Abstract

The richness and complexity of consent present challenges to those aiming to make related contributions to computer information systems (CIS). This paper aims to support consent-related research in CIS by simplifying the understanding of existing literature and facilitating the framing of future consent management research. Firstly, it outlines existing consent management research and shows how it relates to the literature in law and ethics. Secondly, it presents some fundamental explanations and definitions that must be considered for further contributions to the consent management literature. Thirdly, it identifies five types of consent-related stances often taken in the consent management literature and explains each in some detail. Fourth, it explains one of the identified types of stances (i.e., the disciplinary stance) by expanding on the links between consent as a legal construct and its ethical counterpart. Fifth, considering another of the identified types of stances (i.e., the theoretical stances normally adopted in the consent management literature), the paper presents the key requirements for legally and ethically effective consent management based on three prominent theories. Sixth, it presents the identified types of stances in a conceptual model, contending that the model is novel, relevant, understandable, and useful.

1. Introduction

Given the references to consent in such texts as the Bible [1,2], which evidence the construct’s importance in the ancient world and in such belief systems as Christianity, the influence of religious forces on modern times [2] (pp. 7–8), [3] (ch. 3), and the multidimensional historical evolution of consent in general [1,2], [3] (ch. 3–6), it is comprehensible that consent plays an important role today, including in commerce, marriage, health care, clinical research, politics, social research, sex, and online interactions; e.g., see [2,4,5,6,7,8]. It is also unsurprising that consent is discussed so widely in so many disciplines, including psychology and psychotherapy [9,10], mathematics [11], the social and political sciences [1] (pp. 26–34), [12,13], ethics [3,5,14,15], law [5,16], and computer information systems (CIS) [4,17,18,19].

The consent management literature in CIS often involves the borrowing of consent-related models from mature disciplines, namely ethics and law, which revolve around the use of consent to waive bodily privacy rights, as well as the models’ application in relation to specific concepts—namely information privacy [20,21]—to specific contexts, such as e-health care [20,21,22] or online services [4]. Hence, the profoundness and complexity of consent and the related constructs also contribute to the interdisciplinarity [23,24] and sparseness [4] (pp. 1–2) of the consent literature in CIS, which formed largely independent clusters over the past few decades, and which as a result of the current situation can be classified and organised in many ways. This contributes to a key research problem in the consent management literature in CIS, i.e., the lack of clarity regarding the stances adopted by researchers when formulating, framing and/or addressing consent-related issues.

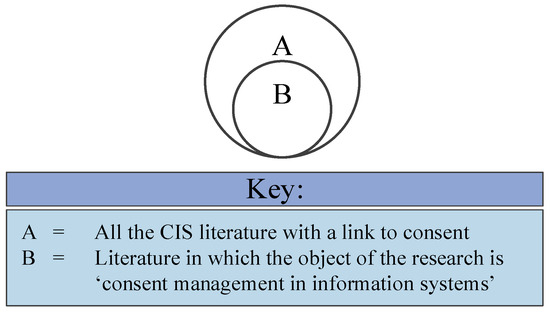

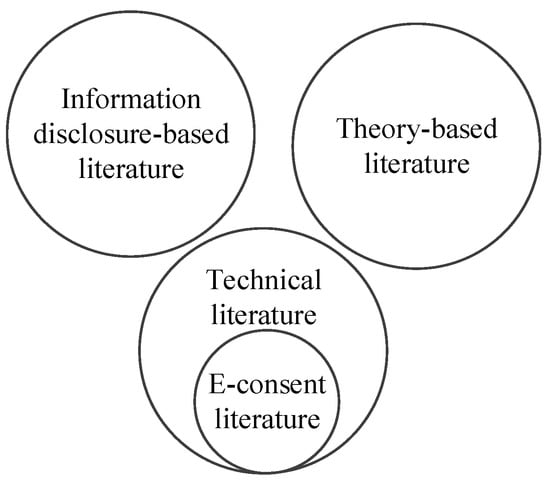

In this paper, the consent literature in CIS is considered organised, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The literature in scope A but not B includes that on specialised topics like persuasive techniques [25,26,27], deception in e-commerce [17,28], decision-making [18,29,30], participatory design [31], information privacy [32,33], and behavioural economics [32]. The literature in scope B (i.e., the consent management literature in CIS) may be categorised as information disclosure-based, theory-based, and technical literature. Also, the technical literature can be seen as including, as a subset, what this paper refers to as the ‘e-consent literature’.

Figure 1.

The relations between the literature in computer information systems (A) that is somehow related to consent and (B) where the object of research is consent management in information systems. Authors’ own compilation.

Figure 2.

A categorisation of the consent management literature in CIS, limited to scope B. Authors’ own compilation.

This paper aims to help address the lack of clarity regarding the stances adopted by researchers in the consent management literature, aiming to support the further maturity, and therefore also the converging, of the consent management literature. In view of this, the research question (RQ) guiding the work presented in this paper is as follows:

Research Question. Can a conceptual model be established—based on a review of existing consent management literature and conceptual investigations—which adds clarity regarding the stances adopted by researchers when formulating, framing and/or addressing consent-related issues in the domain of consent management in CIS?

Towards answering this RQ, this paper starts to address the following six exploratory questions (EQs), which reflect a focus on health care and clinical research, attributable to the strong links between informed consent and the medical field:

- Exploratory Question 1. What research was conducted in relation to consent and consent management in the context of CIS, and how does this relate to the consent literature in such other disciplines as law and ethics?

- Exploratory question 2. What are some fundamental notions that must be considered towards further contributions to the consent management literature in CIS?

- Exploratory Question 3. Which types of stances, and which stances, are often taken in relation to consent when contributions are made in the consent management literature?

- Exploratory Question 4. With reference to disciplinary and other stances, how does consent as a legal construct relate to consent as an ethical construct?

- Exploratory Question 5. Considering the theoretical stances normally adopted in the consent management literature, which currently reflect a focus on Faden and Beauchamp’s, Berg et al.’s, and Manson and O’Neill’s theories, what are the key requirements for legally and ethically effective consent management?

- Exploratory Question 6. Can the consent-related stances identified in Section 3 be presented in a relevant and useful conceptual model?

In view of the sparsity, interdisciplinarity and immaturity of the consent management literature and the conceptual nature of consent as a predominantly legal and ethical construct, the purpose of this paper was, largely, to enable a deeper understanding of the consent management literature based on a selection from such literature, and of how the selected literature relates to consent. Thus, the answers provided to the RQ and the EQs were based on a traditional literature review that maps the selected consent management literature and on a conceptual investigation that enables an understanding of consent as a construct based on a selection of literature predominantly from law and ethics. The deeper understanding emerging from these answers may enable future scoping and/or systematic reviews relating to consent management, which would probably involve substantially narrower and more focused research questions, as well as pre-defined and explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria, and enable the refinement of the mapping of the consent management literature, as well as refinements or extensions of the conceptual model proposed in this paper, in line with what is stated in Section 6.2.1.

The addressing of EQ 1 is considered useful insofar as it facilitates understanding of the status quo relating to ‘Consent management’ in CIS, especially for audiences unfamiliar with the complexity of consent or with the various types of links between consent, related concepts, and CIS. The intended audience includes information science researchers, technology philosophers and lawyers, ontologists, and practitioners. EQ 1 is addressed by the introduction and categorisation of the consent management literature, as provided in this section, and by answering the remaining EQs in Section 2, Section 3, Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6.

2. Consent-Related Definitions and Explanations

This section includes an answer to EQ 2. Thus, it informs on the nature of consent, reflecting one of two fundamental questions addressed in the ethics literature on consent [6] (p. 84); i.e., what is the nature of consent? More specifically, Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.3, Section 2.4, Section 2.5, Section 2.6, Section 2.7, Section 2.8 and Section 2.9 include definitions and explanations regarding the etymology of consent and consent as a verb, a noun, and a construct. It also defines and explains key consent-management terms, namely ‘consent management’, ‘object of consent’, ‘consent transaction’, and ‘consent process’, and includes an explanation regarding the links between ‘consent’ and ‘informed consent’. These definitions and explanations can simplify consent-related communications and are especially important to CIS researchers insofar as they range from the conceptual and theoretical aspects of consent, often examined in the legal and ethical literature, to the procedural aspects, often addressed in the CIS literature. The definitions and explanations are also essential for framing the answers provided to some of the other EQs.

