Abstract

A growing corpus of literature has explored the influence of religion on economic attitudes and behavior. The present paper investigates the effect of religion on labor market performance using a novel approach to control for the endogeneity of religion. It proposes contingency experience, individual experiences of existential insecurity, as an instrumental variable of a person’s religiosity. The empirical analysis uses data from a household survey in South Africa specifically designed for this study. The econometric approach is the estimation of instrumental variable ordered probit and linear probability models. Using the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS), the analysis differentiates between effects of individual religious intensity and of religious affiliation. The findings show that individual religiosity, measured in the CRS, has a robust and positive effect on labor market performance. Religious affiliation does not seem to affect labor market performance. The positive effect on religiosity is documented in a set of ordered and binary outcome models across different indicators of labor market performance. The study concludes that the intensity of belief exerts an influence on labor market attitudes and outcomes, while affiliation in religious communities (indicating different content of belief) does not seem to make a difference.

1. Introduction

The most prominent study on the influence of religion on economic attitudes and outcomes is Max Weber's The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Weber [1920] 1958). Weber argued that the Protestant Reformation produced so decisive a shift in individual economic attitudes that it caused the emergence of capitalist economic thinking. Since its first publication in 1904, Weber’s hypothesis has received widespread attention from various academic disciplines, albeit without unanimous conclusions regarding its validity (Basten and Betz 2013; Becker and Woessmann 2009; Cantoni 2015). Already, Weber’s original study was a reaction to the Marxist school of dialectic materialism, which considered religion to be part of a social superstructure that inhibited social and economic progress (Marx [1843] 1972). The common assumption of both schools of thought is that religion does play an important role in shaping individual attitudes and motivations.

Recently, economic research has increasingly (re-)recognized religion as a potential determinant of economic attitudes and outcomes (Barro and McCleary 2003; Chen and Hungerman 2014; Guiso et al. 2003). Thus far, the results do not provide general answers (Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf 2011). What seems to emerge is that religious beliefs influence attitudes and economic performance in ambiguous ways. The directions and magnitudes of the effects of religion on individual mindsets and actions in the economic realm depend on the religious community in question and, importantly, the social, economic, political, and cultural context. Moreover, central methodological issues remain unresolved. The first issue is the identification of causal effects, due to the potential endogeneity of religion (Benjamin et al. 2016). Ex ante attitudes might drive both individual religiosity and labor market performance (cf. Iannaccone 1998), or economic success might affect religious behavior (Buser 2015). Since experimental approaches are seldom feasible,1 instrumental variable approaches are frequently used to control for bias due to omitted variables and reverse causality (Beck and Gundersen 2016; Cornelissen and Jirjahn 2012; Gruber 2005). The challenge is finding adequate instruments correlated with religiosity but uncorrelated with economic outcomes. Second, most research relies on religious affiliation as the sole indicator of religion. More sophisticated and multidimensional measures might improve our understanding of the interaction of religion and economics (Lehrer 2009). Third, there is a substantial gap when it comes to evidence from developing and transforming economies, even though religion often plays a more prominent role in these contexts in private and public life than in developed countries (Selinger 2004). Thus far, most of the research on economics and religion has focused on the United States and, to a lesser extent, Europe (Beck and Gundersen 2016). Fourth, it is not clear through which mechanisms religion transmits to economic attitudes and behavior (De Jong 2011).

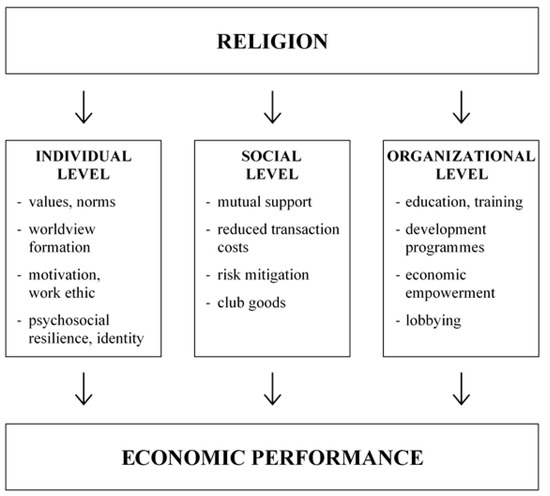

From a conceptual perspective, the transmission mechanisms from religion to economic outcomes can be related to three levels: the individual, the social, and the institutional (Figure 1). At the individual level, which is the focus of this article, religion transmits to economic outcomes through changed attitudes (Audretsch et al. 2013; Berger 2010; Brañas-Garza et al. 2009; Dickow 2012; Freeman 2012; Guiso et al. 2003; Heuser 2013; Kirchmaier et al. 2018; Mafuta 2010; Meyer 2004). Religion influences motivations and work ethic, leading to economically conducive behavior affecting, for example, labor market performance. Essentially, this relates to Weber’s ([1920] 1958) hypothesis of the Protestant ethic. Weber argued that, in early modern Protestantism, the economically favorable doctrines of “calling,” “predestination,” and “inner-worldly asceticism” transformed into behavioral patterns that promoted the development of the capitalist economy. A crucial (but often overlooked) point in the Protestant ethic hypothesis is that the prerequisite for the changes in mindsets and behavior brought about by the Reformation was an increase in religiosity (Schilling 2016). As Weber ([1920] 1958) pointed out:

Figure 1.

Transmission mechanisms from religion to economic outcomes. Note—Author’s elaboration based on Haynes (2009) and Öhlmann et al. (2016). While the separation of the three dimensions is a useful analytical tool, it should be noted that the three dimensions are intertwined in practice and in the self-understanding of most religious communities.

“The Reformation meant not the elimination of the Church’s control over everyday life, but rather […] the repudiation of a control which was very lax, at that time scarcely perceptible in practice and hardly more than formal, in favour of a regulation of the whole conduct which, penetrating to all departments of private and public life was infinitely burdensome and earnestly enforced. […] And what the reformers complained of in those areas of high economic development was not too much supervision of life on the part of the church, but too little.”

Hence, when using Weber’s theory to undergird empirical work, the degree of religiosity must be considered in addition to specific theological tenets. Eisenstadt’s (1968) notion of the “transformative capacity” of religion provides a generalization of the Protestant ethic applicable to other religious contexts.

In addition to fostering work ethic, religion has a psychosocial support function. Religion can provide identity and increase resilience against adverse shocks (e.g., Cross et al. 1993; Masondo 2013, 2014), which is particularly relevant in developing country contexts marked by high social dynamics, risk, and adversity. Religion becomes a coping mechanism for adversity and contingencies (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005; Pargament 1997).2

The social level refers to social capital. Religious networks constitute social capital resources (Öhlmann et al. 2016; Swart 2017). These networks can be used for economic improvement and can facilitate collective action (Woolcock 1998). First, religious networking reduces transaction costs. Cross et al. (1993) showed that religious communities constitute sources of labor-market-related information. Second, they are mutual support groups for economic activities (Oosthuizen 1997; Schlemmer 2008). Third, they have an insurance function and serve as a form of risk mitigation (Dehejia et al. 2007). Religious communities constitute support groups in case of adverse shocks. Fourth, they provide implicit club goods, such as the reputation of being reliable and hard-working (Freeman 2012; Mafuta 2010; Turner 1980). At the institutional level, religious communities are important providers of social services. They provide healthcare, education, training, and development programs (Bengtsson 2013; Coleman 1988; Gifford 2015; Öhlmann et al. 2016). Moreover, religious communities lobby in the interests of their members and the wider communities (Bompani 2010; Thomsen 2017).

