Abstract

The first oil and gas well in the South Yellow Sea Basin was completed in 1961. In 1984, 2.45 tons of light oil were obtained from the Cenozoic strata. However, it remains the only large oil and gas basin in China’s offshore area without industrial oil and gas discoveries. Although the consensus is that the South Yellow Sea Basin is a foreland basin, and the oil and gas exploration prospects are promising, the research on the regional structure and the tectonic evolution of the foreland basin system is weak, which seriously hinders the process of industrial oil and gas discoveries. This paper reports the results of over 30 years of onshore and offshore investigations and well-seismic joint interpretation in the study area: for the first time, the mountains and basins formed by the collision of the North China and Yangtze plates were discovered in the geological survey of the northern islands of the South Yellow Sea Basin; the C-type eclogite chronology of Qianliyan Island, the characteristics of the foreland basins and intracontinental foreland basins around the South Yellow Sea, and the tectonic evolution characteristics and models of the basins were clarified. Through the zircon/phosphate fission track analysis of the deep black Jurassic strata in the Qianyuan S-2 well, it was revealed that the collision and subduction of the Pacific Plate against the Eurasian Plate since the Late Cretaceous–Paleogene led to large-scale uplift movements, and more than 3000 m of strata were eroded in the basin area. This is consistent with the multiple unconformities of E/N, K/N, and T2/N identified by well-seismic joint interpretation, and is also the main reason why oil and gas have been difficult to preserve in the South Yellow Sea Basin since the Middle Triassic–Jurassic. Deep prototype oil and gas exploration in the basin may be the preferred option for current oil and gas exploration deployment, which is conducive to achieving industrial oil and gas discoveries.

1. Introduction

Foreland basins, elongate and narrow depositional troughs situated between orogenic belts and stable cratons, are of significant interest to the petroleum industry owing to their substantial hydrocarbon reserves and prolific discovery history. The term “foreland” was first introduced by Suess in 1909, who defined it as the stable continental margin adjacent to an orogen, emphasizing the concept of tectonic material being transported from the hinterland toward the foreland [1]. Stille characterized the foreland as a rigid, non-Alpine deforming block [2]; Eardley based on field observations in the Alps, refined this definition by identifying the foreland as the stable continental region into which thrust systems propagate [3]. Dickinson within the framework of plate tectonics, established a classification scheme distinguishing between peripheral foreland basins—formed during continental collision—and retroact (or back-arc) foreland basins—associated with oceanic subduction zones—thereby providing a foundational framework for modern tectono-sedimentary analysis of foreland systems [4]. In 1995, AAPG Memoir 64 comprehensively addressed sequence stratigraphy in foreland basin settings, becoming a seminal reference in sedimentology and petroleum geoscience [5]. Subsequently, Giles formalized the concept of the “foreland basin system,” subdividing it into four distinct structural elements [6]: the wedge-top, foredeep, forebulge, and back-bulge, and elucidating the dynamic coupling between lithospheric loading and sedimentary response.

Globally, foreland basins are typically governed by a single tectonic cycle, characterized by relatively simple structural architectures and highly predictable patterns of hydrocarbon distribution. In contrast, the foreland basins in central and western China have undergone multiple phases of intracontinental tectonic superimposition, resulting in structurally complex and fragmented configurations, as well as more complicated hydrocarbon accumulation processes, thereby posing significantly greater challenges for petroleum exploration. Typical foreland basins, such as the Zagros and Alpine systems, are compared with those in central and western China, including the Kuqa and western Sichuan basins. The Zagros foreland basin, situated in the Iran-Iraq region, formed as a result of Neo-Tethyan oceanic retreat and the subsequent collision between the Arabian and Eurasian plates [7]. It is predominantly characterized by Mesozoic marine carbonate source rocks, hosts large-scale hydrocarbon accumulations with spatially concentrated distributions, and is structurally controlled by thrust-fold belts—features that collectively make it one of the most prolific hydrocarbon-bearing foreland basins globally [8]. The Alpine peripheral foreland basins represent classic examples, where Neogene molasse deposits preserve a detailed record of the tectonic evolution and progressive deformation of the Alpine orogen [9]. In contrast, the foreland basins in central and western China have experienced multiple phases of tectonic overprinting, particularly from interactions between the Tethyan and Pacific tectonic domains, resulting in highly fragmented basin architectures and complex, heterogeneous petroleum systems [10,11]. The Kuqa foreland basin, located south of the South Tianshan orogenic belt, exemplifies this complexity as a reactivated foreland system with intricate structural configurations. It contains ultra-deep Jurassic coal-measure source rocks, with reservoirs predominantly fracture-controlled at depth, contributing to its significant natural gas potential [12]. Similarly, the western Sichuan foreland basin features multiple effective reservoir-cap rock assemblages within the Xujiahe Formation, with hydrocarbon distribution governed by the interplay between the foredeep and thrust belt structures [13].

The South Yellow Sea foreland basin discussed in this study represents a distinct and exceptionally complex type, fundamentally different from previously described foreland basin systems. Its identification and geological validation not only provide critical insights for hydrocarbon exploration in the South Yellow Sea Basin but also justify sustained and intensified exploration efforts in this underexplored region. Future research should integrate analyses of deep crustal architecture, sedimentary dynamics, petroleum systems, and source rock characterization to guide targeted exploration strategies and enable breakthrough discoveries.

2. Background

The Indosinian Dabie–Sulu Orogenic belt in the central and eastern part of the Central China Orogenic Belt is the product of the collision between the North China and Yangtze plates [14,15], and it is also one of the earliest discovered ultra-high-pressure metamorphic belts in China and the largest in the world (Figure 1) [16]. Extensive research has been conducted on the lithology, mineralogy and chronology of the Dabie–Sulu ultra-high-pressure metamorphic rocks, especially eclogites. The P-T-t evolution trajectory of eclogites has been established in typical areas of the Dabie–Sulu Orogenic belt, revealing the cooling history and exposure mechanism of the ultra-high-pressure metamorphic rocks in this area: the protoliths of eclogites formed in the Neoproterozoic; ultra-high-pressure metamorphism occurred in the Triassic [17,18].

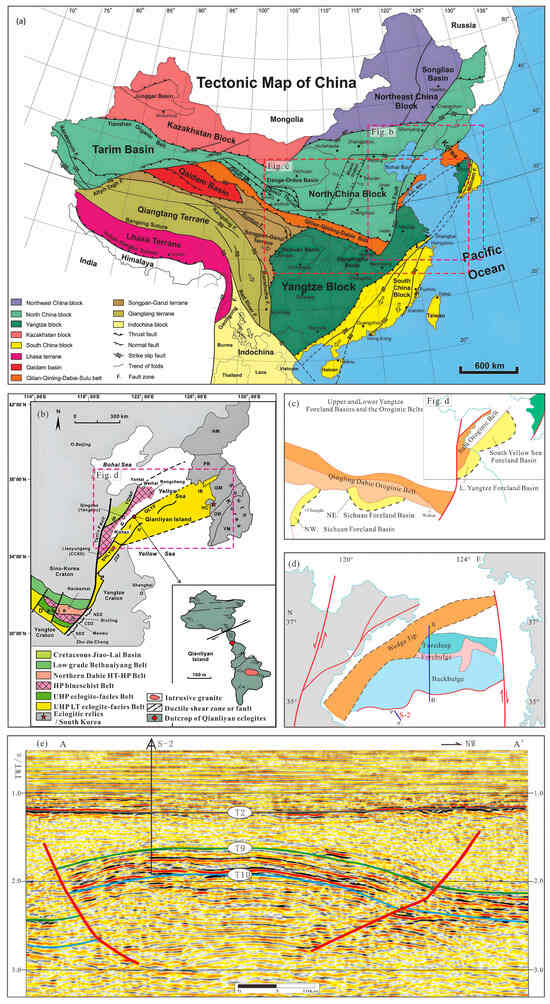

Figure 1.

Geotectonic map of China and location of study area (a). (b) The Dabei–Sulu–Jiaodong-North Korean high-pressure metamorphic belt and its eastward extension to the Korean Peninsula, the red box with the red five stars is the Thousand-Mile Rock Island, and the red dot in the middle of the island is the large profile of the oval-shaped C-type eclogite outcrop shown. (c) The Qinling–Dabie orogenic belt and the three foreland basins of the Upper and lower Yangtze regions, the location of the Sulu Orogenic belt; Location of the South Yellow Sea foreland basin; (d) The wedge-top, anterior abyss, anterior uplift and posterior uplift sedimentary zones of the South Yellow Sea anterior Basin, A-A’ and B-B’ are the positions of the seismic profiles; (e) S-2 well seismic interpretation of the seismic geological interface (A-A’).

