Abstract

This study evaluates monthly sea levels during 1993–2023 from four ocean models using tide gauge and altimeter data in the Northwest Atlantic with its shelf seas, including the Gulf of Maine, Scotian Shelf, Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the Newfoundland and Labrador Shelf. The evaluation is carried out for four different aspects: the multi-decadal mean and linear trend, seasonal cycle, and the de-trended and de-seasonalized anomalies. Overall, the high-resolution model with advanced data assimilation (GLORYS12v1) possesses skills in all four aspects. The other three models show different discrepancies in reproducing the observed sea level variations relative to GLORYS12v1. They possess low or no skills for the timing (despite reasonable standard deviations) of sea level anomalies at time scales longer than 20 months along the coast, and at all time scales on the shelf, over the shelf break, and in the deep ocean. Without data assimilation, the models with high and medium resolutions show biases in the time-mean sea levels in the Labrador Sea that can be attributed to the simulated stronger and weaker deep convection (deeper and shallower mixed layer depth), respectively. The medium-resolution model, using a different data assimilation approach than GLORYS12v1, shows biases in the seasonal amplitude and multi-decadal trends.

1. Introduction

Quantifying and predicting variations in sea levels (or sea surface height, hereafter SSH) across various space and time scales have important socioeconomic values, e.g., for ensuring safe navigation and preventing coastal flooding. Among the multiple factors of the earth system, ocean dynamic processes cause significant SSH variations, including at time scales relevant to the natural climate variability and anthropogenic climate change.

The dominant ocean dynamics and the prediction skills of numerical ocean models differ for SSH variations at different locations and time scales. In this study, we focus on SSH variations along the eastern coast of Canada and northern USA and the adjacent Northwest Atlantic (NWA). Along the coast of this region, Greatbatch et al. [1] showed that, at synoptic time scales of 3–10 days, the tide-gauge-observed SSH was well reproduced by a barotropic model with 1/3° × 0.4° resolution in latitude and longitude forced by wind from an atmospheric reanalysis product. Thompson [2] analyzed the monthly tide gauge data during 1950–1975. The de-seasonalized sea level anomalies (hereafter SLAs) showed coherency along the coast of NWA north of Cape Hatteras. A multiple regression analysis was applied. It identified the contributions of the local wind stress that can be interpreted as the wind-forced boundary current along the Nova Scotian shelf and wind setup in the semi-enclosed Gulf of Maine. The annual cycle of SSH not related to wind and the residual was attributed to the variations in the baroclinic boundary current. Recently, Zhai et al. [3] (hereafter Z25) showed that global ocean models (with horizontal resolutions ranging from 0.25° to 0.4° in longitude/latitude) possess fewer skills off the coast of NWA than along the coast of the Northeast Pacific (NEP) in reproducing the annual-mean tide gauge records during 1958–2015. The higher model skills along the NEP coast were interpreted using the results of Lu et al. [4]. This study found that, at time scales of 2–20 months, the de-seasonalized SLAs are highly correlated over the whole shelf of the NEP, due primarily to wind-driven baroclinic dynamics that can be well captured by a high-resolution (nominal 1/36° in longitude/latitude) regional model. Ongoing work of our group (Lu et al., in preparation) suggests that, at time scales from 2 months to multiple decades, the observed coastal SLAs in the NEP can still be well captured by two versions of Canada’s Three Oceans (CTOs) models, analyzed in the present study with nominal horizontal resolutions of 1/12° and 1/4° in longitude/latitude, without including data assimilation.

A more comprehensive evaluation of model skills in reproducing the coastal tide gauge records of NWA was carried out by Piecuch et al. [5] (hereafter P16), focusing on the annual-mean time series during 1980–2010. P16 compared the simulation results from a wind-driven barotropic model with 1° × 1° resolution, and four data-assimilative ocean reanalysis products based on baroclinic models with resolutions of 1° × 1° and 0.4° × 0.25° in longitude and latitude. From Cape Hatteras to the Gulf of Maine, the barotropic model explained about 50% of the variance in the tide gauge data with the inverse barometer (IB) effect removed, and showed as much (if not more) skill than ocean reanalysis products. P16’s results highlighted the importance of barotropic dynamics on SSH variations at interannual and decadal time scales along the coast of NWA, while also showed that the barotropic model underestimated the tide gauge data along the coast of the Scotian Shelf and Gulf of Maine. This underestimation could be due to the coarse resolution of the barotropic model, or the missing baroclinic dynamics, whose importance was suggested by Thompson [2].

The results of P16 and Z25 both showed low skills of baroclinic models at medium or coarse resolutions with data assimilation, in reproducing the annual-mean tide gauge data over multiple decades along the NWA coast. Based on these results, we propose that, at time scales from interannual to multiple decades, SSH variations along the coast of NWA are caused by the combined influences of the wind-driven barotropic dynamics (possibly to a large degree) and other dynamic processes included in the fully baroclinic ocean models. While the baroclinic ocean models should effectively capture the wind-driven barotropic dynamics, they may have difficulty in accurately capturing the baroclinic dynamics, which is influenced by the strong nonlinear processes in the region. Inaccuracy in capturing the nonlinear processes reduces the skills of the baroclinic models in reproducing the tide gauge observations. In the deep waters of the NWA, strong nonlinear ocean processes include the variability of the Gulf Stream/North Atlantic Current (GS/NAC) and their interaction with the Labrador Current, the strong eddy activities, etc. These deep ocean nonlinear processes shall affect SSH variations on the shelf and along the coast. Furthermore, the baroclinic processes caused by local forcing on the shelf and along the coast may also contain nonlinear components, e.g., the separation of the Nova Scotian Current from the coast.

The results of previous studies such as P16 and Z25 left the following question unanswered regarding the model skills of SSH variations at interannual and longer scales: Can better skills be achieved by increasing the model resolution, or by other data assimilative ocean reanalysis products that differ from the four analyzed by P16? In this study, we try to answer this question by analyzing the monthly SSH during 1993–2023 from four models through comparing their skills in reproducing the observed SSH from tide gauges and altimeter data. The four models differ in spatial resolution (eddy permitting vs. eddy resolving), and with and without ocean data assimilation (Table 1). The analysis will evaluate the model skills at different time scales, i.e., from a few months to multiple decades. We expect that the results of this study will improve understanding of the dynamics and predictability of variations in SSH (and also ocean circulation and hydrography) in this region and suggest further needs to improve ocean models and data assimilation.

Table 1.

Description of the model products analyzed in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

The observed sea levels are the monthly data from tide gauge records and from altimeter measurements. The data from 8 representative tide gauges (locations shown in Figure 1a and names listed in Table 2) are obtained from the Permanent Service for Mean Sea Level (https://psmsl.org accessed on 20 December 2024). Station Quebec (Lauzon) has no data after 2013. The data at Halifax are merged from records at the previous site in Halifax Harbor and at the new site in Bedford Basin. The difference between the vertical datums of the two sites is corrected by calculating the difference between the observed records averaged over their overlapping period (from 2008 to 2012). The altimeter data are the gridded SLA obtained from the website of the Copernicus Climate Change Service (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/satellite-sea-level-global?tab=documentation accessed on 6 December 2024), with a spatial resolution of 0.25° in longitude and latitude. The altimetry SLA is computed with respect to the 1993–2012 mean. The uncertainty in the globally averaged sea level trend is of the order of 0.3 mm/year at a 90% confidence interval [6]. The uncertainty of the regional sea level trend related to the instrumental observing system ranges from 0.78 to 1.22 mm/year [7]. Sea level errors for mesoscale signals vary with variance from 1 cm2 in low-variability areas to 20.89 cm2 in high-variability areas [8].

