Abstract

This study presents a systematic analysis of the stability and roll characteristics of an Oscillating Water Column (OWC) wave energy buoy. By integrating theoretical derivation and AQWA simulation, the research identifies thirteen possible heeling states of OWC buoy, focusing on five representative states applicable to the current design. A novel segmented-integration model is proposed to compute the centre of buoyancy and righting moment for the hollow-annular OWC buoy, accurately capturing the evolution of static and dynamic stability across heel angles from 0° to 90°. Results show that the buoy has an initial metacentric height of 0.33 m, a maximum righting arm of 0.713 m, a limiting static heel angle of 77°, and a minimum capsizing moment of 22,887 N·m—all significantly exceeding regulatory requirements. The roll natural period ranges from 5.8 to 7.7 s, with a tuning factor above 1.3, effectively avoiding resonance with typical wave periods in the target sea area. The buoy demonstrates excellent dynamic stability and capsize resistance. This study fills a gap in OWC buoy stability analysis and provides a practical guidance for the safe design of wave energy devices.

1. Introduction

The oscillating water column (OWC) wave energy converter has emerged as a focal point in ocean energy development, broadly categorized into floating and shore-mounted systems [1,2,3,4]. Among floating OWC devices, the most common configurations are the backward-bent duct buoy (BBDB) [5,6,7] and the central-pipe type [8,9]. Central-pipe OWC systems are typically employed in wave-energy buoys and can be further divided into heave-plate [10,11] and conical-pipe variants [12]. While extensive research has been conducted on the hydrodynamic and energy-conversion characteristics of OWC devices [13,14,15], studies specifically addressing the stability analysis of central-pipe OWC wave-energy buoys remain scarce. Most available literature concentrates on the stability of conventional ships or generic floating structures.

The stability of small-diameter cylindrical structures, which share key geometric features with central-pipe OWC buoys, has been extensively studied in related floating systems, providing valuable theoretical foundations. For instance, in the historical development of floating-body stability theory, early scholars such as Stevin, Huygens, Bernoulli, and Euler employed geometric and mechanical methods to investigate whether a floating body could return to equilibrium after disturbance [16]. Their work gradually established the concepts of “restoring moment” and “stability under infinitesimal perturbations,” laying the theoretical and methodological groundwork for modern floating-structure stability analysis. Spyrou [17] systematically reviewed the stability theory and methods for cylindrical floating bodies in calm water, noting that due to their axisymmetric nature, such structures exhibit neutral stability in roll. He clarified the equilibrium conditions of cylinders under various floating states and revealed the nonlinear mechanisms governing transitions between these states. Specifically, he pointed out that when a cylinder is partially submerged, its stability can be determined by the relationship between the second moment of the waterplane area and the displaced volume. Zheng [18] et al. proposed an integrated “static–dynamic stability” analytical model for ocean monitoring buoys. For small heel angles (<10°), they derived the initial metacentric height and natural roll period; for larger angles, they applied segmented integration to compute the volume and static moment of the submerged and emerged wedges. This approach yielded the static stability arm Lφ and dynamic stability arm Ldφ at any heel angle φ, from which the limiting static heel angle φmax, limiting dynamic heel angle φdmax, and minimum capsizing moment were determined. By coupling frequency-domain RAOs with irregular wave spectra, they further showed that when the height-to-diameter ratio of the main buoy body falls between 0.375 and 0.5, the buoy can simultaneously achieve low resonance peaks and adequate restoring forces. Liang Guanhui [19] et al., applying ship statics and wave theory, conducted initial and large-angle stability calculations for a small disc-type data buoy intended for deep-sea operations. Using the waterplane moment-of-inertia method and the variable-displacement approach, they determined the initial metacentric height, maximum righting arm, limiting static heel angle, angle of vanishing stability, and minimum capsizing arm. All parameters satisfied the relevant code requirements, demonstrating the validity of theoretical calculations at the buoy conceptual-design stage. The studies referenced in [16,17,18,19] focus on theoretical analysis and stability calculations, providing a solid theoretical foundation for the stability analysis of OWC buoys.

References [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] focus on stability thresholds and simulation or experimental studies of special-structure floaters such as Spar platforms and heave plates, offering useful guidance for the dimensional design and weight allocation of OWC buoys. Segura [20] shows that the conventional GM criterion is ambiguous for ship-shaped floaters and proposes an energy–momentum-space metric instead. Tests give capsizing thresholds: stable at density ratios 0.5–0.9, roll-unstable at 0.1–0.4, and transitional heel at 0.4–0.5. Habib [21] et al. performed a nonlinear dynamic analysis of the parametric roll problem for a classical Spar platform under coupled surge–pitch excitation. They found that when the incident wave frequency is close to the natural surge frequency, even a wave height as low as 1 m (A/GM ≈ 0.1) can cause the system to jump to large-amplitude roll motions depending on the initial disturbance. Umar & Datta [22] investigated dynamic instabilities of a slack-moored, hollow cylindrical buoy under regular waves. At specific sea states (H = 12 m, T = 10 s), the nonlinear restoring characteristics of the six polyester ropes induce sub-harmonic oscillations, symmetry-breaking bifurcations and even chaotic responses. Aziminia [23] et al. established a parametric-rolling assessment framework for Spar platforms using Floquet theory. With time-varying GM as excitation, Mathieu-equation eigenvalues map instability tongues; sub-harmonic resonance is triggered when the wave frequency approaches half the pitch natural frequency and the heave amplitude is sufficiently large. Adding damping plates/fins raises the transition curve and shrinks the unstable region, providing rapid roll-safety thresholds for preliminary Spar design. Liu Y [24] et al. developed a 6-DOF nonlinear coupled model and employed Melnikov’s method to derive capsizing thresholds of floating platforms (including observation buoys) under combined wind and waves. The relationship between GM variation and stability loss is discussed, offering a reference for analysing roll instability in a wind–wave environment. Su [25] et al. proposed a dual-path stability test (“inclination + suspension”) for the deep-sea BAILONG buoy. By measuring 3-D centre-of-gravity coordinates, initial metacentric height and roll natural period, they verified the stability reliability of small, quasi-revolution-symmetric buoys within acceptable construction tolerances. Liu H [26] et al. performed an AQWA frequency-domain parametric scan on 48 cylindrical internal-wave buoys. Their results indicate that for a column height ranging from 1.2 to 1.3 m and a diameter between 0.6 and 0.7 m, the roll RAO remains below 10 degrees. In contrast, a smaller diameter of 0.4 m renders the buoy prone to resonant capsizing exceeding 90 degrees under high-frequency waves, thereby establishing critical dimensional thresholds for OWC-type cylindrical floats. Chen [27] et al. established an analytical static–dynamic balance model for a 2.3 m diameter frustum-cylinder compound buoy. Theory and sea trials confirmed self-righting up to 20° heel, validating the design principle “lower CG & raise CB” for improving the stability of small-scale buoys. Chen X.Y [28] presented a wave-piercing, multi-column HDPE buoy with reduced wave-facing area and low CG (ZG = 2.16 m), achieving maximum roll less than 4° and heave response only one-third that of conventional steel buoys, demonstrating that material-structure integration can significantly enhance dynamic stability in extreme sea states.

