Deep Learning-Based Prediction of Ship Roll Motion with Monte Carlo Dropout

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Related Works

1.3. Research Objectives

2. Data and Experimental Setup

2.1. Operational Data Collection

- ship motion data measured by MEMS-based electronic inclinometers,

- GPS-based navigation trajectory data.

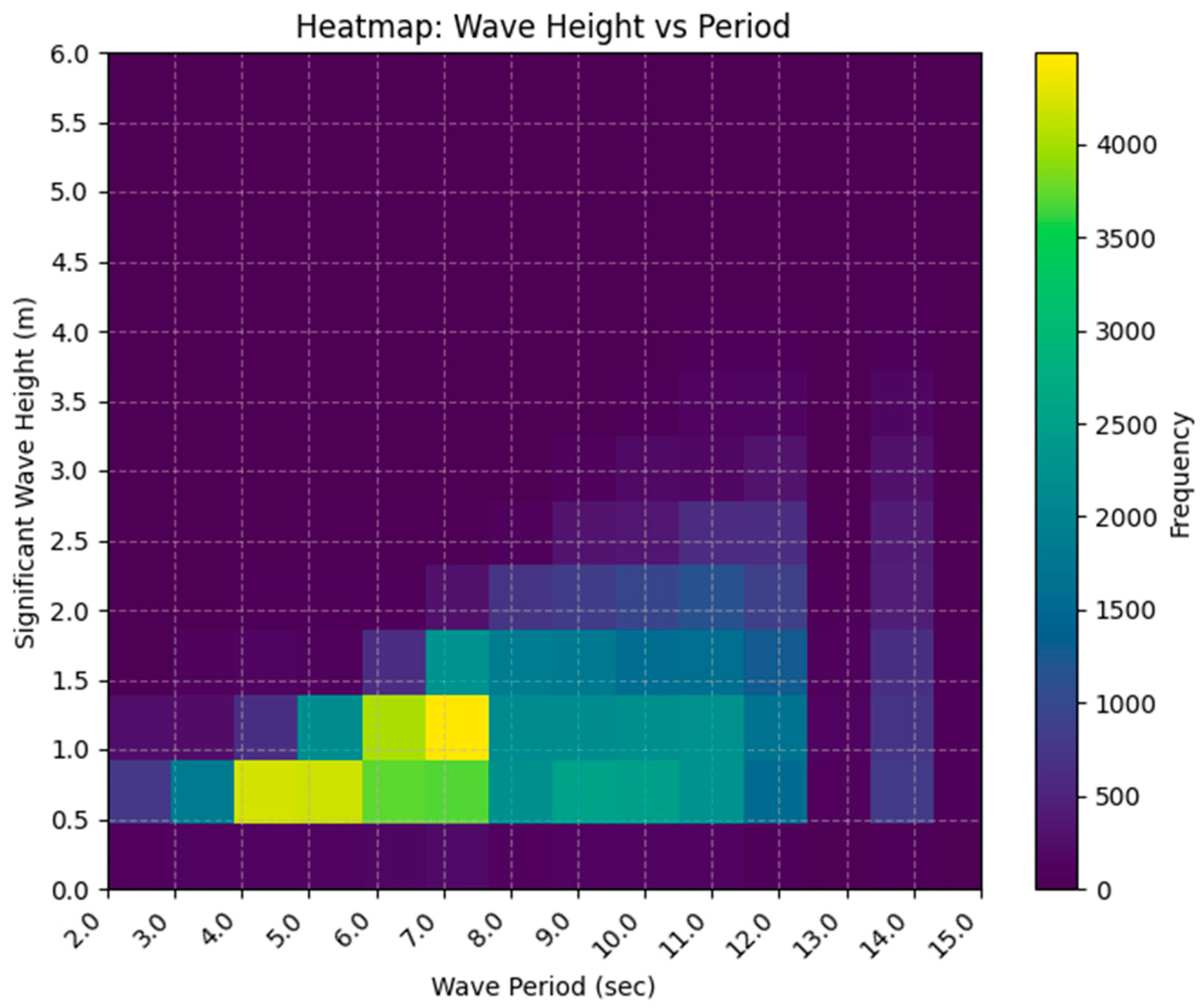

2.2. Environmental and Wave Data

2.2.1. Marine Meteorological Data

2.2.2. Wave Statistics

- The mean and median of Hs were 1.06 m and 0.9 m, respectively, indicating predominance of low waves.

- The most frequent range was 0.5–1.0 m (36%), followed by 1.0–1.5 m (21%) and 0.0–0.5 m (24%).

- Waves exceeding 2.0 m accounted for only ~9%, and extreme waves above 5.0 m were rare (0.04%), with the maximum recorded Hs = 6.4 m.

- The mean and median Tz were 5.2 s and 4.9 s, with the dominant range of 3–5 s (43%), followed by 5–7 s (32%) and 7–9 s (14%).

- Long-period waves exceeding 9 s were scarce (≈3%), with a maximum Tz = 28.6 s.

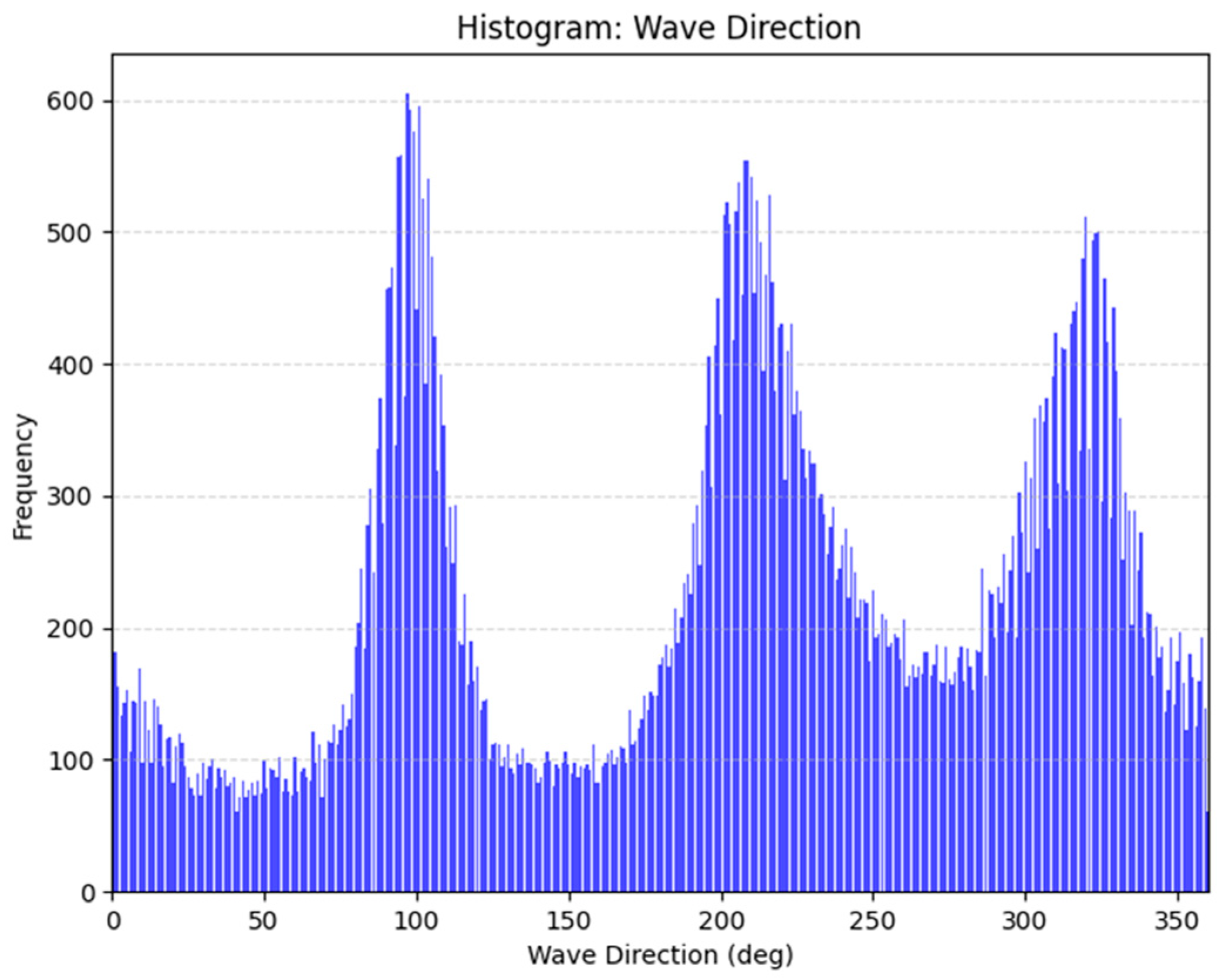

2.2.3. Wave Direction Distribution

2.2.4. Ship Heading Analysis Based on GPS

- : absolute wave direction (° from true north),

- : ship heading angle (° from true north),

- : relative wave heading (° from bow; port = −, starboard = +).

- Heading 1: 189° (southwest),

- Heading 2: 25° (north–northeast).

- Beam Sea (±90°): largest roll amplitude,

- Quartering Sea (±45–135°): coupled roll–yaw motion → broaching risk,

- Head Sea (0°): dominant pitch/heave response,

- Following Sea (180°): degraded course stability.

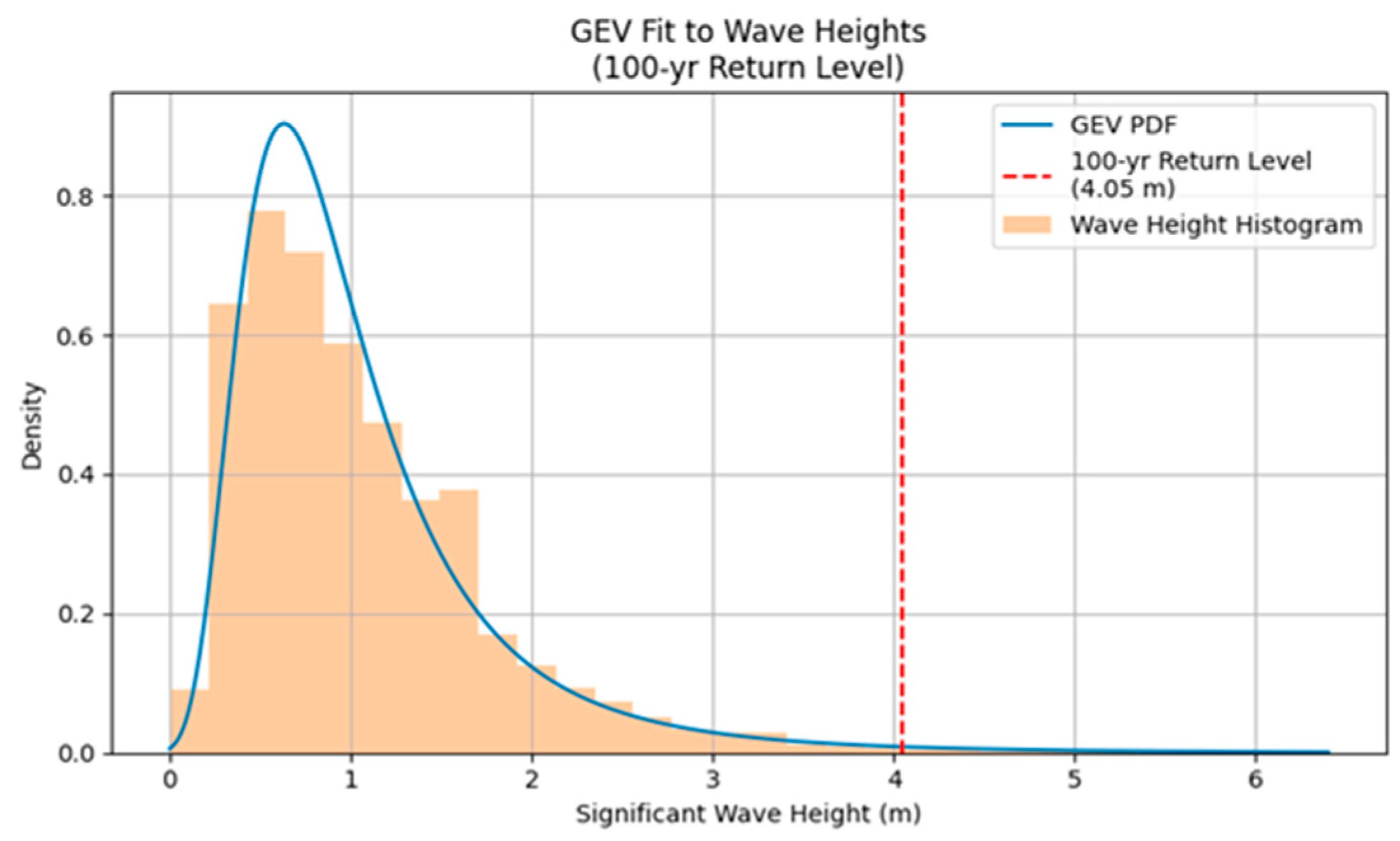

2.2.5. Extreme Wave Generation Using GEV Distribution

- : random variable (significant wave height),

- : location parameter (central tendency),

- : scale parameter (distribution width),

- : shape parameter (tail heaviness).

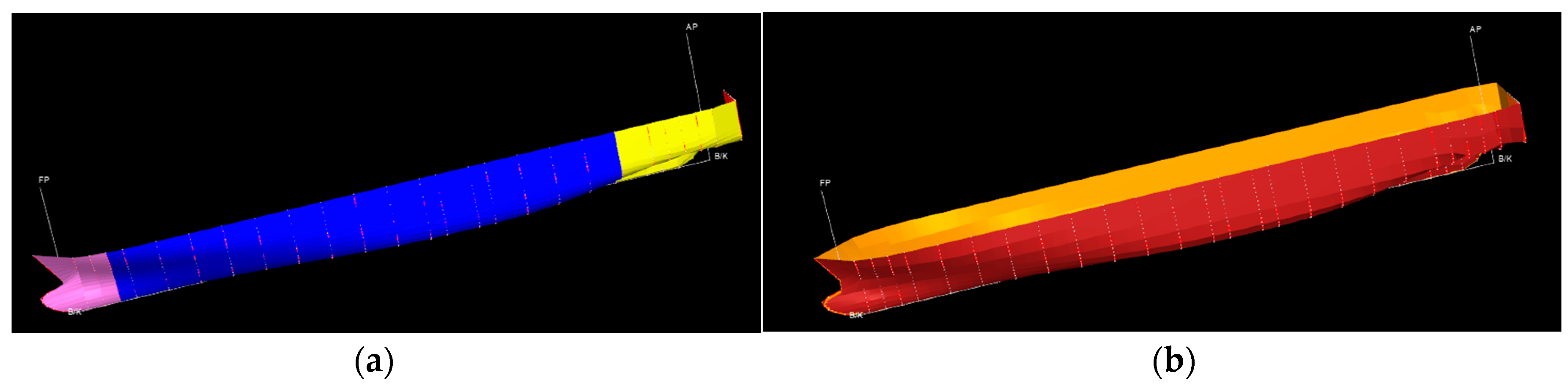

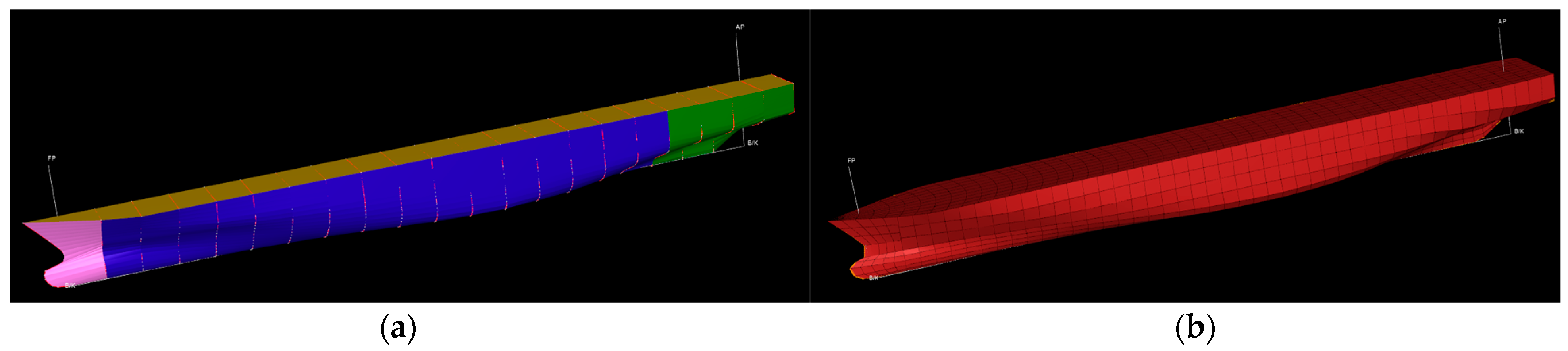

2.3. DNV Sesam Package and HydroD

2.4. Numerical Simulation (HydroD-Wasim)

Simulation Configuration

- Ship speed: 21 kn (service), 10 kn (reduced), and 0 kn (stationary).

