Abstract

To address the limitations of conventional eddy current magnetic-field-measurement techniques, this study proposes a novel measurement method for non-magnetic metals. First, the time-varying current in the Earth Field Simulator is calibrated using background magnetic sensors to obtain the coil magnetic field. This approach avoids repetitive errors caused by multiple current injections into the coil and ensures the simultaneity of current and magnetic field measurements. Additionally, the background eddy current magnetic field is approximated as a first-order RL-equivalent circuit, enabling the calculation and elimination of the background interference to improve the measurement accuracy of eddy current magnetic fields in non-magnetic metals. Next, experiments are carried out to measure the eddy current magnetic field of the non-magnetic metal plates under both ramp and sinusoidal magnetic field excitations. Finally, the eddy current magnetic simulations of the non-magnetic metal plates are conducted based on the finite element method. Under various excitation conditions, the maximum relative deviation between simulated and measured values remains below 5%, demonstrating the high precision of the proposed measurement method. This research provides a new approach for eddy current magnetic field measurement in non-magnetic metals.

1. Introduction

The ship’s magnetic field is a significant component of the physical field in the surrounding space. Based on its generation mechanisms, it can be classified into induced, permanent, eddy current, and other stray magnetic fields [1,2,3]. Among these, the permanent and induced magnetic fields generally dominate the overall magnetic signature of a vessel. Currently, considerable research progress has been made in the measurement methodologies for these two components [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, for certain low-magnetic-signature ships, such as minehunters and minesweepers, the eddy current magnetic field becomes the predominant magnetic source. Therefore, a thorough investigation of the eddy current magnetic field is of considerable theoretical importance for subsequent applications, including ship degaussing and shipborne geomagnetic field measurements [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

The generation mechanism of a ship’s eddy current magnetic field is described as follows: during navigation, the ship undergoes rotational motions such as rolling, pitching, and yawing, which cause changes in the magnetic flux passing through the vessel. This induces an electromotive force in the conductive hull, thereby generating eddy currents that excite the eddy current magnetic field [18,19]. The detection methods for a ship’s eddy current magnetic field are generally classified into a mechanical swing measurement and magnetic variation simulation. Early research on eddy current magnetic fields relied primarily on mechanical swing methods. For instance, British researchers induced swaying motion in ships through manual movement, a method that required significant human and material resources while offering limited measurement accuracy [20]. In 1994, following facility expansion, the Yokosuka Deperming Station in Japan pioneered the systematic investigation of ship eddy current magnetic fields using the magnetic variation simulation method [21]. This approach equates the eddy current magnetic field generated by conductor motion to that induced by a spatially varying magnetic field with a specific pattern. The introduction of this approach significantly improved experimental controllability and measurement efficiency. In the early 21st century, J.J. Holmes conducted theoretical derivations and numerical simulations of the eddy current magnetic field for finite-length thin cylindrical shell models based on the magnetic-variation-simulation method. His research contributed to establishing magnetic variation simulation as the mainstream approach in international academic studies on eddy current magnetic fields [22,23]. In 2015, H.-J. Chung et al. positioned a vessel within the German Earth Field Simulator (EFS), and by controlling the current in each coil, they simulated desired ship attitudes [24,25]. They combined the magnetic-variation-simulation method with the finite element method (FEM) to estimate the ship’s magnetic signature generated by eddy current effects. During the RIMPASSE trials, the CFAV Quest was positioned inside the EFS to simulate its rolling and pitching motions. The influence of eddy current magnetic signals induced by these different motions was measured via sensors installed beneath the ship. This provides preliminary validation that the EFS could be effectively applied to simulate the vessel’s eddy current effects under various operational scenarios [26]. Subsequently, Birsan M et al. developed a finite element model for predicting the eddy current magnetic field of the magnetic ship CFAV Quest [27]. Their simulation results demonstrated good agreement with full-scale experimental data, thereby verifying the model’s reliability in forecasting the distribution of the eddy current magnetic field around the vessel. In 2018, Polanski et al. analyzed simulation results and measurement data obtained from both scaled and full-scale models fabricated from low-magnetic steel [18]. Their work provided a broad characterization of the impact of eddy current magnetic fields, generated by rolling and pitching motions, on the overall magnetic signature of ships under low-frequency conditions. Wen Haodong et al. [28] conducted preliminary experiments within a laboratory-constructed zero-magnetic environment. They applied currents to the EFS to generate varying coil magnetic fields and then compared field measurements with and without an aluminum plate under identical excitation to extract the eddy current magnetic field of the aluminum plate. However, extracting the eddy current magnetic field requires first obtaining the simulation results of the eddy current magnetic field in the aluminum plate and using these simulation results to determine the starting point of the eddy current waveform, which lacks practical engineering value.

All the methods mentioned above derive the eddy current magnetic field by calculating the difference between magnetic field measurements inside the EFS with and without the object present, under identical excitation conditions. However, this approach demands high repeatability of the excitation current and encounters challenges in ensuring precise synchronization of magnetic field data acquisition before and after the object is positioned for measurement.

Accordingly, this paper proposes a novel measurement method for the eddy current magnetic field. Due to the complex structure of ships, it is difficult to obtain the eddy current magnetic field through simulation, making it hard to verify the accuracy of eddy current magnetic-field-measurement methods. Therefore, this paper selects simple non-magnetic metal plates as research objects to study the eddy current magnetic-field-measurement methods. Finally, the FEM is employed to numerically compute the eddy current magnetic field of the non-magnetic metal plates. A comparison with measured curves verifies the feasibility and accuracy of the proposed measurement method. The innovation of this paper lies in the following:

- (1)

- Placing a background magnetic sensor at a considerable distance from the experimental platform. The variation in the measurements of this sensor can be considered as generated solely by the coil magnetic field. Since the coil magnetic field is proportional to the current passing through it, once the proportional relationship between the two is established, the current can be calibrated based on the changes in the magnetic field measured by this sensor, thereby avoiding random errors caused by the insufficient repeatability of multiple power-on cycles.

- (2)

- Considering that the laboratory environment is not an ideal non-conductive space (e.g., presence of aluminum alloy track, metal equipment, etc.), these structures can generate background eddy current magnetic fields that affect the measurement accuracy. The background eddy current magnetic field can be approximated as a first-order RL-equivalent circuit, and it can be calculated and filtered using its time-domain characteristic parameters and the calibrated current values, thereby improving the measurement accuracy of the eddy current magnetic field of the metal plate.

2. Eddy Current Magnetic-Field-Measurement Method for Non-Magnetic Metals

Compared to the induced magnetic field and the permanent magnetic field, the eddy current magnetic field exhibits a relatively smaller magnitude. Therefore, this study selects non-magnetic metals as the research subject to avoid interference from the aforementioned magnetic fields. The generation of the eddy current magnetic field is attributed to variations in external magnetic excitation, which involves complex time-varying characteristics. In a laboratory, time-varying currents are applied to EFS to replicate varying external magnetic excitations, thereby inducing eddy currents within the conductor and subsequently generating the eddy current magnetic field.

When a time-varying current is applied to the EFS, the change in the magnetic field measured by the sensor includes both the coil magnetic field and the eddy current magnetic field. Moreover, due to the absence of an ideal non-conductive space in the laboratory environment (e.g., presence of aluminum alloy track, metal equipment, etc.), a certain background eddy current magnetic field is generated when the ambient magnetic field varies. Therefore, the total eddy current magnetic field comprises both the background eddy current magnetic field and the eddy current magnetic field induced in the non-magnetic metal. It is evident that the coil magnetic field and the background eddy current field must first be filtered out from the sensor measurements. Only then can the eddy current magnetic field generated in the non-magnetic metal by coil excitation be accurately isolated.

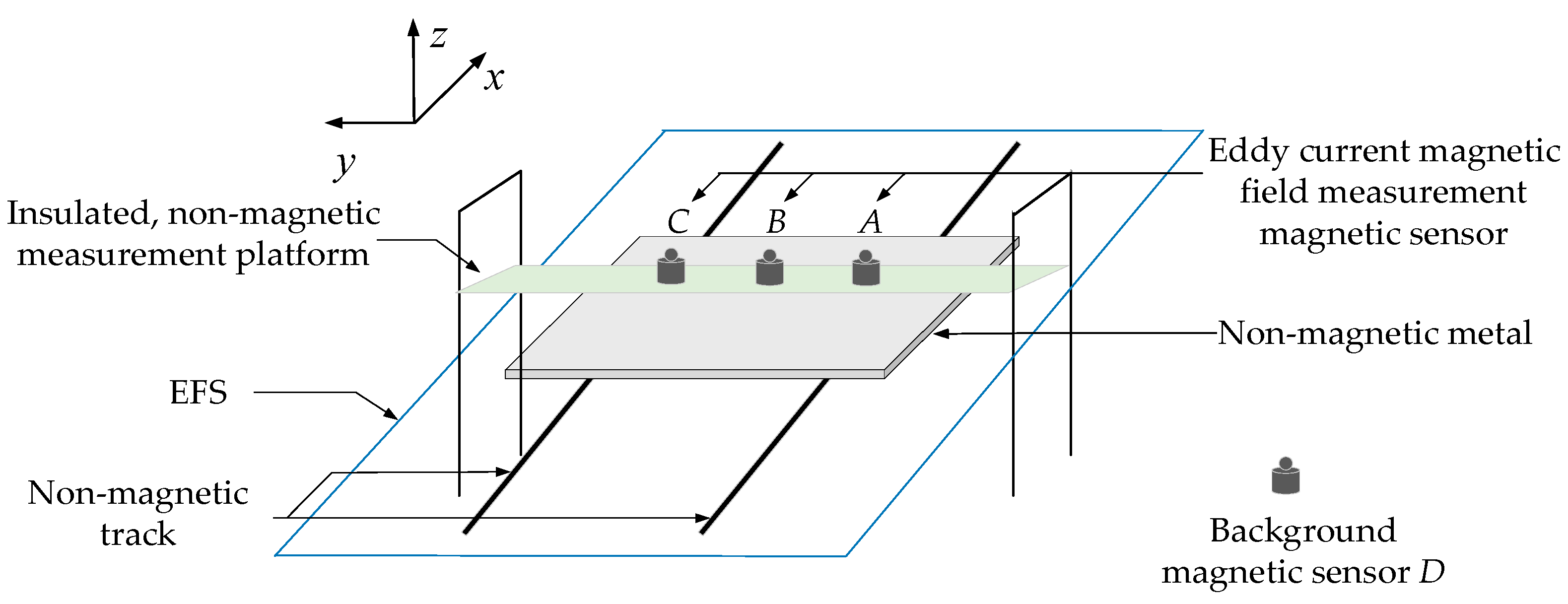

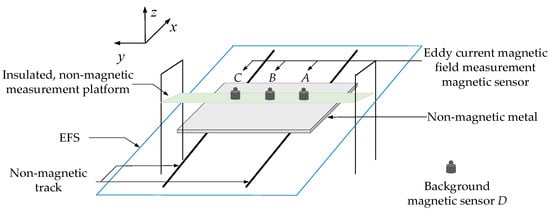

To address the aforementioned issues, a novel measurement method for the eddy current magnetic field in non-magnetic metals is proposed. A background magnetic sensor is used to monitor the coil current of EFS, thereby filtering out the coil magnetic field at the position of the eddy current magnetic field measurement magnetic sensors. A mathematical model of the background eddy current magnetic field is established using the equivalent circuit principle. Then, based on the calibrated coil current, the background eddy current magnetic field can be determined. By filtering out these two interference magnetic fields, the eddy current magnetic field of the non-magnetic metal can be obtained. The proposed experimental platform is shown in Figure 1, with the x, y, and z coordinate axes as indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental platform.

2.1. Acquisition of the Coil Magnetic Field

According to the Biot-Savart Law, the variation in the coil magnetic field is governed by the current flowing through the EFS, as expressed by the following proportionality:

where Bcoil(t) denotes the coil magnetic field after energizing the coils, with units of nT; i(t) represents the time-varying current supplied to the EFS, with units of amperes (A); the coil magnetic coefficient kcoil, with units of nT/A, indicates the change in the coil magnetic field per unit current applied to the EFS. Consequently, the coil magnetic field can be determined if the coil magnetic coefficient kcoil is determined and the time-varying current i(t) is monitored. The specific procedure is as follows:

- (1)

- An experimental platform is set up within the EFS. Place a background magnetic sensor D at a location relatively far from the experimental platform, designated as Sensor 1. There is no interference from ferromagnetic materials and conductive materials around it, ensuring that the measured magnetic field changes are solely due to coil excitations. A constant current is applied to the coils, and the variation in the magnetic field before and after energization, Bcoil1, is recorded via Sensor 1. At this stage, both Bcoil1(t) and i(t) remain constant. According to Equation (1), we have kcoil1 = Bcoil1/I, where I is a constant. This allows the calculation of the coil magnetic field coefficient kcoil1 at Sensor 1. From Equation (1), i(t) = Bcoil1(t)/kcoil1. Thus, the time-varying current i(t) supplied to the coils can be calibrated based on the magnetic field variation Bcoil1(t) measured by Sensor 1 and the coefficient kcoil1.

- (2)

- Place the eddy current magnetic field measurement magnetic sensor A, B, and C inside the experimental platform, designated as Sensor 2. Following the same procedure as in step 1, a constant current is applied to the coils, and the measured magnetic field variation is used to determine the coil magnetic field coefficient kcoil2 at Sensor 2. Combined with the time-varying current i(t) calibrated by Sensor 1 in step 1, the coil magnetic field measured at Sensor 2, Bcoil2, can be calculated according to Equation (1) and subsequently filtered out.

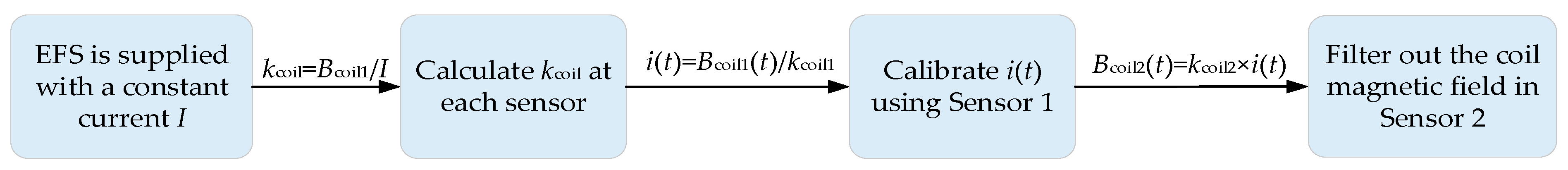

The process for obtaining the coil magnetic field is shown in the Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the acquisition of the coil magnetic field.

2.2. Acquisition of Background Eddy Current Magnetic Field

The eddy current magnetic field is a linear system, where the magnetic fields induced by excitations in different directions can be superimposed. Therefore, taking the coil magnetic field in the z-direction as an example, the dynamic mathematical model of the eddy current magnetic field Bed can be obtained as follows:

where Bedx(t), Bedy(t), and Bedz(t) represent the three components of the eddy current magnetic field, with units of nT; iedz(t) denotes the eddy current caused by the variation in time of the magnetic field in the z-direction, with units of A. The parameters k11, k21, and k31 are defined as the eddy current proportionality coefficients in the x, y, and z directions, respectively, with units of nT/A. These coefficients quantify the three components of the eddy current magnetic field generated per unit eddy current at the sensor location due to variations in the coil magnetic field. Therefore, by determining the eddy current proportionality coefficients and the background eddy current, the background eddy current magnetic field can be derived.

- (1)

- Equivalent process of eddy currents

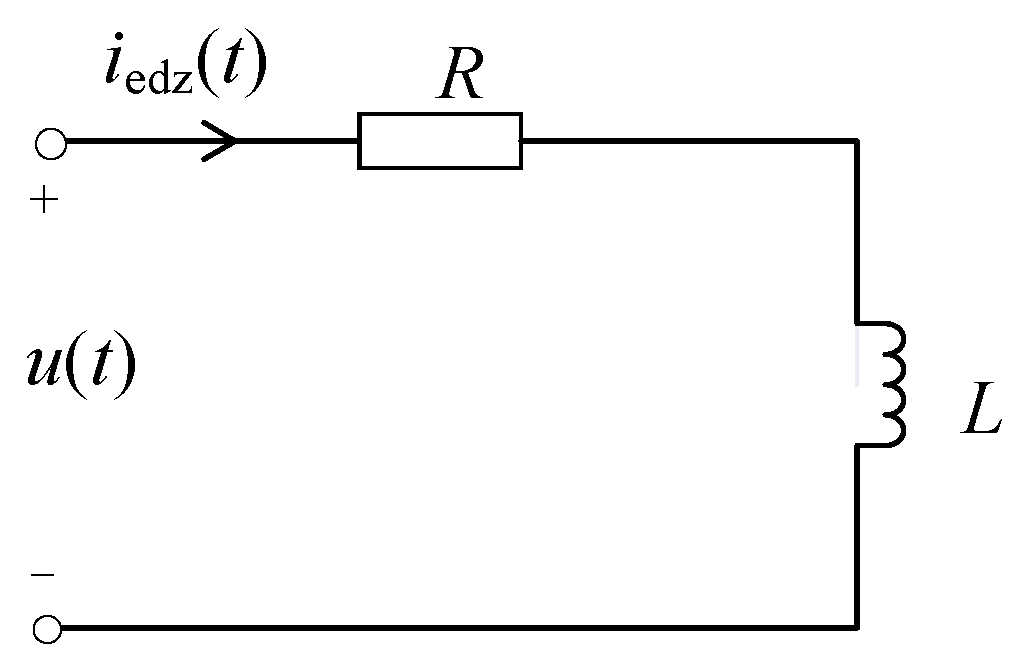

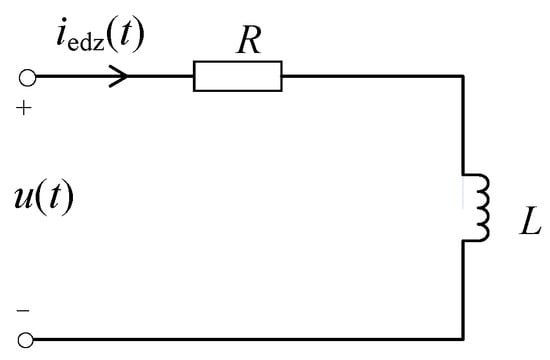

The eddy current can be equivalently modeled as a multi-order RL dynamic circuit. Consequently, the time-varying characteristics of the eddy current magnetic field can be represented by the output behavior of the RL dynamic circuit. Analysis indicates that the background eddy current model is relatively simple and can be approximated as a first-order RL circuit. The equivalent circuit is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the RL equivalent circuit corresponding to background eddy currents.

