Abstract

A theoretical model of the interaction between a following current and a semi-infinite floating ice sheet under compressive stress near a vertical impermeable wall is developed, within the scope of linear water wave theory, to study the hydroelastic behavior. The conceptual framework defining the buoyant ice structure incorporates the tenets of elastic beam theory. The associated fluid dynamics are governed by strict adherence to the potential flow paradigm. To resolve the undetermined parameters appearing in the Fourier series decomposition of the potential functions, investigators systematically apply higher-order criteria detailing the coupling relationships between modes. The current results are compared with a specific case of results available in the literature, and the convergence analysis of the analytical solution is made for computational accuracy. Further, the free edge conditions are applied at the edge of the floating ice sheet, and the effects of current speed, compressive stress, the thickness of the ice sheet, flexural rigidity, water depth on the strain, displacements, reflection wave amplitude, and the horizontal force on the rigid vertical wall are analyzed in detail. It is found that the higher values of the following current heighten the strain, displacements, reflection amplitude, and force on the wall. The study’s outcomes are considered to benefit not just cold region design applications but also the engineering of resilient floating structures for oceanic and offshore environments, and to the design of marine structures.

1. Introduction

The massive sheets of ocean ice in the Arctic and Antarctic are used as important natural platforms. They are key for travel across the ice, for building short-term airstrips, and for aiding other transportation needs in these extreme marine environments [1,2,3,4]. On the other hand, when hydrodynamic forces—specifically combined swells and currents—impinge upon an ice-covered sea, the resulting wave propagation is fundamentally dictated by the structural stiffness inherent to the ice sheet surface [5]. The ice sheet possesses a significantly large horizontal dimension, allowing it to be approximated as infinite for many practical cases. Due to the continuous excitation of a small-amplitude wave–current, the overall performance characteristics of the component are overwhelmingly driven by recoverable deformation.

Therefore, the mechanical response of expansive floating ice to the combined forcing of waves and currents is critically governed by the principles of hydroelasticity. Hence, it is necessary to gain deeper insight into the impact of wave–current–/structure/ice interactions [6]. The present investigation addresses a problem in which a vertical wall is placed near a compressed FIS with semi-infinite extent and its interaction with a following current (FC) application to breakwater in the Arctic region. A detailed review of the latest advancements of the nonlinear hydroelastic models associated with sea ice interactions with floating ice sheets and ship structures [3] application to Arctic and offshore engineering is presented. A 2D FEM-DEM is applied to determine the maximum ice load values that occur when sea ice breaks against a sloped marine structure [7]. Ni et al. [8] provided a review that presented the ice deformation, focusing on the defining attributes of waves driven by combined bending and gravitational forces.

To address some important aspects of floating sea ice interaction with marine structures under varying sea ice properties, a significant amount of work has been conducted by many researchers using numerical simulations or numerical methodologies. An experimental study on the ice–structure interaction for offshore wind turbines with a monopile foundation is presented in [9]. Shi et al. [10] evaluated how the specific physical configuration and thermal condition of the ice structure modulated the dynamics of the collision event based on the elastic-plastic iceberg material model. Tsuprik et al. [11] presented a mathematical model of sea ice failure by assessing the mechanics governing the interaction between traveling sea ice masses and fixed marine architecture. Ni et al. [12] studied the ice deformation based on the propagation of elastic-gravitational waves through a full ice cover, resulting from the dynamic application of a traveling object. Song et al. [13] utilized an established multi-yield-surface plasticity approach to simulate stress states and fracture initiation in ice. This model was subsequently applied to predict the mechanical failure of three distinct forms.

A new physical modeling approach was adopted to examine the wave-ice interaction for determining an elastic stiffness in [14]. Yiew et al. [15] carried out a scaled experiment to analyze wave damping and the scattering of wave energy when encountering diverse icy environments. The wave interaction with a floating structure close to the marginal ice zone in 2D is examined, where the linear velocity potential theory and the thin elastic plate are utilized for fluid flow and the analysis of ice sheet deflection, respectively [16]. A numerical simulation of a very large floating interconnected rectangular structure under current and wind [17], along with theoretical floating flexible rectangular [18] and floating interconnected rectangular model [19] subjected to current using Timoshenko-Mindlin Beam theory, are presented, during the execution of a study focused on how the velocity of the fluid flow dictates the resultant stresses within the physical infrastructure and the parametric metrics characterizing the generated wave system. Korobkin and Khabakhpasheva [20] studied the response of floating ice using a model that accounts for both ice properties and its interaction with the underlying water. Van den Berg et al. [21] analyzed ice forces and structural response on a vertical cylindrical pile using ice basin test data. The impact response of an upright ocean structure to the forces exerted by a drifting ice floe was numerically simulated and is documented in [22]. A review of ice–structure modeling, focused on predicting interactions between ships or floating platforms with broken ice fields, is conducted [23]. Using a deployed array of ice-drifting buoys, Hutchings et al. [24] studied the temporal and spatial scaling of sea ice deformation. A review focusing on the mechanical failure and discontinuous nature of sea ice using the DEM approach is conducted in [25], while Sayeed et al. [26] focused on the review of hydrodynamic influence and motion statistics of large, discrete glacial ice features (icebergs) impacting marine structures.

Huang et al. [27] used the Open-FOAM solver to model the hydroelastic response of a large ice sheet under wave actions. Under the potential flow hydroelastic model and nonlinear numerical FE solver, Hartmann et al. [28] studied the ice sheet’s bending and deformation under the consideration of the Kirchhoff–Love theory applied to model the behavior of the linear elastic plate. Tavakoli et al. [29] presented a viscoelastic wave–ice interactions model using the fluid–solid dynamic model. Xue et al. [30] utilized a hybrid method to analyze the hydroelastic response of a floating ice sheet due to pressure under constant water depth and potential linear flow theory. Huang and Thomas [31] adopted a 3D CFD model to analyze the nonlinear interaction between the regular waves and a circular ice floe.

Staroszczyk [32] analyzed the sea ice–structure interaction based on numerical simulation under thermal expansion, in which sea ice was modeled as a rectangular plate with uniform thickness and axial compressive force. Hu et al. [33] proposed a fluid structure interaction Scheme to model the collision dynamics impact of ice and water by employing a penalty function technique. Sinsabvarodom et al. [34] detailed established probabilistic methodologies for sea ice used to predict the load uncertainty impacting various offshore structures. Using the discrete element method and physical modeling, the forces and effects resulting from the contact between a cylindrical object and ice fragments were studied [35]. The radiation of waves from a submerged structure covered with ice at the surface was studied in 3D under deep-water conditions [36]. A virtual buoy was created based on the numerical WW3 to study the wave propagation under ice covers [37]. The DEM numerical methodology is used to investigate the icebreaking performance of a single leg Jacket platform under different ice conditions [38]. The local ice pressure magnitude and its dependency on various factors were studied using experimental tests and theoretical analysis [39].