2.1. Etymology of Consent

Etymologically, the verb ‘consent’ is rooted in classical Latin and can be traced back to the 12th century. The former part of the term, ‘con’, is rooted in the archaic form of the classical Latin words ‘com’ and ‘cum’, which refer to the prefix meaning ‘with’. The latter part, ‘sent’, is rooted in the Latin word sentire, which means ‘to perceive, feel’. Hence, the literal meaning of ‘consent’ is ‘feel together’. The term was attested as a noun from the 13th century [34].

2.2. Consent as a Verb

Consent, as a verb, refers to the act of ‘…[giving] an affirmative reply to…’ or ‘…respond[ing] favourably to…’ [35]. For example, by signing a consent form, a patient, A, consents (or signifies consent) to a surgeon, B, to perform surgery on A. Similarly, a party, X, may consent, with respect to the consent request made by another party, Y, internally, in X’s mind. The widely accepted ontological view is that even if there could be permission without its signification, it is the permission’s signification to another that transforms the relations between the relevant parties, rendering the consent useful [36] (pp. 9–11). Hence, Definition 1 is adopted in this paper.

Definition 1

(Consent: verb). To provide affirmative signification to another.

2.3. Consent as a Noun

Consent, as a noun, refers to ‘…[p]ermission to do something…’ [35]. For example, by signing a consent form, a patient, P, grants a consent (or permission) to a surgeon, Q, to operate on P. Although it may be argued that P can signify consent to himself/herself, in P’s mind, and that, therefore, a signification to another is inessential, the definition adopted in this paper (see Definition 2) renders the signification to a second party essential.

Definition 2

(Consent: noun). Permission to do something, which is signified to another.

2.4. Consent as a Construct

Given the definition of ‘construct’ as ‘…[a]n abstract or general idea inferred or derived from specific instances…’ [35], the following definition is adopted for ‘consent’ as a multifaceted construct:

Definition 3

(Consent: construct). An abstract idea derived from specific instances in relation to consent as a verb and as a noun.

2.5. Consent Management

‘Consent management’ is defined in two senses, as follows:

Definition 4

(Consent management: sense1). The act of managing the formation, use, and maintenance of one or more tools/artefacts that enable the execution of a consent transaction and, therefore, potentially, the transformation of the legal and/or ethical relations between the parties involved in the consent transaction.

Definition 5

(Consent management: sense2). A research area in direct relation to consent management in sense1.

2.6. Object of Consent

‘Object of consent’ is defined as follows:

Definition 6

(Object of consent). An action that is planned, at least to an extent, which would breach the legal and/or ethical rights of an individual, A, if it occurs in the absence of A’s consent or of consent by someone else, B, who acts on behalf of A.

2.7. Consent Transaction

Based on the ontological stances taken in this paper (see Section 3.2) and on Kleinig’s work [36], a ‘consent transaction’ is defined as follows. The definition applies to both implicit and explicit consent, as well as to both opt-in and opt-out consent:

Definition 7

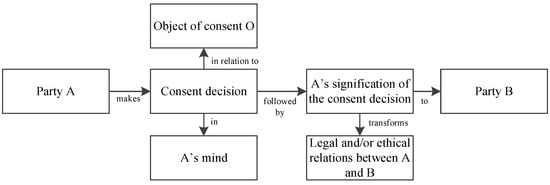

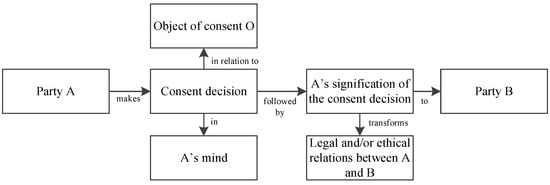

(Consent transaction). A three-place event that involves two participants, A and B, and an object of consent, O. The event involves (1) A’s consent decision, which occurs in A’s mind with respect to O, (2) A’s signification of A’s consent decision to B, and as a result, possibly, (3) successful alteration of the legal and/or ethical relations between A and B; see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A consent transaction. Authors’ own compilation.

2.8. Consent Process

The definition proposed for the ‘consent process’ is as follows and applies to both implicit and explicit consent, as well as to both the opt-in and opt-out forms of consent:

Definition 8 (Consent process).

A course of action that involves (and frames) the occurrence of a consent transaction and the actions that occur before and/or after the consent transaction.

2.9. Consent Vis-à-Vis Informed Consent

The key difference between ‘consent’ and ‘informed consent’ is that the latter makes a reference to the consent requester’s legal duty, by the legal doctrine of informed consent, to disclose information about the object of consent to the consent decision-maker. In comparison, while the records of information disclosure by the physician to the patient date back to the 19th century [3] (pp. 53–55), the legal duty for such disclosures was formally introduced in 1955 in Hunt v. Bradshaw, 88 S.E. 2d 762 (N.C. 1955). The duty was then established more formally in Salgo v. Leland Stanford Jr. Univ. Bd. of Trustees, 317 P.2d 170 (Cal. Ct. App. 1957) [3] (pp. 125–129), [5] (p. 44), leading to the concatenation of the terms ‘informed’ and ‘consent’. Subsequent cases, including Natanson v. Kline, 350 P.2d 1093 (Kan. 1960) and Mitchell v. Robinson, 334 S.W.2d 11 (Mo. 1960), have reinforced and further shaped both the duty and the concatenation [5] (pp. 43–46).

The linking of ‘informed’ and ‘consent’ has contributed to linguistic confusion, to the point that ‘consent’ and ‘informed consent’ are often used interchangeably in the literature. For instance, while Faden and Beauchamp argue that the consent decision-maker’s voluntariness and understanding are more important than the consent requester’s information disclosure [3] (p. 276), they consistently use ‘informed consent’ instead of ‘consent’ in [3]. Beauchamp has addressed this anomaly by stating a preference for ‘consent’ instead [37] (p. 55), sustaining the relative importance of the consent decision-maker’s understanding and voluntariness over that of the consent requester’s information disclosure. It is important to consider such linguistic confusions in contemporary research because, as Beauchamp claims, they influence the formation of consent theory and law [37] (p. 55). Similar confusions seem to influence the nature of the literature in CIS, too. In this paper, the terms are used interchangeably, and attempts are made to balance: (1) how the terms are used in the cited literature, and (2) abidance by the rationale described above, i.e., that informed consent is a kind of consent with a focus on the legal condition of information disclosure.

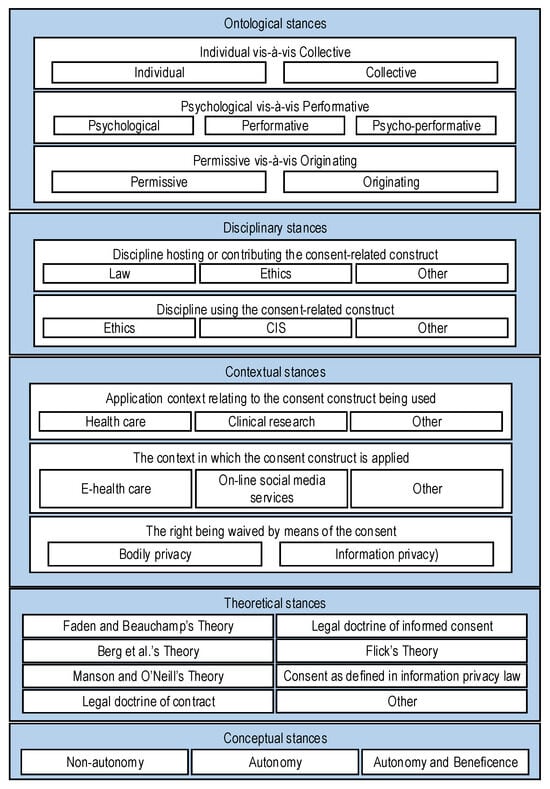

3. Framing Contributions in the Consent Management Literature through Stances

This section includes an answer to EQ 3. Section 3.1 identifies five types of stances often underpinning contributions in the consent management literature based on the results emerging from the authors’ review and classification of related literature, including that covering scopes A and B. Section 3.2 introduces the main ontological views relating to consent in ethics and the ontological stances often adopted in the consent management literature. In Section 3.3, it is argued that the disciplinary focus in the consent management literature is on consent as a legal and ethical construct and that the intra-disciplinary focus in law is on a specific type of legal instrument. In Section 3.4, regarding contextual stances, it is argued that the focus in the consent management literature has been on the contexts of health care and clinical research, as well as on the concept of information privacy. In Section 3.5, regarding theoretical stances, justifications are provided for the selection of the three theories mentioned in EQ 3, and references are made to the theories’ use and usefulness in the consent management literature. In Section 3.6, regarding conceptual stances, an outline is provided of the historical shift from consent as a construct largely unrelated to the concept of autonomy to a construct primarily based on autonomy. The section also introduces the contemporary debate on the role of autonomy and beneficence in consent and acknowledges the consideration of both autonomy and beneficence in the consent management literature.

