Abstract

The general vorticity equation for turbulent compressible 2-D flows with variable viscosity is derived, based on the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, and simplified versions of it are presented in the case of turbulent or cavitating flows around 2-D hydrofoils.

1. Introduction

The vorticity equation has been utilized by several authors in the past to analyze the viscous flow around bodies. Vortex element (or particle, or blub) and vortex-in-cell methods have been used for several decades for the analysis of 2-D or 3-D flows, as described in Chorin [1], Christiansen [2], Leonard [3], Koumoutsakos et al. [4], Ould-Salihi et al. [5], Ploumhans et al. [6], Cottet and Poncet [7], and Cottet and Poncet [8]. Those methods essentially decouple the vortex dynamics (convection and stretching) from the effects of viscosity.

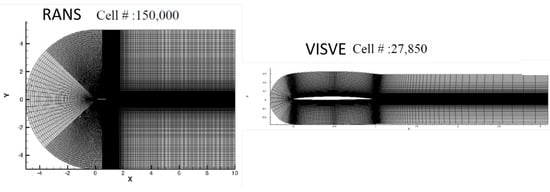

In recent years, the VIScous Vorticity Equation (VISVE), has been solved by using a finite volume method, without decoupling the vorticity dynamics from the effects of viscosity. This method has been applied to 2-D and 3-D hydrofoils, cylinders, as well as propeller blades as described in Tian [9], Tian and Kinnas [10], Wu et al. [11], Wu and Kinnas [12], Wu et al. [13], Wu and Kinnas [14]. The major advantage of this approach is that it requires a significantly smaller computational domain than RANS over which VISVE must be solved, as shown in Figure 1, due to the fact that the vorticity vector vanishes much closer to the body surface (in the order of 1–3 maximum body thickness), as opposed to the velocity vector which vanishes much farther (in the order of 5–10 body lengths) from the body surface. Due to the significantly smaller domain, VISVE requires a much smaller number of cells (5–50 times smaller) than RANS for the same accuracy of the predictions, and subsequently, a significantly smaller CPU time, as reported in Wu et al. [11].

Figure 1.

Typical domain and grids for flow around hydrofoil, from RANS with 150K cells (left) and from VISVE with 28K cells (right). Note the image on the right is drawn at a larger scale than that on the left.

All applications of VISVE mentioned above have addressed laminar flow of an incompressible fluid. However, in the case of incompressible turbulent flow the vorticity equation must be modified since the viscosity (molecular + turbulent) varies within the flow. In addition, in the case of cavitating flow, treated via a mixture model, both the density and the viscosity vary within the flow. In this work the general equation in terms of the mean vorticity is derived in the case of turbulent flows with variable density and viscosity, and then simplified in the case of turbulent or cavitating flows around 2-D hydrofoils.

3. Vorticity Equation in 2D

We consider 2D flow, in which case , , ; , , ; and . The velocity has two components: , and the vorticity has only one component in the y direction . As shown in the Appendix A the vorticity equation will become as follows:

3.1. 2D Flow of Fluid with Constant Density

In that case , , , and . Then Equation (9) reduces to:

or, by expressing in the second term on the RHS of Equation (10), and by making use of the continuity equation, , we get:

It is worth noting that Equation (10) is valid for turbulent flows (with the vorticity being the mean vorticity), but the turbulent kinetic energy k is not involved in the equation.

In the case of laminar flow of Newtonian fluid , Equation (10) becomes the vorticity equation in its most common diffusion equation form:

or, since :

3.2. 2D Flow around Hydrofoil

In that case we assume that the hydrofoil is placed along axis x, with the inflow also along x axis, and that , especially within the narrow region close to the hydrofoil and its wake where . Then, as shown in the Appendix A, Equation (9) reduces to:

4. Conclusions and Future Work

The vorticity equation (in terms of the mean vorticity) is derived in the case of turbulent flows with variable density and viscosity, and its simplified version in the case of flows around 2-D hydrofoils has been provided. Equation (14) has already been implemented by Yao and Kinnas [15] to address the turbulent non-cavitating flow around 2-D hydrofoils and cylinders, as well as the cavitating laminar flow around 2-D hydrofoils, using the mixture model, by Xing et al. [16].