Owing to its hollow annular geometry and appendages such as a heave plate and a ballast block, an OWC buoy differs markedly from conventional floating bodies in displaced volume, wetted area and water-plane shape. Determining its centre of buoyancy and the iso-volume waterlines is therefore far more laborious than for ordinary hulls, so that traditional stability methods cannot be applied directly. Although numerous studies exist on the stability of floating bodies, detailed investigations devoted specifically to OWC buoys—covering both stability computation and roll-period estimation—are scarce. A systematic exposition of the calculation procedures for the stability and roll period of OWC buoys is thus urgently needed and will be initiated in this paper to provide an essential reference for future design and development.

In the present work the classical stability theory is extended to suit OWC geometries, leading to a new stability model that is implemented in a MATLAB code (version R2024a) (the theoretical method). Section 2 introduces the principal parameters and basic stability concepts. Section 3 computes the hydrostatic data for the upright condition by both the theoretical method and AQWA simulation, with the results being cross-verified. Section 4 evaluates initial, large-angle and dynamic stability with the two approaches and checks the results against the relevant rules. Section 5 employs the stability results to calculate and analyse the roll periods of the buoy.

2. Basic Parameters and Stability Overview

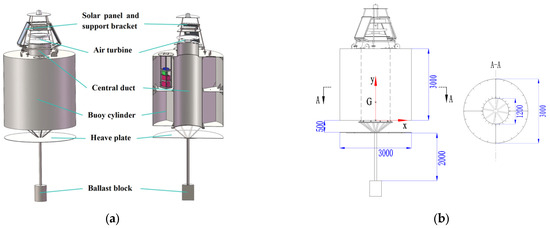

The OWC buoy developed in this study is illustrated in Figure 1. It consists of an upper structure, a buoyant cylinder, a heave plate, and a ballast block. The upper structure accommodates solar panels with their supports, a monitoring system, a communication box, and the air turbine together with its generator. The buoyant cylinder comprises an annular shell and an inner central duct that serves as the OWC airway and air chamber—the principal site of energy conversion. Below the cylinder, a heave plate (to increase motion damping) and a ballast block (to lower the centre of gravity) are installed. The working principle is that relative motion between waves and the buoy induces oscillation of the water column inside the central duct, forcing air to flow back and forth through the turbine and thus driving the turbine and generator. Principal dimensions are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Overall structure of the OWC wave-energy buoy. (a) 3D view of the buoy; (b) 2D drawing of the buoy.

Table 1.

Principal Parameters of the Buoy.

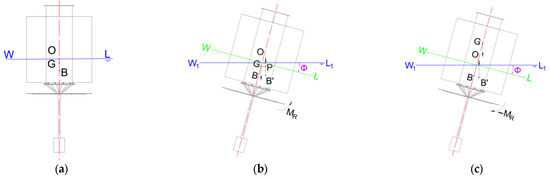

Stability is the ability of a floating body to return to its original equilibrium position after an external force has been removed. As sketched in Figure 2, a buoy may exhibit three states: upright equilibrium, stable heel, and unstable heel. Stability analysis evaluates the gravitational force, centre of gravity, buoyant force, centre of buoyancy, and righting moment to determine whether the buoy can regain upright flotation after heeling. The assessment covers initial stability, large-angle stability, and dynamic stability. Because the OWC buoy is an axisymmetric annular cylinder, heeling in any horizontal direction is mechanically identical; consequently, the present analysis focuses on transverse (roll) stability.

Figure 2.

Floating states of the buoy. (a) Upright floating; (b) stable heel; (c) unstable heel.

3. Calculation of the Buoy in Upright Floating Condition

The first step in the stability analysis of an OWC wave-energy buoy is to determine the center of buoyancy (CoB) and the displacement volume in the upright condition. Two approaches are adopted: (i) a theoretical procedure based on hydrostatic theory [29], and (ii) hydrodynamic simulation with the commercial software AQWA. The theoretical method evaluates the displaced volume, the equivalent waterplane, and the CoB, from which the righting moment and dynamic stability arms are subsequently derived. In the numerical approach, a three-dimensional panel model of the buoy is created in AQWA; the software is used to obtain the displaced volume, the CoB, and the initial stability parameters. Repeated simulations over a range of heel angles yield the curves of righting moment and dynamic stability arm. The two independent sets of results are compared to cross-validate accuracy.

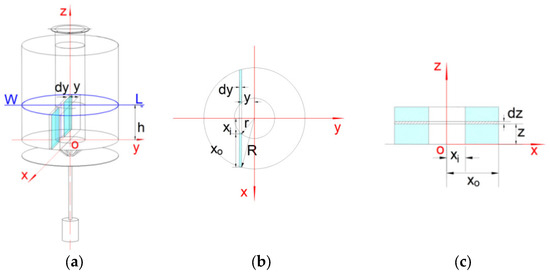

3.1. Theoretical Method

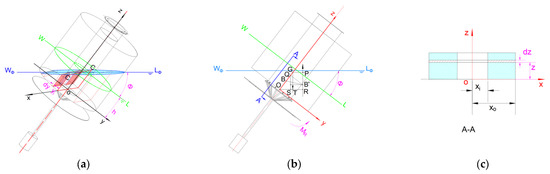

To facilitate subsequent stability analyses at arbitrary heel angles, a transverse-slice integration technique is employed. As shown in Figure 3, the buoy has a draught (h), an outer profile radius (R), and an inner cavity radius (r). The submerged volume below the waterline WL is subdivided into infinitesimal slices of thickness dy taken perpendicular to the y-axis. For each slice the sectional area (As), its static moment (Mox) about the ox axis, and the vertical coordinate (za) of the sectional centroid are computed. Integration over all slices yields the total displaced volume (V) (Equation (2)) and the hydrostatic moments (Mxoy) (Equation (5)) and (Mxoz) (Equation (6)) with respect to the reference planes, from which the coordinates (xB, yB, zB) of the centre of buoyancy B are obtained.