- Hull condition: Intact, and three flooding scenarios (bow, midship, stern).

- Wave environment: Significant wave heights 2.0, 4.0, 4.9, 6.3 m; mean periods 7.5, 8.5, 9.5 s; eight directions at 45° intervals (0–315°).

3. Methodology

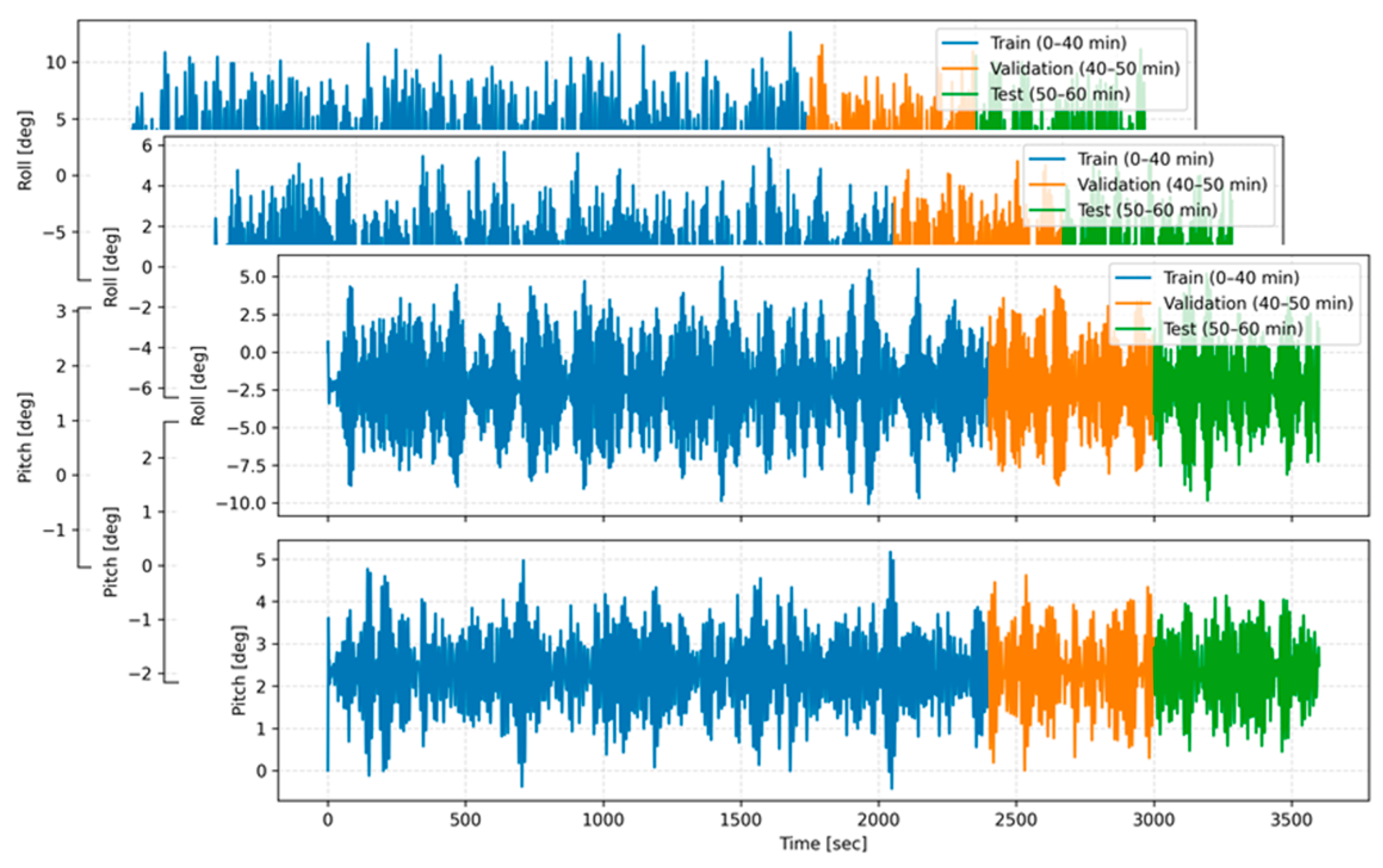

3.1. Data Preprocessing

- Training data: 0–2400 s (first 40 min);

- Validation data: 2400–3000 s (next 10 min);

- Test data: 3000–3600 s (last 10 min).

3.2. Deep-Learning Models

3.2.1. LSTM Model

- Forget gate: Decides which past information to discard.

- Input gate: Determines what new information to store in the cell.

- Cell state update: Integrates retained and new information.

- Output gate: Controls which part of the cell state is propagated.

3.2.2. Transformer Model

- Self-Attention: Captures contextual relationships among all positions in the input sequence.

- Parallel computation: Processes all input tokens simultaneously.

- Long-range dependency handling: Models global dependencies without loss of temporal coherence.

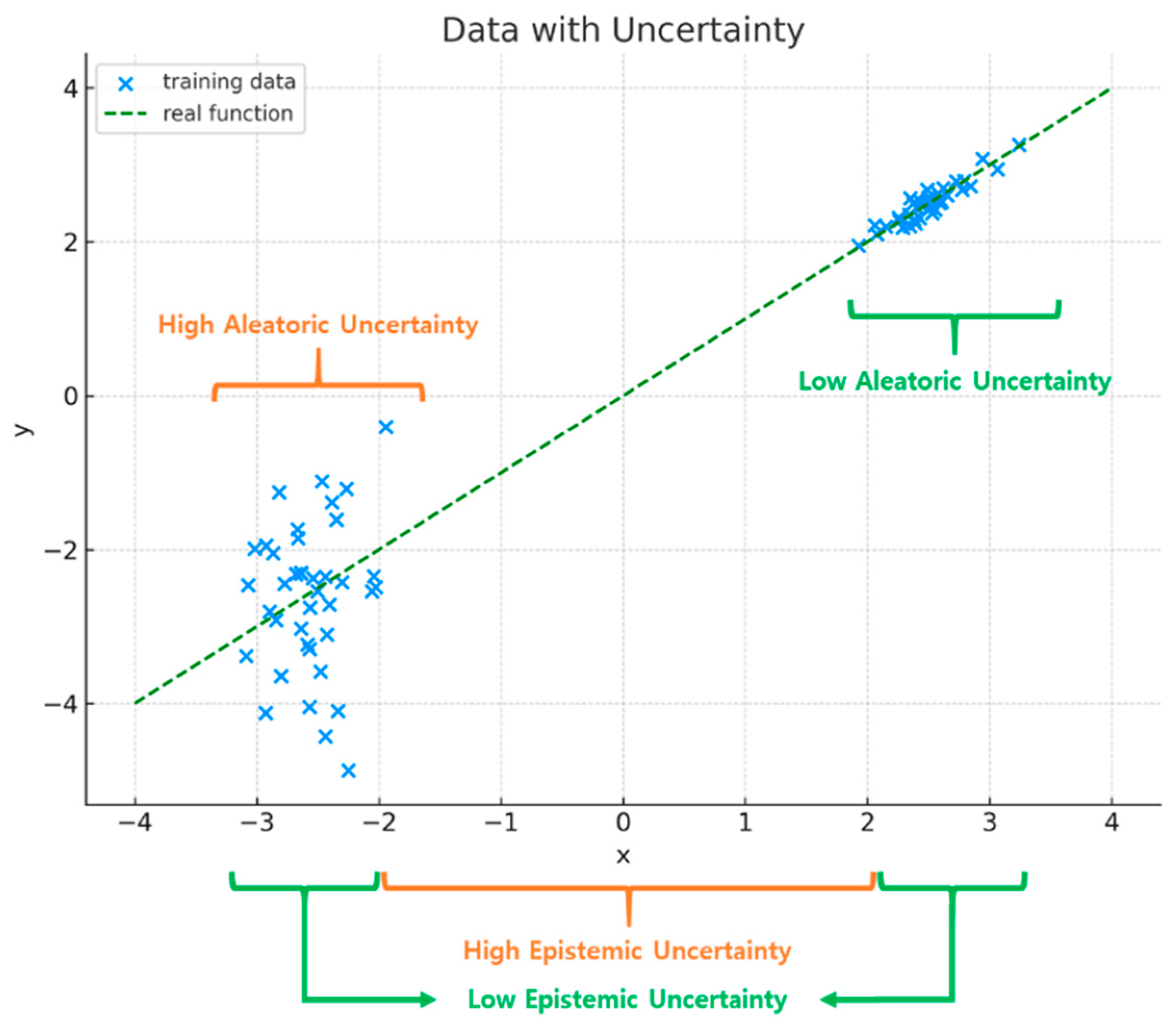

3.3. Uncertainty Quantification

- Aleatoric Uncertainty (Data Uncertainty):

- 2.

- Epistemic Uncertainty (Model Uncertainty):

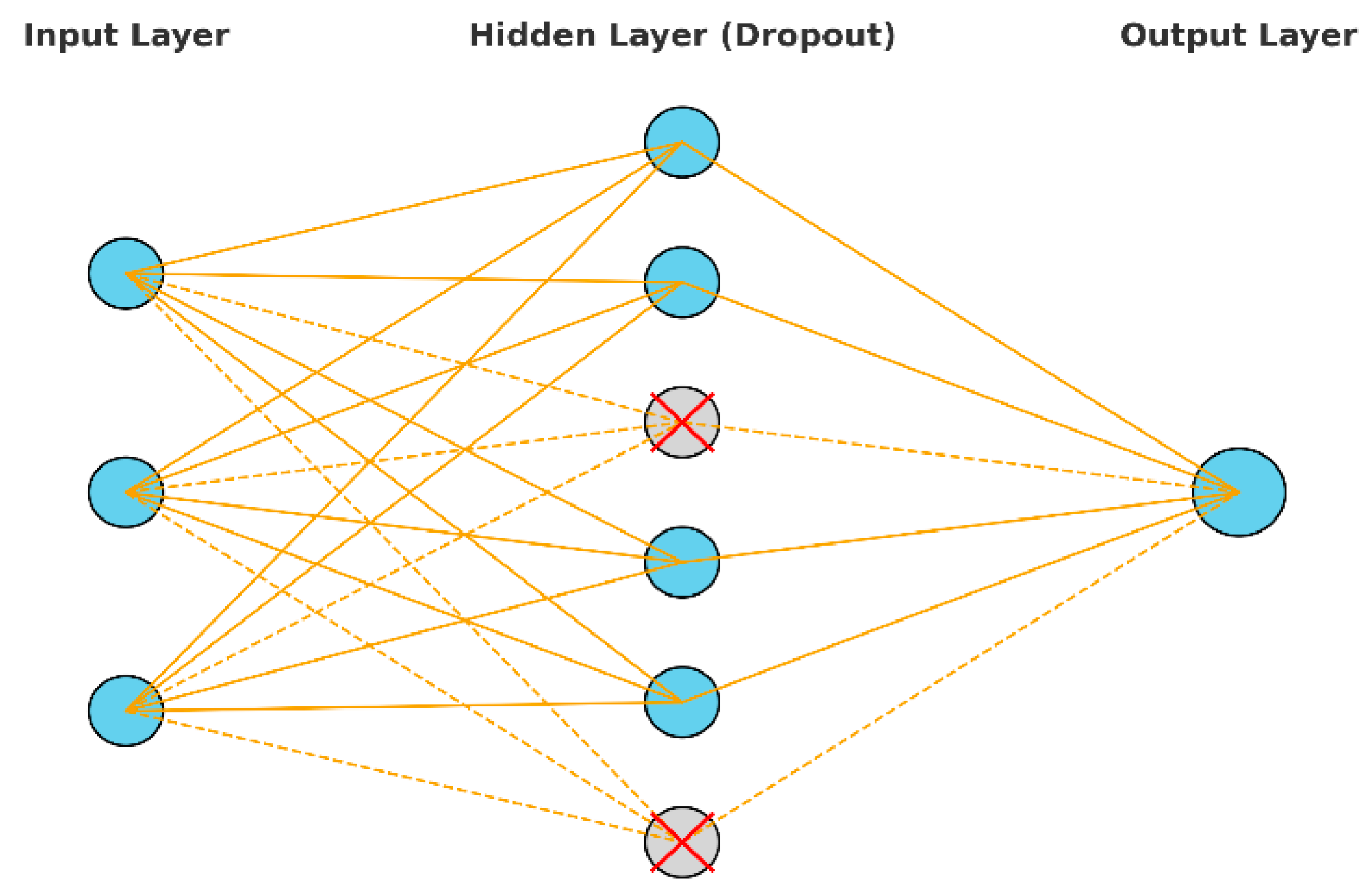

3.3.1. Monte Carlo Dropout

- Implementation simplicity: Any Dropout-enabled network can estimate uncertainty by enabling Dropout at inference.

- No additional training: Requires only repeated stochastic forward passes.

