Abstract

Unmanned vehicles have become a part of everyday life, not only in the air, but also at sea. In the case of sea, until now this usually meant small platforms operating near shores, usually for surveying or research purposes. However, experiments with larger cargo vessels, designed to operate on the high seas are already being carried out. In this context, there are questions about the threats that this solution may pose for other sea users, as well as the safety of the unmanned vehicle itself and the cargo or equipment on board. The problems can be considered in the context of system reliability as well as the resilience to interference or other intentional actions directed against these objects—for example, of a criminal nature. The paper describes the dangers that arise from the specificity of systems that can be used to solve navigational problems, as well as the analysis of the first experiences of the authors arising from the transit of an unmanned surface vessel (USV) from the United Kingdom to Belgium and back, crossing the busiest world shipping route—the English Channel.

1. Introduction

Autonomous vehicles, such as drones in the air, will be extensively used at sea in the near future. This trend seems to be increasingly accepted by the marine community, primarily for economic reasons. Autonomous ships are considered mainly in the context of cost reduction. Currently, autonomous or remotely controlled platforms are used at sea, primarily as carriers of various measuring devices. This applies particularly to hydrography, oceanography and off-shore technologies. However, these are still operations carried out mostly nearshore, usually in controlled test areas or outside the shipping routes.

Many companies, mostly from Scandinavian countries and Japan, are working on full-size autonomous ships with the goal of obtaining cargo vessel or even passenger vessel capabilities. Kongsberg and Rolls-Royce seem to be conducting the most advanced work. They have just received funding from the European Commission (the ‘Autoship’ project) in the amount of 20 million euro from 27.6 million of the total project costs [1]. In this framework, within two and a half years, two autonomous ships will be built with the option of remote control and all the necessary infrastructure. The tests are to be carried out during the two pilot demonstration campaigns on the sea routes from the Baltic corridor to the largest ports of the European Union. It can be expected that the success of these experiments will also lead to the fact that in the future some existing ships will be reconstructed to such a standard, which may prove to be a cheaper solution.

Rolls-Royce together with the Finnish ferry operator Finferries demonstrated the passage of the ferry ‘Falco’ between Parainen and Nauvo, south of Turku, Finland, in December 2018. The ferry navigated autonomously, including the collision avoidance maneuver. Some part of the passage was done in the remote control mode. Rolls-Royce and Finferries are now engaged in the SVAN research project (Safer Vessel with Autonomous Navigation). It is the continuation of the earlier Advanced Autonomous Waterborne Applications (AAWA) research project, funded by Business Finland [2].

Kongsberg has experience in working on autonomous vessels development after the common project with Yara on world’s first autonomous and zero emissions container ship. Norwegian shipbuilder Vard has been selected to build the vessel. It is planned to be ready to operate ‘YARA Birkeland’ completely autonomously by the year 2022 [3]. It should be noted that in April 2019 Rolls-Royce Commercial Marine was acquired by Kongsberg Maritime, and they are now fully integrated, so the autonomous shipping projects are being conducted under the new organizational frame [4].

MUNIN (Maritime Unmanned Navigation through Intelligence in Networks) is another project in this field. Research undertaken between 2012 and 2015 resulted in the description of the concept of evolution from manned to unmanned vessels, through redesigning of the ships’ key tasks [5].

Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) are often considered also as unmanned objects, requiring a new approach in regulation and legislation. However, from the point of view of ocean-going autonomous ships development this is a slightly different challenge. AUVs are mostly used in the close vicinity of mother vessel, due to the positioning methods used in this kind of operation. But there are systems which utilizes both underwater and surface vehicles with no human presence, becoming the cutting-edge means of marine environment exploration, but also facing challenges related to both types of vehicles. The winning solution of the recently completed global competition called Shell Ocean Discovery XPRIZE may be an example of the successful cooperation between underwater and surface vessels in order to obtain high-quality data about the seafloor. GEBCO-NF Alumniteam (name after General Bathymetric Chart of the Ocean and Nippon Foundation) developed a system consisted of the AUV Hugin, equipped with a high-resolution synthetic aperture echosounder and multibeam echosounder, positioned from the surface by the unmanned surface vessel SEA-KIT [6,7,8]. The same vessel a couple of months later completed the first unmanned passage between Tollesbury in Great Britain to Ostend in Belgium and back, being controlled only by the operators located on shore [9,10]. The USV’s route crossed the busiest shipping route in the world.