In the context of tectonic evolution, the Korean Peninsula exhibits a significant connection with the North China Craton [19,20]. As a result, these two tectonic units are jointly referred to as the Central Asian Platform or the Central Asian Craton [21,22].

To date, numerous scholars have investigated the potential extension of the Dabie–Sulu Orogenic belt into the Korean Peninsula [23,24,25]. Hong Seong [26] identified Triassic eclogites. The Qianliyan Uplift is part of the Sulu high-to ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic belt [27,28]. Eclogites were discovered on Qianliyan Island [29], which is a crucial component of the Dabie–Sulu Orogenic belt. Given its eastern connection with the Korean Peninsula, Qianliyan Island occupies an important and distinctive tectonic position [30].

Extensive research has verified the close relationship between Qianliyan Island and its associated uplift and the South Yellow Sea Basin. It is widely accepted that during the Indosinian Movement, the collision between the North China Plate and the Yangtze Plate led to the formation of the Qinling–Dabie–Sulu Orogenic Belt. South of this orogenic belt, a curvilinear subsidence basin emerged and extended eastward into the sea, giving rise to the foreland basin in the northern part of the South Yellow Sea [31,32].

Nonetheless, there is a scarcity of research reports regarding the type, age, sedimentary characteristics, and tectonic evolution of this foreland basin. The existing research findings also show significant discrepancies. During the Late Jurassic to Cretaceous (J3-K) period, the northern part of the South Yellow Sea Basin was a Late Triassic to Early or Middle Jurassic foreland basin, which formed as a result of the adjacent continental margin bending and subsiding towards the collisional mountain chain. Some other researchers hold the view that the Early to Middle Jurassic was a foreland basin, and following the Pacific-related dynamic evolution from the Late Cretaceous to the Paleogene, it transformed into a faulted basin [33]. Alternatively, some consider it to be a strike-slip pull-apart basin [34,35,36]. The South Yellow Sea Basin is a multi-cycle superimposed sedimentary basin on the pre-Cambrian metamorphic basement of the Lower Yangtze Platform, with a northern foreland basin and a southern faulted basin during the Jurassic-Cretaceous period [32].

It has been widely recognized within the academic community that the South Yellow Sea Basin traverses six tectonic units across the North China Block, South China Block, and the Sulu Orogen [37,38]. The North China Block and South China Block give rise to the North Yellow Sea Basin in the north and the South Yellow Sea Basin in the south, with the Sulu–Lingjiang Orogenic Belt serving as the demarcation in the middle [38].

Within the South Yellow Sea Basin, the primary tectonic units arranged from north to south are the Qianliyan Uplift, the Northern Depression, the Central Uplift, the Southern Depression, and the Wushan Sand Uplift. Two primary negative tectonic units, namely the Northern Depression and the Southern Depression of the South Yellow Sea Basin, are identified from the Central Uplift. These negative tectonic regions are the depositional sites of Cambrian to Triassic marine strata, Mesozoic marine-continental alternating carbonate and clastic rocks, and Cenozoic continental sedimentary systems. Nevertheless, a significant portion of the area lacks the Middle and Upper Triassic and Lower Cretaceous deposits [39]. The Jurassic strata are predominantly distributed in the northeastern part of the basin [40,41,42,43].

The sedimentation of the main fault-controlled half-graben-type depression is a characteristic sedimentary structure in the South Yellow Sea Basin [42]. This sedimentary pattern is associated with the Indosinian orogeny of the Sulu Orogen and the erosion of the upper plate subduction zone [36]. The Triassic deposits mainly consist of marine carbonate rocks; the Jurassic is composed of red volcanic clastic rocks; the Cretaceous and Paleogene are characterized by continental clastic rocks; the Neogene to Lower Quaternary are fluvial deposits, and the Mesozoic deposits have undergone substantial deformation.

Well and seismic data suggest that the Cretaceous and Paleogene deposits are continental faulted-basin sand and mudstone deposits, which are solely found in depressions and not in uplifts or domes. Through an integrated interpretation of drilling data, seismic profile well-to-well correlation, regional tectonic movements, and relevant structural evolution data, the conclusion was derived that a substantial amount of Upper Triassic to Jurassic strata in the northern and northeastern parts of the Northern Depression.

From the 1970s to the present day, 27 wells have been drilled in the South Yellow Sea Basin by China National Offshore Oil Corporation and the Qingdao Institute of Marine Ge-ology, in collaboration with multiple research institutions in China. These wells have uncovered marine and continental sedimentary strata dating back to the Ordovician, along with 16 types of stratigraphic contacts, which represent the outcome of tectonic movements spanning hundreds of millions of years in the basin. However, these do not encompass the entirety of contact relationships among geological bodies within the basin. Instead, they specifically denote the stratigraphic contact relationships at 16 locations, as revealed by all drilled wells in the basin, including those identified through integrated well-seismic interpretation post-drilling, such as E/N, K/N, and T2/N [43]. The recently completed CSDP-2 well does not contain Jurassic rocks [44]. In May 2015, the mineralogical identification of C-type rutile eclogite was completed; in July 2015, the zircon SHRIMP U-Pb dating was carried out; in October, the zircon/phosphate fission track analysis of the S-2 well was finished, along with a high-precision well-seismic sequence stratigraphy joint interpretation.

3. Materials and Methods

The eclogite samples from the Triassic System were collected on Qianliyan Island in the South Yellow Sea (Figure 2 and Figure 3). About 20–30 sandstone and mudstone samples obtained from Well S-2 were analyzed. Interpretation and eclogite analysis of nearly 100 samples were conducted collaboratively at China University of Petroleum (East China), Shandong University of Science and Technology, and the Qingdao Institute of Marine Geology. Fission track samples were prepared and tested at the Fission Track and (U-Th)/He Laboratory of the University of Waikato, New Zealand. Radioactive isotope irradiation was performed at the University of Oregon Reactor, while mineral analysis was carried out at the University of Stuttgart using a CAMECA SX100 (CAMECA, Madison, WI, USA) electron microprobe under the following conditions: acceleration voltage of 15 kV and electron beam current of 20 nA. Natural minerals such as jadeite (Si), olivine (Mg), hematite (Fe), albite (Na, Al), rutile (Ti), siderite (Mn), and hornblende (K) served as internal standards. Zircon grains were conventionally crushed, floated, and electromagnetically separated, followed by selection under a binocular microscope based on satisfactory crystal morphology and transparency. Zircon target dating, cathodoluminescence imaging, and SHRIMP U-Pb dating were performed at the Beijing SHRIMP Center. The main ion beam current was O-2 with an intensity of 2.0–2.5 nA, and the beam spot size was 25–30 μm.

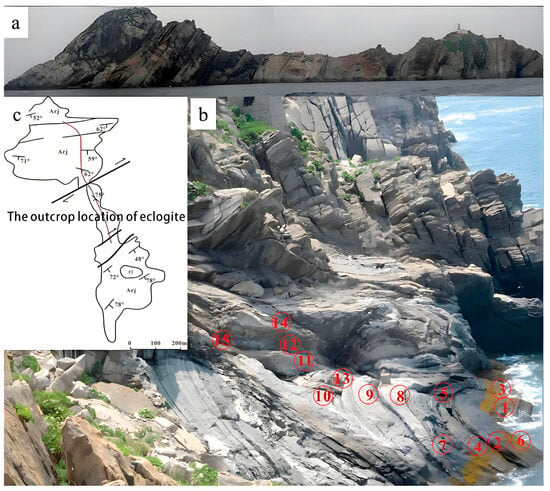

Figure 2.

The Qianliyan Island in the South Yellow Sea Foreland Basin. (a) The northwest side of Qianliyan Island, the massive rock mass, resulting from the continent–continent collision between the North China and Yangtze plates, underwent comprehensive fold uplift, culminating in its exposure at the Qianliyan Island location with an elevation of 209 meters above sea level. (b) The large elliptical outcrop of C-type eclogite ex-posed on the northeast side of the island, the structurally weak zone (Sample No. 15) exposes rutile-bearing eclogite, the red numbers, from 1 to 15, indicate the locations where the samples in Figure 3 were taken. (c) The outcrop location of eclogite.

Figure 3.

Eclogite samples from the study area. (a): the rock samples with their sampling locations corresponding to those shown in Figure 1. Samples ① to ⑭ consist exclusively of granitic gneiss, whereas sample ⑮ is identified as rutile-bearing eclogite. (b,c): polarized light microscopy images of the rutile-bearing eclogite, clearly highlighting the garnet (Grt) and omphacite (Omp) mineral phases.

