1. Introduction

Meditation may be viewed as a set of mental activities, such as focusing, observing, and releasing, the practice of which leads to altered states of consciousness, contemplative growth, and ultimately “awakening” or “enlightenment” (

Sparby and Sacchet 2022). While it may be argued that different forms of meditation share features on the level of activity, the spiritual frameworks that the activities are understood within may, however, differ strongly. Often disregarding these spiritual frameworks, recent research has shown that meditation has several benefits to human health and functioning. Not only does meditation benefit physical and mental health (

Rose et al. 2020;

Schlechta Portella et al. 2021), it has also been found to increase resiliency, well-being, cognitive function, and prosocial attitudes (

Luberto et al. 2018;

Sedlmeier et al. 2018). However, it is also becoming clear that there exists a range of potentially negative meditation effects (

Lindahl et al. 2017), which may be defined as effects that are either unpleasant, distressing, painful, etc., or cause harm, in the sense of an increase in symptoms or a decrease in functioning. One study found that about 25% of regular meditators may experience very unpleasant events (

Schlosser et al. 2019), while another found that around 10% of meditators experience functional impairment (

Goldberg et al. 2021); although most of these resolve within a day or less, 1.4% experience impairment lasting from one month to a year (0.7%) or longer (0.5%). We may refer to unpleasant effects as

subjective negative effects and harm/functional impairment as

objective negative effects. While subjective negative effects are often linked to objective ones (e.g., a symptom increase may be distressing or painful), this is not always the case: something may be unpleasant without causing harm.

What makes matters deeply complex is that subjectively and objectively negative experiences may be related to what makes meditation beneficial. For example, encounters with difficult emotions may represent opportunities for developing essential meditation skills such as equanimity (

Desbordes et al. 2015;

Eberth et al. 2019); a temporary depletion of cognitive capacity after meditation sessions may be unavoidable for meditative growth (

Creswell 2017); and an increase in mindfulness may lead a meditator to becoming more susceptible to forming false memories (

Wilson et al. 2015). Since strong emotions help support the creation of memories, increased susceptibility to false memories may be due to the lessening of emotional reactivity to an experience that is cultivated through mindfulness. Even for meditation teachers, it may be hard to assess whether a negative experience is a sign of progress or a pathology (

Lindahl et al. 2020). Clearly, there is a need for an overarching framework that enables us to formulate what negative effects consist of, how meditation involves risk of harm, and how negative effects may be connected to positive ones.

1.1. Hindrances in the Contemplative Traditions

Involving the perspective of the contemplative traditions as well as of contemporary practitioners may be particularly informative for developing such a framework. There are different reasons for this. Firstly, there already exists traditional frameworks within which negative experiences are defined, assessed, and considered in relation to their potential benefit. Within the Buddhist tradition, such experiences are often referred to as the hindrances, and different strategies are presented for either removing or reducing negative effects or transforming them into beneficial ones.

Secondly, the contemplative traditions contain and are based on fundamental or strong evaluations of what is worth wanting (

Taylor 1985, p. 3) that may conflict with contemporary, secular perspectives in general and clinical ones in particular. For example, for a Franciscan monk, poverty may be represent the ideal way of life; for a Yogi, holding up an arm over the head until it atrophies or similar practices of the body may be a part of a process of renunciation that ultimately results in enlightenment (

Hausner 2007); for a devout Christian, such as Julian of Norwich, illness and voluntary isolation represent means of coming closer to the divine (

Norwich 2017). This is not to say that the contemplative traditions are necessarily at odds with contemporary values. Buddhism itself was defined by rejecting extreme asceticism, formulating a “middle way” between sensory pleasure and renunciation. What should be evident, however, is that defining what a “negative effect” consists of will rely on deep evaluations about what is worth wanting, and such evaluations may be conflicting. Still, the fact that conflicting evaluations exist does not mean that it is impossible to find common ground. Indeed, even if a contemplative person values illness, it is most likely not the illness itself that is valued, but rather the possibilities inherent in it as a means of orienting oneself towards what is truly worth wanting—such as heaven in the case of Christianity—which is likely to also include health in some way. However, for contemplative science (

Sparby 2017) to accurately assess what counts as a negative effect, it is necessary to approach the contemplative traditions with a sensitivity toward such nuance.

This article seeks to draw on insights from the contemplative traditions in order to help formulate what negative effects are and to support further reflection on how negative effects may represent opportunities for growth or spiritual progress. Hence, we will primarily consider the first issue described above in relation to the contemplative traditions, that is, the concept of meditation hindrances and how they form an integral part of meditative or spiritual development. Clear comprehension in relation to this is essential for further considerations about the strong evaluations of the contemplative traditions.

1.2. Contemplative Science of Meditation Hindrances

Turning to contemplative science, we find that research on meditation hindrances as such is scarce. In the Meditation Depth Questionnaire (MEDEQ) developed by Piron (

Piron 2001), the first level of depth is called “hindrances” (e.g., restlessness, busy mind, laziness, feeling bored). After hindrances, one progresses through further levels of depth, referred to as relaxation, concentration, transpersonal qualities, and non-duality. Katyal and Goldin found that experienced meditators experience fewer “hindrances” (e.g., drowsiness, distraction), in comparison to novice ones, and that alpha waves were negatively correlated with hindrances, while theta waves were positively correlated with them (

Katyal and Goldin 2021). Van Dam et al. have developed the Behavioral Tendencies Questionnaire, inspired by the Buddhist classification of temperaments as approach, avoid, or equivocate (

Van Dam et al. 2015). These temperaments relate to the fundamental three hindrances in Buddhism (greed, hate, and ignorance); the fact that personality may be defined according to these hindrances may indicate that the type of hindrance a person will tend to encounter reflects their personality structure. Zeng et al. developed the Difficulties During Meditation Involving Immeasurable Attitudes Scale (DMIAS), which identifies two hindrances: a lack of concentration and a lack of prosocial emotions, which were negatively correlated with other positive emotions generated by the four immeasurables or brahmavihārās, which consists of loving-kindness, compassion, empathetic joy and equanimity (

Zeng et al. 2019). If we accept that the benefits of meditation are connected to the generation of positive emotions and other positive qualities and that the presence of hindrances block this generation, the modest or lacking effects found in meditation studies (

Sedlmeier et al. 2018) may potentially be explained by the presence of hindrances.