The beginning of coexistence of manned and unmanned vessels, especially autonomous sea-going vessels, in the same areas at sea, provokes many questions and objections. The most important ones, considering the scope of the paper, are the questions of how to guarantee that autonomous vessels will be at least as safe as modern crewed vessels, while operating in the same areas. Undoubtedly, this is a technological challenge, but there is also a challenge for legislation. It will certainly require corrections to many existing documents and rules, already adopted by the marine community and international treaties. New regulations will affect the variety of issues related to transport of goods, shore infrastructure, insurances, etc. However, the fundamental questions are those related to the effective safety and risk management of this kind of vessel.

Classifying societies (for example Bureau Veritas, DNV GL, Lloyd’s Register, CCS) and IMO (International Maritime Organization) defined their views on the issue of the construction of unmanned/autonomous ships, usually in the form of guidelines [11,12,13,14,15]. Unfortunately, in terms of the approach to navigation issues, these are usually quite general statements, similar to: ‘the data from various ship’s sensors should be gathered and evaluated in order to thoroughly determine the location and heading of the ship. Redundant sensors and positioning by multiple sources should ensure a high degree of data accuracy. The current speed and water depth should be monitored as well’.

More specific information is contained in [16] however they refer to the possibilities of the engine room autonomy assurance. Eder, in turn, is considering primarily the adequacy of legal documents that currently apply to the perspective of ships without crew [17].

Gu et al. in [18] performed an in depth review of literature on autonomous ships with the conclusion that a lot of publications about the design and safety of such kind of vessels exists, although in the majority of them the navigational aspect is understood as the planning of the trajectory and its realization as the steering process of the vessel. The problem of data acquisition to the steering is somewhat overlooked. Finally, the authors of [18] suggest that it is the right time to shift the research focus from the basic control and safety studies to transportation and logistics applications.

In this paper, the authors decided to focus on the navigational aspects of unmanned and autonomous vessels. The role of the Officer of the Watch tends towards being augmented or even replaced by the systems related to the autonomous navigation and automated collision avoidance. Those two aspects, with associated threats and possible solutions, will be presented in the next sections.

The main motivation of the authors of this paper to analyze this issue was the active participation in the tests of USV ‘Maxlimer’—The unmanned vessel of SEA-KIT type, mentioned above, including her passage through the North Sea, crossing the entrance to the English Channel. Observations of the navigational watch conducted on land, undertaken during this passage and earlier tests, led to the conclusions, listed in Section 4.

4. The Case of the First Unmanned Ship Crossing the English Channel

The segment of unmanned vessels is now one of the most important areas for research and marine technology development. There are numerous simulations being conducted to predict marine processes. Many real vessels, from small sizes model boats to larger ships, are tested in various testing areas. Finland is a pioneer in establishing a dedicated area for autonomous vessels testing. The Jaakonmeri Test Area, 17.8 km long and 7.1 km wide, is managed by DIMECC, the company leading e.g., the One Sea—Autonomous Maritime Ecosystem project [47]. This kind of work is essential for technological progress although the real challenge is the use of autonomous and unmanned systems in real navigation situations.

4.1. SEA-KIT—Built, Trials, Unmanned Operations

SEA-KIT has been designed by the UK Company Hushraft Ltd., and built as the part of the GEBCO-Nippon Foundation Alumni Team solution for the Shell Ocean Discovery XPRIZE Challenge [6,7,8]. The requirements of the competition determined the size and functionalities of the vessel. The hull with a detachable mast fits inside the standard 40-feet shipping container, which allows it to be mobilized in any part of the world relatively quickly and cost-effectively. The specification of the vessel is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Specifications of unmanned surface vessel (USV) SEA-KIT ‘Maxlimer’ [6,7,8].

The unusual shape of the hull ensures good stability, necessary for the survey work and the optimal use of space inside the vessel in the situation where the midship part is reserved for the transportation of Autonomous Underwater Vehicle, launched and recovered through the stern part.

