Abstract

This paper emphasizes the role played by the sculptural tradition in the elaboration of religious narratives that today are mostly studied through texts. It aims to demonstrate that according to the documents we know, the legend of Kṛṣṇa has been built through one continuous dialogue between different media, namely texts and carvings, and different linguistic areas, Indo-Aryan and Dravidian. Taking the motif of the butter theft as a basis, we stress the role played by the sculptural tradition and Tamil poetry, two elements less studied than others, at the foundation of a pan-Indian Kṛṣṇa-oriented heritage. We posit that the iconographic formula of the cowherds’ station as the significant background of the infancy of Kṛṣṇa led to the motif of the young god stealing butter in the texts, through the isolation of one significant element of the early sculpted images. The survey of the available documents leads to the conclusion that, in the southern part of the peninsula, patterns according to which stone carvings were done have been a source of inspiration in Tamil literature. Poets writing in Tamil authors knew texts transmitted in Sanskrit, Prākrit, and Pāli, and they certainly had listened to some others to which we have no access today. But we give reasons to assume that the authors of the said texts were also aware of the traditional ways of representing a child Kṛṣṇa in the visual domain. With these various traditions, poets of the Tamil country in the later stage of Tamil Caṅkam literature featured a character they may not have consciously created, as he was already existent in the visual tradition and nurtured by the importance of one landscape animated by cowherds in the legend of Kṛṣṇa.

1. Introduction

“He loves butterHow radiant!—fresh butter in his hand(…)Blessed, says Sur, is one instant of his joy.Why live a hundred eons more?”Transl. John S. Hawley, The Memory of Love, Sūrdās Sings to Krishna.(Hawley 2009)

Thus begins and ends one of the many poems of the Sūrsāgar, an anthology whose literary elements started to be composed during the second half of the 16th century in the language of Braj (Brajbhāṣā), in the region of the same name whose center, Mathurā, is located around 100 km south of Delhi in northern India. The childhood of Kṛṣṇa, a deity born and raised in the area of Mathurā according to all the texts we know, and his love for Rādhā constitute the main focus of the Sūrsāgar’s poems. The lovely child who loves butter, the mākhan-cor, “the Butter-thief,” is the hero of an important section of the text. Since the struggle for the recognition of Hindi as a literary language in the 1920s and 1930s, during which the Sūrsāgar was used as a key tool, the Butter-thief assumed in the north of India a singular importance, as has been amply demonstrated by John S. Hawley in a book published in 1983, Krishna the Butter-thief (Hawley [1983] 1989).

Given such a modern and contemporary background, the fact that the theft of butter by Kṛṣṇa is first mentioned in Tamil poetical works from the south of India may come as a surprise. This is all the more so, since, from the period of its composition between the ninth and 11th centuries, the well-known Bhāgavata-purāṇa has been cited as the main textual source for the deeds of the young god, inspiring paintings, carvings, and texts in which Kṛṣṇa is the hero. Composed in Sanskrit, the language of an elite koine active far beyond India and presenting a continuous and elaborated narrative of Kṛṣṇa’s life, the Bhāgavata-purāṇa may have inspired much of the Sūrsāgar. However, Bhāgavata-purāṇa is far from being the first version of the story of the childhood of Kṛṣṇa. It was already told in Sanskrit in the much earlier Harivaṃśa, an appendix to the Mahābhārata dated between the second and the fourth centuries CE. Furthermore, the Bhāgavata-purāṇa was composed in a South Indian milieu, which raises another issue. Its author(s) were inspired by Tamil versions of Kṛṣṇa’s legend that were being developed since early Tamil poetic anthologies and epics from the seventh century. The theft of butter does occur in those early works, but only rarely. In the Divyaprabandham (Nālāyira Tivviyappirapantam), a collection of Vaiṣṇava devotional poems composed between the seventh and the ninth centuries however, a butter lover variously called Kaṇṇaṉ (Kṛṣṇa) or Kēcavaṉ (Keśava), etc., plays an active role. As is true for several elements of Kṛṣṇa’s narrative, the earliest Tamil poems surface as models for the stanzas of the Divyaprabandham, that, in turn, have deeply inspired the Bhāgavata-purāṇa when the latter introduced many “new” patterns into the Sanskrit corpus.

As in the case of many ubiquitous motifs of the legend of Kṛṣṇa, the role played by Tamil texts in the development of the Butter-thief figure is largely neglected, while their first inspiration remains a mystery. What was the access of the Tamil area to the legend of Kṛṣṇa? Were there versions of the Harivaṃśa or other texts, including oral versions that can only be hypothesized and were lost in the course of time? Jain texts have transmitted accounts of Kṛṣṇa’s legend that do not correspond in all details with the one recorded in the Harivaṃśa. Are they one of the channels through which composers of the Kṛṣṇa story in Tamil got access to Kṛṣṇa-flavored stories? Or, at least, do they give witness to one of the links with earlier texts that are now lost? How is it that so many episodes of the legend of Kṛṣṇa made their appearance in the Tamil South and not in Sanskrit or another Indo-Aryan language? The Butter-thief is, in fact, one of the many motifs that first emerged in Tamil literature. Kṛṣṇa as a flautist, Kṛṣṇa stealing the clothes of the gopīs, Kṛṣṇa defeating a calf-demon or a heron are other instances of the creativity of Tamil poetry in the Kṛṣṇa-devoted realm.

But Tamil texts are not the only evidence neglected with regard to Kṛṣṇa’s Bhakti stories. The role the visual tradition played in the development of the legend of Kṛṣṇa has still to be fully recognized. This essay proposes that art—only stone sculptures survive, but paintings or other movable media like terracottas or ivories may have existed—should be seen as the missing link between these two text-worlds: Northern and southern.

For the south of the peninsula, the patterns designed for depicting Kṛṣṇa on carvings provided one source of inspiration that was as important as were texts to southern poets. Certain motifs found in the early, North Indian carvings do not have clear parallels in the early northern texts, while later South Indian poems focus on them in unambiguous detail. This paper argues that the depiction of the cowherd village on the earliest stone carvings was one such motif; it would become the basis for inventing the trope of the theft of butter in poems composed in the South. The thief of butter was, in addition, connected in these early poetic anthologies with lovers as thieves of another kind. Through this complex interplay of sculpture and text emerged a new and irresistible portrait of Kṛṣṇa that was destined to have a remarkably long life in both northern and southern circles.

2. The Butter-Thief as a Northern Motif

Having sold butter, at the time of the return—does one remember?—On that day,When the flowers of jasmine densely flourished, near the small river of a wood,With your eyes similar to tender young mangoes, my heartYou took to bind (me) and rule on the battlefield: what if you are not but a thief of a unique kind?Kalittokai 108.26–29.1

The Sūrsāgar seems to anticipate representations of Kṛṣṇa familiar today. An example is the poem that frames this paper, given in the accurate translation of J.S. Hawley (Hawley 2009, p. 52). Here is the thief of butter:

(…)Crawling on his knees, his body adorned with dust,Face all smeared with curd,Cheeks so winsome, eyes so supple,A cow-powder mark on his head,Curls swinging to and fro like swarms of beesBesotted by drinking drafts of honey,At his neck an infant’s necklace, and on his lovely chestThe glint of a diamond and a tiger-nail amulet.Blessed, says Sur, is one instant of his joy…

In many other verses of the Sūrsāgar, the deity takes butter, eats it, or is featured stealing or having stolen it.2 This thief is still the hero of scenes played in the area of Mathurā, of popular images, songs, and videos in the whole of India and abroad, following that tradition that must have lain behind the composition of the Sūrsāgar.3

The visual aspect of Kṛṣṇa’s occurrences in the Sūrsāgar is striking. If songs, poems, plays, and videos are related to oral modes of transmission, performances must also be included among the possible sources of visual inspiration for many of these works, and poetry featuring the Butter-thief is no exception. These kinds of vignettes are the visions of a poet. As in the poem just cited, the figure is sharply delineated; colors are suggested (curd, powdered cow dung, bees),4 as well as the radiance of the skin (radiant, dust, cow dung-powder, swarms of bees, glint of diamond); signs are given that indicate a young age (smeared with curd; winsome; cow dung mark; infant’s necklace; tiger amulet). The poet makes us see a god he describes in all his details—position, hairdo, ornaments, actions, things held by the deity—as the source of wonder for him. In doing so, he privileges the sense of sight over others.5 The poet does not touch, smell, or taste this deity, nor does he listen to him.

