Abstract

Understanding the services provided by coastal ecosystems is vital for their study, preservation, and restoration. Mangrove forests, in particular, provide key ecosystem services: they sequester carbon, support fisheries and biodiversity, and facilitate sustainable tourism. In the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, mangrove-related services have been studied extensively, but often via fragmented approaches. This meta-analysis combines a literature review, bibliometric tools, and thematic mapping to identify emerging trends and long-standing gaps. We analyzed 61 peer-reviewed studies across 21 sovereign states and U.S. states, which highlighted shifting research priorities and a lack of convergence—defined herein as the failure of individual studies to examine multiple ecosystem service categories (regulating, cultural, supporting, and provisioning) simultaneously to assess potential trade-offs. While early research emphasized supporting services such as fishery nurseries, recent studies focus on regulating services, especially carbon sequestration. Stakeholder engagement remains limited, with only 18% of studies incorporating local perspectives. We argue for greater integration of stakeholder input and convergence across service categories to enhance the scientific basis for mangrove management and policy design.

Keywords:

mangrove; ecosystem services; bibliometric; VOSviewer; Bibliometrix; Caribbean; Belize; Gulf of Mexico 1. Introduction

Mangroves, distributed across tropical and subtropical regions, consist of over 50 species globally. In the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, mangrove diversity is more limited, dominated by three main species, red (Rhizophora mangle), black (Avicennia germinans), and white (Laguncularia racemosa) mangroves, along with an associate species—buttonwood (Conocarpus erectus). These species create distinct zonation patterns that reflect their ecological niches and together contribute to mangrove ecosystem functions in this region [1,2].

The term “mangroves” refers both to these plant species and to the ecosystems they dominate [1,2]. Despite regional differences, mangrove ecosystems in the western Atlantic region display a broadly consistent zonation pattern across coastal, riparian, and atoll environments, with Rhizophora mangle typically occupying the intertidal fringe closest to the waterline, followed landward by Avicennia germinans, Laguncularia racemosa, and then Conocarpus erectus. This zonation reflects the physiological tolerances of each species and contributes to the overall ecological structure and function of the ecosystem.

Mangrove ecosystems are increasingly recognized for their critical role in providing a wide array of ecosystem services, yet they are under mounting destructive pressure from climate change, coastal development, pollution, and hydrological disruption [1,3,4]. Historically, research has emphasized mangroves’ supporting services, such as nursery habitat for juvenile fish and invertebrates, but often without fully integrating the impacts of anthropogenic pressures and climate variability [5,6,7].

More recent studies have shifted the focus toward regulating services, including shoreline stabilization, carbon sequestration (i.e., blue carbon), and storm surge mitigation—functions that are gaining urgency in the face of rising sea levels and intensifying extreme weather events [8,9,10,11]. Additionally, mangroves contribute provisioning services such as timber and seafood and support cultural services, including recreation, tourism, and traditional practices.

Despite their recognized value, existing valuation methods—especially those based solely on market pricing or static cost–benefit frameworks—often fall short in capturing the long-term, context-specific, and intergenerational benefits that mangroves provide. These approaches rarely account for dynamic ecosystem responses, future climate scenarios, or the diverse needs and perceptions of local stakeholders [12,13,14,15,16,17]. This underscores the need for more integrative and adaptive valuation frameworks that can inform both conservation and policy decision-making. A more nuanced and integrative approach to ecosystem service valuation is therefore necessary—one that holistically considers ecological, economic, and social dimensions and aligns with the priorities of both local communities and global stakeholders [12,13,14,15,16,17].

In response to this need, we conducted a meta-analysis of peer-reviewed literature to identify both established research domains and emerging areas of inquiry within the study of mangrove ecosystem services. Our analysis places particular emphasis on how different categories of services have been prioritized across time and disciplines.

This synthesis enables the identification of evolving research priorities and thematic trends. Notably, regulating services—such as blue carbon sequestration—have received increasing attention due to their relevance for climate mitigation and carbon market frameworks. By tracing the trajectory of such themes, this meta-analysis provides insight into how scientific and policy interests have shifted and how future conservation strategies might be more effectively framed.

Furthermore, our findings reveal spatial and disciplinary imbalances in the literature. Some geographies and ecosystem services are disproportionately represented, while others remain underexplored despite experiencing significant ecological threats or socio-economic dependencies. The analysis also surfaces the extent to which stakeholders are incorporated into ecosystem service assessments, revealing gaps in participatory and interdisciplinary approaches.

This study advances the field through three specific methodological innovations. First, it integrates data from the Ecosystem Services Valuation Database (ESVD) with the Web of Science Core Collection to capture a broader spectrum of valuation studies often missed in standard bibliometric queries. Second, it combines the complementary strengths of VOSviewer 1.6.20 and Bibliometrix 4.0.0—two types of bibliometric software—to perform a multi-dimensional analysis of network visualization and thematic evolution. Third, unlike traditional reviews, we apply Optimized Hotspot Analysis (OHS) to georeference study sites, allowing for the statistical identification of spatial research gaps. This novel framework provides a comprehensive roadmap of ‘what’ is being studied, ‘where’ the research is concentrated, and ‘who’ is excluded. The innovative contribution of this study lies in examining existing scientific materials using new bibliometric methodologies. All researchers bring an inherent bias to their studies and understandings in a literature review. By relying on robust and analytical approaches of bibliometrics, we aim to present a complete report of both the presence and absence of studies of ecosystem services of mangroves in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean.

To structure our meta-analysis, we pose the following research questions:

- Which categories of mangrove ecosystem services are most frequently examined in the literature, and how have these emphases shifted over time?

- Who are the key stakeholders identified or engaged in these studies, and how are their roles conceptualized?

- Are cultural ecosystem services addressed in natural science journals, or are they predominantly confined to social science literature?

- To what extent do published studies consider trade-offs among different ecosystem services, and how are these trade-offs framed?

2. Context: Mangroves and Regions of Interest

Mangrove forests are among the most productive and valuable coastal ecosystems on the planet. They provide a wide array of ecosystem services that benefit both human societies and the natural environment. These services span regulating, supporting, provisioning, and cultural categories. As global awareness grows around climate resilience and sustainable development, mangrove services are increasingly recognized not only for their ecological importance but also for their economic and social contributions.

2.1. Mangroves Regulate Coastal Erosion, Storm Surge, Water Quality, and Carbon Sequestration

The regulatory services of mangroves have long been established as highly important. They benefit both the natural ecosystems around them and human communities, both locally and globally [18,19]. On a local scale, mangrove forests protect against erosion, storm surge, and wastewater, leading to healthier and safer environments. On a global scale, the role of mangroves as a form of blue carbon cannot be understated.

In mangrove habitats, both in the Caribbean basin and globally, the loss of mangroves affects elevation changes and increases erosion [20,21,22,23,24]. Elevation changes can lead not only to further loss of mangroves but also affect human development and other critical ecosystems, such as littoral forests and savannah [25,26,27]. As many Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico coastlines have a very narrow elevation gradient, even small losses can vastly change ecosystem distributions [20,25,26,27]. As climate change increases the strength and frequency of extreme weather, mangroves have become critically important in their role of attenuating storm surge [28,29,30]. Mangroves can decrease both wave height and speed, as well as help dissipate stormwater inundation [28]. Mangrove roots regulate water quality to the surrounding ecosystems—both terrestrial and marine [31]. Similar to how mangrove roots provide protection to small fish from predators, these roots also become traps for debris and pollutants [32,33,34,35]. This includes not only human debris, such as plastic and refuse, but also woody debris [36].

Sea level rise, erosion, and oil spills are having devastating effects on mangrove habitats and their associated regulatory services. Sea level rise puts higher pressure on mangroves’ ability to regulate the effects of storm surge [29]. In areas where mangroves have been removed, they are often not able to be reestablished due to eroded environments. Over three-fourths of the entire Caribbean coast is at risk of oil spills [37,38]. Mangroves are incredibly challenging to remove oil from because of their network of roots [37,38]. After an oil spill in the 1980s, not only did mangroves die and defoliate, but there were also severe losses in the biodiversity that lived on and around their elaborate root systems [37]. This included oysters, which are an indicator species and provide easy access to scientists to understand the pollutants in and around mangroves [37,39].

Carbon sequestration in mangroves is considered “blue carbon” [40,41]. Although this term has been around for the last decade, it has gained momentum in recent years [42,43]. In the past, coastal blue carbon sites have been overlooked for more obvious terrestrial carbon sinks [42]. Now, governments around the world are working to quantify their blue carbon sequestration [11,44,45,46]. Mangroves not only sequester carbon in their limbs, roots, and trunks but also in the soil beneath them. In fact, their soil sequestration rates are higher than those found in any other ecosystem on the planet.

