Abstract

To address the low trajectory tracking accuracy and limited robustness of conventional reinforcement learning algorithms under complex marine environments involving wind, wave, and current disturbances, this study proposes a proximal policy optimization (PPO) algorithm incorporating an intrinsic curiosity mechanism to solve the unmanned surface vehicle (USV) trajectory tracking control problem. The proposed approach is developed on the basis of a three-degree-of-freedom (3-DOF) USV model and formulated within a Markov decision process (MDP) framework, where a multidimensional state space and a continuous action space are defined, and a multi-objective composite reward function is designed. By incorporating a pure pursuit guidance algorithm, the complexity of engineering implementation is reduced. Furthermore, an improved PPO algorithm integrated with an intrinsic curiosity mechanism is adopted as the trajectory tracking controller, in which the exploration incentives provided by the intrinsic curiosity module (ICM) guide the agent to explore the state space efficiently and converge rapidly to an optimal control policy. The final experimental results indicate that, compared with the conventional PPO algorithm, the improved PPO–ICM controller achieves a reduction of 54.2% in average lateral error and 47.1% in average heading error under simple trajectory conditions. Under the complex trajectory condition, the average lateral error and average heading error are reduced by 91.8% and 41.9%, respectively. These results effectively demonstrate that the proposed PPO–ICM algorithm attains high tracking accuracy and strong generalization capability across different trajectory scenarios, and can provide a valuable reference for the application of intelligent control algorithms in the USV domain.

1. Introduction

With the surging demand in marine resource exploitation, ocean surveying, emergency rescue, and intelligent shipping, unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) have shown tremendous potential in the field of ocean exploration [1,2]. Owing to their advantages of low cost, high safety, and flexible maneuverability, USVs have emerged as an important component of marine unmanned systems. Trajectory tracking control, as a key technology enabling autonomous navigation of USVs, directly determines whether a vehicle can accurately accomplish predefined missions in complex maritime environments. Although most commercially available USVs are equipped with trajectory tracking capabilities and can dynamically adjust their heading based on predefined routes, achieving high-precision and robust trajectory tracking under the combined effects of multi-source uncertainties such as wind, waves, and currents remains a major challenge in the field of USV autonomous navigation [3,4,5].

Throughout the development of USV control technologies, traditional control methods have provided a solid theoretical foundation for addressing trajectory tracking problems. In earlier studies, Minorsky was the first to apply the concept of feedback control to the design of autonomous ship navigation systems, laying the theoretical foundation for the application of Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controllers [6]. Other studies introduced sliding mode control [7,8], leveraging its excellent control performance for nonlinear systems to improve control accuracy and stability while avoiding the parameter tuning process. This method requires low model accuracy but can lead to chattering phenomena during operation. Subsequently, researchers have carried out a lot of improvement work around the traditional control methods. For example, Li et al. integrated neural networks with traditional PID control and proposed an adaptive PID control system [9], eliminating the cumbersome parameter tuning process inherent in traditional PID control. Meng et al. applied the fusion method of global sliding mode control and adaptive neural networks for underactuated USVs, effectively reducing the occurrence of chattering and enhancing the controller’s robustness against disturbances [10]. Valencia-Palomo et al. addressed the suboptimality of the feed-forward compensator in simple Model Predictive Control (MPC) algorithms by proposing improvement ideas and simple methods for the feed-forward compensator to achieve a more systematic and optimal design. Their study showed that the optimal design process depends on the underlying loop tuning, and that there are underutilized potential advantages in constraint handling procedures which can enhance the computational efficiency of online controller implementation. The study also verified the effectiveness of the proposed scheme through laboratory hardware tests on a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) [11].

In addition to traditional control methods, the integration of guidance algorithms with control strategies has gradually become a research focus. By appropriately designing and applying guidance laws, the complexity of traditional controller design can be reduced to a certain extent, while the tracking accuracy of the system under external disturbances can be effectively improved. For example, Alejandro et al. combined the Line-of-Sight (LOS) guidance law with adaptive sliding mode control, improving the robustness of adaptive controllers in the face of environmental disturbances [12]. Wu et al. introduced an improved extended state observer-based LOS guidance algorithm, achieving fast and accurate calculation of time-varying side slip angles, ensuring high-precision path tracking even under external disturbances [13]. In 2024, Yu et al. proposed a prescribed-time extended state observer (PTESO) guidance law, which accurately solves the side slip angle of USVs and provides real-time compensation for time-varying ocean disturbances [14]. In other research fields, Shao et al. proposed a robust dynamic surface trajectory tracking controller based on the extended state observer (ESO) for the trajectory tracking problem of quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) subject to parametric uncertainties and external disturbances. The study incorporated the dynamic surface control technique to address the inherent explosion of complexity issue in backstepping control, ensuring asymptotic tracking performance in the presence of disturbances [15].

However, in real and complex marine environments, traditional PID control, sliding mode control, and their improved variants still suffer from several inherent limitations. On the one hand, these methods have difficulty effectively adapting to the dynamic characteristics of the environment, and their control performance often relies on cumbersome parameter tuning procedures, while lacking autonomous learning capability. On the other hand, some hybrid adaptive control algorithms exhibit relatively complex structures and high computational burdens, which restrict their practical application in real-world engineering systems [16,17].

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence technologies, machine learning methods have attracted widespread attention in the field of intelligent control [18]. Among these approaches, deep reinforcement learning (DRL), owing to its strong adaptability and reduced reliance on accurate mathematical models, provides a promising alternative for addressing the control of complex nonlinear systems such as USVs. In 2019, Woo et al. applied the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm to USV control, providing a new perspective for autonomous navigation under complex environments [19]. Magalhães et al. developed a Q-learning based adaptive control scheme and applied it to an autonomous biomimetic underwater robot [20], offering mature theoretical support for subsequent full-scale experiments. Subsequently, some researchers have focused on improving baseline DRL algorithms by integrating them with traditional control methods and guidance algorithms, thereby further enhancing policy performance in complex environments. For example, Wang et al. proposed an improved DDPG-based method for optimizing PID parameters, which effectively enhanced the disturbance-rejection capability of PID controllers [21]. Cui et al. presented a path-following control method for single-outboard USVs that integrates DDPG with Model Predictive Control (MPC). Experimental comparisons verified the feasibility and effectiveness of the algorithm and improved the path-following performance of single-outboard USVs [22]. Zheng et al. adopted a guidance-based control framework and developed a Linear Active Disturbance Rejection Controller (LADRC). By integrating the decision-making mechanism of reinforcement learning into the controller design, they proposed an LADRC control strategy based on the Soft Actor–Critic (SAC) algorithm. This method enables adaptive path tracking control for USVs [23]. Guan et al. proposed an adaptive PID controller for USV trajectory control based on the SAC algorithm. By combining the SAC algorithm with the PID controller, this approach effectively mitigates the interpretability and safety issues commonly associated with traditional DRL algorithms [24]. Zhao et al. proposed a smooth-convergent deep reinforcement learning (SCDRL) approach, based on deep Q-networks (DQN) and reinforcement learning, for the path tracking of underactuated USVs. Experimental results indicate that the SCDRL method achieves smoother convergence compared to traditional deep Q-learning, maintains path tracking errors comparable to existing approaches, and demonstrates good practicality and generalizability [25]. Li et al. proposed a model-free Stable Adversarial Inverse Reinforcement Learning (SAIRL) algorithm to address the challenge of path following for Marine Surface Vessels (MSVs) in adverse environments and the difficulty of designing effective reward functions for Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)-based path following tasks. Utilizing only MSV state information, the algorithm reconstructs the reward function from expert demonstrations and adopts an alternative loss function combined with a dual-discriminator framework to resolve the policy collapse caused by the vanishing gradient of the discriminator, ensuring the preset tracking accuracy and training stability [26].

