Abstract

Recent reports indicate that over 85% of data breaches are still caused by a human element, of which healthcare is one of the organizations that cyber criminals target. As healthcare IT infrastructure is characterized by a human element, this study comprehensively examined the effect of psycho-socio-cultural and work factors on security behavior in a typical hospital. A quantitative approach was adopted where we collected responses from 212 healthcare staff through an online questionnaire survey. A broad range of constructs was selected from psychological, social, cultural perception, and work factors based on earlier review work. These were related with some security practices to assess the information security (IS) knowledge, attitude and behavior gaps among healthcare staff in a comprehensive way. The study revealed that work emergency (WE) has a positive correlation with IS conscious care behavior (ISCCB) risk. Conscientiousness also had a positive correlation with ISCCB risk, but agreeableness was negatively correlated with information security knowledge (ISK) risk and information security attitude (ISA) risk. Based on these findings, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation methods combined with cutting-edge technologies can be explored to discourage IS risks behaviors while enhancing conscious care security practice.

1. Introduction

Paperless or folder-less system is a common term used to denote the adoption of full electronic health records (EHR) systems used by hospitals in Ghana. In paperless systems, the hospitals do not use hard copy papers or folders to document and store patient care processes. Instead, all the patient activities at the healthcare facility (such as OPD visits, medical investigations, diagnosis and treatments, inpatient and outpatient documentation, referrals, and ordering of tests) are carried out in the EHR system [1,2]. The benefits of paperless systems cannot be overemphasized, as the systems improve the efficient management of patients’ information, reduce physical storage space for medical records, and improve clinical decision support [3,4,5].

In hindsight, cyber security incidents remain a threat to the use of these information systems [6] of which healthcare systems are among the most targeted systems. Several reasons account for this. Firstly, information security solutions have traditionally been focused on technical measures such as firewall configurations, demilitarize zone, intrusion detection and prevention systems, authentication, and authorizations in mitigating risks; however, the human aspect of IS management (also called the human firewall) has received less attention as an important factor in mitigating security issues [7,8]. Meanwhile, current dynamics in security issues cannot be resolved with only technical measures especially in an era where humans are considered the weakest link in the security chain [8,9,10]. Secondly, healthcare is most suitable for cyber criminals due to the urgency requirement by healthcare staff to access patients records. For instance, in a ransomware attack scenario of the healthcare sector, the authorities would be willing to pay the ransom for the timely access of patients records.

There is a broad range of human factors that contribute to security violations in healthcare. These include psychological, social, cultural, work factors and individual factors [11]. Security researchers often investigate these factors toward enhancing security practices; however, the assessments are not often comprehensively performed, leaving possible gaps of vulnerabilities in the human element. For instance, Anwar et al. investigated the significance of gender factors in security practice [12]. While this is essential, other variables, such as work factors, were not considered in the study. This means if findings in Anwar et al. were to be considered for enhancing security practice in a typical hospital, issues on the individual difference in terms of gender among healthcare staff will be detected and resolved. However, issues relating to other factors of the human element will not be covered. This may still leave a security gap among the staff’s security practice. This study contributed to bridging this gap, having adopted a comprehensive approach where a broad range of factors, including psychological, social, cultural, individual, and work factors were assessed in a comprehensive way.

In view of the above, the objectives of this study include the following:

- To comprehensively assess the effect of individual factors and perceptions, including psychological, social, and cultural aspects on IS knowledge, attitude and behavior among healthcare staff.

- To examine the effect of work factors (such as workload and work emergency) on cyber security knowledge, attitude, and the intended security conscious care behavior (ISCCB) of healthcare workers.

- To assess the effect of cyber security knowledge and attitude on the intended security conscious care behavior of healthcare staff.

Factors found to have significant risks on conscious care security practices can be discouraged with extrinsic motivation (motivations based on external factors, e.g., financial or punishment) [13,14,15] and intrinsic motivations (incentives that stem out of one’s self) [16,17] while promoting factors that have a positive impact on IS security practice.

The remaining part of the paper is organized to include the theoretical background and hypotheses. In this section, related theories that were used in similar studies have been reviewed. Subsequently, the theoretical model and hypotheses were developed. This section is followed by the study approach and the method section, which explained how the study was conducted. The results were then described in the Results section. Finally, the results were then discussed and concluded in the Conclusions section.

2. Related Work and Theoretical Background in Security Behavior within Healthcare

2.1. Related Work

Healthcare staff plays a vital role in the space of information security as they are required to abide by end-user security policies amidst their core duties [18,19]. Failure to do so can lead to vulnerabilities that can be exploited to cause internal or external breaches. Therefore, in efforts to improve upon the staff’s conscious care behavior, it is imperative to identify and assess a broad range of factors that affect the staff’s security behavior to enable management to “push” the right incentive “buttons” toward improving conscious care security practices. Information security conscious care behavior refers to the healthcare workers’ active compliance with the information security policies and ethics in order to safeguard the confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) of the organizational assets [11,20]. Having conducted a study into security requirements [21], some compliance measures were identified and adopted in this work. These include internet use, email use, social media use, password management, incident reporting, information handling, and mobile computing. These measures were considered because they are more prone to security violations by the humans [9,11].

Prior to this empirical study, various reviews pointed out theory of plan behavior (TPB), protection motivation theory (PMT), health belief model (HBM), social control (SC), technology acceptance model (TAM) and personality traits as some of the psychological, social, and cultural factors that are used to investigate information security practices [6,11,22]. While these studies presented knowledge on the overview of all the necessary theories for incentive factors, these methods were not practically assessed in a holistic fashion but provided a foundation for empirical assessments. Fernandez-Aleman et al. evaluated the security practice of healthcare staff in an actual healthcare facility [23]. The study tried to cover this gap, and the authors reviewed IS security governance tools such as standards, guidelines, and best practices and used this information to develop a questionnaire instrument. The instrument was then used to conduct a survey to which 180 healthcare staff responded. The study found weak passwords among 62.2% of the staff, half of the respondents failed to protect unauthorized access to patients information, and 57% did not know the procedure to report security violations. A related study also assessed healthcare staff security practices with a total of 554 completed questionnaires to understand the security behavior of healthcare workers in a real hospital. The study also identified significant security gaps among the hospital staff, including the practice of sharing computers and passwords [24]. While these studies [23,24] pointed out that the staff of the respective facilities needed both preventive and corrective measures to prevent them from causing security violations, the studies did not pinpoint the exact factors influencing this IS security misbehavior.

Comprehensive factors need to be examined among healthcare workers in relation to their cyber security behavior. That will give a sense of direction as to how to improve upon the ISCCB of the workers. To this end, Anwar et al. conducted a study to find out if gender differences play a role in cyber security behavior. Psychological and social factors of PMT and TPB were adopted as mediating variables [12]. The findings revealed that gender has a significant effect on SE, prior experience, and computer skills. This was also the right step toward a holistic approach; however, other factors relating to knowledge and attitude toward IS security practice were not examined. Additionally, work factors such as workload and work emergency in healthcare were not considered; meanwhile, all these are important factors that can have a significant effect on IS conscious care behavior [11,19].

Based on these gaps, we empirically assessed the ISCCB in a holistic way by considering factors from PMT, TPB, HBM, SC, personality traits, and work factors such as workload, work emergency, work experience, and IS experience. Additionally, security practices relating to email use, internet use, incident reporting, mobile computing, password management, and information handling [9,11] were adopted in this work. Healthcare workers are mostly confronted with work emergencies and workload issues in their daily duties in healthcare, and this can have significant effect on cyber security practice. To the best of our knowledge, none of these previous studies empirically and comprehensively assessed a broad range of the effect of various factors on cyber security practice in healthcare. The theoretical background and hypothesis of our study has been presented in Section 2.2.

2.2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Information security (IS) risk behavior is a security practice of insiders that has the propensity to violate and compromise organizational security measures [20]. For a healthcare facility to enjoy the benefits associated with the use of information systems, it needs to work to reduce these behavioral risks by improving upon the staff’s ISCCB. Security practices are rules that the leaders lay down in healthcare facilities requiring the healthcare staff to abide by these in order to enhance the CIA of the healthcare systems and assets. The compliance can be influenced by the knowledge, attitude, and behavior (KAB) of the healthcare staff, among other factors. Adapting from PMT, TPB, HBM, SC, personality traits, and work factors, we investigated broad range of constructs, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study constructs and their theoretical origin.

