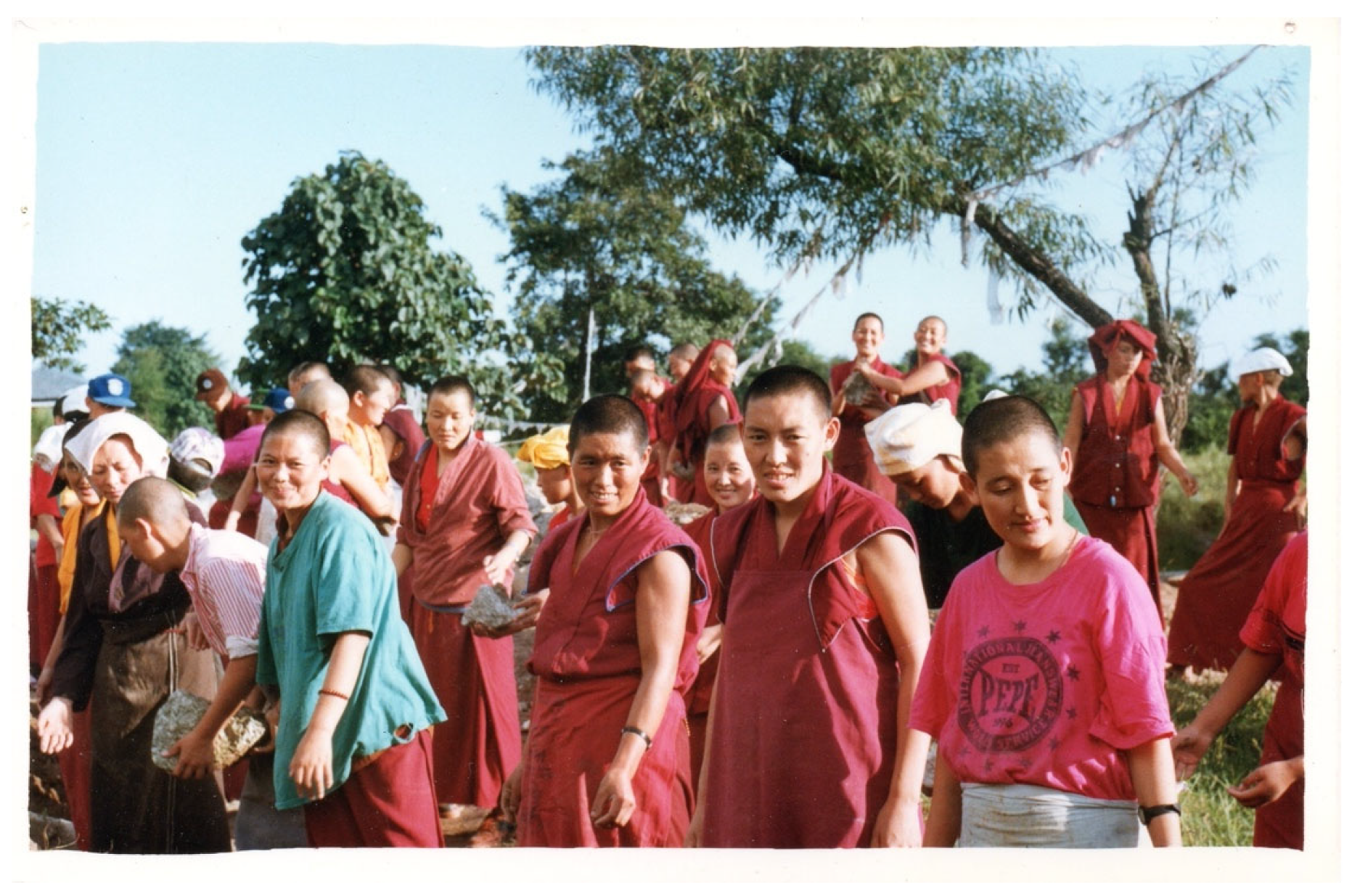

A Revolution in Red Robes: Tibetan Nuns Obtaining the Doctoral Degree in Buddhist Studies (Geshema)