Here, u(t) represents the terminal voltage in volts; R and L denote the equivalent resistance and equivalent inductance in the circuit, with units of Ω and H, respectively. Taking the coil magnetic field excitation in the z-direction as an example, according to the Law of Electromagnetic Induction, the terminal voltage u(t) of the equivalent circuit satisfies the following:

where Bcoilz(t) represents the coil magnetic field in the z-direction, with units of nT; α denotes the terminal voltage coefficient, representing the induced electromotive force generated by unit rate of change of the coil magnetic field, with units of V/(nT/s).

The eddy current iedz(t) induced in the equivalent circuit is discretized and segmented into multiple time intervals of Δt for analysis. When Δt is sufficiently small, the rate of change of the magnetic field can be considered constant. According to the full response formula for first-order RL circuits, the following expression is obtained:

where iedz(t0) denotes the initial eddy current at time t0, with units of amperes (A). The time constant is defined as τ = L/R, in seconds (s), which characterizes the duration of the eddy current transient process. Assuming that the initial eddy current is known, the eddy current after a time interval Δt depends solely on the time constant τ and the rate of change of the coil magnetic field. As established in Section 2.1, the coil magnetic field is proportional to the time-varying current supplied to the coils, thus

Combining Equations (4) and (5) and multiplying both sides by the eddy current proportionality coefficients k11, k21, and k31, we obtain the following:

where the eddy current amplitude coefficients k1, k2, and k3 (units: s) are given by the product of kcoil2, α/R, and the eddy current proportionality coefficients k11, k21, and k31, respectively.

- (2)

- Identification of eddy current amplitude coefficient

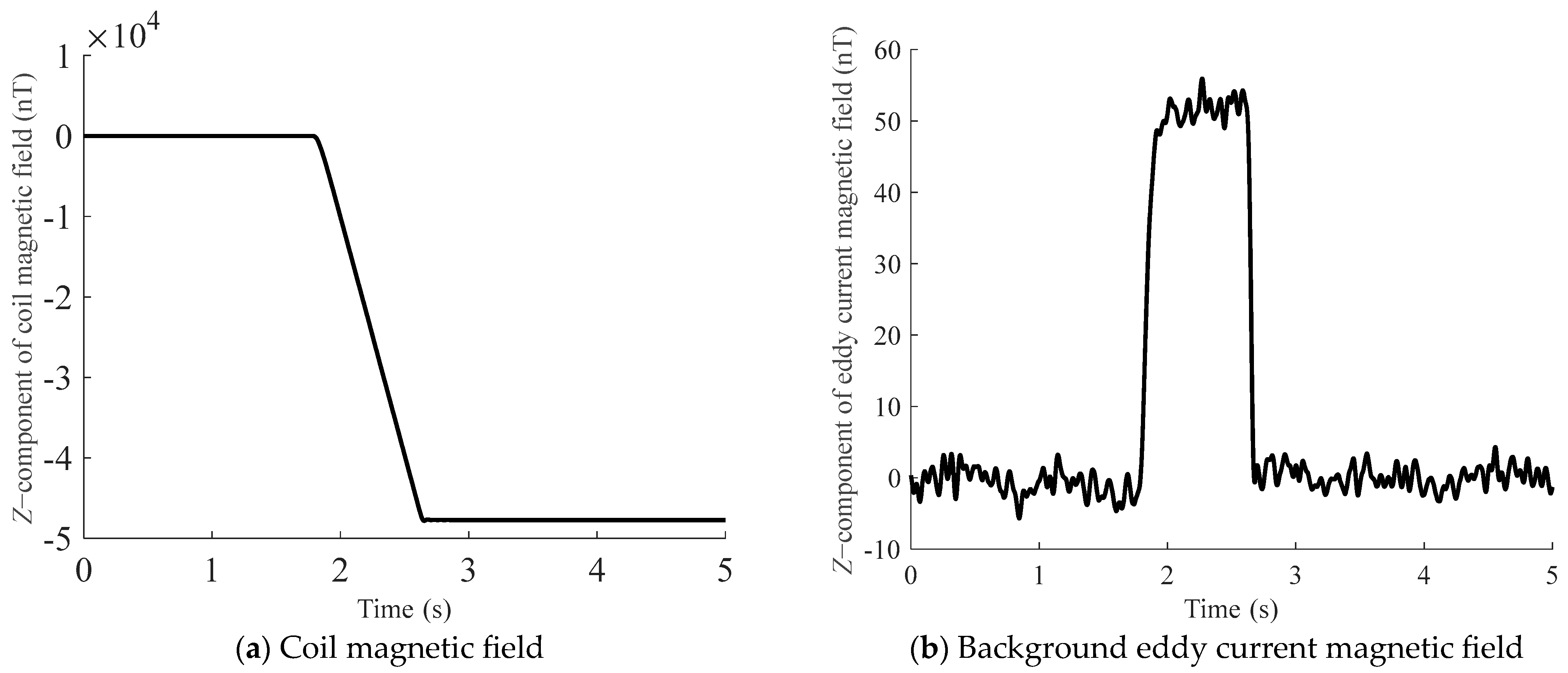

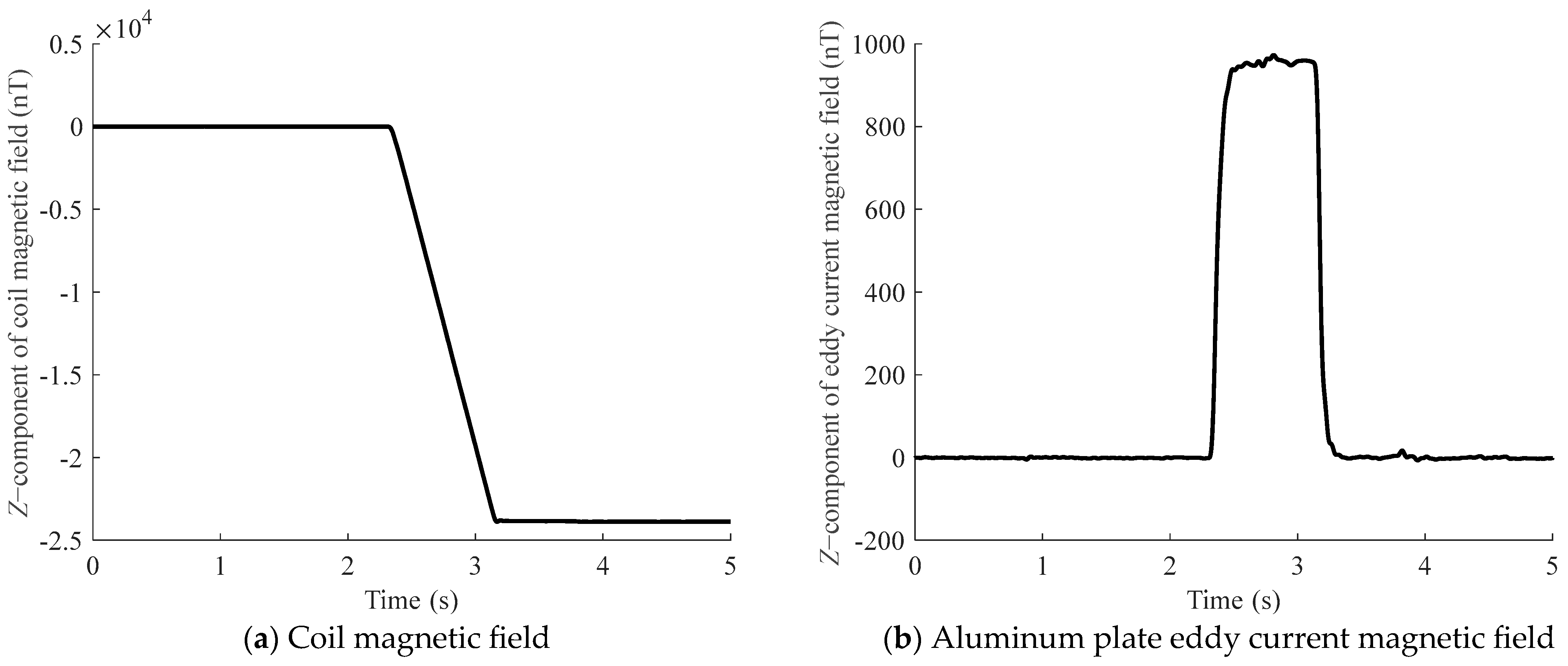

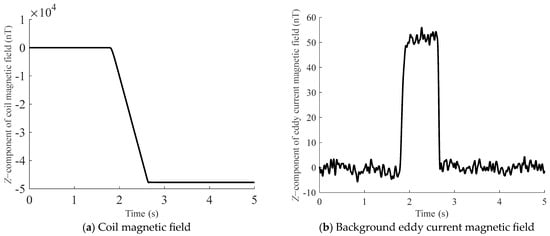

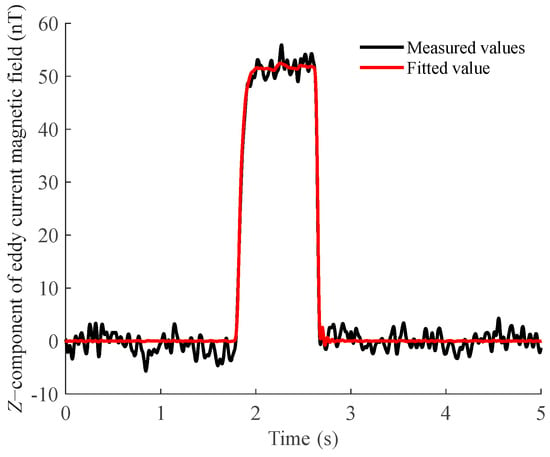

Prior to the placement of the non-magnetic metal, a ramp current with a constant slope is applied to the EFS. Following the method described in Section 2.1, the instantaneous value of the ramp current is determined based on the measurements from Sensor 1 and the coil magnetic field coefficient kcoil1. Subsequently, the coil magnetic field is removed from the variation in the measurements of Sensor 2 by using the coil magnetic field coefficient kcoil2 and the mentioned ramp current, thereby obtaining the background eddy current magnetic field Bed. The result is shown in Figure 4 (taking the z-component of the eddy current magnetic field as an example).

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the z-component of the coil magnetic field and the background eddy current magnetic field. Among them, (a) represents the z-component of the coil magnetic field, and (b) represents the z-component of the background eddy current magnetic field under the excitation of the coil magnetic field.

An analysis of Figure 4 indicates that the eddy current magnetic field reaches a near-constant plateau upon attaining its maximum value. This phenomenon arises because a ramp-function coil excitation, characterized by a constant slope, produces an unchanging rate of magnetic flux variation through the conductor’s cross-section. This, in turn, leads to a stabilized induced electromotive force, resulting in a constant eddy current magnetic field. According to Equation (6), when , the eddy current magnetic field reaches this steady state, given by the following:

First, take the average value of the background eddy current magnetic field under steady-state conditions. Then, calibrate the time-varying current in the coil using the method described in Section 2.1. Finally, divide the average value of the background eddy current magnetic field by the rate of change of the coil current to obtain the eddy current amplitude coefficients k1, k2, and k3.

- (3)

- Identification of the time constant

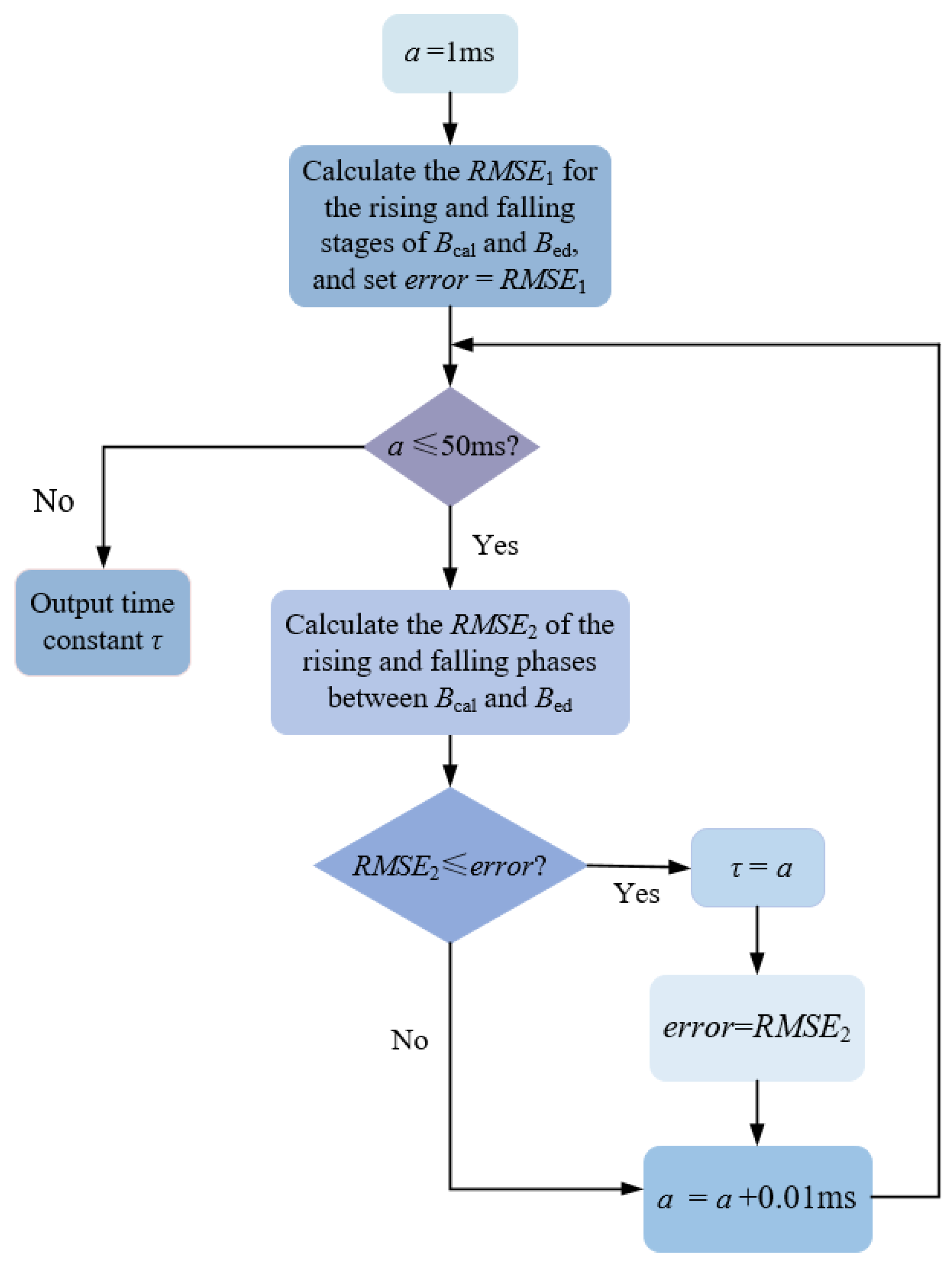

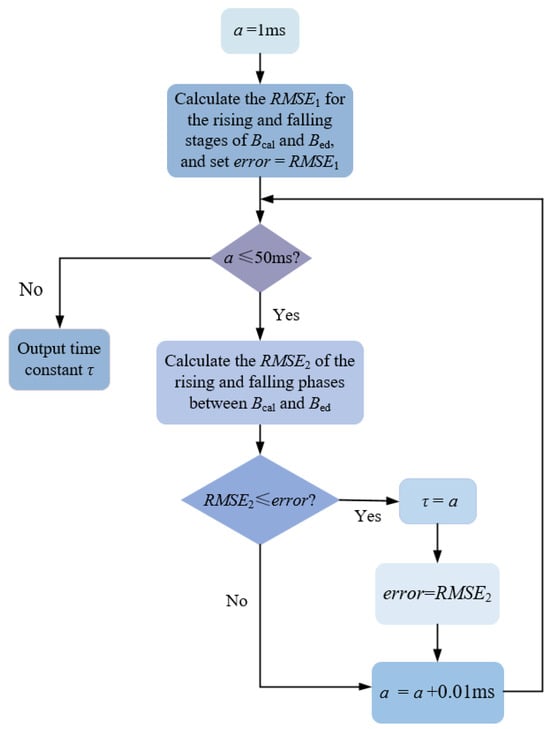

As indicated by Equation (6), the time constant τ remains the only unknown in the eddy current ied(t). An iterative optimization method is employed to determine τ. Specifically, τ is iterated over the interval [1, 50] ms with a step size of 0.01 ms. For each value, the corresponding background eddy current magnetic field Bcal is calculated by substituting into Equation (6) in conjunction with the time-varying current i(t) and the eddy current amplitude coefficient. This computed result Bcal is then compared against the measured background eddy current magnetic field Bed.

Figure 4 reveals that the variation in Bed is primarily characterized by rising and falling segments. These specific segments from both Bcal and Bed are selected for comparison. The optimal value of τ is identified when the root mean square error (RMSE) between them is minimized. The specific operating procedure is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of time constant τ identification.

Through this process, the time-domain characteristic parameters of the background eddy current magnetic field are successfully identified. Consequently, when the coil excitation is an arbitrary waveform, the background eddy current magnetic field Bed(t) at any time instant can be derived from Equation (6), following the calibration of the coil current i(t) using Sensor 1.

According to the aforementioned analysis, the magnetic measurement value of Sensor 2 minus the coil magnetic field and the background eddy current magnetic field can obtain the eddy current magnetic field of the non-magnetic metal.

3. Eddy Current Magnetic Field Measurement of an Aluminum Plate

The method for obtaining the eddy current magnetic field from non-magnetic metals has been described above. Based on this method, the eddy current magnetic field of the aluminum plate is measured in the laboratory. The eddy current magnetic field is inherently weak in magnitude and susceptible to interference from the significant diurnal variations in the geomagnetic field during daytime. To mitigate this, the experiments are scheduled during the early morning hours when geomagnetic activity is minimal and stable. This approach allows for the influence of geomagnetic fluctuations to be effectively neglected.

