Abstract

According to the International Maritime Organization, transitioning to alternative fuels is essential to achieving net-zero carbon emissions. Seafarers are at the frontline of this transition, and in this study, their attitude toward this strategy is analyzed using the technology acceptance model. The alternative fuels analyzed are liquefied natural gas (LNG) and methanol as short-term options and hydrogen and ammonia as long-term options. The analyzed seafarers are from South Korea, where alternative fuels are actively incorporated into shipbuilding and training. Across all fuels, perceived ease of use (PEOU) positively affected perceived usefulness (PU). PEOU and PU positively influenced attitude toward using (ATT). ATT and trust (TRU) significantly increased behavioral intention (BI), a finding that aligns with those of prior studies, while operational safety risk (OSR) also showed a positive effect on ATT. This indicates that seafarers became more aware of the need to use alternative fuels and expected improvements in managing related risks. Unlike OSR, environmental risk (ER) negatively affected ATT for hydrogen, consistent with prior risk perception studies. These findings suggest that to encourage alternative fuel use during the shipping industry’s energy transition, operational ease, enhanced risk management systems, and basic competency training and incentives are necessary to positively shape seafarers’ attitudes and behavioral intentions.

1. Introduction

The international shipping industry is navigating tremendous changes in response to regulatory pressures and societal demands for decarbonization [1,2,3,4,5]. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) revised its greenhouse gas (GHG) strategy by setting a target to achieve net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 [6]. While such policies and societal shifts are essential within the decarbonization framework, they must consider diverse challenges encountered across technological, economic, and safety dimensions [4,7,8,9]. In alignment with the IMO’s GHG strategy, the industry is currently reducing its carbon intensity through short-term efficiency measures such as route optimization, slow steaming, and the implementation of energy-saving devices. However, the long-term reduction targets would be difficult to achieve without transitioning to alternative fuels. Therefore, fuels such as liquefied natural gas (LNG), methanol, hydrogen, and ammonia are being considered to replace fossil fuels.

In the short term, LNG and methanol have certain advantages, as most ships are now built with the capacity to operate on these two fuels [10]. In the long term, ammonia and hydrogen are considered strong candidates for achieving complete carbon reduction. These four alternatives have unique characteristics when used as marine fuels. LNG exhibits cryogenic properties. In the event of a leak, it poses risks of explosion and fire, brittle fracture, and asphyxiation [11,12]. To prevent these hazards, storage tank insulation must be reinforced, and additional equipment is required to prevent low temperatures, fires, and explosions [13]. Methanol is a flammable liquid that poses a risk of explosion and is toxic when inhaled. Owing to these hazards, vessels must be adequately equipped with special internal coatings and ventilation systems, along with gas detection and shut-off devices, and flammable zones must be designated [14,15]. Ammonia has low flammability but is highly toxic and corrosive, and mass exposure can damage the hull and even cause loss of life [16]. Consequently, double barriers and piping are required, along with high-efficiency ventilation and detection equipment and automatic shutoff systems [17,18]. Hydrogen has an extremely wide flammability range, is ultralight, disperses rapidly into the atmosphere, and exhibits cryogenic properties, posing a high risk of explosion upon leakage. These characteristics necessitate the use of insulated tanks, gas detectors, and emergency ventilation systems; the isolation of hazardous zones; and the installation of explosion and safety sensors [19,20,21,22].

Each type of alternative fuel has unique advantages and disadvantages [23,24,25] and distinct characteristics, necessitating specialized vessel structures and equipment. Consequently, the associated additional capital expenditures and operating costs vary significantly. This complicates decision-making for several stakeholders in the shipping industry. In particular, during shipbuilding, maritime transport operators are faced with decisions that will profoundly affect their companies’ profitability for decades. Therefore, most research on alternative fuel conversion has largely focused on economic viability and regulatory compliance from the perspectives of shipowners, policymakers, and shipyards.

The transition to alternative fuels necessitates that seafarers, as on-site operators, demonstrate the understanding, proficiency, risk perception, and regulatory compliance required to safely introduce and use these fuels, as they are directly exposed to potential hazards during ship operation. To ensure the safety of crew members, the IMO has proposed various interim measures for handling alternative fuels [26,27,28,29]. Therefore, it is crucial that decision makers at the companies and organizations responsible for shipbuilding and operation understand the degree of crew acceptance and safety awareness regarding alternative fuel use. Nevertheless, studies analyzing the perceptions and attitudes of seafarers—the actual users at the forefront of the transition to alternative fuels—remain relatively scarce. Seafarers’ perceptions of and attitudes toward eco-friendly conversion are important. Developing strategies that include active participation and education can ensure the sustainability of decarbonization [30,31].

Specifically, how seafarers’ perceptions of fuels with varying technological maturity and risk profiles, such as LNG, methanol, ammonia, and hydrogen, differ and whether these differences correlate with resistance or facilitation of the adoption of alternative fuels have not yet been systematically determined.

Thus, in this study, the factors and relationships associated with seafarers’ acceptance of the transition to alternative fuels were empirically analyzed using an established model—the technology acceptance model (TAM)—pertaining to technology adoption. Differences between the fuel categories were examined through group comparisons, through which it was observed that the theoretical structure demonstrates different path strengths and directions depending on the fuel type. The TAM posits that users’ attitudes toward a specific technology are formed according to perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU), which then influence user behavior [32,33]. The TAM is a perception survey targeting actual technology adopters, and most discussion has centered on practical technology users. For these reasons, the TAM has been widely used in information technology adoption research, where technology is accepted relatively easily at the general user level [34,35]. As information technology has advanced, this model has been extended and applied to healthcare-related research [36,37,38], commercial transaction studies related to IT development [39], and mobile-related research [40]. A recurrent theme in these studies is the tendency to prioritize empirical investigations of technology users. The technological transition in the shipping industry also necessitates an approach from this perspective. Seafarers can be considered the end users of new technologies in the shipping sector, rendering them suitable for the application of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Consequently, an analysis of research related to the transition to alternative fuels in the shipping industry through a seafarer-centered Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) can be expected to yield structural similarity and scalability.

Application of the TAM has been limited in the maritime sector, where it is primarily used in studies on autonomous navigation [41,42], and there has been a lack of focus on technologies for converting ships to alternative fuels. Moreover, research involving seafarers—the actual users of the technology—has been insufficient. As seafarers’ safety awareness and risk perception are essential to the application of new technologies in the maritime sector, this research is particularly important [43,44,45]. Therefore, we incorporated risk factors that represent important variables in real ship-operating environments into the general TAM. We comprehensively investigated how the transition to alternative fuels affects the technology acceptance of seafarers using an expanded TAM that incorporates risk perception. In particular, the technical acceptance of alternative fuel systems by seafarers in the marine engineering field influences improvements in the technology’s reliability, safety, and efficiency. Moreover, since many alternative fuels require separate control interfaces, operating rules, or risk mitigation procedures, evaluating user-level acceptance can also contribute to the system’s engineering implementation. Therefore, this study provides theoretical insights into technology in this field and contributes to the adoption of timely, human-centered technology acceptance strategies. This enables strategic and policy improvements toward achieving net-zero goals.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Global Policy and Regulatory Frameworks for Alternative Fuel Transition

The IMO aims to achieve net-zero carbon emissions from shipping by 2050 through its revised GHG reduction strategy, which was adopted in 2023. To this end, the IMO views the global introduction of alternative fuels and energy sources for shipping as essential and expects all types of fuels to be considered [6]. Indeed, the IMO anticipates that the adoption of alternative fuels will account for 64% of the total carbon reduction achieved by 2050 [46]. The IMO recognizes that this target will not be accomplished through technical policy regulations alone. Thus, the need for measures that encompass technological and economic elements has increased. Accordingly, although the 83rd session of the Marine Environment Protection Committee initially intended to approve and implement the revised MARPOL (International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships) Annex VI—which introduces a net-zero framework incorporating economic measures—the decision was postponed for one year at the second extraordinary session, and the future implementation plan will be reconsidered [47]. Despite ongoing debates over the economic implications of these alternative fuel–related policies, the IMO is still expected to advance their implementation. Notably, this regulation extends the scope of carbon-emission measurements to include the production and supply stages of fuel, making it similar to the EU’s FuelEU Maritime Regulation. Therefore, it is expected to accelerate the shipping industry’s transition to alternative fuels for decarbonization.