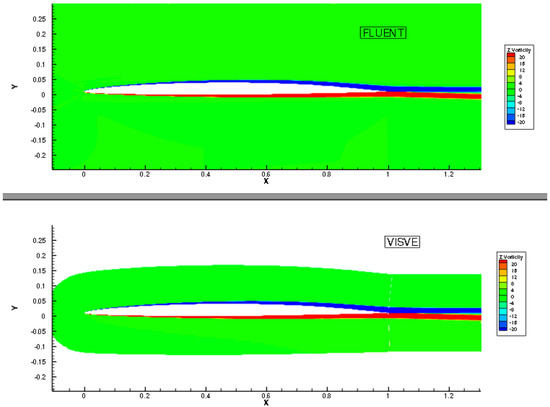

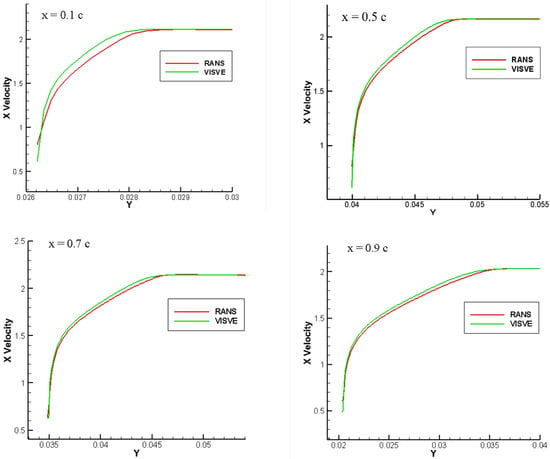

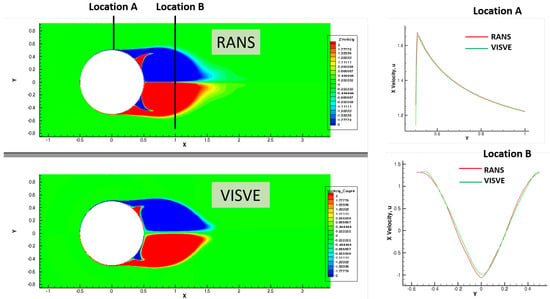

Representative results from the work of Yao and Kinnas [15] are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 together with results from RANS by using the commercial code ANSYS/Fluent (https://www.ansys.com/products/fluids/ansys-fluent). In this case Equation (14) was used where the turbulent viscosity was evaluated by synchronous coupling of VISVE with the open source RANS code OpenFOAM (https://www.openfoam.com/). As described in more detail in Yao and Kinnas [15], at every time step the velocities determined by VISVE were passed into the part of OpenFOAM which solved the k, equations and then returned the turbulent kinematic viscosity back to VISVE, in order to solve Equation (14) with the updated values of the kinematic viscosity.

Figure 2.

Vorticity contour plots from RANS (ANSYS/Fluent, top) and VISVE (bottom) for turbulent flow around hydrofoil. .

Figure 3.

Velocity profiles of turbulent flow around hydrofoil, from RANS (ANSYS/Fluent) and from VISVE, at different locations along the chord, c, on the suction side. .

Figure 4.

Vorticity contour plots and velocity profiles for turbulent flow over cylinder from RANS (ANSYS/Fluent) and from VISVE, at t = 4 s and .

In the case of the hydrofoil the velocity profiles predicted by VISVE, shown in Figure 3, are in good agreement to those predicted by RANS. It should be noted that the hydrofoil assumption has also been used in the case of the cylinder, for which results are shown in Figure 4. The results from VISVE compare well with those from RANS, even though with somewhat larger differences downstream of the cylinder, up to the time shown in the figure, but deteriorate for later times as shown in Yao and Kinnas [15], once asymmetry appears between the top and bottom flow (not shown in this paper).

In the future, the author and his students intend to assess numerically the effect of the last three terms in the right-hand side of Equation (10), on the prediction. These terms are currently ignored, but they might affect the accuracy of predictions, especially in the case of a hydrofoil at high angles of attack where the hydrofoil assumptions, made in this paper, would not hold. The ultimate objective of this research is to extend VISVE in the case of turbulent flows around 3-D hydrofoils, and eventually propeller blades.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the U.S. Office of Naval Research (Grant Number N00014-18-1-2276; Ki-Han Kim) and by Phase VIII of the “Consortium on Cavitation Performance of High Speed Propulsors”.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Proofs

Appendix A.1. How to Get from Equation (1) to Equation (3)

We consider the component of Equation (1):

with the term meant in the Einstein notation with

We then consider the rate of strain term of the expression for , as given by Equation (2):

where is the Levi-Civita symbol.

