Abstract

This article examines the sacred narrative traditions surrounding Nūr Atā, a small town in present-day Uzbekistan, to explore how Muslim communities in Central Asia expressed their religious history. Drawing on seven manuscripts preserved at the Beruni Institute of Oriental Studies in Tashkent, six in Persian and one in Turkic, the study identifies two distinct traditions that portray the town’s sanctity through prophetic miracle stories, hadith transmission chains, and Sufi cosmology. It explores how narrative form, linguistic variation, and intertextual references shape distinct devotional and historiographical claims. The topics addressed include the relationship between sacred narrative and historiography, the role of ritual practice in sacralizing space, and the textual transmission of spiritual authority. The sacred history of Nūr Atā offers a compelling vision of the town’s religious significance, communicated through both the content and structure of its narratives. These accounts position the town not merely as a local pilgrimage site but as a locus of divine favor embedded within the sacred geography of Islam. By linking the Prophet’s Miʿrāj, angelic testimony, and Sufi initiatic traditions to the landscape of Nūr Atā, the texts construct a genealogy of sanctity that aligns the local with the universal. In doing so, they articulate a vision of communal identity rooted in divine election, prophetic blessing, and spiritual legitimacy. The case of Nūr Atā thus underscores the need to treat sacred narratives, pilgrimage guides, and genealogical traditions as forms of historiography in their own right. These sources do not merely supplement court chronicles or administrative histories; they constitute vital modes through which Central Asian Muslim communities preserved collective memory, asserted religious authority, and inscribed themselves within the broader landscape of the Islamic world.

1. Introduction

This article examines the sacred narrative traditions of Nūr Atā, a small town in present-day Uzbekistan, as a case study for understanding local Islamic historiography in Central Asia. While court chronicles and administrative histories have long dominated the study of the region’s past, less attention has been paid to genres of religious storytelling, particularly pilgrimage guides, miracle narratives, and genealogical traditions, which communities used to articulate their spiritual significance and historical legitimacy. By treating these sacred histories as valuable historiographical sources, this study seeks to expand our understanding of how Muslim communities in Central Asia recorded, imagined, and authorized their past.

Focusing on seven manuscript copies held at the Beruni Institute of Oriental Studies in Tashkent, the article identifies and analyzes two distinct narrative traditions that sanctify Nūr Atā through different strategies. One tradition relies on prophetic miracle stories, formal chains of hadith transmission, and explicit ritual prescriptions to establish the site’s legitimacy within Islamic orthodoxy. The other employs Sufi cosmology, mystical allegory, and esoteric symbolism to present Nūr Atā as a locus of spiritual illumination and initiatic knowledge. These differences reveal not only diverse textual genealogies but also competing visions of religious authority and practice.

By analyzing these manuscripts in detail, the article argues that sacred histories functioned as vital forms of historical consciousness, embedding local geography into the universal framework of Islamic cosmology while offering communities a means of asserting spiritual authority and communal cohesion. Far from being dismissed as mere folklore or legend, these texts demonstrate how Muslim communities in premodern Central Asia negotiated questions of legitimacy, continuity, and belonging against the backdrop of Russian conquest.

The article proceeds in four sections. First, it situates Nūr Atā historically and geographically within Central Asian pilgrimage culture. Second, it describes the manuscript corpus and identifies its two major narrative families. Third, it offers annotated translations to illustrate the distinct rhetorical strategies at work. Finally, it considers the implications of these findings for understanding Islamic historiography, ritual practice, and the negotiation of communal authority in premodern Central Asia.

Nestled within the rugged folds of the Nūr Atā mountain range, a perennial spring has long drawn travelers, mystics, and merchants journeying along the great Silk Road. By day, caravans paused to water their camels beneath its clear, flowing waters; by night, pilgrims whispered tales of divine light shimmering across its surface; visions said to rival even the splendors of Heaven itself. In these stories, Nūr Atā appears not merely as a resting point on a dusty road, but as a threshold between worlds: a site where prophetic miracles, angelic presence, and Sufi illumination converge.

In Central Asian historiography, sacred histories that celebrate the divine origins and blessings of particular towns, often situated along major trade routes, emerged as an important genre, frequently serving as guides for pilgrims.1 Although these narratives are sometimes dismissed as unreliable or legendary, they offer a valuable lens into the social fabric of these communities and the ways in which local populations imagined their towns as part of a religious geography rooted in the Islamic worldview. Far from being mere folklore, these texts construct a complex vision of communal identity, portraying towns as legitimate and sacred entities within the broader Muslim world. They emphasize divine blessings, historical continuity, and sacred topography as markers of shared honor and spiritual significance. In doing so, sacred histories inscribe these localities into a sacred Islamic universe through both geography and historical narrative. Before the Russian conquest and the subsequent reshaping of territorial boundaries and identities, such narratives played a critical role in articulating local and regional belonging among the sedentary populations of Central Asia. They served not only as manifestations of religious devotion but also as tools for asserting communal legitimacy and historical rootedness in a rapidly changing world.

At the heart of these narratives lies a dynamic interplay between Islamic cosmology, Sufi metaphysics, and regional memory, which is vividly illustrated in the sacred history of Nūr Atā. In this article, I explore the narrative traditions that construct Nūr Atā, a town in present-day Uzbekistan, framing it within a broader discourse of sacred geography and spiritual guardianship. I focus in particular on two distinct manuscript traditions, which offer different yet complementary visions of the town’s sanctity: one grounded in prophetic authority and miraculous transmission chains, and the other infused with Sufi symbolism, mystical knowledge, and spiritual illumination.

Nūr Atā is a small town in the Navai province of modern Uzbekistan. According to local oral traditions, its foundation is ascribed to Iskandar Dhū’l-Qarnayn.2 Situated on the Silk Road, Nūr Atā long served as a hub of trade, scholarship, culture, and religion, its citadel forming a secondary gateway to Bukhara and Samarqand after Jizzakh. Other accounts suggest the town’s name derives from a ninth-century figure, Abu’l Ḥasan Nūrī, though this appears to be a misassociation with the celebrated Khurāsānī Sufi Abu’l Ḥasan Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Baghawī (d. 907),3 who lived in Baghdad and has no documented ties to Central Asia.

The earliest known mention of Nūr Atā appears in Narshakhī’s tenth-century History of Bukhara, in which he lists Nūr among the ancient villages around Bukhara, alongside Kharqān Rū, Vardāna, Tarāvcha, Safna, and Īsvāna, and describes it as “a large place with a grand mosque. It has many ribāṭs.4 Every year the people of Bukhara and other places go there on pilgrimages. The people of Bukhara take great pains in this deed. The person who goes on the pilgrimage to Nūr has the same distinction as having performed the pilgrimage (to Mecca). When he returns the city is adorned with an arch because of returning from that blessed place. This Nūr is called the Nūr of Bukhara in other districts. Many of the followers of the Prophet are buried there” (al-Narshakhī 1954, pp. 12–13).

Building on the accounts of both Narshakhī and Yāqūt (d. 1229) (Yāqūt 1866–1870, vol. 3, p. 225), Barthold emphasizes that Nūr’s strategic location and strong fortifications made it a critical military site, often chosen as a defensive stronghold during times of siege (Barthold 1928, pp. 114, 119, 257, 270 and 408). The Akhbār al-dawla al-Saljūqiyya, a thirteenth-century abridgement of Ṣadr al-Dīn al-Ḥusaynī’s Zubdat al-tawārīkh,5 identifies “Nūr-i Bukhara” as the residence of Saljuq princes Amīr Mīkāʾīl, Amīr Mūsā, and Amīr Yabghu (Bosworth 2011, p. 10).6 Muḥammad b. ʿAlī Rāwandī,’ in his early thirteenth-century Rāḥat al-ṣudūr, confirms that Nūr-i Bukhara served as the Saljuqs’ winter residence, with Samarqand functioning as their summer capital following their settlement in Mawarannahr (Ravendi 1957, pp. 85–86).7

It appears that Nūr lost its significance after the Saljuq period and likely fell into decline following the Mongol conquest, only to be revived under the Manghit dynasty, during which it served as a strategic frontier outpost. A governor appointed by the Manghit amir resided there, overseeing the region’s active trade routes. During this period, Nūr begins to appear in narrative traditions as “Nūr Atā,” with the Turkic honorific atā (lit. father) appended to its name, signifying its sanctity.