3.1. Types of Stances Framing Contributions in the Consent Management Literature

The five types of stances identified as useful for framing and categorising contributions made in the consent management literature are ontological, disciplinary, contextual, theoretical, and conceptual. The ontological stances adopted determine what is considered to be the nature of consent. Questions relating to this include: does the research focus on consent between individuals or on consent between a governing entity and the collectives over whom it governs? The choice relating to this would link to various aspects relating to the contribution made in the consent management literature, including the disciplinary, contextual, theoretical, and conceptual stances adopted.

Given the nature of the existing literature, the disciplinary stances adopted are influenced by the ontological stances adopted. For example, while an ontological focus on individual and permissive consent would call for a disciplinary focus on consent as a legal and ethical construct, an ontological focus on collective consent would call for a disciplinary focus on consent as a political and social construct. The contextual stances are influenced by both the ontological and disciplinary stances adopted. For example, an ontological focus on individual consent and a disciplinary focus on consent as a legal and ethical construct is more likely to imply a contextual focus on consent in health care and clinical research in relation to the concept of bodily privacy than on consent in governance research. In contrast, an ontological focus on collective consent and a disciplinary focus on consent as a political and social construct will likely imply a contextual focus on consent in governance research.

The ontological, disciplinary, and contextual stances would also relate to the choice of consent theories adopted. For example, while an ontological focus on individual and permissive consent would justify a theoretical focus on Faden and Beauchamp’s theory or on the links between contract law and consent [38], an ontological focus on collective consent would be more likely to justify a theoretical focus on social contract theory instead. Finally, the conceptual stances would influence, and be influenced by, all other stances. For example, the conceptual view regarding consent as an autonomy-based construct would be more in line with Faden and Beauchamp’s theory than Berg et al.’s or Manson and O’Neil’s theories. Indeed, Berg et al.’s theory reflects the conceptual view of consent as a construct that balances autonomy and beneficence, and Manson and O’Neil claim to base their theory on a conceptual view that steers away from autonomy. More information about the use of the identified types of stances is provided in the following sections.

3.2. Ontological Stances Relating to Consent

The main ontological distinctions identified in the ethics literature are between individual and collective consent [36] (p. 6), [1] (p. 25), [2], between consent as a psychological phenomenon, a performative act, and a combination of both a psychological phenomenon and a performative act [36] (pp. 9–12), [6] (pp. 84–86), [7] (pp. 144–146), [38] (pp. 252–253), and between permissive and originating consent [4], [2] (pp. 2–3), [14]. More detailed information about this and about the ontological stances currently adopted in the consent management literature is available in Section 3.2.1, Section 3.2.2 and Section 3.2.3.

3.2.1. Individual Vis-à-Vis Collective Consent

The key difference between individual and collective consent is that the former refers to consent between natural and/or legal individuals, and the latter refers to consent between a government and the collectives over whom it rules. On the one hand, individual consent may involve, for instance, a physician and a patient, a psychotherapist and a client, or a service provider and a service user. On the other hand, collective consent in a democratic context may involve, for instance, the general population (represented by the electorate) and a government.

Theoretically, collective consent is more closely related to social contract theory (e.g., see [2,39,40]) than to the mainstream legal and ethical theories of informed consent as normally based upon or applied to health care and clinical research [1] (pp. 25–34). However, aspects of collective consent are often related to individual consent. For example, while physician–patient relationships involve consents between the physician and the patient, such relationships are normally framed in national healthcare policies formed and influenced by collective consents.

Thus far, the focus in the consent management literature has been on individual consent. Some may claim that it is or could be on the notion of collective consent instead, based on the view that certain service providers are sufficiently powerful to be considered as governments with powers over collectives of individuals. However, such a claim would not be justified or widely recognised. For instance, the plaintiff in Young v. Facebook, Inc. was unable to substantiate that Facebook acted as a state actor. Nonetheless, the consent management literature should not ignore the notion of collective consent. For example, it is possible to view instances of individual consent (e.g., a consent transaction involving a service provider and a service user) as framed in instances of collective consent. As a case in point, the use of a social media platform like Facebook is influenced by the laws imposed by the applicable governments.

3.2.2. Consent as a Psychological Phenomenon Vis-à-Vis a Performative Act

While consent as a psychological phenomenon refers to consent in the decision maker’s mind, independently from its signification to another party, consent as a performative act refers to the signification of a consent decision to another, as an action that is independent of the consent decision in the mind. Consent as a combination of both a psychological phenomenon and a performative act is based on the view that while consent must first exist in the mind, it will only alter the legal and moral relations between the parties involved and thus be useful if communicated to another.

The focus in the consent management literature is on consent as a combination of a psychological phenomenon and a performative act, based on the acceptance that (1) there could be no signification of consent unless there is a consenting mind state and (2) a consenting mind state without a signification would often be useless, especially in CIS contexts, where the focus is on information exchanges. However, in relation to this, consideration should be given to the fact that contemporary research and technological advancements—e.g., in neuroimaging and neuroethics [41] (pp. 334–335), and in the HCI area of mind-reading [42,43]—may continue to blur the distinction between a mind-state and a performative act.

3.2.3. Permissive Consent Vis-à-Vis Originating Consent

The distinction between permissive and originating consent, as described by O’Shea [2] (pp. 2–3), is so fundamental to consent management that it may be viewed as implicit in all considerations of consent. On the one hand, the idea of permissive consent, e.g., as considered by Manson and O’Neill [14] and Flick [4], refers to consent as the waiver of pre-established norms to ensure that an act otherwise implying some wrong does not do so. On the other hand, the notion of originating consent, which is often only recognised implicitly, refers to consent to the introduction, alteration, or endorsement of the norms waived in permissive consent.

The consent management literature focuses on permissive consent, i.e., the consent transactions that transform the legal and/or ethical relations between individuals through the waiving of pre-established norms. A focus on originating consent would shift the attention to the processes leading to setting, altering, and/or managing the norms in the first place, which is currently not widely considered in the said literature.

3.3. Disciplinary Stances Relating to Consent

In this paper, a distinction is made between disciplinary and intra-disciplinary stances. Disciplinary stances are further organised into two sub-types, i.e., stances relating to which discipline hosts or contributes to the consent-related construct (e.g., theory or doctrine) being used and stances relating to which discipline the construct is used. Intra-disciplinary stances refer to ones taken within a particular discipline. For example, relating to consent considerations from a legal perspective, an intra-disciplinary stance may imply the focus on the legal doctrine of informed consent rather than that on the legal doctrine of contract or on consent as defined in information privacy law. In this paper, the intra-disciplinary stances are referred to as ‘theoretical stances’ and are addressed in Section 3.5, as well as in other parts.

Regarding disciplinary stances, in the consent management literature, the focus with respect to the discipline using a consent construct is on CIS, insofar as the consent management literature exists primarily within the realms of CIS. The focus with respect to the discipline hosting or contributing to the consent-related construct being used is on law and ethics. Not much attention is given to other disciplines, such as those contributing to the social contract theory or closely related constructs. As an example, reflecting these stances, in the information disclosure-based literature, the focus is on the disclosure of information to the consent decision maker, in line with the legal condition of information disclosure as expressed in the legal doctrines of informed consent and contract. The technical literature (including the e-consent literature) focuses on the systems and processes that enable the execution of consent transactions in ways that transform the legal and moral relations between the parties concerned. In the theory-based literature, the focus is on the consideration of consent as examined through influential ethical theories, such as Faden and Beauchamp’s and Manson and O’Neill’s, as well as through related constructs, such as the Belmont report.