Squire [40] focused on the hydroelastic coupling relevant to sea ice mechanics and the behavior of VLFS. The wave quantities were investigated by utilizing two methods from the framework of generalized Polynomial Chaos (gPC) in [41]. Timco and Weeks [42] extensively reviewed sea ice engineering properties concerning personnel and environmental safety. Bennetts et al. [43] presented a 3D numerical model to study the wave energy dissipation in the marginal ice zone by simulating how waves are scattered by arrays of large elastic thin plates.

Based on the assumption of linear wave theory and thin plate theory, a considerable amount of work when accounting for all components of the analysis of floating ice sheet in different conditions has been carried out, which is discussed below. Brocklehurst et al. [44] analyzed the behavior of the flexural gravity waves over an ice sheet analytically, considering the clamped condition. Maiti and Mandal [45] addressed the 2D wave scattering phenomenon in which a thin, uniform ice cover interacts with a submerged rigid barrier. Korobkin et al. [46] examined the behavior of hydroelastic waves that develop within an ice-covered channel under the assumption of linear progressive waves and the linear elastic plate equation. Lu et al. [47] developed a coupled theoretical model between the ice and wide sloping structure to study the impact of ice breaking under spatial and temporal variations.

Zhao et al. [48] presented a brief overview of the mathematical framework and wave quantities associated with different ice characteristics. Hegarty and Squire [49] analyzed the response of a compliant, floating sea ice floe when subjected to the waves of large-amplitudes, and the solution was obtained using a perturbation expansion, boundary-integral method, and the results were compared with eigenfunction matching methods. Zhang and Zhao [50] studied the wave quantities by a finite ice cover under a viscoelastic sea ice model using the two-mode approximate method. Using an elastic plate model for the ice cover, Batyaev and Khabakhpasheva [51] examined the behavior of linear hydroelastic waves propagating through a channel. Qiu et al. [52] provided a theoretical solution for the steady-state response of a freely floating ice sheet to a moving load based on integral transforms and asymptotic methods. Wan et al. [53] presented the hydrodynamic analysis of an ice-covered domain based on a hybrid method that combines the BIEM and eigenfunction expansions.

Zhang et al. [54] studied the hydrodynamics of a floating body in the vicinity of a semi-infinite ice sheet using the eigenfunction expansions in conjunction with Green’s identity, analyzed within the framework of linear wave theory and the Kirchhoff–Love plate approximations. Wang et al. [55] studied the 3D elastic sea ice scattering model in irregular waves using thin plate theory. The solution of the nonlinear water wave equations with an ice sheet is presented based on BIEM, while different types of responses were analyzed [56]. Under nonlinear incident waves, Kostikov et al. [57] employed a combined Green–Naghdi and thin plate model to accurately predict the current-driven drift motion of an FIS.

In recent years, there have been a considerable amount of works carried out, specifically the hydroelastic analysis of floating structures [58,59], and floating and submerged structures based on thin elastic plate theory and linear water wave theory using an analytical approach [60,61,62]. Korobkin et al. [63] derived a theoretical framework for the 2D, linear, and unsteady hydroelastic interaction involving a moving vertical wall with spring-like constraints under the action of surface waves. A revised theoretical model based on shallow-water approximation is presented to analyze wave scattering by regions of randomly fluctuating water depth and areas covered by fragmented floating ice of irregular thickness [64]. A numerical framework is used to simulate the nonlinear propagation of waves as they traverse along fragmented sea ice fields [65]. The 3D complex phenomenon of wave propagation of an FIS with variable ice thickness and water depth is investigated in [66]. A viscoelastic model is developed to analyze the generation of gravity waves in different types of ice cover with finite thickness [67]. A review of the recently established theoretical and numerical techniques for assessing the uncertainties and sensitivities inherent in the hydrodynamic and hydroelastic behavior of floating structures. [68].

Beyond their role in quantifying the fluid structure interaction dynamics of mega-scale marine platforms, flexible plate models with unrestrained boundaries are a standard analytical tool for researchers investigating the influence of surface gravity waves on sea ice across high-latitude zones [69]. Floating ice sheets experience compressive stress from a variety of natural factors, including thermal expansion and contraction, and frictional forces exerted by wind and water currents underneath, as documented in [70]. The impact of surface waves on compressed ice edges in a constant-depth basin was analyzed in [71] by employing the conjugate gradient algorithm. The behavior of an ice sheet that is subjected to compression while it floats is investigated, specifically in relation to a moving load applied to the ice [72], which provided a study on the synergy between very large floating structures and sea ice research. Mohapatra et al. [73] utilized the BIEM to analyze the phenomenon of wave diffraction around a floating elastic plate under the influence of compressive force, and the critical compressive force was investigated and analyzed based on the phase and group velocities.

Although research on sea ice–structure interactions has progressed, existing literature still lacks a comprehensive theoretical model. This gap is particularly evident in the analysis of hydroelastic flexural gravity waves on an FIS with a vertical wall, where the inclusion of current velocity in both the formulation and solution techniques for current effects remains inadequately addressed, impacting its application to maritime activities. This paper, therefore, focuses on developing an FIS theoretical model for hydroelastic waves to provide solutions, the analysis of which will offer valuable insights into the current literature.

The sections of this manuscript are organized in the following manner. The theoretical framework is established in Section 2, where the problem is formulated based on the principles of linear wave theory, with the underlying physical phenomenon expressed mathematically through a model of flexural gravity wave scattering by a semi-infinite FIS with compressive force near an impermeable vertical wall in the presence of FC. In Section 3, the solution method, leveraging eigenfunction expansion and mode coupling relations, is discussed and utilized. In Section 4, the comparison results, convergence analysis, and impact of FC, along with the parameters of the FIS model on the strain, displacements, and reflection wave amplitude by a vertical rigid wall, are discussed. It is observed that the current speed significantly influences the strain, displacements, and reflection amplitude in addition to the horizontal force applied to the wall. At the end, the concluding remarks and limitations are highlighted in Section 5.

