools through Gamified Learning: Exploring the Impact of Kahoot! on the Learning Process. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, C.; Zanchetta, C.; Goldmann, E.; de Carvalho, C.V. The Use of Gamification and Web-Based Apps for Sustainability Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).