In 2024, the EU began including all ships over 5000 gross tons in the EU Emissions Trading System, mandating the submission of carbon allowances and aiming to achieve 100% coverage of reported emissions in 2027 [48]. Driven by these regulatory changes, orders for newbuilds using alternative fuels increased by 38% in 2024 compared with the previous year, extending beyond LNG-powered vessels to include orders for ammonia-fueled ships [49].

2.2. Technological Measures and Seafarer Acceptance in the Transition to Alternative Fuels

In order to achieve the IMO’s net-zero goals, the shipping industry is implementing various measures more proactively than other sectors. This is partly because the efficient use of energy for carbon reduction can support economic efficiency in addition to helping achieve carbon targets. The implementation of these carbon reduction measures can be categorized according to the temporal parameters of the project.

First, there are measures that can be implemented in the short term. A prime example of a short-term measure is the introduction of optimization approaches that utilize digital technology. A range of big data analysis methods is being implemented to manage ship energy efficiency and predict pollutant emissions. The combination of intelligent algorithms and machine learning has been demonstrated to enhance predictive performance and improve energy efficiency [50]. It is anticipated that advancements in technological capabilities, encompassing these digital technologies, will engender efficiency gains in technical and operational domains, including operational efficiency [51], energy efficiency [52], power system efficiency [53], and hull efficiency [54]. The evaluation of such efficiency improvements is primarily conducted on a short-term basis because these measures can be implemented immediately. It is evident that the IMO’s short-term measures, EEXI and CII, also focus on this aspect.

In the medium term, measures to implement include the application or ongoing development of liquefied natural gas (LNG), methanol, biofuels, support for wind power, and the electrification of ships. The analysis of long-term measures is primarily focused on the utilization of hydrogen, ammonia, nuclear power, and carbon capture technologies [55]. The rationale behind this assertion is that the carbon reduction capacity of short-term measures is limited. Consequently, in addition to technical and operational measures, the mid-to-long-term transition to alternative fuels is an essential means of achieving the IMO’s net-zero goal [56].

Among alternative fuels, LNG, methanol, hydrogen, and ammonia are considered to be of particular significance. Nevertheless, there are still deficiencies in the realm of safety management technologies for these fuels, which have a direct impact on the well-being of crews and the preservation of the environment in the context of the transition to alternative fuels [57]. Although awareness of seafarers’ acceptance of technology is crucial in decisions related to this transition, there is a risk that this group may be marginalized when such decisions are made [58]. Indeed, an analysis of seafarers’ awareness regarding climate change revealed that they have a low level of understanding about international policy changes related to climate change, indicating that efforts are needed to increase their awareness [59]. In particular, even during the implementation of short-term energy efficiency measures such as SEEMP, seafarers experienced technological changes and demonstrated efforts to achieve company goals, despite the fact that financial incentives and other benefits were found to be severely lacking [60]. Financial incentives for energy efficiency and low-carbon shipping have been identified as potential motivation for seafarers to actively participate in these policy changes. Educational level has also been identified as a significant factor in participation [30].

2.3. Components of the TAM

Anchored in the concepts of PU and PEOU, the TAM is a framework for understanding technology acceptance. PU refers to the degree to which a user believes that using a particular system will enhance their performance, whereas PEOU refers to the degree to which a user believes that using a particular technology will require little effort [32]. PEOU directly influences PU, and they jointly influence attitude. Changes in attitude can alter BI, revealing the degree of technology acceptance. The TAM has generally been used to study the adoption of new, previously unavailable technologies, such as the Internet and digital services [61,62]. Recently, with the integration of fintech and technological changes in banking systems, the TAM has been widely applied to assess the adoption of digital banking system technologies [63,64]. Furthermore, with increasing environmental concerns and eco-friendly policy trends demanding diverse technological changes, the TAM has been applied to adoption of technologies related to energy use by various stakeholders [3,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75].

In the shipping sector, the TAM has been applied to autonomous navigation—a next-generation technology [42]. It is also being applied to technological changes driven by digital transformation in the logistics sector, including shipping [76,77]. Efforts are being made to apply the TAM across all fields related to technological change to assess the degree of technology acceptance among users.

2.4. Risk and Trust Constructs

Seafarers are exposed to various risks while onboard a ship and using fuel. Alternative fuels adopted for decarbonization carry greater risks than conventional marine heavy fuel oil in certain circumstances. Uncertainty regarding the risks associated with alternative fuels may require incorporating trust and risk factors into the TAM [39]. Trust has been used as a key factor influencing the acceptance of online commerce technologies, such as those relating to e-commerce and IT [78,79]. Similarly, trust is crucial to the adoption of new and sustainable energy technologies [66,80]. Therefore, trust factors need to be incorporated into the TAM to understand seafarers’ adoption of alternative fuel technologies. Users’ risk perceptions are also important. Models incorporating risk perception factors have primarily been applied to the Internet and mobile systems to analyze the perceived risks associated with potential hazards arising from using these technologies [39,73,75,81]. Variables related to each individual’s risk have been modified and used in each model. Generally, perceived risk is considered to indirectly influence acceptance intention through mediating variables [80]. This study aimed to construct a model by distinguishing risks rather than using integrated perceived risk perception.

2.5. Trends in Research on the Acceptance of Energy Conversion Technologies

Research on the acceptance of technologies related to energy conversion, including alternative fuels, has undergone various developments. In general, these studies have focused on areas in which consumers have relatively broad decision-making authority, with vehicle fuel conversion technologies being a representative example. Accordingly, studies applying the TAM have primarily analyzed factors influencing the adoption of new energy conversion technologies for vehicles [68,70,75]. Some of these studies have also extended the basic TAM constructs by incorporating esthetic, functional, and symbolic components that reflect the preferences of consumers [70]. Consistent with typical TAM findings, PU and PEOU were found to have positive effects on attitude and behavioral intention, whereas perceived risk exerted a negative effect.

Research on alternative fuel technologies has expanded beyond this consumer-oriented vehicle domain into energy management and infrastructure technologies, including hydrogen, biofuels, battery storage systems, and smart grid technologies [72,73]. While these studies demonstrated results similar to those attained with conventional TAM frameworks, some [73] suggested that risk perception should be interpreted based on consumer risk profiles rather than simply minimized.

Researchers have also begun to explore technology acceptance for alternative fuel applications within specific industries, such as agricultural machinery [74]. At the same time, the research has broadened to encompass energy conversion across the transportation sector [3,65]. These studies generally examine technology acceptance from the perspective of stakeholders involved in alternative fuel transitions rather than ordinary consumers. Notably, in the case of shipping research [3], unlike typical TAM findings, risk perception was found to positively influence PU—indicating that awareness of potential risks may enhance the perceived value of adopting alternative fuels by highlighting the scope for improvement within a specialized field. Building on these prior studies, this research focuses on seafarers, who comprise one of the key stakeholder groups in this specialized domain. The relevant studies and key factors influencing the acceptance of energy conversion technologies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of technology acceptance studies in energy conversion.

