Abstract

This article’s primary aim is to present a highly localised body of evidence from two neighbouring small communities, Garway and Pencoyd, in the Archenfield area of the Welsh March. In Garway’s case, two documents from either end of the long fifteenth century show the local community condemning its parish priest, siding first with one authority and then another, and stressing its Welsh lineage. In Pencoyd, the remarkable survival of the local priest’s manuscripts shows him to have been a diligent pastor and teacher, in tune with diocesan expectations and connected to networks of learning on both sides of the border. Such a local study illuminates evidence of great interest in its own right, but also helps open up the possibility of a wider narrative that attends more fully to local experience in its variety and to the agency of local people.

Keywords:

Archenfield; Welsh March; borderlands; authority; church; clergy; laity; local community; manuscripts 1. Introduction

It is easy, in discussing the ecclesiastical and social history of the Middle Ages, to look down the wrong end of the telescope, as it were, and to retrospectively over-simplify its complex and changing patterns of identity and authority. The Welsh March is a case in point.

Politically, Offa’s Dyke, for instance, is clearly a highly important and very visible border marker, but it nevertheless also tempts us to anachronistically imagine a firm boundary, along the lines of a modern state border, between solidified entities called England and Wales. Current research projects are offering an alternative and more fluid picture of both the Dyke and the ‘frontier’ in general, emphasising the distinctive nature of the March and its change over time.1 Meanwhile, at a theoretical level, Linda Brady has challenged the over-narrow application of post-colonial theory to Anglo/Welsh relations leading to a binary picture of conqueror/conquered inequality (Brady 2018, p. 7), extending this further to examine fluidity of identity in the March in her introduction to a recent special edition of the Offa’s Dyke Journal on “Borders in Early Medieval Britain” (Brady 2022).2

At a political level, the English Marcher Lords held their lands on terms specific to the March which gave them quasi-regal authority there, even if they held land elsewhere in England; and their practical allegiance to the English Crown, to their fellow Marchers and to their Welsh neighbours could be a matter of negotiation (Davies 1978, pp. 38–39; Hume 2021, pp. 8–9). On the other side of the ‘border’, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, the Welsh ruler of southern Powys, having grown up in England, also, it seems, came to regard himself in a similar way. When native rule was ended after Edward I’s campaigns in Wales in 1277 and 1282–1284, Gruffudd retained his lands as a reward for allying with the English, becoming a native Welsh Marcher lord.3 Political jurisdiction, we might say, was a multi-player game with fluid rules.

At the level of language, Brady in her recent general treatment of multilingualism in early medieval Britain considered the “lived realities of communities where multilingualism likely existed on a daily basis”, using the Dunsæte Agreement to evidence both separation and collusion (Brady 2023, pp. 40–42), while B. G. Charles chronicled the history and persistence of Welsh place-names in Archenfield and Oswestry even into the nineteenth century in his O’Donnell Lecture (Charles 1963), noting that none of Offa’s Dyke, the Edwardian shiring, and the 1536 Act of Union should be construed as constituting linguistic demarcation lines.4

Ecclesiastically, the forthcoming celebrations of the 1350th anniversary of the establishment of the Mercian Diocese of Hereford,5 which might seem to take us back to the beginning, could divert our attention from nearly two centuries of prior British episcopal activity in the area,6 with allegiances that looked more west than east, and encourage us also to pass over the continuing complexities of jurisdiction which followed, from Gerald of Wales’ memorable ‘excommunication battle’ with the bishop of Llanelwy/St Asaph at Kerry over the see to which it pertained,7 to the contested authority in the late Middle Ages which we will examine below, to the law of 1563 which included the bishop of Hereford with his Welsh colleagues in a charge to arrange for the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer to be translated into Welsh, Welsh still being spoken in the Diocese, to the much more recent ‘border polls’ of 1915–1916 associated with the creation of the Church in Wales.8

Faced with these complexities, dedicated work on individual polities and people is proving a fruitful way forward, as exemplified by the recent work of David Stephenson (Stephenson 1984, 2016, 2019). In his 2019 volume, he provides “a step towards a sustained treatment of Welsh history in the central medieval period which breaks free from the fixation with princes … and notions of progress towards a principality of Wales as a process of liberation and unification. … It is perhaps time to open up new areas for investigation and, perhaps, subsequent debate” (pp. 31–32). As a result, Stephenson is able to identify that despite the hardship and oppression suffered by many, the rising class of Welsh administrators and community leaders who were essential to the governance of Wales enjoyed an age of opportunity.9 Stephenson’s latest study, on patronage and power in the medieval Welsh March,10 reminds us that in the “reconstruction of the March the Welsh population is often pictured as being of little account” and delves deeper to give us a micro-narrative of a gentry family, an “elusive” and under-studied but significant group.

In this spirit, the present article delves deeper still, with the primary purpose of presenting a body of evidence at a yet more micro level of how the complex of authority and identity led to different outcomes in two neighbouring villages in the border locality of Archenfield–evidence provided by the collocation of a chance survival of the fifteenth century manuscripts from one parish priest, and surviving records from a nearby parish from the very end of the fourteenth and very beginning of the sixteenth century, which illustrate the contested relationships there between the priest, the parishioners, and the wider authorities of the diocese and the Order of St John.

The scarcity of such surviving evidence, and indeed the probable sparsity of such evidence anyway, means that such a micro-study cannot of itself easily lead to wider conclusions, though some will be speculatively offered; but in a way, that is the point. Unless such localised evidence as does survive is first carefully curated on its own terms, such complexities of the situation that can be discerned will not be revealed, and only when a spread of them is available can a wider narrative be ventured that takes account of their diversity. What then is the evidence, and, given its limited nature, what if anything might it point to in helping us understand how the “blurred boundaries and contested authorities” played out in these two small places?

2. Archenfield

It will help at this point to place our villages geographically, and to also very briefly chronicle the context of their political and ecclesiastical history, which sets the scene for what follows.

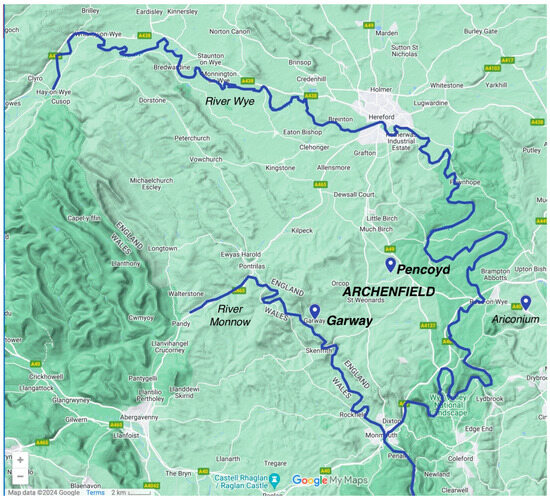

Figure 1.

Location map (Map data ©2024 Google).

The small settlements of Garway and Pencoyd lie some 15 miles south of Hereford in the area known as Archenfield, between the Rivers Wye and Monnow (see Figure 1). Although now firmly part of the Diocese of Hereford and of Herefordshire, neither of those identities held in the early medieval period before diocese and county were established. Archenfield derives the first part of its name from Ergyng, the post-Roman and pre-Saxon kingdom of the area, which also included lands east of the Wye, itself named after the Romano-British settlement at Ariconium (Coplestone-Crow 2009, pp. 11–15), and given in the Book of Llandaff (see below) as the see of St Dubricius and his successors.

Mercian expansion into the area did not fully over-write these earlier identities either politically or ecclesiastically. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle interestingly still refers to a Bishop of Archenfield, Cyfeilliog, who was ransomed from the Vikings by Edward the Elder in 914, and Charles-Edwards speculates that even under English rule, a Welsh-speaking bishop, perhaps primarily based in Gwent, was ministering to this largely Welsh-speaking area of the by then well-established Diocese of Hereford presumably at the request of its diocesan (Charles-Edwards 2012, p. 594). The Ordinance concerning the Dunsæte (an Anglo-Saxon term for hill settlers here applied to the hilly region bordering the Wye) lays out regulations for dealings between English and Welsh people in this area or one near it and reveals “a community that worked together to solve its problems, had a system of legal rights and responsibilities for all its members, and possessed a functional level of both linguistic and legal comprehension between its Anglo-Saxon and Welsh inhabitants”.11 As Luke Lambert concluded in his recent paper to the International Congress on Medieval Studies, ‘Ergyng to Archenfield: National Identity in an Early Medieval Borderland’, “Nationality for those around an early medieval borderland such as the border between England and Wales was marked with fluidity. Settlers from either side of the border moved across it often. Self-determination coupled with continued tradition, it seems, were the keys to national identity in an early medieval borderland such as Archenfield”.12

2.1. GARWAY

After the Norman Conquest, the Domesday Book names Garway as Lagademar in Arcenefelde (Thorn et al. 1983, 1.50; Powell-Smith 2024), and gives the region special treatment reflecting its ambivalent status.13 On the ecclesiastical front, the Book of Llandaff,14 written after a disagreement between Urban, Bishop of Llandaff (cons. 1107) and the bishops of St David’s and Hereford regarding the boundaries of his diocese, unsurprisingly aiming to strengthen its property rights, and also unsurprisingly manipulating the evidence in its favour, perpetuates the memory of an earlier identity by refreshing the record that c. 615 at Lann Guorboe—the church of (St) Guorboe—“Gwrodw, King of the region of Ergyng, gave, in exchange for a heavenly kingdom, to God, and to St Dubricius, and his congregation, and his church of the southern portion of the island of Britain, and in the hand of Bishop Ufelwy, and to all his successors in the place, for ever, a field, that is an uncia of land, with all its liberty, and all commonage in field and woods, in water and in pastures; and going round the land, the holy cross with the sacred relic being carried before, and with sprinkling holy water, he erected, in the midst thereof, a building in honour of the Holy Trinity, and there placed his minister Gworwog to remain to perform service for the benefit of the church” (Rees and Teilo 1840, pp. 407–8, Latin text pp. 153–54. See also Birch 1912, p. 119).

