Abstract

Offshore wind turbine support structures are in harsh and unsteady marine environments, and their dynamic characteristics could change gradually after long-term service. To better understand the status and improve remaining life estimation, it is essential to conduct in situ measurement and update the numerical models of these support structures. In this paper, the modal properties of a 5.5 MW offshore wind turbine were first identified by a widely used operational modal analysis technique, frequency-domain decomposition, given the acceleration data obtained from eight sensors located at four different heights on the tower. Then, a finite element model was created in MATLAB R2020a and a set of model parameters including scour depth, foundation stiffness, hydrodynamic added mass and damping coefficients was updated in a Bayesian inference frame. It is found that the posterior distributions of most parameters significantly differ from their prior distributions, except for the hydrodynamic added mass coefficient. The predicted natural frequencies and damping ratios with the updated parameters are close to those values identified with errors less than 2%. But relatively large differences are found when comparing some of the predicted and identified mode shape coefficients. Specifically, it is found that different combinations of the scour depth and foundation stiffness coefficient can reach very similar modal property predictions, meaning that model updating results are not unique. This research demonstrates that the Bayesian inference framework is effective in constructing a more accurate model, even when confronting the inherent challenge of non-unique parameter identifiability, as encountered with scour depth and foundation stiffness.

1. Introduction

Effective evaluation of service performance of offshore wind turbines (OWTs) based on long-term monitoring data can provide better guidance for maintenance and repair strategy, and thus, catastrophic accidents could be avoided [1,2,3]. Installing monitoring systems such as the SCADA system, vibration measurement system and bolt stress monitoring system has become an industry standard. However, at present, most health monitoring systems installed in OWTs generally only provide information such as real-time power, total thrust of wind turbines and local stress of key components, and physics-based digital twins of OWTs in service are usually unavailable. Digital twins enable continuous assessment of the status of structural components in OWTs, so abrupt failures can be prevented in advance, unplanned downtime can be reduced, and OWTs’ operational life can be significantly extended. Therefore, those techniques that assist in creating better OWT digital twins have gradually drawn great attention.

To establish a digital twin that can reflect the current dynamic characteristics of an OWT, a model updating technique must be introduced [4]. In this technique, monitoring data is processed, and some parameters of the numerical model are modified to create a digital twin, ensuring that the dynamic characteristics can be as close to the measured OWT as possible. The monitoring data processing usually involves extracting the OWT’s modal parameters (natural frequencies, damping ratios and mode shapes) from data collected by various sensors (such as accelerometers and strain gauges). Identified modal properties can be regarded as the key information that bridges actual OWTs and their digital twins.

Many researchers have conducted research on wind turbine modal identification, and most of these studies processed vibration data collected under ambient excitations using operational model analysis (OMA) methods. For example, Dai et al. [5], Dong et al. [6], Koukoura et al. [7] and Hu et al. [8] used OMA methods including stochastic subspace identification (SSI), enhanced frequency-domain decomposition (FDD) and the least-squares complex frequency-domain method to identify wind turbine modal properties. Song et al. [9] collected vibration data of an offshore wind turbine on a jacket substructure for one year, and SSI was used to identify the modal parameters associated with the first and second modes. Since OMA methods are based on ambient excitations and the identified values (especially for damping) could be highly scattered, some researchers also attempted to use experimental modal analysis to identify wind turbine modal parameters. For example, Koukoura et al. [7] stimulated an OWT via boat collision and then identified its dynamic characteristics from decay responses. Chen et al. [10] proposed a method for identifying the aerodynamic damping matrix of wind turbines based on harmonic excitations and frequency response functions (FRFs).

When the extracted wind turbine modal parameters change significantly, it may indicate damage or other changes in the structure (e.g., scour, soil degradation, corrosion, etc.). Model updating techniques aim to minimize the difference between the system properties of numerical models and those of actual OWTs. Model updating can usually be achieved by matching modal parameters of numerical models with those of actual structures. Many scholars have conducted model updating studies on wind turbine towers and foundations [11,12,13,14,15,16]. For example, Cong et al. [11] studied the optimal sensor arrangement and developed a model updating technique based on complex mode expansion. Model parameters related to structure stiffness, damping, hydrodynamic additional mass and the soil–structure interaction were simultaneously updated, when only a small number of sensors are installed, and the modal data is incomplete. Xu et al. [16] and Ren et al. [17] built a digital twin of an OWT scale model in the laboratory based on a finite element model. There are also some scholars who directly conduct research on model updating based on measured data of full-scale wind turbines. Augustyn et al. [18] conducted a model updating study of a monopile-supported 5 MW OWT. The widely used SSI relies on assumptions including linearity and time invariance of dynamic systems to be identified, and white-noise external loads, but OWTs have a time-varying nature and nonlinear damping. Therefore, this study paid special attention to the feasibility of extracting modal parameters by SSI under operating conditions. Recently, Liang et al. [19] presented a new model updating method in the time domain for support condition identification of OWTs. Vibration tests on a scaled model of the DTU 10 MW OWT performed in the laboratory show that the proposed time-domain model updating method greatly improves the updating results considering nonlinear soil properties.

Probability-based methods have been introduced in many recent model updating studies for wind turbines. For example, Nabiyan et al. [20] conducted a Bayesian finite element model updating study based on test data collected from a 2 MW OWT at Bryce Wind Farm in the UK. At the same time, a classic modal-based model updating method was also attempted. The results show that both methods can accurately predict responses, while Bayesian methods can predict responses relatively more accurately. Moynihan et al. [21] measured the vibration data of a 6 MW monopile-supported OWT and conducted a study on system identification and model updating. They installed strain gauges and accelerometers at multiple heights of the towers and monopiles. The frequencies and mode shapes were matched with the corresponding values identified from the measurement data. The work also compares deterministic and probabilistic model updating methods. The results show that the deterministic model updating method can match the modal parameters with high accuracy in various datasets and environmental conditions. The Bayesian model updating method also successfully estimated the posterior distribution of model parameters, and the uncertainty of model parameters is further reduced with the increase in data volume. Similar works employing Bayesian model updating for wind turbines were conducted by Song et al. [22], Xu et al. [23], Valikhani et al. [24] and Gebel et al. [25].