The first trials of the new design vessel have been conducted in the United Kingdom. Initially the vessel has been registered as a manned boat, first, due to the lack of regulations related to the unmanned vessel registration, second, to ensure the safety of people working on the boat at the early stages of trials. Since 2017, unmanned vessels can be registered in UK [48] and the status of SEA-KIT has been changed.

Trials of the K-Mate Autonomy Controller and the systems responsible for the cooperation between the surface vessel und the AUV have been conducted on the waters of Oslo Fiord in Norway, mostly on the sheltered area off the Kongsberg Maritime facility in Horten.

The vessel has been exposed to the open sea environment during field tests in Greece, working on the Ionian Sea. The final trial of the Shell Ocean Discovery XPRIZE covered 32 h on continuous unmanned, over horizon operation, including launch and recovery of the AUV and 24 h of hydrographic data collection by two cooperating vehicles. The state-of-art seabed mapping operation was easier from the navigator’s point of view because there was no traffic inside the survey area during the challenge.

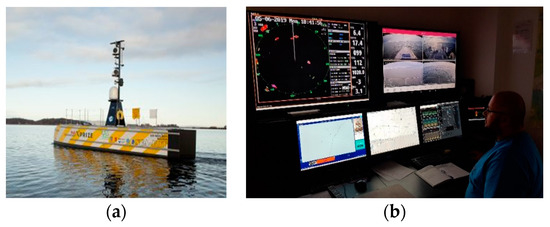

The next stage was to test the technology in real traffic conditions. This kind of test was conducted in May 2019 on the English Channel, the busiest world shipping route (around 400 ships every day, according to [49]) when ‘USV Maxlimer’, (Figure 4a), successfully crossed the channel from Tollesbury in the UK to Ostend in Belgium.

Figure 4.

The first unmanned crossing from the UK to Belgium: (a) The ‘USV Maxlimer’—SEA-KIT type unmanned surface vessel [50]; (b) Master Mariner Karol Zwolak in the shore control station during the transit of the vessel (photo by Karolina Zwolak).

4.2. The Voyage

The vessel has been controlled only from a shore control station (Figure 4b). A K-Mate Autonomy Controller, a product of Kongsberg, was utilized as the shore operator’s decision’s executor and the G-SAVI Global Situational Awareness via Internet system of Hushcraft Ltd., Essex, UK, provided the operators with the navigational and environmental data. The communication between vessel and shore control station was maintained using the Very Small Aperture Terminal (VSAT) satellite system.

It should be underscored, that this project was not an autonomous passage, decisions were taken by humans only, although the route followed was executed in autopilot mode. In some cases the course was set by the operator instead of steering to waypoint methods. But full control of the vessel was executed by the software control over the ship’s mechanisms with no human element on board, which make this passage a good basis for further analysis towards the autonomy of surface vessels.

The situation assessment during the passage was based on a radar image, AIS system information, electronic chart and the CCTV images sent to the control station. The functionality of the workstation was very similar to the usual bridge or helmsman desktop on the smaller size vessel. The only difference was the lack of a simple lookout. The crucial part of the watch is to perform a proper data fusion based on electronic device reads. With some limitations of the CCTV image, especially related to the distance estimation, radar becomes the main device for the collision avoidance decisions.

The CCTV images provide information about objects in the vicinity of the vessel, although the proper recognition of navigational aids and distance estimation is really difficult to perform only based on CCTV. This is a promising area for the implementation of automated image-processing methods for object detection and the recognition of nautical aids.

Another issue, which seems to be crucial for the safety of unmanned vessels operation, is a robust and reliable self-diagnosis system on the unmanned vessel to provide the operator with performance quality indicators and an alarm regarding any malfunctions, loss of input data, unforeseen behavior of specific devices or unexpected changes in positioning, speed, heading and attitude measurements systems data.

Our own experience and numerous discussions with the designer and users of the new class of vessel, which was used for this passage, lead to the conclusion that only the extensive experience of the operators as the crew at sea ensures the seamless transition between a manned vessel’s bridge to the unmanned surface vessel control station. This includes the deep understanding of all the relations between sea users with their habits, usual practices and the restrictions on their performance.