The identification of Guorboe with Garway is contestable, as with so much of this early evidence (Coplestone-Crow 2009, pp. 92, 103–4; Guy 2018, p. 24). Charles-Edwards has, however, examined the charter evidence in the Book of Llandaff in detail, including that for Guorboe, which he places among an early and relatively trustworthy seventh-century group, admittedly adapted to support the claims of Llandaff, and accepts it as Garway despite the alternative views.15

By 1187, we find Henry II pardoning the Templars for assarting (clearing for farmland) 2000 acres in ‘Garewi’, the right to the land being confirmed in 1189 by Richard II (Tapper 2005, p. 24; Lees 1935, pp. 139–40, 142–43). I take this to be not a punishment but a way of granting the Templars the right to clear and farm ‘forest’ of little other use to the Crown and erect a castellarium, introducing a new layer of authority to the area useful to the Crown and enhancing the stability of the area, adding a further layer of bespoke political complexity. The new arrangement will have been less attractive to the Diocese, as the Templars had extensive papal exemptions from diocesan authority, and the church was effectively appropriated by them with exemption from tithes and many dues (as this was a fund-raiser for them, not a military outpost).16 The situation was further complicated when the Templars fell from grace in 1308, and—after a short period of uncertainty—their estates including that at Garway passed to the Hospitallers by 1324, with similar privileges, being held by them until their own disbandment in 1536/7. The Hospitallers seem to have begun well, putting some buildings in order, but by 1512 the estate is being let to the Mynors family of (and still of) nearby Treago castle, many buildings being ruinous, and the responsibility then passed to them to find a chaplain to provide services and pastoral care for the parishioners (Marshall 1927, p. 89). The dispute between the diocese and the Hospitallers rumbled on, nevertheless, well into the sixteenth century (O’Malley 2005; Nicholson n.d., p. 99).

Garway Church seems to have remained a place of worship for the local parishioners as well as the Orders, and as well as the Orders’ position as landlords, there is likely to have been some sharing of ministry by their chaplains and, as we shall see, some conflict about visitation rights.17 It is that that sets the scene for the local events and records with which this article is principally concerned.

2.2. PENCOYD

There is much less that can be said about Pencoyd, which is “a very rural hamlet with a scattering of properties in beautiful countryside” (Llanwarne Parish Council Website n.d. (accessed on 22 August 2024)), nearly adjacent to Garway, not part of that Hospitaller estate but including part of Harewood End where their Harewood preceptory and chapel was situated, so still very much within their ambit. Ecclesiastically, in the Middle Ages it was a chapelry of Sellack, so there are no institution records for the chaplains serving it, and the Bishops’ Registers for 1492–1504 are anyway lost. It was one of four manors in Sellack, but no records survive.18 The church which the Pevsner guide describes as “of limited interest” contains a thirteenth-century font and ledger stone, with a fourteenth-century tower and much later rebuilding. The remains of a fifteenth-century cross stand in the churchyard (Brooks and Pevsner 2012, p. 550; National Heritage List for England n.d.).

In 1397, the parishioners raised a complaint about one David Wille who “withholds 4 pence, due every year for a certain meadow that he holds towards the upkeep of the light before the image of the crucifixion, and has withheld it for nine years past”, the clerk noting that he was sick, and who also as “executor of Hugh, his son, owes on behalf of the same deceased 16 pence for the benefit of the church, which he refuses to pay” (Forrest and Whittick 2023, p. 55). It is a single and isolated case, and there appear to have been extenuating circumstances, but it looks ahead to one of the items in the Pencoyd manuscripts which probably shows the parish priest noting a number of such small dues, and perhaps also suggests the possibly precarious position of the chaplain who needed to collect them while more substantial revenues went elsewhere.

It is now to the manuscripts that we must turn.

3. The Manuscript Evidence

This section presents documentary and manuscript evidence relating to the Archenfield villages of Garway and Pencoyd that illustrate the contested nature of ecclesiastical authority in the area and the way in which the two places responded—very differently—to this. The material also demonstrates the persistence of Welsh names in the area, offering lists of residents that may be of use in further studies. Our focus will be on three sources, all of which name individuals and illustrate in different ways patterns of authority and relationships between the clergy and the local laity: first, the entry for Garway in the record of the 1397 Episcopal Visitation of the Diocese of Hereford by Bishop John Trefnant, which is extant in manuscript HCA 1779 in Hereford Cathedral Archives (fol. 5r) and recently edited and published by Ian Forrest and Christopher Whittick (Forrest and Whittick 2023); secondly, the record of the Inquisition held at Garway in 1504 “as touchyng the jurisdiccion within the lordship of Garwey, beyng in veriance betwene the Byshope of the diocese of Herfforde [Richard Mayhew] upon the oon partie and the Lord of Saint Johns and his bredren upon the other partie” entered with the Hospitallers’ accounts for the area (HARC A63/III/23/1 fol. 18v); and thirdly, standing in time between the two Garway records, six extracts from the contents of three manuscript books that belonged to and contained entries made by Sir John Davyys,19 priest c. 1492–4 of nearby Pencoyd, which are a remarkable survival now held in the Bodleian Library at Oxford (MSS Douce 60, 103, and 108).

The records will be presented first and then discussed together in the next section.

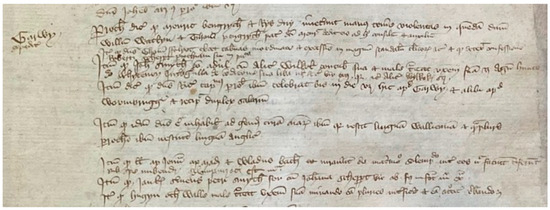

3.1. The 1397 Episcopal Visitation of the Diocese of Hereford by Bishop John Trefnant, MS HCA 1779 fol. 5r

Hereford Cathedral Archives (HCA) 1779 is a quarto-size paper book of 26 folios (two quires) within a parchment cover, which shows the signs of having being folded vertically, presumably for ease of transport by the diocesan registrar or his clerk, as they accompanied the episcopal party as it held visitation courts at some 59 locations around the diocese to receive presentments from nearby parishes and made contemporaneous notes of the proceedings in the document as well as later notes on subsequent judicial process.20 The modern editors have noted that “[v]isitation records offer historians an unrivalled means of studying the interactions between episcopacy, clergy and laity and the ways in which they shaped social and religious life” (Forrest and Whittick 2016, p. 738), and describe this present document as “arguably the most detailed and interesting record of visitation proceedings to survive from late medieval England” (Forrest and Whittick 2016; 2023, p. xli). The entry in which we are particularly interested in this article is that for Garway (held at Garway) on fol. 5r.

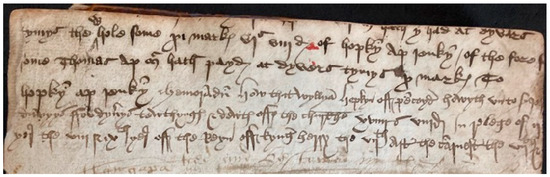

Figure 2.

HCA 1779 fol. 5r (extract). Photo by author.

- TEXT of the record of presentments made at the 1397 Visitation with respect to Garway translated from HCA 1779 fol. 5r (see Figure 2).

The parishioners say that Meurig Bengrych and Rhys Duy laid violent hands without good reason on a certain Sir William Watkyn, and that Thomas Pengrych, the father of the said Meurig, gave them counsel and aid.

Next, that Sir Thomas Folyot frequents taverns in an unruly and excessive manner, to the great scandal of the clergy etc., and that he revealed the confession of Robert Scheppert, his parishioner, in public.21

Next, that John Smyth, a married man, commits adultery with Alice Wilkok, his concubine, and mistreats his wife, namely Agnes Hunte of Whitney; this woman questioned about her condition, whether a free woman or etc.; the man excommunicated because etc.; Alice Wylkok suspended.

Next, that they say Sir Richard, parish chaplain there, celebrates twice in a day, namely here at Garway and elsewhere at Wormbridge, and he receives a double salary.

Next, that the same Sir [Richard] is unsuitable to perform the cure of souls there, because he does not know the Welsh language, and most parishioners do not know the English language.22

Next, that Llewelyn ap Iuean ap Madog and Gwladus Bach swore that they would have marriage solemnised between them and they have not done so. Deferred in the hope of them marrying; the marriage has been solemnised.

Next, that Jankin, servant of Peter Smyth, fornicated with Joan Scheppert. The man abjures, to be beaten in due form; the woman outside.