Furthermore, Russ et al. have developed the Early Meditation Hindrances Scale to better understand the high attrition rates among participants in meditation programs (

Russ et al. 2017). High attrition is problematic, since it makes meditation research unreliable. It also implies low efficiency of health care spending. The reason for the attrition may be that novice practitioners have a misinformed idea about how meditation practice unfolds. Initial practice may be characterized by much mind-wandering and many unpleasant bodily sensations, so it is vital that these are not taken as signs that a person is incapable or unfit for meditation. However, it is doubtful whether “hindrances” are only a problem for novice practitioners. Hindrances may increase and even become stronger in later stages of practice (

Ingram 2018;

Sparby 2019;

Yates et al. 2015), and they may unfold in a non-linear way, indicating that Piron’s levels of depth and similar linear models must be amended.

The idea that hindrances impede meditation practice and spiritual progress more generally may be called the

dual conception of the hindrances. However, as indicated above, when considering traditional texts, it becomes apparent that the matter is complex: hindrances are not always simply hindrances. They also, for example, represent opportunities for deep meditative work, for instance, by taking hate and desire as meditation objects. The hindrances may even be intentionally sought out and consciously increased as a part of meditation practice. Such work, especially the latter form, represents a dissolution of the clear boundaries between what is negative and positive, as what is “negative”, the hindrances, are seen as special opportunities for realization. This dissolution of the clear boundaries between positive and negative may itself be seen as an expression of

non-dual conceptions of the hindrances. What the dual and non-dual ideas of the hindrances consist of will be developed and discussed in-depth below. For now, it can be pointed out that non-dual conceptions of the hindrances present a problem, in that some hindrances may represent harmful negative effects. Hence, the idea of using the hindrances as a part of the process potentially represents a specific challenge to practitioners. Investigating this issue will help us understand related issues such as under what conditions negative effects present learning opportunities. In addition, it will also help us make our understanding of negative effects more complete. That difficult meditation experiences may indeed represent learning experiences has recently been confirmed by Baer et al. (

Baer et al. 2021). However, exactly how meditation difficulties may be connected to benefits has yet to be studied systematically by contemplative science.

More broadly, it is important to study meditation hindrances for a number of reasons. It is important to study them not only because it helps us understand and more clearly define what negative meditation experiences consist of but also because it may help us understand and guide both novice and more experienced meditation practitioners through growth-related challenges. Furthermore, understanding meditation hindrances, and especially how they can be overcome through dual and non-dual means, may make meditation training more efficient by identifying hindrances that are avoidable and not growth-related. More effective mediation practice may, in turn, reduce the clinical costs involved in meditation treatments. However, an orientation towards goals and effectiveness may itself represent a hindrance: a kind of hindrance (striving) that is addressed in the traditions. Meditation programs that have developed out of such a mindset may indeed be less effective, insofar as they as they are based on misunderstanding of what meditation practice is about that inadvertently creates hindrances for it. This does not have to mean that there are no ways of making meditation, or at least the way one deals with hindrances, more effective—strategies for dealing with hindrances are indeed also a concern in the traditions, though the way they are formulated is perhaps more in harmony with a meditative mindset. In other words, the dialogue with the contemplative traditions is vital for contemplative science to progress in an informed and balanced way.

Below, we will first consider different dual conceptions of the hindrances (

Section 2). Then, we consider different non-dual conceptions, giving examples from Mahamudra, tummo and karmamudra from the Six Yogas of Naropa, and chöd (

Section 3). In the discussion, we will investigate what dual and non-dual conceptions of the hindrances may have in common and what differentiates them from each other. Furthermore, a scale of dual and non-dual practices is presented. How different approaches may be placed on this scale will be suggested, given that extreme dual and extreme non-dual approaches appear to converge. An outline of the potential advantages and disadvantages of the different approaches will also be given, before a conclusion is reached (

Section 4).

2. Dual Conceptions of the Hindrances

In the following, the traditional dual views of the hindrances in contemplative traditions generally are presented, before we look more specifically into Buddhist accounts. Having considered these, we turn to contemporary dual accounts of the hindrances found in meditation manuals.

2.1. Traditional Dual Conceptions of the Hindrances

Descriptions of hindrances to contemplative practice can be found in different traditions. Before presenting Buddhist views of the hindrances, we will briefly consider other traditions. Evagrius of Pontus’

Antirrhetikos—also referred to as

A Monastic Handbook for Combating Demons (

Brakke 2009)—gives a list of hindrances to the monastic life, ranging from “thoughts of gluttony” to “thoughts of cursed pride”. The method of combating the demons consists of speaking specific Bible verses that correspond to the demonic interference. Other and much later Christian meditation manuals, such as

The Graces of Interior Prayer (

Poulain 2016), also treat hindrances and obstacles that may arise through meditation practice but do not give a systematic account of how they arise and how they may be dealt with. Note, however, that the Christian tradition contains numerous treatises on the origin of sin or vices such as gluttony and pride, and these treatises also give a systematic account of how vices are overcome through corresponding virtues (

Bejczy 2011, p. 225). Sometimes, as in the scheme of the seven deadly sins, pride is seen as the root of the other sins (

Climacus 1982, p. 20); although, it is debated, for example, by Augustin, whether the original sin of Adam is a result of ignorance or pride (

Couenhoven 2008).

Patanjali’s

Yoga Sutras contain a succinct account of the roots of the hindrances to yoga (kleśa) (

Bryant 2009). The hindrances to deep meditation, samādhi, are ignorance, attachment, aversion, ego-consciousness, and will to live (

Bryant 2009, pp. 68, 69). Ignorance may be regarded as the root of the other hindrances (

Bryant 2009, p. 180). Further

disturbances to practice are also listed (I.30): disease, idleness, doubt, carelessness, sloth, lack of detachment, misapprehension, failure to attain a base for concentration, and instability (

Bryant 2009, p. 134). The siddhis—supernatural powers—are also considered hindrances (

Bryant 2009, pp. 318, 354). Hindrances are blocked by samādhi (concentration states) and finally uprooted through insight and deep meditation (

Bryant 2009, pp. 388–89).

In the Buddhist tradition, we find the three poisons or three roots of evil (akusala-mula): greed, hate, and delusion (

Keown 2003, p. 8). These three are said to have their root in desire or craving and, hence, contribute to suffering (

Keown 2003, p. 310). Three of these poisons can be found in the classic or early Buddhist account of the five meditation hindrances, or, more specifically, the hindrances to the jhānas (deep states of meditation). The five hindrances (pañca nīvaraṇāni) are sensory desire (greed), ill will (hate), sloth/torpor, restlessness/worry, and doubt (

Keown 2003, p. 198;

Ñanamoli and Bodhi 2009, pp. 35–36). In the Theravada tradition, the five hindrances are connected to the four stages of awakening. Each successive stage of awakening involves an overcoming of specific hindrances or defilements, which include the three poisons (

Ñanamoli and Bodhi 2009, pp. 41–45). Further lists of hindrances can be added. For example, Tibetan Buddhism identifies five hindrances to śamatha practice: laziness, forgetting (the instruction), agitation, dullness, non-application (of a remedy), and over-application (of a remedy) (

Brown 2006, p. 505;

Rinbochay et al. 1983, pp. 52–53). For now, these examples will suffice for gaining an initial understanding of dual conceptions of the hindrances.

What is characteristic of the dual conceptions is that they see the hindrances as something that interferes with or is detrimental to practice and hence should be removed. This is even inherent in the four noble truths of Buddhism: suffering has a cause, and there is a way to end it by removing the cause, which is craving. While specific hindrances may be connected to specific causes (habits, the presence or absence of the object of the hindrance, one’s current mood, etc.), they are ultimately rooted in craving. By removing craving, one will remove the ultimate cause of the three poisons. The basic idea is that one removes hindrances by removing both their specific and underlying causes. Such removal may be conceptualized as different

strategies for dealing with the hindrances. One such strategy is

denourishing, that is, removing oneself from what causes a hindrance, which can cause a hindrance to arise in the future. Generally, such strategies can be understood as a way of

renunciation (

Thera 2013, p. 13).

Removal of a hindrance by removal of the cause is, however, not the only way of removal. There is also the idea of

counteraction. One may understand counteraction in the context of meditation hindrance as based on the notion that one (negative) action is to be met by an equal or stronger but opposed (positive) action. The five hindrances have five corresponding strategies of counteraction (

Wallace 2006;

Yates et al. 2015). For example, sukha, that is, a kind of steady and deep happiness arising through meditation, counteracts restlessness/worry. There are different ways of understanding counteraction as a remedy. One could say that restlessness/worry comes as a result of a lack of happiness. Sukha remedies the lack by adding something where there is nothing. However, restlessness/worry could be said to have a quality in itself, a kind of negative intensity corresponding to the positive intensity of the happiness, which counteracts the negative tendency by an opposite force. Note, however, that the “action” involved in sukha arises from a meditative activity or state and is not in itself necessarily an act; although, some top-down control of happiness may possibly be a kind of “skill” that arises through meditation (

Chenagtsang and Joffe 2018;

Hagerty et al. 2013).

Besides the specific remedies for each hindrance, there are also general remedies or strategies that can be employed. The pattern of the general remedies is the same, regardless of the specific hindrance they are used to alleviate. An example of such a general strategy is the contemplation of the hindrances. This contemplation involves knowing the presence or absence of a hindrance and the conditions for whether it is present or absent (

Anālayo 2018). The awareness or investigation of the hindrances can itself be enough for them to be remedied (

Anālayo 2018, p. 189), or the insight gained through the contemplation can be used to apply more specific remedies.

2.2. Contemporary Dual Conceptions of the Hindrances

We now turn to contemporary meditation handbooks that give an account of different meditation hindrances.

Table 1 lists authors and sources as well as one or more representative definitions of the hindrances from the respective authors. Common to the handbooks treated here is that they draw strongly on the Buddhist tradition. In fact, all of them rely on traditional lists of the hindrances, such as the five hindrances to jhāna described above. Given that the handbooks have a pragmatic perspective, that is, a perspective for which it is important to easily and effectively connect ideas to actual experiences people may have, they often involve very concrete and in-depth descriptions of experiences and sometimes offer innovative models. For example, Culadasa gives an account of when introspective awareness is a support for building concentration and when it becomes a hindrance (

Yates et al. 2015); Burbea provides a perspective on the hindrances as a cycle of reactivity creating a contracted mind, which can be counteracted by creating spaciousness (

Burbea 2014). See

Table 1 for further details (the definitions are highlighted in bold text).

These different definitions of the hindrances offer different perspectives that do not necessarily exclude each other. Indeed, one may combine them into the following definition of meditation hindrances:

The hindrances are contracted, unwholesome, but often useful and sometimes necessary activities, energies, and states of mind that hinder spiritual progress, primarily absorption but also enlightenment, while sometimes being detrimental to our daily life and well-being.

This definition not only includes both the narrow understanding of the hindrances as hindrances to meditation, especially absorption states such as jhāna and samādhi, but also includes the broader understanding of the hindrances as defilements that hinder meditative development more broadly and negatively impact life, for instance, by creating suffering. There is also a tension in this definition, namely between the necessary/useful aspect of the hindrances and the suffering they may create. What is meant by this can be easily seen by considering the hindrance of sensory desire: while sensory desire is useful for ensuring the survival of the organism, it also, by connecting happiness to the devouring of external, impermanent objects, hinders the organism’s ability to enjoy stable, innate or internally and spontaneously generated happiness. In the process of survival, the satisfaction of desire is conditioned upon the presence of desire, a lack. In other words, dissatisfaction is a condition for happiness, and, hence, happiness is not only conditioned but conditioned by its opposite, leading to an infinite cycle of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, which in Buddhism is seen as a cycle of suffering.

Conceived in this way, the hindrances are not a part of the path, but rather obstacles to be dealt with. Even though the hindrances may have survival benefits, they ultimately block the access to absorption and the realization of awakening. Hence, the need for remedies or strategies for dealing with the hindrances. The meditation handbooks quoted in

Table 1 mostly employ dual means. As already mentioned, Culadasa provides an intricate step-by-step procedure for overcoming different hindrances and meditation problems; Brahm discusses different ways of dealing with the traditional five hindrances; Brasington gives advice on how to deal with specific issues (such as the inability to feel pleasure) that hinders access to jhāna; Catherine presents a reformulation of the method of contemplating the hindrances in a way that removes them; Ingram suggests noting as a way of dealing with the hindrances; and Burbea describes a novel way of dealing with the hindrances by creating spaciousness.

The remedies described above all somehow involve an engagement with the hindrances. In addition, as we will discuss later, practices based on bringing awareness to the hindrances, at least to some extent, overlap with non-dual approaches to them. For now, we will understand non-dual approaches to the hindrances as a view based on the notion that “hindrances” do not always hinder development, but may, rather, perhaps counterintuitively, support development. As we will see in the next section, non-dual remedies start with a shift in perspective, viewing something that usually is understood as an impediment to meditative development as an opportunity to practice, perhaps even more effectively.

3. Non-Dual Conceptions of the Hindrances in Theory and Practice

Non-dual perspectives on the world, the mind, and human experience can be found in many different traditions. The natural first reference would be Advaita Vedanta, as “advaita” means “non-dual”, but different Tantric traditions could also be referenced. Perspectives resembling non-dual views may, arguably, be found in Christianity as well. For example, Climacus speaks of “joyful sorrow” (

Climacus 1982, pp. 20–26), and Teresa of Avila describes how, in an ecstatic vision, she experienced pain and love merge (

Sparby 2015). Even the main symbol of Christianity, the cross, signifies both death and resurrection. Furthermore, the stoic view expressed by Marcus Aurelius, where the obstacle becomes the path, can also be understood as a non-dual view. Bear in mind that one may distinguish between (i) non-dual views that see ultimate truth or reality as consisting of an inexpressible, non-differentiated unity and (ii) non-dual views that allow for differentiation within the unity (often a unity of opposites) and a description and symbolization of that unity. Non-dual views of the hindrances that suggest specific practices of transformation for the hindrances tend to be an expression of the latter non-dual view rather than the former. This will be further elaborated on below.

The non-dual conception of the hindrances that we are going to consider here is based on the idea that hindrances on the path of meditative development may be taken as support for progressing on this path. Such a non-dual conception of the hindrances may seem contradictory: something that hinders is at once support. How can a roadblock make traveling more efficient? As we will see, non-dual thinking brings us into territory that does not shy away from contradiction. Some may view it as impossible to explain non-dual ideas with discursive thought. However, there is an idea that also needs to be taken into consideration in this context, namely that a temporary encounter with a hindrance may lead to improvement in the long run. A simple case of this is muscle training. A muscle that is put under strain is weakened temporarily, but the strain and resulting damage to the muscle cause growth and increased strength. In other words, the muscle grows through being exposed to a hindrance, and the same may be the case with meditation hindrances: being exposed to them may result in spiritual growth. After presenting different non-dual conceptions of the hindrances, we will consider to what extent they may be regarded as actually contradictory or whether such ideas as growth through challenge may resolve the contradiction. Below, we will first consider what a non-dual view of the hindrances means from a theoretical perspective, before considering some examples.

3.1. Non-Dual Views of the Hindrances

The idea of non-duality in the context of spiritual practice generally consists of rejecting dualism and affirming that absolute reality is a whole beyond distinctions, a whole within which there is a “confluence of opposites” or no conceptual distinctions at all (

Feuersten 1998;

Loy and Potter 1991;

Sparby 2015;

Törzsök 2014). Since non-dual reality is supposed to be beyond negation and affirmation but is still conceived of as in opposition to something (e.g., dual frameworks), non-dual conceptions easily seem contradictory. A response to this is to regard the idea of non-duality as non-conceptual, that is, as something that perhaps can be intuited or experienced but never adequately presented within a discursive conceptual structure that relies on affirmation and negation as means of determination (

Sparby 2014).

However, while non-duality may be regarded as transcending conceptuality and linguistic expression, it often still has an impact on how phenomena are conceived and expressed in language. In the context of meditation hindrances, non-dual frameworks result, as we will see through the presentation below, in a series of perhaps surprising, counter-intuitive, or even contradictory statements:

The root of the hindrances can be found in ultimate reality itself;

The hindrances are ultimately not separate from their opposites;

The hindrances are means of removing the hindrances.

That the root of the hindrances may be found in ultimate reality itself may seem counter-intuitive, insofar as ultimate reality is seen as pristine, perfectly good, and eternally free from suffering. If the main aim of Buddhism is the end of suffering, and suffering is achieved by realizing ultimate reality, but ultimate reality itself is the root of suffering, how can suffering cease when ultimate reality is realized? If we remove the weeds, but their roots are left intact, then they are only removed temporarily at best. Indeed, according to the traditional view (expressed for instance in the list of the twelve causes), ignorance or delusion—avidyā—is the original cause of the chain that leads to and sustains suffering. However, if we try to think according to the principle of non-duality, delusion cannot ultimately be separate from the whole. Hence, for example, in Bön non-dual thought, we will encounter statements such as: “To perceive delusion and nondelusion as separate is fundamentally deluded” (

Klein and Wangyal 2006, p. 94); “The very essence of delusion (‘khrul ba) and nondelusion is one” (

Klein and Wangyal 2006, p. 120); delusion is “part of [the] dynamic display” (

Klein and Wangyal 2006, p. 109) of wisdom. Furthermore, “delusion arises from and within unbounded wholeness” (

Klein and Wangyal 2006, p. 96). If we take “nirvana”, awakening, realization, or enlightenment to mean ultimate reality, we find views in Buddhism where ultimate reality is not separate from the hindrances:

Desire is said to be nirvana; habit, hatred, and ignorance likewise.

These very realizations are the very way the realized mind stays.

There is no duality between realization and attachment.

While ultimate reality is not separate from delusion, hate, attachment, etc., such views do not necessarily imply that any feeling of hate, any attachment one has, is identical to ultimate reality, so that the realization of ultimate reality would mean to have this or that specific experience of hate or any other hindrance. Rather, the hindrances arise within ultimate reality and are connected with it in such a way that they may be used to bring a practitioner closer to a purer experience of it.

There are two ways of understanding what this means more specifically, namely (i) that the hindrances and ultimate reality are one in a way that we cannot conceptualize and, hence, we cannot be expected to make sense of how ultimate reality is not separate from the hindrances or (ii) that the hindrances are a “dynamic display” of ultimate reality where each plays a specific role as means of realization (e.g., the experience of hate becomes a condition for renouncing hate). These interpretations may indeed be regarded as complementary. We can affirm that the way the hindrances are a part of ultimate reality cannot, in the final analysis, be explained conceptually (or if we understand this ontologically, on the fundamental level, ultimate reality and the hindrances are simply one). However, we can also add that ultimate reality manifests dynamically, and that through the manifestation, good and bad qualities, virtues and hindrances, appear as separate. One idea from Tibetan Buddhism is that

rigpa, or ultimate reality, manifests as light, a light that is differentiated into five colors. These colors—white, yellow, red, green, and blue—correspond to both the five wisdoms and the five poisons:

We have these five emotions within the five wisdoms. This is taught in Vajrayana Buddhism in general and Dzogchen in particular. Whenever we have ignorance, it is in the nature of dharmadhatu wisdom. When we have aggression or irritation, that exists in the nature of mirrorlike wisdom. When we have pride, that nature of mind exists in the wisdom of equanimity. When we have passion, desire, or attachment, that mind exists in the nature of discriminating wisdom. When we have jealousy or envy, it exists in the nature of all-accomplishing wisdom. Therefore, these five poisons remain in the five wisdoms of buddha.

Not only does each hindrance have a corresponding wisdom, but the hindrance also exists within or at least in relation to wisdom. In the words of Maitripa: “The afflictions are the great wisdom. Like wind to forest fires, they are a yogin’s aid”. (

Kunga Tenzin 2020, p. 317). This is elaborated by the third Khamtrul Rinpoche: “The wisdoms will not be found anywhere apart from the five poisons, which will be freed in their original condition”. (

Kunga Tenzin 2020, p. 317). Citing scripture, the third Khamtrul points out that the poisons purify themselves by themselves, that is, desire purifies desire—desire does not only burn, it can be purified further and reveal its true nature when it is allowed to burn purely, that is, when it is not satisfied by conventional means but is rather allowed to burn the one burning supported by the means of non-dual practice:

As said in

Two Segments:

Just as those boiled by boiling

And further heated up by fire,

Those burned by the fire of desire

Will be further burned by the fire of desire.

In the

Samputa Tantra, it is said:

Desire purifies desire.

Hatred cleanses hatred.

Dullness cleanses dullness.

Pride cleanses pride.

Envy cleanses envy.

Vajra holders cleanse everything.

Hence, the hindrances do not need to be renounced. At most, they need to be guided. For example, desire needs to burn in the right way, that is, not by seeking external satisfaction but by being turned towards itself and the one seeking satisfaction. If so, both will burn up, purification will ensue, and the opposite quality will arise. This is similar to the idea, also found in Tibetan Buddhism, that desire, hatred, and ignorance can be converted to and essentially are, respectively, bliss, radiance, and awareness (

Rinpoche et al. 1991, p. 273).

The idea that the hindrances are not disconnected from ultimate reality, that the hindrances may even be connected to the good qualities of ultimate reality, lays the ground for using the hindrances as the path. A practitioner using the hindrances as the path “is like the peacock and other birds that extract the essential nutrient of the poison itself and turn it into the most nourishing food” (

Kunga Tenzin 2014, p. 106). Not only do the adversities of the path become “spiritual friends” (

Kunga Tenzin 2014, p. 124), they become means through which one may

enhance practice (

Rinpoche 2003, p. 121). All hindrances that appear on the path can potentially be used as a means for progress, which has already radically altered the meaning of a hindrance to the path. However, there is a natural consequence of this view, namely that one may

produce what is normally considered a hindrance or

increase a hindrance that is already present, in order to advance even more rapidly. An example of this would be tummo, a practice through which desire is produced in order to utilize it. This practice will be described more in-depth below.

3.2. Examples of Non-Dual Practice

We have now established a non-dual view of the hindrances and investigated the idea of using them as means of progressing on the path. How does a practitioner proceed when utilizing them in this way? To answer this, we will start with Mahamudra, which in a certain way stands closer to dual approaches in comparison to more non-dual approaches such as tummo, karmamudra, and chöd, which we consider next.

3.2.1. Non-Dual Practice in Mahamudra

Mahamudra in the sense that we use the term here refers to a system of meditation that includes śamatha, vipaśyanā, and open awareness-practices sometimes called one-taste or non-meditation. Mahamudra also contains instructions for utilizing all phenomena as part of the path. Utilizing the hindrances can be seen as a special case of utilizing whatever is going on in experience as a means for realization. This general practice of utilizing all phenomena is described in the following way:

No matter how it appears, relax loosely right on it. Avoid tainting it with hopes for good experiences and fear of bad ones. No matter what appears, apply the central practice on that itself. Uninterrupted by any other thought, in that state rest loosely and at ease. Resting in this way, you do not need to block appearances, try to accomplish emptiness, or search elsewhere for an antidote. A vivid union of the inanimate object and awareness is what is called “using phenomena as the path”, “merging phenomena and mind into one”, and “seeing the essence of indivisibility”. By doing so you are capturing the key point of practice.

The main idea here is to rest on the phenomena themselves without reactivity (fear, hope, blocking, etc.). Utilizing the hindrances essentially consists of the same approach:

[…] be convinced that all five poisons—strong and weak—that have been recognized are the radiance of mind essence, innately endowed from primordial beginning with the unoriginated dharmakaya. They appear different only temporarily because ultimately they do not exist as separate nor as good and bad; so by nature they are equal and non-dual. Therefore, don’t block or pursue, reject or adopt, manipulate or do anything whatsoever. Simply do not be carried away but rest on them, sustaining the practice by relying on mindfulness. That is to say, in the case of aggression, maintain mindfulness right on that aggression; if there is passion, maintain mindfulness on the attachment itself; when dull, maintain mindfulness on that state of dullness; if jealous, maintain mindfulness on that jealousy; when proud, maintain mindfulness on that pride. In brief, equalizing them right on mindfulness as having one taste, you should use all five poisons […] as the path, neither giving the coarse ones free rein nor leaving the subtle ones dormant.

This practice starts with a non-reactive attitude towards the hindrances/poisons. Then, one rests on them directly, without doing anything (other than maintaining the practice through mindfulness and stopping all kinds of reactivity). Rather than avoiding the hindrances, one uses them as a part of the path, developing not only equanimity but also insight “by thoroughly knowing the nature of whatever arises” and “fully knowing the nature of the undesirable is the way in which this becomes among all paths the supreme” (

Kunga Tenzin 2014, p. 106). In other words, this way of approaching hindrances resembles the strategy of contemplating the hindrances, although one does not set out to analyze under what conditions they appear and disappear so as to learn how to renounce them. There are certain Mahamudra instructions where one is encouraged to “try to create a more intense emotion by bringing to mind something even more provocative than the previous objects, such as the objects of attachment or anger” (

Namgyal 2001, p. 73). While directly resting on a hindrance may be understood as a non-dual approach, intentionally creating a hindrance energy is even more radically non-dual.

3.2.2. Non-Dual Tantric Practice: The Case of the Six Yogas or Tummo and Karmamudra

The concept of “tantra” is many-faceted (

Feuersten 1998;

Yeshe 1996), and we cannot possibly try to define it exhaustively here. Rather, we will focus on two practices that are commonly accepted to be a part of Tibetan Buddhism, namely the practices of tummo and karmamudra, both of which are connected to the tantric tradition (

Kozhevnikov et al. 2013;

Mullin 2005;

Yeshe 1998). Tummo and karmamudra are parts of the so-called six yogas, a set of practices that can be led back to the the Buddhist monk Tilopa (

Mullin 2006, p. 7), which are commonly referred to as the Six Yogas of Naropa (Naropa being Tilopa’s chief disciple). There are different ways of accounting for which practices constitute the six yogas, but a common list (used by Tsongkhapa) is the following: 1. inner heat (tummo); 2. illusory body; 3. clear light; 4. consciousness transference; 5. forceful projection; and 6. Bardo yoga (

Mullin 2005, p. 29). We cannot, due to reasons of space, give an account of all these practices. The general idea is that a practitioner makes use of a set of exercises, such as vase breathing, visualizations, and mantras to access and influence the deeper aspects of consciousness, which speeds up the process of awakening. More specifically, these practices are seen to influence the subtle energetic system of the human being in such a way that the hindrances are dissolved, and the winds or subtle energies enter the central channel, which gives rise to the clear light of the most subtle mind, which can be accessed first in the sleep state and then at the time of death. The practices of tummo (inner heat) and karmamudra/action mudra (sexual union) are of interest here, since they represent a specific non-dual approach to the hindrance of desire. Here is how the non-dual view of the hindrances is explained by Lama Yeshe, when introducing tummo:

Energies and states of mind that are considered negative and antithetical to spiritual growth according to other religious paths are transformed by the alchemy of tantra into forces aiding one’s inner development. Chief among these is the energy of desire. According to the fundamental teachings of Sutrayana, desirous attachment only serves to perpetuate the sufferings of samsara: the vicious circle of uncontrolled life and death, born from ignorance and fraught with dissatisfaction, within which unenlightened beings trap themselves. Therefore, if one truly wishes to be free from this samsaric cycle of misery, it is necessary to eliminate the poison of desirous attachment from one’s heart and mind completely. While the Tantrayana agrees that ultimately all such ignorantly generated desires must be overcome if freedom and enlightenment are to be achieved, it recognizes the tremendous energy underlying this desire as an indispensable resource that can, with skill and training, be utilized so that it empowers rather than interferes with one’s spiritual development.

The non-dual view here consists of seeing what is normally considered a detriment to “spiritual growth” as an aid to such growth. However, it is still affirmed that desire and attachment are to be overcome. In other words, the non-dual view relates to the means rather than the end—what usually stops the end from being reached becomes the means for reaching the end. It is not the desire for sensory pleasure that is to be increased (

Yeshe 1998, p. 100); rather, one aims for a transformation of the energetic system of the human body in such a way that it gives rise to pure, spontaneous bliss without any physical object. The bliss becomes the basis for recognizing non-duality everywhere (

Yeshe 1998, p. 146), in all experiences, transforming desire into wisdom, while purifying sensory desire and other hindrances such as delusion and unrest (

Yeshe 1998, pp. 133, 144).

The practice consists of a series of preliminary exercises, including deity yoga, hatha yoga, energetic cleansing, visualizations, and prayer. These practices are supported by vase breathing, which is a practice that involves conscious inhalation/exhalation, breath-holding, visualizations, swallowing saliva, etc. Through these practices, one is said to gain control of the subtle energies and the experience of bliss. The main practice is based on visualizations and the focusing on a vowel at a point below the navel (

Yeshe 1998, pp. 143, 146), sometimes called the navel chakra. The practice will create inner heat and bliss, which is fueled by pleasure and desire, in relation to the objects of the senses and the physical body (

Yeshe 1998, p. 182). For example, the visualization includes creating an image of the deity Vajradhara in sexual union with his consort (

Yeshe 1998, p. 59); focusing on other chakras, including the “secret chakra” of the sexual organs, will produce different forms of intense pleasure (

Yeshe 1998, p. 150).

Gradually, the energetic system will be opened, the energies will enter into the spine, and a simulation of the death process will take place. This process is supported by other practices of the six yogas and culminates in the experience of clear light. The practice of karmamudra, physical sexual union, will increase the sense of bliss and may also be regarded as essential for achieving awakening before the moment of death. Consort practice will make the energies go into the spine more filly and to achieve “total realization of non-duality” (

Yeshe 1998, p. 164). One explanation of how these kinds of practices work is that they loosen the knots existing around the central channel (each knot being related to either the hindrance of desire or hate), so that the subtle energies may flow completely into the central channel. Through karmamudra, the energies enter the central channel more strongly, which “enables us to loosen completely the knots at the heart channel wheel” (

Gyatso 2002).

Note that it is misleading to regard these practices simply as increasing desire. Rather, they are based around developing the ability to generate bliss without any external object and then combining that bliss with emptiness or an understanding of non-duality. “Desire” may indeed be used synonymously with “bliss” (

Mullin 2006, p. 65) and pleasure (

Yeshe 1998, p. 182). The reason for why these terms may be used interchangeably may be understood by considering the idea of self-generated bliss, where the fulfillment of desire is not dependent on external circumstances, but, rather, it happens automatically or internally, making the increase in desire equal to the increase in pleasure or bliss.

It is sometimes noted that tummo and related practices can be dangerous, a warning that should be taken seriously considering such phenomena as “kundalini syndrome” (

Benning et al. 2019;

Valanciute and Thampy 2011) and other related potentially challenging energetic experiences (

Lindahl 2017). Furthermore, it may be the case that these practices involve the “danger” of increased “ordinary physical desire”, which then would be detrimental to spiritual progress (

Yeshe 1998, p. 148). In other words, the dual and non-dual perspectives often go hand-in-hand, as in this case, where ordinary physical desire in and of itself is viewed as something negative, while desire in itself is view as a part of the process of awakening.

3.2.3. Chöd

Chöd is a non-dual practice that is perhaps most well-known for the ritual of offering one’s body as food for demons. Developed by Machig Labdrön (1055–1149), chöd is a practice that directly approaches hindrances, in the form of different demons, in an attempt to uncover and cut them at their roots—not so that they disappear but so that they are transformed into helpers and forces that support rather than hinder progress. The ritual of chöd involves inviting six inner and outer demons or forces: (1) demons of anger, (2) the forces of afflictions or hindrances that create illness, (3) the forces that interfere with one’s merit and spiritual practice, (4) the forces of negative karma that cause rebirth through self-clinging, (5) the demons that cause identification with the physical body, and (6) the demons of fearful places in nature. In addition, one’s current parents are invited, who represent all beings that have been one’s parents in previous lives (

Edou 1996, pp. 40–41). These beings are transformed through compassion and offering one’s body.

A chöd practitioner “does not guard against mental afflictions such as attachment, hatred, fear, etc. by retreating from worldly life, but goes out to meet, head-on, the objects (Tib.

yul) and circumstances that provoke terror or bodily attachment” (

Edou 1996, p. 47). The process includes transferring one’s consciousness to spiritual beings such

vajrayogini, transforming one’s body into nectar and offering it to different deities and demons. All of this supports the realization of compassion and emptiness of self.

The practice of chöd is said to be reserved for very advanced practitioners (

Edou 1996, p. 55), however, it may be also be seen as widespread. Tsultrim Allione has developed a practice inspired by chöd, which is less advanced (

Allione 2008, p. 9). The practice consists of five steps, which can be summarized like this: (1) locating the hindrance/demon in the body; (2) visualizing the demon and asking it what it needs; (3) identifying with the demon; (4) visualizing that one’s body dissolved into nectar and feeding the demon with it (which might transform into an ally); and (5) resting in awareness. Central to this approach is a shift in how one views difficulties:

[…] we can see them either as obstacles or grist for the mill that has potential to bring us closer to awakening. Without these challenges and without recognizing our faults, we would spend our lives waiting for ideal circumstances instead of genuinely working on ourselves. In fact, our “enemies”, those who bring up the most in us, are our greatest teachers, and instead of seeing them as demons we could see them as gifts. […] Fears obsessions, and addictions are all parts of ourselves that have become “demonic” by being split off, disowned, and fought against. When we try to flee from our demons, they pursue us. By struggling with them as formless forces, we give them strength and may even succumb to them completely. […] We need to give our demons form and to give voice to those parts of ourselves that we feel persecuted by. Engaging with them, we can get at the source of the behaviors and transform that energy into an ally. That does not mean we indulge in destructive actions, but that we acknowledge the underlying needs. The practice of feeding the demons makes this transformation possible.

As Allione claims, difficulties may be viewed as useful material, so personifying the hindrances as demons, interacting with them, etc., may enable us to uncover their roots, freeing and transforming their underlying energies. The idea that the hindrances may become allies may be understood as a concrete example of how what stands in the way becomes the way.

4. Discussion

We may summarize the distinction between dual and non-dual approaches to meditation hindrances like this: dual and non-dual views differ in that the former sees the hindrances as detrimental to spiritual progress, while the latter understands that the hindrances may be utilized for spiritual progress. In Early Buddhism/Theravada, spiritual progress can be defined as the removal of hindrances/defilements, while non-dual views may define awakening as the realization that the hindrances and their opposites are not ultimately distinct.

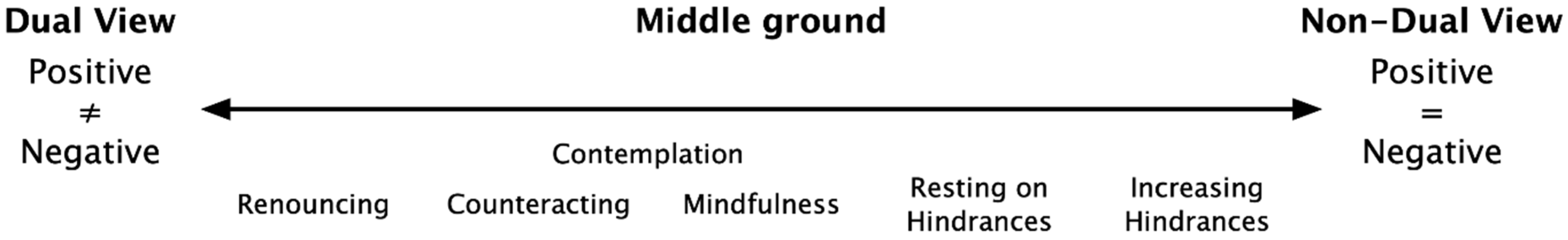

However, systems that are open to non-dual methods still tend to include dual approaches. For example, in Mahamudra, the hindrances can be taken as the path, but one also seeks to abandon laziness, agitation, etc. Hence, dual and non-dual approaches do not exclude each other. Indeed, dual and non-dual approaches can be seen to be existing on a scale, with a distinction between:

Dual approaches that

seek to remove the hindrances through renunciation, cutting them at the roots, etc.;

seek to counteract the hindrances through developing opposing qualities;

seek to develop insight based on contemplation of the hindrances.

Non-dual approaches that

See

Figure 1 for an illustration of this way of categorizing the different approaches.

One could theoretically add an extreme dual view to this categorization, which would view the hindrances as having no value at all under no circumstances. For example, “desire” in all shape or forms should be abandoned, even the desire for awakening. The result would be a complete lack of motivation. Similarly, “hate” in all shapes and forms should be abandoned. This would result in a total, non-discriminatory acceptance of all that is. At the opposite end of the scale, one could add an extreme non-dual view, for which there is no reason to do anything at all, since everything is always already perfect. As should be easy to see, the dual and non-dual view converge, as they are formulated in their extreme versions, at least when it comes to practical and behavioral consequences.

One can also conceive of a neutral space between dual and non-dual approaches, where hindrances are neither sought to be removed nor included in the practice. This could be seen as the view typical of mindfulness and similar forms of meditation, which does not approach hindrances head-on but, rather, seeks to cultivate a non-judgmental attitude (

Lutz et al. 2015). To the extent that this is understood as a way of abandoning the hindrances by noticing and releasing them (

Armstrong 2021, p. 52), which may be counted as two fundamental meditative activities (

Sparby and Sacchet 2022), it tends toward being a dual approach. To the extent that encountering the hindrances is seen as necessary for developing mindfulness, it tends towards a non-dual approach.

While dual and non-dual approaches differ in their view of whether the hindrances may or should be utilized, they agree that the hindrances should be overcome. For the dual approach, this means that hindrances should disappear once and for all, while for the non-dual approach, it can mean either that the hindrances are overcome, that their energies are utilized, that they are transformed into their beneficial counterparts, or that one realizes that the hindrances and their opposites are ultimately not distinct. The dual and non-dual approaches can also be combined, as in chöd, where the evocation of the hindrances is indeed a part of cutting them at their roots. First, one invites, for example, the demons of anger, one seeks out the object that creates attachment to the body, and then one works on transforming the afflictions through compassion. In other words, dual and non-dual views do not contradict each other when it comes to their common aim, but they differ with regard to their view of how the aim is to be realized and what its realization may look like. Still, when considering the actual, behavioral, or expressive consequences, they indeed might be similar. For a dual realization of the removal of anger, there would be no anger; for a non-dual realization, the removal of anger could include the display of anger but in a way that is not distinct from clarity, which does not involve suffering and, hence, involves no real anger.

Some potential advantages and disadvantages can be gleaned when considering dual and non-dual approaches to the hindrances. These are listed in

Table 2 below.

How strongly each approach may represent an advantage or a drawback relates to the kind of dual/non-dual approach in question. For example, resting on a hindrance is less likely to lead to an increase in it than actively bringing it forth through tummo. Conversely, if one does not increase the hindrance energy, as in tummo, it is less likely that one may utilize the energy inherent in it. For reasons of space, we will not go through all possible versions of dual and non-dual approaches in relation to the advantages/drawbacks. Suffice it to say that some advantages/drawbacks may apply to some non-dual approaches while not, or to a lesser degree, to others.

Whether one takes a more dual or non-dual view of the hindrances may have consequences for one’s view of awakening. Non-dual awakening models may be more likely to include the potential for the experience, or at least the expression of hindrance-energies by awakened human beings, while dual models are likely to reject that awakened beings can experience or express those emotions that are counted as hindrances (

Anālayo 2020). A potential middle ground can be found in the following view: what goes away through awakening is the reactivity to the hindrances, combined with a skillful and wise approach to both removing the detrimental aspects of the hindrances in oneself and others, while also being able to utilize them for oneself and others.

Much research remains when it comes to determining which approaches are most effective, for which persons, and in which situations. Such research can also hardly progress without clear views of what spiritual development means. Still, research from psychology can be very useful in such a context, for example, in relation to whether the expression of anger leads to an overall reduction or increase of anger. Similarly, research into therapeutic processes that involve exposure to difficult situations may also be useful, especially insofar as how such research can help someone make an informed decision about when the intentional increase of a hindrance is both safe and effective. One can only hope that the research on contemplative processes will reach the same level of rigor as seen in the field of clinical research, while maintaining the awareness that contemplative development can be highly individual and also challenge accepted norms about what counts as good and bad or harmful and useful. While non-dual approaches may be especially effective, they are also seen as potentially unsafe. One could, however, also argue that dual practices are in a sense “unsafe” or at least that they create their own set of complications, by creating tension and anxiety in relation to the attempt at eliminating the hindrances. To uncover which ways of practice are both safe and effective, further research is needed, not only into what is potentially safe and not harmful but also into what such terms mean within the context of spiritual practice.

We may now return to the issue of subjective (unpleasant, etc.) and objective (harmful, etc.) negative effects raised in the introduction. Approaching or even increasing subjectively aversive emotions (fear, hate, disgust, etc.) and unpleasant sensations may be a part of a non-dual method that is objectively good in the sense of having functional value and in the sense of leading to spiritual progress. Approach/increase strategies may, however, be problematic, if they lead to trauma (

Treleaven 2018) or an overall increase of the hindrance. Sympathetic but sometimes problematic emotions, such as desire, may also be cultivated by some non-dual practices, can have functional value, and can lead to progress, but may also be harmful in cases of “kundalini syndrome” or when there is an overall increase of the hindrance. Practitioners, meditation teachers, researchers, and clinicians would do well to be informed about the complexities of these issues.