To privilege sight in a corpus to be performed may seem too obvious for those who study Bhakti texts, as natural as it may be for the devotees themselves. However, in the Tamil Bhakti corpus, smell is of notable importance, and sound—above all the music of the flute played by Kṛṣṇa—is another privileged sense. With regard to the episode of the butter theft, however, it is the visual components that are of distinct importance, from the first texts that were composed in the South, to the northern variations in the Sūrsāgar and other texts.6 For the moment, let us stress that the Butter-thief vignette is one of those that are clearly delineated in texts and that its characteristics and details are closely related to the iconographical corpus seen in sculptures. The bulk of this corpus has been carefully collected and will be presented after an overview of the history of the motif in texts.7

The textual corpus that preceded the Bhakti poet-saints of North India who, from Mirabai (1498–1546) to Sūrdās, describe Kṛṣṇa as eating the butter he has stolen has long been identified. Canto 10.9 of the Bhāgavata-purāṇa, which focuses on the episode of the thief of butter, has been revealed as the first and foremost of their sources, if not the only one. As this Purāṇa has been an object of fierce debate regarding its date and place of composition, we refer the present reader to previous works for its South Indian origins. Its author(s) knew Tamil poems and were inspired by South Indian realities that were not accessible in northern India. Its composition in a deliberately archaic Sanskrit may have been started at the end of the ninth century and completed at the beginning of the 11th.8

These two limits are crucial to our understanding of the way the legend of Kṛṣṇa has been composed and diffused in the Indian peninsula, as well as in some parts of Southeast Asia. The Bhāgavata-purāṇa popularized some of Kṛṣṇa’s pranks that were not part of the literature in Sanskrit or other North Indian languages predating this Purāṇa, but were alluded to in the Bālacarita, a play composed in South India around the seventh to ninth century—that is, at the beginning of the range of dates given for the composition of the Bhāgavata-purāṇa. The thief of butter appears in the Bālacarita, which revolves around the childhood of Kṛṣṇa, and it is vividly depicted in the Bhāgavata-purāṇa. In fact, all the earliest known texts evoking this mischief are from South India. How was such a connection established? One explanation concerns the fact that this trick falls within the childhood of the god or a part of his life that was not originally included in the earliest texts, and those sections were the most reworked and interpolated over the course of time in all parts of India.

The two fundamental texts in which the biography of Kṛṣṇa is delineated are the Mahābhārata and the Harivaṃśa, the latter being commonly defined along with the primary sources as a khila (appendix or “afterthought”) of the Mahābhārata. The older Mahābhārata (fourth century BCE–fourth century CE) knows very little of the infancy of the god, while it is a main focus of the Harivaṃśa (second–third century CE). This distinction sanctions the recognition of a transformation from the Kṛṣṇa of the Mahābhārata into one of the many avatāras of the Hindu Viṣṇu—even if with a special status amongst the others—by the time of the Harivaṁśa. Kṛṣṇa is an adult figure in the epic, while the Harivaṃśa describes the birth, childhood, and adolescence of the god. In doing so, this text provides a biological model of the relation between the supreme deity of the Mahābhārata and the Kṛṣṇa of the Harivaṃśa, whose supplementary arms growing during his puberty provide a striking illustration of the process.9

Such a division of roles between the texts accounts for the absence of a Butter-thief in the Mahābhārata. Conversely, a child fond of butter seems ideal to be featured in the Harivaṃśa in which milk products are very present from the first mention of the cowherd’s village where the child Kṛṣṇa is to be raised. In Chapter 49 of this text, 1498–1546, Nandagopa and Yaśodā, the foster parents of Kṛṣṇa, go back to their village with Kṛṣṇa as baby:

“There are many open spaces, happy and strong people are around; there are a lot of ropes in the station and the sound of the churning is heard from every place.Lots of buttermilk are around and the earth is wet with curd. Milkmaids create sound with the noise coming from the churning sticks that they stir.”(Harivaṃśa 49.24–25)10

In the following chapter (HV 50), Kṛṣṇa performed his first miraculous deed by upturning a cart. Nandagopa sees the chariot lying upside-down together with many broken pots, presumably these were vessels containing milk-products.11 However, nowhere in the critical edition of the Harivaṃśa is Kṛṣṇa’s fondness for butter, or for yogurt, to be found—much less his theft of them. In chapter 51 that follows the two chapters in which milk-products are so present (49 and 50), even though the infancy of Kṛṣṇa and his brother is vividly evoked12—the two boys play pranks on the cowherds in their homes; they are covered with dust and other matter including cow dung, that will accompany them till Sūrdās,13—but butter is not mentioned.

“Both had long arms that looked like snakes. They moved everywhere. With dust on their bodies, they shone like baby elephants.Sometimes their bodies were covered with ashes and sometimes with cow dung. They ran around like the sons of fire god.As they crawled on their knees in some places, they looked enchanting. They went to cowsheds for playing and their bodies were covered with cow-dung.Both were blessed with prosperity (śrī). They gave great pleasure to their parents. Here and again, they would be mischievous with people and laugh.Both roamed around the camp (vraja), doing various pranks. Nandagopa was unable to control these two.Once, Yaśodā became very angry with the lotus-eyed Kṛṣṇa. She brought him by the side of a cart and she summoned him again and again.”(Harivaṃśa 51.8–13)14

In this passage, the grammatical dual declension is extensively used for two brothers who are defined as one body divided into two (HV 51.4). These two are so naughty that the foster parents decide to get tough with them. But when Yaśodā does what she must, only Kṛṣṇa is mentioned. He is tied to a mortar with which, eventually, he uproots a pair of arjuna trees. Here again one cannot find any mention of butter in the critical edition of the Harivaṃśa. But that is not the case with the southern versions of the text, in which, in between the stanzas 12 and 13 of this same chapter 51, the episode of the theft of butter makes its appearance. The passage is developed in what became two appendices in the critical edition (9 and 9A, 33 and 52 lines, respectively). Similarly, the southern versions of the Mahābhārata itself mention the theft of butter by Kṛṣṇa (see Sabhaparvan, app. 1.21, l. 767–769), making clear that the whole that comprises the Mahābhārata together with the Harivaṃśa has been modified in South India to include a series of mischievous acts in which butter plays a major role.

These southern versions of the Mahābhārata and Harivaṃśa are known through manuscripts written in Grantha or Telugu scripts and collected in the south of India. They are considered to be later than the critical edition for many convincing reasons. In the southern versions of an epic that consists of the Mahābhārata and its khila, Kṛṣṇa wanders from one house to the other, stealing milk, yogurt, and butter, breaking the pots where they are kept and sharing their contents with his friends. These narratives are very similar to the references to the butter-fondness of Kṛṣṇa at the end of Act 1 and the beginning of Act 3 of the Bālacarita15 and to descriptions in chapters 10.8 and 9 of the Bhāgavata-purāṇa, in which the influence of the Divyaprabandham composed in Tamil is particularly conspicuous. In these southern accounts—whether they are composed in Tamil, Prākrit, or Sanskrit—Kṛṣṇa is tied to the mortar with which he uproots the arjuna trees, because he has stolen butter. The narrative thus presents a logic slightly different from that which is at work in the earliest northern versions of the Mahābhārata and Harivaṃśa. In those, Kṛṣṇa is punished because he was naughty; in the later, southern texts Kṛṣṇa is punished because of a specific misdeed, namely the theft of butter. The theft of butter is invoked in place of a series of pranks, in which it might have been considered as a grand finale. But the earliest Mahābhārata and Harivaṃśa are not the sole texts in which the butter-theft is missing. Furthermore, its absence in these earliest versions of the epic appears more problematic than it seems if we look towards the sculptural tradition. But first let us consider additional texts to see what additional clues they might provide.

Nothing is said about butter, butter-thievery, etc., in the Buddhist Ghata-jātaka (Jātakas no 454) telling the story of Kṛṣṇa as one of the previous lives of the Buddha in this collection of narratives belonging to the Pāli Tipitaka of the Theravādins. The full story is told in the commentary which was composed around the middle of the fifth century, by a Sinhalese monk.16 Nor is anything about a butter lover mentioned in the Jain Antagaḍadasāo, the eight of the 12 Aṅgas of the Śvetāmbara canon of the composed in Prākrit (ardhamāgadhī) around the fifth century CE.17 This text tells the story of Kṛṣṇa’s brother Rāma, presented there as the eighth son of Devakī and a disciple of the Jain Tīrthaṅkara, Ariṣṭanemi. We also look in vain for the butter-theft in the Viṣṇu-purāṇa and the Brahma-purāṇa, which contain the earliest known Purāṇic version (the two texts are almost identical) of the childhood of Kṛṣna (fifth–sixth century). And, finally, nothing of that sort appears in the pierre de touche of the critical editions of Mahābhārata and Harivaṃśa, the Bhāratamañjarī, a versified summary of these two texts composed around the middle of the 11th century in Kāśmir.

According to this collection of texts, a fondness for butter was not a characteristic of Kṛṣṇa in the early period in northern India. The Sanskrit and Prākrit traditions from this area seem to ignore this episode until the spread of the Bhāgavata-purāṇa, after the 11th century. Still, there is in North India another type of evidence that may attest to the existence of a Butter-thief from at least the fifth century: Some of the first known representations of Kṛṣṇa as a child in sculptures.

3. First Sculptures: North India

The iconographical evolution of Kṛṣṇa parallels that of the texts. First, the Kṛṣṇa of the Mahābhārata is represented as a deity with four arms and his characteristic attributes of mace, disk, and conch, when depicted as the “ordinary form of the god” whom Arjuna longs to see after having been granted the vision of the cosmic deity in the Bhagavad-gītā.18 During the second to fourth century CE, this iconography becomes identified as that of the Hindu Viṣṇu, a deity who is the source of all the others, including members of the Vṛṣṇi “family” of Kṛṣṇa (Schmid 1997, pp. 71–77; Couture and Schmid 2001). From around the Gupta period (fourth–sixth century), Kṛṣṇa is featured with the iconography corresponding to the story told in the Harivaṃśa as a child who fights demons with two bare hands and no weapons.19 During the same time period, in regions where inscriptions dated in the Gupta era are found, the Hindu Viṣṇu emerges with some of his avatāras. Then, Kṛṣṇa takes center stage defeating the bird-ogress [Pūtanā], upturning a cart, fighting the nāga Kāliya, the ass demon Dhenuka,20 the demonic Pralamba, the bull Ariṣṭa, the horse demon Keśin, lifting up Mount Govardhana—and, it can be considered, stealing butter.