Figure 3.

Transverse-slice integration method. (a) Buoy 3D schematic; (b) top view; (c) cross-section.

Depending on the submerged cross-sectional composition, the buoy can be divided into three segments along the y-axis: the left section without the central tube, the middle section containing the central tube, and the right section without the central tube. The cross-sectional area As can thus be expressed as:

In the equation, xO represents the semi-width of the buoy’s outer profile section, expressed as ; xI denotes the semi-width of the buoy’s inner cavity (central tube) section, given by . When , .

Therefore, the displacement volume (V) at draft (h) shall be calculated by integrating across three segments as follows:

The static moment of the cross-sectional area As about the ox-axis is:

The vertical coordinate za of the centroid of the cross-sectional area As is:

Similarly, the static moment of the displaced volume V about the base plane xoy should be calculated by integrating across three segments:

The static moment of the displaced volume V about the midship section xoz should be calculated by integrating across three segments:

The vertical coordinate of the centre of buoyancy B is and its transverse coordinate is . Owing to the buoy’s rotational symmetry, all calculations in this paper assume that heel occurs solely along the y-axis; no inclination is considered in the x-direction, so the longitudinal coordinate of the centre of buoyancy is xB = 0.

In addition to the main buoy structure, the influence of protruding components such as the heave plate and ballast block on the buoyancy center position and static moment distribution must be considered. Therefore, calculation methods similar to those used for the main structure should be applied to determine the buoyancy center coordinates and static moment parameters of the heave plate, ballast block, ballast connecting rod, heave plate connecting rod, central tube extension, and flange components. Subsequently, the buoyancy parameters of the main buoy structure and all protruding components are integrated through composite superposition calculations. This process is essentially equivalent to performing segmented integration along the vertical direction of the complete buoy, thereby accurately determining the overall buoyancy center position and static moment distribution of the buoy including protruding components.

Based on the aforementioned theoretical methodology, we developed a MATLAB program to compute the buoy’s parameters. By inputting the fundamental data from Table 1, the calculated results presented in Table 2 were obtained. The data in Table 2 demonstrate that the total displacement volume of the buoy is V = 7.9644 m3, with longitudinal static moment Myoz = 0 m4, transverse static moment Mxoz = 0 m4, and vertical static moment Mxoy = 4.6117 m4. The coordinates of the overall center of buoyancy are (0, 0, 0.5790), denoted as B(0, 0, 0.5790). The vertical distance between the center of gravity (G) and the center of buoyancy (B) is calculated as .

Table 2.

Calculation Results of Buoy Component Parameters.

The aforementioned theoretical model is established based on the following assumptions:

- (1)

- Neglect of Viscous Effects: The model is based on potential flow theory and inviscid hydrostatics, neglecting viscous damping and flow separation. This is a standard and justified assumption for calculating static stability parameters, where inertial and restoring forces dominate.

- (2)

- Treatment of Protruding Parts (Heave Plate and Ballast): The heave plate and ballast block are fully incorporated in calculations of the center of gravity, center of buoyancy, and displaced volume under upright and small-angle heeling conditions. However, simplifications are introduced for heel angles greater than 55°. Specifically, the effects of the emergent portions of these protruding components on the center of buoyancy and displaced volume are neglected during large-angle inclination. The resulting discrepancies, along with their underlying causes, are discussed in detail in Section 4.2.3.

- (3)

- Rigid Body Hypothesis: The buoy is treated as a rigid structure without considering elastic deformations.

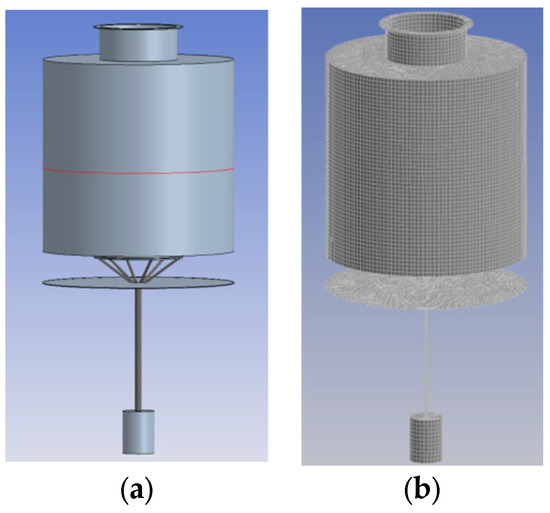

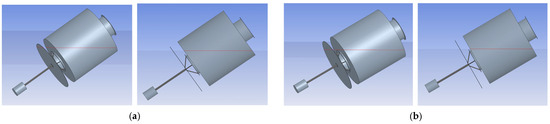

3.2. AQWA Simulation

Based on the dimensional parameters in Table 1, a three-dimensional model of the OWC buoy was created in ANSYS AQWA (2023R1) using DesignModeler, as shown in Figure 4a. The following configurations were then applied in AQWA:

Figure 4.

AQWA simulation model. (a) Buoy 3-D model; (b) buoy mesh model.

- (1)

- Environmental Parameters: Water depth of 13 m, fluid density of 1025 kg/m3, and a numerical basin of 150 m × 150 m.

- (2)

- Buoy Parameters: Mass moments of inertia set to Ixx = 32,273 kg·m2, Iyy = 32,118 kg·m2, and Izz = 9241 kg·m2.

- (3)

- Mesh Settings: A global element size of 0.06 m was used, resulting in 22,128 panels. Figure 4b displays the corresponding mesh model with detailed element distribution.Key mesh statistics included:

- °

- Maximum Allowed Frequency: 1.82403 Hz

- °

- Create Automatic Waterline Nodes: Enabled

- °

- Connection Tolerance: Default

- °

- External Surface Diffracting Nodes: 12,420

- °

- External Surface Non-Diffracting Nodes: 9709

- °

- Line Body Nodes: 219

- °

- Line Body Elements: 106

- (4)

- Frequency-Domain Analysis Settings:

- °

- Ignore Modeling Rule Violations: Enabled

- °

- Calculate Full QTF Matrix: Enabled

- °

- Maximum Period: 20 s

- °

- Minimum Period: Automatically determined by the solver

- °

- Other settings retained as default.

- (5)

- Time-Domain Settings for Roll Period Analysis:

- °

- Analysis Type: Low-frequency drift forces only

- °

- Time Step: 0.1 s

- °

- Other settings retained as default.

