The Carving of Kṛṣṇa’s Legend: North and South, Back and Forth

Abstract

1. Introduction

“He loves butterHow radiant!—fresh butter in his hand(…)Blessed, says Sur, is one instant of his joy.Why live a hundred eons more?”Transl. John S. Hawley, The Memory of Love, Sūrdās Sings to Krishna.

2. The Butter-Thief as a Northern Motif

Having sold butter, at the time of the return—does one remember?—On that day,When the flowers of jasmine densely flourished, near the small river of a wood,With your eyes similar to tender young mangoes, my heartYou took to bind (me) and rule on the battlefield: what if you are not but a thief of a unique kind?Kalittokai 108.26–29.1

(…)Crawling on his knees, his body adorned with dust,Face all smeared with curd,Cheeks so winsome, eyes so supple,A cow-powder mark on his head,Curls swinging to and fro like swarms of beesBesotted by drinking drafts of honey,At his neck an infant’s necklace, and on his lovely chestThe glint of a diamond and a tiger-nail amulet.Blessed, says Sur, is one instant of his joy…

“There are many open spaces, happy and strong people are around; there are a lot of ropes in the station and the sound of the churning is heard from every place.Lots of buttermilk are around and the earth is wet with curd. Milkmaids create sound with the noise coming from the churning sticks that they stir.”(Harivaṃśa 49.24–25)10

“Both had long arms that looked like snakes. They moved everywhere. With dust on their bodies, they shone like baby elephants.Sometimes their bodies were covered with ashes and sometimes with cow dung. They ran around like the sons of fire god.As they crawled on their knees in some places, they looked enchanting. They went to cowsheds for playing and their bodies were covered with cow-dung.Both were blessed with prosperity (śrī). They gave great pleasure to their parents. Here and again, they would be mischievous with people and laugh.Both roamed around the camp (vraja), doing various pranks. Nandagopa was unable to control these two.Once, Yaśodā became very angry with the lotus-eyed Kṛṣṇa. She brought him by the side of a cart and she summoned him again and again.”(Harivaṃśa 51.8–13)14

3. First Sculptures: North India

4. The Northern South: Karnataka

5. Carvings and Texts: Oral Transmission and Folk Culture

6. First Mentions of the Butter-Thief: Tamil Poems

6.1. Cilappatikāram

Lord of the color of the sea! Once long ago you churnedThe belly of the sea with the northern mountainAs a churning stick, and the serpent Vāsuki as a rope.Your hands that churned are the hands Yaśodā boundWith her churning rope. Lord with a flowering lotus in your navel!Is this your māyā? Your ways are strange!

He is the supreme being.” Thus the immortals adoredAnd praised you. You devoured the entire universeThough hunger does not trouble you. Your mouthThat devoured is the mouth that licked the butterStolen from the hanging pot. Lord with a wreath of rich basil!Is this your māyā? Your ways are strange!28Tirumāl whom the host of gods adoreAnd praise! You strode the three worldsWith your two red-lotus feet to rid them of darkness!Your feet that strode are the feet that pacedAs the Pāṇḍavas’s envoy. O Narasiṃha! Destroyer of foes!Is this your māyā! Your ways are strange!29(transl. Parthasarathy [1993] 2004, p. 177, emphasis added)

“…Today it is our turn (to give) butter” said Aiyai,having called her daughter, taking churning rope and churning-stick,There appears the old milkmaid.31 (…)

In the pot the milk has not curdled,from the innocent eye of the globular humped bull, water comes, oozing,something terrible will come.The fragrant butter from the hanging pot (uṟi) has been eaten,it does not melt, it diminishes, (…)In the hanging pot (uṟi), the butter does not melt!32

6.2. Caṅkam Literature

…rises as within the heat of unfinished buttereaten by the churning stick in the earthen pot.43

Right and left, pot and plow, cowherd and guardian.(Paripāṭal 3.83)

6.3. Kalittokai

The inhabitants of vast lands wet at the time the rainy season that made its appearance, the(se) cowherds of improper (vaḻūu) language, with their herds of cows, who make their sweet flute of lengthy koṉṟai to resonate, having balanced the earthen vessels of harmonious (icai) sound together with the hanging pots (uṟi)/tie (imiḻ) to fasten (icaittal)/the earthen vessels tied with ties…(Kalittokai 106.1–5)

“Hey my friend, the ornaments of my shoulders,the dots above, from the churning of yogurtin the milk,are destroyed through the embrace that shed bloodof the one who takes the murderous bull…”,(Kalittokai 106.37–39).55

“Passing by here, at the time of going home,having sold enough of your curdled milk,the weapon of your smile proclaiming your power, you struck my breath,hey you! hostile woman which fault did I commit towards you?”(Kalittokai 108.5–7).56

“Having sold butter, at the time of the return–does one remember?—on that day,When the flowers of jasmine densely flourished, near the small river of one wood,With your eyes similar to tender young mangoes, my heartyou took to bind (me) and rule on the battle-field: what if you are not but a thief of a unique kind?”.(Kalittokai 108.26–29)57

The sound of the butter is heard close by, it is not a distant thing,if the village is near, if time is the middle of the day….(Kalittokai 108.35–36)58

“—Hey you!Were you looking for the pastoral beauties of the large and fenced villageas a medicine for the aching scorpion of your desire?I came to you, sketched a smile, but you consider me as a woman easy to get!Thinking I was as generous of my body as I was of white butter!”.(Kalittokai 110.1–6)59

“Like a rope attached to the churning pole of your beautymy heart goes round and round…”.)(Kalittokai 110.10–11)60

“Sufferings kept growing time after time,Turned into the juice of churned butter,my melted heart wants no other medicinethan the touch of (your) hand!”.(Kalittokai 110.16–19)61

6.4. Thief of the Heart

All the butter stored in pots he stole and ate,Like he stole the entire earth from Bali and ate (it) with his large belly,When as a tall dwarf he made a pact for three steps of land to stride…(Nammāḻvār, Tiruviruttam 91, [TP 2568])

“Only the thief was there, no one else.And if he should lie, what can I do?”Cilappatikāram 17.24 (2–3) relays the lament:How can we describe his presence who cheatedThe girl, who stole his heart, of her virtue and bangles?(Transl. Parthasarathy [1993] 2004, p. 174)

7. Jaina Versions of the Story

Jiṣṇu (Kṛṣṇa) spent his days and nights in sleeping, relaxing, crawling onhis stomach, kicking, running continuously, babbling, and eating butter.(Harivaṃśapurāṇa 35.44)

8. South-Indian Texts and Carvings from Seventh to Ninth Century

Unite meWith the flawless flower-like feetOf the one who stole butter, and was scoldedFor many such thingsThe king of gods is my lord, o Bees.(Tiruviruttam 54 [TP 2531], transl. Venkatesan 2014, p. 52)

Your hands that churned are the hands Yaśodā boundWith her churning rope…

You who hold aloft disc and conch as weaponsStole butter then criedWhen the cowherd woman bound you with ropes,My lord what’s left to say in my lament?(Tiruviruttam 86 (TP 2563))72

That garland of Tamil songs (is) by Kaliyaṉ the king of Maṅkai of fertile fields,(destined) to the feet of the Lord who was bound to a mortar because one day he played with the white butter of the milkmaids,the one who filled his stomach with the butter, the curd and the milk of the hanging pot (uṟi)…(Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār 10.6.10; TP 1907)77

You devoured the entire universeThough hunger does not trouble you. Your mouthThat devoured is the mouth that licked the butterStolen from the hanging pot,has inspired a stanza like Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār 10.7.3 (TP 1910):This mischievous small one, Ah girls!filled himself with the inside of the hanging pot,—white butter piled as a white mountain—,And feeling drowsy this thief finally fell into sleep!Look: his hands are all butter, his childish tummy as swollen as in days of yore with the seven worlds! poor me, what shall I do?

