Abstract

The coastal environment is a dynamic system shaped by both natural processes and human activities. In recent decades, increasing anthropogenic pressure and climate change—manifested through sea-level rise and more frequent extreme events—have accelerated coastal retreat, highlighting the need for improved management strategies and standardized tools for coastal risk assessment. Existing approaches remain highly heterogeneous, differing in structure, input data, and the range of factors considered. To address this gap, this study proposes an index-based methodology of general validity designed to quantify coastal erosion risk through the combined analysis of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure factors. The approach was developed for multi-scale and multi-risk applications and implemented across 54 representative sites along the Calabrian coast in southern Italy, demonstrating strong adaptability and robustness for regional-scale assessments. Results reveal marked spatial variability in coastal risk, with the Tyrrhenian sector exhibiting the highest values due to the combined effects of energetic wave conditions and intense anthropogenic pressure. The proposed framework can be easily integrated into open-access GIS platforms to support evidence-based planning and decision-making, offering practical value for public administrations and stakeholders, and providing a flexible, accessible tool for integrated coastal risk management.

1. Introduction

Coastal areas host a significant share of the world’s population and concentrate critical infrastructures, economic activities, and essential ecosystem resources [1,2]. Coastal erosion, together with sea-level rise, poses an increasing threat to these areas. Its impacts range from the loss of emerged land and natural habitats to the degradation of ecosystem services, as well as direct damage to assets of outstanding natural, landscape, and historical–archeological value, including settlements and strategic infrastructure [3,4,5]. At the global scale, the combined effects of sea-level rise and anthropogenic pressures are undermining ecosystem services [6] and causing severe impacts in multiple contexts [7,8]. Consequently, coastal risk assessment has become one of the most pressing scientific and operational challenges worldwide, within a framework of intensifying human pressure and accelerated climate change. There is therefore an urgent need for robust methodologies that can assess risk and support adaptation and sustainable management strategies.

Over recent decades, coastal risk assessment has evolved from purely physical approaches to integrated methodologies that jointly consider hazard, vulnerability, and exposure. The introduction of the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) enabled comparative assessments of coastal vulnerability at regional and national scales [9,10]. However, it also revealed limitations related to oversimplification and low adaptability to diverse geomorphological and socioeconomic settings [11,12,13,14].

In Italy and across Europe, numerous studies have applied and adapted index-based methods. These include the Regional Coastal Management Plan of Basilicata [15], the Coastal Master Plan of Calabria [16], and risk assessments in Campania [17] and Molise [18]. Further examples include the validation of storm-impact frameworks in Emilia–Romagna [19], the application of the CVI in Apulia [20], and the development of specific indices for Mediterranean dune systems [21]. At broader scales, assessments have been carried out for the Northern Adriatic [22], the Portuguese coast [23], the French Mediterranean coastline [24], Scotland [25], and the UK physical–economic coastal vulnerability index [26].

At the international level, recent studies have developed advanced approaches, including GIS- and multicriteria-based analyses [27,28], AHP methods addressing uncertainty [29,30], multi-hazard indices [31,32], extreme-event assessments [33], and comparative analyses of empirical models [34]. Some works have incorporated the CVI into planning and monitoring tools, such as in the Gulf of Finland [35] and in Morocco, where Muzirafuti and Theocharidis [36] applied remote sensing and GIS to the Casablanca coastline. Additional studies have combined numerical modelling and remote sensing to assess coastal erosion [37].

Parallel to these developments, new indices have been proposed to integrate geomorphological, climatic, and socioeconomic factors [38]. Examples include the Italian ISMV [39], the Integrated Coastal Vulnerability Index (ICVI) for Mexico [40], and multi-hazard approaches for European coastal cities [41]. GIS, remote sensing, and machine learning technologies have become central tools for ensuring accurate and scalable analyses [42,43,44,45]. At the same time, Nature-based Solutions (NbSs) have demonstrated effective performance in mitigating erosion and flood risks [46,47,48]. Participatory and multi-scalar approaches have also proven crucial for enhancing the robustness of assessments and supporting sustainable management policies [49,50].

Overall, the current state of the art demonstrates a clear trend toward increasingly complex, integrated, and adaptive methodologies. These approaches combine biophysical and socioeconomic indicators, GIS and remote sensing tools, probabilistic frameworks, and nature-based solutions. However, as summarized in Table 1, which synthesizes the main methodologies referenced above, existing national and international frameworks remain highly heterogeneous. They differ not only in calculation methods, which vary depending on the coastal region under investigation [11,51], but also in the significant variety and fragmentation of the factors they include.

Table 1.

Summary of the main referenced methodologies, encompassing national and international frameworks for coastal risk assessment, with indication of their application scale, study area, and the coastal hazard and vulnerability factors considered.

The analysis of Table 1 highlights that coastal risk assessments predominantly focus on morphological and hydrodynamic aspects, such as beach morphology, wave climate, coastal geology, and shoreline evolution. In contrast, factors related to anthropogenic pressures and terrestrial dynamics (e.g., riverine sediment supply, soil sealing, coastal and port structures, and precipitation) are less frequently considered. This imbalance highlights persistent methodological heterogeneity and reinforces the need for integrated and standardized approaches capable of systematically including the full range of variables influencing coastal risk. There is therefore a strong demand for shared and replicable procedures that can reduce methodological discrepancies and enable consistent comparisons across different coastal areas.

Within this framework, the present study proposes an innovative approach designed to help fill this gap and strengthen resilient coastal management strategies. Recognizing that coastal erosion cannot be effectively addressed without a multidisciplinary and systemic perspective, this research aims to define a generalizable coastal risk assessment procedure that organically integrates all relevant factors. The proposed methodology is developed for the coasts of the Calabria region in southern Italy but is extendable to the entire national territory. It can be implemented within an open-source GIS environment and aims to provide an operational tool for public authorities, private entities, and stakeholders involved in coastal zone planning and management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study: The Calabria Region

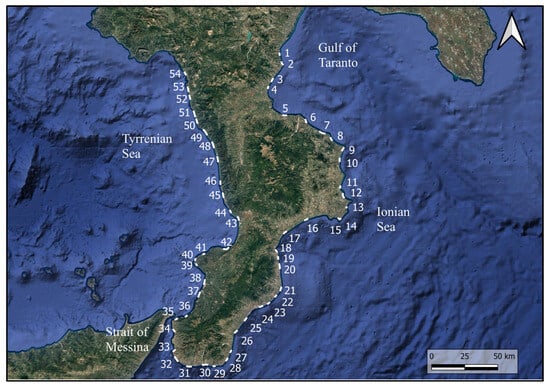

Calabria, located at the southernmost tip of the Italian peninsula, covers an area of approximately 15,079 km2 and has a population of just over two million inhabitants. The region is divided into five provinces (Catanzaro, Cosenza, Crotone, Reggio Calabria, and Vibo Valentia) and includes 409 municipalities, 116 of which have coastal development. It borders Basilicata to the north, is bounded by the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west and the Ionian Sea to the east and is separated from Sicily to the south by the Strait of Messina, which narrows to just 3.2 km at its closest point (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Calabrian region (shown with red dotted line), in the centre of the Mediterranean Sea.

The territory is predominantly hilly (49.2%) and mountainous (41.8%), with major mountain chains such as the Pollino, Catena Costiera, Sila, Serre, and Aspromonte ranges. The main lowland areas are the plains of Sibari, Lamezia Terme, and Gioia Tauro. From a hydrographic perspective, Calabria is characterized by ephemeral and torrential watercourses known as fiumare, which are prone to sudden and intense floods, exhibit high sediment transport, and exert a strong influence on coastal dynamics. Numerous artificial lakes are also present, particularly on the Sila plateau.

The Calabrian coastline extends for approximately 736 km, alternating sandy and gravel beaches with stretches of high, rocky cliffs. Anthropogenic pressure is considerable, particularly around coastal provincial capitals and in areas with a strong touristic vocation, where recreational activities and beach facilities play a key role in the regional economy. The coastline can be subdivided into three main sectors: the Tyrrhenian (over 250 km), the Ionian (over 400 km), and the Strait of Messina (about 40 km). The Tyrrhenian and Ionian sectors are exposed to wave conditions associated with long fetches—sometimes exceeding 1500 km—whereas the Strait of Messina is characterized by shorter fetches and a generally less energetic wave climate.

From a geomorphological standpoint, the Tyrrhenian coast is distinguished by a high proportion of steep cliffs (reaching up to 40% in some provinces), limited lowland areas, and a significant degree of urbanization along the remaining low-lying sectors. Conversely, the Ionian coast is dominated by alluvial plains that have historically favoured human settlement, with approximately 30% of low-lying coasts occupied by anthropogenic activities. The coastal area of the Strait, finally, is densely urbanized due to both its narrow morphological configuration and its proximity to Sicily.