3.3.2. Loss Function

- (1)

- Mean Squared Error (MSE)

- (2)

- Prediction Interval Coverage Probability (PICP)

- (3)

- Prediction Interval Normalized Average Width (PINAW)

4. Results and Discussion

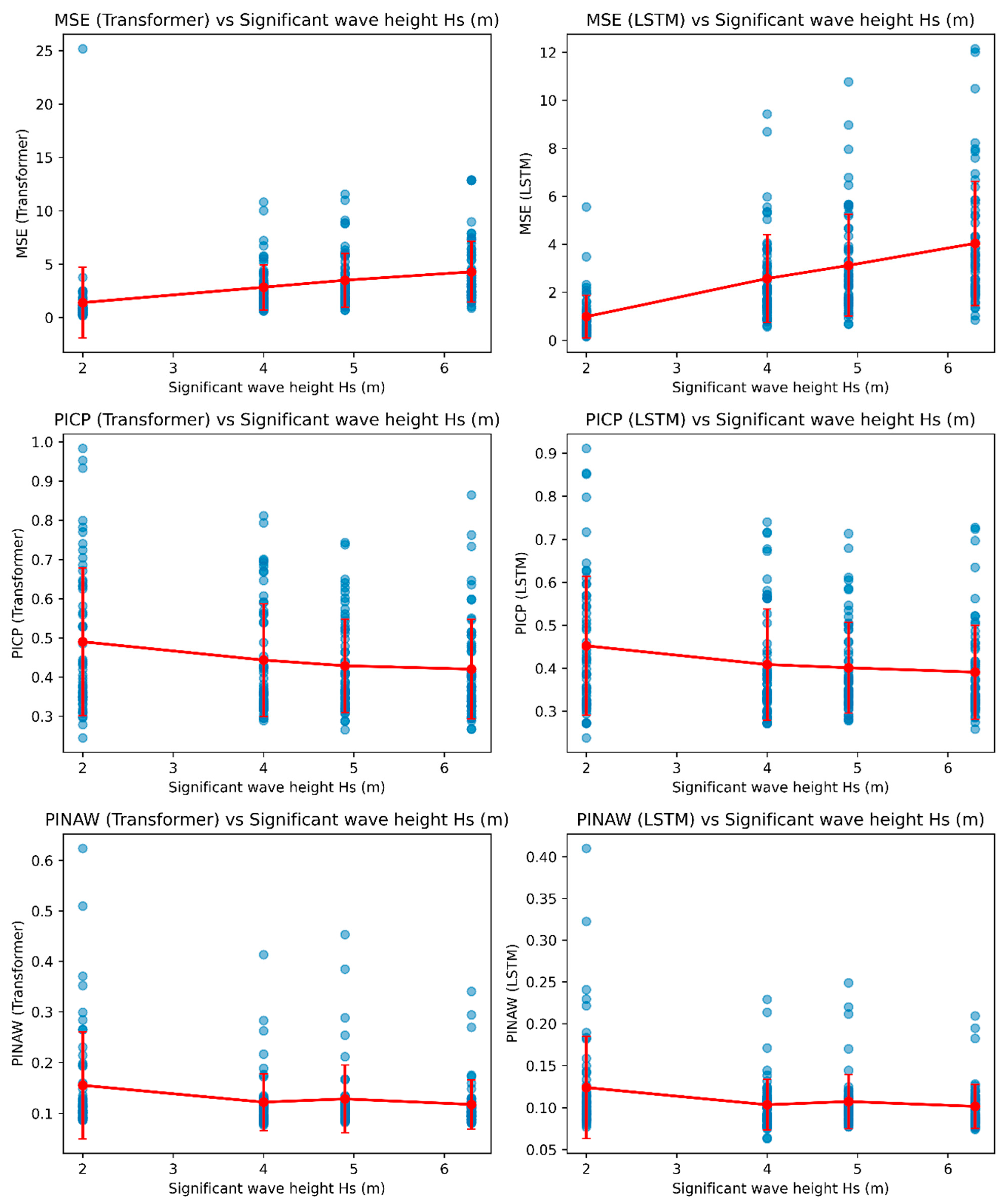

- MSE—prediction accuracy,

- PICP—reliability of the confidence interval,

- PINAW—width of the uncertainty interval.