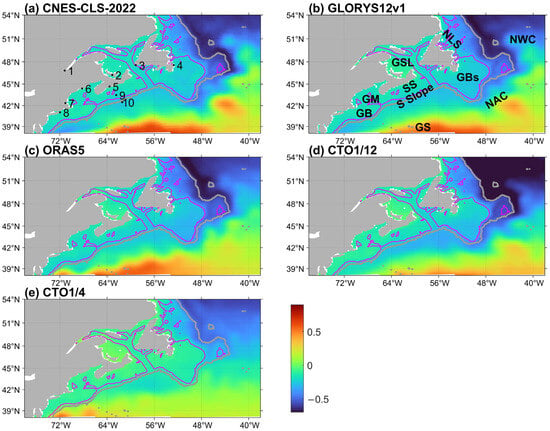

Figure 1.

MDT (m) from (a) the CNES-CLS-2022 product, (b) GLORYS12v1, (c) ORAS5, (d) CTO1/12, and (e) CTO1/4, all representing the time-averaging over 1993–2012. The area-mean value in each panel is removed. Magenta and gray contours denote the 200 m and 2000 m isobaths. Panel (a) also shows locations of the 10 representative sites for time series analyses (Table 2). Panel (b) shows the abbreviations of geographic locations: NLS (Newfoundland and Labrador Shelf), GBs (Grand Banks), NWC (Northwest Corner), GSL (Gulf of St. Lawrence), SS (Scotian Shelf), S Slope (Scotian Slope), GM (Gulf of Maine), GB (Georges Bank), and GS/NAC (Gulf Stream/North Atlantic Current). Note that all these quantities shown do not include the contribution of IB. The CNES-CLS-2022 GLORYS12v1, ORAS5, and CTO1/12 data are all interpolated to the CTO1/4 grids for presenting in these spatial maps.

Table 2.

The mean seasonal cycle of SSH during 1993–2023: amplitude (m) and phase (month when maximum SSH is reached, 1–12 corresponding to January–December), upper and lower row in each data box, respectively, at 10 sites shown in Figure 1a, from observations (tide gauges records at sites 1–8 and altimeter data at sites 9 and 10) and from four models.

The ocean’s mean dynamic topography (MDT) is the height of the mean sea surface above the geoid. The CNES-CLS-2022 MDT product with a horizontal resolution of 0.125° in longitude/latitude is obtained from the Copernicus Marine Services (https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_MDT_008_063/description accessed on 11 December 2024). This MDT product represents the time-mean SSH over 1993–2012. It is produced through synthesizing multiple sources of satellite remote sensing and in situ observational data, and ocean and geoid models. This MDT product can be directly compared with that based on the time-mean SSH from models during 1993–2012 [9].

Two ocean reanalysis products are obtained from the Copernicus Data Store, including ORAS5 (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-oras5?tab=overview accessed on 12 January 2024) and GLORYS12v1 (https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030/description accessed on 8 September 2025). ORAS5 is based on an ocean model with a 1/4° horizontal resolution and a maximum of 75 vertical geopotential z-levels [10]. GLORYS12v1 is based on an ocean model with a 1/12° horizontal resolution and a maximum of 50 z-levels [11]). Both products are produced through assimilating multiple types of observational data, including the in situ temperature and salinity vertical profiles, and satellite remote sensing of sea-ice concentration, sea surface temperature, SLAs along the altimeter tracks, etc. ORAS5 does not assimilate altimeter data outside the 50° N/S latitude bands and in the regions shallower than 500 m. ORAS5 uses the variational data assimilation method NEMOVAR [12,13] in its 3D-Var FGAT (first guess at appropriate time) configuration. GLORYS12v1’s data assimilation scheme is a reduced-order Kalman filter derived from a singular evolutive extended Kalman (SEEK) filter [14] with a three-dimensional multivariate background error covariance matrix and a 7-day assimilation cycle. The ocean model of ORAS5 takes the surface atmospheric forcing from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) reanalysis ERA-40 from 1958 to 1978 and ERA-Interim from 1979 to 2014, and ECMWF operational atmospheric forecasts from 2015 onwards. The GLORYS12V1 product covers the altimetry era (1993 onward). GLORYS12v1 uses surface atmospheric forcing from ECMWF ERA-Interim during 1993–2018 and ERA5 reanalysis since 2019.

The two ocean models without including data assimilation cover the same domain of the North Atlantic (north of 7° N), the whole Arctic Ocean, and the North Pacific (north of 45° N). This configuration is referred to as Canada’s Three Oceans (CTOs), having a maximum of 75 z-levels. The models differ in horizontal resolution, at nominal 1/12° and ¼° in longitude and latitude, and hence are referred to as CTO1/12 and CTO1/4, respectively. The CTO models are based on version 3.6 of the Nucleus for European Modelling of the Ocean (NEMO; Madec and the NEMO team 2016; https://www.nemo-ocean.eu accessed on 1 October 2020) and version 3 of the Louvain-la-Neuve sea-ice Model (LIM3) [15,16]. The CTO configurations are updated from the previously developed versions described by MacDermid et al. [17]. Major updates include (1) extending the open boundary in the North Atlantic from 26° N to 7° N, and (2) modifying the model bathymetry using the GEBCO 2023 version and the bathymetry of two regional models (for the Northeast Pacific and Northwest Atlantic, respectively) with 1/36° horizontal resolution [4,18]. The simulations of the two CTO models start on 16 January 1958, driven by surface atmospheric forcing from the ECMWF reanalysis ERA5. The initial condition and the non-tidal component of the lateral open boundary condition are set with inputs from ORAS5. The land/sea mask is applied to ERA5 forcing in CTO1/4. Finally, the horizontal momentum mixing is parameterized using the bi-Laplacian scheme with the eddy viscosity set as −1011 m4/s for CTO1/4 and −2 × 1010 m4/s for CTO1/12. The horizontal mixing for temperature and salinity is parameterized using the Laplacian scheme with eddy diffusivity set as 300 m2/s for CTO1/4 and 150 m2/s for CTO1/12.

Sea levels from tide gauge data and the solutions of CTO1/12 and CTO1/4 include the contributions of tides and the effect of the sea level pressure (SLP), namely the inverse barometer (IB) response. By using the monthly mean data, the tidal signals are mostly removed. The IB response is computed as , where is the sea level pressure from ERA5, overbar denotes spatial average over the surface of the global ocean (set as a constant in our analysis), g is acceleration due to gravity, and is a constant reference ocean density. The IB response is removed from the sea levels from the tide gauge data and the outputs of the two CTO models. Tides and IB response have been already removed from the altimeter data, and are not included in the solutions of ORAS5 and GLORYS12v1. The dynamic atmospheric correction (DAC) applied to the altimeter data [19] is a combination of the high frequencies (HFs) of a barotropic ocean model forced by atmospheric pressure and wind and the low frequencies (LFs) of the inverse barometer, with a filtering cutting-period of 20 days to separate HFs and LFs. The DAC is needed to correct the aliasing of the high frequency oceanic signals (badly sampled by altimeter measurements) into the lower frequency band containing the ocean variability signals related to climate change, mesoscale activities, etc.

3. Results

In this study, we analyze sea level variations during 1993–2023 when altimeter data and GLORYS12v1 are available. The tide gauge data and model results of ORAS5, CTO1/12, and CTO1/4 prior to 1993 are not analyzed. One reason for choosing this analysis duration is that, since 1993, the available altimeter data enable much more accurate quantification of SSH variations, and provide an important dataset for model evaluation and data assimilation. For example, the multi-decadal sea level trend of the global mean sea level (GMSL) rise can be quite accurately estimated, e.g., as 3.27 ± 0.13 (mean ± confident interval of the least square fit) mm/year during 1993–2023 based on the dataset of Beckley et al. [20] (Dataset accessed [29 September 2025] at https://doi.org/10.5067/GMSLM-TJ152).