For this study, a total of 54 sampling sites were selected and distributed across the three coastal sectors of the region: 32 along the Ionian coast, 19 along the Tyrrhenian coast, and 3 within the Strait of Messina area, encompassing approximately 116 km of coastline (Figure 2). The selection of sites was guided by the availability of wave and meteorological data, as well as by the need to represent the diversity of coastal morphologies present along the study area. A list of the analyzed sites is provided in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Location of the 54 sample sites in the Calabria region where the analysis was carried out: 1–32 along the Ionian coast, 33–35 within the Strait of Messina, 36–54 along the Tyrrhenian coast.

Table 2.

List of the 54 sample areas in the Calabria region where the study was conducted: sites 1–32 are located along the Ionian coast, sites 33–35 within the Strait of Messina, and sites 36–54 along the Tyrrhenian coast.

2.2. Methodological Framework

The methodology developed for coastal risk assessment is based on an index-based approach, selected for its ease of application and its potential integration within a GIS environment. Although calibrated for the Calabrian context, the method has general validity and can be adapted to different territorial scales (local, municipal, provincial, or interregional). The proposed model assesses the coastal risk index () as the product of three fundamental components:

where

- Hazard Index (): measures the intensity of natural forcing agents such as wave climate, wind, currents, and sea-level rise.

- Vulnerability Index (): describes the susceptibility of the coastal system based on its geomorphological, ecological, and anthropogenic characteristics.

- Exposure Index (): evaluates the assets and population located in areas potentially affected by coastal hazards.

Each index is computed as a weighted mean of its elementary variables, classified into five categories (1 = very low; 5 = very high) and then normalized within the range 0–1. The normalization procedure follows the mathematical formulation proposed in the CRI-MED methodology [13]. Accordingly, the hazard, vulnerability, and exposure indices are calculated using the following general expressions:

where , and represent the number of variables considered for hazard, vulnerability, and exposure, respectively; the weights , and are assigned to each variable according to its relative contribution to the definition of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure within the coastal risk assessment framework.

The weighting system was defined through a structured consultation process involving ten experts selected to represent the principal institutional and technical stakeholders engaged in coastal risk management in Calabria. These experts belonged to three key categories: public institutions (regional administrations and coastal management authorities), regional professionals (engineers, geomorphologists, and coastal technicians), and academic organizations (university researchers specializing in coastal dynamics and risk assessment). The combination of these complementary profiles ensured a comprehensive and multidisciplinary evaluation of the parameters included in the index.

The methodology developed in this study builds upon and significantly advances the 2013 Coastal Master Plan. Consequently, all political and decision-making actors involved in its formulation were actively engaged in defining the weighting criteria for each variable. The participation of the ten specialists enabled the integration of institutional perspectives related to territorial governance, the operational experience of professionals working directly on coastal processes, and the scientific insights contributed by the academic community.

The adopted approach was data-driven and emphasized assigning greater weight to those parameters identified by empirical evidence as the most influential and reliable. Through iterative discussions and comparison of independent technical assessments, the experts converged on a robust weighting scheme grounded in observed coastal behaviour and regional management priorities. The justification for the selected weighting values is presented in Section 3.

This rigorous and collaborative process ensured that the final weighting framework is not only technically sound but also aligned with the strategic objectives of coastal management in Calabria. As a result, the proposed index benefits from enhanced methodological consistency and improved practical applicability, providing a solid basis for informed decision-making and sustainable coastal planning.

Once estimated, the three indices (, , ) are classified according to the threshold values reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Classification of hazard, vulnerability and exposure indices.

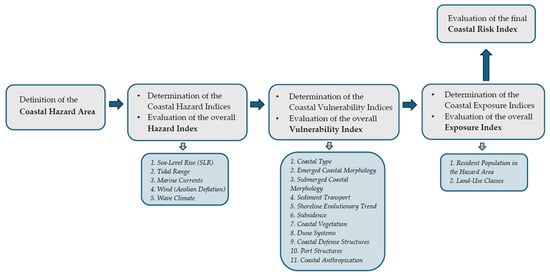

The developed methodology can be structured into five main phases (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the new methodology developed for coastal risk assessment.

- Definition of the Coastal Hazard Area;

- Determination of the Coastal Hazard Indices and evaluation of the overall Hazard Index;

- Determination of the Coastal Vulnerability Indices and evaluation of the overall Vulnerability Index;

- Determination of the Coastal Exposure Indices and evaluation of the overall Exposure Index;

- Evaluation of the final Coastal Risk Index.

2.2.1. Definition of the Coastal Hazard Area

The coastal area potentially at risk is defined as the zone between the present shoreline and the maximum elevation reached by the sea level under extreme conditions. This elevation is determined as the sum of:

- Wave run-up and set-up (with a 100-year return period);

- Astronomical and meteorological tides;

- Projected sea-level rise over a 100-year horizon according to the most severe IPCC scenario.

2.2.2. Hazard Indices

Coastal hazard factors represent the main climatic forcing agents that, with varying intensity and incidence, drive erosional processes. These include tides, currents, winds, waves, and, in particular, sea-level rise induced by global warming—an ongoing and unavoidable phenomenon that must be considered in contemporary coastal risk assessments.

Accordingly, the proposed model incorporates five main hazard sub-indices, which represent the following components:

(1) Sea-Level Rise (SLR). This sub-index is based on the rate of sea-level rise (mm/year), estimated through satellite observations and assessments provided by the IPCC and NASA. Although SLR is a global-scale parameter with limited regional variability, its inclusion is essential because it contributes to long-term increases in hazard. As in many coastal vulnerability studies, this sub-index may be evaluated using the class intervals proposed by Pendleton et al. (2004) [52].

(2) Tidal Range. This parameter is derived from the mean tidal range (m) recorded at tide-gauge stations. The associated index value is estimated using the five-class tidal regime classification proposed by Hayes (1979) [53].

(3) Marine Currents. This sub-index accounts for the influence of marine currents on coastal erosion, especially in narrow straits or channels where geographic configuration enhances current velocity. Because higher current speeds generally correspond to higher hazard levels, the hazard classes were defined as a function of mean current speed (knots) for the Italian seas and for the Strait of Messina, based on expert judgement. These values can be derived from published datasets, tide tables, and nautical charts.

(4) Wind (Aeolian Deflation). The wind-deflation index quantifies the direct effect of wind on coastal erosion—generally modest—and reflects the aeolian transport capacity. It is expressed as the percentage of annual hours during which wind velocity exceeds the critical threshold for sediment transport. This threshold, defined by Bagnold (1941) [54] based on sediment characteristics, is estimated from wind data at 10 m height using the simplified relationship proposed by Hsu (1974) [55]. Comparing this critical velocity with observed wind time series allows estimation of exceedance probability and, consequently, the site-specific index value. The hazard classes associated with the wind deflation index were defined based on the statistical distribution of the data.

(5) Wave Climate. The wave-climate index () was computed by dividing the Calabrian coastline into three macro-areas (Tyrrhenian, Strait of Messina, and Ionian) based on exposure and fetch. Following and refining the approach of Barbaro (2016) [16], the updated formulation also accounts for secondary exposure sectors and wave run-up. The index is expressed as the weighted mean (with equal weights) of four sub-indices ranging from 0 to 1, as described below:

where

- is the wave energy flux index, defined as the ratio between the sum of the energy fluxes of the active (or incident) directional sectors at the site under examination and the maximum value recorded within the corresponding macro-area of reference.

- is the index associated with the wave exposure sectors, defined as the weighted mean of the indices corresponding to the primary and, where applicable, the secondary wave-approach sectors, using their respective energy fluxes as weights. The primary sector corresponds to the direction of maximum wave energy, while the secondary sector refers to a secondary energy peak. The index for the primary sector captures the greater forcing exerted by waves approaching the shoreline orthogonally (shoaling) compared to more oblique waves (refraction), tending toward 1 as wave incidence becomes more perpendicular. The inclusion of the secondary sector represents conditions where the coastline is influenced by multiple wave-attack directions, thereby extending the original formulation proposed by Barbaro (2016) [16].

- is the index related to the variation in significant wave height with return period, defined as the ratio between the mean value of calculated for the different return periods at the site under analysis and the corresponding maximum value computed for the reference macro-area. Here, represents the difference in significant wave height calculated for successive return periods (1, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 years).

- is the index associated with the variation in wave run-up with return period, defined as the ratio between the mean value of calculated for the different return periods at the site under analysis and the corresponding maximum value computed for the reference macro-area. Here, represents the difference between the run-up values calculated for successive return periods at the same location. The run-up values were estimated using the empirical formulation proposed by Stockdon et al. (2006) [56].