The above literature review shows that in most model updating studies for OWTs, soil–structure interaction modelling is considered by a lumped stiffness matrix at the mudline, but the effect of scour, which probably has a high impact on frequencies and mode shapes, is not considered. Moreover, damping modelling parameters which could highly influence vibration amplitudes are seldomly taken as the parameters to be updated from measured data. In the present study, model parameters are updated by matching the modal properties identified from the long-term in situ test data on a 5.5 MW OWT, with a special focus on scour depth and damping. This paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, the FDD technique used to identify modal properties is introduced, and the Bayesian model updating frame is also introduced. Section 3 describes the details of the measurement campaign and modal identification results. Section 4 gives the settings and results of model updating. Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Methodology

2.1. Modal Identification Method

This study employs a widely used modal identification method, frequency-domain decomposition [7,26], to obtain the OWT’s modal properties, including natural frequencies, damping ratios and vibration mode shapes. FDD is an output-only identification technique and deals with the power spectral density (PSD) matrix of the measured signal. The output PSD matrix can be related to the input PSD matrix by

where is the FRF matrix, and the superscripts and denote the transpose and complex conjugate, respectively. The FRF can be written in a typical partial fraction form, using the Heaviside partial fraction theorem and assuming that the input is stochastic with a zero-mean white-noise distribution. The output PSD can also be related to the modal properties by

where is the set of modes that contribute to the frequency , is the mode shape, is the scaling factor, is the pole and is the damped natural frequency of the mode. At each discrete frequency, the PSD matrix can be decomposed into singular values and vectors:

where the matrix is an orthogonal matrix containing the singular vectors, and is a diagonal matrix collecting the singular values. Assuming small damping, the singular values of the PSD matrix are auto-spectral density functions of single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) systems that have the same frequency and damping as the modes of the examined structure. Thus, at a specific frequency, the contribution of each mode to the total response becomes evident and the system is decomposed to SDOF auto-spectral density functions. The dominant mode in each frequency appears at the first singular value. An estimate of the mode shape is the first singular vector that corresponds to a peak in the spectrum given by the maximum singular value. The auto-power spectral density function for each mode is then identified around this peak by estimating the modal assurance criterion (MAC) value of the mode shape estimate with the singular values for the frequencies around the peak.

The SDOF auto-spectral density functions are transferred back to the time domain through an inverse fast Fourier transform, resulting in autocorrelation functions for each mode. The logarithmic decrement is given through observation of all the extremes of the correlation function. Considering the ratio of the height of the first peak of the autocorrelation function with an arbitrary peak later in time, the solution to the equation of motion for an under-damped single-degree-of-freedom system is derived. Taking the natural logarithm on both sides of the equation, the expression for the logarithmic decrement is given. By fitting a linear curve to the data, the regression coefficient gives the slope of the line, which corresponds to the damping ratio . The natural frequencies are identified from the peaks of the singular values of the decomposed spectral density matrix.

2.2. Model Updating Based on Bayesian Inference Frame

This section briefly introduces a Bayesian inference frame which enables the finite element models to be updated given the measured modal properties [27]. In this inference frame, the observed data are the modal properties including the natural frequencies, damping ratios and mode shapes identified from the collected acceleration data. An observation vector collects the modal properties, and the parameters to be predicted are collected in a parameter vector which will be introduced in Section 4.1. Let denote the modal property vector given a series of proposed parameters . In the Bayesian inference frame, the posterior Probability Density Function (PDF) of the parameters is

where is the prior PDF, and is the likelihood that evaluates the plausibility of given the parameters . can be obtained by

where is the overall variance corresponding to the sum of measurement error and modelling error, and is the covariance matrix that collects . The probability of the observation can be treated as a normalizing constant. Furthermore, in the prior model, the model parameters can be independent random variables fitting to normal distributions. Therefore, the prior probability density for parameters is

where is the variance of the prior parameters and a diagonal variance matrix collects . is the mean value of the prior parameters, and is the number of parameters. Finally, the posterior distribution is proportional to . The posterior PDF narrows the parameter probability distribution compared to the prior PDF, so the updated model with this narrowed distribution can be regarded as the identified results. The parameter with the highest posterior probability density is the optimal parameter.

The Metropolis–Hastings (MH) algorithm, a type of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm, is used to generate the posterior PDFs of parameters. The MH algorithm is a method to simulate the sampling process, in which the sampling steps are incorporated in the Markov chain. The ultimate stationary state of the Markov chain corresponds to the target posterior distribution. At each step, a proposed parameter vector sample is randomly generated under the normal distribution assumption. Then, a reject–accept trigger selects the sample with a larger probability density compared to the initial probability density of the parameter and rejects the sample with a smaller probability density. The accepted parameters are treated as the means of updated prior distributions and the accepted probability density as the denominator in the acceptance ratio for the next step. This updating mechanism can speed up the convergence. Through the above iterations, the accepted parameters and corresponding probability densities are used to form the posterior PDFs of parameters given the measured PSDs, in which the most probable parameters are regarded as the identification results.

3. Measurement Campaign

3.1. Description

A measurement campaign was carried out in the Bi Qing Wan Offshore Wind Farm, which is located in Zhuhai, Guangdong, China. All wind turbines in this wind farm are supported by a monopile, and the sea depth is from 11.9 m to 20.9 m. One OWT with a power capacity of 5.5 MW was selected as the target to test the capability of the developed model updating technique. The basic properties of the 5.5 MW OWT are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic properties of the 5.5 MW OWT.

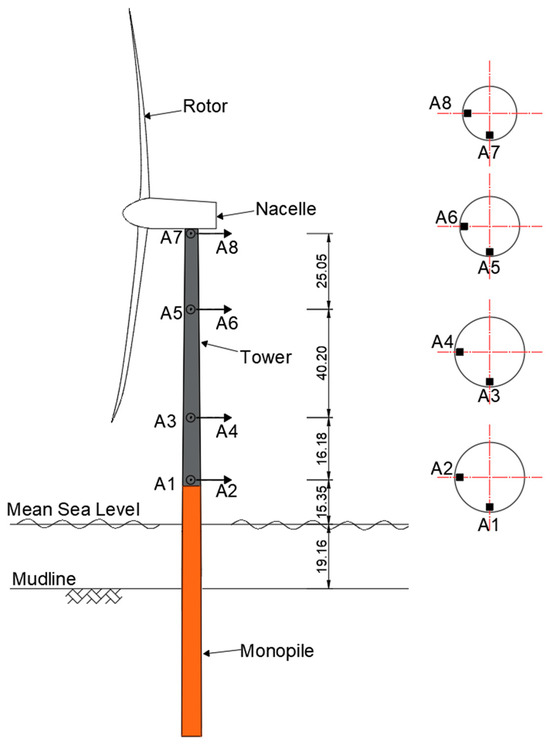

Eight accelerometers were installed at four different heights on the OWT, with the lowest installation position just at the top of the transition piece, and the highest accelerometers on the platform just below the nacelle. These four installation positions are marked as Level 1 to Level 4 from the lowest station to the highest station. The schematic of the OWT and the arrangement of the sensor system is shown in Figure 1. These accelerometers have a sensitivity of 0.3 V/(m·s−2) and a measurement range up to 20 m/s2. The sampling rate was set at 50 Hz, which adequately covers the frequency content of the structural responses. Turbine operational parameters, including yaw angles, blade pitch angles and power production, were simultaneously obtained from the SCADA system at a sampling rate of 1 Hz.