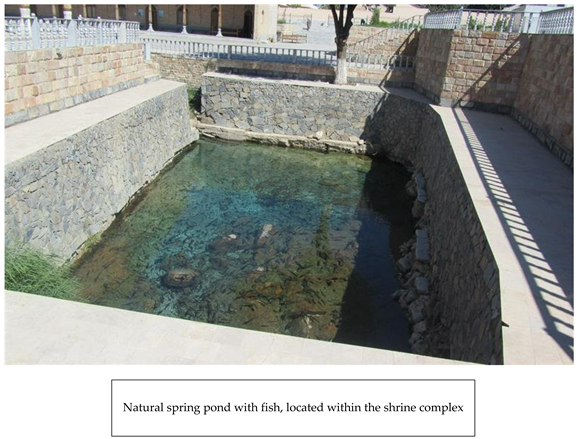

Joseph Castagné, a member of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and likely a French spy in early twentieth-century Central Asia, recorded oral traditions about the sanctity of Nūr Atā and the many virtues associated with visiting the site, traditions that closely echo the narratives examined below (Kastan’e 1917, pp. 37–42). Interest in the site’s historical significance was later revived in 1979, when Uzbek-Soviet archaeologist Ia. Guliamov published the first archaeological survey of Nūr Atā (Guliamov 1979). Guliamov highlighted the importance of the mountain range’s abundant natural springs, suggesting that the town likely developed around a large, perennial spring long regarded as sacred. As will be seen, this spring becomes a central element in the sacred narratives found in the manuscript tradition. Both Castagné and Guliamov also noted the presence of freshwater fish, especially the marinka (Schizothorax spp.), which local tradition holds should not be caught, disturbed, or touched due to their sanctity. These fish remain in Nūr Atā today and continue to be venerated by both locals and visitors (Appendix A).

Alongside the physical site, Nūr Atā’s sacred history survives most vividly in manuscript traditions that both narrate its cosmological significance and prescribe rituals for pilgrims. These texts reveal distinct yet overlapping frameworks for legitimizing Nūr’s sanctity, drawing on prophetic miracle narratives, chains of hadith transmission, Sufi cosmology, and mystical allegory.