…the entire world, together with the moving and stable entities, outer space, and the sky, the directions along with mountains, islands, oceans, the surface of the earth, together with the wind, fire, moon and stars. She saw the circle of the planets, water, brightness (tejas), outer space, and also sky […]

9. The Churning

There are many open spaces, happy and strong people are around.There are a lot of ropes in the station and the sound of the churning is heard from every place.Lots of buttermilk are around and the earth is wet with curd.Milkmaids create sound with the noise coming from the churning sticks that they stir.(Harivaṃśa 49.24–25)

10. Conclusions, a Media as Important as Texts

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Primary References

Secondary References

- Banerjee, Priyatosh. 1978. The Life of Krishṇa in Indian Art. New Delhi: National Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Brereton, P. Joel, and Stephanie W. Jamison. 2020. The Rig Veda, a Guide. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhaus, Horst. 2000. The Mārkaṇḍeya-Episode in the Sanskrit Epics and Purāṇas. On the Understanding of Other Cultures. Proceedings of the International on Sanskrit and Related Studies to Commemorate the Centenary of the Birth of Stanislaw Schayer (1899–1941). Edited by Piotr Balcerowitz and Marek Mejor. Warsaw: Oriental Institute, Warsaw University, pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Buck, David C., and K. Paramasivam. 1997. The Study of Stolen Love: A translation of Kaḷaviyal eṉṟa Iraiyaṉār Akapporuḷ, with Commentary by Nakkīraṉ. Georgia: Scholars Press of Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- Couture, André. 1991. L’enfance de Krishna. Paris and Laval: Le Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Couture, André. 1992. Le Bālacarita attribué à Bhāsa et les enfances hindoues et jaina de Kṛṣṇa. Bulletin d’Études Indiennes 10: 113–44. [Google Scholar]

- Couture, André. 2007. La Vision de Mārkaṇḍeya et la Manifestation du Lotus. Histoires Anciennes Tirées du Harivaṃśa (éd. cr., Appendice I, no 41). Paris: École Pratique des Hautes Études, Sciences historiques et philologiques. [Google Scholar]

- Couture, André, and Christine Chojnacki. 2014. Krishna et ses Métamorphoses dans les Traditions Indiennes, Récits D’enfance Autour du Harivamsha. Paris: Presses Universitaires de la Sorbonne. [Google Scholar]

- Couture, André, and Charlotte Schmid. 2001. The Harivaṃśa, the Goddess Ekānaṃśā and the Iconography of the Vṛṣṇi Triads. Journal of the American Oriental Society 121: 173–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, Norman. 1987. Songs of Experience. The Poetics of Tamil Devotion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edholm, Erik Af, and Carl Suneson. 1972. The Seven Bulls and Kṛṣṇa’s Marriage of Nīlā/Nappiṉṉai in Sanskrit and Tamil Literature. Temenos: Studies in Comparative Religion 8: 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Emmanuel, and Charlotte Schmid. 2014. Introduction: Towards an Archaeology of Bhakti. The Archaeology of Bhakti I. Mathurā and Maturai, Back and Forth. Edited by Emmanuel Francis and Charlotte Schmid. Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry/École française d’Extrême-Orient, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gail, A. J. 1969. Bhakti im Bhagavatapurana. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, Ralph T. H. 1973. The Hymns of the Ṛgveda. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Prahlāda: Werden und Wandlungen einer Idealgestalt. Wiesbaden: Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur.

- Hardy, Friedhelm. 1983. Viraha-Bhakti, the Early History of Kṛṣṇa Devotion in South India. Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, George L., and Hank Heifetz. 2002. The Puṟanāṉūṟu. Four Hundred Songs of War and Wisdom, an Anthology of Poems from Classical Tamil. Penguin Books. New York: Columbia University Press. First published 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, John Stratton. 1989. Krishna, the Butter Thief. Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, John Stratton. 1987. Krishna and the Birds. Ars Orientalis 17: 137–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, John Stratton. 2009. The Memory of Love, Sūrdās Sings to Krishna. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, John Stratton. 2015. A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, D. Dennis. 2002. Rādhā and Piṉṉai: Diverse manifestations of the same goddess. Journal of Vaiṣṇava Studies 10: 115–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan, Iravathan. 2003. Early Tamil Epigraphy. From the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. Chennai and Cambridge: Cre-A and the Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Mysore Archaeological Department. 1938. Mysore Archaeological Department, Annual Report-1936 (MAR 1936); Bangalore: Government Press, pp. 73–80.

- Parthasarathy, R. 2004. The Cilappatikāram of Iḷaṅkō Aṭikaḷ. An Epic of South India, Translated, with an Introduction and Postscript. New York: Columbia University Press. First published 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Podzeit, Utz. 1992. A philological reconstruction of the oldest Kṛṣṇa-epic. Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens und Archiv für indische Philosophie 36: 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Preciado-Solis, Benjamin. 1984. The Kṛṣṇa Cycle in the Purāṇas. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, K. 2015. Early Writing System. A Journey from Graffiti to Brāhmī. Madurai: Pandya Nadu Centre for Historical Researches. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanujan, Attipate Krishnaswamy. 1994. Interior Landscapes, Love from a Classical Tamil Anthology. Delhi: Oxford University Press. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Rocher, Ludo. 1986. The Purāṇas. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Charlotte. 1997. Les Vaikuṇṭha Gupta de Mathurā, Viṣṇu ou Kṛṣṇa? Arts Asiatiques 52: 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Charlotte. 1999. Représentation anciennes de Kṛṣṇa luttant contre le cheval Keśin sur des haltères: l’avatāra de Viṣṇu et le dieu du Mahābhārata. Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient 86: 65–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Charlotte. 2002. Aventures divines de Kṛṣṇa: la līlā et les traditions narratives des temples cōḻa. Arts Asiatiques 57: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Charlotte. 2010. Le Don de Voir, Premières Représentations Krishnaïtes de la Région de Mathurâ. Paris: Publications de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient. [Google Scholar]