Figure 1.

Schematic of offshore wind turbine and sensor arrangement (length unit: m).

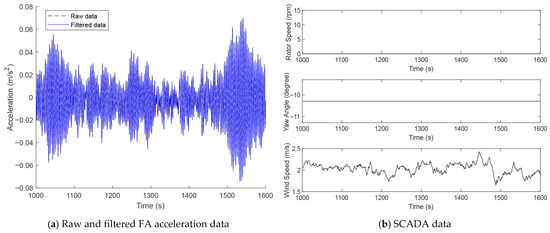

Based on the SCADA data, the acceleration data were converted to fore–aft (FA) and side–side (SS) accelerations considering the yaw angle variations. In this study, only acceleration data in parked conditions are considered, and the dynamic characteristics in the FA and SS directions are usually close as the effect of rotor rotation is omitted. Therefore, in the following sections, only the acceleration data in the FA direction is processed, and only the modal properties of related parameters in this direction are discussed. The raw data directly from the accelerometers were filtered by applying a lowpass filter with a cutting frequency of 5 Hz. The Matlab function “lowpass” was used to complete lowpass filtering. The representative 10 min raw and filtered FA acceleration data are plotted in Figure 2a, showing that the data filtering is reasonable as the time-series curve shape of the filtered data is maintained compared to that of the raw data. Figure 2b shows the corresponding SCADA data including the rotor rotation speed, yaw angle and instantaneous wind speed. The unchanged rotor speed and yaw angle indicate that the OWT is parked at low speeds around 2 m/s.

Figure 2.

Representative acceleration data collected at the highest platform and SCADA data.

3.2. Modal Identification Results

Although the accelerations were continuously collected for both operational and parked conditions, only a set of selected 10 min accelerations collected in September 2024 from the parked OWT under low wind speed (below the cut-in wind speed 3 m/s) was selected as the input data for modal identification. This is because when the OWT is in operation, the collected accelerations are strongly influenced by the harmonics caused by rotor rotation, and it is hard to use classic modal identification techniques to eliminate the effect of harmonics and correctly obtain modal properties.

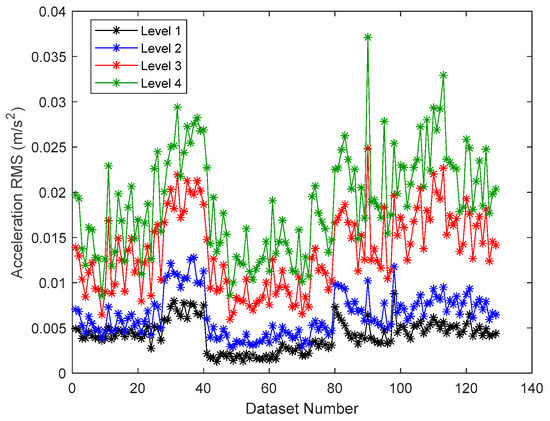

The natural frequencies, damping ratios and mode shapes of the first two bending modes in the FA directions were identified using FDD for each dataset. A total of 129 groups of 10-min datasets were processed to form the probability distributions of the identified modal properties. Figure 3 presents the root mean square (RMS) values of all the 10 min datasets. The acceleration RMS values range from 0.005 m/s2 to 0.037 m/s2, and RMS value amplitudes clearly increase from the lowest level to the highest level.

Figure 3.

Acceleration RMS values from the 129 datasets.

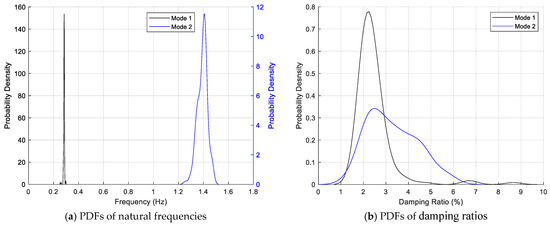

The identified modal properties can be represented in a probabilistic way by calculating their PDFs. The PDFs of the first and second natural frequencies are shown in Figure 4a, showing that the natural frequencies of the first two modes are around 0.285 Hz and 1.4 Hz, respectively. The frequency bandwidths associated with high probability density are quite narrow, meaning that the fluctuations of the first two frequencies are relatively low, especially for the first natural frequency.

Figure 4.

Probability distribution of identified natural frequencies.

On the other hand, the fluctuations of the damping ratios of the first two modes are relatively high, as shown in Figure 4b. The probability density of the damping ratio of the first mode is generally high when the damping ratio is between 1.5% and 3%, and it reaches its peak value when the damping ratio is around 2.2%. The identified damping ratio of the second mode is much more scattered, as its PDF is much flatter. The identified damping ratio of the second mode can vary from 1% to 6% with an average value around 3.2%. The above identified damping ratios generally agree with the damping values reported in the literature [28]. The damping identification results reveal that classic modal identification techniques such as FDD can lead to very scattered identified damping values due to limitations of the identification technique and a complex ocean environment that induces various external loads on the OWT structure.

