Abstract

Climate-induced ocean warming poses a major threat to marine invertebrate reproduction, including the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus, a species of considerable ecological, economic, and scientific interest. Its gonads, highly valued as a culinary delicacy, support local fisheries and aquaculture industries, making reproductive health a critical factor for both conservation and commercial viability. The present study reported the effects of elevated seawater temperatures, mimicking marine heatwave (MHW) conditions, on gonadal maturation and fertilization success on P. lividus. Here, adult specimens at the mature stage of gametogenesis were exposed to control (18 °C) and elevated temperature regimes (24 °C) over a six-week period, and key reproductive metrics were assessed, including histological analysis. Morphological analysis showed very evident gonadal retraction, nearly devoid of germ cells, both for males and females, with a significant decrease in the gonadal index. In addition, histological analysis revealed consistent damage to the gonads, with a significantly increase in histopathological index in specimens kept at 24 °C. These findings reinforce the temperature sensitivity of P. lividus reproduction, suggesting that recurrent heatwaves could severely impair its reproductive output and population dynamics with potential cascading effects on benthic community structure in a long-term ocean warming predicted to intensify.

1. Introduction

Anthropogenic climate change is profoundly altering marine environments, not only through gradual ocean warming but increasingly through the occurrence of marine heatwaves (MHWs), discrete, prolonged periods (from days to months) of anomalous high sea surface temperatures that deviate significantly from historical baselines [1,2]. Some of the recently observed marine heatwaves revealed the high vulnerability of marine ecosystems [3] and fisheries [4,5] to such extreme climate events. These extreme thermal events are becoming more frequent, intense, and persistent across global oceanic regions, including the Mediterranean Sea, which has been identified as a climate change hotspot [2,6,7]. MHWs can induce acute physiological stress in marine organisms, particularly ectothermic invertebrates whose biological processes are tightly coupled to ambient temperature regimes [8]. Despite increasing recognition of their ecological consequences, the sublethal effects of MHWs on the reproductive biology of marine benthic invertebrates remain insufficiently characterized.

Echinoderms, and sea urchins in particular, have been extensively utilized as model organisms in reproductive and developmental biology due to their external fertilization, synchronous spawning, and well-characterized gametogenic cycles [9], as well as in assessing the biological impacts of marine pollution, including emerging contaminants such as microplastics. Paracentrotus lividus, a keystone grazer and ecologically significant sea urchin species in the Mediterranean and eastern Atlantic coasts, exhibits a distinct seasonal reproductive pattern, with gametogenesis initiated in early autumn and spawning typically occurring in late winter to spring [10,11,12,13]. This species also holds considerable economic value [14] in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean regions, where its gonads constitute a high-value seafood product that supports both small-scale artisanal fisheries and emerging aquaculture initiatives [14]. Demand for premium-quality roe in domestic and export markets, particularly in France, Spain, Portugal, and North African countries, has kept harvesting pressure high and has driven the development of fishery regulations centered on size limits, seasonal closures, and restricted extraction methods [15]. Market values for P. lividus roe are among the highest for European echinoids, often comparable to international prices for Strongylocentrotus species, making the fishery economically important for coastal communities [11]. Despite this, global production remains dominated by wild harvests, as large-scale aquaculture has been constrained by biological bottlenecks such as slow growth, feed optimization, and larval rearing limitations [16]. In several regions, sustained exploitation has contributed to local population declines and reduced reproductive output, underscoring concerns regarding long-term stock viability [17]. Consequently, the species high economic value together with its ecological sensitivity, highlights the urgent need for integrated management, including stock assessments, habitat conservation, and the expansion of sustainable aquaculture, to ensure the continued viability of P. lividus fisheries across its range [18].

Reproductive success in P. lividus is highly dependent on environmental cues such as temperature and photoperiod, which regulate the timing of gonadal maturation and spawning. Previous studies have demonstrated that deviations from optimal temperature regimes can alter gametogenic progression, gamete quality, and fertilization dynamics [19]. However, most available data pertain to chronic exposure scenarios, with limited focus on short-term but intense thermal anomalies characteristic of marine heatwaves. Given the narrow thermal tolerance window reported for P. lividus, it is imperative to assess how acute thermal stress may interfere with critical reproductive processes, including gametogenesis, gamete viability, and fertilization success [20,21].