2. Narrative Traditions About Nūr Atā

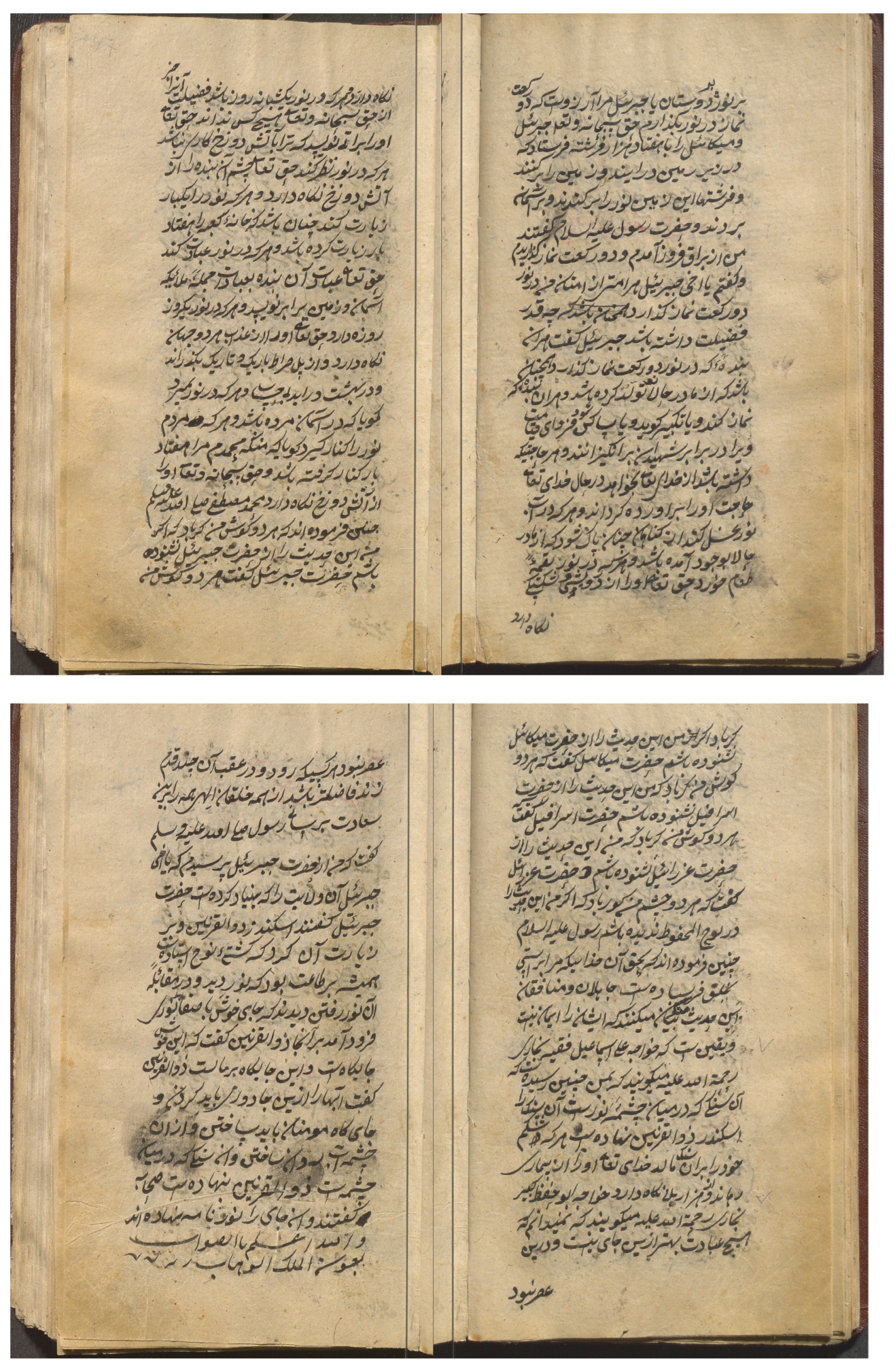

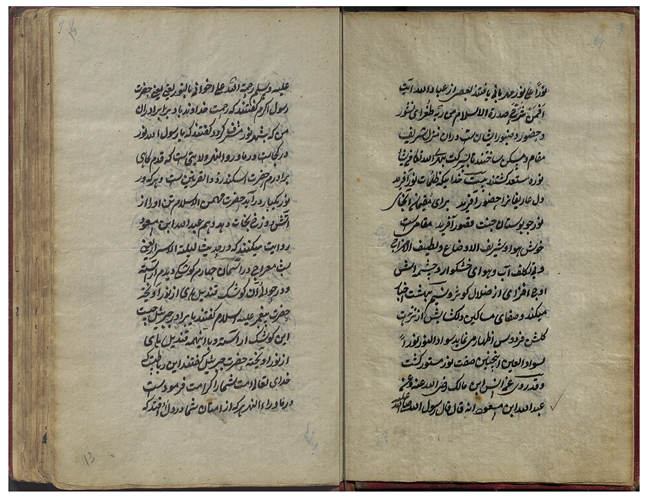

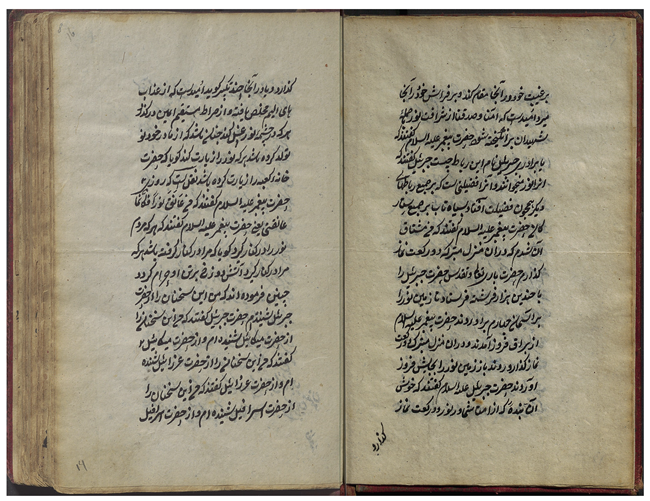

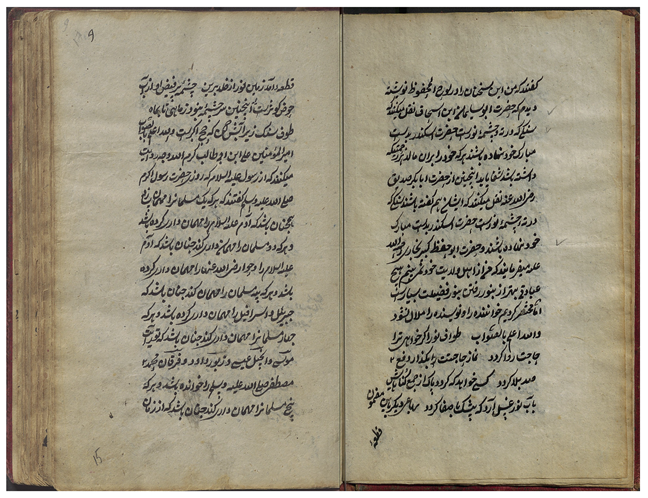

To explore the transmission and transformation of the sacred history of Nūr Atā, I examined seven manuscript copies—six in Persian and one in Turkic—preserved at the Beruni Institute of Oriental Studies (hereafter IVRUz) in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. These include MS 576/5 (ff. 46a–48a) (Jürgen et al. 2002, pp. 189–91), MS 4626/5 (ff. 129b–130b) (Ibid., 191), MS 8149/2 (ff. 13b–17a) (Ibid., 192), MS 9857/2 (ff. 3a–4a) (Ibid), MS 1533 (ff. 25b–27b) (Ibid), 193 and MS 2193/4 (ff. 34b–35a) (Ibid., 195), all in Persian and housed in the Institute’s Main Collection. A seventh manuscript, MS 2462 (ff. 1b–6a), composed in Turkic (Katalog sufischer mentions a publication of the Turkic Risāla-yi Nūr in Kagan in 1906 (and possibly in 1913 in Tashkent), but I have been unable to locate these editions. (Ibid., Jürgen et al. 2002, p. 190)) and held in the Duplicate Collection, has not yet been catalogued. While all seven copies share a broadly similar narrative frame centered on the sanctity of the Nūr Atā shrine, a detailed comparison of their internal structures, stylistic registers, and textual features reveals the existence of two distinct redactional families. Each of these reflects its own priorities in the articulation, preservation, and transmission of Nūr Atā’s sacred history.

The manuscripts not only diverge in terms of narrative length, arrangement, and rhetorical emphasis, but also display significant variation in phrasing and verse usage, offering insight into the shifting textual practices and devotional strategies that shaped these retellings. The philological differences are especially pronounced in the ways the two families handle reported speech, interlinear verse, Qur’anic citation, and chains of transmission. One set of copies tends to offer tightly structured, editorially polished narratives characterized by clear chains of prophetic transmission and detailed ritual prescriptions. The other employs a more expansive, discursive mode of storytelling, marked by a looser syntax, Sufi-inflected terminology, and paraphrastic insertions that point to an underlying oral transmission. These differences suggest not only separate textual genealogies, but also divergent hermeneutical aims.

The first group of narratives includes MS 1533, MS 9857, MS 576, MS 4626, and MS 2462. MS 1533 and MS 576, both undated, are nearly identical, likely derived from the same source, although MS 1533 is notably more polished. MS 9857, dated 1265/1845, presents a condensed version of the same material. MS 4626, also undated and the shortest in the group, closely parallels MS 9857, even preserving the same marginal verses. MS 2462, dated Ṣafar 1317/June 1899, likewise belongs to this first narrative family, distinguished primarily by its composition in Turkic verse.

The second group consists of MS 2193 and MS 8149, both undated, which follow the same narrative sequence but differ in verbal style and elaboration. MS 8149 appears to draw on distinct sources, possibly incorporating oral traditions. Although they stem from a shared tradition, variations in vocabulary, sentence structure, and organization suggest that MS 2193 and MS 8149 are independent redactions rather than direct copies. MS 2193 often uses synonyms and more concise phrasing while preserving the sequence of accounts found in MS 8149. Both manuscripts include identical poetic excerpts, though in reverse order.

By comparing representative copies from each narrative family (MS 576 from the first and MS 8149 from the second), this analysis shows how technical features of the text help shape spiritual message and devotional impact. This comparison sets the stage for two annotated translations, chosen to highlight the different grammar, syntax, and word choices that define each tradition. A summary will follow to provide a broader interpretive view of these two textual families, showing how their different styles of transmission, citation, and claims to spiritual authority shape competing ideas about Nūr Atā’s sanctity. But first, the translations allow us to experience the texts on their own terms, as specific expressions of sacred history and influenced by the language choices of the people who compiled and copied them.

Taking into account that the sacred narrative traditions about Nūr Atā echo Narshakhī’s History of Bukhara, we may suppose that these accounts were in circulation as early as the tenth century and continued to develop through the nineteenth century. Although most of the manuscript copies discussed here are undated, the copy dates of other treatises included in the same codices suggest that the sacred narratives of Nūr Atā were largely produced in the second half of the nineteenth century, possibly extending into the early years of the twentieth century. While the precise circumstances of their formation are difficult to determine, the proliferation of manuscript copies in the late nineteenth century may reflect the heightened sense of communal anxiety following the Russian conquest and the imposition of non-Muslim rule over a predominantly Muslim population. In this context, the renewed effort to record and circulate sacred narratives such as those concerning Nūr Atā can be seen as part of a broader attempt to assert religious identity, preserve historical memory, and reinforce communal cohesion in the face of political and social disruption.

The sacred history of Nūr Atā offers a powerful vision of the town’s religious significance, conveyed through both the content and structure of its narratives. These accounts portray Nūr Atā not merely as a local shrine, but as a site of exceptional divine favor, deeply embedded within the sacred geography of Islam. They reimagine Nūr Atā as a spiritual center in its own right, whose sanctity was affirmed by the Prophet and the archangels. In doing so, they align the local with the universal, anchoring the town’s identity within the broader frameworks of Islamic cosmology and theology. These narratives thus provide valuable insight into how local communities envisioned their religious landscape, constructed sacred genealogies, and articulated communal bonds through the language of divine election and prophetic blessing.

What follows are translations of MS 8149 and MS 576, each selected to represent its respective narrative “family.” These translations closely follow the original wording and structure to reflect the manuscripts’ sentence patterns and style, omitting the standard honorific phrases attached to proper names. Substantive variations in the manuscripts’ wording are recorded in the footnotes.

3. Translation of MS 576

Risāla-yi Nūr8

In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.

ʿAbdullāh b. Masʿūd relates the following from the Prophet:

On the night of the Miʿrāj,9 I reached the fourth Heaven and saw an adorned palace with lanterns of light hanging from it. I said, “O God, what is this light?” A call came: “It is the place of your community, beneath the blue sky and in Mawarannahr.10 They call it Shahr-i Nūr. Whoever from your community dies in Mawarannahr11 will rise among the ranks of the martyrs on the Day of Resurrection.”

The Prophet said: “I asked Jibrīl, ‘What is the name of this place?’” Jibrīl said: “The name of this place is Nūr and it holds great merit for the friends [of God.]”12 [The Prophet:] “O Jibrīl, I lhave a wish to perform two rakʿas of prayer in Nūr.” Almighty God then sent Jibrīl and Mīkāīl, along with seventy thousand13 angels, to descend beneath the earth and uproot it. The angels uprooted this land of Nūr and carried it up to the heavens.14

The Prophet said: “I descended from Burāq15 and performed two rakʿas of prayer. I said, ‘O my brother Jibrīl, what merit does it hold if someone from among my community performs two rakʿas of prayer in Nūr?’”

Jibrīl16 replied:

Every servant who performs two rakʿas of prayer in Nūr will be like one newly born of his mother. Whoever prays, utters the takbīr17 or even remains silently there will rise breast-to-breast with the martyrs on the Day of Resurrection. If anyone has a need to present to Almighty God, He will immediately fulfil it.

Whoever performs ghusl18 in the water of Nūr will be purified of sins like a newborn. Whoever eats a morsel of food in Nūr will be saved from poverty and misfortune. Whoever spends a night in Nūr, its virtue known only to God, will receive an exemption inscribed by Almighty God: “There is no burning waters of Hell for you.”

Whoever gazes upon Nūr will have his eyes spared from hellfire. A single visit to Nūr equals seventy19 visits to the House of the Kaʿba. Whoever worships in Nūr will have that worship recorded as equal to that of all the angels of heaven and earth. Whoever fasts one day in Nūr will be delivered from the agonies of both worlds, will cross the thin, dark bridge over hell, and enter paradise without reckoning. Whoever dies in Nūr, it is as though he died in the heavens. Whoever embraces the people of Nūr will be as though he embraced my Muḥammad seventy times,20 and Almighty God will protect him from the fire of Hell.