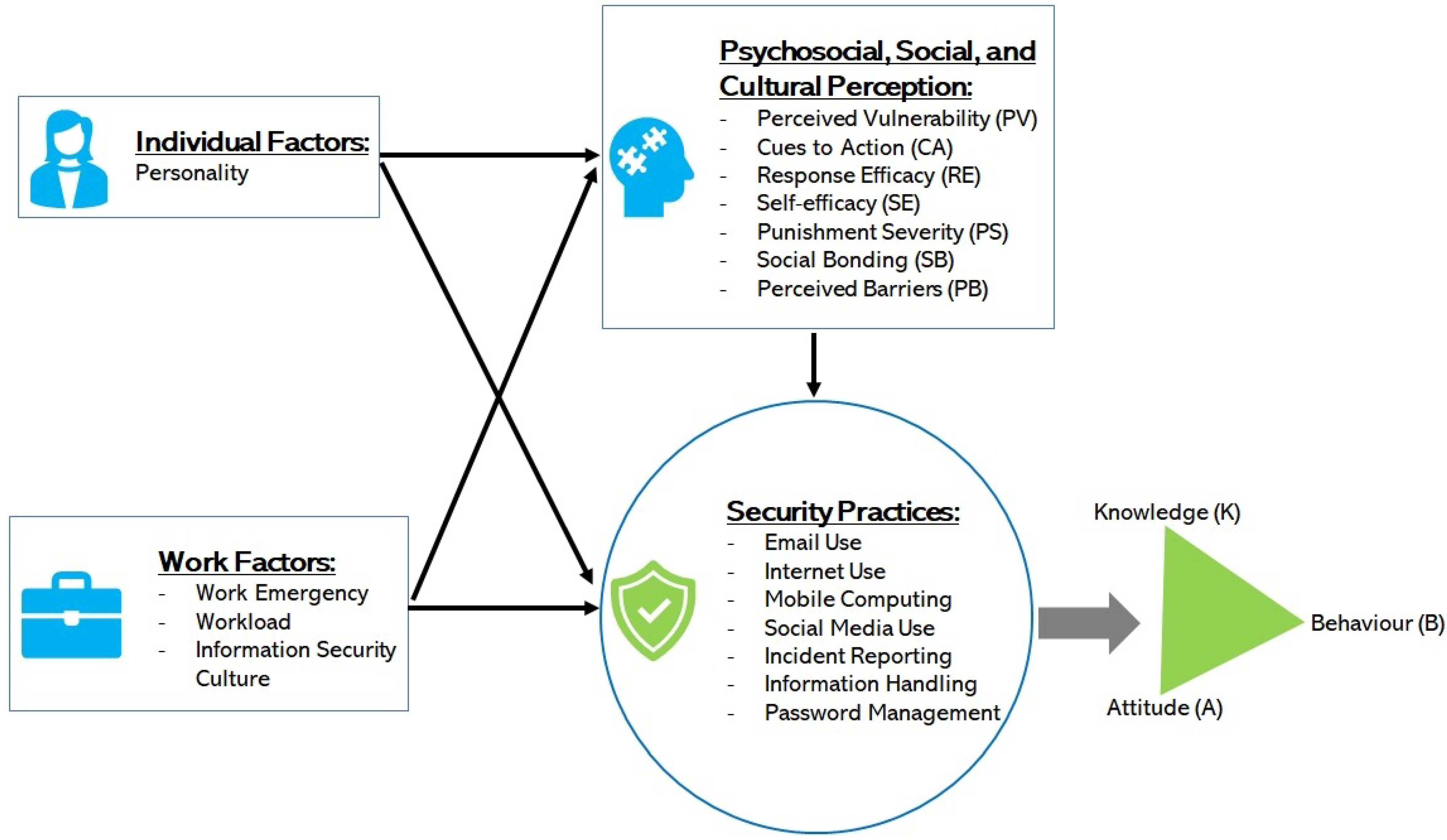

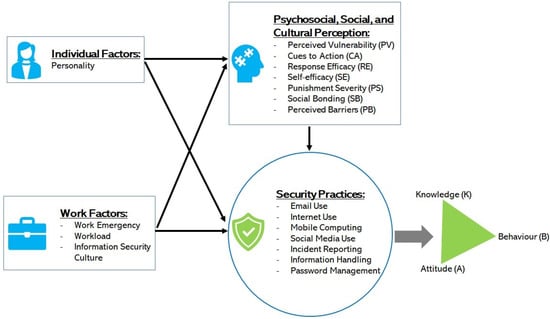

These factors were related to the security practice measures as shown in Figure 1, having associated the measures with both the IS risk of perception as independent variables and the risk of KAB as dependant variables.

Figure 1.

The study model.

This approach is more comprehensive and covers healthcare staff behavioral factors that commonly have an effect on IS security [6,11,19] in healthcare. Although other factors such as organizational factors and leadership play a significant role in IS, our scope and focus are on factors that relate to the healthcare staff in this work.

2.2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior and Knowledge, Attitude and Behavior

Ajzen et al. proposed the theory of planned behavior (TPB), which explains the effect of attitude, subjective norms, and behavioral control on the behavior of individuals [20,25]. As Safa et al. [20] and Parsons et al. [9] explained, attitude relates to a person’s beliefs and feelings, which are directly influenced by what they know (K) of the IS measures. Both attitude and knowledge can have a direct and indirect effect on the individual’s security practice. Therefore, the ISCCB is a function of the knowledge and attitude toward the security policies that healthcare management keeps in place. Information security conscious care behavior is actually the level of compliance with the IS policies that healthcare management keeps in place. The KAB of the healthcare staff tends to be risky if the compliance level tends to compromise CIA of healthcare systems and assets. Healthcare staff’s knowledge of the security policies also has a direct effect on their attitude. The knowledge is often acquired through their experience, observations, training and awareness [26]. The staff’s attitude toward IS policies refers to their positive or negative intentions toward a specific behavior. It is a learned tendency to behave in a particular way toward a security policy [27]. As the knowledge of a particular policy influences attitude, the relative behavior in that context is adjusted accordingly. Attitude has explicit and implicit dimensions. In the explicit attitude, the individuals are aware of the effect of their behavior while in the implicit attitude, the individuals are not conscious of the effect of their behavior [28]. Various studies showed significant correlations between these constructs in the context of IS behavior [9,29].

In this study, we hypothesize that

- H1: Low level of staff’s ISK risks has a positive correlation with ISCCB risk.

- H2: Low level of staff’s ISA risks has a positive correlation with ISCCB risk.

Furthermore, the healthcare environment is associated with work emergencies, such as accident cases and other life-threatening health conditions [11,30,31]. These cases mostly require urgent and timely interventions from the healthcare professionals without which the patient’s condition could worsen. Therefore, it is important that hospitals have dedicated units or departments for emergency cases equipped with resources to provide timely interventions for emergency patients. Additionally, a high workload on healthcare personnel has become a huge burden on the few staff which is threatening the effectiveness of health delivery [32]. This has various reasons, including funding gaps and an increase in the patients-to-clinicians ratio [6,33]. The spontaneous question is, how do healthcare workers observe good security practice amidst work emergencies and high workloads? To this end, we hypothesize that

- H3a: Work emergency (WE) is a positive predictor of high risk in the hospital staff’s self-reported ISCCB.

- H3b: WE is a positive predictor of high risk in the hospital staff’s self-reported ISK.

- H3c: WE is a positive predictor of high risk in the hospital staff’s self-reported ISA.

- H3d: Workload (WL) is a positive predictor of high risk in the hospital staff’s self-reported ISCCB.

- H3e: Workload (WL) is a positive predictor of high risk in the hospital staff’s self-reported ISA.

- H3f: Workload (WL) is a positive predictor of high risk in the hospital staff’s self-reported ISK.

- H3g: High risk of IS culture (ISC) is a positive predictor of high risk in the hospital staff’s self-reported ISCCB.

- H3h: High risk of IS culture (ISC) is a positive predictor of high risk in the hospital staff’s self-reported ISK.

- H3i: High risk of IS culture (ISC) is a positive predictor of high risk in the hospital staff’s self-reported ISA.

2.2.2. Personality, Knowledge, Attitude and Behavior (KAB)

Personality traits are inherent characteristics of individuals which are developed from biological and environmental factors [34,35]. It is a psychological attribute that has an influence on security practice [36]. Others have the view that personality traits are more stable over time when compared with attitude construct [11,36,37,38]. Essentially, there are five common personality traits as outlined and defined below [36,37,38]:

- Agreeableness is a measure of an individual’s tendencies with respect to social harmony. This trait reflects how well the individual gets along with others, how cooperative or sceptical they are, and how they might interact within a team.

- Conscientiousness is a measure of how careful, deliberate, self-disciplined, and organized an individual is. Conscientiousness is often predictive of employee productivity, particularly in lower-level positions.

- Extraversion is a measure of how sociable, outgoing, and energetic an individual is. Individuals who score lower on the extraversion scale are considered to be more introverted, or more deliberate, quiet, low-key, and independent. Some types of positions are better suited for individuals who fall on one side of the spectrum or the other.

- Openness measures the extent to which an individual is imaginative and creative, as opposed to down-to-earth and conventional.

- Neuroticism or stress tolerance measures the ways in which individuals react to stress.

In measuring the security practice of healthcare staff, we hypothesize that:

- H4a: The healthcare staff personality trait of agreeableness has a negative significant correlation with information security knowledge risk.

- H4b: The healthcare staff personality trait of agreeableness has a negative significant correlation with information security attitude risk.

- H4c: The healthcare staff personality trait of agreeableness has a negative significant correlation with ISCCB risk.

- H4d: The healthcare staff personality trait of conscientiousness has a negative significant correlation with information security knowledge risk.

- H4e: The healthcare staff personality trait of conscientiousness has a negative significant correlation with information security attitude risk.

- H4f: The healthcare staff personality trait of conscientiousness has a negative significant correlation with ISCCB risk.

- H4g: The healthcare staff personality trait of openness has a negative significant correlation with information security knowledge risk.

- H4h: The healthcare staff personality trait of openness has a negative significant correlation with information security attitude risk.

