Abstract

Offshore tubular pile systems in earthquake-active marine regions face risks from vertical seismic excitation, water dynamics, and pile–soil interactions. Thus, an analytical solution for offshore tubular piles considering multi-physical field coupling (the mutual interactions between seawater, tubular pile, and surrounding soil) is developed to investigate their dynamic responses under vertical seismic loading. Firstly, the dynamic response of the tubular pile system is decomposed into free-field and scattered-field components. The governing equations for water, soil, and tubular piles (one-dimensional and three-dimensional tubular pile models) are established, with the strict enforcement of boundary conditions such as displacement continuity and stress equilibrium. Then, analytical solutions for both one-dimensional and three-dimensional tubular pile models are derived. The proposed framework is validated by comparison with existing literature solutions, confirming its rationality. Subsequently, parametric analyses are conducted to explore the influences of key factors. The results indicate that it is essential to consider the coupled effects of vertical earthquakes and water–pile–soil interaction in the design of offshore tubular piles, as neglecting multi-field coupling or adopting oversimplified models can lead to inaccurate predictions of dynamic responses.

1. Introduction

Offshore tubular pile foundations serve as critical structural components for various marine infrastructures, such as offshore wind turbines (OWTs) [1,2,3,4,5], oil and gas platforms [6], and submarine pipelines [7], which are increasingly exposed to seismic hazards in active tectonic regions. The dynamic response of these piles under vertical seismic excitation is governed by complex multi-physical interactions involving seawater, pile materials, and surrounding soils [8,9], posing significant challenges for accurate prediction and reliable design. Unlike onshore pile systems, offshore tubular piles must withstand the combined effects of hydrodynamic pressure, soil radial confinement, and axial vibration inertia [10,11], making their seismic behavior far more intricate and less understood compared to their onshore counterparts.

Extensive research has been dedicated to pile–soil interaction (PSI) under seismic loads, forming the theoretical cornerstone for dynamic analysis [12,13]. However, these early frameworks largely neglected the influence of seawater [14], limiting their direct applicability to offshore scenarios where the water–pile interaction (WPI) becomes dominant. The integration of WPI into pile dynamic analysis has emerged as a research focus over the past few decades [15,16,17]. For infinite water domains, Wang et al. [18] derived a precise time-domain solution for water–cylinder coupling, though their model did not incorporate soil constraints, which are indispensable for offshore piles.

Recent studies have begun to bridge WPI and PSI [19,20,21,22,23,24]. However, most of these works focus on horizontal excitation [25,26], leaving vertical seismic effects, particularly relevant for end-bearing piles transmitting axial loads, under-explored. Moreover, the separation of free-field and scattered-field responses, crucial for isolating incident wave effects from pile-induced perturbations [27], has rarely been integrated into comprehensive water–pile–soil coupling frameworks.

Model dimensionality represents another pivotal factor governing the accuracy of response predictions. Traditional one-dimensional models simplify tubular piles as axially vibrating rods [28], prioritizing computational efficiency by capturing axial stiffness–mass balance. For instance, Zheng et al. [29] analyzed the transverse seismic responses of end-bearing tubular piles using a simplified continuum model but omitted radial WPI and three-dimensional soil scattering. Such simplifications are valid for purely axial vibration dominated by pile inertia [30], but fail when radial deformation and multi-field coupling become significant [31]. In contrast, three-dimensional tubular pile models incorporate both axial and radial vibrations [32], enabling the simulation of pile–water radial extrusion [33] and soil wave scattering in multiple directions [34]. Iovino et al. [35] demonstrated that 3D soil responses enhance pile constraint via radial normal stress, while Stacul et al. [36] highlighted the role of 3D PSI in nonlinear seismic behavior. Despite these advances, systematic comparisons between one-dimensional and three-dimensional tubular pile models under vertical seismic excitation, particularly in terms of parameter sensitivity across different dimensional configurations, remain lacking [37].

While existing research has advanced our understanding of offshore piles, several notable gaps persist. At present, most studies rely on land-based seismic motion records as input [38], overlooking the significant impacts of both seawater and soil scattering fields on the dynamic response of piles-particularly in the vicinity of P-wave resonance frequencies [39,40]. In addition, existing investigations into the seismic response of offshore tubular piles typically examine structural impacts under isolated conditions [41,42], failing to account for how the water-pile-soil coupling effect modulates pile behavior across diverse environmental scenarios [43,44]. This oversight is particularly critical for engineering practice: offshore tubular piles in real marine environments are never subjected to a single varying factor. For example, increased water depth not only amplifies hydrodynamic pressure but also interacts with pile wall thickness to alter the pile’s radial stiffness, which directly impacts seismic response accuracy.

To address these critical research gaps, this study develops a comprehensive analytical framework for the vertical seismic response of offshore end-bearing tubular piles, centered on multi-physical field coupling. Unlike previous works that treat parameters in isolation, this framework explicitly integrates the combined effects of geometric and environmental parameters, and quantifies how these combinations regulate responses across one-dimensional and three-dimensional tubular pile models configurations. To achieve this, the system response is decomposed into free-field and scattered-field components. This decomposition allows for clear isolation of how parameter coupling modifies both original seismic inputs and pile-generated disturbances. Governing equations are further derived for each medium: water dynamics via velocity potential theory, soil behavior via three-dimensional elastic wave propagation, and tubular piles via contrasting one-dimensional axial vibration and three-dimensional tubular pile axial–radial coupling. Validation against the existing literature solutions ensures the framework’s reliability. Parametric analyses then explore the effects of model dimensionality, water depth and geometric parameters (radius, wall thickness). The goal is to clarify the mechanisms driving response differences between one-dimensional and three-dimensional models and provide theoretical guidance for the seismic design of offshore tubular pile foundations.