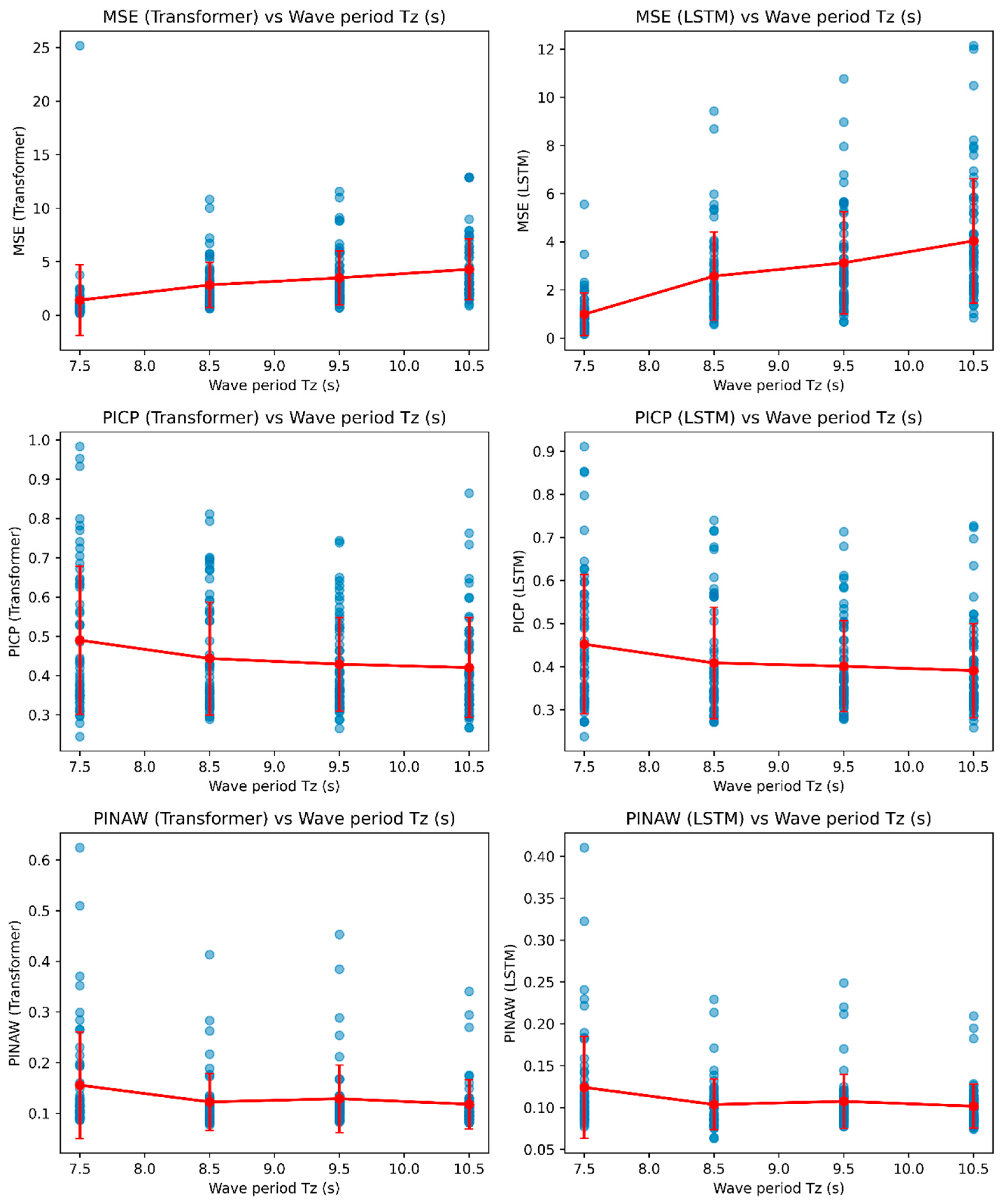

4.1. Car Ferry A—Effect of Wave Height and Period

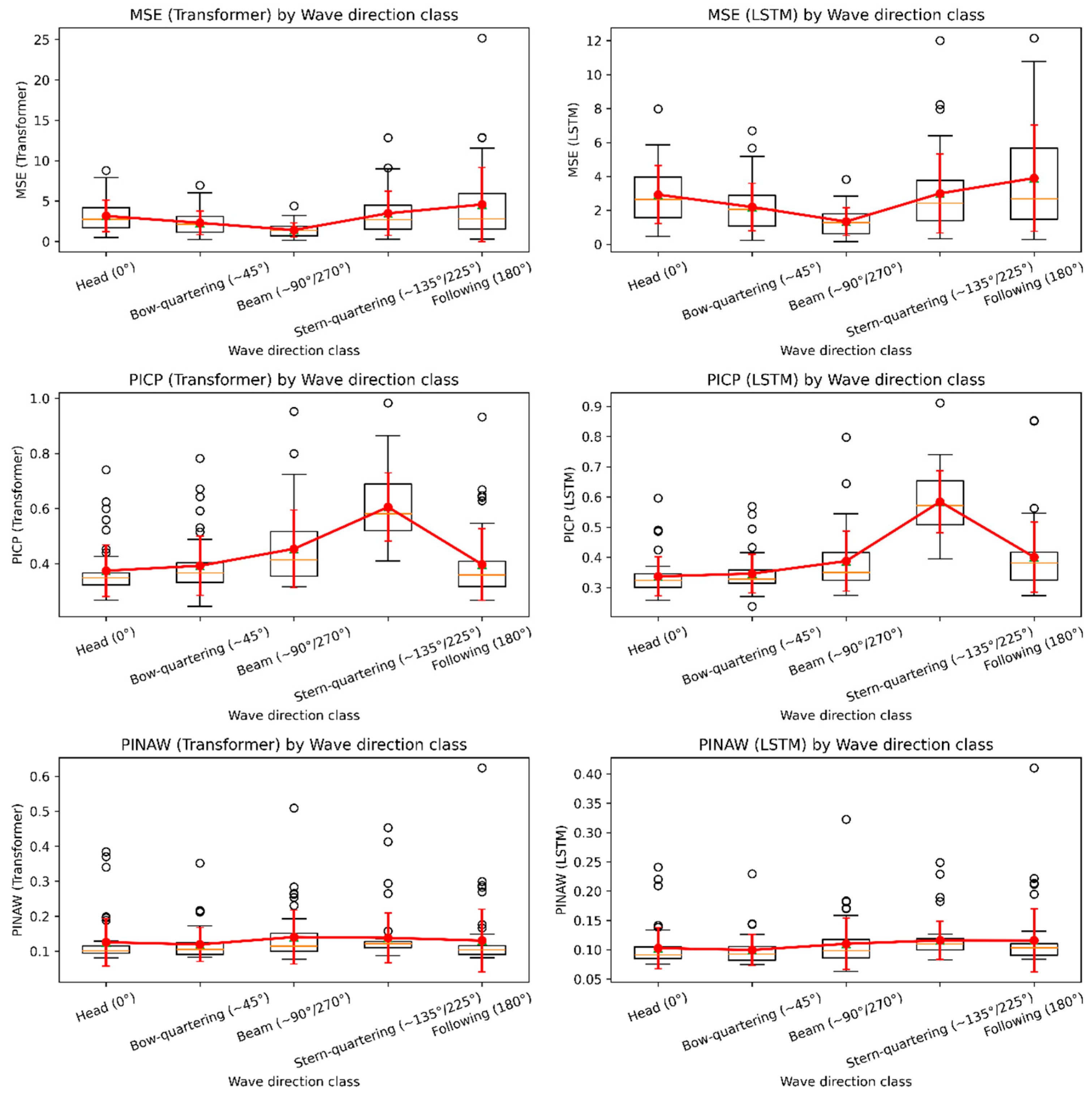

4.2. Car Ferry A—Effect of Wave Direction

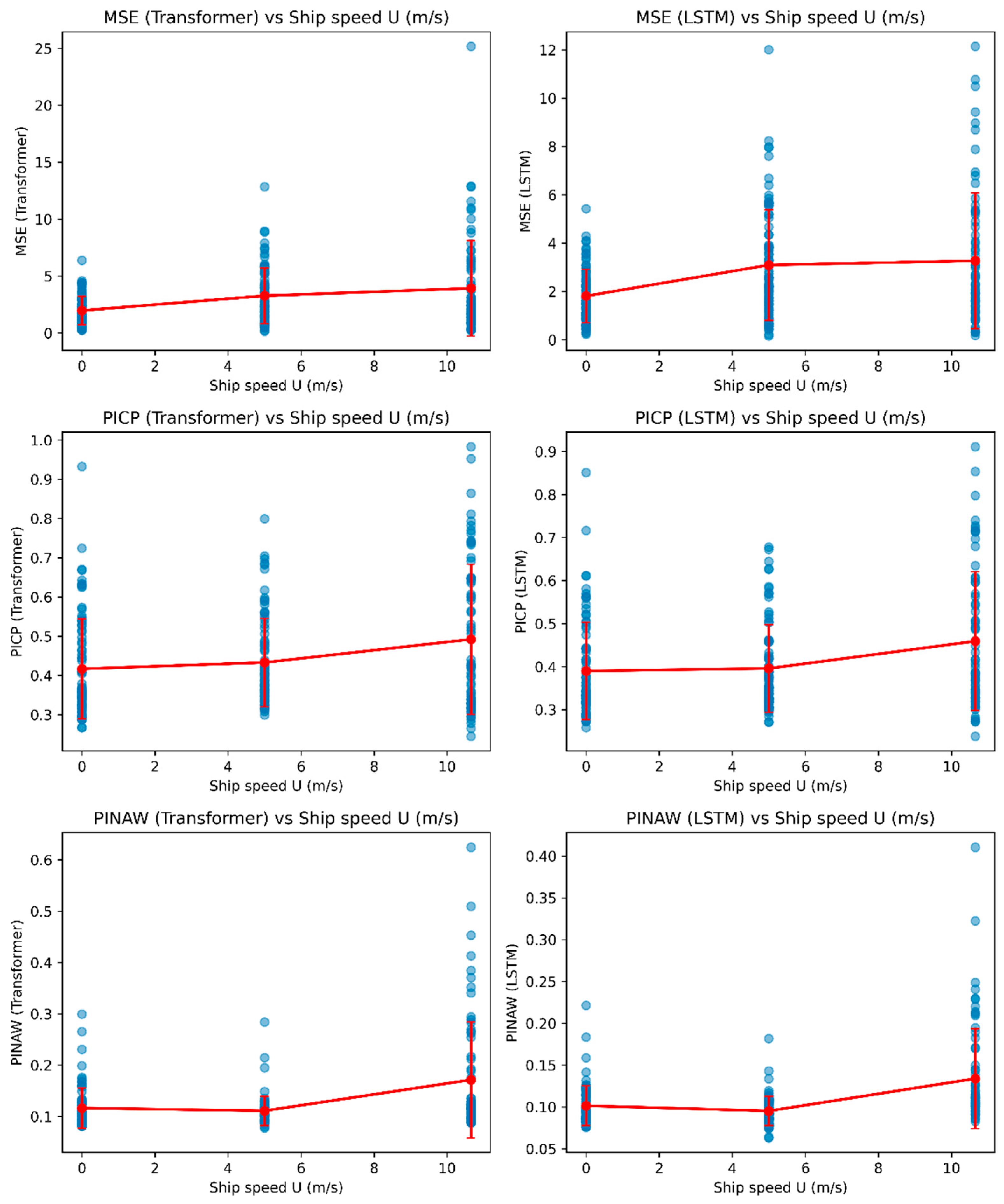

4.3. Car Ferry A—Effect of Ship Speed

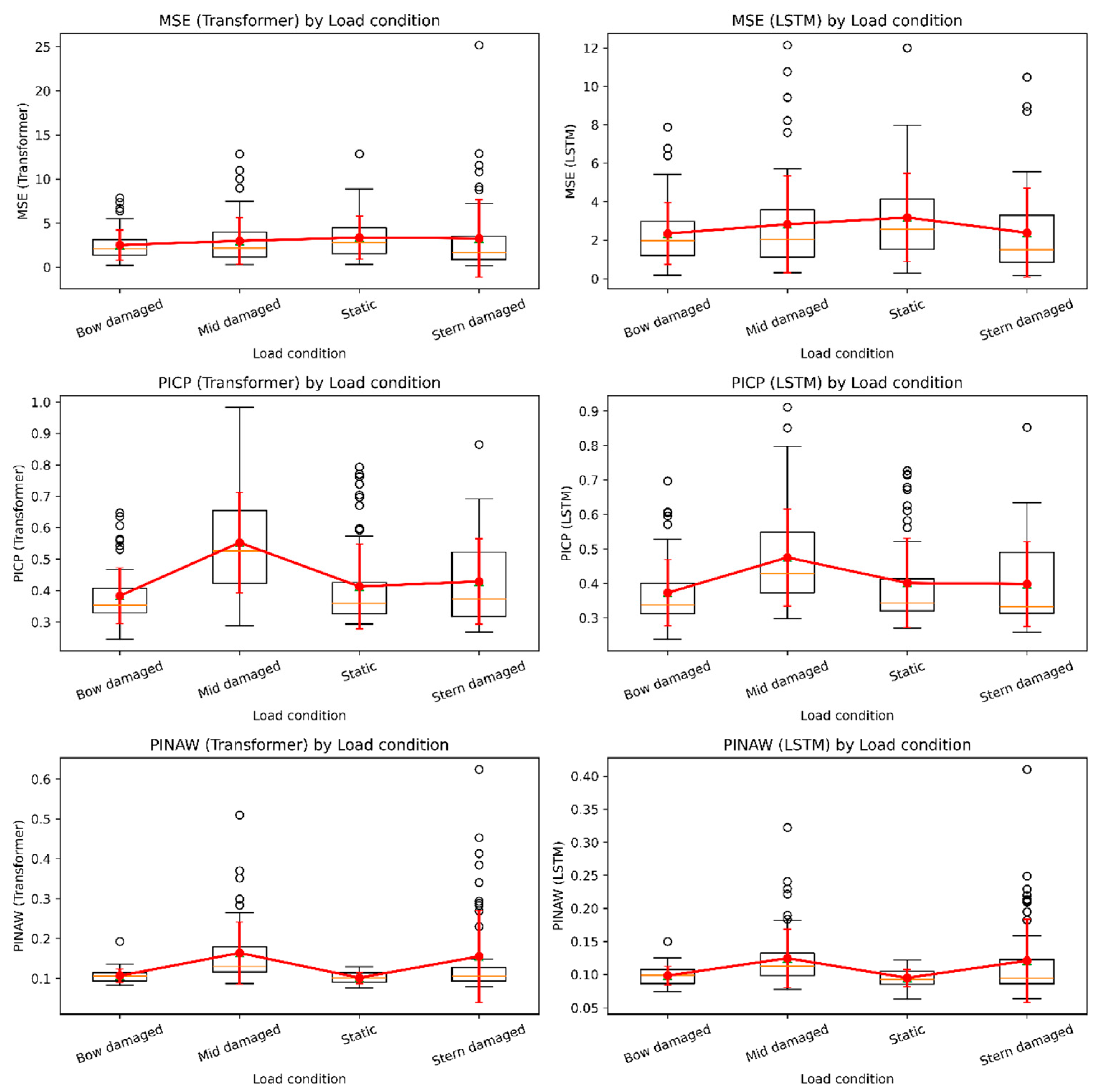

4.4. Car Ferry A—Effect of Loading and Damage Condition

4.5. Car Ferry B—Effect of Wave Height and Period

4.6. Car Ferry B—Effect of Wave Direction

4.7. Car Ferry B—Effect of Ship Speed

4.8. Car Ferry B—Effect of Loading and Damage Condition

4.9. Summary of Car Ferry A and B

- LSTM: Precise and efficient in short-term motion forecasting—suitable for real-time monitoring and onboard stability evaluation.

- Transformer: Effective in probabilistic representation—advantageous for risk-aware control, damage assessment, and safety margin estimation.

