Abstract

Anti-gender groups, by promoting a Christian-inspired traditional view of family, challenge the idea that European society is becoming more secular. Given that previous literature has highlighted how these groups extensively use digital media and are connected to the Vatican, this article explores the following questions: How do anti-gender groups discuss religion on social media? What is the role of religion for anti-gender activists? By means of a review of research on anti-gender movements, secularism, and activism, this article argues that anti-gender groups do not directly contribute to the growth of religious institutions but use religion to bring actors together in mobilizations, in what I define as an instance of Christian transcalar activism. A mixed-method approach, including quantitative and qualitative analysis of the Instagram pages of the anti-gender group CitizenGO, combined with observations and interviews with activists, suggests that religion is not a central topic in digital narratives, which mainly construct a perceived marginalization of Christians in secular society; however, Catholicism is fundamental for activists as a motivation for action and a socialization force. In conclusion, anti-gender groups’ digital media use connects different actors and mobilizes people who are already religious and who engage in activism through their religious communities.

Keywords:

anti-gender; Christianity; Catholicism; CitizenGO; secularism; Instagram; social media; Internet 1. Introduction

In contemporary Europe, some political and social actors who hold a common conservative ideology use religion to discuss gender-related issues. Studying the so-called anti-gender groups, which organize actions and communications inspired by Christian principles against the perceived threat of “gender ideology” (Graff 2016), contributes to understanding the role of religion in the European public sphere. Anti-gender movements started to gain visibility in the U.S. and Europe around 2012/2013 in opposition to same-sex marriage, and then broadened the scope of their actions to include other gender-related issues (Kuhar and Paternotte 2017). In analyzing the anti-gender organization CitizenGO, which was founded in Spain as Hazte Oir as a result of the country’s campaigns against same-sex marriage and other gender-related issues in the 2000s, Cordoba Vivas (2023) offers the following definition:

“Anti-gender” forces have successfully framed the debate around gender and sexuality using the concept of “gender ideology,” a flexible and adaptable notion that allows them to agglutinate in a single discursive entity many of their interrelated anxieties: feminism, homosexuality, trans identities, abortion, sex education and reproductive rights.”(p. 4)

As per this quote, anti-gender groups consider that “gender ideology” is a secular and leftist conspiracy that challenges traditional gender roles and family values. The present article will explore this concept by looking at online narratives as well as activists’ narratives. Therefore, it addresses the following research question and sub-questions:

Rq1: What Religious-Related Narratives Are Articulated by Anti-Gender Groups?

Sub-question 1: How Do Anti-Gender Groups Discuss Religion on Social Media?

Sub-question 2: What Is the Role of Religion for Anti-Gender Activists?

The first sub-question looks at social media narratives through the example of the Instagram page of the international organization CitizenGO. It has been chosen because it has connections with several national groups and organizes online campaigns and offline actions alike (Katsiveli and Coimbra-Gomes 2020). CitizenGO, like other anti-gender groups, is linked to far-right political parties (Korolczuk and Graff 2018). Furthermore, anti-gender and far-right forces share a populist attitude that portrays gender ideology as an “elite” conspiracy laid upon the “masses” (Lavizzari and Pirro 2023). Populist communication finds a fertile venue on social media (Gerbaudo 2018), especially when anti-gender groups are suspicious of “mainstream” media for allowing themselves to be subjected to gender ideology and allegedly too secular. In addition, these movements use the Internet because they are usually inspired by Catholic principles, but act outside of the traditional channels of the Vatican and other organized religious institutions. Anti-gender communication has two salient characteristics: first, digital media help the spread of post-truth conspiracies (Harsin 2018), something that resonates with anti-gender activists who adhere to conspiracy theories about, for instance, the alleged presence of a powerful and rich “gay lobby” (Salvati et al. 2024); second, anti-gender groups use the Internet for a post-modern style of communication, including “parody, sampling, pastiche, irony, drag” (Graff 2016, p. 271). However, as argued by Righetti et al. (2025), “how anti-gender organizations use social media for the mainstreaming and transnationalization of anti-gender ideas remains underexplored” (p. 1). The present article seeks to address this research gap.

Furthermore, the second sub-question explores the experiences of anti-gender activists, with a focus on religion. I addressed the sub-question by means of interviews and observations of events connected with CitizenGO. In so doing, I considered the strong connections between anti-gender movements and religion, and Catholicism in particular (Case 2019). In this respect, Garbagnoli (2016) posits that “gender ideology” is a rhetorical device created by the Vatican to foster a moral panic about a perceived enemy that threatens traditional family values. Indeed, the Vatican put the concept forward after the 1995 UN Conference on Women in Beijing and reiterated it in the 2003 Lexicon, a dictionary where the term “gender” is considered “problematic” (De Pittà and De Santis 2005). Hence, Lavizzari and Prearo (2018) discussed anti-gender activism in Italy as a “hybrid political space of Catholic action”. Despite the importance of Catholicism for anti-gender mobilizations, religious frames are rarely included in studies on activism (Snow and Beyerlein 2018); furthermore, focusing on the topic of religion helps understand the heterogeneity of the Catholic Church regarding feminism and gender-related issues (Giorgi and Palmisano 2020). Hence, this article aims to offer a more complete picture of the role of religion in anti-gender mobilizations, focusing on Catholic activism, as this is the milieu where the opposition to “gender ideology” started to gain attention.

By addressing these research questions, the scope of the article is twofold. On the one hand, it seeks to assess the growing importance of religion in the European public sphere as a catalyst for political and social mobilization regarding gender. On the other hand, it engages with Catholic activists by assessing how religion offers them a space for socialization and organization. It is worth noting that anti-gender groups are not limited to Europe, and not all activists are Catholic; however, as will be detailed in the Methods section, this article is based on observations and interviews with Catholic European-based activists and analyzes social media narratives that target the European public sphere. It aims at providing empirical data to critically assess theories of the secular rooted in the European context. By analyzing both social media posts of a prominent anti-gender group and interactions with activists, this article discusses religious-related narratives from multiple viewpoints, which are nonetheless related, as these movements’ online and offline actions complement each other (Evolvi 2022).

Section 2, by means of a review of previous literature on anti-gender movements, discusses secularism in contemporary society, and presents the concept of transcalar activism (Kalm and Meeuwisse 2023). Section 3 details the article’s methodological approach, explaining that it is innovative in combining quantitative and qualitative analysis of Instagram posts with interviews and observations with activists. The results, discussed in Section 4, show how religion might have a greater role in offline settings rather than online venues. Hence, the section starts by presenting the quantitative data from social media, where religion does not seem to occupy a prominent role; second, it offers some qualitative examples of Instagram posts, which use religion to present anti-gender movements as “victims” of secular culture; third, it analyzes interviews and fieldnotes, showing how religion is often fundamental for activists engaging with these groups. Section 5 discusses how the findings confirm previous literature on anti-gender groups’ use of digital media and religion; however, this article adds complexity to the current state of research by showing how recruitment and socialization seem to happen in religious milieus. In the conclusion, I contend that the framework of Christian transcalar activism can explain how anti-gender movements do not directly connect with religious institutions, but rather glue together different actors through narratives based on Christian values and use religion to engage activists.

2. Anti-Gender, Secularism, and Activism: A Review of Literature

Anti-gender groups’ use of Christianity suggests that religion continues to play a role in society, politics, and digital communications, thus compelling reflections on the theory of secularization. Due to growing migration, the multifaced character of religious practices, and the need for laws and policies regulating religious diversity, secularization can be rethought in terms of “multiple secularities” (Wohlrab-Sahr and Burchardt 2012), or through post-secular frames (Sajir and Ruiz Andrés 2025). Starting from similar premises, this article reflects on the complexity of secularization and addresses theories that explain the intersection of religion, gender, activism, and politics. This section will first discuss the increasing visibility of religion through an analysis of political and ideological positions that assume anti-gender stances to defend traditional family values; then, it will ground this literature in theories about the secular, introducing the concept of Christian secularism; finally, it will engage with works on activism, proposing the framework of Christian transcalar activism to account for the actions of anti-gender groups and the multi-layered character of the secular in contemporary Europe.