2. Model Definition

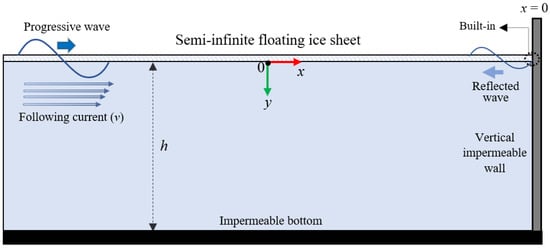

The underlying assumptions of the mathematical structure dictate the use of a standard Cartesian coordinate system, where the abscissa (-axis) is defined horizontally. The ordinate (-axis), conversely, features an unconventional polarity, establishing positive movement as an increase in the downward vertical direction. The physical configuration includes an impermeable vertical barrier positioned at . To its left, an aquatic domain stretches indefinitely towards negative -values ), maintaining a constant depth ‘’ (from to ). This water body’s upper interface is completely overlain by a semi-infinite ice sheet, which has an infinitesimally small thickness ‘’ (illustrated in Figure 1). Consistent with the framework of linear water wave theory, a uniform current is prescribed to flow at a constant velocity , and is oriented in the positive -direction, aligning with the direction of wave propagation. Under the assumption of the linearized water wave theory, the fluid is considered to be incompressible, inviscid, and the motion is irrotational and time harmonic with angular frequency ω. There exists a velocity potential associated with FC, which is expressed as:

where We can express as . In this expression, Re stands for the real part, and represents the spatial potential. Consequently, the scalar potential field is mathematically governed by the two-dimensional constraints intrinsic to the Laplace differential equation as:

where .

Figure 1.

A sketch of the Boundary Value Problem under the following current.

The seabed state, taken precisely at the level , implies the relationship:

As structural movement drives changes in fluid patterns, a linear kinematic condition is formulated to account for the effect of FC (). This condition is given by:

The thin ice sheet on the upper surface is treated as a component of the water surface, though its distinct physical characteristics are governed by its structural stiffness. Under compression and following the current, the dynamic boundary condition satisfies as:

where .

Eliminating the ice sheet deformation from Equations (4) and (5), the linearized enclosed BC, via is determined as:

The fifth-order BC on the FIS via can be obtained by combining the kinetical, dynamic boundary conditions along with Equation (6) as:

where , , and .

This may highlight that if we set and in Equation (7), the reduced expression will be the same as in Equation (3a) as previously found in [5].

The BC on the vertical impermeable wall can be provided as:

The far-field BC adheres to the following mathematical conditions:

where with the parameters and are the fixed scalar magnitudes corresponding to the progressive wave components traveling along the negative and positive x-axes, respectively, while the quantity designates the spatial frequency (wave number) intrinsic to the progressive flexural gravity waves.

The free edge at leads to the following mathematical conditions:

The stipulations for a built-in or fixed edge condition necessitate that the displacement and the gradient of deflection are nullified at , and can be expressed as:

3. Solution Technique

Utilizing the Fourier expansion formulae, , satisfies Equations (2), (9) and (10) and can be formulated as:

where , being the same as defined in Equation (9), and the expression for , for is obtained by replacing with in . In addition, , for .

The eigenvalues and satisfy the dispersion relations as:

for refer to the real root and

contain four complex roots, but due to the boundedness of the series solution, only two complex roots are considered in the expansion formula (12) of the form for . On the other hand, for there are infinitely many imaginary roots of the form . It is imperative to recognize that if we set compression and , then the resultant will be consistent as previously obtained in [5]. satisfy the following orthogonal mode-coupling relation as:

where .

Using (13), Equation (8), and edge condition (10), the coefficients , are determined as:

The ice sheet edge condition, detailed in Equation (10), allows for the determination of the two unknown parameters, and . Applying the ice sheet edge condition (10) as in Equation (12), and replacing from Equation (14), results in:

Solving Equations (15) and (16), one can obtain:

where, to successfully determine the values of the coefficients and , the infinite mathematical progression detailed in Expressions (15) and (16) must be curtailed, utilizing only a finite set of components for the summation.

NB: It should be noted that, at and compression in Equations (15) and (16), the reduced expressions will be the same as in [5].

The surface strain for the flexural gravity waves along the FIS at can be computed by the following formula:

It may be mentioned that although the underlying mathematical framework is fully capable of modeling both co-directional (following) and contra-directional (opposing) interactions between currents and waves, the findings presented here are confined solely to the co-directional scenario. This strategic limitation serves to proactively bypass wave blocking, an adverse physical condition exclusive to flow regimes featuring opposing currents which is crucial to exclude from the analysis.

4. Quantified Outcomes and Their Interpretive Analysis

By analyzing the numerical values of reflection amplitude for different current speeds with increasing the number of terms () in the series solution along with the range of parametric values provided in Table 1, we demonstrate the numerical accuracy of the analytical results with and water density in Table 2. Further, it may be noted that the structural parameters provided in Table 1, especially a small thickness of the FIS, along with other parametric values, were selected to achieve computational accuracy in the numerical results relative to the analytical solution.

Table 1.

FIS key elements of the model.

Table 2.

Demonstration of convergence for various .

The numerical simulations derived from the analytical solution were executed using MATLAB R2023b (64-bit, Windows x64) on a desktop workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7-4790 CPU running at 3.60 GHz and boasting 16 GB of memory (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The time required to simulate a single case usually falls within the 8–10 min range.

4.1. Convergence of the Present Solution and Validation with Literature

Here, the infinite series sums (11) associated with the reflection amplitude is bounded such that it incorporates a maximum of elements to determine the coefficients ‘’ and ‘’. An analysis of reflection wave amplitudes () in Table 2, considering increasing and different current speed values, confirms their computational accuracy. Table 2 shows that the values are accurate to three decimal places for . Consequently, to maintain computational accuracy.

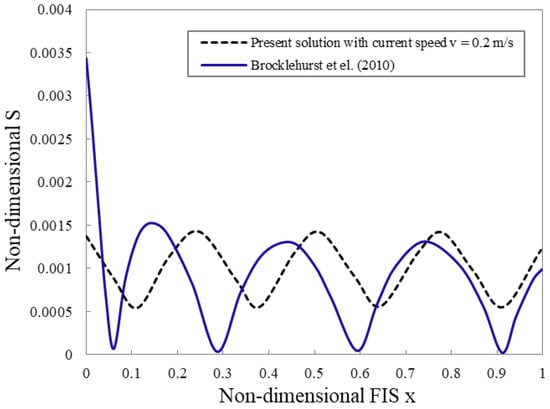

Figure 2 illustrates a comparison of the non-dimensional strain () along the non-dimensional length () of the FIS between the present solution under current loading and the results of [44]. For this comparison, the physical parameters are the same as in [44]. Overall, the two curves exhibit a qualitatively similar oscillatory pattern. However, the inclusion of current in the present model leads to noticeable changes in the phase of the strain response. Specifically, the present solution shows slightly reduced strain amplitudes and a phase shift relative to the no-current case in [44], indicating that the presence of current alters the hydrodynamic pressure distribution and modifies the FIS deformation characteristics.

