Abstract

This study investigates instances of conflation and misattribution in the transmission of three Chinese Buddhist catalogues that share the title Zhongjing mulu 眾經目錄 (Catalogue of Various Scriptures), attributed, respectively, to Fajing 法經, Yancong 彥琮, and Jingtai 靜泰 during the Sui and Tang dynasties. Although these catalogues differ in structure, doctrinal classification, and historical context, their identical titles and overlapping content may have led to instances of conflation in the editorial processes of later Buddhist canons. This phenomenon is revealed and analyzed in the present study. Drawing primarily on the phonetic glosses appended to fascicles (suihan yinshi 隨函音釋) in the Pilu Canon 毗盧藏 and examining the bibliographic entries and marginal annotations referencing these catalogues in other editions, the study conducts a philological comparison with sources such as the Qisha 磧砂, Sixi 思溪, and Hongwu Southern Canons 洪武南藏. It identifies specific cases of misattribution, annotation displacement, and the merging of catalogue content without clear attribution. The findings suggest that ambiguity in catalogue entries and textual transmission resulted in instances where the three Zhongjing mulu catalogues were not clearly distinguished in later canons and modern databases. The article contributes to a clearer understanding of the editorial history and philological challenges involved in the formation of the Chinese Buddhist canon.

1. Introduction

Among extant catalogues of Buddhist scriptures, three catalogues are titled Zhongjing mulu 眾經目錄 (Catalogue of Various Scriptures), compiled, respectively, by Fajing 法經 of the Sui dynasty, by Yancong 彥琮, also of the Sui, and by Jingtai 靜泰 of the Tang. These are hereafter referred to as the Fajing Catalogue 法經錄, the Yancong Catalogue 彥琮錄, and the Jingtai Catalogue 靜泰錄. This study unfolds in the following sequence: it first focuses the treatment of the Zhongjing mulu in the phonetic glosses appended to fascicles (suihan yinshi 隨函音釋) in the Pilu Canon 毗盧藏. Among extant Song dynasty editions of the Chinese Buddhist canon, the Pilu Canon—often studied together with the Chongning Canon 崇寧藏 under the collective designation Fuzhou Canon 福州藏 is the earliest extant and relatively complete printed edition. Yet scholarly attention to the Pilu Canon has remained limited, with existing research focusing mainly on its date of publication, production background, block format, fascicle numbers, and scope of scripture inclusion.1

By contrast, significant scholarly attention in recent years has been devoted to the phonetic and semantic glosses appended to fascicles in later canons such as the Qisha Canon 磧砂藏 and Sixi Canon 思溪藏.2 As Tan (2023) has argued, the glosses appended to the Fuzhou Canon contain valuable linguistic data relevant to the history of Chinese language.3

Glosses appended to fascicles appear in canon editions from the Chongning Canon of the Northern Song through the Long Canon 龍藏 of the Qing. In each redaction, the phonetic glosses, typically appended at the end of scrolls or fascicles, underwent varying degrees of revision. As Mei He has emphasized, collating and comparing such phonetic glosses across editions can shed light on the genealogical relationships among different canons and the textual editing strategies applied in each edition. Accordingly, the study of appended glosses constitutes a key component in understanding the transmission of the Chinese Buddhist canon (Li and He 2003, p. 191).

Early scholars such as Ogawa Kan’ichi assumed that the Pilu Canon lacked appended glosses entirely (Ogawa 1984, vol. 25, p. 58). This view was followed by Daoan Shi and Shiqiang Chen (Shi 1978, p. 93; Chen 2000, p. 407). However, in June 2016, the Archives and Mausolea Department of Japan’s Imperial Household Agency 日本宮內廳書陵部 made available digital images of the Pilu Canon, including fascicle-end glossaries. Notably, after every ten fascicles, an additional volume titled Glosses Appended to Fascicles was found.4

This paper compares glossarial entries in the Pilu Canon corresponding to the Fajing Catalogue against both the catalogue’s main text and the appended glosses in three other major editions: the Qisha Canon, Sixi Canon and Hongwu Southern Canon 洪武南藏. Utilizing techniques from textual criticism, this study identifies the following features in the Pilu Canon’s phonetic glosses on the Fajing Catalogue:

- The origins of some glossarial entries are unclear.

- Certain glosses use characters that diverge from the corresponding entries in the main text.

- Glosses are appended to volumes different from those in which the corresponding terms appear.

Moreover, discrepancies are observed between the Pilu Canon glosses and those of the other three editions. This suggests that while the Qisha Canon’s appended glosses partially inherited textual material from the Northern Song, they also incorporate newly introduced forms and revisions influenced by later editions.

Having identified instances where the phonetic glosses of the Zhongjing mulu do not correspond to the textual content, the following analysis turns to external evidence in order to consider the possible reasons for their occurrence. In particular, attention is given to how the three Zhongjing mulu are recorded across different editions of the canon and to the specific marginal annotations associated with them.

The final section of this study is turned to the Zhongjing mulu itself, with an analysis of the structural and classificatory differences among the Fajing, Yancong, and Jingtai catalogues. Although all three works share the same title, they were compiled in different historical periods and include both overlapping and divergent selections of scriptures, each with its own distinctive features.

Despite these differences, later editions of the Chinese Buddhist canon frequently failed to distinguish among the three catalogues. In the process of compilation, misattribution and conflation among the catalogues likely occurred. This confusion extended into modern secondary literature as well, indicating a long-standing problem in both the editorial and scholarly traditions surrounding these works.

2. Characteristics of the Phonetic Glosses in the Pilu Canon

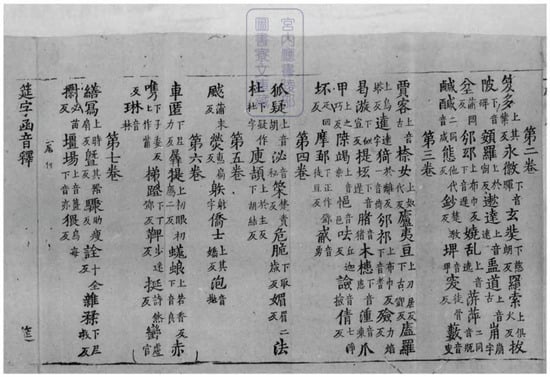

The Pilu Canon is formatted in the accordion-fold 經摺裝 style and arranged according to the “thousand character classic 千字文”5. Each woodblock contains thirty-six lines of text across six folding pages, with each page comprising six lines and each line containing seventeen characters. The primary material examined in this study consists of the phonetic glosses found in the lower half of the “Yanzi fascicle” 筵字函 in the Pilu Canon, specifically the annotations attached to the Zhongjing mulu compiled by Fajing and others during the Sui Dynasty. Facsimile images from the Fajing Catalogue section of the Pilu Canon, specifically illustrating the phonetic glosses appended to fascicles (suihan yinshi 隨函音釋) in scrolls 2 through 7, are presented below for reference6 (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Facsimile of phonetic glosses in the Fajing Catalogue section of the Pilu Canon, scrolls 2–7.

2.1. Phonetic Glosses on the Zhongjing mulu in the “Yanzi Fascicle”

The title page of the phonetic annotation volume for the “Yanzi fascicle” is labelled “Yanzi Yin” 筵字音, while the main title 內題 on the first page reads “Yanzi Han Yinshi” 筵字函音釋.7 The following line indicates that the glosses are extracted from “Scrolls 11 through 15 of the Collected Records of the Tripiṭaka” 出三藏記集,下五卷. The third line notes: “Seven scrolls of the Zhongjing mulu, twelve scrolls in total, bound as one fascicle.” What follows is a series of glossarial entries arranged sequentially by scripture and scroll, each presenting the term in question and its phonetic annotation. The font size of these entries is identical to that of the main text. The phonetic glosses are printed in interlinear double-line format. At the end of the volume, the colophon reaffirms the title with the phrase “Yanzi Han Yinshi”.