3.4. Contextual Stances on Consent

From a disciplinary perspective, the consent management literature focuses on consent as an ethical and legal construct. In contrast, from a contextual perspective, it is on (1) existing notions of consent as rooted and applied in health care and clinical research, with respect to the patient’s physical privacy and (2) the application of such notions to CIS contexts, predominantly with respect to the service users’ and others’ information privacy rights, often in the context of e-health care, but also in other contexts. Such observations enable a distinction between three types of contextual stances: (1) the application context relating to the consent construct being used (e.g., health care and clinical research), (2) the context in which the consent construct is applied (e.g., e-health care, or the use of online social media services), and (3) the right being waived by means of the consent (e.g., bodily privacy, or information privacy).

To explain the use of this three-fold distinction: if Faden and Beauchamp’s theory were to be applied to the design of the user-interface and/or business model of an online social media platform like Instagram or TikTok, the application context relating to the consent construct being used (i.e., Faden and Beauchamp’s theory) would be health care and clinical research, the context in which the consent construct is applied would be online social media services, and the rights being waived by means of the consent would be bodily privacy (in the case of Faden and Beauchamp’s theory) and information privacy (in the case of online social media). This means that a consent construct that applies to a context would be applied to a substantially different context.

The theoretical stances taken, as shown in the next sub-section, relate most closely to the contexts of health care and clinical research and to bodily privacy. While Faden and Beauchamp’s theory is intended to be conceptual [3] (pp. 276–287) and generic enough to apply to multiple contexts, it is based on a historical account of the evolution of consent in medical practice and clinical research and on the consideration of a wide range of healthcare-related examples and primary sources [3] (ch. 3–6). Similarly, the theory proposed by Berg et al. is primarily based on the legal doctrine of informed consent as applied to regulate the management of consent in health care and clinical research in the US [5]. Likewise, the focus in Manson and O’Neill’s theory is on malpractice and bioethics [14].

Corresponding with the strong links between the key theories and the medical sector, the consideration of consent in the consent management literature is often, but not always, related to health care and clinical research. For instance, Flick’s theory [4], which is the only ethical theory of informed consent specifically intended for information and communications technology (ICT), is based on Manson and O’Neill’s theory. However, this is not intended to always apply to health care or clinical research contexts. Similarly, the models proposed by Friedman et al. in [44,45] are based on Faden and Beauchamp’s theory [3] (ch. 7–10) and the Belmont report [46]. Once more, these are not intended for use exclusively in relation to health care or clinical research. Also, much of what is referred to as the ‘e-consent literature’ (e.g., [20,21,22]) revolves around the specialised context of e-healthcare, in which case, the application in CIS, too, is related to health care or clinical research.

Hence, clearly—in line with Mifsud Bonnici’s observations [47]—the consideration of consent in the consent management literature often applies theories addressing the waiving of the right to bodily privacy to situations involving the waiving of the right to information privacy. That this is often considered acceptable also aligns with the strong links that exist between the definitions of informed consent in online privacy legislation as employed in much of the contemporary research on online privacy (e.g., in European Directive 95/46/EC or in European Regulation 2016/679), and the definitions of informed consent in such clinical research-based constructs as the Nuremberg code and the Helsinki declaration.

3.5. Theoretical Stances Relating to Consent

Various theoretical (and intra-disciplinary) stances are taken in the consent management literature. For example, with respect to consent from a legal perspective, it is possible to focus on different types of legal instruments, yielding different results or addressing different contexts or situations. A focus on the legal doctrine of informed consent is likely to yield different results from a focus on the legal doctrine of contract or on privacy law. Indeed, the definitions of consent in privacy legislation, e.g., in the General Data Protection Regulation (EU Directive 2016/679), are often overly simplistic and widely considered inadequate and subject to significant reviews [48,49]. Hence, in much of the consent management literature, a preference is given to the conditions for legally effective consent as prescribed in the legal doctrine of informed consent as applied in the US, which offers richer definitions. This also means that the focus is on conditions intended for the waiving of physical rather than information privacy or other rights, which is considered acceptable, based on the assumption, in line with those adopted by others, like Mifsud Bonnici [47], that legal and ethical models of informed consent from mature fields like health care and clinical research may apply to online contexts.

Although the role of consent in healthcare-related statutory legislation is also to be acknowledged, such legislation is only considered sparingly in the consent management literature. The conditions for legally effective consent as established in such legislation tend to correspond with those defined in two commonly adopted legal instruments: (1) the conditions defined in the common law aspects of the legal doctrine of informed consent and (2) the simpler definitions defined in data protection regulation. Likewise, the link between consent and contract law is not considered in depth in the consent management literature. However, the conditions for legally effective contractual consent are comparable to those for legally effective consent as defined in the legal doctrine of informed consent and in online privacy law in the EU and the US. Additionally, it may be useful to note that while contract law regulates commercial agreements, information privacy is considered as extending beyond commodity insofar as its absence can lead to physical harm. Overall, with respect to consent from the legal perspective, the intra-disciplinary (or theoretical) focus in the consent management literature is on the conditions for legally effective consent, as prescribed in the legal doctrine of informed consent, as applied in the US.

With regards to the stances taken in ethics, Faden and Beauchamp’s theory [3] (ch. 7–10) was published in 1986—i.e., 39 and 22 years after the publication of the Nuremberg code and the Helsinki declaration—and is currently considered the key theory of informed consent [6] (p. 80), [14] (pp. 16–22), [50] (p. 100). The theory corresponds, in many respects, with Berg et al.’s theory [5], which is another key theory primarily based on the legal doctrine of informed consent as applied in the US. The two theories are aligned insofar as they define consent as based on the ethical principle of individual autonomy and, secondly, because they are based on consent as applied in the contexts of health care and clinical research. Nonetheless, while Faden and Beauchamp’s theory is intended to be generic [3] (p. 276–287) and, presumably, to apply to multiple contexts, the theory proposed by Berg et al. is mainly descriptive, intended to inform on the conceptual, normative, and procedural aspects of informed consent in health care and clinical research. Also, while Faden and Beauchamp offer a primarily ethical perspective on consent, the theory proposed by Berg et al. spans the ethical, legal, social, and medical perspectives. The focus of this paper, reflecting that in the consent management literature, is on these theories and the one proposed by Manson and O’Neill [14] for the following reasons:

- The focus in all three theories is on the notion of individual rather than collective consent, reflecting one of the ontological stances identified in this paper. Had the consent management literature focused on the notion of collective consent instead, it would have been appropriate to consider alternative theories, such as those revolving around the notion of social contract in politics, e.g., [39,40].

- Faden and Beauchamp’s theory is the most widely recognised autonomy-based theory of consent in ethics.

- The three theories already provide a useful baseline for consent management in CIS, given their consideration and application in ICT by Flick [4] and by Friedman et al. [44,51,52,53,54,55], and given Manson and O’Neill’s consideration of consent with respect to information privacy [14] (ch. 5).

- While Faden and Beauchamp’s theory is largely conceptual, partly because of the authors’ focus on what constitutes ethically valid or effective consent in the mind, the theory proposed by Berg et al. provides useful information on the procedural aspects of informed consent in health care. Hence, combining the two theories provides a balance between the notions of consent as a mind-state and a performative act, reflecting another ontological stance identified in this paper. Manson and O’Neill’s theory complements this insofar as it spans both views.

- While Manson and O’Neill’s theory is a relatively new contribution and not as widely recognised as those proposed by Faden and Beauchamp and Berg et al., it is still considered to comprise the most carefully stated objections to autonomy [37] (p. 59). Hence, the three theories provide a balanced view between contemporary autonomy and non-autonomy-based depictions of consent. Manson and O’Neill’s theory also complements and generally represents some of the views adopted by other prominent authors, e.g., as shown in Section 3.6.4. It may also inform us of possible future evolutions of consent, which may steer away from autonomy.

- The three theories provide conceptualisations based on consent practices in different jurisdictions. The theories proposed by Berg et al. and Faden and Beauchamp are based on consent practices in the US, while Manson and O’Neill’s theory refers to consent law and practice in the UK. Nonetheless, none of the theories is strictly bound to any jurisdiction.

For the sake of the usefulness of the conceptual model proposed in this paper, the options relating to the theoretical stance include, apart from the three selected theories, an option entitled ‘other’, which leaves room for the application of the conceptual model to support research not currently addressed in the consent management literature, such as relating to collective rather than individual consent, and beyond. This aligns with the fact that the proposed conceptual model is not intended to be exclusively descriptive but also to enable further research and investigations, which are likely to lead to the models’ own expansion and evolution.