Muḥammad Muṣṭafā said: “Both of my ears would be deaf if I had not heard this hadith from Jibrīl.” Jibrīl said: “Both of my ears would be deaf if I had not heard this hadith from Mīkāʾīl.” Mīkāʾīl said: “Both of my ears would be deaf if I had not heard this hadith from Isrāfīl.”21 Isrāfīl said: “Both of my ears would be deaf if I had not heard this hadith from ʿAzrāʾīl.” ʿAzrāʾīl said: “Both of my eyes would be blind if I had not seen this hadith written in the Lawḥ al-Maḥfūẓ.”22

The Prophet then said: “By the God who sent me to the people, the ignorant and hypocrites who deny this hadith truly have no faith.”23

Khwāja ʿAlī Ismāʿīl faqīh Bukhārī reports: “I have heard that the stone in the middle of the spring of Nūr was placed there by Iskandar Dhū’l-Qarnayn. Whoever rubs his belly upon that stone will be freed from illnesses and saved from a thousand24 evils.”

Khwāja Abū Ḥafṣ Kabīr Bukhārī25 says: “I know of no act of worship better than that which takes place at that locality. And in this age, there is nothing like it. Whoever goes there and walks even a few steps behind it will be more virtuous than anyone else. May God grant this blessing to all.”

The Prophet also said: “I asked His Holiness Jibrīl, ‘Brother Jibrīl, who founded that province?’ He replied: ‘Iskandar Dhū’l-Qarnayn visited the place where Nūḥ’s ark came to rest. Ever obedient, he saw the light, followed it, and came upon a beautiful, pure, and radiant place. Upon descending,26 he said, “This is a pleasant place, a land of fairies.” He then ordered that its inhabitants be removed, that a sanctuary for believers be built, and that a spring of flowing water be established. The stone in the spring’s center was set there by Iskandar Dhū’l-Qarnayn.’” The Companions said: “That place was given the name Nūr.”27

- And God knows best what is right, with the help of the Sovereign, the Bestower!

- They lifted the stone to the heavens,

- Named it the Dome of Nūr.

- Muḥammad prostrated upon it,

- From that, it became “Light upon light.”28

4. Translation of MS 8149

Risāla-yi Ḥażrat-i Nūr Atā29

In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.

ʿAbdullāh b. Masʿūd relates the following from the Prophet:

On the night of Miʿrāj, I arrived at the fourth Heaven and saw an adorned palace with lamps of light. I said: “O God, what is this light?” The response came: “The place of your community beneath the Heaven of the world, in the land of Mawarannahr. They call it Shahr-i Nūr. Whoever from your community dies in Mawarannahr will rise among the group of witnesses on the Day of Judgment.” The Prophet states that this account was brought by Jibrīl from the Lord of Glory, “Allah is the Light of the heavens and the earth,”30 and “He created the darkness and the light…”31

Ammā baʿd, let it not be hidden from those versed in knowledge that,32 through the perfect power of His Holiness—the Creator of all creation, glorious is His majesty and boundless His grace—the whole earth was illuminated, as in “And the earth will shine with the light [of its Lord],”33 and all things were brought into existence manifest and apparent. Each portion of the earth was endowed with a radiant dignity. Among those is a luminous place belonging to Ishtīkhān,34 one of the protected territories of Bukhara. It is a flourishing place, preserved from calamities. God Almighty bestowed a light of grace upon it through the footsteps of great Companions, noble scholars, and shaykhs. They found kindness upon “Light upon light.”35 For some servants of God, the verse “What about the one whose heart God has opened in devotion to Him, so that he walks in light from his Lord?”36 is their signature of resurrection, presence, and return. They stayed and settled in that noble place to receive a share of the divine light that God grants to “whoever He wills.”37 The verses:

- God, who created light from darkness,

- Created presence in the hearts of mystics.

- For the dwellers of that Nūr,

- He created palaces like the garden of Paradise.

It is a place of pleasant air, noble conditions, and refined temperament. Simply, its climate is delightful, and its spring flows like a branch of Kawthar,38 carrying the fragrance of Paradise. The purity of its inhabitants reveals the delight of Paradise’s rose garden. “The blackness of light is light, as is the blackness of the eye;” in this way, the true essence of Nūr became veiled.

It is narrated from Anas b. Mālik and from ʿAbdullāh b. Masʿūd, who said:

The Prophet said: “May God’s mercy be upon the brothers in Nūr.” In other words, the Prophet said: “God’s mercy be upon my brothers who are honored to visit the town of Nūr.” They asked: “O Messenger of God, where is Nūr?” [He replied:] “It is a province in Mawarannahr, which is a qadamgāh (“place of the footprint”) of my brother, Iskandar Dhū’l-Qarnayn. Whoever enters Nūr even once, the Protector of Islam (God) will save his body from the fire of Hell.”

And ʿAbdullāh b. Masʿūd narrates:

[The Prophet:] “In the tradition of the Night of Secrets, namely the Night of Miʿrāj, I saw an adorned palace in the fourth Heaven. In the environs of that place, lanterns of light were hanging.” The Prophet said: “O brother Jibrīl, what is this adorned palace with all these lanterns of light hanging around it?” Jibrīl said: “This is the ribāṭ with which Almighty God has favored your community. In Mawarannahr, whoever among your community feels in his heart the desire to settle in that place and dies there in his bed, it is hoped, and we believe and affirm, that by virtue of the nobility of Nūr, he will arise among the martyrs.” The Prophet said: “O brother Jibrīl, what is the name of this ribāṭ?” Jibrīl said: “They call it Nūr. It possesses a virtue so great that it surpasses all other ribāṭs, casting black light upon all the stars.” The Prophet said: “I long to perform two rakʿas of prayer in that noble place.”God sent Jibrīl with several thousand angels to bring the land of Nūr up to the fourth Heaven. The Prophet descended from Burāq and performed two rakʿas of prayer in that noble place. They then returned the land of Nūr to its original place.39

Jibrīl said: “Blessed is the servant from your community who performs two rakʿas of prayer in Nūr or utters a few takbīrs there. It is hoped he will be saved from painful punishments and cross the bridge over Hell securely. Whoever performs ghusl in the spring of Nūr will be as if he has just been born from his mother.40 Whoever visits Nūr, it is as if he had visited the House of the Kaʿba.”

It is narrated that one day the Prophet said: “Embracing Nūr is like embracing me.” In other words, the Prophet said: “Whoever embraces the people of Nūr will likely embrace me. And whoever embraces me, the fire of Hell will be forbidden to touch his body.” He continued: “I heard these words from Jibrīl.” Jibrīl said: “I heard these words from Mīkāʾīl.” Mīkāʾīl uttered: “I heard these words from ʿAzrāʾīl.” ʿAzrāʾīl said: “I heard these words from Isrāfīl.” Isrāfīl said: “I saw these words written in the Lawḥ al-Maḥfūẓ.”41

ʿAbū Sulaymān b. Isḥāq42 narrates: “A stone at the bottom of the spring of Nūr was placed there by the noble hands of Iskandar. Whoever43 rubs himself on it, whatever affliction he may have, he will be healed.” A similar report is attributed to Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq: “A stone at the bottom of the spring of Nūr was placed there by the noble hands of Iskandar.” Abū Ḥafẓ Kabīr Bukhārī says: “I see no greater virtue for the people of my province than visiting Nūr.”

Nūr has many virtues.44 Nevertheless, we have shortened this account so as not to exhaust the reader or the writer. God knows best what is right! (Appendix A)

Circumambulate Nūr if your need will be fulfilled,Perform the prayer of need; let a hundred afflictions be repelled.Whoever seeks to be cleansed of all his sins,Bathe in the water of Nūr, surely, you will be purified.45Another rubāʿī conveying the same meaning:The land of Nūr became a piece of Paradise,Its spring, full of grace, flows from the reservoir of Kawthar.Thus is the spring in Nūr, from the fish to the moon,Circumambulate the stone beneath its waters, for this is the greater pilgrimage.46And God knows best!