Then for given i and with , using the Einstein notation we have:

where means the component of

Appendix A.2. How to Get from Equation (3) to Equation (4)

Using vector identities we get:

or

Then

Using the equations above we get to Equation (4).

Appendix A.3. How to Get from Equation (5) to Equation (8)

We consider 2D flow, in which case , , ; , , ; and . The velocity has two components: , and the vorticity has only one component in the y direction .

First:

Then by using the identity:

we get

due to the identity:

Then using the following identities:

We get:

Now, in 2-D, since the vortex stretching term , the above equation becomes:

We now take the of each term on the RHS of Equation (5):

The combination of the of the 4th and the 5th terms will give us:

The last two terms above can also be rewritten by using and , which renders the RHS of Equation (8)

Appendix A.4. How to Get from Equation (8) to Equation (9)

In 2D and , and

or

where we have made use of

We finally get to Equation (9) by considering the identity:

Appendix A.5. How to Get from Equation (9) to Equation (14)

In that case we assume that the hydrofoil is placed along axis x, with the inflow also along x axis, and that , especially within the narrow region close to the hydrofoil and its wake where .

Then, since we ignore then all point in the z direction and thus . In addition the following approximations can be made:

By adding the approximate expressions for all the terms shown above we get

Finally we get to Equation (14) by making the following approximation:

References

- Chorin, A.J. Numerical study of slightly viscous flow. J. Fluid Mech. 1973, 57, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, I. Numerical simulation of hydrodynamics by the method of point vortices. J. Comput. Phys. 1973, 13, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, A. Vortex methods for flow simulation. J. Comput. Phys. 1980, 37, 289–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumoutsakos, P.; Leonard, A.; Pepin, F. Boundary conditions for viscous vortex methods. J. Comput. Phys. 1994, 113, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ould-Salihi, M.L.; Cottet, G.H.; El Hamraoui, M. Blending finite-difference and vortex methods for incompressible flow computations. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2001, 22, 1655–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploumhans, P.; Winckelmans, G.; Salmon, J.K.; Leonard, A.; Warren, M. Vortex methods for direct numerical simulation of three-dimensional bluff body flows: Application to the sphere at Re= 300, 500, and 1000. J. Comput. Phys. 2002, 178, 427–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottet, G.H.; Poncet, P. Particle methods for direct numerical simulations of three-dimensional wakes. J. Turbul. 2002, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottet, G.H.; Poncet, P. Advances in direct numerical simulations of 3D wall-bounded flows by Vortex-in-Cell methods. J. Comput. Phys. 2004, 193, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. Leading Edge Vortex Modeling and Its Effect on Propulsor Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Ocean Engineering Group, CAEE, UT Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Kinnas, S.A. A Viscous Vorticity Method for Propeller Tip Flows and Leading Edge Vortex. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Marine Propulsors, SMP15, Austin, TX, USA, 31 May–4 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Xing, L.; Kinnas, S.A. A Viscous Vorticity Equation (VISVE) Method applied to 2-D and 3-D hydrofoils in both forward and backing conditions. In Proceedings of the 23rd SNAME Offshore Symposium, Houston, TX, USA, 14 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Kinnas, S.A. A 3-D VIScous Vorticity Equation (VISVE) Method Applied to Flow Past a Hydrofoil of Elliptical Planform and a Propeller. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Marine Propulsors, SMP19, Rome, Italy, 26–30 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Kinnas, S.A.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y. A conservative viscous vorticity method for unsteady unidirectional and oscillatory flow past a circular cylinder. Ocean Eng. 2019, 191, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Kinnas, S.A. Parallel Implementation of a VIScous Vorticity Equation (VISVE) Method in 3-D Incompressible Flow. J. Comput. Phys. 2019. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Kinnas, S.A. Coupling Viscous Vorticity Equation (VISVE) Method with OpenFOAM to Predict Turbulent Flow Around 2-D Hydrofoils and Cylinders. In Proceedings of the 29th International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 16–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, L.; Wu, C.; Kinnas, S.A. VISVE, a Vorticity Based Model Applied to Cavitating Flow around a 2-D Hydrofoil. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Cavitation (CAV2018), Baltimore, MD, USA, 14–16 May 2018; ASME Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).