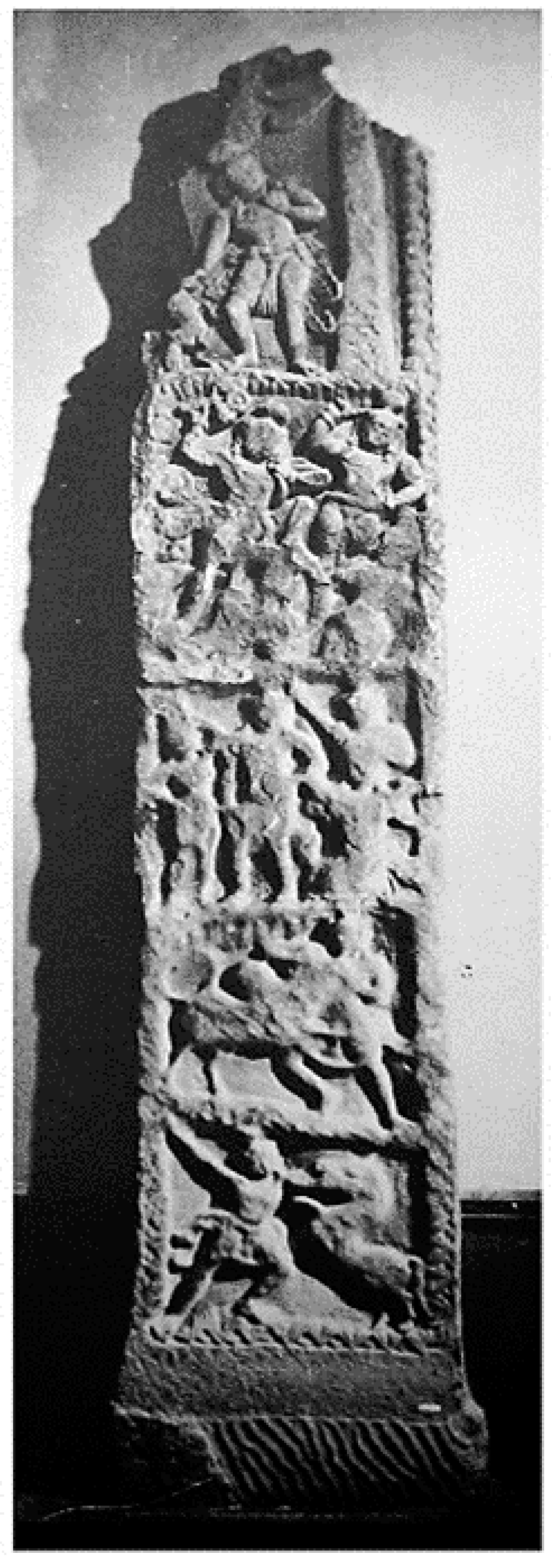

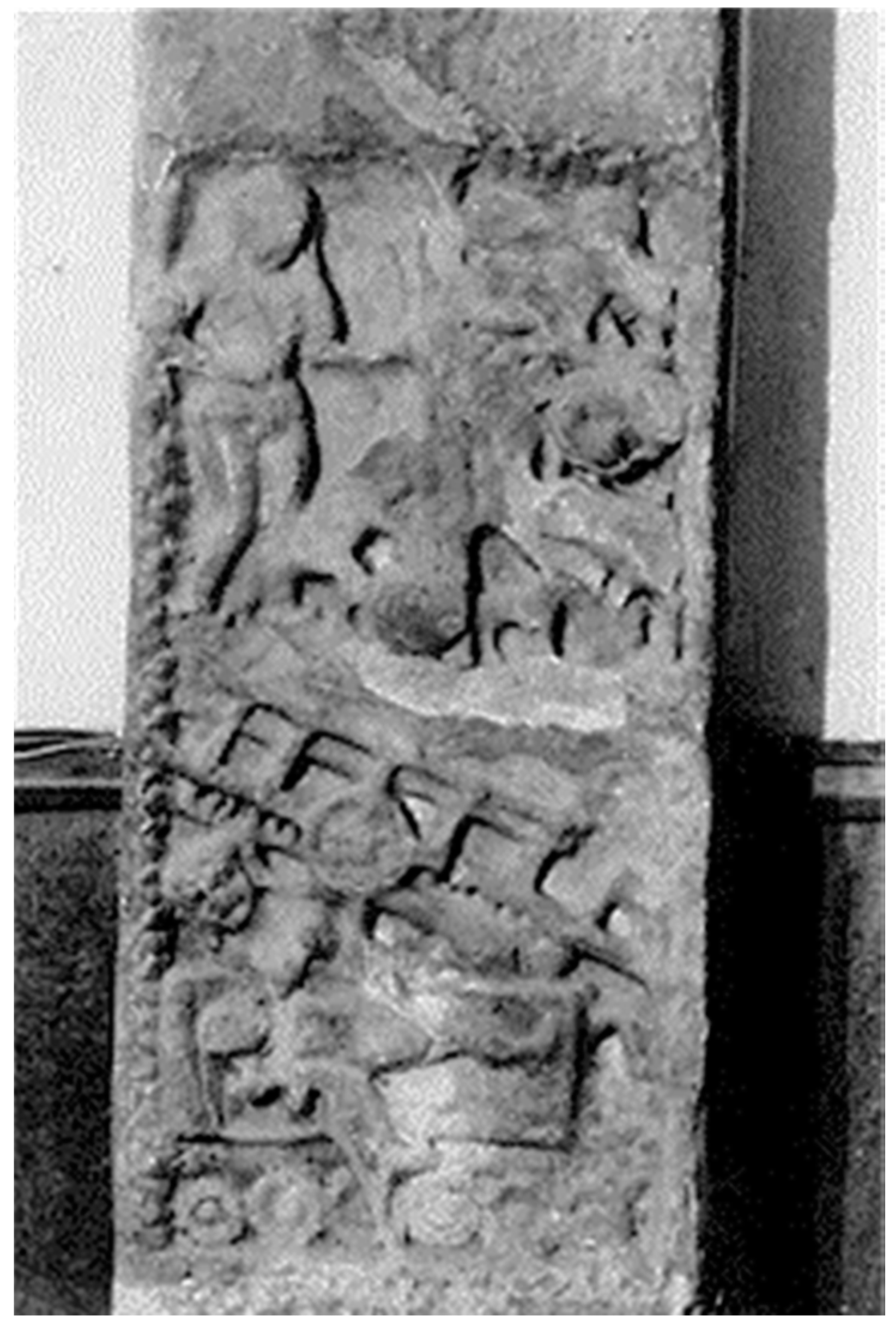

- Schmid, Charlotte. 2013. The contribution of Tamil literature to the Kṛṣṇa figure of the Sanskrit texts: the case of the kaṉṟu in Cilappatikāram 17. In Bilingualism and Cross-Cultural Fertilisation: Sanskrit and Tamil in Mediaeval India. Edited by Whitney Cox and Vincenzo Vergiani. Pondichéry: École Française d’Extrême-Orient/Institut Français de Pondichéry, pp. 15–52. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Charlotte. 2014. Sur le Chemin de Krsna. Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Charlotte. forthcoming. Elements for an Iconography of Nārāyaṇa in the Tamil land: Balarāma and a lost Vaiṣṇava world. In Viṣṇu-Nārāyaṇa: Changing Forms and the Becoming of a Deity in Indian Religious Tradition. Edited by Marcus Schmücker. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, phrase indicating stage of publication.