MS 576 and MS 8149 represent two distinct narrative families that present Nūr Atā as a divinely chosen and spiritually potent site, deeply embedded in Islamic cosmology and eschatology. MS 576, from the first family of narratives, emphasizes the miraculous transport of the land of Nūr to Heaven and back during the Prophet Muḥammad’s miʿrāj. It portrays Nūr as a celestial territory, linking its sanctity directly to angelic intervention and divine approval. The Prophet’s performance of prayer at Nūr, along with the benefits of visiting, praying, or even gazing upon the site, is described in elaborate detail. The inclusion of prominent jurists such as Khwāja ʿAlī Ismāʿīl Bukhārī and Abū Ḥafṣ Kabīr Bukhārī reinforces the local and scholarly legitimacy of these traditions. In contrast, MS 8149, representing the second narrative family, offers a more philosophical and Sufi-inflected account. It opens with a reflection on divine light and mystical knowledge, presenting Nūr Atā as a site where divine guidance is revealed. The text explicitly connects the site with esoteric knowledge, the hearts of mystics, and the divine light referenced in Qur’anic verses. While the Prophet’s visitation remains central, the account introduces additional layers of allegory and spiritual reflection.

Both narrative families invoke the authority of the Prophet and well-known hadith transmitters to legitimize the sacredness of Nūr Atā. In MS 576, the chain of transmission for the virtues of Nūr includes the Prophet, Jibrīl, Mīkāʾīl, Isrāfīl, and ʿAzrāʾīl, culminating in the Lawḥ al-Maḥfūẓ, thus rooting the account in celestial authority. The Prophet affirms his belief by invoking the authenticity of hadith transmission, which in turn serves to establish the miraculous history of Nūr Atā not merely as local lore but as a divinely validated sacred history. References to early transmitters such as ʿAbdullāh b. Masʿūd and Anas b. Mālik further embed these accounts within the broader Islamic scriptural tradition.

The divergent strategies of these two texts highlight how the figure of the Prophet, whether as the initiator of a transmission chain or as the source of divine illumination, operates as a crucial anchor for the sacral legitimation of Nūr. In both narrative traditions, Nūr’s sanctity is not framed as merely local tradition or regional devotion; rather, it is situated within the broader architecture of Islamic religious authority. By positioning the Prophet within the geography of Nūr, either through hadith-based narration or metaphysical association, these accounts work to historicize the site’s significance, aligning it with the foundational figures and epistemologies of Islamic knowledge production.

MS 576 offers a highly structured account of the ritual practices associated with Nūr, delineating specific acts, such as ablution with the spring water, the performance of two rakʿas of prayer, and lying upon a stone, each linked to distinct eschatological rewards. The text adopts a format reminiscent of sacred historiography, presenting a catalog of blessings that includes healing from illness, relief from poverty, and the promise of paradise. These benefits are explicitly tied to corresponding ritual actions, underscoring the practical and transactional dimensions of engaging with the sacred geography of Nūr. MS 8149, by contrast, situates its ritual prescriptions within a mystical and metaphysical framework. While the same stone recurs as a focal point, its significance is interiorized and reinterpreted. The visitor is instructed to circumambulate and prostrate upon the stone, but the resulting effects are articulated in terms of spiritual illumination and nearness to the divine. In this view, Nūr is not just a place to receive blessings, but a spiritual center where the divine and human realms are believed to meet.

A distinctive feature of the second narrative family is its integration of Sufi terminology and ritual practice. MS 2193 includes a striking detail: Khwāja ʿAbd al-Khāliq Ghijdūvānī, following the instruction of the enigmatic figure Khiżr, descended beneath the spring of Nūr, embraced a stone, and performed dhikr. This passage ties Nūr Atā directly to the foundational legend of the silent dhikr in the Naqshbandī tradition. The invocation of ʿAbd al-Khāliq Ghijdūvānī, a pivotal figure in the Khwājagān-Naqshbandī lineage, transforms Nūr from a site of prophetic visitation into a locus of Sufi initiation. In Naqshbandī hagiographies, the silent dhikr is taught by Khiżr to Ghijdūvānī, marking a spiritual transmission that defines the community’s distinctiveness. By locating this moment at Nūr, the narrative sanctifies the site not merely as a place of pilgrimage, but as the origin of a transformative practice central to one of Central Asia’s most influential Sufi traditions. This framing deepens the spiritual importance of Nūr Atā, inviting pilgrims to see it not just as a holy site, but as a place where they can draw closer to the divine and experience spiritual insight.

Both manuscripts embed the sanctity of Nūr in the mythic figure of Iskandar Dhū’l-Qarnayn. In MS 576, Iskandar is portrayed as a ruler who orders the site cleared, sanctifies the land, and sets a great stone as a lasting marker of holiness. His presence serves to mythologize the foundation of Nūr through an act of historical sanctification. Conversely, MS 8149 presents Iskandar as a spiritual companion of the Prophet, “his brother,” linking the sacred geography of Nūr to the spiritual legacy of divine kingship. The site is described as Iskandar’s qadamgāh, highlighting its role as a liminal space between worldly authority and spiritual elevation. This connection not only historicizes the site but also situates it within a lineage of divinely guided sovereignty.

Both families of renditions conclude with didactic verses that encapsulate and reinforce the spiritual virtues of Nūr, explicitly inviting the reader or visitor to engage in acts of veneration. These verses show the sacred stone not just as a place of miracles but as a powerful symbol at the center of the universe, like the Kaʿba. The poem blends religious rituals with deeper spiritual meaning, portraying Nūr as a place where human worship and divine light meet.

The lines, “They lifted the stone to the heavens, /Named it the Dome of Nūr,” invoke a celestial trajectory, symbolically elevating the stone to a heavenly realm and thereby sanctifying the site as a point of contact between the terrestrial and the divine. The subsequent assertion that “Muḥammad prostrated upon it” further sacralizes the stone by associating it directly with the Prophet’s physical presence, legitimating its sanctity through prophetic precedent. The phrase “Light upon light” resonates with Qurʾanic language (24:35), layering the site with theological depth and emphasizing its embodiment of divine illumination.

The verses go on to prescribe specific ritual actions (circumambulation, prayer of need, and ablution with the spring water) that promise tangible spiritual benefits: approval, protection from evil, and purification from sin. This intertwining of prescribed ritual with eschatological reward underscores the transactional relationship between devotee and sacred site, where physical acts facilitate spiritual transformation. In these verses, Nūr is framed not simply as a geographic location but as a sacred locality where divine light dwells within the hearts of the spiritually awakened. The poetic assertion that God “created palaces like the garden of Paradise” enhances the sanctity of Nūr by positioning it alongside celestial paradises, implying that true spiritual fulfillment is attainable through divine encounter at the site. In other words, these verses both guide visitors on how to honor Nūr and explain why the site is spiritually powerful, showing it as a place where religious practice and divine presence come together.

The comparison of these two versions shows two different ways of expressing devotion in the stories about Nūr Atā. MS 576 focuses on the power of rituals, trusted chains of transmission, and the miraculous qualities of the land. MS 8149, on the other hand, offers a more spiritual view, centered on divine light, chosenness, and symbolic meaning. Both texts aim to present Nūr as a place where people can connect with the divine, showing how Islamic sacred geography in early modern Central Asia allowed for many ways of understanding and experiencing holiness. These stories combine different forms of sacred meaning, using both hadith and Sufi teachings. Whether through visions of the Prophet’s heavenly journey or through Sufi spiritual lineages, they invite people to see Nūr as a place where divine blessings meet the physical world.

In sum, the sacred histories surrounding Nūr Atā offer a compelling lens through which to reconsider the forms and functions of historiographical expression in Central Asia. As the analysis of these manuscript traditions demonstrates, Central Asians articulated the history of their religious communities not solely through court chronicles, but also through genres often categorized as sacred histories, hagiographies, or legends of origin. Such texts operated within a broader epistemological framework in which sacrality, geography, and historical memory were deeply intertwined.

The Nūr Atā narratives position sacred history as both a mode of local self-articulation and a mechanism for integrating peripheral communities into the wider religious geography of the Islamic world. By embedding the town’s origins within the cosmological event of the miʿrāj, invoking chains of prophetic and angelic transmission, and linking the site to Sufi initiatic traditions, these texts construct a layered account of legitimacy that is simultaneously local and universal. In so doing, they assert Nūr Atā’s status not as a marginal or provincial site, but as a locus of divine favor and religious centrality.