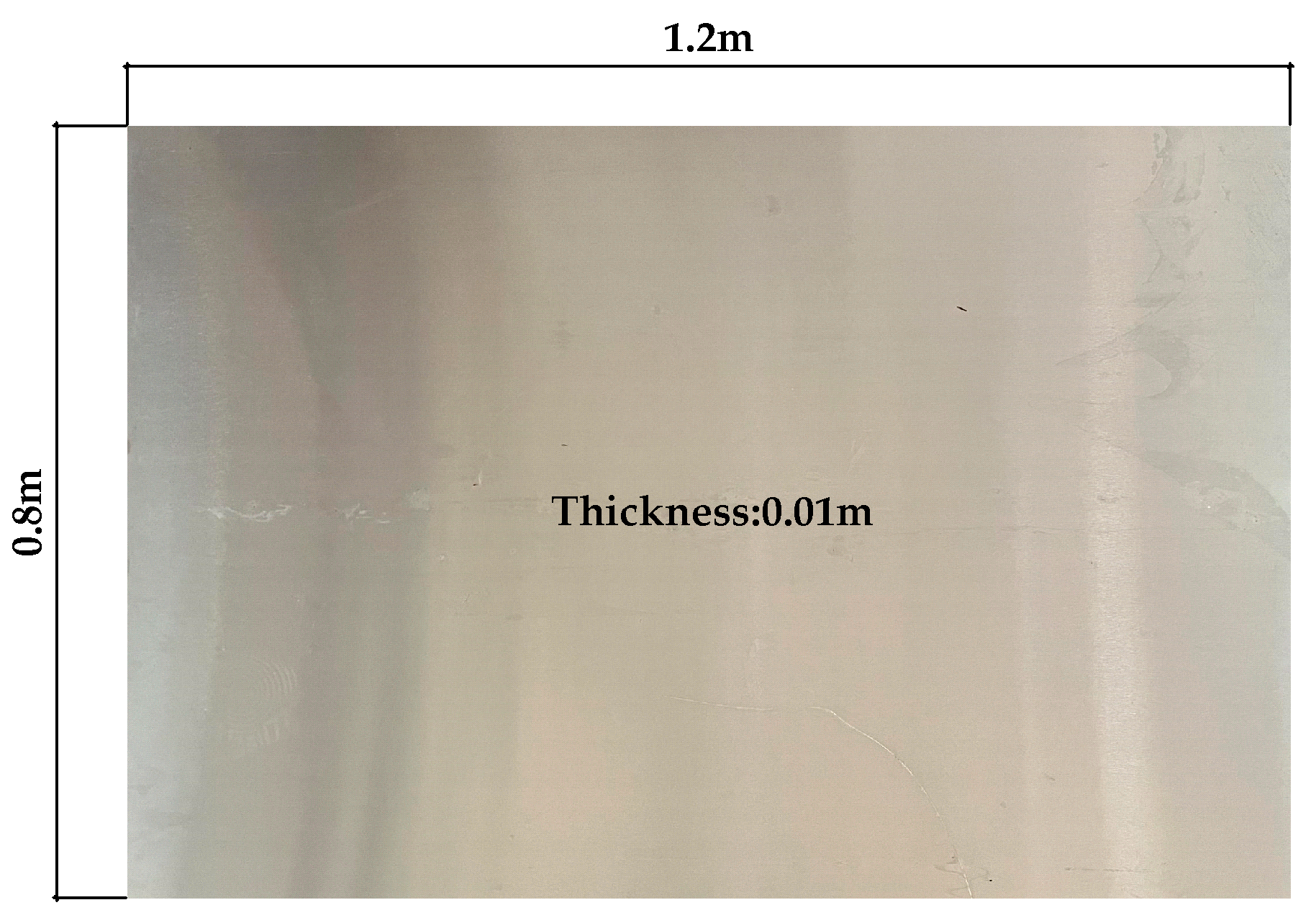

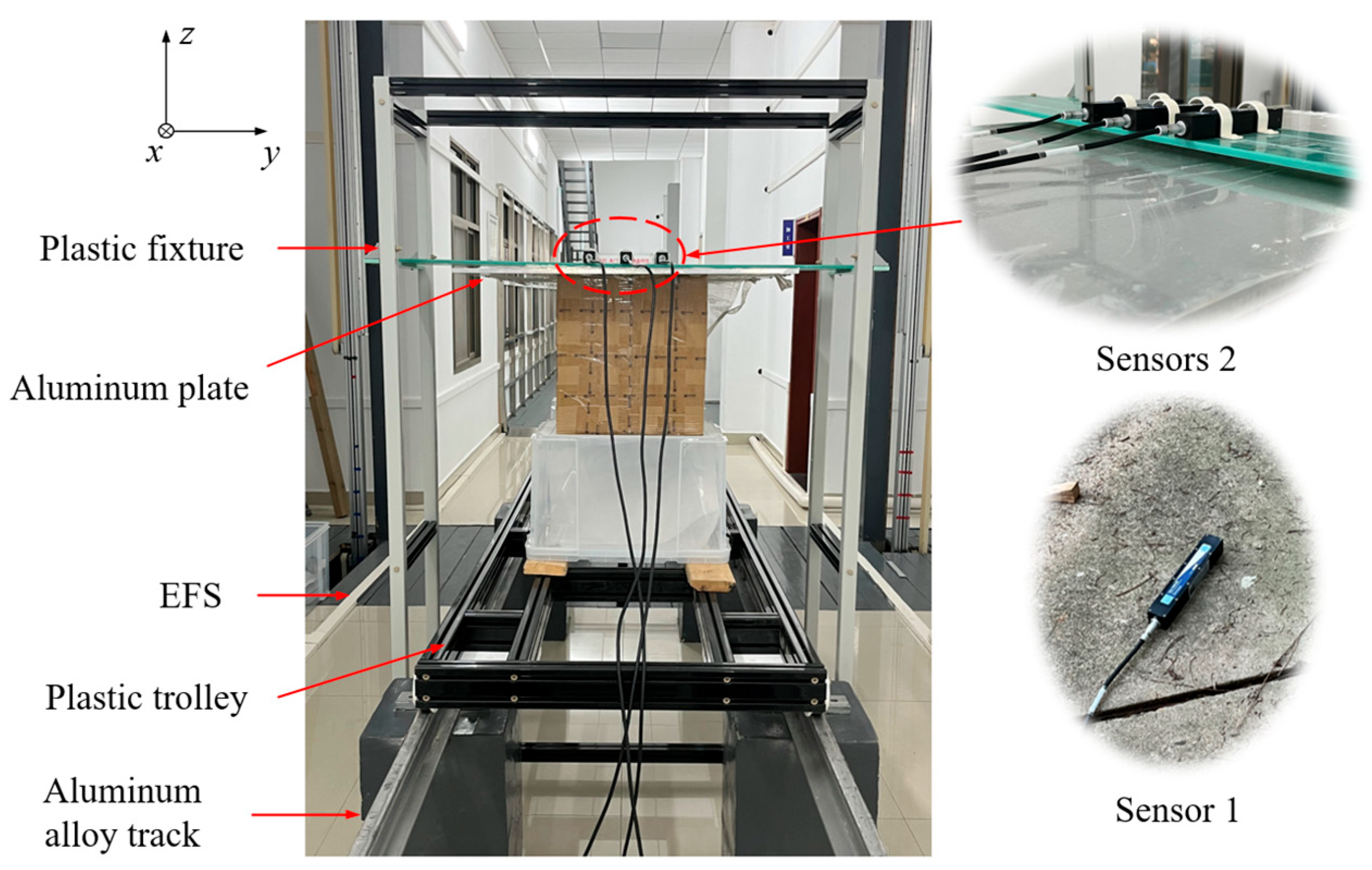

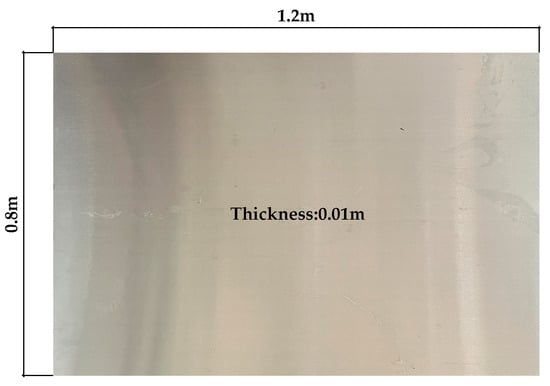

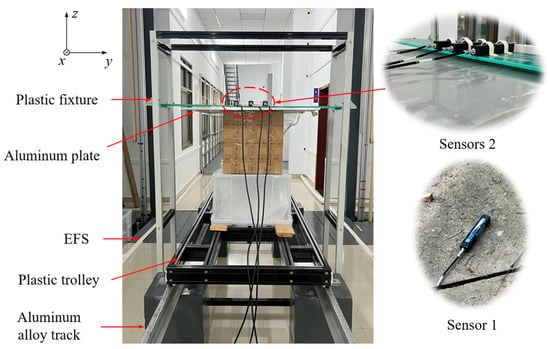

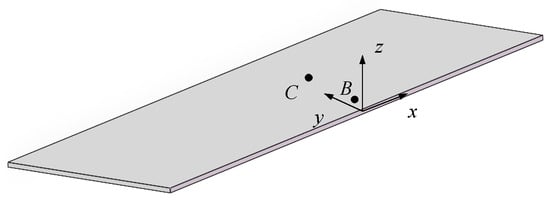

The experiment utilizes the laboratory’s existing EFS and an aluminum plate with dimensions 1.2 m × 0.8 m × 0.01 m, manufactured from 6061 aluminum alloy, as shown in Figure 6. A coordinate system is established with its origin at the center of the plate, and the x, y, and z directions are shown in Figure 7. Build a plastic fixture above the aluminum plate to hold the sensors. Three magnetic sensors, denoted A, B, and C, are positioned on this fixture, with their respective coordinates listed in Table 1. The functions of these three sensors are the same as those of Sensor 2 in Section 2.1, used to measure the eddy current magnetic field of the aluminum plate. The use of plastic profiles for the fixture prevented the introduction of additional eddy current magnetic interference. An additional sensor D is placed at a considerable distance from the experimental platform. Similar to Sensor 1 in Section 2.1, it is used to calibrate the coil current in areas where the influence of the eddy current magnetic field can be neglected. All sensors are MAG-13 three-axis magnetic field sensors from Bartington instruments.

Figure 6.

Photo of the aluminum plate.

Figure 7.

Experimental platform.

Table 1.

Coordinates of measurement points above the aluminum plate in the laboratory.

According to the magnetic-variation-simulation method, the eddy current magnetic field of the aluminum plate is generated by changes in the external magnetic field in the x, y, and z directions. However, due to the aluminum plate’s minimal thickness of 0.01 m, the eddy currents induced by excitations along the x-axis and y-axis are not significant. Therefore, this study focuses solely on the eddy current magnetic field generated by the aluminum plate under coil excitation along the z-axis. Consequently, only the EFS of the z-direction is employed in the experiment, where a vertical magnetic field with a uniformity of 99.63% can be generated in the aluminum plate space. The magnetic field uniformity H is defined as follows [29]:

where i is the index of a uniformly distributed point in the aluminum plate enclosure space (i = 1, 2, 3, …, n); bi is the vertical component of the magnetic field generated by the coil at the i-th point with the units of nT; ba is the average vertical magnetic field of all points with the units of nT.

The procedure for measuring the eddy current magnetic field of an aluminum plate using the proposed method is as follows:

- (1)

- With the aluminum plate absent from the EFS, a constant current of 20 A is applied to the coils. The resulting variations in the measured values from Sensors A, B, and C are denoted as ΔBbg1, while the variation from Sensor D is denoted as ΔBbg2. The coil magnetic field coefficients kcoil are then calculated according to the method described in Section 2.1, with the results presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Coil magnetic field coefficient kcoil at different sensor locations.

Table 2. Coil magnetic field coefficient kcoil at different sensor locations.

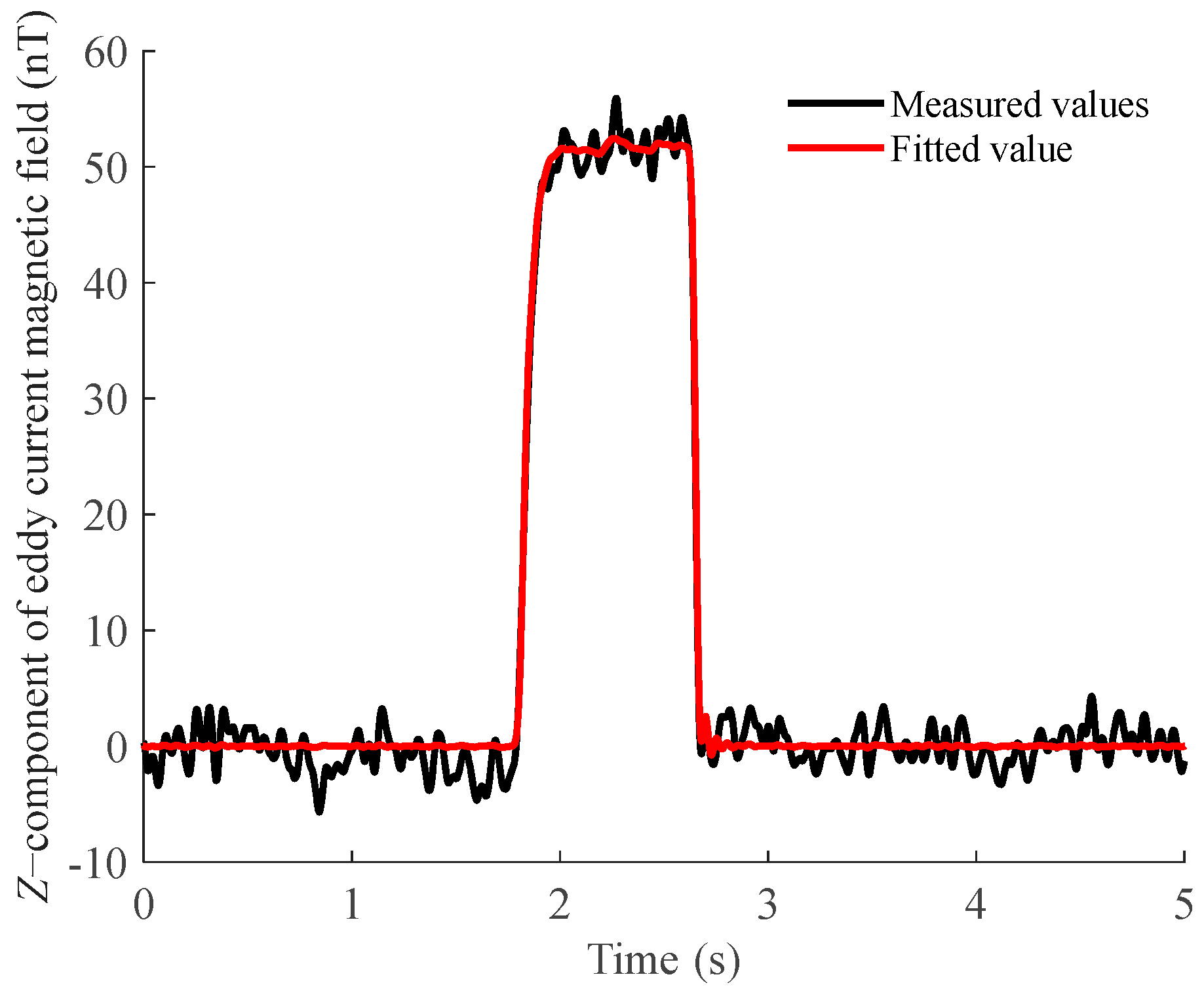

- (2)

- The sampling frequency of the magnetic sensors is set to 1000 Hz. A ramp current with a slope of 10 A/s and a maximum value of 10 A is applied to the EFS. The magnetic field variations of Sensors A, B, and C, denoted as ΔBramp1(t), are recorded relative to their pre-energized states, alongside the variation ΔBramp2(t) from Sensor D. First, according to the method described in Section 2.1, the ramp current is calibrated using ΔBramp2(t). Subsequently, the coil magnetic field component is removed from ΔBramp1(t) using the coil magnetic field coefficients provided in Table 2, thereby extracting the background eddy current magnetic field. Finally, the time-domain characteristic parameters of this background eddy current field are determined using the method proposed in Section 2.2; the results are presented in Table 3. The fitting curve used to solve for the time constant τ, as described in Section 2.2, is shown in Figure 8 (taking the z-component of the background eddy current magnetic field at sensor B as an example).

Table 3. Time-domain characteristic parameters of background eddy current magnetic fields at different sensors.

Table 3. Time-domain characteristic parameters of background eddy current magnetic fields at different sensors. Figure 8. Schematic diagram of the background eddy current magnetic field fitting results, where the black curve represents the measured values and the red curve represents the fitted values.

Figure 8. Schematic diagram of the background eddy current magnetic field fitting results, where the black curve represents the measured values and the red curve represents the fitted values.