- Takanobu, Takahashi. 1995. Tamil Love Poetry and Poetics. Leiden, New York and Köln: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Tieken, Herman J. H. 2001. Kavya in South India. Old Tamil Cankam Poetry. Groningen: Egbert Forsten. [Google Scholar]

- Tieken, Herman J. H. 2003. Old Cankam literature and the so-called Cankam period. The Indian Economic and Social History Review 40: 247–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, Archana. 2014. A Hundred Measures of Time: Tiruviruttam by Nammalvar. Translated and Introduced by Archana Venkatesan. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Translations are my own unless otherwise noted. |

| 2 | For other references, see the two chapters “Sūr’s Butter-thief poems, two types” and “the Butter-thief in context.” (Hawley [1983] 1989, pp. 129–61). |

| 3 | For more (including bibliography) see the chapter titled “The Butter Thief Līlā” in (Hawley [1983] 1989, pp. 181–222). |

| 4 | Red, black, and white dominate the vignettes of the Sūrsagar. They may correspond to illustrations drawn with these three colors. |

| 5 | Seeing remains a master theme of the anthology, see Sūrsāgar 369, “… Tell him what I’ve described/And bring before these eyes, says Sūr, the image—.” transl. Hawley (1987, p. 169). Also “Lost, lost, lost to Mohan’s captivating image,” from poem 72 (transl. ibid., p. 84), etc.; on the topic of vision in the Sūrsāgar see (Hawley [1983] 1989, pp. 104–15). |

| 6 | Seeing the deity is a fundamental feature of rituals, as with the often-commented darshan of the deity. Still, cult-images kept in more or less accessible temples are far from being the only ones to be seen. The texts that tell Kṛṣṇa’s life enhance the visual, even when the god is a flautist. As if they were painters or sculptors, poets reveled in giving details about the appearance of the god, while in festivals processions, plays, dance recitals, and the like, very rarely does the one who embodies Kṛṣṇa play the flute he holds. The flute is more a means of identification and a symbol of the relationship established with the devotee than an instrument that produces sound. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | The list of dates given by L. Rocher (1986, pp. 147–48) shows the difficulties of dating this text. The span of ninth–11th century given in this paper matches with that of most of the authors. The dating given in A. J. Gail (1969, p. 12) or P. Hacker (1959, pp. 121–28), according to whom the Bhāgavata-purāṇa would date to the eighth century, being considered obsolete by most scholars since the publication of F. Hardy (Hardy 1983). Hardy (Hardy 1983, pp. 485–88) recapitulated the issue before comparing the text with the Āḻvārs’ corpus to demonstrate their close link; he concluded that, most probably, the Bhāgavata-purāṇa dates to the end of the ninth or the beginning of the 10th century. Iconographical details suggest a date during the second half of the 10th century, at the earliest (see Schmid 2002, pp. 42–47; 2014, pp. 57–97). |

| 9 | As a way to connect the two texts, there are many echoes with the Mahābhārata among the episodes of Kṛṣṇa’s childhood in the Harivaṁśa in the form of visions of a future that was already known when this prequel was composed. (See Schmid 2010, pp. 59–76, 139–43, 397–408). |

| 10 | kṣamapracārabahulaṃ | hṛṣṭapuṣṭajanāyutam | dāmanīprāyabahulaṃ | gargarodgāranisvanam ||49.24|| takranisrāvabahulaṃ | dadhimaṇḍārdramṛttikam | X After 25ab, D6,T1.2.4,G1.2.4.5,M ins.: navanīta+parikṣiptam | ājyagandhavibhūṣitam |49.25ab*624|| manthānavalayodgārair | gopīnāṃ janitasvanam ||49.25|| |

| 11 | sa dadarśa viparyastaṃ bhinnabhāṇḍaghaṭīghaṭam | apāstadhūrvibhagnākṣaṃ śakaṭaṃ cakramāli vai ||50.13|| “He saw the broken vessels and pots. The cart was lying upside-down, with the wheels up and its axle ruined.” |

| 12 | visarpantau tu sarvatra sarpabhogabhujāv ubhau | rejatuḥ pāṃśudigdhāṇgau dṛptau kalabhakāv iva ||51.7|| |

| 13 | As we can see in the poem cited at the beginning of this article, where Kṛṣṇa is marked with cow dung. |

| 14 | kvacid bhasmapradigdhāṇgau karīṣaprokṣitau kvacit | tau tatra paridhāvetāṃ kumārāv iva pāvakī ||51.8|| kvacij jānubhir uddhṛṣṭaiḥ sarpamāṇau virejatuḥ | krīḍantau vatsaśālāsu śakṛddigdhāṇgamūrdhajau ||51.9|| śuśubhāte śriyā juṣṭāv ānandajananau pituḥ | janaṃ ca vipra kurvāṇau hasantau ca kvacit kvacit ||51.10|| (…) atiprasaktau tau dṛṣṭvā sarvavrajavicāriṇau | nāśaknuvad vārayitum nandagopaḥ sudurmadau ||51.12|| tato yaśodā saṃkruddhā kṛṣṇaṃ kamalalocanam | ānāyya śakaṭīmūlaṃ bhartsayantī punaḥ punaḥ ||51.13|| |

| 15 | It has to be noted that after 13ab, the manuscripts from the south insert the following passage: uvāca śiśurūpeṇa carantaṃ jagataḥ prabhum | ehi vatsa piba stanyaṃ durvoḍhuṃ mama saṃprati || etāvantam itaḥ kālaṃ kvā gato ’si gṛhād bahiḥ | ity ādāya kare putraṃ gṛhān nirvāsya sā ruṣā |51.13ab*642|| |

| 16 | (See Couture and Chojnacki 2014, pp. 129–47). This Jātaka certainly had a previous life of its own, from an oral version that I would presume to be located in the north of India, given the history of the narratives incorporated in the Jātaka corpus. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | Bhagavadgītā 11.45–46 (Mahābhārata 3.25–42). |

| 19 | In very few cases the Kṛṣṇa of the Mahābhārata, the adult counterpart of the child Kṛṣṇa, is represented and then the iconography which is used is the same as the one of the Hindu Viṣṇu, the supreme, adult deity whose four arms and attributes are conspicuous characteristics (Schmid 1997, pp. 75–77). |

| 20 | Balarāma is said to fight the ass demon Dhenuka and Pralamba, a demon of human appearance, in Harivaṃśa but it is not possible to distinguish between the exploits of Kṛṣṇa and the ones attributed in this text to his brother. Moreover, Balarāma’s deeds, like the fight against the ass, are said to be Kṛṣṇa’s works in some texts, including the Mahābhārata (Podzeit 1992; Schmid 2010, p. 290). |

| 21 | |

| 22 | The two episodes of the cart and of Pūtanā follow each other in the same chapter of the Harivaṃśa; they were gathered on the Maṇḍor relief, as well as in the contemporaneous cycle of carvings from Deogarh (Madhya Pradesh; Figure 5). |

| 23 | The Halmidi inscription is considered the earliest bilingual Sanskrit and Kaṇṇada inscription (Mysore Archaeological Department 1938, pp. 72–74). It was found in the Hassan district in which are situated the sites of Bādāmī and Paṭṭadakal. One of the bilingual inscriptions was found in Bādāmī itself. |

