Abstract

This study systematically evaluated the dynamic habitat suitability of Portunus trituberculatus in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea region (referred to herein as the East Yellow Sea region for brevity) under climate change impacts by integrating a species distribution model (Biomod2) with multi-source environmental data. Through the construction and evaluation of an ensemble model combining 10 algorithms, using the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and True Skill Statistic (TSS) for validation, we identified seabed temperature, seabed salinity, and chlorophyll as key environmental factors. Results showed that current high-suitability areas are concentrated in coastal Jiangsu, the Yangtze River estuary, and Zhoushan Archipelago waters, which overlap significantly with fishing hotspots. Under future climate scenarios, the species’ suitable habitat distribution is projected to shift significantly poleward: In the SSP5-8.5 scenario 2100, low/medium suitability areas increased by 38.2% and 88.2% respectively, while high-suitability areas decreased by 36.5%, with core spawning grounds (e.g., Zhoushan Archipelago waters) showing reduced suitability indices. The Bohai Sea’s summer water temperature unsuitability for Portunus trituberculatus migration creates an “ecological bottleneck” for northward expansion. The study proposes strengthening habitat management in Jiangsu coastal areas and integrating dynamic habitat prediction into fisheries policies to address climate-induced resource redistribution and ecosystem service changes. Our findings underscore the urgency of incorporating climate-driven habitat shifts into adaptive marine spatial planning and fisheries management frameworks.

1. Introduction

Climate change, a prime example of human activities’ profound impact on the natural environment this century, has emerged as one of the most severe long-term threats to marine ecosystems [1]. When combined with factors like overfishing, habitat degradation, and pollutant discharge, these elements collectively alter the physical and chemical conditions of the ocean, thereby exacerbating the challenges confronting global fisheries resources [2].

Habitat suitability, as a core indicator for quantitatively assessing species-environment coupling relationships, establishes a theoretical framework for sustainable utilization of biological resources by integrating multidimensional environmental factor thresholds with ecological niche characteristics [3]. In this study, habitat suitability was operationalized as the Habitat Suitability Index (HSI), which is a continuous probability value ranging from 0 to 1, directly derived from our ensemble species distribution model (Biomod2). Areas were subsequently classified into four suitability levels (e.g., HSI ≥ 0.8 as highly suitable) for analysis and management recommendations, following common practice in SDMs studies [4]. In marine ecosystems, this indicator has been extensively applied in identifying key species habitats, evaluating fishery catch potential, and analyzing population replenishment mechanisms [5]. The research paradigm has evolved from static distribution descriptions to dynamic process simulations [6].

The biodiversity crisis triggered by the combined effects of global climate change and human activities is accelerating the restructuring of marine species distribution patterns through habitat fragmentation and ecological function degradation [7,8]. According to Global Biodiversity Outlook, the average annual reduction rate of high-availability coastal habitats over the past 40 years has reached 2.3%, with crustacean species demonstrating particularly pronounced sensitivity to environmental stress [9].

The Portunus trituberculatus, characterized by a short life cycle, high reproductive capacity, and broad tolerance to temperature and salinity [10], has become an ideal model organism for studying climate-driven population dynamics. According to FAO fisheries statistics, its annual catch accounts for approximately one-quarter of the global crab population [11], occupying a critical ecological niche in East Asia’s coastal fisheries economy and food security systems. However, the combined effects of overfishing pressure and spatial heterogeneity in habitat suitability are causing a latitudinal gradient decline in its resource abundance [12].

The East Yellow Sea region serves as a vital coastal fishery in China and the primary production area for economically significant species such as the Portunus trituberculatus, exemplified by the Zhoushan [13]. Numerous rivers including Yangtze and Qiantang Rivers converge here, delivering abundant nutrients. These nutrients interact with the Kuroshio Current and coastal currents, creating complex thermohaline fronts that ensure exceptionally rich foundational food resources and favorable hydrological conditions [14]. This environment makes the region a crucial spawning, feeding, and overwintering ground for numerous marine organisms, including the Portunus trituberculatus [15].

However, in recent decades, the marine habitats of the East Yellow Sea have suffered severe degradation due to multiple human activities including overfishing, environmental pollution, and large-scale coastal engineering projects [16].

Core habitats of numerous species exhibit pronounced fragmentation and islandization, with some coastal areas even facing serious ecological degradation and seasonal oxygen-depleted zones [17]. This degradation, sometimes described as “oceanic desertification”, is evidenced by measurable indicators including a significant decline in the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) of coastal wetlands and persistently high chlorophyll-a concentrations signaling eutrophication [18]. Similar to other economically important species, the traditional habitats of Portunus trituberculatus continue to shrink. Population sizes show annual and seasonal fluctuations, with overall resource levels persistently declining [19].