The main threat to carbon sequestration rates is limits on tree growth rates [47]. The limiting factors of growth in Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean mangrove forests include nutrition, salinity, and inundation, all of which fluctuate due to anthropogenic climate change [48,49,50]. Although current rates have been calculated extensively, there is a unique possibility that these rates may not be accurate in the future climate [40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

2.2. Mangroves Provide Supporting, Provisioning, and Cultural Services

Mangroves support an incredible amount of biodiversity and are a vital nursery habitat for both commercially and recreationally important fish, invertebrates, and bird species [51,52,53,54]. Globally, hundreds of species call mangroves home at some point in their life cycle, including thirty percent of all fish [53,55]. The nursery services for fish of Caribbean mangroves are well established [56,57]. In fact, scientists suggest that there are higher densities of juvenile fish in Caribbean mangroves than found anywhere else in the world [58]. Studies have shown that seagrasses that are adjacent to mangroves have significantly more larvae present than seagrasses not in proximity to mangroves [59]. The proximity of mangroves can double the biomass of certain species of commercial fish seen on associated reefs and seagrasses [51].

Several birds are characteristic of the mangrove forests of the Caribbean, including the mangrove hummingbird (Amazilia boucardi) and a subspecies of Osprey (Pandion haliaetus ridgwayi) [2,60]. Black mangroves are incredibly important in facilitating successful migrations through Belize, with almost 1800 individual birds per km2 per year relying on mangrove forests [61]. Some birds overwinter in mangroves, such as the rufous-necked wood rail (Aramides axillaris), while others often nest there, including osprey as well as Yucatan vireos (Vireo magister), mangrove yellow warblers (Setophaga petechia castaneiceps), mangrove cuckoos (Coccyzus minor), great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus), and white-crowned pigeons (Patagioenas leucocephala) [2]. These rookeries can lead to further degradation as nutrient overloads lead to unhealthy growth in mangroves. Healthy mangrove branches will be similar in size to their prop roots, but the influx of nitrogen from bird feces leads to greater branch growth than the roots can support [62]. Their height and aboveground biomass are too great to be properly supported by their insufficient prop roots [62].

Globally, it is well documented that mangroves provide both fish and wood directly to local stakeholders for their livelihoods [63,64]. However, in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, there are limited studies that examine these services [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. One study found that in Florida, most people fishing directly in mangroves came from low-income and Black backgrounds [72]. This suggests that in Florida, this provisioning service is also one of environmental justice and equal access. Tourism in mangroves is becoming more common, with over ninety countries and territories now advertising mangrove-related attractions [73]. These are largely made up of wildlife tours, from bird watching to manatee viewing to monkey sightings [73]. By portraying mangroves in the Caribbean as almost a spiritual place to visit, tourism agencies have increased business [74]. With mangroves becoming a tourist attraction, there is an increase in pollution in mangroves. Thus, these very tourism aspects are also rapidly degrading mangrove environments, leading to an increasing push for governmental policies to protect them [75,76].

2.3. Stakeholder Engagement Is Vital to Mangrove Futures

Engaging stakeholders in mangrove research and policy design is increasingly recognized as essential to ensuring effective and equitable conservation outcomes [77]. Stakeholders—defined as individuals or groups with a vested interest in a habitat or decision—include local residents, tourists, fishers, policymakers, NGOs, and private sector actors [78,79,80,81,82].

Understanding how different stakeholder groups value mangrove ecosystem services is crucial for assessing trade-offs, designing incentive structures, and promoting long-term stewardship [83,84]. While stakeholder engagement is gaining traction in recent studies, it remains underrepresented in older literature and is especially sparse in quantitative ecosystem service valuation efforts.

In urban coastal areas, stakeholders interact with mangroves on a daily basis—through fishing, tourism, flood exposure, and cultural practices—making their perspectives central to adaptive restoration strategies [79,85]. However, the inclusion of global stakeholders is almost entirely absent from current studies. This is a critical oversight, as the benefits of climate regulation (e.g., blue carbon) extend well beyond national borders [86,87].

This analysis highlights a significant knowledge gap: to effectively manage and finance mangrove ecosystem services, particularly in the context of climate and social justice, stakeholder engagement must become a core component of ecosystem service science in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

3. Materials and Methods

Historically, literature reviews have employed both qualitative and quantitative approaches to synthesize background knowledge on a given subject. In this study, we integrate a traditional narrative literature review with bibliometric analysis to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research landscape surrounding mangrove ecosystem services. Bibliometric analysis leverages software tools to examine patterns across article metadata—including titles, abstracts, keywords, and author networks—typically derived from citation databases such as Web of Science.

Given that bibliometric methods are still evolving, we employed two complementary tools: VOSviewer and Bibliometrix. Each offers distinct functionalities in visualizing co-authorship networks, keyword co-occurrences, and thematic trends. By utilizing multiple bibliometric methods, we hope to eliminate biases from either software and promote a clear understanding of each method’s successes and shortcomings. While our primary objective is to examine the valuation and categorization of mangrove ecosystem services in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, we also explore the methodological potential of combining these two software tools to generate a more cohesive, scalable framework for future literature reviews. We utilized both tools because they offer distinct, non-overlapping analytical strengths. VOSviewer was selected specifically for its superior cluster visualization capabilities, particularly for term co-occurrence and author networks. Conversely, Bibliometrix was employed for its statistical diagnostic tools and ‘factorial analysis,’ which allows for the tracking of thematic evolution and annual growth rates that VOSviewer does not provide.

Our methodology follows established protocols for systematic review and evidence mapping [88,89,90]. Specifically, we draw on the structure of the Ecosystem Services Valuation Database (ESVD) to ensure consistent categorization and interpretation of service types across studies. Unlike unsystematic reviews, this approach emphasizes transparency, repeatability, and objectivity, increasing the reliability of findings and allowing for the identification of broader trends and generalizable insights. In the following section, we detail the analytical framework and search criteria used in our study.

3.1. Study Framework and Data Sources

The Ecosystem Services Valuation Database (ESVD) compiles global studies on the valuation of ecosystem services and classifies them using two major frameworks: the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) and the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) typology [91,92,93,94]. TEEB adopts a broader and more generalist schema, while CICES provides more granular and standardized categorizations of service types [95]. Although the ESVD contains studies from a wide range of geographic regions and ecosystem types, its emphasis tends to be on services that can be assigned monetary values [91]. We adopted the CICES framework because it offers a more granular and standardized categorization of service types compared to the broader, generalist schema of TEEB. This granularity was necessary to accurately classify specific services—such as distinguishing between specific regulation services—which allows for a more precise detection of convergence or trade-offs in the literature.

For this study, we queried the ESVD using the keyword “mangroves” (initial n = 999). We then filtered the dataset by removing duplicates and limiting the geographic scope to our focal regions: the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Based on this refined dataset, we identified 13 distinct ecosystem services in the region as classified under the CICES framework. The most frequently reported services were carbon sequestration, fisheries-related provisioning, and tourism-related cultural services.

To complement and expand upon the ESVD analysis, we conducted a systematic literature search in the Web of Science Core Collection. Our goal was to capture additional studies that may not explicitly frame their contributions in ecosystem service terminology but nonetheless provide relevant insights. We focused on publications in which the following key terms appeared in the abstract, using a search conducted on 31 July 2024:

((“ecosystem service*” OR “service*” OR “blue carbon” OR “carbon sequestration” OR “fisheries” OR “tourism”) AND “mangrove*” AND (“Gulf of Mexico” OR “Caribbean” OR “Antigua” OR “Barbuda” OR “Bahamas” OR “Barbados” OR “Aruba” OR “Bonaire” OR “Eustatius” OR “Saba” OR “Cura*ao” OR “Sint Maarten” OR “Saint Martin” OR “Guadeloupe” OR “Martinique” OR “Saint Barth*lemy” OR “Dominican Republic” OR “Haiti” OR “Navassa” OR “Puerto Rico” OR “Virgin Islands” OR “Anguilla” OR “Cayman” OR “Montserrat” OR “Turks” OR “Caicos” OR “Cuba” OR “Dominica” OR “Jamaica” OR “Grenada” OR “San Andr*s and Providencia” OR “Venezuela” OR “Nueva Esparta” OR “Trinidad” OR “Tobago” OR “Saint Kitts” OR “Nevis” OR “Saint Lucia” OR “Saint Vincent” OR “Grenadines” OR “Belize” OR “Florida” OR “Everglades”)).