2.1. Religion and Gender “Panic”

Anti-gender movements are part of a larger social and political trend that uses religion to justify decisions and policies about gender, thus contributing to processes of religious re-publicization. As argued by Botelho Moniz and Brissos-Lino (2024), who explored the Portuguese context, society is witnessing an increasing politicization of religion, which results in “an expression of and a reaction to secular modernity” (p. 9). The paradox lies in the fact that this anti-modern attitude is deeply rooted in modernity, as it is mostly a reaction to a perceived threat of secularization. This political use of religion can be found in several European parties, like the Spanish Vox, the Italian Fratelli d’Italia, and the German Alternative für Deutschland (Evolvi 2025). In some cases, as happens with the Dutch party Forum voor Democratie, political parties express themselves in alternative venues of knowledge production and anti-academia stances (Segers 2024).

The trend of producing “counterknowledge” as a resistance to secular modernity is also found on social media, which facilitate the discussion of gender and sexual identities among young Christians (Hunklinger and Limacher 2025). The Internet offers a fertile venue for conservative Catholics, in particular the so-called “traditional” (or “trad”) Catholics, who advocate a return to pre-Second Vatican Council religious practices (Griffin 2024). Connected to this phenomenon are the so-called “tradwives”, women who use social media to promote a homemaking lifestyle based on traditional family values, and who have been found to play a role in the diffusion of far-right ideologies (Leidig 2023). Pushing back against feminism, abortion, and same-sex marriages, tradwife influencers contribute to using religion for the same aims as anti-gender movements (Tebaldi and Baran 2023).

The use of religion to create nostalgia for traditional values is connected to a perceived threat posed by the diffusion of “gender ideology”. According to Butler (2024), gender is a buzzword that far-right leaders and conservative forces employ to put together anxieties about contemporary society. Besides political milieus, gender as a “rhetorical device” has been used by the Vatican since the mid-90s to “reaffirm the transcendent nature of the sexual order” (Garbagnoli 2016, p. 188), thus promulgating a heteronormative view of family. The work of Righetti (2016) considers how this gender-related moral panic has been brought to activism by the Italian group Sentinelle in Piedi. This group, through silent public demonstrations, proclaimed homosexuality as a “distortion of the natural order” (p. 284) to preserve the gendered distinctions of their symbolic universe. This example shows how the term “gender” is largely constructed in opposition to the natural order, as something that can bring perceived chaos to society (Graff and Korolczuk 2021). Therefore, the surge of anti-gender movements and groups that oppose “gender ideology” points to a new complexity of religion and secularism: it is not only a matter of religion being relevant in the public sphere, but religious values are also used to oppose a type of secularism that is seen as leading to a threatening gendered chaos.

2.2. Anti-Gender Groups and Secularism

The growing importance of religion in anti-gender mobilizations in Europe happens against the backdrop of surveys showing a progressive decline in institutional religiosity (Hackett et al. 2025), which suggests that Europe might be more secular than other parts of the world. Famously, Davie (2002) discusses European “exceptionalism” to illustrate trends in European religion, including the progressive disconnection of people from religious institutions. In building a theory of secularization, Casanova (1994) posits that Europe is the place where the three tendencies of contemporary religiosity—differentiation, decline, and privatization—occur at the same time. This point seems to be confirmed by Kasselstrand’s (2022) more recent empirical study, which discovers that “with the deinstitutionalization of religion, we may be seeing new ways of being religious, but we are undoubtedly observing a stronger trend of religious decline at the same time.” (p. 48).

Therefore, while religion in Europe is used for anti-gender politics and activism, its overall relevance seems to be declining. I would argue that this happens because anti-gender actors’ use of religion does not aim at increasing the importance of religious institutions, nor at challenging secular institutions. There are two main reasons supporting this perspective. First, while directly connected to religious ideologies, anti-gender groups usually do not claim a link with religious institutions. Indeed, anti-gender groups use Christianity as a way of creating an alternative reality to what is perceived as the liberal (and secular) political mainstream (Ayoub and Stoeckl 2024). In this context, it is also worth noting that far-right groups do not directly appeal to Christian voters, and do not usually seek the support of the clergy, but rather use religion as an ideological resource (Cremer 2022). Hence, right-wing leaders, such as the Italian Matteo Salvini, frequently create online narratives where Christianity is used instrumentally to create a shared identity and criticize Islam, but also oppose mainline churches (Marchetti et al. 2022). In other words, groups that situate themselves on the conservative end of the political spectrum and defend traditional views of gender often promote a type of nationalism where religion functions mainly as an identity frame (Gorski et al. 2022).

Second, anti-gender groups usually refer to Christianity in Islamophobic and racist terms, using religion to exclude other people rather than supporting Christian churches. Scholars who discuss the theory of secularization argue that religion in Europe is gaining visibility because of migration and the growth of the Muslim population (Bhargava 2014; Pepicelli 2010). As Davie (2023) explains, the two trends of growing secularization and increasing diversity intersect at the political and policy level, eliciting a dialogue regarding the management of religion across European countries. In this context, anti-gender groups usually refuse to engage with religious diversity in positive terms, but rather demand that secular institutions “protect” women—and, specifically, White and Christian women—against the perceived threat of immigrants (Farris 2017). Indeed, far-right parties tend to support traditional views of gender in anti-migration and anti-Islam efforts, as they promote the growth of White and Christian families only (Norocel and Giorgi 2022).

In sum, anti-gender groups seem to use religion mostly as an ideological resource, without necessarily seeking the endorsement of religious authorities, and using Christianity in anti-migration stances. This does not actively contribute to the growth of religious affiliation or greater privileges for religious institutions in society. This phenomenon can be theoretically explained through the perspective of strategic secularism, elaborated by Engelke (2009) with respect to the Bible Society of England and Wales. This theory shows how religion can be framed in terms of cultural heritage through the incorporation of secular discourses. In this sense, the Bible Society did not try to evangelize, but rather to make people think about the Bible differently against the backdrop of secularization.

With respect to strategic secularism, Vaggione (2005) discusses how matters of gender and sexuality become pivotal to theorize the current public role of religion in civil society. Conservative actors discuss gender without decoupling religion and secularism, but rather present them as belonging to a coherent framework (p. 243). This perspective can be put in conversation with that of Christian secularism, a framework I previously applied to far-right parties and that can also be used to study anti-gender groups (Evolvi 2025). Specifically, I consider Christian secularism as referring to ideologies that see society as secular, and posit that Christianity is the only religion that is compatible with secularism. This approach, which is akin to what has been defined in the literature as a Catholic model of secularism (Frisina 2010), can be seen, for instance, in juridical decisions that allow the wearing and use of Christian symbols, but not Muslim ones (Evolvi and Gatti 2021; Oliphant 2012). In discussing these perspectives, I employ the term secularism, which indicates a political doctrine and an ideology, and is distinct from secularization, which is the process of religious decline, differentiation, and privatization (Asad 2003; Casanova 1994).

In the case of anti-gender movements, they present themselves as forces of social change within a secular society, thus employing narratives and strategies that are more akin to secular activism rather than religious evangelism. Hence, Colmán (2025) describes the tactics of anti-gender groups in Guatemala and Paraguay as examples of strategic secularism, as they increasingly moved from religious narratives to secular terms and justifications. Groups such as CitizenGO, while employing a secular language, continue to assume that Christianity provides them with ethics, morality, and ideological resources for action. It is for this reason that I employ the term Christian secularism to show how theoretical reflections on secularization also need to account for the political and public use of religion, even when this approach to religion is not directly connected to religious institutions or supported by religious leaders.