3. Research Model and Method

3.1. Research Process

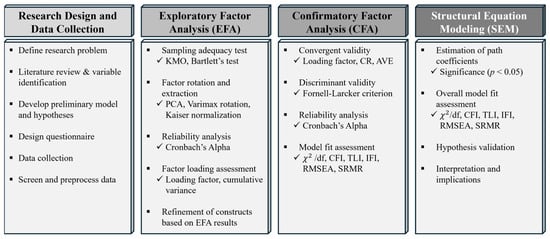

In this study, we constructed an extended TAM through the research process illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Research process for developing the extended TAM framework.

In the first step, we conducted a multifaceted review of prior TAM-related research to identify conceptual constructs and develop a research model for the study design. Hypotheses were formulated based on the derived constructs, referencing hypotheses validated in prior studies. The questionnaire referenced existing items measuring TAM constructs, while risk perception factors related to alternative fuel characteristics were developed by the research team based on prior studies. The survey was conducted online, and basic preprocessing for data analysis was performed.

In the second step, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to assess the heterogeneity of the newly added construct and refine the items. After confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis via KMO and Bartlett’s tests, factors were extracted using Varimax orthogonal rotation. Subsequently, items with factor loadings below the threshold were removed.

In the third step, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed by integrating the construct concepts derived from the EFA with the existing TAM factors. The appropriateness of the construct concepts was verified through content validity, discriminant validity, and internal consistency. This process enabled use of the construct concepts in structural equation modeling.

In the fourth step, the adequacy of the model established in the first step was verified, and the significance of each path coefficient for hypothesis testing was assessed. This determined whether hypotheses were accepted or rejected, and academic and practical implications were derived based on the level of hypothesis acceptance.

3.2. Research Model and Hypotheses

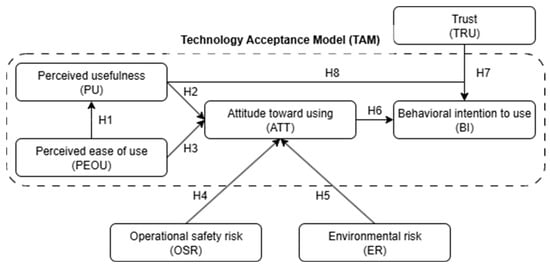

This study adopted the TAM as a fundamental framework to explain seafarers’ acceptance of alternative fuels [32]. The TAM assumes that PU and PEOU influence an individual’s attitude toward the technology (ATT) and BI. Its explanatory power is enhanced by extending these core components with the addition of elements tailored to various conditions [79]. Therefore, referencing existing research, we expanded the existing model by adding trust and risk factors to establish our research model (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed research model.

PEOU, a core component of the TAM, is positively correlated with PU, and both components are expected to positively influence ATT. Accordingly, we formulated hypotheses H1–H3 (Table 2). Regarding H1, the higher the PEOU of the system, the higher its PU. This is because the less additional training is required to switch to an alternative fuel, the higher the PU of the fuel is among crew members. Regarding H2, PU is a key determinant of ATT because the more crew members perceive the transition to alternative fuel as changing their work and as a good method of achieving carbon-reduction goals, the more positive their attitude will be. Furthermore, regarding H3, the higher the PEOU of an alternative fuel is among crew members, the more positive their ATT will be.

Table 2.

Summary of research hypotheses and structural paths.

The newly adopted alternative ship fuels present distinct safety and environmental risks compared with conventional fuels [82]. As previously discussed, models that incorporate perceived risk into the TAM framework defined and utilized various perceived risks according to the research topic [73,75,83]. However, previous studies did not identify an appropriate conceptual framework for the risks associated with alternative fuels. Therefore, this study categorized the risks arising from the use of alternative fuels according to two distinct elements: operational safety risk (OSR) and environmental risk (ER). These two concepts align with the IMO’s primary objectives of ensuring the safety of ships and human life and preventing marine pollution. Operational safety risks (OSRs) occur where alternative fuels directly impact seafarers. They encompass not only health hazards for seafarers but also operational risks stemming from damage to hulls and machinery. These factors are particularly important because seafarers may find it difficult to distinguish between the risk of damage and risks to human health associated with alternative fuels.

Beyond these direct risk concepts, indirect environmental risks also need to be considered. Although alternative fuels are highly environmentally friendly in terms of carbon emissions, they may not have favorable impacts on the marine environment and its organisms. Therefore, crew members may recognize that indirect environmental risks exist for some alternative fuels. Consequently, we considered the environmental risks (ER) of alternative fuels in relation to environmental pollution to reflect these aspects. While each concept can be expressed as a single perceived risk, understanding how each risk component influences ATT is crucial. Accordingly, each risk factor was expected to act as a deterrent to the formation of attitude. Thus, we formulated H4 and H5, pertaining to factors that exert a negative influence on ATT.

Based on the fundamental structure of the TAM, in which ATT is influenced by PU, PEOU, OSR, and ER directly mediates BI, ATT positively influences BI, leading to H6. The primary predictor of behavior is behavioral intention, which mediates the influence of attitude on behavior [84,85].

Additionally, referring to prior research, we expanded the concept of trust (TRU) to reflect concerns about the safety of alternative fuels [42,78,79,86,87,88]. Although various studies have indicated that trust influences the four components of the existing TAM (PU, PEOU, ATT, and BI), we established H7 based on the expectation that the actual BI will change directly based on the trust felt by individual users. We established H8 based on the expectation that PU, independent of mediating ATT, would directly influence BI if the actual utility of transitioning to alternative fuel was judged to be high, regardless of attitude.

3.3. Method

This study used a cross-sectional online survey to collect data for quantifying seafarers’ acceptance of alternative fuels. A purposive sampling design was considered suitable for the study’s research objectives and adopted as the sampling strategy. The study population was defined as Korean seafarers with onboard experience. The Republic of Korea is an optimal context for investigating seafarers’ perceptions of alternative fuels, given its status as a nation with a high proportion of green vessel construction and one of the largest operating fleets of such vessels. The survey was conducted from April to July 2025, resulting in a total of 232 responses. To ensure the reliability and integrity of the data, the collected questionnaires were rigorously screened. Completed surveys exhibiting patterns of careless responses, such as straight-line responses and inconsistent answers on reverse-scored items, were subsequently removed. Consequently, 219 valid samples were retained and utilized for analysis. The program used for the analysis was IBM SPSS Amos 30.

To scale the responses, all survey items except demographic questions were divided into alternative fuel categories (LNG, methanol, ammonia, and hydrogen) and measured using a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Reverse-scored items were used to ensure reliability. The alternative fuel group reflected opinions of LNG and methanol, fuels that are actively used in the global shipping market in the short term, and carbon-free fuels (hydrogen and ammonia) that align with the IMO’s long-term GHG-reduction strategy. Consequently, the inclusion of LNG, methanol, ammonia, and hydrogen considered both short-term feasibility and long-term net-zero alignment. As this fuel portfolio represents industry adoption trends, infrastructure progress, and technology commercialization stages, it was a valid choice for comparatively analyzing seafarers’ TAM-based acceptance mechanisms. By structuring the survey items according to each fuel type, we compared and measured factors of seafarers’ technology acceptance for each fuel. This enabled us to assess seafarers’ technology acceptance levels for alternative fuels from the present to the medium and long term, along with their risk perceptions.