The analysis results are presented in two subsections. Section 3.1 presents the qualitative comparison of the spatial distribution of MDT, seasonal cycle, linear trend, and standard deviations of the detrended and de-seasonalized SLAs. Section 3.2 presents the quantitative analysis of the time series at 10 representative sites, including the mean seasonal cycles, linear trends, spectral analysis, and model skills of SLAs.

3.1. Spatial Distributions of Sea Level Variations

3.1.1. Mean Dynamic Topography

Figure 1 compares the MDT based on CNES-CLS-2022 and four ocean models, all representing the time-mean SSH during 1993–2012. The spatial gradients of MDT correspond to the strength of surface geostrophic current. From Figure 1, GLORYS12v1’s MDT shows the closest agreement with CNES-CLS-2022, including the magnitude and locations of high values associated with the Gulf Stream/North Atlantic Current (GS/NAC) at mid-latitudes and the most northern intrusion near 50° N (the “Northwest (NW) Corner”). ORAS5’s MDT also shows close agreement with CNES-CLS-2022. The appearance of high MDT near 72° W, 39° N indicates the Gulf Stream overshooting, and the simulated NW Corner is weaker. These are common deficiencies of medium-and lower-resolution models. CTO1/12 obtains a weaker MDT gradient across GS/NAC, weaker at the NW Corner, and the lowest MDT to the east of the Labrador Current in the subpolar gyre. CTO1/4’s MDT shows the strongest Gulf Stream overshooting, the weakest gradient across GS/NAC and Labrador Current, the weakest at the NW Corner, and the highest MDT in the subpolar gyre.

With the different MDT data being all on the common CTO1/4 model grid, the root-mean-square (rms) difference between the MDT from each model and CNES-CLS-2022, over the study area shown in Figure 1, is computed. The rms values are 0.04, 0.10, 0.15, and 0.17 m for GLORYS12v1, ORAS5, CTO1/12, and CTO1/4, respectively.

Overall, the comparison in Figure 1 suggests that data assimilation leads to more improvement in the simulated MDT than increasing the model resolution. Without data assimilation, CTO1/12 and CTO1/4 show substantial differences with the CNES-CLS-2022 MDT across the Labrador Current and in the subpolar gyre. In the Labrador Sea, the MDT from CTO1/12 and CTO1/4 are lower and higher than the CNES-CLS-2022 MDT, respectively. This can be attributed to the stronger and weaker deep convection in the Labrador Sea in CTO1/12 and CTO1/4, as indicated by the larger and smaller mixed layer depth, respectively.

3.1.2. Mean Seasonal Cycle

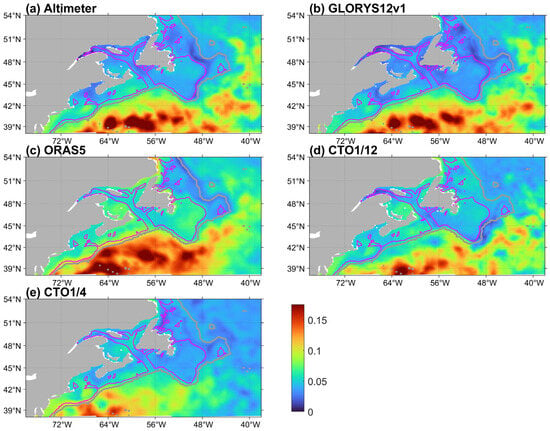

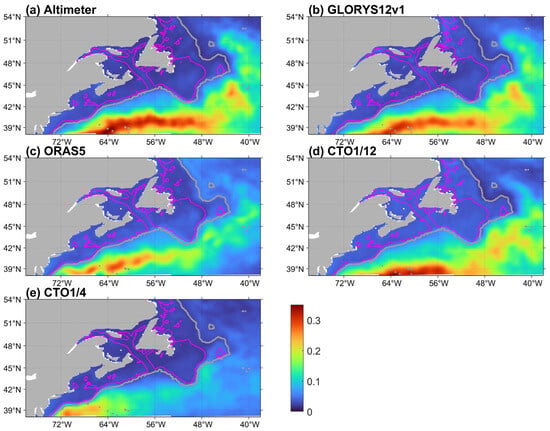

Figure 2 presents the mean seasonal cycles of SSH from altimeter data and models obtained by averaging the monthly SSH in the same months during 1993–2023. First, in the deep ocean around GS/NAC, all data show larger seasonal amplitudes (half the range between the maximum and minimum monthly values) than in the shelf seas. Taking the altimeter data as a reference, GLORYS12v1 obtains nearly the same values and spatial distributions, with the evident influence of meso-scale eddies. ORAS5 shows differences in the spatial distribution, and notably overestimates the amplitude in the Scotian Slope. CTO1/12 shows no overestimation in the Scotian Slope, but smaller amplitudes and a different spatial distribution near the GS/NAC relative to altimeter data and GLORYS12v1. CTO1/4 underestimates the amplitude near the GS/NAC, while showing no overestimation in the Scotian Slope. To the east of the Labrador Shelf in the subpolar gyre, ORAS5 obtains a slightly larger amplitude than the altimeter data and the other three models.

Figure 2.

Similar format as Figure 1 except for the amplitude (m) (half the range between the maximum and minimum monthly values) of the mean annual cycle of SSH during 1993–2023 from (a) altimeter, (b) GLORYS12v1, (c) ORAS5, (d) CTO1/12, and (e) CTO1/4. For the altimeter data, missing data due to sea-ice coverage are omitted when calculating the mean seasonal cycle.

In shelf seas, the seasonal amplitudes show smooth spatial variations, and hence no evident influence of meso-scale eddies from the deep ocean. GLORYS12v1 shows the closest agreement with the altimeter data. ORAS5 obtains the largest amplitude along the coast of Labrador and Newfoundland, and on the Grand Banks, Scotian Shelf, Gulf of Maine, and Georges Bank. In the above regions except Georges Bank, CTO1/12 obtains amplitudes smaller than ORAS5, but larger than the altimeter data and GLORYS12v1. CTO1/4 obtains similar amplitudes as the altimeter data and GLORYS12v1 in the shelf seas. The root-mean-square differences in seasonal amplitudes between the altimeter data and each of the four models over the study area are 0.01, 0.03, 0.02, and 0.03 m for GLORYS12v1, ORAS5, CTO1/12, and CTO1/4, respectively.

Overall, for the seasonal amplitudes, the comparison in Figure 2 suggests that, in the deep ocean, high-resolution models perform better than medium-resolution models, and three of the four models (except ORAS5) obtain similar results as the altimeter data. In the shelf seas, ORAS5 obtains larger amplitudes than the altimeter data, which may be related to the larger seasonal amplitudes in the Scotian Slope and the subpolar gyre.

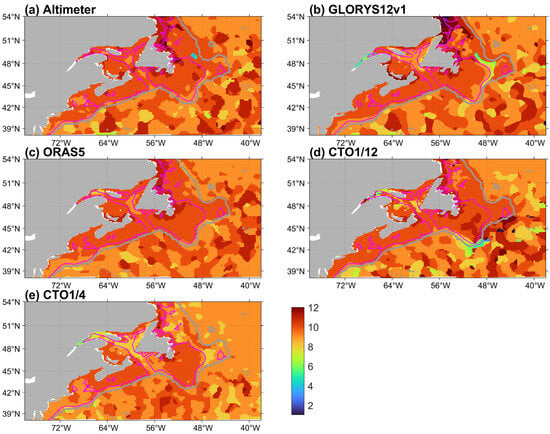

Figure 3 presents the phase (the month when the SSH reaches its maximum) of the mean seasonal cycles of SSH. The altimeter data and all four models obtain similar and nearly uniform phases in most parts of the shelf seas, with the maximum SSH occurring in October, and with delays to November–December along the coast of Labrador and northeastern Newfoundland. CTO1/4 obtains advanced phases of July–September in some outer parts of the Newfoundland Shelf, the central and northwestern Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the central Gulf of Maine. In the deep oceans, the altimeter data and the models all show less uniformly distributed phases, and, overall, the maximum SSH occurs in July–September, ahead of shelf seas. The root-mean-square differences in seasonal phase between altimeter data and each of the four models over the study area are one month for all models.