The hazard classes associated with the wave climate index were defined by dividing the admissible range into five equal intervals, as all sub-indices are normalized with respect to their maximum value.

The coastal hazard indices defined in the new methodology, together with their classification criteria, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Definition of coastal hazard indices according to the new methodology and the adopted classification criteria.

2.2.3. Coastal Vulnerability Indices

Coastal vulnerability factors represent the elements through which the susceptibility of a coastal system to erosional processes can be assessed. They derive from a combination of natural and anthropogenic characteristics that jointly determine shoreline stability. Geological and geomorphological conditions—both in the emerged and submerged zones—play a central role, as does the analysis of historical shoreline evolution, which helps to identify erosional or accretional trends. Equally important is the balance between littoral drift and fluvial sediment inputs, which directly affects sediment availability along the coast. Additional factors include the presence of coastal defence structures and port infrastructures, as well as dune systems and vegetation cover, which can either exacerbate or mitigate erosional processes. Finally, parameters such as subsidence rates and the degree of soil sealing further contribute to determining the overall level of coastal vulnerability.

Accordingly, the proposed methodology considers eleven coastal vulnerability variables, grouped as follows:

(1) Coastal Type. Based on the most widely adopted morphological classification, which distinguishes between high rocky coasts and low sandy coasts, the vulnerability classes for this index follow the scheme proposed by Ferreira et al. (2017) [57], which is well suited to the conditions of the Calabrian coastal environment.

(2) Emerged Coastal Morphology. The vulnerability of the emerged coast was evaluated using two parameters: beach slope and mean beach width. Gently sloping and narrow beaches are more exposed to erosional and flooding processes than wider and steeper ones. Both parameters were estimated using transects derived from satellite imagery and Digital Terrain Models (DTMs) (Google Earth, QGIS). Vulnerability classes were adapted from the classification of Ferreira et al. (2017) [57] to the Calabrian context. The overall index was calculated as the arithmetic mean of the two sub-indices, with equal weighting.

(3) Submerged Coastal Morphology. The vulnerability of the submerged coast was assessed based on seafloor slope, since steeper profiles lead to increased wave run-up and, consequently, greater exposure to erosion. This parameter was derived from available bathymetric data. Vulnerability classes follow the scheme of Ferreira et al. (2017) [57], adapted to the geomorphological characteristics of the Calabrian coast.

(4) Sediment Transport. Coastal vulnerability is strongly influenced by the sediment budget, expressed as the ratio between fluvial sediment supply and longshore sediment transport. The latter is controlled by meteorological–marine forcing and sediment grain size. In this study, the balance is represented by an index defined as the ratio between Qr and Ql, where Qr represents the fluvial sediment input to the physiographic unit and Ql the longshore sediment transport. Index values equal to or greater than 1 indicate low vulnerability, whereas values approaching zero reflect critical sediment deficit conditions and therefore high vulnerability. Accordingly, to reflect all possible sediment budget conditions and based on expert judgement, the vulnerability classes were obtained by dividing the value range into five equal intervals. The estimation of sediment transport rates can be performed through a simplified modelling approach. Although less detailed than full numerical modelling, this method provides reliable order-of-magnitude estimates suitable for comparing the two components and classifying vulnerability.

(5) Shoreline Evolutionary Trend. The shoreline evolution trend was evaluated following the methodology of Foti et al. (2022) [58], based on the comparison of cartographic datasets and satellite imagery. The overall index was computed by combining the trends calculated for different time intervals through a weighted average, assigning higher weights to shorter temporal scales. Specifically, the evolutionary trend was assessed over the following temporal scales: between the two most recent shorelines, short-term (last 5 years), medium-term (last 20 years), long-term (last 30 years), and very long-term (last 70 years). Higher weights were assigned to short-term trends to better capture ongoing erosional processes and to provide an accurate representation of current coastal vulnerability. This choice is also justified by the higher homogeneity and precision of the most recent shoreline datasets, which ensure greater reliability compared to older sources. Vulnerability classes were defined according to the classification proposed by Barbaro (2016) [16]: advancement (v > 0.5), stability (–0.5 ≤ v ≤ 0.5), erosion (–1 ≤ v < –0.5), intense erosion (–2 ≤ v < –1), and severe erosion (v < –2).

(6) Subsidence. Subsidence, often of anthropogenic origin, constitutes a significant vulnerability factor because it amplifies storm surge and sea-level-rise impacts. Vulnerability classes, expressed as mean subsidence rate (mm/year), were calibrated using available studies for affected Calabrian areas.

(7) Coastal Vegetation. Coastal vegetation is a key element of shoreline resilience, as it dissipates wave energy and reduces erosion during extreme events [59,60,61]. Marine vegetation, particularly Posidonia Oceanica, plays an equally important role in stabilizing beaches and maintaining biodiversity [62,63,64]. Accordingly, a vegetation vulnerability index was defined as the weighted mean of three sub-indices: average width of coastal vegetation, corrected for density (with weight equal to 40%); percentage of coastline protected by vegetation (with weight equal to 40%); presence/absence of Posidonia Oceanica (with weight equal to 20%). Vulnerability classes were adapted from Sekovski et al. (2020) [65] and Pantusa et al. (2018) [20] to the Calabrian context. The three sub-indices were evaluated using satellite data (Google Earth, QGIS) and historical datasets containing information on the mapping of coastal habitats.

(8) Dune Systems. Coastal dune systems act as natural defences against erosion and flooding, functioning as sediment reservoirs, physical barriers, and hydrogeological buffers against saltwater intrusion [66,67]. Their development depends on waves, wind, sediment supply, and vegetation, but they are highly vulnerable to climate change and anthropogenic pressures [68]. Given their role in enhancing coastal resilience, a dune-system vulnerability index was defined as the weighted mean of three sub-indices: average dune elevation (with weight equal to 30%), average dune width (with weight equal to 30%), percentage of coastline protected by dunes (with weight equal to 40%). Vulnerability classes were adapted from Sekovski et al. (2020) [65] and Pantusa et al. (2018) [20] to fit the Calabrian coastal conditions. The analysis was performed using satellite imagery, Digital Terrain Models (DTMs), and GIS tools (Google Earth, QGIS).

(9) Coastal Defence Structures. Coastal defence structures significantly influence vulnerability because they modify littoral currents and sediment transport, sometimes worsening local erosion. The coastal defence index was therefore defined as the ratio between the length of protected shoreline (PSL) and the total coastline length, corrected to account for the preservation state of structures. The assessment was performed through satellite imagery and GIS-based analysis (Google Earth). Regarding the determination of PSL, which varies depending on the type of structure, this study provides the following methodological approach:

- Emerged barriers: the PSL is assumed to be equal to the length of the barrier.

- Submerged barriers: the PSL is estimated as the barrier length multiplied by a coefficient corresponding to the wave transmission coefficient. In this study, the coefficient was calculated using the empirical formulation proposed by Van der Meer (1990) [69].

- Groynes: the PSL is determined based on both the groyne length and the angle of incidence of the predominant wave direction.

- T-head groynes: the PSL is calculated as the sum of the contributions from the groyne and the breakwater components.

Vulnerability classes were defined by equally partitioning the admissible value range into five intervals, to account for the degree of protection provided by coastal defence structures and based on expert judgement. The highest vulnerability levels occur along coastal stretches already affected by erosion but only weakly protected, whereas unprotected shorelines without coastal defence structures are assigned a score of zero.

(10) Port Structures. Port infrastructures can significantly alter littoral dynamics by interrupting or reducing sediment transport, often triggering localized erosional processes. The corresponding port-structure vulnerability index was defined as a function of the maximum cross-shore extension of the port basin (A), normalized with respect to the regional maximum. The resulting normalized range was then uniformly divided into five intervals to establish the vulnerability classes. In the absence of port facilities, the index assumes a null value.

(11) Coastal Anthropization. The coastal anthropization vulnerability index was defined as the percentage of shoreline that has been artificially modified or hardened (i.e., non-erodible coastal segments). Vulnerability classes were established by equally partitioning the admissible value range into five intervals, following expert judgement to appropriately account for the varying degrees of anthropogenic influence along the coastline. As the proportion of urbanized or engineered coastline increases, vulnerability to erosion decreases, since the shoreline no longer corresponds to the natural beach–sea interface but to structures or infrastructures protected by revetments or seawalls.

The coastal vulnerability indices defined in the proposed methodology, along with their respective classification criteria, are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Definition of vulnerability indices according to the new methodology and the adopted classification criteria.