Typically, five groups were scanned per sample, while for individual detrital zircon grains, three to four groups were scanned. The ratio of standard samples to unknown samples was set at 1:4. The Pb/U age was corrected using the standard zircon TEMORA (age 417 Ma), and the U-Th-Pb content was calibrated using the standard zircon M257 (U = 840 ppm). The 204Pb isotope measurement results were adjusted using the recognized calibration curve. Data processing was conducted using SQUID 4.0 and ISOPLOT 4.00 software. Individual data errors are reported at the 1σ level, and the average weighted age error confidence interval is 95%. For younger magmatic zircon ages (<1000 Ma), 206Pb/238Pb dating data were utilized. Mechanical separation and vertical magnetic enrichment of zircon/phosphate samples were achieved through the following steps: (1) primary heavy liquid enrichment using sodium polytungstate (SPT; non-toxic, density ~2.9); (2) magnetic separation; and (3) secondary heavy liquid enrichment using diiodomethane (Dim; toxic, density ~3.3). Apatite samples were etched in a 5M HNO3 solution at 20 °C for 20 s, while zircon samples were etched in a NaOH: KOH solution at 230 ± 1 °C for 5–20 h. Fission track age was calculated using the Zeta method, and fission track length was determined using a computerized system connected to a microscope.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Orogenic Belt Formed by the Collision of the Yangtze and North China Plates—The Qianliyan Island

The Thousand-mile Eye Island is situated in the northern part of the South Yellow Sea Basin, with a length of 800 m, an area of 0.2 square kilometers, and an altitude of 90.9 m. The terrain exhibits significant topographic variability (Figure 2). In September 2012, over 2000 photographs were captured around the island, revealing vertically oriented rock layers and a central axis formed by the collision of the Yangtze and North China plates on the northwest side (Figure 2). An elliptical large profile was identified below the high tide line on the southeast side. During an investigation conducted in July 2013, eclogite was discovered at the eroded portion of the elliptical large profile (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Polarizing microscopic analysis confirmed the eclogite as rutile-type C eclogite.

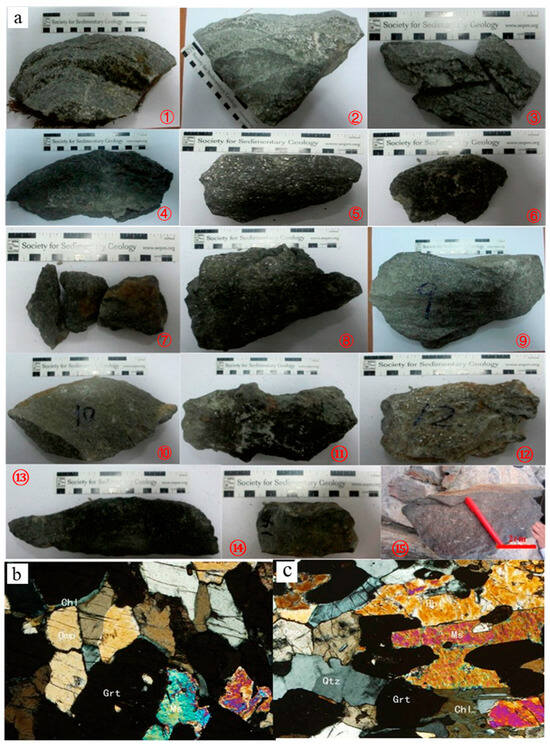

Given that the 207Pb/206Pb age determination method is significantly less precise than the 206Pb/238U method, the 206Pb/238U zircon cathodoluminescence (CL) dating technique was employed to differentiate between continuous (magmatic or detrital) zircons and growth zircons formed during metamorphic overprint in C-type eclogite (microprobe analysis). Continuous magmatic crystallization zircons exhibit a distinct magmatic crystallization zone; they emit strongly around the inner core of continuous zircons and weakly but uniformly on the sides [45]. The age of continuous zircons represents the age of the protolith of the eclogite, which corresponds to an older group of ages ranging from 416.7 to 768.3 Ma (Figure 4), signifying the formation age of the protolith of C-type eclogite. Subsequent thermal events resulted in incomplete recrystallization or varying degrees of Pb loss, leading to a younger group of zircon ages ranging from 205.8 to 244.2 Ma (Figure 4). These two groups, respectively, correspond to the age of the protolith of the Thousand-mile Eye Island C-type eclogite and the age of the collision between the Yangtze and North China plates.

Figure 4.

Ion probe age of zircon 206Pb/238U in C-type eclogite. Zircon ion microprobe dating locations and results data for garnet–pyroxene granulite showed in Figure 3. (a) the middle data represents the age of original zircon (766.5 Ma); the outer edge data is the secondary age (242.8 Ma); (b) the middle data represents the age of original zircon (751.9 Ma); the outer edge data is the sec-ondary age (726.8 Ma); (c) the age of original zircon (768.2 Ma); (d) the age of original zircon (241.8 Ma); (e) the age of original zircon (244.2 Ma); (f) the age of original zircon (416.7 Ma); (g) the age of original zircon (238.5 Ma); (h) the age of original zircon (205.8 Ma); (i) the age of original zircon (556.7 Ma); (j) the age of original zircon (736.2 Ma); (k) the age of original zircon (694.4 Ma).

4.2. The Fluvial Basin Resulting from the Collision of the Yangtze and North China Plates: Characteristics of the South Yellow Sea Foreland Basin

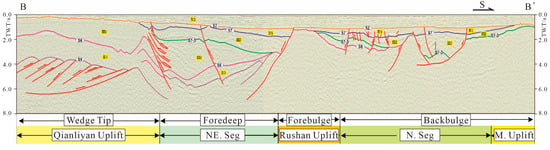

The South Yellow Sea foreland basin is situated between the Sulu Orogenic belt and the Lower Yangtze craton. It borders the Sulu Orogenic belt and runs parallel to the Qianliyan uplift, extending in a narrow and elongated band. During the Early to Middle Triassic, a peripheral foreland basin developed, leading to the formation of passive continental margin marine carbonate rocks. Subsequently, during the Early to Middle Jurassic collisional orogeny, this region evolved into an intracontinental foreland basin characterized by marine, fluvial, and lacustrine deposits, forming a typical foreland basin system [46]. Specifically: a. The wedge-top sedimentary zone is located at the front edge of the orogenic belt—the upper part of the Qianliyan uplift; b. The foredeep constitutes the primary sedimentary area, situated in the Northeast Depression, representing a classical foreland basin; c. The forebulge sedimentary zone is positioned over the Rushan uplift—a broad and gently elevated area; d. The backbulge sedimentary zone is found in the northern depression, which is a wide and shallow subsidence zone. Additionally, e. the wedge-top and foredeep zones were significantly affected by Late Indosinian and subsequent tectonic movements associated with the Pacific system, obscuring the distinct characteristics of each sedimentary zone. As depicted in Figure 5, a typical Mesozoic foreland basin deep-water sedimentary profile morphology and planar features emerged; the S-2 Well encountered over a thousand meters of Jurassic deep gray-black deep-water deposits (Figure 5) [40].

Figure 5.

Seismic Interpretation Characteristics of the South Yellow Sea Foreland Basin System and Its Structural Sedimentary Zones; the position of the figure is shown in Figure 1d (B-B’). S2: the Tertiary base interface in the South Yellow Sea Foreland Basin; S7: the Neogene base interface; S7-3: the Cretaceous base interface; S8: the Jurassic base interface; S9: the Triassic base interface. II3, III1, III2, IV1, IV2 are secondary stratigraphic sequences. II3, III1, III2, IV1 respectively represent the Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous and Paleogene strata, and IV2 represents the Neogene and Quaternary strata.

4.3. Structural Characteristics of the Foreland in the South Yellow Sea During the Collision Between the Yangtze and North China Plates

4.3.1. Imbricate Thrust Structures

The imbricate thrust structures are situated on the flank of the Qianliyan Uplift Basin, resulting from the southward imbricate superposition of the pre-Triassic basement. These fault-bounded platforms develop along weak layers (likely the Silurian gypsum layer), transecting through competent layers and forming several northward-dipping, stepped thrust slope structures.

4.3.2. Double-Thrust Structure

The double-thrust faults are situated at the front edge of the imbricate thrust system, consisting of a series of secondary imbricate thrusts and rock blocks intercalated between the basal and upper thrusts.

4.3.3. Triangular Structure

This structure represents a multi-layered composite anticline formed due to stress blockage near the craton at the leading edge of the thrust zone, resulting in fault-propagation folding.

4.3.4. Thrust Structure

As a result of collisional compression, bedding planes exhibit a lack of horizontal parallelism. Adjacent to the triangular structure, thrust structures develop, with thrust directions oriented toward the main fault. These structures occur predominantly south of the Qianliyan Fault and extend in an east–west orientation across the study area.

