Abstract

Research relating personality variables to gratitude to God (GTG) is in its nascent stages, as only a few descriptive, correlational studies have been conducted on this topic. We investigated whether two kinds of personality variables—positive emotional traits and adaptive relational styles—predicted higher GTG. Hypotheses linking these variables to GTG were based on a novel, preregistered conceptual framework. We also explored whether general gratitude statistically mediated these links. In a cross-sectional study of N = 698 undergraduates from the United States, participants completed self-report measures of personality predictors, situational GTG and situational general gratitude in response to a positive event, as well as trait GTG. Correlations showed strong support for hypotheses connecting GTG (situational and trait) with positive emotional traits (extraversion, optimism, vitality, self-esteem). Correlations also supported hypotheses for one adaptive relational style (agreeableness) but not others (honesty–humility, lack of entitlement, secure attachment). General gratitude was a mediator of associations between positive emotional traits and both trait and situational GTG, and general gratitude mediated associations between adaptive relational styles and trait GTG. These results provide initial evidence suggesting that positive emotional traits have consistent, direct (and indirect via gratitude) links to GTG, whereas the evidence for adaptive relational styles was more inconsistent and indirectly mediated via general gratitude.

Keywords:

God; gratitude; extraversion; optimism; vitality; self-esteem; agreeableness; honesty–humility; entitlement; secure attachment 1. Introduction

Gratitude to God (GTG), which may be defined as feelings of thankfulness and appreciation directed toward God in response to receiving benefits (Rosmarin et al. 2011; Krause et al. 2014), has been the focus of a growing amount of research (as evidenced by this special issue). Much of the pioneering work on this topic indicated that higher levels of GTG associated with various indicators of better psychological health (e.g., Krause et al. 2014; Aghababaei and Tabik 2013; Sadoughi and Hesampour 2020). Such studies have established the potential importance of GTG and motivated attempts to understand the factors that predict GTG. Initial work focused on identifying predictors focused on religious/spiritual (r/s) (e.g., Krause and Hayward 2015), affective (e.g., Wilt and Exline 2022), cognitive (e.g., Exline and Wilt 2022a, 2022b), and personality variables (e.g., Aghababaei et al. 2018). We aim to contribute to the literature on predictors by taking a relatively comprehensive look at potential personality and individual-difference variables that may be relevant to GTG. In this paper, we not only examine a wide variety of potential predictors, but also offer theoretical frameworks for why certain kinds of personality variables may predict GTG, highlighting the potential roles of positive emotional traits and adaptive relational styles. Furthermore, as personality variables have also been linked to general gratitude (McCullough et al. 2002; Wood et al. 2009), we explored whether general gratitude mediated the associations between our predictors and GTG. Finally, we examined these questions regarding two kinds of GTG: (a) trait or average levels of GTG and (b) event-specific GTG in response to a positive event. Thus, this study has the potential to increase understanding about the relationships between personality, GTG, and gratitude, and it also builds on the body of knowledge regarding how personality interfaces with religion and spirituality (Wilt et al. 2020).

1.1. Gratitude to God: Outcomes and Predictors

Given the robust body of work showing that general gratitude is highly adaptive (for reviews, see Emmons et al. 2019; Wood et al. 2010), most early work on GTG examined the possibility that GTG could be an important predictor of positive psychological outcomes. This work has been fruitful, as higher trait GTG associated with higher levels of multiple indicators of well-being: overall well-being (Aghababaei et al. 2018; Rosmarin et al. 2011; Sadoughi and Hesampour 2020), happiness (Aghababaei et al. 2018), hope (Krause et al. 2015), and life-satisfaction (Aghababaei et al. 2018; Aghababaei and Tabik 2013). GTG also related to lower levels of depression (Aghababaei and Tabik 2013; Krause et al. 2014), as well as better adjustment to stress (Krause 2006) and bereavement (Upenieks and Ford-Robertson 2022). Further, a recent study found that trait GTG predicted increased r/s well-being over time (Watkins et al. 2022). Only one study to our knowledge looked at event-specific GTG and found that GTG in response to both positive and negative events related to higher levels of perceived closeness to God (Wilt and Exline 2022). Concepts akin to GTG also relate to salutary outcomes. Prayers of thanksgiving are associated with higher life-satisfaction, self-esteem, optimism (Whittington and Scher 2010), psychological well-being (Zarzycka and Krok 2021), and marriage satisfaction (Fincham and May 2021). Similarly, transcendent indebtedness to God is linked to higher levels of awe, humility, empathy, and prosocial behavior (Nelson et al. 2022).