2.2.4. Coastal Exposure Indices

The assessment of elements exposed to coastal risk was conducted using two main indices: resident population within the hazard area and land-use classes. Although this approach does not provide a detailed socio-economic valuation, it is consistent with legislative and regulatory frameworks and allows for an effective and reliable representation of the value of exposed assets along eroding coastal sectors.

(1) Resident Population within the Hazard Area. The population exposure index was estimated following the methodology of the EUROSION Project (2004) [70], using ISTAT (2020) demographic data [71] and CORINE Land Cover (CLC 2018) shapefiles [72]. Population counts were calculated as the sum of residents within urban, agricultural, and natural areas, weighted according to their respective population densities. The exposure index increases proportionally with the number of residents located within the hazard zones.

(2) Land-Use Classes. The land-use exposure index was developed in compliance with current risk-assessment regulations, using CLC 2018 shapefiles and cartographic data from the Regional Geoportal [73]. The classification of exposed elements was based on the categories of potential damage indicated in the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of Directive 2007/60/EC [74], in order to represent the socio-economic value associated with different land-use types. The level of exposure increases with the relevance of the category, reflecting the potential impact on people, economic assets, environmental resources, and cultural heritage. The overall land-use exposure index was calculated as the mean of three sub-indices—areal, linear, and point-type shapefiles—thereby integrating all available spatial information in a consistent way.

The classification criteria for the two exposure indices were defined in accordance with the relevant legislative and regulatory frameworks.

The exposure indices defined in the proposed methodology, along with their respective classification criteria, are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Definition of exposure indices according to the new methodology and the adopted classification criteria.

2.2.5. Coastal Risk Index

Table 7 provides a concise overview of the origin and definition criteria of the classification thresholds adopted for the Hazard, Vulnerability and Exposure indices. The thresholds were identified based on literature references, existing regulations, and statistical analyses applied to the study dataset, ensuring scientific consistency and adequate representativeness of the investigated context.

Table 7.

Origin of classification thresholds used for Hazard, Vulnerability and Exposure indices.

Finally, the coastal risk index () is estimated using Equation (1). Accordingly, for each analyzed site, the resulting value is used to determine the coastal risk level according to the classification adopted in the Italian application of the EUROSION Project [70,75]. This classification, expressed on a percentage scale, is summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Classification of the Coastal Risk Index.

2.3. Validation Protocol

The applied validation procedure is based on an integrated approach that combines independent observational data, multitemporal analyses of coastal dynamics, and a set of quantitative metrics consolidated in the literature on spatial model validation. After harmonizing historical shoreline datasets estimates of fluvial sediment supply and alongshore sediment transport, wave–meteorological data, and satellite-derived information, model verification was carried out on coastal sectors characterized by well-documented erosive dynamics, which served as independent benchmark sites.

The comparison between modelled risk classes, observed shoreline trends (SET index), and external technical and scientific evidence was supported by two key metrics. The first is the Spatial Concordance Index (SCI), used to quantify spatial consistency between thematic maps and widely supported in the literature [76,77]. This index belongs to the family of map comparison metrics developed for the validation of spatially explicit models [78,79] and is conceptually related to measures of spatial agreement and thematic concurrence [80]. The SCI is computed as the ratio between the number of sites where the predicted risk class matches the observed erosive trend and the total number of sites, providing a synthetic measure of spatial agreement.

The second metric is the Component-wise Consistency Index, which independently evaluates hazard, vulnerability, and exposure by comparing each component with erosion hotspots identified through satellite data, regional reports, and field evidence. This approach is consistent with multilayer validation practices discussed in the literature on environmental model accuracy assessment and predictive mapping [81,82].

The combined adoption of these metrics enables an objective and transparent quantification of the reliability of the proposed methodology and its ability to faithfully reproduce the erosion processes observed in the field.

3. Results

The proposed coastal erosion risk assessment methodology was applied to 54 sample sites distributed along the three main coastal sectors of Calabria. The analysis integrated geomorphological, meteomarine, hydrological, and anthropogenic data, allowing for a comprehensive characterization of coastal hazard, vulnerability, exposure, and overall risk conditions. Table 9 summarizes the data and their corresponding sources used to estimate the variables included in the developed methodology.

Table 9.

Data used and their sources.

3.1. Coastal Hazard

The analysis of the hazard variables enabled the estimation of sea-level rise (SLR) for all study areas, adopting a growth rate of 4.5 mm/year, consistent with satellite-based studies [83]. Consequently, the corresponding hazard index was assigned to the fifth class (very high hazard) for all examined sites, as SLR estimates are derived from global-scale datasets whose variation is not significant at regional scale.

Wind data were obtained from the MeteOcean Group for the period 1979–2018 [88], considering 52 grid points distributed along the three Calabrian coastal sectors. The 10 m wind-speed time series were processed to derive prevailing wind directions and intensities, grouping the data into 10° directional sectors and 1 m/s speed classes. From these analyses, both the maximum wind set-up and the exceedance probability of the critical wind velocity required to initiate aeolian sediment transport were estimated, with the latter adopted as a representative index of the process. Wind set-up values at the 54 sampled sites ranged between 0.6 and 17 cm. For aeolian transport, the critical wind velocity () ranged between 10 and 84 m/s Detectable sediment transport capacity was identified at 20 of the 54 sites. The highest exceedance probability (6.9%) occurred at Brancaleone Marina, where the prevailing wind direction is from the southwest (SW) and the maximum observed wind speed reached 28 m/s. With respect to the wind-related hazard index, all sites fell within the first class (very low hazard), except Ferruzzano and Brancaleone, where the percentage of annual hours with active aeolian sediment transport ranged between 5% and 15%.

The mean tidal range was estimated using data from the National Tide Gauge Network (ISPRA) [85] for the period 2010–2021. As only two stations are operational in Calabria (Reggio Calabria and Crotone), the analysis was extended to nearby stations (Catania, Taranto, and Palinuro) to ensure broader spatial coverage. After removing outliers, the data were analyzed annually to determine mean minimum and maximum sea levels and, consequently, the mean tidal range. The analysis yielded mean tidal range values of 0.87 m at Taranto, 0.90 m at Crotone, 0.72 m at Catania, 0.69 m at Reggio Calabria, and 0.88 m at Palinuro. These measurements were then spatially interpolated to assign representative values to the different Calabrian coastal sectors. Specifically, the Taranto value was used for the Upper Ionian coast within the Gulf of Taranto; the Crotone value for most of the Central Ionian sector; the Catania and Reggio Calabria values for the Lower Ionian coast and the Strait of Messina; and the Palinuro value for the Tyrrhenian coastline. All sites therefore exhibit mean tidal ranges of only a few centimetres and below one metre, corresponding to a microtidal regime consistent with Sannino et al. (2015) [104]. As a result, despite minor spatial variations, all locations were classified within the first hazard class for tidal range.

Marine currents in Calabria are generally weak, ranging between 0.4 and 0.7 knots, but reach exceptional values within the Strait of Messina, where mean intensities range from 1 to 2 m/s and peaks reach up to 5 m/s [86]. The hydrodynamics are dominated by semi-diurnal tidal currents, supplemented by drift and gradient currents and by local circulation features such as countercurrents and vortices. These dynamics make the area unique within the Mediterranean and of particular interest for marine energy applications [87]. The marine current index ranges from 1 to 4, reaching its maximum at Porticello in the southernmost sector of the Strait.

The wave climate along the Calabrian coasts was reconstructed using data from the MeteOcean Group (1979–2018) [88], integrated with simulations from the ABRCMaCRO software (3.0 version) for the Strait of Messina. The region was divided into three macro-areas—Tyrrhenian, Ionian, and Strait—based on exposure and fetch. A total of 51 grid points were analyzed (32 along the Ionian and 19 along the Tyrrhenian sectors), while model data were used in the Strait due to insufficient spatial resolution in the original dataset. In the Tyrrhenian Sea, wave directions are concentrated within a few dominant sectors, primarily from the western quadrants (250–310°), with almost no secondary exposure sectors. Conversely, the Ionian coast is exposed to a broader directional range, predominantly from the southeast (100–140°), but with several secondary sectors that increase both variability and hazard. The Crotone sector shows the highest wave energy fluxes (>7000 N/s). The higher hazard levels observed along the Ionian coasts are also supported by the wave statistical parameters, which indicate a more pronounced increase in significant wave heights with return period compared to the Tyrrhenian sectors. Wave run-up values, however, are influenced more strongly by seabed slope than by wave climate, leading to the highest run-up values along the steep coasts of the Strait of Messina. In summary, the Calabrian wave climate exhibits substantial spatial variability: it is more concentrated and energetic along the Tyrrhenian coast, and more complex and potentially hazardous along the Ionian coast, with direct implications for shoreline vulnerability [105]. The wave-climate hazard index estimated for the analyzed sites ranged from moderate (third class) to very high (fifth class), with the highest scores found in the Strait of Messina and Tyrrhenian localities.