This paper focuses on the lower portion of the gloss volume, namely the phonetic annotations corresponding to the seven scrolls of the Fajing Catalogue. In total, there are 83 glossarial entries. Table 1 below presents the distribution and characteristics of these glosses across the seven scrolls:

Table 1.

Statistical Distribution of Phonetic Glosses in the Fajing Catalogue Section of the Pilu Canon.

The data revealed the following distribution: Scroll 1 spans approximately 31 pages and contains 13 glossarial entries. Scroll 2, with only 17 pages, includes 19 entries. Scroll 3, on 23 pages, contains 22 entries. Scrolls 4 and 5, each comprising about 20 pages, contain only 7 and 5 entries, respectively. Scroll 6 has 18 pages and 9 entries, whereas Scroll 7 spans 7 pages and includes 8 entries.

There appears to be a disproportion between scroll length and the number of phonetic annotations. Glosses are most heavily concentrated in the first three scrolls, although Scroll 1, despite being the longest, has fewer glosses than the shorter Scrolls 2 and 3. Scrolls 4 through 6 are of comparable length to Scrolls 2 and 3 (with a difference of at most six pages), yet their glossarial content is reduced by more than half.

Of the 83 entries, 44 employed the fanqie method of phonetic representation. Another 27 entries utilized the direct pronunciation notation. There were four entries provide standard character corrections rather than phonetic readings. Several entries combine methods. Some included both upper and lower character annotations.

This diverse range of annotation strategies reflects the meticulous philological engagement of the canon’s compilers. It also highlights the hybridization of phonetic annotation systems used in early Chinese Buddhist textual traditions.

2.2. Analysis of Anomalies

Through internal collation, comparing the glossarial entries appended to the Fajing Catalogue in the “Yanzi fascicle” of the Pilu Canon with the actual content of the Fajing Catalogue in the same canon, this study identified inconsistencies in source attribution. Some glosses refer to terms not found in the base text, or are associated with incorrect scroll references. In addition, external textual comparison was undertaken to examine the phonetic glosses appended to the Fajing Catalogue in three other canonical editions: the Qisha Canon, the Sixi Canon, and the Hongwu Southern Canon. Furthermore, the study compares two other catalogues that share the title Zhongjing mulu: the Yancong Catalogue of the Sui Dynasty, and the Jingtai Catalogue of the Tang Dynasty. These comparative sources help to elucidate the discrepancies between glosses and their purported textual bases. Below are several representative phenomena and related discussion.

2.2.1. Glossarial Entries with No Identifiable Source

Some phonetic glosses annotate characters or terms that do not appear anywhere in the canonical text that they are supposed to accompany. This issue is particularly prominent in the first six glosses of Scroll Two, which include the following entries: “Jiduo 笈多”, “Yonghui 永徽”, “Xuanzang 玄奘”, “Juansuo 羂索”, “Bapo 拔陂”, and “Eluo 頞羅”. An additional anomalous term, “Yuxie  頡”, appears in Scroll Four.

頡”, appears in Scroll Four.

頡”, appears in Scroll Four.

頡”, appears in Scroll Four.Among these, “Jiduo 笈多” is known from later catalogues as the name of a translator, and “Yuxie  頡” refers to a palace attendant; both names appear for the first time in Lidai Sanbao Ji 歷代三寶紀, a text compiled after the Fajing Catalogue. “Yonghui 永徽” was a reign title in the Tang Dynasty, and “Xuanzang 玄奘” was a renowned Tang Dynasty translator. Since the Fajing Catalogue was compiled during the Sui Dynasty, these names and term did not appear in the text.

頡” refers to a palace attendant; both names appear for the first time in Lidai Sanbao Ji 歷代三寶紀, a text compiled after the Fajing Catalogue. “Yonghui 永徽” was a reign title in the Tang Dynasty, and “Xuanzang 玄奘” was a renowned Tang Dynasty translator. Since the Fajing Catalogue was compiled during the Sui Dynasty, these names and term did not appear in the text.

頡” refers to a palace attendant; both names appear for the first time in Lidai Sanbao Ji 歷代三寶紀, a text compiled after the Fajing Catalogue. “Yonghui 永徽” was a reign title in the Tang Dynasty, and “Xuanzang 玄奘” was a renowned Tang Dynasty translator. Since the Fajing Catalogue was compiled during the Sui Dynasty, these names and term did not appear in the text.

頡” refers to a palace attendant; both names appear for the first time in Lidai Sanbao Ji 歷代三寶紀, a text compiled after the Fajing Catalogue. “Yonghui 永徽” was a reign title in the Tang Dynasty, and “Xuanzang 玄奘” was a renowned Tang Dynasty translator. Since the Fajing Catalogue was compiled during the Sui Dynasty, these names and term did not appear in the text.The gloss “Juansuo 羂索” likely refers to the Bukong Juansuo Jing 不空羂索經, translated by Jueduo 崛多 during the Kaihuang era of the Sui. According to Lidai Sanbao Ji, this sūtra was produced around the same time as the Fajing Catalogue, which explains why it was not included therein.

The term “Bapo 拔陂” appears as a gloss in Scroll Two. A scripture titled Sūtra of the Bodhisattva Bapo 拔陂菩薩經8 survives in the present canon. However, the Fajing Catalogue records the title as Sūtra of the Bodhisattva Batuo 跋陀菩薩經, while the Yancong Catalogue gives Sūtra of the Bodhisattva Batuo 拔陀菩薩經. Another glossed term in Scroll Two, “Eluo 頞羅”, does not appear in either the Fajing Catalogue or the Yancong Catalogue. A possible analogue can be found in the Sūtra on the Brahmin Poluoyan’s Inquiry into the Noble Lineage 梵志頗羅延問種尊經, where the term “Poluo 頗羅” resembles “Eluo 頞羅”. However, the Jingtai Catalogue lists a sūtra titled Sūtra on the Brahmin Eluoyan’s Inquiry into the Noble Lineage 梵志頞羅延問種尊經.

A survey of canonical catalogues across dynasties indicates that both the Sūtra of the Bodhisattva Bapo and the Sūtra on the Brahmin Eluoyan’s Inquiry into the Noble Lineage first appear in the Jingtai Catalogue.9 This suggests that the glosses in question were not derived from the Fajing Catalogue itself, but from later catalogues that were possibly conflated in the compilation of the glossarial volume in the Pilu Canon.

2.2.2. Discrepancies Between Glossarial Entries and Main Text Vocabulary

Upon close comparison, nearly 20 instances were identified in which the wording of the phonetic glosses differed from that found in the main text of the Fajing Catalogue within Pilu Canon.10

These examples reveal that glossarial entries frequently use vulgar or colloquial characters. As noted by Wuyun Chen in his General Studies on the Phonetic and Semantic Glosses in Buddhist Scriptures, the compilers of Buddhist phonetic glossaries paid particular attention to the standardization and documentation of colloquial or vulgar character forms. (Xu et al. 2009, p. 153). He further asserts that such glosses serve as early and valuable repositories for the study of non-standard orthographies in premodern Chinese. (Xu et al. 2009, p. 155)

To verify the usage of these characters, this study conducted a cross-editions collation between the glosses in the Pilu Canon and the main text of the Fajing Catalogue in other canon editions. The results show that a significant number of these character forms, as listed in the glossarial entries in Table 2, namely items no. 1, 3, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, and 16, correspond closely to the wording used in the Goryeo Canon. This suggests that the glosses in the Pilu Canon may have been influenced by or derived from textual variants preserved in the Goryeo edition, even though they appear under the heading of the Fajing Catalogue.