Figure 2.

Comparison of non-dimensional strain () from the current solution for a fixed impermeable vertical wall with built-in edge against the findings of [44].

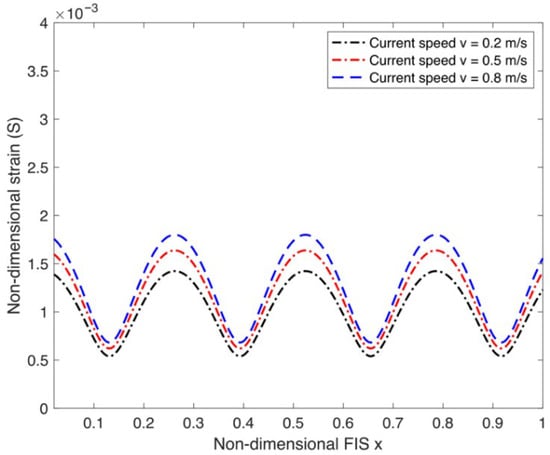

4.2. Impact of Current Speed and FIS Key Elements on Strain Along FIS

Figure 3 effectively demonstrates that in the present model, increasing the current speed significantly increases the magnitude of strain (S) over the length (x) of the FIS. This critical observation is primarily due to the exponential increase in the fluid excitation force imparted by the flow onto the FIS, highlighting the crucial role of current as a dominant and indispensable environmental parameter for accurately predicting the hydroelastic response of the FIS. This necessity is vital for applications such as assessing ice sheet stability and predicting ice-induced loading on coastal or offshore structures.

Figure 3.

Strain variation as a function of different current speeds v.

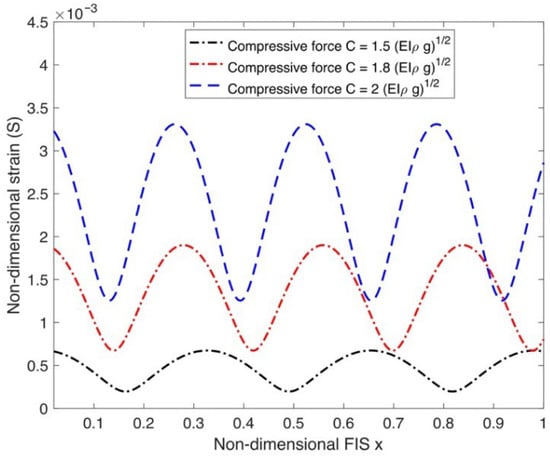

Figure 4 plots how the non-dimensional strain of the FIS changes over its non-dimensional length for different compressive forces (). Increasing the magnitude of the compressive force leads to a significant amplification of the dynamic strain amplitude experienced by the FIS. The compressive force effectively reduces the flexural rigidity of the FIS, making it more susceptible to dynamic excitation loads like waves and currents.

Figure 4.

Strain variation as a function of different compressive forces .

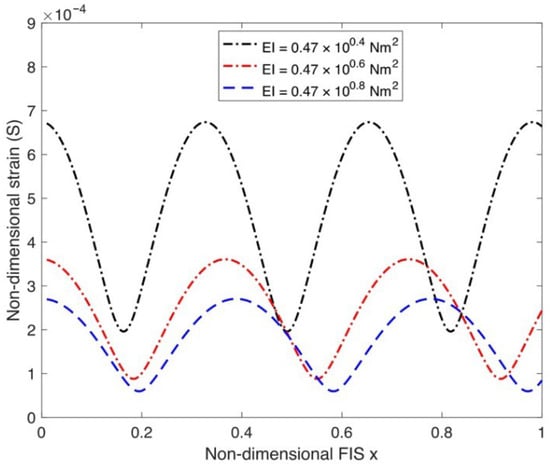

Figure 5 illustrates an inverse relationship between the non-dimensional strain and the flexural rigidity of the FIS. For the given non-dimensional length, an increase in the results in a substantial decrease in the measured strain.. Essentially, the ice sheet’s higher flexural rigidity successfully mitigates the development of large non-dimensional strains along its length, thereby enhancing the integrity of the FIS.

Figure 5.

Strain variation as a function of different flexural rigidities .

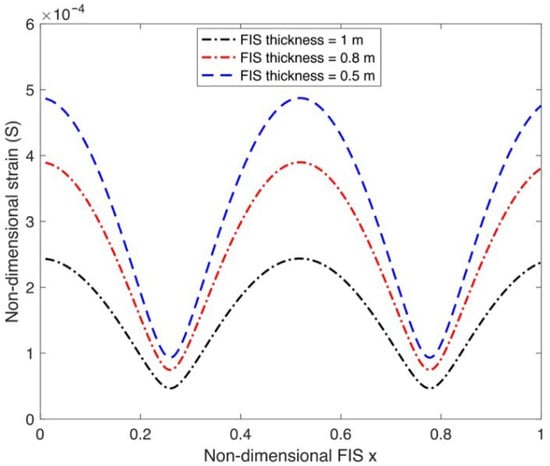

Figure 6 illustrates the strain along the FIS for different . The results confirm that thicker ice sheets are more rigid and are therefore better able to resist the applied wave–current load, resulting in less strain. Increasing the FIS thickness raises both the bending moment and the effective moment of inertia. In contrast, a thin FIS has much lower flexural rigidity and thus responds more readily to external loads. Its reduced rigidity allows wave and current loads to induce larger deflections and higher strain concentrations. These elevated strain levels make thin ice more vulnerable to mechanical failure, which magnifies tensile stresses at the ice surface, increasing the likelihood of crack initiation and propagation, leading to fracture or complete breakup when subjected to strong hydroelastic wave–current interactions.

Figure 6.

Strain variation as a function of different structural thicknesses .

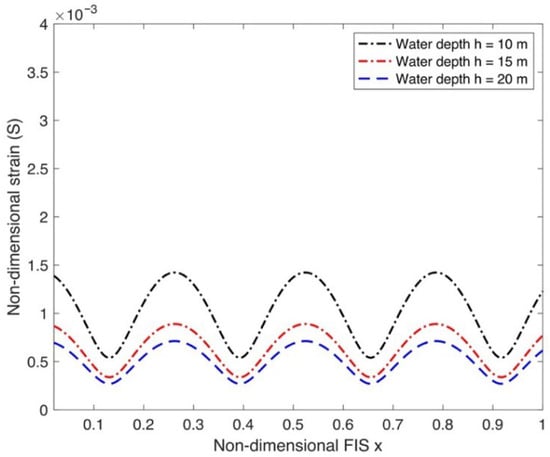

From Figure 7, observations demonstrate that for deeper water, the amplitude of the non-dimensional strain decreases. Specifically, the highest strain values occur for the shallowest case (), while the lowest correspond to the deepest case (). As in shallower water, the velocity field beneath the FIS is constrained by the seabed, significantly increasing the hydrodynamic pressure and leading to a stronger interaction between the wave–current and the FIS.