2. Synopsis of Theoretical Frameworks

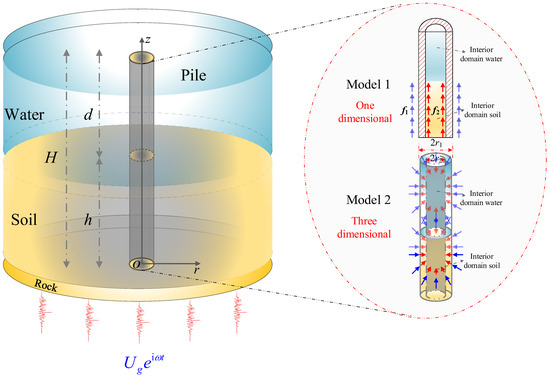

Figure 1 depicts the coupled system under investigation, comprising four key components—water layer, tubular pile (one-dimensional and three-dimensional models), soil strata, and bedrock. In this, the soil thickness, water depth, tubular pile inner and outer radius are h, d, r2 and r1, respectively. Additionally, vertical earthquake travels upward from the rigid bedrock, defined by the displacement–time function (where stands for the displacement amplitude, is the circular vibration frequency, and is the imaginary unit).

Figure 1.

Tubular pile system under vertical earthquake.

Based on earlier research [45,46], the dynamic ground response of a hollow cylindrical structure submerged in a fluid is mainly controlled by its intrinsic vibration effects, with the influence of free-surface waves being much less prominent. For this reason, the dynamic analysis model developed herein does not currently incorporate higher-order coupling terms related to free-surface wave effects.

As schematically presented in Figure 1, a key assumption is that there is no relative movement at the tubular pile bottom. The water is modeled as an inviscid and irrotational. This dual assumption is a well-accepted simplification in fluid–structure interaction analyses for offshore structures, as it balances computational tractability with the need to retain the critical water-induced effects that influence tubular pile seismic responses, without introducing unnecessary complexity from secondary fluid properties [6,7,8]. The soil is simplified as a homogeneous single phase. In this model, perfect contact is assumed between the rock, the external water (around the tubular pile), the internal water (within the tubular pile), the outer soil, and the inner soil.

2.1. Fundamental Equation for Water

In the pile’s absence, using linear radiation wave theory, the governing expression for the free-field water velocity potential is derived below.

However, in the case where the tubular pile is a three-dimensional solid, the dynamic equation of water velocity potential should be composed of the above free-field response and the following scattering-field response, which can be expressed as follows:

where and and and are the free field and scattered field of water velocity potential, respectively (where j = 1 and j = 2 represent outer water and inner water).

2.2. Fundamental Equation for Soil

The free-field soil (in the absence of tubular pile) has a one-dimensional displacement response under vertical vibration excitation. Thus, the kinematic response of the soil can be expressed as and .

Free-field response:

Scattered-field response:

where is the Laplace operator; and are the vertical displacements of the soil in the free and scattered field, respectively; is the radial displacement of the soil (j = 1 and j = 2 representing outer soil and inner soil); and is the complex Lamé constant of soil; and , , and are the shear modulus, hysteretic damping, mass density, elasticity modulus and Poisson’s ratio of soil, respectively.

2.3. Fundamental Equation for Tubular Pile

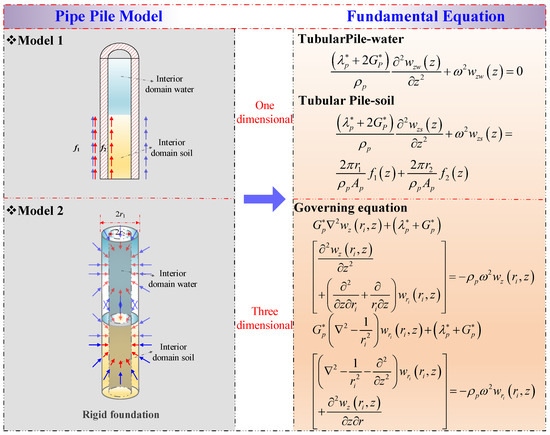

The fundamental equations for one-dimensional and three-dimensional tubular piles can be expressed as the formulas shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Governing equations under distinct tubular pile conditions.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the displacement of the tubular pile in the water segment is defined by Equation (6), while the displacement of the tubular pile in the soil segment is given by Equation (7). Furthermore, the radial and vertical displacements of the pile can be denoted as and (i = 1 representing outer soil and i = 2 denotes inner soil), respectively. Analogous to the soil, the coupling equations for the vertical and radial displacements of the pile are presented in Figure 2.

In Figure 2, in which , , and represent the vertical displacement of the submerged section of the tubular pile in water and soil, the frictional resistance inside and outside the tubular pile, respectively,, , and are the complex Lamé constant, density, cross-sectional area and mass density of the tubular pile, respectively.

2.4. Boundary Conditions

(1) Top conditions of the system

where are the tubular pile normal stress (in the z direction). In addition, Equation (7) only applies to the second type of tubular pile model, which is when the tubular pile is a three-dimensional model. When the free surface waves of the water are ignored, the boundary condition (7) transforms to .

(2) Interface between soil and water:

where is the water density; and represent the vertical normal stress of the soil in the free field and scattered field, respectively. The scattered-field soil-water interaction is not considered. Equation (12) becomes Equation (13).

That is to say, when the tubular pile model is in the first situation, the boundary conditions integrate Equations (9), (10) and (12). If the pile model is in the second situation, the boundary conditions integrate Equations (9)–(11) and (13).