3.2. Data Filtering

This search term allowed us to view not only the named Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean but also all sovereign states. We also included a search for some of the top ecosystem services as determined by analysis of the ESVD to capture ecosystem services that may not have been defined as ecosystem services by the authors. We only included documents that were written in English.

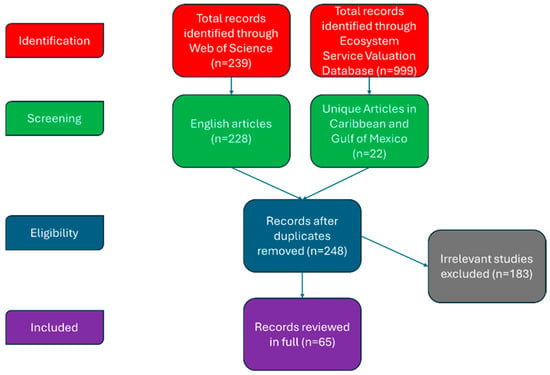

Building on the research questions outlined earlier, we developed a set of filtering criteria and query prompts to determine the relevance of each article and to assess how it addressed mangrove ecosystem services and stakeholder engagement. Two independent reviewers screened a total of 248 articles retrieved from our bibliometric and systematic searches. Only those studies that both reviewers agreed met our predefined inclusion criteria—based on two core filter questions (Table 1)—were retained for further analysis, resulting in a final set of 65 studies for in-depth review. VOSviewer and Bibliometrix both utilize Web of Science databases; as four of the studies we identified were not in the Web of Science database, they were excluded from the bibliometric analysis but included in the literature review.

Table 1.

Filter, quantitative, and qualitative questions for systematic literature review.

While bibliometric analysis provides a macro-level quantitative overview of trends and networks, it often fails to capture the nuance of how services are valued or why stakeholders are engaged. By integrating a narrative review, we ground the statistical patterns identified by the software (e.g., a cluster of ‘cultural’ terms) with qualitative context (e.g., who was actually interviewed), ensuring a holistic understanding of the research landscape. Therefore, to supplement the bibliometric analysis and capture dimensions not easily quantifiable through automated tools, we employed a structured qualitative coding framework. This included a set of targeted questions aimed at extracting contextual information from each study, such as:

- The geographic location of the research (regional: more than one country; national: multiple sites in one country or final conclusions presented at a country level; local: only one specific site or location);

- The category or categories of ecosystem services analyzed;

- Whether multiple ecosystem services were examined in convergence or trade-off;

- The extent and nature of stakeholder engagement.

These structured questions were critical for addressing the goals of this study and for identifying gaps in service representation and participatory inclusion. Table 1 presents the filter criteria, quantitative metrics, and qualitative prompts used in our systematic literature review protocol. Figure 1 shows the conceptual flowchart of the process used in this study.

Figure 1.

Framework for the evaluation of potential works to be included.

3.3. Comparative Bibliometric Methodology

To enhance the analytical depth and enable triangulation of findings, we employed two widely used bibliometric tools: VOSviewer and Bibliometrix. Each software package offers complementary strengths in mapping research landscapes—VOSviewer excels in visualizing co-authorship networks and term co-occurrences, while Bibliometrix provides more customizable statistical analyses and thematic evolution maps. In our analytical framework, VOSviewer was strictly employed for network visualization—mapping the distance and connection strength between terms and authors to identify thematic clusters. Bibliometrix was utilized for its statistical processing power, specifically to generate the ‘Trend Topics’ analysis and annual growth metrics that quantify the temporal evolution of these themes.

Because both tools support direct import of citation data from the Web of Science Core Collection, they were particularly well-suited for our dataset. Using these tools in tandem allowed us not only to examine trends in mangrove-related ecosystem service research but also to evaluate the functionality and interoperability of these bibliometric methods. Our approach thus contributes a secondary objective: assessing the potential of combined bibliometric platforms to enhance systematic reviews and narrative synthesis in future environmental research.

3.3.1. VOSviewer

VOSviewer is a bibliometric network visualization tool designed to map and analyze patterns in scientific literature. It supports the creation of two primary types of maps: text-based maps, derived from the co-occurrence of terms in article titles and abstracts, and bibliographic maps, which are generated from data such as co-authorship, co-citation, keyword co-occurrence, and bibliographic coupling.

In analyzing bibliographic data, VOSviewer offers two counting methods: full counting and fractional counting. Full counting assigns equal weight to each occurrence, regardless of the number of contributing authors or publications, while fractional counting adjusts weights based on co-authorship or other proportional factors. For the purposes of this study, we adopted full counting, as proportional representation was not central to our analysis. We also defined threshold parameters for inclusion in the visualizations—setting minimum occurrence levels for authors, keywords, or citations to ensure only the most relevant items were represented.

For the text-based term maps, we used binary counting, which considers only the presence or absence of a term in a document, rather than its frequency. This approach allowed us to focus on shared conceptual themes across article abstracts, rather than weighting individual articles more heavily based on internal term repetition. We set the threshold for term inclusion at a minimum of five occurrences. Out of an initial 2350 terms identified, 76 met this threshold. Following VOSviewer recommendations using artificial intelligence [96], we selected the 46 most relevant terms, which together accounted for approximately 60% of the term map’s explanatory power.

VOSviewer employs a layout optimization algorithm to organize terms into clusters, grouping related terms based on co-occurrence and semantic proximity. These clusters are visualized using multiple formats. In the Network Visualization, terms are positioned spatially according to their connections and grouped into color-coded clusters. In our study, the terms were separated into three distinct clusters, which are discussed in the Results section. In contrast, the Overlay Visualization retains the same spatial layout of terms but alters the color scheme to represent the average publication year associated with each term. This allows us to observe temporal trends in keyword usage, highlighting shifts in research focus over time.

3.3.2. Bibliometrix

Bibliometrix is a relatively recent bibliometric analysis tool that extends beyond the capabilities of VOSviewer by offering more customizable and statistical functionalities [96]. It imports data from the Web of Science and generates detailed summaries and diagnostics relevant to bibliometric surveys. These include publication trends, citation counts, co-authorship frequencies, and annual growth rates. Bibliometrix runs in R 4.4.0 and can be accessed through its user-friendly interface, Biblioshiny, allowing for interactive exploration and in-depth analyses.

For this study, we used Bibliometrix to identify trending terms in mangrove ecosystem services research, tracking both their frequency of use and temporal distribution. Specifically, we selected terms that appeared at least 10 times in abstracts over the course of the study period, with a minimum of two occurrences per year across the time series. This filtering enabled us to distinguish how research foci have shifted over time, offering insight into evolving scientific and funding priorities.

We further employed Bibliometrix’s factorial analysis module to explore term clusters and underlying semantic structures within the dataset. A noted limitation of this tool—compared to VOSviewer’s more flexible network analysis—is the requirement to predefine terms as unigrams (single words), bigrams (two-word phrases), or trigrams. As a result, compound terms like “coastal protection” could not be automatically grouped and instead were disaggregated into separate components (“coastal” and “protection”), potentially diluting thematic coherence.

Among the available factorial analysis techniques, we selected Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). MCA was particularly valuable in uncovering latent relationships between terms that may not be evident in co-occurrence networks, as it uses principal component analysis to visualize multidimensional word associations. In addition, we used Bibliometrix to generate country-level co-authorship networks, which provided insight into the global distribution of research collaborations. This is essential for understanding how scientific authorship aligns with the ecosystems being studied and the degree to which local stakeholders are involved—an important consideration for the credibility and impact of ecosystem service research.

By using VOSviewer and Bibliometrix in parallel, we aim not only to identify knowledge gaps in the literature on mangrove ecosystem services in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico but also to evaluate the strengths and limitations of these two bibliometric platforms. One notable constraint is that both tools are designed to process structured data exclusively from citation databases such as Web of Science. Consequently, several studies identified through the Ecosystem Services Valuation Database (ESVD) could not be incorporated into the bibliometric visualizations. However, these studies were still included in other aspects of our temporal, spatial, and qualitative analyses.

3.4. Results of Optimized Hotspot Analysis

To complement the bibliometric and textual analyses, we also examined the spatial distribution of study sites to identify geographic patterns and research priorities related to mangrove ecosystem services. For this, we employed Optimized Hotspot Analysis (OHS) in ArcGIS Pro 3.3, which uses spatial clustering and proximity analysis to identify statistically significant hotspots (areas of high study concentration) and cold spots (areas with few or no studies). OHS was selected over simple point density or kernel density estimation because OHS utilizes the Getis–Ord Gi* statistic to identify statistically significant spatial clusters. While density maps simply show where studies exist, OHS distinguishes between random concentrations and statistically significant ‘hotspots’ (90–99% confidence), providing a more robust basis for identifying true geographic research gaps.