Figure 3.

Same as Figure 2 but for the phase (month, 1–12 corresponding to January–December) of the mean annual cycle of SSH during 1993–2023, defined as the month when the SSH reaches its maximum.

3.1.3. Linear Trends

To compare the SSH trends from the observations and models, which contribution factors are included in different data need first to be discussed. With the local IB effect removed, the long-term SSH trend of the altimeter data at a specific location includes the contributions from the sterodynamics (SD) of the ocean, non-VLM (vertical land motion) glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA), and changes in earth gravity, earth rotation, and viscoelastic solid earth deformation (GRD) (e.g., [21]). Averaged over the global ocean, SD is non-zero due to thermal expansion, and GRD is non-zero due to the barystatic effects, including the contributions from glaciers, the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, and the terrestrial water storage (e.g., [22]). These two components contribute to GMSL. At the time scales longer than the barotropic adjustment, GMSL has negligible influence on ocean circulation [23]. Since 1993, GLORYS12v1 and ORAS5 include the assimilation of altimeter data, and hence their SSH results include the contributions from both the GMSL change and the local effects of SD, non-VLM GIA, and GRD. The results of CTO1/12 and CTO1/4 include the same GMSL contribution as ORAS5, because both take SSH from ORAS5 as the input in the lateral open boundary condition. The local effects of thermal expansion, non-VLM GIA, and GRD are not included in the solutions of CTO1/12 and CTO1/4, but they are estimated to be small compared with the effects of their global-ocean-means (e.g., [24]). Besides the above factors, the long-term trends of tide gauge records also include the contribution from the local vertical land motions (VLMs).

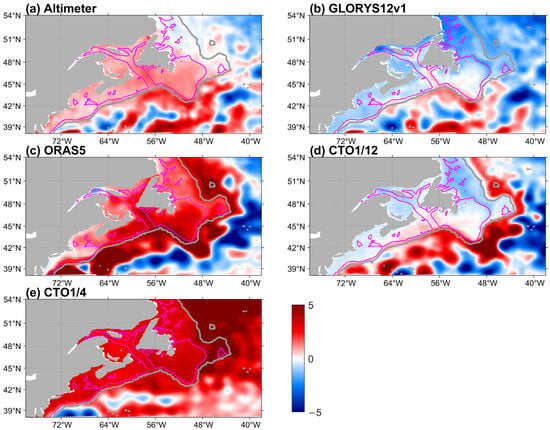

Figure 4 presents the spatial maps of the linear trends of SSH during 1993–2023 obtained by applying linear fitting to annual time series of SSH at each location. In all the maps, a value of 3.27 mm/year, the estimated GMSL trend during 1993–2023 according to [20], is subtracted. GLORYS12v1 shows overall good agreement with the altimeter data, particularly in deep waters beyond the shelf break where even the locations of the high and low trend values due mainly to the meso-scale eddy activities are in agreement. In shelf seas and in the deep ocean off the Labrador Shelf, GLORYS12v1 obtains trends by about 1 mm/year smaller than the altimeter data. CTO1/12 also obtains similar trend values as the altimeter data in the deep ocean, although the high and low trend values appear at different locations due to the lack of data assimilation. In the shelf seas of the Grand Banks, Scotian Shelf, and in Gulf of Maine, CTO1/12 obtains SSH trends closer to altimeter data than GLORYS12v1. The two medium-resolution models (ORAS5 and CTO1/4) obtain distinctly different SSH trend values and spatial distributions from the altimeter data. Even with data assimilation, ORAS5 obtains evidently larger positive trends in the Scotian Slope and across the Labrador Current, and also larger positive trends on the Grand Banks and Scotian Shelf, than the altimeter data. Without data assimilation, CTO1/4 obtains large and nearly uniform positive SSH trends in all the shelf seas shown in the map, and evidently larger trends over the Labrador Current and in the deep water off the Labrador Shelf. The root-mean-square differences in the linear trends between altimeter data and each of the four models over the study area are 1.28, 2.67, 2.58, and 3.51 mm/year for GLORYS12v1, ORAS5, CTO1/12, and CTO1/4, respectively.

Figure 4.

Similar format to Figure 1 except for the linear trends of SSH (mm/year) during 1993–2023, with the global mean trend value of 3.27 mm/year subtracted, from (a) altimeter, (b) GLORYS12v1, (c) ORAS5, (d) CTO1/12, and (e) CTO1/4. For the altimeter data, missing data due to sea-ice coverage are omitted when calculating the trend. Note that all these quantities shown do not include the contribution of IB.

Overall, for the SSH trends after removing the GMSL trend, the high-resolution models (GLORYS12v1 and CTO1/12) agree better with the altimeter data than the medium-resolution models (ORAS5 and CTO1/4). In the shelf seas, CTO1/12 without data assimilation obtains trend values closer to the altimeter estimates than GLORYS12v1. In both the deep ocean and shelf seas, data assimilation is effective in constraining the trends in GLORYS12v1, but not in ORAS5.

3.1.4. Detrended and De-Seasonalized Anomalies

For the monthly SSH of the altimeter data and from the four models during 1993–2023, the anomalies at each location are obtained by removing the linear trend and the time-mean seasonal cycle. Figure 5 presents the spatial distributions of the standard deviations of the detrended and de-seasonalized monthly SLAs. In the shelf seas, all models obtain small (less than 0.05 m) and nearly uniform standard deviations, consistent with the altimeter data. In deep waters, the differences among different datasets become evident. GLORYS12v1 quite accurately reproduces the standard deviations of the altimeter data, in both the spatial distribution and magnitudes. ORAS5 reasonably reproduces the spatial distribution of the large standard deviations associated with the GS/NAC variability and the meso-scale eddies, but obtains smaller magnitudes around the NW Corner and larger values over the Labrador Current. CTO1/12 obtains large values associated with GS/NAC that are generally consistent with GLORYS12v1, with an evident discrepancy in terms of the locations of these large values. CTO1/4 shows the poorest agreement with the altimeter, which can be attributed to the inaccuracy in the position and strength of GS/NAC, and weaker meso-scale eddies, NW Corner, deep convection, etc. The root-mean-square differences in the SLA standard deviations between altimeter data and each of the four models over the study area are 0.01, 0.06, 0.06, and 0.07 m for GLORYS12v1, ORAS5, CTO1/12, and CTO1/4, respectively.

Figure 5.

Standard deviations of the detrended and de-seasonalized monthly SLAs (m) during 1993–2023 from (a) altimeter, (b) GLORYS12v1, (c) ORAS5, (d) CTO1/12, and (e) CTO1/4. For the altimeter data, missing data due to sea-ice coverage are omitted when calculating the standard deviations.

Overall, in the deep NWA, including data assimilation and increasing model resolution both improve the consistency between the modeled and observed standard deviations of the monthly SLAs.