Abstract

:“It is all mainly because of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s vision and his true care and kindness for his womenfolk”.(Rinchen Khandro Choegyal 2016)

1. Introduction

2. Monastic Education in the Past

3. Opening Up Education for Nuns

4. Seeking Recognition

5. Going for Examination

6. Female Emancipation and Monastic Education

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The other three are: the Nyingmapa (rNying ma pa), the Kagyüpa (bKa’ rgyud pa), and the Sakyapa (Sa skya pa) schools. |

| 2 | In contrast to monasteries (dgon pa), most religious encampments only existed for a short time and were then either dissolved or transformed into proper monasteries. Examples of religious encampments which proposed higher Buddhist studies for monks and nuns were those founded by the Third Dragkar Lama from the Gelukpa school (Schneider 2011) and Adzom Gar (A ’dzom sgar), from the Nyingmapa school, situated in the Tromtar (Trom tar) region of Kham (personal communication from the nun Sherab Wangmo, born 1947). Contemporary religious encampments such as Larung Gar (bLa rung sgar) and Yachen Gar (Ya chen sgar) tend to exist for longer time. |

| 3 | These statistics were issued by the Central Tibetan Administration in exile few years after the flight of the Dalai Lama followed by many Tibetans to South Asia. There exist different estimations of the number of monks and nuns and their institutions (e.g., Goldstein 2009; Jansen 2018; Ryavec and Bowman 2021), but they only refer to Central Tibet, leaving out Tibetan populations living in the two eastern regions of Amdo and Kham. |

| 4 | It must be emphasised that these numbers only represent a very rough estimate. See Goldstein (2009, p. 411); Samuel (1993, pp. 578–82) precises that these number only concern centralised Tibetan areas. |

| 5 | My estimate if we take the 27,000 nuns stated in the statistic of the Central Tibetan Administration for granted; and even more if we add an approximate number of “household” nuns. Ryavec and Bowman (2021, p. 209) suggest a proportion of 6% of the female population, but as already stated, this cannot apply to the whole area populated by Tibetans, especially because nunneries were only very rare in Kham and Amdo (Schneider 2013). |

| 6 | For Thailand, another important Buddhist country, Stanley Tambiah (1976, pp. 266–67) estimates the number of monks as 1–2% of the male population. As for Catholic nuns, Langlois (1984, p. 39) estimates that nearly 1% of the female population were nuns—mostly congregationalists—at the peak in 1880. |

| 7 | For more information on the khenmo degree as bestowed mainly in the religious encampment Serthar Larung Gar (gSer thar bLa rung sgar) in Tibet, see Schneider (2013, pp. 153–61), Liang and Taylor (2020) and Padma’tsho/Baimacuo (2021). |

| 8 | Concerning the financing of convents in another context, Zanskar, see Gutschow (2004, pp. 77–122). |

| 9 | In this article, I will not treat the developments among Western practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism. |

| 10 | There were no secular universities in traditional Tibet, only public and private schools. |

| 11 | See for instance Dreyfus (2003, pp. 10–13). See also Cabezón (1994, pp. 11, 13) and Kværne (2014, p. 85) for a discussion on scholasticism in Tibet. |

| 12 | There is also the religious tradition of the Bonpo, which even though distinct from Buddhism, has adopted many of its characteristics, especially when it comes to monasticism and education, as we will see later. |

| 13 | Namely, Gadong (dGa’ gdong), Kyormolung (sKyor mo lung), Zulphu (Zul phu), Dewachen (bDe ba can), Sangphu (gSang phu) and Gungthang (Gung thang). |

| 14 | Personal information, WeChat discussion August 2019; this thesis is also reported by Dreyfus (2003, p. 6). |