In summary, although DRL algorithms possess autonomous exploration and decision-making capabilities and do not rely on highly precise mathematical models, making them particularly suitable for complex nonlinear systems such as USVs, and despite the considerable progress achieved in this area, existing DRL-based methods for USV trajectory tracking still exhibit certain limitations [27,28]: first, some approaches rely on complex integrated guidance–control architectures or multi-algorithm fusion designs, which not only increase the overall system design and parameter tuning complexity but also pose challenges for the practical implementation and deployment of the algorithms; secondly, algorithms such as DDPG and SAC are highly sensitive to hyperparameters and prone to slow convergence or oscillatory behavior during training, which reduces robustness and leads to increased training costs and prolonged development cycles.

Based on the above analysis, this study adopts an improved proximal policy optimization (PPO) control approach for USV trajectory tracking in complex marine environments, leveraging the USV’s kinematic and dynamic models. The method incorporates an intrinsic curiosity mechanism to enhance the agent’s exploration ability and training stability, and employs a pure pursuit guidance algorithm to reduce parameter complexity at the guidance level, thus improving both engineering feasibility and robustness. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

- A three-degree-of-freedom (3-DOF) model is constructed for a twin-hull USV, considering external disturbances from wind, waves, and currents. A pure pursuit guidance algorithm is adopted to reduce algorithmic complexity while maintaining tracking accuracy and improving overall tracking performance, providing a reliable solution for subsequent in-depth studies of engineering application deployment.

- (2)

- An improved PPO algorithm is proposed by integrating the intrinsic curiosity mechanism. The enhanced PPO algorithm exhibits more stable training behavior and encourages the agent to actively explore unknown states, thereby providing stronger robustness in complex marine environments.

- (3)

- Comparative experiments are designed for both simple and complex trajectory scenarios to evaluate the effectiveness and generalization capability of the proposed PPO-ICM algorithm.

Existing studies indicate that the PPO-ICM algorithm achieves high-accuracy trajectory tracking while satisfying the requirements for practical deployment. The computational complexity of the algorithm is controllable and does not rely on high-performance computing platforms, making it suitable for implementation on the embedded hardware systems of USVs. Moreover, the total training time of the algorithm is 2481.36 s, which ensures the efficiency of model training while meeting the real-time control requirements of USV experiments, demonstrating favorable engineering applicability and deployability.

2. USV Modeling and Guidance Algorithms

2.1. 3-Degree-of-Freedom Ship Motion Model

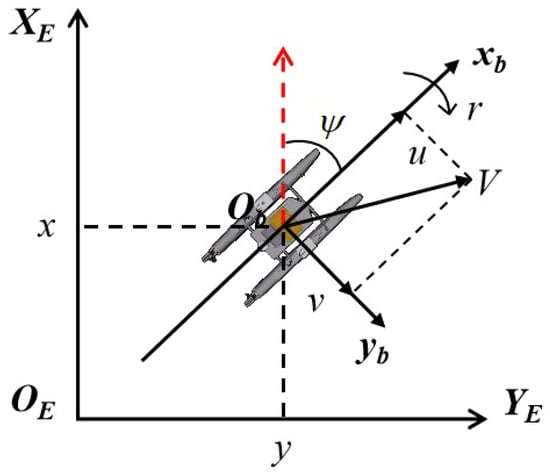

The mathematical modeling of ships forms the foundation of research on marine motion control and is widely employed in the design of ship control systems [29,30]. The motion of a USV is typically described using two orthogonal coordinate systems: the north-east-down (NED) inertial reference frame and the body-fixed coordinate frame. The NED frame is commonly used for navigation and motion representation. It defines the USV’s current location as the origin, with its three axes oriented toward geographic north, geographic east, and the Earth’s center, thereby forming a right-handed spatial reference system. This coordinate system is generally adopted to describe the absolute position and attitude of a USV. The body-fixed frame, whose origin is typically located at the USV’s center of mass, moves and rotates together with the vehicle. Its axes vary with the USV’s motion and are directly associated with the vehicle’s dynamics and propulsion system. Therefore, it is commonly used to represent the motion states of the USV.

The motion of a ship in a marine environment consists of 6-degrees-of-freedom (6-DOF), namely surge, sway, heave, roll, pitch, and yaw. For conventional USVs, the motion control problem is typically considered within the two-dimensional horizontal plane. Therefore, the effects of heave, roll, and pitch can be neglected, and the 6-DOF motion model of the USV can be simplified to a 3-DOF model that includes surge, sway, and yaw. The kinematic model of the USV in the horizontal plane is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Kinematic model of the USV.

The simplified three-degree-of-freedom kinematic equations of the USV are shown in Equation (1):

in this equation, represent the position coordinates and heading angle of the USV in the NED coordinate system; represent the surge velocity, sway velocity, and yaw rate of the USV in the body-fixed coordinate system, respectively. represents the transformation matrix from the NED coordinate system to the body-fixed coordinate system, which is given by Equation (2).

The dynamics model of a USV is a mathematical representation that describes the relationship between the external forces acting on the USV and its motion state changes. Based on Newton’s second law, it incorporates the hydrodynamic characteristics of the USV, the propulsion system characteristics, and environmental disturbances, revealing the underlying principles governing the conversion from force to motion. The 3-DOF dynamic model of the USV is given by Equation (3):

where m is the mass of the twin-hull USV, mx and my are the added masses in the surge and sway directions, respectively. Izz is the moment of inertia of the USV about its center of gravity, and Jzz denotes the added moment of inertia in the yaw direction. Due to the relatively low mass and small hull dimensions of the catamaran USV considered in this study, the mass distribution is comparatively concentrated, resulting in a small rigid-body yaw moment of inertia. Consequently, the added yaw moment of inertia Jzz plays a dominant role, and the effect of the rigid-body moment of inertia Izz can be neglected in the dynamic modeling. X, Y, N represent the longitudinal force, lateral force, and yawing moment acting on the USV, respectively, as given by Equation (4):

where the subscripts τ, d, wind, wave and current represent the thrust force, hydrodynamic damping force, and disturbances from wind, waves, and currents acting on the USV.

The thrust forces from the left and right propellers of the twin-hull USV are combined to yield the resultant force in the surge direction and the resultant moment in the yaw direction, as represented by Equation (5):

where Fleft and Fright represent the thrust forces of the left and right propellers of the USV. The thrust forces along the longitudinal axis are combined to provide the total longitudinal thrust. B denotes the lateral distance between the two propellers of the USV, also referred to as the USV’s beam. The difference in thrust generates a yawing moment, enabling the USV to perform turning maneuvers, with counterclockwise rotation considered positive.

The primary resistance encountered by the USV during motion arises from hydrodynamic damping forces. Ignoring the effects of nonlinear damping, the linear damping model is represented by Equation (6):

where Xu, Yv, Nr is the linear damping coefficient, which represents the damping characteristics of the USV in different motion directions, and can be obtained through tank tests or numerical simulations.

In addition, the models for the disturbances caused by wind, waves, and currents acting on the USV during its motion are given by Equations (7)–(9).

where ρa is the air density, Vwind is the relative wind speed, and L, B, d represent the length, beam, and draft of the USV. Their product represents the projected frontal and side areas of the USV above the waterline. CX,wind, CY,wind are the wind force coefficients in the surge and sway directions, CN,wind is the wind moment coefficient in the yaw direction. βwind represents the windward angle.