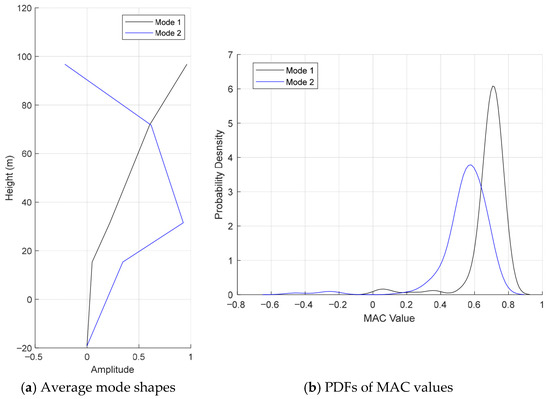

Furthermore, as shown in Figure 5a, the identified first and second mode shapes have the typical shapes of the first and second bending modes of a cantilever. The identified mode shapes only contain five nodes. The node at the bottom is at the mudline where the monopile is assumed to be restricted by soil. Practically, the amplitude of the mode shape at the bottom node is not zero, but this amplitude cannot be determined as no sensor is located at this position. Here, the mode shape amplitude at the bottom node is assumed to be zero for simplicity. The above four nodes correspond to the four stations where the accelerometers are installed. The mode shape coefficients for one mode are normalized by the largest value. It should be noted that the mode shapes plotted in Figure 5a are “averaged mode shapes” in which all the mode amplitudes are obtained by averaging all the values identified from different 10 min datasets. Using the averaged mode shapes as the reference mode shapes, the MAC values of other identified mode shapes from the datasets were also computed, and the PDFs of these MAC values are plotted in Figure 5b. It shows that the average MAC value of the first mode (around 0.7) is closer to 1 compared to that of the second mode (around 0.5). Meanwhile, the PDF of the MAC value of the first mode shape is more centralized than that of the second mode shape. This means that the identified amplitudes of the first mode shape are much less scattered than those of the second mode shape.

Figure 5.

Identified average mode shapes and MAC PDFs.

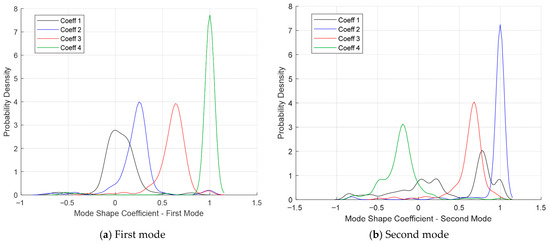

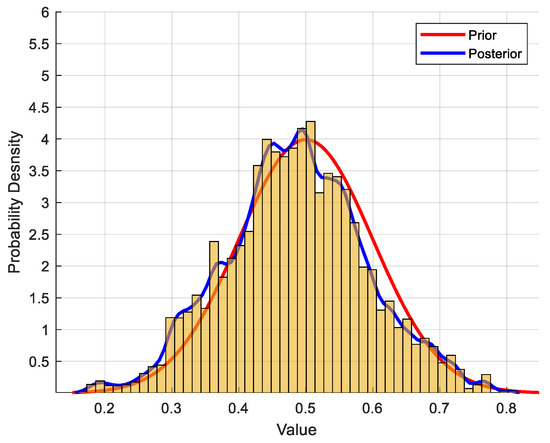

To further explore the quality of mode shape identification, the PDFs of all the identified mode shape coefficients of the first and second modes are plotted in Figure 6. For simplicity, we introduce , which denotes the mode shape coefficient of the mode. Figure 6a shows that the PDF of is much more centred around its mean than the other three PDFs, and the peaks of the PDF curves of and are slightly higher than that of . The mean values of the four mode shape coefficients of the first mode are 0.05, 0.22, 0.60 and 0.96, respectively, and the corresponding standard deviations are 0.19, 0.22, 0.16 and 0.23. On the other hand, Figure 6b demonstrates that for the second mode, the PDF curve of the second coefficient is much sharper than those of the other three coefficients. And the several peaks observed in the PDF of show that the corresponding identified values are quite scattered. The mean values of the four mode shape coefficients of the second mode are 0.34, 0.93, 0.62 and −0.21, respectively, and the corresponding standard deviations are 0.53, 0.29, 0.22 and 0.24. Comparing the identified PDFs and statistical properties of the mode shape coefficients, the identification results for and are the best as their PDFs all peak around one and have narrow distributions, while the identification result for is the worst. The identified results of the other mode shape coefficients have similar quality. However, as normalized mode shape coefficients have values from −1 to 1, the identification results for all the mode shape coefficients are generally poor as all the standard deviations are relatively large.

Figure 6.

PDFs of identified mode shape coefficients.

4. Model Updating

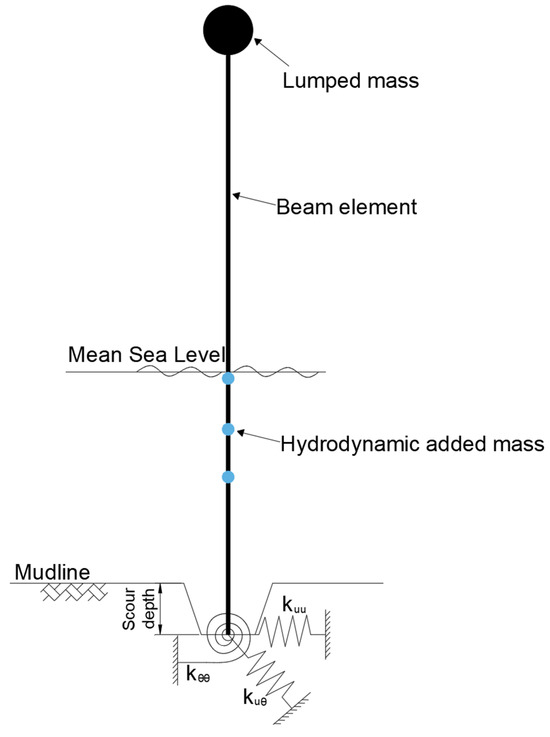

4.1. Finite Element Model and Parameters to Be Updated

The FE model of the OWT to be updated is established in MATLAB. This model contains a flexible support structure and a rotor–nacelle assembly (RNA) and considers the soil–structure interaction, as shown in Figure 7. The support structure, including a tower and a monopile, is modelled by one-dimensional Euler–Bernoulli beam elements. In this paper, only the measured accelerations and modal properties of the OWT support structures in the FA direction are considered. This is because for parked OWTs, normally, the dynamic properties do not vary greatly between the FA and SS directions, and a simplified model with less DOFs can accelerate the model updating process. The tower is divided into 44 beam elements, and the monopile between the mudline and the mean sea level (MSL) is divided into 10 beam elements. Each element node has two degrees of freedom (DOFs) corresponding to translational and rotational motions. As the acceleration measurements were not carried out for the blades, the blades are not explicitly modelled, and the RNA is simplified to a lumped mass located at the top of the tower. Then, the equation of motion of the OWT system can be formed, which is written as

where , and are the mass, damping and stiffness matrices, respectively, is the displacement vector, and is the external force vector.