(3) Bottom conditions of the system

(4) Interface between outer soil and tubular pile when adopting model 1 of the tubular pile (one-dimensional model):

Interface between outer soil and tubular pile when adopting model 2 of the tubular pile (three-dimensional model):

where and are the soil normal stress and the soil shear stress (in the r direction), respectively; and and are the pile normal stress and the pile shear stress (in the r direction), respectively.

(5) Interface between inner soil and tubular pile when adopting model 1 of the tubular pile (one-dimensional model):

Interface between inner soil and tubular pile when adopting model 2 of the tubular pile (three-dimensional model):

(6) Tubular pile section when adopting model 1 of the tubular pile (one-dimensional model):

(7) Interface between outer water and tubular pile when adopting model 2 of the tubular pile (three-dimensional model):

(8) Interface between inner water and tubular pile when adopting model 2 of the tubular pile (three-dimensional model):

(9) Infinity soil whether using tubular pile model 1 or model 2:

(10) Finite soil whether using tubular pile model 1 or model 2:

In which stresses can be represented as

where .

(11) Infinite water when adopting model 2 of the tubular pile (three-dimensional model):

3. Determining Solutions

3.1. Free-Field Motion (Applicable to the First and Second Types of Tubular Pile Model)

3.1.1. Outer Domain (j = 1)

Equations (1) and (3) solutions can be expressed as follows:

where , , , and are coefficients that need to be determined.

Upon incorporating Equations (48) and (49), within the framework constructed from conditions (9), (10), and (14), can be obtained as

where is shown in Appendix A.

3.1.2. Inner Domain (j = 2)

3.2. Scattered-Field Motion

3.2.1. Outer Water Motion (j = 1)

The governing Equation (2) can be expressed as (only applicable to three-dimensional model of tubular pile) follows:

By means of separation of variables, the general solution to Equation (56) is derived as follows:

with

where , , , and are undetermined coefficients; and and are 0th-order modified Bessel functions of the first and second kind, respectively.

Substituting Equation (55) into Figure 2, Equations (11) and (46) yields

where is undetermined coefficient, and (water modes) can be obtained by solving the following virtual transcendental equations.

When the free surface wave is ignored, the boundary condition (58) transforms to , , and can be obtained through Equation (56) by letting .

3.2.2. Inner Water Motion (j = 2)

Similarly, the inner water domain can be expressed as

Substituting Equation (63) into Equations (11), (15) and (51) yields

3.2.3. Outer Soil Motion (j = 1)

According to Helmholtz decomposition principle and separation of variable methods, and combined with boundary conditions (15), (18), (39), and (40), the radial and vertical displacements of the outer soil can be expressed as (the specific solution process can be found in Appendix B)

where (soil modes) can be found in Appendix B

Thus, due to Equation (62) and boundary conditions (19), the scattering-field displacement between the tubular pile and the outer soil can be obtained as (one-dimensional model, without radial displacement) follows:

where and are shown in Appendix A.

3.2.4. Inner Soil Motion (j = 2)

Unlike the boundary conditions of the outer soil, the boundary conditions of the inner soil become (15), (25), (41), and (42). Thus, the radial and vertical displacements of the inner soil can be expressed as follows:

where the above unknown coefficients can be referred to the situation of the outer domain soil.

3.3. Determining Solutions for the Tubular Pile

3.3.1. One-Dimensional Model of Tubular Pile

Upon substituting Equations (64) and (68) into Figure 2, the resulting expressions are found as follows

where .

The forms of the general and specific solutions mentioned above are easy to obtain. Through some formula transformations, they can be obtained as

where and can be found in Appendix A.

After some operations (the specific solution process can be found in Appendix C)

In Figure 2, Pile-water interaction leads to the following general solutions

where and are coefficients that need to be determined.

Substituting Equations (71) and (72) into Equations (8), (16), (31), and (32) yields

where and are shown in Appendix A.

Solving Equation (73) yields the values of , , and . Substituting these coefficients into the equations for the outer soil, inner soil, and tubular pile then gives the system’s solution.

3.3.2. Three-Dimensional Model of Tubular Pile

For a three-dimensional tubular pile model, analogous to the approach employed in soil analysis, the governing equations of pile are decomposed using Helmholtz decomposition alongside consideration of boundary conditions (8) and (16) allows the total displacement of the pile to be derived as follows:

where , and , , and are undetermined coefficients; and .

The combination of Equations (57), (59), (61), (62), (65), (66), (74) and (75), considering the boundary conditions at the tubular pile–water and tubular pile–soil interfaces (20)–(23), (27)–(30), (33)–(35), and (36)–(38), combined with the orthogonality of trigonometric functions, can be expressed in the following form:

Outer and inner soil–tubular pile–outer water interaction can be presented as

There are some manipulations to

where the parameters in the matrix are shown in Appendix D.

Two dimensionless ratios are introduced in this study to serve as quantitative metrics. The first, designated as . Meanwhile, the second, marked as , their definitions are presented below.

4. Convergence and Verifying of Model

Table 1 presents the core parameters employed in this research. Notably, this study did not incorporate detailed material property data or actual marine environmental parameters. As a result, the parameter set utilized may not fully align with the realistic conditions encountered in practical engineering scenarios, and caution should be exercised when extrapolating these results to on-site applications.

Table 1.

The critical parameters.