Figure 7.

Strain variation as a function of different water depths h.

4.3. Effect of Physical and FIS Parameters on Displacement Along FIS

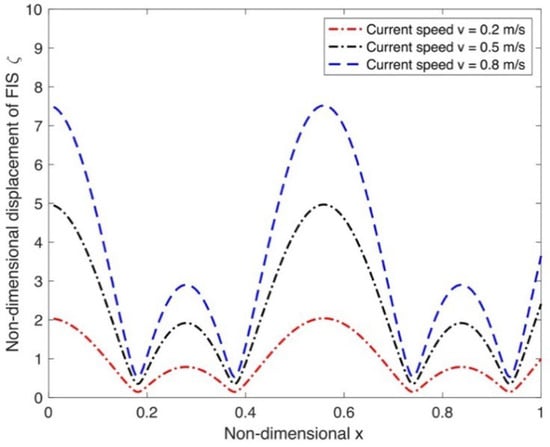

Figure 8 shows the impact of current speed on the FIS displacements against non-dimensional length and using the designated values for each parameter, as enumerated in Table 1. As the current speed increases, the magnitude of the non-dimensional displacement along the non-dimensional length of the FIS increases significantly. Higher current speed intensifies the hydrodynamic excitation acting on the FIS, thereby amplifying its hydroelastic response. This behavior highlights the sensitivity of the FIS to current-induced loading and demonstrates that the current plays a dominant and indeed indispensable role. Accurately capturing its influence is therefore essential for precise prediction and reliable assessment of the overall hydroelastic performance.

Figure 8.

Displacement variation as a function of different current speeds v.

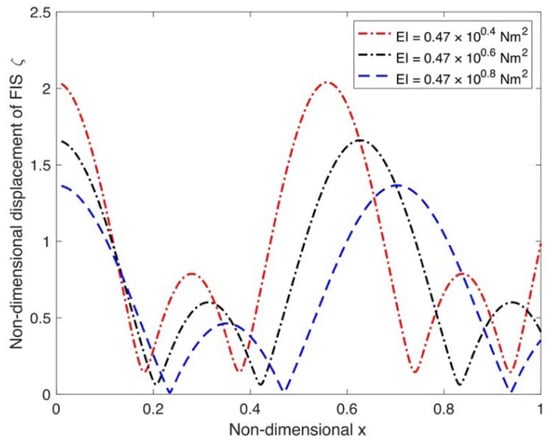

Figure 9 shows the non-dimensional displacements for various versus the non-dimensional length of FIS, with other parametric values being the same as mentioned in Table 1. It is observed that with the increase in the , the displacement decreases since the ice sheet rigidity becomes higher. The same phenomenon is observed in Figure 5 for strain.

Figure 9.

Displacement variation as a function of different rigidities .

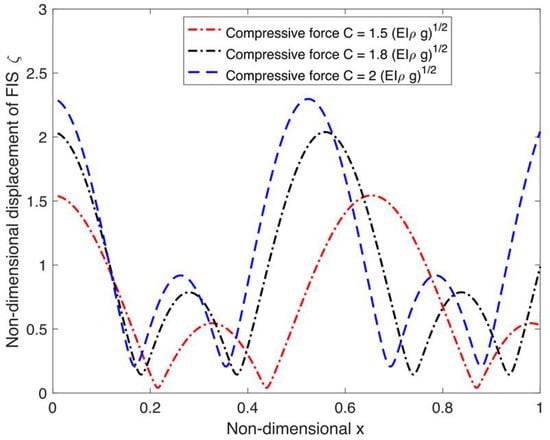

Figure 10 illustrates the variation of the non-dimensional displacement of the FIS along the non-dimensional length for various values of . It is evident that the magnitude and spatial pattern of the displacement are influenced by the applied compressive force. As increases, the amplitude of the displacement also increases. This trend suggests that higher compressive loads promote larger displacements of the FIS and that the compressive force has a destabilizing effect on the FIS.

Figure 10.

Displacement variation as a function of different compressions .

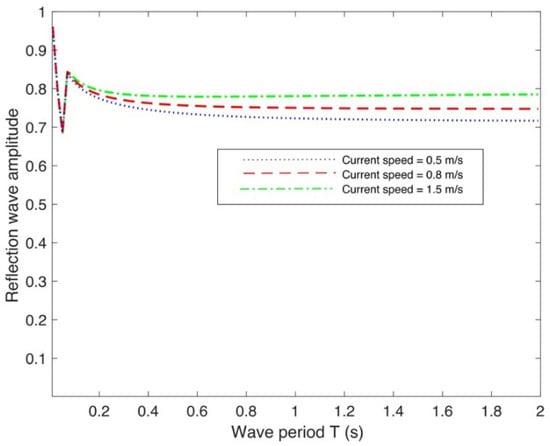

4.4. Effect of Current Speed and FIS Parameters on Reflection Wave Amplitude

In Figure 11, the differences in reflection wave amplitude for lower values of wave period for various current speeds generate a resonant pattern. Observations indicate that the magnitude of the reflected wave increases with flow velocity, with this growth becoming substantial for longer wave periods. As the current speed increases, the wave–current interaction intensifies for longer wave periods, increasing the dynamic pressure at the FIS edge boundary.

Figure 11.

Effect of FIS on the reflection wave amplitude for different current speeds v.