Most work on predictors of trait GTG has looked at r/s and personality variables. In the domain of r/s in general, predictors of higher trait GTG include religiosity (Rosmarin et al. 2011), belief in God (Aghababaei et al. 2018; Krause and Hayward 2015; Nelson et al. 2022; Rosmarin et al. 2011), positive views of God (Park et al. 2022), secure attachment to God (Nelson et al. 2022), and emotional and spiritual connection to r/s communities (Krause and Ellison 2009; Krause et al. 2014, 2015). Overall, this work suggests that GTG may be an outcome of healthy religion and spirituality. Personality predictors of higher trait GTG include higher extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and honesty–humility (Aghababaei and Tabik 2013; Aghababaei et al. 2018).

Predictors of event-specific GTG include r/s as well as psychological (e.g., cognitive, motivational, affective) variables. People who reported relationships with God characterized by high degrees of love/safety and excitement/energy had higher levels of GTG in response to a positive event (Exline and Wilt 2022c). Cognitive and motivational variables related to receiving benefits also predicted higher GTG in response to positive events (Exline and Wilt 2022a, 2022b): These variables included (a) believing that God can cause positive events, (b) attributing a specific positive event to God, (c) seeing positive events as gifts from God, and (d) wanting to receive a gift from God. Finally, positive affect in response to positive and negative events related to higher levels of event-specific GTG (Wilt and Exline 2022).

1.2. A Theoretical Framework for Potential Personality Predictors of GTG: Positive Emotional Traits and Adaptive Relational Styles

Research on personality and GTG is just beginning. Thus far, it has documented associations between traits—higher extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and honesty–humility—and trait GTG (Aghababaei and Tabik 2013; Aghababaei et al. 2018). In the current study, we aimed to expand on this work by focusing on two kinds of personality variables that we see as being linked theoretically with GTG (a) positive affective traits and (b) adaptive relational styles.

We use the umbrella term, “positive affective traits”, to encompass traits that reflect individual differences in the experience of positive affect; that is, people with higher levels of such traits experience more positive affect, whereas people with lower levels experience less positive affect. We hypothesized that people with higher levels of positive affective traits would experience more GTG based on the following rationale. First, as positive emotion is tied to reward, people with higher levels of positive emotion should be more likely to recognize benefits in their lives. Thus, such individuals simply will have more benefits that could be attributed to God. Second, as positive emotions signify a lively and energetic experience of life, it is possible that such traits relate to a more dynamic relationship with God, one characterized by spontaneity and excitement: note that these types of relationships with God are associated with higher GTG (Exline and Wilt 2022c). Thus, people with higher levels of positive emotional traits may view God as being highly involved in generating a fun experience of life. When such individuals people experience a benefit and consider whether God may be responsible, their view of God would match with beliefs about how God operates. We assessed several examples of positive affective traits in the current study. Extraversion is a broad personality trait reflecting individual differences in positive emotions as well as assertive behaviors and the desire for social attention (Wilt and Revelle 2016). Optimism is a disposition reflecting the positive emotions of hope and confidence (Michael F. Scheier and Carver 1987). Vitality is defined as being energetic, strong, and lively (Ryan and Frederick 1997). Finally, self-esteem reflects one’s overall evaluation (positive to negative) of oneself and contains a strong, positive emotional component (Watson et al. 2002).

We refer to the term, “adaptive relational styles”, to signify traits that reflect individual differences in tendencies to relate to other people with warmth, comfort, and security. First, given their positive relationships with others, we reasoned that people with higher levels of adaptive relational styles would be more open to considering other agents, including God, as benefactors. Second, because such individuals—if they believe in God—may view God as a warm and caring provider, they may see benefits as provisions from God. Indeed, perceived relationships with God characterized by love and safety are associated with higher GTG (Exline and Wilt 2022c), Third, such individuals should be more be willing and motivated to credit God, perhaps to maintain and strengthen relational bonds. We assessed several traits reflecting adaptive relational styles. Agreeableness is a broad trait encompassing individual differences in tendencies for prosocial behavior, trust in others, kindness and empathetic ways of relating to others (Graziano and Tobin 2009). Honesty–humility is a broad trait concerned with the well-being of others and not overestimating one’s own abilities (Van Tongeren et al. 2019). Psychological entitlement, in contrast to humility, reflects tendencies to be self-focused and put one’s own needs ahead of the needs of others (Campbell et al. 2004); note that we conceptualize low levels of psychological entitlement as reflecting an adaptive relational style. Finally, we assessed attachment security, a working model of relationships characterized by the expectation that the other person in the relationship will support one’s needs in a warm and caring fashion (Brennan et al. 1998).