The model’s constructs were designed based on standardized questionnaires derived from existing TAM-related research. Key risk-related constructs were estimated based on the major risk factors associated with each alternative fuel, and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to assess their appropriateness (see Appendix A for the details of the latent constructs, observed variables, and questionnaire items).

The prerequisites for the explanatory factor analysis were assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (KMO ≥ 0.80 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity p-value < 0.05 across all fuel groups) [89]. Varimax rotation, an orthogonal method, was employed to maximize the variance of factor loadings, thereby facilitating clearer factor interpretation and minimizing cross-loadings [90]. This rotation was appropriate since the two factors used in the EFA are conceptually distinct and assumed to be uncorrelated. Kaiser normalization was also applied to reduce bias from items with high communalities and enhance the stability of factor loadings [91].

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on the risk scale refined by EFA and all Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) constructs to assess convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability. Convergent validity was confirmed by checking the significance of the standardized factor loadings (λ ≥ 0.50 recommended), Average Variance Extracted (AVE ≥ 0.40), and Composite Reliability (CR ≥ 0.70) [92]. Discriminant validity was verified using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, a classical and rigorous method in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) that ensures that each latent variable measures a distinct concept, requiring that the square root of the AVE for each construct is greater than its correlation with all other constructs [92,93].

The model fit for the CFA model was evaluated using the same indices as the SEM: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), with recommended cutoffs of CFI, IFI, TLI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA, and SRMR ≤ 0.08 [92,94].

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method, applying Covariance-Based SEM (CB-SEM). All latent variables were modeled as reflective constructs. For scale identification, the factor loading of the first indicator (item) for each latent variable was fixed to 1. The path coefficients were reported as standardized estimates (β). Significance was determined according to the critical ratio and the p-value. The model fit for the SEM was evaluated using the same indices as the CFA: the CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR.

Hypothesis testing was performed based on the standardized path coefficients and the CR of the structural model. For the corresponding path of each hypothesis (H1–H8), β, standard error, CR, and p-value were reported. A hypothesis was deemed supported if the p-value was less than 0.05.

Furthermore, to investigate the perceived differences across fuel types, a separate SEM analysis was conducted for each fuel type (LNG, methanol (MET), ammonia (AMM), and hydrogen (HYD)) to compare the path coefficients.

4. Results

Table 3 presents the respondents’ demographic profiles. Male respondents constituted the majority at 214 (97.7%), with 5 female respondents (2.3%). This aligns with the male-dominated composition of the global seafarer workforce, which is consistent with the 1.2% proportion of female seafarers worldwide reported by the BIMCO (Baltic and International Maritime Council)/ICS (International Chamber of Shipping) in 2021 [95]. Those under 30 years of age comprised the largest age group, with 95 participants (43.4%), followed by 51 participants (23.3%) aged 30–39 years, 33 (15.1%) aged 40–49 years, 27 (12.3%) aged 50–59, and 13 (5.9%) aged 60 years or older. In terms of service experience, 74 individuals (33.8%) had 3–5 years of service, 49 individuals (22.4%) had less than 3 years, 40 individuals (18.3%) had 5–10 years, 31 individuals (14.2%) had 10–20 years, and 25 individuals (11.4%) had more than 20 years. Junior officers/junior engineers (operational level) constituted the largest group at 114 respondents (52.1%), while there were 23 captains (10.5%), 49 chief officers/first engineers (22.4%), 27 chief engineers (12.3%), and 6 others (2.7%). The sample primarily comprised officers and engineers responsible for the practical implementation of alternative fuel usage, making it appropriate for assessing their awareness of relevant practices. This sample has a limitation in that it does not reflect the perceptions of support-level seafarers regarding alternative fuels. However, it is better suited for investigating risk perception concerning alternative fuels as it is primarily composed of navigating and engineering officers, including master and chief engineers, who bear direct responsibility for vessel safety and marine pollution prevention. Furthermore, the ranks included in the sample are generally aligned with both the operational and management levels of most vessels, indicating a well-structured representation.

Table 3.

Respondents’ demographic profile (N = 219).

The two risk constructs presented in this study—OSR and ER—are newly proposed concepts. EFA was conducted to measure the number of factors and the explanatory power of the construct concepts. The initial EFA was conducted using all observed variables for each fuel type. The analysis revealed that the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin values for all four fuels exceeded the criterion KMO ≥ 0.80, indicating that the correlation among variables was adequately explained by common factors [89]. However, the items OSR1 and OSR7 were removed as they failed to meet the specified factor loading criterion (λ ≥ 0.50) [65]. Following the removal of these items and the execution of a factor analysis, the results were classified according to two concepts, as shown in Table 4. Items 1 and 2 in Table 4 represent the components separated by the factor analysis. These distinct components correspond to the two risk concepts proposed in the model. In the EFA by fuel type, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value ranged from 0.802 to 0.821 (KMO ≥ 0.80), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant for all (p < 0.001), indicating suitability for factor analysis [89]. In factor analysis, the total variance should be explained by at least 60% of the rotation sums of the squared loadings [96]. This was confirmed across all fuel groups, indicating that the variables sufficiently explained the overall factors. An analysis to validate this concept suggested that in the context of introducing alternative fuels, the risks associated with alternative fuels comprise OSR, representing physical and human safety risks, and ER. This provided theoretical grounds for subsequent structural equation modeling to verify the relationship between each risk and ATT.

Table 4.

Exploratory factor analysis results.

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis conducted to validate each factor structure used in the analysis are presented in Table 5. The model incorporates the construct concepts PU, PEOU, ATT, BI, and TRU from the extended TAM alongside the risk concepts OSR and ER, which were identified through exploratory factor analysis. The beta values (standardized regression weights) for each construct concept, along with the average variance extracted (AVE), construct reliability (CR) for confirming convergent validity, and Cronbach’s alpha values for confirming internal consistency reliability, are presented for each of the four fuels. While most variables from the existing TAM fit their respective components, some variables from PEOU lacked sufficient validity and were therefore removed. Cronbach’s values for reliability measurement showed PEOU at 0.674 for methane fuel, while all other components demonstrated high reliability above 0.7. This value is above the commonly used threshold of 0.6, so it was used in the analysis [97]. The average variance extracted (AVE) values also exceeded 0.5 for all components except OSR, and construct reliability (CR) was adequate at 0.7 or above for all components [93]. Although the AVE value for OSR was somewhat low, CR was above 0.6. As the AVE criterion is relatively strict, an evaluation solely based on CR suggests that it is acceptable as a component [93,98,99]. The model demonstrated an acceptable level of fit, with all fit indices meeting the recommended thresholds.

Table 5.

Confirmatory factor analysis results.

Table 6 presents the correlations confirming the degree of association between the components and their discriminant validity. Although some variable correlations were relatively high, they corresponded to relationships already theoretically established in the TAM. Furthermore, as each correlation coefficient was smaller than the square root of the AVE diagonal matrix, discriminant validity could be presumed to exist [93,100].

Table 6.

Correlation test results.

Table 7 presents the model fit indices for each alternative fuel model. The , Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) are absolute fit indices that comprehensively verify the goodness-of-fit of the model. The values ranged from 1.885 to 2.142 and were all below the conventional threshold of 3 [101]. The RMSEA measures the magnitude of the population approximation error while considering model parsimony. The SRMR measures the average of the model’s standardized residuals. RMSEA values ranged from 0.66 to 0.72, and SRMR values ranged from 0.06 to 0.08, indicating an adequate fit. The Incremental Fit Index (IFI) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) were used to evaluate the degree to which the model developed in the study is an improvement compared to the most restricted null model (baseline model) that assumes zero correlation among all observed variables. The Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) aids in finding a parsimonious model by imposing a penalty for model complexity. The IFI, TLI, and CFI values were all above 0.9 [94,102,103].