Table 2.

Examples include glosses that use variant or vulgar forms of characters.

2.2.3. Inconsistencies in Scroll Number References

Numerous discrepancies were observed between glossarial entries and the corresponding scroll numbers in the base text. In Scroll Two of the phonetic glosses, for instance, there are 19 entries, of which 7 do not appear at all in Scroll Two of the Fajing Catalogue. The remaining 12 appeared in other scrolls of the same text. Surprisingly, the only edition in which all 19 glossarial entries match the text of Scroll Two is the Jingtai Catalogue. However, the Pilu Canon does not include the Jingtai Catalogue among its contents, raising questions about how these glosses came to be appended in this context.

Similarly, Scroll Four contained 7 glossarial entries. As noted earlier, one of these entries—“Yuxie”  頡—does not appear in the Fajing Catalogue at all. Two additional entries other than Scroll Four, are found in other scrolls. Intriguingly, all glossed terms in Scroll Four correspond exactly to the content of Scroll Four in the Yancong Catalogue. This again points to the possibility that the phonetic glosses in the Pilu Canon may have incorporated content from multiple catalogues titled Zhongjing mulu, without a clear distinction between them.

頡—does not appear in the Fajing Catalogue at all. Two additional entries other than Scroll Four, are found in other scrolls. Intriguingly, all glossed terms in Scroll Four correspond exactly to the content of Scroll Four in the Yancong Catalogue. This again points to the possibility that the phonetic glosses in the Pilu Canon may have incorporated content from multiple catalogues titled Zhongjing mulu, without a clear distinction between them.

頡—does not appear in the Fajing Catalogue at all. Two additional entries other than Scroll Four, are found in other scrolls. Intriguingly, all glossed terms in Scroll Four correspond exactly to the content of Scroll Four in the Yancong Catalogue. This again points to the possibility that the phonetic glosses in the Pilu Canon may have incorporated content from multiple catalogues titled Zhongjing mulu, without a clear distinction between them.

頡—does not appear in the Fajing Catalogue at all. Two additional entries other than Scroll Four, are found in other scrolls. Intriguingly, all glossed terms in Scroll Four correspond exactly to the content of Scroll Four in the Yancong Catalogue. This again points to the possibility that the phonetic glosses in the Pilu Canon may have incorporated content from multiple catalogues titled Zhongjing mulu, without a clear distinction between them.These discrepancies suggest that the glossarial entries were not directly derived from the Fajing Catalogue alone but may have been conflated with entries from the Jingtai and Yancong catalogues. This blending of sources could explain the mismatched scroll references and non-corresponding vocabulary, and raises broader questions about the editorial history of phonetic glosses in canonical editions.

3. Comparative Analysis of Fajing Catalogue Glosses Across Canonical Editions

Among the extant editions of the Chinese Buddhist canon, the present author has identified four versions that contain phonetic glosses appended to the Fajing Catalogue: the Pilu Canon, Sixi Canon, Qisha Canon, and Hongwu Southern Canon. Collation revealed that the most significant divergence occurred in glosses to Scroll Six. The Pilu Canon includes nine glosses for this scroll, whereas the Sixi Canon no contains. The Qisha Canon and Hongwu Southern Canon each provide five glosses. These differences are summarized in Table 3.11

Table 3.

Glossarial Entries in Scroll Six across Different Canons.

As shown above, the five entries from the Qisha Canon, namely “叡 rui”, “ 鬘 man”, “廬山 lushan”, “ 婆 pipo”, and “挻 yan” differ from the nine entries in the Pilu Canon, such as “車匿 cheni”, “羼提 chanti”, and “梯蹬 tideng”. Only a few terms appear in both editions: “挻 yan” is the only overlapping entry, while “婆 po” and another term may reflect partial overlap depending on character variants. However, even in these cases, the phonetic annotation differs: for instance, “yan” 挻 is annotated as “詩然反 shi ran fan” in the Pilu Canon and “連反 lian fan” in the Qisha Canon; “步迷反 bu mi fan” in the Pilu Canon contrasts with “毗移反 pi yi fan” in the Qisha Canon for a similar term.

婆 pipo”, and “挻 yan” differ from the nine entries in the Pilu Canon, such as “車匿 cheni”, “羼提 chanti”, and “梯蹬 tideng”. Only a few terms appear in both editions: “挻 yan” is the only overlapping entry, while “婆 po” and another term may reflect partial overlap depending on character variants. However, even in these cases, the phonetic annotation differs: for instance, “yan” 挻 is annotated as “詩然反 shi ran fan” in the Pilu Canon and “連反 lian fan” in the Qisha Canon; “步迷反 bu mi fan” in the Pilu Canon contrasts with “毗移反 pi yi fan” in the Qisha Canon for a similar term.

婆 pipo”, and “挻 yan” differ from the nine entries in the Pilu Canon, such as “車匿 cheni”, “羼提 chanti”, and “梯蹬 tideng”. Only a few terms appear in both editions: “挻 yan” is the only overlapping entry, while “婆 po” and another term may reflect partial overlap depending on character variants. However, even in these cases, the phonetic annotation differs: for instance, “yan” 挻 is annotated as “詩然反 shi ran fan” in the Pilu Canon and “連反 lian fan” in the Qisha Canon; “步迷反 bu mi fan” in the Pilu Canon contrasts with “毗移反 pi yi fan” in the Qisha Canon for a similar term.

婆 pipo”, and “挻 yan” differ from the nine entries in the Pilu Canon, such as “車匿 cheni”, “羼提 chanti”, and “梯蹬 tideng”. Only a few terms appear in both editions: “挻 yan” is the only overlapping entry, while “婆 po” and another term may reflect partial overlap depending on character variants. However, even in these cases, the phonetic annotation differs: for instance, “yan” 挻 is annotated as “詩然反 shi ran fan” in the Pilu Canon and “連反 lian fan” in the Qisha Canon; “步迷反 bu mi fan” in the Pilu Canon contrasts with “毗移反 pi yi fan” in the Qisha Canon for a similar term.Although the selected entries differ, both canons appear to have extracted their glosses from Scroll Six of the Fajing Catalogue, with one exception: the term “廬山 lushan” in the Qisha Canon likely derives from Scroll Five rather than Scroll Six.