| 15 | It is interesting to remark here that in the contemporary religious encampment of Larung Gar, in Serthar (Eastern Tibet), where nuns are trained alongside monks to become khenmos, the debate part was only introduced into their curriculum in 2014 (and earlier for monks) and into the chart of their examinations in 2017, while the diploma and title itself were awarded since the early 1990s. See Padma’tsho/Baimacuo (2021, p. 16). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Ms Rinchen Khandro is married to Mr Tenzin Choegyal or Ngari Rinpoche, the youngest brother of His Holiness the Dalai Lama; moreover, she served as Minister of Education in the Central Tibetan Administration in exile from 1993 to 2001. |

| 18 | See Karma Lekshe Tsomo (1988) for further information. Several international foundations with the aim of supporting Tibetan Buddhist nuns were set up at the same time or shortly after. To name just a few, these are: the Jamyang Foundation, especially reaching to nuns from the Indian Himalayas, founded by Venerable Karma Lekshe Tsomo, a Tibetan Buddhist nun from Hawai (and co-founder of Sakyadhītā); the Gaden Choling Foundation from Toronto supporting in particular nuns from Zangksar; and Tsoknyi Humanitarian Foundation taking care of nuns from Nangchen (Tibet). |

| 19 | The eclectic or non-sectarian approach in Tibetan Buddhism was promulgated by religious masters of the nineteenth-century rimé movement who wanted to come to an end with sectarian quarrels. In exile, the rimé approach is supported by many masters and above all by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama himself. |

| 20 | The Institute for Buddhist Dialectical Studies, also located in Dharamsala, was founded in 1973. For more information on its monastic training, see Lobsang Gyatso (1998) and Kværne (2014). |

| 21 | One idea behind secular education is also that some nuns might not stay nuns all their life and thus might adapt to lay life in future. Even though this has proved to be true, the subject is rarely talked about openly. |

| 22 | Within the framework of the “Mind and Life” exchange program, initiated by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Emory University in the USA, monks and nuns are invited to take part in annual workshops to study sciences for three years. Nuns from different nunneries have been participating in these workshops since 2011. At the end of this training, they receive a diploma. |

| 23 | Dolma Ling has a media centre where two nuns are working full-time and others temporarily. |

| 24 | On the role and value of memorisation in the context of monastic education, see Dreyfus (2003, pp. 91–97). |

| 25 | |

| 26 | For more information on the traditional “winter debate,” see Dreyfus (2003, pp. 234–36) and http://web.archive.org/web/20101203161011/http:/www.qhtb.cn/buddhism/view.jsp?id=171 (accessed on 25 July 2022). |

| 27 | For more information on full ordination in Tibetan Buddhism, see Price-Wallace and Wu in this volume. |

| 28 | |

| 29 | Some more Western nuns have studied in the Institute for Buddhist Dialectical, but up to then, none of them had gone so far in their studies. |

| 30 | |

| 31 | Since 1963, the heads and representatives of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism and the Bon tradition meet regularly in order to decide on major issues pertaining to religion. |

| 32 | She and her husband, Ngari Rinpoche, like Pema Chhinjor had been involved in the establishment of the Tibetan Youth Congress, the biggest Tibetan NGO in exile. |

| 33 | Personal communication from Rinchen Khandro (August 2012), which was confirmed by Thupten Tsering, joint secretary at the Department of religion and culture at this time. |

| 34 | |

| 35 | In Tibetan: Bod kyi btsun dgon dang slob gnyer khang gi gzhung chen bslab pa mthar son btsun ma rnams la dge bshes ma’i rgyugs sprod dang lag ’khyer ’bul phyogs kyi sgrigs gzhi/. |

| 36 | Up to then, nunneries did not follow exactly the same program as stipulated in the constitution. Thus, the new rules obliged them to adapt some of their courses. |