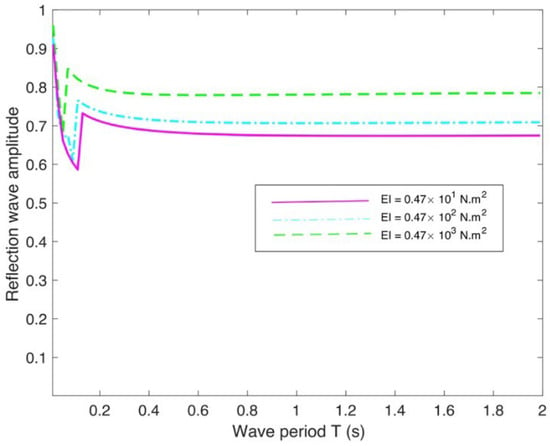

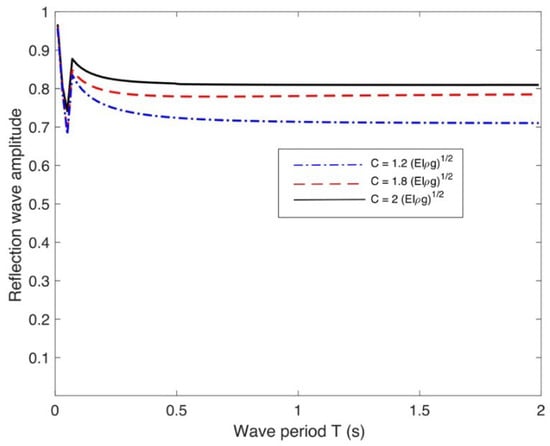

Figure 12 elucidates the relationship between flexural rigidity () and wave reflection amplitude () as a function of wave period (), maintaining a constant current velocity of m/s. The data reveal that higher structural stiffness results in a more pronounced wave reflection. This observation stems from the fact that an increase in the structure’s rigidity renders the fluid-structure interface less compliant, consequently augmenting the reflection of incident waves by the now stiffer boundary. Furthermore, at shorter wave periods, the reflection amplitude consistently approaches unity ( ≈ 1.0) across the entire range of flexural rigidities, a result that is entirely consistent with physical principles.

Figure 12.

Various flexural rigidity on the reflection under uniform current speed m/s.

Figure 13 illustrates the relationship between and period, presenting how ’s values change across a spectrum of compressive forces (), with the velocity consistently maintained at m/s. Changes in compressive force have a negligible impact on . Conversely, an upward trend in directly correlates with an increase in . Interestingly, the reflection wave amplitude remains close to one across all values when the wave period is low. This effect is likely due to a stiff, vertical wall that ensures wave energy is not lost near its surface.

Figure 13.

Results of reflection for different compression force under uniform current speed m/s.

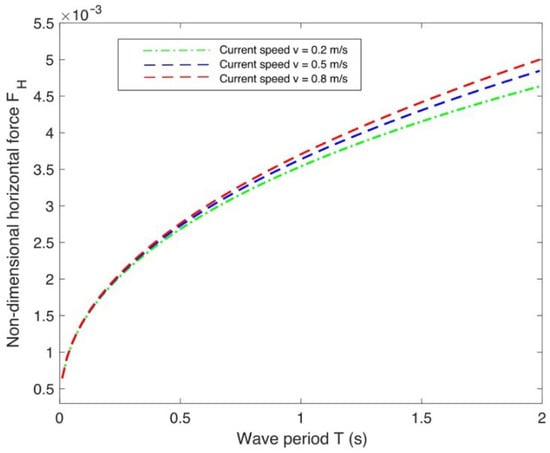

Figure 14 illustrates the variation of the over a range of T for different v affected by a wall. The results show a clear increasing trend of the horizontal force with increasing current speed for the longer wave periods. This trend is consistent with theoretical expectations since longer wave periods are typically associated with higher wave energy, and the combined effects of increasing wave period and higher current speed result in an amplification of the hydrodynamic load on the FIS.

Figure 14.

Non-dimensional horizontal force vs. wave period T for free edge condition under different current speeds.

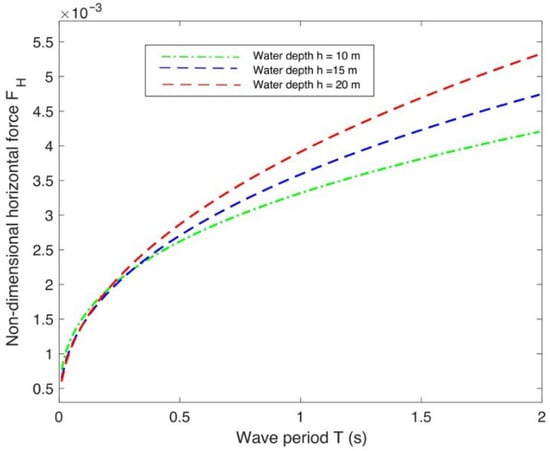

Figure 15 depicts the relationship between the and T for different h, considering the wave reflection by the vertical wall. It can be seen that the is higher for greater water depths and longer wave periods. This suggests that when the water depth is greater, especially in longer wave periods, effectively, the wave energy passes further below the FIS with less attenuation, resulting in a higher horizontal force on the vertical rigid wall.

Figure 15.

Non-dimensional horizontal force vs. wave period T for free edge condition in different water depths.

5. Conclusions

The present work introduces novel mathematical formulations that include the following current interaction with a semi-infinite FIS near a vertical impermeable wall, and an analytical solution using free edge conditions along with orthogonal mode-coupling relation in FWD. Further, the effect of current, along with FIS parameters, on the strain, displacements, the reflection wave amplitude, and horizontal wave force on the wall are analyzed by studying numerical results created using a MATLAB implementation of the governing analytical expressions. The study presents these significant concluding observations.

- The consideration of FC and compressive force for the establishment of the mathematical model and its theoretical solution, along with the orthogonal mode-coupling relation, is an original contribution of this work. The current strain finding aligns with the result achieved in the literature.

- Analysis of the FIS’s strain pattern shows a consistent upward trend linked to increasing compressive force and current speed. In stark contrast, the influence of the FIS’s flexural rigidity and water depths exhibits an inverse relationship, causing strain to lessen as these values rise. Additionally, the observed displacement characteristics of the FIS, which are shaped by variables such as current velocity, applied compressive force, the material’s elastic modulus, and the prevailing water depth, demonstrate consistent alignment with the outcomes of strain analysis.

- Regarding numerical results, the current study examines how FIS affects the reflection wave amplitude and flexural gravity waves across various water depths with different structural and environmental parameters. In a semi-infinite FIS with a vertical rigid wall, the amplitude of the reflected wave was found to be larger for higher current speed, structural rigidity, and compressive force in larger wave periods. The present findings indicate that the reflection wave amplitude is contained within a physical limit of 1.0, consistent with expectations.

- The analysis of the horizontal force on the wall reveals that the higher values of current speed in deeper water increase the force on the vertical rigid wall.

- For marine engineering practical interests in polar regions, FISs often encounter vertical boundaries, ranging from natural continental shelves to man-made structures like drilling platforms and wharves, which effectively behave as a vertical wall. Consequently, studying the reflection of ice-coupled waves by a vertical impermeable wall becomes scientifically significant. Moreover, VLFSs are often deployed near shorelines or integrated with vertical breakwaters, directly exemplifying the interaction between flexural–gravity waves and vertical walls.