Figure 7.

Schematic of OWT finite element model.

A convergence test shows that the deviations of the first and second natural frequencies are less than 0.1% when the beam element number increases to 100, indicating that a total of 54 beam elements is sufficient. Specifically, the interaction between the sea water and the part of the monopile immersed in the sea water leads to hydrodynamic added mass. To account for the effect of hydrodynamic added mass on the dynamic properties of the OWT, a hydrodynamic added mass coefficient , which measures how much water interacts with the monopile, is introduced as a parameter to be updated. In practice, the added mass coefficients can vary along the depth of the monopile, but here, only one added mass coefficient is introduced to represent the overall water added mass effect. The coefficient is defined as shown below. The inertia force caused by hydrodynamic added mass on the monopile can be expressed by

where and are the vectors collecting the diameters and accelerations of the monopile immersed in sea water, respectively, and is the density of sea water. In the finite element model, the hydrodynamic added mass is considered by directly amplifying the mass matrix.

Scour can significantly influence the dynamic properties of the OWT [29,30], but in the measurement campaign, no equipment was used to detect the scour pit. To consider the effect of scour, scour depth, denoted by , is assumed to be one of the parameters to be updated. As a result, the length of the beam element connected to the node that represents the lowest position of the scour pit changes with .

The part of the monopile below the scour pit is not modelled, since the effect of soil–structure interaction is considered by a lumped stiffness matrix defined at the lowest node of the monopile. The definition of the stiffness coefficients in the lumped matrix follows the method described in [31,32]. This method assumes a stiff monopile embedded in a homogeneous soil layer, and the lateral stiffness , rotational stiffness and cross-coupling stiffness are determined by

where is the length of the steel monopile embedded in soil; is a coefficient of the subgrade reaction constant with depth. The total length of the steel monopile is fixed, but the embedment length changes with . is taken as a parameter to be updated. It should be noted that estimated here only represents the average subgrade reaction constant, as in practice, the mechanical properties of the soil layers can vary significantly along the monopile embedment depth.

Given the above definitions, the mass matrix and stiffness matrix in the equation of motion of the OWT structure can be obtained using the material properties. However, the damping properties are still required to be defined. Here, the damping effect is represented by the Rayleigh damping, representing the total damping of the OWT. This damping definition mainly considers the effect of soil damping and structural damping, but the slight contribution of aerodynamic and hydrodynamic damping due to the interaction between wind, water and the structure is also automatically considered. The Rayleigh mass and stiffness coefficients and are defined as two parameters to be updated. In this way, the damping matrix of the system can be calculated by

The prior distributions of the aforementioned five parameters to be updated are all assumed to be normal. The selection of these five parameters for OWT model updating is justified by their direct influences on dynamic characteristics of OWTs and the selected monitoring data. First, apparent scour can be frequently observed after OWTs are in service for more than 2 years, and the scour depth () significantly alters OWT foundations’ boundary conditions, directly impacting system natural frequencies. Second, the average subgrade reaction constant () defines soil–structure interaction stiffness, which is a major cause of modelling inaccuracy. Third, the water added mass coefficient () critically affects the submerged substructure’s inertial properties, influencing global mass and dynamics, and its effect is very hard to model accurately. Finally, the Rayleigh mass and stiffness coefficients () are chosen as they directly control the system’s damping ratio across frequency modes, which are often poorly characterized in initial models but significantly influence vibration amplitudes. In this study, only monitoring data collected in parked conditions were selected, and modelling parameters associated with aerodynamic damping caused by the interaction between air and the rotor were not independently considered. This is because aerodynamic damping is only considerable when OWTs are operating.

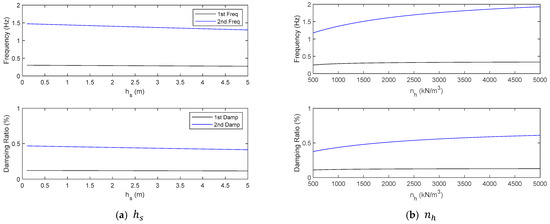

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Parameters

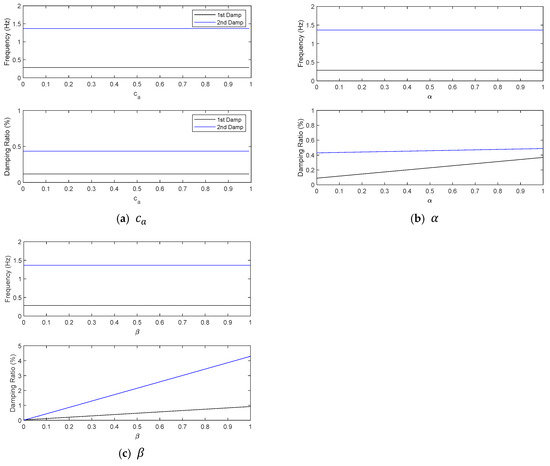

A sensitivity analysis of the five selected parameters was conducted to investigate the influence of these parameters on the OWT’s modal properties. In the sensitivity analysis, an initial parameter vector was first defined by . With other parameters kept constant, the parameter to be investigated was made to vary in a range, and the corresponding natural frequencies, damping ratios and mode coefficients for the first and second modes were computed. As shown in Figure 8a, an increase in slightly influences the natural frequency and damping ratio of the first mode. The first natural frequency is around 0.29 Hz, and a slight decrease from 0.302 Hz to 0.274 Hz is found when increases from nearly 0 to 5 m. But apparent decreases in the second natural frequency, from 1.472 Hz to 1.301 Hz, can be seen when increases. Similarly, also has smaller influences on the first mode’s frequency and damping ratio compared to the second mode, as shown in Figure 8b.

Figure 8.

Sensitivity of scour depth and coefficient of subgrade reaction constant to natural frequencies and damping ratios.

However, from the sensitivity analysis results for shown in Figure 9a, the water added parameter has an insignificant impact on the natural frequencies and damping ratios. Figure 9b demonstrates that the Rayleigh mass coefficient significantly influences the damping ratios, but changes in this coefficient hardly influence natural frequencies. Similar results were obtained for the Rayleigh stiffness coefficient , as shown in Figure 9c.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity of water added mass coefficient and Rayleigh mass and stiffness coefficients and to natural frequencies and damping ratios.