The case of Nūr Atā thus highlights the need to treat sacred narratives, pilgrimage guides, and genealogical traditions as forms of historiography in their own right. These sources do not merely supplement “official” histories; they constitute historically meaningful articulations of communal identity, authority, and sacred memory. They anchor local religious communities within both regional and global frameworks of Islamic legitimacy. Taken together, the sacred histories of Nūr Atā exemplify the plural modes through which Muslim communities in Central Asia expressed and preserved their religious pasts. They reveal a historiographical tradition that is at once historically conscious, theologically saturated, and spatially grounded, offering important insights into the ways sacred memory, devotional practice, and historical imagination converged in the making of local Islamic histories.

5. Conclusions

The continued reverence for the sacredness of Nūr Atā among local communities is evident in its enduring presence as a pilgrimage site. Yet, the noticeable decline in the number of visitors over the past decade reflects shifting religious dynamics in the region. Similar trends are evident at other historically significant shrines in Central Asia. This decline, however, does not signify a loss of belief in Nūr Atā’s sanctity. Rather, it points to the growing influence of Salafi currents that view shrine visitation with suspicion or outright condemnation. In this context, sacred sites such as Nūr Atā become arenas where competing visions of Islamic piety, authority, and history are actively negotiated.

The case of Nūr Atā thus prompts a broader reconsideration of how Islamic sacred histories function within both the historical and contemporary religious landscapes. These narratives are not simply relics of premodern imagination; they remain embedded in the collective memory and ritual life of communities, even as they are increasingly questioned by rival visions of Islamic orthodoxy. Their enduring power lies in their capacity to offer not only a vision of the past, but a framework for spiritual belonging, communal identity, and sacred geography that continues to resonate across generations.

By bringing to light the manuscript traditions of Nūr Atā, this article challenges conventional boundaries between historiography, devotion, and local religious practice. It shows that sacred histories are not merely pious tales, but active instruments of historical consciousness, texts through which Central Asian Muslims have articulated claims to divine favor, asserted continuity with foundational Islamic figures, and woven their local sites into the transregional topography of Islamic sanctity. These narratives offer an alternative archive of Islamic history, one grounded not in state authority, but in spiritual lineage, local memory, and ritual engagement. In a moment when debates over the legitimacy of popular piety are intensifying across the Muslim world, the sacred histories of Nūr Atā remind us that the past is not only remembered, but also continuously rewritten at the intersection of belief, space, and power.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| MS 576 (ff. 46a–48a) |

| 47رساله نور |

| بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم |

| عبد الله ابن مسعود رضى الله عنه از حضرت رسول صلى الله عليه و سلم چنين روايت ميكنند كه در شب معراج در آسمان چهارم در رسيدم ديدم كه كوشكى آرسته كرداكرد قنديلها آويخته از نور كفتم الهى اين چه نور است خطاب آمد كه موضع امتان تو است در زير آسمان كبود و در ما وراء النهر كه او را شهر نور كويند و هر كه از امتان تو در ما وراء النهر بميرد در روز قيامت از خيل شهيدان بر خيزد و رسول عليه السلام ميفرمايند كه از حضرت جبرئيل عليه السلام سوال كردم كه نام اين موضع چيست حضرت جبرئيل كفت نام اين موضع نور است و فضيلت است <46b> بر نور بر دوستان يا جبرئيل مرا آرزو است كه دو ركعت نماز در نور بكذارم حق سبحانه و تعالى جبرئيل و ميكائيل را با هفتاد هزار فرشته فرستاد كه در زير زمين در ايند و زمين را بر كنند و فرشته ها اين زمين نور را بر كنند و بر آسمان بردند و حضرت رسول عليه السلام كفتند من از براق فروز آمدم و دو ركعت نماز كذارديم و كفتم يا اخى جبرئيل هر امتى از امتان من در نور دو ركعت نماز كذارد چه قدر فضيلت داشته باشد جبرئيل كفت هر ان بنده كه در نور دو ركعت نماز كذارد همچنان باشد كه از مادر حالا نو تولد كرده باشد و هر ان بنده كه نماز كند و يا تكبير كويد و يا ساكن شود فرداى قيامت ويرا در برابر شهيدان برانكيزانند و هر حاجتيكه داشته باشد از خداى تعالى بخواهد در حال خداى تعالى حاجت او را بر اورده كرداند و هر كه در آب نور غسل كند از كناهان چنان پاک شود كه از مادر حالا بوجود آمده باشد و هر كه در نور لقمۀ طعام خورد حق تعالى او را از درويشى و شكستكى <47a > نكاه دارد و هر كه در نور يكشبانه روز باشد فضيلت آنرا جز از حق سبحانه و تعالى هيچ كس نداند حق تعالى او را براتى نويسد كه ترا آباتش دوزخ كارى نباشد هر كه در نور نظر كند حق تعالى چشمان بنده را از آتش دوزخ نكاه دارد و هر كه نور را يكبار زيارت كند چنان باشد كه خانۀ كعبه را هفتاد بار زيارت كرده باشد و هر كه در نور عبادت كند حق تعالى عبادت آن بنده بعبادات جملۀ ملائكه آسمان و زمين برابر نويسد و هر كه در نور يكروز روزه دارد حق تعالى او را از عذاب هر دو جهان نكاه دارد و از پل صراط باريک و تاريک بكذراند و در بهشت در ايد بى حساب و هر كه در نور بميرد كويا كه در آسمان مرده باشد و هر كه مردم نور را كنار كيرد كويا كه منكه محمدم مرا هفتاد بار كنار كرفته باشد و حق سبحانه و تعالى از آتش دوزخ نكاه دارد محمد مصطفى صلى الله عليه و سلم چنين فرموده اند كه هر دو كوش من كر باد كه اكر من اين حديث را از حضرت جبرئيل نشنوده باشد حضرت جبرئيل كفت هر دو كوش من <47b> كر باد اكر من اين حديث را از ميكائيل نشنوده باشم حضرت ميكائيل كفت هر دو كوش من كر باد كه من اين حديث را از حضرت اسرافيل نشنوده باشم حضرت اسرافيل كفت كه هر دو كوش من كر باد كه من اين حديث را از حضرت عزرائيل نشنوده باشم و حضرت عزرائيل كفت كه هر دو چشم من كور باد كه اكر من اين حديث را در لوح المحفوظ نديده باشم رسول عليه السلام چنين فرموده اند كه بحق آن خدايكه مرا براستى بخلق فرستاده است جاهلان و منافقان اين حديث بيان ميكنند كه ايشان را ايمان نيست و يقين است كه خواجه على إسماعيل فقيه بخارى رحمة الله عليه ميكويند كه بمن چنين رسيده است كه آن سنكى كه در ميان چشمه نور است آن سنک را إسكندر ذو القرنين نهاده است هر كه شكم خود را بران سنک مالد خداى تعالى او را از بيمارى رهاند و از هزار بلا نكاه دارد و خواجه أبو حفظ كبير بخارى رحمة الله عليه ميكويند كه نميدانم كه هيچ عبادت بهتر ازين جاى نيست و درين <48a> عصر نبود هر كسيكه رود و در عقب آن چند قدم زند فاضلتر باشد از همه خلقان الهى همه را برين سعادت برسانى رسول صلى الله عليه و سلم كفت كه من از حضرت جبرئيل پرسيدم كه يا اخى جبرئيل آن ولايت را كه بنياد كرده است حضرت جبرئيل كفتند إسكندر ذو القرنين ... زيارت آن كرد كه كشتى نوح استاده است هميشه بر طاعت بود كه نور ديد و در مقابله آن نور رفتن ديدند كه جاى خوش با صفا نورى فرود آمد بر آنجا ذو القرنين كفت كه اين خوش جايكاه است و اين جايكاه هريانست ذو القرنين كفت آنهارا ازين جا دورى بايد كردن و جايكاه مؤمنان بايد ساختن و ازان چشمه آب سوان ساختن و ان سنكى كه در ميان چشمه است ذو القرنين نهاده است صحابه كفتند و ان جاى را نور نامه نهاده اند و الله اعلم بالصواب بعون الملک الوهاب |