The wave disturbance is modeled using a first-order regular wave model [31], where periodic phase changes simulate the dynamic perturbations of waves on the twin-hull USV. ρw is the seawater density, Hs is the significant wave height, and φ is the wave phase that dynamically varies with time and the position of the USV. CX,wave, CY,wave, CN,wave are the wave force coefficients in the surge, sway, and yaw directions.

The current disturbance is modeled based on a constant uniform flow, where the relative motion between the USV and the current is obtained through coordinate system transformation. In the above equation, Vc is the relative velocity between the USV and the current, βc is the drift angle, CX,current, CY,current, CN,current are the current force coefficients in the surge, sway, and yaw directions.

In summary, to systematically characterize the dynamic properties of the USV, the key parameters of the 3-DOF model, including the mass matrix, added mass terms, and damping coefficient matrix are summarized, with their specific values listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

USV’s dynamics parameters.

2.2. Pure Pursuit Guidance

In the field of trajectory tracking for USVs, guidance algorithms serve as a crucial link between the target trajectory and the control system. During the guidance process, the guidance module continuously determines the relative position between the USV and the desired trajectory and transmits this information to the control system to regulate the USV’s motion. Among various guidance methods, the Pure Pursuit algorithm is one of the most widely used. Originally developed for mobile robotics, it has been increasingly adopted in USV trajectory tracking due to its simple logic, fast computational efficiency, and strong robustness.

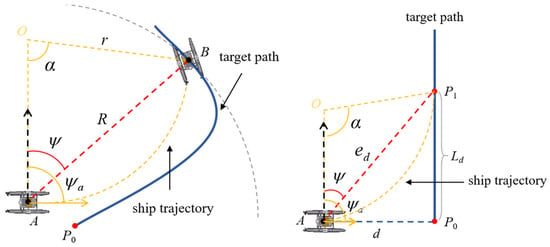

The schematic diagram of the pure pursuit guidance algorithm is shown in Figure 2. The core idea of this method is to convert the trajectory-tracking problem into a heading-control problem by utilizing the geometric relationship between the current position of the USV and a designated look-ahead point. Taking the current position A(xa, ya) of the USV as the origin, a circle with radius R (the look-ahead distance) is drawn. The intersection between this circle and the reference trajectory is then selected as the look-ahead point B(xb, yb) at the current time. α represents twice the heading deviation angle and can be expressed as α = 2(ψa − ψ). r denotes the turning radius of the USV, and its calculation is given by Equation (10):

the circular arc AB corresponding to the look-ahead distance R represents the dynamically adjusted path required for the USV to track the target point B. The tangent direction of the USV’s position on this arc defines its instantaneous heading angle, denoted as ψa, the angle between the look-ahead line and the geographic north direction is defined as the desired heading angle ψ. The algorithm uses the USV’s real-time position, heading angle, and other state information as the basis. According to the predefined look-ahead distance, a unique look-ahead point is selected from the target trajectory composed of n discrete waypoints. Using geometric relationships, the desired heading angle required for the USV to reach the look-ahead point is computed. By adjusting the thrust difference between the port and starboard propellers, the USV is steered such that its actual heading aligns with the desired heading. In this way, the USV continuously follows the target trajectory, ultimately achieving effective trajectory tracking.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the pure pursuit guidance algorithm.

In this work, a dynamic look-ahead point selection strategy is adopted when applying the pure pursuit algorithm, as illustrated in the right panel of Figure 2. First, all discrete points on the target trajectory are traversed, and the Euclidean distance between the USV’s current position and each point is calculated to identify the closest target point. Then take this point as the starting point, along the forward direction of the reference trajectory, select the path point whose trajectory arc length from this point is the preset value Ld, and determine it as the preview point. The preset value of the trajectory arc length is specified as shown in Equation (11):

L is the length of the unmanned ship, and setting the trajectory arc length to 2 times the length of the ship can ensure that the position of the pre-sighting point is far enough in front of the ship to be able to sense the change in the trajectory in advance, but will not cause the reference value of the pre-sighting point to be reduced due to the distance being too far away. The straight-line distance between the USV and this look-ahead point is defined as the look-ahead distance, which also serves as the quantitative metric for the tracking distance error ed. The corresponding calculation is given in Equation (12). Once the look-ahead point is determined, the USV adjusts its heading by modulating the thrust difference between the propellers, allowing the actual heading angle to continuously approach the desired heading angle and thereby reducing the heading error eψ. The corresponding calculation is provided in Equation (13). The algorithm then updates the USV state and selects the next look-ahead point accordingly, repeating the above “look-ahead point selection-heading control” process. This forms a closed-loop tracking procedure that continues until the USV reaches the endpoint of the target trajectory.

In the above equation, (xp, yp) represents the position coordinates of the dynamically determined look-ahead point.

3. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Controller

3.1. Traditional PPO Algorithm

PPO was proposed by OpenAI in 2017 as a policy-gradient-based reinforcement learning algorithm that adopts an Actor-Critic network architecture [32]. Compared with other deep reinforcement learning algorithms, such as DDPG and SAC, PPO demonstrates significant advantages in handling continuous-action decision-making problems. In addition, PPO simplifies the training process and reduces the computational complexity commonly associated with traditional methods.

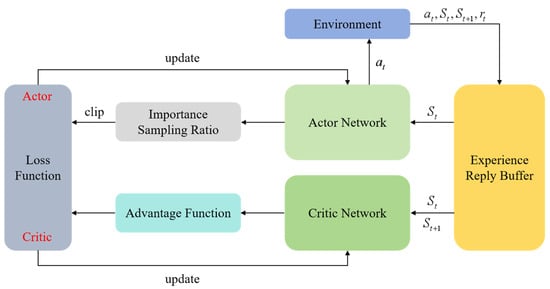

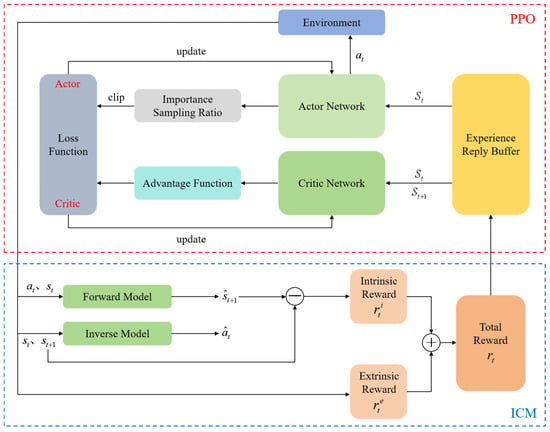

PPO is an on-policy algorithm, meaning that it generates data through real-time interactions between the current policy and the environment and then updates the policy directly using these newly collected samples. Traditional policy-gradient methods often suffer from difficulties in controlling the update step size and exhibit low data utilization efficiency. The core idea of PPO is to constrain the deviation between the updated policy and the previous policy, thereby limiting the magnitude of policy updates. This prevents drastic oscillations during iteration and enables efficient and stable policy optimization. The structural schematic of the algorithm is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the PPO algorithm structure.

The PPO algorithm is built upon the Actor-Critic architecture and utilizes importance sampling to enable an effective transition from on-policy to off-policy style updates. Furthermore, the introduction of the clipping mechanism enhances the stability of policy optimization by preventing excessively large policy updates. In addition, the algorithm incorporates Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) to improve the accuracy of advantage computation, thereby achieving efficient and stable learning performance.

Importance sampling serves as a key mechanism enabling PPO to perform off-policy learning. By introducing a probability ratio to correct the discrepancy between the new and old policies, importance sampling allows PPO to reuse data collected from previous policies for multiple optimization epochs. This significantly improves sample efficiency while ensuring that policy updates remain theoretically grounded. The importance sampling ratio is defined as shown in Equation (14):

where πθ(at|st) represents the probability of selecting action a under the new policy in state s, and πθold(at|st) represents the probability of selecting action a under the old policy in state s.