1.3. Exploring General Gratitude as a Mediator

The link between GTG and personality could be applied to other entities (e.g., another person, a group of individuals, another supernatural agent, etc.). Because of the potential for the framework to generalize across many entities, we see these steps as a framework for understanding general gratitude, which of course encompasses all types of gratitude: e.g., GTG, interpersonal gratitude, cosmic gratitude, etc. As such, we think it is possible that the personality predictors we identified could be related not only to GTG but to many kinds of gratitude. Note that this is consistent with findings indicating that a subset of our predictors—extraversion, agreeableness, honesty–humility—are linked with general gratitude (Aghababaei et al. 2018; McCullough et al. 2002). This line of reasoning led us to explore whether general gratitude statistically mediated the associations between our personality predictors and GTG. If we find evidence in support of mediation, this would be consistent with the idea that the personality predictors are linked with gratitude to various entities through common processes, with God being one important kind of entity. If we find that associations between personality predictors and GTG remain when accounting for general gratitude, this might suggest that at least part of the link between personality variables and GTG is due to processes that are unique rather than generalizing across other entities.

1.4. Summary and Overview of Present Study

Our study examines two potential kinds of personality predictors of GTG: positive emotional traits and adaptive relational styles. We tested whether several variables in each of these categories related to GTG. Further, our framework may generalize beyond GTG to many other entities and thus could explain associations between personality variables and general gratitude. We explored this possibility by testing whether general gratitude mediated the associations between personality predictors and GTG. We tested all of these ideas for two kinds of GTG: trait GTG (i.e., overall or average levels) and event-specific GTG in response to a positive event. In the current study, a large sample of undergraduates filled out online self-report survey measures of key variables and reported reactions to a recent positive event. (Analysis scripts and deidentified data are available at https://osf.io/ztc9j/?view_only=b370c7916af144bc81f483e6ee0e0708).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

All methods were approved by the (anonymized) IRB. We recruited undergraduates from a private research university in the (anonymized) region of the United States (U.S.) via the introductory psychology participant pool. Participants were given informed consent and completed an online survey titled “Positive and Negative Events” for partial fulfillment of their research participation requirement. The survey included all measures relevant to the current study and additional measures that were a part of a larger project on GTG (see: https://osf.io/ztc9j/?view_only=b370c7916af144bc81f483e6ee0e0708).

A total of 717 students completed the survey. We excluded 19 students for failing an attention check, and therefore we retained N = 698 participants (390 women, 298 men, 6 “prefer not to say”, 3 “other”, and 1 transgender man) for analyses. Ages ranged from 18 to 34 (M = 19.17, SD = 1.66). Ethnicities included Asian/Pacific Islander (47%), White/Caucasian (42%), Latino/Hispanic (11%), African American/Black (7%), Middle Eastern (4%), Native American/American Indian/Alaskan Native (1%), “other” (1%) and “prefer not to say” (1%). (Some participants selected multiple ethnicities.). R/s affiliations included Christian (36%: unspecified or other (13%), Catholic (15%), Protestant (7%), Eastern Orthodox (1%)), Hindu (10%), Muslim (3%), Jewish (3%), “spiritual” (1%), and “other” (2%). Non-r/s affiliations included no affiliation (18%), agnostic (12%), atheist (13%), and unsure (<1%).

2.2. Measures

Participants completed two types of GTG and general gratitude measures: trait measures and those focused on a specific positive event. Participants also completed standardized measures of positive emotional traits and adaptive relational styles. For all measures, scores were calculated by averaging across items.

2.2.1. Gratitude to God and General Gratitude Response to a Positive Event

One section of the survey asked participants to recall an especially positive event from the past month. Instructions read, “Please take a few moments to recall something positive that happened to you in the past month. Try to recall one of the most positive things that you experienced”. Participants were asked to write a brief description of the event.