3.2. Time Series Analyses at Representative Locations

3.2.1. Mean Seasonal Cycle

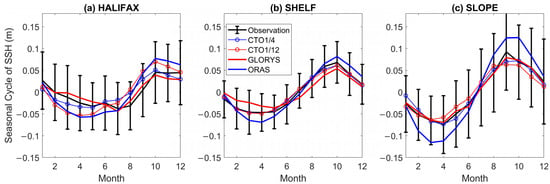

For time series analysis, we first examine the mean seasonal cycle during 1993–2023. Table 2 lists the amplitudes and phases of SSH at the 10 representative sites, and Figure 6 shows the time series at Halifax and sites 9 and 10, representing coast, shelf, and continental shelf break. At Halifax, the tide-gauge-observed seasonal amplitude of 0.04 m is well reproduced by GLORYS12v1 and CTO1/4, but is overestimated by ORAS5 and CTO1/12. The occurrence of the maximum SSH in October is captured by all four models. GLORYS12v1 reproduces the observed occurrence of the minimum SSH in July, while the other three models obtain the earlier occurrence in April/May. At site 9, the seasonal amplitude of 0.06 m from the altimeter data is reproduced by CTO1/12 and CTO1/4, and is overestimated by ORAS5 and underestimated by GLORYS12v1. The altimeter-observed occurrences of the maximum SSH in October and the minimum SSH in March–May are captured by all four models. At site 10, the altimeter-observed seasonal amplitude of 0.08 m and the occurrences of the maximum SSH in September–October and the minimum in March–April are reproduced by all the models, except that ORAS5 obtains a much larger seasonal amplitude of 0.12 m.

Figure 6.

The mean seasonal cycle of SSH during 1993–2023 at (a) Halifax and site (b) 9 on shelf and (c) 10 over the continental slope. The thicker black, red, and blue curves denote the observational data (tide gauge data at Halifax, altimeter data at sites 9 and 10), and model results of GLORYS12v1 and ORAS5, respectively. The thinner red and blue curves with open circles denote the results of CTO1/12 and CTO1/4. The length of the vertical bars denote the two standard deviations of the observed monthly values in each month.

According to Table 2, at tide gauges 2–4 and 6–8, the observed seasonal amplitudes of 0.03–0.07 m and the occurrences of the maximum SSH in September–December are well reproduced by all four models. At site 1 Quebec (Lauzon) in the St. Lawrence River, the seasonal cycle of SSH is related to that of the river runoff (e.g., [3]). The observed seasonal amplitude of 0.14 m is best reproduced as 0.09 m by CTPO1/12, but is significantly underestimated by the other three models. The observed occurrence of the maximum SSH in April (related to the peak of the spring freshet) is reproduced as occurring in May–June by three models, except being delayed to October by ORAS5. The runoff of the St. Lawrence River is specified according to the interannually varying monthly data derived from the Canadian hydrological observation in CTO1/12 and CTO1/4, while it is specified according the monthly climatology in the international database in GLORYS12v1 and ORAS5.

3.2.2. Linear Trends

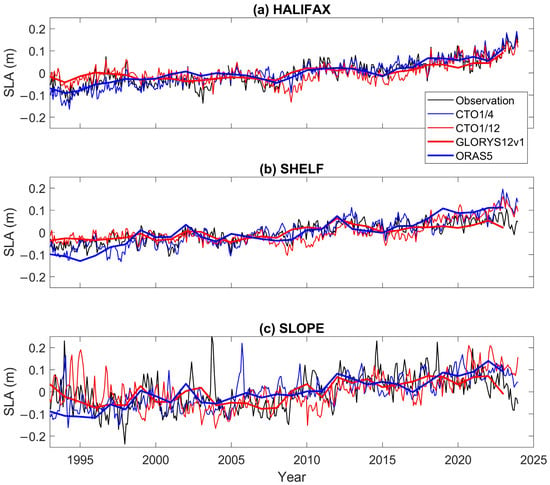

Figure 7 presents the time series of the de-seasonalized SLAs at Halifax and sites 9 and 10. To ease the comparison, what are plotted are the monthly data from observations (tide gauge at Halifax and altimeter at sites 9 and 10) and the results of CTO1/12 and CTO1/4, and the annual data from GLORYS12v1 and ORAS5. A linear SSH trend of 0.8 mm/year due to VLM, according to the recently updated Canadian crustal velocity model (NAD83v70VG; [25]), is removed from the tide gauge data of Halifax. Similar VLM-induced trends are removed from the other representative tide gauges. Table 3 lists the linear trends and the 90% confidence interval (CI) of the estimated trends, at all the sites 1–10. CI is computed according to [3], and estimated from the CI of individual components by assuming that they are independent. For example, the CI of the tide gauge trend () is estimated as follows: , where is the CI of linear fit to the annual tide gauge observations, and is the CI of the VLM model results.

Figure 7.

De-seasonalized SLAs at (a) Halifax and (b) site 9 on Scotian Shelf and (c) site 10 over continental slope during 1993–2023. The thinner black, red, and blue curves denote monthly observational (tide gauge and altimeter) data, and monthly model results of CTO1/12 and CTO1/4, respectively. The thicker red and blue curves denote the annual values from GLORYS12v1 and ORAS5, respectively. The Halifax tide gauge data are corrected for the linear SSH trend of 0.8 mm/year due to the vertical land motion. All the time series have their mean values during 1993–2023 removed. All times series do not include IB.

Table 3.

SSH trends ± 90% confidence interval (CI) (mm/year) during 1993–2023 for 10 sites from observations and four models. Values of linear trends due to VLM, based on NAD83v70VG, are removed from the observed tide gauge records at sites 1–8. For comparison with the maps of trend values presented in Figure 4, the values in this table need to be subtracted by 3.27 mm/year.

Note that the estimates of the GMSL trend of 3.27 mm/year during 1993–2023 are removed in the spatial maps of Figure 4, but not from Figure 7 and Table 3. At Quebec (Lauzon), the SSH trend from the tide gauge record has large uncertainties due to the strong variability of the St. Lawrence River runoff [3]. All models obtain larger trend values than observations, with the largest trend from CTO1/4. This suggests that all four models have errors in simulating the trends at this tide gauge located in the river.

At the other 9 sites, the observational data obtain trend values larger than the estimated GMSL trend of 3.27 mm/year, except at St. John’s (Newfoundland), whose trend value is lower. Overall, GLORYS12v1 and CTO1/12 obtain similar trend values that are smaller than the observations, while ORAS5 and CTO1/4 obtain trend values larger than the observations.

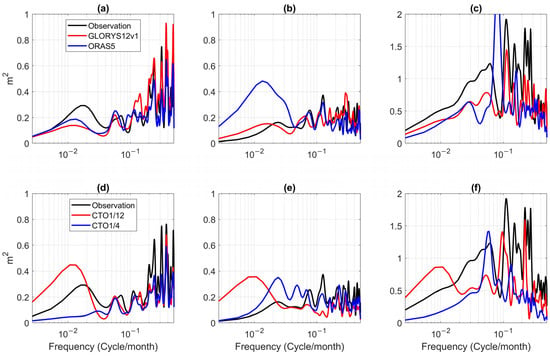

3.2.3. Spectral Analysis

Figure 8 presents the power spectra of the detrended and de-seasonalized monthly SLAs during 1993–2023 from observations and models at Halifax and sites 9 and 10. Overall, the spectra show different characteristics between higher and lower frequencies, or shorter and longer time scales. At time scales of less than about 20 months, the spectral levels from observations and models are generally in agreement. Larger differences among different models appear at time scales longer than 20 months. With reference to the observed spectral level, at Halifax, CTO1/2 obtains higher and the other three models obtain lower spectral levels, with CTO1/4 being the lowest. At site 9, GLORYS12v1 obtains similar values, while the other three models obtain higher spectral levels, with ORAS5 being the highest. At site 10, CTO1/12 obtains higher values, while the other three models obtain lower spectral levels.

Figure 8.