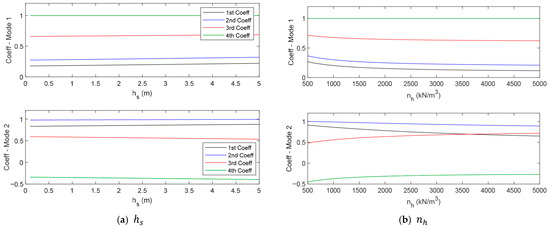

Moreover, the influences of the five selected parameters on the mode shape coefficients were also investigated. Figure 10 shows the sensitivity analysis results of the mode shape coefficients in terms of and . Figure 10a shows that in the selected range of , mode shape coefficients of the first and second modes do not change significantly with the change in . Small slopes can be seen for the first and second coefficients of the first mode shape, as well and the third and fourth coefficients of the second mode shape. However, as shown in Figure 10b, many observable changes in all the coefficients can be found when increases from 500 to 2000 kN/m3. And when is larger than 2000 kN/m3, mode shape coefficients become less sensitive to the changes in .

Figure 10.

Sensitivity of scour depth and coefficient of subgrade reaction constant to mode shape coefficients.

Considering the identified modal properties from the measured data, the means and standard deviations of the five selected parameters’ prior distributions are listed in Table 2. The selections of the prior distributions were based on sensitivity analysis in which the influence of the parameters on the modal properties of the OWT system was checked.

Table 2.

Prior distributions of parameters.

4.3. Parameter Updating Results

Given the prior distributions of the parameters to be updated and the PDFs of the modal properties, the model updating was conducted by the Bayesian inference frame. To study the uniqueness of the updating results, four independent parameter predictions, marked as P1~P4, were made with different starting values for the MCMC chains. For P1, P2 and P3, all five parameters were assumed to be unknown and updated in the Bayesian inference frame. In P4, the scour depth, marked as , was kept at 2 metres, and only the other four parameters were updated. The iteration number in the Bayesian inference frame for each prediction was selected to be 4 million to ensure the accuracy of inferred posterior distributions. As the sampling size is quite large, in the beginning of the analysis, burn-in length is omitted, and this is expected not to impact the obtained posterior distributions. The mean values and standard deviations of the parameters after updating are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mean values and standard deviations of parameters after updating.

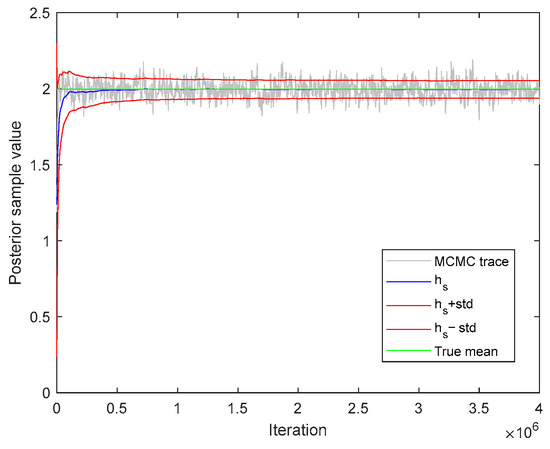

Here, only the model updating process and results of P1 are presented in detail. In Figure 11, the sampling process of is plotted, from which a typical convergence process to the true mean value of 1.99 m can be observed. For other parameters, the MCMC sampling also makes them converge around stable mean values. For the sake of brevity, more detailed results for other parameters are not presented.

Figure 11.

Convergence history of .

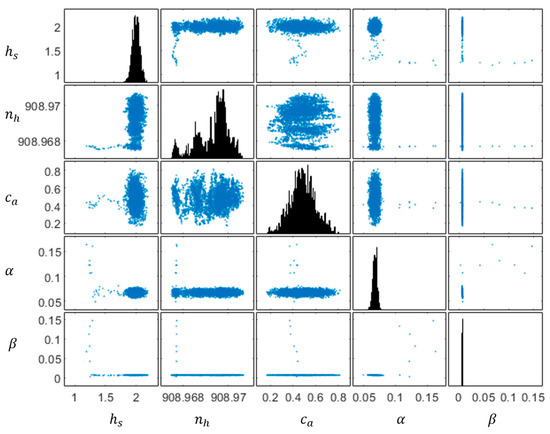

Moreover, Figure 12 demonstrates a scatter plot matrix, in which the sample clusters of all parameters are presented. This scatter plot matrix shows that the proposed Bayesian updating frame can generally update the selected parameters effectively.

Figure 12.

Scatter plot matrix of the updated parameters using the Bayesian frame.

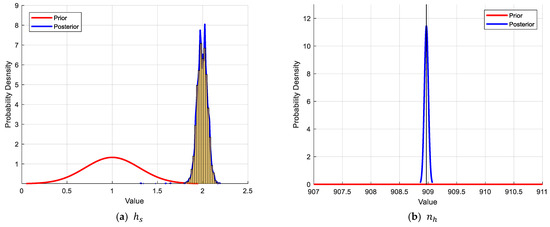

The parameter updating results for , , and in P1 are shown representatively in Figure 13. It shows that the posterior distributions of these four parameters apparently differ from the corresponding prior distributions. The initial mean value and standard deviation of are 1 m and 0.3 m, respectively, corresponding to a relatively flat PDF curve, which is plotted in red in Figure 13a. After updating, the posterior PDF of becomes much narrower around its mean value of 1.99 m with a standard deviation of 0.06 m, which is plotted in blue in Figure 13a. In Figure 13b, the prior distribution of is much flatter than its posterior distribution, meaning that model updating makes the value of distributed in a very narrow range around 909 kN/m3. Similarly, the prior distribution of is centred at 0.2 and has a relatively large standard deviation of 0.05. The updated distribution of becomes much sharper with a mean value of 0.07 and a standard deviation of 3.1 × 10−3. For the Rayleigh stiffness coefficient , its updated distribution also significantly differs from the assumed prior distributions.

Figure 13.

Prior and posterior distributions of representative parameters.

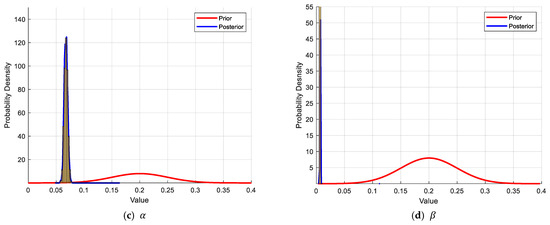

However, for the water added mass coefficient , the updated distribution is quite close to its prior distribution, as shown in Figure 14. This means that the added mass coefficient cannot be effectively updated. Also, it implies that the change in the water added mass coefficient seldomly impacts the modal properties, which has been confirmed by parameter sensitivity analysis.