3.6. Conceptual Stances Relating to Consent

This section outlines the historical shift from consent as a construct largely unrelated to autonomy to one primarily based on autonomy. It also introduces the contemporary debate on the role of autonomy in consent and justifies the view that the consent management literature focuses on consent as a construct based on both autonomy and beneficence.

3.6.1. The Early Role of Autonomy in Consent

Autonomy did not always play an important role in individual or collective consent. For instance, Aristotle’s perspective on collective consent was based on the formation of governments and the utility of political stability rather than on autonomy [2] (p. 5). Similarly, Plato was generally in favour of technocracy rather than democracy or autonomy, arguing that political institutions should shape rather than be shaped by the populace and that the function of the political community is merely educative and, therefore, paternalistic. Subsequent debates involved a mixture of perspectives, including such pro-democracy views as Hobbes’s and Locke’s, revolving around the idea that governments should ultimately be based on autonomous consents and social contracts, and such anti-democratic views as Rousseau’s and Marx’s [2] (p. 12).

3.6.2. Beneficence and Paternalism in Consent

Although references to beneficence and paternalism in collective consent were already implied by such thinkers as Aristotle and Plato in their preferences for political stability and technocracy, the most explicit reference emerged in the Hippocratic approach to medicine [3] (pp. 61–63), [56] (p. 12). It enabled physicians who participated in consent transactions with their patients to conceal most things from the patients [2] (pp. 5–6) and, as shown in Quote 1 below, explicitly discouraged, if not forbade, individual consents to such practices as abortion and euthanasia:

Quote 1. ‘…I[, the physician,] will follow that system of regimen which, according to my ability and judg[e]ment, I consider for the benefit of my patients, and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous. I will give no deadly medicine to any one if asked, nor suggest any such counsel; and in like manner I will not give to a woman a pessary to produce abortion…’ [57].

3.6.3. Recent Shift to a Balance between Autonomy and Beneficence

The shift from beneficence-based consent to consent as a construct based on a balance between autonomy and beneficence [3] (p. 59) has occurred over hundreds of years [3] (ch. 3–6). However, the definitive shift in health care and clinical research is widely recognised as occurring just after the Second World War, both legally and ethically. In the Nuremberg trials, physicians and scientists who conducted clinical research during the war were found guilty of disregarding the research subjects’ right to self-determination. This triggered the Nuremberg code, which has subsequently re-shaped modern consent management in medical practice and clinical research, transferring the focus from beneficence to autonomy [3] (pp. 86–88, 153–156), [4] (pp. 11–15).

3.6.4. A Contemporary Debate on the Role of Autonomy in Consent

The idea that consent should be based on autonomy has recently been disputed [37] (p. 59). For instance, Dawson argued that although consent, as the autonomy-based unattainable ideal conceptualised by Faden and Beauchamp, was a reasonable yardstick in recent medical research history because of the atrocities occurring in the Second World War, it is theoretically unjustifiable [50]. The author contended that the research community should, instead, aim for a theory of consent based on what is empirically known to be attainable. Similarly, Miller and Wertheimer refuted Faden and Beauchamp’s autonomy-based model and proposed a preface to a novel theory of consent that is based on the concept of fairness [6]. Manson and O’Neill also refuted autonomy as the base concept for informed consent and used the rejection as a basis for an alternative theory that focuses on informed consent as a ‘waiver of norms’ [14]. Flick endorsed Manson and O’Neill’s rejections of autonomy [4] (pp. 121–123) and used the authors’ theory to develop a new waiver-based theory of informed consent for ICT.

Such rejections of autonomy are, themselves, disputable. For instance, while Beauchamp recognised the meticulousness in Manson and O’Neill’s refutations [37] (p. 59), the author argued that they are not entirely justifiable, substantiating his view by the prominence of autonomy in Manson and O’Neill’s own theory [37] (pp. 58–61). Others have also identified weaknesses in Manson and O’Neill’s theory. DuBois, for example, argued that despite its primary focus on bioethics, it fails to cover important aspects of the core idea of informed consent in health care [58]. For instance, as the theory requires truthfulness without exception, it fails to support the widely accepted idea of therapeutic deception or privilege, e.g., as described in [5] (pp. 79–85). Arguably, such weaknesses in Manson and O’Neill’s theory should also shed doubt on the rejections of autonomy underpinning it.

3.6.5. Consent as a Construct Based on Autonomy and Beneficence

The consent management literature focuses on consent as a construct based on autonomy, more specifically, on the service providers’ respect towards the users’ autonomy on matters relating to information privacy. For example, the main topic in the information disclosure-based literature is the users’ reading and understanding of information disclosures made in the form of legal text (e.g., see [59]). The focus in the technical literature—including the e-consent literature (e.g., see [20,21,22]—is on the development of systems and processes that enable the capture and application of the users’ autonomous consent decisions. Finally, the focus in the theory-based literature is on models of consent that are based on either autonomy or autonomy and beneficence. For instance, Friedman et al.’s contributions [44,45,60]) are based on models that focus on autonomy. Flick’s informed consent theory for ICT [4] is based on Manson and O’Neill’s theory, which as argued by Beauchamp, rests substantially on autonomy [37] (p. 59). Bonnici et al. considered the concept of beneficence, apart from autonomy, to play an important role in ICT contexts, e.g., see [61,62].

4. Consent as a Legal Construct Vis-à-Vis an Ethical Construct

This section includes an answer to EQ 4. Thus, it presents an extended note on the relations between consent as a legal and an ethical construct. The said EQ is considered essential for the establishment of key facts about the nature of consent and the links and differences between the legal and ethical aspects. The answer to the same EQ aims to provoke deeper thinking towards the design of better consent management systems—as may be integrated into various constructs, including information systems—which better capture legally and/or ethically effective consent. It also acts as a prelude to the addressing of EQ 5. Section 4.1 outlines key links between consent as a legal and an ethical construct and shows that such links have influenced contemporary views on consent. Section 4.2 outlines key characteristics that differentiate consent as a legal construct from its ethical counterpart.

4.1. Links between Consent as a Legal and an Ethical Construct

As a legal construct, consent, which has evolved along with, and in many cases emerged from, consent in ethics, exists in various forms. Key consent-related legal tools in the UK and the US include the legal doctrine of informed consent, informed consent law, and legal theories of informed consent. The legal doctrine of informed consent refers to a legal framework that encompasses the consent-related rules, procedures, and tests established through precedent in the common law and the statutory law that supports such common law [3] (p. 25), [2] (p. 22), through which judgments can be determined in clinical research- or healthcare-related legal cases. Informed consent law refers to the statutory law that forms part of the legal doctrine of informed consent and includes such acts as the Mental Health Act of 1983, the Human Tissue Act of 2004, the Mental Capacity Act of 2005 (see [2] (p. 22)), the Suicide Act of 1961, and the Death with Dignity Act of 1994. The legal theory of informed consent refers to the theory that underpins the legal doctrine of informed consent, which often corresponds with ethical theory [5] (ch. 1).

Key consent-related legal tools in the UK and the US also include collective consent law, which refers to the legal constructs that provide legal bases for the formation of civil societies and legal systems. They also include tangential consent law, which refers to legal constructs with tangential references to informed consent. For example, consent with respect to the legal right to information privacy in online contexts is partly regulated by online privacy legislation, which requires the data controller or data processor to obtain the data subject’s autonomous consent for the processing of the data subject’s personal data. In exceptional cases, privacy law also provides for the data controller’s or processor’s overriding of the data subject’s consent decision. In various jurisdictions, consent management concerning information privacy is also regulated and influenced by legal tools such as the Communications Decency Act (CDA). This US law forms part of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the European Directive 2000/31/EC, and such precedents as Cubby, Inc. v. CompuServe, Inc., Stratton Oakmont, Inc. v. Prodigy Services Co., Zeran v. America Online, Inc., and Barnes v. Yahoo!, Inc.

The links between legal and ethical consent are recognised by key authors like Berg et al. [5] (ch. 1) and correspond with the widely accepted view that although structures of legal principles do not correspond directly with those of moral principles, moral principles are expressed and enforced by the law in the form of rights and duties devised for the specific purposes of a legal framework [3] (p. 23). Such principles have influenced and are manifested in the contemporary notions of consent in various ways, including as follows:

- The different ethical notions that justify the formation of governments over consenting collectives have influenced and were eventually manifested in the legal theory and law that nowadays legitimises the constitution of such legal mechanisms as statutory law.