To assess GTG in response to this event, participants read, “When you think about this event, do you feel grateful to _______?” followed by a list of randomized items rated from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). One item read “God (or a god or Higher Power)”. To assess general gratitude, participants read, “Overall, how much gratitude do you feel as you think about this event?” and rated responses on a slider anchored at 0 (no gratitude) 50 (moderate gratitude), and 100 (extreme gratitude).

2.2.2. Trait Gratitude to God and General Gratitude

To assess trait GTG, we used we used the six-item measure used by Rosmarin et al. (2011). Items (e.g., “I have so much in life to be thankful to God for”) were adapted from the McCullough et al. (2002)’s dispositional gratitude measure and rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). To assess, trait general gratitude, we used McCullough et al. (2002)’s measure, with items (e.g., “I have so much in life to be thankful for”) rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

2.2.3. Positive Emotional Traits

Participants completed the 12-item extraversion subscale of the BFI-2 (Soto and John 2017). Agreement with items (e.g., “is outgoing, sociable”) was rated from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). We assessed optimism with the six-item Life Orientation Test (Michael F Scheier et al. 1994). Agreement with items (e.g., “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best”) was rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We assessed vitality with the six-item Subjective Vitality Scale (Ryan and Frederick 1997), with items (e.g., “I feel alive and vital”) rated to the “degree to which the statement is true for you” from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). We assessed self-esteem with the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg 1965). Agreement with items (e.g., “I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others”) was rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

2.2.4. Adaptive Relational Styles

We assessed agreeableness with the 12-item scale from the BFI-2 (Soto and John 2017). Agreement with items (e.g., “is compassionate, has a soft heart”) was rated from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). We assessed honesty–humility with the 10-item Honesty–Humility scale from the HEXACO-PI (Lee and Ashton 2004). Agreement with items (e.g., “I wouldn’t use flattery to get a raise of promotion at work, even if I thought it would succeed”) was rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We assessed psychological entitlement with the nine-item measure developed by Campbell et al. (2004). Agreement with items (e.g., “I honestly feel I’m just more deserving than others”) was rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We assessed individual differences in secure attachment using the one-item measure developed by Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991). Agreement with the item, “It is easy for me to become emotionally close to others. I am comfortable depending on others and having others depend on me. I don’t worry about being alone or having others not accept me,” was rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

3. Results

We conducted all analyses in R (R Core Team 2021). We used base functions in R and the psych package (Revelle 2022) to compute descriptive statistics and Pearson zero-order correlations, and we used the mediate() function in the psych package to conduct mediation models.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for all measures. In response to a positive event, participants reported modest amounts of GTG and high amounts of general gratitude. Participants reported high levels of trait GTG and general gratitude. Predictor variables were typically endorsed around scale midpoints. All multi-item measures had acceptable-to-high levels of internal consistency.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

3.2. Correlations

Table 2 shows Pearson zero-order correlations between predictors and gratitude variables. We computed correlations for the entire sample (N = 698) and for those endorsing r/s affiliations (n = 392) because we wanted to see whether including people who did not endorse r/s affiliations impacted the results. Results were highly similar for the entire sample and the subsample of r/s affiliated participants. Positive associations between positive emotional traits and both forms of GTG supported our hypotheses. Notably, all effect sizes for these variables were small-to-moderate according to recent guidelines for interpreting effect sizes (Gignac and Szodorai 2016). We found mixed support for our hypotheses regarding adaptive relational styles. The small, positive associations for agreeableness supported our hypotheses. Further the negative association between psychological entitlement and trait GTG was consistent with our hypotheses. However, in contrast to hypotheses, psychological entitlement was not related to GTG in response to a positive event, and neither honesty–humility nor secure attachment associated with either kind of GTG. We found some small-to-moderate associations between predictors and general gratitude response to a positive event, and we found mostly moderate-to-large associations between traits and trait general gratitude.

Table 2.

Pearson Zero-Order Correlations between Predictors and Gratitude Variables.