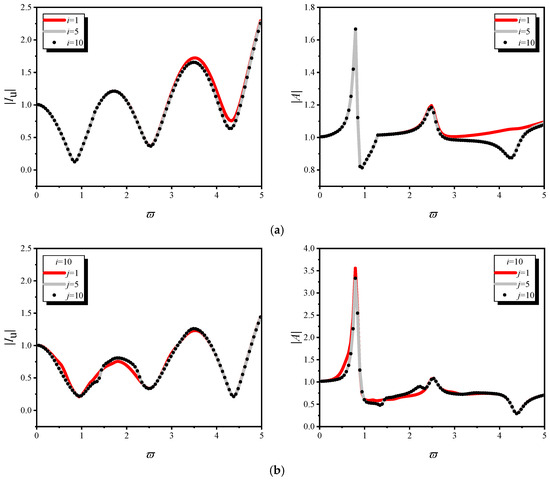

4.1. Convergence Analysis

The solution given above, where the variables i and j contained in the formula are infinite, requires convergence analysis for them. As illustrated in Figure 3, the values of the quantitative indicators begin to stabilize (exhibit convergence) once both i and j exceed 10 (assuming that after a certain number of iterations, the variation range error of soil modes is within 3%). On this basis, for the parameter analysis conducted in subsequent sections, the indices i and j are fixed at 10.

Figure 3.

Convergence analysis under distinct tubular pile conditions. (a) One-dimensional presentation of tubular pile. (b) Three-dimensional presentation of tubular pile.

In addition, the dimensionless frequency ϖ can be represented as follows:

where , and is the soil natural frequency.

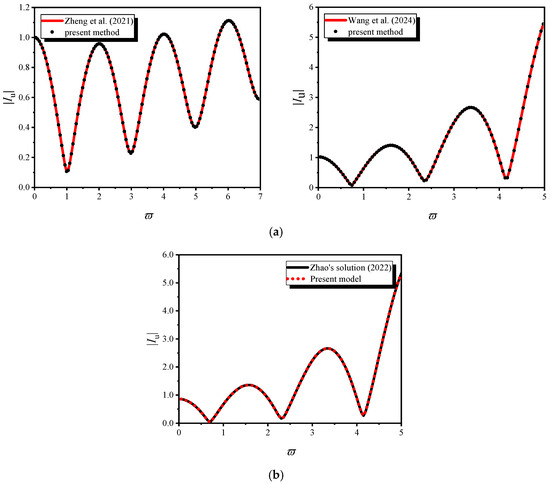

4.2. Verifying

To verify the rationality of the solution developed in this study, cross-validations against results from existing academic literature are conducted.

In the first validation step, by setting H = h, the proposed model is simplified into an analytical model for tubular pile–soil interaction. Outcomes derived under this configuration are subsequently benchmarked against the solutions documented in Zheng’s and Wang’s studies [47,48], with the comparative results illustrated in Figure 4a. In the second validation step, through a targeted parameter adjustment (with specifics defined), the study’s model is further reduced to an analytical model for solid piles. Results acquired in this scenario are compared against the findings reported in Zhao’s research [14] are used, as visualized in Figure 4b. In conclusion, when the present solution is condensed into a tubular pile–soil model, it demonstrates high consistency with the results in Zheng’s and Wang’s studies; similarly, when simplified into a solid pile model, it exhibits strong alignment with the findings in Zhao’s research.

Figure 4.

Comparisons with other methods of |Iu|: (a) one-dimensional model; (b) three-dimensional model [14,47,48].

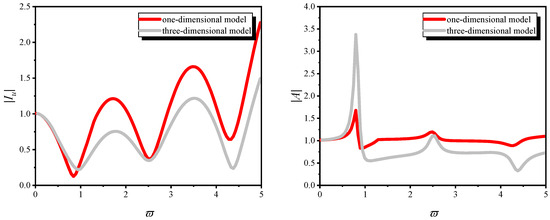

5. Mechanism Analysis

5.1. Distinctive Effects of the Scattering Field

Figure 5 focuses on the tubular pile system, considering water–pile–soil interactions under vertical seismic excitation, and comparatively presents the core differences in scattered field responses between one-dimensional and three-dimensional tubular pile models. The abscissa represents the dimensionless frequency (the relative relationship between the excitation frequency and the natural frequency of the soil), and the ordinate denotes the key index, with and characterizing the system’s dynamic response. The analysis is based on the core parameters specified in Table 1. The response differences between the two sub-figures in Figure 5 essentially arise from the differing levels of accuracy with which the one-dimensional and three-dimensional tubular pile models capture the “water–tubular pile–soil coupling mechanism”; these differences exhibit a strong frequency dependence on the dimensionless frequency. The specific mechanisms are detailed as follows:

Figure 5.

Comparison of scattering-field dynamic response of one-dimensional and three-dimensional tubular pile models considering water–pile–soil interaction under vertical seismic excitation.

- (1)

- The absence of a tubular pile–water coupling effect: The one-dimensional tubular pile model simplifies the pile to an “axial vibration rod” with radial displacement neglected, thereby completely neglecting the tubular pile–water interaction. In contrast, in the three-dimensional tubular pile model, the radial vibration of the tubular pile squeezes the inner and outer water, generating a scattered field water response. Through the “added mass method”, the water imposes an equivalent distributed mass on the pile, and meanwhile, additional damping is supplied by hydrodynamic pressure. The added mass raises the vibration inertia of the pile, and damping disperses vibration energy. Both factors jointly suppress the pipe vibration amplitude in the three-dimensional tubular pile model. While the one-dimensional model lacks such restrictive effects, it naturally yields a larger dynamic response.