- The established framework exhibits specific limitations: the applicable ice sheet covered BC needs to be linear and of fifth-order, and the governing equation should be in 1D, 2D, 3D, and Helmholtz equation. Thus, the existing methodology is suitable for elastic structures that have straightforward shapes and are limited to linear analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.M. and C.G.S.; methodology, S.C.M. and P.A.; writing—original manuscript, S.C.M., P.A. and C.G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The second author has been funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia—FCT), through a doctoral fellowship under the Contract no. UI/BD/154592/2023. This work contributes to the Strategic Research Plan of the Centre for Marine Technology and Ocean Engineering (CENTEC), which is financed by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia—FCT) under contract no. UID/00134/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/00134/2025).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature and Abbreviations

| Following current | |

| Compression of ice sheet | |

| Flexural rigidity | |

| Roots of the dispersion relation | |

| Water depth | |

| Ice sheet deformation | |

| Angular frequency | |

| Acceleration due to gravity | |

| Water density | |

| Laplacian operator | |

| Total velocity potential with time-dependent | |

| Spatial velocity potential | |

| Wave angle | |

| Thickness of ice sheet | |

| Incident wave amplitude | |

| Reflected wave amplitude | |

| Hydrodynamic pressure | |

| Density of ice sheet | |

| FIS | Floating ice sheet |

| VLFS | Very large floating structure |

| FC | Following current |

| BC | Boundary condition |

| CV | Current velocity |

| MIZ | Marginal ice zone |

| BIEM | Boundary integral equation method |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| DEM | Discrete element method |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| BVP | Boundary Value Problem |