- (3)

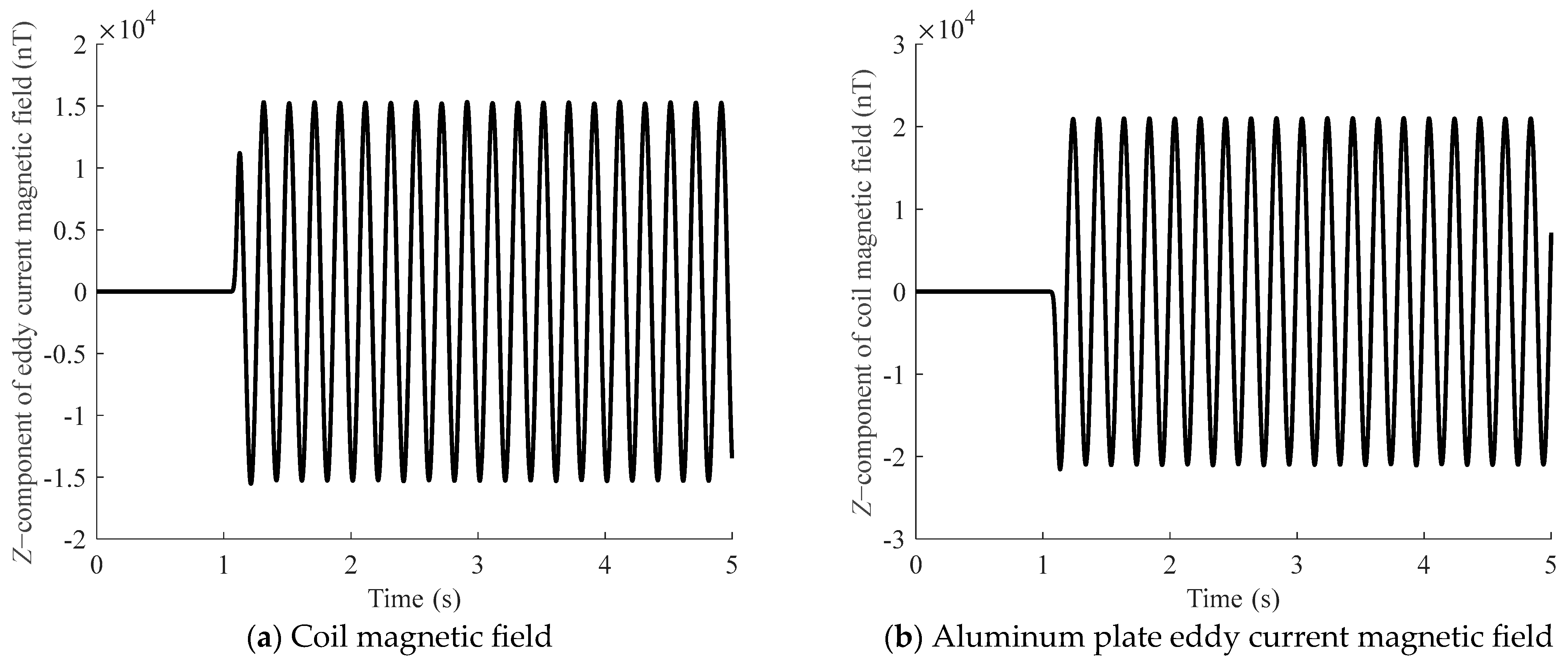

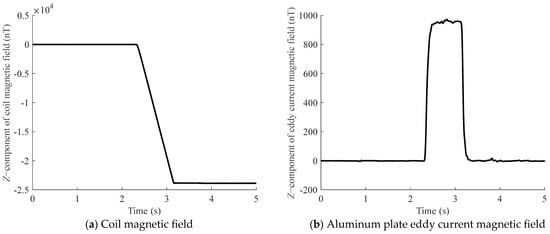

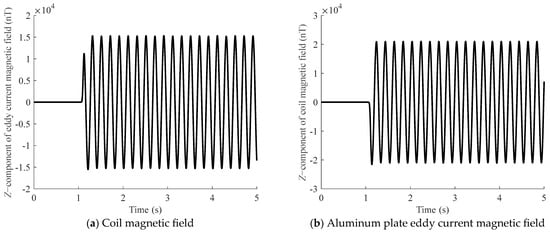

- The aluminum plate is placed inside the EFS. The following currents are applied to the coils in sequence: a ramp current with a slope of 10 A/s and a maximum value of 10 A; and sinusoidal currents with frequencies of 1 Hz, 2 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz, each with a peak value of 7.07 A. After each data-acquisition cycle, the magnetic field measurement variations from Sensors A, B, and C are recorded as ΔBmeas1, while the measurement variations from Sensor D are recorded as ΔBmeas2. The data-processing procedure is as follows. First, the current i(t) flowing in the coils was calibrated based on the variations measured by sensor D, enabling the removal of the coil magnetic field. Next, using the time-domain characteristic parameters of the background eddy current magnetic field at different sensor locations listed in Table 3, the background eddy current magnetic field is calculated according to the method described in Section 2.2. Finally, the background eddy current magnetic field is subtracted from the measured values to obtain the aluminum plate’s eddy current magnetic field, denoted as Bal(t). The resulting aluminum plate eddy current magnetic field and the corresponding coil magnetic field are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10 (using the z-component of the magnetic field at sensor B as an example; for sinusoidal excitation, only the results at 5 Hz are presented).

Figure 9. Schematic diagram of the z-component of the coil magnetic field and the eddy current magnetic field in the aluminum plate under a z-direction ramp magnetic field, where (a) is the coil magnetic field, and (b) is the eddy current magnetic field in the aluminum plate.

Figure 9. Schematic diagram of the z-component of the coil magnetic field and the eddy current magnetic field in the aluminum plate under a z-direction ramp magnetic field, where (a) is the coil magnetic field, and (b) is the eddy current magnetic field in the aluminum plate. Figure 10. Schematic diagram of the z-component of the eddy current magnetic field in an aluminum plate under a 5 Hz sinusoidal magnetic field in the z-direction with a coil magnetic field, where (a) is the sinusoidal coil magnetic field, and (b) is the eddy current magnetic field in the aluminum plate.

Figure 10. Schematic diagram of the z-component of the eddy current magnetic field in an aluminum plate under a 5 Hz sinusoidal magnetic field in the z-direction with a coil magnetic field, where (a) is the sinusoidal coil magnetic field, and (b) is the eddy current magnetic field in the aluminum plate.

4. Simulation of Eddy Current Magnetic Field

Based on the eddy current magnetic-field-measurement method described previously, this study conducts a series of experiments using an aluminum plate in a laboratory. By processing the signals from the sensors, the eddy current magnetic field data of the aluminum plate under different excitation conditions are successfully extracted. This section further employs the FEM to simulate and analyze the eddy current magnetic field in the aluminum plate. By comparing simulated values with measured values, the accuracy of the measurement method for the aluminum plate eddy current magnetic field is validated.

This research requires a standard reference solution to validate the accuracy of the proposed eddy current magnetic-field-measurement method. However, no analytical solution for the eddy current magnetic field of a rectangular plate exists in the existing literature. Consequently, simulated values of this magnetic field must be generated using the FEM. These simulated values will subsequently be compared with measured values to validate the accuracy of the method presented in this paper. In this process, the eddy current magnetic field simulation calculations based on the FEM are validated using a regular spherical model [30].

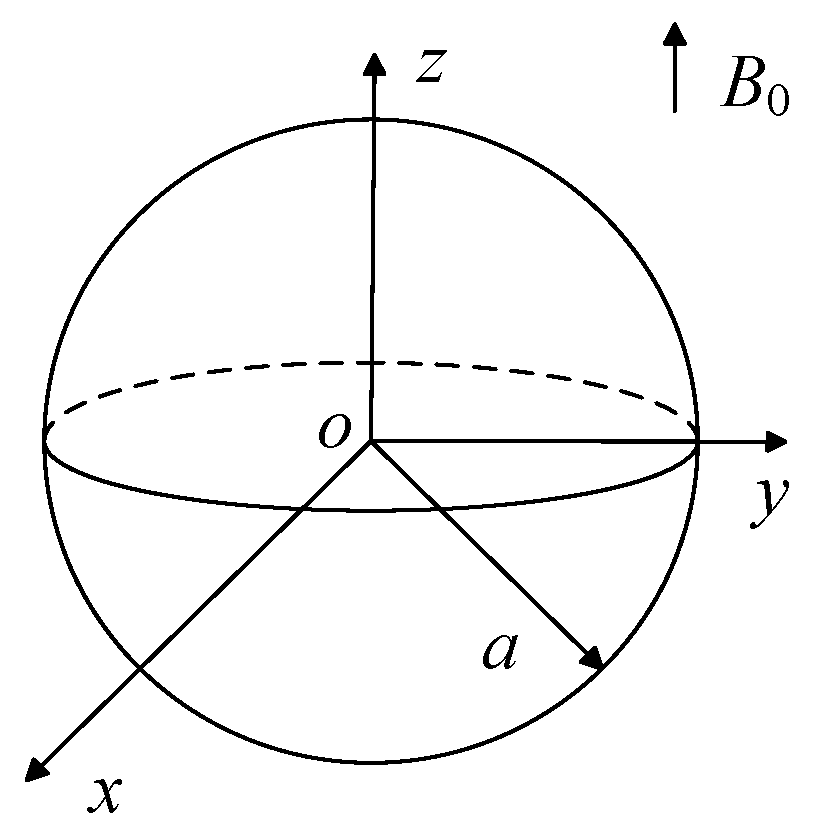

4.1. Analytical Solution of Spherical Eddy Current Magnetic Field

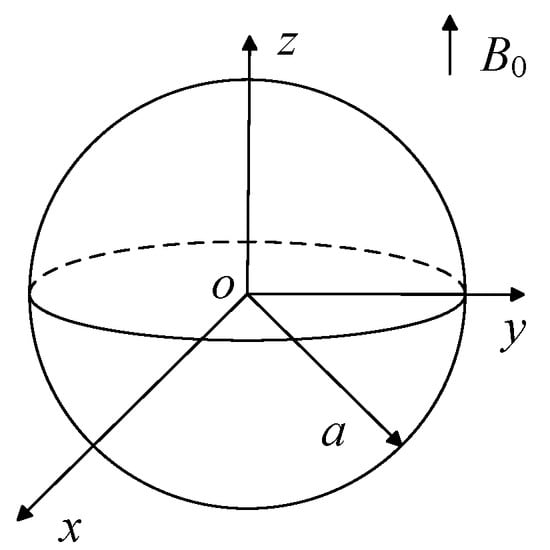

In the spherical Cartesian coordinate system shown in Figure 11, a conductive magnetic sphere with a radius of a is placed in an externally applied sinusoidal magnetic field, with the magnetic field strength being as follows:

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of conductive magnetic sphere.

The initial phase is 0, and the direction is along the positive z-axis.

The spherical material is a linear and homogeneous medium, with electrical conductivity σ and magnetic permeability µi (µi = µr1µ0, where µr1 is the relative magnetic permeability of the spherical material); the medium outside the sphere is air, with magnetic permeability µ0.

In the spherical coordinate system, let the magnetic vector potentials inside and outside the sphere be Ao and Ai, respectively. Using the method of separation of variables, the general solutions for the regional magnetic vector potentials Ao and Ai of the sphere can be obtained.

In the equation,

In + ½ is the half-integer order first-kind modified Bessel function, and the undetermined coefficient D is related to the magnetic vector potential function A, expressed as follows:

In the equation, α = va.

After obtaining the expression for the magnetic vector potential, the magnetic induction at each field point outside the sphere is solved, as shown in the following expression:

Substitute Equation (14) into Equation (15) and convert the three components of the magnetic induction intensity in the spherical coordinate system above to the rectangular coordinate system, expressed as follows:

This allows the calculation of the magnetic flux density at various points outside the sphere.