Table 7.

Summary of model fit measures.

Table 8 presents the path coefficients and critical ratios for the structural equation model for each fuel in the hypothesis. When a path coefficient is statistically significant, it indicates a substantial influence of the path between the corresponding constructs. First, H1, H2, and H3 showed significant positive effects across all fuel types, consistent with the results of previous TAM-related studies. For H1, the coefficients of methanol (0.726) and LNG (0.707) were notably large: as experience with these two relatively short-term fuels accumulates, their PEOU strongly influences their PU. Therefore, the practical usefulness of short-term alternative fuels is expected to increase as procedures are simplified and requirements, such as crew training, are reduced. H2 and H3 showed positive relationships, but H3’s coefficient (0.607–0.684) was higher than that of H2 (0.352–0.414). Thus, ease of use exerts a greater influence on seafarers’ attitudes toward adopting eco-friendly technologies than usefulness. In particular, LNG and methanol, despite being relatively familiar, significantly influenced attitude improvement based on ease of use.

Table 8.

Structural equation modeling results.

Regarding H4, operational safety risk showed a significant positive influence on attitude toward all alternative fuels, yielding results contrary to the hypothesis—that is, perceived level of risk has a positive effect on attitude. This finding is at odds with the majority of extant research; however, it is in alignment with several prior studies suggesting that heightened risk awareness may engender positive attitudes, safe behaviors, and information seeking driven by the expectation that risks will be mitigated [3,38,104,105]. Thus, seafarers may tend to adopt a more positive attitude, as they likely assume that the higher the risk, the greater the necessity of using that fuel. Notably, the coefficients for long-term fuels, such as hydrogen and ammonia, for which risks may be uncertain, were higher. This could be interpreted as the result of higher risk perception increasing expectations for improved procedures and equipment. Regarding H5, change in attitude related to ER was not significant for most fuels, with only hydrogen showing a negative effect, thus supporting this hypothesis. Although hydrogen is generally associated with clean energy, seafarers first recognize concerns about the environmental damage caused by explosive combustion due to hydrogen leaks, which can negatively affect their attitudes.

H6 and H7 significantly influenced BI. Ammonia exhibited the highest coefficient in H6, indicating strong future BI following an attitude change. Conversely, LNG, the most widely adopted alternative fuel, had a low coefficient of 0.386, suggesting a minimal impact on the formation of attitude-based BI. Regarding the influence of trust on BI in H7, similar levels of impact were observed, although hydrogen had the highest coefficient at 0.344. Similarly to H5, although seafarers perceive hydrogen as somewhat hazardous, increased trust could lead to the most significant change in their BI. Finally, contrary to our hypothesis, none of the factors in H8 were significant; thus, usefulness alone does not translate into actions on the part of seafarers and must be accompanied by attitude changes and perceived reliability.

5. Discussion

This study assessed seafarers’ levels of technology acceptance of alternative fuels based on a modified TAM, which identified perspectives on technology adoption. Specifically, our model analyzed and compared various alternative fuels (i.e., LNG, methanol, ammonia, and hydrogen), which have been introduced in response to recent IMO carbon and air pollution regulations. The IMO is implementing short-, medium-, and long-term measures to reduce carbon emissions. The transition to alternative fuels is considered the most effective method in the medium to long term. The most suitable fuel for each period may change; however, the development of associated technologies and deployment are gradually progressing. This leaves seafarers with no choice but to adopt technologies in stages. Owing to the difference in characteristics between alternative and conventional fuels, seafarers’ participation in their adoption is crucial for future carbon-reduction objectives.

Our results showed that all basic pathways of the TAM yielded significant results, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies. In particular, for short-term transition fuels, such as methanol and LNG, ease of use was strongly associated with PU. This result is consistent with those of previous studies, showing that the more user-friendly a technology is, the more useful it is perceived to be by actual users [3,35,38,39,40,62,69,71,73,79]. As in existing prior studies, both PU and PEOU were found to have a positive influence on ATT [38,42,69,74,79]. In particular, while some studies [37,71] have reported that PEOU has no significant impact or even a negative impact on ATT, suggesting that it may not be decisive for technology adoption, this study revealed that PEOU exerts a greater influence on ATT than PU. Thus, continuous technological improvements are necessary for operational convenience.

Interestingly, operational safety risks had a significant positive effect across all fuels. This finding contradicts the majority of studies indicating that risk perception negatively affects attitudes or intention [39,73,75,83,86]. However, some studies suggest that as perceived risk increases, the expectation that technological risks will be mitigated can have a positive influence on attitudes [3,38,104,105]. The perception of risk itself, rather than the risk level, drives positive attitude changes because, as ship technology generally evolves conservatively, the existence of risks may be perceived as necessitating special usage requirements for a technology’s application. Additionally, the risks associated with alternative fuels, which demand higher levels of education and knowledge, may induce proactive attitudes, such as the incentive to participate in additional tasks [106]. In other words, from the seafarer’s perspective, risk perception can actually have a positive influence on attitude.

However, changes in attitude due to ERs were mostly insignificant, with only hydrogen negatively affecting attitude. Seafarers generally perceive all alternative fuels to be environmentally friendly, which makes it difficult to observe significant changes in their attitude towards environmental pollution and the damage it causes. However, heightened awareness of risks, such as hydrogen explosions, has led to negative attitudes towards the environmental pollution caused by such incidents [107]. As expected, ATT had a positive influence on BI [37,38,42,65,69,71,78,79]. Therefore, efforts are needed to encourage positive changes in attitude toward the adoption of technology. Furthermore, TRU had a positive influence on BI, which aligns with prior studies and confirms that trust is crucial to technology adoption [42,79,80]. Therefore, establishing transparent trust in technology is vital for institutional change. Finally, PU did not significantly influence BI, an outcome that differs from prior research [35,37,39,40,42,62,65,66,67,76,79]. This means that the behavior of seafarers, as the end users of alternative fuels, did not change due to the perceived usefulness of the fuels. In other words, the usefulness of alternative fuels can be considered to affect behavioral intent not by changing it directly but by mediating behavior through changes in attitude. This suggests that since seafarers have limited choice in using alternative fuels, technology adoption occurs within restricted parameters through changes in attitude rather than behavioral intent.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary of Key Findings

This study examined seafarers’ acceptance of alternative fuel technologies following the introduction of alternative fuels, which is one of the most significant changes in the shipping industry at present. To this end, the TAM, which assesses the acceptance of novel technological changes, was used to compare and analyze seafarers’ perceptions of each alternative fuel, yielding the following results.

First, the basic pathways influencing TAM attitudes (H1, H2, and H3) were significantly validated for all fuels analyzed. Notably, the influence of ease of use on attitude formation was greater than that of usefulness. This indicates that, during the process of accepting alternative fuels, crew members may adjust their attitudes based more on the convenience of actual operation than on the usefulness of a specific alternative fuel. Changes in attitude based on ease of use require crew members to perceive the transition to alternative fuels as straightforward. However, many alternative fuels require additional training due to regulations, such as the IGF Code. This is likely to act as a barrier to the adoption of alternative fuel technology. Therefore, foundational training related to these regulations must be prioritized at basic maritime training institutions. Providing early foundational training will lower barriers to subsequent advanced training. Standardizing foundational technologies for alternative fuel conversion would reduce the training burden on companies and institutions responsible for advanced education while also contributing to the effective allocation of resources.