- (2)

- Constraint contribution from soil’s three-dimensional response: In the one-dimensional tubular pile model, only the axial response of the soil is considered, and the constraint on the pile is merely reflected as axial friction, ignoring the constraint effect of radial normal stress (equivalent to “the pile can deform freely in the radial direction within the soil”). This results in relatively low overall constraint stiffness. In the three-dimensional tubular pile model, the soil achieves a combined radial–axial response through Helmholtz decomposition. The radial displacement of the pile causes radial compression of the soil, and the soil forms a strong constraint on the pile via radial normal stress. Meanwhile, three-dimensional soil response couples the propagation of longitudinal and shear waves in the soil, further amplifying the soil’s vibration suppression effect on the pile. This “bidirectional constraint” makes the vibration stiffness of the pile in the three-dimensional tubular pile model significantly higher than that in the one-dimensional tubular pile model. Therefore, under the same excitation, the response of the three-dimensional tubular pile model is smaller, while that of the one-dimensional tubular pile model is larger.

- (3)

- The simplification defect of the scattered field in the one-dimensional tubular pile model: The one-dimensional tubular pile model only accounts for the axial scattering of the soil, induced by the pile’s axial vibration, without the contribution of radial and water scattering, and the scattered field is dominated by a few low-order modes. At high frequencies, this simplification leads to two key problems: first, the stiffness of the soil’s axial response decreases rapidly with increasing frequency (the soil exhibits obvious visco-elasticity at high frequencies, and axial friction attenuates), causing the pile to lose effective constraint; second, the one-dimensional tubular pile model has no multi-order modal energy dissipation paths. As a result, vibration energy cannot be dissipated through radial scattering or water–soil coupling, but only slowly through axial friction. However, the dissipation efficiency of axial friction at high frequencies is much lower than that of multi-field scattering in the three-dimensional tubular pile model. The superposition of these two factors results in the one-dimensional model exhibiting a larger response amplitude in the high-frequency range compared to the three-dimensional model.

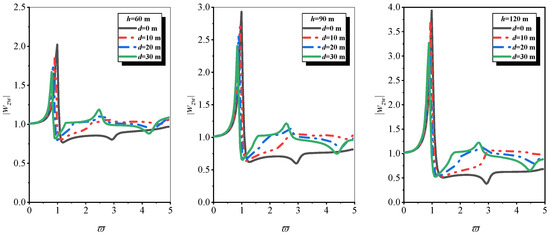

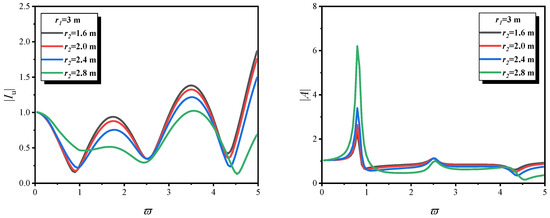

5.2. Distinctive Effects of the Water Depth

Figure 6 and Figure 7 focus on the variation trend of the absolute value of pile top displacement with water depth under different soil thicknesses under vertical seismic excitation. As can be seen from Figure 6 and Figure 7, under vertical seismic excitation and with fixed soil thickness, the peak value of pile top displacement of the one-dimensional tubular pile model shows an attenuation trend with the increase in water depth, while that of the three-dimensional tubular pile model shows an increasing trend with the increase in water depth. Moreover, the frequency corresponding to the peak value in both models shifts to the low-frequency band as water depth increases. The reasons for the above phenomena are as follows.

Figure 6.

The trend of displacement of pile top with water depth under vertical seismic excitation and constant soil thickness (one-dimensional representation of tubular pile).

Figure 7.

The trend of displacement of pile top with water depth under vertical seismic excitation and constant soil thickness (three-dimensional representation of tubular pile).

- (1)

- The one-dimensional tubular pile model simplifies the tubular pile into a “force rod” that only vibrates along the axial direction, ignoring radial deformation and three-dimensional coupling. When water depth increases, the “added mass effect” (more water interacts with the pile, increasing the equivalent vibration mass of the pile) and the “hydrodynamic damping effect” (the viscous and radiation damping at the pile–water interface are enhanced, dissipating vibration energy) dominate jointly. The added mass enhances the vibration inertia, while hydrodynamic damping mitigates energy concentration; these two factors jointly suppress the peak displacement of the pile top. Meanwhile, the growth of added mass lowers the system’s natural frequency, causing the frequency corresponding to the peak to shift toward the low-frequency range.

- (2)

- The three-dimensional tubular pile model considers the axial and radial coupled vibration of the tubular pile as well as the pile–water–soil interaction. When water depth increases, in addition to the “added mass” and “hydrodynamic damping”, the “radial constraint enhancement effect” becomes the core difference. The radial extrusion of the pile by water forms a “confining pressure-like constraint”, which significantly improves the radial equivalent stiffness of the pile. At this time, the “magnitude of stiffness increase” exceeds the “magnitude of inertia suppression by added mass”. This occurs according to the law of the vibration system whereby the resonance amplitude is positively correlated with the stiffness–mass ratio. The peak displacement at the pile top increases with the increase in water depth. However, the added mass still reduces the natural frequency of the system; thus, the peak frequency also shifts to the low-frequency band.

For d ≥ 20, the water layer provides sufficient hydrodynamic added mass and radial confining pressure, leading to a stable “water–pile–soil coupling mechanism” that dominates the response for ≥ 1. For d = 10, shallow water fails to establish the stable coupling mechanism observed in deeper water, leading to a response dominated by soil axial stiffness decay (not radial constraint).