Building on this, PPO integrates the importance sampling ratio and clipping mechanism into the objective function, imposing constraints on the policy update process to prevent issues such as training instability that may arise from large policy updates. The objective function is defined as shown in Equation (15):

where the advantage function A(s, a) plays a crucial role in the policy update: when A(s, a) > 0, it indicates that action a performs better than the average in state s, and the policy increases the probability of selecting that action through gradient ascent; when A(s, a) < 0, the probability of selecting that action is decreased, causing the policy to favor actions with higher advantages. At the same time, the clipping function strictly limits the importance sampling ratio within the range [1 − ε, 1 + ε]. If the ratio exceeds this range, it is clipped to 1 + ε; if it falls below the range, it is clipped to 1 − ε. The final objective function for updating the policy network is then taken as the minimum of the unclipped and clipped objective functions.

To further enhance the stability of policy updates, PPO introduces the GAE technique to smooth the advantage function [33]. GAE introduces a hyperparameter and weights the multi-step temporal difference (TD) errors, reducing the variance of the advantage estimate while minimizing the bias. This results in a stable advantage estimate. The definition of GAE is given in Equation (16):

where δt+k is the TD residual and γ is the discount factor.

Under the Actor-Critic network architecture, the PPO loss function consists of three components: the policy network loss, the value network loss, and the entropy regularization term, as shown in Equation (17):

in the above equation, Lpolicy(θ) and Lvalue(θ) are as shown in Equations (18) and (19). c1, c2 represent the weight coefficients for the value network loss and the entropy regularization term, respectively. The entropy regularization term H(πθ(st)) encourages exploration by the policy, preventing premature convergence to local optima.

As shown above, the main objective of the PPO algorithm is to find an optimal policy through the interaction between the agent and the environment, maximizing the reward function value with the optimal control policy. In complex marine disturbance environments, the state transitions of an unmanned surface vehicle (USV) are highly stochastic and uncertain, while traditional exploration mechanisms achieve satisfactory control performance only under idealized conditions and do not sufficiently account for the dynamic variability of the marine environment. This limitation narrows the agent’s exploration space, weakens the algorithm’s generalization capability, and reduces its adaptability to disturbances and uncertainties, ultimately leading to degradation of robustness. Accordingly, the next section presents improvements to the conventional PPO algorithm: an Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM) is introduced to construct an intrinsic reward mechanism that supplies an internal drive to guide the agent to proactively explore states with high learning value, thereby mitigating the limitations of traditional exploration mechanisms.

3.2. PPO Algorithm with Intrinsic Curiosity Module

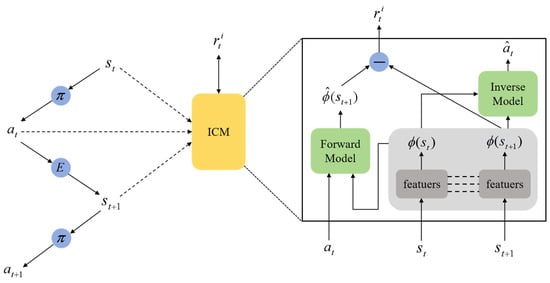

The Intrinsic Curiosity Module, proposed by Pathak et al. [34] in 2017, is an intrinsic reward mechanism for reinforcement learning. It works by constructing a forward model and an inverse model, converting prediction errors into intrinsic rewards. The larger the prediction error, the higher the uncertainty of the agent regarding the current environment, leading to an increase in the corresponding intrinsic reward. This, in turn, generates a strong incentive signal that guides the agent to actively explore the unknown regions of the environment.

The structure of the ICM is shown in Figure 4. On the left side, the agent selects an action at based on the current state st through its policy π and interacts with the environment to obtain the next state st+1. The right side represents the internal structure of the ICM. First, the high-dimensional state st, st+1 is encoded into a low-dimensional feature vector ϕ(st) and ϕ(st+1) using a feature extractor. The inverse model then outputs the predicted action ât that causes the state transition, as represented by Equation (20):

where fIM represents the function of the inverse model, and θIM denotes the parameters of the inverse model.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the ICM structure.

The forward model takes the current action value at and the state feature vector ϕ(st) as inputs and outputs the predicted state feature vector (st+1) for the next time step, as shown in Equation (21):

where fFM represents the function of the forward model, and θFM denotes the parameters of the forward model.

Therefore, the intrinsic reward of the curiosity mechanism can be computed by minimizing the prediction error of the forward model, defined as shown in Equation (22).

Here, ξ(ξ > 0) denotes the scaling factor of the intrinsic reward. By adjusting the value of ξ, the magnitude of the intrinsic reward can be regulated, thereby preventing the intrinsic reward from dominating the training process or causing instability.

The intrinsic reward reflects the agent’s curiosity about the current environment. The larger the error, the higher the intrinsic reward, which encourages the agent to explore unknown areas of the environment in order to reduce future prediction errors.

As shown in Figure 5, the traditional PPO algorithm is combined with ICM, transforming the algorithm’s solely extrinsic reward model into one that involves both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. This motivates the agent to actively explore the unknown environmental changes. The extrinsic reward is the reward signal directly provided by the environment, ensuring that the agent’s learning process consistently focuses on the objective of high-precision trajectory tracking. In contrast, the intrinsic reward is primarily used to encourage the agent to explore states with high uncertainty, driving proactive exploration of unfamiliar regions. If the weight of the extrinsic reward is excessively high, the agent may easily fall into a local optimum. Conversely, an overly dominant intrinsic reward may cause the agent to deviate from the main task and engage in meaningless exploration. The intrinsic reward values have already been subjected to an initial scaling operation, so there is no need for a second scaling in this session. A balanced weighting ratio of 1:1 ensures that the agent maintains high tracking accuracy while still being motivated to explore complex and dynamic marine environments. Therefore, the total reward for the agent is given by , and the improved algorithm aims to train the policy to maximize the value of this total reward function, allowing the agent to learn the optimal policy in complex environments.

Figure 5.

Structure diagram of the PPO-ICM.

3.3. Markov Decision Process Modeling

DRL builds upon the framework of reinforcement learning and learns the optimal control policy through the process of collecting environmental states, taking actions, and receiving reward feedback. It is primarily used to solve continuous decision-making problems in unmanned systems, which can be mathematically modeled as Markov Decision Processes (MDPs).

The design of the components of the MDP is the most critical aspect. The key components primarily include the state space, action space, and reward function. The rationality of the design of these three components directly determines the convergence ability and control performance of the algorithm. Therefore, the MDP can be designed as follows:

- (1)

- State space

The USV model, through the integration of multiple sensors, can accurately obtain the three key states-position, velocity, and attitude-required at each time step. The selection of the state space is based on the requirements of the USV model, where important parameters that reflect the USV’s motion state and fulfill the control objectives are chosen. The global position (x, y) and heading angle ψ of the USV are not included in the state space, since they have already been transformed into tracking error variables through the pure pursuit guidance algorithm. Therefore, there is no need to redundantly include these variables in the state space, which helps reduce the state dimension and avoid unnecessary computational burden. Acceleration, as the first-order derivative of velocity and angular velocity, reflects the rate-of-change information of the motion state, which is an important supplement to the existing state variables. It embodies the transient motion response of the USV when external environmental perturbations or control inputs change, further reflecting the details of the dynamics during the ship’s motion, thus providing a richer and more complete state characterization for the smart body. In addition, the acceleration can reflect the changing trend of the motion state of the unmanned vessel in advance, enabling the control system to adjust the thruster thrust in a timely manner before significant changes in velocity or attitude occur. Therefore, the initial state space is composed of the surge velocity u, sway velocity v, yaw rate r, surge acceleration , sway acceleration , and yaw acceleration at the current time.