In addition to the differences in Scroll Six, the Pilu Canon also contains unique single-character glosses in Scrolls One through Five that are not found in other canon editions. For instance: In Scroll One, the gloss “齲 qu” is annotated as “丘禹反 qiu yu fan”; In Scroll Two, a term is annotated as “ beng” (means as the character “崩 beng”); Another in the same scroll is annotated as “

beng” (means as the character “崩 beng”); Another in the same scroll is annotated as “ da” (means as the character “達 da”); Still another gloss “

da” (means as the character “達 da”); Still another gloss “ yong” in Scroll Two is given as “音勇 yin yong” (means pronounced as “yong”; In Scroll Four, the gloss “杜 du” is explained as “下疑作社字 xia yi zuo she zi” (means the lower character is possibly mistaken for “ 社 she”); In Scroll Five, “䠶 she” is annotated as “射字 she zi” (means as the character “射”).

yong” in Scroll Two is given as “音勇 yin yong” (means pronounced as “yong”; In Scroll Four, the gloss “杜 du” is explained as “下疑作社字 xia yi zuo she zi” (means the lower character is possibly mistaken for “ 社 she”); In Scroll Five, “䠶 she” is annotated as “射字 she zi” (means as the character “射”).

beng” (means as the character “崩 beng”); Another in the same scroll is annotated as “

beng” (means as the character “崩 beng”); Another in the same scroll is annotated as “ da” (means as the character “達 da”); Still another gloss “

da” (means as the character “達 da”); Still another gloss “ yong” in Scroll Two is given as “音勇 yin yong” (means pronounced as “yong”; In Scroll Four, the gloss “杜 du” is explained as “下疑作社字 xia yi zuo she zi” (means the lower character is possibly mistaken for “ 社 she”); In Scroll Five, “䠶 she” is annotated as “射字 she zi” (means as the character “射”).

yong” in Scroll Two is given as “音勇 yin yong” (means pronounced as “yong”; In Scroll Four, the gloss “杜 du” is explained as “下疑作社字 xia yi zuo she zi” (means the lower character is possibly mistaken for “ 社 she”); In Scroll Five, “䠶 she” is annotated as “射字 she zi” (means as the character “射”).Except for the gloss “齲 qu”, which does appear in the text of Scroll Two of the Pilu Canon’s Fajing Catalogue, the remaining glossed terms do not correspond to the vocabulary of the Fajing Catalogue as preserved in that edition. This discrepancy again suggests that the compilers of the glosses may have consulted multiple versions of catalogues or interpolated terms from other texts when assembling the appended glossarial content.

4. The Zhongjing mulu Across Canonical Editions

The preceding analysis of the phonetic glosses in the Pilu Canon, including their anomalies, textual discrepancies, and comparative features across different editions, has demonstrated that glossarial materials reflect complex processes of transmission and redaction. To further clarify the sources of these inconsistencies and the broader context of their occurrence, the following section turns to examine how the three Zhongjing mulu catalogues were preserved in successive editions of the Buddhist canon and the forms of marginal annotation attached to them.

4.1. Catalogue Entries

According to He Mei’s reference work, A New Examination of Catalogues in the Chinese Buddhist Canon through the Ages (Lidai Hanwen Dazangjing Mulu Xinkao 歷代漢文大藏經目錄新考, hereafter Xinkao), the entries of the three Zhongjing mulu catalogues from the Sui and Tang dynasties can be identified as follows: entry no. 3959 lists “Zhongjing mulu, 7 juan (卷 scrolls), compiled by Fajing and others of the Sui dynasty”; entry no. 3960 states “Zhongjing mulu, 5 juan (卷 scrolls), compiled by scriptural translators and scholars of the Sui”; entry no. 3961 records “Zhongjing mulu, 5 juan (卷 scrolls), compiled by Jingtai of the Tang.”

First, regarding the Fajing Catalogue, the comparison tables in Xinkao show that among thirty-one editions of the Buddhist canon12 surveyed by He, all except the Fangshan Stone Canon房山石經 and the Puhui Canon 普慧藏 include the Fajing Catalogue. Although the First Carved Goryeo Canon 初雕高麗藏 is not mentioned by the author, it too, based on the present author’s observation, contains the Fajing Catalogue.

Second, concerning the Yancong Catalogue, it is preserved in the Fuzhou Canon, Zifu Canon 資福藏, Qisha Canon, Puning Canon 普寧藏, Early Southern Canon 初刻南藏, Tenkaizan Catalogue 天海藏, Yuanshan Canon 緣山藏, Yongle Southern Canon 永樂南藏, Yongle Northern Canon 永樂北藏, Jiaxing Canon 嘉興藏, Long Canon, Huangbo Canon 黃檗藏, the Taiwan edition of the Chinese Canon 台灣版中華藏, Taishō Canon 大正藏, and the Mainland Chinese Canon 大陸版中華藏. In addition, it appears in various scriptural catalogues such as the Kaiyuan Lu 開元錄, Zhenyuan lu 貞元錄, Zhiyuan lu 至元錄, Kaiyuan lu Abridged 開元錄略出, Da Ming yimen 大明義門, and Yuezang zhijin 閲藏知津.

Third, the Jingtai Catalogue is found in the Zhaocheng Canon 趙城金藏, Recarved Goryeo Canon 再雕高麗, Manji Canon 卍正藏, Taishō Canon, Mainland Chinese Canon, Condensed Canon 縮刻藏, Pinjia Canon 頻伽藏, and Buddhist Canon 佛教藏, as well as in the First Carved Goryeo Canon, which, although not listed in Xinkao, contains it according to the present author’s inspection. The catalogue is also referenced in bibliographies such as the Zhiyuan lu 至元錄 and Fabao biaomu 法寶標目.

A comparative analysis of the canon editions listed above reveals a clear pattern: those editions that include the Yancong Catalogue do not include the Jingtai Catalogue, and vice versa. The same mutual exclusivity applies to catalogue entries within Buddhist bibliographies.

To investigate this phenomenon further, we turn to the documentary evidence found in Tang and Song catalogues. According to Zhisheng’s Kaiyuan lu 開元錄, in the section titled “Comprehensive List of Scriptural Catalogues Past and Present 開元錄.總括群經錄.敘列古今諸家目錄”, the entry reads: “Zhongjing mulu, 5 scrolls, added Xuanzang’s translations to the Sui Catalogue; otherwise no differences. Compiled by the monk Jingtai of the Dajing’ai Monastery in the Great Tang 《眾經目錄》五卷 於《隋錄》內加奘譯經,餘皆無13異。大唐大敬愛寺沙門靜泰撰。 右從古錄已下三十一家諸錄之中,雖皆備述,欲尋其本,難可備焉,且列名題知其有據”.14 This suggests that Zhisheng had not directly seen the Jingtai Catalogue, but only listed its title.

In the Kaiyuan lu’s fascicle-entry section, only the Fajing15 and Yancong16 catalogues are listed. This record is consistent with Yuan Zhao’s Zhenyuan lu. Interestingly, by the fourth year of the Chongning 崇寧 reign (1105–1106 CE) in the Northern Song 北宋, Wang Gu’s 王古 Dazang Shengjiao Fabao Biaomu17 大藏聖教法寶標目 provides the following entries in fascicle 9: “Zhongjing mulu, 7 scrolls, compiled by the Sui monk Fajing et al.《眾經目錄》七卷。右隋僧法經等撰”18, and “Zhongjing mulu, 5 scrolls, compiled by Shi Jingtai of the Tang. Includes more than 2000 works in over 6000 fascicles 《眾經目錄》五卷。右唐釋靜泰撰。凡二千餘部六千餘卷”19. Notably, this source omits any mention of the Yancong Catalogue.

4.2. Marginal Notes and Interlinear Annotations in Canon Editions

As noted above, the extant editions that include the Jingtai Catalogue are the First Carved Goryeo Canon, the Recarved Goryeo Canon, and the Zhaocheng Canon. Among these, two particular annotation patterns are worth highlighting.

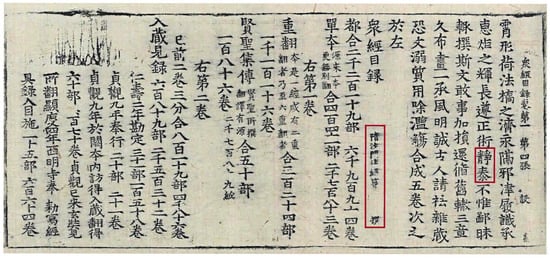

First, while the Jingtai Catalogue in all three editions opens with a preface followed by a list of scripture entries, the Recarved Goryeo Canon contains an additional line inserted between the preface and the catalogue proper. This line reads: “Zhongjing mulu,” accompanied by a marginal annotation: “Compiled by the Sui monks Fajing and others” 隋沙門法經等撰.20 As evidenced in the Recarved Goryeo Canon, as shown in the Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Annotation in the Recarved Goryeo Canon identifying the Zhongjing mulu.