| 37 | Examinations are organised by turn in the different nunneries and each year during the fifth month (later changed to the eighth month); moreover, they are oral and written with three hours for principal subjects and three hours for secondary subjects, as well as a fifteen-minute test of debate. |

| 38 | Śākyaprabha (8th century) was one of the early translators and commentators on the Buddha’s teachings. He was a disciple of Śāntarakṣita, the famous Indian master who ordained the first Tibetan monks, and a crucial link in the Vinaya tradition which is followed in Tibet. See Gardner (2019) and URL: http://www.rigpawiki.org/index.php?title=Shakyaprabha (accessed on 25 March 2022). |

| 39 | Personal communication from Geshe Rinchen Ngödrub (15 August 2012). Interestingly, Georges Dreyfus (2003: 114) questions the relevance of Vinaya studies in the monastic curriculum altogether saying that “these texts contribute little to the intellectual qualities most valued by Tibetan scholars” and pointing to the fact that the “actual organisation of the order in Tibet derives not from the Vinaya but from the monastic constitution” (bca’ yig), which gives the rules elaborated by each monastery itself. For more on monastic constitutions, see Jansen (2018). |

| 40 | Moreover, the Gandentripa, Thubten Nyima Lungtok Tenzin Norbu, was the very first to hold this position who is ethnically not a Tibetan, but a Ladakhi, even though he did his studies in Tibet and in Tibetan monasteries in exile. |

| 41 | These are the same nunneries as stated above: Jangchub Chöling located in Mundgod, Khachö Gakyil Ling situated in the Katmandu valley and Geden Chöling, Jamyang Chöling and Dolma Ling in the area of Dharamsala. |

| 42 | It might have been either a device used purposedly by the director of TNP who comes originally from Kham herself or because of elderly geshes not willing to participate in the event. |

| 43 | Originally, the graduation ceremony should have taken place in Dharamsala, at the main temple; however, it was decided finally that it would be more suitable to held it in south of India, where more Tibetans would be able to attend. |

| 44 | At the time of finalising this article (August 2022), ninety-three nuns from six nunneries (for the first time, a nun from Changsem Ling [Byang sems gling] in Kinnaur takes part) are passing their geshema examen in Geden Choeling nunnery, Dharamsala. Two of the examinators have come from Drepung monastery, two from Ganden monastery and the questions and corrections are dealt by another two geshes from Sera monastery. The Geshema committee comprising two geshemas, a nun and a geshe teacher from Dolma Ling supervise the whole procedure. |

| 45 | Many photos and congratulations were sent through the social media application WeChat, largely used in China; however, it has been banned in India since June 2020 and can no longer be accessed. |

| 46 | To my knowledge, some geshemas are now teaching in Jamyang Choeling nunnery as well. |

| 47 | When visiting Tibet in 2018 and 2019, I saw nuns from Dragkar nunnery and Lamdrak nunnery debating in Kandze (Eastern Tibet); they were then studying the pharchin (Perfection of Wisdom) part of the curriculum. I learnt that in Ngaba, Gelukpa nuns are also studying in order to become geshemas. |

| 48 | In the past, Bonpo scholars used to join one or other of the Gelukpa monastic universities in order to deepen their knowledge, with some also passing the geshe degree. One of them was the eminent Professor Samten Karmay, who later became a researcher at the CNRS in Paris. |

| 49 | Personal communication from Kalsang Norbu Gurung (January 2020). Geshe Söpa Gyurme went back to Tibet in the early 2000s. |

| 50 | Personal communication from Kalsang Norbu Gurung (January 2020). According to Chech (1986, p. 11), the curriculum of the Bonpos in Menri monastery lasted eight years in 1986; it has been expanded over time to thirteen years (Ramble 2013, p. 7). |