- Regulatory and ethical tools like the Nuremberg Code, the Helsinki Declaration, the Belmont report [46], and others (e.g., [63,64]) have evolved into and contributed to the formation of the present legal theories of informed consent [3] (p. 59), [5] (p. vii), the legal doctrine of informed consent as applied in the US [5] (p. 12), and the legal doctrine as applied in such other common law jurisdictions as Australia, Canada, England, and Wales [65].

- The physician’s beneficence towards the patient as rooted in the Hippocratic approach to medicine has transcended to the legal doctrine of informed consent [5] (pp. 18–20, 148–149) and to such international, national, and organisational-level tools as laws, regulations, policies, standards, guidelines, codes of practice, procedures, and management systems; e.g., [3] (ch. 4–6), [50] (pp. 101–102).

- Legal scholars, like Solove, discuss consent as a waiver of legal rights (e.g., the legal right to information privacy [66,67]) in ways corresponding with the view of consent as a waiver of ethical rights as discussed by authors like O’Shea [2], Flick [4], and Manson and O’Neill [14].

4.2. Differences between Consent as a Legal and an Ethical Construct

The following are key characteristics differentiating consent as a legal construct from its ethical counterpart:

- Responsibility and liability: the focus on responsibility and liability is stronger in legal than ethical consent and is reported to date back to the sixth century [2] (p. 9). It reflects the importance of the definition and assignment of legal responsibility and liability in the legal context. It also reflects that there are stronger links between legal rather than ethical consent and the legal doctrine of tort [65]. According to Berg et al. [5] (ch. 6) and Faden and Beauchamp [3] (pp. 25–30), in the US, it is the tort concept of liability that provides a consequential reason for medical professionals to participate in consent processes trustingly. For instance, if a physician fails to adequately balance beneficence with autonomy (e.g., by failing to override the patient’s autonomy in the case of patient incompetence), the professional could be civilly or criminally blameable, and hence liable, under one of the two predominant theories of liability, i.e.,: (1) battery, which is an intentional tort, or (2) negligence, which is an unintentional tort. In civil cases, such torts could enable the patient to obtain redress for damages resulting from unauthorised treatments.

- Visibility and enforceability: there is a focus, in legal consent, which is not as intense in the ethical counterparts, on what can be seen and therefore verified to have happened. This reflects the fact that mere philosophical distinctions between the legal and the illegal are unlikely to render legal prescriptions enforceable. For instance, from a practical perspective, it would be useless to make a philosophical distinction between intentionality and non-intentionality unless a court of law could use the distinction to determine the presence or absence of intentionality.

- Consent and the transformation of legal rights and duties: in tangential law, consent, as a legal construct, enables individuals to autonomously waive legal rights or agree to legal duties. For example, in the EU and the US, consent, as defined in online privacy legislation, enables a data subject to waive some of the data subject’s information privacy rights [48], [66] (ch. 1), [68] (ch. 13–14). Similarly, by the UK’s Theft Act of 1968, consent enables individuals to transfer valuable things to others and, therefore, to legalise actions that would otherwise constitute theft. As an example of the acceptance of a legal duty, in contract law, which can also be considered tangential in relation to consent, consent enables the parties to a contract to accept the relevant terms and conditions, which necessarily imply agreement to legal rights and duties [69] (ch. 3–11). Note that not all legal rights may be waived by consent. For instance, in most European countries, in England and Wales, a patient cannot legally waive his/her right to physical privacy for euthanasia.

- Links to contract law: the consensus, e.g., among Faden and Beauchamp [3] (p. 310), Bix [38] (p. 251), Gautrais [70], and Schuck [71] (p. 900), is that there are strong links between consent (more so as a legal than an ethical construct) and contract law. Such links are only tangential in the sense that the primary role of contract law is to facilitate legally enforceable promises, with the contractual parties’ consent to such promises constituting just one of many conditions for legally enforceable contracts.

5. The Requirements for Legal and Ethically Effective Consent

This section includes an answer to EQ 5, addressing the second of the two fundamental questions addressed in the ethics literature on consent [6] (p. 84); i.e., what renders a consent morally transformative? It also reflects the counterpart question addressed predominantly in the legal literature, i.e., what renders a consent legally transformative? More specifically, Section 5.1, Section 5.2 and Section 5.3 present the requirements for legally and ethically effective consent management based on the theories proposed by Faden and Beauchamp [3] (ch. 7–10), Berg et al. [5], and Manson and O’Neill [14], respectively. Finally, Section 5.4 includes a summary of the key conditions for legally and ethically effective consent.

5.1. The Requirements Based on Faden and Beauchamp’s Theory

Faden and Beauchamp distinguish between ‘Consent in sense1’, also referred to as ‘valid consent’ (see Section 5.1.1), and ‘Consent in sense2’, also referred to as ‘effective consent’ (see Section 5.1.2). They also recognise an intersection between the two and focus on the conditions for valid consent.

5.1.1. The Conditions for Valid Consent

Based on Faden and Beauchamp’s theory, an individual’s consent is only valid if it is substantially autonomous [6] (p. 81), [50]. To back this statement, the authors propose a definition for ‘substantial autonomy’ that is (1) idealistic rather than pragmatic or purely prescriptive, (2) ambiguous by design, and (3) subjective, resting on the authors’ views on the nature of ‘fully autonomous action’ [3] (pp. 238–248). The condition of substantial autonomy is broken into three sub-conditions: substantial understanding, substantial voluntariness, and intentionality. While authenticity is identified as a possible fourth sub-condition [3] (pp. 262–268), the theory focuses on the three listed above, of which the first two are depicted as continuum conditions and the third as a dichotomous condition. The condition of substantial understanding (i.e., the consent decision-maker’s understanding of the object of consent) contrasts with an often-competing condition in the law—e.g., in the legal doctrine of informed consent, online privacy law, or contract law—that calls for the consent requester’s information disclosure to the consent decision-maker instead. Faden and Beauchamp’s preference for the condition of understanding over that of information disclosure is based on the view that while autonomous authorisation without information disclosure may be possible (e.g., in the case of a heart surgeon consenting to heart surgery on him/herself), autonomous authorisation without understanding of the object of consent is not [3] (p. 276).

The Condition of Substantial Understanding

Faden and Beauchamp define the threshold that separates substantial from unsubstantial understanding through a borderline (or range) that represents ambiguity and state that, in practice, the definition of the borderline would, and should, be subject to policymaking. By doing so, the authors indicate a link between what they refer to as valid consent, which is a purely conceptual construct, and effective consent, which, by definition, is subject to policymaking. In detailing their views on the role of substantial understanding as a conceptual condition, the authors also discuss the following in some detail [3] (ch. 9):

- A differentiation between the ideas of ‘understanding that’ and ‘understanding what’.

- A distinction between ‘belief’ and ‘understanding’.

- A distinction between ‘true’ and ‘false’ belief.

- A distinction between ‘belief’ and ‘accurate interpretation’ contends that false beliefs do not necessarily hinder understanding if there is an accurate interpretation.

- The ambiguity related to the standards regarding the acceptability of beliefs as true or false.

- A distinction between ‘important’ and ‘unimportant information disclosures’.

- A distinction between ‘material’ and ‘relevant’ information, identifying the latter as what is needed for substantial understanding.

- A distinction between ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ standards regarding the determination of the information that should be disclosed in relation to the object of consent.

- The role of ‘time’ and ‘timing’ in the patient’s understanding.

- The positive impact on the degree of ‘patient involvement’ in communication and decision-making in cases where the consent transaction is framed in a participatory process over an extended period.

- The role of emotion, cognitive capacity, and the physical state of an individual in the individual’s understanding.

- The impact of information framing on a patient’s understanding of that information.

- The role of the mechanisms that enable the authentication, measurement, or testing of the consent decision-makers understanding of the object of consent, especially in the context of research in consent management, e.g., questionnaires to test the patient’s understanding of the physician’s information disclosure on the risks and the benefits involved in the treatment proposed.

The Condition of Substantial Voluntariness

The condition of substantial voluntariness is also defined as a continuum, which ranges from ‘hypothetically full voluntariness’ (associated with ‘persuasion’; see definition 9) to ‘non-voluntariness’ (associated with ‘coercion’; see definition 10). All points in between ‘full voluntariness’ and ‘non-voluntariness’ correspond to ‘manipulation’ (see definition 11). Faden and Beauchamp also map (1) ‘non-substantial voluntariness’ with ‘substantial manipulation’ and (2) ‘substantial voluntariness’ with ‘non-substantial manipulation’.