- H4i: The healthcare staff personality trait of openness has a negative significant correlation with ISCCB risk.

- H4j: The healthcare staff personality trait of neuroticism has a positive significant correlation with information security knowledge risk.

- H4k: The healthcare staff personality trait of neuroticism has a positive significant correlation with information security attitude risk.

- H4l: The healthcare staff personality trait of neuroticism has a positive significant correlation with ISCCB risk.

- H4j: The healthcare staff personality trait of extroversion has a negative significant correlation with information security knowledge risk.

- H4k: The healthcare staff personality trait of extroversion has a negative significant correlation with information security attitude risk.

- H4l: The healthcare staff personality trait of extroversion has a negative significant correlation with ISCCB risk.

2.2.3. Perception

Psychological, social, and cultural perception in relation to information security effects has largely been considered very important in assessing human factors in IS [12,13,20]. Therefore, we included perceived vulnerability risk (PV), perceived cues to action risk (CA), response efficacy risk (RE), perceived self-efficacy (SE), punishment severity risk (PS), SC, or informal social control risk (SB) and perceived barrier risk (PB). These were drawn from HBM [39], PMT [12,40] and SC [41]. These variables were in line with the study objectives and were formed from various psychological, social, and cultural theories. In this regard, we hypothesized that:

- H5a: High WE is a predictor of high risk of PV.

- H5b: High WE is a predictor of high risk of CA.

- H5c: High WE is a predictor of high risk of RE.

- H5e: High WE is a predictor of high risk of SE.

- H5f: High WE is a predictor of high risk of PS.

- H5g: High WE is a predictor of high risk of SB.

- H5h: High WE is a predictor of high risk of PB.

- H5a: High WL is a predictor of high risk of PV.

- H5b: High WL is a predictor of high risk of CA.

- H5c: High WL is a predictor of high risk of RE.

- H5e: High WL is a predictor of high risk of SE.

- H5f: High WL is a predictor of high risk of PS.

- H5g: High WL is a predictor of high risk of SB.

- H5h: High WL is a predictor of high risk of PB.

- H5i: Poor IS culture is a predictor of high risk of PV.

- H5j: Poor IS culture is a predictor of high risk of CA.

- H5k: Poor IS culture is a predictor of high risk of RE.

- H5l: Poor IS culture is a predictor of high risk of SE.

- H5m: Poor IS culture is a predictor of high risk of PS.

- H5n: Poor IS culture is a predictor of high risk of SB.

- H5o: Poor IS culture is a predictor of high risk of PB.

- H5Hi: Poor IS culture is a predictor of high risk of PB.

With regard to personality traits and perception, we opined that

- H5: Extroversion is a predictor of the risk of CA (H5a), RE (H5b), SE (H5c), PS (H5e), SB (H5f), ISC (H5g), and PB (H5h).

- H6: Agreeableness is a predictor of the risk of CA (H6a), RE (H6b), SE (H6c), PS (H6e), SB (H6f), ISC (H6g), and PB (H6h).

- H7: Conscientiousness is a predictor of the risk of CA (H7a), RE (H7b), SE (H7c), PS (H7e), SB (H7f), ISC (H7g), and PB (H7h).

- H8: Openness is a predictor of the risk of CA (H8a), RE (H8b), SE (H8c), PS (H8e), SB (H8f), ISC (H8g), and PB (H8h).

- H9: Neuroticism is a predictor of the risk of CA (H9a), RE (H9b), SE (H9c), PS (H9e), SB (H9f), ISC (H9g), and PB (H9h).

3. Our Approach

3.1. Participants, Study Approval and Consent, and Data Collection

Convenience sampling was adopted in the recruitment process of the hospitals and their participants. First, healthcare facilities that adopted “folder-less” systems were invited to join the survey. Some health facilities in Ghana volunteered to take part in the study. Based on ethical, privacy, and security reasons, the names and locations of these facilities have not been mentioned in this paper, but ethical clearance was duly obtained in Ghana. Following that, research coordinators were appointed and liaised with the hospitals’ management teams (i.e., the administrators and medical directors). The healthcare staff who already formed social network groups were invited to to participate in the online survey. The online questionnaire link was therefore shared on the network, and participants who consented to the study subsequently responded to the questionnaire. Due to the high cost of the internet data bundles in Ghana, the participants were to fill out the questionnaire and receive a reimbursement of their internet data of an estimated amount of GHS 10.00 (which is about 1.67 United States dollars). There was a consent form to which each participant agreed prior to taking part in the survey. The survey started in March 2021 and was closed in May 2021 of which a total of 233 (female = 114, male = 119) delivered their responses; however, 212 responses were assessed to be valid responses based on attention checkers that were placed in the questionnaire instrument [9,42,43,44,45,46].

3.2. Instrument and Measurements

This statistical survey was conducted based on earlier studies [6,11,19,47], where comprehensive security practices were identified [11,47,48] and psychological, social and cultural factors [11,19] were also identified. The questionnaire instrument was developed with 44 security practice measures to measure the KAB risk in relation to other factors of the healthcare staff [48]. The structure for the questionnaire items is shown in Appendix A. The questionnaire items were developed to measure the psychological, social and cultural perceptions of the end users in the hospital. Seven questions also covered the staff demographics, and two items each were developed to measure the workload, work emergency, and personality constructs of the healthcare staff. The brief version of personality items was used [46], because the healthcare workers do not have much time to answer the entire 240 items of the long personality scale. In addition, as the main focus of this study is not about personality, the short version has been assessed to meet the scale requirements [12,23,46,48]. The entire instrument for this study was pretested by combining conventional pretesting [49,50,51] and a behavior coding method [52,53]. The issues with the questionnaire were then identified to include unclear questions, the insignificant differences between questions, problematic questions, inadequate questions, complex terms, and there being too many. A total of 50 questionnaire items were identified to have problems after conducting the pretesting with a total of 36 respondents in behavior coding and 21 respondents in conventional pretesting. The synergy of the pretesting was necessary to ensure a thorough assessment of the questionnaire for effective correction prior to actual use. Therefore, the identified errors were corrected prior to actually using of the instrument.

Three attention checkers were introduced in the study and required the respondents to select specific answers. Respondents who answered at least two of these checkers wrongly suggest that they did not really pay attention while responding to the instrument. This is one of the common methods used in surveys, and it does not affect the validity of the instrument [9,42,43,44,45,46].