Figure 14.

Prior and posterior distributions of .

Comparing the parameter updating results in P1 to P3, it can be seen from Table 2 that the updated distributions of , and are almost identical, but those of and are clearly different. The mean values of are 1.99 m, 3.47 m and 2.65 m, while the mean values of are 909 kN/m3, 1088 kN/m3 and 984 kN/m3, for P1 to P3, respectively. This means that the combination of updated and is not unique in the present model updating problem. Comparing the updated parameters in P4 and P1 shows that when in P4 is preset to the optimal value given in P1, the updated value of in P4 is eventually very close to its optimal counterpart in P1. Furthermore, in the updated combinations of and , a larger is always bonded with a smaller . This observation demonstrates that the modal properties of the OWT significantly depend on the combination of the scour depth and foundation stiffness coefficient, but this combination cannot be uniquely determined given only the identified modal properties. In practice, scour monitoring could be useful to solve the non-uniqueness problem in model updating.

The modal properties of the OWT system with the updated parameters were calculated and compared to the identified values, as shown in Table 4. In Table 4, the identified modal properties are in the line marked by “Obs”, while the modal properties obtained with the parameters’ mean values in the prior distributions are in the line marked by “Initial”. The predicted modal properties with the updated parameters in the four predictions are in the lines marked by “P1” to “P4”. The table shows that the predicted model properties with the updated parameters are apparently different from the initial values. Taking P1 as an example, the initial first and second natural frequencies are altered from 0.297 Hz and 1.440 Hz to 0.287 Hz and 1.371 Hz, respectively, while the damping ratios for the first and second modes are altered from 24.0% and 91.9% to 2.48% and 3.28%, respectively. The predicted modal properties in P1 to P4 are generally close. Moreover, comparing the modal properties marked by “P1” to “P4” and those marked by “Obs”, it is confirmed that the modal properties calculated with the updated parameters become much closer to the identified values, especially for the natural frequencies and damping ratios of the first and second modes. This means that the updating process is effective. The predicted mode shape coefficients in P1 to P4 are almost identical and generally like those identified, but apparent differences are found in the first mode shape coefficients for both the first and second vibration modes, i.e., and . The relative errors between the predicted and identified values of these two coefficients can be up to 300%. From the sensitivity analysis for the mode shape coefficients shown in Figure 10, only changing can slightly alter and . But the updated distribution of plotted in Figure 13b shows that the range of is very narrow. This implies that the selection of parameters to be updated is not robust enough so that the difference in the predicted and identified mode shape coefficients cannot be minimized. Better updating results could be obtained with more parameters selected, especially for those parameters which have more influence on mode shapes.

Table 4.

Observed and predicted modal properties.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, a comprehensive model updating study for a 5.5 MW OWT with measured acceleration data is introduced. The modal identification technique FDD was applied to measured data at four platforms, and the modal properties was extracted. A finite element model was then set up in MATLAB, and five parameters in the model were selected to be updated. After assuming the prior distributions of the five parameters, the posterior distributions given the extracted modal properties were obtained iteratively by a Bayesian inference frame. Some conclusions can be drawn from this model updating study:

- (1)

- The modal identification results show that the uncertainties in identified natural frequencies are relatively low, especially for the first natural frequency. However, the identified damping ratios and mode shape coefficients are more scattered, indicating the limitation of the identification technique in dealing with vibration signals collected in a complex ocean environment.

- (2)

- The finite element model with the updated parameters has close modal properties compared to those identified, especially for natural frequencies and damping ratios. The errors between the predicted and measured natural frequencies and damping ratios are less than 2%. This confirms that the model updating process is generally successful. However, the updating results for some of the mode shape coefficients are very poor, with relative errors up to 300%, indicating that the selection of parameters to be updated is not robust enough for mode shape coefficient updating.

- (3)

- Apart from other parameters, the added mass coefficient cannot be effectively updated, which implies that the change in water added mass seldomly impacts the modal properties.

- (4)

- The model updating result is not unique, which is confirmed by the fact that the combination of the scour depth and foundation stiffness coefficient cannot be uniquely determined given only the identified modal properties. It is suggested that scour monitoring could assist in obtaining a better model updating result.

- (5)

- With the five selected parameters to be updated, good approximation can be obtained for natural frequencies and damping ratios, but the predicted first mode shape coefficients for the first and second modes are still away from those identified. This implies that the updating results could be improved if a more robust set of parameters is chosen.

To enhance the robustness of the Bayesian updating model, future efforts can be made in three key directions: first, expanding the parameter set to better represent the system’s complexity; second, incorporating independent scour depth measurements from periodic sonar or underwater scans to constrain the inverse problem; and third, analyzing higher-order modal responses, which are sensitive to the distinct effects of scour and stiffness degradation. This integrated strategy is pivotal for improving the parameter estimation and the model’s reliability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.; Methodology, C.C.; Software, C.C.; Validation, J.D. and M.R.; Formal analysis, C.Y.; Investigation, J.D.; Resources, M.R.; Data curation, C.L.; Writing—original draft, C.Y.; Writing—review and editing, C.C.; Project administration, X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (No. 2022B0101100001), the Young Talent Support Project of Guangzhou Association for Science and Technology (QT-2005-028), the Joint Fund of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U24A20177) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2023JJ70001).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to commercial restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Chi Yu, Jiayi Deng and Mumin Rao were employed by the company Guangdong Energy Group Science and Technology Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| damping matrices | |