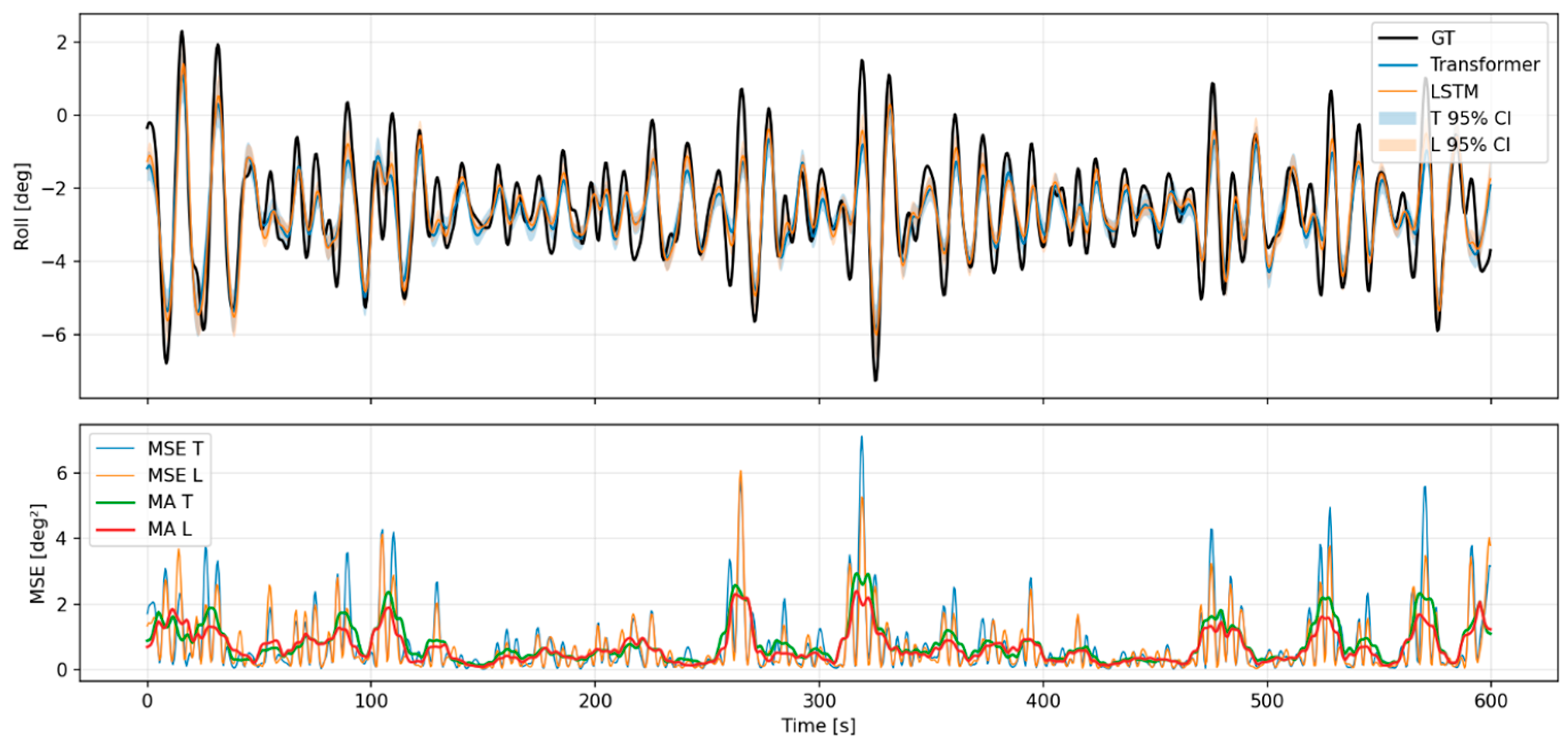

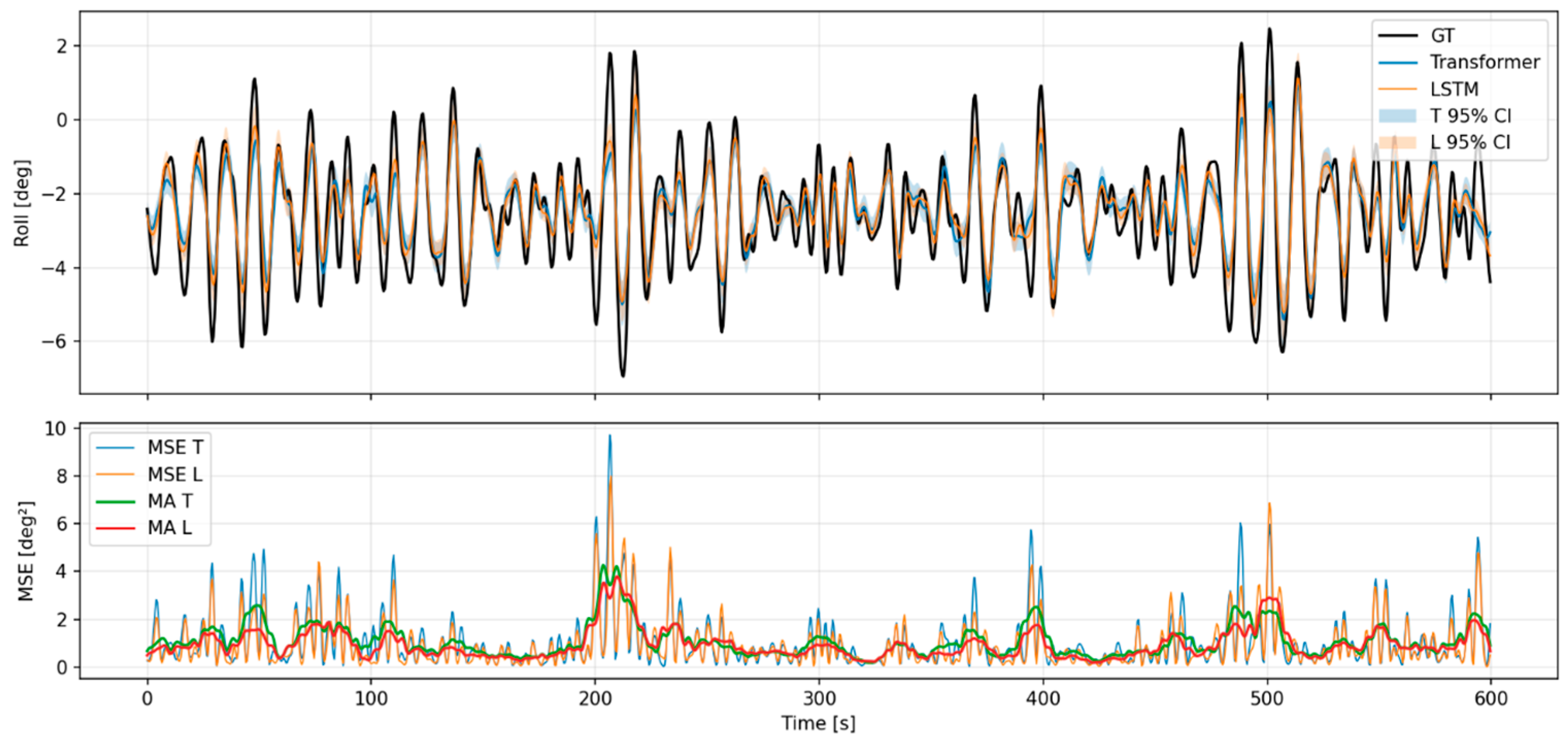

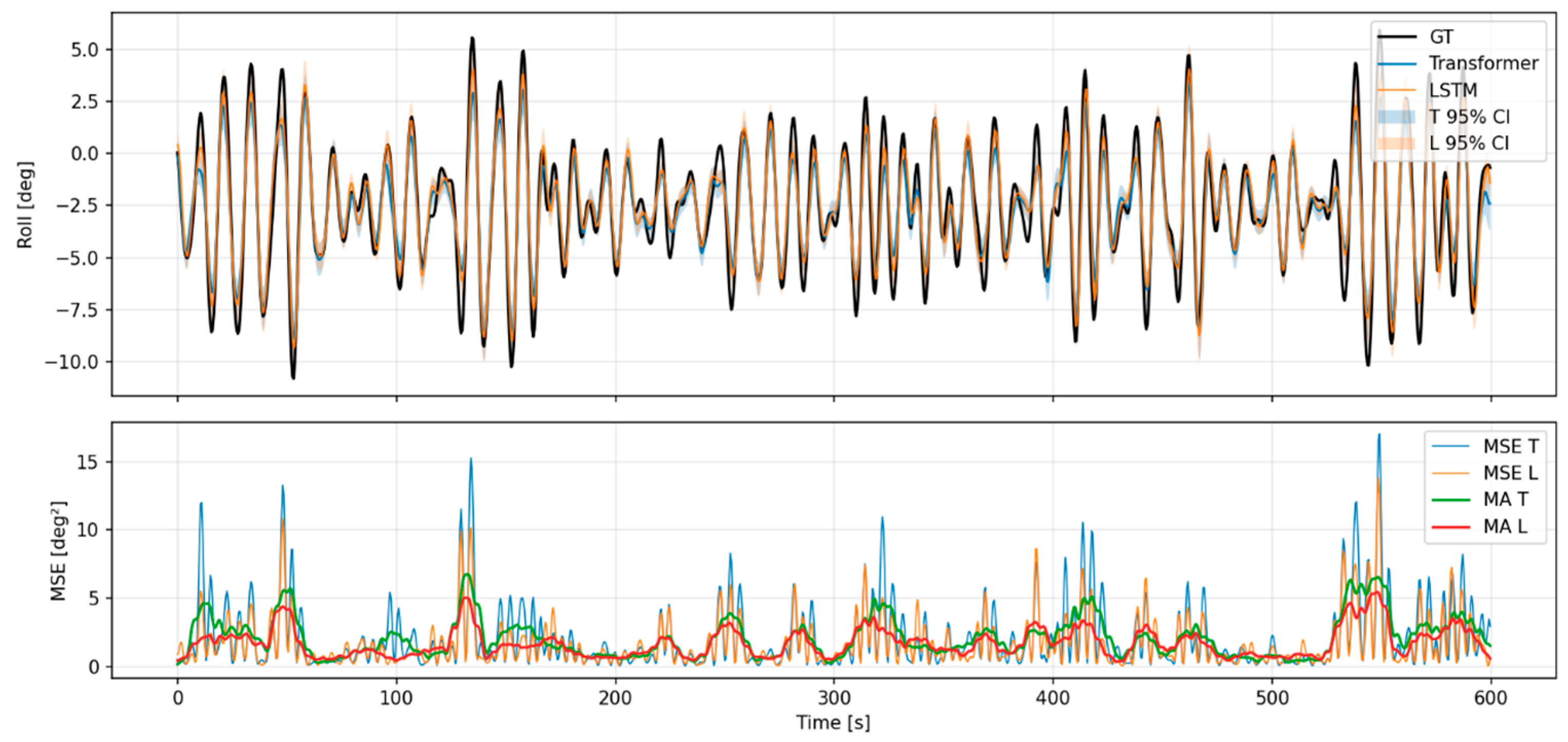

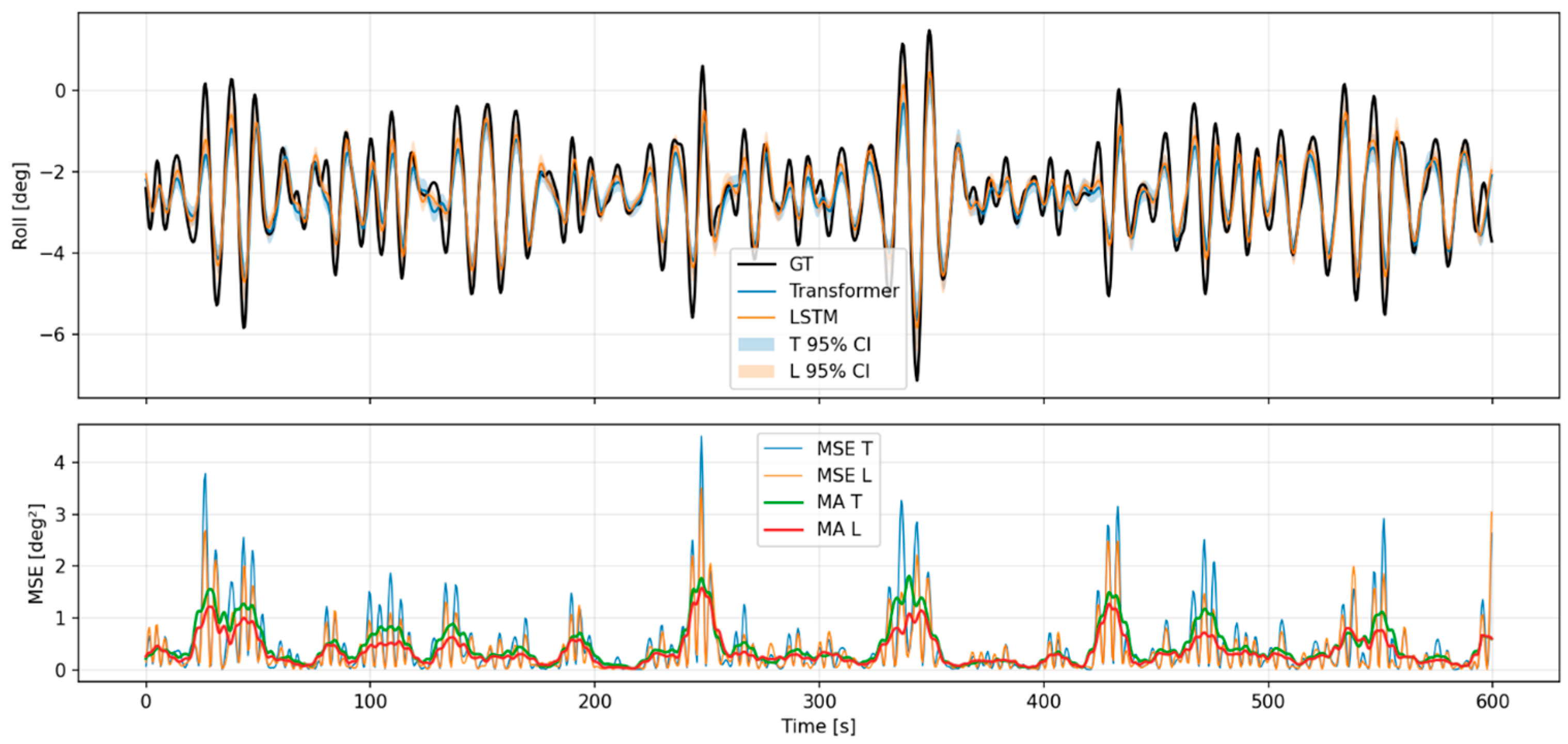

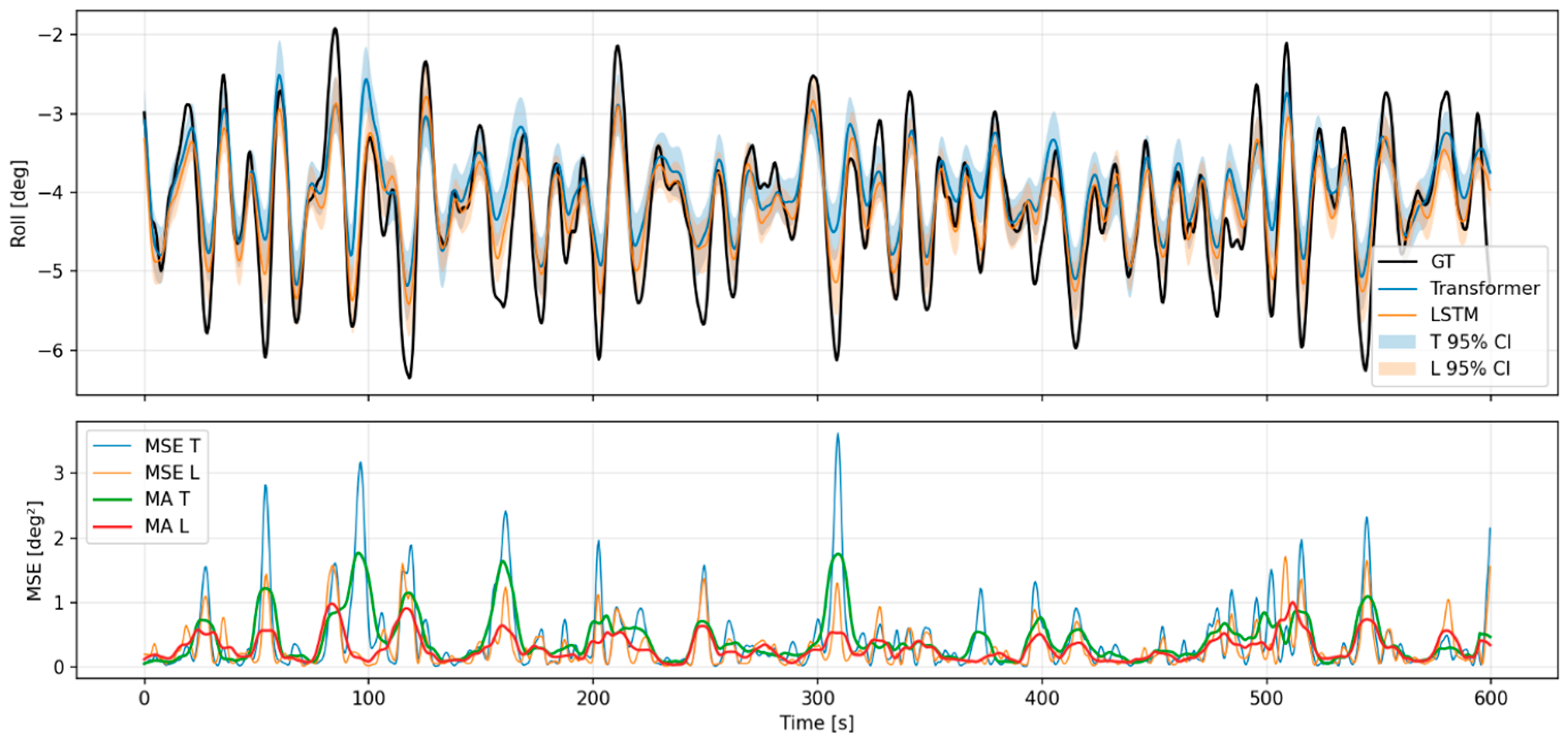

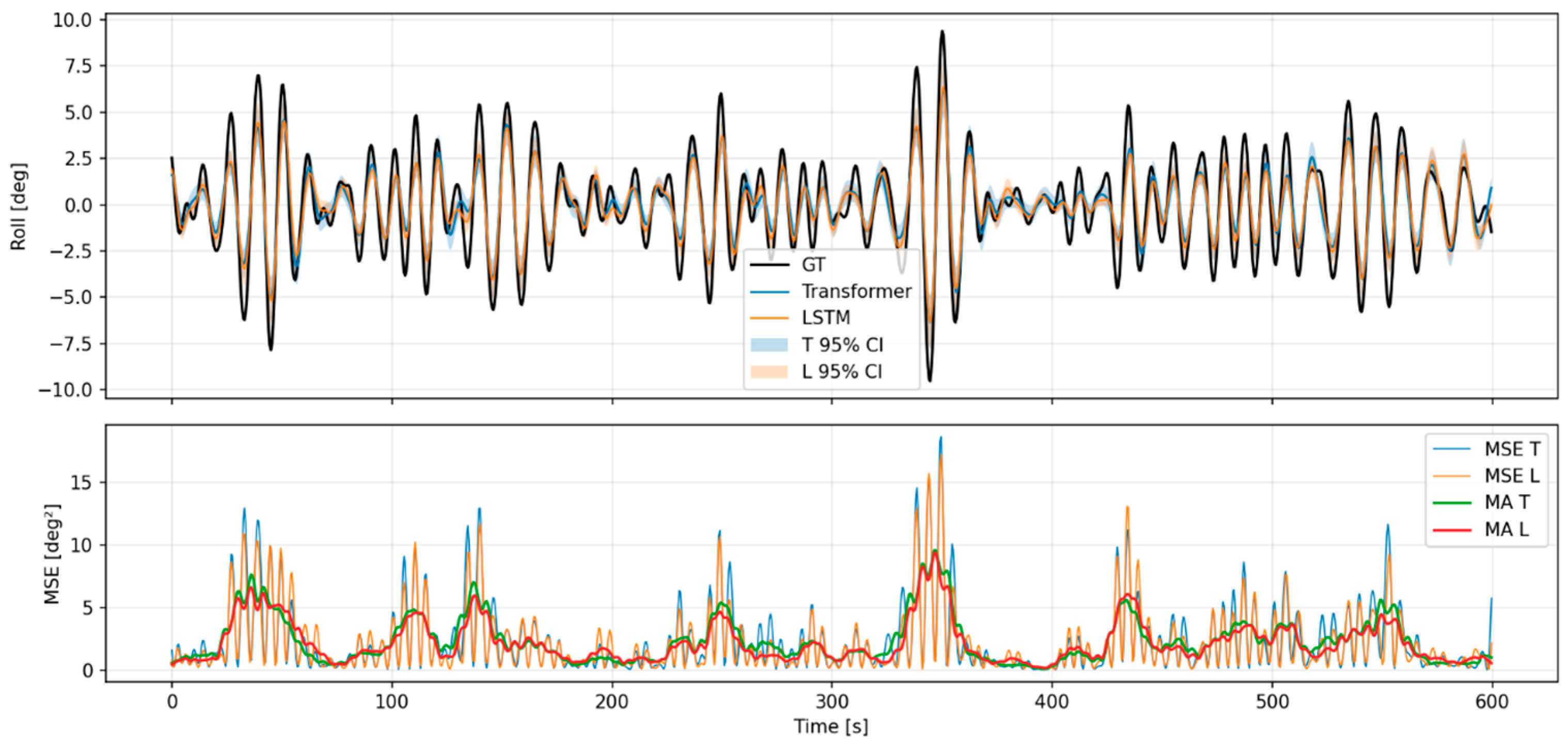

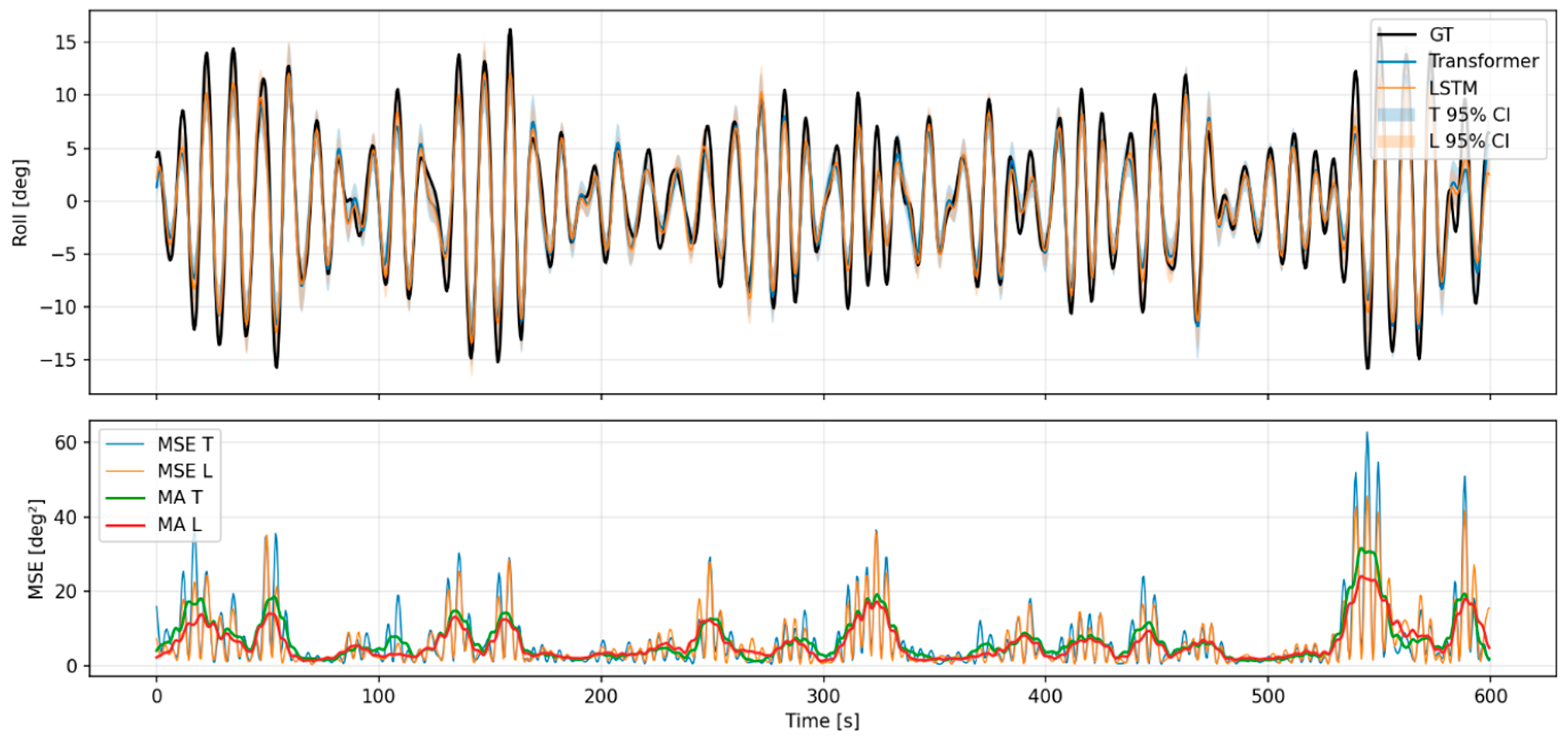

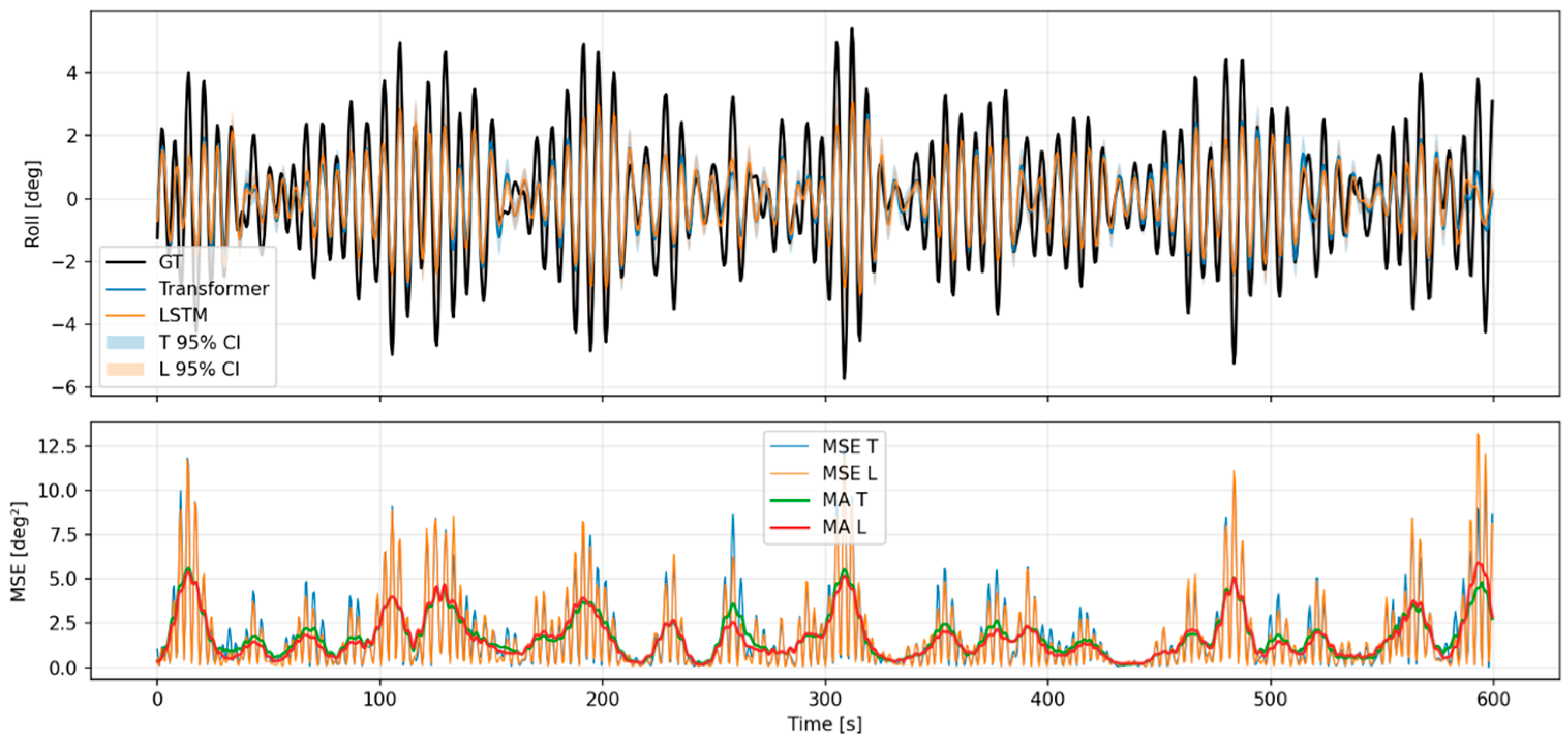

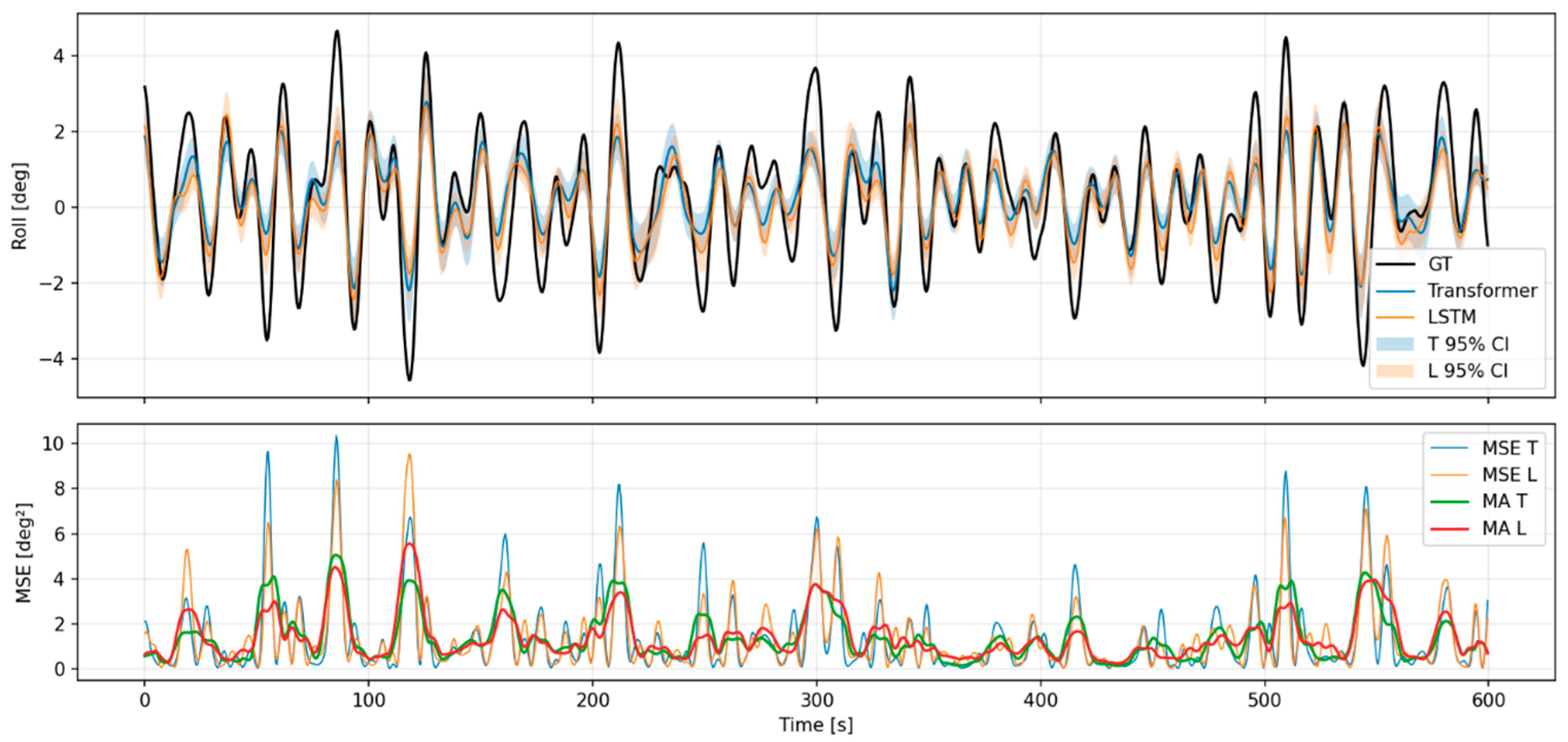

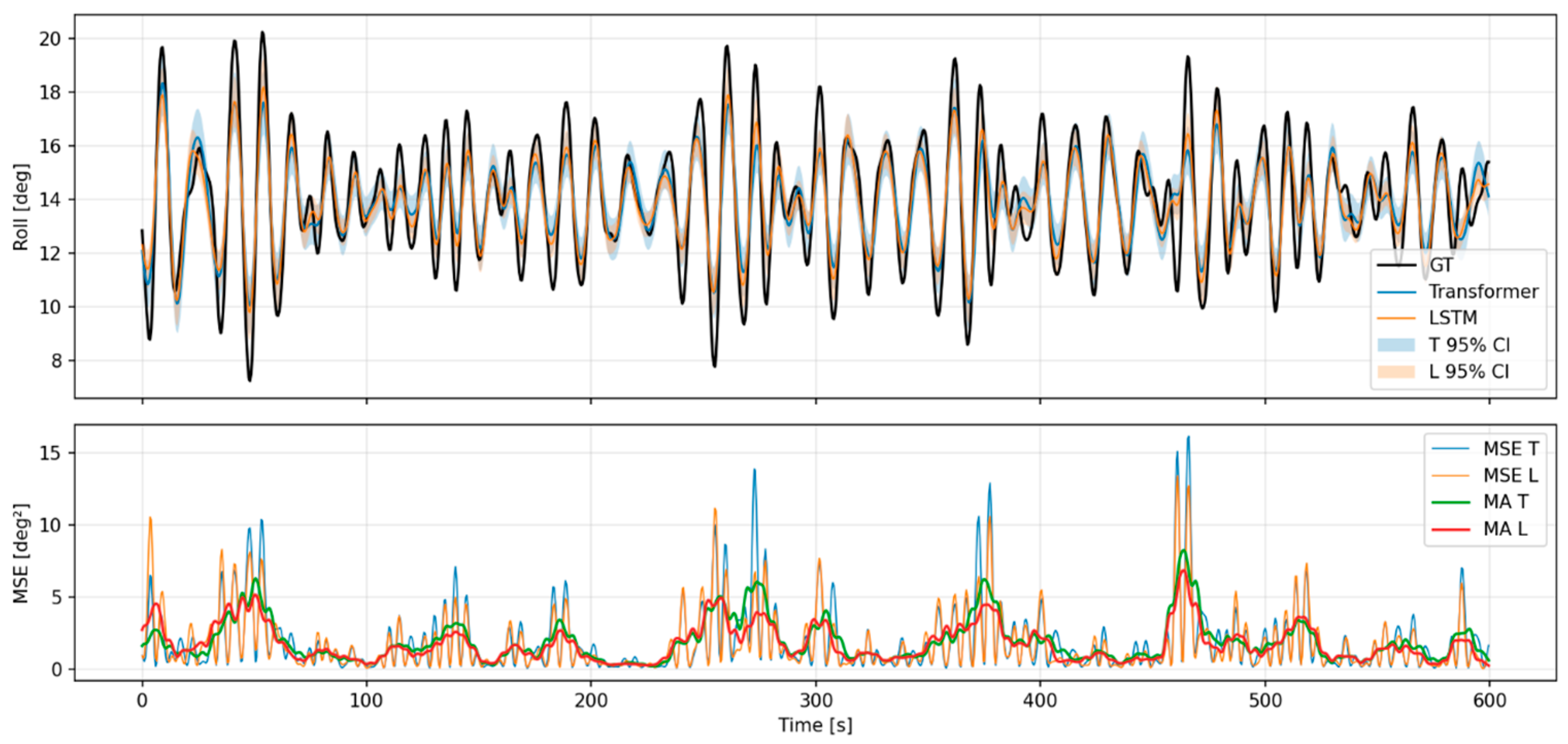

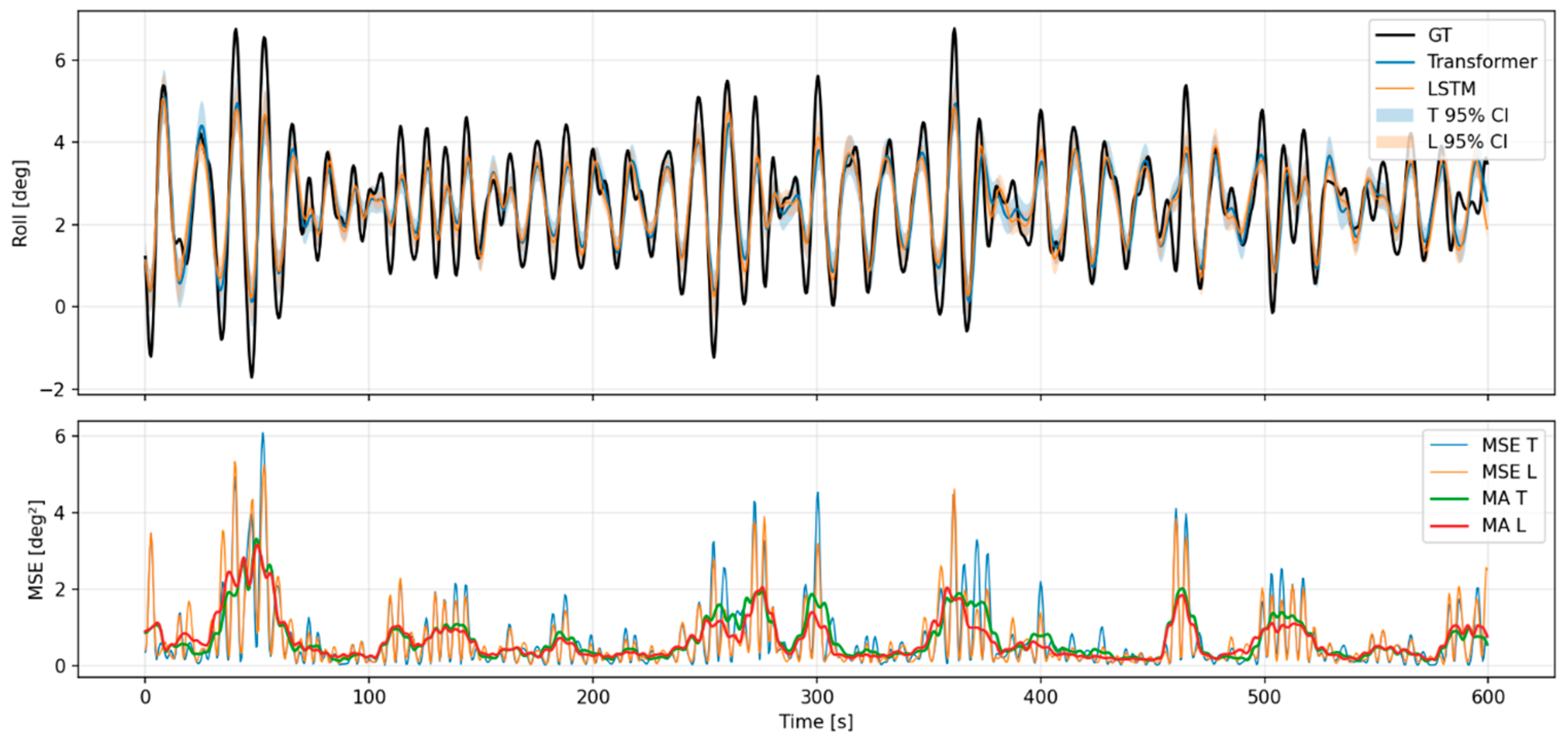

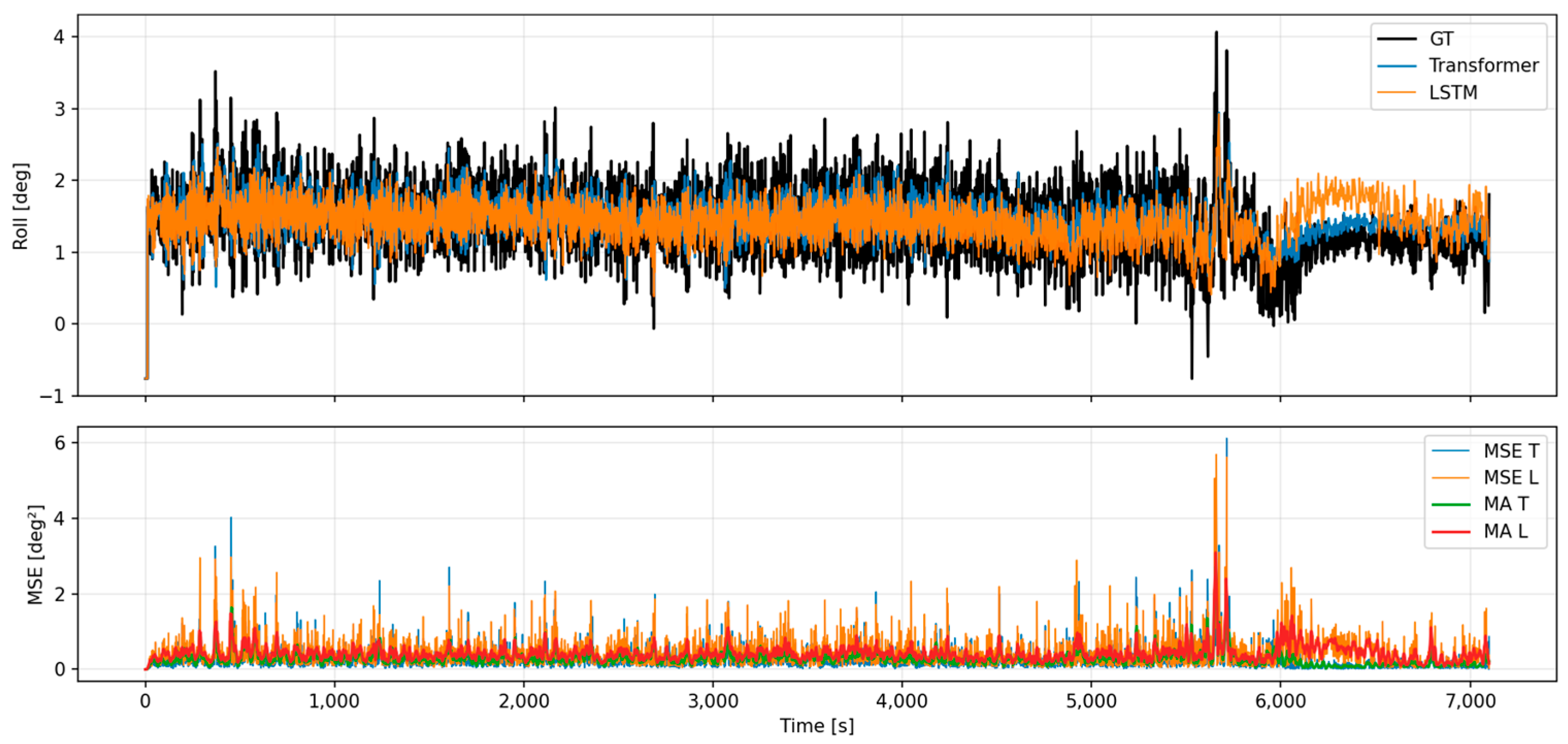

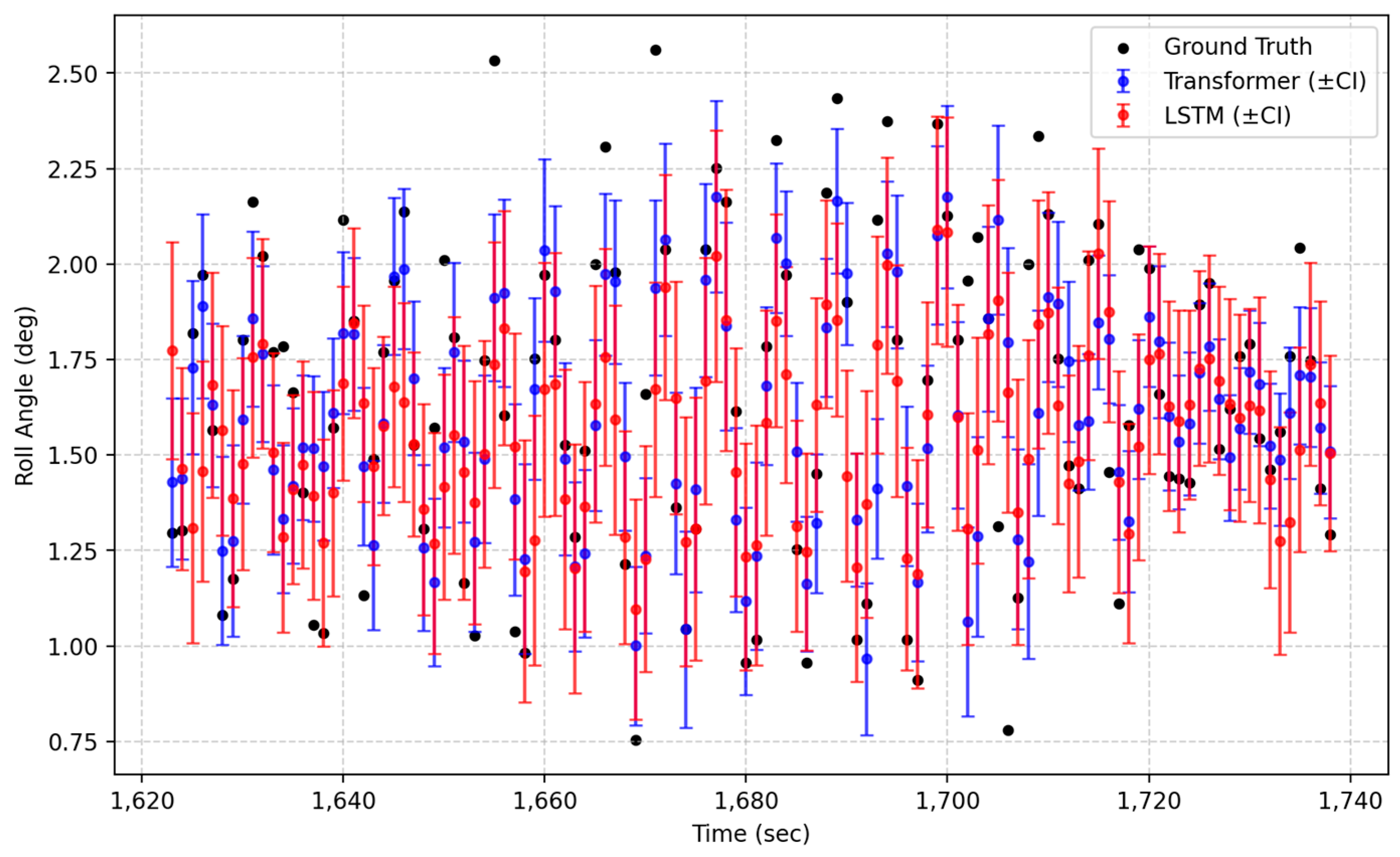

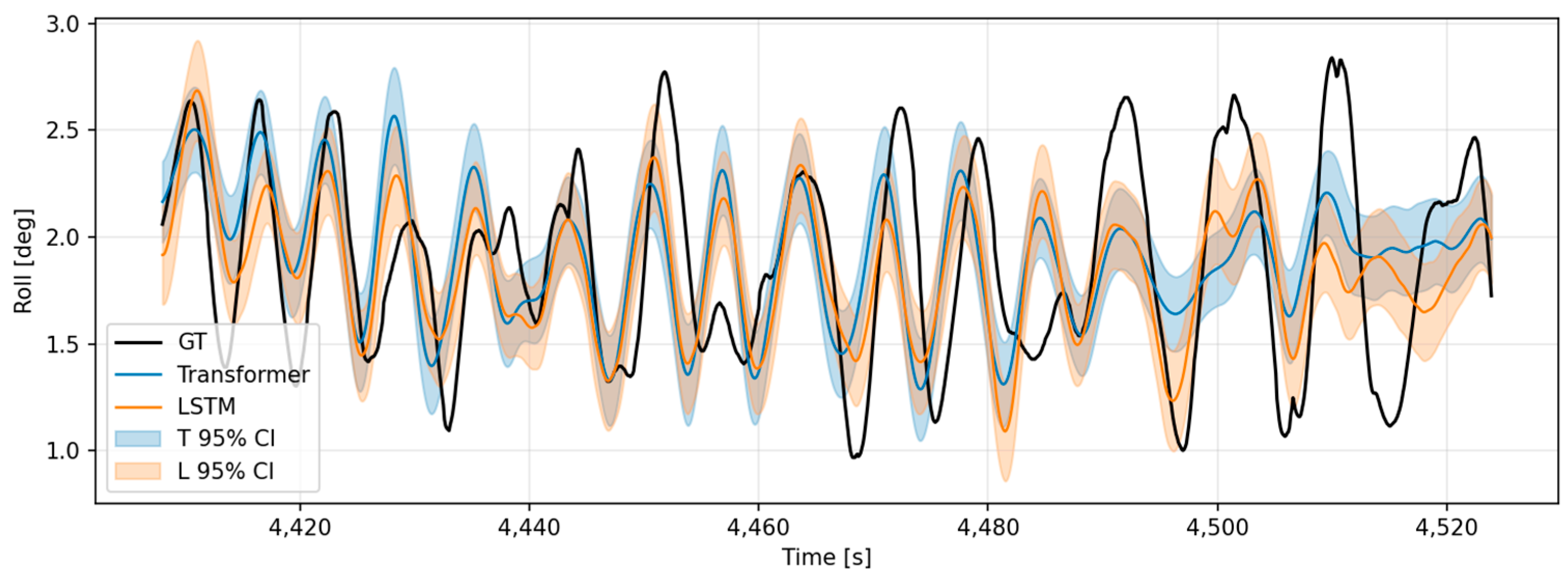

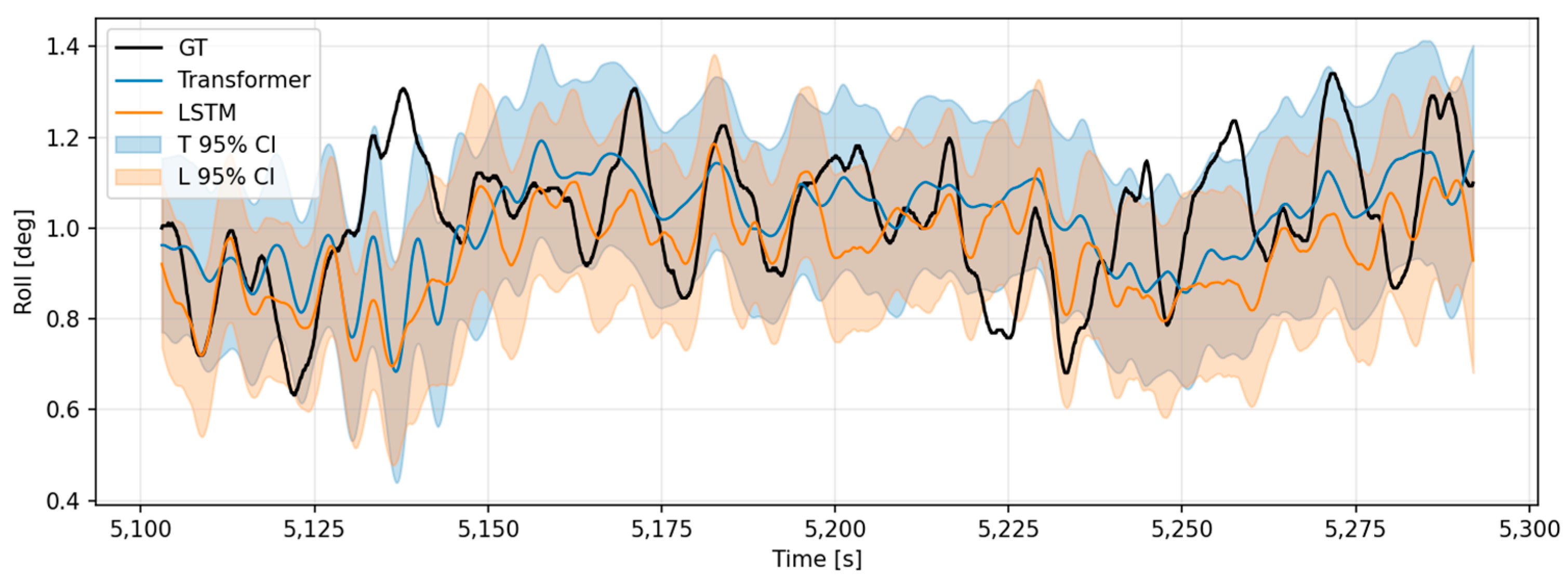

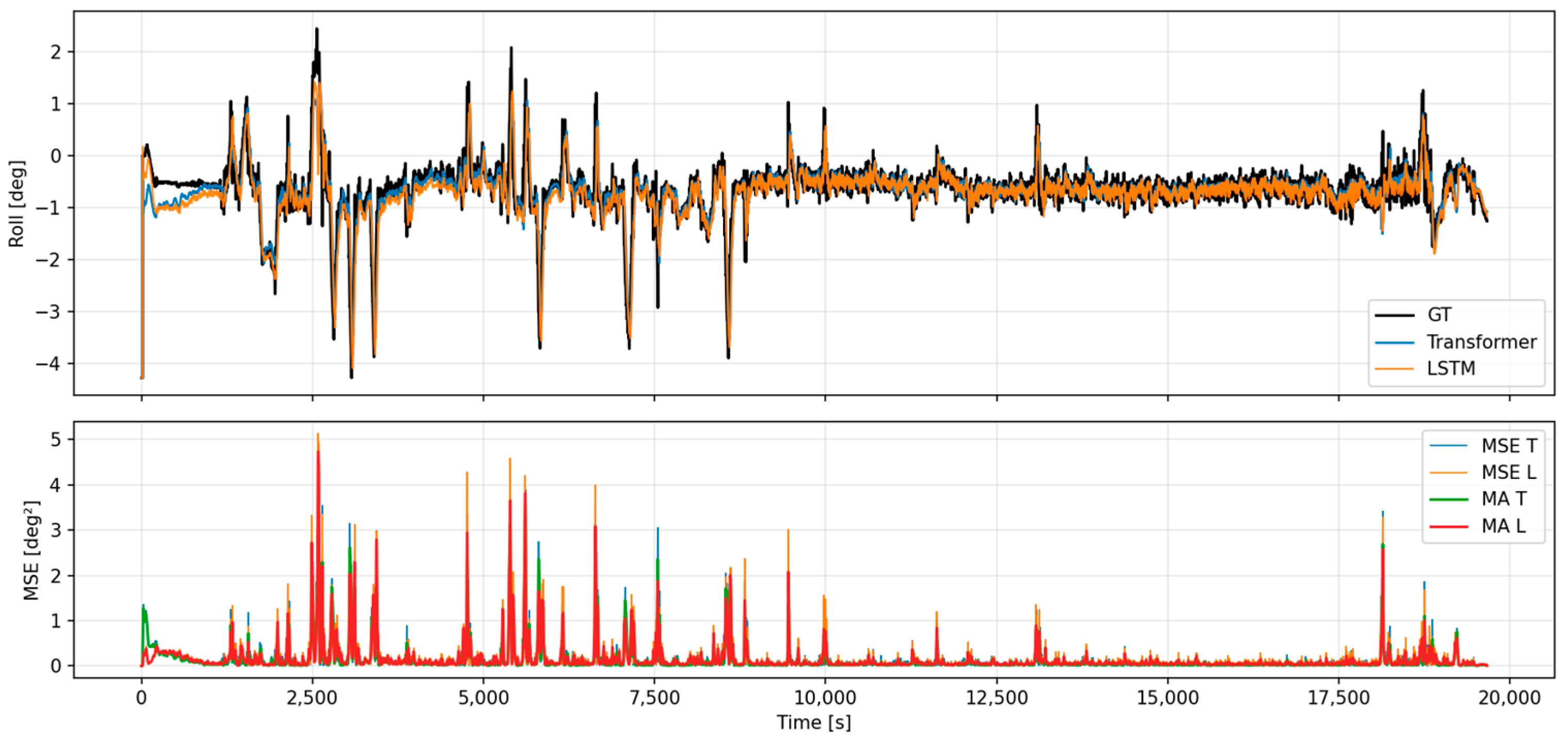

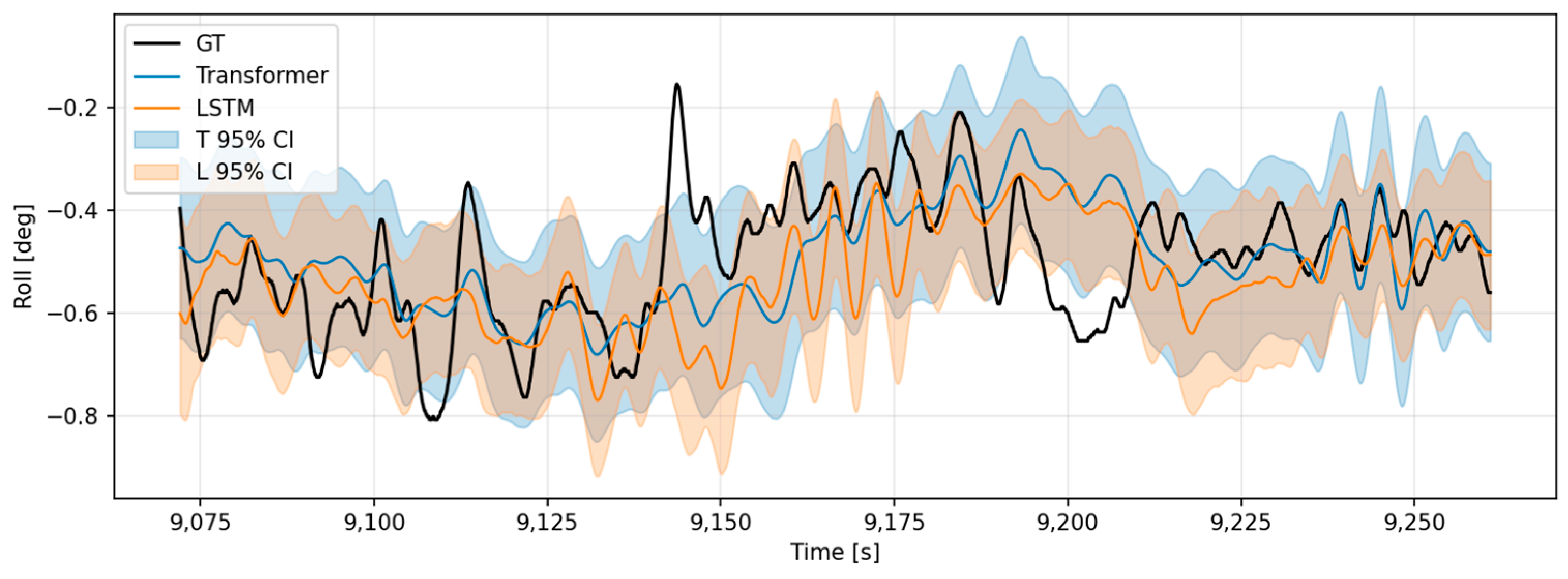

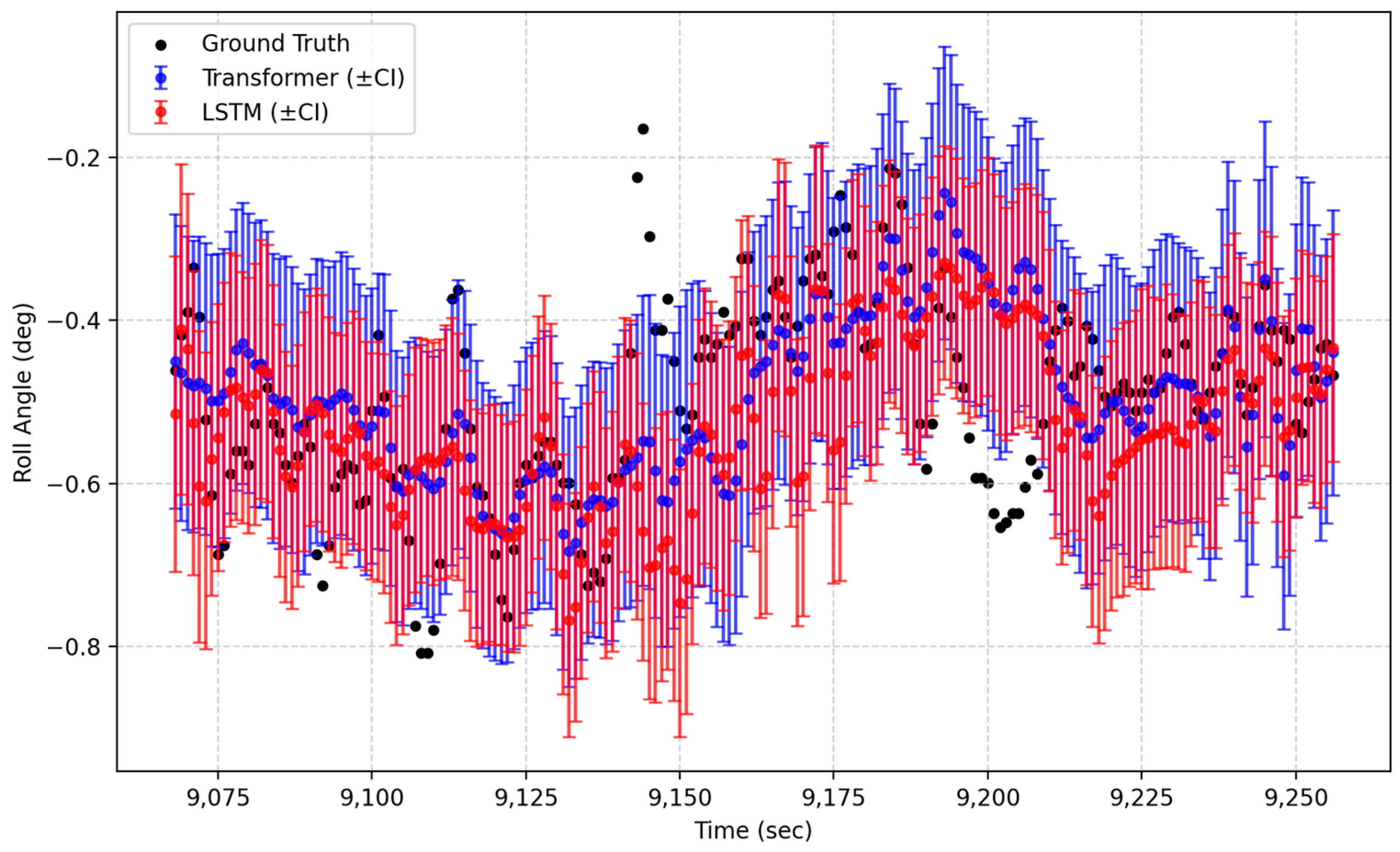

4.10. Real-Voyage Data Evaluation

- (1)

- Evaluation Overview

- (2)

- Comparative Analysis

- Accuracy (MSE):

- Uncertainty metrics:

- Accuracy (MSE):

- Uncertainty metrics:

- (3)

- Visualization and Interpretation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Predictive Results for Each Model of Motion Analysis Data (Car Ferry A)

Appendix A.2. Predictive Results for Each Model of Motion Analysis Data (Car Ferry B)

References

- Lee, H.; Ahn, Y. Comparative Study of RNN-Based Deep Learning Models for Practical 6-DOF Ship Motion Prediction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Chuang, Z.; Hu, A. Online Data-Driven Integrated Prediction Model for Ship Motion Based on Data Augmentation and Filtering Decomposition and Time-Varying Neural Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhuang, S.; Wang, J.; Peng, X.; Liu, Y. Deep Learning-Based Non-Parametric System Identification and Interpretability Analysis for Improving Ship Motion Prediction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Qiang, H.; Peng, X. Vessel Trajectory Prediction Using Vessel Influence Long Short-Term Memory with Uncertainty Estimation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, S. A Hybrid Framework Integrating End-to-End Deep Learning with Bayesian Inference for Maritime Navigation Risk Prediction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yin, J. Probabilistic Interval Prediction of Ship Roll Motion Using Multi-Resolution Decomposition and Non-Parametric Kernel Density Estimation. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2025, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.-X.; Yin, J.-C. Real-Time Ship Roll Prediction via a Novel Stochastic Trainer-Based Feedforward Neural Network. China Ocean Eng. 2025, 39, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, S.; Forti, N.; Millefiori, L.M.; Braca, P.; Willett, P. Recurrent Encoder-Decoder Networks for Vessel Trajectory Prediction with Uncertainty Estimation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.-F.; Yan, H.-C.; Xu, J.-B. A Heave Motion Prediction Approach Based on Sparse Bayesian Learning Incorporated with Empirical Mode Decomposition for an Underwater Towed System. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.-J.; Yu, P.-Y.; Wang, Q.; Dong, Y.-K. Short-Term Motion Prediction of a Semi-Submersible by Combining LSTM Neural Network and Different Signal Decomposition Methods. Ocean Eng. 2023, 267, 113266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-Y.; Wang, T.-T.; Li, G.-Y.; Skulstad, R.; Zhang, H.-X. Short-Term Ship Roll Motion Prediction Using the Encoder–Decoder Bi-LSTM with Teacher Forcing. Ocean Eng. 2024, 295, 116917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zheng, X.-Q.; Liu, M.-X. Multiscale Attention-Based LSTM for Ship Motion Prediction. Ocean Eng. 2021, 230, 109066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.M.; Maki, K.J. Data-Driven System Identification of 6-DoF Ship Motion in Waves with Neural Networks. Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 125, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Song, S. Machine Learning for Short-Term Prediction of Ship Motion Combined with Wave Input. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zeng, D.; Liu, H. Short-Term Ship Motion Attitude Prediction Based on LSTM and GPR. J. Ocean Res. 2022, 21, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Li, W. A Data-Driven Method for Ship Motion Forecast. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, H. A Pre-Trained Multi-Step Prediction Informer for Ship Motion Prediction with a Mechanism-Data Dual-Driven Framework. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lim, J. Prediction for Ship Roll Motion by Stacked Deep Learning Model. JKIIS 2023, 33, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNV GL AS. Feature Description Software Suite for Hydrodynamic and Structural Analysis of Ships and Offshore Structures. DNV GL—Digital Solutions, 2020. Available online: https://share.google/PBITu308WJ8jzG4Of (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- DNV. Hydrodynamic Analysis and Stability Analysis Software—HydroD. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/services/hydrodynamic-analysis-and-stability-analysis-software-hydrod-14492/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutník, J.; Steunebrink, B.R.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A Search Space Odyssey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 28, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, P.; Uszkoreit, J.; Vaswani, A. Self-Attention with Relative Position Representations. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018; pp. 464–468. [Google Scholar]

- Der Kiureghian, A.; Ditlevsen, O. Aleatory or epistemic? Does it matter? Struct. Saf. 2009, 31, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, A.; Gal, Y. What uncertainties do we need in Bayesian deep learning for computer vision? In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 5574–5584. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Y.; Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a Bayesian Approximation: Representing Model Uncertainty in Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2016), New York, NY, USA, 20–22 June 2016; Volume 48, pp. 1050–1059. [Google Scholar]