Study locations were georeferenced based on information extracted manually by the reviewers. Where available, we used GPS coordinates reported in the articles. In cases where precise coordinates were not provided, we relied on named geographic features (e.g., Manatee River) to approximate study site locations as accurately as possible. We created spatial layers representing both the types of ecosystem services studied and the temporal distribution of research activity by location. This allowed us to visualize not only where different services—such as carbon sequestration, fisheries, or tourism—were being studied, but also how research attention had shifted geographically over time.

Finally, we ran the OHS algorithm to statistically determine areas with a high density of research activity versus those that are underrepresented in the literature. This spatial layer serves as a valuable diagnostic to highlight regional imbalances, informing both research agenda-setting and potential funding priorities.

4. Results

Following our filtering process, a total of 65 articles were retained for analysis. Of these, 61 articles were indexed in Web of Science and thus eligible for inclusion in the bibliometric analyses conducted using Bibliometrix and VOSviewer. These 61 publications span the period from 1992 to 2024, during which time the field experienced a 2.19% annual growth rate in the number of published articles.

Collectively, these studies involved 373 unique authors and were published across 41 different journals and conference proceedings. The average number of authors per document was 6.59, with only two articles authored by a single individual. Notably, the rate of international co-authorship—defined as the proportion of articles co-authored by researchers affiliated with institutions in different countries—was 42%, highlighting a strong level of global collaboration in mangrove ecosystem service research.

Among the publications analyzed, Mumby et al. (2004) stands out as the most highly cited study, with over 700 citations as of the date of data extraction [51]. Titled “Mangroves enhance the biomass of coral reef fish communities in the Caribbean”, the paper explores the nursery support functions that mangroves provide to adjacent coral reef ecosystems [51]. It has served as a foundational work in demonstrating the co-benefits of interconnected coastal habitats and is also the most highly cited publication in our dataset when normalized for years since publication [51].

Figure 2 presents a summary of key bibliometric statistics derived from the 61 mangrove ecosystem service-related publications included in our Web of Science-based analysis, spanning the period 1992 to 2024. This figure encapsulates the scope, collaboration patterns, and scholarly impact of the selected literature and serves as a baseline for deeper bibliometric and thematic analyses in this study.

Figure 2.

Summary of Bibliometrix findings related to articles.

4.1. Cluster Analysis

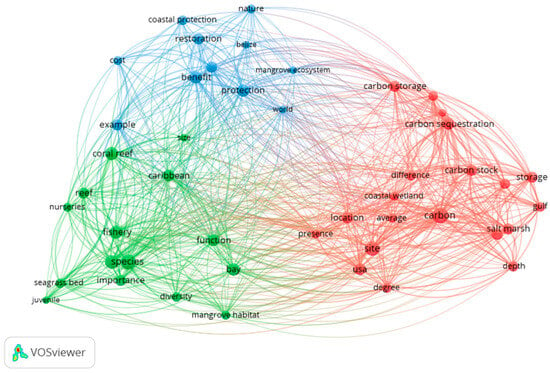

Figure 3 from VOSviewer presents a VOSviewer-generated co-occurrence network of terms extracted from the abstracts of 61 publications on mangrove ecosystem services in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. The network illustrates how frequently specific terms appear together, revealing thematic clusters within the literature. Each node represents a term, and links indicate co-occurrence strength. The clustering algorithm identifies three distinct thematic groupings, each shown in a different color.

Figure 3.

VOSviewer co-occurrence clusters. Colors are indicative of the three clusters. Clusters may overlap and contain multiple connections.

Green Cluster (Lower Left): This cluster centers on ecological functions and biodiversity-related terms such as “species,” “seagrass bed,” “juvenile,” “reef,” “nurseries,” and “fishery.” It reflects research focusing on habitat value, nursery functions, species interactions, and ecosystem diversity—especially in relation to juvenile development and seagrass–coral–mangrove connectivity.

Blue Cluster (Upper Center): This group includes terms such as “benefit,” “protection,” “restoration,” “coastal protection,” and “Belize.” It corresponds to studies examining the ecosystem service functions of mangroves, with an emphasis on protection, restoration, and regional case studies. The presence of words like “function” and “benefit” signals an ecosystem services framing—particularly related to disaster risk reduction, shoreline stabilization, and the socio-ecological value of nature-based solutions.

Red Cluster (Right Side): This cluster is composed of terms such as “carbon storage,” “carbon sequestration,” “carbon stock,” “salt marsh,” “depth,” and “coastal wetland.” It highlights research focused on blue carbon and climate mitigation, emphasizing the role of mangroves and related wetlands in sequestering atmospheric carbon. The term density in this cluster indicates a growing scientific and policy interest in quantifying carbon-related ecosystem services for climate action.

Together, these clusters show a clear thematic evolution in mangrove ecosystem services research—from biodiversity and habitat provisioning (green) to protective and socio-ecological functions (blue), to climate regulation and carbon sequestration (red). This structure also demonstrates how mangrove research is multidimensional, spanning ecological, economic, and climate-related domains. The sharp increase in carbon sequestration studies following 2016 aligns with the post-Paris Agreement global push for Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), where ‘blue carbon’ became a central mechanism for climate mitigation financing.

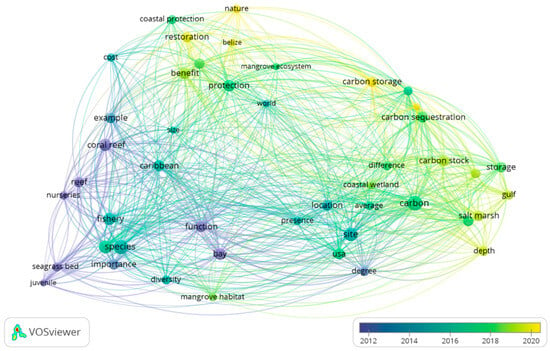

Figure 4 displays a VOSviewer Overlay Visualization of term co-occurrence in mangrove ecosystem service literature, color-coded by the average year of publication in which each term appeared. The color gradient, ranging from blue (earlier years, ~2012) to yellow (more recent, ~2020), highlights the temporal evolution of key research themes within the field.

Figure 4.

VOSviewer co-occurrence clustering with the mean year of publication as the color scheme. Clusters may overlap and contain multiple connections.

Earlier research (blue to green tones) focused heavily on biodiversity and habitat-related concepts, with terms such as “species,” “juvenile,” “reef,” “seagrass bed,” and “nurseries” indicating interest in the ecological functions of mangroves and their role in supporting fisheries and coral reef ecosystems. These studies often emphasized habitat connectivity, species development, and ecological diversity, particularly in relation to seagrass and coral reef systems.

In contrast, more recent publications (yellow shades) show a clear shift toward climate change mitigation and carbon-centered themes. Terms such as “carbon storage,” “carbon sequestration,” “carbon stock,” and “salt marsh” reflect the increasing importance of blue carbon and the role of coastal wetlands in global carbon accounting. This trend mirrors growing global policy and funding interest in nature-based solutions for climate resilience.

Several terms serve as bridging nodes across thematic and temporal domains. “Carbon” and “function” emerge as central connectors—“carbon” links studies on sequestration, climate benefits, and ecosystem valuation, while “function” connects ecological processes with service-based frameworks. Similarly, “mangrove habitat,” “coastal protection,” and “benefit” are highly connected, underscoring their cross-cutting relevance across biodiversity, risk reduction, and valuation studies.

Geographic terms such as “Caribbean,” “Gulf,” “Belize,” and “Mexico” also appear prominently, highlighting the regional focus of this literature. Their central placement suggests that tropical and subtropical coastal systems are primary case study areas in the field.

Finally, the presence of terms like “restoration,” “protection,” “cost,” and “value” reinforces the ecosystem service framing of recent research, linking ecological outcomes to economic and policy-relevant metrics. This reflects an evolving research landscape increasingly concerned with applied conservation, payment for ecosystem services, and the quantification of benefits in decision-making frameworks.

Table 2 illustrates how research themes have evolved over time—from early emphases on habitat diversity and species interactions to later priorities surrounding ecosystem service valuation, risk reduction, and climate mitigation. The transition from ecological to policy-relevant framing reflects an important disciplinary convergence and increasing relevance for decision-making in conservation, development, and climate finance contexts.

Table 2.

Temporal Clusters and Thematic Significance of Key Terms in Mangrove Ecosystem Services Literature.