| hydrodynamic added mass coefficient | |

| diameter vector of the monopile | |

| external force vector | |

| input power spectral density matrix | |

| output power spectral density matrix | |

| frequency response function matrix | |

| scour depth | |

| stiffness matrix | |

| lateral soil stiffness | |

| rotational soil stiffness | |

| cross-coupling soil stiffness | |

| length of the monopile embedded in soil | |

| mass matric | |

| average subgrade reaction constant | |

| number of parameters | |

| evidence or marginal likelihood | |

| prior probability density function | |

| conditional probability of given data | |

| conditional probability given | |

| displacement vector | |

| Greek Symbols | |

| Rayleigh mass coefficient | |

| Rayleigh stiffness coefficient | |

| variance of error | |

| damping ratio | |

| pole of the mode | |

| parameter vector to be identified | |

| density of sea water | |

| observed data vector | |

| the mode shape of the mode | |

| damped natural frequency of the mode | |

References

- Ciang, C.C.; Lee, J.-R.; Bang, H.-J. Structural health monitoring for a wind turbine system: A review of damage detection methods. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 122001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Cai, O.; Dong, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhao, Y. Health monitoring and safety evaluation of the offshore wind turbine structure: A review and discussion of future development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Luengo, M.; Kolios, A.; Wang, L. Structural health monitoring of offshore wind turbines: A review through the Statistical Pattern Recognition Paradigm. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branlard, E.; Jonkman, J.; Brown, C.; Zhang, J. A digital twin solution for floating offshore wind turbines validated using a full-scale prototype. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Y. Development of a modified stochastic subspace identification method for rapid structural assessment of in-service utility-scale wind turbine towers. Wind Energy 2017, 20, 1687–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Lian, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, T.; Zhao, Y. Structural vibration monitoring and operational modal analysis of off-shore wind turbine structure. Ocean Eng. 2018, 150, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukoura, C.; Natarajan, A.; Vesth, A. Identification of support structure damping of a full scale offshore wind turbine in normal operation. Renew. Energy 2015, 81, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.-H.; Thöns, S.; Rohrmann, R.G.; Said, S.; Rücker, W. Vibration-based structural health monitoring of a wind turbine system Part II: Environmental/operational effects on dynamic properties. Eng. Struct. 2015, 89, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Mehr, N.P.; Moaveni, B.; Hines, E.; Ebrahimian, H.; Bajric, A. One year monitoring of an offshore wind turbine: Variability of modal parameters to ambient and operational conditions. Eng. Struct. 2023, 297, 117022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Duffour, P.; Dai, K.; Wang, Y.; Fromme, P. Identification of aerodynamic damping matrix for operating wind turbines. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 154, 107568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, S.; Hu, S.-L.J.; Li, H.-J. Using incomplete complex modes for model updating of monopiled offshore wind turbines. Renew. Energy 2022, 181, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, K.; Gebhardt, C.G.; Rolfes, R. A two-step approach to damage localization at supporting structures of offshore wind turbines. Struct. Health Monit. 2018, 17, 1313–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, R.A.; Chatzis, M.N.; Kuleli, M.; Anderson, E.F.; Byrne, B.W. Monopile foundation stiffness estimation of an instrumented offshore wind turbine through model updating. Struct. Contr. Health Monit. 2023, 2023, 4474809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamizifar, M.; Mosayebi, M.; Ziaei-Rad, S. Optimal sensor placement and model updating applied to the operational modal analysis of a nonuniform wind turbine tower. Mech. Sci. 2022, 13, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador, S.D.R.; Rasmussen, S.; Brincker, R.; Rex, S.; Skog, M.; Gjødvad, J.F. Vibration-based FE-model updating for strain history estimation of a 3MW offshore wind turbine tower. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2647, 182035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Nikitas, G.; Zhang, T.; Han, Q.; Chryssanthopoulos, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Wang, Y. Support condition monitoring of offshore wind turbines using model updating techniques. Struct. Health Monit. 2020, 19, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Xu, Y.; Shen, T.; Wang, Y.; Bhattacharya, S. Support condition monitoring of monopile-supported offshore wind turbines in layered soil based on model updating. Mar. Struct. 2023, 87, 103342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyn, D.; Smolka, U.; Tygesen, U.T.; Ulriksen, M.D.; Sørensen, J.D. Data-driven model updating of an offshore wind jacket substructure. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 104, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Kato, B.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Y. Support condition identification for monopile-supported offshore wind turbines based on time domain model updating. Mar. Struct. 2025, 99, 103709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabiyan, M.-S.; Khoshnoudian, F.; Moaveni, B.; Ebrahimian, H. Mechanics-based model updating for identification and virtual sensing of an offshore wind turbine using sparse measurements. Struct. Contr. Health Monit. 2021, 28, e2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, B.; Mehrjoo, A.; Moaveni, B.; McAdam, R.; Rüdinger, F.; Hines, E. System identification and finite element model updating of a 6 MW offshore wind turbine using vibrational response measurements. Renew. Energy 2023, 219, 11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Moaveni, B.; Ebrahimian, H.; Hines, E.; Bajric, A. Joint parameter-input estimation for digital twinning of the Block Island wind turbine using output-only measurements. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 198, 110425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Fan, S.; Xu, Q. Using Bayesian updating for monopile offshore wind turbines monitoring. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280, 114801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valikhani, M.; Nabiyan, M.; Song, M.; Jahangiri, V.; Ebrahimian, H.; Moaveni, B. Bayesian finite element model inversion of offshore wind turbine structures for joint parameter-load estimation. Ocean Eng. 2024, 313, 119458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebel, J.; Rezaei, A.; Vemuri, A.; Liverud, K.V.; Daems, P.-J.; Matthys, J.J.; Sterckx, J.; Vratsinis, K.; Kestel, K.; Nejad, A.R.; et al. System identification of offshore wind turbines for model updating and validation using field measurements. Wind Energy Sci. Discuss. 2025, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brincker, R.; Zhang, L.; Andersen, P. Modal identification of output-only systems using frequency domain decomposition. Smart Mater. Struct. 2001, 10, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.L.; Feissel, P.; Antoni, J. A comprehensive Bayesian approach for model updating and quantification of modeling errors. Probab. Eng. Mech. 2011, 26, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Duffour, P. Modelling damping sources in monopile-supported offshore wind turbines. Wind Energy 2018, 21, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, N.; Yang, J.; Chen, C.; Zhu, R.; Hua, X. Effect of scour on the fatigue life of offshore wind turbines and its prevention through passive structural control. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Duffour, P.; Fromme, P. Scour influence on the fatigue life of operational monopile-supported offshore wind turbines. Wind Energy 2018, 21, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi-Alamouti, S.; Bahaari, M.-R.; Moradi, M. Natural frequency of offshore wind turbines on rigid and flexible monopiles in cohesionless soils with linear stiffness distribution. Appl. Ocean Res. 2017, 68, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Larsen, T.J.; Bredmose, H. Ultimate load analysis of a 10 MW offshore monopile wind turbine incorporating fully nonlinear irregular wave kinematics. Mar. Struct. 2021, 76, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).