Power spectra of the detrended and de-seasonalized monthly SLAs during 1993–2023 at (a,d) Halifax, (b,e) site 9, and (c,f) site 10. Upper row: observational data (black, tide gauge data for Halifax and altimeter data for sites 9 and 10), GLORYS12 (red), and ORAS5 (blue). Lower row: observational data (black), CTO1/12 (red), and CTO1/4 (blue).

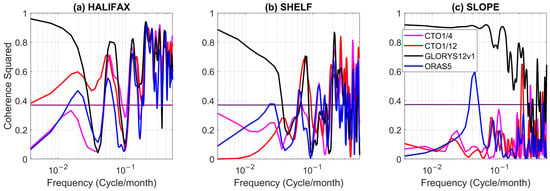

Figure 9 presents the coherency spectra of the monthly SLAs during 1993–2023, between observations and the four models at Halifax and sites 9 and 10. At all three sites, GLORYS12v1 achieves the highest coherency with the observations, which is significant at the 95% level across nearly all the time scales, with insignificant coherency near 10 and 20 months at Halifax and site 9. For the other three models, at Halifax, CTO1/12 achieves significant coherency across nearly all time scales, but at a lower level at longer than 20 months than GLORYS12v1; ORAS5 and CTO1/4 achieve significant coherency at shorter than 20 months. At site 9, the three models achieve significant coherency at less than 10 months. At site 10, the three models do not achieve significant coherency with observations across all the time scales.

Figure 9.

Coherency spectra of the detrended and de-seasonalized monthly SLAs during 1993–2023, between observations and four models at (a) Halifax, (b) site 9, and (c) site 10. The black, red, blue, and magenta curves are for GLORYS12v1, CTO1/12, ORAS5, and CTO1/4, respectively. The coherence values above the horizontal lines are statistically significant at the 95% level.

3.2.4. Model Skills for SSH Anomalies at Less and Longer than 20 Months

The analysis results in the above section suggest that the power spectra and coherencies show different characteristics between shorter and longer time scales, separated roughly at 20 months. This motivates us to assess the skills of the models for the two different time scales. A Butterworth filter at a cutoff of 20 months is applied to separate the variations at the two time scales. Two metrics are used for the skills assessment, namely, (1) correlation and (2) κ, which is defined as follows:

where and denote the variances of x (the observed SLA) and x-y (the observed minus-modeled SLAs). If the model fully reproduces observations, then , hence . If the model partially reproduces observations, then , hence 0. The model is regarded as having no skill . This can happen either when the models obtain very strong SLA variations, or the timing of the modeled SLA variations do not match that of the observed SLA.

The model skills at time scales less than 20 months are first discussed. According to Table 4, all four models show significant correlations (at the 0.05 significance level) with the observed SLAs at the eight representative tide gauges (Table 4). At Charlottetown (Prince Edward Island) in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and St. John’s (Newfoundland), the four models obtain relatively lower correlation values (0.42–0.54). At Quebec (Lauzon), GLORYS12v1 and ORAS5 obtain smaller values of 0.56–0.57 than the values of 0.74–0.79 obtained by CTO1/4 and CTO1/12. At the other five tide gauges, all models obtain high correlations of 0.61–0.89. At site 9 on the Scotian Shelf, all models obtain relatively lower correlations of 0.39–0.56. At site 10 over the shelf break, only GLORYS12v1 obtains a significant and high (0.69) correlation.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients between observations and each of the four models for the detrended and de-seasonalized monthly SLAs at time scales shorter than 20 months, at 10 representative sites during 1993–2023. Only significant correlations (p-value < 0.05) are listed.

According to Table 5, at the eight tide gauges, all four model obtain κ values less than unity, i.e., possessing skills in reproducing the observed SLAs at less than 20 months. Relatively lower skills (κ values of 0.13–0.33) are shown at Charlottetown and St. John’s by all four models, and at Quebec by GLORYS12v1 and ORAS5. At site 9, CTO1/12 and CTO1/4 show low skills, while GLORYS12v1 and ORAS5 show no skills. At site 10, only GLORYS12v1 shows skills. Overall, at time scales less than 20 months, the two metrics obtain consistent assessment results, i.e., all four models possess skills in reproducing the observed tide gauge records, the skills become lower on the Scotian Shelf, and only GLORYS12v1 possesses skills over the shelf break.

Table 5.

The skill metric κ of each of the four models against observations for the detrended and de-seasonalized monthly SLAs at time scales shorter than 20 months, at 10 representative sites during 1993–2023.

Table 6 and Table 7 list the correlations and κ values at time scales longer than 20 months. According to both metrics, GLORYS12v1 possesses skills at 9 of the 10 representative sites, except at St. John’s; CTO1/12 possesses skills at Quebec; and ORAS5 and CTO1/4 possess skills only at Boston.

Table 6.

Same as Table 4, except for time scales longer than 20 months.

Table 7.

Same as Table 5, except for time scales longer than 20 months.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In Section 3, SSH variations from four models were assessed with tide gauge and altimeter observations for four different aspects: multi-decadal mean, linear trend, seasonal cycle, and the de-trended and de-seasonalized anomalies (which are further separated for time scales shorter and longer than 20 months). The model skills, or the influences of model resolution and data assimilation, differ for these four different aspects, and the underlying causes related to ocean dynamics need to be discussed.

For the time-mean SSH (Section 3.1.1, Figure 1), the evident differences between CTO1/12 and CTO1/4 suggest that, without data assimilation, higher resolution achieves a more realistic simulation of the strength of the Gulf Stream (GS)/North Atlantic Current (NAC), while the biases in the Labrador Sea are hard to constrain. Without data assimilation, the deep convection (as indicated by the modeled mixed layer depth) is stronger in CTO1/12 and weaker in CTO1/4, relative to GLORYS12v1. Data assimilation effectively constrains the biases in the Labrador Sea, and enables realistic GS/NAC strength even with medium resolution (ORAS5).

For the mean seasonal cycle (Section 3.1.2 and Section 3.2.1), all four models well reproduced the phases derived from observations. In the deep NWA, the occurrence of the seasonal maximum SSH in summer (July–September) may be attributed to the dominance of upper ocean warming (the thermosteric height). At Quebec in the St. Lawrence River and at Charlottetown in the semi-enclosed Gulf of St. Lawrence, the models generally reproduce the observed seasonal phases in April and December, which are related to the seasonal peaks of the river runoff and wind speed, respectively [3]. Along the coast open to the shelf, the general occurrence of the maximum SSH in autumn–winter (September–December) can be attributed to the stronger wind-induced baroclinic transport in winter than in summer [26]. At Halifax, the occurrence of the seasonal maximum in October is related to the combination of thermosteric height peaking in summer and halosteric height peaking in winter. The multiple regression analysis of Thompson (1986) suggested that the occurrence of the non-wind-driven seasonal maximum occurring in December was related to the peak strength of the Nova Scotian Current. While [2] interpreted this as being due to the propagation of the freshwater discharge from the St. Lawrence River, we propose that this is possibly due to the downwelling of lower salinity upper-layer water by the southwestward along-shore wind in winter. Such a wind-driven baroclinic process is consistent with the conclusion of [26], and is similar to the process occurring in winter over the whole shelf sea off Canada’s west coast [4].