| بسوى آسمان بردند سنكى |

| نهادند نام او را قبه نور |

| ببالايش محمد سجده كرد |

| ازان كرديد او نورا على نور |

| MS 8149 (ff. 13b–17a) |

| رساله حضرت نور اتا رحمة الله |

| بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم |

| عبد الله ابن مسعود رضى الله عنه از حضرت رسول صلى الله عليه و سلم چنين روايت ميكنند كه در شب معراج در آسمان چهارم رسيدم كوشكى ديدم آرسته كرده او را قنديلهاى از نور كفتم آلهى اين چه نور است خطاب آمد كه موضع امتان تو اند در زير آسمان دنيا و در زمين ما وراء النهر او را شهر نور كويند <14a> و هر كه از امتان تو در ما وراء النهر بميرد در روز قيامت از خيل شهيدان بر خيزد رسول عليه السلام ميفرمايند كه از حضرت جبرئيل كه آوردند اين حكايت را حضرت رب العزت و لله نور السماء و الأرض (Q 24:35) و جعل الظلمات و النور (Q 6:1) و الصلوة و السلام علي خير الأنبياء و بالظهور اول المخلوقات بالنور رضوان الله تعالى و على آله و أولاده و خلفاء الى يوم النشور الدين بالحق و رضى الله عنهم الملک المغفور اما بعده اعلام رأى ارباب العلوم پوشيده نماند كه چون از كمال قدرت حضرت خالق البريا جل جلاله و عم نواله سرا و اشرقت الأرض بالنور (Q 39:69) و خلقت الأشياء ظاهرا و هويدا كشت هر قطعه از زمين نور مشرف ارزانى شده و از آن جمله موضعى نورانى متعلقات ایشتیخان از ضمايم محفوظ بلده بخارا است معمور معصومه عن الآفات است الله تعالى نورى كرامت فرمود تا بقدم صحابه عظام و علماء كرام و مشايخ <14b> نورا على نور مهربانى يافتند بعضى از عباد الله آيت أفَمَن شَرَحَ [ٱللَّهُ] صدره للإسلام [فهو على نور] من ربه (Q 39:22) طغراى نشور و حضور و ضبور ايشان اشت دران منزل شريف مقام و مسكن ساختند تا بسركت بهرى الله تعالى من يشاء نوره مستعد كشتند بيت |

| خدايكه ظلمات نور آفريد |

| دل عارفانرا حضور آفريد |

| براى مقيمان آنجاى نور |

| جو بوستان جنت قصور آفريد |

| مقامى است خوش هوا و شريف الأوضاع و لطيف الامزاج و بى تكلف آب و هواى خشكوار و چشمه اش اوج افزاى از ضلال كوثر و نسم بهشت اخبار ميكند و صفاى مساكين دلكشايش از نزهت كلشن فردوس اظهار مى نمايد سواد النور نورا سواد العين اينچنين صفت نور مستور كشت و قد روى عن انس ابن مالک رضى الله عنه و عن عبد الله ابن مسعود انه قال رسول الله صلى الله عليه <15a> و سلم رحمة الله على اخوانى بالنور يعنى حضرت رسول اكرم كفتند كه رحمت خداوند باد بر برادران من كه بشهر نور مشرف كردد كفتند كه يا رسول الله نور در كجا است در ما وراء النهر ولايتى است كه قدم كاهى برادرم حضرت إسكندر ذو القرنين است و هر كه در نور يكبار در آيد حضرت مهيمن الإسلام تن او را از آتش دوزخ نجات دهد و هم عبد الله ابن مسعود روايت ميكنند كه در حديث ليلته الاسرار يعنى شب معراج در آسمان جهارم كوشكى ديدم آرسته و در حوالى آن كوشک قنديل هاى از نور آويخته حضرت پيغمبر عليه السلام كفتند يا برادر جبرئيل چيست اين كوشک آرسته و با اينهمه قنديل هاى از نور آويخته حضرت جبرئيل كفتند اين رباطست كه خداى تعالى امت شما را كرامت فرمود است در ما وراء النهر هر كه از امتان شما در دل او افتند كه <15b> بر غيبت خود در آنجا مقام كند و بر فراش خود در آنجا ميرد اميد است كه آمنا و صدقنا از شرافت نور جمله شهيدان بر انكيخته شود حضرت پيغمبر عليه السلام كفتند كه يا برادرى جبرئيل نام اين رباط چيست جبرئيل كفتند كه انرا نور ميخوانند و آنرا فضيلتهاست كه بر جميع رباطهاى ديكر همجون فضيلت افتاد بسياه تاب بر جميع ستاركانى حضرت پيغمبر عليه السلام كفتند كه من مشتاق آن شدم كه دران منزل متبرک دو ركعت نماز كذارم حضرت بارى تعالى و تقدس حضرت جبرئيل را با جندين هزار فرشته فرستاد تا زمين نور را بر آسمان چهارم بر اوردند حضرت پيغمبر عليه السلام از براق فروز آمدند و دران منزل متبرک دو ركعت نماز كذارد روند باز زمين نور را بجايش فروز آوردند حضرت جبرئيل عليه السلام كفتند كه خوش آن بنده كه از امتان شما در نور دو ركعت نماز <16a> كذارد و يا در آنجا چند تكبير كويد اميد است كه از عذاب هاى اليم مخلص يافته و از صراط مستقيم ايمين در كذرد هر كه در چشمه نور غسل كند جنان باشد كه از مادر خود نو تولد كرده باشد هر كه نور را زيارت كند كويا كه حضرت خانهْ كعبه را زيارت كرده باشد نقل است كه روزى حضرت پيغمبر عليه السلام كفتند كه من عانق نورا فكانما عانقنى يعنى حضرت پيغمبر عليه السلام كفتند كه هر كه مردم نور را در كنار كرد كويا كه مرا در كنار كرفته باشد هر كه مرا در كنار كيرد آتش دوزخ بر تن او حرام كردد چنين فرموده اند كه من اين سخنان را از حضرت جبرئيل شنيده ام حضرت جبرئيل كفتند كه من اين سخنانرا از حضرت ميكائيل شنيده ام و از حضرت ميكائيل كفتند كه من اين سخنانرا از حضرت عزرائيل شنيده ام و از حضرت عزرائيل كفتند كه من اين سخنان را از حضرت اسرافيل شنيده ام و از حضرت اسرافيل <16b> كفتند كه من اين سخنانرا در لوح المحفوظ نوشته ديدم كه حضرت أبو سليمان ابن إسحاق نقل ميكنند كه سنكى كه در ته چشمه نور است حضرت إسكندر بدست مبارک خود نهاده باشند هر كه خود را بران مالد هر زحمتيكه داشته باشد شفا يابد اينچنين از حضرت أبا بكر صديق رضى الله عنه نقل ميكنند كه ايشان هم كفته باشد سنكى كه در ته چشمه نور است حضرت إسكندر بدست مبارک خود نهاده باشند و حضرت أبو حفظ كبير بخارى رحمه الله عليه ميفرمايند كه من از اهل ولايت خود نمى بينم هيچ عبادتى بهتر از بنور رفتن بنور فضيلت بسيار است اما مختصر كرديم خواننده را و نويسنده را ملال نشود |

| والله اعلم بالصواب |

| طواف نور اكر خواهى ترا حاجت روا كردد |

| نماز حاجتت را بكذار دفع صد بلا كردد |

| كسى خواهد كه كردد پاک از جمع كناهاش |

| بآب نور غسل آرد كه بيشک با صفا كردد |

| رباعى ديكر باين مضمون <17a> |

| قطعه آمد زمين نور از خلد برين |

| چشمه بر فيض او از آب حوض كوثر است |

| اينچنين سرچشمه بنور ز ماهى تا بماه |

| طوف سنک زير آبش كن كه حج اكبر است |

| والله اعلم بالصواب |

Notes

| 1 | For a survey of sacred histories of local towns across broader Central Asia, see (Frye 1965), on Nishapur; (Jürgen 1993), on Samarqand; and (DeWeese 2000), on Sayrām along with references to primary and secondary sources on other sacred histories. |

| 2 | Traditionally identified as Alexander the Great. The figure of Iskandar Dhū’l-Qarnayn features prominently in the sacred histories of various other Central Asian towns. |

| 3 | (Schimmel 1995). |

| 4 | Frontier stations in medieval Islam. See (Chabbi and Rabbat 1997). |

| 5 | For the complex history of the Akhbār and its relationship to Ṣadr al-Dīn al-Ḥusaynī’s Zubdat al-tawārīkh, see (Durand-Guédy 2007). |

| 6 | It further records that in 426/1035, several Saljuq chieftains (Yabghu, Chaghrï Beg Dāwūd, and Ṭoghrïl Beg Muḥammad, the sons of Mīkāʾīl b. Seljuq, and Quṭlumush b. Isrāʾīl b. Seljuq) departed Nūr-i Bukhara for Khurasan shortly before the decisive Battle of Dandānqān (1040), which culminated in a Saljuq victory and brought an end to Ghaznavid domination in the region (Bosworth 2011, p. 128). For further information and additional sources on this pivotal battle, see (Mallett 2007). |