3.3. Statistical Analyses

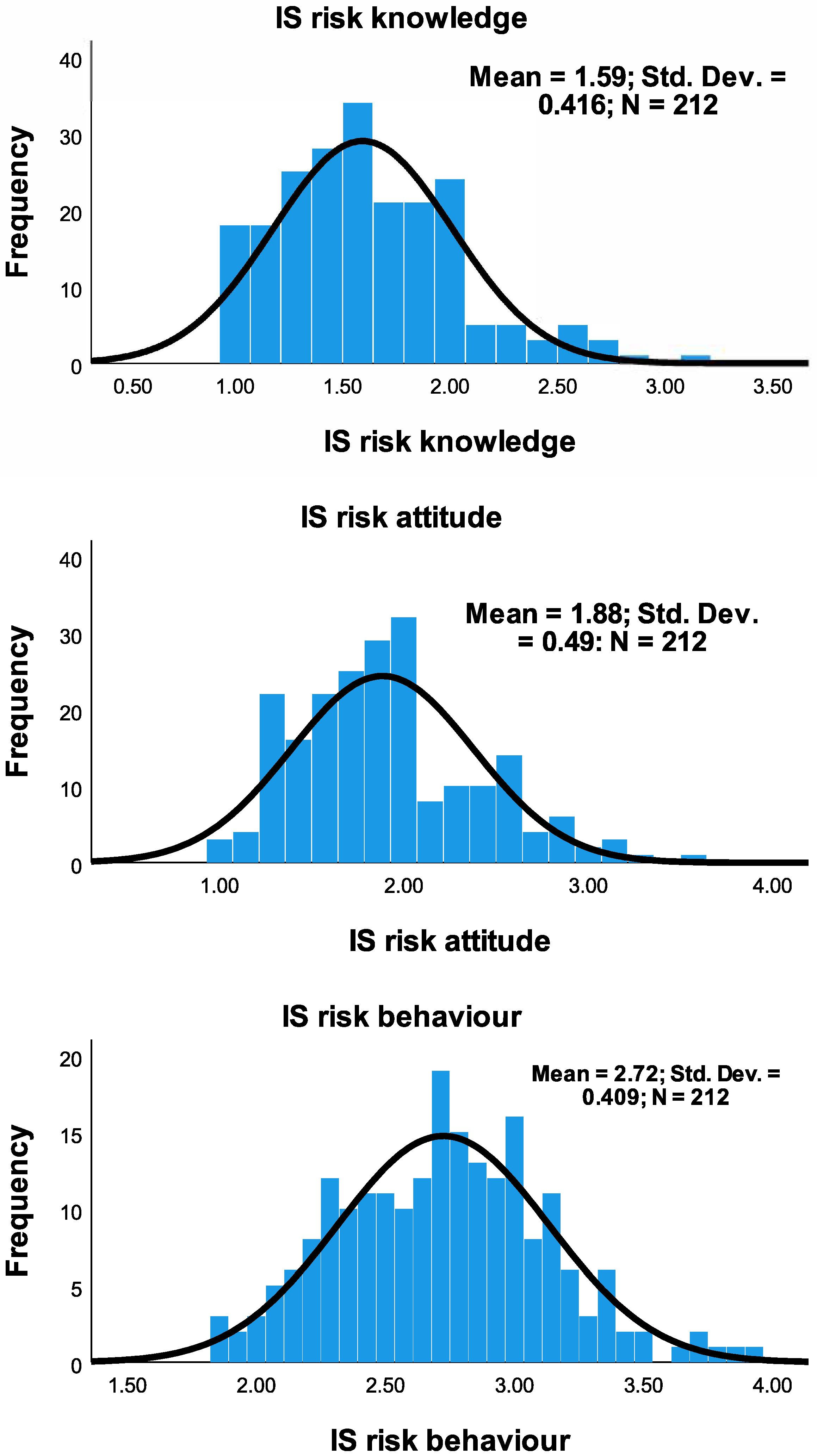

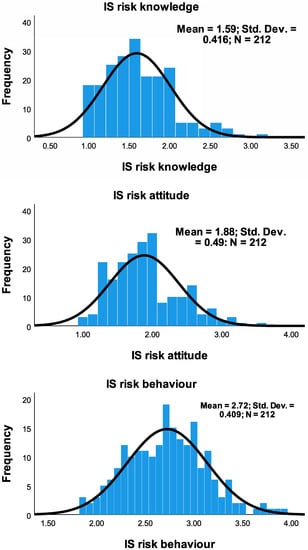

Pearson’s correlation, correlation, descriptive statistics, and statistical hypothesis testing methods were used in the analysis and tests. The choice was based on the specific characteristics of the data set involved. For instance, aside from the IS risk behavior, ISK risk and ISA risk were slightly skewed, as shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. Therefore, Pearson’s correlation was adopted, as the distribution was approximately normal [29,54]. Furthermore, t-test and Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric one-way ANOVA methods were adopted based on the nature of the dataset in the test scenario. Levene’s tests were performed, when required, to determine the variation significance among the test groups [23]. The IBM SPSS statistical package version 7 was used for the data analysis. The reliability of the constructs was measured using Cronbach’s alpha. Reliability is the extent to which the items are measuring the same underlying construct [55]. The coefficient of the Cronbach’s alpha value usually ranges between 0 and 1, but it is mostly expected to be above 0.6. However, these values are dependent on the number of items in the scale [56,57,58,59,60]. If the number of items in a scale is 10 or more, it is reasonable to record the coefficient of Cronbach’s alpha to be 0.6 or higher (as shown in Table 3) [56,57]; otherwise, it is normal to record the Cronbach’s alpha values to be lower with an optimal range of 0.2 to 0.4 [9,42,43,44,45,46].

Figure 2.

Distribution of knowledge, attitude and behavior of security practice.

Table 2.

Skewness of IS security practice.

Table 3.

Rule of Thumb on Cronbach’s Alpha [56,57].

4. Results

This section presents the findings of the analysis. As shown in Table 4, the reliability statistics of the Cronbach’s alpha of all the constructs were within the range of moderate and good strength. Those scales in which the number of items were less than 10 also fell within the optimal range of 0.2 to 0.4 alpha coefficient. To this end, the results of the various factors are presented in the subsequent subsections.

Table 4.

Reliability statistics.

The normality of the distribution of the responses was also checked to guide in choosing methods for the analysis. Absolute skewness of less than 0.5 suggests that the distribution is pretty symmetric, but if the skewness is between 0.5 and 1, then it is slightly skewed [61]. Skewness that is greater than 1 or less than −1 means that it is highly skewed. Additionally, a perfect normal distribution has a kurtosis of zero. Considering means of the distributions in Figure 2 (1.59) of ISK risk and in Figure 2 (1.88) of ISA risk of the responses, more healthcare workers tend to have less risky ISA practice and ISA risk; however, the security practice pattern in the ISCCB risk showed fairly uniform distribution, suggesting that the distribution of healthcare workers in terms of their risk behavior is uniform in both high-risk and low-risk regions.