Regarding the seasonal magnitude, all models obtain similar general characteristics of spatial distributions, e.g., differences between the deep ocean and shelf seas, which are consistent with the altimeter data. The overestimation by ORAS5 in the Scotian Slope can be related to the large ocean temperature biases in the Gulf Stream and its extension regions, which are possibly associated with the misrepresentation of front positions [10]. This suggests that data assimilation in ORAS5 introduces the biases in the seasonal cycle near the Gulf Stream, which further lead to the overestimation on the Scotian Shelf. Without obvious biases in the deep ocean, the other three models obtain similar seasonal amplitudes as observations at seven of the eight tide gauges, except at Quebec in the St. Lawrence River. The models’ low skills at this station may be related to introducing the river runoff as rainfall at sea surface over a number of grids near the river mouth. At Bar Harbor and Boston in the Gulf of Maine, the observed amplitudes of 4–5 cm in our analysis are larger than 1.0–1.8 cm of the total observed amplitudes, as reported by [2] (his Table 1), with reasons unknown. Given that the two stations are located in the semi-enclosed Gulf of Maine, their seasonal cycles are probably mainly caused by the wind-driven barotropic dynamics, similar to that which is at Charlottetown in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Overall, the agreement between the observed and modeled seasonal amplitudes (and phases) at the 10 representative sites (except ORAS5 at sites 9–10) suggests that, along the coast and on the shelf, the seasonal cycle of SSH can be attributed mainly to the wind-driven barotropic or baroclinic dynamics with a linear nature. This is also consistent with the smoothing distribution of the amplitude (and phase).

For the linear trends during 1993–2023 (Section 3.1.3 and Section 3.2.2), except at Quebec in the St. Lawrence River, the other nine representative sites show significantly positive trends based on tide gauge observations (with the trends of the local vertical land motions removed) and altimeter data. Among them, eight sites show trend values (3.96–5.11 mm/year) significantly larger than the GMSL rise of 3.27 mm/year. The observed sea level trend at St. John’s is 2.96 ± 1.43 mm/year, not significantly different from the GMSL trend. After removing the GMSL rate, the two high-resolution models (GLORYS12v1 and CTO1/12) obtain trends closer to observations. For the two medium-resolution models, the overestimation by CTO1/4 over and to the east of the Labrador Current is attributed to the weak deep convection, and this bias leads to the overestimation of trends in the shelf seas. Previous studies (e.g., [27]) have documented the potential linkage between variations in coastal sea levels along the east coast of North America and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, which is related to the strength of deep convection in the Labrador Sea. The overestimation by ORAS5 over the Labrador Current and Scotian Slope, and on the Newfoundland Shelf and Scotian Shelf, suggests that data assimilation in this model does not effectively constrain the ocean dynamic process that influences the long-term SSH trends.

Finally, for the detrended and de-seasonalized monthly SLAs (Section 3.1.4, Section 3.2.3 and Section 3.2.4), three models except CTO1/4 obtain realistic variability in the deep water. However, over the shelf break (site 10), except GLROYS12v1, the other three models possess no skills at time scales both shorter and longer than 20 months. Along the coast, all models possess skills at time scales shorter than 20 months, suggesting the variations at these time scales are caused mainly by wind-driven linear dynamics. Except GLORYS12v1, the other three models generally possess no skills at time scales long than 20 months along the coast, and at time scales both shorter and longer than 20 months on the shelf and over the shelf break (sites 9–10). At interannual and longer time scales, sea level variations along the coast and on the shelf of NWA are linked to variations in the deep ocean. For example, Frederikse et al. [28] demonstrated a strong positive correlation between decadal variations in coastal sea levels from north of Cape Hatteras to Halifax and steric height in the subpolar gyre, including the recent upward trend since 1990 (Figure 8 in [28]). Their findings are also relevant to the long-term sea level trends.

In summary, the analysis results of this study partially answered the question raised from reviewing previous work (in the last paragraph of Section 1), demonstrating the influence of model resolution and data assimilation on the simulation of SSH beyond the synoptic time scales. Among the four models evaluated, the high-resolution GLORYS12v1 with advanced data assimilation possesses skills in all four aspects, in the deep ocean and shelf seas and along the coast. This extends and advances the analysis results of [5], who focused on interannual sea level variations along the coast, and showed low skills of the four data assimilative models with coarse or medium spatial resolutions. The three other models show different discrepancies relative to GLORYS12v1. They possess low or no skills (as indicated by the low coherency, correlations, and κ values) for the timing (despite reasonable standard deviations) of sea level variations at time scales longer than 20 months along the coast, and at all time scales on the shelf, over the shelf break, and in the deep ocean. These variations can be reasonably attributed to the nonlinear ocean dynamics, i.e., the variability of the Gulf Stream/North Atlantic Current and their interaction with the Labrador Current, the strong eddy activities, etc. In this sense, the present study supports the analysis results and hypothesis of [3]. The medium-resolution ORAS5, using a different data assimilation approach than GLORYS12v1, shows biases in the seasonal amplitude in the Scotian Slope and trends over the Labrador Current, in the Scotian Slope, and on the shelf. Without data assimilation, the medium-resolution model CTO1/4 shows lower skills than ORAS5, except for the seasonal amplitude in the Scotian Slope. The lower skills of ORAS5 relative to GLOYS12v1 can be partly attributed to the lower model resolution and partly to the difference in data assimilation methods. It remains to be explored whether the skills of ORAS5 can be improved in its next version, which assimilates the altimeter data globally and with more weight, as well as assimilating ocean observations over continental shelves [29]. Feng et al. [30] have identified improved skills of this new version near many tide gauges. On the other hand, even if data assimilation can improve the skills of ocean reanalysis products, the strong nonlinear dynamics in the region also poses challenges in predicting future changes in sea levels, hydrography, and circulation. We wonder whether the results of ensemble simulations using the high-resolution earth system models (e.g., [31]) can provide reliable climate projections for the NWA region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and L.Z.; Methodology, Y.L., L.Z. and X.H.; software, L.Z., X.H. and F.D.; writing, Y.L., L.Z., X.H. and F.D.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Competitive Science Research Fund and Marine Conservation Target program of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), and the Transforming Climate Action (TCA) program led by Dalhousie University.