4.3.5. Gentle Detachment Folds

These structures are developed at the basin base and on the flank facing the central uplift. They consist of faults and detachment surfaces, which progressively flatten from north to south as the stress intensity diminishes.

4.3.6. Distribution of Fold Thrust Belts

The deformational structures within the Sulu Orogenic Belt and the Qianliyan Uplift primarily formed during the Mesozoic era. The South Yellow Sea foreland basin resulted from the north–south thrusting of the Sulu collisional orogenic belt, with stress gradually decreasing from north to south. Different thrusting actions led to the formation of distinct structural belts on a horizontal scale. Based on the interpretation of two-dimensional seismic profiles in the study area, it was observed that the Qianliyan Uplift Fold Thrust Belt is distributed along the Qianliyan Fault Zone; however, none of these structures penetrate through the Qianliyan Uplift. Only a small portion of this thrust belt is exposed. Considering the basin evolution and regional structural characteristics, it is inferred that a significant part of the western foreland basins, which were severely affected by subsequent tectonic compression, participated in the later orogenic belt movements, causing changes in the fold thrust belt. In contrast, the eastern part of the basin, where foreland basins are better preserved, exhibits more pronounced fold thrust belts. Therefore, a systematic analysis of the eastern basin was conducted, leading to the conclusion that there is significant divergence between the eastern and western parts of the basin.

4.3.7. Zonation and Structures of Thrust Overthrust Belts

Despite the high variability in the structural pattern of the South Yellow Sea Basin’s thrust fold belt, its zonation is evident. From the Sulu Orogenic Belt and the Qianliyan Uplift to the central uplift, tectonic activity progressively becomes gentler. This movement represents a typical thin-skinned deformation process.

4.4. Stratigraphic Age and Sedimentary Characteristics of the South Yellow Sea Basin

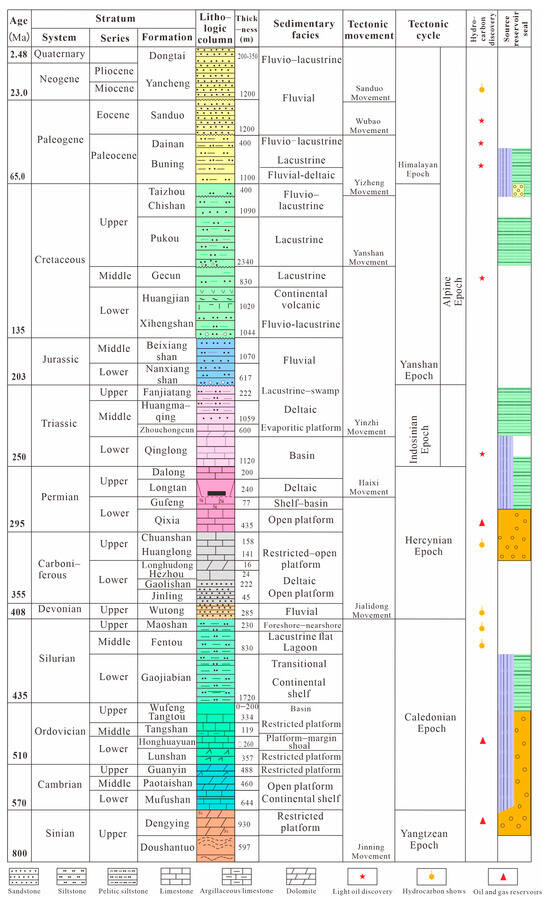

The South Yellow Sea Basin is a superimposed multi-cycle basin comprising marine and continental strata from the Paleozoic-Mesozoic and Mesozoic-Cenozoic eras, as interpreted from well and seismic data. The basin and its foreland basin have a thickness exceeding 2.3 × 104 m (Figure 6), making it unique among sedimentary basins in China’s offshore regions.

Figure 6.

Stratigraphic columnar section of the South Yellow Sea Basin. The colors in the lithologic column indicate the different Systems.

4.5. The Foreland Basin on the Southern Margin of the Qinling–Dabie–Sulu Orogenic Belt and Its Regional Evolution

The foreland basins in the Upper Yangtze continental area are situated between the Qinling–Dabie–Sulu Orogenic belt and the Jiangnan uplift, encompassing the foreland basins in western and northeastern Sichuan. In the Lower Yangtze continental area, foreland basins include the South Yellow Sea foreland basin. These basins represent Paleozoic passive continental margin sedimentary basins that formed as a result of the collision and assembly of the Yangtze and North China plates during the Triassic. Their evolution has proceeded through three stages: passive continental margin basins, peripheral foreland basins, and intracontinental foreland basins (Table 1) [47]. These basins initially developed along the passive continental margin at the southern edge of the orogenic belt and exhibit distinct foreland sedimentary sequences. Subsequent intracontinental orogenic movements led to the formation of multiple superimposed foreland basins with similar characteristics. Notably, the South Yellow Sea foreland basin in the marine region underwent extensive uplift and erosion due to the thrusting and compression associated with the Pacific system during later stages.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the foreland basins on the Southern Margin of the Qinling–Dabie–Sulu Orogenic Belt.

4.6. Comparison of the Chronological Characteristics of Eclogites from the Dabie–Sulu and Yangtze–North China Plate Continental Collision Zones

Previous studies on the metamorphic peak ages in the Sulu–Dabie region have demonstrated that the zircon U-Pb age of the Wumiao quartz eclogite is 214.2 ± 9.6 Ma; the zircon U-Pb ages of the Maomao eclogite near Maowu are 225.5 ± 3–6 Ma and 230 ± 4 Ma; and the zircon SHRIMP age of the Zhujia Chong eclogite is 231.6 ± 9.7 Ma. By means of Sm-Nd (samarium-neodymium) isotopic dating analysis, metamorphic peak age data were obtained respectively: 21 ± 5 Ma and 225 ± 7 Ma [48,49,50]. Predecessor analyzed Lu-Hf and Sm-Nd isotopes of Dabie ultrahigh-pressure eclogites and dated the ultrahigh-pressure event to 220–230 Ma [51]. These results indicate that the Sulu–Dabie eclogites formed during the high-pressure to ultrahigh-pressure event at approximately 220–230 Ma. This age is consistent with the SHRIMP zircon age of the Qianliyan eclogite and slightly younger than the whole-rock Sm-Nd age of 225–258 Ma for the Bibong metamorphic mafic rocks in South Korea [51].

4.7. Characteristics of Paleomagnetic Data

Paleomagnetic data reveal that the Yangtze and North China plates were once significantly separated but began to rapidly converge during the Triassic period [52]. Collision and amalgamation occurred during the Early to Middle Triassic, followed by synchronous rotational displacement in the Jurassic. These paleomagnetic data are highly consistent with the rapid uplift-cooling age (217 Ma) recorded by C-type eclogites on Qianliyan Island and align with the formation age of tectonic granites (227–221 Ma) as well as the relative rotation age derived from paleomagnetic data of the Yangtze and North China plates (Middle to Late Triassic). Based on sedimentary strata data from the Lower Yangtze land area, it is inferred that the geological boundary for the collision and amalgamation of the North China and Yangtze land blocks, as well as the transition from marine to continental sedimentation, corresponds to the Zhouchongcun–Huangmaqing Formation 4–5 boundary, with a geological age of late Early Triassic. In the Late Triassic, deep concave deep-water sedimentation developed in the northeastern part of the basin, ultimately forming a marine-continental-transitional sedimentary system.

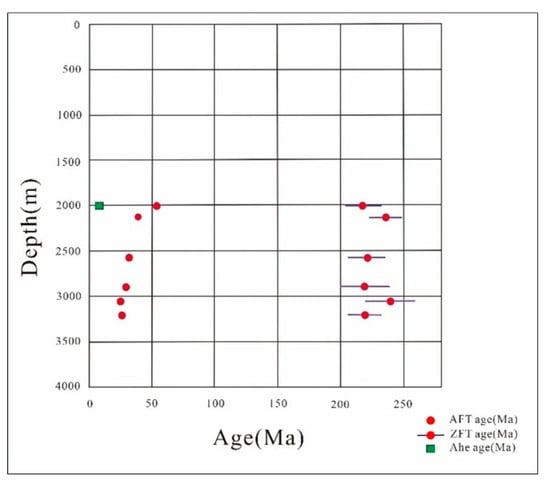

4.8. Structural Uplift and Erosion in the South Yellow Sea Basin

The S-2 well is located in the pre-sag sedimentary zone, where dozens of samples were collected, covering all depths of the Jurassic section. Zircon/phosphate was detected in only six samples, and their fission track ages as well as ZFT ages were analyzed from all samples. From top to bottom, the fission track ages decreased from 52 Ma to 25–26 Ma, while the average length of apatite fission tracks decreased from 13.3 μm to 11.2 μm (Figure 7). All apatite fission tracks are younger than the Jurassic strata of the corresponding samples.