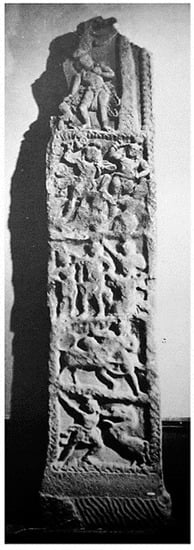

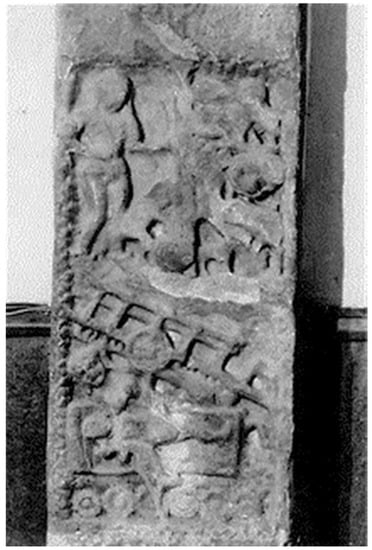

Two stone reliefs depicting a child with one hand in a pot are known from two North Indian sites very distant from one another: Vārānasī (Uttar Pradesh, Figure 1) and Maṇḍor (Rajasthan, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Churning of Butter, fourth–sixth century. Vārānasī, Uttar Pradesh. Sandstone. Bharat Kala Bhavan (BKB 180).

Figure 2.

Doorjamb with Exploits of the Young Kṛṣṇa, fourth–sixth century. Maṇḍor, Rajasthan. Sandstone. Jodhpur Museum (photo by courtesy of the American Institute of Indian Studies).

Figure 3.

Doorjamb with Exploits of the Young Kṛṣṇa, fourth–sixth century. Maṇḍor, Rajasthan. Sandstone. Jodhpur Museum (photo by courtesy of the American Institute of Indian Studies).

Figure 4.

Detail of Figure 2: Churning of the Butter.

Identified as representations of the theft of butter, they present a strikingly similar iconography.21 Dating between the end of the fourth and the sixth century, they appear to be older than the first known texts in which the motif emerges.

A woman stands on the left, facing the viewer. She is busy churning the contents of a big pot placed at her feet with a rope; below her legs, a kneeling child raising his face towards her and in the direction of the viewer, inserts a hand in the pot. On the Vārānasī fragment, two other women carry pots on their heads in the background; these women may also have been on the Maṇḍor relief (Figure 2), but the space above the churning scene is worn, and the carving is no longer discernible. Today, to the right of the churning scene, cows with their calves fill the space from the bottom to the top of the panel. On the Vārānasī piece, it is possible to see that the churning rope is attached to a tree, whose appearance is the same as the one given on contemporary or slightly later reliefs of the arjuna trees between which Kṛṣṇa crawls in the episode with the mortar.

The style of the two reliefs is not similar, nor are the techniques, as the Maṇḍor piece is carved in very low relief on a flat and tall stone, while the Vārānasī piece is much more deeply sculpted. The Maṇḍor scene is sculpted with two or three22 other episodes of the Kṛṣṇa legend in panels on the same stone, and five other episodes featuring Kṛṣṇa as the hero appear on another stone with which it forms a pair (Figure 3). Viewed together, the whole ensemble of sculpted narrative panels confirms the identification of the butter-churning scene as related to the legend of Kṛṣṇa (Figure 4). These carvings present a coherent narrative cycle with Kṛṣṇa as a main protagonist; if the relief from Vārānasī had been part of such a cycle, the example illustrated in Figure 1 would be the sole scene to have survived.

The iconography of the two sculptures is so close it raises questions about the diffusion of the motif. Was it linked to lost texts? A woman churning while a young boy inserts his hand into the pot as others look on or milk cows constitutes the main element of the scene The child may be qualified as a kind of foreground, or as a detail of the main subject of the scene, which is the churning. The characters, their attitude, etc., match the description of the cowherd village in the Harivaṃśa, where milkmaids churn away. However, there is no specific verse in the Harivaṃśa, the Viṣṇu-purāṇa/Brahma-purāṇa, nor in any text predating the Tamil sources that mentions a little boy. Since these two carvings are so similar, whatever their textual source of inspiration, be it oral or written, would have included a theft of butter from a pot placed on the ground, while a milkmaid is engaged in churning.

4. The Northern South: Karnataka

At the close of the period to which the North Indian reliefs are attributed, namely the end of the sixth century, the same iconographic formula started to be used in Karnataka, first in caves, then a little later at the built temples of Bādāmī and the nearby site of Paṭṭadakal. These two sites are situated in an area that represents a form of northern South, where North Indian culture, including Indo-Aryan texts, met a Dravidian realm. Bilingual inscriptions in Sanskrit and old Kaṇṇaḍa dated from around the late sixth or the early seventh century have been found in the same zone.23 Many representations of Kṛṣṇa are found at these sites, which were under the control of the Cāḷukya dynasty at the time they were made. Exploits of a young Kṛṣṇa, one after the other, have been carved in narrative relief friezes on the lintels of Caves II and III of Bādāmī (Figure 6), on the base of a structural temple called the Upper Śivālaya of the same site (Figure 7 and Figure 8), on pieces today reused in different parts of the same site (Figure 9), and on interior pillars of the Kāśiviśvanātha Temple at Paṭṭadakal (Figure 10).

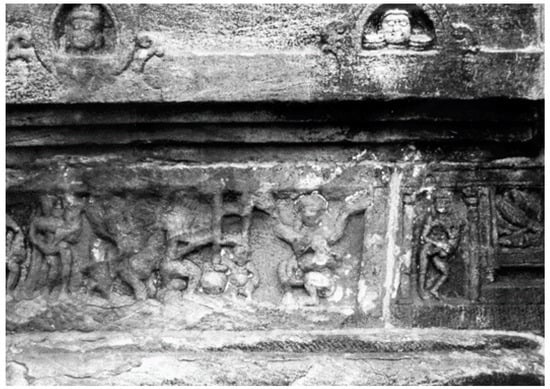

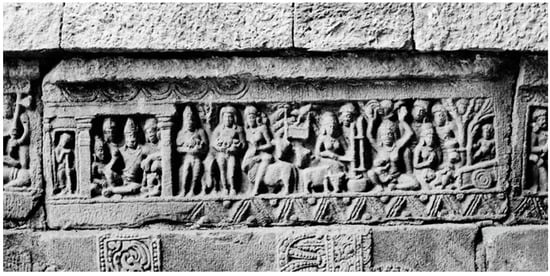

Figure 6.

Exploits of the Young Kṛṣṇa (left to right): Churning with the “Butter-thief,” Slaying of Pūtanā, end of the sixth century. Interior lintel, Cave II at Bādāmī, Karnataka.

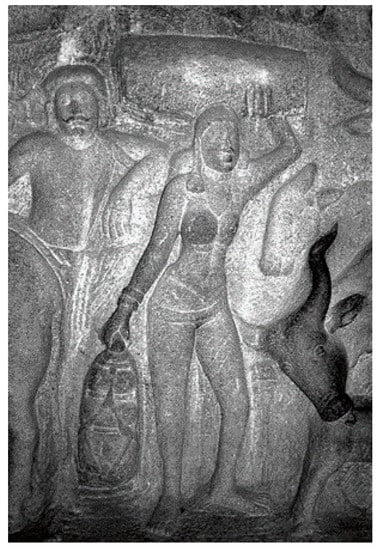

Figure 7.

Exploits of the Young Kṛṣṇa (left to right): Arrival of Kṛṣṇa at the Cowherd Village, Churning with “the Butter-thief,” Slaying of Pūtanā, sixth–seventh century. Base of the western side of the Upper Śivālaya, Bādāmī, Karnataka.

Figure 8.

Exploits of the young Kṛṣṇa: Churning without the “Butter-thief,” Arrival of Kṛṣṇa at the Cowherd Village, the Goddess, Transfer of the Baby to the Cowherd Village/Killing of Kṛṣṇa’s Sister, sixth–seventh century. Base of the southern side of the Upper Śivālaya Temple, Bādāmī, Karnataka.

Figure 9.

Exploits of the Young Kṛṣṇa (left to right): Arrival of Kṛṣṇa at the Cowherd Village, Churning without “Butter-thief,” Slaying of Pūtanā, Arjuna Trees Episode, sixth–seventh century. Carving from Bādāmī Fort, possibly transferred from the Upper Sivalaya Temple, Bādāmī, Karnataka. Bādāmī Museum.

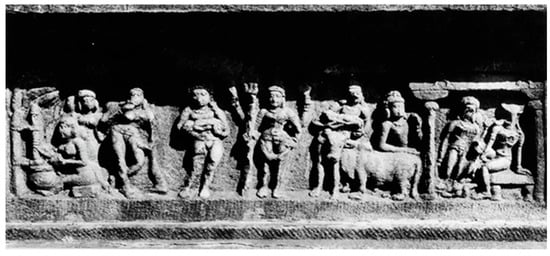

Figure 10.