Habitat suitability assessment has been well-established in inland aquatic resource management, while its application in marine ecosystems remains relatively underdeveloped [20]. Recent studies have predominantly focused on pelagic fishery resources [21,22,23], leaving substantial research potential for economically significant nearshore species. Currently, systematic habitat suitability studies for the East Yellow Sea fisheries resources in China are still in their infancy. Research on Portunus trituberculatus, a key species in this region, remains limited, with existing studies mainly concentrated on habitat distribution in specific areas of the East Yellow Sea [24,25]. However, the application of species distribution models (SDMs) for assessing and managing crustacean fisheries is rapidly evolving. Recent methodological advances have employed ensemble SDMs to evaluate climate change impacts on benthic crustaceans in the Yellow and East China Seas [26]. This study builds upon and contributes to this growing body of work by providing a comprehensive habitat projection for Portunus trituberculatus. It provides crucial theoretical foundations for the scientific conservation of this species and effective habitat restoration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Distribution Data of Portunus Trituberculatus

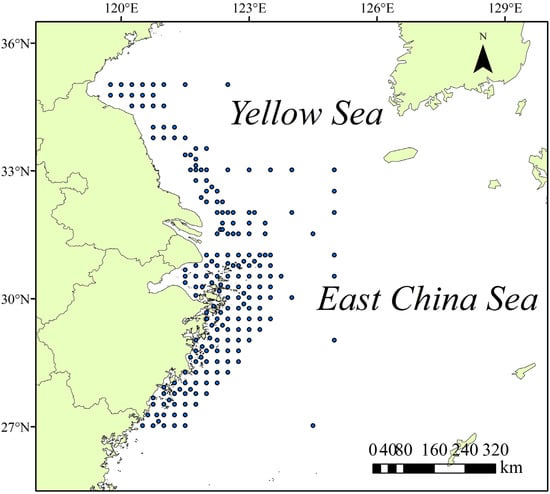

The distribution data of Portunus trituberculatus was primarily sourced from trawling survey records (2009–2023) and monitoring data from crab cages and gillnets conducted by the Zhejiang Marine Fisheries Research Institute, along with data downloaded from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) [27]. To ensure data quality, a two-stage screening process was implemented: First, records prior to 2010 were excluded to reflect the current distribution status of the species. Second, to ensure spatial accuracy, data points were screened for geographic plausibility by cross-referencing their coordinates with high-resolution bathymetric and bottom temperature data. Points exhibiting impossible combinations were discarded. Third, to mitigate the effect of spatial autocorrelation (which can inflate model performance and reduce transferability) and to avoid sampling bias from clustered records, we performed spatial thinning of the occurrence data. The study area was divided into 5′ × 5′ grid cells, retaining only one randomly selected presence record per cell. This approach is a recommended preprocessing step in SDM studies to ensure data independence and improve model robustness [28]. Ultimately, 199 distribution records were obtained for subsequent species distribution modeling (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research area and station site.

2.2. Environmental Variables

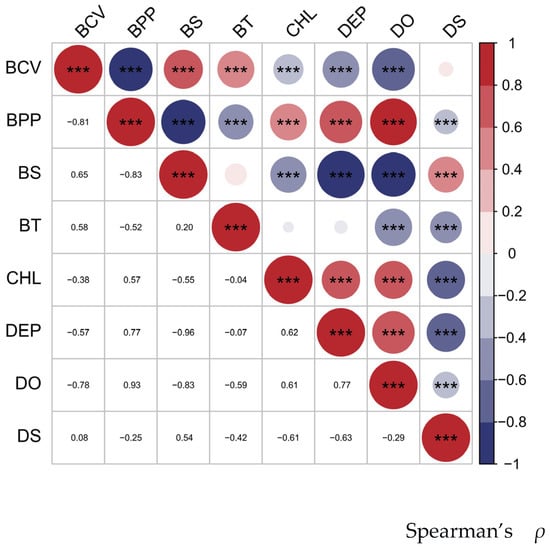

Considering the availability of environmental variable data and its correlation with the distribution of the Portunus trituberculatus, eight environmental variables (bottom temperature, bottom salinity, current velocity, depth, distance from shore and primary productivity) were selected for subsequent analysis (Table 1). The depth and distance from shore variables were sourced from the Global Marine Environment Datasets (http://gmed.auckland.ac.nz) (GMED) [29], while the other six variables were derived from Bio-ORACLE (https://www.bio-oracle.org/) [30]. Spearman correlation tests were used to assess multicollinearity. When the absolute Spearman coefficient between two environmental variables exceeded 0.8, only one variable was retained [31] (Figure 2). Ultimately, five variables (bottom temperature, bottom salinity, bottom current velocity, distance from shore, and chlorophyll a) were selected to further construct the species distribution models (SDMs).