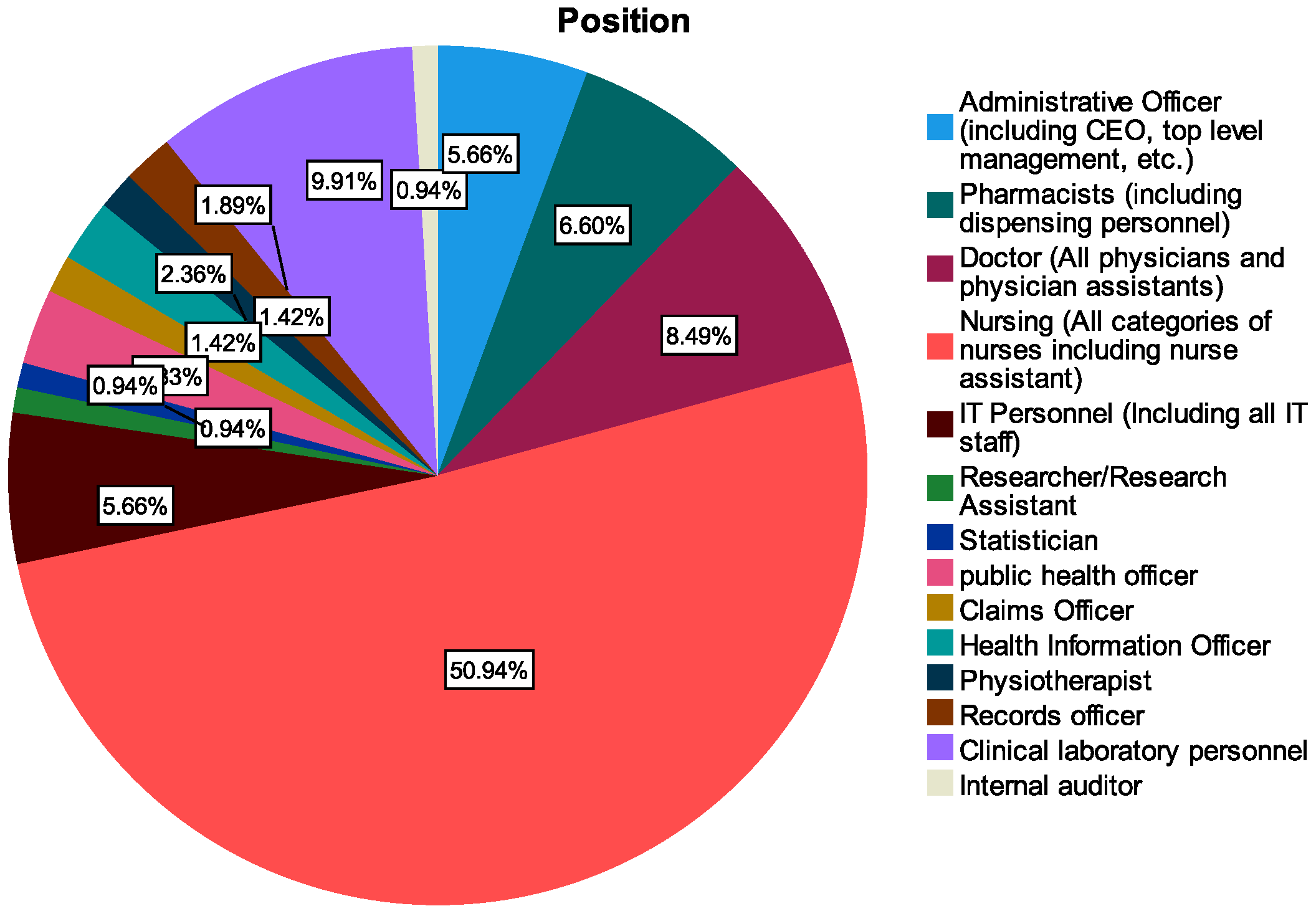

4.1. Nature of the Respondents

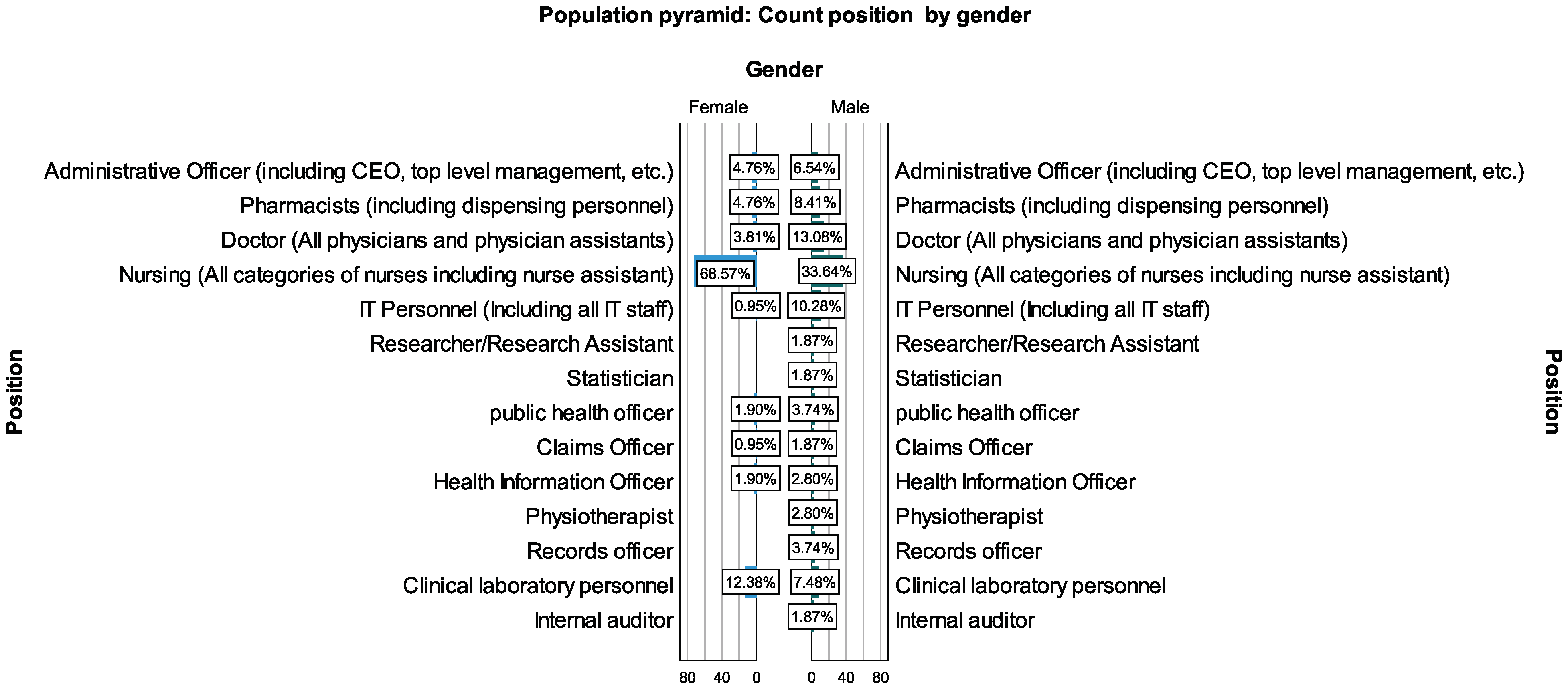

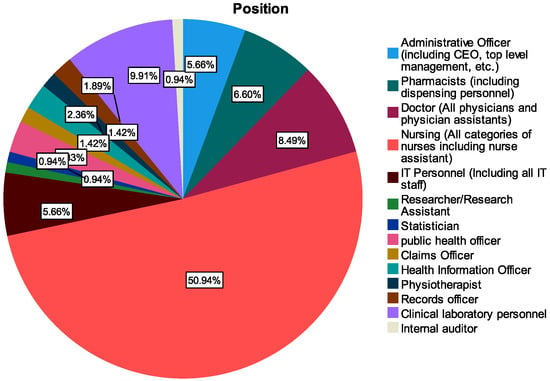

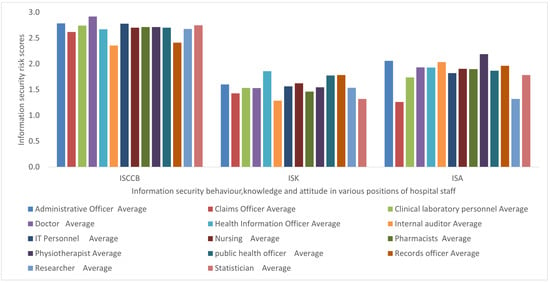

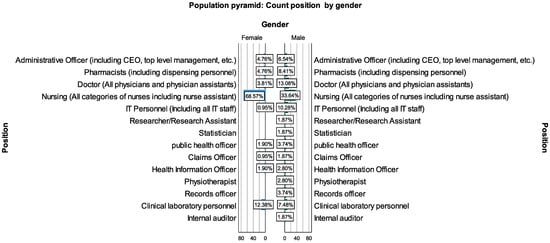

With reference to Figure 3 and Table 5, the participants of the study included various groups such as administrative officers (including CEO, top-level management, etc.), pharmacists (including dispensing personnel), doctors (all physicians and physician assistants), nursing (all categories of nurses including nurse assistant), IT personnel (including all IT staff), researcher/research assistant, and statisticians. Other groups who also took part in the study were public health officers, claims officer, health information officers, physiotherapists, records officers, clinical laboratory personnel, and internal auditor. These were categorized into operational staff (doctors, nurses, IT staff, equipment engineers, etc.), managers and supervisors and those in the executive category (including CEO, director, top-level management, etc.).

Figure 3.

Role categories of respondents.

Table 5.

Participants’ demographics.

Two hundred and twelve valid participants took part in the analysis, with on average the same proportion of representation of males (50.5%) and females (49.5%), as shown in Table 5. Out of this, nurses constituted the majority of the group (50.9%) followed by clinical laboratory personnel (9.9%) and doctors (8.5%). Additionally, the young age group constituted the majority of between 21 and 40 years, as shown in Figure 4. In terms of gender among the hospital roles, female nurses were more prevalent and constituted about 68.7% of the female working population followed by 33.34% of male nurses among the male healthcare workers, as shown in Figure 5. Comparatively, few of the workers (8.9%) had less than one year of healthcare experience, as a higher proportion of the workers (39.15%) had between 1 and 5 years of experience and beyond, as shown in Table 5.

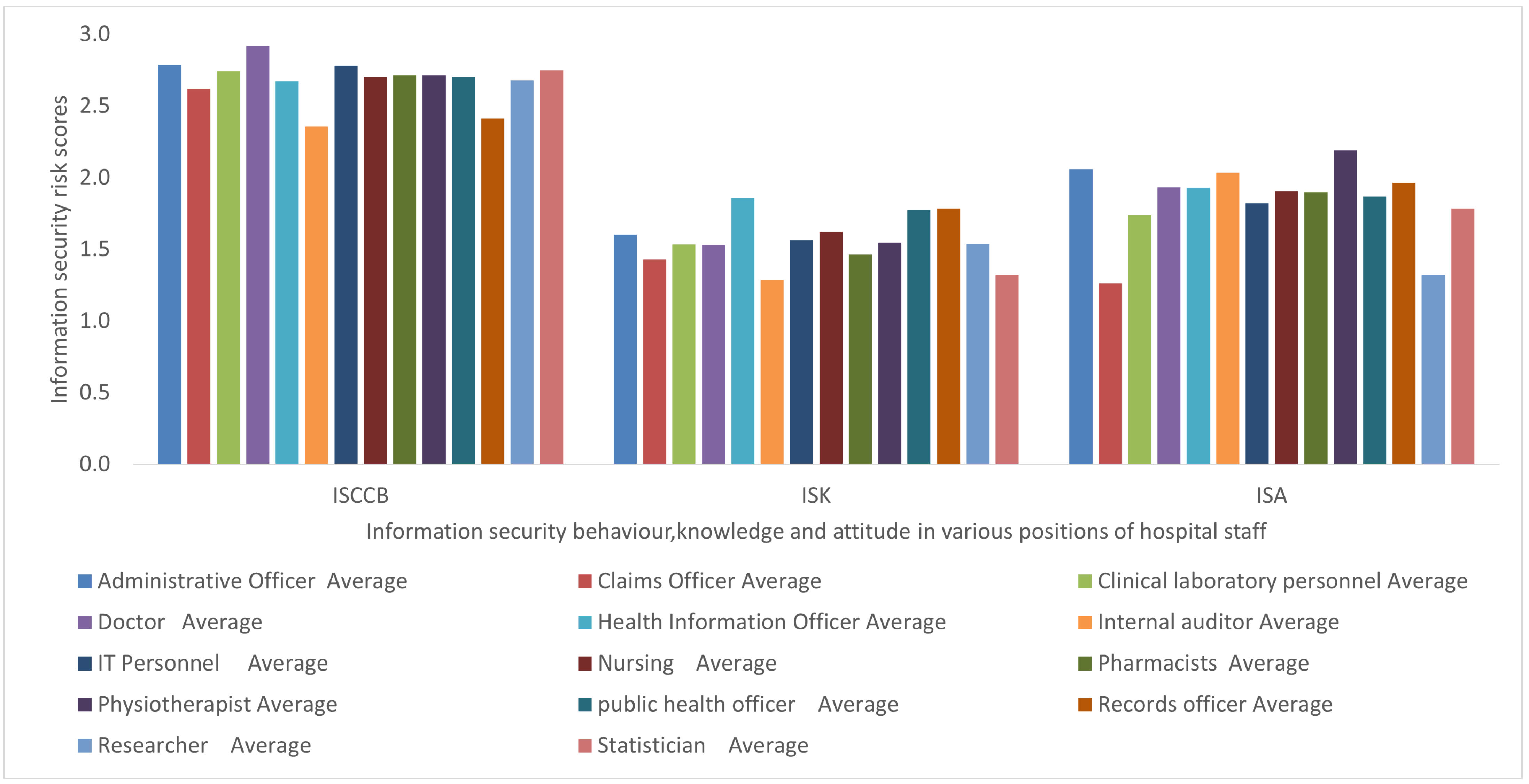

Figure 4.

Comparison of KAB security practice risk among healthcare staff.

Figure 5.

Position distribution by gender.