In this context, the present study aims to elucidate the effects of simulated marine heatwaves on the reproductive physiology of P. lividus. In more detail, we experimentally simulated heatwave conditions to investigate their impact on the reproductive physiology of P. lividus. We examined changes in gonadal development, gamete quality and fertilization success, as well as possible damage to the gonads, following exposure at the temperature of 24 °C. By integrating physiological, histological and developmental endpoints, this study provided novel insights into the vulnerability of P. lividus reproductive processes to acute thermal stress. Our findings have broader implications in understanding the reproductive resilience of benthic marine invertebrates under climate change scenarios and providing guidance for the sustainable management of sea urchin populations and fisheries in regions increasingly affected by marine heatwaves.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Adult Sea Urchin Collection and Maintenance

Adult sea urchins were collected in the Gulf of Naples at the island of Procida (Italy; Figure 1) in February 2025 at a 10 m depth, at a not privately owned or protected site, according to the Italian laws (DPR 1639/68, 19 September 1980, confirmed on 10 January 2000).

Figure 1.

A map of the study area (highlighted by white square) and coordinates was constructed by Google Earth (https://www.google.it/intl/it/earth/index.html, accessed 12 November 2025).

The collected specimens at the mature stage of gametogenesis were immediately transported in a thermally insulated box to the laboratory and maintained in tanks with circulating sea water at temperature of 18 °C for ten days until testing. A 10-day acclimation period at 18 °C is generally considered sufficient for P. lividus to recover from short-term collection and transport stress. Previous studies showed that this species stabilized its metabolic activity, feeding behavior, and righting response within several days following handling, provided that temperature and water quality remained within the species’ optimal physiological range (typically 15–20 °C). P. lividus exhibits rapid recovery of locomotion and adhesion strength after disturbance, with full restoration of behavioral and physiological baselines commonly occurring within 5–7 days under controlled laboratory conditions [12,16]. Consequently, a 10-day acclimation period not only exceeds the minimum recovery window reported in the literature but also ensures the stabilization of gonadal condition and feeding activity before the start of experimental trials. This duration is widely used in laboratory studies on European echinoids and is considered adequate to minimize artifacts associated with capturing stress and environmental transition.

2.2. Experimental Mesocosm

A mesocosm formed by four recirculating tanks independently closed was designed [22,23], each filled with 35 L of filtered seawater (200 μm Millipore filter). For the circulation of the seawater in the tanks, a pump (Micra 400 L/h, SICCE, Pozzoleone, Vicenza, Italy) was used, and the water passed through a filtration compartment containing porous ceramic rings and a mechanical filtration by a synthetic sponge.

Six females and five males were weighed and then added to each tank and daily fed on the fresh green alga Ulva rigida, a natural diet in marine environment usually populated by P. lividus [24]. As reported in Ruocco et al. [24] the daily feeding rate (as dry weight) for adult P. lividus corresponded to 0.16 g for U. rigida. They were reared in each of four experimental tanks (two tanks with controlled temperature sea water at 24 °C and two tanks at 18 °C, as control) under a 12 h:12 h light:dark photoperiod, for six weeks. Adult mortality was recorded during the whole experiment. Salinity, pH, O2, and temperature (multiparametric probe Hanna HI98494, Hanna Instruments, Padova, Italy), as well as NH3, NO2, NO3, and PO4 (spectrophotometer Hach Lange DR390, Hach Lange S.r.l, Lainate, Milano, Italy)) were measured once a week for the entire duration of the experiment (see Table S1). After six weeks, the sea urchins were collected and injected with 2 mL of 2 M KCl across the peribuccal membrane to induce the release of eggs and sperms [22,23].

2.3. Gonadal Index

Gonadal index (GI%) was evaluated on: (i) 10 freshly harvested specimens of the sea urchin P. lividus; (ii) 10 adults acclimatized at 18 °C for ten days; (iii) adults reared in each of the two tanks at 18 °C and in each of the two tanks at 24 °C after six weeks. These sea urchins were weighed, sacrificed, and dissected and then their gonads were weighed (fw) to evaluate of the GI [25,26,27] according to the following formula:

GI = gonadal wet weight (g)/sea urchin wet weight (g) × 100

2.4. Histological Analyses

After six weeks of treatment, gonads from 5 (3 females and 2 males) sea urchins per treatment were used for histological analysis. The peristomal membrane was incised to access the gonads, which were then blotted dry, fixed in Davidson’s solution, and processed for histological examination using hematoxylin staining. The histopathological index, adapted from Costa et al. [28] was evaluated by applying the following formula:

where w is the weight assigned to each histopathological alteration according to its relative pathological relevance, a is the diffusion score of each alteration (ranging from 0 to 6, depending on its presence across the observed microscopic fields), and M is the maximum possible value of the index, corresponding to the condition in which alterations are present at their maximum diffusion level. Random pictures were taken from each gonad using a digital camera connected to an optical microscope (Leica, DM RB, Wetzlar, Germany) [29]. The analyzed alterations included lipofuscin accumulation, follicular wall detachment, and absence or degeneration of residual gamete, observed in post-spawning gonads after the induced spawning event. The corresponding weights are reported in Table 1. The selected alterations were applied to both sexes.

Table 1.

Gonad histopathological alterations analyzed for the histopathological indices in Paracentrotus lividus in the post-spawning stage.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses for adult weights, GI, and Ih were performed by considering each mesocosm as the experimental unit. Differences between treatments were evaluated using unpaired two-tailed t-tests with Welch’s correction (Prism 3.0, GraphPad Prism 4.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Adult Growth and Gonadal Index

No significant differences were found in body weight of adult sea urchins (i) collected in the field at the beginning (freshly harvested), (ii) acclimatized for ten days at 18 °C, (iii) reared at 18 °C for six weeks, and (iv) at 24 °C for six weeks (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adult weight (in grams) and gonadal index (GI ± SD) of adult sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus collected in the field at the beginning (freshly harvested reported as t0), acclimatized to 18 °C (reported as t0 (18 °C)), reared at 18 °C (18 °C_6 weeks) and at 24 °C (24 °C_6 weeks) after six weeks.

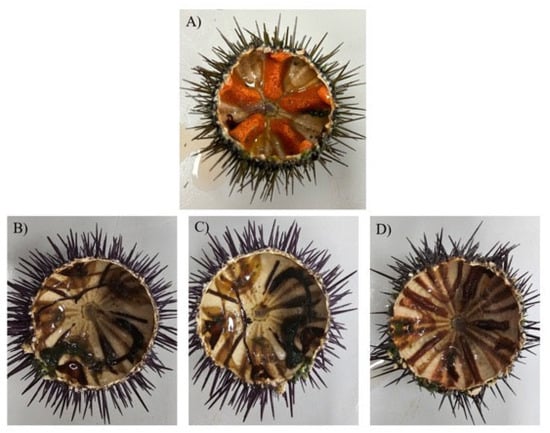

Moreover, a statistically significant decrease in the GI values in sea urchins reared at 24 °C for six weeks (1.19 ± 0.36) was observed in comparison with those reared at 18 °C for six weeks (5.14 ± 0.45), as well as when compared with freshly harvested adults (5.06 ± 0.78) and adults acclimatized for ten days at 18 °C (5.18 ± 0.69) (p < 0.05). In Figure 2, we reported pictures of the gonads from sea urchins reared at 18 °C compared with those from adults after six weeks at 24 °C.

Figure 2.

Gonads from adult sea urchin P. lividus collected in the field (A) reared at 18 °C and (B–D) reared at 24 °C for six weeks.

Adults of P. lividus showed an extensive, nearly complete gonadal retraction at 24 °C (Figure 2B–D), with a very visible reduction in size with respect to those from adults at 18 °C, and no gamete production was observed.

3.2. Histological Analyses of the Gonads

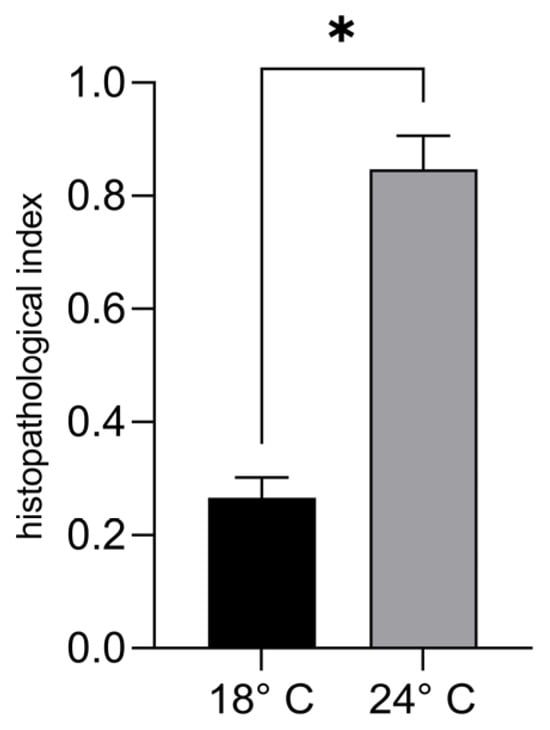

A statistically significant increase in the gonadal histopathological index was observed in sea urchins exposed to 24 °C (0.85 ± 0.059) compared to 18 °C (0.27 ± 0.04) (unpaired t-test, p < 0.05, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Gonadal histopathological index of P. lividus maintained at 18 °C and 24 °C for six weeks. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (unpaired two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction, p < 0.05; mesocosm considered as experimental unit). * Indicates statistically significant difference between treatments.

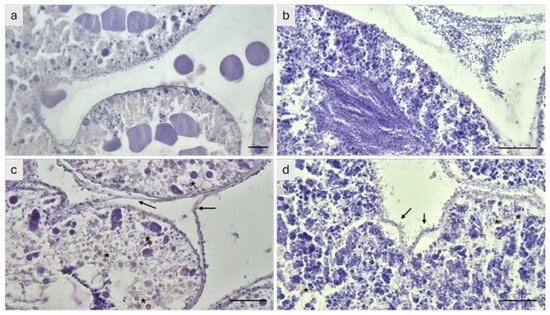

Histological examination revealed that gonads from individuals maintained at 24 °C showed marked tissue degeneration compared to the controls, with detachment of the follicular wall, accumulation of lipofuscin, and absence or degeneration of residual gametes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Histological sections of post-spawning gonads from the sea urchin P. lividus observed under light microscopy. (a) Ovary and (b) testis from control individuals showing well-preserved gonadal structures. (c) Ovary and (d) testis from individuals exposed to 24 °C displaying absence or degeneration of residual gametes. Asterisks indicate lipofuscin accumulations, and arrows point to areas of follicular wall detachment. Scale bar = 100 µm.

4. Discussion

The present research demonstrated that prolonged exposure to elevated temperature (24 °C) had a marked effect on the reproductive cycle of the sea urchin P. lividus, despite no significant changes in somatic growth. Specifically, while adult body weight remained stable across both temperature regimes over six weeks, gonadal development exhibited a profound decline in individuals maintained at 24 °C, as evidenced by a drastic reduction in the gonadosomatic index and an increment in the histopathological index.

Our findings aligned with previous studies suggesting that reproductive processes in P. lividus are highly sensitive to thermal stress [30,31]. A significant reduction in reproduction, or even complete reproductive failure, was observed over two consecutive years in several benthic invertebrate species spanning at least five different taxa [8,32]. As early as 1975, Cochran and Engelmann [33] reported that increased temperatures, even for short periods of time, such as 10 days, inhibited spawning in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Byrne et al. [31] conducted a study on the sea urchin Heliocidaris erythrogramma, demonstrating that increased temperature affected the cleavage and the gastrulation, and the development was impaired. Very recently Koch et al. [34] reported that moderate warming might boost grazing pressure, but extreme warming and acute MHWs may severely impair the population of the northern Norwegian sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis. The significant decline in GI observed at 24 °C, accompanied by almost complete gonadal retraction and absence of gametes, supports the hypothesis that elevated temperatures compromise gametogenesis.

The alterations observed at the histological level in the gonads of P. lividus exposed to 24 °C reflected a condition of tissue stress and degeneration in post-spawning phase following the experimentally induced spawning event. The lesions taken into account included lipofuscin accumulation, follicular wall detachment, and absence or degeneration of residual gametes, which together contributed to the overall increase in the histopathological index at 24 °C compared to the control temperature.

The presence of lipofuscin within gonadal tissues indicated oxidative damage and lysosomal degradation processes, often associated with cellular aging and exposure to environmental stressors [35], although a moderate accumulation may also reflect normal physiological turnover [36]. Elevated temperature likely enhanced metabolic activity and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, leading to increased deposition of this pigment, as already observed in other marine organisms, namely bivalves [37,38].

The detachment of the follicular wall suggested structural weakening of the follicular epithelium, a response commonly observed under various stress conditions [39]. Similar lesions were described in sea urchins exposed to chemical contaminants, such as antibiotics and trace metals [20,40] and a comparable mechanism may underline the thermally induced stress observed in the present study.

The absence or degeneration of residual gametes is consistent with a post-spawning condition, where remaining gametes undergo resorption or degeneration. Under natural conditions, P. lividus undergoes a well-defined annual reproductive cycle characterized by gonadal recovery and gametogenic renewal following spawning [41]. The persistence or exacerbation of degenerative patterns after the induced spawning at higher temperature may therefore indicate impaired gonadal recovery or premature tissue atrophy, consistent with stress-induced acceleration of resorption processes. This interpretation aligns with the significantly lower gonadosomatic index observed at 24 °C compared with the control group, reflecting the pronounced reduction in gonadal mass and failure to reinitiate gametogenesis under thermal stress. This is also consistent with the decrease in gonadal production observed in the sea urchin Arbacia punculata under thermal stress condition [42].

Previous work indicated that P. lividus typically exhibits optimal reproductive performance at temperatures ranging from 16 to 20 °C [43,44]. Our findings support this thermal preference and suggest that even moderate increases beyond this range can severely compromise reproductive health. Given that current climate change models predict sea surface temperature increases of 2–4 °C by the end of the century [45], our results underscore the vulnerability of P. lividus populations to future ocean warming scenarios.

Furthermore, chronic studies often show simultaneous effects on growth and gonadal development, making it hard to detect which trait is more sensitive. This study reveals that even when growth remains unaffected, reproductive tissues can undergo rapid and severe degeneration under short-term heat stress. The severe gonadal retraction and histological degeneration occurred within six weeks, showing that intense thermal anomalies can trigger reproductive failure much faster than chronic moderate warming would suggest. At the population-level consequences under short-term heatwaves, our findings indicate that brief, extreme thermal events could have disproportionate impacts on reproduction, even if adults appear healthy in terms of growth. Chronic studies might underestimate the risk of population collapse from episodic heat stress.

Interestingly, the absence of statistically significant differences in somatic growth between the two temperature treatments indicated that thermal stress selectively impacted reproductive rather than general metabolic or somatic functions over the short-to-medium term. This differential sensitivity may reflect a trade-off in resource allocation, where energy was diverted away from reproduction to support homeostasis under stressful conditions [46]. While this strategy may enhance short-term survival, it poses long-term risks for population viability if gametogenesis is chronically suppressed. The pronounced collapse of gonadal development at 24 °C, despite unchanged somatic growth, suggests a reallocation of energy away from reproduction toward physiological processes essential for survival under acute thermal stress. Energetically costly responses such as the synthesis of heat shock proteins, activation of antioxidant defenses, repair of damaged gonadal tissue, increased protein turnover, and immune system activation likely consumed resources that would otherwise support gametogenesis. This trade-off is consistent with the observed histological degeneration, including follicular wall detachment and gamete loss, indicating that short-term thermal anomalies preferentially impact reproductive investment while maintaining somatic maintenance. For instance, elevated temperature often induces heat shock proteins (HSPs), which act as molecular chaperones but incur substantial ATP costs [47]. Similarly, thermal stress can enhance oxidative stress (reactive oxygen species), leading to the upregulation of antioxidant defenses and apoptosis, both of which are metabolically expensive [48]. Immune activation is another likely sink: in sea urchins, heat stress can modify coelomocyte activity, mitochondrial function, and redox balance, suggesting immune system engagement under acute warming [49]. Such processes, including protein repair, apoptosis, and immune responses, could divert resources away from gametogenesis, explaining the gonadal degeneration observed. Overall, the combined occurrence of reduced GSI and increased histopathological index, supports the interpretation that elevated temperature exacerbates oxidative and structural stress in post-spawning gonads, limiting their capacity to recover and initiate a new gametogenic cycle, with potential consequences on reproduction and population dynamics. While a single acute heatwave caused a complete cessation of gamete production, surviving adults could potentially reproduce in the following season, suggesting a skipped reproductive event rather than immediate local extinction. However, repeated or consecutive heatwaves could prevent the recovery of gonadal function, reducing recruitment over multiple years and posing a serious risk to population persistence. The results emphasize the need for continued research on the long-term impacts of climate change on reproductive biology and underscore the importance of integrating physiological thresholds into conservation and management strategies for ecologically and economically important echinoid species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmse13122293/s1, Table S1: Values of sea water parameters of NH3, NO2, NO3, PO4, temperature (°C), pH, O2 and salinity (%) for tanks V1 and V2 at 18 °C and V3 and V4 at 24 °C measured each week during the whole experiment.

Author Contributions

A.D.C., G.P., V.Z. and M.C. conceptualized and designed the study; A.A. and T.R. performed laboratory activities and analyzed the data; D.C. and A.M. performed chemical and physical analysis of the sea water in the experimental tanks; A.A. and T.R. led the writing of the manuscript, under the supervision of A.D.C., G.P., V.Z. and M.C. All authors critically contributed to the drafts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted in the framework of the Project—Biomonitoraggio di micro e nanoplastiche biodegradabili: dall’ambiente all’uomo in una prospettiva one health (BioPlast4Safe)—with the technical and economic support of the Italian Ministry of Health—PNC (PREV-B-2022-12377008).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Amalia Amato was supported by a PhD fellowship (Ph.D. in Biology, University of Naples Federico II) funded by the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn (Naples, Italy) in the framework of the Project BioPlast4Safe.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Frölicher, T.L.; Fischer, E.M.; Gruber, N. Marine Heatwaves under Global Warming. Nature 2018, 560, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Yin, X.; Carton, J.A.; Chen, L.; Graham, G.; Hibbert, K.; Lee, S.; Smith, T.; Zhang, H.-M. Extreme Marine Heatwaves in the Global Oceans during the Past Decade. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, 106, E2017–E2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernberg, T.; Smale, D.A.; Tuya, F.; Thomsen, M.S.; Langlois, T.J.; De Bettignies, T.; Bennett, S.; Rousseaux, C.S. An Extreme Climatic Event Alters Marine Ecosystem Structure in a Global Biodiversity Hotspot. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.E.; Pershing, A.J.; Brown, C.J.; Chen, Y.; Chiang, F.S.; Holland, D.S.; Lehuta, S.; Nye, J.A.; Sun, J.C.; Thomas, A.C.; et al. Fisheries Management in a Changing Climate: Lessons from the 2012 Ocean Heat Wave in the Northwest Atlantic. Oceanography 2013, 26, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, N.; Kangas, M.; Denham, A.; Feng, M.; Pearce, A.; Hetzel, Y.; Chandrapavan, A. Management Adaptation of Invertebrate Fisheries to an Extreme Marine Heat Wave Event at a Global Warming Hot Spot. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 3583–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, E.C.J.; Donat, M.G.; Burrows, M.T.; Moore, P.J.; Smale, D.A.; Alexander, L.V.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Feng, M.; Sen Gupta, A.; Hobday, A.J.; et al. Longer and More Frequent Marine Heatwaves over the Past Century. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, J.A.; Chepurin, G.A.; Hackert, E.C.; Huang, B. Remarkable 2023 North Atlantic Ocean Warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL112551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.; Burrows, M.T.; Hobday, A.J.; King, N.G.; Moore, P.J.; Gupta, A.; Thomsen, M.S.; Wernberg, T.; Smale, D.A. Biological Impacts of Marine Heatwaves. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2023, 15, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontheaux, F.; Roch, F.; Morales, J.; Cormier, P. Echinoderms: Focus on the Sea Urchin Model in Cellular and Developmental Biology. In Handbook of Marine Model Organisms in Experimental Biology: Established and Emerging; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupi, V. A Study on the Food Web of the Posidonia Oceanica Ecosystem: Analysis of the Gut Contents of Echinoderms. In International Workshop on Posidonia oceanica Beds 1; GIS Posidonie Publishing: Marseille, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, N.; Agatsuma, Y.; Ballesteros, E.; Bazhin, A.; Bradbury, A.; Campbell, A.; Dixon, J.; Einarsson, S.; Gerring, P.; Hebert, K.; et al. Status and Management of World Sea Urchin Fisheries. In Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review; Gibson, R., Barnes, M., Atkinson, R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; Volume 40, pp. 343–425. [Google Scholar]

- Boudouresque, C.; Verlaque, M. Ecology of Paracentrotus lividus. In Developments in Aquaculture and Fisheries Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 37, pp. 243–285. [Google Scholar]

- Raposo, A.; Ferreira, S.M.F.; Ramos, R.; Anjos, C.; Gonçalves, S.C.; Santos, P.M.; Baptista, T.; Costa, J.L.; Pombo, A. Reproductive Cycle of the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) on the Central West Coast of Portugal: New Perspective on the Gametogenic Cycle. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, M.; Glaviano, F.; Federico, S.; Pinto, B.; Cosmo, A.; Costantini, M.; Zupo, V. Scale-Up of an Aquaculture Plant for Reproduction and Conservation of the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus: Development of Post-Larval Feeds. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, F.; Romero, J.; Turon, X. Settlement and Recruitment of the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus in Two Contrasting Habitats in the Mediterranean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004, 282, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J. Edible Sea Urchins: Use and Life-History Strategies. In Developments in Aquaculture and Fisheries Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 37, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ruberti, N.; Brundu, G.; Ceccherelli, G.; Grech, D.; Guala, I.; Loi, B.; Farina, S. Intensive Sea Urchin Harvest Rescales Paracentrotus Lividus Population Structure and Threatens Self-Sustenance. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacentini, L.; El Idrissi, O.; Monnier, B.; Vela, A.; Bastien, R.; Aiello, A.; Pasqualini, V.; Ternengo, S. Spatio-Temporal Monitoring and Modeling Approach for the Sustainable Management of Paracentrotus lividus Populations in the Mediterranean Sea. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 62, e03796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M. Impact of Ocean Warming and Ocean on Marine Invertebrate Life History Stages: Vulnerabilities and Potential for Persistence in a Changing Ocean. In Oceanography and Marine Biology; Gibson, R., Atkinson, R., Gordon, J., Smith, I., Hughes, D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; Volume 49, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sarly, M.S.; Pedro, C.A.; Bruno, C.S.; Raposo, A.; Quadros, H.C.; Pombo, A.; Gonçalves, S.C. Use of the Gonadal Tissue of the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus as a Target for Environmental Contamination by Trace Metals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 89559–89580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.F.; Lourenço, S.; Gomes, A.S.; Tchobanov, C.F.; Pombo, A.; Baptista, T. How Increasing Temperature Affects the Innate Immune System of Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) Reared in a RAS System. Comp. Immunol. Rep. 2024, 7, 200174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruocco, N.; Bertocci, I.; Munari, M.; Musco, L.; Caramiello, D.; Danovaro, R.; Zupo, V.; Costantini, M. Morphological and Molecular Responses of the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus to Highly Contaminated Marine Sediments: The Case Study of Bagnoli-Coroglio Brownfield (Mediterranean Sea). Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 154, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viel, T.; Cocca, M.; Esposito, R.; Amato, A.; Russo, T.; Di Cosmo, A.; Polese, G.; Manfra, L.; Libralato, G.; Zupo, V.; et al. Effect of Biodegradable Polymers upon Grazing Activity of the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lmk) Revealed by Morphological, Histological and Molecular Analyses. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruocco, N.; Zupo, V.; Caramiello, D.; Glaviano, F.; Polese, G.; Albarano, L.; Costantini, M. Experimental Evaluation of the Feeding Rate, Growth and Fertility of the Sea Urchins Paracentrotus lividus. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 2018, 62, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-España, A.I.; Martínez-Pita, I.; García, F.J. Gonadal Growth and Reproduction in the Commercial Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) from Southern Spain. Hydrobiologia 2004, 519, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrocini, A.; D’Adamo, R. Gametes and Embryos of Sea Urchins (Paracentrotus lividus, Lmk., 1816) Reared in Confined Conditions: Their Use in Toxicity Bioassays. Chem. Ecol. 2011, 27, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M.; Kamrani, E.; Biuki, N.A.; Zamani, H. Study on the Gonadosomatic Indices of Sea Urchin Echinometra mathaei in Persian Gulf, Iran. Pak. J. Zool. 2017, 49, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Carreira, S.; Costa, M.; Caeiro, S. Development of Histopathological Indices in a Commercial Marine Bivalve (Ruditapes decussatus) to Determine Environmental Quality. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 126, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, T.; Coppola, F.; Leite, C.; Carbone, M.; Paris, D.; Motta, A.; Di Cosmo, A.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Mollo, E.; Freitas, R.; et al. An Alien Metabolite vs. a Synthetic Chemical Hazard: An Ecotoxicological Comparison in the Mediterranean Blue Mussel. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guettaf, M.; San Martin, G.A.; Francour, P.; Alia, E.; Ezzouar, B. Interpopulation Variability of the Reproductive Cycle of Paracentrotus lividus (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) in the South-Western Mediterranean. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2000, 80, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.; Ho, M.; Selvakumaraswamy, P.; Nguyen, H.D.; Dworjanyn, S.A.; Davis, A.R. Temperature, but Not PH, Compromises Sea Urchin Fertilization and Early Development under near-Future Climate Change Scenarios. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2009, 276, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanks, A.L.; Rasmuson, L.K.; Valley, J.R.; Jarvis, M.A.; Salant, C.; Sutherland, D.A.; Lamont, E.I.; Hainey, M.A.H.; Emlet, R.B. Marine Heat Waves, Climate Change, and Failed Spawning by Coastal Invertebrates. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2020, 65, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, R.C.; Engelmann, F. Environmental Regulation of the Annual Reproductive Season of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (Stimpson). Biol. Bull. 1975, 148, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Jungblut, S.; Götze, S.; Bock, C.; Saborowski, R. Marine Heatwaves in the Subarctic and the Effect of Acute Temperature Change on the Key Grazer Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis (Echinoidea, Echinodermata). ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2025, 82, fsae181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrìguez-Villalobos, J.; Arellano-Martìnez, M.; Ceballos-Vàzquez, B. Histopathological Effects of Heavy Metal on Bivalves: Review and Perspectives. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaschenko, M.A.; Zhadan, P.M.; Aminin, D.L.; Almyashova, T.N. Lipofuscin-like Pigment in Gonads of Sea Urchin Strongylocentrotus intermedius as a Potential Biomarker of Marine Pollution: A Field Study. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012, 62, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, C.; Russo, T.; Cuccaro, A.; Pinto, J.; Polese, G.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Pretti, C.; Pereira, E.; Freitas, R. Can Temperature Rise Change the Impacts Induced by E-Waste on Adults and Sperm of Mytilus galloprovincialis? Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 902, 166085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittura, L.; Nardi, A.; Cocca, M.; De Falco, F.; d’Errico, G.; Mazzoli, C.; Mongera, F.; Benedetti, M.; Gorbi, S.; Avella, M.; et al. Cellular Disturbance and Thermal Stress Response in Mussels Exposed to Synthetic and Natural Microfibers. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 981365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, S.; Köhler, A. Gonadal Lesions of Female Sea Urchin (Psammechinus miliaris) after Exposure to the Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Phenanthrene. Mar. Environ. Res. 2009, 68, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ayari, T.; Ahmed, R.; Bouriga, N.; Gravato, N.; Chelbi, E.; Nechi, S.; El Menif, N. Florfenicol Induces Malformations of Embryos and Causes Altered Lipid Profile, Oxidative Damage, Neurotoxicity, and Histological Effects on Gonads of Adult Sea Urchin, Paracentrotus lividus. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 110, 104533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, M. Annual Reproductive Cycles of the Commercial Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus from an Exposed intertidal and a Sheltered Subtidal Habitat on the West Coast of Ireland. Mar. Biol. 1990, 104, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, J.B.; Nash, S.; Hernandez, E.; Rahman, M. Effects of Elevated Temperature on Gonadal Functions, Cellular Apoptosis, and Oxidative Stress in Atlantic Sea Urchin (Arbacia punctulata). Mar. Environ. Res. 2019, 149, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirlet, C.; Grosjean, P.; Jangoux, M. Reproductive Cycle of the Echinoid Paracentrotus lividus: Analysis by Means of the Maturity Index. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 1998, 34, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrotti, M.L.; Fenaux, L. Dispersal of Echinoderm Larvae in a Geographical Area Marked by Upwelling (Ligurian Sea, NW Mediterranean). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1992, 86, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, R.M.; Acevedo, J.; Treml, E.A. Three Decades of Ocean Warming Impacts on Marine Ecosystems: A Review and Perspective. Deep Sea Res. II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2023, 212, 105318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, I.M.; Frederich, M.; Bagwe, R.; Lannig, G.; Sukhotin, A.A. Energy Homeostasis as an Integrative Tool for Assessing Limits of Environmental Stress Tolerance in Aquatic Invertebrates. Mar. Environ. Res. 2012, 79, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagar Boopathy, L.R.; Jacob-Tomas, S.; Alecki, C.; Vera, M. Mechanisms Tailoring the Expression of Heat Shock Proteins to Proteostasis Challenges. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Li, G.; Wang, G.; Lu, L. Effects of Heat Stress on Antioxidant Defense System, Inflammatory Injury, and Heat Shock Proteins of Muscovy and Pekin Ducks: Evidence for Differential Thermal Sensitivities. Cell Stress Chaperones 2014, 19, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murano, C.; Gallo, A.; Nocerino, A.; Macina, A.; Cecchini Gualandi, S.; Boni, R. Short-Term Thermal Stress Affects Immune Cell Features in the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus. Animals 2023, 13, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).