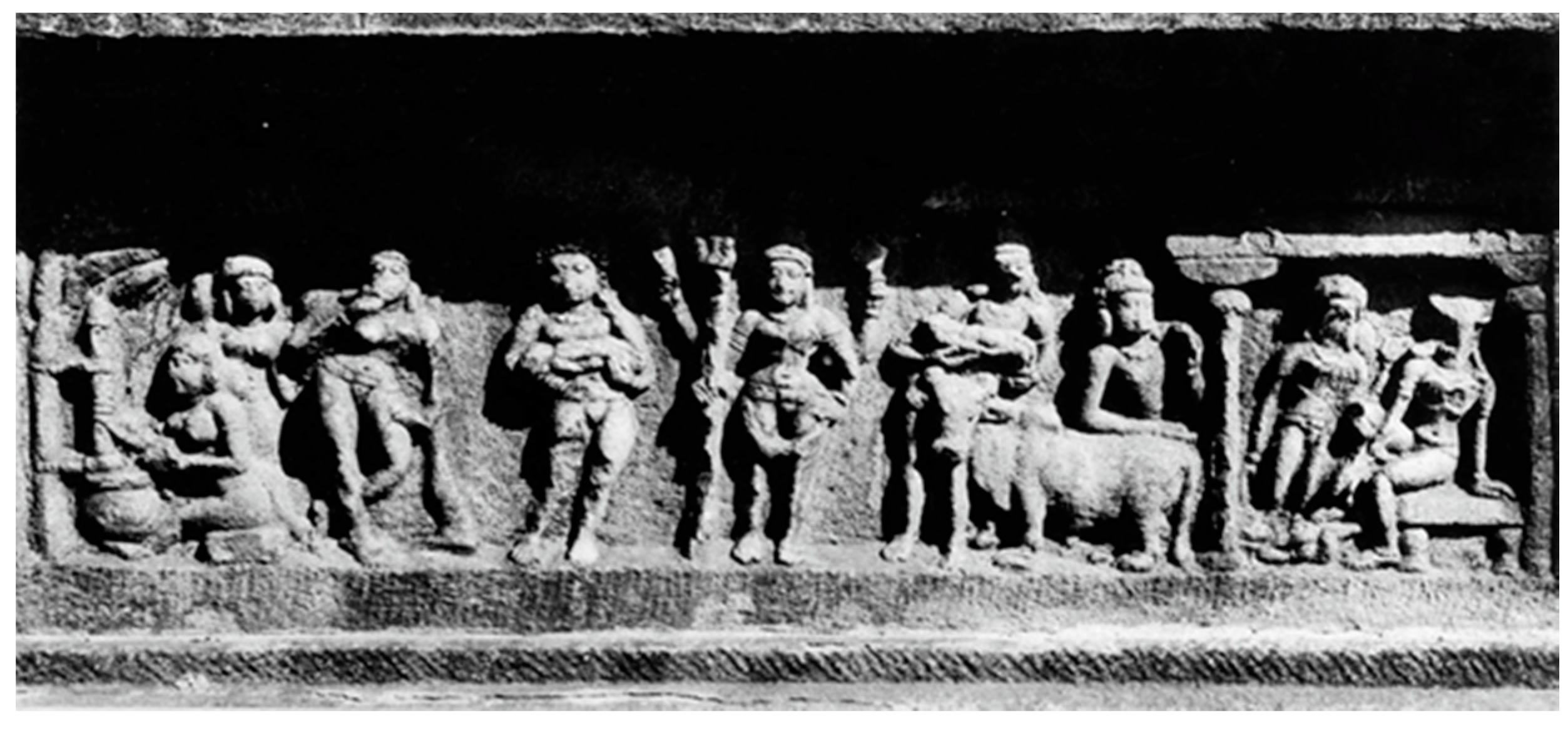

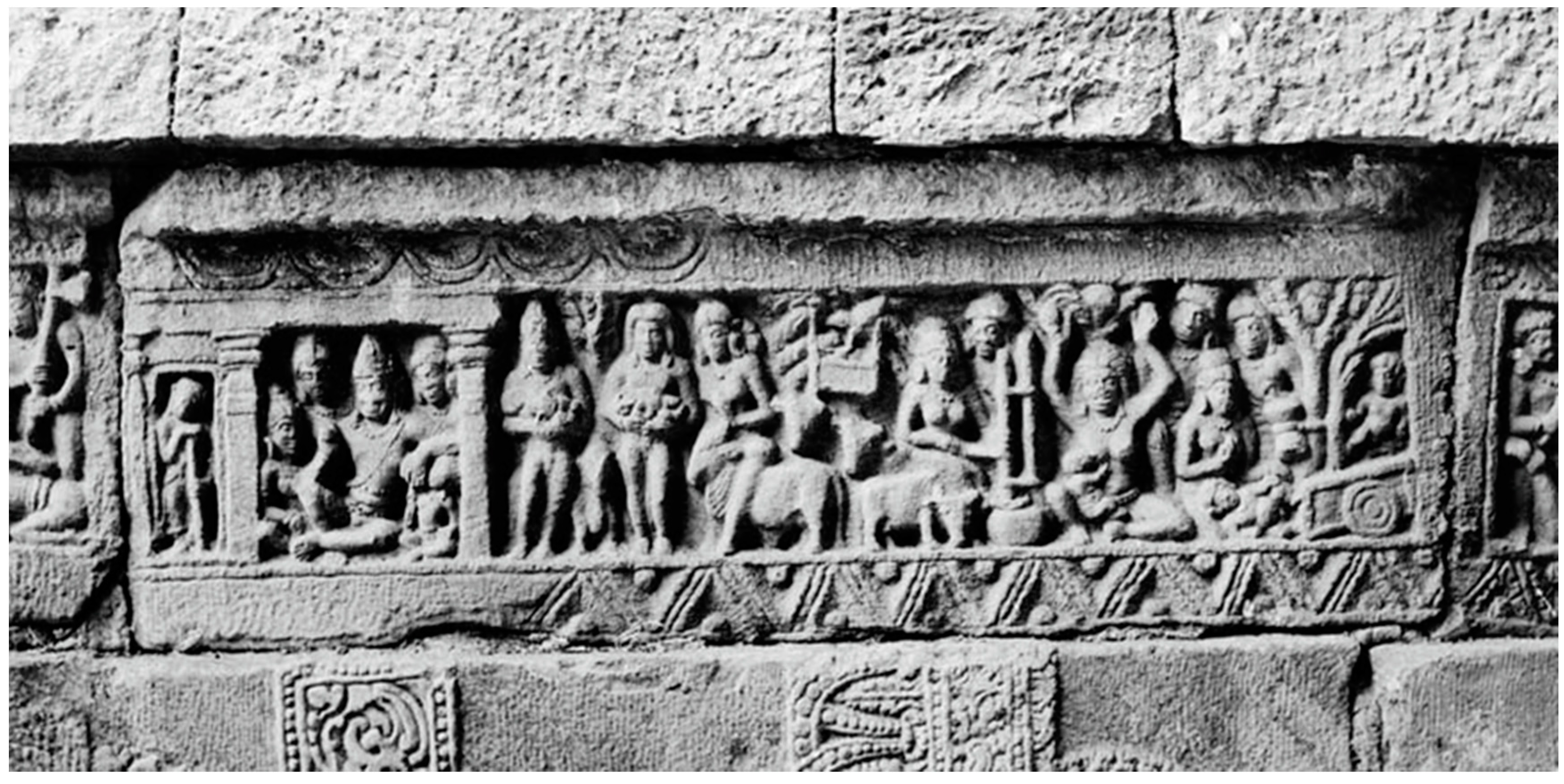

| 24 | The churning of butter is depicted before the Pūtanā episode according to the order of events that seems the more logical if we follow the texts. To the other side of the churning of butter is the exchange of babies or another scene alluding to the arrival of Kṛṣṇa to the cowherd village (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9); in Figure 10 events are presented in an exploded perspective, but Pūtanā has been depicted just before or after the churning. |