As detailed in Section 2.2, the assignment of weights—required for the evaluation of the overall hazard index—was grounded in scientific assessments tailored to the Calabrian coastal context and defined through consultation with regional policymakers and technical experts. The analysis of hazard variables revealed that sea-level rise (SLR) constitutes a critical and non-negligible driver, resulting in all sites being assigned to the highest hazard class. Although regional-scale SLR variations remain limited, its cumulative long-term effects are expected to intensify both erosion and inundation hazards, highlighting the need to integrate climate projections into regional planning. For this reason, a weight of 20% was assigned to this variable. The wave climate emerged as the dominant forcing agent, particularly along the Tyrrhenian coast and within the Strait of Messina, where energetic sea states, extended fetch, and steep bathymetric gradients combine to enhance wave run-up and coastal retreat potential. Consequently, this variable was assigned the highest weight, equal to 50%. By contrast, wind and tidal indices were found to be less influential, consistent with the region’s microtidal regime and the limited relevance of aeolian sediment transport. Similarly, the hazard associated with marine currents is generally low, except within the Strait of Messina. For these reasons, each of these three variables was assigned a weight of 10%.

Accordingly, the overall Coastal Hazard Index () was formulated as a weighted composite of five contributing factors: wave climate (50%), sea-level rise (20%), tidal range (10%), marine currents (10%), and wind (10%) (Table 10). A hazard classification was then established based on the resulting index values, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 10.

Summary of all Hazard variables, with assigned weights and justification.

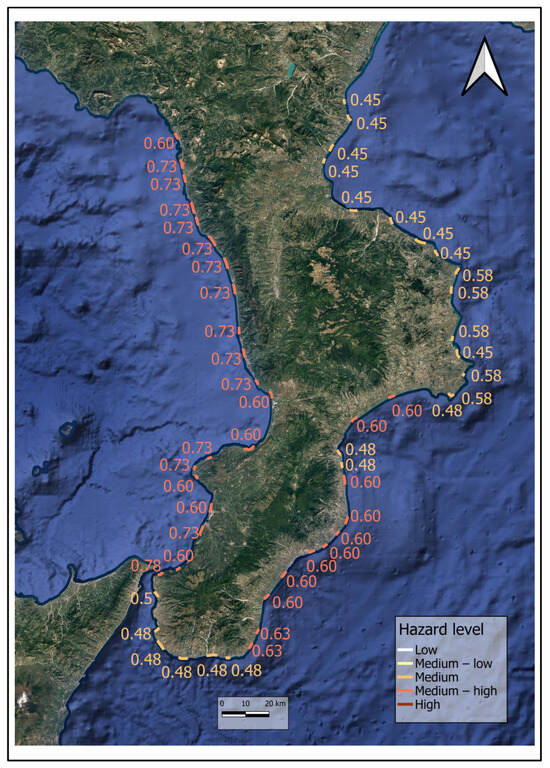

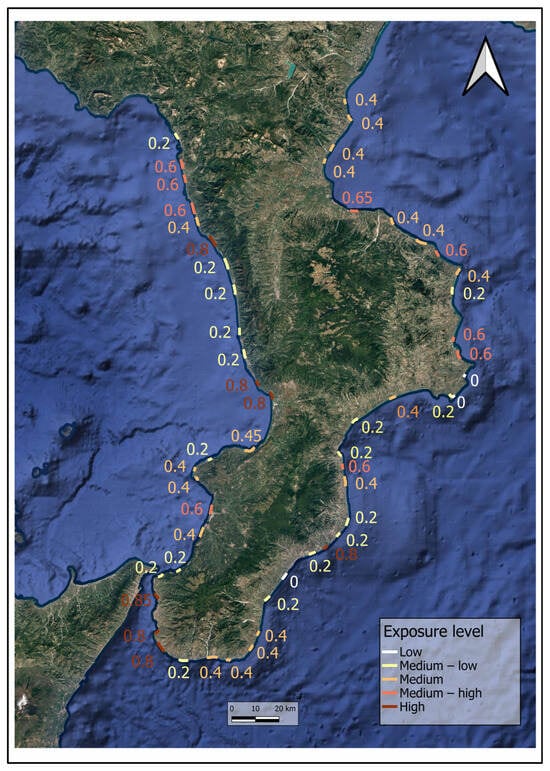

Table 11 reports the normalized values of the overall hazard index obtained for each analyzed site, calculated using Equation (2) and weighted according to the coefficients provided in Table 10, together with their corresponding hazard classification described in Table 4. The results indicate medium-to-high hazard levels across all Tyrrhenian sites and variable levels, from medium to medium–high, along the Ionian coast and within the Strait of Messina (Figure 4).

Table 11.

Normalized values of the overall coastal hazard index calculated for each analyzed site according to the proposed methodology.

Figure 4.

Hazard map. The legend shows the different hazard levels using a color scale, while the numbers displayed in the figure, shown in colors corresponding to the hazard level, indicate the hazard index values calculated for the examined locations.

3.2. Coastal Vulnerability

Regarding the vulnerability variables analyzed, all the selected sites consist of sandy beaches and therefore fall within the fifth (highest) vulnerability class for the Coastal Type index.

The Emerged Coastal Morphology Index (ECM) ranges between 2.5 and 5, with the highest value observed at Calopezzati. Sedimentological analysis based on OKEANOS (2003) data [90] shows marked variability among the three macro-areas. Along the Ionian coast, emerged beaches are mainly composed of pebbles, gravel, and coarse sand, while seabed sediments are more heterogeneous, ranging from coarse to fine materials (Dn50 up to 0.1 mm). In the Strait of Messina, emerged beaches contain very coarse sands and pebbles, whereas the seabed consists of fine sands (0.13–0.18 mm). Along the Tyrrhenian coast, emerged sediments are predominantly gravelly and coarse, gradually transitioning to medium and fine sands at greater depths (up to 0.05 mm in the central Tyrrhenian sector). Satellite-based morphological analysis revealed beach widths between 13 m and more than 100 m, with slopes ranging from 2% to 17%. Wider coastal plains correspond to broader and gentler beaches, while narrow plains generally host steeper and narrower beach profiles.

For the Submerged Coastal Morphology Index (SCM), which represents seabed slope, most sites fall within the first or second vulnerability classes. Exceptions include Rossano (Ionian coast) and the Strait of Messina, both showing steeper profiles. Bathymetric analysis based on EMODnet-Bathymetry data [91] revealed average seabed slopes of 2–3% for both Tyrrhenian and Ionian sectors, except at Rossano (10%). The Strait of Messina displays much steeper slopes, exceeding 20%, in keeping with its distinctive geomorphological setting.

The Shoreline Evolutionary Trend Index (SET) spans all vulnerability classes: 13 sites show shoreline advancement (class 1), 28 sites are stable (class 2), 6 sites experience mild erosion (class 3), 6 sites show intense erosion (class 4), and 1 site experiences severe erosion (class 5). The shoreline evolution of Calabria was reconstructed through comparison of historical shorelines, orthophotos, and satellite imagery [73,92], analyzing over 700 transects and calculating Net Shoreline Movement (NSM) and End Point Rate (EPR). Results indicate overall long-term stability, although significant local erosion persists. The highest recent erosion rate was recorded at Marina di Caulonia (≈6 m/year), followed by Calopezzati, San Ferdinando, and Belmonte Marina (≈3 m/year). Short-term analyses reveal strong erosion at Gizzeria Lido (5.5 m/year) and Crotone-Zigari (3.6 m/year). Shoreline advancement is generally limited (<1 m/year), except at Badolato, where harbour construction altered local sediment dynamics. Overall, Calabria’s coastline is largely stable, but local vulnerabilities remain due to anthropogenic pressure and morphodynamic processes [58].

The Dune System (DS) and Vegetation (V) indices vary between 1.9–5 and 2.4–5, respectively. The highest values correspond to areas where these natural protective systems are absent. Dune and vegetation assessments using satellite imagery identified dunes up to 7 m high and 94 m wide (Monasterace, Badolato), and vegetation widths up to 86 m (Badolato) or 80% coverage (Isola di Capo Rizzuto). Approximately 30 Posidonia oceanica meadows were mapped, mostly along the Ionian coast and within protected areas (Isola Capo Rizzuto, Costa degli Dei, Upper Tyrrhenian), based on MEDISEH project outputs [93]. These habitats highlight both ecological significance and the better conservation condition of less urbanized coasts. Anthropogenic pressure has drastically reduced dune systems, particularly along the Tyrrhenian coast, intensifying erosion. For example, urbanization at Tortora has caused shoreline retreat, whereas partially preserved dunes at Villapiana have promoted shoreline progradation [106].