2.3. Christian Transcalar Activism

The apparent paradox of religion declining in Europe while retaining an important role in the public sphere is explained in a study on Catholicism in Spain by Griera et al. (2021). The scholars argue that secularization needs to be understood in relation to the different fields in which religion is mobilized, notably public service, morality politics, and politics of belonging. These three categories include, respectively, the predominant presence of Catholicism in public spaces and institutions; religion’s ability to spread “moral panic” concerning issues such as abortion or euthanasia; and the political use of religion in nativist discourses and identity construction. These categories can be observed in several contemporary cases, as with young Catholics in Spain and Mexico, who present themselves as “moral entrepreneurs” in conservatively religious social movements in a secular environment (García Martín et al. 2023).

Considering such reflections, I argue that anti-gender movements’ use of religion does not only need to be defined in terms of their ideological connections to religion and secularism, but also in relation to the social fields where they operate and structure their activism. In this regard, it is worth noting that anti-gender groups like CitizenGO glue together different actors in local, national, and transnational spaces. Hence, in analyzing the anti-gender event World Congress of Families, where CitizenGO occupies an important role, Kalm and Meeuwisse (2023) introduced the term transcalar activism. This perspective captures how anti-gender movements frequently assemble actors from religious and political social spheres under the perceived threat of “gender ideology” to challenge the Western liberal order. This differs from transnational activism as it not only regards global-scale actions. Rather, the perspective shows how the idea of “natural family” seems to act as a “symbolic glue” to unite anti-gender and conservative groups in domestic and international settings that otherwise would not work with each other (p. 557). Anti-gender networks are indeed constituted by various actors, including conservative Christians (and Catholics), pro-family NGOs, and conservative politicians, which are reunited in the same fight against the perceived threat of gender (Vaggione 2020).

Transcalar activism, therefore, implies actions connected to various political, social, and religious movements, and it can be put in conversation with the idea that religion operates in terms of public service, morality politics, and politics of belonging. While the theory is not explicitly about religion and secularization, as it is situated in the field of international relations, transcalar activism confirms Griera et al.’s (2021) argument that the decline in religion does not imply a disappearance of the public role of religion, which remains pivotal in anti-gender gatherings in attracting religious activists alongside political forces. I then propose to use the term Christian transcalar activism to discuss how groups like CitizenGO utilize religion in different fields, for instance, to create moral panic about gender-related issues, but also in building relations with other actors, such as far-right leaders. This relates to both strategic secularism, because actors often employ secular language and strategies, and Christian secularism, because they imply that Christianity (and, sometimes, Catholicism more specifically) provides the ideological and moral resource for anti-gender efforts.

Therefore, based on previous literature, it appears that a perceived threat of a gendered chaos can elicit what I would define as Christian transcalar activism; this activism uses religion as a glue among different actors and networks, both at the local and international level, and allows for interventions in public spaces, policy making, and national identities. Christian transcalar activism is an example of how religion in Europe has a public role that is not directly connected to formal institutions, nor to the number of people affiliated with them. This activist use of religion does not challenge the existence of secular institutions, but enters into dialogue with them by implying that Christianity is the only religion that can provide them with moral and ethical resources.

3. Methodology: Between Digital Media and People’s Experiences

I explored anti-gender groups’ use of digital media and engagement with religion through a mixed-method approach that included a quantitative and qualitative analysis of CitizenGO’s Instagram page (to address the first sub-question) combined with interviews with activists and observations of anti-gender events (to answer the second sub-question). Employing these two approaches, which will be explained in the following sub-sections, is innovative in exploring both the narratives and topics facilitated by social media, the preferred means of communication of anti-gender groups, and the activists’ experiences and protest strategies, which remain relatively understudied.

3.1. Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis of CitizenGO’s Instagram

The first research step involved an analysis of posts and images of CitizenGO’s official Instagram page in English. CitizenGO was established in Spain as HazteOir (short for HazteOir—Victimas de la ideología de género, “makes yourself heard, victims of gender ideology”) in 2001 by Ignatio Arsuaga (Rivera 2019). HazteOir was created following debates to legalize same-sex marriages in Spain in the early 2000s. While the majority of the Spanish population identifies as Catholic, there is a growing tendency to disregard the position of the Catholic Church in matters such as LGBTQ+ rights, thus creating a fertile venue for polarization around gender-related issues; hence, Spain was the first European country with massive anti-gender mobilizations (Cornejo and Pichardo Galán 2017). HazteOir engaged in several actions, including buses driving across Spain with the slogan “Boys have penises, girls have vulvas. Do not let them fool you”. According to Barrera-Blanco et al. (2023), with such messages, HatzeOir provides an example of strategic secularism, as the activists insist on the secular character of their ideology. In 2013, HazteOir started the international brand CitizenGO, which is connected with far-right parties like the Spanish Vox and the Italian Lega Nord, and is active in organizing anti-gender events like the World Congress of Families (Evolvi 2023).

I chose to focus on CitizenGO because it fulfilled three criteria deemed relevant for the study: first, it is an organization that, while formally separate from the Vatican, is rooted in conservative Catholicism, thus offering data on how Catholicism can function as a resource for activism. Second, it is active both offline and online (Katsiveli and Coimbra-Gomes 2020), something that allows for a multi-level analysis of its activist strategies. Third, it has a strong international outlook, while at the same time partnering with national groups to promote events such as Marches for Life, which facilitates in-person observations and interviewee recruitment. In sum, with over a decade of social media communication, CitizenGO is “uniquely positioned to coordinate transnational strategies aiding the spread and mainstreaming of the anti-gender agenda” (Righetti et al. 2025, p. 2).

CitizenGO has a website and social media pages in 11 languages, and I considered the English one (@citizenGO). This page is not connected to a local context—as opposed to the Italian one, for instance, which has the handle @citizenGO_italia –and has 2463 followers as of October 2025. This makes the page in English the one with the most followers (see Righetti et al. 2025, Supplementary Materials), and arguably the venue for posts that connect local and national campaigns with the movement’s transnational dimension. I focused on the platform Instagram because of its affordances, which include “visual content, brevity, and rapid consumption” (Griffin 2024, p. 4). This contributes to the creation of gender-related aesthetics and affective polarization, as well as criticism of the “elites” and alternative knowledge production.

I collected all of CitizenGO’s posts between 2013 (when the page was opened, the same year CitizenGO was established) and October 2024, including both pictures and their captions. To do so, I employed the Python (3.12) -driven code Instaloader (Di Cristofaro 2023). This resulted in a dataset of 1472 posts and 2475 pictures and videos (because a single caption can correspond to multiple audio-visuals). I did not collect comments, as the page does not extensively engage users, but seems aimed at communicating information. Having noted that several pictures in the downloaded dataset contained texts, which sometimes consisted of articles or reflections that were longer than the corresponding caption, I automatically transcribed them with the application Tesseract for Python. Upon checking the text manually for errors in the automatic transcription, I performed a Python-assisted keyword analysis and topic modeling, approaches that allow for mapping the predominant lexical choices and organizing the posts in topics (Vrangbæk et al. 2025). This is akin to the study of Righetti et al. (2025), who also implemented topic modeling on the groups’ website and social media pages, mapping the frequency of terms and connections linked to anti-gender ideologies and religion.