Definition 9

(Persuasion). The intentional and successful attempt to induce a person, through appeals to reason, to freely accept as his or her own the beliefs, attitudes, values, intentions, or actions advocated by the persuader [3] (p. 347).

Definition 10

(Coercion). Intentional and successful influence on another person by the presentation of credible threats of unwanted and avoidable harm so severe that the person is unable to resist acting to avoid it [3] (p. 339).

Definition 11

(Manipulation). A type of influence strategies which are neither instances of persuasion nor instances of coercion, and which include any intentional and successful influence of a person by non-coercively altering the actual choices available to another or by non-persuasively altering the other’s perceptions of those choices [3] (p. 354).

Although Faden and Beauchamp provide a conceptual definition of the threshold separating substantial and unsubstantial voluntariness, they specify that the definition of the threshold per se would, and should, in practice, be subject to policymaking. As in the case of substantial understanding, by doing so, the authors indicate a link between their definitions of valid and effective consent. They also detail their views on the constitution of ‘substantial voluntariness’ [3] (ch. 10), discussing the following concepts and ideas, among others:

- The nature and role of ‘threats’ and ‘offers’ in the contexts of coercion and manipulation.

- The difference between ‘intentional coercion’ and ‘unintentional coercive situations’.

- ‘Resistibility’ as either an ‘objective’ or ‘subjective’ criterion distinguishing between coercive and non-coercive threats.

- The role of ‘warnings’ and ‘predictions’ in persuasion.

- The links between ‘reason’ and ‘justified belief’ in relation to persuasion.

- The idea of ‘self-persuasion’.

- The distinction between ‘manipulation of options’ and ‘manipulation of information’ is also referred to by Friedman et al. in [60].

- The idea of ‘psychological manipulation’.

- The intricate problem of ‘role constraints’.

The Condition of Intentionality

Faden and Beauchamp define ‘intentionality’ as a dichotomous rather than a continuous condition and discourage its definition as a continuous condition based on two main arguments. Firstly, extending the dichotomy into a continuum is too difficult because too little is known about the cognitive events or processes required for intentional action [3] (pp. 243–244). Secondly, since there is a general correlation between intentionality to do something, X, and understanding that one is doing X, and since ‘understanding that’ is defined as a continuous condition, depictions of intentionality as a continuum construct are inessential [3] (pp. 248, 299). The authors then refine the condition by narrowing the scope from ‘intentionality’ to ‘intentional action’, which they define as: ‘…action willed in accordance with a plan, whether the act is wanted or not…’ [3] (p. 243), and propose the following concepts and ideas in relation to ‘intentional action’:

- If an agent, A, plans to do an action, B, with a conception, C, of how to do B, and A does B by accidentally causing an alternative conception, D, instead of C, then A accidentally and not intentionally does B. In alternative terms, if, upon reflection, A cannot say that A has done B in the planned manner C, then A has not acted intentionally [3] (pp. 242–243).

- If an agent, A, plans to do an action, B, with a conception, C, of how to do B, and A does C, which leads to an alternative action, D, instead of B, then A has accidentally and not intentionally done D. That is, if A substantially understands that C leads to B but C leads to D, then A has not acted intentionally in doing D [3] (p. 243).

- It may be argued that if an agent, A, does a sub-action, B, that A knows to involve another sub-action, C, with the intention of ultimately doing a primary action, D, then A intentionally does B and D, but not C. However, it may also be argued that C is intentional because it is ‘willed in accordance with a plan’ and that A’s motivation for C may reflect conflicting wants and desires. The latter argument reflects Faden and Beauchamp’s view [3] (p. 244) as expressed in their definition of intentional action: i.e., ‘…intentional action is action willed in accordance with a plan, whether the act is wanted or not…’ [3] (p. 243) 763.

- If an agent, A, does an action, B, which A does not know to involve a sub-action, C, then A does not intentionally do C [3] (p. 244) 765.

- ‘Intrinsic wanting’ is when an agent, A, wants to do an action, B because A wants B for its own sake [3] (p. 245) 767.

- ‘Instrumental wanting’ is when agent A wants to do action B to achieve goal C because A believes B to be the means to achieve the wanted goal C [3] (p. 245) 769.

- A ‘tolerated action’ is an intentional action A that agent B does not want or desire, all other things being equal, but tolerates to achieve a goal C. Note that others argue that tolerated actions are unintentional [3] (pp. 245–246).

- Although the condition of intentionality is defined as a dichotomy rather than a continuum construct, it is possible to conceptualise it differently. For instance, it is possible to define subtly different types of intentionality, like ‘willingness’ and ‘eagerness’ [3] (pp. 246–247).

5.1.2. Effective Consent

Faden and Beauchamp define ‘effective consent’ as follows:

- A type of consent that should, but is not required to, maximise the satisfaction of the conditions for valid consent [3] (pp. 283–287).

- ‘…[A policy-oriented type of consent] analy[s]able in terms of the web of cultural and policy rules and requirements of consent that collectively form the social practice of informed consent in institutional contexts where groups of patients and subjects must be treated in accordance with rules, policies, and standard practices…’ [3] (pp. 277, 280).

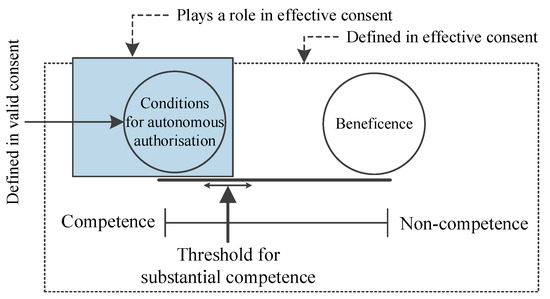

A key condition that the authors define in the realms of effective consent is that of the patient’s substantial competence [3] (ch. 8), which they describe as a gatekeeping condition facilitating a balance between (1) the medical professional’s duty to respect the patient’s autonomy, and (2) the medical professional’s beneficence towards the patient; see Figure 4. The authors specify three components to the normative question regarding the distinction between substantial and unsubstantial competence, which they describe as depending on moral and policy questions: (1) the establishment of the requisite abilities, (2) the fixing of thresholds for each of the abilities established in (1), and (3) empirical testing for (2) [3] (p. 290).

Figure 4.

Competence, as a gatekeeping concept in valid and effective consent, facilitates different autonomy/beneficence balances. Authors’ own compilation, based on Faden and Beauchamp’s theory [3] (ch. 7–10).

5.2. The Requirements Based on the Theory Proposed by Berg et al. [5]

Berg et al. attribute three interrelated meanings to ‘informed consent’ [5] (p. 3):

- A set of legal rules that prescribe behaviours for interactions between physicians and patients and that provide for penalties in the case of deviations from those rules.

- An ethical doctrine that is based on the value of autonomy and promotes the patients’ right to self-determination regarding medical treatment.

- An interpersonal process whereby physicians and patients interact with each other to select an appropriate course of medical care.

While the authors consider ‘informed consent’ in all three senses, a significant portion of their contribution is based on the tracing of the evolution of the doctrine of informed consent from its roots in ethical theory to its embodiment in contemporary informed consent law in the US [5] (p. vii).

5.2.1. Autonomy-Based Conditions for Legally Effective Informed Consent

Based on the authors’ depiction of the legal doctrine of informed consent, the three main conditions for a patient’s consent to be considered autonomous are: (1) the patient’s voluntariness to consent [5] (pp. 67–70), (2) the patient’s understanding of the object of consent [5] (pp. 65–67), and (3) the physician’s information disclosure to the patient [5] (pp. 43–46). A fourth condition, which the authors do not discuss in much detail, is the patient’s intentionality to consent [5] (p. 25).