Second, OSR had a positive influence on attitude; recognizing and accepting risks as manageable contributed to the formation of positive attitudes among crew members. This phenomenon was particularly pronounced for long-term fuels, such as hydrogen and ammonia, which have relatively low usage levels but potentially uncertain risks. This finding suggests that risk perception may enhance expectations of safety, which in turn can positively shape attitudes toward the adoption of new technology. The working environment of seafarers is highly hazardous, but they are accustomed to managing risk effectively. This remains true even for additional risks arising from the transition to alternative fuels. Seafarers have high confidence in risk management thanks to the meticulous identification of risk factors during the assessment phase. Therefore, current temporary risk management regulations must be strengthened to establish systems and procedures capable of identifying a broad range of risk factors. If seafarers perceive the risks of alternative fuel conversion to be manageable, their attitudes will become more positive.

Third, ER had a weak influence, in general, but a negative effect in the case of hydrogen. This indicates that despite the inherent cleanliness of hydrogen, the potential for emergency situations to result in environmental damage and harm negatively influences the attitudes of crew members. Therefore, to introduce hydrogen fuel, it is necessary to emphasize its cleanliness and provide education and technological improvements to minimize environmental damage and enhance crews’ accident response capabilities.

Fourth, attitude and trust, which are elements of the TAM, emerged as key determinants of BI. Notably, for ammonia, attitude exerted the strongest influence on BI, whereas for hydrogen, TRU had the most prominent effect. Thus, shifting attitudes and building trust are critical to the acceptance of these long-term fuels. Over the years, the IMO and governments worldwide have established a variety of safety systems and continuously revised regulations. This feedback has been documented and systematized, particularly with the introduction of the ISM Code. Through this process, seafarers have developed a great deal of trust in the system. Therefore, it is crucial that policymakers and educational institutions do not undermine this trust, which requires dedicating significant effort to education and promotion to maintain. After policy formulation, systems such as the port state control (PSC)’s concentrated inspection campaigns (CICs) should also be actively utilized.

Finally, PU itself was not directly related to BI. Thus, PU alone does not determine seafarers’ BI; rather, changes in ATT based on PEOU and PU are important.

In conclusion, strategies for the adoption of alternative fuel technologies are ineffective if they remain confined to promoting utility. Improving ease of use, developing risk-management systems and technologies, and ensuring reliability are crucial factors in shaping seafarers’ attitudes and BI. This has important implications for establishing practical policies in the shipping industry, such as designing education and training programs, strengthening safety devices and procedures, and establishing institutional frameworks to guarantee safety.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations. With regard to the adoption of alternative fuel conversion technology, the shipping industry involves various stakeholders. Although seafarers are the end users, the roles determining their actual usage can vary. It is necessary, then, to expand the research scope to include decision makers in shipping companies and shipyard personnel and to diversify the nationalities of the seafarers surveyed. Expanding the stakeholder base will also require incorporating additional components into the model. For example, changes may occur based on factors such as financial considerations, route decisions, cultural variables, and port selection. Future research should adopt a multidimensional approach to overcome these limitations. Specifically, conducting longitudinal studies over extended periods would enable detailed observation of how each stakeholder’s perception evolves in response to technological change. By conducting comparisons between countries based on the expanded sample, it is also possible to determine whether there are actual differences in awareness regarding the transition to alternative fuels among seafarers across nations.

Nevertheless, this study is significant in terms of identifying the degree of acceptance of alternative fuel conversion technologies by seafarers, who are the actual users of the technology. Since the pace of technology adoption by seafarers will determine the extent to which medium- to long-term goals for alternative fuel conversion are achieved, this research is fundamental to achieving carbon reduction targets. Through this analysis, a theoretical and empirical foundation for designing carbon reduction policies is established.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K., D.L. and C.-h.L.; methodology, D.L.; software, D.L.; validation, K.K., D.L. and C.-h.L.; formal analysis, K.K. and D.L.; investigation, D.L. and C.-h.L.; resources, D.L. and C.-h.L.; data curation, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K. and D.L.; writing—review and editing, K.K. and D.L.; visualization, K.K. and D.L.; supervision, K.K. and D.L.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, C.-h.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS), Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) through the Innovation Development (R&D) for Global Regulation-Free Special Zone (grant no. RS-2024-00488440).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATT | attitude toward using |

| AVE | average variance extracted |

| BI | behavioral intention to use |

| CFI | comparative fit index |

| CIC | concentrated inspection campaigns |

| CR | construct reliability |

| EFA | exploratory factor analysis |

| ER | environmental risk |

| GHG | greenhouse gas |

| IGF | international code of safety for ships using gases or other low-flashpoint fuels |

| IFI | incremental fit index |

| IMO | international maritime organization |

| KMO | kaiser–meyer–olkin |

| LNG | liquefied natural gas |

| OSR | operational safety risk |

| PEOU | perceived ease of use |

| PSC | port state control |

| PU | perceived usefulness |

| RMSEA | root mean square error of approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized root mean square residual |

| TAM | technology acceptance model |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| TRU | trust |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Latent Constructs, Observed Variables, and Questionnaire Items with References.

Table A1.

Latent Constructs, Observed Variables, and Questionnaire Items with References.

| Latent Construct | Observed Variable | Questionnaire Item | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PU | PU1 | Using the alternative fuel system is useful for environmental compliance tasks. | [32,36,37] |

| PU2 | Using the alternative fuel system increases productivity in environmental compliance tasks. | ||

| PU3 | Using the alternative fuel system improves performance in environmental compliance tasks. | ||

| PU4 | Using the alternative fuel system can enable me to accomplish environmental compliance tasks more quickly. | ||

| PU5 | Using the alternative fuel system enhances the effectiveness of environmental compliance tasks. | ||

| PEOU | PEOU1 | I find the alternative fuel system cumbersome to use. (Reverse) | [32,34,35,36,108] |

| PEOU2 | My interaction with the alternative fuel system is clear and understandable. | ||

| PEOU3 | I find it takes a lot of effort to become skillful at using the alternative fuel system. (Reverse) | ||

| PEOU4 | Interacting with the alternative fuel system does not require a lot of mental effort. | ||

| PEOU5 | Learning to operate the alternative fuel system is easy for me. | ||

| ATT | ATT1 | Using the alternative fuel system is a good idea. | [37,109,110] |

| ATT2 | Using the alternative fuel system is favorable. | ||

| ATT3 | Using the alternative fuel system is beneficial. | ||

| ATT4 | I support the use of the alternative fuel system. | ||

| BI | BI1 | Given the chance, I intend to board a ship with alternative fuel system. | [33,37,39] |

| BI2 | Given the chance, I predict that I will board a ship with alternative fuel system in the future. | ||

| BI3 | Whenever possible, I do NOT intend to board the alternative fuel system ship. (Reverse) | ||

| TRU | TRU1 | This alternative fuel system is trustworthy. | [39,86,88] |

| TRU2 | Overall, I can trust the alternative fuel system. | ||

| TRU3 | I trust the safety of the alternative fuel system. | ||

| OSR | OSR1 | The alternative fuels pose a risk of causing malfunctions in the ship’s main equipment. | [12,15,18,19,111,112,113] |

| OSR2 | The alternative fuels pose a risk of damaging the hull if leaked. | ||

| OSR3 | The alternative fuels carry the risk of increasing hull maintenance costs. | ||

| OSR4 | The alternative fuels increase the risk of hull fires/explosions. | ||

| OSR5 | Contact with the alternative fuels may cause personal injury. | ||

| OSR6 | The explosive nature of the alternative fuels poses a risk of causing personal injury. | ||

| OSR7 | The alternative fuels pose a hazard to the respiratory system (asphyxiation, toxicity, etc.). | ||

| OSR8 | I feel unsafe if I do not receive sufficient training on the alternative fuels. | ||

| ER | ER1 | The alternative fuels pose a risk of marine environmental pollution if spilled. | |

| ER2 | The alternative fuels pose a risk of destroying the marine ecosystem if spilled. | ||

| ER3 | Cleanup operations following spills of the alternative fuels are extremely difficult. | ||

| ER4 | The leakage of alternative fuels may pose a risk to the health and activities of coastal residents. |