Subsequently, I performed a qualitative analysis of the posts that addressed religion, which I selected manually through a keyword search, as illustrated in Table 1. The keyword search focused on religion and offered results addressing different contexts and audiences. While qualitatively analyzing the posts, I selected those relevant to the study of the secular in Europe, which can be ascribed to three categories: first, narratives about happenings in specific European countries; second, texts and pictures targeting institutions and organizations linked to the European Union, which is described as an agent spreading “gender ideology” (Vida 2019); third, posts that do not refer to a specific national context, but target European people as part of a global audience. Following the selection of posts, I carried out a multi-level Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) on both texts and pictures (Machin and Mayr 2012) through the software MAXQDA (Analytics Pro 24). CDA pays attention to linguistic elements that unveil power relations and social inequalities (Fairclough 2013), and has been applied to discourses related to gender and far-right politics (Sengul 2019). Due to copyright issues, the pictures have not been replicated in this article, but I describe them instead.

Table 1.

Religion-related words within CitizenGO’s Instagram posts.

3.2. Interviews and Participant Observations

Alongside social media analysis, I conducted interviews and observations. The data came from a larger project focusing on Catholic activism, for which I observed different events, for example the 2024 March for Life in Rome (Italy). Then, I made contact with pro-life groups that are ideologically close to CitizenGO and organize events and petitions together with them, such as Rachel’s Vineyard (an international organization providing spiritual assistance to people who have had an abortion), Christian Concern UK (a group that promotes family-values), and Pro Life Insieme (a network of anti-abortion organizations in Italy). Then, this article considered the data from 12 interviews, conducted either via email or face-to-face, with Catholic anti-gender and pro-life activists based in Italy and Spain. I subsequently examined interview transcripts and fieldnotes through a MAXQDA-assisted thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006).

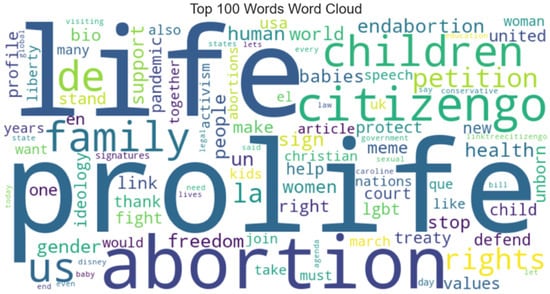

It is worth noting that CitizenGO does not have a formal membership—even if it considers as “members” all those who sign petitions on its website—and rarely organizes events on its own. To connect the analysis of the Instagram posts with the activists’ experiences, thus ensuring that the two sub-questions were linked, I chose events and activists related to CitizenGO. For instance, I observed Marches for Life where CitizenGO was a co-sponsor, and I interviewed activists from the Italian group Pro-Life Insieme, whose creation was supported by CitizenGO. I selected interviewees of both genders, without placing age restrictions. I chose to interview only Catholics, something that allowed for the exploration of the religious resources of CitizenGO, as it was established in the context of Spanish Catholicism. However, other contexts, like North America, would see connections with people belonging to other Christian denominations in anti-gender activities linked to CitizenGO. Most of the interviewees were active in pro-life organizations, which center on anti-abortion activism; as shown in Figure 1, this is an extremely important topic for CitizenGO, to the point that many events co-organized by this group are about abortion. They usually do not label themselves as “anti-gender”, which is a term mostly used in academic literature, or “anti-abortion”, language that might carry negative nuances, preferring “pro-life” instead. Therefore, I use the term in this article to echo the interviewees’ language.

Figure 1.

Top 100 words used in the CitizenGO Instagram posts.

With respect to my own positionality, I am not part of any groups I enquired about, and I do not share their aims. This brought difficulties in approaching potential interviewees, as many refused to engage with me, also because of their suspicion or hostility toward academics. While some emails I sent were ignored or answered negatively, others elicited hostile answers belittling me and my work. This is one of the reasons most academic inquiries on anti-gender movements focus on textual analysis rather than interviews (with some notable exceptions, see Lavizzari 2019). Regarding this, Avanza (2008) reflects on the difficulties of ethnographies with groups holding a different ideology than the researcher’s; often, this results in scholars choosing research objects that are closer to their own worldview, but in so doing, they miss opportunities to understand given cultures or ideas. For example, Avanza (2020) engaged in ethnography with an Italian pro-life group that helped her discover a nuanced reality of women whose stories—which included experiences of abortion, low-income households, and migration networks—are usually overlooked in studies on the topic.

Following the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of Bologna, I informed my interviewees of the scope of my project while giving them the informed consent and data privacy forms, but I did not delve into my personal ideas and motivations. During events, I gathered insights from informal conversations with participants who did not know that I was a researcher, and therefore, I use them as background information, without openly quoting them. Despite this, I believe that interacting with anti-gender activists was central to my understanding of the role of religion in movements like CitizenGO.

4. Results: Christians as Victims, Faith as Motivation

As discussed in the previous section, the results stem from a quantitative and qualitative analysis of CitizenGO’s Instagram page, as well as the analysis of fieldnotes and interview transcripts about the activists’ experiences. These types of analysis gave slightly different results regarding the role of Christianity, and Catholicism in particular: while on social media religion is not central to most narratives, demonstrations and activists’ accounts suggest that Catholicism is among their main motivations for actions.

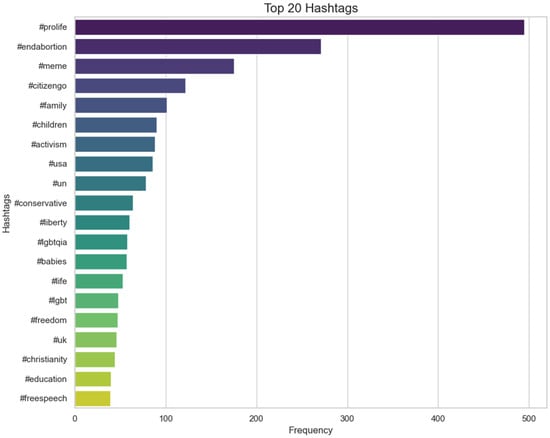

4.1. Keyword Analysis and Topic Modeling of CitizenGO’s Instagram Page

A keyword analysis of CitizenGO’s Instagram posts confirmed the centrality of pro-life activism, as well as narratives around children and family values. Figure 1 shows the 100 most-used words in the dataset. Among the top 100 words, only “Christian” refers to religion, and it ranked number 50. Figure 2 represents the 20 most-used hashtags, which mirror the dominant lexical choices illustrated in the previous two pictures. Here, the hashtag #Christianity appeared in this list, even if its use was not as prominent as the top two, #ProLife and #EndAbortion. It is worth noting that the use of #Christian does not mean that the post is about religion, as sometimes hashtags are used to suggest connections with certain words and ideas that are not explicitly mentioned.

Figure 2.

Top 20 hashtags used in the CitizenGO Instagram posts.

A manual search of religious-related keywords contained in both images and captions showed that the term “Christian” (and its derivatives, like “Christianity”) appeared 127 times, as illustrated in Table 1. This was followed by the terms “belief”, “faith”, “God”, and “religion”, which do not suggest a link to a specific denomination but are generally used in connection with Christianity. The words “Catholic” and “Church” were present but not very relevant, and “Islam” was found only 10 times, with no mentions of other faiths. This shows the centrality of Christianity and a disengagement with specific Christian confessions or other religions. This could also point to a type of strategic secularism (Engelke 2009) that downplays the use of religious terms for CitizenGO activists to present themselves in the secular public sphere.

Furthermore, an automated topic modeling of the dataset suggests that while not the most prominent, Christianity figured among the fifth predominant themes that CitizenGO discussed. As illustrated in Table 2, the topic modeling shows how the group CitizenGO is engaged in what Kalm and Meeuwisse (2023) define as transcalar activism, as most of the themes refer to the liberal world order (often incarnated by entities like the European Union or the WHO) imposing certain ideologies on citizens. For example, there is the idea that people are not free to choose their health and education, and that they are prevented from voicing their opinions. The topic of Christianity is connected to that of freedom of speech, and pushes forward the idea that Christian people are either hindered in expressing their faith or from making decisions based on their religion; this includes individuals who face charges for religious-inspired homophobic hate speech or who refuse abortions and end-of-life treatments because of their religious convictions. Starting from these premises, the next section qualitatively analyzes some posts that belong to this category.