Exploits of the Young Kṛṣṇa (upper register, left to right): Churning with the “Butter-thief”, Cart Episode, Fight against a Heron, Arjuna Trees Episode, eighth century. Kāśiviśvanātha Temple, Paṭṭadakal, Karnataka (photo by courtesy of Dominic Goodall, EFEO).

In some of these friezes, a toddler is depicted inserting his hand in one pot churned by female figures, as part of a series of episodes that includes the death of Pūtanā, the overturning of the cart and the breaking of the trees (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 10). In others, a simple churning, without the young boy, is figured (Figure 8 and Figure 9). We will come back to this point. The chronology of the events followed in these series does not correspond exactly with the narrative in texts where the Butter-thief makes his appearance, whether they are composed in North Indian languages or in Tamil. Such a chronology is uncertain at Maṇḍor where the episode of the breaking of the trees is not represented (was it supposed to be on the blank band of stone?), but in textual sources, Kṛṣṇa always (1) sucks the poisonous breast of Pūtanā, (2) steals the butter, before being (3) tied to the mortar with which (4) he uproots the arjuna trees. In the first carvings found in Karnataka, the episode implying butter can be depicted before the god sucks the poisonous breasts of Pūtanā.24 Still, Pūtanā, the mortar and the uprooting are associated in the carved tradition as in the textual one. Such association requires further comment.

All the episodes from the childhood of Kṛṣṇa in the reliefs from Maṇḍor and the northern Gangetic plain of the fourth–sixth century and from sites in Karnataka of the late-sixth century correspond to one passage of the Harivaṃśa. For the period of time to which these carvings have been assigned, we have seen they are already rather numerous. In Karnataka, the Slaying of Pūtanā relates to different scenes than at Maṇḍor and Deogarh in Madhya Pradesh (Figure 5), where the Pūtanā episode is conflated with that of the cart. There, Kṛṣna is depicted lying on the cart when Pūtanā comes as a woman who becomes a bird that Kṛṣṇa strangles (Figure 5), or Pūtanā comes as a bird and becomes a woman whose breasts Kṛṣṇa sucks (Maṇḍor, Figure 4), as is told in the Harivaṃśa. At Paṭṭadakal, on the other hand, three discrete episodes are represented: The cart, a combat against a bird very different from the crow (śakunī) that is the form of Pūtanā in the Harivaṃśa and the earlier representations, and an ogress whose breasts Kṛṣṇa sucks. In fact, the episode of Pūtanā has been expanded there. Following the accounts composed in North Indian languages and the corresponding carvings, J. Hawley (Hawley 1987) has demonstrated how the story of the Harivaṃśa has been split into two in the Bhāgavata-purāṇa. In a previous publication, we have elaborated on the “shadow-motifs” that show how Tamil texts and stone representations of the far South are the missing link of the story (Schmid 2013).

Figure 5.

The Episode of the Cart and Pūtanā. Fifth–sixth century. Deogarh, Madhya Pradesh. National Museum, Delhi.

The case of the Butter-thief is different from the Pūtanā episode, but it is analogous in terms of the presence of shadow-motifs, that result from transfers of an original story. The process of formation of the transfer-motif is this: One original motif is recorded in Sanskrit narratives; it is then split into two in Tamil texts. This split gives rise to a second motif distinct enough from its source to be considered a different one, even if, historically speaking, it is the “double” of one previously-born motif. The double-motifs of the legend of Kṛṣṇa were transmitted in Sanskrit with the Bhāgavata-purāṇa, which drew inspiration from Tamil poetry. The heron “Baka” of the Bhāgavata-purāṇa outlined after the bird shape of the ogress Pūtanā in the early Harivaṃśa is one example of this process.

Iconographic formulas are key to such splits. On the one hand, from the Harivaṃśa to the Viṣṇu-purāṇa, the evolution of the narrative can be clearly followed with whole verses of the Harivaṃśa used in the Viṣṇu-purāṇa and with literary formulas common to these two texts. At the time that these texts were circulated, there were also iconographic formulas in circulation throughout a rather vast territory. Those visual patterns were used like textual stanzas: From one site to the other, the iconography exhibits variants, but in readily recognizable formulas. The churning of the butter as seen at Maṇḍor, Vārānasī, and northern Karnataka before the end of the sixth century is one such formula. With a child introducing his hand into a pot placed on the ground, this visual formula presents details that are not included in any earlier or contemporary known texts. These sculptures may express the creativity of a visual world that does not necessitate that we propose an underlying textual source. Before Tamil texts plausibly dated to the sixth or seventh century, no known text includes a description of Kṛṣṇa taking the content from a pot that was in the process of being churned. Still, those details of the images were part of the construction of the legend of Kṛṣṇa from Rajasthan in the north, to Vārānasī, eastwards (or the reverse) and north of Karnataka, to the south of the peninsula. At Bādāmī and Paṭṭadakal, the formula is included in iconographical series at sites where carvings may have been made in connection with South Indian texts or inspired by a tradition of carvings whose origin was situated in North India, as indicated by the identification of the two early reliefs of Maṇḍor and Vārānasī with representations of a Butter-thief as early as the Gupta period.

5. Carvings and Texts: Oral Transmission and Folk Culture

The issue of the difference between carvings and known texts might lead us to posit a theoretical “folk” culture with stories in North Indian languages that have not been preserved in any textual form. The stone carvings that have survived the ages would be considered evidence for their existence. Separate from the world of texts composed in Sanskrit (a language used by and for the elite), folk motifs in the northern and central areas of India would either have been introduced to South India where they influenced the development of the figure of Kṛṣṇa, or they would have been an ancient pan-Indian element. Associated with the world of herdsmen, the motif of a theft of butter would be but one of the themes of folk or “popular” (Hardy 1983 pp. 93–95) origin which found a way into texts of the elite first through Tamil compositions, more specifically Bhakti Tamil hymns. Composed in a vernacular and thus locally more accessible language, the Tamil poems would have been inspired by lost texts, of a similarly accessible, popular nature, whose existence may be attested by the stone carvings made from the fourth century in the North. As most Tamil poems belong to a Bhakti corpus largely supposed to have been composed for a broad-based audience, and by authors said to cover a broad social gamut, they may well have been responsible for introducing folk themes into a religious corpus.

Even if some aspects of this hypothesis remain valid to our eyes, a critical examination of the first known stone representations raises several issues about their presumed textual underpinnings. Can stone carvings, usually patronized by rather well-off people, be considered clues to the existence of folk culture? Were the Bhakti Tamil hymns composed for a non-literate audience by poets following “popular” trends? Was the contrast between texts produced for and by an elite, be it Brahmanic, Buddhist, or Jain, and other texts associated with a folk world and supposed to have been transmitted orally so sharply delineated?

For our part, we are more inclined, with others, to think of the written form taken by texts in India as belonging to an environment where texts were recited, discussed, debated, and corrected as far as we know in the ancient world as they are still today. What is a “folk” world or a “popular” motif remains to be defined, but we doubt it is the source of the earliest evidence regarding the love of butter which underlies the Butter-thief figure. The first texts associating deities and the love for butter highlight links with literary and religious figures that are not considered to belong to a folk world, like the Vedic Agni, who under a child form devours the oblation of butter “with kisses on the ladle’s mouth” in Ṛgveda 8.43,25 and the Kṛṣṇa of the Bhagavad-gītā to whom Arjuna says: “With your firing mouths you lick all the worlds while devouring (them)…” (11.30ab).26 There are links between the Vedic god of fire who devours the oblation and Kṛṣṇa in the Harivaṃśa; he is called Keśava, the “Hairy one,” which is also one of Agni’s names, compared to the son of the fire (HV 71.48–50), and qualified as god of the dark trail (kṛṣṇavartman) that is the fire itself, as has already been commented upon (Couture 1991, pp. 34–40). Such filiation reminds us that the concept of a divine child who eats butter and a god who devours everything, as manifest in the image of Kṛṣṇa stealing the butter, is deeply associated with a North-Indian cultural milieu. For this reason, it is unlikely that the figure of the Butter-thief in Tamil texts can be explained as having derived from a so-called folk background.