Next, that Hugyn oth’ Walle mistreats his wife, often threatening to kill her and beating her terribly.23

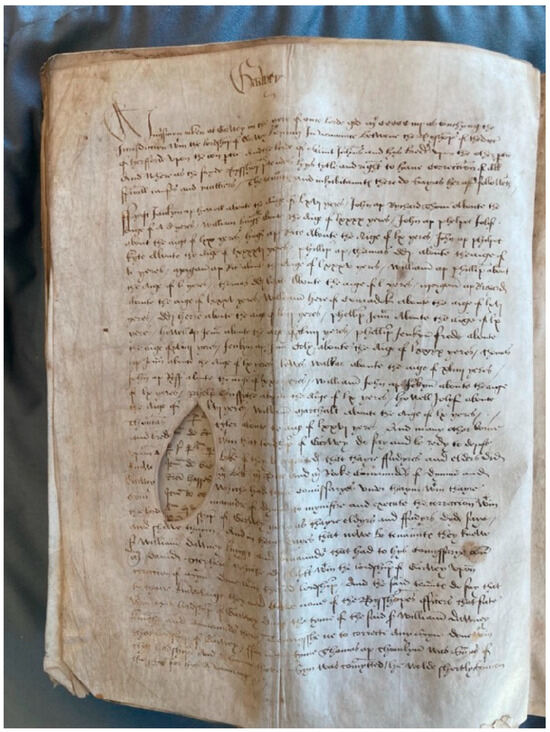

3.2. A Record of the Parishioners’ Deposition at the 1504 Inquisition at Garway Concerning a Dispute between the Bishop and the Grand Prior of the Hospitallers

Herefordshire Archive and Record Centre (HARC) A63/III/23/1 is a parchment quarto book bound in a vellum cover kept among the archive of the Hampton Court (Herefordshire) estate at HARC, and is principally a rental roll of the Dinmore and Garway Hospitaller preceptories and their subsidiary houses, made in 1505 and renewed in 1528/29. Included in the volume is a copy in English recording the parishioners’ deposition at an Inquisition at Garway in 1504 concerning a dispute between the Bishop and the Grand Prior of the Hospitallers, which is remarkable for its list of the parishioners’ names and ages. The Inquisition was part of a long-running legal battle between the Bishop and the Grand Prior, which is catalogued in Bishop Mayhew’s Register (Bannister 1919a), as well as in the Hospitaller accounts. The Garway quarrel was resolved to some extent in 1509 when the Prior agreed to an annual payment to the Bishop (recorded on the first page of the current manuscript), but the overall conflict was still running in 1521 when Bishop Charles Bothe and Grand Prior Thomas Docwra were in correspondence about the Bishop’s ordinary jurisdiction over Garway, the conduct of clandestine marriages by the curate there, and the celebration of communion at Easter for parishioners of other parishes.24

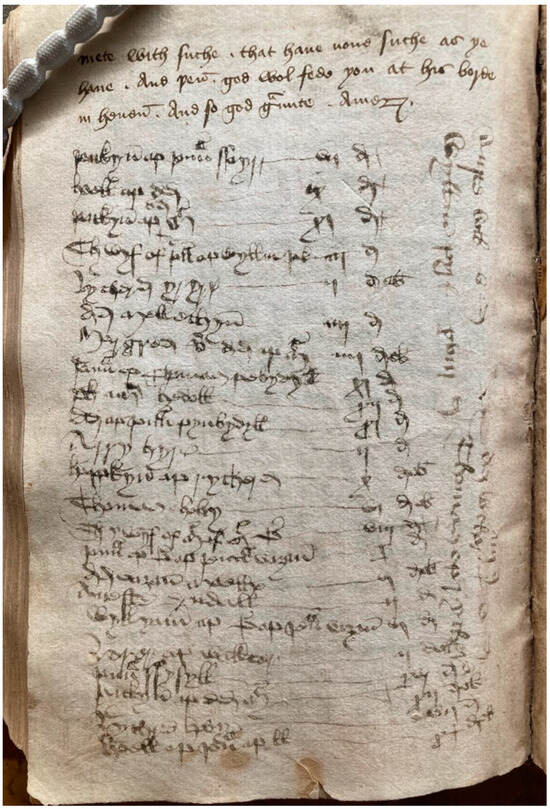

Figure 3.

HARC A63/III/23/1 fol. 18v. Photo by author.

- TEXT of the record of the Parishioners’ Deposition at the 1504 Inquisition at Garway from HARC A63/III/23/1 fol. 18v (see Figure 3).

Inq[ui]sicion taken at Garwey in the yere of oure lorde god Ml CCCCC iiij as touchyng the Jurisdiccion w[ith]in the lordship of Garwey Beying In veriaunce Betwene the Byshope of the dioc[ese] of Herfforde upon the oon’ p[ar]tie And the lorde of Saint Johns and hys Bred[ren] upon the other p[ar]tie And Where as the sayde Bysshop p[re]tendes hys tytle and right to have Correctio[u]n of all spi[rit]uall causes and mattiers The tenantes and inhabitauntes there do Say as her aft[er] followeth.

Fyrst Jankyn ap Howell aboute the aige of lxvj yeres, John ap Rychard Thom[as](?) aboute the aige of a C yeres, William Hugh aboute the aige of lxxxx yeres, John ap Phelpot Jolif about the aige of lxx yeres, Hugh ap Rice aboute the aige of lx yeres, John ap Philpot Kyte(?) aboute the aige of lxxxvj yeres, Phillip at Thomas D[avi]d aboute the aige of li yeres, Morgan ap Ric[hard] abut the aige of lxxxv yeres, William’ ap Phillip about the aiges of li yeres, Thomas D[avi]d Leya(?) aboute the aige of l yeres, Morgan ap Richard about the aige of lxxxv yeres, William’ Here of Cemadok aboute the aige of lxvj yeres, D[avi]d Herre about the aige of liiij yeres, Phellip Jeu[a]n about the aige of lx yeres, Howell ap Jeu[a]n about the aige of xliiij yeres, Phellip Jenkyn’ Frode aboute the aige of xliiij yeres, Jenkyn ap Jeu[a]n (?) Coly aboute the aige of lxxxx yeres, Thomas ap Jeu[a]n aboute the aige of lx yeres, Lewes Walkar aboute the aige of xliiij yeres, John ap Ross[er] aboute the aige of lxxx(?) yeres, William’ John ap Je[n]kyn’ aboute the aige of lx yeres, Phel[i]p Gruffythe aboute the aige of lx yeres, Howell Jolyf aboute the aige of lvj yeres, William Marchalt aboute the aige of lx yeres, Thomas Tyler aboute the aige of lxxvj yeres, And many other borne and brede w[ith]in that lordship of Garwey do say and be redy to depose upon a Boke if they be required that thayre Fadyres and elders did Knowe Mr Bett Mr P[it]te and Mr Rooke Com[m]aundo[ur]s of Dynmo[ur] and Garwey whiche had theyre(?) Comissaryes under thaym w[ith]in thayre Commaundre of Dynmo[ur] to mynistre and execute the correccioun w[ith]in the lordship of Garwey yerely(?) as thayre eldyrs and Fadyrs dyd saye and shewe thaym, And in thay[…](?) dayes that nowe be tenaunts they knewe Sir William Dawney Knyght and Comaundo[ur] that had to hys Comyssarye oon’ Mr David Stephens whiche dy[d] Sytt w[ith]in the lordship of Garwey vpon coreccion of Syn Done w[ith]in the said lordship, And the said ten[a]untes do say that to thaire knowlaige they nev[er] knewe none of the Bysshopes officers that sate w[ith]in that lordship of Garwey duringe the tyme of the said Sir William’ Dawney Knight and Comaundo[ur] there To [mony]ysshe ne to correcte any Syn done w[ith]in that lordship of Garwey, For in the tyme Thomas ap Thomlyn’ was Su[m]no[ur] of that lordship and whanne that a Syn was com[m]ytted, he wolde shortly Sum[m]on the p[ar]ties for hys Avauntaige etc.25

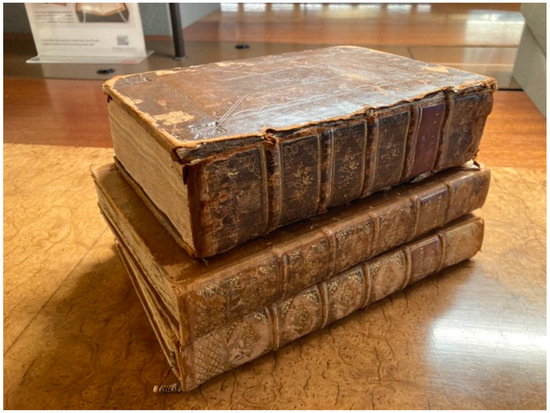

3.3. Three Manuscripts in the Possession of Sir John Davyys of Pencoyd c. 1492–4: University of Oxford, Bodleian Libraries MSS 60, 103, and 108

This group of manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (shown in Figure 4) are typical of working books that might be used by local clergy/schoolteachers in the fifteenth century, octavo in size, often made up from smaller quires or “booklets” and containing a variety of useful texts, usually surrounded by additional material and notes.26 The present three volumes, written by a number of hands, were compiled in the mid-fifteenth century, and internal evidence supports the hypothesis that they came into the possession of Sir John Davyys, priest c. 1492–1494 of Pencoyd, some six miles from Garway, who added additional material to them. Pencoyd was a chapelry within the benefice of Sellack, and Davyys was presumably an assistant chaplain there, Thomas Were being the incumbent at that time (Lockie 2021: https://www.melocki.org.uk/diocese/Sellack.html (accessed 18 September 2024)). As an assistant, Davyys does not appear in the diocesan register of institutions as Were does, but a John Davies is listed as ordained acolyte and subdeacon in 1490, and then deacon in 1491 on the basis of a title at Aconbury Priory which is only about three miles away,27 and this could well be our man.28

Figure 4.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [2024] MSS Douce 60, 103, and 108. Photo by author.

The main contents of MS Douce 60 are John Mirk’s Festial (a compendium of Middle English sermons for the whole year suitable for parish use) (Mirk and Powell 2009, vol. II), and the same author’s Instructions for Parish Priests in Middle English verse (Mirk 1868), both eminently suitable handbooks for a parochial chaplain.

MSS Douce 103 and 108 were once a single volume and contain further copies of both the Instructions and the Festial, the latter being closely related to the text in MS 60 (Mirk and Powell 2009, vols. I lxx–lxxi), together with texts in both English and Latin for teaching grammar, lists of feasts, and explanatory notes on liturgical texts in use in the Diocese of Hereford, also all of very practical use to a parish priest of that diocese.29

Six excerpts are presented below.