Table 2.

Topic modeling of CitizenGO Instagram posts.

4.2. Qualitative Analysis of CitizenGO’s Instagram

After the manual search of keywords related to religion illustrated in the previous section, I proceeded with a Critical Discourse Analysis. It is worth noting that the use of the word “Christian”, as illustrated in Figure 1, has multiple meanings attached, which cannot be captured by a quantitative analysis. Hence, a qualitative analysis of the posts related to religion showed that Christianity was often quoted as an ideological resource and a motivation for action, and it was frequently mentioned in posts that discussed perceived marginalization or even discrimination against Christians in a secular culture. Depending on the context of the posts, as illustrated below, religion can be attached to freedom of speech, or to anti-abortion activism, or to questions surrounding LGBTQ+ rights.

For example, a post published on the 16th of August 2023 supports Finnish politician Päivi Räsänen. After criticizing the Lutheran church for taking part in the LGBTQ+ pride in 2019, Räsänen was investigated for spreading hate against minorities. The picture of the post features the Finnish flag and Räsänen reading the Bible. This post was published in the context of CitizenGO’s campaign for Räsänen, which claimed that she was tried for her religious faith. The slogan on the picture, “Christianity is not a crime! Defend Päivi Räsänen and Christian speech. Sign our petition” powerfully brings attention to the issue of religious freedom, rather than that of hate speech and homophobia that Räsänen is accused of. The presence of the Finnish flag implies that this is a national case, but CitizenGO uses it to create a general sense of threat and marginalization for all Christians, who are called to act by signing the petition.

The topic of Christian victimization and religious freedom is also addressed in a post about acts of violence based on religion and belief, published on the 22nd of August 2021. The caption to the post reads as follows:

On this International Day Commemorating the Victims of Acts of Violence Based on Religion or Belief, let us take a minute and reflect on those who suffer persecution in all parts of the world for professing their faith. The situation is truly alarming.

Religious freedom is violated in almost a third of the world’s countries (31.6%), where up to two-thirds of the world’s population lives.

The most common causes of persecution are Islamist extremism, authoritarian regimes, and ethnoreligious nationalism.

Although Christians are the most persecuted group in the world, Uighurs, Rohingyas, Yezidis, and others suffer similarly.

To those who suffer, wherever you are, we stand with you.

#CitizenGO #Freedom #Persecution

Interestingly, the post discusses all faiths, addressing “those who suffer persecutions in all parts of the world”. However, the same caption also highlights how Christians are “the most persecuted group in the world”. In the picture that accompanies the caption, two women hold a crucifix, suggesting that they are Christians. Their appearance and garments, including colorful headcovers, place them in a non-Western context, perhaps a Muslim-majority country in the Global South. This is also likely because the caption mentions “Islamist extremism” among the most common causes of persecution. Hence, while the post acknowledges that other groups like Uighurs and Rohingyas (alongside Yezidis) face violence, there is no mention of them being Muslims. This frames Christians as victims, and Islam as a problem, thus reinforcing fear around Muslim violence worldwide.

Another post, published on the 8th of August 2024, expresses the idea that Christian beliefs can and should push people to action, and that Christians face threats. In response to the opening of the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris, where a group of drag queens re-enacted the Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci, CitizenGO organized a bus campaign. The post’s picture features the bus, together with the words “We were Arrested by the French Police for saying ‘stop attacking Christians!’ Donate to support our battle against tyranny!”. The caption reads:

The French Police unjustly arrested us! All we did was spread the message “STOP ATTACKS ON CHRISTIANS!” through text on a bus. There is nothing illegal or wrong about this. This is clearly anti-Christian persecution from French authorities.

Please spread this news around. Tyranny like this cannot go unchallenged. #Paris2024

If you wish to support us, please visit the Link in our Profile Bio to Donate

In the post, the “persecution against Christians” and “tyranny” refer to the arrest of seven CitizenGO activists for protesting without permission. The call to action in the post points to a double perceived marginalization of Christians: first, they were “attacked” by a LGBTQ+ performance that was against their values and felt blasphemous; second, they faced “persecution” because the French government arrested them during the protest. The use of emotionally charged words results in a dichotomy between “Christians” and the “tyranny” of a secular state, in this case France, which mocks and then silences them.

The contraposition between Christian values and secular ones is also illustrated in a satirical meme, published on the 21 September 2024. The meme features a cartoon of what seems to be a caricature of a blue-haired, angry feminist. She stands in front of a pile of dead babies, presumably the results of multiple abortions. The woman pronounces the words “Christianity is a death cult”, ironically implying two things: first, that Christians are negatively perceived in society, to the point of being associated with death; and second, that Christians are the ones fighting a “culture of death” by engaging in pro-life activism. By implying that the “non-Christian” woman killed the babies, as well as showing the triggering pile of bodies, the post offers a strong visual connection between abortion and murder. In addition, it implicitly condemns secular culture and its enactment of a type of femininity that no longer cares for children.

The posts analyzed in this section show how Christianity is connected to a variety of topics, like pro-life activism, free speech, religious freedom, and anti-LGBTQ+ feelings. What they have in common is that they create a dichotomy between Christianity and secularism or Islam. In so doing, they contribute to spreading a type of gendered panic (Butler 2024), implying that the decline of religion and the progression of secular culture will destroy gender norms and family values. Thus, Christianity seems to offer an ideological resource to action for the group, often in opposition to secular values. At the same time, online narratives do not emphasize religious institutions and present the actions of CitizenGO in a secular context, where anti-gender efforts occur. In this sense, the framework of Christian secularism (Evolvi 2025) can explain how actors adapt to a secular environment, but posit that religion should provide ethical and moral resources for action. This is something explored in-depth in the analysis of observations and interviews.

4.3. Anti-Gender Demonstrations and Activists’ Experiences

Participant observations and interviews confirmed the use of Christianity as an ideological resource for anti-gender movements as happens on social media, but suggested a greater centrality of religion in the activists’ lives. Hence, pro-life events, both in Europe and the U.S., usually display Christian symbols and frequently mention religion both in slogans and speeches. For example, in June 2024, I attended the March for Life (Manifestazione per la Vita) in Rome, Italy, where CitizenGO was among the organizing partners. The march featured Catholicism prominently, something that can be partially explained by the proximity to the Vatican and the important role of Catholicism in Italian society. However, what differs from social media narratives is that the event had a clear religious character: speeches were mostly centered around Catholicism, and it seemed implied that all participants were Catholic. The event ended with a Christian rock concert and the organizers visited St Peter’s Square the next day, a Sunday, with a March for Life banner to the attention of Pope Francis. Furthermore, I spoke with participants and found that, alongside members of the Catholic clergy, many were part of Catholic groups such as the Neocatechumenal Way, a lay spiritual path within Catholicism that emphasizes family values. Indeed, several participants mentioned that they knew of anti-gender and pro-life movements through their parishes and their priests.