The Condition of Voluntariness

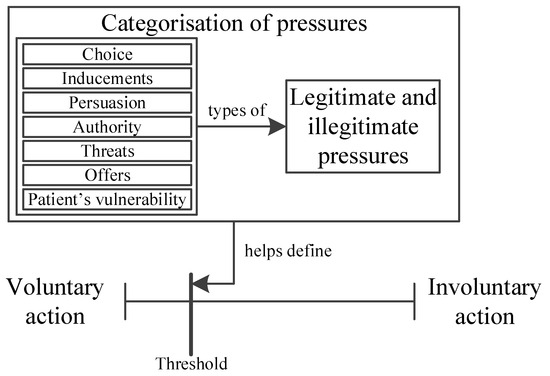

Although, based on the legal doctrine of informed consent, the consenter’s voluntariness is necessary for legally effective consent, Berg et al. noted that it was difficult to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary action. While legal litigation would shape the thresholds for the distinction between voluntariness and involuntariness (e.g., by defining what constitutes duress and illegitimate pressure), there was virtually no litigation concerning this. Therefore, the authors drew conclusions on the matter from other legal areas that require voluntariness. In doing so, they identified various types of pressure that could influence the patient’s voluntariness to consent, including choice, inducements, persuasion, authority, threats, offers, and vulnerability [5] (pp. 58–60, 67–70). They also differentiated between legitimate and illegitimate pressures; see Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Forms of pressure that help define the threshold that separates voluntary from involuntary action. Authors’ own compilation, based on Faden and Beauchamp’s theory [3] (ch. 7–10).

The Condition of Information Disclosure

Berg et al. affirm that despite the introduction of the legal duty of information disclosure in 1955–1960, there are guidelines but no clear contours for what constitutes a legally effective information disclosure. They categorise these guidelines, which Faden and Beauchamp refer to as the ‘standards of disclosure’ [3] (pp. 30–34, 305–306), into three classes:

- The ‘professional and reasonable person standards’ [5] (pp. 46–47).

- The ‘patient-oriented standards’ [5] (pp. 48–51).

- The ‘mixed standards’, which exist in the blurred intersection between the previous two [5] (pp. 51–52).

Not all American jurisdictions adopt the same standards of disclosure:

- In most US jurisdictions, the physician considers the following properties of risk in deciding which information to disclose to the patient [5] (pp. 55–58): (1) the nature of the risk, (2) the magnitude of the risk, (3) the probability that the risk might materialise, and (4) the imminence of risk materialisation.

- In many jurisdictions, the disclosure of the benefits associated with the object of consent is considered crucial in circumstances where the procedures would be diagnostic rather than therapeutic or where the anticipated benefits would be something less than full relief of the patient’s suffering [5] (p. 61).

- In some jurisdictions, remote, minor, known, or common risks are exempt from mandatory disclosure.

- In some jurisdictions, statutes require that certain risks, such as those of brain damage, be mentioned by the physician, even if they are very unlikely to occur.

- In other jurisdictions, like the state of Texas, panels of physicians and lawyers are appointed to develop lists of the medical procedures and the risks that must be disclosed for each procedure [5] (pp. 57–58).

The Condition of Understanding

Berg et al. argue that while it is clear by the legal doctrine of informed consent that a physician has both a duty to disclose information to the patient and a duty to obtain consent, it is less clear whether the physician has a duty to ascertain the patient’s understanding of the information disclosure. It is also unclear whether the physician is obligated to withhold treatment until the patient understands the physician’s disclosure of information. Also, if the physician is obligated to withhold treatment, it is unclear how such duty would be fulfilled. The authors identify the following causes for such ambiguity [5] (pp. 66–67):

- The language used in the applicable judicial opinions often fails to distinguish between terms like ‘inform’, ‘disclose’, ‘tell’, ‘know’, and ‘understand’, causing uncertainty on the true nature of the obligations imposed.

- The courts appear uncertain as to the underlying purposes of the law. It could be primarily about choice, regardless of the nature of the subject’s understanding, or it could be about understanding per se.

- Although most legal cases do not expressly hold that the patients must understand the information disclosure before their decision may be considered legally valid, there is some support in dictum in the case law regarding incompetence for the view that the patients must understand.

Berg et al. argue that whether the law requires the patient’s understanding of the physician’s information disclosure, such understanding seems to be an integral component of Katz’s idea of informed consent. Hence, they conclude that physicians dedicated to the principles underpinning the legal doctrine of informed consent should take steps to ensure the patients’ understanding, even in the absence of a legal requirement [5] (p. 67).

5.2.2. Operationalisation of a Balance between Autonomy and Beneficence

A physician has a Hippocratic duty to act beneficently towards the patient and a legal and ethical duty to respect the patient’s autonomy. According to Berg et al., based on the legal doctrine of informed consent, while beneficence may not be waived [5] (p. 119), autonomy can, mainly based on the following exceptions: see also [3] (pp. 35–39):

- Incompetence: an exception based on the patient’s legal (in)competence; see also Section 5.2.3.

- Emergency: an exception based on the presumption that all patients consent in emergency cases, i.e., based on the view that reasonable persons would consent if they were able to do so [5] (pp. 76–79).

- Therapeutic privilege: a beneficence-based exception that enables the physician to hide relevant information from the patient if the disclosure would be harmful to the patient [5] (pp. 79–85).

- Autonomous waiving: an exemption based on the patient’s right to autonomously waive his/her own right to give autonomous consent, e.g., by authorising the physician to act as deemed appropriate [5] (pp. 85–90).

- Compulsory treatment: an exemption based on the view that it is not solely the individual’s health that plays a role in a consent decision but also society’s interest in protecting others, e.g., by treatment for the dangerous mentally ill or for patients with infectious diseases [5] (pp. 90–91).

5.2.3. The Exception of Incompetence

As indicated in Section 5.2.2, by the legal doctrine of informed consent, competence is a medical gatekeeping concept that enables a special kind of balance between the physician’s duty to respect the patient’s autonomy and the physician’s beneficence towards the patient. Essentially, where the physician or a trusted third party (e.g., a court of law or an ethics committee) deems the patient medically or legally incompetent, the physician’s duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent is waived. What happens instead, wherever possible (e.g., in non-emergency cases), is that the responsible party (e.g., the physician or a trusted third party) appoints one or more surrogate decision-makers (e.g., family members), either to make decisions or to assist in the making of decisions on behalf of the patient, depending on the rules that apply in the particular context or jurisdiction [5] (pp. 109–124). For further information about incompetence as a waiver of the physician’s duty to respect the patient’s autonomy, refer to [5] (ch. 5), where Berg et al. discuss three ideas in particular: the criteria for sufficient competence, the methods employed for the formation of such criteria, and the procedural issues in relation to the roles of surrogate decision-makers and trusted third parties.

5.2.4. Liability and Responsibility

According to Berg et al. [5] (ch. 6), the tort concept of liability plays an important role in the legal doctrine of informed consent, providing a consequential reason for medical professionals to trustingly participate in consent processes. For instance, if a physician fails to adequately balance his/her beneficence towards the patient with his/her duty to respect the patient’s autonomy (e.g., by failing to override the patient’s autonomy in cases of incompetence), then the physician could be civilly or criminally blameable and, hence, liable under one of the two predominant theories of liability: (1) battery (being an intentional tort), or (2) negligence (being an unintentional tort). In civil cases, such torts could enable the patient to obtain redress for injuries resulting from unauthorised treatments. Faden and Beauchamp make similar claims on the topics of liability and responsibility in [3] (pp. 25–30).

5.3. Requirements Based on Manson and O’Neill’s Theory

This section is organised as follows. Section 5.3.1 includes a note on Manson and O’Neill’s two metaphors of information and communication. Section 5.3.2 outlines the reasons for Manson and O’Neill’s rejection of Faden and Beauchamp’s theory. Section 5.3.3 outlines the authors’ new theory of informed consent. Section 5.3.4 outlines the role of beneficence in the authors’ theory. Section 5.3.5 describes the role of competence in the theory. Finally, Section 5.3.6 includes a note on the authors’ consideration of trust and trustworthiness.

5.3.1. Two Metaphors of Information and Communication

Manson and O’Neill identify two metaphors of information and communication [14] (ch. 2–3). They argue that in the first, which they refer to as the conduit/container metaphor, the focus is exclusively on the information disclosed to the subject of consent, and in the second, which they refer to as the agency-based metaphor, the focus is on both what is disclosed verbally or otherwise, and on what is done, i.e., on how the disclosure is made.

5.3.2. Rejection of Faden and Beauchamp’s Theory

Manson and O’Neill reject Faden and Beauchamp’s autonomy-based theory based on the following claims/grounds:

- The theory corresponds with the conduit/container metaphor [14] (p. 69) but the agency-based metaphor provides deeper and more plausible justifications of informed consent.

- While the theory is based on the ethical principle of autonomy, it should not.

- The justification of medical and research practice need not place sole or excessive weight on the notion of a balance between individual autonomy and beneficence.

5.3.3. Manson and O’Neill’s Theory