The pure pursuit guidance algorithm requires the USV to adjust its motion autonomously based on its current position and the lookahead target point, using the target heading angle and lookahead distance as references. To ensure that the current state accurately reflects the convergence behavior of the tracking error, additional parameters from the pure pursuit algorithm must be incorporated into the state space. These include the difference eψ between the target heading angle and the actual heading angle of the USV, as well as the Euclidean distance ed between the current position of the USV and the lookahead point. Based on the above considerations, the final state space of the USV is designed as follows:

State normalization is a preprocessing technique widely adopted in DRL to improve the stability and efficiency of policy training. In this work, the theoretical maximum value of each state variable is first obtained through the established USV dynamic model by simulating its full operating envelope. These values are used to determine the dynamic range of each state dimension. Subsequently, a linear normalization transformation is applied to scale every raw state variable according to its corresponding boundary, mapping it into the standard interval of either [−1, 1] or [0, 1]. This process yields normalized state variables, which serve as the basis for the subsequent algorithmic design and controller training. The range of values used for the state quantity normalization process is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Range of values for normalization of state quantities.

- (2)

- Action space

In the trajectory tracking control of the unmanned surface vehicle (USV), the action space defines the set of all control outputs that the USV can execute. Considering the characteristics of the catamaran USV model, it is equipped with only two thrusters, one on the left and one on the right. Therefore, the action space consists of only two action values Fleft, Fright. The thrust values are constrained according to the practical control requirements of the USV, with the thrust range set as [−45, 45] N. Consequently, the action space of the USV is designed as follows:

- (3)

- Reward function

The reward function serves as the criterion for evaluating the quality of the agent’s actions. It converts the control objectives into quantifiable numerical signals, guiding the agent to learn the optimal policy through trial and error. In this paper, a multi-objective composite reward function is adopted. A smaller desired heading error and distance error correspond to a higher reward value. Therefore, the reward function is designed in the form of Equations (25)–(27):

where rh is the reward in the direction of the USV’s velocity, and θ is the angle between the actual motion direction of the USV and its heading. By introducing this reward, the USV’s motion posture is effectively constrained, preventing the situation where the actual motion direction opposes the heading direction, ensuring that the USV moves in the desired heading direction. Based on several experimental adjustments, the weight variables k1, k2, k3 are set to 0.6, 0.5 and 0.1, respectively. Therefore, the total reward function of the agent is expressed as shown in Equation (28).

4. Experiments and Analysis

To validate the effectiveness of the improved PPO algorithm, a python simulation environment is first set up, and tests are conducted on different trajectories. Then, we carry out an analysis on the comparative experiments of different algorithms in the same testing environment, where the training episodes, testing episodes and disturbance model settings of all algorithms are kept consistent. The purpose of the comparative experiments is to compare the improved PPO algorithm with other DRL algorithms, highlighting its strong robustness and superior generalization ability.

4.1. Algorithm Training and Testing

In this study, the training and testing of the deep reinforcement learning models are conducted on a Linux (Ubuntu, 22.04) operating system. The hardware platform is equipped with a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Ti GPU with 12 GB of memory (Nvidia Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The software environment is configured using CUDA version 12.2, Python version 3.10.12, and PyTorch version 2.5.0, ensuring adequate computational support and compatibility for model training and evaluation.

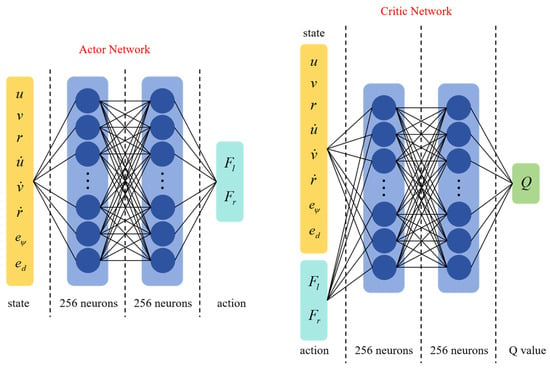

The PPO-ICM model consists of two neural networks: an Actor network and a Critic network. The network architecture is illustrated in Figure 6. All networks adopt a two-hidden-layer architecture with ReLU activation functions, and the dimensionality of each hidden layer is uniformly set to 256. The detailed hyperparameter settings are listed in Table 3. To ensure stable network training, each training episode is configured with 2500 steps. Since the policy requires gradual refinement to achieve reliable optimization, the learning rate is set as 1 × 10−4 to adjust steadily toward the optimal solution. In addition, the policy is updated 15 times per episode to further enhance training stability. The small learning rate prevents drastic fluctuations in the actions, ensuring smooth motion of the USV. The input layer of the network receives the 8-dimensional normalized USV state. After processing through the neural network, the output layer produces the left and right thrust values. These values are then passed through a tanh activation function to constrain the actions within a specified range [−1, 1], and are transformed linearly to obtain the actual thrust values. The Critic network is responsible for providing accurate and timely state-value estimates, therefore, it must converge quickly, and its learning rate is typically set 1 × 10−3. Both the Actor and Critic networks employ the Adam optimizer, which ensures stable performance when adjusting the USV thrust outputs.

Figure 6.

Architecture of the Actor and Critic networks.

Table 3.

Hyperparameters for algorithm training.

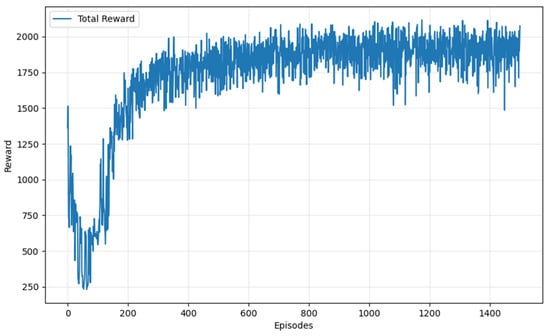

Based on the above training conditions and parameter settings, this study takes the twin-hull USV as the research object, generating a straight-line reference trajectory from (0, 0) to (100, 100). Systematic simulation training and performance testing of the PPO-ICM algorithm are conducted based on the constructed ship environment system.

PPO-ICM is trained under disturbance-free environmental conditions. The total return obtained during training is shown in Figure 7. The figure illustrates the evolution of the PPO-ICM algorithm’s total reward over training episodes. During the first 0–200 episodes, the ICM motivates the USV to actively explore the environment and rapidly accumulate effective experience. As a result, the total reward increases quickly from approximately 250 to over 1500. Meanwhile, the PPO strategy update mechanism ensures steady reward growth, demonstrating the algorithm’s efficient learning capability in the early training stage. After around 200 episodes, the reward fluctuates within the range of 1750–2000, indicating that the algorithm has learned a near-optimal policy and the reward gradually converges.

Figure 7.

Total reward curve.