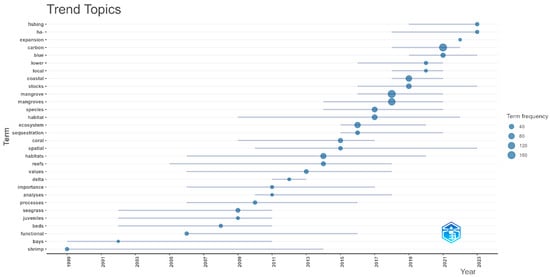

4.2. Analysis of Trend Topics

Figure 5 visualizes trending topics in mangrove ecosystem services research over time, illustrating both the temporal distribution and frequency of specific terms in the literature. Each horizontal bar represents the timespan during which a term was used, while bubble size indicates its frequency of occurrence—larger bubbles correspond to higher term usage. From this visualization, five major thematic insights emerge:

Figure 5.

Bibliometrix trend topics based on frequency and time period in which a term was found.

- Foundational Topics and Long-Term Focus: Core ecological and habitat-related terms such as “fishing,” “mangroves,” “habitat,” and “ecosystem” appear consistently across the entire time span, indicating a persistent foundational interest in these themes within marine and coastal research. These topics reflect long-standing concerns with biodiversity, habitat provisioning, and the ecological functions of mangrove systems.

- Emergence of Climate and Carbon-Centric Themes: Terms such as “carbon,” “sequestration,” and “blue” (as in “blue carbon”) show a marked rise in frequency in recent years, particularly from 2016 onward. This corresponds with the growing global recognition of nature-based solutions and the role of coastal ecosystems in carbon storage and climate mitigation. Their increased presence in the literature aligns with policy shifts (e.g., IPCC reports and NDC frameworks) that have prioritized ecosystem-based climate strategies.

- Expansion of Ecosystem Valuation and Sustainability Discourse: The appearance and growth of terms like “values,” “importance,” “functional,” and “stocks” reflect a conceptual shift toward ecosystem service valuation. These trends suggest that more recent research is not only concerned with ecological processes, but also with how those processes translate into measurable benefits—economically, socially, and climatologically. This mirrors the rising influence of valuation frameworks such as the TEEB and CICES in environmental policy and finance.

- Sustained Focus on Interconnected Ecosystems: Terms such as “seagrass,” “coral,” and “species” exhibit continuous and growing presence, underscoring an enduring focus on ecosystem connectivity and the biodiversity-supporting roles of mangroves. These ecosystems are increasingly viewed as part of integrated coastal–marine systems, with linkages to adjacent habitats and mutual reinforcement of ecological functions (e.g., fish nurseries and shoreline stabilization).

4.3. Analysis of Country Collaboration

Out of the 65 articles included in this study, 40 (61.5%) had American first authors. The United States also exhibited the highest rate of international collaboration, with most co-authored papers involving Australia or the United Kingdom (n = 4 each). Collaboration with Belize and Mexico occurred in three papers each, but there was no recorded co-authorship among Caribbean nations, apart from isolated instances involving Cuba, Panama, and Colombia.

It is important to note that this bibliometric analysis does not capture contributions from territories and protectorates (e.g., the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico), which may lead to an underestimation of intra-regional collaboration. This pattern underscores the need for more South–South cooperation and capacity-building initiatives to ensure that the scientific knowledge generated is reflective of local priorities, experiences, and ecological contexts.

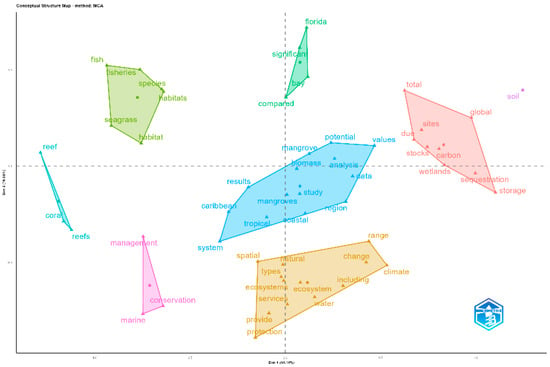

4.4. Factorial Analysis

This conceptual structure map, seen in Figure 6, was generated from a multiple correspondence factorial analysis (MCA), which clustered the 110 most common words found in study abstracts related to marine and coastal research. It visually organizes these terms into conceptual groups, which can be used to interpret thematic trends in research.

Figure 6.

Bibliometrix Factorial Analysis demonstrating seven distinct clusters that are color coded.

Dim 1 (x-axis) might represent a gradient from localized or ecosystem-specific studies (left) to global and ecosystem service-oriented studies (right). Clusters on the right reflect a broader, more global scope, while those on the left are more focused on specific species or habitats.

Dim 2 (y-axis) to reflect a spectrum from practical management and conservation (bottom) to ecological and biological processes (top). Clusters in the top half suggest a focus on ecological characteristics and biodiversity, while those in the bottom half emphasize conservation practices and ecosystem functions.

This conceptual structure supports a nuanced understanding of research diversity and helps categorize the current literature into the following thematic clusters:

Green Cluster (Top Left): Species and Habitat Focus: This cluster includes terms like “fish,” “species,” “habitats,” “seagrass,” and “fisheries,” suggesting a focus on species-specific studies and habitat characteristics. This grouping likely represents research on biodiversity and ecosystem structure, particularly in areas where species composition and habitat interactions are key.

Blue Cluster (Center Right): Mangrove Ecosystems and Regional Studies: Terms like “mangroves,” “tropical,” “Caribbean,” and “coastal” indicate a regional and ecosystem-specific focus, particularly on mangrove habitats in tropical and Caribbean regions. This cluster also includes terms like “potential,” “analysis,” and “data,” indicating a methodological focus on quantifying ecosystem services and understanding the ecological value of mangroves through empirical, data-driven approaches.

Red Cluster (Top Right): Global Carbon and Sequestration Themes: With terms such as “carbon,” “sequestration,” “storage,” “global,” “total,” and “wetlands,” this cluster corresponds to research at the interface of climate science and coastal ecosystem services. These studies address the global role of mangroves and wetlands in carbon cycling, with a strong policy relevance to blue carbon markets, national carbon inventories, and climate mitigation strategies.

Yellow Cluster (Bottom Right): Ecosystem Services and Climate Change: This cluster contains terms like “ecosystem,” “service,” “climate,” “change,” “spatial,” and “types,” pointing to research on ecosystem services and the impacts of climate change on these services. This grouping suggests an emphasis on spatial analysis, ecosystem function, and climate resilience in coastal environments.

Pink Cluster (Bottom Left): Marine Conservation and Management: Terms like “management,” “conservation,” and “marine” in this cluster suggest a focus on marine resource management and conservation strategies. This area likely represents studies centered on policies, practices, and frameworks for managing and conserving marine ecosystems.

Additional Terms and Outliers: Regional and Comparative Studies: Terms like “Florida,” “significant,” and “compared” are slightly detached from other clusters, suggesting a focus on regional studies (specifically Florida) and comparative analyses. This might indicate research comparing ecosystems or specific regions to assess ecological or environmental differences.

A Light Green Triangle includes three terms, “reef”, “reefs”, and “corals”, on the far left and centered. This is likely because studies in tropical climes that have reef systems often have corals growing on them. Conversely, most studies examining corals are looking at them on reefs as opposed to on mangroves’ prop roots or nearby seagrass beds. Coral can be found in both of these areas, but it appears that most studies about corals focus on them in reef systems.

A single Purple Outlier (“soil”) is spatially isolated, reflecting a niche research focus that may not be deeply integrated into mainstream mangrove ecosystem service literature but signals a potentially underexplored area (e.g., soil carbon dynamics or sedimentation processes).

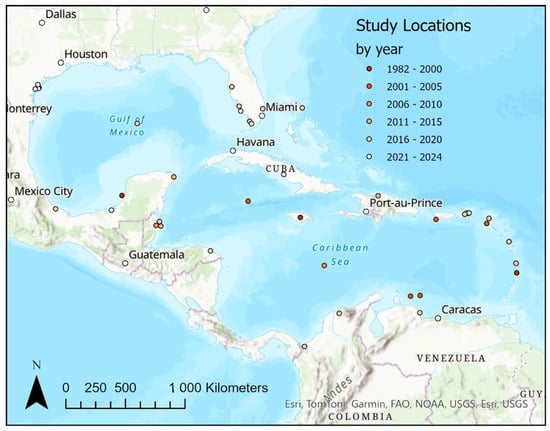

4.5. Optimized Hotspot Analysis

The 61 studies included in our analysis span 21 sovereign nations and U.S. states across the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico region (Figure 7). The majority of studies (n = 58) focused on a single geographic location, highlighting the localized nature of a large portion of mangrove ecosystem service research.