4.2. Finite Element Simulation of Magnetic Field Interference by Spherical Eddy Currents

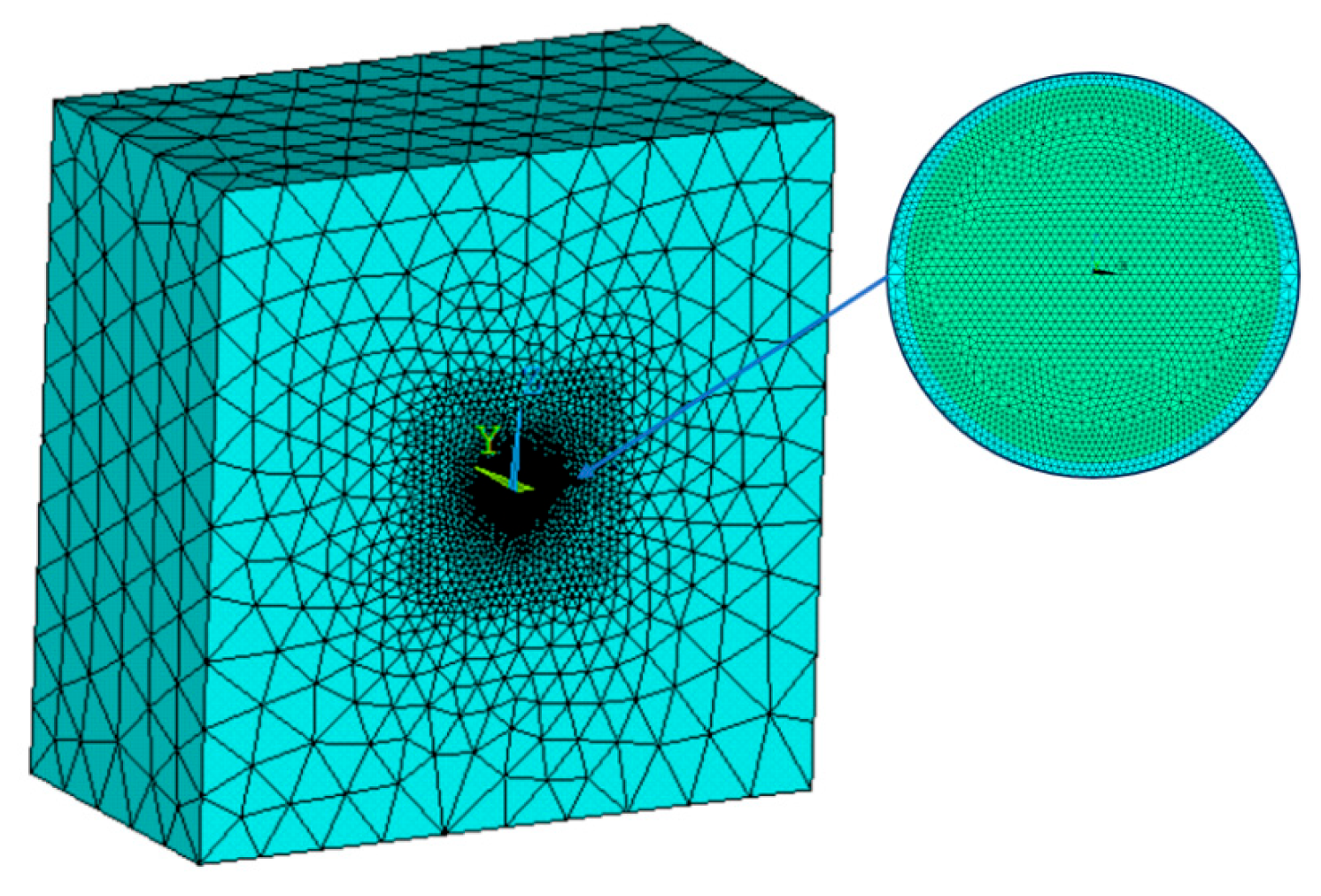

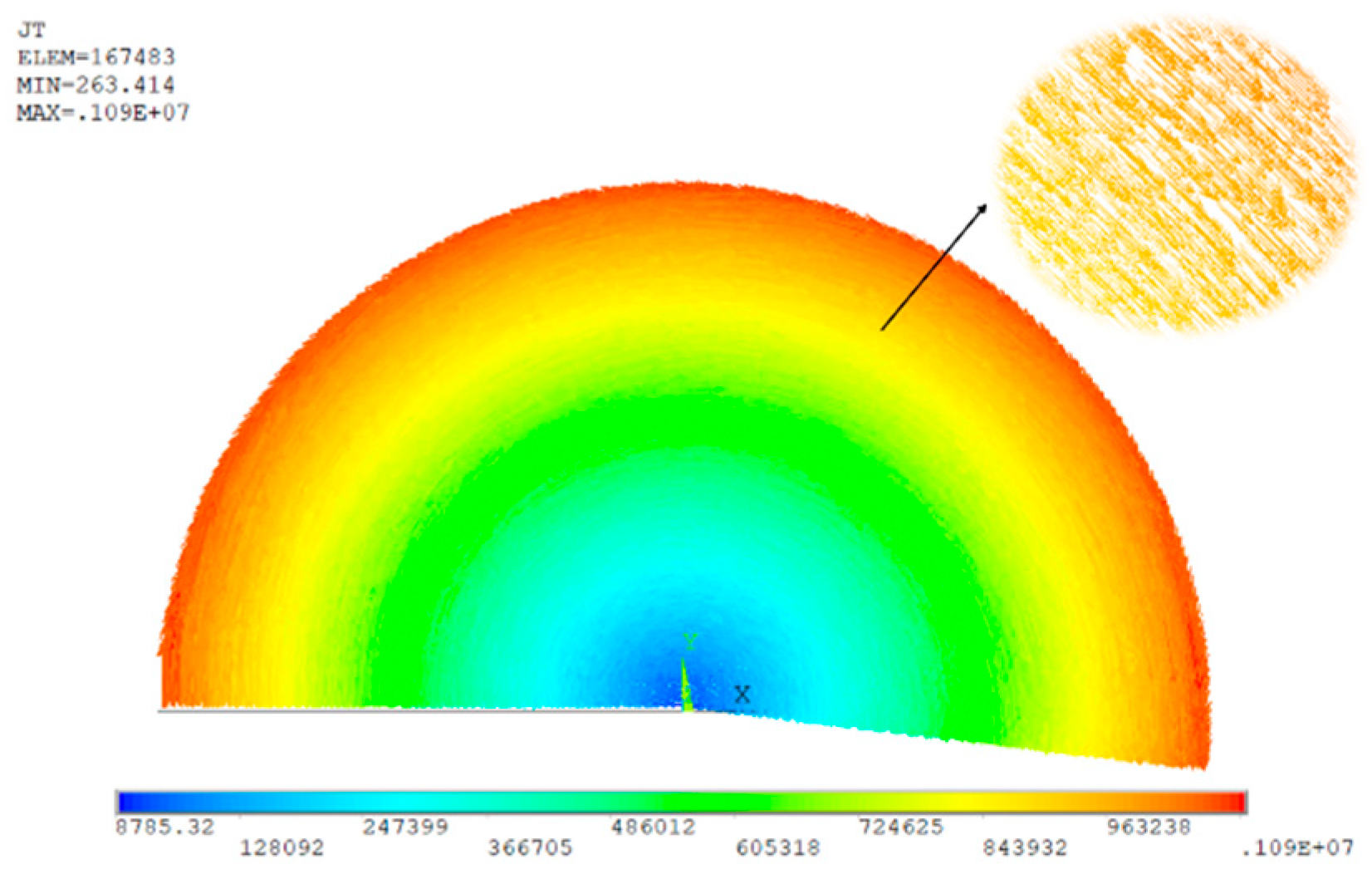

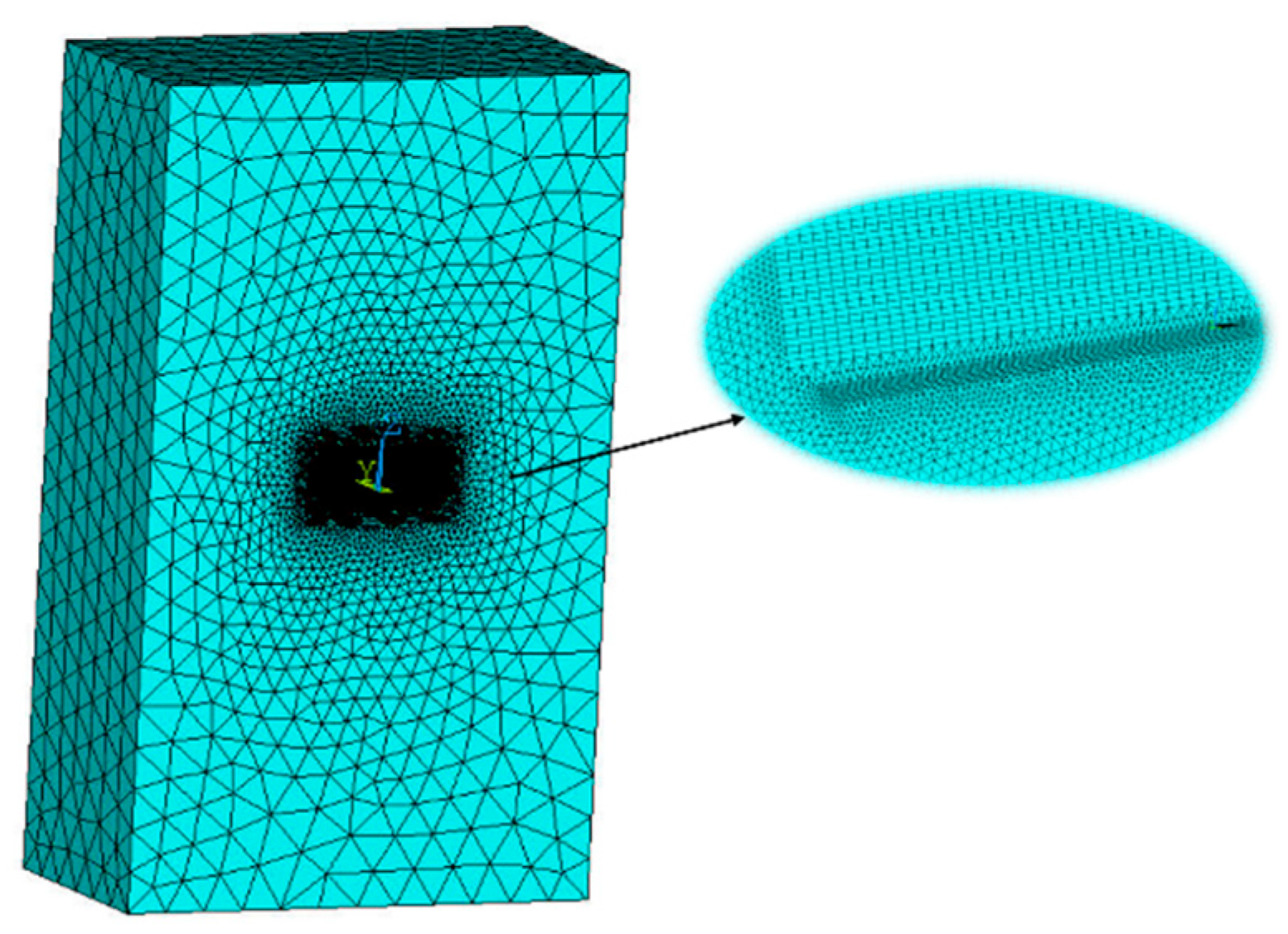

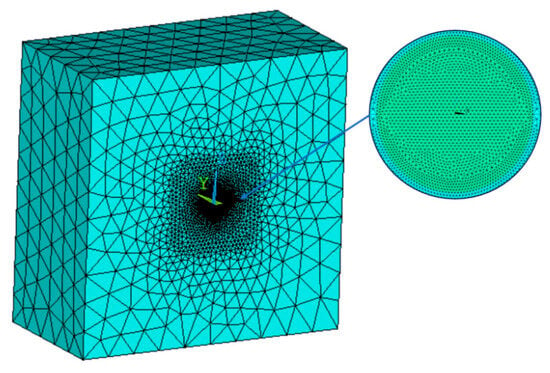

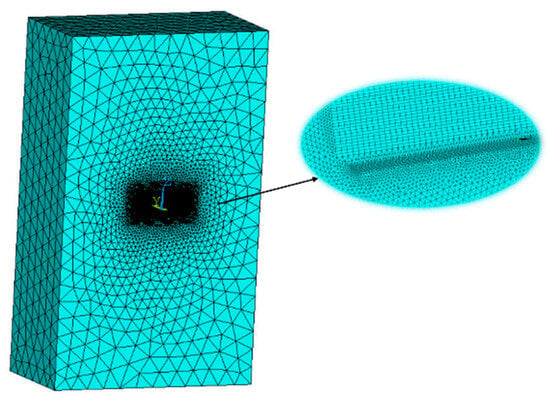

Build a spherical model with the sphere’s center as the origin, a radius a of 0.1 m, conductivity σ of 3.2 MS/m, and relative permeability of 1. Based on the size of the sphere, construct a cuboid air domain with appropriately scaled truncation boundaries. Due to the symmetry of the magnetic field disturbed by the eddy currents in the sphere, the simulation model can be divided along its symmetry plane, simulating and analyzing only half of the model. Appropriately increase the mesh density of the sphere model and the surrounding space to improve computational efficiency and accuracy. Typically, in the ship coordinate system, the ship is symmetrical about the plane y = 0, so only the portion where y > 0 is simulated and analyzed. The meshing schematic is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Mesh generation for a spherical model.

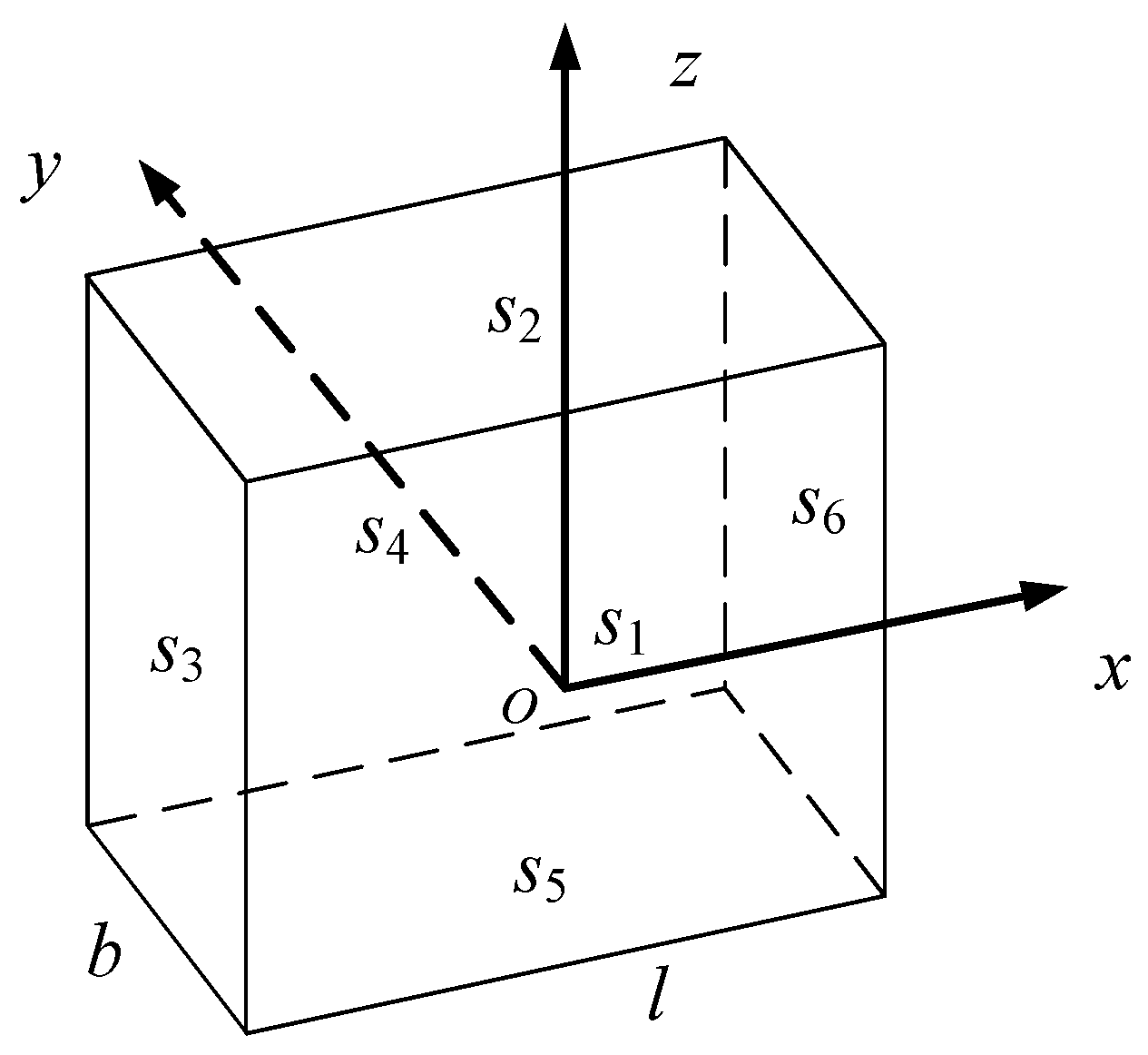

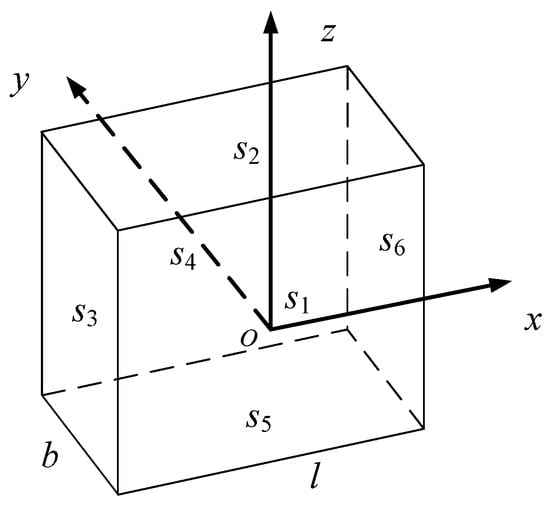

The schematic diagram of the truncated air domain constructed based on the reference simulation model is shown in Figure 13. The origin of the coordinates is located at the center of surface s1. The surfaces perpendicular to the x-axis are s3 and s6, those perpendicular to the y-axis are s1 and s4, and those perpendicular to the z-axis are s2 and s5. To generate an external excitation in the z-direction with a magnetic field of B0z = c sin (ωt) [nT], according to the relationship between magnetic flux density and the curl of the vector magnetic potential, the vector magnetic potential boundary conditions can be set as follows:

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of the air domain boundary.

In the equation, c is a constant that can be adjusted to control the amplitude of the external magnetic field excitation; ω is the angular frequency; l is the length of the truncated boundary in the air region. Based on the above boundary conditions, a uniform external magnetic field excitation in the z-direction, B0z = 10,000 sin (2πt) [nT], is applied within the air region, oriented along the positive z-axis, with a frequency of f = 1 Hz. According to Lenz’s law, under the action of the external excitation, the eddy current density on the plane y = 0 is perpendicular to the cross-section of the sphere, so it is also necessary to set the potential of its cross-section s1 to 0.

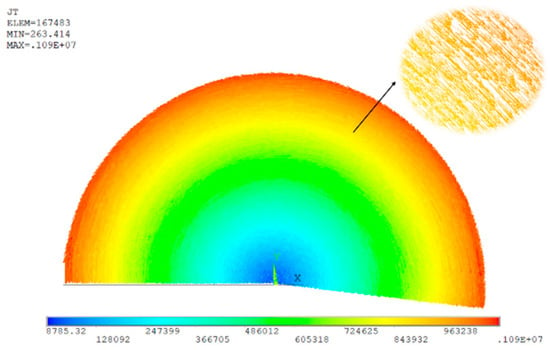

In the process of three-dimensional transient eddy current analysis, the simulation is set to run for two cycles with a time step of 0.001 s. The distribution of eddy currents at a certain time instant is shown in Figure 14, which reveals that the eddy currents are distributed in an arc shape, rotate around the z-axis, and the magnitude of the eddy currents in the longitudinal cross-section increases uniformly with the radius, consistent with the distribution pattern of magnetic fields disturbed by eddy currents. After the simulation is completed, the initially obtained results include the magnetic field disturbed by eddy currents, the applied magnetic field, and the induced magnetic field generated by the magnetic field excitation. To separate the component of the magnetic field disturbed by eddy currents, the electrical conductivity of the spherical material is first set to 0, and the simulation is carried out under identical boundary conditions to obtain the applied magnetic field and the induced magnetic field generated by the external field excitation. Then, by subtracting these two from the total magnetic field, the simulated solution of the magnetic field influenced by eddy currents can be obtained. The maximum value of the eddy current disturbed magnetic field at each measurement point over all time points is taken as the amplitude, and the phase is the relative phase of the eddy current disturbed magnetic field at the zero-crossing point with respect to the zero point of the excitation source.

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of eddy current of the sphere.

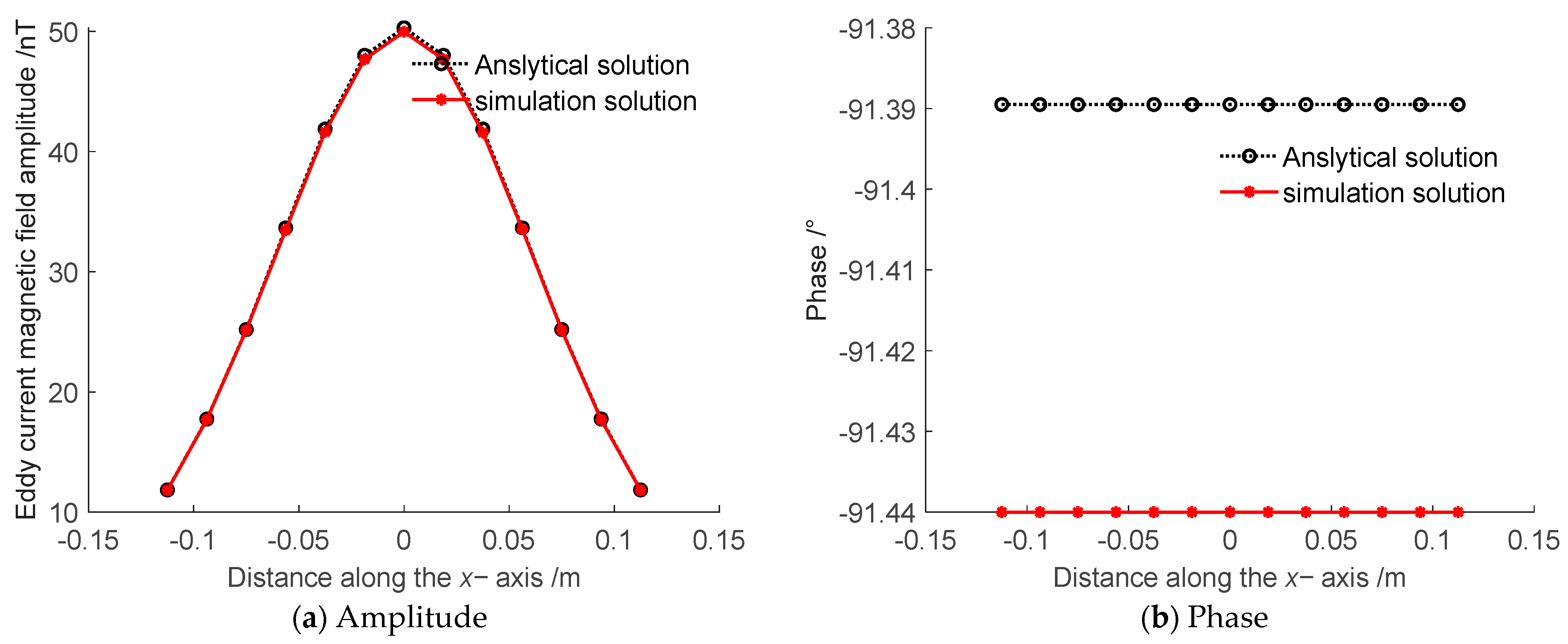

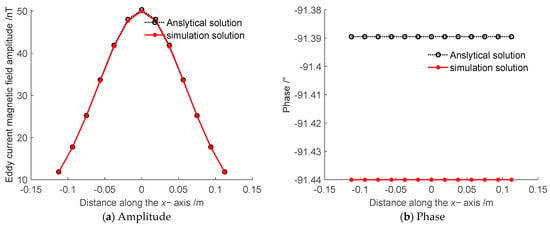

According to the system of Equation (16), the analytical solution of the eddy current disturbance magnetic field at the measurement points shown in Table 4 under the excitation of the applied magnetic field B0z is calculated. The analytical solution is in phasor form, with the magnitude representing the modulus of the analytical solution and the phase representing the phase angle of the analytical solution. The comparison results between the analytical solution and the simulation solution are shown in Figure 15a,b.

Table 4.

Coordinates of measuring points of sphere’s eddy current interference magnetic field.

Figure 15.

Comparison between numerical and analytical calculations of eddy current magnetic field of the sphere.

By comparing the analytical solution with the simulation results, it was found that the maximum relative error in the amplitude of the eddy current interference magnetic field at the measurement point is 0.7%, and the relative error in phase is 0.06%, indicating that the simulation accuracy is high. The simulation errors mainly arise from spatial discretization errors and temporal discretization errors: the amplitude error is primarily due to mesh division, and increasing the mesh density can further reduce the calculation error; the phase error is mainly caused by the simulation time step setting, and shortening the time step improves phase resolution, thereby enhancing calculation accuracy.

In summary, the finite element simulation results agree well with the theoretical calculations. For more complex models, when analytical calculations are not feasible, the eddy current interference magnetic field can be obtained through finite element simulation.