| 7 | For further information on the author and additional references, see (Hillenbrand 2006). |

| 8 | In MS 1533, the title appears as Risāla dar bayān-i vāqiʿa-yi kūh-i Nūr Atā va sabab-i muʿazzaz būdan-i ān (“Treatise on the appearance of the mountain of Nūr Atā and the reason for its being honored”). In MS 4626, the title reads Dar bayān-i vilāyat-i Nūr va chashma-yi ān (“On the province of Nūr and its spring”). MS 9857 does not include a title. The Turkic 2462 bears the title of Risāla-yi bayān-i avṣāf-i Nūr (“A treatise explaining the qualities of Nūr.”) |

| 9 | Narratives involving miʿrāj motifs are common in sacred histories and narratives of Islamization, where the Prophet blesses both the inhabitants and the locality itself during his ascent through the heavens. The miʿrāj account in the narrative tradition of Nūr Atā closely parallels the Prophet’s ascension, as described in the sacred history of Sayrām, including his performance of two rakʿas of prayer and his blessing of the town and its inhabitants. See (DeWeese 2000, p. 264). |

| 10 | MS 9857: beneath the sky of the world and in the land of Mawarannahr. |

| 11 | MS 9857: Nūr. |

| 12 | MS 4626 skips the last three sentences. |

| 13 | MS 9857: several thousand. |

| 14 | MS 9857: fourth Heaven. |

| 15 | Burāq is the mythic, celestial steed said to have borne the Prophet Muḥammad from Mecca to Jerusalem and back during the Miʿrāj. |

| 16 | MS 9857: the Prophet. |

| 17 | i.e., the phrase “Allāhu akbar.” |

| 18 | Full body ritual ablution. |

| 19 | MS 1533: seventy thousand. |

| 20 | This phrasing is ambiguous: it literally states, “Whoever embraces the people of Nūr will be as though embracing me, Muḥammad, seventy times,” which is confusing since Jibrīl, not Muḥammad, is the speaker in this quotation. |

| 21 | In MS 1533, Isrāfīl is omitted from this chain of transmission. |

| 22 | ‘The Safely Preserved Tablet,’ which, according to Muslim tradition, contains all that has happened and all that will happen. See (Wensinck and Bosworth 2012). |

| 23 | MS 1533 omits this sentence. |

| 24 | MS 9857: seventy thousand. |

| 25 | Abū Ḥafṣ Kabīr (d. 832) was a student of Muḥammad al-Shaybānī (d. 805), himself a disciple of Abū Ḥanīfa (d. 767), the eponym of the Ḥanafī school of jurisprudence. See (al-Narshakhī 1954, p. 56). |

| 26 | MS 9857: “from Heaven.” |

| 27 | MS 9857 and MS 4626: “The Companions said: ‘O Messenger of God, you did not mention such virtue in Noble Mecca.’ The Messenger replied: ‘They brought that Nūr to the fourth Heaven, and I performed two rakʿas prayers in Nūr. It will always possess virtue.’ That night, Dhū’l-Qarnayn saw that light and named it Nūr.” |

| 28 | Qurʾan 24:35. These verses appear in the margin of folio 4a in MS 9857 and at the end of MS 4626 (ff. 130a–b), serving as a concluding section to the Risāla-yi Nūr. Additional verses (discussed below) that appear in the concluding section of MS 8149/2 have been omitted here to avoid repetition. |

| 29 | MS 2193: Risāla dar bayān-i shahr-i Nūr Atā. |

| 30 | Qurʾan 24:35. |

| 31 | Qurʾan 6:1. |

| 32 | MS 2193 starts here: “It is not concealed…” |

| 33 | Qurʾan 39:69. |

| 34 | A town in the vicinity of Samarqand, located about 130 km from present-day Nūr Atā. See (Bosworth 2011). |

| 35 | Qurʾan 24:35. |

| 36 | Qurʾan 39:22. |

| 37 | Qurʾan 24:35. |

| 38 | A river in paradise. |

| 39 | MS 2193: [The Prophet:] “I prayed on behalf of [Nūr’s] inhabitants.” |

| 40 | MS 2193: “The reward for two rakʿas prayer in that place is equal to several years of worship.” |

| 41 | MS 2193: “Jibrīl related this from Mīkāʾīl, who related it from Isrāfīl, and he from ʿAzrāʾīl, who said: “I saw it written in the Lawḥ al-Maḥfūẓ.” |

| 42 | MS 2193: “Sulaymān b. Dāvud b. Isḥāq”. |

| 43 | MS 2193: “Whoever has a disease and an illness…”. |

| 44 | MS 2193 adds: “Khwāja ʿAbd al-Khāliq Ghijdūvānī, in accordance with the order of Khiżr, went down beneath that spring, embraced the stone, and performed dhikr.” |

| 45 | The same verses are found in MS 2193, MS 4626 and MS 9857. |

| 46 | In MS 2193, the sequence of these verses is reversed. MS 4626 also ends with these verses. |

| 47 | نام اين است |

References

Primary Sources

Dar bayān-i vilāyat-i Nūr va chashma-yi ān, MS 4626, Beruni Institute of Oriental Studies (hereafter IVRUz), ff. 129b–130b.Risāla bayān-i avṣāf-i Nūr, MS 2462, IVRUz, ff. 1b–6a.Risāla dar bayān-i shahr-i Nūr Atā, MS 2193, IVRUz, ff. 34b–35a.Risāla dar bayān-i vāqiʿa-yi kūh-i Nūr Atā va sabab-i muʿazzaz būdan-i ān, MS 1533, IVRUz, ff. 25b–27b.Risāla-yi Ḥażrat-i Nūr Atā, MS 8149, IVRUz, ff. 13b–17b.Risāla-yi Nūr, MS 576, IVRUz, ff. 46a–48a.[Risāla-yi Nūr], MS 9857, IVRUz, ff. 3a–4a.Secondary Sources

- al-Narshakhī, Muḥammad ibn Jaʿfar. 1954. The History of Bukhara. Translated by Richard N. Frye. Cambridge: Crimson Printing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Barthold, Wilhelm. 1928. Turkestan down to the Mongol Invasion. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund. 2011. The History of the Seljuq State: A Translation with Commentary of the Akhbār al-dawla al-saljūqiyya. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chabbi, Jacqueline, and Nasser Rabbat. 1997. Ribāṭ. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, hereafter EI2. [Google Scholar]

- DeWeese, Devin. 2000. Sacred History for a Central Asian Town: Saints, Shrines, and Legends of Origin in Histories of Sayrām, 18th–19th Centuries. Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée 89–90: 245–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand-Guédy, David. 2007. Ṣadr al-Dīn al-Ḥusaynī. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed. Leiden: Brill, hereafter EI3. [Google Scholar]

- Frye, Richard N., ed. 1965. The Histories of Nishapur. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guliamov, Ia. 1979. Nur Bukharskii. In Etnografiia i arkheologiia Srednei Azii. Moskva: Nauka, pp. 133–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, Carole. 2006. Rāwandī. In EI2. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgen, Paul. 1993. The Histories of Samarqand. Studia Iranica 22: 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgen, Paul, Gabriele Stein, and Annemarie Schimmel, eds. 2002. Katalog Sufischer Handschriften aus der Bibliothek des Instituts für Orientalistik der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Republik Usbekistan. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kastan’e, I. 1917. Arkheologicheskie razvedki v Bukharskikh vladeniiakh. In Protokoly zasedaniĭ i soobshcheniia chlenov Turkestanskogo kruzhka liubiteleĭ arkheologii. Tashkent: F. and G. Brothers Kamensky, pp. 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett, Alex. 2007. Battle of Dandanakan. In EI3. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ravendi, Muhammed b. Ali b. Süleyman. 1957. Rahat-üs sudur ve ayet-üs-sürur: Gönüllerin rahatı ve sevinç alameti. Translated by Ahmed Ateş. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basimevi, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel, Annemarie. 1995. al-Nūrī. In EI2. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Wensinck, Arent Jan, and C. E. Bosworth. 2012. Lawḥ. In EI2. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Yāqūt. 1866–1870. Muʿjam al-buldān. Edited by Ferdinand Wüstenfeld. 6 vols. Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).