Table 1.

List of environmental variables (long-term mean values) used in the species distribution models.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients among the eight environmental variables considered for variable selection. Note: The size of each dot is proportional to the absolute value of the Spearman’s correlation coefficient (|ρ|). *** indicates a correlation with the highest level of significance (p < 0.001).

2.3. Construction, Optimization, and Evaluation of Integrated Models

Species distribution model analysis was conducted using the Biomod2 package in R (version 4.5.0). Eleven modeling algorithms were integrated: Artificial neural network (ANN), Classification tree analysis (CTA), Flexible discriminant analysis (FDA), Generalized boosting model (GBM), Generalized linear model (GLM), Multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS), Maximum entropy (Maxent), Random Forest (RF), Surface range envelop (SRE) and Extreme gradient boosting (XGBOOST). Specific package versions are provided in the response to reviewers to ensure full reproducibility.

The “BIOMOD_Formating data” function in the Biomod2 package generates three times the number of pseudocensored data points relative to actual species occurrence data using the “random” method [32]. To assess the robustness of our models to the random selection of pseudo-absence points, we generate three independent replicate sets of pseudo-absences, each sized at three times the number of presence records. For each of these three replicates, 80% of the data (presences and the corresponding pseudo-absences) was randomly selected as the training set, with the remaining 20% used for validation [33]. This process yielded three evaluation runs per algorithm. Model accuracy metrics (AUC and TSS) were calculated across these runs. The final current and future habitat suitability projections presented in this study represent the mean prediction across all valid model runs from the three pseudo-absence replicates. These metrics range from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating higher prediction accuracy [34]. The performance metrics of individual algorithms are presented in Table 2. Notably, the Random Forest (RF) model achieved a perfect training score (AUC = 1.000, TSS = 1.000), which is a classic indicator of overfitting, as an AUC value of 1 on the training data typically signifies that the model has memorized the noise rather than learned generalizable patterns [35]. This underscores the risk of relying on any single, potentially overfitted model for ecological prediction. Therefore, to mitigate such model-specific biases and variances, we constructed a final ensemble model by applying a weighted average to all single models that met our validation criteria (TSS > 0.7 and AUC > 0.8) [36].

Table 2.

Performance metrics of individual algorithms in the ensemble model.

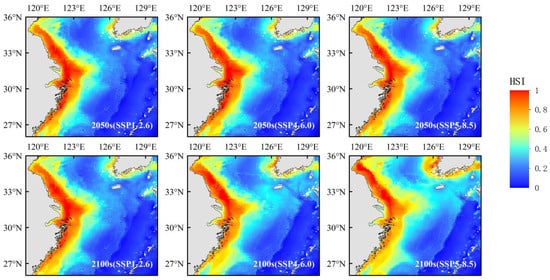

2.4. Current and Future Projections of Potential Suitable Habitat Area

To project future habitat suitability, we utilized climate change scenarios from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). Specifically, we selected three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) representing a range of future greenhouse gas emissions: SSP1-2.6 (low), SSP4-6.0 (medium), and SSP5-8.5 (high) [37]. These scenarios were applied to drive our species distribution model for Portunus trituberculatus. Projections were made for both the mid-century (2050) and end-of-century (2100) time horizons.

The simulation results from Biomod2 were selected based on the highest AUC values to model the current distribution of Portunus trituberculatus and its projected distribution under three climate scenarios for the 2050s and 2100s. Using ArcGIS 10.4 software, the habitat distribution was visualized, and the area of suitable habitats was quantified using the ‘raster’ package in R with consideration for Earth’s curvature. The Habitat Suitability Index (HSI) reflects the likelihood of species presence. According to the study, the habitats of Portunus trituberculatus were classified into four levels: HSI ≥ 0.8 (highly suitable habitat), 0.8 > HSI ≥ 0.6 (moderately suitable habitat), 0.6 > HSI ≥ 0.4 (lowly suitable habitat), and 0.4 > HSI ≥ 0 (unsuitable habitat) [38].

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance

By utilizing Portunus trituberculatus occurrence records and five environmental variables, we successfully constructed a species distribution model ensemble. The evaluation of the ten individual algorithms on the independent test set revealed a range of performances (Table 2), with AUC values from 0.79 to 0.96 (mean 0.88) and TSS from 0.56 to 0.90 (mean 0.71). Subsequently, we developed an integrated SDM by applying a weighted average to those single models meeting our validation criteria (TSS > 0.7 and AUC > 0.8). This ensemble approach significantly improved predictive accuracy, with the integrated model achieving superior and more consistent performance (AUC: 0.93–0.97, mean 0.96; TSS: 0.73–0.77, mean 0.75) compared to any single algorithm.