The interviews with activists confirmed that religion is not only their main motivation for action, but that they were socialized to activism within religious milieus. For instance, Claudio (which is a pseudonym, like the others mentioned in this article) is an Italian physician who is active in local and national pro-life groups, both as a primary care doctor and private citizen. His pro-life activism started when he attended a Catholic university, where one of his professors openly supported anti-gender ideas. In addition, Claudio discussed how Catholicism was his main reason for becoming an activist:

The religious motivation has been very, very important from the very beginning, because my reference, let us say in cultural and spiritual terms, is Mother Theresa of Calcutta […] So, I am convinced that the cultural and social basis [of the pro-life movement] are absolutely secular and everybody can share them, just by looking at objective facts. But the motivations, those who are triggers for engagement and especially for continuing the action, in this context that is not always very welcoming [to pro-life activists], […] you need motivations that need to be supernatural, otherwise people will just let it go.(personal communication, 14 November 2024, translation by the author)

Throughout the interview, Claudio discussed how his faith (and connections with some saints like Mother Theresa) motivated him to become an activist, as he wanted to help the weakest in society, starting from unborn children. Interestingly, Claudio repeats a concept also found on social media, the idea that anti-gender activists are often “unwelcome” by (secular) society. However, the dichotomy between Catholicism and secularism is not as clear-cut as presented on CitizenGO’s Instagram, because Claudio presents the basis of the pro-life movement as “absolutely secular”. In his view, his activism is based on non-religious “objective facts”, but the passion and tenacity to pursue his goals derive from his religious “supernatural motivations”, which make him a more engaged activist. Similar to the experience of Claudio, Juan, a Spanish physician, also reported that faith is central to his pro-life activities and his professional life, because being Catholic helps him better care for patients.

Interviewees frequently used the term “social justice” (or equivalent in other languages) to discuss their engagement. For the Italian Manuela, pro-life activism goes together with other efforts that are frequently shared by anti-gender groups, such as actions against euthanasia and in favor of disabled people. A mother of six adult children, among whom one is severely disabled and non-verbal, Manuela is a member of several anti-gender groups, including the Italian Prolife Insieme, which is directly connected to CitizenGO. She came into contact with anti-gender ideologies through her parish, and after a concert of a singer supporting anti-gender groups, Povia. Like Claudio, Manuela mentioned how Catholicism provides her with strength for action:

One of the biggest problems [today] is superficiality, which is very common, and unfortunately, among young people, […] this concept [superficiality] is different from having Christian charity towards Christian precarity, that sensibility, and that attention, and that care for other people where you see the other person like yourself. […] This allows you to understand that if you are that child [the fetus] who is only two weeks old, but already feels pain, would you like people to take you outside [from the uterus] and cut you into pieces?(personal communication, 11 November 2024, translation by the author)

This quote was mentioned while Manuela was describing her experience as a mother of a disabled son: she needs to feel empathy (which she calls “Christian charity”) with him to understand what he needs, as he cannot express himself. According to her experience, the Catholic faith helps empathize with those who suffer, including elderly and severely ill or disabled people. This is why Manuela stands against abortion (also in the case of a disabled child) and against euthanasia. The image she offers when discussing abortion is crude and reminiscent of what is found on social media, as she mentions fetuses being “cut into pieces”, suggesting that ending a pregnancy is akin to murder. But in this case, her discussion is more nuanced than that found on CitizenGO’s Instagram page: for her, abortion is not simply wrong because it is about “death”, but also because her “Christian charity” helps her empathize with the weakest in society, like unborn babies. It is worth noticing how she does not express sympathy with pregnant people who seek abortions: this might be explained by the interviewees, as well as speakers at Marches for Life, who share their experiences of abortions or miscarriages as deeply traumatic. From this perspective, pro-life activism is perceived as a way of “saving” people from the potential negative impact of choosing an abortion instead of parenthood.

The interviewees’ experiences often pointed to an all-encompassing Catholicism that functions as a moral guide for action. Often, they consumed social media like CitizenGO’s Instagram page and quoted images and ideas that can be found online, but generally, the Internet was not their main place of socialization. On the contrary, both participants in the demonstrations and interviewees mentioned that they had become activists through Catholic milieus. In terms of communication, they tended to communicate with like-minded people and fellow activists via closed groups like WhatsApp and Telegram. One interviewee, Veronica, attributed the success of the pro-life movement she is part of to a chat with people who are considering abortions, implemented on the organization’s website. Activists’ ideas, as reported in the interviews, did not diverge from what is found online, but they displayed a more nuanced attitude toward secular culture: instead of a sharp “Christian vs. secular” dichotomy, they tended to see themselves as engaged activists and empathetic people because of their faith, in a secular world that they perceive as lacking compassion. In this sense, this is a further confirmation of a Christian secular (Evolvi 2025) attitude, where activists are aware of their secular interlocutors, but consider their religion as the main source for inspiration and action. The analysis of social media combined with that of interviews and observations offers a complex picture of anti-gender movements, which provokes discussions on the role of religion and the secular today.

5. Discussion: Connecting Actors, Creating Threats, and Providing Care

Instagram posts and interactions with activists show that religious-related narratives might be more nuanced than often estimated, as they can assume various nuances in offline settings compared to online ones. Regarding the first sub-question, it seems that CitizenGO’s discussion of religion on social media is frequently connected to the communication of the group’s core ideas in an activist context. Hence, CitizenGO shares calls to action and pictures of campaigns, including online petitions and buses with slogans, as discussed in previous literature (Cordoba Vivas 2023; Katsiveli and Coimbra-Gomes 2020). CitizenGO’s Instagram has an emotional, aggressive, and ironic style, as in the case of the satirical meme I analyzed in this article, which confirms the Internet as a space of creative action for this group (Graff 2016).

Concerning the use of religion in Instagram posts, the quantitative analysis showed similar results to the analysis of Righetti et al. (2025), which discovered that CitizenGO’s social media pages mostly focus on anti-gender narratives, but approximately 18.4% of the accounts that share the group’s URL with high frequency are religious in scope (p. 14). The use of hashtags like #Christian and mentions of religion in relation to other topics, like pro-life activism, might suggest that CitizenGO is indeed interested in receiving attention from religious accounts, and engaging them to action alongside other actors in a form of transcalar activism (Kalm and Meeuwisse 2023). In this sense, transcalar activism operates against the liberal international order as activists propose a model based on nostalgia for a conservative religious model of family that is allegedly under attack because of the secular developments of Western culture. However, from the analysis of CitizenGO’s Instagram, the use of strategic secularism (Engelke 2009) appears clear, as the language used is predominantly secular and likely targeting a secular audience. It may be that groups like CitizenGO employ strategic secularism to appear as legitimate actors in a secular public sphere.

Online, religion is mostly talked about in general terms, with references to “Christianity” and “God” rather than Catholicism or specific congregations, or mentions of religious leaders. This might be because the use of religion aims at creating a dichotomy between anti-gender activists and a secular society perceived as hostile. In discussing Islam as dangerous, as in the post on religious violence, CitizenGO shows an Islamophobic attitude shared with far-right parties (Norocel and Giorgi 2022). However, the page’s focus is on the perceived victimization of Christian activists by secular culture, as illustrated by the posts on the arrests following the Paris Olympic protests and on the accusation of Finnish politician Räsänen. In this regard, the use of religion online fits the model of Griera et al. (2021): Christianity is used in the function of morality politics to create moral panic about governmental policies concerning issues like abortion while offering a frame for collective identities. Therefore, in digital narratives, secularism is negatively connoted because it incarnates the perceived threat of gender ideology (Butler 2024; Graff and Korolczuk 2021) and because anti-gender groups engage in a general rejection of secular modernity (Botelho Moniz and Brissos-Lino 2024).

Addressing the second sub-question, the role of religion seems to be central for activists, and religious institutions are often the primary agents of people’s socialization within anti-gender groups. Hence, interviews and participant observations confirm the arguments of scholars highlighting the importance of religion for anti-gender groups (Case 2019; Garbagnoli 2016). It is worth remarking, however, that my fieldwork also points to the heterogeneity of contemporary Christianity (and, given that the focus of my research, Catholicism). It appears clear that anti-gender groups do not necessarily engage all Catholics or have the approval of the entire clergy. For example, the March for Life in Rome ended with activists bringing a banner to the Pope’s mass in St Peter’s Square, thus implying that their actions need to be made visible to other Catholics who are not activists yet.