Figure 7.

Relationship between zircon/phosphate fission track ages and sample depth of Well S-2, AFT age: Apatite Fission-Track age, ZFT age: Zircon Fission-Track age, Ahe age: Apatite (U-Th)/He age.

Based on the fission track ages and lengths of the six samples, a quantitative interpretation was conducted, revealing that most samples reside within the modern apatite fission track annealing zone. Assuming these apatite fission tracks are solely related to the modern strata temperature, i.e., the burial depth of late Tertiary strata, this would be highly inconsistent with observed data, as it fails to explain the significant decrease in apatite fission track ages. Therefore, the actual condition reflected should involve multiple severe annealing processes experienced by these apatite fission tracks relative to the depositional age of the samples.

Most samples’ apatite fission tracks had completely annealed prior to the deposition of late Tertiary strata, except possibly for the shallowest sample (R1-6). Following these processes, a heating effect caused by burial at approximately 803 m during the late Tertiary occurred. This suggests that maximum sedimentary burial likely occurred during the early Tertiary. Uplift and erosion events took place from the Early to Late Eocene and Early to Late Oligocene, prior to 38 Ma. The fission track ages of the other five deeper samples can be interpreted as cooling ages, with minor adjustments following local annealing during the Late Tertiary. These evolutionary processes resulted in an estimated erosion of up to 3 km. This may correspond to a cooling temperature of approximately 80–90 °C for this stratum from the Cretaceous to the Paleogene. Seismic profiles surrounding this well support the extensive erosion of Neogene angular unconformity strata [53]; the Late Tertiary deposition of approximately 830 m may have buried these samples’ strata to the temperature range of the modern apatite fission track annealing zone, but it likely did not cause significant annealing.

4.8.1. Apatite (U-Th)/He Age and Interpretation

The apatite (U-Th)/He age of sample R1-6 (Figure 7) is 8 Ma, significantly lower than its apatite fission track (AFT) age of 52 Ma. This suggests a Late Mesozoic cooling event. The current burial depth of this sample is 1950 m, corresponding to a geothermal gradient of 31 °C/km, placing it within the apatite (U-Th)/He partial annealing zone (65–70 °C). The simplest explanation for this discrepancy is that the apatite (U-Th)/He age reflects thermal conditions established during the Neogene. By integrating the apatite (U-Th)/He age of this sample with fission track data and employing thermal evolution modeling, a more comprehensive thermal history interpretation can be derived.

4.8.2. Zircon Fission Track Age and Stratal Erosion

The zircon fission track ages of the six samples range from 217 to 239 Ma (Figure 7). Notably, these ages predate the sedimentary age of the Jurassic strata hosting these samples, indicating that they represent the zircon fission track ages of the source region. Specifically, these ages correspond to the time when the source material cooled below 280 °C. This implies that the source zircons underwent at least one major tectonic event between 210 and 239 Ma, leading to cooling and significant stratal erosion.

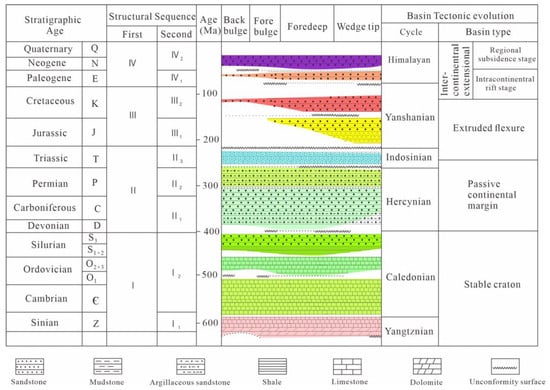

4.9. Tectonic Evolution Model

The South Yellow Sea foreland basin originated from the pre-orogenic subduction of the Sulu Ocean Basin and formed during the main orogenic period following the collision of the North China and Yangtze plates. It subsequently evolved during the post-orogenic extensional-rift transition, experiencing four distinct stages of plate movement: the stable craton stage, the passive continental margin stage, the compressive and flexural basin stage, and the intracontinental extensional basin stage. The tectonic evolution model is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Tectonic Evolution Model of the South Yellow Sea Basin. The colors in the lithology column indicate the different Systems.

4.9.1. Stable Craton Stage (∈-O-S)

- (1)

- Stable Craton (∈)

Following the entry of the Yangtze Platform into the Caledonian period during the Cambrian, its northern and southern margins were characterized by continental margin basins, while the central region exhibited a stable craton margin sea environment. In the Lower Yangtze area of the Yangtze Platform, Early Paleozoic deep-sea basins were extensively distributed, transitioning to carbonate platforms, restricted platforms, and slope deposits during the Middle and Late Paleozoic [54]. The Mugushan Formation features regionally deposited dark gray or black carbonaceous mudstone; the Paotaishan Formation and Guanyin Formation consist of dark gray thin-to-thick dolomite deposits.

- (2)

- Continuously Stable Craton (O)

During the Ordovician, the Caledonian tectonic cycle persisted, with the development of deep-sea basins, open platforms, slopes, and localized peripheral foreland systems [55]. This period saw the formation of dark gray or gray dolomitic limestone (Lunshan Formation), bioclastic mudstone (Honghuayuan Formation), gray-green nodular mudstone limestone (Tangshan Formation and Tangtou Formation), and gray-to-grayish-black siliceous shale (Wufeng Formation).

- (3)

- Shrinkage Craton (S)

In the Silurian, the Yangtze Platform experienced an unconformable overlying relationship due to the Guangxi Movement overlying the underlying Ordovician strata, leading to the gradual shrinkage of the craton [56]. Sedimentary environments of craton depressions and peripheral foreland systems developed during this stage. Grayish-yellow or grayish-green limestone and mudstone were partially replaced by thin sandstone layers, with black shale (Gaojiabian Formation) observed at the base. Additionally, grayish-yellow or grayish-white quartz sandstone was locally replaced by mudstone, accompanied by the localized development of phosphomanganese rocks.

4.9.2. Passive Continental Margin Basin Stage (D-P-T)

- (1)

- Stable Passive Continental Margin (D)

During the Devonian, the Hercynian tectonic cycle initiated, with this region unconformably overlain by Silurian strata due to the Dongwu Movement [57]. The lower part of the sequence consists of Wutong grayish-yellow or gray siltstone, slightly colored sandstone, and coarse-grained quartz sandstone.

- (2)

- Local Rift Depression (P)

In the Permian, the northern margin of the Lower Yangtze Block subducted beneath the North China Block, leading to the contraction of the Sulu Ocean Basin [58]. The northern part of the South Yellow Sea gradually transitioned from an extensional-expansive tectonic environment to a convergent-contractive one, marking the onset of foreland basin evolution. Subduction-induced uplift of the passive continental margin resulted in the formation of a localized rebound rift valley. During this period, deep to semi-deep marine sedimentary deposits developed [59]. Notably, the upper Permian Dalong Formation in the southern part of the South Yellow Sea borehole contains deep gray or dark gray siltstone with pyrite and algal fossils, while radiolarian cherts from the same formation are found in the land area between Nanjing and Anqing within the Lower Yangtze Block.

- (3)

- Continuous Subsidence (T1)

In the Early Triassic, the ocean basin continued to subduct, causing extensive subsidence of the continental margin in the northern part of the South Yellow Sea [60]. This led to deepening of the sea and deposition of deep marine sedimentary groups (Qinglong Formation) [61]. Based on drilling data from the South Yellow Sea and geological records from the Lower Yangtze Block on land, the lower Qinglong Formation is primarily composed of micritic interbedded mudstone limestones, with black mudstone siltstones in the middle. The upper Qinglong Formation predominantly consists of gray or dark gray micrites. However, significant sedimentary differentiation occurred during the later stages of this formation: dolomite deposits developed in the northern part of the basin, indicating the beginning of ocean basin contraction.

- (4)

- Shrinkage-remnant (T21)

During the early Middle Triassic, the Sulu Ocean Basin underwent subduction-induced closure, leaving only localized remnants. Based on data from the Lower Yangtze continental area, significant deposits of evaporitic platform-lagoon dolomite and gypsum were formed in the Zhuchongcun Formation during the Middle Triassic. This suggests that as the ocean basin progressively disappeared, sedimentation associated with the passive continental margin was nearing its termination, marking the onset of the early developmental stage of the foreland basin.