Subsidence affects large parts of the Ionian coast and some Tyrrhenian sectors, with rates from a few mm/year to over 20 mm/year. The phenomenon is associated with tectonic activity and groundwater extraction in Sibari, natural processes and hydrocarbon extraction in Crotone, and agricultural and industrial water withdrawal in Gioia Tauro [94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103]. Subsidence amplifies coastal vulnerability and threatens both archeological heritage and modern settlements. Resulting vulnerability index values (S) range from 1 to 4, with the highest levels recorded near the Sibari plain (Villapiana Lido, Rossano) and the Gioia Tauro plain (Palmi, San Ferdinando).

Due to Calabria’s steep orography, with mountain ranges close to the coast, numerous small, steep catchments are characterized by flash floods and intense sediment transport [107]. A total of 262 catchments (>4 km2 or of specific interest) were analyzed, estimating mean annual volumes of eroded material using the Gavrilovic model [108] in a GIS environment with morphometric, pluviometric, thermometric, and land-use data [89]. The largest catchments are the Crati (≈2500 km2), Neto (≈1100 km2), Mesima (≈800 km2), and Lao (≈600 km2). The highest fluvial sediment yields were estimated for the Lao (132,229 m3/year), Neto (107,877 m3/year), and Allaro (102,671 m3/year) rivers. The longshore sediment transport was estimated using the Tomasicchio et al. (2013) model [109], implemented in MATLAB (R2018b) and applied to meteomarine and sedimentological data from the 54 study sites. The model provided both magnitude and direction of transport, offering key insights into coastal dynamics. The results show wide spatial variability, from 2815 m3/year at Villapiana Lido to 241,000 m3/year at Cirò Marina, confirming the strong influence of local wave climate, sediment texture, and geomorphological setting on sediment transport patterns. The resulting Sediment Transport Index (ST)—representing the balance between fluvial sediment inputs and longshore sediment removal—spans all vulnerability classes, with the highest values recorded in several Ionian and Tyrrhenian sites.

For the Coastal Defence Structure (CDS) and Port Structure (PS) indices, the obtained values fall within medium–high and medium–low vulnerability classes, respectively, where such structures exist. Satellite imagery enabled classification of defence types, geometry, and conservation state. Among the 54 sites, 29 are protected by defences, with protected shoreline lengths ranging from 2.5% (Belmonte Marina) to 48% (San Lucido). Identified structures include groynes, emerged and submerged barriers, and mixed systems. Twenty-four ports were surveyed and measured relative to the 1954 shoreline; the largest is the new port of Crotone (1122 m), followed by Cetraro (489 m), Cariati (457 m), and Roccella Ionica (415 m) [110].

For the Coastal Anthropization Index (CA), all sites fall within the highest vulnerability class, as shoreline urbanization is generally low (<20%), except Marina di Belvedere and Sangineto Lido, which fall into the fourth class (21% and 29.6%, respectively).

Overall, vulnerability patterns are more heterogeneous and strongly influenced by geomorphological and anthropogenic conditions. The predominance of sandy beaches, high subsidence rates in specific coastal plains (e.g., Sibari and Gioia Tauro), and the widespread degradation of natural buffers such as dunes and vegetation collectively drive elevated vulnerability across much of the region. Coastal defence structures and port facilities may offer localized protection, but they often disrupt sediment transport and generate secondary morphological imbalances. As outlined in Section 2.2 and based on scientific evaluations calibrated for the Calabrian context and refined through consultation with regional policymakers and technical experts, all sub-indices were assigned equal weights (1/11) (Table 12). This choice reflects the fact that the relative importance of each variable was already incorporated into the definition of its vulnerability classes.

Table 12.

Summary of all Vulnerability variables, with assigned weights and justification. All variables are assigned equal weight (1/11), as their relative influence is already embedded in the classification thresholds and because vulnerability reflects a multidisciplinary set of factors with comparable importance.

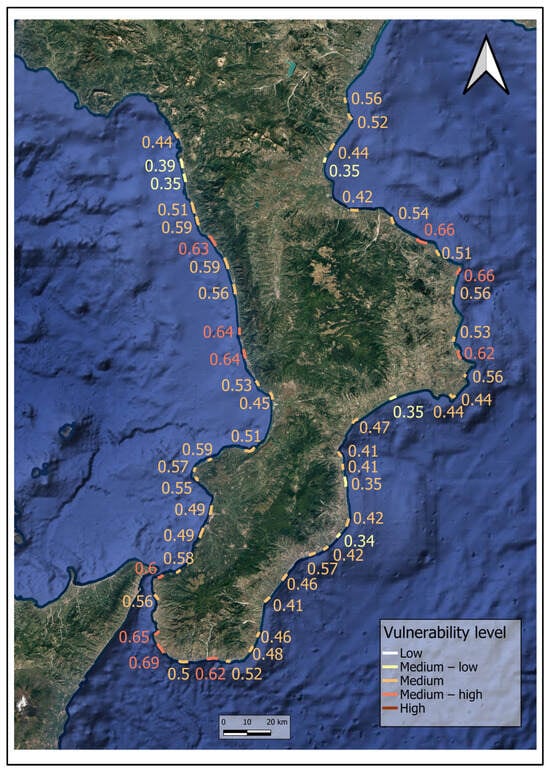

The overall Coastal Vulnerability Index () was therefore calculated as the arithmetic mean of eleven sub-indices representing: coastal type, emerged and submerged morphology, sediment budget, shoreline evolution, subsidence, vegetation, dune systems, coastal defence structures, port infrastructures, and degree of anthropization. Vulnerability classes were subsequently defined from the resulting index values, as reported in Table 3.

Table 13 reports the normalized values of the overall vulnerability index obtained for each site, calculated using Equation (3) and weighted according to the coefficients provided in Table 12, together with the corresponding vulnerability classification described in Table 5. The results indicate moderate vulnerability for most sites, medium–low for four Ionian and two Tyrrhenian sites, and medium–high for five Ionian, three Tyrrhenian, and two Strait of Messina sites (Figure 5).

Table 13.

Normalized values of the overall coastal vulnerability index calculated for each analyzed site according to the proposed methodology.

Figure 5.

Vulnerability map. The legend shows the different vulnerability levels using a color scale, while the numbers displayed in the figure, shown in colors corresponding to the vulnerability level, indicate the vulnerability index values calculated for the examined locations.

3.3. Coastal Hazard-Area

For hazard-area assessment, total levels were estimated by summing the maximum contributions from wind set-up, barometric set-up, astronomical tide, wave run-up and set-up (TR = 100 years), and the projected sea-level rise under the IPCC SSP5–8.5 scenario [84]. The resulting total water levels vary according to local coastal slope, ranging from 3.15 m at Villapiana Lido to 7.82 m at Lazzaro. Hazard areas were delineated in QGIS using 5 m-resolution regional DTMs [73], considering both total water levels and the linear extent of each coastal segment. The mapped hazard areas range from 1.43 km2 at Vibo Marina—the largest—to 0.006 km2 at Isola di Capo Rizzuto–Marinella (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Example of a mapped coastal hazard area detected in Vibo Marina.

3.4. Coastal Exposure

Regarding exposure, most sites show low values of resident population within hazard zones. However, land use associated with tourism and coastal development produces high exposure scores in several areas, particularly along the Tyrrhenian coast. In particular, analysis of the resident population within the hazard area shows that almost all surveyed localities fall within the lowest exposure class, with the exception of Rossano, Gallico, and Vibo Marina. In contrast, the land use index displays a wider distribution across all five exposure classes, with the highest values recorded at Caulonia Marina, Lazzaro, Pellaro, Gallico, Gizzeria Lido, Falerna Marina, and Cetraro Marina.

Overall, the exposure indices exhibit marked spatial variability. The results indicate that exposure is influenced not only by permanent population density but also by the intensity of anthropogenic pressure and coastal land use—particularly where these pressures overlap with inherently unstable natural settings. As described in Section 2.2, and following scientific assessments and consultations with regional policymakers, a higher weight (80%) was assigned to the land-use exposure index, as it captures a broad range of exposed assets, including urban, industrial, and commercial areas, transport infrastructure, and sites of historical, archeological, or environmental value. Consequently, a weight of 20% was assigned to the index representing resident population within hazard zones, reflecting the generally low population density observed across the study area (Table 14). Once computed, the overall Coastal Exposure Index () was classified according to the threshold values reported in Table 3.

Table 14.

Summary of all Exposure variables, with assigned weights and justification.