| Information | Car Ferry A | Car Ferry B |

|---|---|---|

| Principal dimensions (L/B/T) | 160/24.8/5.3 m | 167/25.6/6.0 m |

| Natural rolling period | 9.5–11.4 s | 11.6–18.9 s |

| Operational data | Entry into Jeju (10 Hz) Departure from Jeju (10 Hz) | Entry into Jeju (20 Hz) Departure from Jeju (20 Hz) |

| Station Name (Standard Station Number) | Chujado (22184) |

|---|---|

| Managing Organization | Korea Meteorological Administration, Jeju Regional Meteorological Office, Observation Division |

| Address | Offshore, 49 km northwest of Jeju Port, Jeju-si, Jeju Special Self-Governing Province |

| Observation Start Date | Operational data |

| Observation Interval (minutes) | 30 |

| Coordinates (WGS84) | Latitude: 33.79361/Longitude: 126.14111111 |

| Water Depth (m) | 85 |

| Case | Heading (°) | Wave Direction (°) | Relative Wave Direction ) | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 189 | 97 | −92° | Beam Sea (Port) |

| B | 189 | 320 | 131° | Quartering Sea (Starboard) |

| C | 25 | 97 | 72° | Quartering Sea (Starboard) |

| D | 25 | 320 | −65° | Quartering Sea (Port) |

| Wave Condition | GEV Distribution | Significant Wave Height | Wave Period | Wave Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | 10 years | 2 m | 7.5 s | 0–315° (45° interval) |

| Wave 2 | 100 years | 4 m | 8.5 s | |

| Wave 3 | 200 years | 4.9 m | 9.5 s | |

| Wave 4 | 500 years | 6.3 m | 9.5 s |

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Ship speed (m/s) | 10.65/5/0 |

| Hull condition | Intact/Bow flooding/Midship flooding/Aft flooding |

| Hs (m) | 2/4/4.9/6.3 |

| Tz (s) | 7.5/8.5/9.5/9.5 |

| Wave direction (°) | 0/45/90/135/180/225/270/315 |

| Total cases | 384 |

| Category | Specification |

|---|---|

| Input/Output | Input: (); Output: () |

| Model structure | LSTM (→ hidden = 128, = 2, Dropout = 0.1, batch first = True) |

| Pooling | Mean pooling of all LSTM time outputs → (, 128) |

| Prediction head | Dropout (0.1) → Linear (128 → × 2) → output () |

| Loss function | Composite: MSE + β·(1 − PICP) + γ·PINAW, |

| Uncertainty estimation | Same as Transformer (, compute ±1.96σ interval) |

| Optimizer | AdamW (lr = 3 × 10−4, wd = 1 × 10−2) with linear warm-up (10%) and CosineAnnealingLR |

| Epochs/Batch size | 80 epochs/batch size = 128 |

| Category | Specification |

|---|---|

| Input/Output | Input: (); Output: () |

| Preprocessing | Linear (→ 128); learned positional encoding initialized with N (0, 0.022) |

| Encoder | TransformerEncoder × 3 (= 128, nhead = 8, = 512, Dropout = 0.1, activation = GELU, batch_first = True) + final LayerNorm |