| 25 | Ṛgveda 8.43.10, transl. (Griffith 1973, p. 429). |

| 26 | lelihyase grasamānaḥ samantāl lokān samagrān vadanair jvaladbhiḥ | tejobhir āpūrya jagat samagraṃ bhāsas tavogrāḥ pratapanti viṣṇo ||30||. |

| 27 | Akanāṉuṟu 59 features one Māl (Viṣṇu) playing on the banks of the Yamunā but this poem is a late addition to the anthology, of the same age than Kalittokai and Paripāṭal (Wilden 2018, pp. lviii–lix). |

| 28 | vaṭavaraiyai mattu ākki vācukiyai nāṇ ākki kaṭal vaṇṇaṉ paṇṭu oru nāḷ kaṭal vayiṟu kalakkiṉaiyē kalakkiya kai acōtaiyār kaṭai kayiṟṟāl kaṭṭuṇ kai malark kamala untiyāy māyamō maruṭkaittē aṟu poruḷ ivaṉ eṉṟē amarar kaṇam toḻutu ētta uṟu paci oṉṟu iṉṟiyē ulaku aṭaiya uṇṭaṉaiyē uṇṭa vāy kaḷaviṉāṉ uṟi veṇṇey uṇṭavāy vaṇ tuḻāy mālaiyāy māyamō maruṭkaittē. |

| 29 | tiraṇṭu amarar toḻutu ēttum tirumāl niṉ ceṅ kamala iraṇṭu aṭiyāṉ muu ulakum iruḷ tīra naṭantaṉaiyē naṭanta aṭi pañcavarkkut tuutu āka naṭanta aṭi maṭaṅkalāy māṟu aṭṭāy māyamō maruṭkaittē Cil. 17.32–34. |

| 30 | Before Viṣṇu incarnates in the form of a baby (śiśu), Brahmā tells him: “You will have to grow like in days of yore you were able of a triple pace…” HV 45.39; the parallel is enhanced by the fact that Kāśyapa is the father of both the dwarf and Kṛṣṇa (under the form of Vāsudeva for the latter). |

| 31 | neym muṟai namakku iṉṟu ām eṉṟu aiyai taṉ makaḷaik kuuuy kaṭai kayiṟum mattum koṇṭu iṭai mutumakaḷ vantu tōṉṟum maṉ Cil. 17.1.7–10. |

| 32 | kuṭap pāl uṟaiyā kuvi imil ēṟṟiṉ (…) maṭak kaṇ nīr cōrum varuvatu oṉṟu uṇṭu (…) Cil. 17.2.1–2. |

| 33 | From the fifth century onward, writing practices gradually became more common in a world where it was first essentially used for marking one’s ownership or for commercial and accounting purposes, as can be deduced from the corpus of more than 800 Tamil-Brāhmī inscriptions on potsherds published between the end of the 19th century and today. See Mahadevan (2003) for a presentation of early Tamil epigraphy and the history of writing in this part of the Indian peninsula, to be complemented by Rajan (2015) for more recent discoveries and hypothesis. |

| 34 | (Gros 1968, p. L; Hardy 1983, pp. 204–5; Schmid forthcoming). |

| 35 | The kuruntu story may be alluded to in Akanāṉuṟu 59 according to Hardy (1983, pp. 193–96), but as a late addition to this anthology, to be connected to Paripāṭal (see supra, note 27). This poem seems to us being in between the northern arjuna tree motif and the kuruntu finally developed in the south. (Schmid 2014, pp. 48–53). |

| 36 | |

| 37 | |

| 38 | According to H. J. H. Tieken (Tieken 2001, pp. 138–43; 2003), Caṅkam texts were invented to create a literary background for Bhakti poetry, at a time thus when these texts started to be composed, from the six–seventh century only. |

| 39 | Similarly, in the Bhakti corpora butter is one substance of baths given to deities. Inscriptions also kept echoing a practice which continues today to be a “real” one. |

| 40 | […] when the weighty girl joined [her] moist lids, With [her] soft body cooled with green oil, adorned With moistness in an oil (ney, ghee) bath, adorned with white mustard, While [her] son sleeps with [his] foster-mother, fragrant of new Birth, on the bed with soft cloth spread out to have perfume (?), —because one is born who bears the name of [his] elder. Naṟṟiṉai 40. (Text and transl. Wilden 2008, pp. 138–39). |

| 41 | The same ney designates butter and ghee. Fumbling with ghee (ney) and incense, [our] cloth is stained with dirt and [our] shoulders, embracing [our] son, While sweet milk drizzles from [our] soft breasts with beauty spots smell of the newly born. Naṟṟiṉai 380 (text and transl. Wilden 2008, pp. 818–19). The same use of butter is found in the Divyaprabandham where cowherds and people from the mountains celebrate Kṛṣṇa’s birth by covering themselves with butter and dancing, infra, note 71. |

| 42 | When the churning-stick’s base thunders, in motion to clear the butter, In the milk-mixture (?), [its] foot (?) diminished, eaten away but the cord, In the pot filled to the brim, smelling of wood-apple, In the oncoming dawn that remains she would go, [her] body disguised, on her leg the anklets unfastened (?) Naṟṟiṉai 12. (text and transl. Wilden 2008, pp. 82–83). |

| 43 | cuṭumaṇ tacumpiṉ mattam tiṉṟa piṟava veṇṇi urupp’ iṭatt’aṉṉa uvar eḻu kaḷari ōmaiyam kāṭṭu Naṟṟiṉai 84 (text and transl. Wilden 2008, pp. 226–27). |

| 44 | Kuṟuntokai 106.5–6. (Text and transl. Wilden 2010, pp. 290–91). |

| 45 | (Transl. Hart and Heifetz [1999] 2002, p. 225). See the butter that makes the spear to glitter in Puṟanāṉūṟu 95 or the one used to cook delicious dishes in Puṟanāṉūṟu 379.9, 596. |

| 46 | On the contrary the poet of 396 asks himself if he should sing of his fragrant rice with ghee poured upon it. |

| 47 | Puṟanāṉūṟu 166, 2 (Hart and Heifetz [1999] 2002, p. 108); see also Puṟanāṉūṟu 15 (Hart and Heifetz [1999] 2002, pp. 12–13), in which oblations rose rich in butter and other elements of the sacrifice. |