| 51 | In the nunnery of Ratna Menling, the study program actually covers a total of eleven years, but because this was the first group of nuns to obtain the geshema degree, it was decided to expand the first two years (covering the topics of düdra [bsdus grwa] and tshema [tshad ma]) to four years. Personal communication from geshema Phuntsok Tzulzin (August 2022). See also Central Tibetan Administration (14 March 2022) and https://ybmcs.org/redna-menling-nunnery/ (accessed on 15 July 2022). |

| 52 | Edited by bLa rung ārya tāre’i dpe tshogs rtsom sgrig khang (2017). |

| 53 | I have been visiting and studying Tashi Gönsar since 1999, initially as part of my Ph.D. (Schneider 2013). |

| 54 | However, opinions are diverging on this matter, some also thinking that the ordination status has nothing to do with academic degrees. Personal communication from Khenpo Tenkyong (August 2022). For instance, in Tibet (Larung Gar and Tashi Gönsar), the lacking gelongma status has not been a problem. |

| 55 | Personal communication from Khenpo Tenkyong (March 2022). |

| 56 | See (Tibetan Nuns Project 2022) and (Voice of Tibet 2022); https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J57KHRjx0l8 (accessed on 30 July 2022). |

| 57 | Personal communication from Khenpo Yeshe Tsering (August 2022). |

| 58 | Conference given at the Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations, 14 September 2016 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFUzfku_nzg (accessed on 30 March 2022)). |

References

- bLa rung ārya tāre’i dpe tshogs rtsom sgrig khang, ed. 2017. mKha’ ’gro’i chos mdzod chen mo (Ḍākinīs’ Great Dharma Treasury). 53 vols. Lhasa: Bod ljongs bod yig dpe rnying dpe skrun khang. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezón, José Ignacio. 1994. Buddhism and Language: A Study of Indo-Tibetan Scholasticism. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Central Tibetan Administration. 2011. Tibetan Buddhist Religious Leaders Meet For 11th Biannual Conference. TibetNet. Available online: https://tibet.net/tibetan-buddhist-religious-leaders-meet-for-11th-biannual-conference/ (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Central Tibetan Administration. 2019. Chorig Kalon Attends Completion of One Year Tantric Course for Geshemas. TibetNet. Available online: https://tibet.net/chorig-kalon-attends-completion-of-one-year-tantric-course-for-geshemas/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Central Tibetan Administration. 2022. Secretary Chime Tseyang attends Ratna Menling Nunnery’s Commencement of Geshema Degree to its first batch of Karampa. TibetNet. Available online: https://tibet.net/secretary-chime-tseyang-attends-ratna-menling-nunnerys-commencement-of-geshema-degree-to-its-first-batch-of-karampa/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Chech, Krystyna. 1986. History, Teaching and Practice of Dialectics According to the Bon Tradition. The Tibet Journal 11: 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- ’Chi med g.yung drung. 2018. Khri ka’i khyung mo dgon du btsun ma’i dge bshes kyi mdzad sgo spel ba. Himalayabon. Available online: https://www.himalayabon.com/news/2018-10-15/1378.html (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Dreyfus, Georges. 2003. The Sound of Two Hands Clapping: The Education of a Tibetan Buddhist Monk. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ehm, Chandra C. 2020. Queens Without a Kingdom Worth Ruling. Tibetan Buddhist Nuns and the Process of Change in Tibetan Monastic Communities. Paris: Diplôme de l’École Pratique des Hautes Études (Quatrième Section), Sciences Historiques et Philosophiques. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Alexander. 2010. Dromton Gyelwa Jungne. The Treasury of Lives. Available online: https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Dromton-Gyelwa-Jungne/4267 (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Gardner, Alexander. 2019. Śākyaprabha. The Tresaury of Lives. Available online: https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/%C5%9A%C4%81kyaprabha/P4CZ16819 (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. 1999. The Revival of Monastic Life in Drepung Monastery. In Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet: Religious Revival and Cultural Identity. Edited by Melvyn C. Goldstein and Matthew T. Kapstein. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 15–52. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. 2009. Bouddhisme tibétain et monachisme de masse. In Moines et moniales de par le monde. La vie monastique au miroir de la parenté. Edited by Adeline Herrou and Gisèle Krauskopff. Paris: L’Harmattan, pp. 409–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gutschow, Kim. 2004. Being a Buddhist Nun. The Struggle for Enlightenment in the Himalayas. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Berthe. 2018. The Monastery Rules. Buddhist Monastic Organization in Pre-Modern Tibet, Oakland, California. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Josayma, Tashi Tsering. 2017. The Representation of Women in Tibetan Culture. Strengths and Stereotypes. The Tibet Journal 42: 111–41. [Google Scholar]