4.3. Lessons Learned from the Participation in the Unmanned Vessel Operation

Based on the considerations above, the following observations have been listed:

- The unmanned and autonomous vessels must be tested in real traffic conditions to obtain non-simulation data for further considerations, although a proper level of information and multiple back-up control methods must be ensured and provided to maintain at least the existing safety level of maritime operations.

- Taking into account all the restrictions related to the situational awareness sensors nowadays, radar provides the most valuable information to the operator on-shore. Improvements to vessels’ radar data transfer on-shore are needed.

- Self-diagnosis systems, including position determining devices, communication and power supply play crucial role in the vessel remote control process and should be taken into account in the autonomous units decision making algorithms. The redundancy of the positioning and movements parameters systems should be ensured, preferably using the cross-check methods.

- In the situation of a lack of regulations for unmanned vessels operator’s qualifications, it is the operating companies’ role to ensure that the proper people control this equipment. The extensive works towards the clarification of theoretical and practical training requirements for MASS operators will certainly be conducted in the near future, although it requires open discussion between education institutions, policy makers and industry representatives, where each voice, based on real experience, will be valuable.

5. Conclusions

The marine community, both research and industry, are working on increasing the ratio of unmanned systems, including full-size vessels, in operations at sea. The levels of control differ on those platforms, from remote operation beyond the line of sight to almost full autonomy on prototype vessels. However, the exploitation of this kind of vessel, at all control levels, requires solving a number of issues regarding the safety of the equipment, potential cargo and other sea users. The possible threats and related development areas have been discussed in this paper together with the author’s experience from the first unmanned transit across the English Channel.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.; methodology, A.F., K.Z.; investigation, A.F., K.Z.; resources, K.Z.; writing—Original draft preparation, A.F., K.Z.; writing—Review and editing, K.Z. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Polish Naval Academy statutory funds for the research activities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the SEA-KIT International Ltd. and Hushcraft Ltd. management for the possibility to actively participate in the first unmanned vessel transit from the UK to Belgium.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Autonomous Shipping Initiative for European Waters. Available online: https://trimis.ec.europa.eu/project/autonomous-shipping-initiative-european-waters#tab-outline (accessed on 9 June 2019).

- Rolls-Royce and Finferries Demonstrate World’s First Fully Autonomous Ferry. Available online: https://www.rolls-royce.com/media/press-releases/2018/03-12-2018-rr-and-finferries-demonstrate-worlds-first-fully-autonomous-ferry.aspx (accessed on 7 June 2019).

- YARA Selects Norwegian Shipbuilder VARD for Zero-Emission Vessel Yara Birkeland. Available online: https://www.yara.com/corporate-releases/yara-selects-norwegian-shipbuilder-vard-for-zero-emission-vessel-yara-birkeland/ (accessed on 9 June 2019).

- Acquisition of Rolls-Royce Commercial Marine. Available online: https://www.kongsberg.com/maritime/about-us/who-we-are-kongsberg-maritime/rolls-royce-commercial-marine-information/ (accessed on 18 December 2019).