3.3. Mediation

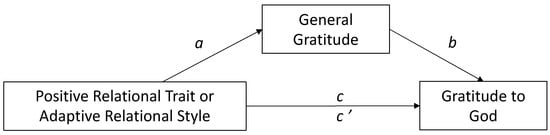

We tested the mediation model depicted graphically by Figure 1. Each trait was entered individually as the predictor variable. In the positive event model, gratitude in response to the positive event was the mediator, and GTG in response to the positive event was the outcome. In the trait model, trait gratitude was the mediator, and trait GTG in was the outcome. We used bias-corrected standard errors (from 2000 bootstrap samples) to compute 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effect (i.e., mediated effect) of predictors on GTG via general gratitude (MacKinnon et al. 2004; Preacher and Hayes 2004). Results of the models are displayed in Table 3. All estimates are unstandardized regression coefficients.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Mediation Model. Note. “a” and “b” are direct effects. “c” is the total effect of a predictor on gratitude to God, and “c’” is the effect of the predictor on gratitude to God after accounting for general gratitude. In the positive event model, gratitude in response to the positive event was the mediator, and GTG in response to the positive event was the outcome. In the trait model, trait gratitude was the mediator, and trait GTG in was the outcome.

Table 3.

Results from Mediation Models in Which Positive Emotional Traits and Adaptive Relational Styles Predicted GTG Variables Via General Gratitude.

Our mediation hypotheses were largely supported for positive emotional traits, as evidenced by positive indirect effects that did not include zero in the 95% CI (except for self-esteem in the positive event model). Further, there were significant direct effects from positive emotional traits to general gratitude, and in turn general gratitude had positive direct effects on GTG. In the event-specific model, predictors maintained significant associations with GTG when accounting for general gratitude (c’ path), but they did not in the trait GTG model. This indicates that general gratitude was a stronger mediator in the trait model than in the positive event model.

Among adaptive relational styles, mediation was supported for agreeableness. The results for this trait showed a pattern of results similar to that of the positive emotional traits described above. For other adaptive relational styles, mediation was not supported in the positive event models but was supported in the trait models. This divergent pattern of results is accounted for by the null or very small associations between these predictors and event-specific gratitude (see left side of table) in contrast to the significant associations between these predictors and general gratitude in the trait model (see right side of table). Therefore, although zero-order correlations between adaptive relational styles and trait GTG were mixed, people with higher levels of adaptive relational styles may experience higher levels of TGTG indirectly via higher levels of general gratitude.

4. Discussion

This project examined two kinds of personality variables, positive emotional traits and adaptive relational styles, as potential predictors of GTG. Consistent with hypotheses, various positive emotional traits (extraversion, optimism, vitality, self-esteem) related positively to GTG in response to a positive event and to trait GTG. Among adaptive relational styles, findings for agreeableness supported hypotheses; however, findings for other styles (psychological entitlement, honesty–humility, secure attachment) were sparse in correlational analyses. Notably, correlational findings were highly similar when excluding participants who did not endorse r/s affiliations. Because this study focused on normal personality, we wanted to include the entire sample in hypothesis tests. However, because GTG is likely less important for people who do not endorse r/s affiliations, we wanted to check whether excluding these participants would have substantially affected the results. Because it did not, we were more confident about interpreting correlational results and conducting mediation models with the entire sample.

We also explored whether general gratitude mediated associations between predictors and GTG. For positive emotional traits and agreeableness, findings supported the idea that gratitude as a statistical mediator of relationships, both for GTG in response to a positive event and especially for trait GTG. For other adaptive relational styles (psychological entitlement, honesty–humility, secure attachment), gratitude was not a mediator for GTG in response to a positive event but did mediate associations with trait GTG. This set of findings builds specifically on nascent work aimed at understanding how personality may relate to GTG and contributes to a wider body of knowledge on predictors of GTG.

4.1. Positive Emotional Traits Related Consistently to Higher GTG

Our rationale regarding positive emotional traits centered on the ideas that such traits would relate to recognizing more benefits in life (i.e., having more to be grateful for) and viewing God as being highly involved in generating a fun, lively, and rewarding life. Our results were consistent with these ideas, and thus future research may directly test these explanations. For example, a study could assess (a) the number and intensity of benefits and (b) lively interactions with God to determine whether these variables accounted for associations between positive emotional traits and GTG. Furthermore, our findings for extraversion replicated prior work on this trait (Aghababaei et al. 2018; Aghababaei and Tabik 2013) and thus introduces potential theoretical explanations (recognizing more benefits, having a lively relationship with God) for these earlier findings.