In order to further verify the effects of the mesh density and time step size on finite element simulations, especially under high-frequency conditions, the frequency of the external excitation is set to 10 Hz with the amplitude kept unchanged for the spherical eddy current magnetic field simulation. Referring to the above eddy current magnetic-field-extraction process, the measurement point coordinates are the same as those shown in Table 4, and the spherical eddy current magnetic field simulation solution is extracted. The analytical solution and simulation results of the spherical eddy current magnetic field under 10 Hz excitation are compared, and the maximum relative deviation of amplitude and phase are listed in Table 5. Then, the eddy current magnetic field simulation is carried out under conditions of a reduced mesh density and increased time step. Specifically, the mesh density is reduced by 1.2 times, and the time step is increased to 1.25 times. The amplitude and phase of the eddy current magnetic field are extracted for these two cases, and the maximum relative deviation of both are listed in Table 5. The maximum relative deviation is defined as follows:

where e represents the maximum relative deviation.

Table 5.

Effects of mesh density and time step on the amplitude and phase of eddy current magnetic field under 10 Hz sinusoidal excitation.

Table 5 shows that under high-frequency conditions, the mesh density and time step have little effect on the calculation results, proving that the mesh density and time step selected in the paper are relatively accurate.

4.3. Simulation of Eddy Current Magnetic Field in Aluminum Plates

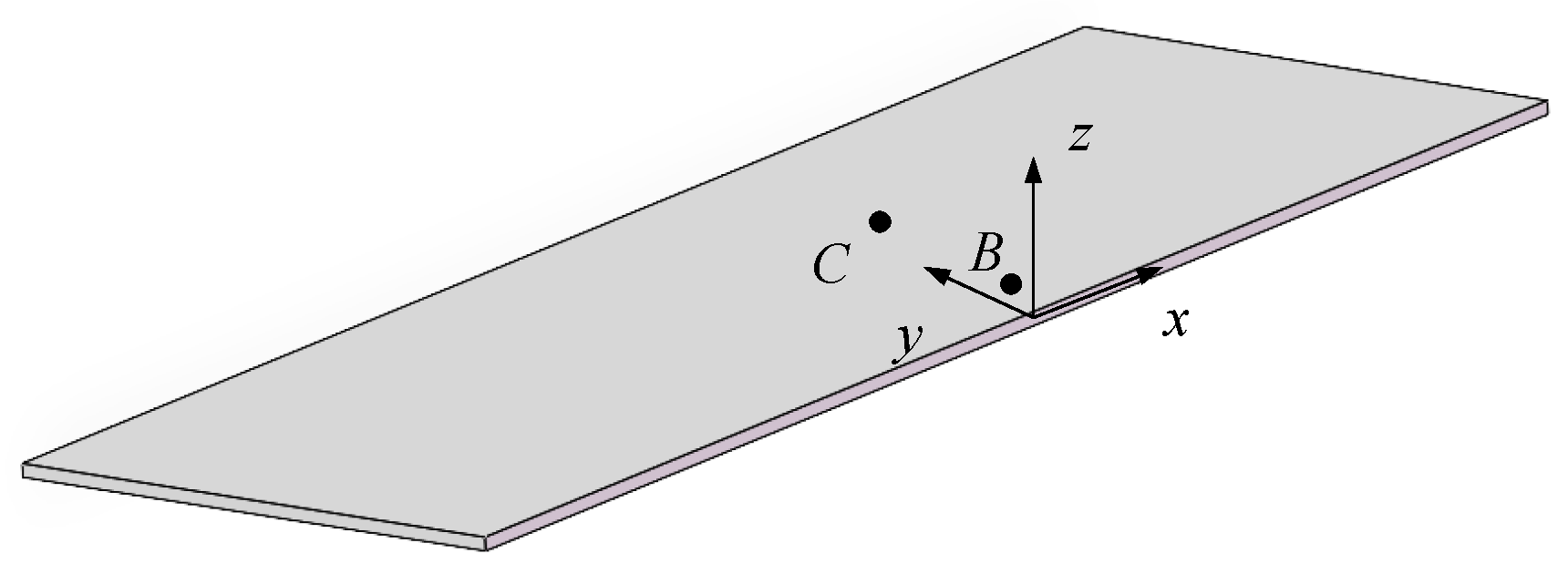

The previous section verified the accuracy of the FEM in calculating eddy current magnetic fields using a spherical model. Then, the FEM will be used to simulate and analyze the eddy current magnetic field of an aluminum plate. The simulation model is established based on the aluminum plate selected in the experiment, with the center of the aluminum plate set as the origin. The x-, y-, and z-axes are defined along the length, width, and height of the plate, respectively. The relative permeability of the aluminum is set to 1, and its electrical conductivity is set to 24.96 MS/m [31]. A cuboid air domain with an appropriate scale is constructed to truncate the boundaries according to the dimensions of the aluminum plate. Due to the symmetry of the eddy current magnetic field in the aluminum plate, the simulation model can be divided along its symmetry plane, and a half-model where y ≥ 0 is used for the simulation analysis. To improve the computational efficiency and accuracy, the mesh density of the aluminum plate model and its surrounding space should be increased. This is because the accuracy of the FEM is directly related to the mesh density. The denser the mesh, the smaller the discretization error and the closer the simulated value is to the actual situation. By focusing the refinement on the measured object or key areas, it ensures the reliability of the results of interest while avoiding the computational resource waste caused by excessive discretization of the entire domain. Based on the coordinates of the measurement points listed in Table 1, only measurement points B and C are selected during the simulation, as shown in Figure 16. Finite element mesh discretization of the aluminum plate is presented in Figure 17.

Figure 16.

Schematic of the half-size aluminum plate model.

Figure 17.

Finite element mesh discretization of the aluminum plate.

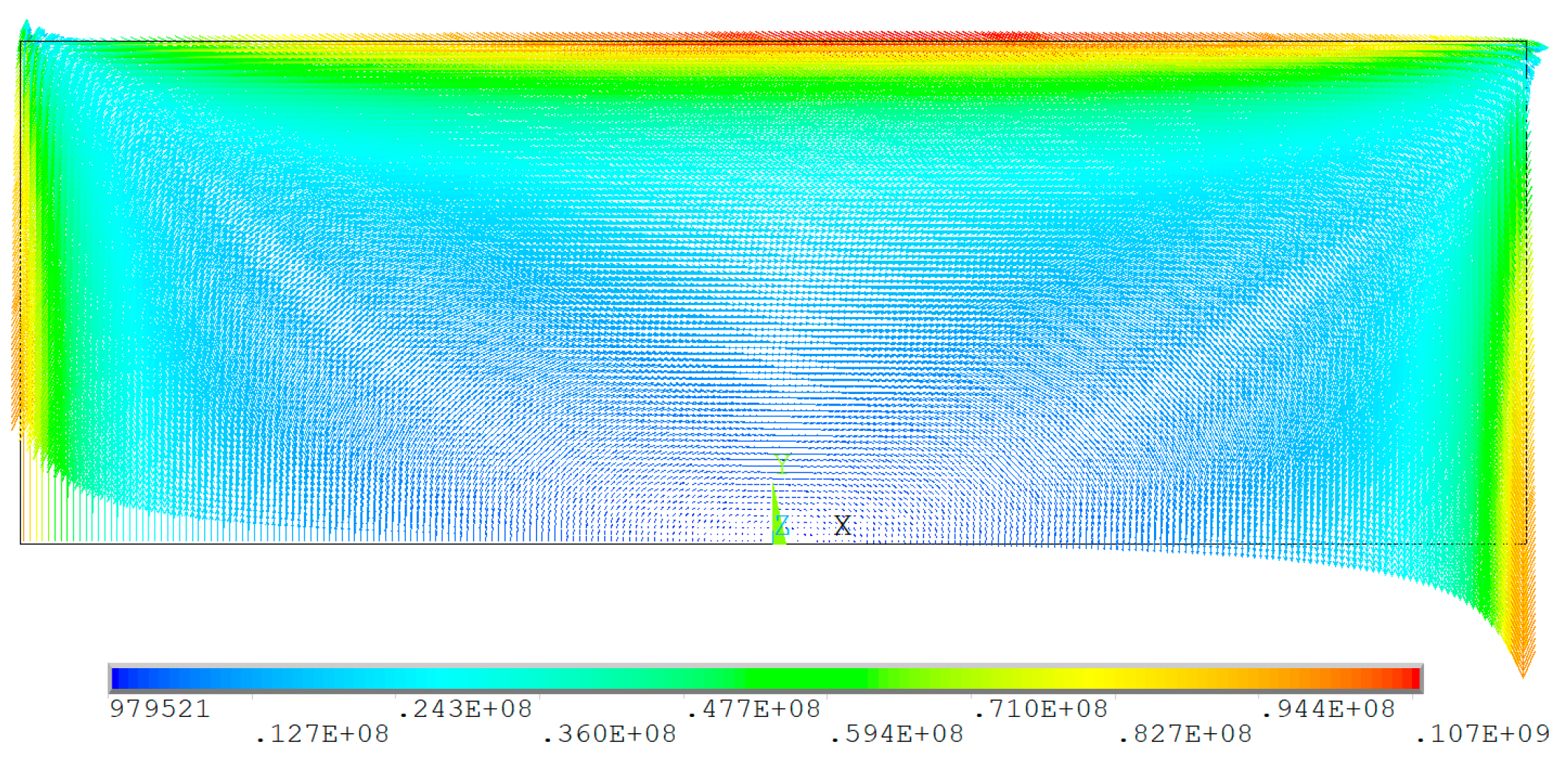

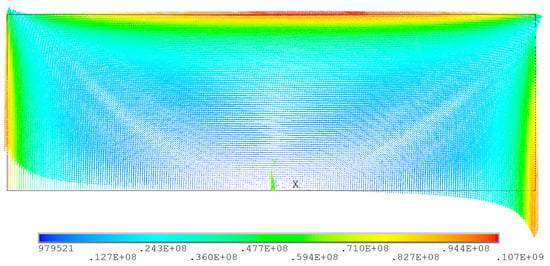

The vector magnetic potential at the truncated boundary of the air domain is set according to the different excitation settings used during the experimental measurement. This configuration is designed to generate a uniform excitation across the entire air domain along the positive z-direction. The simulation time for the ramp excitation is set to 0.28 s. Given that the ramp excitation induces significant transient variations in the eddy current magnetic field initially, a variable time step setting is adopted. Specifically, a time step of 0.001 s is used for the first 0.08 s of the simulation to capture the transient details, and the subsequent time step is adjusted to 0.01 s. For the sinusoidal excitation, the simulation duration is set to two cycles at the corresponding frequencies, with step sizes of 0.02 s, 0.01 s, 0.004 s, and 0.002 s for frequencies of 1 Hz, 2 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz, respectively. Based on the FEM, three-dimensional transient eddy current magnetic field numerical calculations are performed on the aluminum plate. Taking the 5 Hz sinusoidal excitation as an example, the eddy currents generated in the ship at a specific moment are illustrated in Figure 18. The eddy currents rotate clockwise, consistent with the eddy current distribution pattern of the aluminum plate under z-direction excitation.

Figure 18.

Schematic diagram of eddy currents density in aluminum plate.

Obviously, the initially obtained results at the measurement points contain both the eddy current magnetic field of the aluminum plate and the applied magnetic field. To isolate the eddy current magnetic field component, the electrical conductivity of the aluminum plate material is set to 0, and the applied magnetic field is obtained through simulation under the same boundary conditions. Subsequently, the applied magnetic field is subtracted from the total magnetic field to derive the simulated values of the eddy current magnetic field.

5. Results and Discussions

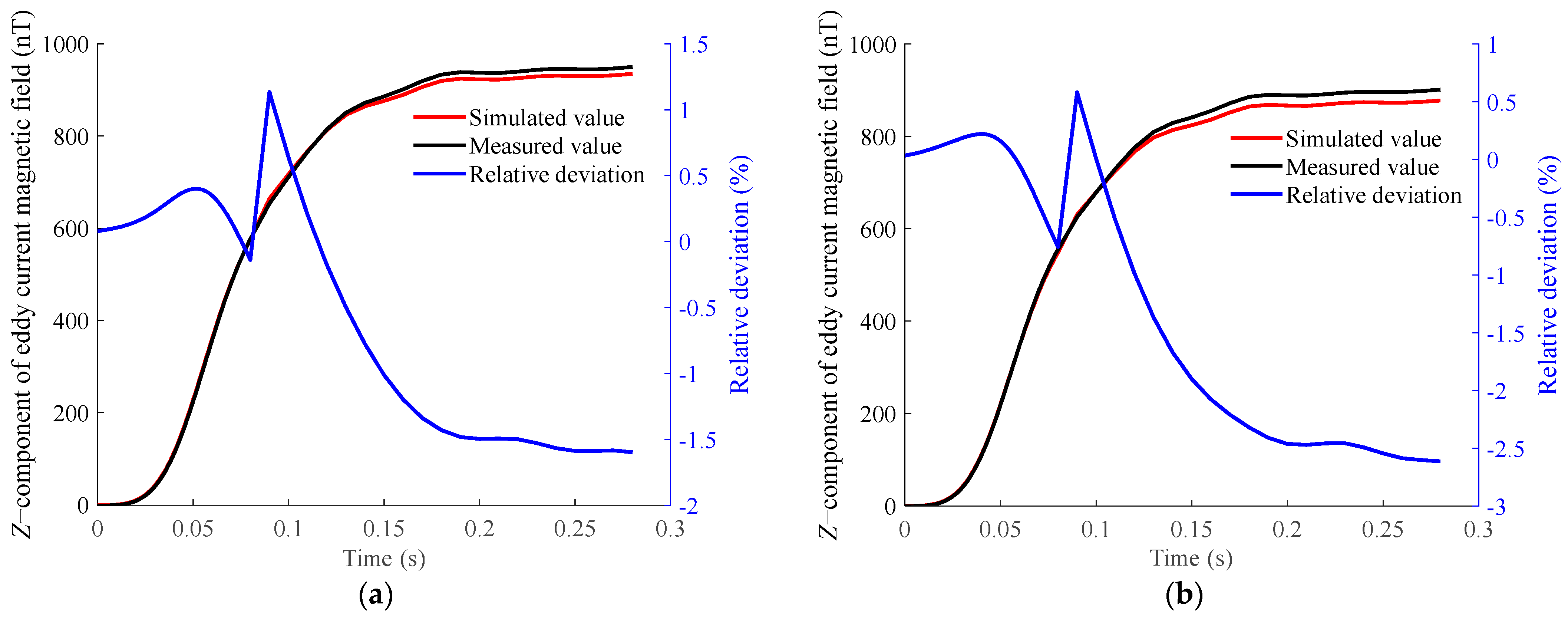

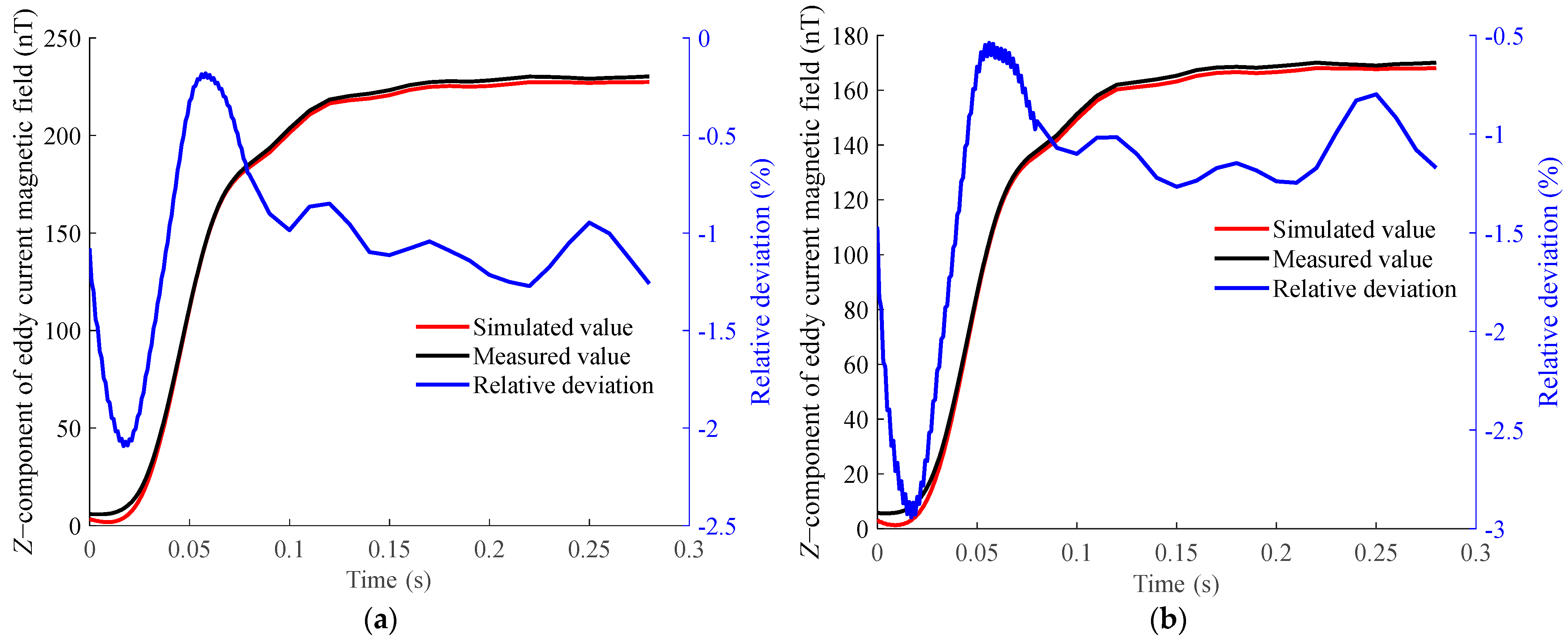

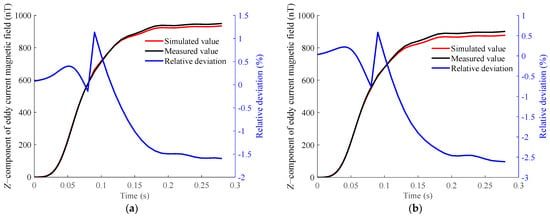

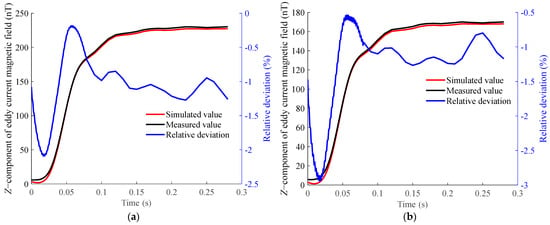

Since the z-component of the eddy current magnetic field dominates in this experiment [30], the simulated values and measured values of the z-component of the aluminum plate’s eddy current magnetic field under different excitation conditions are primarily compared. When the applied magnetic field is a ramp magnetic field, the comparison between the measured and simulated values is shown in Figure 19. The relative deviation is defined as follows:

where re represents the relative deviation, Bm represents the measured values in units of nT, and Bs represents the simulated values in units of nT.