Grid Convergence Study: A grid convergence study was conducted following the software’s panel limit specifications. Three mesh configurations with 12,518 (coarse), 22,128 (medium), and 39,845 (fine) panels were systematically compared in Table 3. The maximum observed variation in critical upright hydrostatic parameters—including displaced volume (0.013%), vertical center of buoyancy (0.17%), and metacentric height (0.091%)—between the medium and fine grids confirms that the 22,128-panel mesh achieves sufficient numerical accuracy for the global stability analysis presented in this study.

Table 3.

Comparison of Results Using Different Grid Densities.

3.3. Comparison of Results

The displaced volumes and centres of buoyancy obtained by the two approaches are compared in Table 4. The design mass of the buoy is 8129 kg, which corresponds to a displaced volume of 7.931 m3 in seawater (ρ = 1025 kg·m−3). This value coincides exactly with the AQWA result. The theoretical calculation result is slightly higher than the actual value, with a relative error of 0.42%, while the discrepancy in the vertical coordinate of the CoB is only 0.017%. The excellent agreement confirms that both methods are accurate and mutually consistent for the upright condition.

Table 4.

Comparison of Results Between the Two Methods.

4. Stability Analysis of the Buoy

4.1. Initial Stability

As shown in Figure 2b, when the buoy heels through a small angle (Φ), the centre of gravity G remains fixed while the centre of buoyancy moves from its upright position B to B′. The intersection of the buoyancy-force line with the buoy’s centreline is M, termed the initial metacentre (or transverse metacentre), and is the initial metacentric radius. From the principle of buoyancy transfer, , where ICC is the second moment of the waterplane area WL about the longitudinal centreline C-C, expressed as:

The righting moment is

with the righting arm and the initial metacentric height. For a given displacement, a larger produces a larger righting moment and thus greater

resistance to heeling.

According to the relevant provisions of the Statutory Survey Rules for Ships and Marine Installations [30], the initial metacentric height must be greater than 0.15 m.

- (1)

- Theory: Icc = 3.8743 m4, , .

- (2)

- AQWA: Icc = 3.8333 m4, , .

As shown in Table 5, Both methods yield values well above the statutory minimum of 0.15 m. The Numerical

values are slightly higher than the AQWA results, but the discrepancy is within

1%, confirming mutual consistency.

Table 5.

Comparison of Initial-Stability Results.

4.2. Large-Angle Stability

4.2.1. Large-Angle Heel States of the OWC Buoy

Owing to the hollow central duct, an OWC central-pipe buoy exhibits far more complex behaviour at large heel angles than an ordinary cylindrical buoy. Thirteen distinct floating regimes can be identified, as sketched in Figure 5, where WL denotes the upright waterline and W1L1 the heeled waterline at angle Φ. Regimes A1–A5 occur for medium draught and large freeboard and are the most relevant to the present design; B1–B5 appear only for large draught and small freeboard; C1–C3 arise for small draught and large freeboard. The buoy analysed herein passes through regimes A1–A5 while heeling. Because the submerged sectional area and the elementary volume of each slice change from regime to regime, the hydrostatic calculations must be carried out separately for each case.

Figure 5.

Thirteen typical operating states of the OWC buoy under large-angle heel. (A1) Bottom face remains submerged, top face stays dry; (A2) bottom face emerges but bottom-centre tube still underwater, top face dry; (A3) bottom face emerges but bottom-centre tube still underwater, top face wets; (A4) bottom-centre tube partly out of water, top face wetted; (A5) bottom-centre tube partly out of water, seawater enters top-centre tube; (B1) bottom face still submerged, top face wetted; (B2) bottom face still submerged, seawater enters top-centre tube; (B3) bottom face still submerged, top-centre tube fully flooded; (B4) bottom face emerges while bottom-centre tube remains submerged, seawater enters top-centre tube; (B5) bottom face emerges while bottom-centre tube remains submerged, top-centre tube fully flooded; (C1) bottom-centre tube partly out of water, top face still dry; (C2) bottom-centre tube fully out of water, top face still dry; (C3) bottom-centre tube fully exposed, top face wetted.

4.2.2. Large-Angle Stability Calculation

At large heel angles the gravitational and buoyancy forces create a righting moment ; the lever is termed the static righting arm. From the geometry of Figure 6b,

Figure 6.

Schematic of the buoy at large heel angles. (a) Isometric view; (b) 2D plan view; (c) transverse-section sketch.

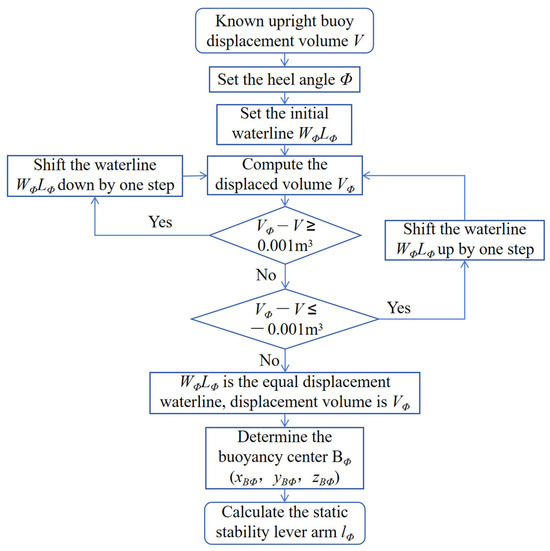

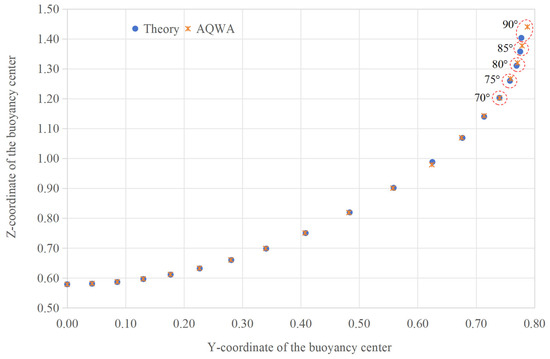

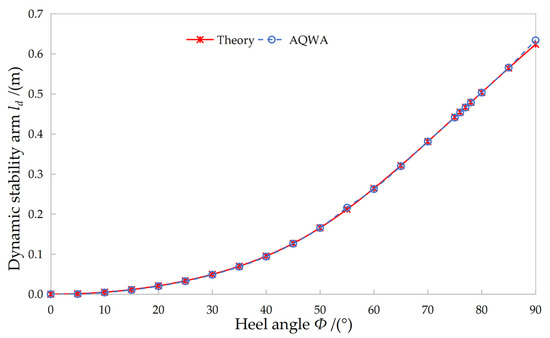

Hence, the critical step is to determine the coordinates of the centre of buoyancy at each heel angle. This is done by first locating the iso-volume waterline for the given angle and then computing the corresponding displaced volume and centroid; the workflow is summarised in Figure 7. In the present study the static-stability curve is evaluated at 5° intervals from 0° to 90° using both the theoretical method and AQWA; the results are plotted in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Calculation Process for Static Stability Lever Arm of OWC Buoy.