| WW3 | WAVEWATCH III® |

| gPC | Generalized polynomial chaos |

| FWD | Finite water depth |

| vs. | Versus |

References

- Herman, A. From apparent attenuation towards physics-based source terms—A perspective on spectral wave modeling in ice-covered seas. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1413116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, K.; Lai, Y.; Gao, D.; Kang, W.H.; Wang, B.; Wang, B. Ice-Induced Vibration Analysis of Offshore Platform Structures Based on Cohesive Element Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.C.; Amouzadrad, P.; Guedes Soares, C. Recent Developments in the Nonlinear Hydroelastic Modeling of Sea Ice Interaction with Marine Structures. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikse, H. Ice engineering challenges for offshore wind development in the Baltic Sea. In Proceedings of the 27th IAHR International Symposium on Ice, Gdańsk, Poland, 9–13 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, J.; Guedes Soares, C. Flexural gravity wave over a floating ice sheet near a vertical wall. J. Eng. Math. 2012, 75, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Wu, G.X.; Shi, Y.Y. Interaction of uniform current with a circular cylinder submerged below an ice sheet. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 86, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, J.; Polojarvi, A.; Tuhkuri, J. Limit mechanisms for ice loads on inclined structures: Buckling. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 147, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.; Xiong, H.; Han, D.; Zeng, L.; Sun, L.; Tan, H. A Review of Ice Deformation and Breaking Under Flexural-Gravity Waves Induced by Moving Loads. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2025, 24, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, T.C.; Willems, T.; Hendrikse, H. Dynamic ice loads for offshore wind support structure design. Mar. Struct. 2023, 87, 103335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Hu, Z.; Luo, Y. An elastic-plastic iceberg material model considering temperature gradient effects and its application to numerical study. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2016, 15, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuprik, V.G.; Zanegin, V.G.; Kim, L.V. Mathematical Modelling of Ice-Structure Interaction. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 272, 022063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.Y.; Han, D.F.; Di, S.C.; Xue, Y.Z. On the Development of Ice-Water-Structure Interaction. J. Hydrodyn. 2020, 32, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Li, Y. A Multi-Yield-Surface Plasticity State-Based Peridynamics Model and Its Applications to Simulations of Ice-Structure Interactions. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2023, 22, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bock und Polach, F.; Klein, M.; Hartmann, M. A New Model Ice for Wave-Ice Interaction. Water 2021, 13, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiew, L.J.; Parra, S.M.; Wang, D.; Sree, D.K.K.; Babanin, A.V.; Law, A.W.K. Wave attenuation and dispersion due to floating ice covers. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 87, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.; Shi, Y.; Li, Z. Two-Dimensional Wave Interaction with a Rigid Body Floating near the Marginal Ice Zone. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amouzadrad, P.; Mohapatra, S.C.; Guedes Soares, C. Numerical Analysis of the effect of current and wind on the dynamics of large floating flexible platform. In Advances in Maritime Technology and Engineering; Soares, C.G., Santos, T.A., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2024; pp. 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Amouzadrad, P.; Mohapatra, S.C.; Guedes Soares, C. Hydroelastic Response to the Effect of Current Loads on Floating Flexible Offshore Platform. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amouzadrad, P.; Mohapatra, S.C.; Guedes Soares, C. Hydroelastic Response of a Moored Interconnected Floating Platform under Current Loading. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobkin, A.; Khabakhpasheva, T.I. Consistent Models of Flexural-Gravity Waves in Floating Ice. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, M.; Owen, C.C.; Hendrikse, H. Experimental study on ice-structure interaction phenomena of vertically sided structures. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 201, 103628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikse, H.; Nord, T.S. Dynamic response of an offshore structure interacting with an ice floe failing in crushing. Mar. Struct. 2019, 65, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Mills, J.; Gash, R.; Pearson, W. A literature survey of broken ice-structure interaction modelling methods for ships and offshore platforms. Ocean Eng. 2021, 221, 108527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, J.K.; Roberts, A.; Geiger, C.A.; Menge, J.R. Spatial and temporal characterization of sea-ice deformation. Ann. Glaciol. 2011, 52, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhkuri, J.; Polojärvi, A. A review of discrete element simulation of ice–structure interaction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2018, 376, 20170335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, T.; Colbourne, B.; Quinton, B.; Molyneux, D.; Peng, H.; Spencer, D. A review of iceberg and bergy bit hydrodynamic interaction with offshore structures. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2017, 135, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ren, K.; Li, M.; Tukovi’c, Ž.; Cardiff, P.; Thomas, G. Fluid-structure interaction of a large ice sheet in waves. Ocean Eng. 2019, 182, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.C.N.; Onorato, M.; De Vita, F.; Clauss, G.; Ehlers, S.; von Bock und Polach, F.; Schmitz, L.; Hoffmann, N.; Klein, M. Hydroelastic potential flow solver suited for nonlinear wave dynamics in ice-covered waters. Ocean Eng. 2022, 259, 111756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, S.; Huang, L.; Azhari, F.; Babanin, A.V. Viscoelastic Wave–Ice Interactions: A Computational Fluid–Solid Dynamic Approach. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.Z.; Zeng, L.D.; Ni, B.Y.; Korobkin, A.A.; Khabakhpasheva, T.I. Hydroelastic response of an ice sheet with a lead to a moving load. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33, 037109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Thomas, G. Simulation of Wave Interaction with a Circular Ice Floe. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2019, 141, 041302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staroszczyk, R. On maximum forces exerted by floating ice on a structure due to constrained thermal expansion of ice. Mar. Struct. 2021, 75, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wei, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, L. Study on the mechanism of water entry under the effect of floating ice based on a penalty function-based fluid–structure interaction method. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 123334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsabvarodom, C.; Leira, B.J.; Høyland, K.V.; Næss, A.; Samardžija, I.; Chai, W.; Komonjinda, S.; Chaichana, C.; Xu, S. On Statistical Features of Ice Loads on Fixed and Floating Offshore Structures. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Lou, M. Investigating Load Calculation for Broken Ice and Cylindrical Structures Using the Discrete Element Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Pan, Z.; Wu, B. Three-dimensional Green-function method to predict the water wave radiation of a submerged body with ice cover. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 101, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kohout, A.L.; Doble, M.J.; Wadhams, P.; Guan, C.; Shen, H.H. Rollover of apparent wave attenuation in ice covered seas. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2017, 122, 8557–8566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Jiang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Liu, R.; Liu, Z. Numerical Simulation of Ice and Structure Interaction Using Common-Node DEM in LS DYNA. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wu, K.; Peng, X.; Jia, X.; Wang, G. Study on the Factors Influencing the Amplitude of Local Ice Pressure on Vertical Structures Based on Model Tests. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, V.A. Synergies between VLFS hydroelasticity and sea-ice research. Int. J. Offshore Polar Eng. 2008, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mosig, J.E.M.; Montiel, F.; Squire, V.A. Water wave scattering from a mass loading ice floe of random length using generalised polynomial chaos. Wave Motion 2017, 70, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timco, G.W.; Weeks, W.F. A review of the engineering properties of sea ice. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2010, 60, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennetts, L.G.; Peter, M.A.; Squire, V.A.; Meylan, M.H. A three-dimensional model of wave attenuation in the marginal ice zone. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, C12043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocklehurst, P.; Korobkin, A.A.; Părău, E.I. Interaction of hydro-elastic waves with a vertical wall. J. Eng. Math. 2010, 68, 215–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, P.; Mandal, B.N. Wave scattering by a thin vertical barrier submerged beneath an ice-cover in deep water. Appl. Ocean Res. 2010, 32, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobkin, A.; Khabakhpasheva, T.I.; Papin, A.A. Waves propagating along a channel with ice cover. Eur. J. Mech.—B Fluids 2014, 47, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Lubbad, R.; Høyland, K.; Løset, S. Physical model and theoretical model study of level ice and wide sloping structure interactions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2014, 101, 40–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shen, H.H.; Cheng, S. Modeling ocean wave propagation under sea ice covers. Acta Mech. Sin. 2015, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, G.M.; Squire, V.A. A boundary-integral method for the interaction of large-amplitude ocean waves with a compliant floating raft such as a sea-ice floe. J. Eng. Math. 2008, 62, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, X. Theoretical model for predicting the break-up of ice covers due to wave-ice interaction. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 112, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batyaev, E.; Khabakhpasheva, T.I. Flexural-Gravity Waves in a Channel with a Compressed Ice Cover. Water 2024, 6, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Wang, Z.Q. Steady-state response of an infinite, free floating ice sheet to a moving load at constant velocity. Ocean Eng. 2024, 314, 119627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.; Zou, Y.; Li, Z.; Shi, Y. The effect of large ice sheet on the hydrodynamic force of side-by-side barges relevant to offloading. Ocean Eng. 2025, 317, 120009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xiao, R.; Xue, Z.; Yu, F. Effects of cracked semi-infinite ice sheets on the wave excited motion of a body floating on water. Ocean Eng. 2025, 325, 120769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Ye, L.; Wang, C.; Yu, F. Wave attenuation by three-dimensional circular floating sea ice: Regular and irregular waves. Ocean Eng. 2024, 305, 117918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Părău, E.I.; Vanden-Broeck, J.M. Three-dimensional waves beneath an ice sheet due to a steadily moving pressure. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2011, 369, 2973–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostikov, V.K.; Hayatdavoodi, M.; Ertekin, R.C. Drift of elastic floating ice sheets by waves and current, part I: Single sheet. Proc. R. Soc. A 2021, 477, 20210449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.C.; Guedes Soares, C. Effect of mooring lines on the hydroelastic response of a floating flexible plate using the BIEM approach. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.C.; Guedes Soares, C. Effect of submerged horizontal flexible membrane on a moored floating elastic plate. In Maritime Technology and Engineering 3; Soares, G., Santos, Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1181–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra, S.C.; Guedes Soares, C. Hydroelastic behaviour of a submerged horizontal flexible porous structure in three-dimensions. J. Fluids Struct. 2021, 104, 103319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.C.; Guedes Soares, C. 3D hydroelastic modelling of fluid-structure interactions of porous flexible structures. J. Fluids Struct. 2022, 112, 103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.C.; Guedes Soares, C. Interaction of surface gravity wave motion with elastic bottom in three-dimensions. Appl. Ocean Res. 2016, 57, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobkin, A.A.; Stukolov, S.V.; Sturova, I.V. Motion of a vertical wall fixed on springs under the action of surface waves. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 2009, 50, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafydd, L.; Porter, R. Attenuation of long waves through regions of irregular floating ice and bathymetry. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 996, A43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyenne, P.; Părău, E.I. Numerical study of solitary wave attenuation in a fragmented ice sheet. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2017, 2, 034002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.; Porter, R. Approximations to wave scattering by an ice sheet of variable thickness over undulating bed topography. J. Fluid Mech. 2004, 509, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shen, H.H. Gravity waves propagating into an ice-covered ocean: A viscoelastic model. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2010, 115, C06024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amouzadrad, P.; Mohapatra, S.C.; Guedes Soares, C. Review on Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis of Hydrodynamic and Hydroelastic Responses of Floating Offshore Structures. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.; Squire, V.A. On the oblique reflection and transmission of ocean waves at shore fast sea ice. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1994, 347, 185–218. [Google Scholar]

- Schulkes, R.M.S.M.; Hosking, R.J.; Sneyd, A.D. Waves due to a steadily moving source on a floating ice plate. Part-2. J. Fluid Mech. 1987, 180, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukatov, A.E.; Zavyalov, D.D. Impingement of surface waves on the edge of compressed ice. Fluid Dyn. 1995, 30, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, V.A.; Hosking, R.J.; Kerr, A.D.; Laghorne, P.J. Moving Loads on Ice Plates; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra, S.C.; Ghoshal, R.; Sahoo, T. Effect of compression on wave scattering by a floating elastic plate. J. Fluids Struct. 2013, 36, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).