Figure 19.

Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the aluminum plate at different measurement points under ramp magnetic excitation. (a) Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the aluminum plate at measurement point B. (b) Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the aluminum plate at measurement point C.

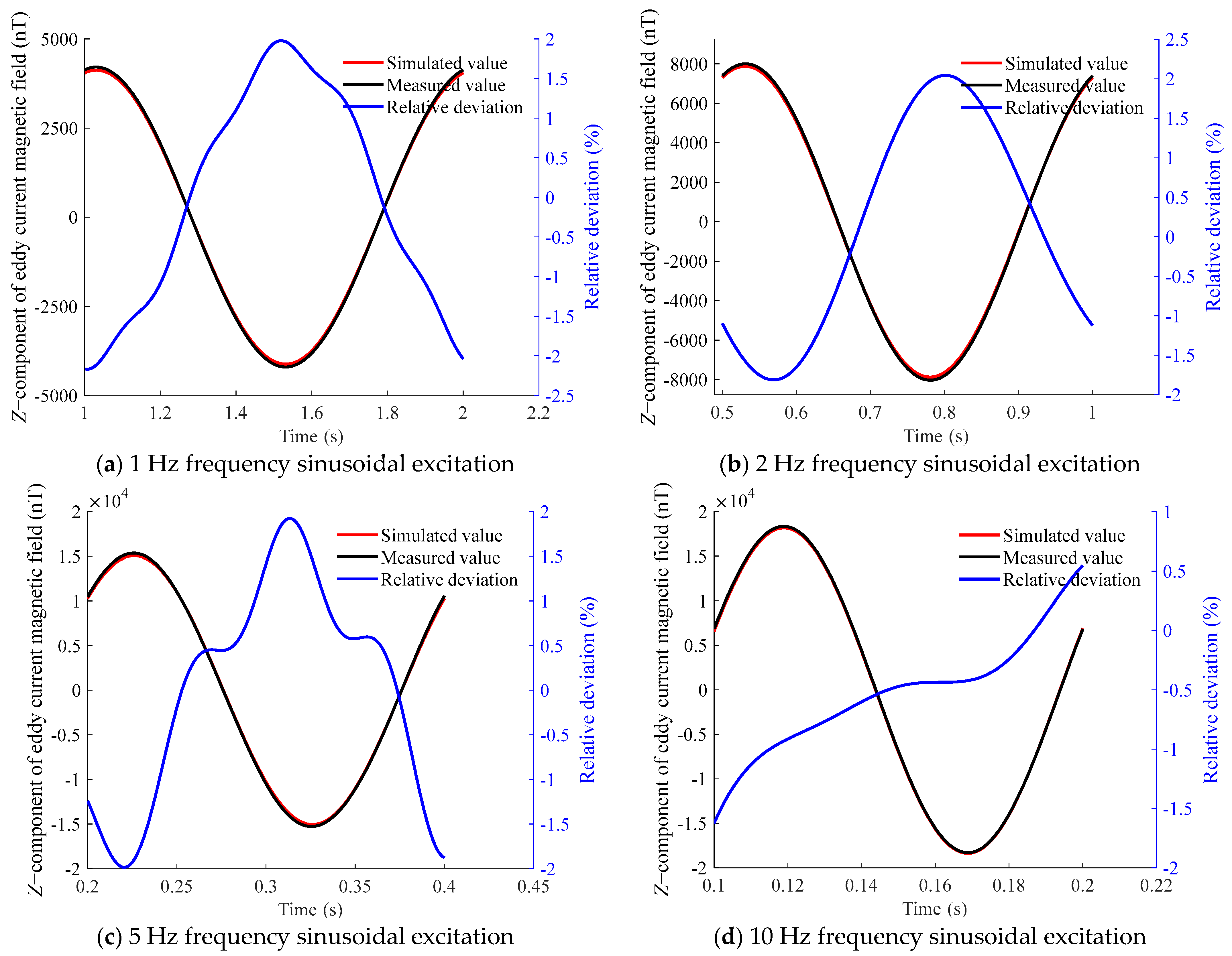

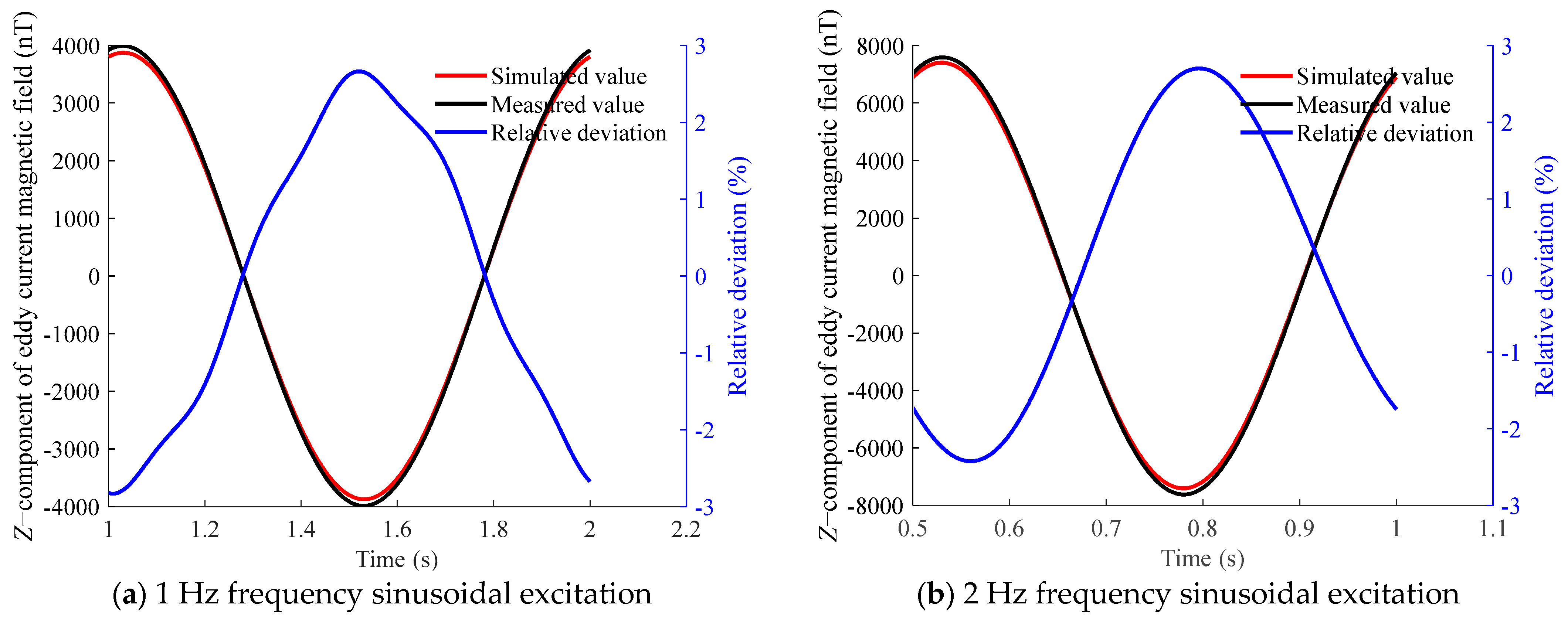

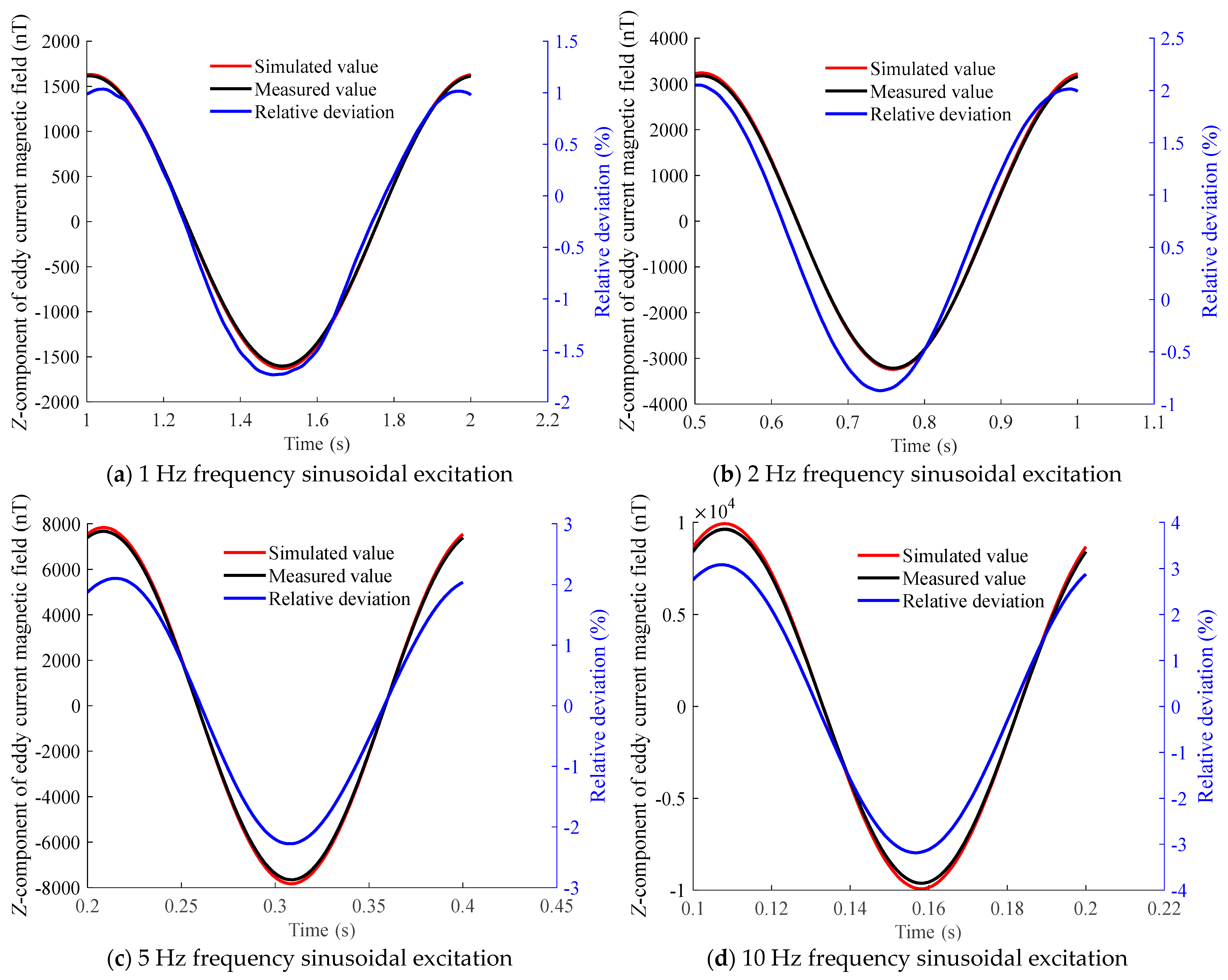

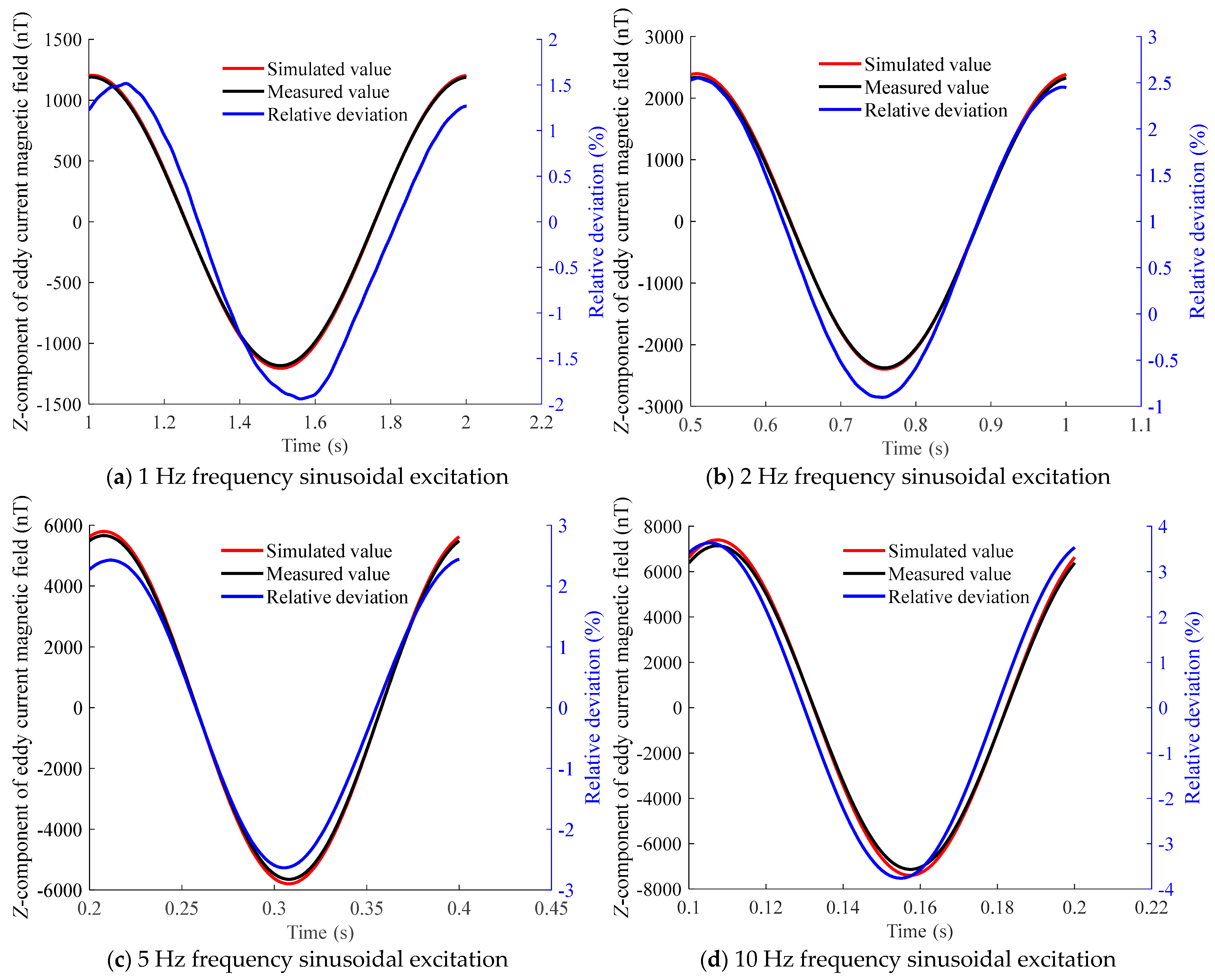

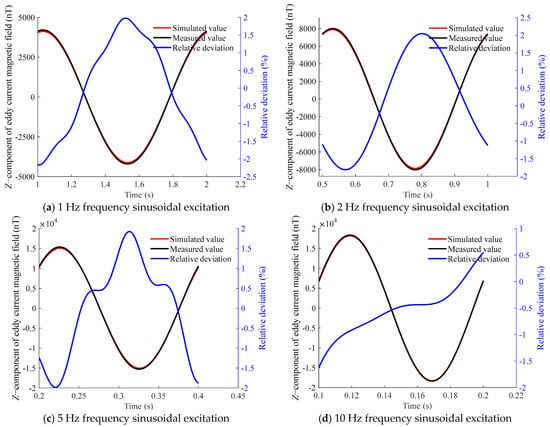

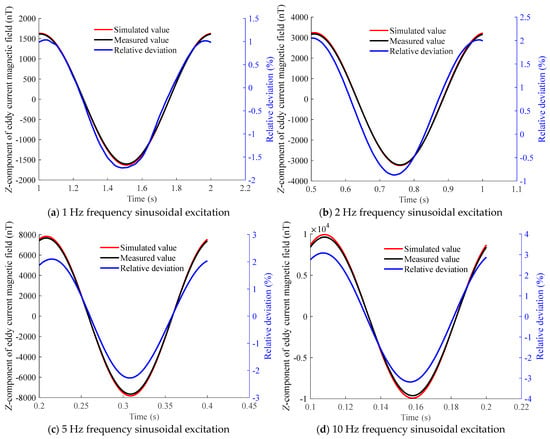

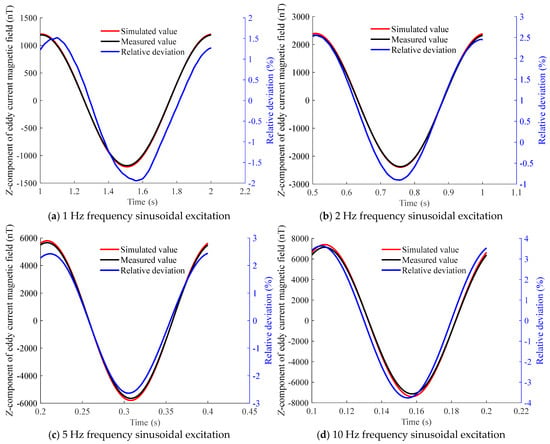

When the applied magnetic field is a sinusoidal magnetic field, the results are selected from the second cycle because the eddy currents in the first cycle require a certain transition time. The simulated and measured results at different frequencies are compared, as shown in Figure 20 and Figure 21, with the maximum relative deviation presented in Table 6 (taking the z-component as an example).

Figure 20.

Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the aluminum plate at measurement point B under sinusoidal excitation at different frequencies.

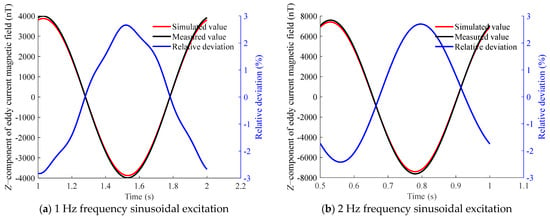

Figure 21.

Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the aluminum plate at measurement point C under sinusoidal excitation at different frequencies.

Table 6.

Maximum relative deviation of the z-component of the eddy current magnetic field at measurement points above aluminum plates under different excitations.

The comparison reveals a high degree of consistency, with a maximum relative deviation not exceeding 3%. This demonstrates that the proposed eddy current magnetic-field-measurement method achieves high accuracy.

Since geomagnetic fluctuations may occur during the process of magnetic field measurement and measurement errors of the magnetic sensor itself may exist, it is necessary to further analyze the sensitivity of this measurement method. Random noise of ±10 nT was added to the measured values of the eddy current magnetic field on the aluminum plate, to observe the impact of noise on the measurement results under different excitations. The maximum relative deviation is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Maximum relative deviation of the z-component of the eddy current magnetic field at measurement points above aluminum plates under different excitations adding ±10 nT random noise.

Compared with Table 6, the measured values with random noise of the eddy current magnetic field on the aluminum plate are still close to the simulated values, with a maximum relative deviation of only 3.64%, indicating good robustness of the method.

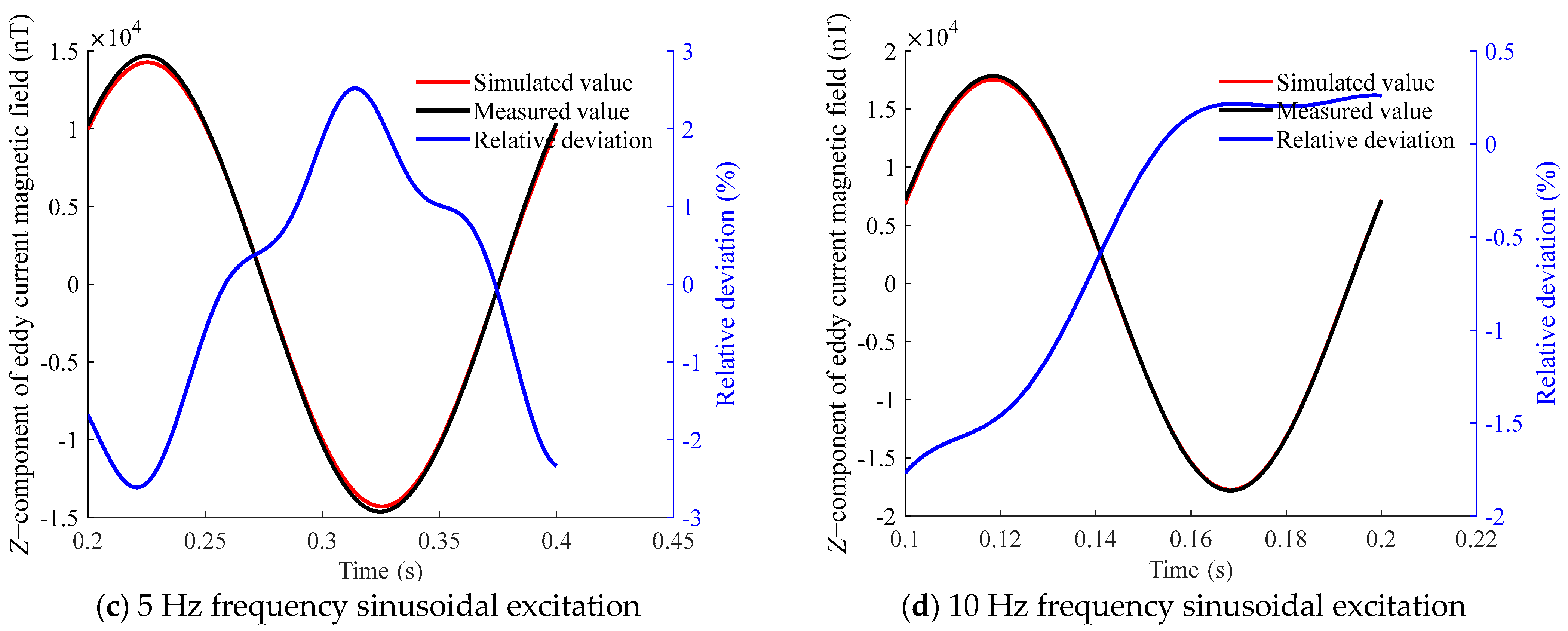

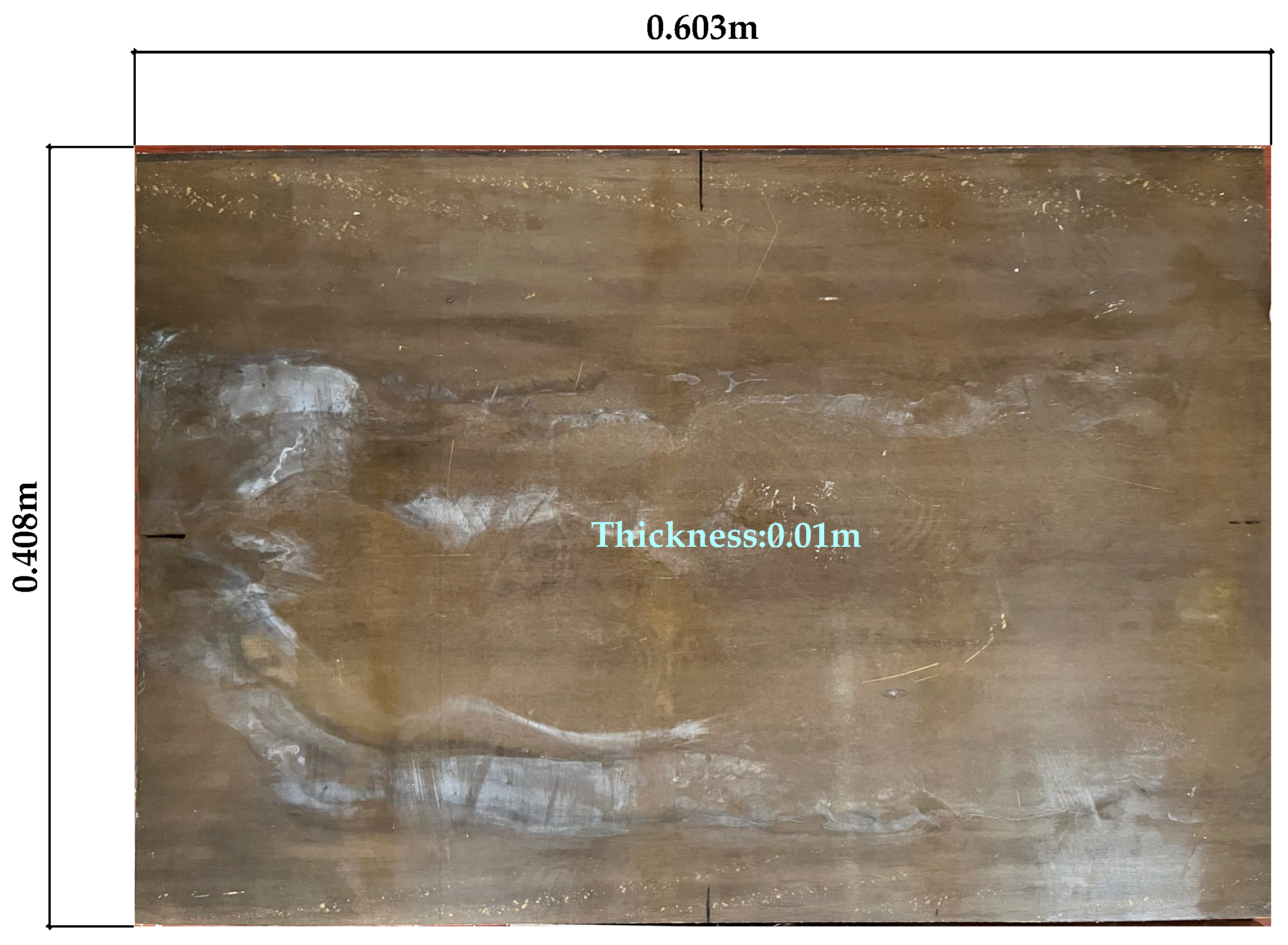

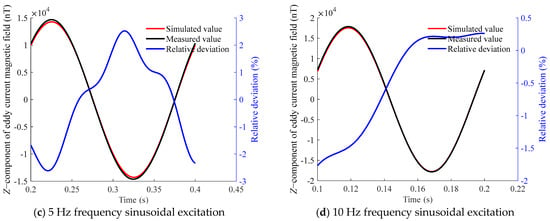

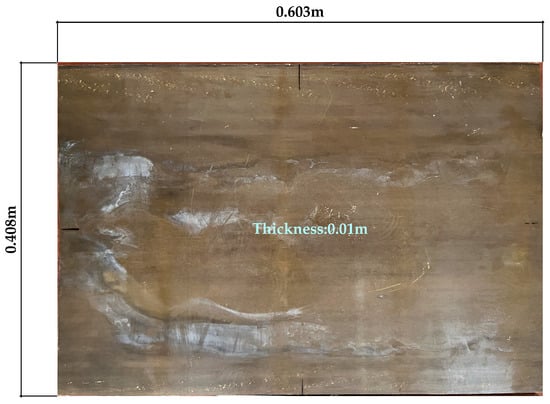

To further verify the feasibility and repeatability of the aforementioned method for non-magnetic metals, a brass plate was selected another the research object. The dimensions of the brass plate were 0.603 m × 0.408 m × 0.01 m, as shown in Figure 22. The relative permeability is 1, and the electrical conductivity is 14.08 MS/m [32]. Only the peak value of the sinusoidal current was changed to 11.3 A, while all other experimental and simulation conditions remained the same. The simulation and measured values of the eddy current magnetic field on the brass plate under different excitations were compared, as shown in Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25, with the maximum relative deviation listed in Table 8.

Figure 22.

Photo of the brass plate.

Figure 23.

Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the brass plate at different measurement points under ramp magnetic excitation. (a) Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the brass plate at measurement point B. (b) Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the brass plate at measurement point C.

Figure 24.

Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the brass plate at measurement point B under sinusoidal excitation at different frequencies.

Figure 25.

Z-component of the eddy current magnetic field above the brass plate at measurement point C under sinusoidal excitation at different frequencies.

Table 8.

Maximum relative deviation of the z-component of the eddy current magnetic field at measurement points above the brass plates under different excitations.

In conclusion, the maximum relative deviation between the simulated and measured values of the eddy current magnetic field in the brass plate under different excitation conditions is below 5%. This indicates that the method can be applied to different non-magnetic metals and has good feasibility and repeatability.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a novel approach for the eddy current magnetic field measurement of non-magnetic metals and validates it through experimental and numerical studies on an aluminum and brass plate. The principal conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- By placing background magnetic sensors outside the EFS, the coil current can be effectively calibrated, thereby filtering out the coil magnetic field from the eddy current magnetic field measurement magnetic sensors readings. It avoids repeated errors caused by repeatedly energizing the simulated coil and ensures the synchronization of current and magnetic field measurements.

- (2)

- The background eddy current magnetic field is modeled and solved by equivalating it to a first-order RL circuit. The high consistency between the calculated and measured values confirms the validity of this equivalent model and the effectiveness of the background field filtering strategy.

- (3)

- FEM simulations of the eddy current magnetic field in the non-magnetic metal plates are carried out. Under various excitation conditions, the maximum relative deviation between the simulated and measured values does not exceed 5%. It indicates that the proposed method for measuring eddy current magnetic fields in non-magnetic metals has high measurement accuracy, verifying its feasibility and accuracy.

This study provides an important methodological reference for eddy current magnetic-field-measurement technology. It can be effectively applied to the measurement of eddy current magnetic fields in non-magnetic ships. In the future, with appropriate adaptive modifications, this method can be applied to magnetic objects and further extended to magnetic ships, thereby advancing research on eddy current magnetic field measurements on ships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T.; methodology, Y.Z. and L.T.; validation, Y.Z. and L.T.; formal analysis, W.Z., Q.B. and G.Z.; data curation, Y.Z., L.T., Y.L. and S.L.; writing-original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing-review and editing, L.T. and W.Z.; project administration, L.T.; investigation, Y.L. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 52207020).

Data Availability Statement

The data involved in this paper is private and cannot be disclosed. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the National Natural Science Foundation for financial support and expresses gratitude to all participants of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Holmes, J.J.; Glover, B.A. Roll Induced Eddy Current Generated Magnetic Field Signatures; EMSS: Eckernförde, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J.J. Modeling a Ship’s Ferromagnetic Signatures; Synthesis Lectures on Computational Electromagnetics; Springer Nature: Basel, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 2, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.S.; Zhou, G.H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S. Numerical simulation of measuring ship’s induced magnetic field by geomagnetic field simulation method. Acta Armamentarii 2022, 43, 617–625. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.-S.; Guichon, J.-M.; Chadebec, O.; Labie, P.; Coulomb, J.-L. Ships magnetic anomaly computation with integral equation and fast multipole method. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2011, 47, 1414–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuillermet, Y.; Chadebec, O.; Coulomb, J.L.; Rouve, L.-L.; Cauffet, G.; Bongiraud, J.P.; Demilier, L. Scalar potential formulation and inverse problem applied to thin magnetic sheets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2008, 44, 1054–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnawski, J.; Buszman, K.; Woloszyn, M.; Rutkowski, T.; Cichocki, A.; Józwiak, R. Measurement campaign and mathematical model construction for the ship Zodiak magnetic signature reproduction. Measurement 2021, 186, 110059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnawski, J.; Cichocki, A.; Rutkowski, T.A.; Buszman, K.; Woloszyn, M. Improving the quality of magnetic signature reproduction by increasing flexibility of multi-dipole model structure and enriching measurement information. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 190448–190462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnawski, J.; Rutkowski, T.A.; Woloszyn, M.; Cichocki, A.; Buszman, K. Magnetic signature description of ellipsoid-shape vessel using 3D multi-dipole model fitted on cardinal directions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 16906–16930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woloszyn, M.; Tarnawski, J. Magnetic signature reproduction of ferromagnetic ships at arbitrary geographical position, direction and depth using a multi-dipole model. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.O.; Claesson, H.; Kjall, J.; Ljungdahl, G. Decomposition of ferromagnetic signature into induced and permanent components. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2020, 56, 6000106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, M. Processing of Shipborne Magnetometer Data and Revision of the Timing and Geometry of the Mesozoic Break-Up of Gondwana; Alfred Wegener Institute: Bremerhaven, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marc, M.; Simon, F. Scalar, vector, tensor magnetic anomalies: Measurement or Computation? Geophys. Prospect. 2011, 59, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeh, T.; Omar, K.A.; Fergany, E.; Abidin, Z.Z. Seismic-Magnetic effect of swarms and strong earthquakes along gulf of Aqaba Fault Segments in Egypt. Geotecton 2021, 55, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, M. Geomagnetism: An introduction and Overview. In Treatise on Geophysics, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 5, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Norgren, M.; He, S. Exact and explicit solution to a class of degaussing problems. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2000, 36, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.H.; Li, L.F.; Wu, K.N.; Liu, Y.; Xia, S. Numerical simulation of magnetic interference parameter identification of AUV based on L-SHADE algorithm. Acta Armamentarii 2024, 45, 2678–2687. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.W.; Zhou, G.H.; Liu, S.D.; Zong, J.; Tang, L. Computation of ship’s 3D magnetostatic field utilizing integral equation method of scalar magnetic potential. Acta Armamentarii 2024, 45, 948–956. [Google Scholar]

- Polanski, P.; Franciszek, S. Simulation and measurements of eddy current magnetic signatures. Marit. Tech. J. 2018, 215, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joga, R.K.; Chaturvedi, A.; Dhavalikar, S.; Girish, N. Importance of modelling equipment details and ship motions for magnetic signature predictions. In Conference Proceedings of INEC; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://library.imarest.org/record/7684?v=pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Wang, J.H.; Zhu, X.Y. Simulation detection method of the roll magnetic variation for measuring ship’s eddy current magnetic field. Mar. Electr. Electron. Technol. 2014, 34, 62–64+69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.F. The demagnetization facility at Yokosuka new has begun operation. Mine Warf. Ship Self-Def. 1995, 3, 36–38. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFQ&dbname=CJFD9495&filename=SLZH199503013 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Holmes, J.J. Reduction of a Ship’s Magnetic Field Signatures (Synthesis Lectures on Computational Electromagnetics); Morgan and Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J.J. Exploitation of a Ship’s Magnetic Field Signatures; Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- STO. Signature Management System for Underwater Signatures of Surface Ships; NATO STO Technical Report, TR SET-166 2015; STO: Dandenong South, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, T. Earth Magnetic Field Simulation in Lehmbeck. First Magnetic Ranging of Submarine U212A; EMSS: Eckernförde, Germany, 2012; Available online: https://www.sto.nato.int/document/signature-management-system-for-underwater-signatures-of-surface-ships/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Hendriks, B.R.; Daya, Z.A.; Katow, L.; Fraedrich, D.; Talbot, F.M.; se Jong, C.A.F.; Richards, T.C.; Constable, A.; Gilroy, L.; Makjem, M. Q340 Cruise Plan/RIMPASSE 2011 Trial Plan, DRDC-Atlantic-TN 2011. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2016/rddc-drdc/D68-5-151-2011-eng.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Marius, B.; Reinier, T. The effect of roll and pitch motion on ship magnetic signature. J. Magn. 2016, 21, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.J.; Wen, H.D.; Niu, L.; Chen, Z.; Xie, X.; An, D.; Xu, Z. Calculation of phase lag angle in eddy current magnetic field based on magnetic variation simulation method. Ship Boat 2025, 36, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.Z.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhou, G.H.; Zhao, W.; Bian, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Gao, J. Calibration of magnetic interfering coefficients for shipboard three-component magnetometers using a geomagnetic field simulator. Measurement 2026, 257, 118968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Zhao, W.C.; Tang, L.Z. Analysis of time-domain characteristics of ship eddy current interference magnetic field based on finite element simulation. J. Nav. Univ. Eng. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 6061 Aluminum. Available online: http://baike.baidu.com/l/jtjZPSeq?bk_share=copy&fr=copy# (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Technical Parameters of Metal Materials. Available online: https://wenku.baidu.com/view/63242a3ef111f18583d05aa3.html?_wkts_=1766544918433&bdQuery=H62Brassandconductivity (accessed on 20 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.