3.3.1. A Memorandum of Sums Owing to Sir John Davyys for 1492–94

The additional material in manuscripts of this sort often helps to establish their provenance and offers insights into their context.30 MS 60 contains an added memorandum on fol. 228v about tithes and duties owing to John Davyys, which underpins the hypothesis that the book (and the handwriting of this note, a rather scruffy ‘mixed’ hand, more suited to everyday notes than formal book-writing) was his.

Figure 5.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [2024] MS Douce 60 fol. 228v. Photo by author.

- TEXT of John Davyys’ memorandum from MS Douce 60 fol. 228v lines 3–5 (see Figure 5).

Memorandum how that Wyllyam Hopkyn’ off Pencoyd’ howyth vnto Sir Ioh(n) Davyys for dyuerys tewthyngis and dewtis off’ the churche xviiij s viij d’ in plege of ij’ yere the viij and ixth yer off’ the reyn’ off’ kyng Herry the vijth after the conquest’ the vijth and < >.31

3.3.2. A Note of Individuals and Amounts of Money Recorded by Sir John Davyys

On fol. 146v of MS Douce 60 is a more substantial financial note, which includes the names of some 27 individuals who have given, owe, or just possibly are receiving small sums of money, with many of the names showing typically Welsh forms. These are also probably church dues along the lines of the money owed by David Wille in the 1397 Visitation noted above. (A list of names of pupils at Basingwerk Abbey school survives in another schoolbook of similar date with monetary amounts next to them,32 but the sums here are larger, and the names include women, including two wives and a widow, who at that time would have been unlikely grammar pupils.)

- TEXT of John Davyys accounts from MS Douce 60 fol. 146v (see Figure 6).

| Jonkyn ap Jovan Sayrr | vij d | Sayrr: carpenter |

| Hoell ap Dauid | ix d | |

| Jankyn ap Dauid Mereduth | xj d | Dauid inserted in same hand; Mereduth: or Mawr? |

| Th[e] wyf of Ioan ap Wyllm Jak | iiij d | |

| Rycherd Yr Yri | ij d ob | Yri: Snowdon |

| Dauid Mellethyn | iiij | Melle: maelhe = yellow |

| Margred verch Dauid ap Mereduth | iiij ob | |

| Iavan ap Thomas Pebydyll | xi d | |

| Phelip ap Mereduth Hedoll | xij d | |

| Dauid ap Iovan Pynbydyll | xj d | |

| Arry Hyr’ | ij d | |

| Hoppkyn ap Rycherd | x d ob | |

| Thomas Hoby | vj d ob | |

| Th[e] wyf of Mereduth of Mer’ T’ | viij d | Th[e]: MS Th Y; of: or ap |

| Iavan ap P’ ap Jevan Vaʒan | x d | P’: or possibly B; Vaʒan: Vaughan (vachan = small) |

| Dauid Vaʒan Maelhe | vj d ob | |

| Aneste Dyndall | ij d | Aneste is female. Dyndall: ‘blind’ but here = Tyndall? |

| Wyllyam ap P’ ap Ievan Vaʒan | vj d | P’: or possibly B |

| Rorer ap Wallter | ij d ob | |

| Iavan Sysyll | xvj d | MS ssysyll |

| Jankyn ap Dauid Mereduth | xij d ob | Mereduth: or Mawr? |

| Rychard Hoby | vij d | |

| Hoell ap Ioan ap Llywelyn | x d ob | |

| Written vertically down the right hand side: | ||

| Aneste Boll | v d | Bol: or Voll |

| Dauid W’char* | v d* | word lost before David? v d: iiij d above in same hand |

| Wyllm Pyri* | xviij d | |

| Thomas ap Rycherd33 | ||

Figure 6.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [2024] MS Douce 60 fol. 146v. Photo by author.

3.3.3. An Example of Grammar Teaching Given by Sir John Davyys

Amongst the items added to MS Douce 103, also in Davyys’ hand, is a copy of the English Accedence, the most elementary of the grammar texts in English that began to circulate in the late fourteenth century, deriving from the teaching of John Leylond in Oxford, but as with other similar practical and even literary texts of the period showing repeated re-writings as they passed from hand to hand (Thomson 1979, pp. 4–22). The dialect of the text has been analysed, and forms such as ‘mony’ for ‘many’ locate it in the West Midlands (Stenroos 2016, pp. 100–25 at 121).

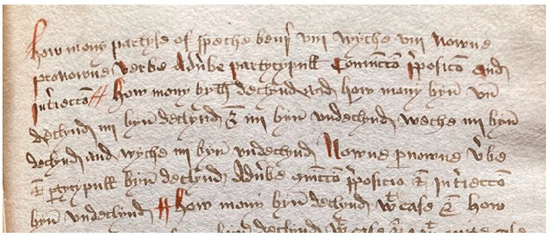

Figure 7.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [2024] MS Douce 103 fol. 53r. Photo by author.

- TEXT of the opening of the Accedence from MS Douce 103 fol. 53r (see Figure 7).

How mony partyse of speche ben þer? VIII. Wyche viij? Nowne, pronowne, verbe, aduerbe, partycypull, coniunccion, preposicion and interieccion. How mony byth declynd and how mony byn vndeclynd? IIII byn declynd and iiij byn vndeclynd. Weche iiij byn declynd and wyche iiij byn vndeclynd? Nowne, pronowne, verbe and partycypull byn declynd, aduerbe, coniunccion, preposicion and interieccion byn vndeclynd.34

3.3.4. An Example of an Exposition of a Liturgical Text Used by Sir John Davyys

“Expositions” (re-wordings into simpler Latin, in prose, sometimes with translations) of liturgical material to help those joining religious communities (and others) to understand their services go back in England to the Anglo-Saxon period, and the one printed here and others in the collection are found for instance in British Library, MS Cotton Vespasian D. xii, made for Christ Church, Canterbury in the mid-eleventh century (Pulsiano 1996, p. 23; Gneuss 1968).

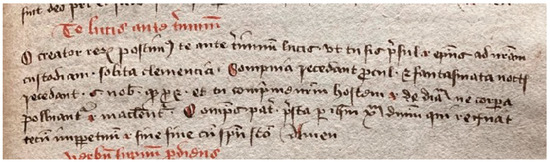

Figure 8.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [2024] MS Douce 103 fol. 37r. Photo by author.

- TEXT of the Exposition of Te lucis ante terminum from MS Douce 103 fol. 37r (see Figure 8).

| Te lucis ante terminum | To thee before the close of day |

| Rerum creator poscimus | Creator of the world, we pray |

| Ut solita clementia | That, with thy wonted favour, thou |

| Sis presul et custodia | Wouldst be our guard and keeper now. |

| is re-worded to give the simpler | |

| O creator rerum poscimus te ante terminum lucis | |

| vt tu sis presul i.e., episcopus ad nostrum custodiam.35 | |

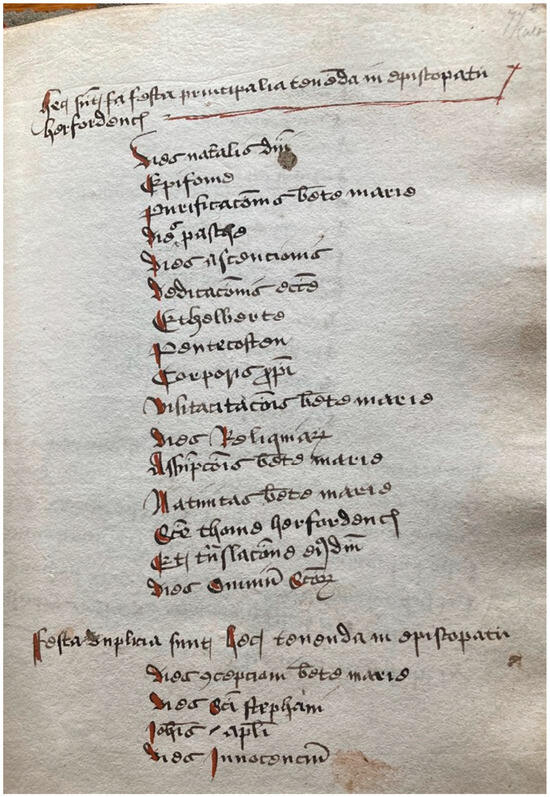

3.3.5. A List of Feasts to Be Celebrated According to the Hereford Use

In the Middle Ages, each Diocese had its own ‘Use’, which included not only the texts and instructions for the various services but also the Calendar, listing which feasts, fasts, and other solemnities were to be observed. While there is a broad similarity across the Western Church, local saints would for instance be given greater prominence, and newer feasts might or might not have been adopted, and older ones retired. A new parish priest would need to learn this information quickly, and lists such as these would be passed around. MS Douce 103 fols. 77br–78v and 117v–118v are examples of such lists. On the folio shown, note the inclusion of Ethelbert and Thomas of Hereford.

Interestingly, a similar list of Hereford feasts is also found in Peniarth MS 356B, mentioned above, even though that would not seem to be a Herefordshire manuscript (Thomson 1983b; W. Smith 2014).

- TEXT of a list of Hereford Feasts MS Douce 103 fol. 77br (see Figure 9).

| Hec sunt festa principalia tenenda | These are the principal feasts to be held |

| in episcopatu herfordencis: | in the Diocese of Hereford |

| Dies natalis domini | Christmas Day |

| Epifonie | Epiphany |

| Purificacionis beate marie | The Purification of the BV Mary |

| Dies pasche | Easter Day |

| Dies ascencionis | Ascension Day |

| Dedicacionis ecclesie | The Dedication of the Church |

| Ethelberte | St Ethelbert |

| Pentecosten | Pentecost (Whit Sunday) |

| Corporis christi | Corpus Christi |

| Visitacionis36 beate marie | The Visitation of the BV Mary |

| Dies reliquiarum | The Holy Relics (of the Church) |

| Assumpcionis beate marie | The Assumption of the BV Mary |

| Natiuitas beate marie | The Nativity of the BV Mary |

| Sancte thome herfordencis | St Thomas (Cantilupe) of Hereford |

| Et translacionis37 eiusdem | And his Translation |

| Dies omnium sanctorum38 | All Saints’ Day |

Figure 9.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [2024] MS Douce 103 fol. 77br. Photo by author.