Figure 7.

Location of studies and years of publication.

Figure 7 also illustrates how the spatial distribution of study locations has shifted over time. More recent studies (2021–2024) are concentrated in the northern part of the region, particularly in Florida and Texas, while older studies (pre-2010) are more frequently located around the Yucatán Peninsula and the Eastern Caribbean. Venezuela is an exception, showing a mix of both earlier and more recent research. This northward shift in recent research activity is notable and suggests emerging research and funding priorities in the northern Gulf region.

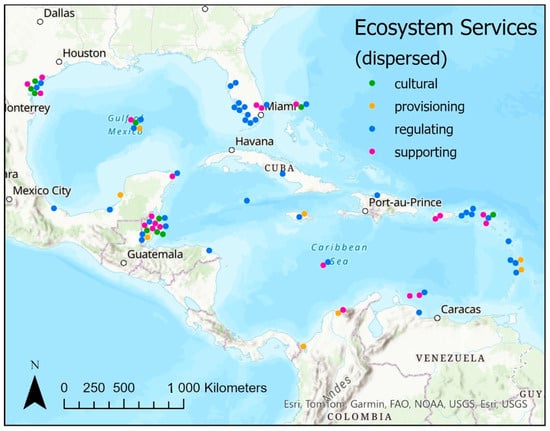

This trend is further clarified in Figure 8, which displays jittered points to prevent overlap and allow for the visualization of studies addressing multiple ecosystem services. In regions with predominantly newer studies—especially Florida and parts of the Gulf Coast—there is a noticeable emphasis on regulating services, particularly carbon sequestration, which has become a dominant research focus in the last decade.

Figure 8.

Location of studies on different ecosystem services. This figure has dispersed markers so that studies in the same location can still demonstrate all ecosystem services that they examined.

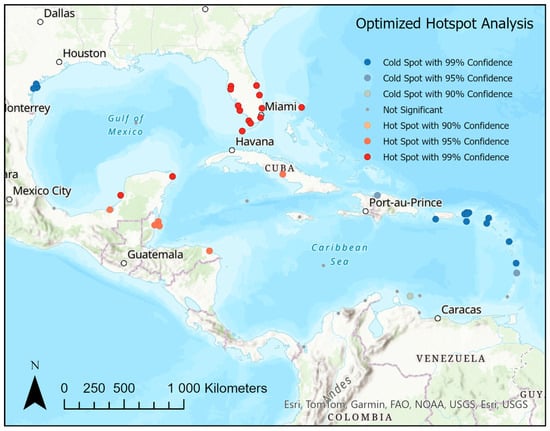

To assess spatial clustering, we conducted an Optimized Hotspot Analysis (OHS), shown in Figure 9. This analysis identifies regions with statistically significant concentrations of studies. Florida, Belize, Cuba, Guatemala, and the Yucatán Peninsula emerged as hotspots—areas with high densities of research. These regions not only feature frequent study activity but also tend to examine multiple types of ecosystem services, which likely contribute to their hotspot status. The concentration of research hotspots in Florida and Belize likely reflects the accessibility of long-term research infrastructure in these locations (e.g., U.S. universities and established field stations) compared to the logistical and funding challenges present in the ‘cold spot’ regions of the Eastern Caribbean.

Figure 9.

Optimized Hotspot Analysis demonstrating areas in the study area with the highest frequency of studies. Red signifies hot spots and blue symbolizes cold spots.

In contrast, the Eastern Caribbean appears as a cold spot, characterized by a lower density of studies and a narrow focus—typically on only one type of ecosystem service per study. This suggests a spatial research imbalance, where ecologically and socioeconomically important regions may be underrepresented in the current literature and deserve increased research attention.

4.6. Analysis of Ecosystem Services

Only one study in our dataset addressed all four major categories of ecosystem services—supporting, provisioning, regulating, and cultural. This study, “The impacts of mangrove range expansion on wetland ecosystem services in the southeastern United States: Current understanding, knowledge gaps, and emerging research needs” by Osland et al. (2022), underscores the rarity of integrated or convergence-focused research in the field [65]. The vast majority of studies (n = 54; 83%) examined only a single ecosystem service, indicating a fragmented approach to understanding mangrove multifunctionality.

Among those studies, regulating services were the most commonly addressed (n = 40), with a strong emphasis on carbon sequestration (n = 27). This suggests growing alignment with climate-focused research agendas and funding priorities, particularly those tied to blue carbon and nature-based solutions that are often monetized through carbon markets or mitigation finance. The dominance of regulating services (specifically carbon) in natural science journals reflects a ‘fundable’ priority. As funding agencies prioritize climate mitigation, research inevitably shifts toward quantifiable metrics like carbon stocks, potentially marginalizing cultural or subsistence services that are harder to monetize or publish in high-impact natural science journals.

Studies on supporting services (n = 25) were largely centered on the nursery function of mangroves for commercial fisheries (n = 19), highlighting their role in sustaining economically valuable fish populations. Similarly, studies on cultural services (n = 8) most frequently focused on tourism (n = 5), another economically significant dimension of coastal ecosystems.

In contrast, provisioning services (n = 9) received comparatively less attention and tended to emphasize subsistence fishing (n = 6), a service that is critical for local livelihoods but often lacks formal economic valuation. This imbalance suggests a tendency within the literature to prioritize ecosystem services with market or policy relevance, potentially at the expense of more localized, culturally embedded, or subsistence-based uses.

4.7. Analysis of Stakeholders

Stakeholder engagement was notably limited across the studies analyzed—only 11 out of 61 articles (18%) explicitly considered stakeholders in the context of mangrove ecosystem services. We considered studies with stakeholder engagement as those where a workshop or community participation was involved and specifically referenced in the final paper. Among these, the majority (n = 8) focused on cultural ecosystem services, and notably, every study examining cultural services included some form of stakeholder engagement [65,67,72,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105]. This reflects the inherently social and experiential nature of cultural services, which often depend on local perceptions, values, and practices for their identification and assessment.

Interestingly, only three of the eleven stakeholder-focused studies had a first author affiliated with the country or state under study [99,101,105]. This pattern may reflect a greater need for contextual understanding among foreign-led research teams. Alternatively, it could point to a possible underreporting or underemphasis of stakeholder engagement in studies led by local researchers, perhaps due to assumed familiarity or implicit knowledge that is not made explicit in the publication.

The studies that did engage stakeholders demonstrated a wide range of stakeholder types, including scientists, resource managers, government agencies, NGOs, and local community members. Several also engaged with non-institutional stakeholders such as fishers, birdwatchers, tourists, and other local residents, reflecting an effort to incorporate diverse, place-based knowledge systems into ecosystem service assessment and management [65,67,72,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105].

Overall, the limited number of studies incorporating stakeholder perspectives reveals a critical gap in the literature—particularly in light of increasing recognition that stakeholder inclusion is essential for effective ecosystem service valuation, scenario development, and the implementation of locally grounded, socially equitable nature-based solutions.

Our analysis underscores that mangrove conservation and restoration efforts are intrinsically linked to the interests and engagement of local communities, industries, and governments [85,106,107,108]. Incorporating a diverse range of stakeholder perspectives not only strengthens the legitimacy and effectiveness of conservation initiatives but also supports the sustainable management of the multiple ecosystem services that mangroves provide.

5. Discussion

This study unearthed knowledge gaps in terms of study site distribution, the type of ecosystem service studied, and the involvement of stakeholders. By using both a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis, we have been able to analyze these gaps in a scientifically rigorous fashion. Our main findings are indicative of a lack of convergence between different ecosystem services within a single study. Additionally, while stakeholders are more likely to be involved when the first author is based outside the country or region, there are still relatively few studies that involve the local community. It should be noted that our findings face a heavy bias of only including English-written articles, especially since the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean have many Spanish-speaking scientists. The restriction to English-language articles likely introduces a geographic bias. The ‘cold spots’ identified in Spanish-speaking regions of the Caribbean may not reflect a lack of local knowledge, but rather a barrier to international publication. This exclusion of non-English literature limits the integration of local ecological knowledge into global datasets.

While the 42% international co-authorship rate suggests high global interest, the data reveals a pattern of ‘parachute science.’ With 61.5% of studies led by U.S. authors and limited first-authorship from Caribbean nations, there is a risk that research agendas are being set by Global North priorities (e.g., carbon markets) rather than local necessities (e.g., coastal protection or food security). This imbalance suggests that despite high ‘collaboration’ metrics, genuine capacity building and equitable scientific exchange remain underdeveloped.