- Final Report Summary—MUNIN (Maritime Unmanned Navigation through Intelligence in Networks). Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/104631/reporting/en (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Proctor, A.; Zarayskaya, Y.; Bazhenowa, E.; Sumiyoshi, M.; Wigley, R.A.; Roperez, J.; Zwolak, K.; Sattiabaruth, S.; Sade, H.; Tinmouth, N.; et al. Unlocking the Power of Combined Autonomous Operations with Underwater and Surface Vehicles: Success with a Deep-Water Survey AUV and USV Mothership. In Proceedings of the 2018 OCEANS, Kobe, Japan, 28–31 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zwolak, K.; Simpson, B.; Anderson, R.; Bazhenowa, E.; Falconer, R.; Kearns, T.; Minami, H.; Roperez, J.; Rosedee, A.; Sade, H.; et al. An unmanned seafloor mapping system: The concept of an AUV integrated with the newly designed USV SEA-KIT. In Proceedings of the OCEANS, Aberdeen, UK, 19–22 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zarayskaya, Y.; Wallace, C.; Wigley, R.A.; Zwolak, K.; Bazhenova, E.; Bohan, A.; Elsaied, M.; Roperez, J.; Sumiyoshi, M.; Sattiabaruth, S.; et al. GEBCO-NF Alumni Team Technology Solution for Shell Ocean Discovery XPRIZE Final Round. In Proceedings of the OCEANS, Marseille, France, 17–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SEA-KIT. Complete First ever International Commercial Unmanned Transit. Available online: https://www.oceannews.com/news/science-technology/sea-kit-complete-first-ever-international-commercial-unmanned-transit (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Autonomous Boat Makes Oyster Run. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-48216966 (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Guidelines for Autonomous Shipping. Available online: https://www.bureauveritas.jp/news/pdf/641-NI_2017-12.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Autonomous and Remotely Operated Ships. Available online: http://rules.dnvgl.com/docs/pdf/dnvgl/cg/2018-09/dnvgl-cg-0264.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- ShipRight Procedure—Autonomous Ships. Available online: https://www.lr.org/en/latest-news/lr-defines-autonomy-levels-for-ship-design-and-operation/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Guidelines for Autonomous Cargo Ships. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/search?safe=strict&source=hp&ei=1aweXvm0JtvmwQPM2pvABQ&q=Guidelines+for+Autonomous+Cargo+Ships%3B+CCS%3A+&oq=Guidelines+for+Autonomous+Cargo+Ships%3B+CCS%3A+&gs_l=psy-ab.3..33i160l5.28.28..700...0.0..0.135.135.0j1......0....2j1..gws-wiz.z4POokU6tCs&ved=0ahUKEwi58_qF-YTnAhVbc3AKHUztBlgQ4dUDCAU&uact=5 (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- IMO Takes First Steps to Address Autonomous Ships. Available online: http://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/08-MSC-99-MASS-scoping.aspx (accessed on 19 December 2019).

- Burmeister, H.; Moræus, J. D8.7: Final Report: Autonomous Engine Room. Available online: http://www.unmanned-ship.org/munin/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/MUNIN-D8-7-Final-Report-Autonomous-Engine-Room-MSoft-final.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Eder, B. Inaugural Francesco Berlingieri Lecture. Unmanned Vessels: Challenges Ahead. 2018. Available online: https://comitemaritime.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Sir-Bernard-Eder-Berlingieri-Lecture-London-Assembly-2018-geconverteerd.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Gu, Y.; Góez, J.; Guajardo, M.; Wallace, S.W. Autonomous Vessels: State of the Art and Potential Opportunities in Logistics. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3448420 (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships UK Code of Practice. Available online: https://www.maritimeuk.org/media-centre/publications/maritime-autonomous-surface-ships-uk-code-practice/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Bratić, K.; Pavić, I.; Vukša, S.; Stazić, L. Review of Autonomous and Remotely Controlled Ships in Maritime Sector. Trans. Marit. Sci. 2019, 8, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poikonen, J.; Hyvonen, M.; Kolu, A.; Jokela, T.; Tissari, J.; Paasio, A. Remote and autonomous ships—The Next Steps. Technology. 2016. Available online: https://www.rolls-royce.com/~/media/Files/R/Rolls-Royce/documents/customers/marine/ship-intel/aawa-whitepaper-210616.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Buesnel, G.; Pottle, J.; Holbrow, M.; Crampton, P. Make it Real: Developing a Test Framework for PNT Systems and Devices, GPS World. Available online: https://www.gpsworld.com/make-it-real-developing-a-test-framework-for-pnt-systems-and-devices (accessed on 5 June 2019).

- GPS Disrupted for Maritime in Mediterranean, Red Sea. Available online: https://www.gpsworld.com/gps-disrupted-for-maritime-in-mediterranean-red-sea/ (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Son, P.W.; Rhee, J.H.; Han, Y.; Seo, K.; Seo, J. Preliminary study of the re-radiation effect of Loran signal to improve the positioning accuracy. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, Monterey, CA, USA, 23–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thombre, S.; Bhuiyan, M.; Eliardsson, P.; Gabrielsson, B.; Pattinson, M.; Dumville, M.; Kuusniemi, H. GNSS Threat Monitoring and Reporting: Past, Present, and a Proposed Future. J. Navig. 2018, 71, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Whitworth, T.; Sheridan, K. GNSS interference detection with software defined radio. In Proceedings of the IEEE First AESS European Conference on Satellite Telecommunications, Rome, Italy, 2–5 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- GlobalTop Technology Inc. Gmm-u5j GPS Module Data Sheet. Available online: http://download.maritex.com.pl/pdfs/wi/GPSGMMU5J.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2019).