We tested general gratitude as a mediator based on the idea that our conceptual framework relating traits to GTG could apply to many forms of benefactors. For positive emotional traits, we found support for gratitude as a mediator, both at the positive event level and especially at the trait level. Regarding the positive event findings, the presence of mediation supported the idea that positive emotional traits were linked with GTG in part due to processes common to their link to gratitude (e.g., perhaps through noticing more rewards or having a positive, harmonious, or pleasant relationship with various benefactors). Because unique relationships remained between positive emotional traits and GTG in response to a positive event, there also may be something unique (i.e., distinct from general gratitude) about this relationship. These findings add to a growing body of work distinguishing GTG from general gratitude (Aghababaei and Tabik 2013; Park et al. 2022; Rosmarin et al. 2011; Wilt and Exline 2022). At the trait level, findings supported the idea that positive emotional traits were linked with GTG in part due to processes in common with their links to gratitude. This is consistent with prior work showing that sometimes associations with GTG do not remain when controlling for general gratitude (Aghababaei et al. 2018). It seems that a promising avenue for future work would be to further explore where experiences of GTG and general gratitude converge and diverge.

4.2. Adaptive Relational Styles Had Somewhat Inconsistent Associations with GTG

Our rationale regarding adaptive relational styles as predictors of higher GTG was that these styles would relate to (a) being more open to considering God as a benefactor, (b) viewing God as a caring provider, and (c) being willing to credit God as a benefactor. Although one style, agreeableness, consistently correlated with higher GTG (as observed in previous work: see Aghababaei et al. 2018; Aghababaei and Tabik 2013), other adaptive styles (honesty–humility, lack of entitlement, secure attachment) did not. While these findings alone provide mixed support for the plausibility of our theoretical rationale, we believe that considering them in conjunction with the results for general gratitude may be helpful.

Adaptive relational styles had null (honesty–humility, lack of entitlement) or small (agreeableness, secure attachment) associations with gratitude in response to a positive event, and all styles had positive associations with trait gratitude. In all, these findings may be viewed as being mostly consistent with the idea that our theoretical rationale for these styles generalizes across various benefactors. That is, adaptive relational styles may predict general gratitude because they relate to (a) being more open to considering other entities broadly defined (i.e., others) as benefactors, (b) viewing others as caring providers, and (c) are willing to credit others. As prediction is generally higher when aggregating across events or situations (Epstein 1979), it is not surprising that we found higher associations for trait gratitude than event-specific gratitude. Furthermore, we found evidence for mediation of associations between styles and GTG by general gratitude at the trait level (but not at the event level). Note that this may be due to the measures of trait GTG and trait general gratitude being framed in similar ways; this may have inflated associations due to shared method variance. However, if the trait levels findings are not fully explained by method variance, they are consistent with the idea that the styles are linked with trait GTG due to processes in common with their links to trait general gratitude. That is, people with higher levels of adaptive relational styles experienced more trait gratitude, and these higher levels of gratitude predicted higher GTG. This finding constitutes another example of convergence (rather than divergence) between GTG and general gratitude (e.g., Aghababaei et al. 2018). The question of why most relational styles were not linked with GTG specifically awaits further research.

4.3. Limitations

Our cross-sectional, correlational design prohibits us from making causal conclusions about the relationships between personality and gratitude variables. Though our theoretical framework specified that causality flowed from personality to GTG and gratitude, we cannot rule out bidirectionality or reverse directionality. Similarly, we cannot make strong claims about the directionality of mediation models. Rather, we interpret the observed associations as suggesting that the causal direction we proposed remains plausible. This was a necessary initial step for testing our framework. However, future longitudinal and experimental studies are better suited to test causality and directionality more directly.

Some limitations pertain to measurement. Measurement of GTG, and especially event-specific GTG, is still in its nascent stages. Our one-item measures of event-specific GTG and general gratitude, which were chosen for their high face validity and for economy, prevent us from examining internal consistency. Though one-item measures of these variables have shown validity as predictor and outcome variables in previous work (Exline and Wilt 2022a, 2022b, 2022c; Wilt and Exline 2022), they may still be limited in terms of reliable variance and content coverage. This is perhaps another reason we observed weaker associations for event-specific variables. Future work may employ multi-item measures, which would allow for more rigorous psychometric evaluation, including latent variable modeling. More generally, as we relied on self-report, we encourage future studies to employ multiple measures of personality and gratitude (e.g., peer report, behavioral) to examine whether findings generalize across different methods.