3.2. Analysis of the Importance of Environmental Variables

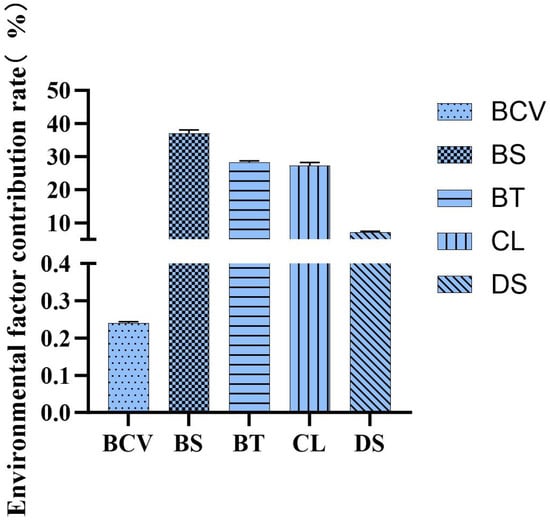

Variable importance was assessed using the permutation-based method implemented in the Biomod2 framework, which quantifies the average decrease in model predictive performance when a given variable is randomized. Biomod2’s integrated methods (EMca, EMmean, EMwmean, EMmedian) consistently indicate that bottom temperature is the most influential factor, contributing 31.9% to 34.7%. Bottom salinity ranks second with 23.9% to 27.9%, followed by chlorophyll at 23.7% to 26.1%. Offshore distance has a minimal impact, typically below 12%, while flow velocity shows the least influence (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Environmental factor proportional significance.

3.3. Current and Future Distribution of Portunus trituberculatus

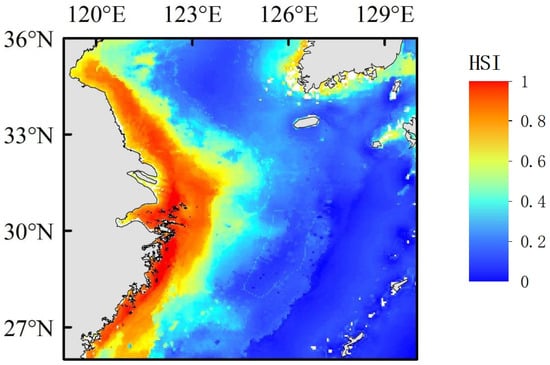

Based on the results of the ensemble model (Figure 4), we mapped the current spatial distribution of Portunus trituberculatus in the East Yellow Sea region layer by layer. Overall, the distribution is relatively extensive, but concentrated in coastal areas, with the East China Sea region being the most extensive. The high-suitability benthic habitat is mainly distributed in the coastal waters of Jiangsu, the Yangtze River estuary, Hangzhou Bay, and the nearshore waters from the Zhoushan Archipelago to Wenzhou. Currently, Portunus trituberculatus is primarily distributed between north latitude 27–35.5° and east longitude 120–123.5°, with the current habitat area covering 286,470.8 km2. Compared to the present, the future suitable habitats are significantly shifting toward northern regions and the Korean Peninsula, especially under high greenhouse gas emission scenarios, where this trend becomes more pronounced.

Figure 4.

Present potential distribution of Portunus trituberculatus.

Based on habitat area calculations (Table 3), low suitability habitats will expand in the 2050s and 2050s, particularly under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. By 2100, the area of low suitability habitats will surge from 99,083.6 km2 to 136,936.8 km2, marking a 38.2% increase. Moderate suitability habitats will also see significant growth, rising 88.2% from 90,305.6 km2 to 169,985.2 km2 under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. The trend for highly suitable habitats proves more complex: while the SSP1-2.6 scenario shows a 5.2% increase, the SSP5-8.5 scenario demonstrates a 36.5% decrease. This suggests that certain regions might still maintain relatively suitable environmental conditions under lower emission scenarios. Notably, all future climate scenarios indicate a reduction in unsuitable habitats, with the SSP5-8.5 scenario showing a 7.7% decrease.

Table 3.

Size of suitable habitat under different greenhouse gas emission pathways and rate of change relative to the current period.

4. Discussion

4.1. Distribution and Habitat Projections of Portunus trituberculatus Under Future Climate Scenarios

Portunus trituberculatus feeds on benthic crustaceans (such as shrimp, copepods), small fish, and organic debris, while also being preyed upon by large fish (such as grouper) and cephalopods (such as squid) [39]. This trophic cascade facilitates energy transfer from lower to higher trophic levels, playing a vital role in maintaining ecosystem stability. As an economically significant species, the sustainability of its fishery is crucial for the long-term viability of the fishing industry [40]. However, research on climate change impacts on the habitat distribution of Portunus trituberculatus remains limited. This study employs the Biomod2 species distribution model to evaluate potential habitat changes in the East Yellow Sea populations under climate change scenarios.