References

- Enerstvedt, V. Does it Pay to be Green? Investigating Alternative Fuels Impact on Vessel Value. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Bangkok, Thailand, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 1134–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Al Baity, O.A.; Ahmed, Y.M.; Abdelnaby, M.; Elgohary, M.M. Green Fuels for Maritime: An Overview of Research Advancements, Applications, and Challenges. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 2025, 59, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideri, O.; Papoutsidakis, M.; Lilas, T.; Nikitakos, N.; Papachristos, D. Green shipping onboard: Acceptance, diffusion & adoption of LNG and electricity as alternative fuels in Greece. J. Shipp. Trade 2021, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, D.P.; Feetham, P.M.; Wright, M.J.; Teagle, D.A.H. Public response to decarbonisation through alternative shipping fuels. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 20737–20756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N. Towards sustainable maritime transport: Focus on the early phase of technology development related to alternative fuels. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 85, 101686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Resolution MEPC.377(80): 2023 IMO Strategy on Reduction of Ghg Emissions from Ships; IMO: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparotti, C. Alternative marine fuels for cleaner maritime transport. Ann. Dunarea Jos Univ. Galati Fascicle XI Shipbuild. 2024, 47, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Hwang, I.; Jang, H.; Jeong, B.; Ha, S.; Kim, J.; Jee, J. Comparative Analysis of Marine Alternative Fuels for Offshore Supply Vessels. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, F.S.; Araujo, B.M.; Santos, R.S.; Caiado, R.G.G.; Thomé, A.M.T. Wave of Change: Sustainable Fuel Selection in Maritime Operations. In Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics, Proceedings of the Industrial Engineering and Operations Management (IJCIEOM 2024), Salvador, Brazil, 26–28 June 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 483, pp. 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson Research. Shipping & Shipbuilding Forecast Forum Selected Highlights; Clarksons Research: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vandebroek, L.; Berghmans, J. Safety aspects of the use of LNG for marine propulsion. Procedia Eng. 2012, 45, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneziris, O.; Koromila, I.; Nivolianitou, Z. A systematic literature review on LNG safety at ports. Saf. Sci. 2020, 124, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannaccone, T.; Landucci, G.; Cozzani, V. Inherent safety assessment of LNG fuelle d ships and bunkering operations: A consequence-based approach. Chem. Eng. 2018, 67, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, N.R. An environmental and economic analysis of methanol fuel for a cellular container ship. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 69, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritime Knowledge Centre; TNO; TU Delft. Methanol as an Alternative Fuel for Vessels; TU Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pocitarenco, N.; Aneziris, O.; Koromila, I.; Nivolianitou, Z.; Gerbec, M.; Maras, V.; Salzano, E. A Systematic Literature Review on Safety of Ammonia as a Marine Fuel. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2025, 116, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedekar, K.; Oterkus, E.; Oterkus, S. Investigating Challenges of Using Ammonia as a Future Fuel for Marine Industry: A Review. Sustain. Mar. Struct. 2024, 6, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping. Investigating Maritime Community Perceptions of Ammonia as a Marine Fuel; Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulou, C.; Di Maria, C.; Di Ilio, G.; Cigolotti, V.; Minutillo, M.; Rossi, M.; Sullivan, B.P.; Bionda, A.; Rautanen, M.; Ponzini, R.; et al. On the identification of regulatory gaps for hydrogen as maritime fuel. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 75, 104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Chun, K.W. A Comprehensive Review on Material Compatibility and Safety Standards for Liquid Hydrogen Cargo and Fuel Containment Systems in Marine Applications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, A.; Carrera, C.P.; Pappalardo, C.M.; Guida, D.; Berardi, V.P. A Comprehensive Literature Review on Hydrogen Tanks: Storage, Safety, and Structural Integrity. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustolin, F.; Campari, A.; Taccani, R. An Extensive Review of Liquid Hydrogen in Transportation with Focus on the Maritime Sector. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Koo, K.Y.; Joung, T.-H. A study on the necessity of integrated evaluation of alternative marine fuels. J. Int. Marit. Saf. Environ. Aff. Shipp. 2020, 4, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popek, M. Alternative Fuels—Prospects for the Shipping Industry. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Od Sea Transp. 2024, 18, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissner, N.; Healy, S.; Cames, M.; Sutter, J. Methanol as a Marine Fuel; Naturschutzbund Deutschland: Stuttgart, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). MSC.1/Circ.1621 Interim Guidelines for the Safety of Ships Using Methyl/Ethyl Alcohol as Fuel; International Maritime Organization (IMO): London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). MSC.1/Circ.1647 Interim Guidelines for the Safety of Ships Using Fuel Cell Power Installations; International Maritime Organization (IMO): London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Resolution MSC.565(108) Revised Interim Recommendations for Carriage of Liquefied Hydrogen in Bulk; International Maritime Organization (IMO): London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). MSC.1/Circ.1687 Interim Guidelines for the Safety of Ships Using Ammonia as Fuel; International Maritime Organization (IMO): London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, M.H.; Godina, R. Unveiling seafarers’ awareness and knowledge on energy-efficient and low-carbon shipping: A decade of IMO regulation enforcement. Mar. Policy 2024, 161, 106037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, M.H.; Mustafi, M.A.A.; Matos, F.; Godina, R. Exploring seafarers’ knowledge, understanding, and proficiency in SEEMP: A strategic training framework for enhancing seafarers’ competence in energy-efficient ship operations. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gahtani, S.S.; King, M. Attitudes, satisfaction and usage: Factors contributing to each in the acceptance of information technology. Behav. Inf. Technol. 1999, 18, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, P.Y. An empirical assessment of a modified technology acceptance model. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 1996, 13, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.J.; Karsh, B.T. The Technology Acceptance Model: Its past and its future in health care. J. Biomed. Inform. 2010, 43, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.J.; Chau, P.Y.K.; Sheng, O.R.L.; Tam, K.Y. Examining the technology acceptance model using physician acceptance of telemedicine technology. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 1999, 16, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, H.-A. Development of a health information technology acceptance model using consumers’ health behavior intention. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A. Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Electron. Comm. 2003, 7, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutahar, A.M.; Daud, N.M.; Ramayah, T.; Isaac, O.; Aldholay, A.H. The effect of awareness and perceived risk on the technology acceptance model (TAM): Mobile banking in Yemen. Int. J. Serv. Stand. 2018, 12, 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboul-Dahab, K. Autonomous Maritime Operations Acceptance Based on Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roestad, V.O.S. The validity of an extended technology acceptance model (TAM) for Assessing the Acceptability of Autonomous Ships. Master’s Thesis, Høgskolen i Sørøst-Norge, Kongsberg, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Durana, C.J.; Balga, I.; Bernardo, J.L.F.; Cardano, L.; Maniapao, K.V.; Pracambo, K.N. The Impact of Digitalization in Enhancing Maritime Safety of Cruise Ships. Ocean. Life Int. J. Marit. Occup. Saf. 2025, 3, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misas, J.D.P.; Hopcraft, R.; Tam, K.; Jones, K. Future of maritime autonomy: Cybersecurity, trust and mariner’s situational awareness. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanjuntak, M.; Barasa, L.; Simanjuntak, M.B. Exploring maritime safety and risk management practices among STIP Jakarta graduates. JPPI J. Penelit. Pendidik. Indones. 2024, 10, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Fourth IMO GHG Study 2020; International Maritime Organization (IMO): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DNV. Decision on the IMO Net-Zero Framework Delayed for One Year. 17 October 2025. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/news/2025/decision-on-the-imo-net-zero-framework-delayed-for-one-year/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- European Commission. Reducing Emissions from the Shipping Sector. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/transport-decarbonisation/reducing-emissions-shipping-sector_en (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Conway, M. Alt-Fuel Adoption on the Ascent, DNV Notes. Available online: https://rina.org.uk/publications/the-naval-architect/alt-fuel-adoption-on-the-ascent/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Wang, K.; Wang, J.; Huang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, G.; Xing, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, X. A comprehensive review on the prediction of ship energy consumption and pollution gas emissions. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 266, 112826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, C.; Zhu, B.; Qiao, J. Energy saving method for ship weather routing optimization. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 258, 111771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, K.; Hua, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, R.; Wang, Z.; Huang, L. GA-LSTM and NSGA-III based collaborative optimization of ship energy efficiency for low-carbon shipping. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 312, 119190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianyun, Z.; Li, C.; Lijuan, X.; Bin, W. Bi-objective optimal design of plug-in hybrid electric propulsion system for ships. Energy 2019, 177, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacar, Z.; Sasaki, N.; Atlar, M.; Korkut, E. An investigation into effects of Gate Rudder® system on ship performance as a novel energy-saving and manoeuvring device. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 218, 108250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liang, H.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Jing, Z.; Chi, Y.; Ma, R.; Cao, J.; Huang, L. Investigations and applications of carbon control technology: The roadmap to zero-carbon shipping. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 339, 121898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Stuart, C.; Spence, S.; Chen, H. Alternative fuel options for low carbon maritime transportation: Pathways to 2050. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 297, 126651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, K.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, R.; Cao, J.; Huang, L. Marine alternative fuels for shipping decarbonization: Technologies, applications and challenges. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 329, 119641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Maritime Just Transition Task Force Secretariat; Platten, G.; Selwyn, M.; Vicente, H.; Cotton, S. Ensuring seafarers are at the heart of decarbonization action. In Maritime Decarbonization: Practical Tools, Case Studies and Decarbonization Enablers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Noufal, A.S.; Torky, A.; Tonbol, K. Assessment of awareness regarding climate change between seafarers towards SDGs achievement. Blue Econ. 2023, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, M.H.; Godina, R. Sailing towards sustainability: How seafarers embrace new work cultures for energy efficient ship operations in maritime industry. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 232, 1930–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yu, C.S.; Liu, C.; Yao, J.E. Technology acceptance model for wireless Internet. Internet Res. 2003, 13, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.Y.; Hwang, Y.J. Predicting the use of web-based information systems: Self-efficacy, enjoyment, learning goal orientation, and the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Hum. Comput. St. 2003, 59, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.-C.; Lu, M.-T. Understanding internet banking adoption and use behavior: A Hong Kong perspective. J. Glob. Inform. Manag. (JGIM) 2004, 12, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkarainen, T.; Pikkarainen, K.; Karjaluoto, H.; Pahnila, S. Consumer acceptance of online banking: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfoser, S.; Schauer, O.; Costa, Y. Acceptance of LNG as an alternative fuel: Determinants and policy implications. Energ Policy 2018, 120, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-f.; Xu, X.; Arpan, L. Between the technology acceptance model and sustainable energy technology acceptance model: Investigating smart meter acceptance in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 25, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaaffar, A.H.; Majid, N.A.; Alrazi, B.; Ramachandaramurty, V.K.; Dahlan, N.Y. Determinants of Residential Consumers’ Acceptance of a Utility-Scale Battery Energy Storage System in Malaysia: Technology Acceptance Model Theory from a Different Perspective. Energies 2022, 15, 5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamidimukkula, A.; Kermanshachi, S.; Rosenberger, J.M.; Hladik, G. An empirical examination of factors affecting adoption of alternative fuel vehicles. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 90, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Danwana, S.B.; Yassaanah, I.F.L. An Empirical Study of Renewable Energy Technology Acceptance in Ghana Using an Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Lee, B. Exploring factors influencing electric vehicle purchase intentions through an Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Vehicles 2024, 6, 1513–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, R.C.; Lin, Y.H. Exploring the Consumer Attitude of Building-Attached Photovoltaic Equipment Using Revised Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, P.; Hülemeier, A.G.; Jendryczko, D.; Baumann, M.J.; Weil, M.; Baur, D. Public acceptance of emerging energy technologies in context of the German energy transition. Energ. Policy 2020, 142, 111516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianole-Călin, R.; Druică, E. A risk integrated technology acceptance perspective on the intention to use smart grid technologies in residential electricity consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 133436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xiao, Y.; Pacala, A.; Badulescu, A.; Khan, S. Understanding Chinese Farmers’ Behavioral Intentions to Use Alternative Fuel Machinery: Insights from the Technology Acceptance Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tong, H.Y.; Liang, Y.Q.; Qin, Q.D. Consumer purchase intention of new energy vehicles with an extended technology acceptance model: The role of attitudinal ambivalence. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 174, 103742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Zhao, S.S.; Zhao, S.X. Adoption of digital logistics platforms in the maritime logistics industry: Based on diffusion of innovations and extended technology acceptance. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.S. Maritime shipping digitalization: Blockchain-based technology applications, future improvements, and intention to use. Transp. Res. Part E 2019, 131, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, D.W. The importance of ease of use, usefulness, and trust to online consumers: An examination of the technology acceptance model with older customers. J. Organ. End User Comput. (JOEUC) 2006, 18, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.W.; Zhao, Y.X.; Zhu, Q.H.; Tan, X.J.; Zheng, H. A meta-analysis of the impact of trust on technology acceptance model: Investigation of moderating influence of subject and context type. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2011, 31, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijts, N.M.A.; Molin, E.J.E.; Steg, L. Psychological factors influencing sustainable energy technology acceptance: A review-based comprehensive framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.C.; Wang, C.; Zhu, S.; Xue, H.L.; Chen, F.Y. Online Purchase Intention of Fruits: Antecedents in an Integrated Model Based on Technology Acceptance Model and Perceived Risk Theory. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanobetti, F.; Pio, G.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Ortiz, M.M.; Cozzani, V. Inherent safety of clean fuels for maritime transport. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 174, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S. Perceived risk, usage frequency of mobile banking services. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2013, 23, 410–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangunić, N.; Granić, A. Technology acceptance model: A literature review from 1986 to 2013. Univers. Access Inform. Soc. 2015, 14, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Understanding Attitudes and Predictiing Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Grazioli, S.; Jaryenpaa, S.L. Perils of Internet fraud: An empirical investigation of deception and trust with experienced Internet consumers. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Hum. 2000, 30, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Tractinsky, N.; Vitale, M. Consumer trust in an Internet store. Inform. Technol. Manag. 2000, 1, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramjan, S.; Sangkaew, P. Understanding the adoption of autonomous vehicles in Thailand: An extended TAM approach. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2022, 14, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J.W. What is rotating in exploratory factor analysis? Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2015, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1958, 23, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, H.M.; Mustapha, R.; Mohamad, S.A.M.S.; Bunian, M.S. Measurement model of employability skills using confirmatory factor analysis. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 56, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]