6. First Mentions of the Butter-Thief: Tamil Poems

The earliest known mention of a theft of butter by Kṛṣṇa is found in the Cilappatikāram (Cil.), usually called an “epic,” and it presents striking parallels with a whole section of an amorous anthology of the Caṅkam corpus, the Kalittokai. These two Tamil poetical works are today considered to have been composed at a crucial time that saw the end of Caṅkam literature, which is the most ancient genre of Tamil literature, secular in nature—except for the Paripāṭal to which we will return later— and dating to the fourth century BCE to fifth century CE. This period also witnessed the emergence of the first Bhakti texts: The Śaiva Tēvāram and the Vaishnava Tiviyappirapantam, or Divyaprabandham, to use its more famed Sanskritized written title (TP; sixth–ninth century). Cilappatikāram is not considered part of the Caṅkam corpus, even if from a linguistic point of view it is closer to this corpus than to the Bhakti one. Its form, that of a long narrative poem drafted to demonstrate the power of karma in a Jain environment, reflects other concerns than the ones expressed in Caṅkam. Distinct from Caṅkam literature by their morphology, syntax, vocabulary, and meter, the Bhakti texts were composed in a very different spirit, as they are hymns in honor of deities who rarely appear in the Caṅkam corpus, other than the Paripāṭal. In the early Caṅkam anthologies, references to a Butter-thief motif are elusive and scarce; they become more particularized in the karma-inclined Cilappatikāram, where Kṛṣṇa is the one who steals the butter, whereas the later Divyaprabandham is laced with stanzas in which a butter-loving Kṛṣṇa appears. Without presuming that Cilappatikāram is earlier than the Kalittokai, we first present its data as the motif is mentioned there in a way that helps to discern how it could be linked to the earlier Caṅkam anthologies. Dated to the seventh century at the latest, Canto 17 of Cilappatikāram tells of the child Kṛṣṇa, most plausibly for the first time in Tamil literature together with the Kalittokai, of which a presentation will follow.27

6.1. Cilappatikāram

The Cilappatikāram tells the story of Kaṇnaki, the chaste wife who cursed the Pāṇḍya king for having had her husband Kovalaṉ killed, because he mistakenly held Kovalaṉ responsible for the disappearance of one anklet, a cilappu, after which the work got its title, The Story of the Anklet. The poem consists of three parts, each centered on one theme and one place, and thirty cantos, some of which focus on a deity, such as Indra, the goddess, Kṛṣṇa and Murukaṉ. The action of Canto 17 is staged in a cowherd village. Milkmaids, who have welcomed Kaṇṇaki on her way to see the Pāṇḍya king, sing in honor of Māyavaṉ or Māyōṉ, the Tamil name of Kṛṣṇa, one of the forms of Tirumāl, the Tamil Viṣṇu. In their songs they combine the churning of the ocean, the theft of butter and the three steps of Viṣṇu. The stanza where the god steals the butter from a pot occupies the central strophe of a cluster of three. The three of them are necessary to understand this crucial passage:

Lord of the color of the sea! Once long ago you churnedThe belly of the sea with the northern mountainAs a churning stick, and the serpent Vāsuki as a rope.Your hands that churned are the hands Yaśodā boundWith her churning rope. Lord with a flowering lotus in your navel!Is this your māyā? Your ways are strange!

He is the supreme being.” Thus the immortals adoredAnd praised you. You devoured the entire universeThough hunger does not trouble you. Your mouthThat devoured is the mouth that licked the butterStolen from the hanging pot. Lord with a wreath of rich basil!Is this your māyā? Your ways are strange!28Tirumāl whom the host of gods adoreAnd praise! You strode the three worldsWith your two red-lotus feet to rid them of darkness!Your feet that strode are the feet that pacedAs the Pāṇḍavas’s envoy. O Narasiṃha! Destroyer of foes!Is this your māyā! Your ways are strange!29(transl. Parthasarathy [1993] 2004, p. 177, emphasis added)

The first and the third stanzas allude to two cosmic deeds of the deity, the churning of the ocean and the Trivikrama avatāra of Viṣṇu. Between them, the stanza where the Butter-thief made his appearance alludes to a cosmic feast of the god who swallows the entire world. Each exploit finds an echo in the terrestrial realm. The churning of the cowherd echoes the one of the ocean, the butter eater replicates the vision of Arjuna in the Bhagavad-gītā, and the steps of Viṣṇu resonate with the paces of the adult Kṛṣṇa of the Mahābhārata. The levels of the cosmic and mundane deeds are intertwined in a process destined to become typical of the Tamil Bhakti corpus. Other correspondences are staged here. The adult form and the child form are paired in the first two stanzas, and the avatāra of Kṛṣṇa is the main topic of the three strophes. Also, the link established with Trivikrama as a dwarf who becomes a giant corresponds to an explanation of the passage of the child form to the adult one, of the terrestrial incarnated level to the cosmic one, that is explicitly drawn in the Harivaṃśa where the growth of the child Kṛṣṇa is paralleled with the divine growth of the dwarf form.30 Belonging to these many levels, the butter churned in the cowherd village and eaten by Kṛṣṇa is also the amṛta churned from the ocean and devoured by the god.

These Cilappatikāram stanzas come at the end of the canto, but they were already foreshadowed at the beginning, when the cowherd’s settlement is described in detail, with numerous allusions to curd, milk, butter, and churning. The cowherds have to supply butter to the Pāṇḍya king, but the churning turns to disaster:

“…Today it is our turn (to give) butter” said Aiyai,having called her daughter, taking churning rope and churning-stick,There appears the old milkmaid.31 (…)

In the pot the milk has not curdled,from the innocent eye of the globular humped bull, water comes, oozing,something terrible will come.The fragrant butter from the hanging pot (uṟi) has been eaten,it does not melt, it diminishes, (…)In the hanging pot (uṟi), the butter does not melt!32

The cowherds try to neutralize the bad omen of the milk that does not curdle, by calling the god who plays the flute with their songs and dances.

The churning functions as a hinge between the different levels of reality. It is associated first with the god summoned with a song who accompanies the dances, and then with “The king of kings, the Cēraṉ” said to have “churned the ocean” (Cil. 17.31.3–4), and it comes again in the group of three stanzas in which Kṛṣṇa eats the butter. It links the divine deeds (“Māyavaṉ has churned the ocean with the serpent-rope”, Cil. 17.20.1), the model of the king (the Ceraṉ), and the everyday work of cowherds (“Your hands that churned are the hands Yaśodā bound/With her churning rope.” Cil. 17.32.3–4). Two remarks here allow for following the evolution of the motif.

First, the localization of the episode in the South is clear thanks to the uṟi, this specific pot containing the butter that Kṛṣṇa licks. This type of vessel is typical of the Tamil South, and as such it is not represented in the earliest carvings from North India, nor in the early Karnataka ones. Second, the stanzas express a relation between a Kṛṣṇa-child becoming an adult Viṣṇu that corresponds with a stage of evolution of Vaishnavism similar to what appears in the Harivaṃśa.

For the moment, we can conclude that the Tamil stanzas where the motif of the Butter-thief appears were carefully composed along preoccupations first found in the context of the Harivaṃśa, one text that emerges as a source of inspiration for this Cilappatikaram canto. But it is clear that many elements do not come from the Harivaṃśa, starting with a thief who steals what is inside an uṟi. Is it possible to find another inspiration for a motif that assembles butter and uṟi, thievery and a kind of hunger? Tamil texts contemporary to or pre-dating the composition of Cilappatikāram 17 may provide some explanation.33

6.2. Caṅkam Literature

During the period when the first Bhakti texts started to be composed, probably around the sixth to seventh century, the Caṅkam corpus began undergoing an important anthologization process, probably under the influence of an increasingly important written world. In the earliest stratum of the corpus available to us today, assigned to around the first to third century, butter was not specifically associated with Kṛṣṇa for one main reason: The rare allusions to Kṛṣṇa are cryptic and debated, while his brother Balarāma seems to have been popular, as is notable in the Paripāṭal, an anthology that belongs to the later stage of the Caṅkam and contains echoes of the Harivaṃśa.34 Such scarcity of the elements associated with the legend of Kṛṣṇa in the early Caṅkam makes Canto 17 of Cilappatikāram, which is contemporary to or a little later than the late stage of the Caṅkam corpus (sixth century), the first known evidence of many of the “southern” motifs of this legend. These are episodes whose origin is situated in the south of India from which they spread, such as the stealing of the gopīs’ clothes, or episodes that seem to exclusively belong to South India, such as the breaking of the kuruntu tree,35 to take two instances that knew a very different destiny. These motifs are numerous enough in Cilappatikāram 17 to allow us to consider this text as one of the first examples of a narrative developed in a southern milieu devoted to Kṛṣṇa, distinct from the northern ones.36 In such a configuration, the folk character of this milieu whose supposedly oral nature would allow for its texts to be constantly reworked and to possess an openness quality, distinct from the more secluded specificities of an elite literary corpus, is used to explain the almost complete absence of Kṛṣṇa in the Caṅkam corpus,37 whose specificities would have prevented a folk Kṛṣṇa-bhakti movement from appearing on too literate a scene.38 Following such reasoning, we find ourselves on the same trail as the one leading to folktales developed around the figure of Kṛṣṇa that inspired early carvings in northern India. The earliest known sculptures and the earliest known texts would be two different expressions of the same folk milieu.