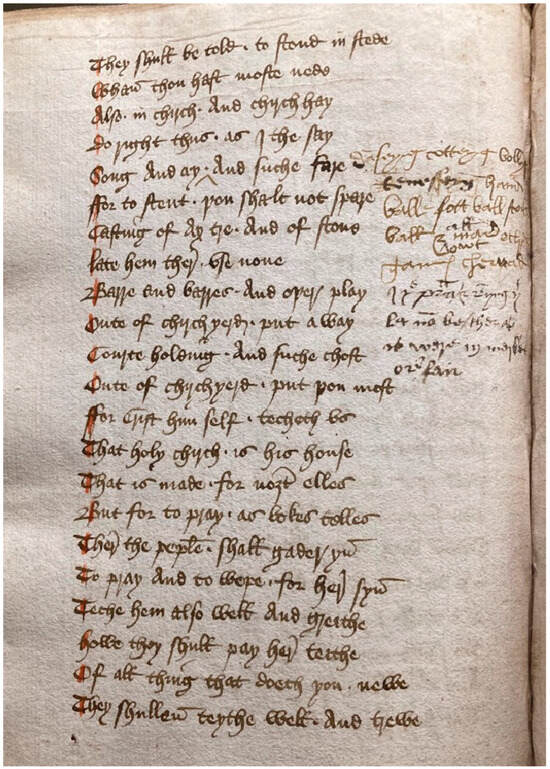

3.3.6. An Extract from a Copy of John Mirk’s Instructions for Parish Priests Used by Sir John Davyys Concerning Behaviour in the Churchyard

John Mirk (or Myrc) was a regular Augustinian canon based at Lilleshall in Shropshire and the author of at least three instructional manuals for local clergy, the Instructions for Parish Priests in English verse, of which we have an extract here, the Liber Festialis (Festial) offering sermons in English for use throughout the year, and a Manuale Sacerdotis (Priest’s Manual) in Latin. Seven copies of the Instructions survive, and its pragmatic approach must have appealed to a user like Davyys. The voice, of course, is Mirk’s, not his, and the manuscript hand is also probably not Davyys’ but a similar, tidier one, but both the Festial and the Instructions can be seen as popular, sensible, and probably effective choices of resources for someone in his position. Fol. 127v of this text covers the topic of inappropriate behaviour in the churchyard, and is written in such a way that it could be read out memorably to parishioners. A sixteenth-century hand has added further exhortation.39

Figure 10.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [2024] MS Douce 103, fol. 127v. Photo by author.

- TEXT of an extract of Mirk’s Festial from MS Douce 1–3, fol. 127v (See Figure 10).

| Also in church and church-hay | church-yard (hedged round) |

| Do right thus as I the say. | |

| Song and cry and suche fare | |

| For to stent þou shalt not spare | stent = stop |

| Casting of ax-tre and of stone | cart-axle |

| Late hem there vse none. | Let them |

| Balle40 and barres and oþer play | ‘bars’ = a prisoner’s-base game |

| Oute of chirchyerd put away. | |

| Courte holding and such chost | ‘c(h)ost’ = manner of action |

| Out of the churchyerd put þou must, | |

| For Crist him self techeth vs | |

| That holy chirch is his house | |

| That is made for nouȝt else | |

| But for to pray as bokes telles. | |

| There the people shall gader yn | |

| To pray and to wepe for here syn. | here = their |

| Teche hem also well and greithe | greithe = prepare |

| Howe they shall pay here tithe. | |

| Of all thing that doth you newe | you knew = renew itself41 |

| They shullen teythe well and trewe.42 | |

4. Discussion

With this evidence on the table, what observations and conclusions can we make that might bear on the question of how the “blurred boundaries and contested authorities” that are a mark of Archenfield’s history affected life there in the later Middle Ages, and in particular their relationship with the church and its clergy and their authority?

Despite the shared history and geographical proximity of the two villages, the evidence shows that their experiences were very different. This in itself is a salutary conclusion, reminding us that broader narratives can miss more fine-grained detail. I will look at Garway first and then Pencoyd.

4.1. GARWAY

In most dioceses, visitation records from the medieval period were destroyed after their cases were closed (Forrest and Whittick 2016, p. 739). In Hereford, however, some were preserved at least to some extent (ibid.; Forrest and Whittick 2023, p. 17), and the visitation record of 1397 is outstanding in its coverage and the degree of detail it offers. We can assume that what the visitation found was not in general terms unlike others of similar date, but given the thinness of the evidence, internal analysis is a safer way forward.

Nearly all the parish clergy referred to are given the title “Sir”, indicating a cleric who had not proceeded to take an MA—this is discussed further below—so Sir Richard is not unusual in this respect. Complaints about sexual misdemeanours are also very common (Forrest and Whittick 2023, p. xxxiv). In their index Forrest and Whittick give 13 other accusations that a parish priest celebrated mass twice in a day, half mentioning that this is in two different churches, but no others adding that it resulted in double pay. This also must have been quite common in a diocese with so many small parishes, whether driven by exigency or reward. The complaint that “Sir [Richard] is unsuitable to perform the cure of souls there, because he does not know the Welsh language, and most parishioners do not know the English language” is, however, unique.

In her account of the use of the Welsh language before 1536 (L. B. Smith 1997), Llinos Smith includes consideration of the use of different languages with varying degrees of competence in different contexts, although also citing a number of occasions when the documentary evidence records that someone spoke in one language because they did not know another, in a way that suggests to me that this was something of a well-known turn of phrase or topos. The Garway parishioners’ complaint about their priest is cited rightly by Smith as evidence for the use of Welsh beyond what we would now regard as the border, noting that the records of ecclesiastical courts from c. 1440 onwards show that there was substantial Welsh migration into the western deaneries of the Diocese of Hereford but also to the east (ibid., pp. 17–18). Drawing on detailed analysis by Michael Richter of the witness reports for the canonization of Thomas Cantilupe (Richter 1979, pp. 195–96), she reports his use of an interpreter when preaching in three townships, as well as the incident of the miracle by which a young man born without speech started to speak in both English and Welsh (and the interesting comments of those who did or did not understand the Welsh) (L. B. Smith 1997, pp. 12, 16).

That said, the complaint is not perhaps as straightforward as it looks, and what could be taken as the simple report of a pastoral problem could also be seen (in a cynical moment) as a power play by an apparently weaker party using the complexity of the linguistic situation and as a useful topos to exploit the alleged inadequacy of the priest and bolster their own position in the face of clerical authority. Parishioners with names like Robert Scheppert, John Smyth, Alice Wilkok, Peter Smith, and Joan Scheppert are unlikely to have been monoglot Welsh, so what does “most parishioners” really mean, and how thoroughgoing is “do not know”? Smith’s analysis of a multilingual environment in which speakers have some command of more than one language and deploy their competencies in different situations is convincing.43 Multilingualism was after all a feature of the 1397 Visitation and a necessity for its success (Forrest and Whittick 2023, p. xxxviii). In the context of the March, Helen Fulton’s recent work in this area is relevant (Fulton 2011a, 2011b; Fulton 2013), and the new research project Mapping the March: Medieval Wales and England, c. 1282–1550 (Fulton 2024), which she is leading, aims to “document and define a distinctive culture of the March, marked by multilingualism, conflict, emergent identities, and networks of readers and writers”.

Does the deposition recorded in HARC A63/III/23/1 show the same picture? The context this time is not the diocese directly, but the Order of St John (the Hospitallers) in whose book the record stands—significantly a rental roll—and the issue is overtly one of jurisdiction, but beneath that to do with its financial consequences. The deposers are the parishioners, but it is highly likely that their claims are being orchestrated by the Order.

So the same community that complained to the Bishop about its priest—possibly a chaplain employed by the Order—in 1397 is now in 1504 refusing the Bishop any visitatorial authority over them in favour of the Order’s Grand Prior (and in 1524 they were to dramatically bar the door to the Bishop’s successor) (Bannister 1921, p. 151). Much can happen in a century, even in a rural backwater, but the explicit appeal of the parishioners to longevity and tradition underlines the question as to why they came to act so differently.

It is worth digressing for a moment to note the list of names in the document—again a valuable and remarkable survival in its own right, but also noteworthy for, in 1504, still being almost uniformly Welsh in form. (The English names of the Hospitallers’ officers contrast significantly, though the summoner’s is Welsh, and we may imagine that this would be an advantage to him in his work.) Such a persistence of Welsh-form names is typical of the Archenfield area. Melville Richards makes it clear that this Welsh identity—and my sense is that this is a matter of identity as well as language—was a feature not just of Garway or Pencoyd but Archenfield more generally, including another nearby parish, Orcop (Richards 1970, pp. 89–90).

In the absence of evidence for the intervening period, we can only speculate. Being a tenant of the Order could bring financial benefits, and their churches came to provide spiritual care for residents near them whatever their legal position, Garway being one of the best documented of the legal battles which could follow, and one which also exemplifies the well-organised and resourced way in which the Order defended its privileges—in order, to be fair, to fulfil what we would now call its “charitable purposes”, which were to raise money for their work overseas (O’Malley 2005, pp. 96, 98, 99–100). But a further speculation might be that an underlying local attitude of resistance to encroaching authority, from whatever quarter, was being maintained, and in this case the opportunity was again being taken to play two competing authorities off against each other—a strategy that is not unknown in such areas and which casts a different light than a grand narrative that might presume that small remote communities caught between competing authorities were powerless victims.