- Karma Lekshe Tsomo, ed. 1988. Sakyadhītā, Daughters of the Buddha. Ithaca and New York: Snow Lion Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kværne, Per. 2014. The traditional academic training for the Geshé degree in Tibetan monastic scholasticism. In L’educazione nella società asiatica—Education in Asian societies. Edited by Kuniko Tanaka. Milano and Roma: Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Bulzoni Editore, pp. 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois, Claude. 1984. Le catholicisme au féminin. Archives des Sciences Sociales des Religions 57: 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, Michael. 2012. Discipline and Debate: The Language of Violence in a Tibetan Buddhist Monastery. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Julie, and Andrew S. Taylor. 2020. Tilling the Fields of Merit: The Institutionalization of Feminine Enlightenment in Tibet’s First Khenmo Program. Journal of Buddhist Ethics 20: 231–62. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, Kenneth. 2007. Dialectical Practice in Tibetan Philosophical Culture. An Ethnomethodological Inquiry into Formal Reasoning. Lanham, Boulder, New York and Toronto: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lobsang Gyatso. 1998. Memoirs of a Tibetan Lama. Ithaca and New York: Snow Lion Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mrozik, Susanne. 2009. A Robed Revolution: The Contemporary Buddhist Nun’s (Bhikṣuṇī) Movement. Religion Compass 3: 360–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padma’tsho/Baimacuo. 2021. How Tibetan Nuns Become Khenmos: The History and Evolution of the Khenmo Degree for Tibetan Nuns. Religions 12: 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, Daniel E. 1976. Debate in Tibetan Buddhist Education. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Phayul. 2011. Tibetan Buddhist Leaders Meet to Talk Dalai Lama’s incarnation. Phayul. Available online: http://www.phayul.com/news/tools/print.aspx?id=30045&t=0 (accessed on 3 November 2013).

- Phayul. 2012. Geshema Degree Becomes a Reality. Phayul. Available online: https://www.phayul.com/2012/05/22/31441/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Plachta, Nadine. 2016. Redefining monastic education. The case of Khachoe Ghakyil Ling Nunnery in the Kathmandu Valley. In Religion and Modernity in the Himalaya. Edited by Megan Adamson Sijapati and Jessica Vantine Birkenholtz. London: Routledge, pp. 129–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ra se dkon mchog rgya ’tsho. 2003. Gangs ljongs skyes ma’i lo rgyus spyi bshad (General History of Women in Tibet). Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang. [Google Scholar]

- Ramble, Charles. 2013. The Assimilation of Astrology in the Tibetan Bon Religion. Extrême-Orient Extrême-Occident 35: 199–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roesler, Ulrike. 2015. The Vinaya of The Bon Tradition. In From Bhakti to Bon: Festschrift for Per Kvaerne. Edited by Hanna Havnevik and Charles Ramble. Oslo: Novus forlag (The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture), pp. 431–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ryavec, Karl E., and Rocco N. Bowman. 2021. Comparing Historical Tibetan Population Estimates with the Monks and Nuns: What was the Clerical Proportion? Revue d’Études Tibétaines 61: 209–31. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, Geoffrey. 1993. Civilized Shamans. Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point. [Google Scholar]