By contrast, butter and churning do appear in the Caṅkam corpus. In the older romance anthologies and in the Puṟanāṉūṟu of the epic genre, of which some parts are earlier and some later, but overall quite safely attributable prior to the fifth century, butter connotes abundance and riches. It is a mark of prosperity, and as such it is desirable. The products of the churning of the ocean, among them Śrī herself, are related to a butter used to enhance beauty, to bathe with, to worship gods, and to celebrate.39 In Nāṟṟiṇai 40, a young mother takes a bath in ghee (butter);40 the association of ghee/butter and the newborn is also found in Naṟṟinai 380 as one substance with which birth is celebrated.41 In the romances, butter appears in association with love, as could be expected. In Naṟṟiṇai 12, the churning is associated with the beginning of the day as in Cilappatikāram 17, to constitute a metaphor about disappearance and transformation given by love.42 This comes also in Nāṟṟiṇai 84 when the poet evokes the saltiness [that]…:

…rises as within the heat of unfinished buttereaten by the churning stick in the earthen pot.43

In Kuṟuntokai 106, the heroine compares herself to fire into which ghee is poured in a metaphor of burning desire.44

Butter offers similar connotations in the war-themed Puṟanāṉūṟu, but there it has been adapted to the epic nature of the anthology. It is delicious and points toward riches and its brilliance. The hymnist of 384 praises the one who pours ghee “more freely than water”45 while Puṟanāṉūṟu 65 (l. 2) tells the dire situation that accompanies the death of a ruler by lamenting over giant pots, lying on the ground, that “have forgotten how to hold the ghee.”46 There butter emerges as a substance first and foremost linked to celebrations of victorious kings “who pour more ghee than there is water, sacrifice more than there are numbers, [and] spread your fame on earth,” and Brahmins who “under the glow of three fires offer ghee according to their secret rites.”47

Thought to have been composed at the same period of time as the Kalittokai to which we will come, the Paripāṭal presents a different set of evidence, as this is not a romance or epic collection of poems but an anthology of hymns, some in honor of Tirumāl-Viṣṇu. One would expect a greater likelihood of encountering Kṛṣṇa. In fact, however, we meet him only once. With markedly Vedic references and the tightness of his association with Balarāma, the Vaishnava god of the Paripāṭal corresponds with the early Bhāgavata traces of North and Central India, for whom the adult god of the Mahābhārata was the foremost.48 The childhood of Kṛṣṇa is not directly mentioned.49 Its cowherd aspect may be discerned, however, with the word kōvalaṉ, “cowherd” in an enigmatic verse associating one of them with a pot and the one with a plow:

Right and left, pot and plow, cowherd and guardian.(Paripāṭal 3.83)

The butter is not mentioned, but the kōvalaṉ, the cowherd, is paired with the one of the plow, or Balarāma, here a guardian and the only deity with such tool/weapon, and is provided with a pot, as if it would be his characteristic attribute.50 Is it a pot containing milk-products? We can only stress that a pot was considered characteristic enough to be the equivalent for Kṛṣṇa as is the plow for his brother Balarāma. As such, it could well be the uṟi of the Cilappatikāram. A pot, designated as kutam, is at the origin of the South Indian motif of the dance with pots that appears in the Cilappatikāram, is further developed in the Divyaprabandham, and often represented on Cōḻa-period temples from the end of the ninth century. No matter which evidence you privilege, it is clear that the pot had its importance in the southern legend of Kṛṣṇa. The one held by the cowherd, the kōvalaṉ of the Paripāṭal, may signify an early association with butter. It does not have a clear equivalent in the earliest, northern, versions of the legend of Kṛṣṇa. With “Fragment” I.64–71, the churning of the ocean is also part of the Paripāṭal. The deity takes the shape of the snake-rope used to churn the milk ocean and of the churner, or both the shape of Kṛṣṇa and his brother in the Sanskrit accounts of the myth.51

No clear profile emerges from this review. Butter is a mark of riches associated with rituals, one characteristic that cannot be considered a distinctively southern one, as clarified butter is one main element of sacrifices attached to Vedic traditions; butter is introduced in love poems with a sexual overtone, but echoes of the same kind are also reported from Vedic traditions.52 It is not unmistakably linked with Kṛṣṇa even in the Paripāṭal. But by far the anthology of the Caṅkam corpus in which the butter is most present is the mullai section, the “jasmine” section, of the late love anthology, the Kalittokai. Cowherd settlements, milk-products, the uṟi, and Mayōṉ-Kṛṣṇa himself are set characteristics of the mullai tiṇai, the jasmine interior landscape of Tamil literature after which this section of the anthology in kali meters has been named.53 The Kalittokai consists of a series of poems that provide a vivid backdrop to Cilappatikāram 17, and in the Kalittokai, butter plays many roles.

6.3. Kalittokai

For a summary of references to Kṛṣṇa in the Kalittokai, let us refer the reader to the unrivaled study of F. Hardy (Hardy 1983, pp. 183–93), who reports 16 instances. Most of them are concentrated in a group of poems that belongs to the mullai section of the anthology (Kalittokai 103–108). These are related to a bull-fight and a dance, similar to the one staged in Cilappatikāram 17, and on which we will now focus, as there is no mention of butter in the other references to the deity dispersed in other poems of the anthology.54

In Kalittokai 106, built around a bull contest of the cowherds who dance kuravai and praise the Pāṇḍya king, butter is part of the cowherd equipment, and the uṟi is mentioned from the very beginning:

The inhabitants of vast lands wet at the time the rainy season that made its appearance, the(se) cowherds of improper (vaḻūu) language, with their herds of cows, who make their sweet flute of lengthy koṉṟai to resonate, having balanced the earthen vessels of harmonious (icai) sound together with the hanging pots (uṟi)/tie (imiḻ) to fasten (icaittal)/the earthen vessels tied with ties…(Kalittokai 106.1–5)

Later in the same poem churning is mentioned with the ornaments it produces on the shoulders of the heroine:

“Hey my friend, the ornaments of my shoulders,the dots above, from the churning of yogurtin the milk,are destroyed through the embrace that shed bloodof the one who takes the murderous bull…”,(Kalittokai 106.37–39).55

In the poem 108, the heroine takes over the role of a milkmaid who goes selling milk-products used as metaphors for the amorous exchange with the hero calling her:

“Passing by here, at the time of going home,having sold enough of your curdled milk,the weapon of your smile proclaiming your power, you struck my breath,hey you! hostile woman which fault did I commit towards you?”(Kalittokai 108.5–7).56

Similar lines come later in the poem to be more precise about the love situation, and the image of the thief is introduced in the stanza we cited at the beginning of this paper:

“Having sold butter, at the time of the return–does one remember?—on that day,When the flowers of jasmine densely flourished, near the small river of one wood,With your eyes similar to tender young mangoes, my heartyou took to bind (me) and rule on the battle-field: what if you are not but a thief of a unique kind?”.(Kalittokai 108.26–29)57

The thief is the woman from a village where churning is going on in suitable time:

The sound of the butter is heard close by, it is not a distant thing,if the village is near, if time is the middle of the day….(Kalittokai 108.35–36)58

Here, butter is a marker of prosperity as in the other anthologies. But, above all, it is a marker of desire in a cowherd settlement described like the one of the Harivaṃśa. Kalittokai 110 is the culmination of the association of love with butter, when the heroine calls the hero:

“—Hey you!Were you looking for the pastoral beauties of the large and fenced villageas a medicine for the aching scorpion of your desire?I came to you, sketched a smile, but you consider me as a woman easy to get!Thinking I was as generous of my body as I was of white butter!”.(Kalittokai 110.1–6)59

At this point to sell butter is interpreted by the hero as the promise of a gift of another kind, a consent to the desire the milkmaid has aroused. The metaphor is extended in the poem when the hero says of his heart:

“Like a rope attached to the churning pole of your beautymy heart goes round and round…”.)(Kalittokai 110.10–11)60

and, eventually, considers his life as the sap exhausted by the churning that produced butter:

“Sufferings kept growing time after time,Turned into the juice of churned butter,my melted heart wants no other medicinethan the touch of (your) hand!”.(Kalittokai 110.16–19)61

In these stanzas butter appears as an integral part of the cowherd setting and a result of a churning that expresses the torments of the lover’s heart. These are a substance and an activity that link love—the main theme of early Caṅkam anthologies and of the Kalittokai—with the pastoral deity of the Harivaṃśa. The importance taken by both butter and churning in the Cilappatikāram canto dedicated to the god who presides over the mullai tiṇai is thus understandable. In Kalittokai, stealing butter was not recorded as a specific activity of the mullai tiṇai, nor of Kṛṣṇa. But there is definitely a role for butter as a symbol for what the hero is ready to take without permission, while in the Cilappatikāram butter is something that is stolen by Kṛṣṇa. But who is this thief when he is not Kṛsṇa?

6.4. Thief of the Heart

In Cilappatikāram 17, a first larceny is alluded to with the mythical churning celebrated twice in the canto—and once, just before the theft of butter. When gods and demons churn the ocean of milk, indeed the amṛta that comes out is stolen by Garuḍa and then taken by Mohinī. When the child Kṛṣṇa steals the butter from Yaśodā’s churning, he acts as these other forms of Viṣṇu. In the Divyaprabandham, the Āḻvārs make this theme explicit by equating the three steps taken by Viṣṇu in the Cilappatikāram with a theft of the earth after having mentioned the theft of butter:

All the butter stored in pots he stole and ate,Like he stole the entire earth from Bali and ate (it) with his large belly,When as a tall dwarf he made a pact for three steps of land to stride…(Nammāḻvār, Tiruviruttam 91, [TP 2568])

Thievery appears thus as an essential activity of the god, and the theft of butter as one among other thefts. But the word kalavu used to style the theft of butter in Cilappatikāram is specific and enhances another aspect of the earthly raid that matches the background provided by Kalittokai. Love is in the air.