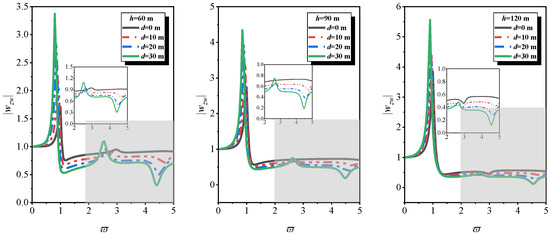

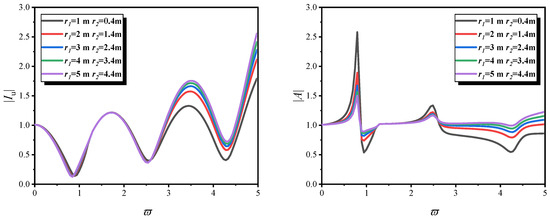

5.3. Distinctive Effects of the Tubular Pile Wall Thickness

Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate the variations in and with respect to ϖ for different tubular pile wall thicknesses, considering the one-dimensional model, the three-dimensional model, and a constant outer radius. As can be seen from Figure 8 and Figure 9, under vertical seismic excitation and with the fixed outer diameter of the tubular pile, the absolute values of the response parameters and of the one-dimensional tubular pile exhibit multi-peak oscillation and fluctuating changes in the overall amplitude as the inner diameter increases. For the three-dimensional tubular pile, as the inner diameter increases, the peak values in the low-frequency range rise significantly while the attenuation in the high-frequency range becomes more pronounced. There are distinct differences in the regulatory laws of the tubular pile’s inner diameter regardin the dynamic responses of the two models.

Figure 8.

The variation trend of parameters and with the inner diameter of the tubular pile under vertical seismic excitation and constant outer diameter of the tubular pile (one-dimensional representation of tubular pile).

Figure 9.

The variation trend of parameters and with the inner diameter of the tubular pile under vertical seismic excitation and constant outer diameter of the tubular pile (three-dimensional representation of tubular pile).

When the inner diameter of the one-dimensional tubular pile model increases, three factors change simultaneously: the pile’s axial equivalent stiffness (which decreases as the pile wall thins), mass (which reduces as concrete consumption decreases), and pile–soil axial contact characteristics. In contrast, for the three-dimensional tubular pile model, a larger inner diameter leads to a thinner pile wall, lower radial stiffness, and more prominent radial deformation of the tubular pile. This enhanced radial deformation, in turn, strengthens the pile–water radial coupling effect and the pile–soil radial scattering effect. The phenomenon of “increasing pile diameter enhancing system damping” (focused on the three-dimensional tubular pile model) is indeed driven by the synergistic effects of larger hydrodynamic added mass and increased energy dissipation in soil, with geometric stiffness effects playing a negligible role.

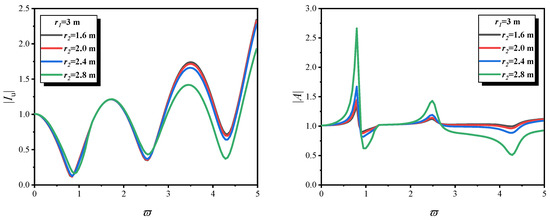

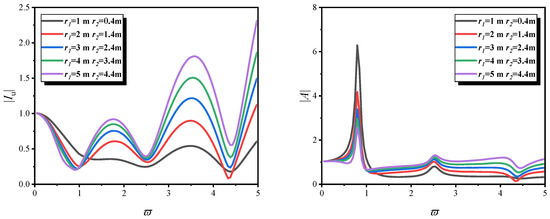

5.4. Distinctive Effects of the Tubular Pile Radius

Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrate the variations in and with respect to ϖ for different tubular pile radii, considering the one-dimensional model, the three-dimensional model, and a constant outer radius. Under vertical seismic excitation and with a fixed tubular pile thickness, the one-dimensional and three-dimensional tubular pile models exhibit significant differences in the variation trends of different dynamic response indicators with radius.

Figure 10.

and versus ϖ for different tubular pile radius r1 and r2. (Constant tubular pile thickness under one-dimensional model).

Figure 11.

and versus ϖ for different tubular pile radius r1 and r2. Constant tubular pile thickness under three-dimensional model).

In the one-dimensional tubular pile model, the left subfigure’s response shows an attenuation trend in the low-frequency range as the radius increases, due to “axial stiffness–mass imbalance”; in the high-frequency range, it exhibits complex oscillations caused by simplified modal coupling. In contrast, the three-dimensional tubular pile model employs a true axial–radial multi-degree-of-freedom modal coupling, as opposed to the crude simplification inherent in the one-dimensional tubular pile model. This enables high-frequency oscillations to be systematically governed by radial modes, yielding curve oscillations that exhibit greater physical consistency.

Additionally, in the three-dimensional tubular pile model, the right subfigure’s response rises significantly in the low-frequency range as the radius increases, due to “multi-field interaction dominated by radial coupling”; in the high-frequency range, it gradually flattens out due to radial energy dissipation (including water radiation damping and soil shear wave attenuation). However, the one-dimensional tubular pile model cannot capture such laws because it ignores radial coupling.

6. Conclusions

This research endeavors to fill the research gap concerning the investigation of the vertical seismic dynamic behavior of offshore end-bearing tubular piles—specifically, addressing the lack of integrated free-field/scattered-field water–soil interaction analysis and the lack of distinction between one- and three-dimensional tubular pile models—by developing an analytical framework for multi-physical field (outer soil–tubular pile–inner soil–water) coupling. Validated against the existing literature, the framework supports parametric analyses, with the key conclusions as follows.

- Model dimensionality dominates responses: one-dimensional tubular pile model (axial vibration only) underestimates radial water–pile–soil coupling, leading to 20–30% overpredicted high-frequency displacements; three-dimensional tubular pile model (axial–radial coupling) captures radial constraint and scattering, providing more accurate results.

- Water depth exerts model-dependent effects: for one-dimensional tubular pile model, deeper water (5–30 m) suppresses displacement peaks via added mass/damping; for three-dimensional tubular pile model, d > 20 m enhances radial water confinement, increasing peaks (stiffness gain > inertia effect).

- Geometric parameters regulate responses nonlinearly: larger pile diameter strengthens water–soil energy dissipation (damping increases by 15–25%); thinner walls (hollow ratio < 0.6) reduce radial stiffness, amplifying low-frequency responses.

This framework directly supports offshore tubular pile seismic design: It guides model selection (one-dimensional tubular pile model for shallow water <5 m, three-dimensional tubular pile model for deep water >20 m) to avoid over-design or under-design. Both models in this article are based on theoretical derivation, and the mathematical structure of the analytical formulas is clear. Sensitivity analysis can be used to clarify the influence of key variables and optimize the models or modify assumptions accordingly.

To balance analytical tractability, this study adopts a simplified soil modeling approach, treating the soil as a homogeneous, single-phase medium while omitting the influences of pore water–solid coupling and the nonlinear mechanical properties of layered soils. This introduces certain limitations that warrant further refinement in subsequent research. Notably, the parameter set utilized in this work is not customized for a particular marine environment. As such, parameters including tidal height, soil density and type, and pile foundation material and type only serve as inputs for mathematical analysis. More in-depth investigations into these factors will be carried out in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.; Methodology, Y.H.; Software, Y.H. and J.Z.; Investigation, X.L.; Resources, X.L.; Data curation, J.Z. and P.W.; Writing—original draft, Y.H.; Supervision, Y.L. and P.W.; Project administration, Y.L. and P.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.H. and P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, under Grant Nos. 52508561 and 52078010, as well as the Beijing Natural Science Foundation under Grant No. JQ24050.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix B

According to Helmholtz decomposition principle, the vector displacement of soil can be expressed as the following scalar displacement and

Adopt the separation of variables method, Equations (A34) and (A35) lead to the general solutions that follow

with

where , , , , , , , and are undetermined coefficients.

In addition, can be obtained from boundary condition (16) when adopting the one-dimensional model of the tubular pile (neglect the radial displacement of the soil):

also can be obtained from boundary condition (17) when adopting the three-dimensional model of the tubular pile:

Appendix C

Upon substituting Equations (55), (57), (67), (71), and (74) into Equations (21) and (28), the following is obtained

In light of the relationship between Equations (67) and (71), followed by substituting them into Equations (A42) and (A43), can be obtained as

where , and can be found in Appendix A.

Substituting Equations (A44) and (A45) into Equations (67), (71) and (74), obtains