Table 15 presents the normalized overall exposure index values for each site, calculated using Equation (4) and weighted according to the coefficients in Table 14, together with their exposure classification described in Table 6. The results reveal considerable spatial variability: three Ionian sites exhibit low exposure, while seven sites—mainly along the Tyrrhenian coast—display high exposure levels (Figure 7).

Table 15.

Normalized values of the overall coastal exposure index calculated for each analyzed site according to the proposed methodology.

Figure 7.

Exposure map. The legend shows the different exposure levels using a color scale, while the numbers displayed in the figure, shown in colors corresponding to the exposure level, indicate the exposure index values calculated for the examined locations.

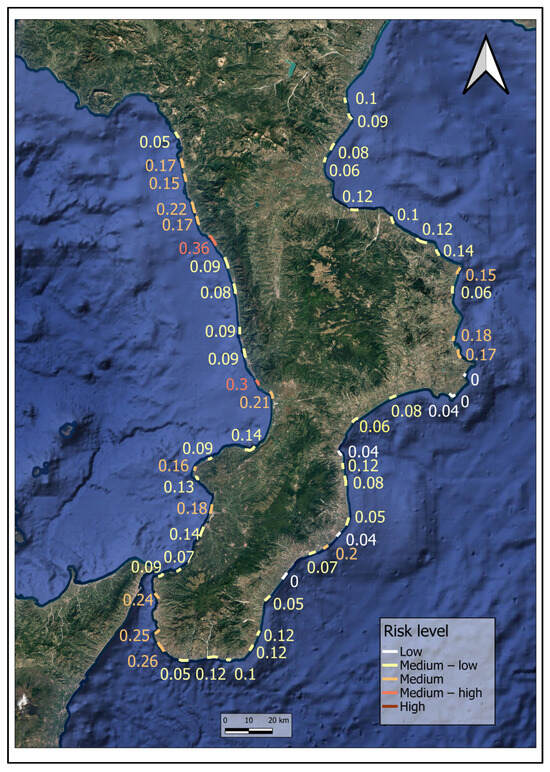

3.5. Coastal Risk

The integration of the three components—hazard, vulnerability, and exposure—resulted in the definition of the coastal risk index (), providing an articulated overview of coastal risk across Calabria. The results—shown in Table 16—identify 6 sites with low risk (all located along the Ionian coast), 32 with medium–low risk, 14 with medium risk, and 2 sites with medium–high risk (Falerna Marina and Cetraro Marina), both situated along the Tyrrhenian coast and characterized by high urbanization (Figure 8). These findings highlight that coastal risk is not uniformly distributed but depends on the combined influence of natural conditions and anthropogenic pressure.

Table 16.

Values of the coastal risk index calculated for each analyzed site according to the proposed methodology.

Figure 8.

Risk map. The legend shows the different risk levels using a color scale, while the numbers displayed in the figure, shown in colors corresponding to the risk level, indicate the risk index values calculated for the examined locations.

3.6. Validation Results

The validation of the proposed methodology was based on a broad set of independent datasets and on a multilevel comparison between modelled outcomes and empirical evidence. Multitemporal shoreline data, satellite imagery, and digital terrain models were employed, serving a dual purpose: providing operational inputs to the model and offering an objective reference for verifying its spatial and interpretative consistency. Validation procedures were applied primarily to coastal sectors with the most detailed geomorphological and management-related documentation, with particular focus on the Tyrrhenian coast and on the sites of Falerna Marina and Cetraro Marina. These sites were selected as independent control points due to the recurrent erosive processes consistently reported in scientific literature, technical assessments, and reliable journalistic sources. Both locations are recognized as among the most vulnerable segments of the Tyrrhenian coast of Calabria, characterized by chronic and intensifying erosion. At Falerna, recent storm events have caused substantial shoreline retreat, beach loss, and recurrent damage to coastal infrastructure (Figure 9a); at Cetraro, erosion has almost entirely removed the beach, directly exposing coastal works and touristic facilities to wave action. In both cases, beach regression has led to the reduction and fragmentation of coastal vegetation communities, in agreement with the vulnerability levels estimated by the model and with satellite evidence (Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

(a) Erosional events and storm-induced damages recorded in Falerna during the winter seasons of 2020 and 2023 (source: lametino.it). (b) Erosional processes and storm-induced damages observed in Cetraro in 2022 (source: cosenza.gazzettadelsud.it).

These observations are consistent with previous studies documenting the vulnerability of the Calabrian Tyrrhenian coastline. Ietto et al. (2018) [111] show that very high-risk sectors generally correspond to narrow, heavily urbanized sandy beaches, particularly in the northern sector, where hard engineering structures and intense anthropogenic pressures exacerbate erosive processes; the same study attributes the marked criticality of Cetraro to the presence of the harbour basin. Bellotti et al. (2008) [112] further highlight how hard structures not integrated into sustainable sediment management strategies can aggravate erosion, as observed at Belvedere Marittimo. D’Alessandro et al. (2011) [113] report that the system of T-groins constructed between Paola and San Lucido, while protecting the railway line, interrupted alongshore sediment transport, causing severe downdrift erosion with shoreline retreats of up to 30 m and ineffective mitigation interventions. The consistency between these independent lines of evidence and the model results—identifying the same sectors as high or very high risk—provides strong confirmation of the framework’s ability to faithfully reproduce real-world erosive dynamics.

The validation method integrates three independent components: the modelled risk classes, observed shoreline trends derived from the multitemporal SET index, and field-based evidence of persistent erosive criticalities. The coherence among these components enabled model validation across the selected sites. Numerical results confirm a high agreement between estimated risk and observed erosion: locations with the highest risk values (Falerna Marina = 0.30; Cetraro Marina = 0.36) exhibit substantial shoreline retreat rates (up to –3 m/year and –2 m/year, respectively) and pronounced sediment deficits. Similarly, in intensely urbanized sectors such as Belvedere and Sangineto, or in areas characterized by strong sediment dynamics such as Cirò Marina, a clear correspondence emerges among anthropogenic pressure, erosive processes, and assigned risk classes.

The reliability of the model is supported by quantitative metrics that demonstrate a high degree of coherence between observations and simulated outputs. Across the 54 coastal sites analyzed, 22 erosional hotspots were identified, characterized by moderate, intense, or severe shoreline retreat.

The Spatial Concordance Index (SCI) yielded a value of 0.618, indicating that 61.8% of the sites exhibit agreement between the modelled risk class and the observed shoreline dynamics. Furthermore, more than 80% of the Tyrrhenian sectors classified as medium or medium-high risk correspond to erosive or highly erosive SET classes, confirming the model’s strong capability to reproduce the spatial distribution of coastal vulnerabilities.

The component-wise consistency analysis highlights particularly strong coherence within the physical and morphological domains: both the Hazard Consistency Index and the Vulnerability Consistency Index reach values of 0.955. This indicates that in over 95% of the sites affected by consolidated erosion, marine forcing conditions and morpho-sedimentary vulnerability are consistently high, reinforcing the robustness of the model in identifying dynamically fragile areas.

Conversely, the socio-economic component shows more moderate agreement (Exposure Consistency Index = 0.591), reflecting that many erosional stretches do not coincide with highly urbanized or infrastructure-dense areas. Exposure therefore acts more as a local amplifier of risk rather than a direct driver of erosional processes.

Overall, the convergence between model outputs, empirical evidence, and established scientific literature supports the validity of the proposed framework and demonstrates its effectiveness in robustly identifying the main erosion-related criticalities along the Calabrian coastline.

3.7. Sensitivity Analysis

To complete the assessment of the stability of the proposed index, a concise yet formally structured sensitivity analysis was performed, focusing on the three main components that define the Coastal Risk Index (hazard, vulnerability, and exposure). Although the methodological framework is inherently robust—due to the internal calibration of the sub-indices, the use of empirically defined reference classes, and the consistency of the adopted weights—the analysis enabled a quantitative evaluation of how moderate variations in weighting influence the final index results.

Six representative sites were selected to capture the main morphological settings and the full range of identified risk classes: two high-risk Tyrrhenian sites (Falerna, site 44; Cetraro, site 49), two medium-risk Ionian sites (Cirò Marina, site 9; Melito Porto Salvo, site 31), and two low-risk sites (Locri, site 25; Isola Capo Rizzuto–Le Castella, site 15). For each component, the weight of the dominant variable—wave climate for H, shoreline evolution for V, and infrastructure for E—was modified by ±10%, after which the complete set of weights was renormalized to ensure that their sum remained equal to 1.