- Demiral, E.; Bayer, D. Further Studies on the COLREGs. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2015, 9, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarati, R.; Ziarati, M. Review of Accidents with Special References to Vessels with Automated Systems—A Way Forward. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.665.5802&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Batalden, B.; Sydnes, A. What causes ‘very serious’ maritime accidents? In Safety and Reliability—Theory and Applications; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2017; pp. 3067–3074. [Google Scholar]

- Karvonen, H.; Martio, J. Human Factors Issues in Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship Systems Development. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships, Busan, Korea, 8–9 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzykowki, Z.; Uriasz, J. The Ship Domain—A Criterion of Navigational Safety Assessment in an Open Sea Area. J. Navig. 2009, 62, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgosz, M. Ship Domain in Open Sea Areas and Restricted Waters. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2017, 11, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Cagle, L.; Reza, T.; Ball, J.; Gafford, J. LiDAR and Camera Detection Fusion in a Real Time Industrial Multi-Sensor Collision Avoidance System. Electronics 2018, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, W.; Irwin, G.; Yang, A. COLREGs-based collision avoidance strategies for unmanned surface vehicles. Mechatronics 2012, 22, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Nieh, C.Y.; Kuo, H.C.; Huang, J.C. An automatic collision avoidance and route generating algorithm for ships based on field model. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2019, 27, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, S.; Okada, N. Development of automatic collision avoidance system and quantitative evaluation of the maneuvering results. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2019, 13, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Okada, N.; Kuwahara, S.; Kutsuna, K.; Nakashima, T.; Ando, H. Study on Automatic Collision Avoidance System and Method for Evaluating Collision Avoidance Maneuvering Results. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1357, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porathe, T. Interaction between Manned and Autonomous Ships: Automation Transparency. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships, Busan, Korea, 8–9 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S.; Naeem, W.; Irwin, G. A review on improving the autonomy of unmanned surface vehicles through intelligent collision avoidance maneuvers. Annu. Rev. Control 2012, 36, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government Supporting E-LORAN. Available online: https://www.maritimejournal.com/news101/onboard-systems/navigation-and-communication/uk-government-supporting-e-loran (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- eLoran Standards Published—SAE. Available online: https://rntfnd.org/2018/09/21/eloran-standards-published-sae/ (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- South Korea Relaunches Its eLoran Program. Available online: https://insidegnss.com/south-korea-relaunches-its-eloran-program/ (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- R-Mode Baltic. Available online: https://www.dlr.de/kn/en/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-4308/6940_read-52591/ (accessed on 4 December 2019).

- Ziebold, R.; Medina, D.; Romanovas, M.; Lass, C.; Gewies, S. Performance Characterization of GNSS/IMU/DVL Integration under Real Maritime Jamming Conditions. Sensors 2018, 18, 2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felski, A. Methods of Improving the Jamming Resistance of GNSS Receiver. Annu. Navig. 2016, 23, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First Test Area for Autonomous Ships Opened in Finland. Available online: https://worldmaritimenews.com/archives/227275/first-test-area-for-autonomous-ships-opened-in-finland/ (accessed on 11 July 2019).

- First Unmanned Vessel Joins UK Ship Register. Available online: https://worldmaritimenews.com/archives/235207/first-unmanned-vessel-joins-uk-ship-register/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- The Strait of Dover—The Busiest Shipping Route in the World. Available online: https://www.marineinsight.com/marine-navigation/the-strait-of-dover-the-busiest-shipping-route-in-the-world/ (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- SEA-KIT Docks in Belgium to Complete First ever International Commercial Uncrewed Transit. Available online: http://www.sea-kit.com/sea-kit-docks-in-belgium-to-complete-first-ever-international-commercial-uncrewed-transit/ (accessed on 10 July 2019).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).