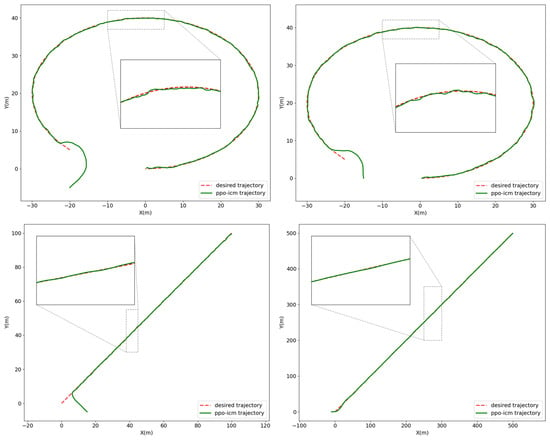

Figure 8 presents the trajectory tracking test results of the controller model saved by the PPO-ICM algorithm. External disturbances, including wind, waves, and currents, are introduced in the test environment, with the specific parameters set to a wind speed of 3 m/s, a wave height of 0.5 m, and a current velocity of 0.3 m/s. To evaluate the generalization capability of the trained model, experiments are conducted under different initial positions and initial headings, and trajectory tracking tests are performed using reference trajectories of different types and lengths.

Figure 8.

Trajectory tracking test under different initial conditions.

The experimental results indicate that, in the curved trajectory tracking tests, the average lateral errors of the USV under different initial conditions are 0.46 m and 0.34 m. In the straight-line trajectory tracking tests, validation results under different initial conditions and trajectory lengths show average lateral errors of 0.33 m and 0.69 m. As illustrated in the figure, once the USV approaches the vicinity of the reference trajectory, it rapidly converges toward the desired trajectory, achieving a high degree of overlap between the actual and reference trajectories. These results confirm the high control accuracy of the proposed algorithm and its strong generalization capability across varying initial conditions and trajectory configurations.

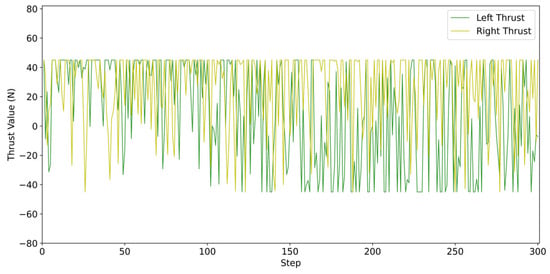

Figure 9 illustrates the dynamic variation in the left and right propeller thrusts of the USV during the first 300 steps of the straight-line trajectory tracking task. With reference to the predefined thrust limits of [−45 N,45 N], the characteristics of the curves can be analyzed as follows: the thrust commands of both propellers vary dynamically with the simulation steps while remaining within the prescribed bounds, and no saturation exceeding the physical actuation limits of the USV is observed. All thrust commands are physically feasible and consistently maintained within a safe operating range, thereby effectively avoiding control failures caused by thrust overload. Since the experimental platform is a rudderless twin-hull USV, steering and trajectory correction are achieved through real-time adjustment of differential propeller thrust. Consequently, the observed dynamic variations in the thrust curves directly reflect the algorithm’s ability to perceive environmental disturbances and perform rapid corrective actions, and represent the adaptive responses of the PPO-ICM algorithm to wind, wave, and current disturbances. The time-varying behavior of the left and right thrusts further indicates that the algorithm can autonomously adjust thrust allocation based on real-time trajectory deviations, ensuring both fast disturbance rejection and stable trajectory tracking performance.

Figure 9.

Control command variation curves of the controller.

In summary, the thrust variation curves validate that the proposed PPO-ICM algorithm possesses dynamic control capability suitable for complex environments, while simultaneously ensuring the safety and effectiveness of the generated control commands.

4.2. Experimental Results

In this section, a comparative analysis is conducted among the SAC, DDPG, PPO, and the proposed PPO-ICM algorithms. Both simple and complex trajectory tracking experiments are designed to comprehensively evaluate the performance of the algorithms. The hyperparameter settings of the SAC and DDPG algorithms are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hyperparameters for algorithms.

4.2.1. Simple Trajectory

The experiment adopts a linear trajectory as the reference path for unmanned surface navigation and constructs a randomly time-varying disturbance environment to simulate real marine conditions: the directions of wind, wave and current change with time randomly within the full angular range of [0, 2π] rad. The wind speed is sampled within the interval [1.0, 1.5] m/s; the wave parameters are set as wave height [0.2, 0.5] m and peak period [3.0, 5.0] s. The current direction in the earth-fixed coordinate system is determined by the combined longitudinal and lateral flow components; therefore, both components of the current velocity are set to [−0.3, 0.3] m/s. In addition, the disturbance intensity at each time step is generated independently and randomly, thereby emulating the highly dynamic and complex perturbations present in actual ocean environments. Beyond the disturbance settings described above, the remaining environmental parameters for the simulation experiment are configured as follows: the starting point of the reference trajectory is set to (0, 0), and the endpoint is set to (100, 100). The initial position of the USV is set to (−10, 0), with the initial heading angle, initial velocity, and all control variables initialized to zero.

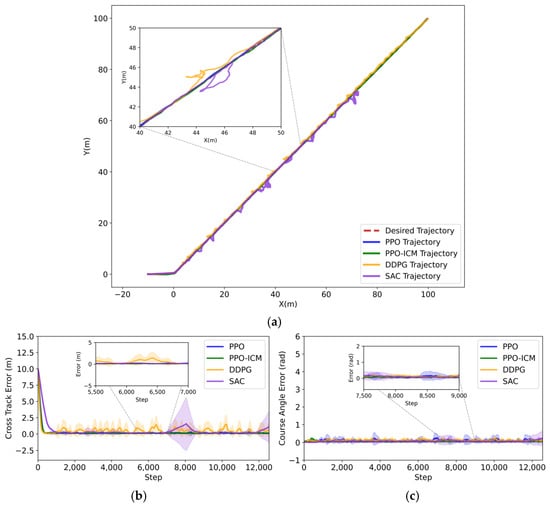

Figure 10 presents a comparison of the performance of four methods in the straight-line trajectory tracking task, including the traditional PPO algorithm, the improved PPO-ICM algorithm, DDPG, and SAC. Both PPO and PPO-ICM employ the same network architecture and hyperparameter settings. As shown in Figure 10a, under the interference of complex sea conditions, all four algorithms are capable of tracking the long-distance straight-line trajectory; however, there are significant performance differences among them. The actual trajectories of the SAC algorithms show deviations from the reference trajectory. In contrast, DDPG and PPO, while affected by environmental disturbances, exhibits oscillations in the trajectory, though the degree of deviation is smaller than that of SAC. The lateral error and heading error of PPO-ICM algorithm converge to the interval [0, 0.5], and its actual trajectory and reference trajectory have a high degree of overlap, which can support the USV to realize a more stable trajectory tracking control.

Figure 10.

Comparison results of straight-line trajectory tracking. (a) Trajectory tracking result plot; (b) Lateral error; (c) Heading error.

The error curves show the average error and standard deviation ranges of the four algorithms for 10 repetitions of the experiment. Based on the error curves in Figure 10b,c, further analysis shows that the DDPG algorithm reaches a convergent state around step 170, while the PPO algorithm stabilizes at around step 220. After convergence, both algorithms still exhibit slight fluctuations in the error. The SAC algorithm takes approximately 650 steps to stabilize, but the error fluctuations remain relatively large. In contrast, the PPO-ICM algorithm’s lateral error decreases rapidly from the peak to nearly zero, reaching a steady state after approximately 165 steps, with minimal fluctuations in the heading error.

Table 5 presents a systematic comparison of the straight-line trajectory tracking performance of four algorithms over ten repeated experiments, using lateral error, heading error, root mean square error (RMSE), and standard deviation as quantitative evaluation metrics. The results indicate that the proposed PPO-ICM algorithm achieves an average lateral error of 0.166 m with a corresponding mean standard deviation of 0.620 m, an average heading error of 0.070 rad with a corresponding mean standard deviation of 0.062 rad, and an average RMSE of 1.723 m with a corresponding mean standard deviation of 0.522 m. All these performance metrics are lower than those obtained by SAC, DDPG, and PPO. These results clearly demonstrate that the PPO-ICM algorithm exhibits superior trajectory tracking performance under complex environmental conditions.