The resulting changes in the index range between 1% and 6%, and in no case did these variations produce a shift in risk class, even for sites located near class thresholds (e.g., from medium to medium–high). The high-risk Tyrrhenian sites (Falerna and Cetraro) show the lowest sensitivity, with variations below 3%, reflecting the strong internal coherence among the H, V, and E components. Low-risk sites display slightly higher variability, although remaining within their initial risk class.

The observed stability aligns with the structural design of the index. The sub-indices are normalized according to CRI-MED standards, and vulnerability variables are organized in multilayer hierarchies integrating key morphological and dynamic attributes such as dune systems, vegetation cover, and coastal evolution. Hazard components exhibit limited regional variability—as highlighted by sea-level rise (SLR) consistently falling into the highest category across the study area—while exposure generally shows low to moderate values throughout most Calabrian sites, with only a few localized increases. These characteristics collectively contribute to the index exhibiting low sensitivity to moderate changes in the assigned weights.

Overall, the sensitivity analysis quantitatively confirms the structural robustness of the index and demonstrates that reasonable uncertainties in the weighting assumptions do not alter either the final risk classification or the spatial pattern of coastal risk.

4. Discussion

The new methodology proposed for coastal risk assessment represents a substantial improvement over the approach adopted in the Master Plan for Mitigation Interventions Against Coastal Erosion in Calabria (2013) [16]. The updated framework is more rigorously structured and fully consistent with the classical definition of risk as the product of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure. It also includes the delineation of a hazard zone in accordance with European guidelines, together with several additional factors not previously considered in coastal erosion assessments for the Calabria region. Compared with the 2013 Master Plan, the new methodology significantly enhances the wave climate index by accounting for the influence of secondary wave exposure sectors and by incorporating run-up variations as a function of return period, rather than relying solely on seabed slope. In addition, the methodology integrates multiple hazard components beyond wave action, including sea-level rise, tidal regime, marine currents—particularly relevant in the Strait of Messina—and wind-driven deflation processes. The explicit integration of vulnerability factors related to coastal vegetation and dune systems represents a further methodological advancement, as these elements—crucial for coastal resilience—have undergone progressive degradation since the 1950s due to increasing anthropogenic pressures. Incorporating the 1954 shoreline into the SET index calculation enables the capture of long-term evolutionary dynamics and the assessment of human-induced transformations that have occurred since the mid-twentieth century; its lower accuracy compared to more recent datasets is appropriately accounted for by assigning it a reduced weight in the rate computation. The strong contrast between highly urbanized Tyrrhenian sectors and the less developed Ionian coast further illustrates the decisive role of human activities in amplifying coastal susceptibility. Urban growth and the expansion of coastal infrastructure have altered natural shoreline processes, increasing exposure to erosive forces [114]. Among the strengths of the proposed methodology is the high level of detail employed in the computation of vulnerability indices. For example, the vegetation index incorporates information on vegetation density, while the dune system index considers geometric characteristics such as dune height and spatial extent. Even for coastal and port defence structures—already partially addressed in the 2013 Master Plan—the methodological detail has been substantially enhanced. The updated indices now account for the spatial extent of port basins, the typology of defence structures, their geometric and structural characteristics, their relative position with respect to the shoreline, their exposure to wave action, and their current state of conservation. Collectively, these improvements provide regional decision-makers with a more comprehensive and reliable tool for coastal management.

In comparison with the CRI-MED framework developed by Satta et al. (2017) [13], which provided the conceptual basis for the formulation of the present risk index, the proposed methodology represents a marked refinement, particularly concerning applications at regional and local scales. Whereas CRI-MED was conceived for supra-regional assessments and thus emphasizes methodological generality and cross-country comparability within the Mediterranean basin, it necessarily reduces the level of detail devoted to the local processes governing coastal morphodynamics. The methodology introduced in this study addresses this limitation by adopting a more detailed and physically grounded characterization of coastal erosion risk. Specifically, it employs a rigorous definition of the hazard zone based on run-up, set-up, and sea-level rise scenarios, and integrates a suite of geomorphological and anthropogenic variables that are typically underrepresented in large-scale approaches. These include fluvial and longshore sediment transport, the morphology of emerged and submerged coastal sectors, the presence of vegetation and dune systems, coastal and port defence structures, and the degree of shoreline imperviousness. The incorporation of these components enhances the method’s capacity to represent the complexity of erosive dynamics and their spatial heterogeneity, which is particularly relevant in morphologically diverse regions such as Calabria. In addition, the modular structure of the methodology and its full implementation within an open-source GIS environment ensure high levels of transparency, reproducibility, and adaptability. These characteristics render the framework operationally valuable for coastal planning and management, offering an analytical resolution that exceeds that of the more generalized and less detailed approach proposed by Satta et al. (2017) [13].

One of the main advantages of the proposed methodology lies in its high transferability to other coastal contexts, owing to the integration of conceptual and operational components of universal relevance. The overall structure of the risk model, grounded in the consolidated definition of risk as the product of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure, adopts a widely recognized conceptual framework that is readily applicable to a broad range of coastal environments. Similarly, the procedures for normalizing and classifying variables into five classes, derived from the CRI-MED protocol, ensure methodological consistency and international comparability. Several hazard-related variables—including sea-level rise derived from IPCC/NASA projections, the tidal regime classified according to the Hayes (1979) scheme [53], and standard formulations for run-up and set-up—are based on global datasets or well-established engineering criteria and are therefore independent of regional specificities. The conceptual and computational structure of vulnerability, grounded in morphological and sedimentary parameters extensively described in the literature and in classes derived from international methodologies, further strengthens the model’s replicability.

Some parameters that are more strongly dependent on local conditions—such as the morphology of the emerged beach and seabed, the status of dune systems and coastal vegetation, or subsidence rates—require specific calibration using thresholds consistent with the environmental characteristics of the application area. Conversely, the exposure index, based on the distribution of population, infrastructure, and land use, can be easily implemented in any region using standard GIS datasets. Applying the model to different contexts also entails revising the weighting system, which should be adapted according to the relative importance of hydrodynamic forcing in driving erosive processes and the role of territorial characteristics in shaping the overall vulnerability of the system.

The datasets required to apply the methodology in other regions may mirror those used in the Calabrian case study. In particular, satellite imagery and topographic and bathymetric surveys should be as up to date as possible to accurately represent current conditions and reduce uncertainties associated with outdated data. Overall, the proposed methodology is highly exportable and adaptable to a wide range of coastal systems, requiring only limited local calibration.

Compared with the methodologies proposed by Ahmed et al. (2022) [33], Mohamed (2020) [27], and Roy et al. (2021) [29]—which mainly rely on multicriteria approaches based on the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and generalized indicators—the proposed method offers a more physically based representation of coastal processes. It explicitly incorporates key variables often neglected in previous studies, such as fluvial sediment supply, nearshore and onshore morphology, sediment budget, hard protection structures, and coastal ecological features. Together with dynamic parameters (run-up, set-up, and sea-level rise), these factors allow for a more accurate depiction of coastal morphodynamic variability. Overall, the approach provides a more comprehensive and process-oriented assessment, improving the reliability of coastal vulnerability evaluations.

About the management of uncertainties associated with the datasets used, this was addressed through a systematic set of procedures designed to ensure coherence, transparency, and reproducibility throughout the analytical process. All datasets were harmonized and pre-processed within an open-source GIS environment, ensuring uniformity in terms of spatial reference system, resolution, and classification structure. The multitemporal shorelines were digitized and validated, then integrated using a weighted average that explicitly accounts for the different accuracy levels of the sources, thereby helping to limit error propagation. Morphological, hydrodynamic, and sedimentological datasets were resampled into comparable units and classified according to internationally recognized schemes, reducing variability linked to methodological heterogeneity among sources. Quality control was ensured through cross-validation procedures, systematic comparison with field evidence and regional reports, and internal consistency checks among morphodynamic variables. Overall, this integrated approach provides a robust management of uncertainty and strengthens the reliability of the informational framework underpinning the assessment of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure.

Application of the proposed methodology along the Calabrian coastline highlights the complex and spatially heterogeneous nature of coastal erosion risk, as confirmed by the results of this study. This variability is shaped by the combined influence of physical processes, geomorphological configurations, and anthropogenic pressures. The joint analysis of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure components illustrates how their interaction clearly determines the spatial distribution of final risk levels, delineating marked differences among the examined sites. Results for the two Tyrrhenian hotspots, Falerna and Cetraro, show that high values across all components converge to produce medium–high-risk conditions. In these locations, the highly energetic wave climate constitutes the primary hazard factor, while vulnerability is amplified by severe shoreline retreat, persistent sediment deficits, and long-term degradation of dune and vegetation systems. Added to this is high exposure driven by intense coastal urbanization and substantial surface impermeabilization, both of which increase the potential severity of impacts.