This is striking, as it appears in a catalogue attributed to Jingtai, not Fajing. The same annotation appears as part of the main text in the Taishō Canon, rather than as a marginal note. However, in the digital edition by CBETA, this line has been removed and corrected. Notably, this problematic annotation is absent in the First Carved Goryeo Canon, which serves as the base text for the Recarved Goryeo Canon, as well as in the Zhaocheng Canon.

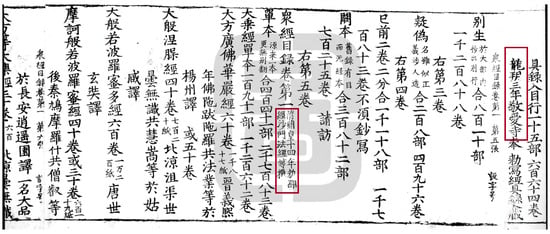

Second, in both the Recarved Goryeo Canon and the Zhaocheng Canon, a similar marginal note appears below the title “Zhongjing mulu, fascicle one” 眾經目錄卷第一. Taking Zhaocheng Canon as an example, as demonstrated in the Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Annotation in the Zhaocheng Canon identifying the Zhongjing mulu.

As can be seen from the above screenshot, the annotation reads: “Compiled in the 14th year of the Kaihuang 開皇 reign by imperial command, by the monks Fajing and others from the Scripture Translation Bureau” 隋開皇十四年勅翻經沙門法經等撰, See (Chen 2008, pp. 44–45).21 This line clearly pertains not to the Jingtai Catalogue, but to the Fajing Catalogue. Supporting evidence comes from the preface to the Fajing Catalogue in fascicle seven, which states that it was compiled by the monastic community led by Fajing at Daxingshan Monastery 大興善寺 on the fourteenth day of the seventh month in the fourteenth year of the Kaihuang reign (594 CE) 開皇十四年七月十四日大興善寺翻經眾沙門法經等.22 A similar formulation also appears in Zhisheng’s Kaiyuan lu, which references “Zhongjing mulu, 7 scrolls,” along with the annotation: “1 fascicle General Catalogue 總錄, 6 fascicles Separate Entries 別錄, compiled by twenty eminent monks under imperial order at the Scripture Translation Bureau in the 14th year of the Kaihuang era.”

These instances suggest that the Recarved Goryeo Canon and the Zhaocheng Canon inadvertently incorporated annotations pertaining to the Fajing Catalogue into their versions of the Jingtai Catalogue. It is noteworthy, however, that the First Carved Goryeo Canon, which also includes the Jingtai Catalogue, contains neither of these erroneous interpolations.23

5. A Comparative Analysis of the Structures of the Three Zhongjing mulu

Following the external textual analysis, namely the marginal annotations across various canon editions and the appended phonetic glosses linked to the Zhongjing mulu, this section turns to a comparison of the catalogues’ internal classificatory structures. This examination aims to clarify how structural similarities and differences among the three works may have contributed to their misidentification and conflation in later canonical compilations.

The Fajing Catalogue classifies texts into six primary categories based on doctrinal content: the Tripiṭaka of the Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna (Sūtra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma), together with compilations 撰集, biographies 傳記, and treatises 著述. Within each class, the texts are further subdivided according to their translation status and authenticity into six subcategories: “single translation” 一譯, “alternate translations” 異譯, “lost translations” 失譯, “indigenous productions” 別生, “doubtful works” 疑惑, and “spurious or apocryphal texts” 偽妄. Notably, for compilations, biographies, and treatises, an additional regional distinction is made between texts of Chinese origin and those from India or the Western Regions.

The Yancong Catalogue adopts a structure of six rubrics: “single works” 單本, “retranslated works” 重翻, “collected sayings and records of the sages” 賢聖集傳, “indigenous productions” 別生, “doubtful and spurious works” 疑偽, and “fragmentary works” 闕本. Within the “single works” rubric, a tripartite classification of the Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna Tripiṭaka is maintained. The “retranslated works” are further subdivided into Mahāyāna sūtra, vinaya texts, and treatises, along with Hīnayāna sūtra. The “indigenous productions” rubric is itself detailed into subcategories such as “Mahāyāna indigenous works” 大乘別生, “Mahāyāna excerpted indigenous works” 大乘別生抄, “Hīnayāna indigenous works” 小乘出別生, “Hīnayāna excerpted indigenous works” 小乘別生抄, and “compilation excerpts” 別集抄.

The Jingtai Catalogue closely resembles the structure of the Yancong Catalogue, adopting the same primary rubrics: “single works,” “retranslated works,” “collected sayings of the sages,” “indigenous productions,” “doubtful works,” “spurious works,” and “fragmentary works.” While the classification of “single works,” “retranslated works,” and “indigenous productions” follows that of the Yancong Catalogue, the Jingtai Catalogue further refines the broad “doubtful and spurious” category into two discrete rubrics: “doubtful works” and “spurious/apocryphal works”.

From the catalogue prefaces, the following key similarities and differences emerge:

- The Fajing Catalogue’s category “single translation” corresponds to the “single works” in Yancong Catalogue and Jingtai Catalogue. All three catalogues classify Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna sūtras, vinaya, and treatises into six subdivisions.

- The Fajing Catalogue uses “alternate translations”, equivalent to the “retranslated works” in the other two catalogues. However, Fajing Catalogue divides this into six subcategories (Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna sūtras, vinaya, treatises), while Yancong presents four (omitting Hīnayāna vinaya), and Jingtai expands it to five by restoring that omission.

- All three catalogues include a “separately produced works” section.

- Both Fajing Catalogue and Jingtai Catalogue further subdivide doubtful texts into “doubtful” and “spurious”, while Yancong Catalogue combines both under a single “spurious” category.

- Only Fajing Catalogue includes a dedicated category for “lost translations”, absent in the other two catalogues.

- Yancong Catalogue and Jingtai Catalogue include a “fragmentary works” rubric, which is not found in Fajing Catalogue.

- The “collected sayings of sages” and “excerpted indigenous works” 抄 found in Yancong Catalogue and Jingtai Catalogue are functionally analogous to Fajing’s “Western Region compilations” 西域撰集, “Western Region biographies” 西域傳記, and “local Chinese compilations” 此方抄集. See (Chen 2008, pp. 44–45)

- The Fajing Catalogue includes several unique rubrics absent in the others, such as “Chinese biographies” 此方傳記, “Indian treatises” 西域著述, and “Chinese treatises” 此方著述.

- From the above analysis, it is clear that while the Fajing Catalogue differs in both terminology and structural depth, Yancong Catalogue and Jingtai Catalogue are highly similar. In fact, the structure of the Jingtai Catalogue appears to be directly modelled upon the Yancong Catalogue, with only minor elaborations. See (Chen 2008, p. 53) Nevertheless, Yancong itself was not developed in isolation; it reflects the influence of Fajing’s taxonomy. Thus, the three catalogues are deeply interrelated in their design, and the substantial structural overlap has likely contributed to their conflation in later editions of the canon.