Because of the historical focus on dollar valuation, there is a lack of studies that focus on the priorities of both scientists and local stakeholders regarding the holistic valuation of ecosystem services. In this study, we examine not only the existing literature on the ecosystem services provided by mangroves but also changes in the trends of priorities for mangrove services. We hypothesized that (1) older studies will focus more on the provisioning services to fisheries and the supporting services of nurseries; (2) newer studies will focus on regulating services of carbon sequestration; (3) cultural services will be underrepresented in the literature due to a perceived lack of scientific value at this intersection with social sciences; (4) stakeholder engagement will be underrepresented or not present in the majority of studies; and (5) convergence of ecosystem services and the ensuing trade-offs between them will be largely ignored by most studies. Finally, we want to examine where these studies are taking place to determine biases caused by the larger context of these study locations. The limited inclusion of stakeholders (18%) raises concerns regarding environmental justice. When valuation studies exclude local users—particularly regarding provisioning services like subsistence fishing—management policies derived from this data may inadvertently criminalize local livelihoods in favor of global carbon goals. This ‘top-down’ valuation risks creating ‘paper parks’ that lack community buy-in.

The Bibliometrix trend topic analysis unearthed an evolving focus in marine and coastal research, from foundational studies on habitat and species to a more recent emphasis on ecosystem services, carbon sequestration, and spatial analysis. This trend aligns with global environmental priorities around climate change, biodiversity, and sustainable use of natural resources. Essentially, as climate change and carbon sequestration have garnered more media attention and more financial backing, there has been an increase in these studies. Likewise, there has been a decrease in studies on fisheries as the international fishing market has begun to deteriorate and collapse.

Relatedly, the VOSviewer temporal term visualization illustrates the progression of marine and coastal research from biodiversity and habitat-specific studies in earlier years (2012–2015) toward an emphasis on climate mitigation and carbon storage functions in later years (2018–2020). It highlights key themes like species protection, ecosystem services, and carbon sequestration, with a particular focus on the protective and climate-regulating benefits of coastal ecosystems like mangroves, seagrass beds, and salt marshes. The clustering of terms and the color-coded timeline provide a clear picture of the field’s evolving priorities, shaped by increasing concerns over climate change and ecosystem sustainability.

These shifts denote the changing priorities of scientific researchers and their funders within the last decade and a half. Studies of ecosystem services in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean that examine mangroves have historically lacked convergence. That is, different aspects of ecosystem services are examined separately instead of being viewed holistically to create a full picture of the relationship between humans and the forests around them.

Only four studies referenced mangroves as a form of nature-based solutions in their abstracts [44,69,108,109]. All four of these studies were released in the last five years, and most focus on carbon sequestration, with one focused on flooding. This suggests that authors are viewing nature-based solutions through a very narrow lens that focuses almost exclusively and explicitly on mangroves’ relationship to the climate crisis.

The additives and non-linear relationships of ecosystem services are crucial in understanding and evaluating preservation and restoration approaches. For example, Arkema et al., 2015, examined the tradeoffs related to coastal protection, supporting the lobster fishery, and tourism in coastal systems, including mangroves [97]. They even used stakeholder engagement to develop potential management plans [97]. By pursuing more studies like this, the field would evolve to consider a diversity of views and expand scientific understanding. In addition, many of the existing studies are relatively small in scale and provide few avenues for broader generalization.

It is challenging to determine the effects that involving stakeholders has on the implementation of adequate protection and restoration of mangroves and their associated services due to a lack of follow-up studies. This can largely be attributed to the lack of funding for long-range studies to examine how involvement of the local community can tie into meeting environmental and sustainable goals. However, even without these return studies, social scientists have repeatedly demonstrated that local involvement, even if not producing tangible results, produces important social changes in valuation. As ecosystem service valuation is both an aspect of supply and demand, this increase in demand from local people should not be ignored.

By not including local stakeholders and the additionality of multiple ecosystem services, these studies have missed much of the importance of understanding mangrove ecosystem services for their protection and conservation. Scientists must be more astute in consulting with local policymakers and peoples in order to provide accurate assessments that may result in meaningful changes in policy and law. That is, without local input, no findings can be properly implemented in order to protect mangroves and their associated ecosystem services.

6. Conclusions

Our review highlights several vital gaps in the current body of work. First, there is minimal convergence between the social sciences and biological sciences in this region of interest, resulting in fragmented perspectives and missed opportunities for interdisciplinary synthesis. Second, many of the existing studies are relatively small in scale and provide few avenues for broader generalization. Third, while anthropological research has placed commendable emphasis on local stakeholders, similar attention has not been sufficiently integrated into ecological studies, leading to an imbalance in how stakeholder perspectives are represented across disciplines.

Mangroves not only work as a form of climate mitigation but also as adaptation and—often overlooked—an important cultural tie to the surrounding community. Evaluating ecosystem services in a holistic manner and including stakeholders in the process leads to effective use of Nature-based Solutions. The articles examined herein create an excellent structure and stepping stone for the convergent studies that make up the future of ecosystem services in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.-F. and S.G.; methodology, M.K.-F.; formal analysis, M.K.-F., E.S. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.-F.; writing—review and editing, M.K.-F., S.G. and M.K.; supervision, S.G. and L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, grant number 2209284.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESVD | Ecosystem Services Valuation Database |

| CICES | Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services |

| TEEB | Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity |

| MCA | Multiple Correspondence Analysis |

| OHS | Optimized Hotspot Analysis |

References

- Kathiresan, K.; Bingham, B.L. Biology of Mangroves and Mangrove Ecosystems. In Advances in Marine Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; Volume 40, pp. 81–251. [Google Scholar]

- Rützler, K.; Feller, I.C. Mangrove Swamp Communities: An Approach in Belize. Ecosistemas De Mangl. En América Trop. 1999, 30, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Branoff, B.L. Quantifying the Influence of Urban Land Use on Mangrove Biology and Ecology: A Meta-Analysis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017, 26, 1339–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A.M.; Farnsworth, E.J. Anthropogenic Disturbance of Caribbean Mangrove Ecosystems: Past Impacts, Present Trends, and Future Predictions. Biotropica 1996, 28, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.S.; Kenworthy, W.J.; Wood, L.L. Ontogenetic Patterns of Concentration Indicate Lagoon Nurseries Are Essential to Common Grunts Stocks in a Puerto Rican Bay. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2009, 81, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, B.; Mumford, P.L.; Robblee, M.B. Stable Isotope Studies of Pink Shrimp (Farfantepenaeus Duorarum Burkenroad) Migrations on the Southwestern Florida Shelf. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1999, 65, 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Nagelkerken, I.; Roberts, C.M.; van der Velde, G.; Dorenbosch, M.; van Riel, M.C.; de la Morinière, E.C.; Nienhuis, P.H. How Important Are Mangroves and Seagrass Beds for Coral-Reef Fish? The Nursery Hypothesis Tested on an Island Scale. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002, 244, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhomia, R.K.; Kauffman, J.B.; McFadden, T.N. Ecosystem Carbon Stocks of Mangrove Forests along the Pacific and Caribbean Coasts of Honduras. Wetl. Ecol Manag. 2016, 24, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt, J.L.; Smoak, J.M.; Smith, T.J., III; Sanders, C.J. Temporal Variability of Carbon and Nutrient Burial, Sediment Accretion, and Mass Accumulation over the Past Century in a Carbonate Platform Mangrove Forest of the Florida Everglades. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2014, 119, 2032–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbert, D. Hurricane Disturbance and Forest Dynamics in East Caribbean Mangroves. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radabaugh, K.R.; Moyer, R.P.; Chappel, A.R.; Powell, C.E.; Bociu, I.; Clark, B.C.; Smoak, J.M. Coastal Blue Carbon Assessment of Mangroves, Salt Marshes, and Salt Barrens in Tampa Bay, Florida, USA. Estuaries Coasts 2018, 41, 1496–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Using Ecosystem Services in Decision-Making to Support Sustainable Development: Critiques, Model Development, a Case Study, and Perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 548–549, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunton, R.M.; van Asperen, E.N.; Basden, A.; Bookless, D.; Araya, Y.; Hanson, D.R.; Goddard, M.A.; Otieno, G.; Jones, G.O. Beyond Ecosystem Services: Valuing the Invaluable. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröter, M.; van der Zanden, E.H.; van Oudenhoven, A.P.E.; Remme, R.P.; Serna-Chavez, H.M.; de Groot, R.S.; Opdam, P. Ecosystem Services as a Contested Concept: A Synthesis of Critique and Counter-Arguments. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, G.; Pascual, U. Cost-Benefit Analysis in the Context of Ecosystem Services for Human Well-Being: A Multidisciplinary Critique. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, M.P.A.; Stevenson, H.; Meadowcroft, J. Debating Nature’s Value: Epistemic Strategy and Struggle in the Story of ‘Ecosystem Services’. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2019, 21, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Ruiz-Pérez, M. Economic Valuation and the Commodification of Ecosystem Services. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2011, 35, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badura, T.; Kettunen, M. Regulating Services and Related Goods. In Social and Economic Benefits of Protected Areas; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-203-09534-8. [Google Scholar]