- Ser byes lha rams ngag gi dbang phyug Rin chen dngos grub. 2007. Dge slong ma’i dka’ gnad brgya pa sngon med legs par bshad pa’i gter dgos ’dod kun ’byung baiDUrya’i phung po (Key issues of gelongma). Sidhpur: Tibetan Nuns Project. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Nicola. 2011. The Third Dragkar Lama: An Important Figure for Female Monasticism in the Beginning of Twentieth Century Khams. In Revisiting Tibet’s Culture and History. Proceedings of the Second International Seminar of Young Tibetologists, 7–11 September 2009, Vol. 1, Revue d’Études Tibétaines, No. 31. October. Edited by Nicola Schneider, Alice Travers, Tim Myatt and Kalsang Norbu Gurung. pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Nicola. 2012. The Ordination of Dge slong ma: A challenge to Ritual Prescriptions. In Revisiting Rituals in a Changing Tibetan World. Edited by Katia Buffetrille. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 109–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Nicola. 2013. Le Renoncement au Féminin. Couvents et Nonnes dans le Bouddhisme Tibétain. Nanterre: Presses Universitaires de Paris Ouest. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Nicola. 2015. Female incarnation lineages: Some remarks on their features and functions in Tibet. In From Bhakti to Bon: Festschrift for Per Kvaerne. Edited by Hanna Havnevik and Charles Ramble. Oslo: Novus forlag (The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture), pp. 463–79. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, Anne. 2017. Die Ehrwürdige. Kelsang Wangmo aus Deutschland wird zur Ersten weiblichen Gelehrten des tibetischen Buddhismus. Salzburg and München: Benevento Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tambiah, Stanley J. 1976. World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study pf Buddhism and Polity in Thailand against a historical Background. Cambridge, London and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tenzin Dharpo. 2020. Two Additional Election Commissioners Elected. Phayul. Available online: https://www.phayul.com/2020/07/28/44083/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- The Tibet Express. 2012. Tibetan Nuns Set to Receive PhD Degrees. The Tibet Express. Available online: http://www.tibetexpress.net/en/news/exile/8293-2012-05-23-09-57-05 (accessed on 20 November 2013).

- Tibetan Nuns Project. 2022. blog Post. June 22. Available online: https://tnp.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Voice of Tibet. 2022. bTsun ma’i sa skya mtho slob tu btsun ma gsum la ches thog ma’i mkan mo’i mtshan gnas stsal ba/ (The First Three Nuns Who Are Awarded the Khenmo Degree at the Monastic University of Sakya). Available online: https://vot.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

| Class | Number of Years |

|---|---|

| Preliminary studies (including Pramāṇa; Tib. tshad ma) | 4 |

| “Perfection of Wisdom” (Skt. Prajñāpāramitā; Tib. phar phyin) | 7 |

| “Middle Path” (Skt. Mādhyamika; Tib. dbu ma) | 3 |

| “Phenomenology” or “meta-doctrine” (Skt. Abhidharma; Tib. mngon pa) | 3 |

| “Monastic discipline” (Skt. Vinaya; Tib. ’dul ba) | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schneider, N. A Revolution in Red Robes: Tibetan Nuns Obtaining the Doctoral Degree in Buddhist Studies (Geshema). Religions 2022, 13, 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090838

Schneider N. A Revolution in Red Robes: Tibetan Nuns Obtaining the Doctoral Degree in Buddhist Studies (Geshema). Religions. 2022; 13(9):838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090838

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchneider, Nicola. 2022. "A Revolution in Red Robes: Tibetan Nuns Obtaining the Doctoral Degree in Buddhist Studies (Geshema)" Religions 13, no. 9: 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090838

APA StyleSchneider, N. (2022). A Revolution in Red Robes: Tibetan Nuns Obtaining the Doctoral Degree in Buddhist Studies (Geshema). Religions, 13(9), 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090838