Table 5.

Evaluation metrics for straight-line trajectory tracking experiments.

Further analysis of Figure 10 and Table 5 indicates that, compared with the PPO algorithm, the proposed PPO-ICM achieves a reduction of 54.2% in average lateral error and 47.1% in average heading error, which clearly demonstrates the significant advantages of the improved PPO-ICM algorithm in terms of trajectory tracking accuracy and heading control stability.

4.2.2. Complex Trajectory

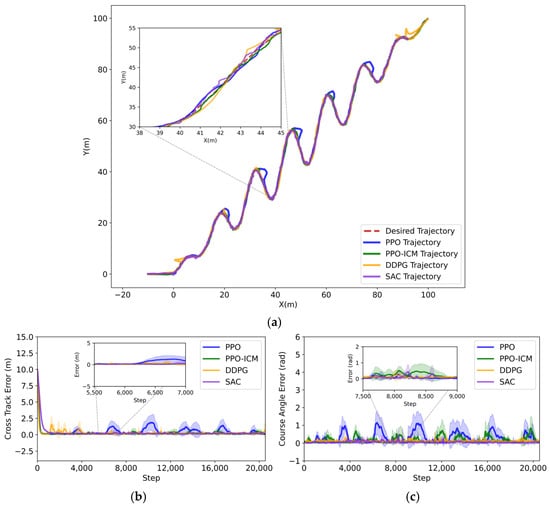

To evaluate the algorithm’s tracking performance in complex dynamic scenarios, a non-symmetric periodically varying curve was selected as the complex reference trajectory, with the starting point set to (0, 0) and the endpoint set to (100, 100). The reference trajectory extends along the positive x-axis and exhibits sinusoidal fluctuations within each period. Through continuous periodic turns and a fixed amplitude design, it simulates the complex scenario of frequent directional changes encountered in actual vessel navigation. This set up effectively tests the robustness and stability of the algorithm in trajectory tracking tasks. In this simulation experiment, the randomly time-varying environmental disturbance parameters and the initial state of the USV are kept consistent with the settings in the simple trajectory scenario.

The error curves in Figure 10 illustrate the mean errors and the corresponding standard deviation ranges of the four algorithms over ten repeated experiments. Based on the experimental results shown in Figure 11, a systematic analysis of the performance of the SAC, DDPG, PPO, and PPO-ICM algorithms in the complex periodic trajectory tracking task can be conducted: although the PPO algorithm can complete long-distance tracking, there is a delay in steering adjustments at local wave peaks, causing deviations between the actual trajectory and the reference trajectory. The corresponding error curve also exhibits oscillations in the later stages, indicating relatively poor generalization ability of the model; due to the influence of the disturbed environment, the actual trajectory of DDPG deviates in the stages of the task, and its error curve also exhibits corresponding fluctuations, indicating unstable controller performance; the actual trajectory of the SAC algorithm aligns well with the reference trajectory, and its overall performance is superior to that of DDPG and PPO. However, the algorithm converges slowly and requires a longer time to reach a stable tracking state. Both the DDPG and SAC algorithms tend to exhibit conservative convergence behavior. When subjected to environmental disturbances or trajectory variations, they perform only small and gradual corrective actions. As a result, the heading error shows no pronounced fluctuations; however, the delayed corrections may lead to occasional small deviations from the desired trajectory. Compared to the other three algorithms, the actual trajectory of PPO-ICM has no significant trajectory deviation from the reference trajectory. Its distance error converges to the interval [0, 1] and stabilizes within a short period of time. Although there are brief, minor fluctuations in the heading error curve due to high-frequency turns, the error eventually stabilizes. This characteristic demonstrates the high dynamic sensitivity of the PPO-ICM algorithm, allowing it to quickly adapt to the periodic direction changes in complex trajectories, thereby achieving high-precision trajectory tracking.

Figure 11.

Comparison results of complex trajectory tracking. (a) Trajectory tracking result plot; (b) Lateral error; (c) Heading error.

Table 6 presents the mean values of the evaluation metrics obtained from ten repeated experiments. The PPO-ICM algorithm demonstrates superior performance in complex trajectory tracking control tasks, achieving an average lateral error of 0.221 m with a corresponding standard deviation of 0.570 m, an average heading error of 0.186 rad with a corresponding standard deviation of 0.288 rad, and an average RMSE of 4.185 m with a corresponding standard deviation of 0.713 m. These results collectively confirm the performance advantages of the PPO-ICM algorithm under complex dynamic environmental conditions.

Table 6.

Evaluation metrics for complex trajectory tracking experiment.

Further analysis of Figure 11 and Table 6 shows that, for the complex trajectory, the proposed PPO-ICM algorithm achieves a reduction of 91.8% in average lateral error and 41.9% in average heading error compared with the PPO algorithm, thereby effectively demonstrating the feasibility of the proposed PPO-ICM approach.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a trajectory tracking controller based on a DRL algorithm, which deeply integrates the PPO algorithm with ICM. The controller aims to address the limitations of traditional algorithms in terms of tracking accuracy and robustness in complex trajectories and dynamic disturbance scenarios, by leveraging the dynamic decision-making capability of reinforcement learning and the exploration capability of the curiosity module. Additionally, the pure pursuit guidance algorithm’s line-of-sight guidance mechanism is introduced to provide intuitive heading and distance decision references for the agent. The adaptive learning capability of PPO-ICM compensates for the shortcomings of the pure pursuit algorithm in nonlinear and complex marine conditions, ultimately achieving a collaborative improvement in trajectory tracking accuracy and robustness of USVs in complex dynamic environments.

To validate the performance of the proposed controller, this paper designs comparative experiments using simple and complex trajectories. The PPO-ICM controller is systematically tested based on the trajectory tracking results and error fluctuation characteristics of 10 repeated experiments. Further analysis indicates that, in the simple trajectory scenario, the RMSE achieved by the PPO-ICM algorithm is reduced by 10.571 m and 19.257 m compared with the DDPG and SAC algorithms, respectively, and by 2.9 m compared with the PPO algorithm. In the complex trajectory scenario, the RMSE is reduced by 4.642 m and 5.685 m relative to the DDPG and SAC algorithms, respectively, and by 3.494 m compared with the PPO algorithm. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed controller significantly reduces error fluctuations under complex dynamic conditions and achieves a high level of fitting accuracy between the actual and reference trajectories, thereby providing an efficient and feasible solution for high-precision trajectory tracking of USVs in real-world complex marine environments.

6. Discussion

The experimental results indicate that the PPO-ICM controller model exhibits excellent performance in multiple metrics (e.g., average lateral error, average heading error, and root mean square error), which is consistent with the research conclusions of Wu et al. [16]. They designed a PPO controller based on the ICM combined with an improved guidance law and tested it in an environment with wind and wave disturbances. Although this guidance method sacrifices part of the response speed, it can enhance the stability and reliability of the system.

Zhou et al. [28] also found that the self-designed controller can significantly improve the adaptability and robustness of USVs under complex environmental disturbances. They selected part of the South China Sea as the research area, integrated real meteorological data and satellite ocean data to build a marine environment model, and adopted a self-designed USV trajectory tracking controller based on hybrid priority twin delayed deep deterministic policy gradient (TD3) combined with the LOS guidance algorithm. The controller was tested in a marine environment containing obstacles, and the algorithm performance was evaluated through time difference (TD) error and reward value.