Data Availability Statement

The gridded altimeter SLA is obtained from the website of the Copernicus Climate Change Service (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/satellite-sea-level-global?tab=documentation accessed on 6 December 2024). The CNES-CLS-2022 MDT is obtained from the Copernicus Marine Services (https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_MDT_008_063/description accessed on 11 December 2024). ORAS5 is obtained from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-oras5?tab=overview accessed on 12 January 2025. GLORYS12v1 is obtained from https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030/description accessed on 8 September 2025. Tide gauge data are obtained from https://psmsl.org/ accessed on 20 December 2024.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah MacDermid, who contributed to the initial setting up and testing of the two CTO ocean and sea-ice models without-data assimilation; and many colleagues in DFO, Environment and Climate Change Canada, universities, and Mercator Ocean International who contributed to the development of the previous versions of the models leading to CTO. David Brickman and Hui Shen jointly applied and managed two DFO-funded projects with Youyu Lu. Jinyu Sheng supported Youyu Lu for the TCA funding support, and collaborated extensively on ocean modeling and analysis. Blair Greenan suggested numerous references on sea level research. Zeliang Wang and Stephanne Taylor served as internal reviewers. Three anonymous reviewers provided constructive comments that guided the revision of the originally submitted manuscript. The late Keith Thompson is greatly appreciated for his inspiration and guidance on research in ocean modeling and data analysis by all the co-authors, and for his mentorship, generous support over 20 years, and influences on the styles of research and presentation and interests in sea level studies by Youyu Lu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Greatbatch, R.; Lu, Y.; Young, B. Application of a Barotropic Model to North Atlantic Synoptic Sea Level Variability. J. Mar. Res. 1996, 54, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.R. North Atlantic Sea-Level and Circulation. Geophys. J. Int. 1986, 87, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Lu, Y.; Greenan, B. Evaluation of the Budget of Local Sea Level Trends Along the Coast of Canada and Northern USA During 1958–2015. J. Geophys. Res. 2025, 130, e2024JC021000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhai, L.; Hu, X.; Horwitz, R.; Paquin, J.-P.; Hannah, C.; Crawford, W. Sea Level Variations in Shelf Waters off the Coast of British Columbia: From Subsynoptic to Interannual Time Scales. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2025, 55, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piecuch, C.G.; Dangendorf, S.; Ponte, R.M.; Marcos, M. Annual Sea Level Changes on the North American Northeast Coast: Influence of Local Winds and Barotropic Motions. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 4801–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérou, A.; Meyssignac, B.; Prandi, P.; Ablain, M.; Ribes, A.; Bignalet-Cazalet, F. Current Observed Global Mean Sea Level Rise and Acceleration Estimated from Satellite Altimetry and the Associated Uncertainty. Ocean Sci. 2022, 19, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandi, P.; Meyssignac, B.; Ablain, M.; Spada, G.; Ribes, A.; Benveniste, J. Local Sea Level Trends, Accelerations and Uncertainties over 1993–2019. Sci Data 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, F.; Ballarotta, M. Product Quality Assessment Report (PQAR). Available online: http://dast.data.compute.cci2.ecmwf.int/documents/satellite-sea-level/vDT2024/C3S2-D312b-WP2-FDDP-SL-v3.0-202411-PQAR-of-vDT2024-v1.1_Final.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Griffies, S.M.; Yin, J.; Durack, P.J.; Goddard, P.; Bates, S.C.; Behrens, E.; Bentsen, M.; Bi, D.; Biastoch, A.; Böning, C.W.; et al. An Assessment of Global and Regional Sea Level for Years 1993–2007 in a Suite of Interannual CORE-II Simulations. Ocean Model. 2014, 78, 35–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Tietsche, S.; Mogensen, K.; Mayer, M. The ECMWF Operational Ensemble Reanalysis–Analysis System for Ocean and Sea Ice: A Description of the System and Assessment. Ocean Sci. 2019, 15, 779–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lellouche, J.-M.; Greiner, E.; Bourdallé-Badie, R.; Garric, G.; Melet, A.; Drévillon, M.; Bricaud, C.; Hamon, M.; Le Galloudec, O.; Regnier, C.; et al. The Copernicus Global 1/12° Oceanic and Sea Ice GLORYS12 Reanalysis. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 698876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, A.T.; Deltel, C.; Machu, E.; Ricci, S.; Daget, N. A Multivariate Balance Operator for Variational Ocean Data Assimilation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 131, 3605–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, K.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Weaver, B. The NEMOVAR Ocean Data Assimilation System as Implemented in the ECMWF Ocean Analysis for System 4. Available online: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/elibrary/75708-nemovar-ocean-data-assimilation-system-implemented-ecmwf-ocean-analysis-system-4 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Brasseur, P.; Verron, J. The SEEK Filter Method for Data Assimilation in Oceanography: A Synthesis. Ocean Dyn. 2006, 56, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, C.; Vancoppenolle, M.; Madec, G.; Fichefet, T.; Flavoni, S.; Barthélemy, A.; Benshila, R.; Chanut, J.; Levy, C.; Masson, S.; et al. The Louvain-La-Neuve Sea Ice Model LIM3.6: Global and Regional Capabilities. Geosci. Model Dev. 2015, 8, 2991–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancoppenolle, M.; Fichefet, T.; Goosse, H. Simulating the Mass Balance and Salinity of Arctic and Antarctic Sea Ice. 2. Importance of Sea Ice Salinity Variations. Ocean Model. 2009, 27, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermid, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhai, L.; Hu, X.; Brickman, D. Tuning Ice Model Parameters to Improve Arctic Sea-Ice Simulation Using the ERA5 Atmospheric Reanalysis Forcing. J. Oper. Oceanogr. 2025, 18, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquin, J.-P.; Roy, F.; Smith, G.C.; MacDermid, S.; Lei, J.; Dupont, F.; Lu, Y.; Taylor, S.; St-Onge-Drouin, S.; Blanken, H.; et al. A New High-Resolution Coastal Ice-Ocean Prediction System for the East Coast of Canada. Ocean Dyn. 2024, 74, 799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrère, L.; Lyard, F. Modeling the Barotropic Response of the Global Ocean to Atmospheric Wind and Pressure Forcing—Comparisons with Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckley, B.; Yang, X.; Zelensky, N.P.; Holmes, S.A.; Lemoine, F.G.; Ray, R.D.; Mitchum, G.T.; Desai, S.; Brown, S.T. Global Mean Sea Level Trend from Integrated Multi-Mission Ocean Altimeters TOPEX/Poseidon, Jason-1, OSTM/Jason-2, Jason-3, and Sentinel-6 Version 5.2. Available online: https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/dataset/MERGED_TP_J1_OSTM_OST_GMSL_ASCII_V52 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Harvey, T.C.; Hamlington, B.D.; Frederikse, T.; Nerem, R.S.; Piecuch, C.G.; Hammond, W.C.; Blewitt, G.; Thompson, P.R.; Bekaert, D.P.S.; Landerer, F.W.; et al. Ocean Mass, Sterodynamic Effects, and Vertical Land Motion Largely Explain US Coast Relative Sea Level Rise. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.M.; Griffies, S.M.; Hughes, C.W.; Lowe, J.A.; Church, J.A.; Fukimori, I.; Gomez, N.; Kopp, R.E.; Landerer, F.; Cozannet, G.L.; et al. Concepts and Terminology for Sea Level: Mean, Variability and Change, Both Local and Global. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 1251–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greatbatch, R.J. A Note on the Representation of Steric Sea Level in Models That Conserve Volume Rather than Mass. J. Geophys. Res. 1994, 99, 12767–12771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnauskas, K.B.; Nerem, R.S.; Fasullo, J.T.; Bellas-Manley, A.; Thompson, P.R.; Coats, S.; Chambers, D.P.; Hamlington, B.D. Diagnosing Regional Sea Level Change Over the Altimeter Era. J. Geophys. Res. 2025, 130, e2024JC022100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, C.M.I.; Craymer, M.; Ferland, R.; James, T.S.; Lapelle, E.; Piraszewski, M.; Zhao, Y. NAD83v70VG: A New National Crustal Velocity Model for Canada; Natural Resources Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loder, J.W.; Hannah, C.G.; Petrie, B.D.; Gonzalez, E.A. Hydrographic and Transport Variability on the Halifax Section. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108, 8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C.M.; Hu, A.; Hughes, C.W.; McCarthy, G.D.; Piecuch, C.G.; Ponte, R.M.; Thomas, M.D. The Relationship Between U.S. East Coast Sea Level and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation: A Review. J. Geophys. Res. 2019, 124, 6435–6458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederikse, T.; Simon, K.; Katsman, C.A.; Riva, R. The Sea-Level Budget along the Northwest Atlantic Coast: GIA, Mass Changes, and Large-Scale Ocean Dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. 2017, 122, 5486–5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Balmaseda, M.A.; de Boisseson, E.; Tietsche, S.; Mayer, M.; de Rosnay, P. The ORAP6 Ocean and Sea-Ice Reanalysis: Description and Evaluation. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Online, 19–30 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Widlansky, M.J.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Zuo, H.; Spillman, C.M.; Smith, G.; Long, X.; Thompson, P.; Kumar, A.; Dusek, G.; et al. Improved Capabilities of Global Ocean Reanalyses for Analysing Sea Level Variability near the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Coastal U.S. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1338626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Fu, D.; Liu, X.; Castruccio, F.S.; Prein, A.F.; Danabasoglu, G.; Wang, X.; Bacmeister, J.; Zhang, Q.; Rosenbloom, N.; et al. Future Extreme Precipitation Amplified by Intensified Mesoscale Moisture Convergence. Nat. Geosci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).