| Concatenation | Concatenate last hidden state ( and mean-pooled feature ) → (, 256) |

| Prediction head | Linear (256 → 128) → GELU → Dropout (0.1) → Linear (128 → × 2) () |

| Loss function | Composite: MSE (μ, y) + β·(1−PICP) + γ·PINAW |

| Uncertainty estimation | Decompose output into μ and σ = exp (0.5·logσ2); derive 95% CI = μ ± 1.96σ |

| Optimizer | AdamW (lr = 3 × 10−4, weight_decay = 1 × 10−2) |

| Scheduler | Linear warm-up (10% epochs) → CosineAnnealingLR |

| Epochs/Batch size | 80 epochs/batch size = 128 |

| Parameter | ΔMSE (T−L) | ΔPICP (T−L) | ΔPINAW (T−L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Significant wave height (Hs) | +0.182 | +0.003 | +0.016 |

| Wave period (Tz) | +0.182 | +0.003 | +0.016 |

| Wave direction | +0.182 | +0.003 | +0.016 |

| Ship speed (U) | +0.177 | +0.003 | +0.016 |

| Load condition (L/C) | +0.178 | +0.005 | +0.017 |

| Parameter | ΔMSE (T−L) | ΔPICP (T−L) | ΔPINAW (T−L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Significant wave height (Hs) | +0.323 | +0.032 | +0.022 |

| Wave period (Tz) | +0.323 | +0.032 | +0.022 |

| Wave direction | +0.315 | +0.033 | +0.022 |

| Ship speed (U) | +0.338 | +0.032 | +0.022 |

| Load condition (L/C) | +0.348 | +0.032 | +0.022 |

| Vessel | Route | MSE (T) | MSE (L) | ΔMSE (T–L) | PICP (T) | PICP (L) | PINAW (T) | PINAW (L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car Ferry A | Entry to Jeju | 0.2350 | 0.2638 | −0.0288 | 0.345 | 0.388 | 0.100 | 0.125 |

| Departure from Jeju | 0.2328 | 0.2515 | −0.0187 | 0.207 | 0.264 | 0.096 | 0.124 | |

| Car Ferry B | Entry to Jeju | 0.0384 | 0.0426 | −0.0042 | 0.234 | 0.222 | 0.099 | 0.101 |

| Departure from Jeju | 0.0167 | 0.0193 | −0.0026 | 0.263 | 0.236 | 0.100 | 0.102 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, G.-y.; Lim, C.; Oh, S.-j.; Nam, I.-h.; Lee, Y.-m.; Shin, S.-c. Deep Learning-Based Prediction of Ship Roll Motion with Monte Carlo Dropout. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2378. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122378

Kim G-y, Lim C, Oh S-j, Nam I-h, Lee Y-m, Shin S-c. Deep Learning-Based Prediction of Ship Roll Motion with Monte Carlo Dropout. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2378. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122378

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Gi-yong, Chaeog Lim, Sang-jin Oh, In-hyuk Nam, Yu-mi Lee, and Sung-chul Shin. 2025. "Deep Learning-Based Prediction of Ship Roll Motion with Monte Carlo Dropout" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2378. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122378

APA StyleKim, G.-y., Lim, C., Oh, S.-j., Nam, I.-h., Lee, Y.-m., & Shin, S.-c. (2025). Deep Learning-Based Prediction of Ship Roll Motion with Monte Carlo Dropout. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2378. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122378