4.2. PENCOYD

To turn now to Pencoyd, our evidence is confined to the group of three manuscripts, which I have identified as being in the ownership of Sir John Davyys, chaplain for the church there (it was a chapelry of nearby Sellack) c. 1492–1494. Here we encounter a very different picture of an apparently diligent priest engaging strongly with his parishioners and offering them both spiritual and educational support. The manuscripts taken together are a solid vade mecum for such a junior cleric, covering not just Mirk’s Festial and Instructions and the extracts shown but further grammatical and liturgical notes, with an emphasis on helping the reader understand the Latin he would encounter as a priest, along with a longer treatise on Equivoca explaining words which could be read in more than one way, such as Augustus.

Davyys’ surname suggests that he might be of Welsh lineage, as does the competent way in which spells the Welsh names of his parishioners, and I suggest that it is likely that he had some command of Welsh as well as English and Latin. This must have stood him in much better stead for ministry in Archenfield than Sir Richard at Garway. We should also note that although his parishioners’ names are still mostly in Welsh form, as the recipients of Davyys’ teaching and preaching in English, it seems that they were competent in and comfortable enough with English as a language of instruction and exhortation. He comes across as not just diligent but also as conformist. His use of Myrc’s work would have sat comfortably with the anti-Lollard concerns of the diocesan hierarchy, as would his teaching ministry and his care to follow and understand the liturgical patterns of the diocese: a very different approach to authority than that of the parishioners at Garway. Sadly, we are unable to say what became of him in later years; quite possibly he died young.

That Davyys was teaching or hoping to teach Latin to others, and not just using the English Accedence as an aid for himself, is a reasonable likelihood since it was created as an elementary pedagogical tool and derives from the teaching of John Leylond at Oxford, creating a tide of teachers and texts which flowed out across the country (Thomson 1979, pp. 4–22; 1984). It is possible that Davyys studied at Oxford without proceeding to an MA (if he had done, we would expect him to called Master/magister) and either following the arts course but only taking a BA or no degree at all, or perhaps simply studying grammar and its teaching in one of the schools on the periphery of the university.44 The lack of any indication of higher learning in the manuscripts suggests the latter.

We have already noted that “Sir” was the normal title given to parish clergy in the 1397 Visitation. The institution records of clergy in the Diocese of Hereford hardly ever mention any degree before the 1460s, and only rarely in the late fifteenth century, often in connection with a more senior appointment, and there were many chaplains alongside incumbents.45 In this sense, Davyys was not at all unusual, nor was he—in national terms—as the owner of a book containing Middle English grammars and allied texts: the closeness of the look and contents of his books to many others containing the same material places it firmly within the Leylond tradition, though the usual caveats about survival apply in trying to estimate the number and distribution of such books and teachers. What is interesting, though, is that Davyys is also in some sense part of another network, since two of the other books containing Middle English grammars are also from (in a generous sense) the Welsh/English borderlands. MS Peniarth 356B, which we have already noted, was the work of Thomas Pennant, Abbot of Basingwerk 1481–1522,46 while MS NLW4234D was written by John Edwards the younger of Chirk in the late fifteenth century (Thomson 1979, pp. 105–13). Pennant and Edwards were part of a circle of learning with an interest in Welsh Bardic grammars and inter-linguistic activity,47 and given the overlap of contents of Peniarth 356B particularly with MS Douce 103, it is reasonable to suppose some sort of connection, though not necessarily a direct or strong one with Davyys; but it would be dangerous to speculate further. What we can say, though, is that the marginal location of Davyys at Pencoyd did not prevent a surprising connectedness with the wider world of learning both in England and Wales. While hyper-localism is a common enough feature of deep rural and marginal communities, we are reminded that they also remain connected to wider society, even if they diverge in their attitude towards to it (an ambivalence that persists into the present day).

5. Conclusions

The aim of this article has been to present a highly localised body of evidence from two neighbouring small communities in the Archenfield area of the Welsh March that are of interest in their own right and can support further study, but which also exemplify the ways in which such communities negotiated and even took advantage of the blurred boundaries and contested authorities that mark them. The two places are shown to have responded very differently, one continuing what seems to have been a community tradition of contesting jurisdictions and setting them off against each other, that was quite willing to name its priest as useless, while the priest in the other parish diligently fulfils diocesan expectations and shares in a teaching ministry with links to learned networks on both sides of the border. Drilling down to this level offers us the chance to qualify and add nuance to higher-level narratives, and opens up the possibility that more such local studies can be undertaken of one such narrative that gives more attention to the actuality of local experience in its variety and the agency of local people.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author is most grateful to Helen Watt and Jenny Day for their collaboration on an earlier version of this article and for sterling work on the transcriptions involving Welsh names. He would like to thank this volume’s editors for inviting the present contribution; an anonymous reader for helpful suggestions in improving it, as well as those other scholars who have kindly answered his many questions or given helpful comments on this article in draft, among them Helen Fulton, Keith Ray and Philip Hume; and Hereford Cathedral, the Garway Heritage Group and the Mortimer History Society for listening to talks in which some of this material was presented. The author also thanks Hereford Cathedral Archives, The University of Oxford Bodleian Libraries and Herefordshire Archive and Research Centre for the kind assistance of their staff.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For a substantial recent re-appraisal of the archeology and context of Offa’s Dyke, see (Ray and Bapty 2016). The study of the March in its own right is gaining momentum in the Offa’s Dyke Journal (see also Capper 2023; Ray 2022). A current research project at Cardiff University, ‘Making the March: Contesting Lands in the Early Medieval Frontier’ (PI Dr Andy Seaman), is bringing together historians and archaeologists to offer a holistic view of the frontier through focused archaeological and historical analysis and to restore the March as a crucial part of the fabric of early medieval Britain. B. G. Charles chronicled the history and persistence of Welsh place-names in Archenfield and Oswestry even into the nineteenth century in his O’Donnell Lecture (Charles 1963), noting that, each in its turn, Offa’s Dyke, the Edwardian shiring, and the 1536 Act of Union should not be construed as constituting linguistic demarcation lines. On the survival of Welsh place-names see also now (Parsons 2022). |

| 2 | (Brady 2022); Franz Liebermann’s study of The Medieval March of Wales only goes up to 1283 but gives valuable commentary on the shifting meaning of the “March” itself (Lieberman 2010). |

| 3 | Stephenson (2016, p. 114 and pp. 133–58). Overlapping legal systems also made it possible for someone to claim to hold land by English tenure to escape native Welsh dues: see (Stacey 2018, p. 72). |

| 4 | On the survival of Welsh place-names see also now (Parsons 2022). |

| 5 | This foundation date and the identity of the founding bishop Putta are characteristically themselves ‘debateable lands’, to borrow a term from another borderland (Hillaby 1976; Sims-Williams 2004). |

| 6 | British bishops and clerics were signatories at the Council of Arles in 313, a thousand years before the subject matter of this article (Haddan and Stubbs 1869, I p. 7), and despite his later appropriation as the first Bishop of Llandaff and indeed Archbishop of Southern Britain, St Dyfrig/Dubricius perhaps really was active as a bishop in Ergyng (from which the diocese may have migrated to Llandaff) in the early sixth century (Thornton 2004). |

| 7 | Giraldus (2005, pp. 49–56). Gerald himself, of course, was ambitious both to see the Diocese of St David’s raised to archiepiscopal status and himself thus raised too; so while he is active locally in incidents such as these as Archdeacon of Brecon or later as a Canon of Hereford, he is also playing a part in a longer and deeper narrative. |

| 8 | Conveniently summarised at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1915–.1916_Church_of_England_border_polls (accessed on 10 February 2024). |

| 9 | See Stephenson 2019, p. 112 for examples of how “minute research” has brought to light ambivalence, assimilation, and indeed collusion in ethnic relations in what Stephenson labels “an age of contradictions”. |

| 10 | Stephenson (2021); see also the reviews by Sara Elin Roberts (Roberts 2022) and Georgia Henley (Henley 2024), both of whom, like Stephenson, have been active contributers to the work of the Mortimer History Society, which has grown recently into a signifcant resource for this area of study. |

| 11 | Brady (2018, p. 42). See also (Molyneaux 2011). The terms Dunsaete and Archenfield/Ergyng should not, however, be simplistically elided: see (Whitehead 1982, p. 13; Charles-Edwards 2012, p. 422). |

| 12 | Lambert (2022, p. 12). In his synoptic study of The Age of Conquest: Wales 1063–1415, R.R. Davies also reminds us of the fluidity of the border and that “countries and borders are not laid up in heaven”, referring specifically to the Archenfield area and examining the process of accommodation and assimilation, including the common use of aliases as time went on, which blurred identification as simply Welsh or English (Davies 2000, pp. 4, 6, 424). |

| 13 | The men of Archenfield are allowed to retain their local customs and privileges, holding their land freely direct from the Crown, but are for instance required to form the van of the Crown’s forces going into Wales, and the rear-guard on the retreat (Thorn et al. 1983, sct. A). |

| 14 | National Library of Wales MS 17110E fols. 75v–76r. |

| 15 | (Charles-Edwards 2012, pp. 251, 267, 285, 621). See further (Sims-Williams 2019) for a careful analysis of the Book of Llandaff acknowledging that its charters are rephrased into twelfth-century form and gathered together to assert the rights of the Diocese of Llandaff at that time, but also that they are likely to retain earlier information that is otherwise lost. |

| 16 | For the Templars and Hospitallers at Garway, see (Fleming-Yates 1995; Tapper 2005; Nicholson 2018). |

| 17 | For the church building, see (Brooks and Pevsner 2012, pp. 243–46) and the HER record at https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=107702&resourceID=19191 (accessed on 11 February 2024). For shared use, see (Hundley n.d.). Garway in particular is richly served for local history, as for instance by the 1308 accounts of John de la Haye at the point when the estates passed to the Hospitallers (TNA E358/18, rots 2, 44, 25, 47, 50; Nicholson 2016) and the 1338 report by Philip de Thame on the Hospitaller estates in England (Larking and Kemble 1857, pp. 196–97), much of which is discussed in (Fleming-Yates 1995). |

| 18 | (The National Archives Manorial Documents Register n.d.) gives the relevant information. |

| 19 | “Sir” in this context indicates a cleric without a Master’s degree, rather than a knight. |

| 20 | For a fuller description, see (Forrest and Whittick 2023, pp. xi–xii). |

| 21 | The italicisation is the editors’ and indicates subsequent annotation. |

| 22 | Item quod idem dominus est inhabilis ad gerendum curam animarum ibidem quia nescit linguam Wallicanam et quamplures parochiani ibidem nesciunt linguam Anglicanam. |

| 23 | Translation from (Forrest and Whittick 2023, p. 39). |

| 24 | Day (1927, p. 54). The tradition of complaint seems to have continued even after this. The churchwardens complained to the bishop c. 1690 that the then vicar Jeremiah Jackson did not wear his surplice on Sundays and set his neighbours against one another, and the vicar complained that the churchwardens brought their children up as Papists, invited their cronies into the church, got them drunk, and rang the church bells all day–as recalled by the local WI in 1989 (Herefordshire Federation of Women’s Instutes 1989, pp. 94–95). |

| 25 | New transcription by the author and Helen Watt. Personal names have been capitalised throughout. The mark similar to/between details of persons has been interpreted as a comma, but might be a full stop. [] mark editorial expansions and () doubtful readings. |

| 26 | See (Thomson 1979) for descriptions of MS Douce 103 (pp. 277–89) and other such manuscripts. The composite nature of Davyys’s manuscripts is typical of English late-medieval books containing school material. But they also sit well alongside late-medieval Welsh manuscripts which, albeit for different reasons, are also typically assemblages of both texts and of smaller manuscript units and may be linguistically mixed: see (Lloyd-Morgan 2015, pp. 175–77). |

| 27 | It is worth noting, in the light of John Davyys’ interest in the teaching of grammar, that Aconbury Priory seems to have had a reputation for providing education in the later Middle Ages, with Bishop Lee of Coventry, Lord President of the council in the March of Wales, writing to Thomas Cromwell in 1536 requesting that the nunnery of Aconbury be not dissolved, giving the reason that ‘the gentlemen of Abergavenny, Ewyas Lacy, Talgarth and Brecon and the adjoining parts of Wales sent their women and children to Aconbury to be brought up in virtue and learning’ (Hillaby and Hillaby 2018, pp. 84–85). |

| 28 | Bannister (1919b, pp. 178, 179, 181). Davyys is not, of course, John Davies of Hereford c1565–1618, the famous author of The Writing Schoolemaster. Susan Powell (Mirk and Powell 2009, p. I.545-6) considers the possibility that he was the John Davys of Merton College, Oxford, who became senior proctor of the University 1492–3, but notes that he is recorded (in 1499) as beneficed in Kent. He would also have been an MA, and the junior position in Herefordshire and senior one in Oxford seem unlikely bedfellows. It is also worth noting that having a title from a monastic house was very common in this period and need not imply any storng connection with it. |

| 29 | MS Douce 103 is fully described in (Thomson 1979, pp. 277–82), and the English grammatical treatise is edited in (Thomson 1984, pp. 56–60). See also (Thomson 1983b, pp. 584–90) for the liturgical material. |

| 30 | (Thomson 1979) gives full descriptions which show how many such manuscripts were built up from booklets or quires containing their main texts, which were then surrounded by additional material. |

| 31 | Transcription by the author: see (Thomson 1979, p. 282). Records at the Hereford Archives and Record Centre (N53/1227; N53/1317; N53/1372) show that the Hopkyn/s were landowners and lessees in the first half of the seventeenth century, and this may be the same family. |

| 32 | National Library of Wales, MS Peniarth 356B fols. 95r–v; see (Thomson 1979, pp. 114–31; Huws 2022) s.n. Peniarth 356B for a description of the manuscript and (Thomson 1982) for a transcription of the list. |

| 33 | Transcription by Helen Watt and the author with grateful thanks to Jenny Day for additional help. Capitalisation is editorial. Italics mark expansions of abbreviations and ’ an unexpanded abbreviation. Initial I/J is transcribed following modern usage and medial u as v in names where that would be expected. * marks words where we were uncertain of how to transcribe or expand. |

| 34 | Transcription from (Thomson 1984, p. 56). |

| 35 | Transcription by the author. |

| 36 | MS visitacitacionis. |

| 37 | MS translacione. |

| 38 | Transcription by the author. See (Thomson 1983b, p. 588). |

| 39 | Mirk and Kristensson (1974) is the most recent edition of the Instructions. Bryant et al. (1999) is a useful companion, also offering a translation. |

| 40 | MS Barre in error. |

| 41 | The text here may be corrupt. |

| 42 | Transcription by the author. |

| 43 | A considerable tide of academic exploration is now building up a much more nuanced picture of multilingualism and code-switching across a number of disciplines. To take just a few examples, Marjorie Harrington’s PhD thesis ‘Bilingual Form: paired translations of Latin and Vernacular Poetry, c.1250–1350’ (Harrington 2017) includes discussion of friar William of Herebert of Hereford’s ‘paired translations’ in his sermon notebook in the trilingual setting of the West Midlands; Ad Putter speaks of “The linguistic Repertoire of Medieval England” with attention to the March (Putter 2016, pp. 130–32); Siegfried Wenzel’s book on Macaronic Sermons (Wenzel 1994) explores in magisterial detail the different ways in which the two languages might be used together; while the present author has a research interest in grammar texts that weave together Latin and English (Thomson 1987; cf Cannon 2015). Paul Russell goes beyond descriptive approaches to make a detailed exploration of the way in which Latin and Welsh co-existed and mutually modified one another in the Middle Ages (Russell 2017), and considers how the use of different language options may be “functionally compartmentalised” (Russell 2019, pp. 17–18). Jennifer Ruggier, exploring issues of identity through the lens of the chronicler Adam Usk, takes more account of theoretical approaches to national identity, with an interesting opening discussion about the way in which different disciplinary and theoretical approaches can mitigate an “uncomplicated” understanding (Ruggier 2021, p. 22). |

| 44 | Thomson (1983a). Dr Rhun Emlyn is working on these Oxford connections: see (Emlyn 2018; Emlyn 2023). For a case study of how dictaminal teaching in Oxford may have percolated down to a junior clerk at Hereford Cathedral, see (Thomson and Camargo 2022). |

| 45 | See (Lockie 2021) for a convenient list of institutions, Sun (2015) for a general treatment of Hereford clergy in the late Middle Ages, and (Swanson 1985, pp. 57–58) on graduates, non-graduates, and benefices. |

| 46 | See (Thomson 1979, pp. 114–31) for a full description of the manuscript. |

| 47 | (L. B. Smith 1987; Jacques 2020; Jacques 2024). L. B. Smith (1998) considers the impact of literacy in late medieval Wales, offering a rich palette of detail. The evidence linking manuscripts with owners, like the survival of manuscripts themselves, is patchy, but she is able to present a small group of clerics who bequeathed books and poets who wrote them, along with a few lay owners (pp. 204–10), with John Edwards of Chirk among them. |

References

- Bannister, Arthur Thomas. 1919a. The Register of Richard Mayhew, Bishop of Hereford (1504–1516). Hereford: Wilson and Phillips, Printers. [Google Scholar]

- Bannister, Arthur Thomas. 1919b. The Register of Thomas Myllyng, Bishop of Hereford (1474–1492). Registrum Thome Myllyng, Episcopi Herefordensis, A.D. 1474–1492. Hereford: Cantilupe Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bannister, Arthur Thomas. 1921. Diocesis Herefordensis: Registrum Caroli Bothe, Registrum Edwardi Foxe, Registrum Edmundi Boner. Canterbury and York Series. London: The Canterbury and York Society, vol. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, Walter de Gray. 1912. Memorials of the See and Cathedral of Llandaff: Derived from the Liber Landavensis, Original Documents in the British Museum, H.M. Record Office, the Margam Muniments, etc. Memorials of Llandaff Cathedral. Neath: J. E. Richards. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, Lindy. 2018. Writing the Welsh Borderlands in Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, Lindy. 2022. The Fluidity of Borderlands. Offa’s Dyke Journal 4: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, Lindy. 2023. Multilingualism in Early Medieval Britain, 1st ed. Cambridge Elements. Elements in England in the early Medieval World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Alan, and Nikolaus Pevsner. 2012. Herefordshire. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, Geoffrey F., Vivien M. Hunter, and Gordon A. Plumb. 1999. ‘How Thow Schalt thy Paresche Preche’: John Myrc’s Instructions for Parish Priests. Barton-on-Humber: Workers’ Educational Association, Barton-on-Humber Branch. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, Christopher. 2015. Competing Archives, Competing Histories: French and Its Cultural Locations in Late-Medieval England: 2. Vernacular Latin. Speculum 90: 641–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, Morn. 2023. Treaties, Frontiers and Borderlands: The Making and Unmaking of Mercian Border Traditions. Offa’s Dyke Journal 5: 208–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, Bertie George. 1963. The Welsh, their language and place-names in Archenfield and Oswestry. In Angles and Britons: O’Donnell Lectures. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas Mowbray. 2012. Wales and the Britons, 350-1064, 1st ed. History of Wales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coplestone-Crow, Bruce. 2009. Herefordshire Place-Names, 2nd ed. Almeley: Logaston. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Robert Rees. 1978. Lordship and Society in the March of Wales, 1282–1400. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Robert Rees. 2000. The Age of Conquest: Wales 1063–1415. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Day, E. Hermitage. 1927. The Preceptory of the Knights Hospitallers at Dinmore, Co. Hereford. Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club 1927–1929 pub 1931: 45–76. [Google Scholar]