Furthermore, the measures of general gratitude and GTG were highly conceptually related, which presents challenges for statistical modeling and interpretation. The event- specific measures of these variables were framed similarly and referenced the same event, and thus, if a person endorsed higher levels of GTG, it is reasonable that they would also endorse higher general gratitude. The trait measure of GTG was derived from the trait measure of general gratitude, possibly resulting in inflated associations between the measures. These features present challenges to isolating the unique variance of GTG apart from general gratitude, and this may be particularly difficult for the event-specific measures since they were more narrowly focused than the trait measures. Indeed, this is another reason why results may have been discrepant across event-specific and trait measures. We encourage future research to use conceptually convergent (like those in this study) and divergent (e.g., different prompts as well as different phrasing of items) measures of GTG and general gratitude. Doing so could allow for estimation of the impact of these potentially thorny measurement issues.

Though many findings were consistent with our hypotheses, future studies may provide more direct tests of our proposed explanations. For instance, a longitudinal study assessing events prospectively could have participants (a) report how many positive events they experienced, (b) list which entities were considered as benefactors, (c) report on whether the event matched with their beliefs about the entity’s characteristics, and (d) report on desire or motivation to credit different entities as benefactors. Experiments could also include manipulations to make different predictors of GTG more salient; in these studies, we would predict that such manipulations would have greater effects on GTG and gratitude for people with higher levels of positive emotional traits and (perhaps) adaptive relational styles.

As we relied on a sample of undergraduates from the U.S. who identified predominantly as either Christian or non-r/s, our findings may not generalize outside of these contexts. We encourage future studies to examine whether results hold across a wider range of ages, as well as other faith traditions and countries. Focusing on polytheistic faiths may be especially interesting because it could allow for comparisons about the processes by which people credit different gods for positive events.