- ①

- Marine-Continental Sedimentation (T22)

The collision between the Yangtze Block and the North China Block entered its main orogenic phase during the Middle Triassic [62]. High-pressure to ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism occurred in crustal slices subducted into the deep lithosphere. Intense flexural subsidence developed between the orogenic front and the Lower Yangtze Craton, forming a long and narrow foreland basin parallel to the orogenic belt. In the late Middle Triassic, with the termination of marine sedimentation, the foreland basin began to receive continental sediments derived from the orogenic belt or its adjacent craton, marking the transition from marine to marine-continental sedimentation. The Huangmaqing Formation, located in the upper part of the Middle Triassic in the Lower Yangtze land area, represents the most typical marine-continental sedimentation. Its lower section consists of marine clastic rocks, including thin siltstone or silty shale layers interbedded with medium-thick dolomite or calcareous fine sandstone layers, while its upper section comprises red sandstone and mudstone sourced from the orogenic belt, reflecting marine-continental sedimentation characteristics.

- ②

- Continental Sedimentation (T3)

During the Late Triassic, the foreland depression ceased receiving marine sedimentation and instead began to accumulate continental sediments derived from the orogenic belt, predominantly characterized by deltaic sedimentation [54]. The most representative example of this continental sedimentation is the Fanjiatang Formation of the Upper Triassic in the Lower Yangtze continental area, which consists of gray or gray-black sandstone, siltstone, and sandy shale, with minor intercalations of carbonaceous shale. During this sedimentary phase, the upper and lower groups exhibit conformable contact, indicating a continuous and progressive sedimentary process. With the termination of the Indosinian Orogeny in the Late Triassic, the collision and compression between the Yangtze Block and the North China Block also concluded. This marked the onset of continuous intra-plate orogenic activity and the end of the peripheral foreland basin stage. However, due to subsequent intra-plate orogenic compression and deformation, the peripheral foreland basin developed intra-basin fold structures, further modifying the overall basin architecture.

- ③

- Intracontinental Foreland Basin (J1-J2)

At the end of the Late Triassic, although the Yangtze Block and the North China Block had already collided and amalgamated, they continued to interact through shear-induced relative rotation towards the west. This process was accompanied by significant crustal shortening and intracontinental relative rotation, transitioning the Dabie–Sulu Orogenic belt into the intracontinental subduction orogenic stage. Concurrently, the northern part of the North Yellow Sea Basin entered the intracontinental foreland basin stage. Influenced by intracontinental orogenic activity, the North Yellow Sea Basin continued to flexurally subside. During the Early Jurassic, the Xiangshan Formation was deposited, characterized by interbedded fine sandstone and mudstone. Semi-deep to shallow lacustrine and deltaic facies developed, forming an unconformable contact with the marine-continental facies of the Middle and Late Triassic.

By the end of the Middle Jurassic, the intense compressive force associated with the Early Yanshanian Orogeny induced structural deformation. The northern part of the North Yellow Sea Basin experienced continued uplift, leading to a reduced sedimentation rate. Weak structural zones were subjected to thrusting and subsequent erosion, signaling the gradual demise of the intracontinental foreland basin. Simultaneously, bidirectional asymmetric slope structural belts formed on either side of the central uplift. These structural belts exhibit steep dips in their shallow parts and relatively gentle dips in their deeper sections, resembling a plow shape with the convex side facing upward.

- ④

- Extensional Faulted Basins (J3-K1-E)

At the end of the Late Jurassic, the sedimentation of the intracontinental foreland basin concluded. Influenced by the tectonic movements of the Pacific Plate, the study area transitioned from a foreland compressional tectonic environment to an extensional-tensional tectonic regime, forming a post-orogenic continental extensional faulted basin. Based on sedimentary evolution, this stage can be further subdivided into two sub-stages: the transformation-extension adjustment stage and the intracontinental extensional-faulting sedimentation stage.

- a.

- Transformation-Extension Adjustment (J3-K1)

From the Late Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous, the Pacific tectonic domain exhibited high activity. The South Yellow Sea region began transitioning from a foreland compressional tectonic environment to an extensional-tensional tectonic regime, initiating the transformation-extension adjustment phase. This stage was characterized by intense strike-slip faulting, thermal expansion and contraction, as well as a complex interplay of compressional, shearing, and extensional forces, with shearing being the dominant tectonic mode. Concurrently, a series of inverted structures, oriented similarly to the Tan-Lu Fault, were formed in this area. This marked the onset of widespread faulting movements that extended from the Late Mesozoic into the Cenozoic, laying the foundation for the current tectonic architecture of the South Yellow Sea Basin.

- b.

- Intracontinental Extensional Faulting (K2-E)

From the Late Cretaceous to the Paleogene, the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the Eurasian Plate resulted in intense back-arc tectonic uplift, extension, and widespread thermal subsidence. Large-scale erosion occurred in the South Yellow Sea foreland basin during this period. These processes induced significant structural deformation and erosion of both local and regional sedimentary strata, such as the formation of a convex-concave-convex profile pattern in the deep to ultra-deep depression zone at the forefront of the foreland basin. The K/N, E/N, and T2/N angular unconformities represent typical contact relationships identified in seismic stratigraphic sequence interpretations across the entire basin, corresponding to an erosion thickness of sedimentary strata exceeding 3 km.

The Lower Paleozoic, Upper Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic strata are superimposed in the South Yellow Sea Basin, forming a multi-stage causative sedimentary basin characterized by the coexistence of four geological eras. This four-era coexisting basin is present simultaneously in both the northern and southern parts of the South Yellow Sea and represents a residual prototype basin. The sedimentary center gradually migrated in an SSE-NNW direction over time. Drilling activities have been conducted primarily in the southern part of the basin; however, all wells were relatively shallow. The deepest well was drilled by South Korea, but no hydrocarbon discoveries were made.

5. Discussion

5.1. The South Yellow Sea Foreland Basin System Represents the Only Well-Documented and Classic Foreland Basin System Discovered in China to Date

The comprehensive study of the geometry of foreland basins and highlighted that the traditional definition of foreland basins as curved subsidence zones between an orogenic belt and its adjacent craton was incomplete, as it overlooked the widespread occurrence of sediments derived from the orogenic belt and accumulated atop the orogenic wedge [6,25,63]. Consequently, foreland basins not only encompass the curved subsidence zone but also extend into both the orogenic belt and the adjacent craton. Based on this understanding, the concept of the “foreland basin system” was proposed, defined as a narrow region with potential sediment accommodation capacity formed on the continental crust between a contracting orogenic belt and its adjacent craton. This system primarily responds to geodynamic processes associated with subduction and the resultant peripheral or back-arc fold-thrust belts. The longitudinal extent of a foreland basin system is approximately equivalent to the length of the fold-thrust belt, and it comprises four distinct sedimentary structural zones: the wedge-top sedimentary zone, the foredeep sedimentary zone, the forebulge sedimentary zone, and the backbulge sedimentary zone. Each sedimentary zone exhibits unique structural characteristics compared to the others. It is evident that the South Yellow Sea foreland basin not only develops these typical foreland basin discrete sedimentary zones but also features a curved subsidence zone that extends into the orogenic belt and the adjacent craton, located within the northern uplift area.

5.2. Mesozoic Plate Tectonic Evolution Chronology and Sedimentology

The zircon chronology and P-T-t paths of eclogites from Qianliyan Island and the Dabie–Sulu Orogen provide a chronological framework for ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic evolution in the context of continental collision. Progressive metamorphism of eclogites commenced in the Early Triassic and continued until approximately 247 Ma. Around 240 Ma, the ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic stage began and persisted until approximately 220 Ma. Retrograde metamorphism of the ultrahigh-pressure rock series initiated around 219 Ma and extended until approximately 201 Ma. These findings constitute critical evidence for analyzing the dynamic evolution process of the collision between the North China and Yangtze plates, as well as the structural evolution characteristics of associated foreland basins.

Paleoenvironmental changes in the Lower Yangtze marine basins during the Triassic are examined, revealing a close relationship between these changes and the collision and accretion of the North China and Yangtze plates. The Triassic paleoenvironmental changes in the Lower Yangtze land area and the South Yellow Sea represent responses to the Triassic collision and accretion of the North China and Yangtze plates. From the perspective of basin-mountain coupling, the collision led to mountain formation and the creation of Qianliyan Island. Foreland basins formed from the Late Permian to the Early Triassic (approximately 246 Ma) and evolved into a residual ocean basin characterized by local deep to semi-deep marine sediments. In the Late Triassic (approximately 247–241 Ma), a deep-water environment and passive continental margin marine sediments were established. Following the collision, during the Middle Triassic (approximately 240–220 Ma), marine sediments transitioned into continental sediments sourced from the Sulu Orogen and adjacent source areas. In the Late Triassic (approximately 219–201 Ma), foreland basins were predominantly filled with continental sediments. By the Jurassic, a deep-water sedimentary basin developed within the fore-arc tectonic zone, as evidenced by the approximately 2000 m thick black mudstone deposits encountered in Well S-2.