- Alemu, I.J.B.; Richards, D.R.; Gaw, L.Y.-F.; Masoudi, M.; Nathan, Y.; Friess, D.A. Identifying Spatial Patterns and Interactions among Multiple Ecosystem Services in an Urban Mangrove Landscape. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, H.L.; Granek, E.F. Coastal Sediment Elevation Change Following Anthropogenic Mangrove Clearing. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 165, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazda, Y.; Magi, M.; Nanao, H.; Kogo, M.; Miyagi, T.; Kanazawa, N.; Kobashi, D. Coastal Erosion Due to Long-Term Human Impact on Mangrove Forests. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, K.L.; Vervaeke, W.C. Impacts of Human Disturbance on Soil Erosion Potential and Habitat Stability of Mangrove-Dominated Islands in the Pelican Cays and Twin Cays Ranges, Belize. Smithson. Contrib. Mar. Sci. 2009, 38. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233727446_Impacts_of_human_disturbance_on_soil_erosion_and_habitat_stability_of_mangrove-dominated_islands_in_the_Pelican_Cays_and_Twin_Cays_ranges_Belize (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Rangel-Buitrago, N.G.; Anfuso, G.; Williams, A.T. Coastal Erosion along the Caribbean Coast of Colombia: Magnitudes, Causes and Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 114, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villate Daza, D.A.; Sánchez Moreno, H.; Portz, L.; Portantiolo Manzolli, R.; Bolívar-Anillo, H.J.; Anfuso, G. Mangrove Forests Evolution and Threats in the Caribbean Sea of Colombia. Water 2020, 12, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan-Brown, D.N.; Connolly, R.M.; Richards, D.R.; Adame, F.; Friess, D.A.; Brown, C.J. Global Trends in Mangrove Forest Fragmentation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flowers, B.; Huang, K.-T.; Aldana, G.O. Analysis of the Habitat Fragmentation of Ecosystems in Belize Using Landscape Metrics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.; van Oort, B.; Romstad, B. What We Have Lost and Cannot Become: Societal Outcomes of Coastal Erosion in Southern Belize. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Shen, J.; Rhome, J.; Smith, T.J. The Role of Mangroves in Attenuating Storm Surges. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2012, 102–103, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankespoor, B.; Dasgupta, S.; Lange, G.-M. Mangroves as a Protection from Storm Surges in a Changing Climate. Ambio 2017, 46, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.M.; Bryan, K.R.; Mullarney, J.C.; Horstman, E.M. Attenuation of Storm Surges by Coastal Mangroves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 2680–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.A.; Wilson Grimes, K.; Reeve, A.S.; Platenberg, R. Mangroves Buffer Marine Protected Area from Impacts of Bovoni Landfill, St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands. Wetl. Ecol Manag. 2017, 25, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Ordóñez, O.; Castillo-Olaya, V.A.; Granados-Briceño, A.F.; Blandón García, L.M.; Espinosa Díaz, L.F. Marine Litter and Microplastic Pollution on Mangrove Soils of the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta, Colombian Caribbean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 145, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Ordóñez, O.; Saldarriaga-Vélez, J.F.; Espinosa-Díaz, L.F. Marine Litter Pollution in Mangrove Forests from Providencia and Santa Catalina Islands, after Hurricane IOTA Path in the Colombian Caribbean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeruttun, L.D.; Raghbor, P.; Appadoo, C. First Assessment of Anthropogenic Marine Debris in Mangrove Forests of Mauritius, a Small Oceanic Island. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 164, 112019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.Y.; Not, C.; Cannicci, S. Mangroves as Unique but Understudied Traps for Anthropogenic Marine Debris: A Review of Present Information and the Way Forward. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 271, 116291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, K.W.; Doyle, T.W.; Twilley, R.R.; Smith, T.J., III; Whelan, K.R.T.; Sullivan, J.K. Woody Debris in the Mangrove Forests of South Florida1. Biotropica 2005, 37, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubit, J.D.; Getter, C.D.; Jackson, J.B.C.; Garrity, S.D.; Caffey, H.M.; Thompson, R.C.; Weil, E.; Marshall, M.J. An Oil Spill Affecting Coral Reefs And Mangroves On The Caribbean Coast Of Panama. Int. Oil Spill Conf. Proc. 1987, 1987, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Asmath, H.; Chee, C.L.; Darsan, J. Potential Oil Spill Risk from Shipping and the Implications for Management in the Caribbean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 93, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Rubí, J.R.; Luna-Acosta, A.; Etxebarría, N.; Soto, M.; Espinoza, F.; Ahrens, M.J.; Marigómez, I. Chemical Contamination Assessment in Mangrove-Lined Caribbean Coastal Systems Using the Oyster Crassostrea Rhizophorae as Biomonitor Species. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 13396–13415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillardat, P.; Friess, D.A.; Lupascu, M. Mangrove Blue Carbon Strategies for Climate Change Mitigation Are Most Effective at the National Scale. Biol. Lett. 2018, 14, 20180251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alongi, D.M. Global Significance of Mangrove Blue Carbon in Climate Change Mitigation. Science 2020, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macreadie, P.I.; Anton, A.; Raven, J.A.; Beaumont, N.; Connolly, R.M.; Friess, D.A.; Kelleway, J.J.; Kennedy, H.; Kuwae, T.; Lavery, P.S.; et al. The Future of Blue Carbon Science. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macreadie, P.I.; Costa, M.D.P.; Atwood, T.B.; Friess, D.A.; Kelleway, J.J.; Kennedy, H.; Lovelock, C.E.; Serrano, O.; Duarte, C.M. Blue Carbon as a Natural Climate Solution. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissette, H.K.; Baez, S.K.; Beers, L.; Bood, N.; Martinez, N.D.; Novelo, K.; Andrews, G.; Balan, L.; Beers, C.S.; Betancourt, S.A.; et al. Belize Blue Carbon: Establishing a National Carbon Stock Estimate for Mangrove Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 870, 161829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidik, F.; Lawrence, A.; Wagey, T.; Zamzani, F.; Lovelock, C.E. Blue Carbon: A New Paradigm of Mangrove Conservation and Management in Indonesia. Mar. Policy 2023, 147, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Silveira, J.A.; Pech-Cardenas, M.A.; Morales-Ojeda, S.M.; Cinco-Castro, S.; Camacho-Rico, A.; Sosa, J.P.C.; Mendoza-Martinez, J.E.; Pech-Poot, E.Y.; Montero, J.; Teutli-Hernandez, C. Blue Carbon of Mexico, Carbon Stocks and Fluxes: A Systematic Review. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedjo, R.; Sohngen, B. Carbon Sequestration in Forests and Soils. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2012, 4, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, K.W.; Lovelock, C.E.; McKee, K.L.; López-Hoffman, L.; Ewe, S.M.L.; Sousa, W.P. Environmental Drivers in Mangrove Establishment and Early Development: A Review. Aquat. Bot. 2008, 89, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, J.C. Factors Influencing Mangrove Ecosystems. In Mangroves: Ecology, Biodiversity and Management; Rastogi, R.P., Phulwaria, M., Gupta, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 97–115. ISBN 978-981-16-2494-0. [Google Scholar]

- Reef, R.; Feller, I.C.; Lovelock, C.E. Nutrition of Mangroves. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 1148–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumby, P.J.; Edwards, A.J.; Ernesto Arias-González, J.; Lindeman, K.C.; Blackwell, P.G.; Gall, A.; Gorczynska, M.I.; Harborne, A.R.; Pescod, C.L.; Renken, H.; et al. Mangroves Enhance the Biomass of Coral Reef Fish Communities in the Caribbean. Nature 2004, 427, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloslavich, P.; Díaz, J.M.; Klein, E.; Alvarado, J.J.; Díaz, C.; Gobin, J.; Escobar-Briones, E.; Cruz-Motta, J.J.; Weil, E.; Cortés, J.; et al. Marine Biodiversity in the Caribbean: Regional Estimates and Distribution Patterns. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, V.P.; Ranjan, R.; Singh, J.S. Human–Mangrove Conflicts: The Way Out. Curr. Sci. 2002, 83, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar]