Influence of a Sloped Bottom on a 60-Degree Inclined Dense Jet Discharged into a Stationary Environment: A Large Eddy Simulation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Large Eddy Simulation

2.2. RANS Model

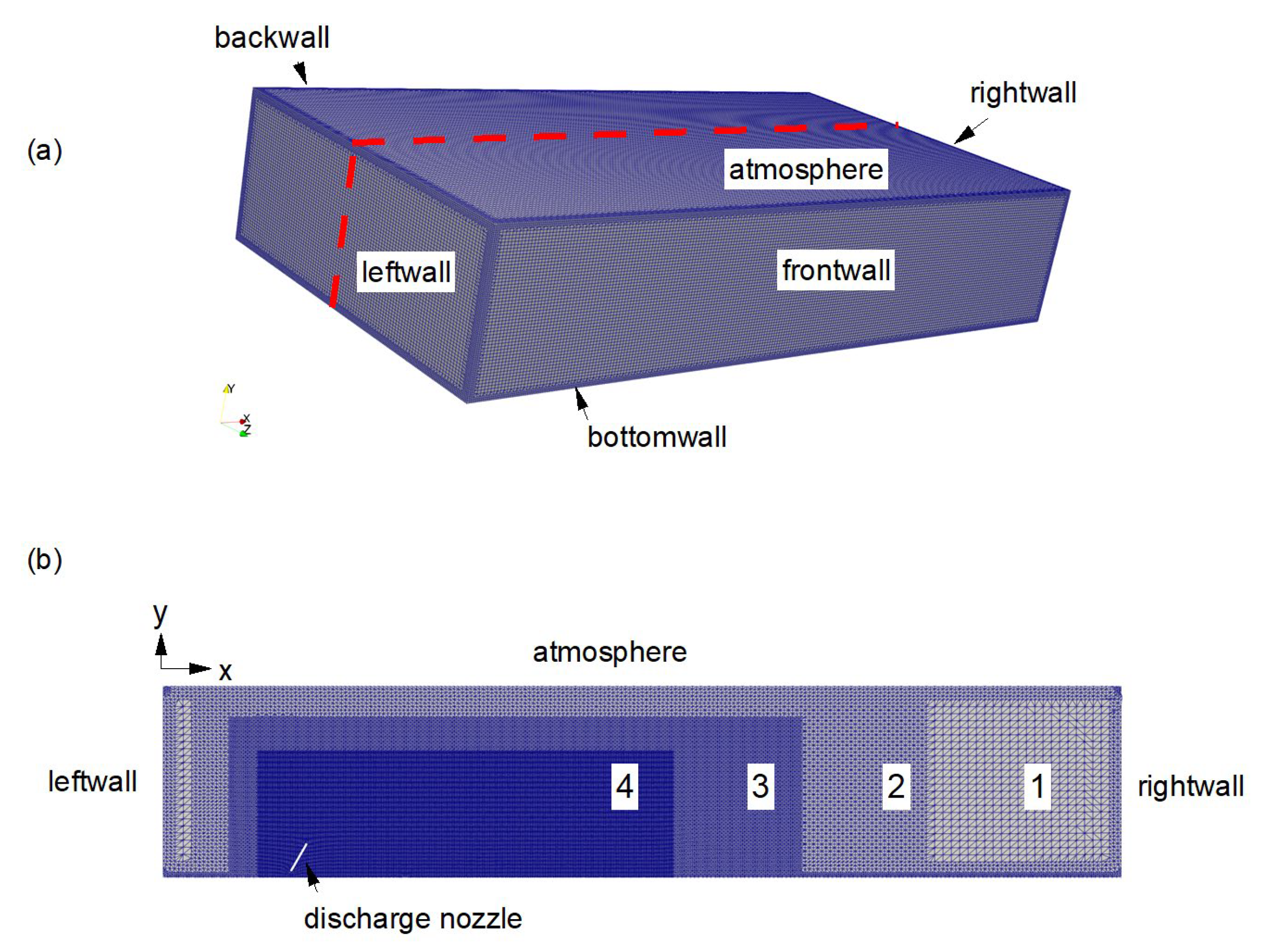

2.3. Computational Domain and Boundary Conditions

2.4. Mesh Generation and Grid Analysis

2.4.1. RANS Mesh

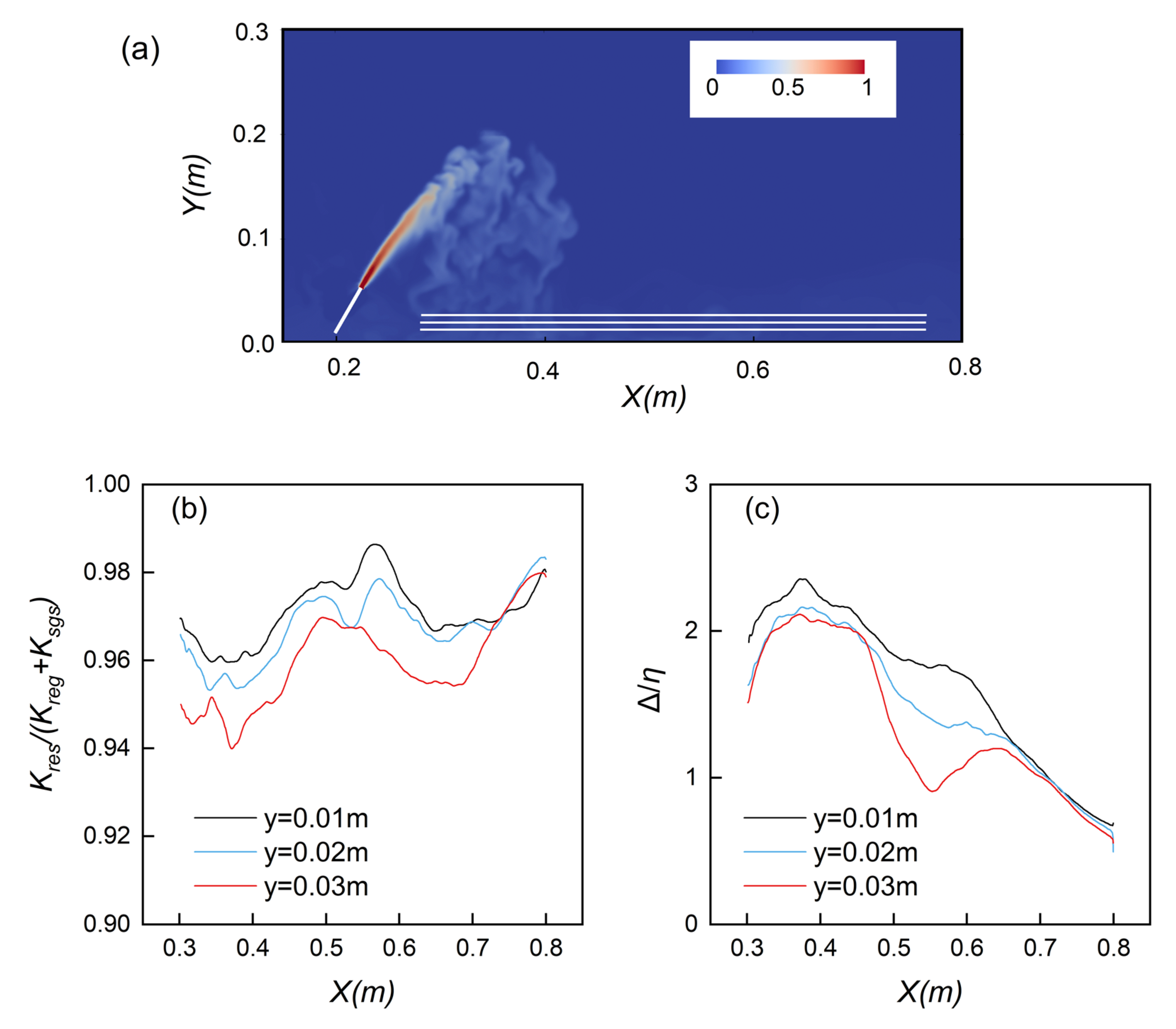

2.4.2. LES Mesh

3. Results and Discussion

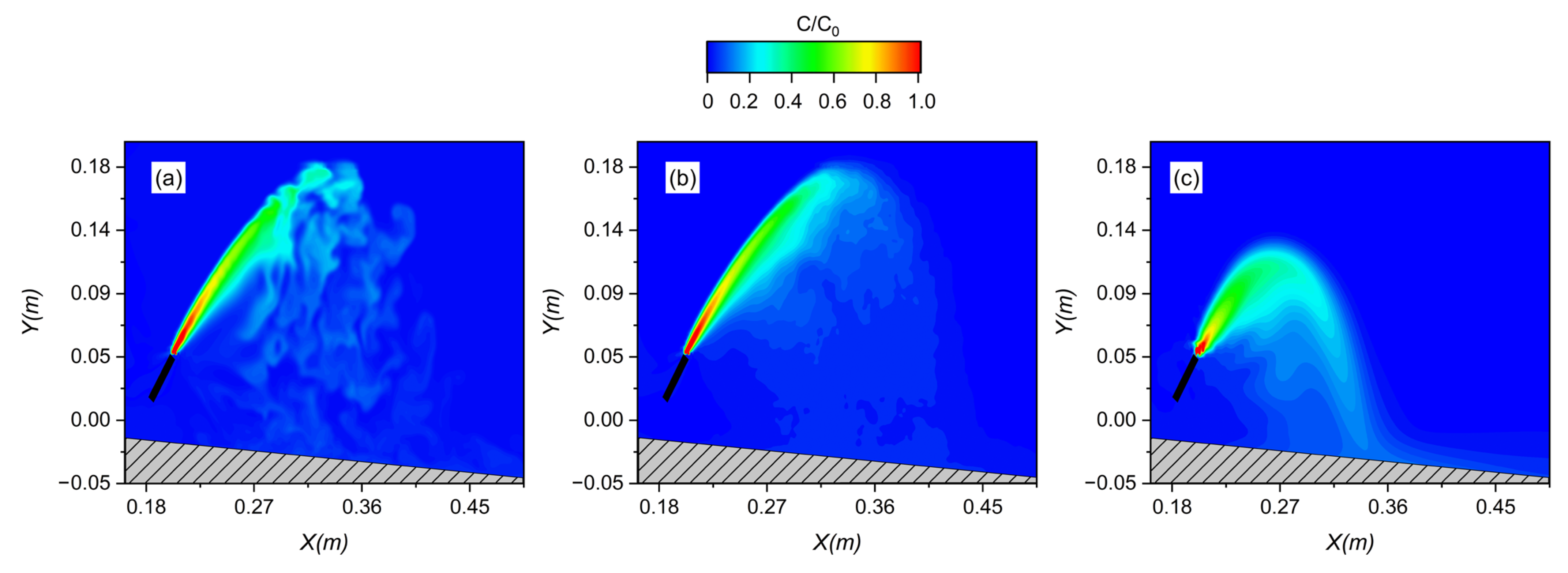

3.1. The Instantaneous and Time-Averaged Results

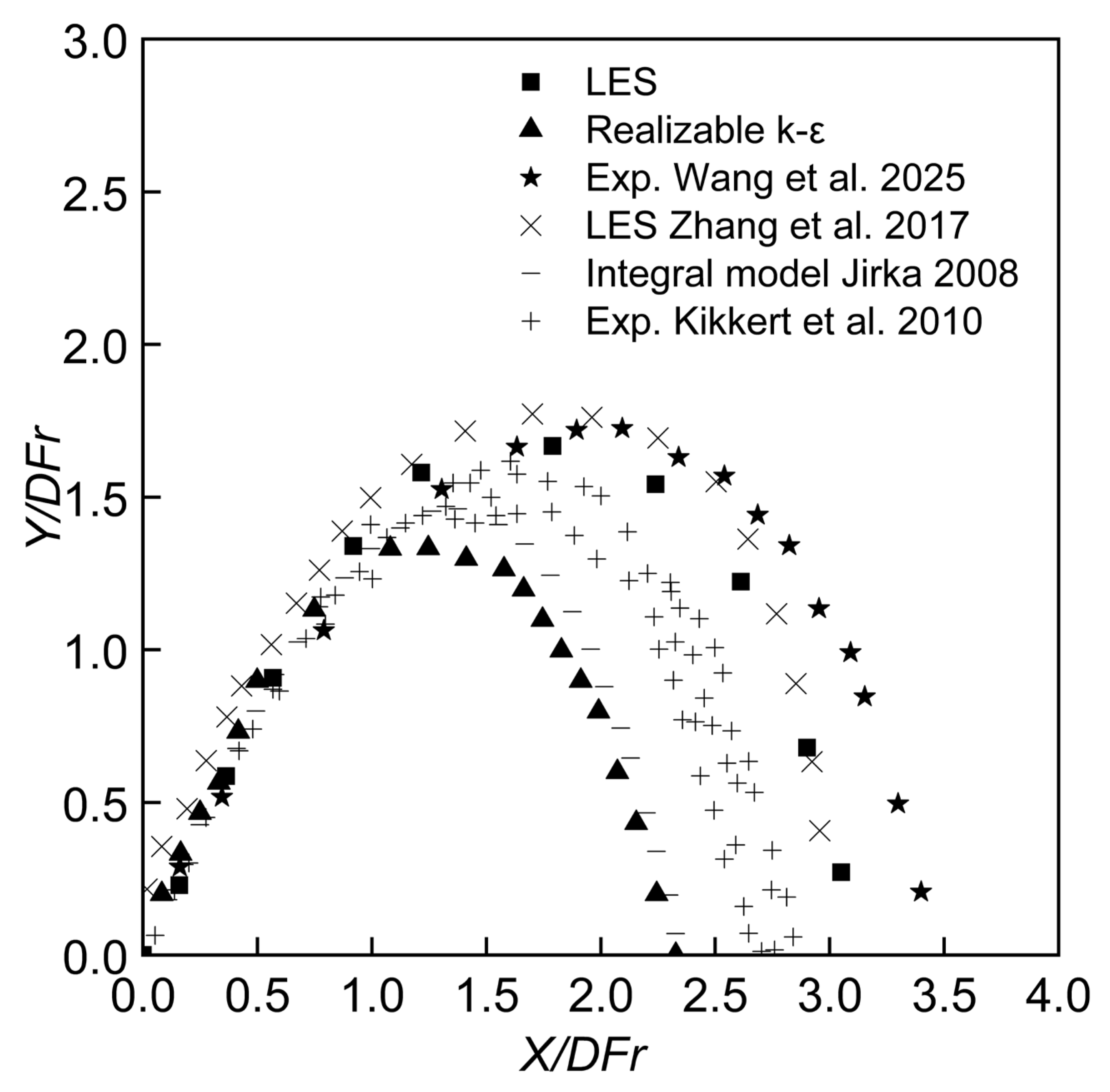

3.2. Jet Trajectory

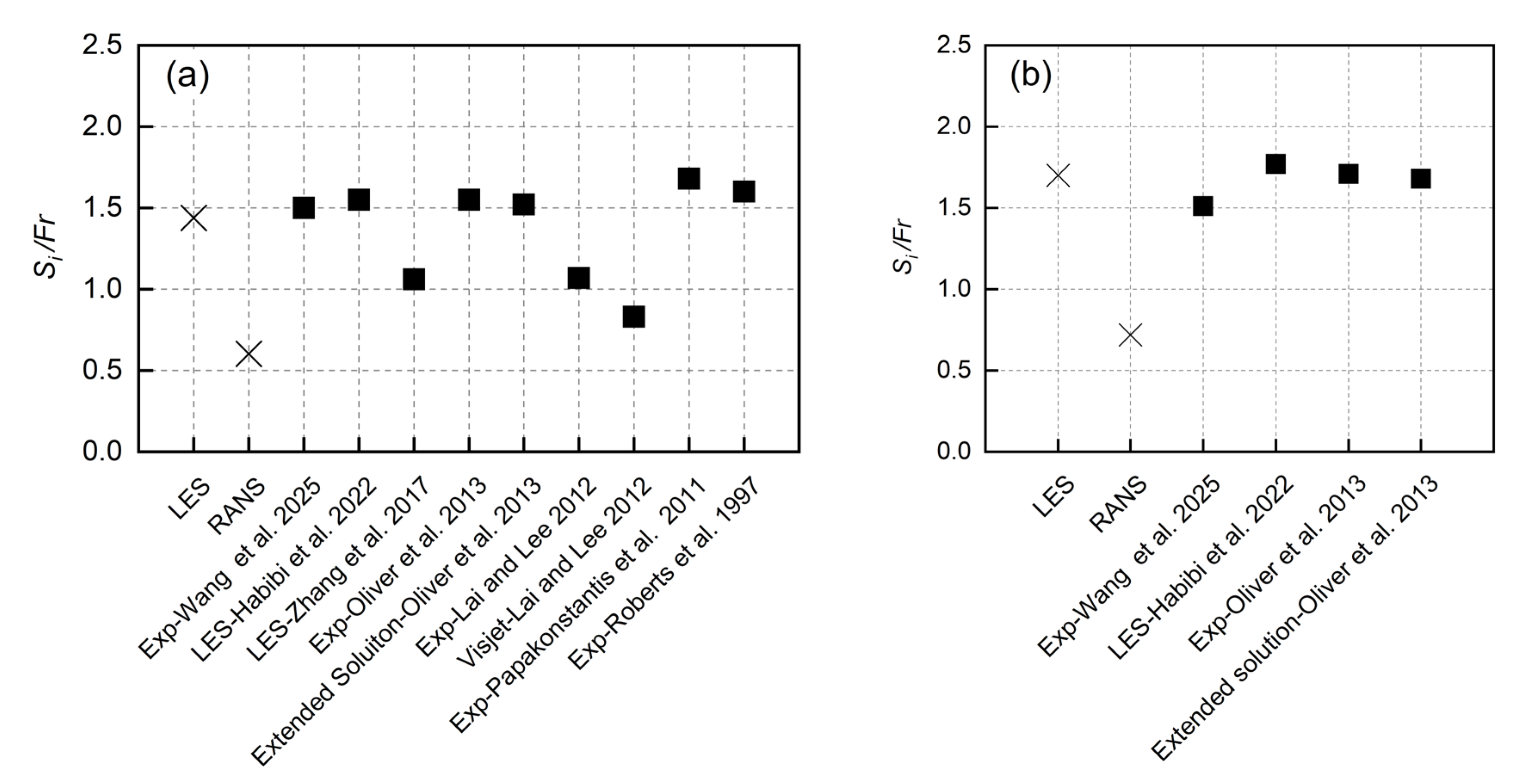

3.3. Overview of Geometrical Information

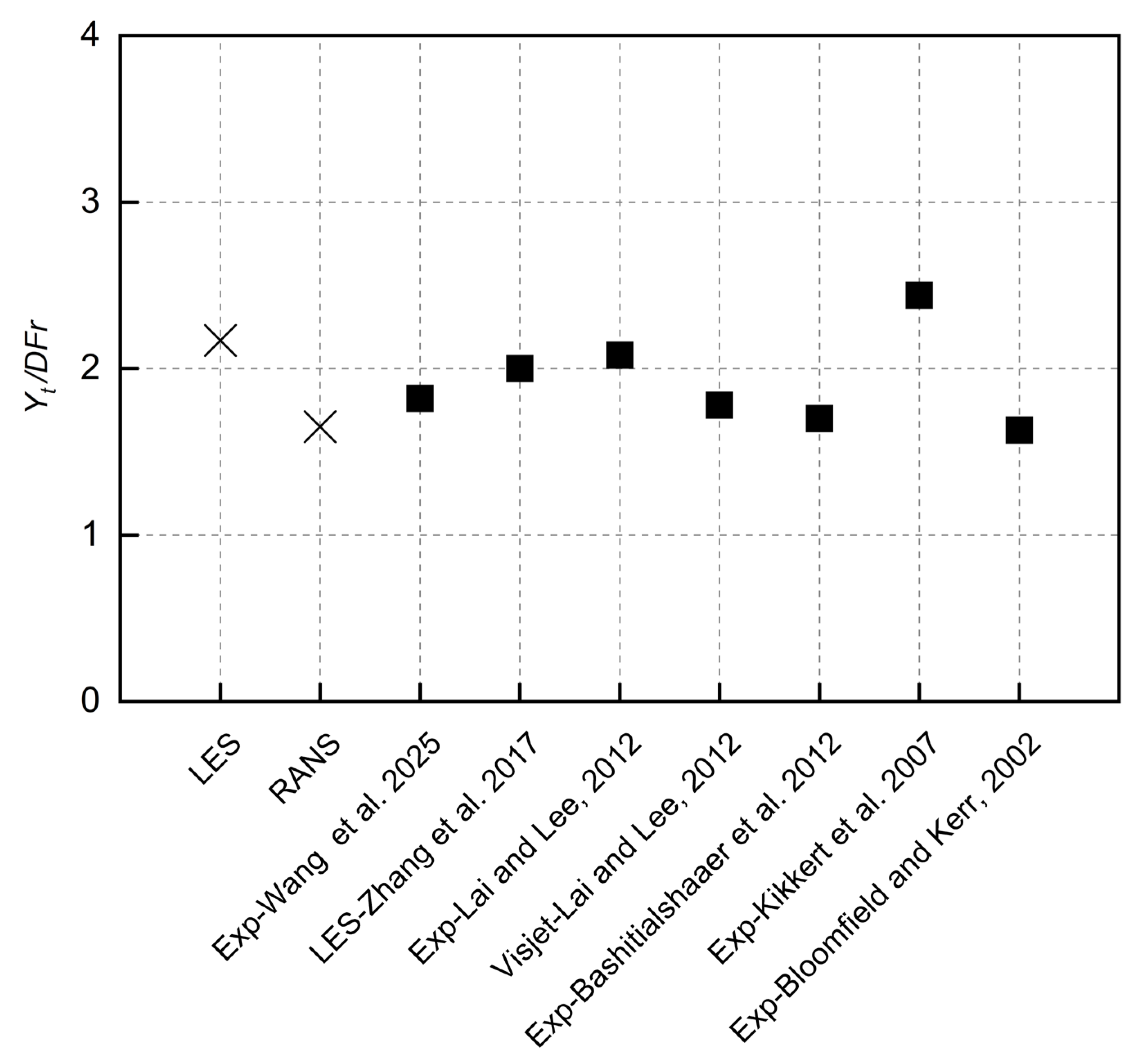

3.4. Terminal Rise Height and Centerline Peak

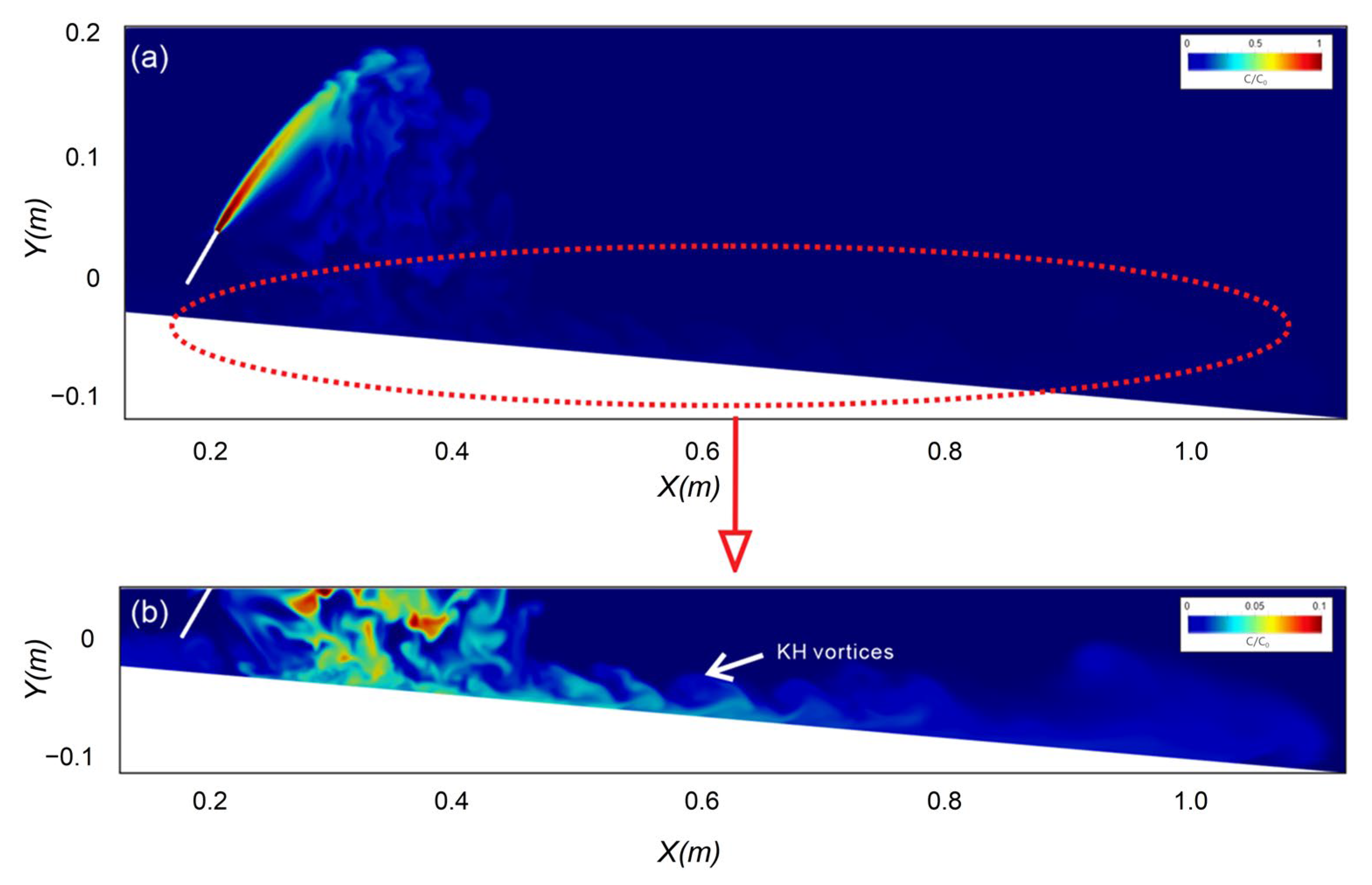

3.5. The Effect of the Sloped Bottom at Impact Point

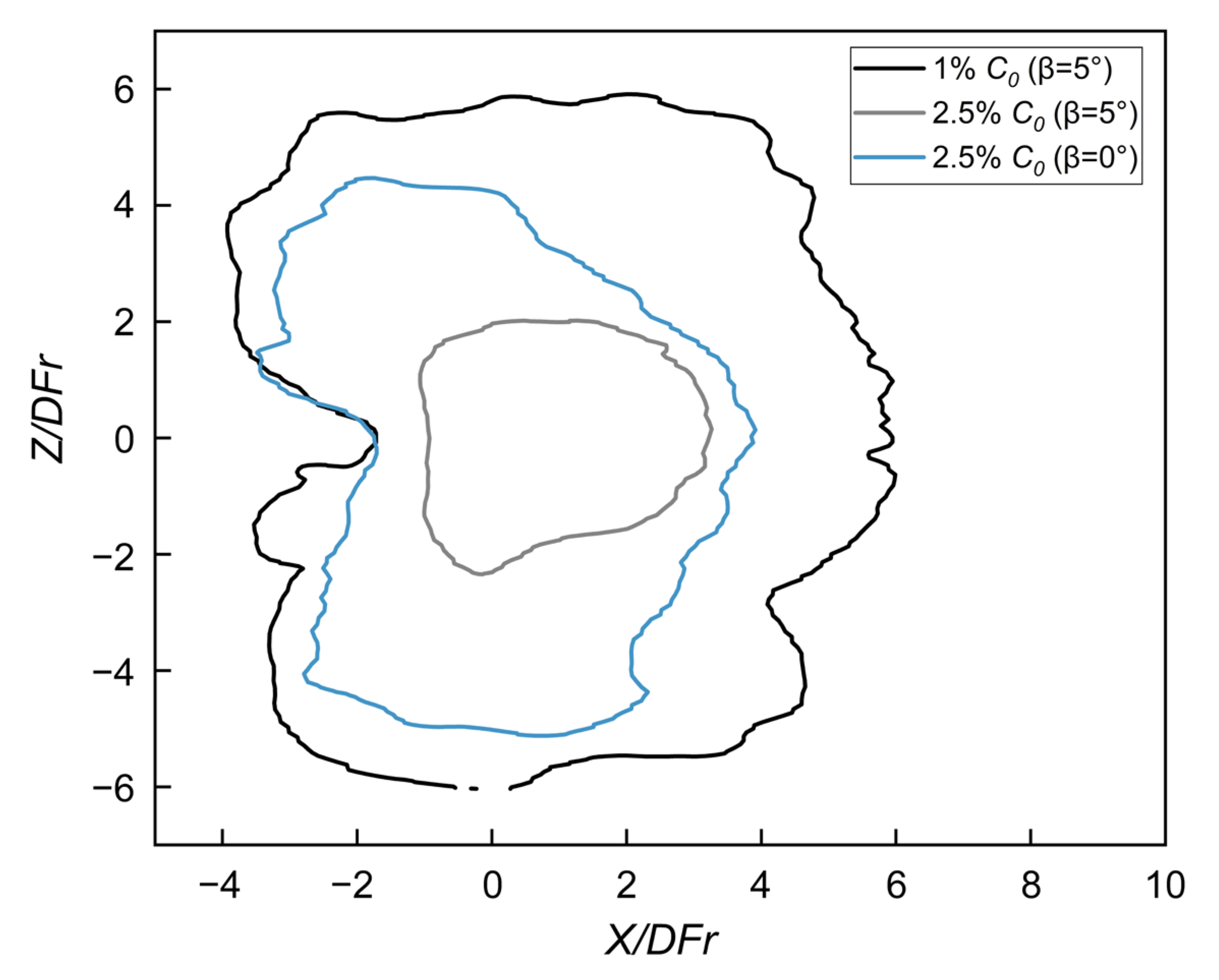

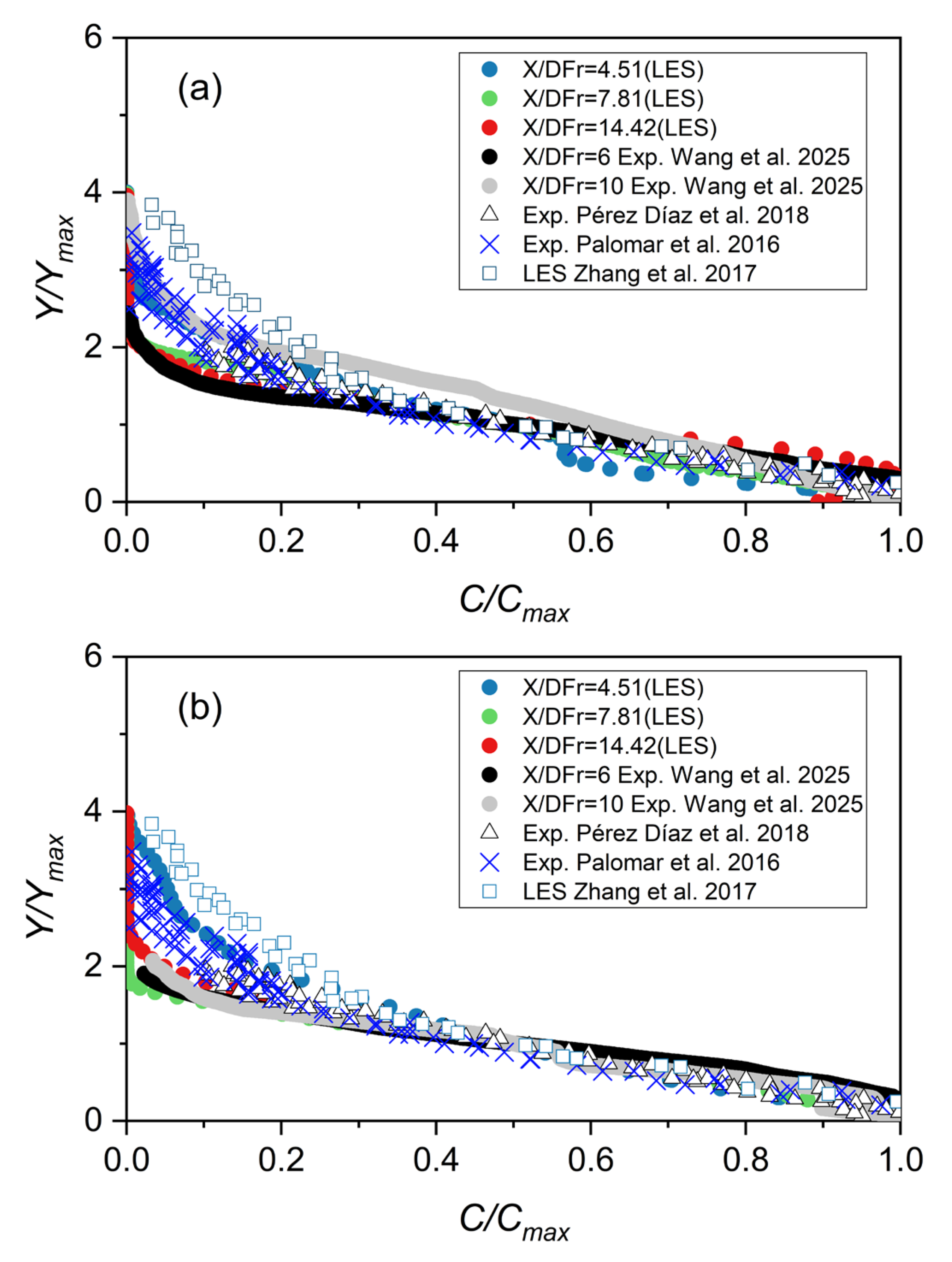

3.6. Concentration Distribution near the Impact Point

3.7. Spreading Layer Characteristics—Dilution Along the Bottom

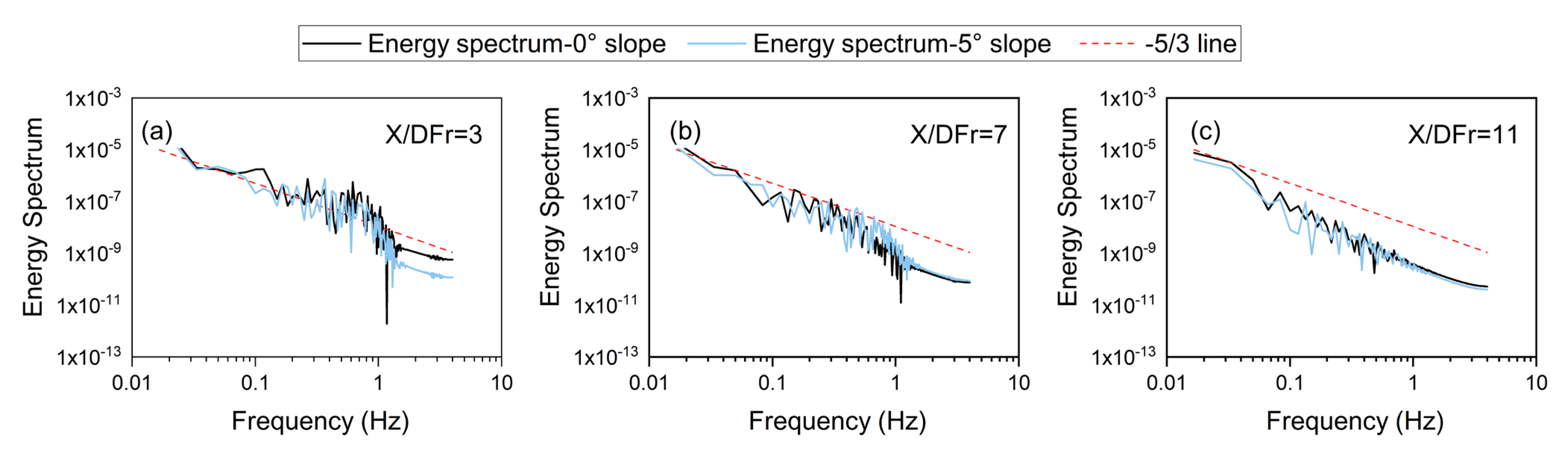

3.8. Energy Spectrum Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| LES | Large Eddy Simulation |

| RNG | Renormalisation Group |

| SGS | Subgrid Scale |

| RANS | Reynold Averaged Navier Stokes Equation |

| TKE | Turbulent Kinetic Energy |

| LIF | Laser-Induced Fluorescence |

| LA | Light Attenuation |

| KH | Kelvin–Helmholtz |

| Fr | Froude Number |

| D | Diameter |

| X,Y | Coordinates |

| Velocity Components in x, y, z directions | |

| Filtered/Averaged Velocity Components | |

| Filtered/Averaged pressure | |

| Fluid density | |

| Time | |

| Spatial Coordinate Components | |

| Molecular Dynamic Viscosity | |

| Molecular Kinematic Viscosity | |

| Subgrid-scale (SGS) stress | |

| Subgrid-scale (SGS) eddy viscosity | |

| Subgrid-scale (SGS) turbulent kinetic energy | |

| Subgrid-scale (SGS) dissipation rate | |

| Corrected Strain Rate Tensor | |

| Filter Width | |

| Subgrid-scale (SGS) Viscosity Model Constant | |

| Subgrid-scale (SGS) Dissipation Constant | |

| Ksgs Transport Constant | |

| Reynolds Stress Tensor | |

| Turbulent Eddy Viscosity | |

| Turbulent Kinetic Energy | |

| Dissipation Rate | |

| RANS Model Constants | |

| transport equation Constant | |

| Averaged Strain Rate Tensor | |

| Ratio of Strain to Dissipation | |

| Modulus of Averaged Strain Rate Tensor | |

| Rotation Rate Tensor | |

| Calculation | |

| κ | Wavenumber |

| E(κ) | Energy spectrum |

References

- Sedlak, D. Water for All: Global Solutions for a Changing Climate; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-0-300-25693-2. [Google Scholar]

- Meerganz von Medeazza, G.L. “Direct” and Socially-Induced Environmental Impacts of Desalination. Desalination 2005, 185, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, K.; Kamil, M.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Wilberforce, T.; Olabi, A. Environmental Impact of Desalination Technologies: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeitoun, M.A.; McIlhenny, W.F. Conceptual Designs of Outfall Systems for Desalination Plants. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 18–20 April 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.J.; Ferrier, A.; Daviero, G. Mixing in Inclined Dense Jets. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1997, 123, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Querzoli, G. Mixing and Re-Entrainment in a Negatively Buoyant Jet. J. Hydraul. Res. 2010, 48, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, L.J.; Kerr, R.C. Inclined Turbulent Fountains. J. Fluid Mech. 2002, 451, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipollina, A.; Brucato, A.; Grisafi, F.; Nicosia, S. Bench-Scale Investigation of Inclined Dense Jets. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2005, 131, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashitialshaaer, R.; Larson, M.; Persson, K.M. An Experimental Investigation on Inclined Negatively Buoyant Jets. Water 2012, 4, 720–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantis, I.G.; Christodoulou, G.C.; Papanicolaou, P.N. Inclined Negatively Buoyant Jets 1: Geometrical Characteristics. J. Hydraul. Res. 2011, 49, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantis, I.G. Inclined Negatively Buoyant Jets 2: Concentration Measurements. J. Hydraul. Res. 2011, 49, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wei, Y.; Law, A.W.-K.; Huai, W. Mixing and Spreading of Inclined Dense Jets with Submerged Aquatic Canopies. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2024, 24, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikkert, G.A.; Davidson, M.J.; Nokes, R.I. Inclined Negatively Buoyant Discharges. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2007, 133, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Law, A.W.-K. Mixing and Boundary Interactions of 30 and 45 Inclined Dense Jets. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2010, 10, 521–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.C.; Lee, J.H. Mixing of Inclined Dense Jets in Stationary Ambient. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2012, 6, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, M.; Goharikamel, D.; Vafaei, F. Experimental Investigation of Nozzle Angle Effects on the Brine Discharge by Inclined Dense Jets in Stagnant Water Ambient. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantis, I.G.; Mylonakou, E.L. Flow Visualization Experiments of Inclined Slot Jets with Negative Buoyancy. Environ. Process. 2021, 8, 1549–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Badas, M.G.; Besalduch, L.A.; Querzoli, G. Experimental Investigation of Inclined Negatively Buoyant Jet. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Turbulence and Shear Flow Phenomena, Poitiers, France, 28–30 August 2013; Begel House Inc.: Danbury, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Law, A.W.-K.; Lai, A.C.H. Turbulence Characteristics of 45° Inclined Dense Jets. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2019, 19, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, A.; Gildeh, H.K.; Nistor, I. CFD Modeling of Effluent Discharges: A Review of Past Numerical Studies. Water 2020, 12, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.D.; Wendt, J. Computational Fluid Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; Volume 206. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadian, A.; Gildeh, H.K.; Yan, X. Numerical Simulation of Effluent Discharges: Applications with OpenFOAM; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-003-18181-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vafeiadou, P.; Papakonstantis, I.; Christodoulou, G. Numerical Simulation of Inclined Negatively Buoyant Jets. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, Rhodes, Greece, 1–3 September 2005; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C.J.; Davidson, M.J.; Nokes, R.I. K-ε Predictions of the Initial Mixing of Desalination Discharges. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2008, 8, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirkhah Gildeh, H.; Mohammadian, A.; Nistor, I.; Qiblawey, H. Numerical Modeling of 30° and 45° Inclined Dense Turbulent Jets in Stationary Ambient. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2015, 15, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mohammadian, A. A Comparison of k–ε Type Turbulence Models for Prediction of Inclined Dense Jets. In Computational Fluid Dynamics: Novel Numerical and Computational Approaches: Methodology and Numerics; Zeidan, D., Hidalgo, A., Zhang, L.T., Goncalves Da Silva, E., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 185–217. ISBN 978-981-97-8152-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Jiang, B.; Law, A.W.-K.; Zhao, B. Large Eddy Simulations of 45 Inclined Dense Jets. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2016, 16, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Law, A.W.-K.; Jiang, M. Large Eddy Simulations of 45° and 60° Inclined Dense Jets with Bottom Impact. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2017, 15, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantis, I.G.; Christodoulou, G.C. Spreading of Round Dense Jets Impinging on a Horizontal Bottom. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2010, 4, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.J.; Davidson, M.J.; Nokes, R.I. Behavior of Dense Discharges beyond the Return Point. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2013, 139, 1304–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirka, G.H. Integral Model for Turbulent Buoyant Jets in Unbounded Stratified Flows. Part I: Single Round Jet. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2004, 4, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforakis, I.K.; Christodoulou, G.C.; Stamou, A.I. Bottom Concentration Field Due to Impingement of Inclined Dense Jets on a Slope. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium of Environmental Hydraulics, Singapore, 7–8 January 2014; pp. 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Mohammadian, A. Numerical Simulations of 15-Degree Inclined Dense Jets in Stagnate Water Over a Sloped Bottom. In Proceedings of the Canadian Society of Civil Engineering Annual Conference 2021, Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 26–29 May 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Azadi, A.; Firoozabadi, B. Large Eddy Simulation of Inclined Negatively Buoyant Jets with Sloped Beds. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2022, 148, 04022023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Azadi, A.; Firoozabadi, B. Identification of Turbulent Structures of Inclined Negatively Buoyant Jets with Bed Effects. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 208, 124040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mohammadian, A.; Ferrari, S.; Roberts, P. Experimental Investigation of the Influence of a Sloped Bottom on the Behavior of Inclined Dense Jets. Environ. Process. 2025. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P.J. Large-eddy Simulation: A Critical Review of the Technique. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1994, 120, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagorinsky, J. General circulation experiments with the primitive equations. Mon. Weather Rev. 1963, 91, 99–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Addona, F.; Chiapponi, L.; Merli, N.; Archetti, R. Numerical Simulation of Turbulent Fountains with Negative Buoyancy. Modelling 2025, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, F.G. About Boussinesq’s Turbulent Viscosity Hypothesis: Historical Remarks and a Direct Evaluation of Its Validity. Comptes Rendus Mécanique 2007, 335, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaifi, H.; Mohammadian, A.; Bonakdari, H. Predicting the Geometrical Characteristics of an Inclined Negatively-Buoyant Jet for Angles from 30° to 60° Using GMDH Neural Network. In Proceedings of the Canadian Society of Civil Engineering Annual Conference 2021: CSCE21 Hydrotechnical and Transportation Track, Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 26–29 May 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenshields, C.J. OpenFOAM User Guide, Version 3; OpenFOAM Foundation Ltd.: London, UK, 2015.