Figure 8.

Static stability curve.

- (1)

- General trend

At small angles (0–15°) both curves are essentially straight, consistent with the linear initial-stability assumption. A first upward break appears at about 25–30°, beyond which the righting arms increase more rapidly. A second break occurs at 50–55°, after which the growth rate diminishes. The two curves agree closely up to 70°. Beyond 70° they diverge: the theoretical curve peaks at 76° and then declines slowly, whereas the AQWA curve peaks slightly higher at 77° and then decreases. The divergence is caused by the heave plate and ballast block emerging from the water at large heeling angles, an effect automatically captured by AQWA but omitted in the theoretical code for simplicity. (Refer to Section 4.2.3 for details.) According to reference [30], the righting arm at 30° and beyond shall not be less than 0.20 m; the present buoy satisfies this requirement at all relevant angles.

- (2)

- Maximum righting arm

Theoretical Method: Maximum righting lever lmax = 0.7053 m, Maximum righting moment MRm = 56,245 N·m, Limiting static heel angle Φm = 76°.

AQWA simulation: lmax = 0.7130 m, MRm = 56,861 N·m, Φm = 77°.

Both limiting angles exceed the 25° minimum required by the rules [30].

- (3)

- Righting arm at 90°

When the buoy heels to 90°—its extreme limit beyond which capsize occurs—it is defined in this study as the capsizing threshold.

Theoretical Method: extreme righting lever lex = 0.6702 m, extreme righting moment Mex = 53,445 N·m.

AQWA simulation: lex = 0.7071 m, Mex = 56,384 N·m.

Even at the extreme 90° heel the buoy retains a large righting moment; the angle of vanishing stability is well beyond 90°, indicating negligible capsize risk.

4.2.3. Explanation of Discrepancies at Large Heel Angles

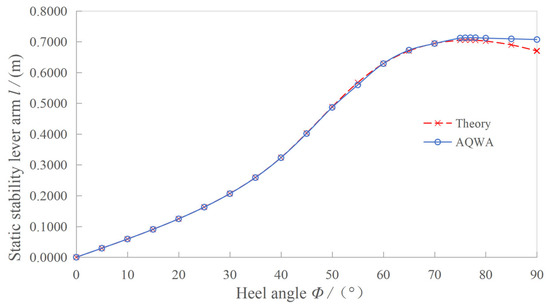

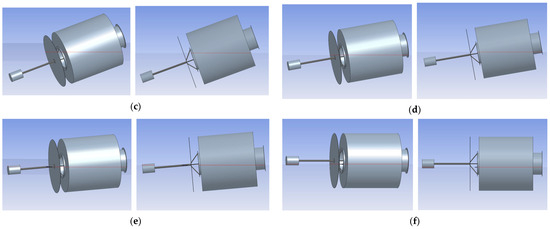

Figure 9 presents screenshots from the AQWA model under large heel angles. As observed, when the buoy’s inclination exceeds 55°, the heave plate begins to emerge from the water surface. The exposed area of the heave plate progressively increases with further inclination. At approximately 85°, the ballast block and its connecting rod also start to emerge. By the extreme inclination of 90°, over half of both the heave plate and ballast block volumes are exposed above the waterline.

Figure 9.

Waterline Positions at Large Heel Angles. (a) 55°; (b) 60°; (c) 70°; (d) 80°; (e) 85°; (f) 90°. The red line indicates the waterline.

The AQWA simulation software can accurately track the emergence process of these protruding components throughout the inclination range. In contrast, the theoretical model faces challenges in capturing and precisely calculating the volume of the emerged portions. The heave plate, being a thin plate, contributes minimally to the overall displacement volume. When its emerged area is limited, the effect is generally negligible. Similarly, the total volume of the ballast block is relatively small compared to the main buoy body, so its emerged portion has limited impact on stability.

Therefore, in our theoretical model for large-angle stability calculations, we have neglected the volume changes resulting from the emergence of protruding components such as the heave plate and ballast block, treating these portions as remaining submerged. This simplification directly leads to the discrepancies in the center of buoyancy position observed in Figure 10. The numerical results show excellent agreement with AQWA simulations for heel angles up to 70°, beyond which deviations gradually develop, reaching maximum difference at 90°. This pattern aligns consistently with the trends observed in both the static stability curve (Figure 8) and dynamic stability curve (Figure 11), thereby providing a coherent explanation for the discrepancies noted in Section 4.2.2 and Section 4.3.2.

Figure 10.

Variation of the Buoy’s Center of Buoyancy Position.

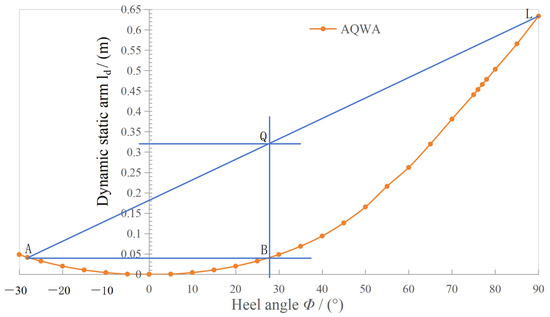

Figure 11.

Dynamic Stability Curve.

4.3. Dynamic Stability

4.3.1. Dynamic Heel Angle

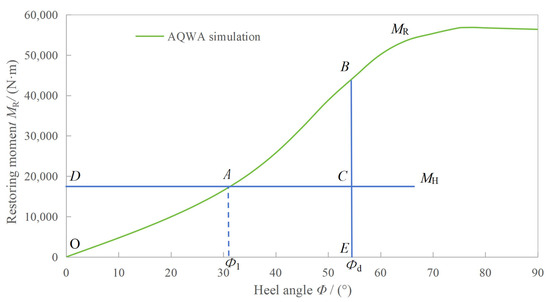

As shown in Figure 12, assume that the buoy is subjected to a slow heeling moment MH and the heel angle at static equilibrium is Φ1. However, under actual sea conditions, the buoy is often suddenly struck by external forces such as gusts of wind and waves, making the analysis of static stability inapplicable.