5. Conclusions

This study provided an initial test of whether positive emotional traits and adaptive relational styles predicted GTG in response to a positive event and trait GTG. We found rather strong evidence for the role of positive emotional traits predicting GTG directly as well as indirectly via general gratitude. The evidence for adaptive relational styles was more mixed and nuanced, though agreeableness did have consistent links to GTG. These results present a promising beginning to examining a conceptual framework linking personality to GTG and to general gratitude.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.W.; Data curation, J.A.W. and J.J.E.; Formal analysis, J.A.W.; Funding acquisition, J.A.W. and J.J.E.; Methodology, J.A.W. and J.J.E.; Project administration, J.J.E.; Visualization, J.A.W.; Writing—original draft, J.A.W.; Writing—review & editing, J.A.W. and J.J.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by John Templeton Foundation, grant number 59916; 61513.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Case Western Reserve University (STUDY20201381, 20 October 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data and code are available at [https://osf.io/ztc9j/?view_only=b370c7916af144bc81f483e6ee0e0708]. Data from the larger project will be shard via the Open Science Framework or the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aghababaei, Naser, and Mohammad Taghi Tabik. 2013. Gratitude and mental health: Differences between religious and general gratitude in a Muslim context. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 16: 761–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, Naser, Agata Błachnio, and Masoume Aminikhoo. 2018. The relations of gratitude to religiosity, well-being, and personality. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 21: 408–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, Kim, and Leonard M. Horowitz. 1991. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61: 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, Kelly A., Catherine L. Clark, and Phillip R. Shaver. 1998. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. Edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and William S. Rholes. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, W. Keith, Angelica M. Bonacci, Jeremy Shelton, Julie J. Exline, and Brad J. Bushman. 2004. Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment 83: 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A., Jeffrey Froh, and Rachel Rose. 2019. Gratitude. In Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 317–32. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Seymour. 1979. The stability of behavior: I. On predicting most of the people much of the time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37: 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie J., and Joshua A. Wilt. 2022a. Bringing God to mind: Although brief reminders to not increase gratitude to God, and wording of questions matters, belief in a loving, gift-giving God remains central. Religions 13: 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie J., and Joshua A. Wilt. 2022b. Divine attributions, gift appraisals, and supernatural operating rules as predictors of gratitude to God. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., and Joshua A. Wilt. 2022c. Not just love and safety, but excitement energy, fun, and passion: Relational predictors of gratitude to God and desires to “pay it forward”. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham, Frank D., and Ross W. May. 2021. Generalized gratitude and prayers of gratitude in marriage. The Journal of Positive Psychology 16: 282–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, Gilles E., and Eva T. Szodorai. 2016. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences 102: 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, William G., and Renée M. Tobin. 2009. Agreeableness. In Individual Differences in Social Behavior. Edited by Mark Leary and Rick Hoyle. New York: Guilford, pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Neal. 2006. Gratitude toward God, stress, and health in late life. Research on Aging 28: 163–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, and Christopher G. Ellison. 2009. Social environment of the church and feelings of gratitude toward god. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 1: 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, and R. David Hayward. 2015. Assessing whether trust in God offsets the effects of financial strain on health and well-being. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 25: 307–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, Deborah Bruce, R. David Hayward, and Cynthia Woolever. 2014. Gratitude to God, self-rated health, and depressive symptoms. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 341–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, Robert A. Emmons, and Gail Ironson. 2015. Benevolent images of God, gratitude, and physical health status. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 1503–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Kibeom, and Michael C. Ashton. 2004. Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research 39: 329–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, David P., Chondra M. Lockwood, and Jason Williams. 2004. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research 39: 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, Michael E., Robert A. Emmons, and Jo-ann Tsang. 2002. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 112–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, Jenae M., Sam A. Hardy, and Philip Watkins. 2022. Transcendent indebtedness to God: A new construct in the psychology of religion and spirituality. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L., Joshua A. Wilt, and Adam B. David. 2022. Distinctiveness of gratitude to God: How does this construct add to our understanding of religiousness and gratitude? Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2004. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 36: 717–31. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Revelle, William R. 2022. psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. Evanston: Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Morris. 1965. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin, David H., Steven Pirutinsky, Adam B. Cohen, Yardana Galler, and Elizabeth J. Krumrei. 2011. Grateful to God or just plain grateful? A comparison of religious and general gratitude. The Journal of Positive Psychology 6: 389–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Christina Frederick. 1997. On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality 65: 529–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoughi, Majid, and Fatemeh Hesampour. 2020. Prediction of psychological well-being in the elderly by assessing their spirituality, gratitude to god, and perceived social support. Iranian Journal of Ageing 15: 144–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheier, Michael F., and Charles S. Carver. 1987. Dispositional optimism and physical well-being: The influence of generalized outcome expectancies on health. Journal of Personality 55: 169–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheier, Michael F., Charles S. Carver, and Michael W. Bridges. 1994. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, Christopher J., and Oliver P. John. 2017. The next Big Five Inventory (BFI-2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113: 117–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upenieks, Laura, and Joanne Ford-Robertson. 2022. Give thanks in all circumstances? Gratitude toward God and health in later life after major life stressors. Research on Aging 44: 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Tongeren, Daryl R., Don E. Davis, Joshua N. Hook, and Charlotte vanOyen Witvliet. 2019. Humility. Current Directions in Psychological Science 28: 463–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, Philip, Michael Frederick, and Don E. Davis. 2022. Gratitude to God predicts religious well-being over time. Religions 13: 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, David, Jerry Suls, and Jeffrey Haig. 2002. Global self-esteem in relation to structural models of personality and affectivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83: 185–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, Brandon L., and Steven J. Scher. 2010. Prayer and subjective well-being: An examination of six different types of prayer. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, Joshua A., and Julie J. Exline. 2022. Receiving a gift from God in times of trouble: Links between gratitude to God, the affective circumplex, and perceived closeness to God. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 25: 362–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, Joshua A., and William Revelle. 2016. Extraversion. In The Oxford Handbook of the Five Factor Model of Personality. Edited by Thomas A. Widiger. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilt, Joshua A., Julie J. Exline, and Eric D. Rose. 2020. Personality, spirituality, and religion. In The Oxford Handbook of Psychology and Spirituality. Edited by Lisa Miller. New York: University of Oxford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Alex M., Jeffrey J. Froh, and Adam W. A. Geraghty. 2010. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review 30: 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Alex M., Stephen Joseph, and John Maltby. 2009. Gratitude predicts psychological well-being above the Big Five facets. Personality and Individual Differences 46: 443–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata, and Dariusz Krok. 2021. Disclosure to God as a mediator between private prayer and psychological well-being in a Christian sample. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 1083–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).