The final simulation results (Figure 4) show that Portunus trituberculatus is mainly distributed between north latitude 27–35.5° and east longitude 120–123.5°. As the longitude increases significantly, the suitability of the habitat shows a clear downward trend. The high suitability zones are distributed in the coastal waters along the Jiangsu coast, the Yangtze River estuary, the Hangzhou Bay, and the coastal waters near the Zhoushan Archipelago, which is consistent with the actual distribution area of Portunus trituberculatus [41].

The final projections (Figure 5) indicate that low-latitude regions are projected to become increasingly unsuitable for Portunus trituberculatus, while its suitable habitat is expected to expand toward higher latitudes. This projected migration trend aligns with the widely observed global pattern of poleward distribution shifts in marine species in response to climate warming potentially weakening the ecological functions of existing core spawning grounds (such as the Zhoushan Archipelago region). This habitat migration trend aligns with the movement patterns observed in multiple marine species [42,43,44].

Figure 5.

Predicted potential distribution of Portunus trituberculatus under the different SSP scenarios.

Despite some expansion in high-latitude regions, the Bohai Sea, as the geographical northern boundary of Portunus trituberculatus’s distribution, faces constraints on its northward migration potential due to its semi-enclosed marine environment. With summer water temperatures already approaching the species’ survival limit [45], projections under the SSP5-8.5 climate scenario suggest temperatures could exceed 28 °C by 2100. This temperature is critical as it surpasses the upper thermal tolerance limit established for Portunus trituberculatus through laboratory experiments [46]. Such conditions would likely trigger a dramatic increase in adult crab mortality due to heat stress, potentially turning the Bohai Sea into an ecological bottleneck for northward migration.

Mechanistic Links Between Key Variables and Crab Biology

The prominence of seabed temperature and salinity in our model is underpinned by direct physiological and ecological mechanisms. As an ectotherm, Portunus trituberculatus has a metabolic rate, growth, and reproductive success tightly regulated by temperature [47]. The projected northward shift in high-suitability areas reflects a migration towards its optimal thermal niche. Simultaneously, salinity is critical for osmoregulation; deviations from the optimal range impose energetic costs [48], diverting energy from growth and reproduction, as evidenced by reduced growth rates and gonadosomatic index under suboptimal salinities [49]. Furthermore, salinity gradients structure the distribution of its benthic prey. Thus, climate-driven changes in these parameters directly affect the crab’s energy budget and habitat quality, explaining the distribution shifts projected by our model.

4.2. Impact on Protection and Management of Portunus trituberculatus

The projected redistribution of suitable habitat for Portunus trituberculatus underscores the urgent need to evolve current conservation and fisheries management paradigms from static to dynamically adaptive frameworks. The core challenge lies in addressing the spatial mismatch that will arise between historical fishing grounds and future bioclimatically suitable areas [50]. To this end, our spatially explicit projections provide a scientific basis for preemptive and targeted management interventions.

Concretely, the foremost priority should be the spatial prioritization of management resources based on habitat trajectory [51]. This entails designating persistent high-suitability areas, such as the coastal waters of Jiangsu and the Yangtze River Estuary, as key climate adaptation zones for enhanced protection. Strengthening measures like habitat restoration and regulating bottom disturbances in these refugia can safeguard critical stock replenishment potential. Concurrently, in regions facing pronounced habitat contraction, such as the Zhoushan Archipelago waters, management must pivot towards enhanced ecological monitoring. Establishing sentinel monitoring programs to track population dynamics and environmental thresholds is essential for generating early warnings and understanding local-scale vulnerability.

These spatial priorities necessitate distinct, actionable strategies at the provincial level. For Jiangsu Province, the goal is to consolidate and protect its role as a critical climate refuge. Actionable measures include piloting climate-adaptive fishery management zones with effort controls, and implementing habitat enhancement projects such as oyster reef restoration. In contrast, Zhejiang Province must focus on adaptive transformation. Key actions involve implementing dynamic spatial fishing closures in areas of declining suitability, and exploring livelihood diversification, such as integrated multi-trophic aquaculture, to support fishing communities. Crucially, cross-provincial collaboration is essential to establish a joint resource assessment and management mechanism, ensuring coherent stewardship across the stock’s shifting range.