6. Contemporary Documentation and Bibliographic Errors

Beyond the textual confusion found in premodern sources, modern bibliographies and databases also exhibit instances in which the three Zhongjing mulu catalogues are erroneously conflated. A few representative cases are discussed below.

First, in the anthology Collected Prefaces to Chinese Buddhist Scriptures and Treatises 中國佛教經論序跋記集, under the heading “Fajing”, a preface attributed to the Zhongjing mulu is included. However, the content of this preface is in fact drawn from the Yancong Catalogue. See (Xu 2002, pp. 213–14)

Second, two prominent online canonical databases have been found to contain discrepancies. In the database of the Japanese Institute for the Study of Classical Buddhist Manuscripts (Nihon Koshakyo Kenkyūjo 日本古写経研究所), the digitized facsimile for Taishō no. 2146—corresponding to the Fajing Catalogue—displays, on the first page of fascicle two, the text of what is clearly the second fascicle of the Yancong Catalogue. Conversely, the fascicle labelled as Taishō no. 2147, which should represent the Yancong Catalogue, instead contains content matching that of the Fajing Catalogue. This discrepancy was first noticed by the author in year 2019. Upon recent examination, it has been found that the issue has since been corrected. The traces of this revision can be observed on the same pages, where the entry for the Fajing Catalogue originally labelled as scripture no. 1175 in the Zhenyuan lu has been changed to no. 1177 for the Yancong Catalogue, and vice versa.24

An additional anomaly is worth noting. In fascicle two of the Yancong Catalogue as preserved in the Japanese database25, the number of folios 紙數 is indicated for each scripture—a feature not found in this catalogue in any other known edition. When compared to the folio counts in the Jingtai Catalogue, these figures are not consistently aligned, suggesting an editorial interpolation or misattribution.

Third, in the “Ancient Books and Rare Literature Resources” database maintained by the National Library of China (NLC) 古籍與特藏文獻資源, an entry for the Zhongjing mulu lists the author as “(Sui) Shi Fajing” 隋釋法經撰. However, the digitized image presented on the corresponding webpage clearly displays the preface and contents of the Jingtai Catalogue.26

Taken as a whole, these modern examples in conjunction with the premodern evidence discussed above demonstrate that even in Song-dynasty canons the three catalogues were not strictly distinguished. This pattern of confusion has continued into the present, with digital databases and scholarly bibliographies occasionally misattributing one catalogue for another. Such conflations underscore the importance of philological precision when engaging with historical catalogues of the Chinese Buddhist canon.

7. Concluding Remarks

Through the collation of the phonetic glosses in the Pilu Canon and the main text of the Fajing Catalogue, and by extending this analysis to other canonical editions, namely the First Carved Goryeo Canon, the Zhaocheng Canon, the Sixi Canon, the Qisha Canon, the Recarved Goryeo Canon, and the Taishō Canon, a number of orthographic variations in scripture titles have been identified.

For instance, the scripture titled Asuda jing 阿遬達經, found in fascicle three of the Fajing Catalogue in the Pilu Canon, records the characters 遬達. In contrast, all other editions transcribe it as 漱達. Similarly, a scripture titled Fantian shenrong jing 梵天神榮經 appears in the Pilu Canon, but in the appended phonetic glosses for that fascicle, the character 筞 appears. This suggests that the 榮 character in the main text may be a transcriptional error arising from visual similarity, which was corrected in the gloss. 筞 is a variant of 策, and other editions confirm the correct title as Fantian shence jing 梵天神策經. The character 筞 appears in the Goryeo edition, while the Qisha edition employs a different variant, 䇿.27

Another illustrative example arises in the case of Mohe zheshe xuan jing 摩訶遮曷漩經, recorded in fascicle three of the Fajing Catalogue. The character 漩 appears with multiple variant renderings in historical catalogues: 㳬 in the Chu sanzang jiji28; 遊 in the Lidai sanbao ji29, Fajing Catalogue30, and Yancong Catalogue31; 旋 in the Da Zhou kanding zhongjing mulu 大周刊定眾經目錄32 and the Kaiyuan Catalogue33; 從 in alternate entries of the Kaiyuan Catalogue34 and the Zhenyuan Catalogue35; and 涉 in other parts of the Zhenyuan Catalogue36. These discrepancies likely stem from character shape similarities and transmission errors.

Likewise, a scripture titled Tianwang xiazuo shi jing 天王下作䐗經 shows the character 䐗, a variant form of 猪, which is rendered inconsistently across editions. The Huaiyu jing 坏喻經 is another case in which phonetic annotation indicates that the character 坏 is a variant of 坯, suggesting that the correct title should be Peiyu jing 坯喻經.

By the Ming dynasty, the Hongwu Southern Canon introduced additional errors in phonetic glosses due to confusion between variant characters. For example, a gloss for “提  ti di” in the Pilu Canon is miswritten as 提

ti di” in the Pilu Canon is miswritten as 提  ti tan in the Hongwu Southern Canon. According to the Ministry of Education’s Dictionary of Chinese Character Variants,

ti tan in the Hongwu Southern Canon. According to the Ministry of Education’s Dictionary of Chinese Character Variants,  corresponds to 坻, while

corresponds to 坻, while  is a variant of 壇—two unrelated characters wrongly conflated. It is likely that the error was caused by an extra dot stroke mistakenly engraved above the character “xuan 玄”.

is a variant of 壇—two unrelated characters wrongly conflated. It is likely that the error was caused by an extra dot stroke mistakenly engraved above the character “xuan 玄”.

ti di” in the Pilu Canon is miswritten as 提

ti di” in the Pilu Canon is miswritten as 提  ti tan in the Hongwu Southern Canon. According to the Ministry of Education’s Dictionary of Chinese Character Variants,

ti tan in the Hongwu Southern Canon. According to the Ministry of Education’s Dictionary of Chinese Character Variants,  corresponds to 坻, while

corresponds to 坻, while  is a variant of 壇—two unrelated characters wrongly conflated. It is likely that the error was caused by an extra dot stroke mistakenly engraved above the character “xuan 玄”.

is a variant of 壇—two unrelated characters wrongly conflated. It is likely that the error was caused by an extra dot stroke mistakenly engraved above the character “xuan 玄”.These examples indicate that philological errors have occurred not only in main texts but also in glossarial annotations across different canonical editions. This study has highlighted such instances and traced their likely origins, whether stemming from mistaken character recognition or from the intertextual borrowing and re-editing between editions.

Fuhua Li and Mei He have demonstrated that the phonetic glosses of the Yuan-edition Qisha Canon and the Puning Canon37 were likely influenced by the Pilu Canon, See (Li and He 2003, p. 219). While the present study did not directly examine the glosses of the Puning Canon, variant forms and distinctive entries in fascicle six of the Qisha Canon suggest both inheritance and modification. The Qisha Canon may have introduced new readings or forms influenced by additional editions.

Furthermore, across all canonical editions, those that contain the Yancong Catalogue never include the Jingtai Catalogue, and vice versa. In light of discrepancies between gloss entries and the fascicle structure of main texts, this study proposes that the Pilu Canon likely conflated three separate catalogues bearing the same title Zhongjing mulu.

Such confusion is not without precedent. As Mei He notes, there are multiple instances of erroneous attribution and content displacement in the transmission history. For example, the Zhaocheng and Goryeo editions misassigned the contents of fascicle four of the Fajing Catalogue under the Jingtai Catalogue. Other canon editions, such as the Manji, Zhonghua, and Pinjia, also contain blended entries that conflate the Jingtai and Yancong Catalogues (He 2014, vol. 1, p. 660). The editorial apparatus of the Qisha Canon and the Hongwu Southern Canon likewise perpetuates this conflation in their appended glosses.