Figure 12.

Heeling Moment versus Righting Moment.

Suppose the buoy is suddenly subjected to a heeling moment MH while it is in an upright floating position, causing the buoy to rapidly tilt to the angle Φ1. At this point, the external moment MH is balanced by the restoring moment MR, but due to inertia, the buoy will continue to heel until it reaches an angle Φd before stopping. At this angle Φd, the corresponding restoring moment MRB is greater than MH, so the buoy will return to an upright position under the action of MRB. If MH does not disappear, this oscillating state will continue. In reality, due to the presence of water and air resistance, the range of the buoy’s oscillation will gradually decrease until it stabilizes at the angle Φ1.

Therefore, under the action of the sudden external moment MH, the actual maximum heel angle of the buoy is Φd, which is referred to as the dynamic heel angle.

4.3.2. Dynamic Stability Curve

The work done by the external moment is (area ODCE in Figure 12); the work done by the righting moment is (area OABE). Rolling ceases when TH = TR, so dynamic stability is measured by the energy , and the dynamic stability arm is defined as . Figure 11 presents the dynamic-stability curves obtained by

both methods; they are almost identical except at very large angles where AQWA

gives slightly higher values (for the same reason given in Section 4.2.3). The

agreement validates both approaches.

4.3.3. Minimum Capsizing Moment

When a buoy subjected to an external moment MH, typically from waves, reaches its maximum heeling angle Φ0 and begins to swing back, a sudden gust of wind from the opposite direction can exacerbate the situation, leading to a critical state. At this juncture, the restoring moment MR0 and the gust moment MW are superimposed.

The maximum heeling angle Φ0 can be estimated using the following formula based on different sea areas [17,31,32]:

According to the literature [30], by looking up tables and calculations, we obtain: C1 = 0.234, C2 = 0.68, C3 = 0.011, C4 = 1, resulting in Φ0 = 28.11°.

Due to the buoy’s symmetry, the dynamic stability curve is symmetric about the horizontal axis. Thus, the curve can be extended to point A (as depicted in Figure 13), representing the initiation of heeling from the maximum reverse heeling angle Φ0. Given the inflection point near the apex in Figure 13, a tangent cannot be drawn through point A; instead, a secant line AL is utilized at the maximum angle of 90° corresponding to point A. A horizontal section of 1 rad (57.3°) is taken from point A to point B, with a perpendicular line BQ intersecting AL at point Q. The length BQ represents the maximum lever arm (lfmax), also known as the minimum capsizing lever arm (lq). The measured lfmax = lq ≈ 0.28 m corresponds to the minimum capsizing moment Mq = 22887 N·m.

Figure 13.

Minimum Capsizing Lever Arm.

The dynamic stability of the buoy should meet the stability criterion numeral , where lf represents the maximum wind pressure heeling moment. The calculation

formula is as follows:

In the formula, p is the calculated wind pressure, obtained by referring to the table based on the buoy deployment sea area [31]; Af is the windward area of the buoy, which is the side projection area above the waterline of the buoy; Z is the lever arm of the wind force; Δ is the buoy’s displaced volume. After calculation, p = 244 Pa, Af = 7.965 m2, Z = 1.388 m, Δ = 8.129 t, lf = 0.031 m, and the stability criterion K = 9.03 > 1; hence, the designed OWC buoy in this paper meets the regulatory requirements [30].

As shown in Table 6, all indices exceed the regulatory minima, confirming ample stability margins.

Table 6.

Summary of OWC-Buoy Stability Results.

The applicability of the standard criterion K ≥ 1, stipulated in the Statutory Survey Rules [30], to the non-standard geometry of the OWC buoy is supported by both precedent and principle. This same criterion has been successfully employed for the stability assessment of other buoy designs with specialized geometries in peer-reviewed literature [18,19]. Fundamentally, the criterion ensures that the work done by the dynamic righting moment exceeds that of the heeling moment—a universal energy-based safety requirement for any floating body. Furthermore, the exceptionally high value of K = 9.03 calculated for the present design provides a substantial safety margin, rendering any minor uncertainty regarding geometric applicability inconsequential to the overall conclusion of adequate dynamic stability.

4.4. Influence of Mooring System on Buoy Stability

The mooring system significantly affects the buoy’s stability by constraining its six-degree-of-freedom motion. This influence is primarily manifested in two aspects:

4.4.1. Beneficial Effects (Enhanced Righting Moment)

Mooring cables generate restoring forces when the buoy experiences drift or large-angle tilting. The restoring force along the cable direction creates a righting moment on the buoy, thereby enhancing its effective righting moment. This is particularly critical for maintaining the buoy’s attitude stability under environmental loads such as wind and currents. Specifically, when the buoy tilts to large angles, the additional restoring force provided by the mooring system acts as a beneficial supplement to the buoy’s inherent righting arm curve, improving the overall stability reserve of the buoy to a certain extent.

4.4.2. Adverse Effects (Introduction of Capsizing Risks)

Under certain severe sea conditions, the mooring system may also pose hazards to the buoy’s stability. For example, when the buoy undergoes significant motion with waves, taut mooring lines may generate an additional capsizing moment due to substantial dynamic tension. If the mooring point is improperly designed (e.g., positioned too high), this moment can directly counteract the buoy’s inherent righting moment. In extreme cases, “mooring failure” or “cable entanglement” may occur. The sudden breakage of a single cable can subject the buoy to asymmetric and immense instantaneous loads, leading to sharp tilting. If the cable becomes entangled with the buoy (e.g., around heave plates or counterweights), it can persistently pull the buoy into an unbalanced posture, severely compromising stability.

Given the above effects, the design of the buoy’s mooring system and its influence on the buoy constitute a series of complex issues that warrant further investigation and validation in subsequent research.

5. Roll Natural Period of the Buoy

5.1. Small-Angle (0–15°) Roll Period

For small heel angles, the natural roll period TR is estimated from:

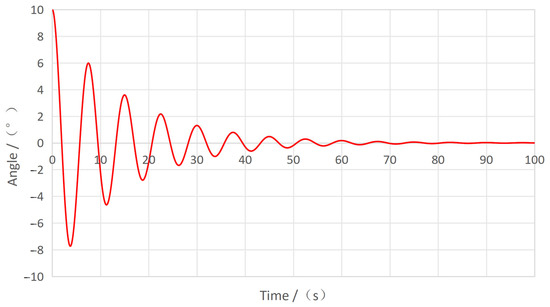

where TR is the rolling period, I’xx is the total moment of inertia about the x-axis of the buoy, , and is the additional moment of inertia. Here, Δ represents the displaced volume, B is the width of the buoy, and Zg is the height from the center of gravity to the bottom. After calculation, the rolling period for the OWC buoy at small heel angles is found to be 7.74 s.