From the total number of 42 questionnaire items which measured the intended security practice in terms of KAB risks, the ISK risk was averagely lower, which was followed by ISA risk; however, ISCCB risk was comparatively higher, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 2 and Table 2 showed the distribution of responses of the intended security practice in terms of KAB. The number of respondents (frequency) was distributed over the IS security risk intention practices from low (1 = Agree) to high-risk IS practice (5 = Disagree). Knowledge—and attitude—related risks were positively skewed, while behavior risks showed uniform distribution.

4.2. Work Factors in Relation to Security Risk Knowledge, Attitude and Behavior (KAB)

In assessing the correlation of work factors (workload and work emergency), as shown in Table 6, ISCCB risk has a a very weak, positive, significant correlation with work emergency (r = 0.195, p = 0.01), which in part supports our Hypothesis H3d. ISCCB risk and ISK risk also have a positive weak correlation (r = 0.287, p = 0.01) as proposed in Hypothesis H1. Additionally, ISCCB and ISA risk were moderately and positively correlated (r = 0.380, p = 0.01), as indicated in Hypothesis H2. However, the workload was insignificantly correlated ( p = 0.005, and r = 0.011) with all of the KAB risk variables.

Table 6.

Correlations among work load, work emergency, security risk of knowledge, attitude, and behavior.

4.3. Correlations between Personality Traits and Security Risk of KAB

In analyzing personality traits and the security risks of KAB, agreeableness has a significant negative and low weak correlation with both ISK risk (−0.166) and ISA risk (−0.140) at a p-value of 0.05 stated in hypotheses H4a and H4b, respectively. However, it had no significant correlation with IS risk behavior, as shown in Table 7. Therefore, staff who have an agreeable personality may have low-risk security practices in terms of knowledge and attitude. However, conscientiousness and ISCCB showed a positive and weak significant correlation (0.157) at a p-value of 0.05, suggesting that healthcare workers with conscientiousness traits may tend to be in the high-risk category of IS risk behavior, as suggested in Hypothesis H4f.

Table 7.

Correlations between personality traits, and security practice (KAB).

4.4. Correlations between Perception and Personality Traits

As shown in Table 8, healthcare staff with agreeable traits have significant positive and weak correlation (r = 0.163, p-value = 0.05) with SE risk (H6c) but showed negative and weak correlation (r = 0.147, p-value = 0.05) with PS risk (H6e). In addition, cues to action risk showed a positive correlation with conscientiousness (r = 0.159, p-value = 0.05) as stated in Hypothesis (H7a) and neuroticism (r = 0.152, p-value = 0.05) (H9a). Meanwhile, openness also has a significant weak and negative correlation with social bonding (r = −0.170, p-value = 0.05), and this supports Hypothesis (H8f).

Table 8.

Correlations between perception and personality.

4.5. Perception in Relation to Work Factors

The analysis of the psychological, social, and cultural perceptions in relation to work factors such as workload, hospital security culture, and work emergency are shown in Table 9. The perception variables have an insignificant correlation with work emergency and workload. However, RE and PS risks, respectively, have a significant negative and weak correlation with the culture of hospital IS (r = −0.182, p-value = 0.05 ) and (r = −0.177, p-value = 0.01), as stated in hypotheses H5K and H5m, respectively.

Table 9.

Correlations between perception and work factors.

4.6. Statistical Tests of IS Risk Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior (KAB) with Categorical Variables

Statistical tests were conducted to assess the distribution of IS risk KAB across categorical variables, including gender, position levels, hospital IS experience, age group, and healthcare work experience. T-test was used for the hypothesis between gender and KAB risk variables, since it is normally used for testing two-level categorical variables with continuous variables. Additionally, Levene’s test did not show significant variances among the group’s population of the three respective KAB variables (r = 0.412, r = 0.406, r = 0.632) at a p-value of 0.05.

Furthermore, Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric one-way ANOVA was used in the hypothesis testing with the remaining variables such as position levels, hospital IS experience, age group, and healthcare work experience as they were more than two levels. Aside from work experience in healthcare, the statistical tests show that the distribution of IS risk of KAB is the same across all variables. With regard to experience in healthcare, the distribution of ISK and ISA risks was uniform across all healthcare experience groups, but the distribution of IS risk behavior across all work experience groups did not show uniform distribution with a significance level of (r = −0.00, p-value = 0.05), as shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Kruskal Wallis non parametric one way ANOVA with work experience and KAB.

Therefore, the post hoc pairwise test was analyzed to determine the distribution among the groups. The results indicate that there are significant differences (p-value = 0.05) of IS security behavior among various groups such as 7 (>25 years)–2 (1 to 5 years ) = (0.019), 7 (>25)–4 (11 to 15) = 0.013, 7 (>25)–3 (6 to 10) = 0.003, 7 (>25)–5 (16 to 20 years) = 0.001, 7 (>25)–6 (21–25 years) = 0.002 and others, as shown in Table 11 at significance level of 0.05 or less.

Table 11.

Post-hoc pairwise test with null hypothesis: Sample 1 and sample 2 distribution are the same.

5. Discussion

This study assessed various factors that affect sound security and privacy behavior among healthcare workers. The purpose was to assess gaps in their security practice and to find out if some of the factors had negative effects on the security practices. This would provide guidance for the choice of better mitigation strategies such as incentive measures to improve security practices. This study is centered on the human element, which is one of the three pillars of effective cyber security practice processes, technology and the people [62,63].

5.1. Principal Findings

The study was characterized by an almost equal proportion of male and female participants and was also dominated with nurses, who represented more than half (50.9%) of the total participants. In terms of distribution of the risk of security practice in the aspect of KAB, there was generally uniform distribution of the behavior risk, while ISK and ISA risks slightly skewed to the positive side, as shown in Figure 2. The results further showed a significant positive and weak correlation between ISK risk, ISA, work emergency, and ISCCB, as shown in Table 6 and Table 12. Additionally, while agreeableness had a negative and weak correlation with ISK and ISA, conscientiousness had a significant positive and weak correlation with ISCCB, as shown in Table 9 and Table 12. Essentially, Table 12 consists of the gist of the study results that showed significant correlations. These are further discussed in the subsequent subsections.

Table 12.

Summary of results.

As shown in Table 12, aside from the results values of Hypothesis H1a and H2 that have the correlation strength of moderate, the remaining results fall within the low or weak category of the correlation strength [64]. This suggests that with low strength in correlation, because the findings are statistically significant, the chances or the probability of their predictions are merely low, while the findings with the modest strength have a higher prediction probability. This suggests that the findings are still valid, as the results are significant and have the probability of prediction.

5.2. Risk of Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior (KABs)

The healthcare workers are required to observe security practice in a bit to enhance the systems’ CIA. The most common practices include password management, incident reporting, email use, social media use, mobile computing, and information handling [9,65], as shown in Figure 1. Mostly, these security practices are observed based on the healthcare facility’s security policies, which are literally the “law” to be followed by the healthcare workers in order to avoid security breaches. With regard to the model, healthcare workers are characterized by their personalities. In addition to that, they are associated with work factors, which may contribute to their cyber security perception. How all these variables correlate and affect the KAB of healthcare staff is the object of interest of this study. From our assessment, ISCCB risk positively correlated with both ISK risk and ISA risk, with the correlation strength being low and moderate, as shown in Table 12. Additionally, ISK and ISA have a modest positive significant correlation. This could mean that better ISK and ISA risks could significantly influence better ISCCB, which supports our hypotheses (H1a, H1 and H2). Related studies by [9,65] found a similar pattern.The comparative advantage here is the comprehensive approach in which results from various constructs were obtained [6]. For instance, healthcare is often characterized with work emergency, which was included in the study based on our comprehensive approach. Interestingly, the work emergency correlated with the risk of security behavior, and management can therefore use various state-of-the-arts methods to influence the ISCCB of healthcare workers.

Additionally, the findings also showed a significant positive weak correlation between work emergency and ISCCB, as stated in Hypothesis H3d, but not workload. It is possible that workload does not create urgency and does not interfere with the healthcare security practice as compared to work emergency [66,67,68,69,70,71]. In a healthcare emergency situation, the medical staff’s main goal is to save the patient’s life or prevent the patient’s condition from worsening. However, in some care situations, observing good information security practice might be least prioritized by the healthcare staff [70,71], and they may tend to circumvent some of the security and privacy measures to perform their core healthcare functions. As healthcare emergency positively correlated with the ISCCB risk, it means that during emergency situations, the risk of complying with security measures is high. To this end, incentive measures including usable security measures are required to promote sound security practice. Otherwise, with all the urgency in healthcare, the severity of the impact of security breaches in healthcare would be much higher [72].

Individual differences were also assessed with the KAB variables. The findings showed that agreeableness has a significant negative weak correlation with ISK risk and ISA risk but not ISCCB. However, healthcare workers with a high conscientiousness trait tend to have a significant positive weak correlation with the risk of ISCCB but not ISK and ISA risks, as shown in Table 12. With a negative correlation, between the risks of ISK and agreeableness as well as ISA and agreeableness, it implies that the risk of cyber security practice of knowledge and attitude tend to reduce with healthcare workers who have higher scores with agreeable personalities and vice versa. This could be the case because healthcare staff with a high score of agreeableness characteristics tend to easily agree with cyber security education and training, enabling them to have low risk in ISK and ISA. This finding is in line with previous studies [73,74]. Conversely, the healthcare workers with a high risk score of conscientiousness showed higher ISCCB risk, which contrasts our hypothesis and previous studies [73,74]. Our assumption was that a higher score of conscientiousness would have translated into less risk of ISCCB. It is possible that the workers with a high risk score of conscientiousness equally have high self-esteem, giving them false confidence of conscious care security practices [75].