| 48 | (See Gros 1968, pp. L–LI; Schmid forthcoming). |

| 49 | The only combat mentioned in the Mahābhārata is against Keśin, where, of course, it is not associated with childhood; it has a peculiar status and significance. (See Schmid 1999). |

| 50 | For commentary on this verse (iṭavala kuṭaval kōvala kaval) (see Gros 1968, pp. L–LI; Hardy 1983, p. 205), for whom kutam (in kuṭam aval) may mean “west,” but the rest of the line goes against this interpretation, which is proposed only in brackets by F. Hardy. |

| 51 | (Text and translation, Gros 1968, pp. 144–49). |

| 52 | For a general overview (Brereton and Jamison 2020, pp. 46–47); the authors note (p. 173) that it is surprising not to see the churning to appear in those texts where butter is such an important element of rituals. |

| 53 | On the tinai, (See Ramanujan [1967] 1994; Takanobu 1995). On the relationship between mullai tiṇai and Kṛṣṇa (see Hardy 1983, pp. 157–67), though it is possible that the poems studied by F. Hardy as “kuṟiñci tinai” are actually oriented as mullai. We would venture to suggest that these poems belong to a stage when Kṛṣṇa as a youth became one of the incarnations of a Tamil deity of youth of whom, up until that time, Murukaṉ was the main embodiment. |

| 54 | Convinced of the existence of a folk milieu where Kṛṣṇa’s stories were elaborated, F. Hardy does not mention butter, much less note its significance. |

| 55 | pal ūḻ tayir kaṭaiya tāaya puḷḷi mēl kol ēṟu koṇṭāṉ kuruti mayakkuṟa pullal em tōḷiṟku aṇi ō em kēḷ ē. |

| 56 | akal āṅkaṇ aḷai māṟi alamantu peyarum kāl nakai vallēṉ yāṉ eṉṟu eṉ uyirōṭu paṭai toṭṭa ikalāṭṭi niṉṉai evaṉ piḻaittēṉ ellā yāṉ |

| 57 | aḷai māṟi peyar taruvāy aṟiti ō a ñāṉṟu taḷava malar tataintatu ōr kāṉa ciṟṟāṟṟu ayal iḷa mā kāy pōḻntaṉṉa kaṇṇiṉāl eṉ neñcam kaḷam ā koṇṭu āṇṭāy ōr kaḷviyai allai ō. |

| 58 | Butter noise is heard, not as a distant thing, if the village is close by, when it is the middle of the day… veṇṇey teḻi kēṭkum aṇmaiyāl cēyttu aṉṟi aṇṇaṇittu ūr āyiṉ naṉpakal pōḻtu āyiṉ |

| 59 | kaṭi koḷ iruṅ kāppil pul iṉattu āyar kuṭi toṟum nallārai vēṇṭuti ellā iṭu tēḷ maruntu ō niṉ vēṭkai toṭutara tuṉṉi tantāṅku ē nakai kuṟittu emmai tiḷaittaṟku eḷiyam ā kaṇṭai aḷaikku eḷiyāḷ veṇṇeykku um aṉṉaḷ eṉa koṇṭāy oṇṇutāl. A more literal translation could be as follows: “Hey you, having looked for the nice ones of the shepherds of low tribe (living) in the fenced (village) that is large and densely populated, —A medicine for the squeezing scorpion that your desire is? Having come to join (you), having given the smile I sketched, o you who having seen me of easy access for joining, alas you have taken (me) for a woman easy of access for butter, thinking she (behaves) similarly as (she did) for the white butter. |

| 60 | mattam piṇitta kayiṟu pōl niṉ nalam cuṟṟi cuḻalum eṉ neñcu, A more literal translation could be as follows: “Like a rope (kayiṟu) attached to a churning stick (mattam) (by) your beauty/Having turned around/moving here and there (cuṟṟi) my heart is tossed/whirls.” |

| 61 | evvam mikutara em tiṟattu eññāṉṟum ney kaṭai pāliṉ payaṉ yātum iṉṟu āki kai tōyal māttirai allatu ceyti aṟiyātu aḷittu eṉ uyir. A more literal translation could be as follows: “Affliction (is) increasing on my side, all the time,/ Butter churning milk-like whatever juice it (my life) has then become,/ not knowing any other medicine but the curdling by your hand,/ my life is destroyed!”. |

| 62 | This word and its connotation are first known to us through the commentary of Nakkīraṉ eighth century. (See Buck and Paramasivam 1997). |

| 63 | See, for instance the following stanza by Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār (5.2.3; TP 1360): “Having taken a child form, he ate curd and entered inside me, his slave, / (he who is) the unique one creeping like a heron thief who inside fields plunders kayal fishes— the one of Kūṭalūr!” |

| 64 | The bull fight to gain a young woman’s hand, another motif said to be typical of the south of India, but also a shadow-motif inspired by the demonic bull Ariṣṭa, which in our opinion, is shared by the mullai section of Kalittokai and Cilappatikāram 17, for example (Edholm and Suneson 1972; Hardy 1983, appendix VIII and IX). |

| 65 | Here we use North India to refer to texts composed in Indo-Aryan languages as the Caṅkam and the Bhakti corpus do (vata moḻi, the northern language, the language from the North), but also, of course, to refer to the earliest known carvings. |

| 66 | For this section about the Jain texts (see Couture and Chojnacki 2014). |

| 67 | (See Couture and Chojnacki 2014, pp. 165–92) who do not mention a Tamil tradition. Probably, it did not seem relevant to them in this case. |

| 68 | See, for instance, the labels of Banerjee (1978) to the Figures 9, 11, 14 and 19 “dadhi-manthana”; still P. Banerjee uses the expression “Krishna stealing butter” about one of them, p. 138. In this work, Tamil Nadu is present only for the large relief of Mahābalipuram, on which the churning itself is not represented. On a relief dated to the 11th century from Bhubanesvar (Banerjee 1978, Figure 48) a milkmaid looks at a little boy tasting her butter with tenderness, while a male figure lovingly watches them. Since this piece has been carved after the theft of butter has appeared in texts, including the Sanskrit Bhāgavata-purāṇa, it shows that the tradition of depicting a churning without any implication of theft has continued for some time. |

| 69 | Pēyāḻvār, Poikaiyāḻvār, Tiruppānāḻvār, Tirumaḻicaiyāḻvār, Periyāḻvār, Kulacēkara Āḻvār, Nammāḻvār, and Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār feature the butter theft. More than 200 mentions are found in the Divyaprabandham. |

| 70 | Āṇṭāḷ’s work is an interesting case, as she is specifically associated with Periyāḻvār who plays on the motif so many times, while, if Āṇṭāḷ mentions the churning milkmaids and the poisonous milk of Pūtanā (Tiruppāvai 7, TP 480; Nācciyār Tirumoḻi 3.9, TP 532…), the butter-eater goes unnoticed in her works. In a sole stanza Āṇṭāḷ alludes to the tying to the mortar, but as an allusion to the uprooting of the trees without mentioning the butter, just like the Harivaṃśa (Nācciyār Tirumoḻi 12.8, TP 624). In Āṇṭāḷ’s corpus butter is one element of rituals, to be offered to the god (see Tiruppāvai 27, TP 500 or Nācciyār Tirumoḻi 9.6, TP 592). Nācciyār Tirumōḻi 14.2 (TP 638) allows us to see how to go from one use of the butter to the other when, having been worshipped by cowherds celebrating the uplifting of the Govardhana, Kṛṣṇa is said to have a smelly odor of butter. |