Religion, for activists, seems to be connected to caring responsibilities, either for children or for those in need in the community (like elderly, disabled, or sick people). In this sense, the study by Avanza (2020) on pro-life women shows how people engaged in these groups can hold intersectional and complex identities linked to their willingness to help others in local or domestic settings, alongside their aggressive stances against abortion or LGBTQ+ people. Hence, the interviewees’ experiences appeared more nuanced than narratives found on CitizenGO’s Instagram page. Mirroring social media, interviewees often created a dichotomy between Christian faith and secularism, and reproduced crude and fearsome images that equate, for instance, abortion with murder. However, as exemplified by Claudio’s quote, they tended to see faith as something that made them “better” activists, in terms of being empathic, caring, and persistent, while also recognizing the potential secular character of their ideologies and activism. In this sense, they bring together secular and religious values in their activist experience, which can be defined as strategic secularism (Vaggione 2005). In addition, their attitude can be described with the framework of Christian secularism (Evolvi and Gatti 2021) because they do not simply merge secular and religious ideas, nor do they want to dismantle or openly criticize secular institutions. Rather, they recognize and interact with secular institutions wishing they were permeated by Christian values.

The lack of nuances in Internet narratives can be explained by the populist character of social media (Gerbaudo 2018). Hence, digital culture tends to oversimplify complex situations for the sake of visibility and Internet circulation, thus overlooking activists’ perceptions and experiences. The fact that the activists I interviewed followed anti-gender groups online but mostly used platforms like WhatsApp to communicate with each other, suggests that social media pages might not aim at directly recruiting and engaging people. Rather, social networks function as venues for public communication, and this might be why they do not respond to everyday users’ comments. Even if they criticize the “elites” in a populist manner, CitizenGO’s online narratives probably aim at the attention of established media and political actors, glued together in an instance of transcalar activism (Kalm and Meeuwisse 2023). Similarly, CitizenGO’s relatively limited focus on religion, despite its centrality in offline demonstrations and activists’ socialization, might aim at presenting the group not as a religious group, but as an activist movement that can dialogue with and gain the attention of secular institutions, as per the perspective of strategic secularism.

6. Conclusions

This article focused on the group CitizenGO’s digital media narratives and the experiences of activists engaged with its ideologies to analyze the role of religion for anti-gender mobilizations online and offline. An analysis of Instagram posts combined with qualitative observations and interviews suggests that CitizenGO does not focus only on the role of religion in online narratives, but uses the term “Christianity” mainly to discuss religious freedom and the (negatively perceived) role of secularism, and social media might not be the main venue of the activists’ recruitment or religious discussions. Rather, people tend to get involved with anti-gender actions and ideologies because they already hold a deep faith and help their communities through caring responsibilities, and Catholic milieus serve as a place of socialization and organization.

I argue that CitizenGO’s actions and narratives constitute an example of Christian transcalar activism, a term inspired by the theory of transcalar activism (Kalm and Meeuwisse 2023). Hence, CitizenGO organizes national and transnational actions where diverse actors come together through a conservative agenda regarding gender and family matters. In so doing, while not being tied to Christian institutions, their claims are based on Christian (and, specifically, Catholic) values. These values function as a glue that offers a shared identity to a fluid network of actors involved in causes like pro-life and anti-LGBTQ+ activism, petitions for religious freedom, and actions to support free speech. In this network, religious groups, churches, and parishes are the actors that tend to organize religious people at the local level and put them in contact with larger national or international networks, thus holding a fundamental role that is, however, not evident from social media.

The concept of Christian transcalar activism is useful to understand certain religious attitudes toward secularism. In an instance of Christian secularism, CitizenGO implies that Christian values should be considered and used as resources in relation to secular happenings, be they national politics or international events like the Olympic Games. In so doing, CitizenGO does not directly contribute to the visibility or the growth of Christian denominations, as this is not its main aim. Rather, it uses religion as a way of recruiting participants and engaging them in anti-gender activism, as happens with the Marches for Life. The present article focused on one group only—CitizenGO—and on Catholic activists; therefore, future research might engage with different anti-gender mobilizations and people from other faiths or organizations. Nonetheless, the results offer a nuanced account of how a group like CitizenGO approaches religion, suggesting that reflections on secularism should consider the increasing importance of religion in mobilizing people. Anti-gender groups are indeed fundamental to understanding the contemporary role of religion, even if they do not contribute to the numerical growth of congregations and appear disjointed from religious institutions. Hence, religion is present in new political and social arenas, which are the venues where religious people become activists.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska Curie grant agreement No. 101105541—Project 2023_MSCA_MERGE_SPS.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Comitato di Bioetica) of the University of Bologna (protocol code 0070251, 12 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in AMSACta at DOI 10.6092/unibo/amsacta/8561.