Kaḷavu is so specific a word it has given its title to one of the first known works on the akam (love) genre of Caṅkam literature, the Kaḷaviyal Akapporuḷ, “The story of stolen love,” of Iraiyaṉār. This was composed, it seems, at the time the Bhakti genre was flourishing, between the sixth and the ninth centuries.62 Variously translated as “secret love,” “premarital love,” “clandestine love,” etc., when encountered in the akam genre, kaḷavu designates a theft of a specific kind, the one of a lover. Even if it can designate a “simple” theft, it remains a word imbued with the Caṅkam love background that is the literary horizon of Kalittokai and Cilappatikāram. It introduces a supplementary nuance in Kṛṣṇa’s mischief and suggests the presence of the love hero of Caṅkam. In Cilappatikāram 17 this character is well present indeed, and the mention of a kaḷavu does not come as a surprise. Between the churning for the Pāṇḍya king and the songs to Kṛṣṇa, or at the heart of the canto, Kṛṣṇa, then anonymous as the Hero in the Caṅkam poems, steals the bangles, the clothes, and eventually the beauty (taiyal) of a no less anonymous Heroine. There the god acts like the heart thief of the Caṅkam. As the Heroine of Kuruntokai 25 puts it:

“Only the thief was there, no one else.And if he should lie, what can I do?”Cilappatikāram 17.24 (2–3) relays the lament:How can we describe his presence who cheatedThe girl, who stole his heart, of her virtue and bangles?(Transl. Parthasarathy [1993] 2004, p. 174)

At the beginning of Kalittokai 114, we encounter the Hero pretending he is a child—while it is obvious he is not (ōri putalvaṉ aḻutaṉaṉ eṉpa ō, Kalittokai 114.2). Such behavior seems to foreshadow the Kṛṣṇa of the Divyaprabandham, another “fake” child who not only steals butter but also clothes, bangles, and more from the gopis in the frame of a theft of cowherdesses’s clothes, which is another episode that is first found in the South Indian corpus. In between the love-hero of Kalittokai and Divyaprabandham stands the Butter-thief—and love-thief—of Cilappatikāram. To summarize, Cilappatikāram 17 makes use of a pattern that is also staged in the Caṇkam Kalittokai anthology, featuring Kṛṣṇa as the Hero who steals everything from the milkmaid, starting with her butter.63 The stealing is inspired by an amorous love poetry already associated with the cowherd world in the Kalittokai where butter is a metaphor for love, produced by a churning of the Hero’s heart, desirous of “something” owned by the milkmaid. The mullai section of the Kalittokai and Cilappatikāram 17 share many motifs,64 and the amorous patterns of the Caṅkam corpus constitute a major source of inspiration for the Kṛṣṇa of the Cilappatikāram 17. Kalittokai reveals the role of Kṛṣṇa as butter-raider. Consequently, the first textual appearances of the Butter-thief figure merge Kṛṣṇa as an avatāra of Viṣṇu, in line with the Sanskrit Harivaṃśa, with an avatar of the love hero of the Tamil Caṅkam. Butter thievery makes its appearance in Tamil texts as the outcome of a Kṛṣṇa-oriented “North Indian” (vaṭa) tradition65 that already described in some detail a cow herding settlement, where the churning of butter was a main activity. It fits into the previous Sanskrit tradition in focusing on the churning that strengthens the ties between Kṛṣṇa and Visnu and, at the same time, between the Caṅkam love hero and Kṛṣṇa.

7. Jaina Versions of the Story

Several Jain texts composed between the end of the eighth and the 12th century mention Kṛṣṇa’s penchant for butter when telling the story of the tīrthaṅkāra Ariṣṭanemi, who is the cousin of Kṛṣṇa and his brother Rāma in the Jain traditional accounts.

The earliest of these is the Harivaṃśapurāṇa of Jinasena, a digambara monk who composed his Sanskrit work around 783 in Gujarat.66 Its chapter 35 evokes the childhood of Kṛṣṇa. In 35.42 comes the death of Kupūtanā, in whom we recognize the Pūtanā of the Harivaṃśa, killed by a child, who spends his time as follows:

Jiṣṇu (Kṛṣṇa) spent his days and nights in sleeping, relaxing, crawling onhis stomach, kicking, running continuously, babbling, and eating butter.(Harivaṃśapurāṇa 35.44)

Verse 44 tells how this child fights a chariot-demon, and, in 35.45, how he uproots twin trees where two demons have taken place. The events linked with Kṛṣṇa’s love of butter are thus the same as in the southern versions of the Harivaṃśa, but there is no mention of a theft of the loved butter. Similarly, in the Riṭṭhaṇemicaru of Svayambhu, an apabhraṃśa text composed in the second half of the ninth century, Kṛṣṇa is said to eat butter when he defeats the demonic bird sent by Kaṃsa (5.6):

A little later in the courtyard of the camp, Hari was having in his hand freshly churned butter. At that moment, from the sky came another deity sent by Kaṃsa. She has taken the form of a crow and was croaking.

In the Harivaṃśa of Puṣpadanta, composed in apabhraṃśa between 959 and 965 at the court of the Rāṣṭrakūṭas, in Karnataka, the section 85.6–7 evokes a dust-covered Kṛṣṇa frolicking and playing with the churn, the milk-products and the butter, then:

Some other time, Kṛṣṇa saw one ball of butter and eats it as if it was the glory of Kaṃsa. This depiction takes place before the attack of demonic creatures, starting with Pūtanā, followed by a chariot and the twin arjuna trees. Finally, in the Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacaritra (the story of 63 tīrthaṅkara) of Hemacandra, who belonged to the second half of the 12th century (1160–1172) and lived in Gujarat, the tale about the bull Ariṣṭanemi comprises the episode of the two arjuna trees (here, as one demon who tried to crush Kṛṣṇa). Kṛṣṇa went between the two trees with a mortar and uprooted them. At that moment he is said to be covered with dust (8.5, 137–141), as in the first part of Harivaṃśa 51 where the breaking of the arjuna trees is told; afterwards he is depicted as a naughty child who takes fresh butter when it is churned (8.5, 143).

It is problematic to recognize the Jain Kṛṣṇa as having inspired the deity of Cilappatikāram 17. First, the dating implies these Jain accounts from Karnataka and Gujarat would have been inspired by the Jain Tamil epic poem, instead of the other way around. Furthermore, given the brevity in the Cilappatikāram of the allusions to a legend of Kṛṣṇa, which is much more developed in these more northern-located Jain texts, the Cilappatikāram could not constitute the sole source for them. At the same time, all the numerous episodes of those Jain accounts have their equivalent in the Sanskrit Harivaṃśa and/or the Viṣṇu-purāṇa/Brahma-purāṇa, with the conspicuous exception of the theft of butter. Conversely, several allusions in Cilappatikāram 17 to the legend of Kṛṣṇa cannot be understood without other South Indian texts—the Caṅkam love anthologies, among which Kalittokai is prominent, but also the Tamil Divyaprabandham and the Bālacarita, to which we will return in a moment. These elements, including a fight against several bulls (see supra, note 63), the pulling out of the kuruntu tree (citrus), and the figure of the flute player, do not have clear equivalents in the oldest Sanskrit texts devoted to Kṛṣṇa, Jain or otherwise. They are some of these double-motifs to which we have already referred, born in the south of India from the encounters between a northern Sanskrit and carved tradition, and a literary tradition of the South. Besides, from the eighth to the 12th century, the diffusion of Sanskrit and Prākrit texts in Gujarat and Karnataka is more probable than familiarity with the Cilappatikāram, whose impact in Gujarat seems to have been limited by the Tamil language used to compose the poem.

The sectarian aspect of the texts constitutes a final difficulty. These Prakrit and Sanskrit Jain texts are much more critical of Kṛṣṇa than the Cilappatikāram is. They help us to perceive in the Tamil poem an irony that adds one more level to its complexity. It can be considered that in Cilappatikāram 17 we start from cosmic deeds to land on futile everyday events, the cosmogonic churning of the ocean being reduced to a churning by an old lady in a cowherd village, for instance. But there is still a grandiose scope in the Tamil lines, while derision cannot be missed in the relevant passages of the other Jain works. In the Cilappatikāram the stupid Pāṇḍya king who dies is an incarnation of Kṛṣṇa, but the Cēra king is another figure of Kṛṣṇa, and one who churns the ocean. It would be difficult to consider such a statement as disparaging, since the Cēra king is said to be the Cilappatikāram’s patron. Eventually in the Jain texts composed in North Indian languages, Kṛṣṇa does not steal the butter, even though, given the mocking context of the Jain accounts, it would have been tempting to present him as a robber. It thus seems to us likely that these medieval Jain texts of Gujarat and Karnataka were part of a tradition that originated mainly in a northern area of India.67

To summarize, from around the sixth century and probably a little later, a contrast emerges between texts from northern and southern India. In the South, Kṛṣṇa’s love for butter is mentioned much earlier and more frequently than in the North. From the end of the eighth century, Sanskrit and Prākrit Jain texts composed in Gujarat and Karnataka also mention the young god’s love for butter. They derived inspiration from northern versions, though it cannot be denied that, like the southern versions of the Harivaṃśa, they were also influenced by southern works, as exemplified by the Cilappatikāram. But what about sculptures of the episode of the theft of butter?

The Maṇḍor relief of a butter-lover made before the sixth century comes from Rajasthan, an area bordering Gujarat, while all the episodes evoked in the Jain texts are represented earlier in stone in an area where Indo-Aryan languages are prevalent. In the Dravidian part of India, it is only in the north of Karnataka that some of the first carved narrative cycles include a butter lover. But the representation of a butter theft can be questioned. Is it really a Butter-thief that is represented? Or “only” a butter-lover and a churning? The theme of a larceny is not that obvious in the said sculptures. The child does not hide himself to take the butter and the milkmaid does not prevent him from doing so, nor does she scold him. We have seen that the toddler lifts his head and turns it towards the churning woman, as if checking if she can see him. In secondary literature, before the influential book of J. S. Hawley (Hawley [1983] 1989), the early stone reliefs were regularly identified as “the churning.”68 The attitude of the young butter-lover can be thought to be provocative, but it does not suggest the secret implied in the kalavu of Cilappatikāram 17. In contrast, the earliest representations in which a theft is clearly depicted were not made until the ninth century, and they come first from the Tamil area.