Appendix D

References

- Upasana, N.; Suanta, H. Seismic fragility and vulnerability assessment of multi-megawatt jacket-supported offshore wind turbines. Mar. Struct. 2015, 104, 103882. [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Kaynia, A.M.; Zhang, J.S. Lateral free-field responses and motion interaction of monopiles to obliquely incident seismic waves in offshore engineering. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 132, 103956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.L.; Wang, P.G.; Zhao, M.; Xi, R.Q.; Du, X.L. A numerical method for evaluating the earthquake response of a 5 MW OC4 semi-submersible FOWT under multidirectional excitations. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 196, 109467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.L.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, J.Q.; Gao, Z.D.; Du, X.L. A non-convolutional complex-frequency-shifted SBPML for wave problems in 3D unbounded waveguide modellings. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 148, 116277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Shen, Y.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Du, X. The dynamic response and parameter influence analysis of Submerged Floating Tunnel under seismic action. Ocean Eng. 2025, 337, 121877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Adhikari, S. Experimental validation of soil-structure interaction of offshore wind turbines. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 31, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, W.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Newson, T.; El Naggar, M.H. Analytical solution for kinematic response of offshore piles under vertically propagating S-waves. Ocean Eng. 2022, 262, 112018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arany, L.; Bhattacharya, S.; Adhikari, S.; Hogan, S.J.; Macdonald, J.H.G. An analytical model to predict the natural frequency of offshore wind turbines on three-spring flexible foundations using two different beam models. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 74, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhoury, P.; Ait-Ahmed, M.; Soubra, A.H.; Rey, V. Vibration reduction of monopile-supported offshore wind turbines based on finite element structural analysis and active control. Ocean Eng. 2022, 263, 112234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.D.; Zhang, J.S.; Wu, W.B.; Shi, X.; Meng, F. Soil-pile interaction in the pile vertical vibration based on fictitious soil-pile model. J. Appl. Math. 2014, 2014, 905194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezi, F.; Carbonari, S.; Leoni, G. A model for the 3d kinematic interaction analysis of pile groups in layered soils. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2009, 38, 1281–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Ma, R.; Shi, Y.D.; Li, Z.X. Underwater shaking table tests on bridge pier under combined earthquake and wave-current action. Mar. Struct. 2018, 58, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, H.G.; Davis, E.H. Pile Foundation Analysis and Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Huang, Y.M.; Wang, P.G. An analytical solution for the dynamic response of an end-bearing pile subjected to vertical P-waves considering water-pile-soil interactions. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 153, 107126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morison, J.R.; O’Brien, M.P.; Johnson, J.W.; Schaaf, S.A. The force exerted by surface waves on piles. J. Pet. Technol. 1950, 2, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, K.H.; Xiao, S.; Wu, W.B. Dynamic response of a pile considering the interaction of pile variable cross section with the surrounding layered soil. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods GeoMech. 2017, 41, 1196–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.M.; Lin, Z.N.; Yin, J.; Zeng, L.; Zhao, Z.J.; Chen, N.C. Study on aerodynamic performance of floating offshore wind turbine with fusion winglets under yaw motion. Ships Offshore Struct. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.G.; Zhao, M.; Li, H.F.; Du, X.L. An accurate and efficient time-domain model for simulating water-cylinder dynamic interaction during earthquakes. Engin. Struct. 2018, 166, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Wu, W.; Liu, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, P. New method to calculate the kinematic response of offshore pipe piles under seismic S-waves. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 165, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Lin, H.; Cao, G.; Luan, L. Horizontal dynamic response of offshore large-diameter pipe piles. Ocean Eng. 2023, 272, 113797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, C.; Luo, C.; Yin, B.; Sun, H. Damping cable-based vibration control of pile-supported offshore wind turbine tower. Ocean Eng. 2025, 338, 121921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Yang, M.; Yang, H.; Li, S. Lateral dynamic response of partially embedded piles in the sea considering wave loads and wave-induced seabed dynamic response load distribution effects. Ocean Eng. 2025, 318, 120041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, X.; Xie, Y.; Cao, S.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y. Study on complex failure modes of super-long piles in deep-water and soft-clay seabed under multiple combined loads. Ocean Eng. 2025, 336, 121806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.B.; Wu, W.B.; Liu, H.; El Naggar, M.H.; Wen, M.; Wang, K. Influence of defects on the lateral dynamic characteristics of offshore piles considering hydrodynamic pressure. Ocean Eng. 2022, 260, 111894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorzaei, J.; Naghshineh, A.; Abdul, K. Nonlinear interactive analysis of cooling tower-foundation-soil interaction under unsymmetrical wind load. Thin-Walled Struct. 2006, 44, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, A.R.; Guo, Y.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T. Development of a 5 MW reference gearbox for offshore wind turbines. Wind. Energy 2016, 19, 1089–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.P.; Song, L.H.; Mei, G.X.; Zhao, Y.L. On predicting displacement-dependent earth pressure for laterally loaded piles. Soils Found. 2018, 58, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M. Dynamic impedance of piles. Can. Geotech. J. 1974, 10, 486–497. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.J.; Luan, L.B.; Qin, H.Y.; Zhou, H. Horizontal dynamic response of a combined loaded large-diameter pipe pile simulated by the Timoshenko beam theory. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2020, 20, 2071003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Beredugo, Y. Vertical vibration of embedded footings. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1972, 98, 1291–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.J.; Ding, X.M.; Luan, L.B. Analysis of lateral dynamic response of pipe pile in viscoelastic soil layer. Rock Soil Mech. 2017, 37, 26–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Comodromos, E.M.; Papadopoulou, M.C.; Rentzeperis, I.K. Pile foundation analysis and design using experimental data and 3-D numerical analysis. Comput. Geotech. 2009, 36, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C. Semi-active control of monopile offshore wind turbines under multi-hazards. Mech. Syst. Sig. Process. 2018, 99, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.P.; Mitchell, L. Diffraction of ocean waves around a hollow cylindrical shell structure. Wave Motion 2009, 46, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovino, M.; Di Laora, R.; Rovithis, E.; De Sanctis, L. The beneficial role of piles on the seismic loading of structures. Earthq. Spectra 2019, 35, 1141–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacul, S.; Rovithis, E.; Di Laora, R. Kinematic soil-pile interaction under earthquake-induced nonlinear soil and pile behavior: An equivalent-linear approach. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2022, 148, 04022055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.H.; El Naggar, M.H.; Zhang, N.; Gao, Y.F. Kinematic response of an end-bearing pile subjected to vertical P-wave considering the three-dimensional wave scattering. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 120, 103368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.M.; Wang, P.G.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, C.; Du, X.L. Dynamic responses of an end-bearing pile subjected to horizontal earthquakes considering water-pile-soil interactions. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 238, 109726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Huang, Y.M.; Wang, P.G.; Cheng, X.L. Du, X.L. Analytical solution of vertical vibration of a floating pile considering different types of soil viscoelastic half-space. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 165, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Jeong, H.K.; Dou, H. Study on the structural strength assessment of mega offshore wind turbine tower. Energies 2025, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.Y.; Meng, K.; Xu, C.; Wang, B.; Xin, Y. Vertical vibration of a floating pile considering the incomplete bonding effect of the pile-soil interface. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 150, 104894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, X.; Gu, X.L.; Zhao, Q.; Yuan, G.K.; Liu, J.C. Axial compression tests of grouted connections in jacket and monopole offshore wind turbine structures. Eng. Struct. 2019, 196, 109330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, J.; Butterfield, S.; Musial, W.; Scott, G. Definition of a 5-MW Reference Wind Turbine for Offshore System Development; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2009; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Wang, L.; Pak, R.Y.S.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, J. Vertical elastic dynamic impedance of a large diameter and thin-walled cylindrical shell type foundation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 95, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, C.Y.; Chopra, A.K. Dynamics of towers surrounded by water. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1974, 3, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, W.L. An improved method of hydrodynamic pressure calculation for circular hollow piers in deep water under earthquake. Ocean Eng. 2013, 72, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Kouretzis, G.; Luan, L.; Ding, X. Motion response of pipe piles subjected to vertically propagating seismic P-waves. Acta Geotech. 2021, 16, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.G.; Wang, B.X.; Dong, Z.H.; Cheng, X.L.; Du, X.L. An analytical solution for vertical seismic response of an end-bearing pile in saturated soil considering pile-soil and free and scattered field water-soil interaction. Mar. Struct. 2024, 98, 103677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).