Acknowledgments

I thank: first and foremost, my project supervisor, Alice Mattoni from the University of Bologna. My research greatly benefited from the mentorship of Nabil Echchaibi and Stewart Hoover, as well as the inputs of the fellows of the Center for Religion, Media, and Culture at the University of Colorado Boulder, U.S., where I was a fellow during the drafting of the article. I am also extremely grateful to my mentor Míriam Díez Bosch, who helped me connect with anti-gender activists during my stay at the Blanquerna Observatory of Media, Religion, and Culture at Ramon Llull University in Barcelona, Spain. Earlier versions of this article have been presented at the American Academy of Religion conference held in November 2024 in San Diego, U.S., and the International Society for the Sociology of Religion conference held in July 2025 in Kaunas, Lithuania; on both occasions, I received relevant feedback that I incorporated in the final manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author used Python for the purposes of collecting Instagram data, analyzing them, and creating Figure 1 and Figure 2. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Asad, Talal. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity, 1st ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Avanza, Martina. 2008. Comment faire de l’ethnographie quand on n’aime pas «ses indigènes»? Une enquête au sein d’un mouvement xénophobe. In Les Politiques de L’enquête. Edited by Alban Bensa and Didier Fassin. Paris: La Découverte. Available online: http://www.cairn.info/politiques-de-l-enquete---page-41.htm (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Avanza, Martina. 2020. Using a Feminist Paradigm (Intersectionality) to Study Conservative Women: The Case of Pro-Life Activists in Italy. Politics & Gender 16: 552–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, Philliip M., and Kristina Stoeckl. 2024. The Global Fight Against LGBTI Rights. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera-Blanco, José, Monica Cornejo, and José Ignatio Pichardo. 2023. Indirect Path to Power The Far-Right Catholic Agenda in Spain. In The Christian Right in Europe: Movements, Networks, and Denominations, 1st ed. Edited by Gionathan Lo Mascolo. Edition Politik. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, vol. 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, Rajeev. 2014. How Secular Is European Secularism? European Societies 16: 329–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho Moniz, Jorge, and José Brissos-Lino. 2024. Religious Populism in Portugal: The Cases of Chega! And CDS—People’s Party. Análise Social 59: 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Judith. 2024. Who’s Afraid of Gender? London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, Jose. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Case, Mary Anne. 2019. Trans Formations in the Vatican’s War on ‘Gender Ideology’. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 44: 639–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmán, Violeta. 2025. Transnational Tactics and National Pushback: The Two-Level Strategy of Anti-Gender Movements in Latin America. Politikon: The IAPSS Journal of Political Science 59: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoba Vivas, Gabriela. 2023. The ‘Free Speech Bus’: Making ‘Gender Ideology’ Appear through Media and Performance. Journal of Lesbian Studies 28: 425–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, Monica, and José Ignatio Pichardo Galán. 2017. From the Pulpit to the Streets: Ultra-Conservative Religious Positions Against Gender in Spain. In Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing Against Equality. Edited by Roman Kuhar and David Paternotte. London: Rowman & Littlefield International. [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, Tobias. 2022. Defenders of the Faith? How Shifting Social Cleavages and the Rise of Identity Politics Are Reshaping Right-Wing Populists’ Attitudes towards Religion in the West. Religion, State and Society 50: 532–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 2002. Europe: The Exceptional Case. Parameters of Faith in the Modern World. London: Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 2023. Revisiting Secularization in Light of Growing Diversity: The European Case. Religions 14: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pittà, Maurizio, and Rita De Santis. 2005. Rome, Italy: The Lexicon–An Italian Dictionary of Homophobia Spurs Gay Activism. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education 2: 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cristofaro, Matteo. 2023. Corpus Approaches to Language in Social Media. London: Routledge. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Corpus-Approaches-to-Language-in-Social-Media/Cristofaro/p/book/9781032125701 (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Engelke, Matthew. 2009. Strategic Secularism: Bible Advocacy in England. Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice 53: 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evolvi, Giulia. 2022. The Theory of Hypermediation: Anti-Gender Christian Groups and Digital Religion. Journal of Media and Religion 21: 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evolvi, Giulia. 2023. The World Congress of Families: Anti-Gender Christianity and Digital Far-Right Populism. International Journal of Communication. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/13522 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Evolvi, Giulia. 2025. ‘I Am a Woman, I Am a Mother, I Am Italian, I Am Christian’: Religious Polarization in the Discourses of Contemporary Far-Right Politics. In Religious Diversity in Post Secular Societies. Edited by Zakaria Sajir and Rafael Ruiz Andrés. Cham: Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/9783031838149 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Evolvi, Giulia, and Mauro Gatti. 2021. Proselytism and Ostentation: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the European Court of Human Rights’ Case Law on Religious Symbols. Journal of Religion in Europe 14: 162–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2013. Critical Discourse Analysis and Critical Policy Studies. Critical Policy Studies 7: 177–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, Sara R. 2017. In the Name of Women’s Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Frisina, Annalisa. 2010. Young Muslims’ Everyday Tactics and Strategies: Resisting Islamophobia, Negotiating Italianness, Becoming Citizens. Journal of Intercultural Studies 31: 557–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbagnoli, Sara. 2016. Against the Heresy of Immanence: Vatican’s ‘Gender’ as a New Rhetorical Device Against the Denaturalization of the Sexual Order. Religion and Gender 6: 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Martín, Joseba, Cecilia Delgado-Molina, and Mar Griera. 2023. ‘I’m Going to Do Battle… I’m Going to Do Some Good’. Biographical Trajectories, Moral Politics, and Public Engagement among Highly Religious Young Catholics in Spain and Mexico. Sociology Compass 17: e13091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2018. Social Media and Populism: An Elective Affinity? Media, Culture & Society 40: 745–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, Alberta, and Stefania Palmisano. 2020. Women and Gender in Contemporary European Catholic Discourse: Voices of Faith. Religions 11: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, Philip S., Samuel L. Perry, and Jemar Tisby. 2022. The Flag and the Cross: White Christian Nationalism and the Threat to American Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graff, Agnieszka. 2016. ‘Gender Ideology’: Weak Concepts, Powerful Politics. Religion and Gender 6: 268–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, Agnieszka, and Elzbieta Korolczuk. 2021. Anti-Gender Politics in the Populist Moment. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Griera, Mar, Julia Martínez-Ariño, and Anna Clot-Garrell. 2021. Banal Catholicism, Morality Policies and the Politics of Belonging in Spain. Religions 12: 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, Lauren Horn. 2024. How #Trad Catholics Challenge Current Constructions of Christian Nationalism: Counter-knowledge, Masculinity, and Elite Aesthetics on Instagram. Journal of Media and Religion 23: 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, Conrad, Marcin Stonawski, Yunping Tong, Stephanie Kramer, Anne Shi, and Dalia Fahmy. 2025. 10. Religion in Europe. Pew Research Center. June 9. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2025/06/09/religion-in-europe/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Harsin, Jayson. 2018. Post-Truth Populism: The French Anti-Gender Theory Movement and Cross-Cultural Similarities. Communication, Culture and Critique 11: 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunklinger, Michael, and Katharina Limacher. 2025. ‘Your Identity Is, What God Puts into You’—Christian Online Activism on Gender and Sexuality Politics on TikTok. Frontiers in Political Science 7: 1501105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalm, Sara, and Anna Meeuwisse. 2023. Transcalar Activism Contesting the Liberal International Order: The Case of the World Congress of Families. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 30: 556–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasselstrand, Isabella. 2022. Secularization or Alternative Faith? Religion 53: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiveli, Stamatina, and Elvis Coimbra-Gomes. 2020. Discursive Constructions of the Enemy Through Metonymy. The Case of CitizenGo’s Anti-Genderist E-Petitions. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Korolczuk, Elżbieta, and Agnieszka Graff. 2018. Gender as ‘Ebola from Brussels’: The Anticolonial Frame and the Rise of Illiberal Populism. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 43: 797–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhar, Roman, and David Paternotte, eds. 2017. Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing against Equality. London: Rowman & Littlefield International. [Google Scholar]

- Lavizzari, Anna. 2019. Protesting Gender: The LGBTIQ Movement and its Opponents in Italy, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lavizzari, Anna, and Andrea L. P. Pirro. 2023. The Gender Politics of Populist Parties in Southern Europe. West European Politics 47: 1473–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavizzari, Anna, and Massimo Prearo. 2018. The Anti-Gender Movement in Italy: Catholic Participation between Electoral and Protest Politics. European Societies 21: 422–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidig, Eviane. 2023. The Women of the Far Right: Social Media Influencers and Online Radicalization. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Machin, David, and Andrea Mayr. 2012. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction, 1st ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, Rita, Nicola Righetti, Susanna Pagiotti, and Anna Stanziano. 2022. Right-Wing Populism and Political Instrumentalization of Religion: The Italian Debate on Matteo Salvini’s Use of Religious Symbols on Facebook. Journal of Religion in Europe 30: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norocel, Ov Cristian, and Alberta Giorgi. 2022. Disentangling Radical Right Populism, Gender, and Religion: An Introduction. Identities 29: 417–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, Elayne. 2012. The Crucifix as a Symbol of Secular Europe: The Surprising Semiotics of the European Court of Human Rights (Respond to This Article at http://www.therai.org.uk/at/debate). Anthropology Today 28: 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepicelli, Renata. 2010. Does Islam Threaten Secularism? Some Remarks Concerning Europe, Islam and Islamic Feminism. Filosofia Politica 3: 413–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righetti, Nicola. 2016. Watching over the Sacred Boundaries of the Family. Study on the Standing Sentinels and Cultural Resistance to LGBT Rights. Italian Sociological Review 6: 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righetti, Nicola, Aytalina Kulichkina, Bruna Almeida Paroni, Zsofia Fanni Cseri, Sofia Iriarte Aguirre, and Kateryna Maikovska. 2025. Mainstreaming and Transnationalization of Anti-Gender Ideas through Social Media: The Case of CitizenGO. Information, Communication & Society 28: 2658–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, Ellen. 2019. Unraveling the Anti-Choice Supergroup Agenda Europe in Spain A Case Study of CitizenGo and HazteOir. IERES Occasional Papers Transnational History of the Far Right Serie. 4. Available online: https://www.illiberalism.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IERES-papers-4-Oct-2019.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Sajir, Zakaria, and Rafael Ruiz Andrés, eds. 2025. Religious Diversity in Post Secular Societies. Cham: Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/9783031838149 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Salvati, Marco, Valerio Pellegrini, Valeria De Cristofaro, and Mauro Giacomantonio. 2024. What Is Hiding behind the Rainbow Plot? The Gender Ideology and LGBTQ+ Lobby Conspiracies (GILC) Scale. British Journal of Social Psychology 63: 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, Iris B. 2024. ‘The Anti-Woke Academy’: Dutch Far-Right Politics of Knowledge About Gender. Politics & Gender 21: 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]