The main advantage of the method proposed in this paper is that the PPO-ICM controller combined with pure pursuit guidance can achieve high-precision trajectory tracking under the combined disturbances of wind, waves, and currents while reducing computational complexity. Compared with other deep reinforcement learning algorithms (DDPG, SAC, and PPO), this method accelerates the convergence speed of the controller and thus improves learning efficiency. Despite the excellent performance of the model, future research should focus on developing methods with stronger learning capabilities. Research on control methods in different fields may be considered, such as energy-based control and linear matrix inequality (LMI)-based control for quadrotors transporting payloads [35], and robust linear parameter-varying (LPV) modeling and control for aircraft flying through wind disturbances [36].

At present, the test background is mainly based on a simplified complex marine environment. Future research plans to deploy the proposed algorithm on a physical twin-hull USV. For real marine environments with complex working conditions, such as the South China Sea and the Bohai Sea, real data will be used to further verify the algorithm performance, analyze the practical value of the algorithm in engineering applications, and thereby further improve its robustness and generalization ability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Y.; methodology, Y.Z.; validation, Q.T., S.Y., Z.W. and W.M.; resources, Y.W.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project ZR2024MD066 supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation and the project 24YFZCSN00090,25SGHZYJ018 and 24YFYSHZ00160 supported by Tianjin Municipal Key Research and Development Program.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Song, L.; Shi, X.; Sun, H.; Xu, K.; Huang, L. Collision Avoidance Algorithm for USV Based on Rolling Obstacle Classification and Fuzzy Rules. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Gao, H.; Shang, L. Analysis of Key Technologies for Unmanned Surface Vessels (USV). In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Symposium on Control Engineering and Robotics (ISCER), Hangzhou, China, 17–19 February 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Er, M.J.; Ma, C.; Liu, T.; Gong, H. Intelligent Motion Control of Unmanned Surface Vehicles: A Critical Review. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280, 114562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wen, W. Magnetic Detection of Underdriven USV Track Adaptive Tracking in Complex Marine Environment Control Algorithm Research. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 055210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, W.; Wu, C.; Wang, H.; Xiao, L.; Chen, Y. Self-Supervised Learning with High-Stable Guidance Law and Label Generation for USV Trajectory Tracking Control. Ocean Eng. 2025, 329, 121079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minorsky, N. Directional Stability of Automatically Steered Bodies. J. Am. Soc. Nav. Eng. 1922, 34, 280–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yan, H.; Gao, D.; Wang, R.; Li, Q. Adaptive Neural Network Iterative Sliding Mode Course Tracking Control for Unmanned Surface Vessels. J. Math. 2022, 2022, 1417704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yan, H.; Li, Q.; Deng, Y.; Jin, Y. Parameters Optimization-Based Tracking Control for Unmanned Surface Vehicles. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xie, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, G. A Multi-USV Formation Control Method Based on BP Neural Network PID Controller. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Computer, Control and Robotics (ICCCR), Shnaghai, China, 19–21 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, W.; Guo, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lei, Z. Global Sliding Mode Based Adaptive Neural Network Path Following Control for Underactuated Surface Vessels with Uncertain Dynamics. In Proceedings of the 2012 Third International Conference on Intelligent Control and Information Processing, Dalian, China, 15–17 July 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Palomo, G.; Rossiter, J.A.; López-Estrada, F.R. Improving the Feed-Forward Compensator in Predictive Control for Setpoint Tracking. ISA Trans. 2014, 53, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Garcia, A.; Castaneda, H. Guidance and Control Based on Adaptive Sliding Mode Strategy for a USV Subject to Uncertainties. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 46, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ye, H.; Liu, W.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H. An Improved ELOS Guidance Law for Path Following of Underactuated Unmanned Surface Vehicles. Sensors 2024, 24, 5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, N.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, S. Prescribed-Time Observer-Based Sideslip Compensation in USV Line-of-Sight Guidance. Ocean Eng. 2024, 298, 117177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Liu, J.; Cao, H.; Shen, C.; Wang, H. Robust Dynamic Surface Trajectory Tracking Control for a Quadrotor UAV via Extended State Observer. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2018, 28, 2700–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yu, W.; Liao, W.; Ou, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning with Intrinsic Curiosity Module Based Trajectory Tracking Control for USV. Ocean Eng. 2024, 308, 118342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, L.; Xiang, Q.; Qian, T.; Lou, Z.; Xue, W. Research on USV Trajectory Tracking Method Based on LOS Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 14th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design (ISCID), Hangzhou, China, 11–12 December 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 408–411. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Liu, W.; Ye, H.; Zhong, W.; Xiang, Z. Global Path Planning Algorithm Based on Double DQN for Multi-Tasks Amphibious Unmanned Surface Vehicle. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 112809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.; Yu, C.; Kim, N. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Controller for Path Following of an Unmanned Surface Vehicle. Ocean Eng. 2019, 183, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, J.; Damas, B.; Lobo, V. Reinforcement Learning: The Application to Autonomous Biomimetic Underwater Vehicles Control. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 172, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yi, H.; Xu, J.; Xu, C.; Song, L. PID Controller Based on Improved DDPG for Trajectory Tracking Control of USV. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Chen, Y.; Hong, X.; Luo, H.; Chen, G. Research on Path-Following Technology of a Single-Outboard-Motor Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning and Model Predictive Control Algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Tao, J.; Sun, Q.; Sun, H.; Chen, Z.; Sun, M.; Xie, G. Soft Actor–Critic Based Active Disturbance Rejection Path Following Control for Unmanned Surface Vessel under Wind and Wave Disturbances. Ocean Eng. 2022, 247, 110631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Xi, Z.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, X. Adaptive Trajectory Controller Design for Unmanned Surface Vehicles Based on SAC-PID. Brodogradnja 2025, 76, 76206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qi, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Malekian, R.; Sotelo, M.A. Path Following Optimization for an Underactuated USV Using Smoothly-Convergent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2021, 22, 6208–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, Y.; Wu, D. Underactuated MSV Path Following Control via Stable Adversarial Inverse Reinforcement Learning. Ocean Eng. 2024, 299, 117368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Wang, L.; Meng, H.; Yang, C. Data-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning and Active FTC for Unmanned Surface Vehicles. J. Frankl. Inst. 2024, 361, 106960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gong, C.; Chen, K. Adaptive Control Scheme for USV Trajectory Tracking Under Complex Environmental Disturbances via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 15181–15196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Cai, Q.; Yi, H. Deep Learning Method for 3-DOF Motion Prediction of Unmanned Surface Vehicles Based on Real Sea Maneuverability Test. Ocean Eng. 2022, 250, 111015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Gu, S.; Wen, Y.; Du, Z.; Xiao, C.; Huang, L.; Zhu, M. The Review Unmanned Surface Vehicle Path Planning: Based on Multi-Modality Constraint. Ocean Eng. 2020, 200, 107043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, A.J. Water Waves and Ship Hydrodynamics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 978-94-007-0095-6. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wu, Q. Research on Collision Avoidance Algorithm of Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 11262–11273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Moritz, P.; Levine, S.; Jordan, M.; Abbeel, P. High-Dimensional Continuous Control Using Generalized Advantage Estimation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1506.02438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, D.; Agrawal, P.; Efros, A.A.; Darrell, T. Curiosity-Driven Exploration by Self-Supervised Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 488–489. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Sánchez, M.-E.; Hernández-González, O.; Lozano, R.; García-Beltrán, C.-D.; Valencia-Palomo, G.; López-Estrada, F.-R. Energy-Based Control and LMI-Based Control for a Quadrotor Transporting a Payload. Mathematics 2019, 7, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Fu, J. Robust LPV Modeling and Control of Aircraft Flying through Wind Disturbance. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2019, 32, 1588–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.