This paper approaches the relationship of religion and economic attitudes and actions by investigating the effect of religion on labor market performance in South Africa. A household survey was conducted for the specific purpose of this study, enabling us to address shortcomings in the existing literature. First, this study uses a novel method to account for potential endogeneity of religion. I propose that a person’s contingency experiences (Lübbe 2004; Luhmann 1982)—that is, experiences of “existential insecurity” (Norris and Inglehart 2011), such as natural catastrophes and death—constitute relevant and valid instruments for religiosity. Recent research has shown that experience of contingencies is one of the factors affecting religiosity and religion is a means of coping with these experiences (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005; Bentzen 2019, 2020; Pargament 2012; Zapata 2018). In the econometric approach, I use contingency experiences as an exogenous variable that produces a variation in the level of individual religiosity (see Section 5.2 for a comprehensive discussion).3 This assumption seems particularly justified in the context of South Africa, in which religious worldviews are salient in society (see Section 3).

Second, this study is the first to employ the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS, Huber 2003; Huber and Huber 2012) in an economic study of religion and economic performance at the microeconomic level. Using the CRS allows us to elucidate the individual-level transmission mechanisms of religion to labor market performance. Conceptually sub-dividing individual religiosity into content (“what you believe”) and the intensity of belief (“how much”), I differentiate between the effect of specific religious tenets and individual religiosity.4 Third, this study uses cross-sectional data from South Africa, providing evidence from a developing country context.

South Africa is an ideal case study setting due to its highly dynamic religious landscape, particularly within the Christian faith. Research in theology and sociology of religion holds the belief systems of various religious communities in South Africa to be conducive to individual economic outcomes. There is particularly strong support for this relationship in the case of so-called African Independent and Pentecostal–Charismatic churches. In what Anderson (2001) termed “African Reformation,” these churches grew from marginal to majority religion in South Africa (and many other African countries) during the twentieth century (Öhlmann et al. 2016). They foster an intensive religiosity. Religion becomes a major determinant of attitudes and actions in the economic realm (Freeman 2012; Turner 1980). This resonates with the Protestant ethic hypothesis by Weber (Berger 2010; Schilling 2016; Weber [1920] 1958).

Moreover, the determinants of labor market performance in South Africa remain of crucial concern. Unemployment in the economically active population is at 26.7%. Including discouraged jobseekers, the figure rises to 36.3% (Statistics South Africa 2018). Particularly in rural areas and for youth, the figures are even higher. While the living conditions of the majority have improved since the end of apartheid in 1994, over 55% of the South African population lives below the poverty line of the equivalent of USD 725 per month (Statistics South Africa 2017). Inequality continues to be among the highest worldwide (World Bank 2018). In this context, factors contributing to individual labor market success are particularly relevant. Can religion be considered one of these factors?

Research from economics, social sciences, and humanities argues that religion influences economic outcomes in various ways. Following most of the economic research in the field, this study focuses on two different aspects within the dimension of individual religiosity. First, I analyze the effect of different theological tenets and practices by including indicator variables for categories of churches and the practice of African traditional religion. Second, I investigate the effect of generic religiosity (i.e., religious intensity) by employing the Centrality of Religiosity Scale as an explanatory variable. My empirical approach is the estimation of instrumental variable ordered probit and linear probability models of different labor market outcomes (looking for work, working in the informal sector, and working in the formal sector) using data from 1086 working-age individuals in four South African provinces.

Our findings confirm parts of the Weberian hypothesis and findings from sociology of religion, anthropology, and theology on religion in developing countries. The results show that individual religiosity positively affects labor market performance at various levels. This effect seems to be due to (generic) religiosity and not to specific or particular religious communities. No robust effect of affiliation to specific Christian churches is identified, indicating that differences in religious tenets do not make a difference. The results are robust across different specifications.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of recent economic research on micro-level religion and economic outcomes and attitudes. Section 3 introduces the economic and religious context of this study, while Section 4 describes the data and key analytical concepts. The empirical strategy is outlined in Section 5, followed by the results in Section 6. I discuss the findings and their implications in Section 7, followed by a brief conclusion in; Section 8.

2. Literature

2.1. Religion and Labor Market Outcomes

Economic research on religion and economic performance can be categorized into macroeconomic (e.g., Barro and McCleary 2003; Mangeloja 2005; McCleary and Barro 2006; Noland 2005) and microeconomic studies (e.g., Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf 2010; Guiso et al. 2003). An interesting special case is historical studies investigating the validity of the Weber hypothesis and exploiting differences between historically Protestant and Catholic regions in Europe (e.g., Basten and Betz 2013; Becker and Woessmann 2009, 2013; Cantoni 2015; Spenkuch 2017). In line with the approach of this paper, the focus of this literature review is on economic studies investigating micro-level effects of religion on labor-market-related variables.

With respect to religion and income in the US, Steen (2004) found that “both men raised as Catholics and men raised as Jews have higher earnings” in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 Cohort. In a similar vein, in their analysis of the 2000/2001 National Jewish Population Survey, Chiswick and Huang (2008) found that, for Jewish men, “religious involvement is associated with more favorable labor market outcomes,” but “beyond some point religious practice has a negative effect.” Beck (2016) analyzed data from the 2005 Panel Study of Income Dynamics in a quantile regression approach, identifying positive associations of religious participation and income among Protestant and Catholic men, while for Catholic women, lower participation goes along with higher wages. The three studies by Steen (2004), Chiswick and Huang (2008), and Beck (2016) control for various observable characteristics in their human capital earnings regressions but do not control for potential endogeneity due to selection on unobservable characteristics or simultaneity. Their results “should thus be interpreted as descriptive rather than causal,” as Beck (2016) pointed out. Gruber (2005) proposed to use religious market density (i.e., the population share in a region affiliated with one’s religion) as an instrument for religious participation. Using the General Social Survey and census data from the US, he found religious participation to have a positive effect on income and several other economic indicators.

Arano and Blair (2008) considered the relationship between religion and income to be bicausal. Using household survey data from the state of Mississippi, they found that religious intensity increases with income and vice versa. They use a simultaneous equation framework to account for the endogeneity of religious intensity with respect to income and the endogeneity of income with respect to religious intensity. While their simultaneous equation approach is similar to the econometric framework of the state-level macroeconomic study by Lipford and Tollison (2003), the results diverge. Lipford and Tollison (2003) found that religious participation decreases labor supply and thus negatively affects state-level per capita income in the US. A simultaneous equation framework is also employed by Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf (2011) in their analysis of Dutch household survey data. They found religious membership and participation to have no effect on income and vice versa. In a more general approach using European and World Values Survey data from 25 countries, the same authors concluded that “church membership is found to have a positive effect on income for high-income countries,” while “this effect is negative for low-income countries” (Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf 2010). Using data from the German Socio-Economic Panel Survey, Cornelissen and Jirjahn (2012) found that “being raised by two religious parents, but having no current religious affiliation is associated with higher earnings.” They control for potential endogeneity by instrumenting religious affiliation with having grown up in a rural area. Spenkuch (2017) exploited a sixteenth century peace treaty, which determined the religion to be either Protestantism or Catholicism in a given region of Germany to account for endogeneity in religion. For the German case, the author found that Protestants work longer hours than Catholics, while there is no difference in hourly wages.

Evidence on religion and labor-market-related outcomes in developing countries is limited. Adeyem et al. (2016) documented a positive effect of religion on female labor market participation in Nigeria on the basis of Demographic and Health Survey data. Permani (2011) identified positive effects of religious social capital on earnings using household survey data from Indonesia. She controlled for unobservable selection using a Heckman (1979) correction for selection bias. This method is also the approach used by Öhlmann and Hüttel (2018) in their South African case study. Using household survey data, the authors showed a positive effect of a specific African Independent Church and African traditional religion on household income. The finding of a positive effect of membership in an African Independent Church corresponds to Beck and Gundersen’s (2016) findings from the Ghanaian context. Using data from the Ghana Living Standard Survey in a quantile regression approach, they identified positive relationships of religious membership and income for women who are members of African Independent or Pentecostal and Methodist Churches. However, in contrast to Öhlmann and Hüttel (2018), they identified a negative effect of African traditional religion. To account for endogeneity, Beck and Gundersen (2016) used the religious density in the sampling cluster as an instrument. An entirely different identification strategy is employed by Bryan et al. (2021). The authors conducted a randomized controlled trial of a training program by an evangelical Protestant non-governmental organization in the Philippines, which encompasses both a Christian values component and a (non-religious) health and livelihoods component. They investigated the effect of the training on persons receiving either one of those components or both components together. Their results demonstrated that the Christian values component increases religiosity and income, while there is no effect on other economic indicators, such as consumption or total labor supply. The values component decreases perceived economic status. At the same time, the health and livelihoods component has no effect on any of the indicators.

2.2. Religion and Labor-Market-Related Attitudes

In one of the most influential studies in the area of religion and economic performance, Guiso et al. (2003), focused on economic attitudes. Using World Values Survey data from 66 countries, the authors found that religious upbringing, religiosity, and religious practice promote economically conducive attitudes. Combining World Values Survey and European Values Survey data to comprise 82 countries, van Hoorn and Maseland (2013) investigated the existence of a Protestant work ethic by examining the effect of unemployment on subjective wellbeing. They found that “unemployment hurts Protestants more and hurts more in Protestant countries.” Kirchmaier et al. (2018) used survey data from the Netherlands to analyze the relationship of religious participation on various economic behavioral outcomes. Their findings are robust to the use of an instrumental variable model using parents’ religiosity as the instrument. They showed that religious participation is associated with ethical behavior and lower preference for redistribution. In an additional behavioral experiment, they found that religious participation does not increase anonymous trust. Economically conducive attitudes were also the focus of Brañas-Garza et al. (2009). They highlighted that, in Latin America, religious practice correlates with trust in other people and in public and economic institutions. Audretsch et al. (2013) investigated entrepreneurial attitudes using the 2004 Employment-Unemployment Survey in India. They concluded that “religions like Islam and Jainism are more favorable for self-employment,” while “Hindus are less likely to be self-employed.” Using behavioral experiments, Benjamin et al. (2016) also found diverging effects of religion on economic attitudes. They increased the respondents’ religious salience using religious priming, thus creating an exogenous variation in their religiosity. The authors found that “priming causes Protestants to increase contributions to public goods, whereas Catholics decrease contributions to public goods, expect others to contribute less to public goods, and become less risk averse.” Religious priming has no effect on other outcomes, such as work effort or generosity.

In summary, there are no unanimous conclusions on the relationship of religion and economic attitudes and outcomes. While the larger part of the microeconomic research in the field seems to point toward positive effects of religion, the identified correlations and effects are diverse. One core methodological issue is the choice of variables for religion. Most studies rely either on membership indicators, frequency of worship attendance, or self-reported intensity of beliefs. Of those mentioned above, only the studies by Arano and Blair (2008) and Guiso et al. (2003) use more comprehensive measures of religiosity. The present study broadens this strand of research using the Centrality of Religiosity Scale, as a multidimensional and interreligious measure of religiosity (Huber et al. 2020; Huber and Huber 2012).

The identification of causal effects of religion remains a challenge in the literature. The potential endogeneity due to unobserved variables and simultaneity is often not dealt with. Of the 19 studies cited above using observational data, eight do not account for endogeneity at all, four use a simultaneous equation framework, five use instrumental variable approaches, and two use a Heckman (1979) approach to correct for selectivity issues (the other two studies are special cases, an experimental study, and a randomized controlled trial). The most common instruments for religion are geographical factors, such as regional religious density (Beck 2016; Gruber 2005), distance from Muslim schools (Permani 2011), or rural area upbringing (Cornelissen and Jirjahn 2012). Öhlmann and Hüttel (2018) used the relationship with a local chief, and Kirchmaier et al. (2018) used parents’ religious participation. Experimental approaches, such as the one used by Benjamin et al. (2016), provide an alternative solution, but are limited to quite specific laboratory conditions. Bryan et al. (2021) successfully demonstrated that randomized controlled trials can be used to identify effects of religion. While this is a promising avenue that future research should certainly build on, the approach is limited to specific interventions. This study instead proposes a novel approach that relies on instrumental variables based on contingency experiences and is relatively easy to apply in cross-sectional or panel surveys.

3. Labor Market and Religion in South Africa

With a Gini coefficient of 0.63 (2015), South Africa remains among the most unequal societies of the world (World Bank 2018). While the living conditions of the majority have improved since the end of apartheid in 1994, over 55% of the South African population lives below the poverty line of roughly USD 72 per month (Statistics South Africa 2017). South Africa’s economy has a dual nature (African Development Bank 2018), in the words of its former president Thabo Mbeki, divided into a “first world economy” and a “third world economy” (Mbeki 2003). This is reflected in the dichotomous structure of the country’s labor market. The upper 10% of the working population earns wages at the levels of high-income countries from relatively secure formal employment. Wages at the lower end of the distribution are at the levels of the poorest countries in the world, and employment is informal and insecure (World Bank 2018). In the literature on the South African informal sector, it is generally accepted that informal economic activity, consisting mostly of micro businesses, is only a second-best option to formal sector economic activity (Davies and Thurlow 2010; Nackerdien and Yu 2019). This is not surprising considering that half of the informal businesses had a turnover of around USD 108 per month and only around 10% made monthly profits of over USD 430 (Statistics South Africa 2014). Moreover, South Africa has extremely high unemployment. The official unemployment figure of 26.7% of the economically active population hides a large number of discouraged jobseekers. When including them in the category of unemployed, the figure rises to 36.3% (Statistics South Africa 2018). While the high levels of unemployment are likely to have structural causes (Banerjee et al. 2008; World Bank 2018), the question remains as to what determines whether an individual manages to access the formal labor market or, as a second-best option, engages in informal economic activity. Sociodemographic characteristics and education are key factors in determining both labor force participation and individual labor market success. Racial discrimination continues to play a role as well (Branson and Leibbrandt 2013; World Bank 2018). Thus far, no economic study has investigated the role of religion in this context.

Religion is an important factor in South African society, having high relevance in both public and private life. According to the 2001 census (thus far, the most recent including religious affiliation), 80% of the South African population are affiliated with Christian churches, around 15% have no religion, and the remainder are members of other religions, such as Islam and Hinduism (Statistics South Africa 2004). Elements of African traditional religion (ancestral belief systems) and Christianity are often practiced alongside each other. Average levels of religiosity are high in South Africa and religious worldviews are common. Seventy-four percent of South Africans consider religion very important in their lives (Pew Forum 2010). In the Livelihoods, Religion and Youth Survey dataset used here, the mean value of the CRS is 4.03, indicating that, on average, people are highly religious and only 1.84% of the survey sample falls into the category non-religious.

Within the Christian faith, the religious landscape is both highly diverse and dynamic. Mission-initiated churches (Catholics and historic Protestant denominations) are found along with African Independent and Pentecostal churches. New churches emerge, and conversion from one church to another—often multiple times in a lifetime—is a common phenomenon. The dynamic is particularly high with respect to African Independent and Pentecostal–Charismatic churches, which represent the majority of the population in the country (Öhlmann et al. 2016). As they share common characteristics, they are often summarized as African Initiated Churches or African Initiated Christianity (Anderson 2000; Öhlmann et al. 2016, 2020). While they constitute a heterogeneous movement with diverse theological tenets, research has emphasized their common conducive role in promoting development and economic success. African Initiated Churches foster an intensive spirituality; religion permeates all spheres of life and becomes a determinant of individual economic attitudes, behavior, and actions (Freeman 2012; Turner 1980). They “maintain a magico-religious worldview” (Freeman 2012), connecting their theology to African belief systems and “African religious sensibilities and aspirations” (Asamoah-Gyadu 2015). Thus, the churches have a high “transformative potential” (Eisenstadt 1968). They transform “individual subjectivities”, fostering personal transformation and enabling believers to acquire the agency to take their lives in their own hands (Freeman 2012). This goes along with a strong this-worldly orientation; salvation is seen as “here and now” (Anderson 2000; Freeman 2012). In the framework of a “Gospel of Prosperity,” particularly the Pentecostal–Charismatic churches portray material success as divine blessing and promise (Beck and Gundersen 2016; Heuser 2015, 2016). However, material blessings are not expected to come by prayer alone. Ethics of hard work and strict moral codes are fundamental parts of their belief systems (Freeman 2012; Turner 1980). A strong emphasis is put on education and entrepreneurship as key factors for success (Freeman 2012; Öhlmann et al. 2016; Schlemmer 2008; Turner 1980). This goes along with the dense social structure, mutual support, and initiatives to improve individual and communal wellbeing at various levels (Öhlmann et al. 2016).

Several studies on religion and labor-market-related outcomes from the disciplines of theology and sociology of religion indicate that particularly African Independent and Pentecostal–Charismatic churches positively contribute to their members’ labor market performance. Cross et al. (1993) highlighted the role of African Independent Churches in the economic empowerment of youth in South African metropolitan areas. The churches provide support to rural–urban migrants through material help, social integration, and the provision of information on economic opportunities. In a similar vein, Oosthuizen (1997) highlighted the role of African Independent Churches in small business support. Mafuta (2010) showed how South Africa’s largest religious community, the Zion Christian Church, influences its adherents’ individual work ethics, identity, and attitudes. Mafuta argued that their labor market potential is higher than in other churches, inter alia due to their reputation of being hard-working, sober, and reliable. Meyer (2004) showed that the actions and attitudes of adherents of Pentecostal–Charismatic churches change because of their membership in the church. The positive message emphasizing this-worldly salvation and material wellbeing causes them to be “lifted up in social standing, and their lives stabilize.” In a large-scale study on Pentecostal churches, Schlemmer (2008) highlighted a high valuation of education, the affirmation of positive ethics in professional and private life, and the promotion of entrepreneurial activity as key features. Similar results with respect to education, training, and entrepreneurship were reported by Dickow (2012). The author concluded that members of Pentecostal–Charismatic churches have high upward social mobility, are geared toward improving their lives, and display an optimistic outlook toward the future. Moreover, they constitute dense social networks. Recently, Öhlmann et al. (2016) investigated African Independent and Pentecostal–Charismatic churches with respect to their potential for development cooperation. They showed that many of these churches provide their members with means to improve their economic situation in material and immaterial ways. The churches are development actors. They not only focus on spiritual realms but also engage in improving the material wellbeing of their members and the wider communities (e.g., through education and training programs). The authors highlighted that these churches focus on enabling people to be economically independent. In summary, there seems to be a consensus in the theological and sociological literature that African Independent and Pentecostal–Charismatic churches have substantial transformative effects on their members’ attitudes and actions (Öhlmann et al. 2016). These results correspond to Beck and Gundersen’s (2016) findings from the Ghanaian context and Öhlmann and Hüttel’s (2018) results from South Africa.

4. Data and Descriptive Statistics

To investigate the effect of individual religiosity and different religious tenets on labor market performance in South Africa, a household survey was specifically conducted. The survey focused on predominantly Sepedi- and Setswana-speaking municipalities of Limpopo, North West, Mpumalanga, and Gauteng Provinces of South Africa and took place from June to July 2016. Rural, peri-urban, and urban areas are covered. The sample was restricted to these areas to keep cultural and geographical heterogeneity low. A high number of distorting factors could potentially have impeded the identification of statistically significant effects. Moreover, restricting the sample to areas in which two major South African indigenous languages are dominant allowed conducting interviews in the local languages. Sampling was done in a multi-stage cluster approach based on Statistics South Africa dwelling frame data. Interviews were conducted using a structured questionnaire in English, Sepedi, and Setswana. The survey included 1039 household interviews (comprising 4981 individuals) and 1864 individual interviews. Because of its focus on labor market performance, the analysis presented here uses a subsample of 1086 working-age individuals. It includes all persons between ages 16 and 60 who are out of secondary school (those that have ceased to attend secondary school, regardless of which degree they have completed). The threshold of 60 is selected in line with the minimum retirement age in South Africa. Labor market participation rates decline from that age onwards. Each person from the age of 60 onwards having an annual income below ZAR 69,000 (USD 4982) is entitled to a government old age grant of ZAR 1500 (USD 108) per month (South African Social Security Agency 2016).

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analysis. The data include comprehensive information on sociodemographic characteristics, education, social capital, religion, and economic activity. With respect to religion, comprehensive data are available on religious adherence and individual religiosity. The dataset allows for the differentiation of specific categories of Christian churches, as Christianity is the dominant religion in the survey area. Seventy-three percent of the persons in the sample are church members. The main categories of churches are mission-initiated (15% of the sample), Apostolic (14%), Pentecostal–Charismatic (11%), and Zion Christian (25%) churches (cf. Anderson 2000). Each of the church categories is indicative of a set of common theological tenets and practices and hence assumed to be a proxy for religious content. At this point, it needs to be noted that membership indicators might in many contexts be only a weak indicator of different religious content. Aside from the fact that the dataset used for this paper does not include more refined variables on religious content, this is justified because of the specificities of the South African context and the high context relevance of the religious categories employed. In the South African context, conversion from one denomination to another is a relatively frequent phenomenon. Such religious switching takes place because of different theological tenets and practices. In such contexts, affiliation might therefore be a much better indicator of religious content than in those contexts in which religious switching is relatively uncommon and where therefore other factors, such as the role of parents’ religious affiliation and religious socialization, play a greater role. Moreover, in the design of the survey, close attention was paid to not imposing pre-determined categories of churches. To ensure a high degree of context-relevance in the categories of religious communities employed here, a qualitative pre-study was conducted before the quantitative data collection. In several focus group discussions taking place in different locations of the survey area, participatory appraisal methods were employed to collect information on the different categories of churches relevant in the local context. The categorization emerging from the pre-study was triangulated with the categories developed by Anderson (2000) in his seminal study on churches in South Africa. Anderson categorizes South African churches based on a comprehensive large-scale survey, which shows belief systems and practices to differ substantially between the categories. It is important to note that the basis for Anderson’s categorizations is not official documents or church leadership statements. Rather, churches are categorized based on the individual members’ responses to questions on beliefs and practices. The following paragraph briefly describes the resultant categories and their characteristics.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

While mission-initiated churches describe the historic Protestant denominations and the Catholic church, which were imported to South Africa through mission and immigrant movements, the latter three categories are part of the wider movement of African Independent and Pentecostal–Charismatic churches portrayed above. Hence, we are able to differentiate between different groups of churches within the broader movement of African Initiated Christianity, similar to Beck and Gundersen (2016). The first category of these churches, Apostolic churches, represents primarily small churches (even though a few larger ones exist as well, such as St John’s Apostolic Faith Mission). They originated in the first wave of Pentecostal revival, which swept to South Africa from the US in the first half of the twentieth century. Their theology often has close links to African traditional belief systems (Anderson 2000; Thomas 2007). In terms of their origin in the Pentecostal movement and their reference to African traditional belief systems, they are similar to the second category, Zion Christian churches. However, the Zion Christian churches are two large churches with membership in the millions. The two Zion Christian churches emerged out of a leadership dispute but remain similar in structure and theology. They put strong emphasis on moral guidelines and discipline (e.g., prohibiting the consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and pork), while simultaneously providing spiritual support and promoting agency and self-reliance (Anderson 2000). Pentecostal–Charismatic churches are a group of smaller churches. They emerged in South Africa from the 1980s onwards during the second wave of Pentecostal renewal. While they operate within the framework of a spiritual worldview, they disassociate themselves from any practices related to African traditional religion (Anderson 2000; Freeman 2012). They are also strong advocates of a “Prosperity Gospel”—that is, a theology that portrays material success as a divine blessing attainable by everyone (Heuser 2013). All three categories share the economically conducive features outlined in Section 3. The data furthermore include information on the practice of African traditional religion, the second important religion in the region. A unique feature of the data is that they allow for the simultaneity of church membership and traditional religious practice. The overlap of Christianity and African traditional religion is a common phenomenon in South Africa. In our data, 33% of the respondents are church members and report to be practicing African traditional religion as well. Sixteen percent practice traditional religion only, while 11% are not affiliated with any religion. Table 2 provides summary statistics by religious affiliation.

Table 2.

Key summary statistics by church membership and African traditional religion.

Individual religiosity is measured in the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (Huber 2003; Huber and Huber 2012), included in the data as variable CRS.6 The CRS is a novel measure of religiosity developed for the international Religion Monitor Survey (Huber 2009; Huber and Krech 2009; Pickel 2013). Studies have shown its interreligious and intercultural applicability (Huber et al. 2020). It measures individual religiosity in five religious core dimensions. Responses to specific questions in each of the dimensions are coded on a scale from 1 to 5. The mean across the five dimensions constitutes a measure of a person’s religiosity. Based on the values, a person can be categorized as “non-religious” (CRS ≤ 2), “religious” (2 < CRS > 4), or “highly religious” (CRS ≥ 4). In our data, the interreligious version of the CRS-5, CRSi-7, was adapted to better accommodate spiritual worldviews (Ashforth 2005; Gifford 2015) and African traditional religious practice in the South African context of this study. The questionnaire items 1, 2, 4, and 5 were slightly rephrased to ensure context-relevance and translatability into the local languages Sepedi and Setswana, while careful attention was paid to not changing the meaning of the respective questions. In the intellectual dimension (1), direct reference to “spiritual” issues was included, while in the ideological dimension (2), “something divine” was specified as “ancestors or spirits”. Similarly, in dimension (5) (experience), “something divine” was concretized as “ancestors or spiritual forces”. In the dimension of public practice (dimension (4)), “religious” services was changed to “church” services. Similar to the CRSi-7, in two dimensions, additional interreligious items were included. In the modified version proposed here, these were specifically designed to relate to African traditional religion. In dimension (3), the original interreligious CRSi-7 item 04b, “How often do you meditate?”, was modified to “How often do you praise the ancestors?”, and in dimension (4), the additional item, “How often do you take part in African traditional religious activities?”, was added. Unlike in the original CRSi-7, no additional item was included in dimension (5). Table 3 provides the full overview of the version of the CRS employed in comparison to the CRS-5.

Table 3.

Inventory of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale.

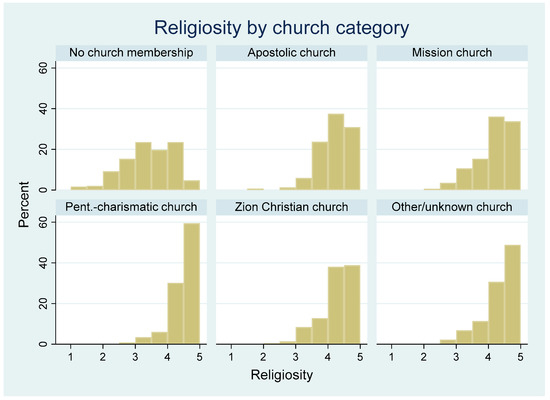

The mean value of the variable CRS in the dataset is just above 4 (Table 1, Panel II). On average, people in the survey area are highly religious. This corresponds to similar findings from Centrality of Religiosity Scale data from Nigeria (Hock 2009). Table 2 depicts mean religiosity across the different religious communities. Church members are more religious than non-members. The figures confirm findings from sociology of religion indicating that Pentecostal–Charismatic churches foster a particularly high degree of individual religiosity. The hypothesis that members of African Independent and Pentecostal–Charismatic churches are more religious in general does not hold. While mean values of religiosity are higher in the Pentecostal–Charismatic churches and the Zion Christian churches, the difference between Apostolic churches and mission-initiated churches is not statistically significant. Figure 2 shows the distribution of religiosity for the different categories. The distribution for members of Pentecostal–Charismatic churches has the largest skewness toward the highly religious.

Figure 2.

CRS by church category. Note—Figure shows the distribution of individual religiosity according to the different categories of churches in the sample, measured according to the Centrality of Religiosity Scale, CRS (Huber and Huber 2012). A value less than or equal to 2 indicates “non-religious” persons, values between 2 and 4 indicate “religious” persons, while a value equal to or greater than 4 is categorized as “highly religious”.

I operationalize contingency experience using a questionnaire inventory focusing on major events experienced in life. First, I compute Contingency experience, an index of the responses to the following four questions:

- A. “Have you ever been in situations of incredible joy?”

- B. “Have you ever experienced (positive or negative) events in your life that you could not explain?”

- C. “Have you ever been in situations of fundamental despair?” and

- D. “Have you ever experienced the death or loss of a person close to you?”

All four questions have a yes = 1/no = 0 answer option. The responses are aggregated by computing the mean of these four dimensions. Table 4 shows the summary statistics for the individual questions and the index. A second, simpler indicator of experiences of contingency is Experience of death, an indicator variable using only the response to question (D), the experience of death in close social proximity. Using the response to this question alone has the advantage of being less prone to interpretation by the respondents themselves. Both indicators of contingency experience are positively correlated with CRS (Table 4). To further validate that experiences of contingency are predictors of religiosity, I regress CRS on the different dimensions of contingency and the index Contingency experience, including the full set of covariates listed in Table 1 (Panel I). Column (7) in Table 4 shows the results. All dimensions have a significant and positive correlation with CRS when controlling for other covariates. Having experienced the loss of a close person increases individual religiosity by 19% of a standard deviation. Having experienced all four dimensions, as captured in the index Contingency experience, increases CRS by 70% of a standard deviation.

Table 4.

Contingency experience.

With respect to labor market performance, the dataset offers information on formal and informal (self‑)employment. Additionally, labor market attitudes are measured as self-reported job-seeking activity (not looking for work, waiting for work to come, and actively looking for work). This information is summarized in an ordinal scale indicating a person’s labor market status. Formal employment or self-employment is given the highest value (3), followed by informal employment or self-employment (2), and actively looking for work (1). The underlying assumption is that a higher value constitutes a better labor market outcome from the individual’s point of view. This assumption is justified due to the high unemployment rates in South Africa and the large wage differential between the formal and informal sectors (World Bank 2018). Due to the dual structure of the labor market and the high wage differential between formal and informal labor markets, informal employment is an alternative option for those that have not (yet) found employment in the formal sector. Category 0 includes all individuals not actively looking for work or working (i.e., those reporting “waiting for work to come” or “not looking for work”) or 17.4% of the sample. This category includes two different groups of persons: those who could work in principle but chose not to do so (e.g., because they have given up actively looking for employment) and those who are not able to work (e.g., disabled persons or women with small children). It might be argued that including category 0 in the analysis distorts the results. However, in light of the high portion of discouraged jobseekers in the South African economy and the potential effect of religion on attitudes such as work ethics and motivation documented in sociology of religion, it is vital to include them. Motivational effects of religion can only be identified by differentiating between those that are not actively looking for work and those that are. At the same time, I control for those factors that decrease the probability of actively looking for work, such as disability, the number of children in the household, the presence of additional working-age household members, gender, age, and education (see Ntuli and Wittenberg 2013). Moreover, a t‑test shows that the proportion of women in this category (66%) is not significantly higher than in the rest of the sample (63%; p-value = 0.40).

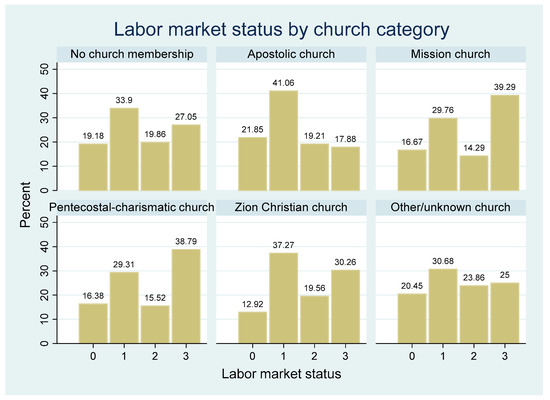

Table 5 shows the frequencies of each labor market status. Only 29.6% of those at working age are economically active in the formal labor market. Over one-third of the population (34.4%) at working age is not working but is actively looking for work. The corresponding unemployment rate of 51.8% of the economically active population is higher than the national average due to the high proportion of rural areas covered by the survey. The distributions of labor market outcomes in the different church categories in Figure 3 show that labor market performance differs substantially across the different churches.

Table 5.

Frequencies of labor market outcomes and mean religiosity by labor market outcome.

Figure 3.

Labor market status by church membership. Note—Figure shows the distribution of labor market status according to church category. Labor market status 0 indicates not working and not actively looking for work, 1 indicates not working but actively looking for work, 2 indicates employment or self-employment in the informal sector, 3 indicates formal sector employment or self-employment.

5. Estimation Strategy and Identification

5.1. Estimation Strategy

The main econometric approach is the estimation of ordered probit and instrumental variable ordered probit models (the following description follows Wooldridge (2010)). I use the ordered probit model due to the ordinal nature of the dependent variable, Labor. It can take outcome values from 0 to 3, indicating different labor market statuses (Table 5).7 Covariates include sociodemographic characteristics at the individual and household levels, migration, education, and social capital, as listed in Table 1 (Panel I). Furthermore, I control for household composition and social grant receipt, as these factors affect household labor market supply (Ardington et al. 2009).

For the ordered probit approach, a latent continuous variable Labor* is defined:

where xi is a 1 × K a vector of the explanatory variables, β (K × 1) denotes the vector of the respective estimation coefficients, and ei is the error term (ei ~ N(0, 1)). Subscript i denotes the individual. Explanatory variables include sociodemographic characteristics at the individual and household levels, education, social capital, migration, language, and ward indicators. To examine whether religion is a factor influencing these outcomes, xi includes a set of proxies for different theological tenets and religious intensity. Indicator variables for membership in different church denominations stand for a specific set of beliefs and so does the indicator for the practice of African traditional religion. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (see Section 4) constitutes an index of individual religiosity independent of specific tenets. Labor assumes the value of 0, 1, 2, and 3 depending on the value of Labor* according to unknown cut points αj (with j = 1, 2, 3):

The cut points are estimated in the model. The response probability of each outcome of Labor is the probability that the value of the latent variable Labor* is between the respective cut points. The probabilities are as follows:

where Φ is the cumulative distribution function. Maximum likelihood estimation is used to estimate the model.

The model described above assumes that all explanatory variables are exogenous. However, CRS can be expected to be endogenous (i.e., Cov(ri,ei) ≠ 0, where ri denotes CRS). As the individuals self-select into religion and religious practice, it is likely that there is a bias due to omitted variables and simultaneous equations. Unobserved factors might influence individual religiosity and labor market performance, or the causality might run from labor market performance to religiosity. If CRS is endogenous, this leads to biased estimates of the coefficients in Equation (1). To account for this endogeneity, I estimate just-identified instrumental variable ordered probit models (Roodman 2011; Wooldridge 2010). The index model in Equation (1) is reformulated to the following:

where xi is the (1 × (K − 1)) vector of exogenous explanatory variables (excluding CRS) and β ((K − 1) × 1) is the coefficient vector. The coefficient of the endogenous variable CRS is denoted by γ.

The reduced form equation for CRS is as follows:

where δ is the (K − 1) × 1 vector of coefficients in the reduced form, zi denotes the instrumental variable, and θ is its coefficient. The error terms ui and vi are assumed to follow a joint normal distribution (ui,vi ~ N(0,Σ)). The model is estimated using maximum likelihood estimation using the extended ordered probit (eoprobit) routine in Stata 15.

The identifying conditions of the model are as follows:

The relevance condition in Expression (6) states that the instrumental variable zi must be partially correlated with ri conditional on all other explanatory variables. The condition can be statistically tested by testing the significance of the coefficient in the reduced form. The validity condition in Equation (7) implies that the instrument is unrelated to Labor except through its partial correlation with CRS and can hence be excluded from the outcome equation (Equation (4)). This condition cannot be directly tested.

5.2. Contingency Experience as an Instrumental Variable for “Treatment” with Religion

When investigating potential causal mechanisms with respect to the effects of religion, the challenge is to find a variable fulfilling the two identifying conditions. Drawing on works by Luhmann (1982), Lübbe (2004), and Norris and Inglehart (2011), I identify the experience of contingency as an instrument for “treatment” with religion. Contingency experience (Luhmann 1982) refers to experiences of “existential insecurity” (Norris and Inglehart 2011). Such insecurities can, for example, be produced by a death in the family, illness, natural disasters, or other unpredictable events affecting one’s life. Religion provides a means of dealing with these existential insecurities, risk, and unpredictable events in a process of “religious coping” (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005; Pargament 1997, 2012). “Religions provide existential reassurance to people who live in conditions of extreme vulnerability and uncertainty” (Silver 2006) and, as the review by Ano and Vasconcelles (2005) shows, “religious coping strategies are significantly associated with psychological adjustment to stress”. Consequently, individual religiosity would increase with the contingencies a person experiences. Such an increase in religiosity might, for example, become measurable in the CRS’ dimensions of private practice (increased prayer frequency), public practice (increased religious service attendance), or the intellectual dimension (increased frequency of thinking about religious issues). Recent empirical studies demonstrate that contingency experiences have an effect on religiosity. In her recent article, Bentzen (2019) showed that the occurrence of earthquakes in geographic proximity increases individuals’ intrinsic religiosity. The study is based on individual data from 96 countries (including South Africa) and the results are consistent with the notion that religion is used as a mechanism to cope with the occurrence of unpredictable natural disasters. “Adversity, caused by natural disasters,” as Bentzen argues, “instigates people across the globe to use their religion more intensively” (Bentzen 2020). In a similar vein, the same author shows that religiosity globally increased in the COVID-19 pandemic, based on an assessment of the number of Google searches for prayer (Bentzen 2020)—indicating an increase in the dimension of private practice. The study on Canada by Zapata (2018) shows that “among religious individuals, human losses increase the intensity of their religious preferences”. The author concludes that “religion provides people … with a mechanism to deal with adverse experiences resulting from climate disasters.” These studies are in line with Norris and Inglehart’s (2011) hypothesis that religiosity is higher in contexts of existential insecurity.

However, the relationship of contingency experience and religiosity is likely more complex. Individual religiosity is not only determined by a single factor. It is influenced by a wide range of social and cultural factors as well as highly dependent on the individual’s religious socialization, experiences, personal traits, age, etc. (for overviews, see Aleksynska and Chiswick 2013; Saroglou 2021). Regarding the mechanisms described in the studies on religious coping, a relevant question seems to be whether an individual already has a level of religiosity or religious socialization. Bentzen (2020) found no effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of prayer-related Google searches for the decile of those countries that are least religious. Similarly, Zapata’s (2018) findings support the hypothesis that natural disasters lead to increased religiosity among the religious and further erode religious beliefs among the less religious. As Pargament (2012) points out, “a number of studies have shown that people are more likely to involve religion in coping when religion is a larger part of their orienting system”, i.e., in contexts marked by high levels of religiosity and the prevalence of spiritual and religious worldviews. “People draw on religious solutions to problems from a more general orienting system that is made up of well-established beliefs, practices, attitudes, goals and values” (Pargament and Raiya 2007), i.e., a prerequisite for religious coping is that people can access a religious belief system. Moreover, the religious and cultural context has an important influence on the levels of individual religiosity (Aleksynska and Chiswick 2013; Pargament 2012) and should therefore be taken into account in empirical studies.8

As outlined in Section 3, the South African context is highly religious. Religious and spiritual worldviews, belief systems, and practices constitute important aspects of people’s lives. Considering the studies cited above, which show increases in religiosity induced by contingency experience for people who are already religious, there are hence good reasons to assume that, in South Africa, contingency experiences will have a positive effect on religiosity. Moreover, studies have highlighted both the role of religion in coping with adversities (see, for example, Masondo 2013; Oosthuizen 1988) as well as increases in specific forms of religiosity because of existential insecurities (see, for example, Ashforth 2005). This also emerged from the qualitative pre-study: the role of comprehensive spiritual “healing”—essentially the notion of dealing with adversities and insecurity through religious means—featured prominently both in focus group discussions and key informant interviews. Looking at the data at hand in this respect, we find a robust positive relationship of contingency experience and religiosity, as expected (Table 4). All dimensions of the index of contingency experience are positively correlated with the CRS. I therefore proceed to assume contingency to be an exogenous factor that leads to increases in religiosity as measured in the CRS.

I exploit the positive relationship of contingency experience and religiosity in the data using two indicators of contingency experience introduced in Section 4, Contingency experience and Experience of death. With respect to Contingency experience, the first three questions on situations of fundamental despair/joy and unexplainable situations might be argued to include, at least partially, an interpretation on the part of the respondent. Respondents might classify a situation as being of fundamental despair/joy or as being unexplainable on the basis of their religious background. If religiosity influenced the answers to the contingency questions, this would constitute an endogeneity problem in the reduced form and violate the exclusion restriction (7). While this can be considered unlikely, I hedge against this possibility by using the second indicator of contingency, Experience of death, which can hardly be argued to be driven by religious interpretation. Moreover, previous research suggests that experience of death constitutes a contingency experience that can contribute to increased religiosity (as, for example, shown by Zapata 2018) and that religion is used to cope with experiences of death in close social proximity (Ungureanu and Sandberg 2010). In Section 6.2, I scrutinize the validity of the exclusion restriction for our case by evaluating potential alternative pathways from contingency experience to labor market performance in the data.

5.3. Controlling for Endogeneity of Church Membership and African Traditional Religion

In addition to the endogeneity of religiosity, I also control for the endogeneity of church membership and African traditional religious practice. In addition, in the cases of these variables, issues of self-selection, omitted variables, and simultaneous equations might cause endogeneity problems. Hence, the econometric model outlined above is extended by including the indicators Church and African traditional as endogenous regressors. As instrumental variables I use the share of persons per ward who are church members (Share church) or practice African traditional religion (Share Afr. traditional), respectively.9 The identifying condition (6) implies that the share of persons who are church members (or the share of persons practicing African traditional religion, respectively) is a good predictor of individual church membership (or African traditional religious practice, respectively). The validity condition (7) implies that the respective shares of church members and persons practicing African traditional religion do not affect individual income (except through a partial correlation with individual membership/practice). Whether or not the validity condition holds when using the shares of affiliation as instruments can be disputed. However, I do not make causal claims with respect to the church membership and African traditional religious practice but rather use them as controls to assess the robustness of the effect estimates of religiosity.

Accounting for the endogeneity of all three variables, CRS, Church, and African traditional, the above model becomes the following:

where xi is a vector of exogenous covariates, and β is the coefficient vector. The estimation coefficients of the endogenous variables CRS, Church, and African traditional are denoted γ, ζ, and η, respectively. The first-stage equations are as follows:

where δr, δc, and δa are vectors of coefficients in the first-stage estimations, and z1i, z2i, and z3i denote the instrumental variables. In addition, θr1, θr2, and θr3 are the first-stage effects of the instruments on CRS, while θc1, θc2, and θc3 are the first-stage effects of the instruments on Church, and θa1, θa2, and θa3 are the first-stage effects of the instruments on African traditional. The error terms in the first stages are denoted vri, vci, and vai. The model is also estimated using maximum likelihood estimation using the eoprobit routine in Stata 15.

6. Results

6.1. Estimation Results

In Table 6, columns (1) to (5) display ordered probit estimation results of the ordinal scale of labor market outcomes (Labor) using varying sets of explanatory variables for religious affiliation and religiosity. Column (1) uses a single indicator of church membership along with an indicator of African traditional religion. Church membership does not have a significant coefficient, and the coefficient of African traditional religion is only weakly significant. Column (2) shows the results using differentiated church membership indicators instead of a single indicator for membership in any church. The different signs and magnitudes of the coefficients suggest heterogeneity in the relationship of church affiliation and labor market performance. Only two of the church category coefficients are significant, Pentecostal–Charismatic church (at the 10% level) and Zion Christian church (at the 5% level); the coefficient of African traditional is now significant at the 5% level. Columns (3) and (4) present the results of Models (1) and (2), when adding individual religiosity, as captured by the Centrality of Religiosity Scale in the variable CRS. The coefficient of church decreases nearly ten-fold when comparing Models (3) to (1), while the coefficient of African traditional increases slightly. This pattern is similar in the comparison of Models (4) and (2). African traditional religion’s coefficient has a similar magnitude as in Model (2), while the church category coefficients differ substantially. The size of the coefficients of Pentecostal–Charismatic church and Zion Christian church decreases by around 50%, and neither remains statistically significant. The coefficient displaying the largest absolute value is that of Apostolic church. It is negative but not significant. The coefficient of CRS is significant at the 5% level in both Models (3) and (4). From these results, we can highlight the following preliminary findings. First, religion is positively associated with labor market performance. Second, church membership per se is not related to better labor market performance; the association rather seems to be heterogeneous across church categories. Third, individual religiosity is a better predictor of labor market performance than membership in different churches. What seems to matter in the relationship of religion and labor market performance is not the membership in a specific church, but the intensity of belief regardless of its specific theological content. The OLS estimation results of the same models displayed in Table A1 in Appendix A confirm the general picture.

Table 6.

Estimation results ordered probit model.

Table 7 displays instrumental variable ordered probit estimates, accounting for the potential endogeneity of religion. CRS has coefficients significant at least at the 5% level in all five specifications. Models (1) and (2) correspond to Model (5) in Table 6. They only include one variable relating to religion, CRS. In Model (1), it is instrumented with Contingency experience, and in Model (2), it is instrumented with Experience of death to hedge against potential endogeneity of self-reported contingency experiences in the first stage. In both cases, the coefficient of CRS remains significant at the 1% level, and the magnitude of the coefficient increased around seven-fold (to 0.742 and 0.772) compared to the non-instrumented estimates in Table 6.

Table 7.

Estimation results instrumental variable ordered probit model.

Models (3) to (5) additionally include the variables Church and African traditional. They are instrumented with the respective share of church members and adherents of African traditional religion in the ward. CRS continues to have a significant coefficient, while none of the coefficients of Church and African traditional shows a significant effect. In Model (3), which instruments CRS with Contingency experience, the coefficient is 0.775, a very similar magnitude as in Models (1) and (2), and significant at the 1% level. In Model (4), in which the instrument is Experience of death, the coefficient increases to 0.910. The fact that the Experience of death is only weakly significant in the first stage might highlight weak instrument issues in this estimation. Model (5) provides a robustness check using a different instrument for CRS. Similar to the instruments included for Church and African traditional, CRS is instrumented with its average value in the ward. The coefficient is around one-third smaller (0.430), but still around four times the size of the non-instrumented estimates in Table 6 and significant at the 5% level.

With respect to the instruments’ relevance, the first-stage estimates show that both Contingency experience and Experience of death instruments are positively correlated with CRS and have significant explanatory power. The coefficient of Contingency experience is significant at the 1% level and the coefficient of Experience of death at the 5% level. Having had all four contingency experiences increases religiosity by between 64.1% and 70.4% of a standard deviation, while an experience of death in close social proximity increases religiosity by between 14.2% and 23.5% of a standard deviation. The shares of church members and of persons practicing African traditional religion are good predictors of Church and African traditional. An increase in the share of church members in the ward by one standard deviation increases the probability of being a church member by between 4.5 and 6.5 percentage points, while an increase in the share of adherents of African traditional religion increases the probability of practicing African traditional religion by between 9.4 and 9.6 percentage points. The first-stage coefficient of Mean CRS in Model (5) shows mean religiosity in the ward to be a relevant instrument for religiosity as well. An increase in Mean CRS by one standard deviation is associated with an increase in CRS by 19.2% of a standard deviation.

Regarding the magnitude of the effects of CRS on Labor, I estimate the average marginal effects for the coefficients in Table 6 and Table 7. The estimates are found in Table 8 and Table 9, respectively. In the naïve model without accounting for endogeneity (Table 6 and Table 8), an increase in a standard deviation in CRS decreases the probability of not working and not actively looking for work (Labor = 0) by 2.4 percentage points. At the same time, it increases the probability of being in formal employment (Labor = 3) by 3.2 percentage points. The figures for the instrumental variable models are substantially higher (displayed in Table 9). Those models instrumenting CRS with Contingency experience (Models (1) to (3)) show the probability of not working and not actively seeking work (Labor = 0) to decrease by between 20.8 and 24.0 percentage points, to decrease the probability of actively looking for work (Labor = 1) by 11.2 to 13.2 percentage points, to increase the probability of informal employment (Labor = 2) by 4.4 to 5.1 percentage points, and to increase the probability of formal employment (Labor = 3) by between 27.6 and 32.1 percentage points. The respective average marginal effect coefficients for Model (4), which uses Experience of death as instrument, have the same signs and are around one-third larger in absolute terms. When using mean religiosity (the mean value of the CRS) in the ward as an instrument (Model (5)), the signs are also the same, but the coefficients are around half the size as in Models (1) to (3). Assuming that Models (4) and (5) constitute upper and lower bounds of the true estimate, it seems that the true effect of CRS is in the region of magnitude shown for the coefficients in Models (1) to (3).

Table 8.

Average marginal effect estimates for Table 6.

Table 9.

Average marginal effect estimates for Table 7.

The instrumental variable estimates confirm that religiosity has a substantial positive effect on labor market performance. Considering the large size of the instrumental variable coefficients compared to the non-instrumented versions both in the ordered probit and the OLS estimations, it is worthwhile noting that the instrumental variable estimates are not representative for the whole population but constitute local average treatment effects. They describe the effect of religiosity on labor market performance for those whose “treatment” (religiosity) was altered by experiences of contingency.

6.2. Validity of the Instrument

The instrumental variable approach is based on the identifying assumption (Equation (7)) that Contingency experience and Experience of death do not directly or via unobserved variables influence labor market performance. I consider it unlikely that the experiences forming part of the index of contingency experience directly affect labor market performance. To substantiate this assumption, this section provides an empirical assessment of different counter-hypotheses.

Alternative Hypothesis 1.

Responses to the questionnaire items on contingency experiences were influenced by ex ante religiosity.

Religious respondents, for example, might be more likely to interpret events experienced as unexplainable, or the reported situations of incredible joy might include positive labor-market-related events, such as unexpected job offers. A similar argument would be that religion is actually the cause of contingency experiences, i.e., that religious practices produce experiences that are perceived as contingency experiences. This could, for example, be experiences of conversion, experience of the attendance of religious mega events, or anxieties caused by religious struggles (Pargament 2012; Szcześniak et al. 2020). This situation would pose an endogeneity problem in the first-stage regressions. To verify that this is not the case, all instrumental variable models are also estimated using only Experience of death as instrument. Ex ante religiosity is highly unlikely to affect reports on mortality in close social proximity. Even though identification in some of the instrumental variable models using the instrument Experience of death is weaker, the estimation results using this variable largely confirm the results of the estimations that use Contingency experience as instrument.

Alternative Hypothesis 2.

Contingency experiences constitute external shocks that produce despair. They negatively influence the propensity to engage in labor market activity.

This hypothesis would imply that labor market status and contingency experience were negatively correlated. I document the correlation of contingency experience and labor market outcomes by regressing the ordinal scale of labor market outcomes, Labor, on the four contingency dimensions. The full set of covariates is included, but the variables related to religion are omitted. Table 10 displays the results. All four dimensions of the index of contingency experience are positively correlated with religiosity (as measured in CRS) and—through religiosity, as I argue—with labor market status. It might be conceivable that there is a short-term negative effect not observed in the cross-sectional data. However, if this is the case, the effect is offset by religious coping effects in the long run (i.e., a positive effect of religiosity on labor market status).

Table 10.

Estimation results regressing labor market status on contingency experiences.

Alternative Hypothesis 3.

Income is positively correlated with better health and decreased mortality. Hence, a higher labor market status affects responses on Experience of death because of a decreased number of deaths in the family.

This would again entail that labor market status and Experience of death were negatively correlated. As documented in Table 10, this is not the case.

Alternative Hypothesis 4.

Experience of death indicates the death of the main bread winner in the household. It increases the propensity of labor market activity, particularly for women.

This hypothesis would imply that the experiences of death were particularly influenced by female respondents, who constitute 63% of the sample. Table 10 provides the correlations (conditional on the covariates) of Labor and the four dimensions of Contingency experience for the subsample of male and female respondents. The table shows that Experience of death and labor market status are not significantly correlated in the female subsample. The overall correlation is driven by the male subsample. Moreover, to rule out the possibility that similar types of household composition drive the results, controls for household composition are included in all regressions (Table 1, Panel I).

7. Discussion

The findings of this study show that individual religious intensity is more relevant in improving labor market performance than religious content (insofar as it can be proxied by religious affiliation). More specifically, I find that individual religiosity has a significant and substantial positive effect on different indicators of labor market performance. The general positive effect of individual religiosity on labor market performance is robust across a set of different specifications—even when including differentiated, context-relevant indicators of church membership and when restricting the analysis to subgroups of people not affiliated with any church and not practicing African traditional religion. Consequently, I conclude that religious affiliation itself does not affect labor market performance. As soon as religiosity is controlled for, any effect of membership in different churches disappears. Interestingly, the results point towards a positive relationship between the practice of African traditional religion and labor market performance even when controlling for religiosity—although, in this study, we cannot ascertain whether there are causal effects of African traditional religion on labor market performance.