- Kheirkhah Gildeh, H.; Mohammadian, A.; Nistor, I. Inclined Dense Effluent Discharge Modelling in Shallow Waters. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2021, 21, 955–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi Hosseini, S.A.R.; Mohammadian, A.; Roberts, P.J.; Abessi, O. Numerical Study on the Effect of Port Orientation on Multiple Inclined Dense Jets. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Abessi, O.; Firoozjaee, A.R. Effect of Proximity to Bed on 30° and 45° Inclined Dense Jets: A Numerical Study. Environ. Process. 2021, 8, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Giljarhus, K.E.T.; Skadsem, H.J.; Time, R.W. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation of Buoyant Mixing of Miscible Fluids in a Tilted Tube; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1201, p. 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.F.; Johnson, C.J.; Tang, C.Y.; Jensen, M.; Yde, L.; Hélix-Nielsen, C. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations of Flow and Concentration Polarization in Forward Osmosis Membrane Systems. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 379, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.P.; McWilliams, J.C.; Moeng, C.-H. A Subgrid-Scale Model for Large-Eddy Simulation of Planetary Boundary-Layer Flows. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1994, 71, 247–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.B. Ten Questions Concerning the Large-Eddy Simulation of Turbulent Flows. New J. Phys. 2004, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.B. Turbulent Flows; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-521-59886-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cintolesi, C.; Petronio, A.; Armenio, V. Turbulent Structures of Buoyant Jet in Cross-Flow Studied through Large-Eddy Simulation. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2019, 19, 401–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abessi, O.; Roberts, P.J. Effect of Nozzle Orientation on Dense Jets in Stagnant Environments. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2015, 141, 06015009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirka, G.H. Improved Discharge Configurations for Brine Effluents from Desalination Plants. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2008, 134, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikkert, G.A.; Davidson, M.J.; Nokes, R.I. Buoyant Jets with Three-Dimensional Trajectories. J. Hydraul. Res. 2010, 48, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Law, A.W.-K.; Lee, J.H.-W. Mixing of 30° and 45° Inclined Dense Jets in Shallow Coastal Waters. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2014, 140, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemlioglu, S.; Roberts, P. Experiments on Dense Jets Using Three-Dimensional Laser-Induced Fluorescence (3DLIF). In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Marine Waste Water Disposal and Marine Environment & 2nd International Exhibition on Materials Equipment and Services for Coastal WWTP, Outfalls and Sealines, Antalya, Turkey, 6–10 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Díaz, B.; Palomar, P.; Castanedo, S.; Álvarez, A. PIV-PLIF Characterization of Nonconfined Saline Density Currents under Different Flow Conditions. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2018, 144, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar, P.; Lara, J.L.; Losada, I.J. PIV-PLIF Experimental Study of the Spreading Layer Arisen from Brine Jet Discharges. Exp. Fluids 2016. under revision. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, U.; Kolmogorov, A.N. Turbulence: The Legacy of A. N. Kolmogorov; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; ISBN 978-0-521-45713-2. [Google Scholar]

| Mesh Quality | Cells Number | Max Skewness | Max Aspect Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse | 839,075 | 2.92 | 9.32 |

| Medium | 1,848,426 | 3.02 | 2.15 |

| Fine | 2,954,166 | 2.64 | 4.05 |

| Quantity | Terminal Rise Height | Horizontal Location of Centerline Peak | Vertical Location of Centerline Peak | Horizontal Location of Impact Point | Dilution at Centerline Peak | Dilution at Impact Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yt/DFr | Xc/DFr | Yc/DFr | Xi/DFr | Sm/Fr | Si/Fr | |

| LES | 2.17 | 1.82 | 1.72 | 3.17 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Realizable | 1.65 | 1.24 | 1.33 | 2.46 | 0.22 | 0.60 |

| Exp [36] | 1.82 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 3.33 | 0.45 | 1.44 |

| LES [28] | 2.00 | 1.75 | 1.70 | 2.67 | 0.35 | 1.10 |

| Exp [15] | 2.08 | 1.78 | 1.64 | - | 0.44 | 1.07 |

| Exp [10,11] | 2.14 | 1.83 | 1.68 | 2.75 | 0.56 | 1.68 |

| Exp [13] | 2.44 | 1.8 | 1.74 | 2.81 | - | 1.82 |

| Quantity | Horizontal Location of Impact Point | Dilution at Impact Point |

|---|---|---|

| Xi/DFr | Si/Fr | |

| LES | 3.62 | 1.7 |

| Realizable | 2.51 | 0.72 |

| Exp [36] | 3.76 | 1.51 |

| CorJet [53] | ~2.4 | ~1.25 |

| Exp [30] | 2.79 | 1.71 |

| Extended solution [30] | 2.71 | 1.68 |

| LES [34] | - | 1.77 |

| Bottom Condition | Surface Fitting Function | |

|---|---|---|

| horizontal bottom | 0.90 | |

| sloped bottom | 0.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Mohammadian, A. Influence of a Sloped Bottom on a 60-Degree Inclined Dense Jet Discharged into a Stationary Environment: A Large Eddy Simulation Study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122309

Wang X, Mohammadian A. Influence of a Sloped Bottom on a 60-Degree Inclined Dense Jet Discharged into a Stationary Environment: A Large Eddy Simulation Study. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122309

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xinyun, and Abdolmajid Mohammadian. 2025. "Influence of a Sloped Bottom on a 60-Degree Inclined Dense Jet Discharged into a Stationary Environment: A Large Eddy Simulation Study" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122309

APA StyleWang, X., & Mohammadian, A. (2025). Influence of a Sloped Bottom on a 60-Degree Inclined Dense Jet Discharged into a Stationary Environment: A Large Eddy Simulation Study. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122309