The AQWA free-decay simulation (Figure 14) yields TR = 7.5 s, only 3% lower. The small-angle roll period is therefore taken as 7.5–7.7 s.

Figure 14.

The roll decay curve simulated by AQWA.

5.2. Large-Angle (>15°) Roll Period

Buoys experience multiple moments during rolling, including the restoring moment (MR), damping moment (MB), inertial moment (MI), and wave disturbance moment (MW). At large heel angles, the restoring moment exhibits nonlinear characteristics. Since damping and disturbance have minimal effects on the buoy’s rolling, the main consideration is the impact of nonlinear restoring force and inertial force on the rolling period, leading to the buoy rolling motion balance equation:

From Equation (13), the large-angle rolling period is given by:

Here, φm represents the initial rolling angle, ldm is the dynamic stability lever arm corresponding to φm, and ld is the dynamic stability lever arm at angle φ.

Let , and we obtain:

where l is the static stability lever arm.

For various initial rolling angles φm, the rolling period Tφ varies. The corresponding ldm must be calculated for each φm, and Tφ can be determined using Equation (15). The integral in Equation (15) can be computed using a tabulation method combined with the trapezoidal rule for correction.

Taking φm = 40° as an example, the dynamic stability lever arm ldm = 0.0939 m is determined at a rolling angle of 40°. Subsequently, ld is calculated based on θ. The angle φ corresponding to ld is obtained from the dynamic stability curve. The static stability lever l is determined from the static stability curve at angle φ. The ratio sinθ/l is calculated and recorded in Table 7. Steps are repeated until all sinθ/l values corresponding to θ are obtained. The trapezoidal method is then used to calculate the integral value (), and Equation (15) is applied to find Tφ for φm = 40°.

Table 7.

Calculation of Rolling Period at Large Angle (φm = 40°).

Substituting the values from Table 7, the integral value is obtained as . Further calculations yield Tφ

= 6.184 s.

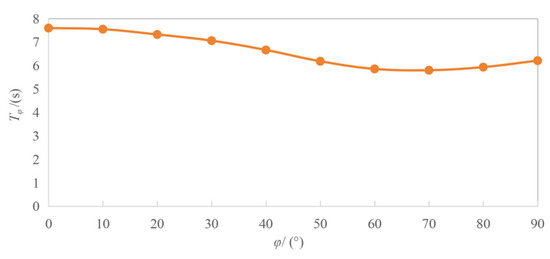

Figure 15 illustrates the rolling period as a function of the initial rolling angle. It shows that the rolling period of the OWC buoy at small angles is 7.45–7.7 s, consistent with the calculated results in Section 5.1. The rolling period decreases with increasing angle, reaching a minimum of 5.801 s around 70° and then slightly rises to 6.211 s. The overall rolling period range is 5.8–7.7 s.

Figure 15.

Variation of Rolling Period with Initial Heeling Angle.

According to the synchronous rolling theory, the tuning factor for roll is defined as . When , it is considered the resonance zone where the buoy is prone to resonate with waves and should be avoided as much as possible. The designed OWC buoy is intended for deployment in the waters of Xiaodeng Island, Xiamen, Fujian, where typical wave conditions [32] include a wavelength of 5 m, wave height of 1 m, wave period TW = 4 s, and water depth ranging from 7.9 to 13.9 m. The buoy’s value ranges from 1.45 to

1.925, steering clear of the resonance zone, especially since the most common

small-angle rolling period is further away from the wave period. Therefore, the

buoy is considered safe to operate in this sea area.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

6.1. Conclusions

An OWC central-pipe wave-energy buoy with an outer diameter of 3 m, inner diameter of 1.2 m and overall height of 3 m has been designed. Its stability and roll characteristics have been systematically investigated through mutually verified theoretical calculations and AQWA simulations. The main conclusions are:

- (1)

- Thirteen heeling regimes were identified; the present design covers the five representative regimes A1–A5. The initial metacentric height ≈ 0.33 m exceeds the 0.15 m statutory minimum; the maximum righting arm is 0.713 m at a limiting static heel of 77°, well above the 25° required. At heel angles ≥ 30°, the righting arm consistently exceeds 0.20 m. The angle of vanishing stability is far beyond 90°, indicating negligible capsize risk. The minimum capsizing arm is lq ≈ 0.28 m, giving a stability criterion K = 9.03 > 1, so dynamic stability complies with the Rules for the Statutory Survey of Ships and Marine Installations.

- (2)

- The small-angle roll natural period is 7.5–7.7 s, decreasing to a minimum of 5.8 s at large angles. The tuning factor = 1.45–1.92 lies outside the resonant range relative to the 4 s dominant wave period at the deployment site, guaranteeing safe dynamic response.

- (3)

- The discrepancies between the two calculation methods remain below 1%, demonstrating their mutual reliability and providing a robust design tool for future OWC buoys.

This study provides concrete guidance for the preliminary design of OWC buoys in four key aspects: (I) The proposed segmented-integration model enables rapid calculation of righting arms with guaranteed accuracy for various buoy dimensions, weights, and center-of-gravity positions. (II) The methodologies and formulas presented herein allow direct calculation of essential stability parameters, including initial metacentric height, righting arm at 30° heel, maximum righting arm, and minimum capsizing moment. (III) The natural period calculation framework can be extended to other buoy types, serving as a critical reference for both site selection and structural optimization for specific sea conditions. (IV) The strategic configuration of heave plates and ballast blocks offers an effective approach for stability enhancement.

6.2. Future Work

The following research directions are planned to extend the findings of this study:

- (1)

- Parametric Analysis for Method Validation

A comprehensive parametric study will be conducted to establish the broader applicability of the proposed theoretical model. This systematic investigation will involve variations in key geometric parameters (e.g., diameter, draft, and central duct size) alongside adjustments to mass properties. The objective is to thoroughly verify the model’s robustness and generality across an expanded design space for OWC buoys.

- (2)

- Experimental and High-Fidelity Numerical Validation

Further validation will be pursued through experimental wave tank testing complemented by high-fidelity CFD simulations. These investigations will focus particularly on critical heel angles to provide additional corroboration of the theoretical and numerical results presented in this study. The combined approach will deliver a more comprehensive verification of the buoy’s stability characteristics.

- (3)

- Mooring System Coupling Effects

The influence of mooring systems on buoy stability and motion response will be systematically investigated. A coupled dynamic analysis will be developed to evaluate mooring-buoy interactions under extreme environmental conditions, with particular focus on the additional righting moments provided by mooring lines and potential capsizing risks induced by snap loads or asymmetric configurations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z., J.K. and S.Y.; methodology, S.Y. and C.L.; software simulation, S.Z. and H.Z.; validation, Y.T. and C.L.; formal analysis, S.Z. and H.Z.; data curation, C.L. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, S.Z., Y.T. and J.K.; funding acquisition, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 42476225 & 42506217), Fujian Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Grant numbers: 2023H61010068, 2024J08195 & 2023J01791 & 2023J01146 & 2024J01112 & 2024J01718 & 2022J05155), Xiamen City Department of Science and Technology (Grant numbers: 3502Z202471046 & 3502Z20227057) and Fujian Provincial Department of Education (Grant number: JZ230027).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OWC | Oscillating Water Column |

| BBDB | Backward-bent duct buoy |

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

References

- Falnes, J. A review of wave-energy extraction. Mar. Struct. 2007, 20, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, A.F.d.O. Control of an oscillating-water-column wave power plant for maximum energy production. Appl. Ocean Res. 2002, 24, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, A.F.O.; Henriques, J.C.C. Oscillating-water-column wave energy converters and air turbines: A review. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 1391–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, M.; Henriques, J.C.C.; Ringwood, J.V. Oscillating-water-column wave energy converters: A critical review of numerical modelling and control. Energy Convers. Manag. X. 2022, 16, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xu, C. Hydrodynamic and energy-harvesting performance of a BBDB-OWC device in irregular waves: An experimental study. Appl. Energy 2023, 350, 121737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.I.; Aiman, M.J.; Rahman, M.R.A.; Saad, M.R. Backward Bent Duct Buoy (BBDB) of Wave Energy Converter: An Overview of BBDB Shapes. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering 2019; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Du, Z.; Tu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liang, B.; Chen, X.; Cao, G.; Xiao, S.; Yang, S. Experimental study of a backward bent duct buoy wave energy converter: Effects of the air chamber and center of gravity height. Ocean Eng. 2024, 313, 119447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Aggidis, G. An Experimental Study of a Conventional Cylindrical Oscillating Water Column Wave Energy Converter: Fixed and Floating Devices. Energies 2025, 18, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, C.; Du, Z.; Tu, Y.; Dai, X.; Huang, Y.; Fan, J.; Hong, Z.; Jiang, T.; Wang, Z.L. Fluid Oscillation-Driven Bi-Directional Air Turbine Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Ocean Wave Energy Harvesting. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2304184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhu, W.; Tu, Y.; Cao, G.; Chen, X.; Du, Z.; Fan, J.; Huang, Y. Study on the influence of heave plate on energy capture performance of central pipe oscillating water column wave energy converter. Energy 2024, 312, 133517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W. An experimental study for improving performance of a cylindrical OWC WEC with a heave plate. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 214, 115517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.; Henriques, J.; Gato, L.; Falcão, A. Wave power extraction of a heaving floating oscillating water column in a wave channel. Renew. Energy 2016, 99, 1262–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, X.; Tu, Y.; Du, Z.; Li, H.; Li, D.; Dong, W.; Lin, J.; Zheng, S. Experimental study on the wave energy capture performance of a dual-chamber oscillating water column wave energy converter. Energy 2025, 332, 137245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Abdussamie, N.; Hore, J. Hydrodynamic performance of a floating offshore OWC wave energy converter: An experimental study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 117, 109501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xu, T.; Wan, C.; Liu, H.; Su, Z.; Zhao, L.; Chen, H.; Johanning, L. Numerical investigation of a dual cylindrical OWC hybrid system incorporated into a fixed caisson breakwater. Energy 2023, 263, 126132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leine, R.I. The historical development of classical stability concepts: Lagrange, Poisson and Lyapunov stability. Nonlinear Dyn. 2010, 59, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, K.J. The stability of floating regular solids. Ocean Eng. 2022, 257, 111615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, M. Theoretical and Numerical Analysis of Ocean Buoy Stability Using Simplified Stability Parameters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Xue, Y.; Sun, B.; Tao, C.; Guan, S.; Zhou, X. Stability design of a small profiling buoy for marine physical properties monitoring. Adv. Mar. Sci. 2020, 38, 541–548. [Google Scholar]

- Segura, M. Alternative approach to explore the stability of floating bodies. Rev. Mex. De Física 2023, 69, 690601. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, G.; Giorgi, G.; Davidson, J. Coexisting attractors in floating body dynamics undergoing parametric resonance. Acta Mech. 2022, 233, 2351–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, A.; Datta, T.K. Nonlinear response of moored buoy under wave and wind excitations. Appl. Ocean Res. 2003, 25, 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Aziminia, M.; Abazari, A.; Behzad, M.; Hayatdavoodi, M. Stability analysis of parametric resonance in spar-buoy based on Floquet theory. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 113090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, A.; Han, F.; Lu, Y. Stability analysis of nonlinear ship-roll dynamics under wind and wave excitations Chaos. Solitons Fractals 2015, 76, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Ning, C.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Li, A.; Liu, Z. Methods Study of Bailong Buoy’s Stability Test Design. Coast. Eng. 2023, 42, 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Lian, W.; Qu, Z.; Xiong, X. Design and stability analysis of cylindrical inner wave observation buoy. Coast. Eng. 2021, 40, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Ning, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, B. Calculation and Analysis of the Balance of Ocean Buoy Body in the Water. J. Ocean Technol. 2019, 3, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, H.; Ma, L. Wave Piercing Structure Design of Buoy and Finite Element Analysis. Navig. China 2017, 40, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Zeng, X. Principles of Naval Architecture, 2nd ed.; China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 16–97. [Google Scholar]

- Maritime Safety Administration of the People‘s Republic of China. Statutory Survey Rules for Ships and Marine Installations; Maritime Safety Administration of the People‘s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Z.; Liu, Y. Principles of Naval Architecture (Vol.1 & Vol.2), 1st ed.; Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press: Shanghai, China, 2004; pp. 376–404. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; He, H. Design of the Mooring System on the Wave Power Platform with Floating and Pendular Type. Ship Build. China 2015, 6, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).