| 71 | See Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār, Ciṟiyatirumaṭal 33 (TP 2690) that reminds us of the importance of the association with a pot; in this regard see also Periyāḻvār 16 and 17 where the cowherds celebrate Kṛṣṇa’s birth by emptying pots full of curd and butter, to dance on them, while the forest-dwellers dance having smeared themselves with butter. |

| 72 | See also Pēyāḻvār 91 (TP 2372); Kulacēkara Āḻvār 2.4 (TP 661) where the Lord is tied by an angry milkmaid because he has eaten curd, butter, and milk. |

| 73 | The same formulas appear in poems mentioning only the butter, or the ones mentioning the butter and the breaking of the trees (like uṟi mēl vaitta veṇṇey viḻuṅki; veṇṇey viḻuṅka; veṇṇey kaḷavu; veṇṇey uṇṭu). |

| 74 | In the Tamil texts, the uprooting of the trees gave birth to the uprooting of the citrus tree (kuruntu), already mentioned in the Cilappatikāram (17.21.1 kollaiyañ cāraṟ kuruntocitta māyavaṉ). In between the Harivaṃśa, in which the trees are kinds of godlings, and the Bhāgavata-purāṇa, in which they are demi-gods, the arjuna trees can be transformed into a sole, rather demonic, kuruntu (see Schmid 2013, p. 43); see also, supra, notes 26 and 34. |

| 75 | See, for instance, Pēyāḻvār 91 (TP 2372) where Kṛṣṇa devours the milk of the ogress, then the butter and, thus, Yaśodā ties him off. |

| 76 | See Periyāḻvār 2.1 (TP 223), Tirumaḻicai Pirāṉ 37 (TP 788), Tirumaṅkaiyāḻvār Periya Tirumōḻi 3.10.9 (TP 1246), Poykaiyāḻvār 18 (TP 2099), etc. |

| 77 | niṉṟār mukappu-c ciṟitum niṉaiyāṉ vayiṟṟai niṟaippāṉ uṟi-ppāl tayir ney, aṉṟ(u) āycciyar veṇṇey viḻuṅki y-uralōṭ(u) āppuṇṭ(u) irunta perumāṉ aṭimēl, naṉṟ(u) āya tolcīr vayal maṅkaiyar kōṉ kaliyaṉ olicey-t tamiḻmālai vallār, eṉṟāṉum eytār iṭar iṉpam eyti imaiyōrkkum appāl cela-veytuvārē. “Look at him, for having eaten the butter of the cowherdess, he has been fastened”, (aṉṟu, uṭaivaṉ kāṇmiṉ -iṉṟu aycciyarāl aḷai veṇṇey uṇtu, āppuṇṭiruntavaṉē, with a deleted samdhi) comes as a motto in the hymn that this stanza concludes… |

| 78 | The eating of the dirt seems to us as having been inspired by the dust, namely, the substance of earth, that covers Kṛṣṇa while the young deity plays when being scolded and bound to a mortar in Harivaṃśa 51. 7–9. In the Divyaprabandham, mud and butter are two associated substances that cover the body of the god and that he eats. |

| 79 | Such passages, of both the Divyaprabandham and the Bhāgavata-purāṇa, made the devouring Kṛṣṇa of the BhG echo the Epic and Puranic episode of Mārkaṇḍeya, who explores the world inside the body of Nārāyaṇa after having entered the mouth of a sleeping child lying on a banyan leaf who is none other than Kṛṣṇa; on this episode. (See Brinkhaus 2000; Couture 2007, and Schmid forthcoming). |

| 80 | See, for instance, the following stanza of Poykaiyāḻvār: “Tirumāl, Lord who became sky and fire, The restless sea and the wind, Lord sweet as honey and milk, How could you hope to fill your belly With the cowherd-woman’s butter, When you swallowed the whole earth And spewed it up long ago?” (Poykaiyāḻvār 92, TP 2173; transl. Cutler 1987, p. 126). |

| 81 | The approximate number of stanzas mentioning the theme given previously (200, supra, note 68) is an approximate statistical count based on the use of formulas; when one begins studying the motif, it appears that many more stanzas are linked with it. |

| 82 | A. Couture (Couture 1992, p. 129) gives the parallel passage in the southern versions of the Harivaṃśa where “since Kṛṣṇa is born, there is as much ghee as milk.” |

| 83 | |

| 84 | From the top of this doorjamb, we see the Dhenuka episode, the Kāliya, the Pralamba, the Ariṣṭa, and the Keśin ones, that is in the order given in the Harivaṃśa but for Dhenuka and Kāliya whose positions were exchanged. The murder of the horse Keśin is the last of the exploits of Kṛṣṇa before he goes to the city of Mathurā, and it marks the end of the deeds of the god as a child. |

| 85 | It is possible that the fragmentary carving of Vārānasī was also associated with a Govardhanadhara, as the only other Kṛṣṇa-devoted piece found in Vārānasī for this period of time is once again a Govardhanadhara (for an ill. Banerjee 1978, Figure 48). It is tempting to associate the two in the light of the other representation of the Govardhana episode. |

| 86 | The Govardhana story is told in three chapters of the Harivaṃśa, while other exploits are told in only one chapter or half a chapter, but for the Kāliya episode, which is told in two chapters. These two deeds have special significance in Kṛṣṇa’s legend and are also, by far, the most often represented in carvings. |

| 87 | From one site to another from the sixth to eighth century, Balarāma wears the same headdress and costume; he similarly lifts his proper right hand as if willing to help his brother support the mountain or paying him an admiring tribute. |

| 88 | The dates of the rock-cut remains at Mahābalipuram are still debated; in agreement with most authors we think the Govardhanadhara relief was done at the end of the end of the sixth or at the beginning of the seventh century. |

| 89 | (See Schmid 2014, pp. 43–56). |

| 90 | For the impact on the Muslim Indian world (Hawley [1983] 1989, pp. 11–12). J. S. Hawley has published several studies where he questions the literary, sociological, and political elaboration of the journey of the Bhakti movement said to have been travelling from south to north (Hawley 2015 for more). Regarding the circulation from north to south, and south to north (See Schmid 2014; Francis and Schmid 2014); where specificities of the contribution of the south are alluded to. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmid, C. The Carving of Kṛṣṇa’s Legend: North and South, Back and Forth. Religions 2020, 11, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090439

Schmid C. The Carving of Kṛṣṇa’s Legend: North and South, Back and Forth. Religions. 2020; 11(9):439. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090439

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmid, Charlotte. 2020. "The Carving of Kṛṣṇa’s Legend: North and South, Back and Forth" Religions 11, no. 9: 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090439

APA StyleSchmid, C. (2020). The Carving of Kṛṣṇa’s Legend: North and South, Back and Forth. Religions, 11(9), 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090439