In conclusion, this study has shown that the confusion among the three catalogues titled Zhongjing mulu, namely those compiled by Fajing, Yancong, and Jingtai, was most likely introduced by those responsible for compiling the phonetic glosses appended to the fascicles, rather than by the principal editors of the Pilu Canon itself. These glosses exhibit a mixture of entries traceable to distinct catalogical traditions, suggesting that the compilers may have assumed them to be components of a single unified catalogue. While such editorial oversight is understandable given the similarity in titles and formats, it has led to persistent misattributions in canon formation and interpretive errors in later editions. Traces of this conflation remain visible even in modern digital Buddhist databases, indicating the long-term transmission and institutionalization of such errors. The case highlights the importance of collateral materials, such as glosses, for reconstructing the layered processes through which canonical authority was established in Chinese Buddhism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T. and B.T.; methodology, T.T. and B.T.; software, T.T.; validation, T.T.; formal analysis, T.T.; investigation, T.T.; resources, T.T.; data curation, T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, T.T. and B.T.; visualization, B.T.; supervision, B.T.; project administration, T.T. and B.T.; funding acquisition, B.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For a more comprehensive study on the Pilu Canon 毗盧藏, also collectively referred to with the Chongning Canon 崇寧藏 as the Fuzhou Canon 福州藏, see (Chi 2021). |

| 2 | In the past decade, scholarly interest has focused on the phonetic and semantic glosses appended to fascicles in the Qisha Canon 磧砂藏 and Sixi Canon 思溪藏. Notable examples include:

|

| 3 | As noted by Zhouyuan Li, the phonetic glosses in the Qisha Canon share a lineage with those in the Sixi Canon and the Fuzhou Canon. Many studies on the Qisha Canon’s glosses, in fact, trace back to earlier materials found in the Fuzhou Canon. See (Z. Li 2021, p. 119). So far, only one specialized study has explored the linguistic value of the glosses in the Fuzhou Canon. See (Tan 2023). |

| 4 | See (Li and He 2003, pp. 217–18), which also note that the Pilu Canon contains glosses. |

| 5 | In the organization of many Chinese Buddhist canons, including the Pilu Canon, fascicles were often grouped according to the Thousand Character Classic 千字文 system—a traditional Chinese method that assigns a unique character from the Thousand Character Classic to each fascicle, following its sequence. This mnemonic device facilitated both cataloguing and retrieval, especially in large-scale xylographic or manuscript collections. The “Yanzi fascicle 筵字函”, for instance, derives its designation from the character 筵, which appears at a particular position in the sequence. |

| 6 | The image is sourced from item no. 1069 in the “Zi bu Shijia lei 子部釋家類” (Buddhist Section, Subcategory: Śākyamuni Teachings) held by the Shoryobu (Archives and Mausolea Department) of the Imperial Household Agency of Japan. Reference URL: https://db2.sido.keio.ac.jp/kanseki/bib_frame?id=007075-4829&page=4 (accessed on 15 March 2025). |

| 7 | Regarding canonical format terms such as “cover title”(外題 waiti), “incipit title” (內題 neiti), and “colophon title” (尾題 weiti), see (Nozawa 2015, pp.109–11). |

| 8 | See CBETA, T13, no. 419, p. 920a3. |

| 9 | Since most of the characters in Table 2 are variant characters that cannot be entered using standard input methods, image have been employed as a substitute method to ensure accurate presentation. |

| 10 | Zhongjing mulu, scroll 2, CBETA, T55, no. 2148, p. 193b22: “the Sūtra of the Bodhisattva Bapo, one scroll (containing four initial sections, thirteen sheets).”. |

| 11 | The content of the Qisha Canon and the Hongwu Southern Canon is generally consistent. Variations are presented through footnoted textual comparisons. |

| 12 | The preface to the same work lists the following thirty-one canons: Kaiyuan shijiao lu 開元釋教錄, Fangshan Stone Canon 房山石經, Zhenyuan Catalogue of Buddhist Teachings 貞元新定釋教目錄, Zhiyuan fabao kantong zonglu 至元法寶勘同總錄, Outline of the Buddhist Canon 大藏經綱目指要錄, Dazang shengjiao fabao biaomu 大藏聖教法寶標目, Zhaocheng Canon 趙城金藏, Recarved Goryeo Canon 再雕高麗藏, Abridged Kaiyuan Catalogue 開元釋教錄略出, Fuzhou Canon 福州藏, Zifu Canon 資福藏, Qisha Canon 磧砂藏, Puning Canon 普寧藏, First Engraved Southern Canon 初刻南藏, Tianhai Canon 天海藏, Yuanshan Canon 緣山藏, Yongle Southern Canon 永樂南藏, Yongle Northern Canon永樂北藏, Jiaxing Canon 嘉興藏, Long Canon 龍藏, Huangbo Canon 黃檗藏, Manji Canon 卍正藏, Taiwanese edition of Zhonghua Canon 臺灣版中華大藏經, Taishō Canon 大正新修大藏經, Mainland edition of Zhonghua Canon 大陸版中華大藏經, Daming shijiao huimu yimen 大明釋教彙目義門, Yuezang zhijin 閱藏知津, Condensed Canon 縮刻藏, Pinjia Canon 頻伽藏, Puhui Canon 普慧藏, and Buddhist Canon 佛教大藏經. |

| 13 | According to the collation notes in the Taishō Canon, the notation “wu 無” indicates that this line is absent in the Song, Yuan, and Ming editions. |

| 14 | See Taishō Canon, T55, no. 2154, p. 574a26-b3. |

| 15 | Kaiyuan shijiao lu 開元釋教錄, scroll 20, reads: “Zhongjing mulu, seven juan (sixty-three sheets), compiled by the monk Fajing of the Sui dynasty 眾經目錄七卷 (六十三紙) 隋沙門法經等撰” (CBETA 2025.R1, T55, no. 2154, p. 722b4). |

| 16 | Kaiyuan shijiao lu, scroll 20, also states: “Zhongjing mulu, five juan (compiled in the second year of the Renshou reign of the Sui dynasty by imperial order, by Tripiṭaka translators and scholars, eighty-four sheets) 眾經目錄五卷 (隋仁壽二年勅翻經沙門及學士等撰八十四紙)” (CBETA 2025.R1, T55, no. 2154, p. 722b8). |

| 17 | The first nine scrolls of Dazang shengjiao fabao biaomu 大藏聖教法寶標目 contain summaries from the Kaiyuan shijiao lu, while the latter half of scroll nine includes newly added entries from the Zhenyuan lu. Scroll ten catalogues new translations from the Song dynasty and compositions from the Tang and Song. See (Chen 2008, p. 124). |

| 18 | See Dazang shengjiao fabao biaomu, scroll 9 (CBETA 2025.R1, L143, no. 1608, p. 680b5-6). |

| 19 | See ibid., p. 680b14-15. |

| 20 | See Photolithographic Reprint of the Goryeo Canon 景印高麗大藏經, vol. 31, p. 613a. |

| 21 | Regarding the Jingtai lu, Shiqiang Chen notes: “In both the preface and the scroll one colophon, there are two erroneous attributions to ‘compiled by Fajing, Tripiṭaka translator of the Sui dynasty, in the fourteenth year of the Kaihuang reign.’” See (Chen 2008, p. 52). |