Building upon this spatially differentiated approach, it is equally critical to develop harvest strategies that are responsive to environmental change [52]. Static fishing quotas risk becoming progressively misaligned with a shifting resource base. Therefore, fisheries management should explore the development of a dynamic framework, where decisions on effort allocation or spatial access are periodically informed by updates to habitat suitability projections. Such a precautionary system would help prevent overfishing in deteriorating habitats while enabling sustainable harvest where conditions become newly favorable.

Furthermore, the effective implementation of these measures requires that habitat projections be mainstreamed into broader maritime governance [53]. Integrating our distribution maps into Marine Spatial Planning is vital to preemptively resolve potential conflicts between future fishing grounds, conservation priorities, and other ocean uses. Finally, given the transboundary nature of the projected poleward shift, which suggests potential stock exchanges towards the Korean Peninsula, fostering regional scientific and management cooperation emerges as a necessary step for future sustainable stewardship of the fishery.

4.3. Limitations and Future Perspectives

While this study provides a robust projection of potential habitat shifts for Portunus trituberculatus using an ensemble modelling approach, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, although the use of a 10-model ensemble inherently captures and reduces the uncertainty associated with any single algorithm, our projections represent a central tendency (mean or median). The variance among these individual model projections constitutes a key source of uncertainty that is not expressed as quantitative confidence intervals (e.g., error bars) in the reported area changes. Second, our projections are contingent upon the specific emission scenarios (SSPs) and the underlying global climate models used to generate future environmental layers. Different climate models can produce varying estimates of future temperature and salinity, leading to alternative distribution outcomes. Third, our SDMs framework primarily considers abiotic environmental factors. It does not explicitly incorporate critical biotic processes such as species interactions (competition, predation), dispersal limitations, or the direct impacts of fishing pressure, all of which can modulate the real-world distribution of the crab. Finally, the accuracy of our model is inherently tied to the quality and spatial completeness of the occurrence data used for calibration. Fourth, our projections primarily considered changes in physical habitat (temperature, salinity). While this captures the dominant signal of climate change for this species, future work could integrate projected changes in key biogeochemical variables, such as pH and dissolved oxygen from CMIP6 Earth System Models, to assess the compounded effects of ocean acidification and deoxygenation on Portunus trituberculatus and other benthic crustaceans. Fifth, our model considers abiotic factors as primary drivers. It does not explicitly incorporate dynamic biotic interactions (e.g., predation, competition) or future changes in fishing pressure, which can modulate realized distributions. Our projections thus depict abiotic potential rather than a forecast of absolute future abundance. Future advances could couple population dynamics models with high-resolution economic data to integrate these critical factors.

Future research could address these limitations by: (1) employing a full ensemble of multiple global climate models (GCMs) for each SSP to quantify climate projection uncertainty; (2) integrating dynamic population models that incorporate life-history parameters and fishing mortality; (3) including higher-resolution data on coastal geomorphology and localized anthropogenic stressors; and (4) applying more complex modelling frameworks that can account for species interactions. Despite these limitations, our study offers a critical first assessment using a state-of-the-art ensemble approach, and the identified trends provide a scientifically defensible basis for proactive climate adaptation in fisheries management.