8. South-Indian Texts and Carvings from Seventh to Ninth Century

Soon after the Cilappatikāram was composed, the legend of Kṛṣṇa appeared under a much more extended form in two works and languages. It emerged in Tamil in the four thousand verses of the Divyaprabandham of the Vaiṣṇava saint-poets (Āḻvāṟs) and in Sanskrit with the play called the Bālacarita (Story of the Child), two works dated between the seventh and ninth century. In these two, thievery of butter took another turn to be more closely associated with the legend of Kṛṣṇa. In the Divyaprabandham, the love for butter is clearly mentioned in more than 200 stanzas that are authored by eight out of the 12 poets, including three of the most prolific: Periyāḻvār, Nammāḻvār, and Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār (whose work constitutes one third of the anthology), and it emerges as one of the most famous characteristics of the young Kṛṣṇa.69 If each of the Āḻvārs entertains a specific relation with the Sanskrit corpus and the patterns elaborated in the Kalittokai and Cilappatikāram, and each of them performs with a voice of his own,70 the theft of butter is common to most of them and is revealed as the emblematic prank of the god. The following stanza of the Tiruviruttam of Nammāḻvār gives an idea of the extent of this practice. The devotee asks the bees:

Unite meWith the flawless flower-like feetOf the one who stole butter, and was scoldedFor many such thingsThe king of gods is my lord, o Bees.(Tiruviruttam 54 [TP 2531], transl. Venkatesan 2014, p. 52)

Most poems of the Diviyaprabandham are similarly structured in stanzas whose four lines lead to a tendency to present vignettes that can be enclosed in one strophe only. In the vignettes thus drawn, a narrative emerges that links a theft of butter to the rest of the legend of Kṛṣṇa. The voracious toddler eats the butter and steals it so often that Yaśodā ties him to the mortar he stands on to reach the hanging pot where the butter is kept; with this mortar the young deity uproots the marutam (the Tamil arjuna) trees between which he goes. Hence the butter-theft is linked with the powerful uprooter of the arjuna trees. As we have already seen, that narrative is inserted into the traditional account with verses added to the Mahābhārata and the Harivaṃśa in their southern versions. These additions are positioned just before the uprooting of the arjuna trees. The story is encountered twice in the Bhāgavata-purāṇa, in chapters 8 and 9 (BhP 10.8.30; 10.9.8), where it is the source for one major twin motif, in which Yaśodā is depicted as seeing the universe in Kṛṣṇa’s mouth (see below):

For the [pots] hung out of reach he (Kṛṣṇa) devises a way by piling up things or turning over a mortar and then finds his way up to the content by making a hole in the pot. (10.8.30)

Standing on top of a mortar for spices, he (Kṛṣṇa) had turned over, looking around anxiously because of the stealing; from a hanging pot (he) to his pleasure handed a share of butter and other milk goodies out to a monkey; watching him from behind, she (Yaśodā) slowly approached her son. (10.9.8)

Then Yaśodā binds her son to the mortar, a part of the story to which Cilappatikāram 17 alludes in the stanza just before the one of the “Butter-thief”:

Your hands that churned are the hands Yaśodā boundWith her churning rope…

Divyaprabandham proves more creative than the “epic” as, in the numerous stanzas of the Bhakti corpus, the binding and the eating of butter are detailed, various, put in correspondence one with the other, and give birth to other motifs as well. The stolen butter is commonly held in the uṟi, from which Kṛṣṇa licks butter in the Cilappatikāram. Since many strophes are built from formulas or include formulaic epithets, allusions to the liking of butter also include instances where an uṟi does not appear. Instead of the mortar on which Kṛṣṇa climbs, an upturned pot may appear.71 Eventually, Kṛṣṇa is sometimes caught by Yaśodā, sometimes by a group of cowherdesses as in the Periya Tirumaṭal of Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār (138–139; TP 2786), or an anonymous milkmaid as in the following stanza of Nammāḻvār:

You who hold aloft disc and conch as weaponsStole butter then criedWhen the cowherd woman bound you with ropes,My lord what’s left to say in my lament?(Tiruviruttam 86 (TP 2563))72

Cowherdesses in a group figure less often than a sole woman to catch the child, but their band is very present at the background, watching Kṛṣṇa with amazement, laughing, complaining, losing their temper, etc. The beating of Kṛṣṇa by a group of cowherdesses, an anonymous milkmaid, or his foster-mother appears often. It is not always mentioned, however; in any series, several of Kṛṣṇa’s (or other forms of Tirumāl-Viṣṇu) deeds may be enumerated, some added, others expanded, etc.

The episode of the uprooting of the two trees is often mentioned together with the theft of butter, even in strophes where the mortar is not mentioned and, thus, appears tightly linked with the theft of butter.73 The uprooting of trees also presents variants, some that are to be associated with this episode only (demons or not, type of trees…), and others that are typical of South India, where the pulling up of the trees has inspired the “twin motif” of the uprooting of another tree, the kuruntu.74 In addition to this, we notice that the order of the events is not as fixed in the Divyaprabandham as it is in the southern versions of the Harivaṃśa or in the Bhāgavata-purāṇa. Still, when the killing of Pūtanā and the uprooting of the trees are mentioned together with the theft of butter, they usually appear with Pūtanā in the first position, the theft of butter in the second, and the uprooting of the arjuna trees in the third, as they do in the southern versions of the Harivaṃśa.75 This order is justified by the mortar used as a punishment for the theft, whereas it was used as a means for giving a halt to a generally mischievous behavior of the god in the earliest, northern, version of the Harivaṃśa. The link with the Pūtanā episode is commonly introduced by the act of eating (just as he has “eaten” Pūtanā, Kṛṣṇa eats the butter; Kṛṣṇa eats all kinds of milk-products, starting with Pūtanā’s milk, etc.).76 No narrative logic is provided in this case, and the association may come from the storyline of the Harivaṃśa in which the chapter devoted to Pūtanā (HV 50) is positioned just before the one of the arjuna trees (HV 51). The connection between the events is looser in this case, following the sequence of the Harivaṃśa narrative.

Thus, it is found that, with the Divyaprabandham, the episode of the Butter-thief becomes an integral part of the legend of Kṛṣṇa. There, it is placed at the beginning of the childhood of the god and associated with the uprooting of the marutam/arjuna trees. Kṛṣṇa climbs on the mortar to reach the uṟis. There is no mortar in the Cilappatikāram, in which the only mention of the twin trees episode comes in honor of the goddess of Canto 12 who is praised as another Kṛṣṇa who, incidentally, walked between the maruta trees. In the Divyaprabandham, the tying of Kṛṣṇa to the mortar allows for the episode to be linked to the narrative presented in the earlier Sanskrit corpus, as in the following stanza by Tirumaṅkai that ends a decade cadenced with the binding of Kṛṣṇa:

That garland of Tamil songs (is) by Kaliyaṉ the king of Maṅkai of fertile fields,(destined) to the feet of the Lord who was bound to a mortar because one day he played with the white butter of the milkmaids,the one who filled his stomach with the butter, the curd and the milk of the hanging pot (uṟi)…(Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār 10.6.10; TP 1907)77

Tirumaṅkai is considered to be one of the latest authors of the corpus, but the same scheme is encountered, among others, in Pēyāḻvāṟ (91; 2372), who is certainly one of the earliest. The variants sometimes appear inside compositions by the same Āḻvāṟs. They speak of an inventiveness at work that makes it plausible that the Divyaprabandham designed the narrative that was destined to become dominant in the Bhāgavata-purāṇa. Eventually, the story made famous through the Bhāgavata-purāṇa emerges with all its details. They include an important one that seems to go far beyond the Butter-thief, a world eaten, stolen, and spit out. The Kṛṣṇa of Cilappatikāram 17 is praised by immortals as devouring the universe:

You devoured the entire universeThough hunger does not trouble you. Your mouthThat devoured is the mouth that licked the butterStolen from the hanging pot,has inspired a stanza like Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār 10.7.3 (TP 1910):This mischievous small one, Ah girls!filled himself with the inside of the hanging pot,—white butter piled as a white mountain—,And feeling drowsy this thief finally fell into sleep!Look: his hands are all butter, his childish tummy as swollen as in days of yore with the seven worlds! poor me, what shall I do?

With such a stanza, it is clear that the gulping of butter of the Divyaprabandham echoes the devouring of the world envisioned in the Bhagavad-gīta. From the butter-licking of Cilappatikāram 17, comes a cosmic vision of the universe inside of the god. This is what Yaśodā sees at the end of chapter 8 of Book 10 of the Bhāgavata-purāṇa 10 (10.8, 33–45). The episode of Yaśodā seeing the universe in Krsna’s mouth is positioned between the two thefts of butter (10.8, 29–32 and 10.9, 1–10). Having stolen butter, Kṛṣṇa ate dirt, revealed as this earth in which he rolled himself in a tradition we know from the early Harivaṃśa.78 Desiring to see what he put in his mouth, Yaśodā sees:

…the entire world, together with the moving and stable entities, outer space, and the sky, the directions along with mountains, islands, oceans, the surface of the earth, together with the wind, fire, moon and stars. She saw the circle of the planets, water, brightness (tejas), outer space, and also sky […]