5.3. The Tectonic Evolution of the South Yellow Sea Basin Since the Paleozoic Has Been Significantly Influenced by the Subsequent Subduction and Accretion Processes Associated with the Pacific System, Which Fundamentally Distinguishes It from the Upper Yangtze Basin

The South Yellow Sea Basin represents a large, multi-stage superimposed hydrocarbon-bearing sedimentary basin in the Lower Yangtze Sea area. From the Cambrian to the Permian, the basin was characterized as a passive continental margin sea basin, featuring organic-rich deep-water sedimentary shales such as the Cambrian Mugushan Formation, the Lower Permian Qixia Formation, and the Upper Permian Dalong Formation. In the Middle Triassic, the basin transitioned into a peripheral foreland basin, and by the end of the Triassic, marine and continental clastic sediments began to accumulate. From the Early Jurassic to the Middle Jurassic, the basin evolved into an intracontinental foreland basin sedimentary zone, characterized by both foreland clastic sediments and deep-water sediments. Since the Late Jurassic, the basin experienced rapid uplift and erosion. Through zircon apatite fission track studies, it was first confirmed that the strata of the South Yellow Sea Basin have undergone large-scale uplift, with an estimated erosion thickness exceeding 3000 m. This finding aligns with the E/N, K/N, and T2/N angular unconformities interpreted from seismic data within the basin. These processes disrupted the tectonic evolution since the Cambrian, altered the hydrocarbon enrichment patterns within the basin, and determined the distinct characteristics of hydrocarbon exploration in the Upper and Lower Yangtze basins. Only through exploration of the deep prototype basin, analogous to the 7 km-deep oil and gas wells in the Upper Yangtze Sichuan Basin, can significant industrial hydrocarbon discoveries potentially be achieved in the South Yellow Sea Basin.

6. Conclusions

The discovery of Shantianyan Island in the northern part of the South Yellow Sea, formed by the Indosinian collision between the Yangtze and North China plates, has revealed an elliptical large cross-section structural weakness where C-type eclogite is exposed. This C-type eclogite represents the product of a subducting plate plunging to a depth of approximately 130 km before exhumation to the surface. The metamorphic zircon SHRIMP U-Pb age of the C-type eclogite ranges from 217 to 247 Ma. The identification of the basin formed post-Indosinian collision includes a Middle Triassic peripheral foreland basin and a Middle-Late Jurassic intracontinental foreland basin. The formation of the Mesozoic foreland basin in the South Yellow Sea was delayed by approximately 20 million years relative to the collision event, with ages consistent with paleomagnetic results. A typical foreland basin system characterized by wedge-top, foredeep, forebulge, and backbulge sedimentary belts was established, with the foredeep area exceeding 8000 km2. The stages and characteristics of the tectonic evolution of the South Yellow Sea foreland basin since the Cambrian have been clarified, and a comprehensive tectonic evolution model has been proposed.

Through the analysis of zircon and apatite fission tracks in Well S2, it was revealed that the South Yellow Sea experienced significant tectonic uplift during the Late Cretaceous to Paleogene, including large-scale erosion of strata within the basin, with an estimated thickness exceeding 3 km. Integrated interpretation of well and seismic data confirmed the consistency of multiple angular unconformities, such as E/N, K/N, and T2/N. The differences in tectonic evolution between the Upper and Lower Yangtze regions were highlighted: the Lower Yangtze region was subsequently influenced by the subduction of the Philippine-Pacific Plate beneath the Eurasian Plate, leading to multiple episodes of tectonic uplift and erosion in the South Yellow Sea Basin, which constitutes its most prominent tectonic feature. Since the Middle Triassic to the Jurassic, hydrocarbon preservation in the South Yellow Sea Basin has been challenging. Deep exploration targeting the original hydrocarbon reservoirs in the basin may represent the optimal strategy for current hydrocarbon exploration deployment, facilitating the potential achievement of industrial hydrocarbon discoveries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X.; methodology, H.X. and Y.M.; software, B.Z. and B.L.; validation, D.S. and W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.X. and W.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.M. and G.Z. (Guangyou Zhu); visualization, G.Z. (Guoqing Zhang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by projects of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 49206061; No. 41872114); Laolongtou Ecological Restoration and Protection at Stone Island Project; National Major Science and Technology Projects for Oil and Gas (No. 2011ZX05025-002-04); National Science and Technology Basic Resources Survey Project (No. 2017FY201407); Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42130408); Key Research and Development Project of Hainan Province (Grant No. ZDYF2025GXJS013); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42576253); Hainan Province natural science Foundation project (Grant No. 423MS132); Key Consultative Research Project of Hainan Institute of Strategic Studies on Engineering and Technology Development of China (Grant No. 25HNZX-06), Guangzhou City Supplementary Project for Basic and Applied Basic Research (2025MGMS-HBZ-009).

Data Availability Statement

The data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions and guidance of Li Sitian, Cai Ganzhong, Gong Zaiseng, and Guo Zhenxuan. We also extend our sincere gratitude to the Beijing SHRIMP Center, Xu Ganqing from the University of Waikato, New Zealand, the China Geological Survey, and the Ministry of Science and Technology for their continuous support and funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Suess, E. Antlitz der Erde. Geol. Mag. 1910, 7, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stille, H. The present tectonic state of the Earth. AAPG Bull. 1936, 20, 849–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloos, E. Structural Geology of North America. Science 1951, 114, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, W.R. Plate tectonics and sedimentation. Spec. Publ. 1974, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner, J.C.; Bertram, G.T. Sequence stratigraphy of foreland basin deposits: Outcrop and subsurface examples from the Cretaceous of North America. Econ. Geol. 1995, 79, 354–371. [Google Scholar]