5. Conclusions

This study employed an ensemble modeling approach to project the potential habitat shifts in Portunus trituberculatus under future climate change. While subject to the uncertainties inherent in climate projections and model assumptions, our analyses consistently indicate a strong likelihood of poleward habitat redistribution. The key drivers are identified as bottom temperature and salinity, with chlorophyll-a concentration playing a secondary role. By mid-to-late century, a contraction of high-suitability areas in current southern core habitats and an expansion of moderate-suitability areas northward are projected, with the Bohai Sea posing a potential thermal bottleneck. To navigate these uncertain but consequential changes, we advocate for the integration of dynamic, climate-informed habitat suitability maps into marine spatial planning and the development of adaptive fishery management policies that can be adjusted as scientific understanding and climate impacts evolve.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S.; methodology, F.S., Y.Z., S.W. and G.X.; validation, F.S. and S.Y.; investigation, H.G., H.Z., Z.L. and J.Z.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, H.Z., H.G. and L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program “Production Process and Driving Mechanisms of Important Fishery Resources in the East China Sea”: 2023YFD2401901; National Key R&D Program “Blue granary scientific and technological innovation” Key special topics:2020YFD0900804; Zhejiang Province Science and Technology Special Project: HYS-CZ-202502.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, B.; Yu, Y.; Wang, T.; Xu, N.; Fan, X.; Penuelas, J.; Fu, Z.; Deng, Y.; et al. Global biogeography of microbes driving ocean ecological status under climate change. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Lü, B.; Li, R.; Zhu, A.; Wu, C. A preliminary analysis of fishery resource exhaustion in the context of biodiversity decline. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2016, 59, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Bao, M.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Du, J.; Gao, Y.; Hu, L.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Qin, G.; et al. Advances of marine biogeography in China: Species distribution model and its applications. Biodivers. Sci. 2024, 32, 23453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarling, G.A.; Ward, P.; Thorpe, S.E. Spatial distributions of Southern Ocean mesozooplankton communities have been resilient to long-term surface warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, C.; Boughey, K.; Hawkins, C.; Reveley, S.; Spake, R.; Williams, C.; Altringham, J. A sequential multi-level framework to improve habitat suitability modelling. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 1001–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varo-Cruz, N.; Bermejo, J.A.; Calabuig, P.; Cejudo, D.; Godley, B.J.; Lopez-Jurado, L.F.; Pikesley, S.K.; Witt, M.J.; Hawkes, L.A. New findings about the spatial and temporal use of the Eastern Atlantic Ocean by large juvenile loggerhead turtles. Divers. Distrib. 2016, 22, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Wei, Q.; Du, H.; Li, J.; Ye, H. Are river protected areas sufficient for fish conservation? Implications from large-scale hydroacoustic surveys in the middle reach of the Yangtze River. BMC Ecol. 2019, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, C.Y.; Yang, D.G.; Du, H.; Wei, Q.W.; Kang, M. Spatial distribution and habitat choice of adult Chinese sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis Gray, 1835) downstream of Gezhouba Dam, Yangtze River, China. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2014, 30, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S.; Sommer, U.; Sihra, J.K.; Thorne, M.A.; Morley, S.A.; King, M.; Viant, M.R.; Peck, L.S. Biodiversity in marine invertebrate responses to acute warming revealed by a comparative multi-omics approach. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qun, L.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.Y.; Wu, Q. Assessment of ecosystem energy flow and carrying capacity of swimming crab enhancement in the Yellow River estuary and adjacent waters. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 26, 3523–3531. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Sun, J.; Hurtado, L.A. Genetic differentiation of Portunus trituberculatus, the world’s largest crab fishery, among its three main fishing areas. Fish. Res. 2013, 148, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Dong, T.W.; Tu, Z.; Xin, J.F.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, S.J.; Wang, P.L. Review and consideration on Portunus trituberculatus stock enhancement in Shandong Province. Fish. Inf. Strateg. 2018, 33, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.P.; Zhang, G.G.; Wang, T.T.; Li, M.; Ren, Z.H.; Jiang, W.L.; Lv, Z.B.; Liu, D. Community structure and seasonal variation of demersal nekton in the eastern waters of Laizhou Bay. Mar. Fish. 2024, 46, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhong, L.; Gao, T. Preliminary study on spatial distribution pattern of fish in Zhoushan and its adjacent waters based on environmental DNA metabarcoding. J. Fish. China 2024, 48, 089311-1–089311-14. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.J.; Tang, X.Y.; Yan, X.J.; Song, W.H.; Zhou, Y.D.; Zhang, H.L.; Jiang, R.J.; Yang, J.; Jiang, T. Speculation of migration routes of Larimichthys crocea in the East China Sea based on otolith microchemistry. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2023, 45, 128–140. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Sun, M.; Xu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Chen, Z.; Qiu, Y. Climate-induced small pelagic fish blooms in an overexploited marine ecosystem of the South China Sea. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.D. Stock assessment and management decision analysis of Portunus trituberculatus inhabiting Northern East China Sea. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2023, 53, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Doughty, C.L.; Gu, H.; Ambrose, R.F.; Stein, E.D.; Sloane, E.B.; Martinez, M.; Cavanaugh, K.C. Climate drivers and human impacts shape 35-year trends of coastal wetland health and composition in an urban region. Ecosphere 2024, 15, e4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Feng, G.; Shao, J.; Yang, G.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, F.; Geng, Z.; Li, X.; Tan, Q. Spatial-temporal distribution of resources and the relationship between environmental factors of Portulus trituberculus in the Yangtze River Estuary. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 210, 107275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shan, X.; Gorfine, H.; Dai, F.; Wu, Q.; Yang, T.; Shi, Y.; Jin, X. Ensemble projections of fish distribution in response to climate changes in the Yellow and Bohai Seas, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, M.; Ouled-Cheikh, J.; Julia, L.; Fuster-Alonso, A.; March, D.; Ramírez, F.; Cardona, L.; Coll, M. Fish and tips: Historical and projected changes in commercial fish species’ habitat suitability in the Southern Hemisphere. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snead, A.A.; Earley, R.L. Predicting the in-between: Present and future habitat suitability of an intertidal euryhaline fish. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 68, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, P.; Jácome, G.; Kim, S.Y.; Nam, K.; Yoo, C. Population response modeling and habitat suitability of Cobitis choii fish species in South Korea for climate change adaptation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 189, 109949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.Q.; Xu, K.D.; Wang, H.X.; Zhou, Y.D. Spatial and temporal distribution of Portunus trituberculatus and its influencing factors in Ruian sea area, Zhejiang Province. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2024, 46, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, X. Impacts of shellfish aquaculture on the ecological carrying capacity of Portunus trituberculatus in Laizhou Bay. Aquac. Int. 2025, 33, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Sui, J.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B. Potential effects of climate change on the habitat suitability of macrobenthos in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 174, 113238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.brtuev (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shao, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, X. Habitat distribution and driving mechanisms of Portunus trituberculatus across different life history stages in the southern Bohai Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 210, 107347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GMED Environment Datasets Download. Available online: http://gmed.auckland.ac.nz (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Bio-ORACLE Environment Datasets Download. Available online: https://www.bio-oracle.org/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Schickele, A.; Leroy, B.; Beaugrand, G.; Goberville, E.; Hattab, T.; Francour, P.; Raybaud, V. Modelling European small pelagic fish distribution: Methodological insights. Ecol. Modell. 2020, 416, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Lafourcade, B.; Engler, R.; Araújo, M.B. BIOMOD—A platform for ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Ecography 2009, 32, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shan, X.; Ovando, D.; Yang, T.; Dai, F.; Jin, X. Predicting current and future global distribution of black rockfish (Sebastes schlegelii) under changing climate. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 128, 107799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, O.; Tsoar, A.; Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: Prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 43, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swets, J.A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988, 240, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Qin, F.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, W.; Duan, H.; Li, M. Forecast of potential suitable areas for forest resources in Inner Mongolia under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 245 scenario. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, H.; Ding, X.; Jo, D.; Li, K. Implications of RCP emissions on future concentration and direct radiative forcing of secondary organic aerosol over China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640, 1187–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Han, X.; Han, Z. Effects of climate change on the potential habitat distribution of swimming crab Portunus trituberculatus under the species distribution model. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2022, 40, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Yuan, W.; Ma, Y.J.; Zu, K.W.; Zhang, H. Evaluation of project to enhance the ecological carrying capacity of swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus) in Haizhou Bay. J. Hydroecol. 2022, 43, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.; Wang, F.; Zhang, D.; Yu, L.; Pu, W.; Xu, X.; Xie, Y. Assessment of the carrying capacity of integrated pond aquaculture of Portunus trituberculatus at the ecosystem level. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 747891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Song, H.; Yao, G.; Lu, H. Composition and distribution of economic crab species in the East China Sea. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2006, 37, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, A.L.; Low, P.J.; Ellis, J.R.; Reynolds, J.D. Climate change and distribution shifts in marine fishes. Science 2005, 308, 1912–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comte, L.; Buisson, L.; Daufresne, M.; Grenouillet, G. Climate-induced changes in the distribution of freshwater fish: Observed and predicted trends. Freshw. Biol. 2013, 58, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Mu, X.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y. Ensemble predictions of high trophic-level fish distribution and species association in response to climate change in the coastal waters of China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 214, 117800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, X.; Xiong, X. Distributions and seasonal changes of water temperature in the Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea and East China Sea. Adv. Mar. Sci. 2013, 31, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, F.; Dong, S. Hypothermal effects on survival, energy homeostasis and expression of energy-related genes of swimming crabs Portunus trituberculatus during air exposure. J. Therm. Biol. 2016, 60, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, L.; Dong, S. Responses of metabolism and haemolymph ions of swimming crab Portunus trituberculatus to thermal stresses: A comparative study between air and water. Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 2989–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; An, Y.; Li, R.; Mu, C.; Wang, C. Strategy of metabolic phenotype modulation in Portunus trituberculatus exposed to low salinity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3496–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.W.L.; Watson, R.; Pauly, D. Signature of ocean warming in global fisheries catch. Nature 2013, 497, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Shan, X.; Jin, X.; Gorfine, H.; Yang, T.; Li, Z. Evaluating spatio-temporal dynamics of multiple fisheries-targeted populations simultaneously: A case study of the Bohai Sea ecosystem in China. Ecol. Modell. 2020, 422, 108987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.; Lavorel, S. Niche theory improves understanding of associations between ecosystem services. One Earth 2023, 6, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, F.; Cánovas, F. Predicting climate change impacts on marine fisheries, biodiversity and economy in the Canary/Iberia current upwelling system. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 384, 125537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, H.A.; Hansen, C.; Howell, D.; Olsen, E. A review of applications evaluating fisheries management scenarios through marine ecosystem models. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2021, 29, 800–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.