5.3. Personality and Psycho-Socio-Cultural Security Behavior

Healthcare workers (just like any person) are complex in nature, and this is exhibited in their ISCCB. For instance, healthcare workers are social beings [76], who work with friends, family members, and other relations, which can have an impact on security measures. This expresses the need to consider social factors in an effort to estimate the security behavior of a hospital [13,20,41,73,74].

The results showed that only extroversion did not have a significant correlation with any of the psycho-social-cultural traits, but agreeableness was a significant positive weak predictor of SE risk and PS risks. This means that healthcare workers with agreeable characters tend to have high-risk behavior in terms of SE and PS. Related studies found significant correlations among agreeableness versus SE risk [73,74] but not SE and agreeableness. Agreeable personality traits correspond to being cooperative, helpful and kind but require similar treatment [74], and such personalities may feel they will not be punished and would be treated with kindness if they violate security and privacy policies regarding SE and PS.

In addition, conscientiousness and neuroticism had a significant positive weak correlation with cues to action. This implies that higher risks of cues to action behavior corresponded to staff with higher scores in neuroticism and conscientiousness traits. The finding of a higher risk of security practice in relation to neuroticism traits is in line with earlier studies [9,38,73,74] of self-reported cyber security behavior. Staff with neuroticism traits tend to have higher risk behavior, suggesting that emotional stability is a predictor of low cues to action security risk behavior. Furthermore, self-reported hospital information culture was found to have a significant negative correlation with both response efficacy and punishment severity risks behavior, as shown in Table 8 and Table 12. This can be interpreted as finding that higher scores or better hospital security culture predicts low risk of both RE and PS risks. This finding is similar to a related study in which subjective norms were found significant to self-reported ISCCB [20]. In this vein, healthcare facility management can improve upon the cyber-security practice in the area of response efficacy and punishment severity by improving upon the security culture of the hospital through self-efficacy and punishment severity-related incentives.

5.4. Implication of the Study

The results may not be easily generalized due to the differences in the cyber security culture of each country that affects the healthcare domain, but there are various implications. Firstly, the security knowledge of healthcare staff can be improved to enhance their attitude and behavior based on the findings and unique characteristics of the healthcare environment. Secondly, usable security measures can be assessed and implemented such that amidst work emergencies, the healthcare staff can subconsciously comply with security and privacy measures. Finally, psychological perceptions in relation to individual factors, such as personality, can be influenced with the state-of-the-art training, education and learning (TEL) to improve on security practice. For instance, state-of-the-art approaches such as virtual reality (VR) are able to elicit 27% higher emotional engagement than television. In addition, learners who use VR retain 75% of what they are taught as compared to 10% of that from traditional methods. Additionally, surgeons trained using VR make fewer errors and spent less time in cases as compared to surgeons who are conventionally trained [77,78]. Such TEL approaches could induce sound security practices in healthcare.

6. Conclusions

Digitising hospital operations into paperless systems has a lot of benefits for management, staff, and patients. However, this also comes with its associated risks, including the threats of cyber security. Therefore, the security behavior of healthcare staff was assessed to determine gaps and variables that can be improved toward enhancing conscious care security practice. This study covered individual factors, work factors and psychological social and cultural factors. These were then related with security practices to assess the cyber security knowledge, attitude and behavior of healthcare staff in an actual healthcare facility.

A survey was conducted in a typical, paperless hospital in Ghana by collecting self-reported cyber security practices of healthcare staff in psychological, social, and cultural aspects in addition to work-related factors, such as workload and work emergency.

The findings showed that work emergency, ISK risks, and ISA risks have a significant positive weak correlation with self-reported ISCCB risks. From the aspect of psycho-socio-cultural behavior, the study showed that healthcare staff with higher scores in agreeableness, openness and hospital information security culture tend to, respectively, have low cyber security risk behavior in ISK and ISA, social bonding and response efficacy as well as punishment severity. However, consciousness correlated with high risks of information security-conscious care behavior and punishment severity, which is in contradiction with other studies. This implies that usable security measures can be assessed and implemented such that amidst work emergencies, the healthcare staff can subconsciously comply with security and privacy measures. Additionally, the security knowledge of healthcare staff can be improved to enhance their attitude and behavior based on the findings.

This study is limited by the fact that the study participants were assessed for their intended security practices. Since intended security practice is not the same as actual security practice, future studies should practically examine the effect of psychological incentives on security practices. In addition, in this study, the reasons for the correlations are speculative, with the lack of causality. These are inherent attributes of a quantitative survey with correlation analysis. Therefore, future studies should explore a qualitative approach to obtain the nuance of the reasons of the security gaps toward improved decision making for better security countermeasures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Y. and P.K.Y.; methodology, P.K.Y. and M.A.F.; validation, B.Y., P.K.Y. and M.A.F.; formal analysis, P.K.Y. and M.A.F.; investigation, P.K.Y.; data curation, P.K.Y. and B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K.Y., M.A.F. and B.Y.; writing—review and editing, P.K.Y., M.A.F. and B.Y.; visualization, B.Y.; supervision, B.Y.; project administration, P.K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

- (K) I know that visiting any external website with the hospital computing devices at work CAN be harmful to the security of the hospital

- (A) In my opinion, I am confident in myself that I CANNOT be a victim to a malicious attack at work if I visit other websites other than the hospital’s website

- (B) I sometimes VISIT at least one of the following websites using the hospital’s computer: Social media; Dropbox and other public file storage systems; Online music or Videos sites; Online newspapers and magazines; Personal e-mail accounts; Games; Instant messaging services, etc.

- (K) I know that I have to read alert messages/emails concerning security

- (A) In my opinion, it is IMPORTANT to read the alert messages/emails concerning security

- (B) I do NOT often read the alert messages/emails concerning security

- (K) I know that it is not a good security practice to click on a link in an email from an unknown sender

- (A) Nothing bad can happen if I click on a link in an email from an unknown sender

- (B) I sometimes click on links in an email from an unknown sender

References

- Schumaker, R.P.; Reganti, K.P. Implementation of electronic health record (EHR) system in the healthcare industry. Int. J. Priv. Health Inf. Manag. (IJPHIM) 2014, 2, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, S.O.; Yoon-Flannery, K.; Kuperman, G.J.; Langsam, D.J.; Hyman, D.; Kaushal, R. Challenges to EHR implementation in electronic-versus paper-based office practices. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miriovsky, B.J.; Shulman, L.N.; Abernethy, A.P. Importance of health information technology, electronic health records, and continuously aggregating data to comparative effectiveness research and learning health care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 4243–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, A.; Quaresma, R.; Rahman, H. Investigating factors influencing the physicians’ adoption of electronic health record (EHR) in healthcare system of Bangladesh: An empirical study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagliati, A.; Malovini, A.; Tibollo, V.; Bellazzi, R. Health informatics and EHR to support clinical research in the COVID-19 pandemic: An overview. Briefings Bioinform. 2021, 22, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeng, P.K.; Yang, B.; Snekkenes, E.A. Framework for healthcare security practice analysis, modeling and incentivization. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 December 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 3242–3251. [Google Scholar]

- Furnell, S.; Clarke, N. Power to the people? The evolving recognition of human aspects of security. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, A.; McCormac, A.; Calic, D. More than the individual: Examining the relationship between culture and Information Security Awareness. Comput. Secur. 2020, 88, 101640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.; Calic, D.; Pattinson, M.; Butavicius, M.; McCormac, A.; Zwaans, T. The human aspects of information security questionnaire (HAIS-Q): Two further validation studies. Comput. Secur. 2017, 66, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niekerk, J.; Von Solms, R. Information security culture: A management perspective. Comput. Secur. 2010, 29, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeng, P.K.; Yang, B.; Snekkenes, E.A. Healthcare Staffs’ Information Security Practices Towards Mitigating Data Breaches: A Literature Survey. pHealth 2019, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, M.; He, W.; Ash, I.; Yuan, X.; Li, L.; Xu, L. Gender difference and employees’ cybersecurity behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herath, T.; Rao, H.R. Encouraging information security behaviors in organizations: Role of penalties, pressures and perceived effectiveness. Decis. Support Syst. 2009, 47, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, J.; Lowry, P.B. Cognitive-affective drivers of employees’ daily compliance with information security policies: A multilevel, longitudinal study. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Safa, N.S.; Maple, C.; Watson, T.; Von Solms, R. Motivation and opportunity based model to reduce information security insider threats in organisations. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2018, 40, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Posey, C.; Roberts, T.L.; Lowry, P.B. The impact of organizational commitment on insiders’ motivation to protect organizational information assets. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 32, 179–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, A.; Siponen, M.; Pahnila, S. Motivating IS security compliance: Insights from habit and protection motivation theory. Inf. Manag. 2012, 49, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassegger, T.; Nedbal, D. The Role of Employees’ Information Security Awareness on the Intention to Resist Social Engineering. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 181, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeng, P.K.; Szekeres, A.; Yang, B.; Snekkenes, E.A. Mapping the Psycho-social-cultural Aspects of Healthcare Professionals’ Information Security Practices: Systematic Mapping Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2021, 8, e17604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Sookhak, M.; Von Solms, R.; Furnell, S.; Ghani, N.A.; Herawan, T. Information security conscious care behaviour formation in organizations. Comput. Secur. 2015, 53, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeng, P.; Fauzi, M.A.; Sun, L.; Yang, B. Legal Aspects of Information Security Requirements for Healthcare in Three Countries: A scoping Review as a Benchmark towards Assessing Healthcare Security Practices. JMIR Hum. Factors 2022, 9, e30050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebek, B.; Uffen, J.; Breitner, M.H.; Neumann, M.; Hohler, B. Employees’ information security awareness and behavior: A literature review. In Proceedings of the 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 2978–2987. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Alemán, J.L.; Sánchez-Henarejos, A.; Toval, A.; Sánchez-García, A.B.; Hernández-Hernández, I.; Fernandez-Luque, L. Analysis of health professional security behaviors in a real clinical setting: An empirical study. Int. J. Med Inform. 2015, 84, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albarrak, A.I. Evaluation of Users Information Security Practices at King Saud University Hospitals. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2011, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abawajy, J. User preference of cyber security awareness delivery methods. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2014, 33, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L.N.; Cronan, T.P.; Kreie, J. What influences IT ethical behavior intentions—Planned behavior, reasoned action, perceived importance, or individual characteristics? Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechtsen, E. A qualitative study of users’ view on information security. Comput. Secur. 2007, 26, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai, C.; Chandhini, S.A.; Vaishnavi, M. Analysing the concrete compressive strength using Pearson and Spearman. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference of Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Coimbatore, India, 20–22 April 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 215–218. [Google Scholar]

- DeVita, T.; Brett-Major, D.; Katz, R. How are healthcare provider systems preparing for health emergency situations? World Med. Health Policy 2021, 14, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Awais, M.; Singh, N.; Khan, S.; Raza, M.; Malik, Q.B.; Imran, M. Autonomous Transportation in Emergency Healthcare Services: Framework, Challenges, and Future Work. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2021, 4, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamani, J.A.; Amertil, N.P.; Chebere, M. The influence of workload levels on performance in a rural hospital. Br. J. Healthc. Manag. 2015, 21, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamtema, A.S. Bridging the gaps in the Health Management Information System in the context of a changing health sector. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2010, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gratian, M.; Bandi, S.; Cukier, M.; Dykstra, J.; Ginther, A. Correlating human traits and cyber security behavior intentions. Comput. Secur. 2018, 73, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omsorgsdepartementet. How Does Personality Influence Your Cyber Risk? 2021. Available online: https://www.cybsafe.com/community/blog/how-does-personality-influence-your-cyber-risk/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- McCormac, A.; Zwaans, T.; Parsons, K.; Calic, D.; Butavicius, M.; Pattinson, M. Individual differences and information security awareness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uffen, J.; Guhr, N.; Breitner, M.H. Personality Traits and Information Security Management: An Empirical Study of Information Security Executives. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2012, Orlando, FL, USA, 16–19 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shropshire, J.; Warkentin, M.; Sharma, S. Personality, attitudes, and intentions: Predicting initial adoption of information security behavior. Comput. Secur. 2015, 49, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation theory and preventive health: Beyond the health belief model. Health Educ. Res. 1986, 1, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Holm, E.; Zhai, Q. Understanding the violation of IS security policy in organizations: An integrated model based on social control and deterrence theory. Comput. Secur. 2013, 39, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinsky, A.J.; Margolis, M.F.; Sances, M.W. Separating the shirkers from the workers? Making sure respondents pay attention on self-administered surveys. Am. J. Political Sci. 2014, 58, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.; Hauser, D. Understanding responses to check items: A verbal protocol analysis. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–25 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.L.; Bowling, N.A.; Liu, M.; Li, Y. Detecting insufficient effort responding with an infrequency scale: Evaluating validity and participant reactions. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, F.Y.; Kwok, N.; Brown, D.J. Are attention check questions a threat to scale validity? Appl. Psychol. 2018, 67, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B., Jr. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeng, P.; Yang, B.; Snekkenes, E. Observational Measures for Effective Profiling of Healthcare Staffs’ Security Practices. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 43rd Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 15–19 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, K.; McCormac, A.; Butavicius, M.; Pattinson, M.; Jerram, C. The Development of the Human Aspects of Information Security Questionnaire (HAIS-Q). In Proceedings of the 24th Australasian Conference on Information Systems (ACIS), Melbourne, Australia, 4–6 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Drennan, J. Cognitive interviewing: Verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 42, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schechter, S.; Beatty, P.; Block, A. Cognitive issues and methodological implications in the development and testing of a traffic safety questionnaire. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, Danvers, MA, USA, 11–15 May 1994; pp. 1215–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, E.; Schechter, S.; Tucker, C. Interagency Collaboration among the Cognitive Laboratories: Past Efforts and Future Opportunities. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.147.94&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Reeve, B.B.; Mâsse, L.C. Item response theory modeling for questionnaire evaluation. In Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 247–273. [Google Scholar]

- Biemer, P. Modeling measurement error to identify flawed questions. In Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke, J.; Kossowski, T. Comparison of Values of Pearson’s and Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient on the Same Sets of Data. 2011. Available online: https://sciendo.com/downloadpdf/journals/quageo/30/2/article-p87.pdf?pdfJsInlineViewToken=1302953392&inlineView=true (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Arachchilage, N.A.G.; Love, S. A game design framework for avoiding phishing attacks. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, A.; Mubin, N.A.B.A.; Zain, N.A.B.M.; Akil, N.A.B.M.; Aziz, N.A.B.A. Perception of Managers on the Effectiveness of the Internal Audit Functions: A Case Study in TNB. 2015. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1040.1676&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Hair, J.F.; Page, M.; Brunsveld, N. Essentials of Business Research Methods; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survaival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, S.R.; Cheek, J.M. The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. J. Personal. 1986, 54, 106–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Beaman, J.; Sponarski, C.C. Rethinking internal consistency in Cronbach’s alpha. Leis. Sci. 2017, 39, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, R.A.; Meeden, G. Measuring skewness and kurtosis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D (Stat.) 1984, 33, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, N.; Shelton, A.; Ackroyd, F.; Selfe, R. Beyond Murphy’s Law: Applying Wider Human Factors Behavioural Science Approaches in Cyber-Security Resilience. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Málaga, Spain, 22–24 September 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, B.M.; Devarajan, R.; Stolfo, S. Measuring the human factor of cyber security. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), Waltham, MA, USA, 15–17 November 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R. Interpretation of the correlation coefficient: A basic review. J. Diagn. Med. Sonogr. 1990, 6, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.; McCormac, A.; Butavicius, M.; Pattinson, M.; Jerram, C. Determining employee awareness using the human aspects of information security questionnaire (HAIS-Q). Comput. Secur. 2014, 42, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, H.G.; Gupta, S. The Misunderstood Link: Information Security Training Strategy. In Proceedings of the 24th Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 16–18 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, H. Cybersecurity: Role of Behavioral Training in Healthcare. 2016. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/301368936.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Ghazvini, A.; Shukur, Z. Review of information security guidelines for awareness training program in healthcare industry. In Proceedings of the 2017 6th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI), Langkawi, Malaysia, 25–27 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Alami, H.; Gagnon, M.P.; Ahmed, M.A.A.; Fortin, J.P. Digital health: Cybersecurity is a value creation lever, not only a source of expenditure. Health Policy Technol. 2019, 8, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppel, R.; Smith, S.; Blythe, J.; Kothari, V. Workarounds to computer access in healthcare organizations: You want my password or a dead patient. In Driving Quality in Informatics: Fulfilling the Promise; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Stobert, E.; Barrera, D.; Homier, V.; Kollek, D. Understanding cybersecurity practices in emergency departments. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Middaugh, D.J. Cybersecurity Attacks during a Pandemic: It Is Not Just IT’s Job! Medsurg Nurs. 2021, 30, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Shappie, A.T.; Dawson, C.A.; Debb, S.M. Personality as a predictor of cybersecurity behavior. Psychol. Pop. Media 2020, 9, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevi, T.; Memon, N.; Lewis, J.; Kumaraguru, P.; Arora, S.; Dagar, N.; Aloul, F.; Chen, J. Cultural and psychological factors in cyber-security. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Information Integration and Web-based Applications and Services, Singapore, 28–30 November 2016; pp. 318–324. [Google Scholar]

- Skorek, M.; Song, A.V.; Dunham, Y. Self-esteem as a mediator between personality traits and body esteem: Path analyses across gender and race/ethnicity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Box, D.; Pottas, D. Improving information security behaviour in the healthcare context. Procedia Technol. 2013, 9, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurusamy, K.; Aggarwal, R.; Palanivelu, L.; Davidson, B. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials on the effectiveness of virtual reality training for laparoscopic surgery. J. Br. Surg. 2008, 95, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, C.R.; Oestergaard, J.; Ottesen, B.S.; Soerensen, J.L. The efficacy of virtual reality simulation training in laparoscopy: A systematic review of randomized trials. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).