- Decelles, P.G.; Giles, K.A. Foreland basin systems. Basin Res. 1996, 8, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.Y.; Hu, X.M.; Garzanti, E.; BouDagher-Fadel, M.K.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wolfgring, E.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S. Pre—Eocene Arabia—Eurasia collision: New constraints from the Zagros Mountains (Amiran Basin, Iran). Geology 2023, 51, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konyuhov, A.I.; Maleki, B. The Persian Gulf Basin: Geological History, Sedimentary Formations, and Petroleum Potential. Lithol. Miner. Resour. 2006, 41, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.A.; Allen, J.R. Basin Analysis: Principles and Applications; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Wu, X.Y.; Yang, Y.K. Characteristic analysis and initial understanding of hydrocarbon distribution of foreland basins in the world. Prog. Geophys. 2009, 24, 205–210, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.; Meng, Z.F.; Luo, S.C.; Feng, X.J.; Jing, B.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.J. Tectonic evolution sequence of the Niaoshan structural belt in the Tarim Basin and its significance for hydrocarbon exploration. Acta Geol. Sin. 2009, 83, 1274–1284, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.Z.; Wei, G.Q.; Li, B.L.; Xiao, A.C.; Ran, Q.G. Tectonic evolution of two-epoch foreland basins and its control for natural gas accumulation in China′s mid-western areas. Editor. Off. Acta Pet. Sin. 2003, 24, 13–17, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.-Y.; Jin, Z.-J.; Zhang, D.-W.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Li, J. Geochemical Characteristics and Genesis of Natural Gas in Tarim Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2008, 19, 234–237, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.Q.; Lu, Y.L.; Tang, Y.Q.; Mattauer, M.; Matte, J.; Malavieille, P.; Tapponnier, H. Maluski Deformation characteristics and tectonic evolution of the eastern Qinling orogenic belt. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2010, 60, 23–25, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.W.; Meng, Q.R.; Lai, S.C. Tectonics structure of Qinling Orogenic belt. Sci. China Chem. 1995, 11, 1379–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lion, J.C.; Mao, H.K. Coesite-bearing eclogites from the Dabie Mountains in central China. Geology 1989, 19, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.L.; Gerdes, A.; Xue, H.; Liang, F. SHRIMP U-Pb zircon dating from eclogite lens in marble, Dabie-Sulu UHP terrane: Restriction on the prograde, UHP and retrograde metamorphic ages. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2006, 22, 1761–1778. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.L.; Xue, H.M. Review and prospect of SHRIMP U-Pb dating on zircons from Sulu-Dabie UHP metamorphic rocks. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23, 2737–2756. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.O.; Kusky, T.M. The late Permian to Triassic Hongseong-Odesan collision belt in South Korea, and its tectonic correlation with China and Japan. Int. Geol. Rev. 2007, 49, 636–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.G.; Guo, J.H.; Li, Z.; Chen, D.Z.; Peng, P.; Li, T.S.; Zhang, Y.B.; Hou, Q.L.; Fan, Q.C.; Hu, B. Extension of the Sulu UHP Belt to the Korean Peninsula: Evidence from Orogenic Belts, Precambrian Basements, and Paleozoic Sedimentary Basins. Geol. J. China Univ. 2007, 13, 415–428. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.Y. Marine and Continental Geotectionics of China and Its Environs; Chinese Science Press: Beijing, China, 1986; pp. 45–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X.L. China-Korea Fault Block, Marine and Continental Geotectionics of China and Its Environs; Chinese Science Press: Beijing, China, 1986; pp. 160–162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, K.J.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q.; Sun, S.; Şengör, A.M.C. Tectonics of south China: Key to understanding West Pacific geology. Tectonophysics 1990, 183, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, W.C.; Liou, J.G. Constrasting plate-tectonic styles of the Qinling-Dabie-Sulu and Fransiscan metamorphic belts. Geology 1995, 23, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ree, J.H.; Cho, M.; Kown, S.T. Possible eastward extension of Chinese collision belt in South Korea: The Imjingang belt. Geology 1996, 24, 1071–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.W.; Choi, S.G.; Song, S.H. Metamorphic evolution of metabasites and country gneiss in Baekdong area and its tectonic implication. J. Petrol. Soc. Korea 2002, 11, 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.H.; Zhai, M.; Oh, C.W.; Kim, S.W. 230Ma eclogite from Bibong, Hongseong area, Gyeonggi Massif, South Korea: HP metamorphism, zircon SHRIMP U–Pb ages, and tectonic implication. In Abstract Volume of International Association for Gondwana Research, South Korea Chapter; Miscellaneous Pbl.: Chonju, Republic of Korea, 2004; pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.Q.; Yang, J.S.; Li, H.B.; Yao, J.X. The Early Palaeozoic Terrene Framework and the Formation of the High-Pressure (HP) and Ultra-High Pressure (UHP) Metamorphic Belts at the Central Orogenic Belt (COB). Acta Geol. Sin. 2006, 80, 1793–1806. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Hang, Y.; Li, S. A study on the mineral chemistry and genesis of the eclogite from Qianliyan Island, the southern Huanghai Sea. Trans. Oceanol. Limnol. 2007, 1, 83–87, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.P.; Yan, J.Y.; Schertl, H.P.; Kong, F.M.; Xu, H. Eclogite from the Qianliyan Island in the Yellow Sea: A missing link between the mainland of China and the Korean peninsula. Eur. J. Mineral. 2014, 26, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, H.Y. Tectonic evolution of the north Jiangsu-south Yellow Sea basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2003, 25, 562–565, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yao, R.; Luo, K.P.; Yang, C.Q. Features of thrust nappe structure in northern South Yellow Sea. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2011, 33, 282–284, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Suh, M.; Choi, S.; Hao, T.Y. Deep structure characteristics and geological evolution of the Yellow Sealand and its adjacent regions. Chin. J. Geophys. 2003, 46, 803–808, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Shinn, Y.J.; Chough, S.K.; Hwang, I.G. Structural development and tectonic evolution of Gunsan Basin (Cretaceous-Tertiary) in the central Yellow Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2010, 27, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.Q.; Li, X.Q.; Xu, H. Characteristics of the fault system in the northern south Yellow Sea basin and its forming mechanism. Mar. Geol. Front. 2016, 32, 11–17, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.J.; Li, S.Z.; Suo, Y.H.; Guo, L.L.; Dai, L.M.; Jiang, S.H.; Wang, G. Structure and formation mechanism of the Yellow Sea Basin. Geosci. Front. 2017, 24, 239–248, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q.Z. Regional geology and geotectonic environment of petroliferous basin the Yellow Sea. Mar. Geol. Lett. 2002, 18, 8–12, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q.Z. Oil and Gas Geology in China Seas; Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 2005; pp. 131–150. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, B.C. The geotectonic characteristics and the petroleum resources potential in the Yellow Sea. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2006, 26, 85–93, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Han, Z.Z. Geological Features and Hydrocarbons of Qianliyan Island-Lingshan Island in the South Yellow Sea; China, Science Press: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dai, M.G. Research progress in geology and geophysics characters of the Yellow Sea. Prog. Geophys. 2003, 18, 583–591, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.L.; Tan, S.Z.; Hou, K.W. Distribution pattern of the Jurassic in the south Yellow Sea and its tectonic implications. Mar. Geol. Lett. 2015, 3, 7–12, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.M. Geological structures and petroleum resources in Yellow Sea. China Offshore Oil Gas (Geol.) 2003, 17, 79–88, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.L.; Lu, H.F.; Li, G.; Gang, L.I. Paleogene extensional fault-bend folding in north depression of southern Yellow Sea basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2006, 27, 495–503, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Han, Z.Z.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Lai, Z.Q. Metamorphic P-T-t Path of Eclogites from Qianliyan Island in the South Yellow Sea and Its Tectonic Implications. Earth Sci.-J. China Univ. Geosci. 2014, 39, 1289–1300, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Seonghoon, M.; Han-Joon, K.; Sookwan, K. Tectonic evolution of the eastern margin of the Northern South Yellow Sea Basin in the Yellow Sea since the Late Cretaceous. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2024, 274, 106287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.G.; Liu, H.P. Evolution and types of foreland basins around the Yangtze Block. Earth Sci. J. China Univ. Geosci. 1996, 4, 433–440, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chavagnac, V.; Jahn, B.M. Coesite—Bearing eclogites from the Bixiling Complex, Dabie Mountains, China: Sm–Nd ages, geochemical characteristics and tectonic implications. Chem. Geol. 1996, 133, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Zhou, H.W.; Ding, S.J.; Li, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.M.; Ge, W.C. The age and tectonic significance of the “Bangxi–Chenxing ophiolite slice” in Hainan Island—Constraints from Sm–Nd isotopes. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2000, 16, 425–432, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.H. Chronological framework and isotopic system constraints on crustal growth and tectonic evolution of South China. Bull. Mineral. Petrol. Geochem. 1993, 12, 111–115, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; King, R.L.; Nakamura, E.; Vervoort, J.D.; Zhou, Z. Coupled Lu–Hf and Sm–Nd geochronology constrains garnet growth in ultra-high-pressure eclogites from the Dabie orogen. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2010, 26, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.X.; Yang, Z.Y.; Ma, X.H.; Wu, H.Y.; Meng, Z.F.; Fang, D.J.; Huang, B.C. Apparent polar wander paths of Phanerozoic paleomagnetism and block movements of major blocks in China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 1998, A2, 1–17, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.Q.; Guo, X.W.; Zhang, X.H.; Qi, J.H.; Xiao, G.L. Geophysical characteristics of the South Yellow Sea strata revealed by the Continental Shelf Drilling Program (CSDP-2) well. Mar. Geol. Front. 2019, 35, 78–81, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.J.; Dou, Z.Y.; Chen, J.W.; Zhang, Y.G.; Liang, J. Marine Paleo-Mesozoic hydrocarbon source rocks on land of the Lower Yangtze Platform and their controlling factors: Implications for the South Yellow Sea Basin. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2017, 37, 138–146, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.B. Marine sedimentary response to the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event: Examples from North China and South China. Paleontol. Res. 2009, 13, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.J.; Cui, M. Key tectonic changes, deformation styles and hydrocarbon preservations in Middle-Upper Yangtze region. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2011, 33, 12–16, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.D.; Hou, M.C.; Liu, W.J.; Tian, J.C. Hercynian–Indosinian basin evolution and sequence framework in South China. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. 2004, 31, 629–635, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.J.; Cai, J.X.; Zhu, J.X. North China and South China collision: Insights from analogue modeling. J. Geodyn. 2006, 42, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.B.; He, M.X.; Zhang, Y.X.; Xie, Q.F.; Ma, R.F.; Zhang, D.M. Tectonic evolution and sedimentary characteristics of the foreland basin in the northern part of Lower Yangtze area. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2007, 29, 133–137, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Z.W.; Hu, W.X.; Cao, J.; Wang, X.L.; Hu, Z.Y. Petrologic and geochemical evidence for the formation of organic-rich siliceous rocks of the Late Permian Dalong Formation, Lower Yangtze region, southern China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 103, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.J.; Su, S.Z.; Zhang, J.N.; Shi, G.J.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Chen, Q.H. Characteristics and research direction of Triassic in the South Yellow Sea Basin, China. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Zhao, Z.F.; Chen, R.X. Ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic rocks in the Dabie–Sulu orogenic belt: Compositional inheritance and metamorphic modification. Geol. Soc. 2019, 474, 89–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.; Allen, J.R. Basin Analysis: Principles and Application to Petroleum Play Assessment; Wiley-Blackwell Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).