| 22 | The Zhongjing mulu, under its “General Record 總錄”, reads: “On the fourteenth day of the seventh month of the fourteenth year of the Kaihuang reign, Buddhist monks including Fajing at Daxingshan Monastery engaged in scripture translation.” According to the Taishō Canon collation notes, this line is not present in the Song, Yuan, and Ming editions (T55, no. 2146, p. 149a26-27). |

| 23 | See Facsimile Edition of the Goryeo Canon, vol. 67, p. 373. |

| 24 | See “Japanese Old Sutra Manuscripts Database—Detailed Images,” https://koshakyo-database.icabs.ac.jp/resources/viewer/19792 (accessed on 10 July 2025). |

| 25 | See ibid. |

| 26 | See the “Ancient Books and Rare Literature Resources” database 古籍與特藏文獻資源, https://rbook.ncl.edu.tw/NCLSearch/Search/SearchDetail?item=186f97c3d1bd4f39b42c8b3b77a67faafDI5NzA2Ng2.VjqverFQ4a2ODTEVSEeVdRlUG9bFY8NApzR34yAVTcg_&image=1&page=&SourceID=0&HasImage= (accessed on 23 March 2025). |

| 27 | According to the explanation by Zhang Wenbin in the Online Dictionary of Chinese Character Variants, the character “筞” is a variant form of “策”. See https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/dictView.jsp?ID=32280 (accessed on 15 February 2025). |

| 28 | See Chu sanzang jiji 出三藏記集, T55, no. 2145, p. 15c1. |

| 29 | See Lidai sanbao ji 歷代三寶紀, T49, no. 2034, p. 117a18. |

| 30 | See Zhongjing mulu 眾經目錄, T55, no. 2146, p. 131a6. According to the critical notes in the Taishō edition, the character “遊” appears as “漩” in the Song, Yuan, and Ming recensions. |

| 31 | See Zhongjing mulu 眾經目錄, T55, no. 2147, p. 178c1. |

| 32 | See Dazhou kanding zhongjing mulu 大周刊定眾經目錄, T55, no. 2153, p. 380a11. The character “旋” appears as “㳬” in the Song, Yuan, and Ming recensions, as noted in the Taishō variant annotations. |

| 33 | See Kaiyuan shijiao lu 開元釋教錄, T55, no. 2154, p. 486a12. The character “旋” also appears as “㳬” in Song, Yuan, and Ming recensions. |

| 34 | See Kaiyuan shijiao lu 開元釋教錄, T55, no. 2154, p. 643a21. The character “從” appears as “㳬” in the Song, Yuan, and Ming recensions, according to the Taishō critical notes. |

| 35 | See Zhenyuan xinding shijiao mulu 貞元新定釋教目錄, T55, no. 2157, p. 783b4. |

| 36 | See Zhenyuan xinding shijiao mulu 貞元新定釋教目錄, T55, no. 2157, p. 978c17. |

| 37 | The author has not yet consulted the appended phonetic glosses 隨函音義 in the Puning Canon 普寧藏. |

References

Primary Sources

Ancient Books and Rare Literature Resources database 古籍與特藏文獻資源. Available online: https://rbook.ncl.edu.tw/NCLSearch/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).CBETA (Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association). 2025.R1. Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經, vols. T13, T49, T55, L143. Available online: https://www.cbeta.org (accessed on 25 July 2025).Facsimile of the First Edition of the Goryeo Canon 高麗大藏經初刻本輯刊. Seoul: Dongguk University Press.ICPBS (International College for Postgraduate Buddhist Studies) Old Buddhist Manuscripts in Japanese Collections Database 日本古写経データベース. Available online: https://koshakyo-database.icabs.ac.jp/canons (accessed on 10 July 2025).Kunaichō Shoryōbu 書陵部. 2016. Shoryobu (Archives and Mausolea Department) of the Imperial Household Agency of Japan 書陵部所蔵資料目録・画像公開システム.”. Available online: https://db2.sido.keio.ac.jp/kanseki/bib_detail?bibid=007075 (accessed on 15 March 2025).Ministry of Education, Taiwan. Online Dictionary of Chinese Character Variants. Available online: http://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw (accessed on 15 February 2025).Photolithographic Reprint of the Goryeo Canon 景印高麗大藏經. Taipei: Xin Wen Feng Publishing Co. vol. 31, p. 613.Secondary Sources

- Chen, Shiqiang 陳士強. 2000. Encyclopedia of Chinese Buddhism: Canonical Volume 中國佛教百科全書.經典卷. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shiqiang 陳士強. 2008. Annotated Catalog of the Buddhist Canon: Literary and Historical Volume 1 大藏經總目提要:文史藏(一). Shanghai: Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, Limei 池麗梅. 2021. A Centennial Review of Research on the Fuzhou Canon 《福州藏》百年學術史綜述. Buddhist Studies 1: 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- He, Mei 何梅, ed. 2014. A New Examination of Chinese Buddhist Canon Catalogues through the Ages, 歷代漢文大藏經目錄新考(下冊). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fuhua 李富華, and Mei He 何梅. 2003. Studies on the Chinese Buddhist Canon 漢文佛教大藏經研究. Beijing: Religious Culture Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guangkuan 李廣寬. 2016. On the Revisions of the Fanqie in the Phonetic Glosses of the Sixi Canon by the Qisha Canon 論《碛砂藏》對《思溪藏》隨函音義音切的修訂. Journal of Humanities 1: 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guangkuan 李廣寬. 2019. A Study of the Date of the Phonetic Glosses Appended to the Qisha Canon《碛砂藏》隨函音義產生時代考. Journal of Humanities 1: 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guangkuan 李廣寬. 2024. The Annotative Characteristics and Causes of the Phonetic Glosses in the Qisha Canon 《碛砂藏》隨函音義的注音面貌及其成因. Chinese Classics and Culture 5: 111–22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhouyuan 李周淵. 2021. A Centennial Review of Research on the Qisha Canon 《碛砂藏》研究百年綜述. Buddhist Studies 1: 105–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa, Yoshimi 野澤佳美. 2015. A History of the Printed Chinese Buddhist Canon: China and Korea 印刷漢文大藏經の歴史——中國・高麗. Tokyo: Rissho University Library. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, Kanichi 小川貫弌. 1984. The Formation and Transformation of the Buddhist Canon 大藏經的成立與變遷. In Shijie Fojiao Mingzhu Yicong 世界佛教名著譯叢. Taipei: Foguang Publishing, vol. 25, pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Daoan 釋道安. 1978. A Historical Account of Chinese Buddhist Canon Carving 中國大藏經雕刻史話. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Cui 譚翠. 2017. The Transmission of Kehong’s Glosses in the Song Dynasty from the Perspective of the Sixi Canon: With a Comparison to the Qisha Canon 從《思溪藏》看《可洪音義》在宋代的流傳——兼與《碛砂藏》隨函音義比較. Chinese Classics and Culture 3: 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Cui 譚翠. 2023. Examples of Colloquial Characters in the Phonetic Glosses of the Fuzhou Canon 《福州藏》隨函音義所見俗字舉隅. Language and Culture Forum 2: 235–40, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Ming 許明, ed. 2002. Collected Prefaces and Postscripts to Buddhist Scriptures in China: Han to Five Dynasties 中國佛教經論序跋記集.東漢魏晉南北朝隋唐五代卷. Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shiyi 徐時儀, Xiaohong Liang 梁曉虹, and Wuyun Chen 陳五雲. 2009. General Treatise on Phonetic and Semantic Glosses in Buddhist Scriptures 佛經音義研究通論. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Wensi 趙文思. 2017. A Study on the Colloquial Characters in the Phonetic Glosses of the Qisha Canon 《碛砂藏》隨函音義俗字研究. Master’s thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).