- Emlyn, Rhun. 2018. Migration and Integration: Welsh Secular Clergy in England in the Fifteenth Century. In The Welsh and the Medieval World: Travel, Migration and Exile. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, pp. 75–130. [Google Scholar]

- Emlyn, Rhun. 2023. Wales, the March and the Universities (Lecture to the Mortimer History Society). Available online: https://youtu.be/TtnP9BhMS14 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Fleming-Yates, Joan. 1995. The Knights Templars and Hospitallers in The Manor of Garway, Herefordshire 1086–1540. Ross-on-Wye: Ross-on-Wye and District Civic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, Ian, and Christopher Whittick. 2016. The Thirteenth-century Visitation Records of the Diocese of Hereford. The English Historical Review 131: 737–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, Ian, and Christopher Whittick. 2023. The Visitation of Hereford Diocese in 1397 = Canterbury and York Society Vol. 111. York: The Canterbury & York Society. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, Helen. 2011a. Literature of the Welsh gentry: Uses of the vernacular in medieval Wales. Vernacularity in England and Wales, c. 1300 1550: 199–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, Helen. 2011b. Negotiating Welshness: Multilingualism in Wales before and after 1066. In Conceptualizing Multilingualism in England c. 800-c. 1250:Vol. 27. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 145–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, Helen. 2013. The Status of the Welsh Language in Medieval Wales. In The Land Beneath the Sea: Essays in Honour of Anders Ahlqvist’s Contribution to Celtic Studies in Australia. Edited by Pamela O’Neill. Sydney: University of Sydney Celtic Studies Foundation, pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, Helen. 2024. Mapping the March: Medieval Wales and England, c. 1282–1550. Available online: https://blog.mowlit.ac.uk (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Giraldus. 2005. The Autobiography of Gerald of Wales. Translated by Harold Edgeworth Butler. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Gneuss, Helmut. 1968. Hymnar und Hymnen im englischen Mittelalter: Studien zur Überlieferung, Glossierung und Übersetzung lateinischer Hymnen in England.Buchreihe der Anglia; Bd. 12. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, Ben. 2018. The Life of St Dyfrig and the Lost Charters of Moccas (Mochros), Herefordshire. Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 75: 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Haddan, Arthur West, and William Stubbs. 1869. Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents Relating to Great Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Clarendon Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, Marjorie. 2017. Bilingual Form: Paired Translations of Latin and Vernacular Poetry, c. 1250–1350. Ph.D. thesis, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, Georgia. 2024. Review of (Stephenson 2021): Patronage and Power in the Medieval Welsh March: One Family’s Story. Speculum 99: 962–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herefordshire Federation of Women’s Instutes. 1989. The Herefordshire Village Book. Villages of Britain Series; Newbury: Countryside Books and the HFWI. [Google Scholar]

- Hillaby, Joseph. 1976. The Origins of the Diocese of Hereford. Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club XLII: 16–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hillaby, Joseph, and Caroline Hillaby. 2018. Aconbury Church: A national monument? Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club 66: 61–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hume, Philip. 2021. The Welsh Marcher Lordships 1: Central and North. Eardisley: Logaston Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hundley, Catherine E. n.d. Shared Space: Templars, Hospitallers, and the English Parish Church. In Towards an Art History of the Parish Church, 1200–1399. Edited by Meg Bernstein. London: The Courtauld. Available online: https://courtauld.ac.uk/research/research-resources/publications/courtauld-books-online/parish-church/ (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Huws, Daniel. 2022. A Repertory of Welsh Manuscripts and Scribes c.800–c.1800. Aberystwyth: The National Library of Wales and University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, Michaela. 2020. The Reception and Transmission of the Bardic Grammars in Late Medieval and Early Modern Wales. Ph.D. thesis, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Available online: https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365759 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Jacques, Michaela. 2024. Grammar and Poetry in Late Medieval and Early Modern Wales: The Transmission and Reception of the Welsh Bardic Grammars. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Luke William. 2022. Ergyng to Archenfield: National Identity in an Early Medieval Borderland. Kalamazoo: International Congress on Medieval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Larking, Lambert B., and John M. Kemble. 1857. The Knights Hospitallers in England: Being the Report of Prior Philip de Thame to the Grand Master Elyan de Villanova for A.D. 1338. Works of the Camden Society; No. 65. London: Printed for the Camden Society. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, Beatrice A. 1935. Records of the Templars in England in the Twelfth Century: The Inquest of 1185 with Illustrative Charters and Documents. Records of the Social and Economic History of England and Wales; v. 9. London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, for the British Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, Max. 2010. The Medieval March of Wales: The Creation and Perception of a Frontier, 1066–1283, 1st ed. Vol. v. Series Number 78. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought. Fourth Series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Llanwarne Parish Council Website. n.d. Available online: https://llanwarnegroupparishcouncil.co.uk/llanwarne-parish/parish-history/ (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Lloyd-Morgan, Ceridewen. 2015. Writing without Borders: Multilingual Content in Welsh Miscellanies from Wales, the Marches, and Beyond. In Insular Books: Vernacular Manuscript Miscellanies in Late Medieval Britain. Edited by Margaret Connolly and Raluca Radulescu. London: Oxford University Press for the British Academy, pp. 175–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lockie, Mel. 2021. Table of Institutions in the Diocese of Hereford. Available online: https://www.melocki.org.uk/diocese/Institutions.html (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Marshall, George. 1927. The Church of the Knights Templars at Garway, Herefordshire. Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club 1927–1929 pub 1931: 86–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mirk, John. 1868. Instructions for Parish Priests. Early English Text Society. O.S. 31. London: Trübner & Co. for the Early English Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- Mirk, John, and Gillis Kristensson. 1974. John Mirk’s Instructions for Parish Priests. Lund Studies in English. 49. Lund: CWK Gleerup. [Google Scholar]

- Mirk, John, and Susan Powell. 2009. John Mirk’s Festial. Early English Text Society; O.S. 334, 335. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux, George. 2011. The Ordinance concerning the Dunsæte and the Anglo-Welsh Frontier in the Late tTenth and Eleventh Centuries. Anglo-Saxon England 40: 249–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heritage List for England. n.d. The National Heritage List for England: St Dennis Church Pencoyd. Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1348774 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Nicholson, Helen J. 2016. The Templars’ Estates in the west of Britain in the Early Fourteenth Century. In The Military Orders, Vol. 6.2: Culture and Conflict in Western Europe. Edited by Jochen Schenk and Mike Carr. London: Routledge, pp. 132–42. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, Helen J. 2018. Evidence of the Templars’ Religious Practice from the Records of the Templars’ Estates in Britain and Ireland in 1308. London: Routledge, pp. 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, Helen J. n.d. The Custodians’ Accounts from the Knights Templars’ Estates in Herefordshire from TNA E358/19. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/5747145/The_custodians_accounts_from_the_Knights_Templars_estates_in_Herefordshire_from_TNA_E358_19 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- O’Malley, Gregory. 2005. The Knights Hospitaller of the English Langue 1460–1565. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, David N. 2022. Welsh and English in Medieval Oswestry: The Evidence of Place-Names. Nottingham: English Place-Name Society. [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Smith, Anna. 2024. Open Domesday. Available online: https://opendomesday.org/place/SO4522/garway/ (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Pulsiano, Phillip. 1996. Descriptions. In Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts in Microfiche Facsimile, Vol. 4: Glossed Texts, Aldelmania, Psalms. Binghamton: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Putter, Ad. 2016. The Linguistic Repertoire of Medieval England, 1100–1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 126–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Keith. 2022. The Organisation of the Mid–Late Anglo-Saxon Borderland with Wales. Offa’s Dyke Journal 4: 132–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, Keith, and Ian Bapty. 2016. Offa’s Dyke: Landscape and Hegemony in Eighth-Century Britain. Oxford: Windgather Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, William Jenkins, and Llyfr Teilo. 1840. The Liber Landavensis, Llyfr Teilo, or the Ancient Register of the Cathedral Church of Llandaff. tr. and notes by W. J. Rees. Llandovery: Society for the Publication of Ancient Welsh MSS. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Melville. 1970. The population of the Welsh Border. Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion 1: 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Michael. 1979. Sprache und Gesellschaft im Mittelalter: Untersuchungen zur mündlichen Kommunikation in England von der Mitte des elften bis zum Beginn des vierzehnten Jahrhunderts.Monographien zur Geschichte des Mittelalters; Bd. 18. Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Sara Elin. 2022. (Review of) Patronage and Power in the Medieval Welsh March: One Family’s Story, by David Stephenson. The English Historical Review 137: 1509–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggier, Jennifer. 2021. Welsh Identity and Adam Usk’s Chronicle (1377–1421). Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Paul. 2017. ‘Go and Look in the Latin Books’: Latin and the Vernacular in Medieval Wales. In Latin in Medieval Britain. Edited by Richard Ashdowne and Carolinne White. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the British Academy, pp. 213–46. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Paul. 2019. Bilingualisms and Multilingualisms in Medieval Wales: Evidence and Inference. Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmorodorion 25: 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Williams, Patrick. 2004. Putta. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Available online: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-22912 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Sims-Williams, Patrick. 2019. The Book of Llandaf as a Historical Source. Studies in Celtic History 38. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]